User login

Elliptical excision

Shave biopsy

Punch biopsy

Elbow nodules

A 42-year-old woman came to our clinic to have lumps on her right elbow removed. She said the lumps did not bother her, but on further questioning, admitted that her fingers turned white when they were exposed to the cold. She had frequent heartburn, but denied fatigue, weight loss, dysphagia, diarrhea, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, muscle weakness, or digital pain.

On physical exam, there were multiple small, firm subcutaneous nodules—some with a white surface protruding through the skin of her right elbow (FIGURE 1A). The nodules were slightly tender to palpation. On further examination we noted tight, smooth skin on her fingers (FIGURE 1B). Her right thumb was fixed in an extended position (FIGURE 2). There were also small blood vessels on her hands and pitted scars on her fingertips.

FIGURE 1

Elbow nodules and clubbing of the fingers

The 42-year-old patient sought care at the clinic to have slightly tender nodules removed from her right elbow. The patient also had tight skin and clubbing of the fingers.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 2

Thumb fixed in an extended position

The patient had tight skin on her fingers and a pitted scar on her thumb, which was fixed in an extended position.

Diagnosis: CREST syndrome

Our patient had CREST syndrome, a variant of limited systemic scleroderma. CREST syndrome is characterized by Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias.

Systemic scleroderma is a chronic auto-immune disease involving sclerotic, vascular, and inflammatory changes of the skin and internal organs. There are 19 new cases per million adults per year, with an estimated annual prevalence of 276 cases per million adults in the United States.1 Scleroderma occurs in women 4.6 times more often than in men; the mean age at diagnosis is 45 years.1 Although the pathogenesis of scleroderma remains unclear, interactions among leukocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts are likely to be central in this disease.2

According to the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines,3 a diagnosis of systemic scleroderma can be made with either 1 major criterion or 2 minor criteria present. The major criterion is symmetric thickening, tightening, and induration of the skin proximal to the metatarsal-phalangeal or metacarpal-phalangeal joints. This may affect the whole extremity, trunk, neck, and face. The minor criteria include sclerodactyly, digital pitting scars or a loss of substance from the finger pads, and bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis.

Two forms of scleroderma. To improve sensitivity for milder forms of disease, the condition is often divided into diffuse systemic scleroderma (dSSc) or limited systemic scleroderma (lSSc) (TABLE 1), with CREST syndrome being a variant of the limited form.4 Patients with dSSc usually have a rapid diffuse involvement of the trunk, hands, feet, and face with early internal organ involvement. Patients with lSSc, however, usually have slow skin involvement limited to hands, feet, and face, and delayed systemic involvement, if any.

If CREST syndrome is suspected, it is important to look for its cardinal features. Cutaneous calcinosis usually presents over the bony prominences of knees, elbows, spine, and iliac crests, and may be painful. Patients may complain of Raynaud’s phenomenon with triphasic color changes, ie, pallor, cyanosis, and rubor, occurring months to years before sclerosis. Ulcerations at fingertips from Raynaud’s may be evident as pitted scars on physical exam. There is also a nonpitting edema of hands and feet that later progresses into sclerodactyly with tapering of fingers (our patient actually had clubbing). Patients may complain of stiffness of the hands and feet as the sclerosis progresses.

As a result of the edema and fibrosis of the face, patients may lose facial lines and comment that they look younger. Often, they will indicate that they have noticed the appearance of small blood vessels on their face, mouth, or hands. Patients may also complain of gastrointestinal problems such as esophageal reflux, diarrhea, or dysphagia.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of systemic scleroderma4-6

| Diffuse systemic scleroderma | Limited systemic scleroderma (Includes CREST syndrome) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Fatigue and weight loss or gain | None |

| Vascular | Mild to moderate Raynaud’s phenomenon | Moderate to severe Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Cutaneous | Sclerosis to trunk, arms, and face; rapid progression | Sclerosis to hands or toes and face; slow progression; calcinosis is prominent |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgias and deformities, muscle weakness, and tendon friction rubs | Arthralgias |

| Gastrointestinal | GERD, esophageal dysmotility, and malabsorption are common; all may be severe | Mild to moderate GERD and esophageal dysmotility are common; malabsorption is less common |

| Renal | Severe hypertension, and renal infarcts in renal crisis are common | Rare |

| Pulmonary | Pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease are common | Uncommon |

| Cardiac | Cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias are common | Uncommon |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | ||

Differential includes morphea and scleromyxedema

A thorough history, physical exam, lab work, and possibly biopsy will help differentiate systemic scleroderma from the possible diagnoses with sclerosis listed below:

- Morphea features a localized, patchy distribution of skin fibrosis. There is no systemic involvement or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

- Mixed connective tissue disease has features of other autoimmune diseases, along with those of scleroderma.

- Eosinophilic fasciitis involves the fascia and muscle on biopsy. There is sparing of the hands.

- Scleromyxedema represents the skin thickening seen in patients with a gammopathy. Raynaud’s phenomenon may also be present.

- Scleredema is associated with diabetes. Skin changes are found mostly on the neck, shoulders, and upper arms. On rare occasions, there is visceral involvement. Raynaud’s phenomenon is not present.

In addition, the differential includes chronic graft-vs-host disease; lichen sclerosis et atrophicus; amyloidosis; porphyria cutanea et tardia; primary Raynaud’s phenomenon; and polyvinyl chloride, bleomycin, or pentazocyine exposure.

Nailfold capillary abnormalities help with the diagnosis

As noted earlier, diagnosing systemic scleroderma hinges on taking a good history, doing a thorough physical exam, applying the ACR diagnostic criteria, and ordering lab work. The sensitivity of the ACR criteria increases from 67% to 99% with the addition of nailfold capillary abnormalities (telangiectasias), identified using a dermatoscope.5

The initial lab work that you should consider includes an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test, complete blood count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. If the ANA is positive, anticentromere antibody (ACA) and DNA topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody tests should be ordered to see if scleroderma is likely limited or diffuse. ACA will be present in 21% of dSSc and 71% of lSSc cases, whereas Scl-70 will be present in 33% of dSSc and 18% of lSSc cases.6

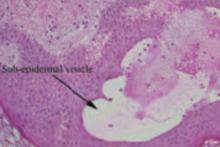

If the diagnosis is still unclear, do a punch biopsy. Histology in the early phase will show mild cellular infiltrates around dermal blood vessels and at the dermal subcutaneous inter-phase, while the later phase will show thickening of dermis with broadening of collagen fibers and hyalinization of blood vessel walls.6 If lung, kidney, heart, or gastrointestinal involvement is suspected based on symptoms or physical exam, you’ll need to do an organ function work-up.

Treatment focuses on organ-specific problems

Currently, there are no guidelines for the treatment of scleroderma, given that the exact pathogenesis remains unclear and the disease course varies from patient to patient. Pharmacologic therapy is focused on symptoms and organ-specific problems (TABLE 2). Prazosin 1 to 3 mg TID is moderately effective in treating Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to scleroderma7 (SOR: A). Losartan has been reported to reduce the frequency and severity of Raynaud’s phenomenon compared with a low dose of nifedepine,8 in a nonblinded randomized controlled trial (SOR: B). For interstitial lung disease, cyclophosphamide has been found to modestly reduce dyspnea while improving lung function, but it requires close monitoring9 (SOR: A). Bosentan is approved for symptomatic pulmonary hypertension and has been shown to decrease the occurrence of digital ulcers secondary to Raynaud’s phenomenon10 (SOR: A). (Bosentan is available in the United States under a special restricted distribution program called the Tracleer Access Program.)

Nonpharmacologic treatments should also be considered in the management of scleroderma. Advise patients that Raynaud’s phenomenon may be improved by avoiding exposure to the cold and by not smoking (SOR: C). Cutaneous ulcers can be protected with an occlusive dressing and treated with antibiotics if infected (SOR: C). To remove painful calcinotic nodules or release contractures secondary to sclerosis that may limit movement, you may want to consider surgery for your patient11 (SOR: C). If aesthetically unappealing, telangiectasias may be removed with electrosurgery or laser therapy (SOR: C).

Prognosis for scleroderma varies, depending on whether it is diffuse or limited. One large study found that patients with lSSc had a 10-year survival rate of 71%, compared with 21% for patients with dSSc (SOR: B).4 Patients with systemic sclerosis should be monitored for interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, and cardiomyopathy (SOR: C). Prognosis worsens with renal, pulmonary, or cardiac involvement; pulmonary disease is the leading cause of death in dSSc.1

TABLE 2

Medical treatment of systemic scleroderma5-9

| Organ-specific problem/symptom | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Nifedipine, verapamil, losartan, iloprost, prazosin, bosentan* |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Bosentan,* iloprost, captopril, enalapril, sildenafil |

| Interstitial lung disease | Cyclophosphamide, prednisone |

| Cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias | Antiarrhythmics, diuretics, digoxin, pacemaker, transplant |

| Renal failure or crisis | Captopril, kidney dialysis, transplant |

| Skin fibrosis | Methotrexate, cyclosporine, D-penicillamine |

| Arthralgias | Ibuprofen, acetaminophen |

| GERD, gastroparesis, diarrhea | H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics, antibiotics |

| Pruritus | Antihistamines, low-dose topical steroids |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | |

| *Restricted access in the United States. | |

Our patient has a change of heart

Our patient had all the cardinal features of CREST syndrome on history and physical exam. She had an ANA of 1:640 with speckled pattern and ACA and Scl-70 were negative, demonstrating that diagnosis must be made in clinical context and not just based on lab markers. We treated her GERD with lifestyle changes and a proton pump inhibitor. We explained the risks and benefits of cutting out her calcinosis nodules and she chose not to have surgery.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Diaz, MD, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, Mail #7816, San Antonio, TX 78229; Diazl3@uthscsa.edu

1. Mayes MD, Lacey JV, Jr, Beebe-Deemer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2246-2255.

2. Hasegawa M, Sato S. The roles of chemokines in leukocyte recruitment in systemic sclerosis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3637-3647.

3. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581-590.

4. Barnett AJ, Miller MH, Littlejohn GO. A survival study of patients with scleroderma diagnosed over 30 years (1953-1983): the value of a simple cutaneous classification in the early stages of disease. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:276-283.

5. Hudson M, Taillerfer S, Steele R, et al. Improving sensitivity of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:754-757.

6. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

7. Harding SE, Tingey PC, Pope J, et al. Prazosin for Raynaud’s phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998;(2):CD000956.-

8. Dziadzio M, Denton CP, Smith R, et al. Losartan therapy for Raynaud’s phenomenon and scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2646-2655.

9. Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements P, et al. For the Scleroderma Lung Study Research Group. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655-2666.

10. Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelial receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3884-3995.

11. Melone CP, Jr, McLoughlin JC, Beldner S. Surgical management of the hand in scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:514-520.

A 42-year-old woman came to our clinic to have lumps on her right elbow removed. She said the lumps did not bother her, but on further questioning, admitted that her fingers turned white when they were exposed to the cold. She had frequent heartburn, but denied fatigue, weight loss, dysphagia, diarrhea, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, muscle weakness, or digital pain.

On physical exam, there were multiple small, firm subcutaneous nodules—some with a white surface protruding through the skin of her right elbow (FIGURE 1A). The nodules were slightly tender to palpation. On further examination we noted tight, smooth skin on her fingers (FIGURE 1B). Her right thumb was fixed in an extended position (FIGURE 2). There were also small blood vessels on her hands and pitted scars on her fingertips.

FIGURE 1

Elbow nodules and clubbing of the fingers

The 42-year-old patient sought care at the clinic to have slightly tender nodules removed from her right elbow. The patient also had tight skin and clubbing of the fingers.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 2

Thumb fixed in an extended position

The patient had tight skin on her fingers and a pitted scar on her thumb, which was fixed in an extended position.

Diagnosis: CREST syndrome

Our patient had CREST syndrome, a variant of limited systemic scleroderma. CREST syndrome is characterized by Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias.

Systemic scleroderma is a chronic auto-immune disease involving sclerotic, vascular, and inflammatory changes of the skin and internal organs. There are 19 new cases per million adults per year, with an estimated annual prevalence of 276 cases per million adults in the United States.1 Scleroderma occurs in women 4.6 times more often than in men; the mean age at diagnosis is 45 years.1 Although the pathogenesis of scleroderma remains unclear, interactions among leukocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts are likely to be central in this disease.2

According to the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines,3 a diagnosis of systemic scleroderma can be made with either 1 major criterion or 2 minor criteria present. The major criterion is symmetric thickening, tightening, and induration of the skin proximal to the metatarsal-phalangeal or metacarpal-phalangeal joints. This may affect the whole extremity, trunk, neck, and face. The minor criteria include sclerodactyly, digital pitting scars or a loss of substance from the finger pads, and bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis.

Two forms of scleroderma. To improve sensitivity for milder forms of disease, the condition is often divided into diffuse systemic scleroderma (dSSc) or limited systemic scleroderma (lSSc) (TABLE 1), with CREST syndrome being a variant of the limited form.4 Patients with dSSc usually have a rapid diffuse involvement of the trunk, hands, feet, and face with early internal organ involvement. Patients with lSSc, however, usually have slow skin involvement limited to hands, feet, and face, and delayed systemic involvement, if any.

If CREST syndrome is suspected, it is important to look for its cardinal features. Cutaneous calcinosis usually presents over the bony prominences of knees, elbows, spine, and iliac crests, and may be painful. Patients may complain of Raynaud’s phenomenon with triphasic color changes, ie, pallor, cyanosis, and rubor, occurring months to years before sclerosis. Ulcerations at fingertips from Raynaud’s may be evident as pitted scars on physical exam. There is also a nonpitting edema of hands and feet that later progresses into sclerodactyly with tapering of fingers (our patient actually had clubbing). Patients may complain of stiffness of the hands and feet as the sclerosis progresses.

As a result of the edema and fibrosis of the face, patients may lose facial lines and comment that they look younger. Often, they will indicate that they have noticed the appearance of small blood vessels on their face, mouth, or hands. Patients may also complain of gastrointestinal problems such as esophageal reflux, diarrhea, or dysphagia.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of systemic scleroderma4-6

| Diffuse systemic scleroderma | Limited systemic scleroderma (Includes CREST syndrome) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Fatigue and weight loss or gain | None |

| Vascular | Mild to moderate Raynaud’s phenomenon | Moderate to severe Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Cutaneous | Sclerosis to trunk, arms, and face; rapid progression | Sclerosis to hands or toes and face; slow progression; calcinosis is prominent |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgias and deformities, muscle weakness, and tendon friction rubs | Arthralgias |

| Gastrointestinal | GERD, esophageal dysmotility, and malabsorption are common; all may be severe | Mild to moderate GERD and esophageal dysmotility are common; malabsorption is less common |

| Renal | Severe hypertension, and renal infarcts in renal crisis are common | Rare |

| Pulmonary | Pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease are common | Uncommon |

| Cardiac | Cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias are common | Uncommon |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | ||

Differential includes morphea and scleromyxedema

A thorough history, physical exam, lab work, and possibly biopsy will help differentiate systemic scleroderma from the possible diagnoses with sclerosis listed below:

- Morphea features a localized, patchy distribution of skin fibrosis. There is no systemic involvement or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

- Mixed connective tissue disease has features of other autoimmune diseases, along with those of scleroderma.

- Eosinophilic fasciitis involves the fascia and muscle on biopsy. There is sparing of the hands.

- Scleromyxedema represents the skin thickening seen in patients with a gammopathy. Raynaud’s phenomenon may also be present.

- Scleredema is associated with diabetes. Skin changes are found mostly on the neck, shoulders, and upper arms. On rare occasions, there is visceral involvement. Raynaud’s phenomenon is not present.

In addition, the differential includes chronic graft-vs-host disease; lichen sclerosis et atrophicus; amyloidosis; porphyria cutanea et tardia; primary Raynaud’s phenomenon; and polyvinyl chloride, bleomycin, or pentazocyine exposure.

Nailfold capillary abnormalities help with the diagnosis

As noted earlier, diagnosing systemic scleroderma hinges on taking a good history, doing a thorough physical exam, applying the ACR diagnostic criteria, and ordering lab work. The sensitivity of the ACR criteria increases from 67% to 99% with the addition of nailfold capillary abnormalities (telangiectasias), identified using a dermatoscope.5

The initial lab work that you should consider includes an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test, complete blood count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. If the ANA is positive, anticentromere antibody (ACA) and DNA topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody tests should be ordered to see if scleroderma is likely limited or diffuse. ACA will be present in 21% of dSSc and 71% of lSSc cases, whereas Scl-70 will be present in 33% of dSSc and 18% of lSSc cases.6

If the diagnosis is still unclear, do a punch biopsy. Histology in the early phase will show mild cellular infiltrates around dermal blood vessels and at the dermal subcutaneous inter-phase, while the later phase will show thickening of dermis with broadening of collagen fibers and hyalinization of blood vessel walls.6 If lung, kidney, heart, or gastrointestinal involvement is suspected based on symptoms or physical exam, you’ll need to do an organ function work-up.

Treatment focuses on organ-specific problems

Currently, there are no guidelines for the treatment of scleroderma, given that the exact pathogenesis remains unclear and the disease course varies from patient to patient. Pharmacologic therapy is focused on symptoms and organ-specific problems (TABLE 2). Prazosin 1 to 3 mg TID is moderately effective in treating Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to scleroderma7 (SOR: A). Losartan has been reported to reduce the frequency and severity of Raynaud’s phenomenon compared with a low dose of nifedepine,8 in a nonblinded randomized controlled trial (SOR: B). For interstitial lung disease, cyclophosphamide has been found to modestly reduce dyspnea while improving lung function, but it requires close monitoring9 (SOR: A). Bosentan is approved for symptomatic pulmonary hypertension and has been shown to decrease the occurrence of digital ulcers secondary to Raynaud’s phenomenon10 (SOR: A). (Bosentan is available in the United States under a special restricted distribution program called the Tracleer Access Program.)

Nonpharmacologic treatments should also be considered in the management of scleroderma. Advise patients that Raynaud’s phenomenon may be improved by avoiding exposure to the cold and by not smoking (SOR: C). Cutaneous ulcers can be protected with an occlusive dressing and treated with antibiotics if infected (SOR: C). To remove painful calcinotic nodules or release contractures secondary to sclerosis that may limit movement, you may want to consider surgery for your patient11 (SOR: C). If aesthetically unappealing, telangiectasias may be removed with electrosurgery or laser therapy (SOR: C).

Prognosis for scleroderma varies, depending on whether it is diffuse or limited. One large study found that patients with lSSc had a 10-year survival rate of 71%, compared with 21% for patients with dSSc (SOR: B).4 Patients with systemic sclerosis should be monitored for interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, and cardiomyopathy (SOR: C). Prognosis worsens with renal, pulmonary, or cardiac involvement; pulmonary disease is the leading cause of death in dSSc.1

TABLE 2

Medical treatment of systemic scleroderma5-9

| Organ-specific problem/symptom | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Nifedipine, verapamil, losartan, iloprost, prazosin, bosentan* |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Bosentan,* iloprost, captopril, enalapril, sildenafil |

| Interstitial lung disease | Cyclophosphamide, prednisone |

| Cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias | Antiarrhythmics, diuretics, digoxin, pacemaker, transplant |

| Renal failure or crisis | Captopril, kidney dialysis, transplant |

| Skin fibrosis | Methotrexate, cyclosporine, D-penicillamine |

| Arthralgias | Ibuprofen, acetaminophen |

| GERD, gastroparesis, diarrhea | H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics, antibiotics |

| Pruritus | Antihistamines, low-dose topical steroids |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | |

| *Restricted access in the United States. | |

Our patient has a change of heart

Our patient had all the cardinal features of CREST syndrome on history and physical exam. She had an ANA of 1:640 with speckled pattern and ACA and Scl-70 were negative, demonstrating that diagnosis must be made in clinical context and not just based on lab markers. We treated her GERD with lifestyle changes and a proton pump inhibitor. We explained the risks and benefits of cutting out her calcinosis nodules and she chose not to have surgery.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Diaz, MD, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, Mail #7816, San Antonio, TX 78229; Diazl3@uthscsa.edu

A 42-year-old woman came to our clinic to have lumps on her right elbow removed. She said the lumps did not bother her, but on further questioning, admitted that her fingers turned white when they were exposed to the cold. She had frequent heartburn, but denied fatigue, weight loss, dysphagia, diarrhea, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, muscle weakness, or digital pain.

On physical exam, there were multiple small, firm subcutaneous nodules—some with a white surface protruding through the skin of her right elbow (FIGURE 1A). The nodules were slightly tender to palpation. On further examination we noted tight, smooth skin on her fingers (FIGURE 1B). Her right thumb was fixed in an extended position (FIGURE 2). There were also small blood vessels on her hands and pitted scars on her fingertips.

FIGURE 1

Elbow nodules and clubbing of the fingers

The 42-year-old patient sought care at the clinic to have slightly tender nodules removed from her right elbow. The patient also had tight skin and clubbing of the fingers.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 2

Thumb fixed in an extended position

The patient had tight skin on her fingers and a pitted scar on her thumb, which was fixed in an extended position.

Diagnosis: CREST syndrome

Our patient had CREST syndrome, a variant of limited systemic scleroderma. CREST syndrome is characterized by Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias.

Systemic scleroderma is a chronic auto-immune disease involving sclerotic, vascular, and inflammatory changes of the skin and internal organs. There are 19 new cases per million adults per year, with an estimated annual prevalence of 276 cases per million adults in the United States.1 Scleroderma occurs in women 4.6 times more often than in men; the mean age at diagnosis is 45 years.1 Although the pathogenesis of scleroderma remains unclear, interactions among leukocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts are likely to be central in this disease.2

According to the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines,3 a diagnosis of systemic scleroderma can be made with either 1 major criterion or 2 minor criteria present. The major criterion is symmetric thickening, tightening, and induration of the skin proximal to the metatarsal-phalangeal or metacarpal-phalangeal joints. This may affect the whole extremity, trunk, neck, and face. The minor criteria include sclerodactyly, digital pitting scars or a loss of substance from the finger pads, and bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis.

Two forms of scleroderma. To improve sensitivity for milder forms of disease, the condition is often divided into diffuse systemic scleroderma (dSSc) or limited systemic scleroderma (lSSc) (TABLE 1), with CREST syndrome being a variant of the limited form.4 Patients with dSSc usually have a rapid diffuse involvement of the trunk, hands, feet, and face with early internal organ involvement. Patients with lSSc, however, usually have slow skin involvement limited to hands, feet, and face, and delayed systemic involvement, if any.

If CREST syndrome is suspected, it is important to look for its cardinal features. Cutaneous calcinosis usually presents over the bony prominences of knees, elbows, spine, and iliac crests, and may be painful. Patients may complain of Raynaud’s phenomenon with triphasic color changes, ie, pallor, cyanosis, and rubor, occurring months to years before sclerosis. Ulcerations at fingertips from Raynaud’s may be evident as pitted scars on physical exam. There is also a nonpitting edema of hands and feet that later progresses into sclerodactyly with tapering of fingers (our patient actually had clubbing). Patients may complain of stiffness of the hands and feet as the sclerosis progresses.

As a result of the edema and fibrosis of the face, patients may lose facial lines and comment that they look younger. Often, they will indicate that they have noticed the appearance of small blood vessels on their face, mouth, or hands. Patients may also complain of gastrointestinal problems such as esophageal reflux, diarrhea, or dysphagia.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of systemic scleroderma4-6

| Diffuse systemic scleroderma | Limited systemic scleroderma (Includes CREST syndrome) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Fatigue and weight loss or gain | None |

| Vascular | Mild to moderate Raynaud’s phenomenon | Moderate to severe Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Cutaneous | Sclerosis to trunk, arms, and face; rapid progression | Sclerosis to hands or toes and face; slow progression; calcinosis is prominent |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgias and deformities, muscle weakness, and tendon friction rubs | Arthralgias |

| Gastrointestinal | GERD, esophageal dysmotility, and malabsorption are common; all may be severe | Mild to moderate GERD and esophageal dysmotility are common; malabsorption is less common |

| Renal | Severe hypertension, and renal infarcts in renal crisis are common | Rare |

| Pulmonary | Pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease are common | Uncommon |

| Cardiac | Cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias are common | Uncommon |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | ||

Differential includes morphea and scleromyxedema

A thorough history, physical exam, lab work, and possibly biopsy will help differentiate systemic scleroderma from the possible diagnoses with sclerosis listed below:

- Morphea features a localized, patchy distribution of skin fibrosis. There is no systemic involvement or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

- Mixed connective tissue disease has features of other autoimmune diseases, along with those of scleroderma.

- Eosinophilic fasciitis involves the fascia and muscle on biopsy. There is sparing of the hands.

- Scleromyxedema represents the skin thickening seen in patients with a gammopathy. Raynaud’s phenomenon may also be present.

- Scleredema is associated with diabetes. Skin changes are found mostly on the neck, shoulders, and upper arms. On rare occasions, there is visceral involvement. Raynaud’s phenomenon is not present.

In addition, the differential includes chronic graft-vs-host disease; lichen sclerosis et atrophicus; amyloidosis; porphyria cutanea et tardia; primary Raynaud’s phenomenon; and polyvinyl chloride, bleomycin, or pentazocyine exposure.

Nailfold capillary abnormalities help with the diagnosis

As noted earlier, diagnosing systemic scleroderma hinges on taking a good history, doing a thorough physical exam, applying the ACR diagnostic criteria, and ordering lab work. The sensitivity of the ACR criteria increases from 67% to 99% with the addition of nailfold capillary abnormalities (telangiectasias), identified using a dermatoscope.5

The initial lab work that you should consider includes an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test, complete blood count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. If the ANA is positive, anticentromere antibody (ACA) and DNA topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody tests should be ordered to see if scleroderma is likely limited or diffuse. ACA will be present in 21% of dSSc and 71% of lSSc cases, whereas Scl-70 will be present in 33% of dSSc and 18% of lSSc cases.6

If the diagnosis is still unclear, do a punch biopsy. Histology in the early phase will show mild cellular infiltrates around dermal blood vessels and at the dermal subcutaneous inter-phase, while the later phase will show thickening of dermis with broadening of collagen fibers and hyalinization of blood vessel walls.6 If lung, kidney, heart, or gastrointestinal involvement is suspected based on symptoms or physical exam, you’ll need to do an organ function work-up.

Treatment focuses on organ-specific problems

Currently, there are no guidelines for the treatment of scleroderma, given that the exact pathogenesis remains unclear and the disease course varies from patient to patient. Pharmacologic therapy is focused on symptoms and organ-specific problems (TABLE 2). Prazosin 1 to 3 mg TID is moderately effective in treating Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to scleroderma7 (SOR: A). Losartan has been reported to reduce the frequency and severity of Raynaud’s phenomenon compared with a low dose of nifedepine,8 in a nonblinded randomized controlled trial (SOR: B). For interstitial lung disease, cyclophosphamide has been found to modestly reduce dyspnea while improving lung function, but it requires close monitoring9 (SOR: A). Bosentan is approved for symptomatic pulmonary hypertension and has been shown to decrease the occurrence of digital ulcers secondary to Raynaud’s phenomenon10 (SOR: A). (Bosentan is available in the United States under a special restricted distribution program called the Tracleer Access Program.)

Nonpharmacologic treatments should also be considered in the management of scleroderma. Advise patients that Raynaud’s phenomenon may be improved by avoiding exposure to the cold and by not smoking (SOR: C). Cutaneous ulcers can be protected with an occlusive dressing and treated with antibiotics if infected (SOR: C). To remove painful calcinotic nodules or release contractures secondary to sclerosis that may limit movement, you may want to consider surgery for your patient11 (SOR: C). If aesthetically unappealing, telangiectasias may be removed with electrosurgery or laser therapy (SOR: C).

Prognosis for scleroderma varies, depending on whether it is diffuse or limited. One large study found that patients with lSSc had a 10-year survival rate of 71%, compared with 21% for patients with dSSc (SOR: B).4 Patients with systemic sclerosis should be monitored for interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, and cardiomyopathy (SOR: C). Prognosis worsens with renal, pulmonary, or cardiac involvement; pulmonary disease is the leading cause of death in dSSc.1

TABLE 2

Medical treatment of systemic scleroderma5-9

| Organ-specific problem/symptom | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Nifedipine, verapamil, losartan, iloprost, prazosin, bosentan* |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Bosentan,* iloprost, captopril, enalapril, sildenafil |

| Interstitial lung disease | Cyclophosphamide, prednisone |

| Cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias | Antiarrhythmics, diuretics, digoxin, pacemaker, transplant |

| Renal failure or crisis | Captopril, kidney dialysis, transplant |

| Skin fibrosis | Methotrexate, cyclosporine, D-penicillamine |

| Arthralgias | Ibuprofen, acetaminophen |

| GERD, gastroparesis, diarrhea | H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics, antibiotics |

| Pruritus | Antihistamines, low-dose topical steroids |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | |

| *Restricted access in the United States. | |

Our patient has a change of heart

Our patient had all the cardinal features of CREST syndrome on history and physical exam. She had an ANA of 1:640 with speckled pattern and ACA and Scl-70 were negative, demonstrating that diagnosis must be made in clinical context and not just based on lab markers. We treated her GERD with lifestyle changes and a proton pump inhibitor. We explained the risks and benefits of cutting out her calcinosis nodules and she chose not to have surgery.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Diaz, MD, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, Mail #7816, San Antonio, TX 78229; Diazl3@uthscsa.edu

1. Mayes MD, Lacey JV, Jr, Beebe-Deemer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2246-2255.

2. Hasegawa M, Sato S. The roles of chemokines in leukocyte recruitment in systemic sclerosis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3637-3647.

3. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581-590.

4. Barnett AJ, Miller MH, Littlejohn GO. A survival study of patients with scleroderma diagnosed over 30 years (1953-1983): the value of a simple cutaneous classification in the early stages of disease. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:276-283.

5. Hudson M, Taillerfer S, Steele R, et al. Improving sensitivity of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:754-757.

6. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

7. Harding SE, Tingey PC, Pope J, et al. Prazosin for Raynaud’s phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998;(2):CD000956.-

8. Dziadzio M, Denton CP, Smith R, et al. Losartan therapy for Raynaud’s phenomenon and scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2646-2655.

9. Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements P, et al. For the Scleroderma Lung Study Research Group. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655-2666.

10. Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelial receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3884-3995.

11. Melone CP, Jr, McLoughlin JC, Beldner S. Surgical management of the hand in scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:514-520.

1. Mayes MD, Lacey JV, Jr, Beebe-Deemer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2246-2255.

2. Hasegawa M, Sato S. The roles of chemokines in leukocyte recruitment in systemic sclerosis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3637-3647.

3. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581-590.

4. Barnett AJ, Miller MH, Littlejohn GO. A survival study of patients with scleroderma diagnosed over 30 years (1953-1983): the value of a simple cutaneous classification in the early stages of disease. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:276-283.

5. Hudson M, Taillerfer S, Steele R, et al. Improving sensitivity of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:754-757.

6. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

7. Harding SE, Tingey PC, Pope J, et al. Prazosin for Raynaud’s phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998;(2):CD000956.-

8. Dziadzio M, Denton CP, Smith R, et al. Losartan therapy for Raynaud’s phenomenon and scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2646-2655.

9. Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements P, et al. For the Scleroderma Lung Study Research Group. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655-2666.

10. Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelial receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3884-3995.

11. Melone CP, Jr, McLoughlin JC, Beldner S. Surgical management of the hand in scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:514-520.

A white spot since birth

A 13-year-old Hispanic girl came into our skin clinic with her grandmother for evaluation of suspicious moles on her arms. The grandmother was also concerned about a hypopigmented lesion on the young woman’s chest.

The patient and her grandmother said that the chest lesion had been there since birth, but it had been slowly growing over the years. The lesion was asymptomatic—there was no pruritus, bleeding, or pain. The patient was otherwise healthy and was not taking any medications.

The patient and her grandmother indicated that no one in the family had a similar lesion. The patient had no fever or chills, nor any neurological, respiratory, cardiac, or gastrointestinal problems. The hypopigmented lesion on the patient’s chest had irregular borders and no scale (FIGURE 1).

There was no loss of sensation at the site and, upon applying pressure to the surrounding skin with a glass slide, the border between the lesion and normal skin disappeared.

FIGURE 1

Hypopigmented patch on chest

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Nevus anemicus

The patient had a nevus anemicus, which typically presents as an irregularly shaped hypopigmented patch on surrounding normal skin.1 Sometimes there are satellite macules, as well.2

Nevus anemicus is present at birth or appears shortly thereafter. It continues to grow with the child, and it remains asymptomatic. It is usually located on the trunk—primarily on the upper chest. However, there have been cases involving the extremities, head, and neck.3 The prevalence of this condition in the United States is unknown, but it is not considered rare. It is more common in females.4

Although nevus anemicus is an isolated finding in normal healthy individuals, it may occur in association with genodermatoses such as neurofibromatosis, and in conjunction with nevus flammeus and Mongolian spot in phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.1

Not a true nevus

This lesion is not a true nevus; rather, it is a congenital vascular anomaly with localized hypersensitivity to catecholamines. The vasoconstriction caused by this hypersensitivity results in skin pallor. When pressure is applied to the surrounding skin (diascopy), the border between the nevus and surrounding skin is lost due to blanching of surrounding skin.5

Intralesional injection of vasodilators, such as bradykinin, pilocarpine, acetylcholine, 5-hydroxytryptamine, nicotine, or histamine, fails to produce vasodilation in the affected areas.6 Axillary sympathetic block and intralesional injection of α-adrenergic blocking agents result in erythema.3 These findings support the conclusion that it is not a true nevus, but rather a vascular anomaly.

Differential Dx includes infectious diseases

The differential includes the following:

- Hansen’s disease (leprosy), caused by Mycobacterium leprae, presents with a loss of sensation at the site of hypopigmentation. This loss of sensation is due to nerve involvement. Histopathology yields a very specific pattern of epithelioid cell granulomas around the dermal nerves.7

- Tinea versicolor, caused by Malassezia furfur, has a fine scale on the hypopigmented patch. The lesion fluoresces under a Wood’s lamp, and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation will be positive, revealing the well-known “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern. Hypopigmentation in tinea versicolor results from the inhibition of the enzyme tyrosinase in the melanocytes.7

- Vitiligo results from the complete absence of melanocytes. Vitiligo is rarely present at birth.

- Nevus depigmentosus, also known as nevus achromicus, is a well-demarcated patch of hypopigmentation that tends to occur on the trunk or proximal extremities in a dermatomal pattern (FIGURE 2). It is a true nevus and diascopy will not result in the loss of the border between the hypopigmented patch and surrounding skin.5

FIGURE 2

Don’t be fooled: This is not nevus anemicus

Make the diagnosis based on the exam

The diagnosis of nevus anemicus is made primarily based on the history and exam. A number of techniques aid in confirming the diagnosis and excluding some of the diagnoses mentioned above.

Diascopy results in the loss of the border between nevus anemicus and normal skin.4,5 Anatomic nevi do not demonstrate this loss in border. Shining a Wood’s lamp does not accentuate the lesion, helping to distinguish nevus anemicus from fungal infections that tend to fluoresce.

Neither friction (produced by scratching a line across both the lesion and normal surrounding skin), nor cold or heat application, induces erythema in the involved areas.2 And unlike leprosy, there is no loss of sensation at the site of the hypopigmentation. A biopsy of the lesion is not needed, but would reveal normal histology. Melanocytes are preserved and normally distributed. Electron microscopy, while not needed, would not detect any abnormalities in the vascular structure.4

Nothing to worry about for our patient

Our patient required no treatment. We simply provided her with some information on the benign nature of nevus anemicus. (In addition, we dealt with the moles on her arms that prompted her visit. They turned out to be normal melanocytic nevi.)

We told the patient that if the lesion on her chest bothered her, she could hide it with concealer make-up.1,2 Our patient and her grandmother were happy with the explanation and did not seek further care.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shehnaz Zaman, MD, 420 Elmington Avenue, #417, Nashville, TN 37205; shehnazzaman@gmail.com

1. Ahkami RN, Schwartz RA. Nevus anemicus. Dermatology. 1999;198:327-329.

2. Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. Part 1. Hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:523-549.

3. Mountcastle EA, Diestelmeier MR, Lupton GP. Nevus anemicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:628-632.

4. Knoepp TG, Davis L. Nevus anemicus. e Medicine Web site. Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/derm/topic292.htm. Accessed October 13, 2007.

5. Hsu S. Photo quiz: white patch on back. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:1489-1490.

6. Greaves MW, Birkett D, Johnson C. Nevus anemicus: a unique catecholamine-dependent nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1970;102:172-176.

7. Wolff K, Johnson R, Suurmond R. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2005.

A 13-year-old Hispanic girl came into our skin clinic with her grandmother for evaluation of suspicious moles on her arms. The grandmother was also concerned about a hypopigmented lesion on the young woman’s chest.

The patient and her grandmother said that the chest lesion had been there since birth, but it had been slowly growing over the years. The lesion was asymptomatic—there was no pruritus, bleeding, or pain. The patient was otherwise healthy and was not taking any medications.

The patient and her grandmother indicated that no one in the family had a similar lesion. The patient had no fever or chills, nor any neurological, respiratory, cardiac, or gastrointestinal problems. The hypopigmented lesion on the patient’s chest had irregular borders and no scale (FIGURE 1).

There was no loss of sensation at the site and, upon applying pressure to the surrounding skin with a glass slide, the border between the lesion and normal skin disappeared.

FIGURE 1

Hypopigmented patch on chest

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Nevus anemicus

The patient had a nevus anemicus, which typically presents as an irregularly shaped hypopigmented patch on surrounding normal skin.1 Sometimes there are satellite macules, as well.2

Nevus anemicus is present at birth or appears shortly thereafter. It continues to grow with the child, and it remains asymptomatic. It is usually located on the trunk—primarily on the upper chest. However, there have been cases involving the extremities, head, and neck.3 The prevalence of this condition in the United States is unknown, but it is not considered rare. It is more common in females.4

Although nevus anemicus is an isolated finding in normal healthy individuals, it may occur in association with genodermatoses such as neurofibromatosis, and in conjunction with nevus flammeus and Mongolian spot in phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.1

Not a true nevus

This lesion is not a true nevus; rather, it is a congenital vascular anomaly with localized hypersensitivity to catecholamines. The vasoconstriction caused by this hypersensitivity results in skin pallor. When pressure is applied to the surrounding skin (diascopy), the border between the nevus and surrounding skin is lost due to blanching of surrounding skin.5

Intralesional injection of vasodilators, such as bradykinin, pilocarpine, acetylcholine, 5-hydroxytryptamine, nicotine, or histamine, fails to produce vasodilation in the affected areas.6 Axillary sympathetic block and intralesional injection of α-adrenergic blocking agents result in erythema.3 These findings support the conclusion that it is not a true nevus, but rather a vascular anomaly.

Differential Dx includes infectious diseases

The differential includes the following:

- Hansen’s disease (leprosy), caused by Mycobacterium leprae, presents with a loss of sensation at the site of hypopigmentation. This loss of sensation is due to nerve involvement. Histopathology yields a very specific pattern of epithelioid cell granulomas around the dermal nerves.7

- Tinea versicolor, caused by Malassezia furfur, has a fine scale on the hypopigmented patch. The lesion fluoresces under a Wood’s lamp, and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation will be positive, revealing the well-known “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern. Hypopigmentation in tinea versicolor results from the inhibition of the enzyme tyrosinase in the melanocytes.7

- Vitiligo results from the complete absence of melanocytes. Vitiligo is rarely present at birth.

- Nevus depigmentosus, also known as nevus achromicus, is a well-demarcated patch of hypopigmentation that tends to occur on the trunk or proximal extremities in a dermatomal pattern (FIGURE 2). It is a true nevus and diascopy will not result in the loss of the border between the hypopigmented patch and surrounding skin.5

FIGURE 2

Don’t be fooled: This is not nevus anemicus

Make the diagnosis based on the exam

The diagnosis of nevus anemicus is made primarily based on the history and exam. A number of techniques aid in confirming the diagnosis and excluding some of the diagnoses mentioned above.

Diascopy results in the loss of the border between nevus anemicus and normal skin.4,5 Anatomic nevi do not demonstrate this loss in border. Shining a Wood’s lamp does not accentuate the lesion, helping to distinguish nevus anemicus from fungal infections that tend to fluoresce.

Neither friction (produced by scratching a line across both the lesion and normal surrounding skin), nor cold or heat application, induces erythema in the involved areas.2 And unlike leprosy, there is no loss of sensation at the site of the hypopigmentation. A biopsy of the lesion is not needed, but would reveal normal histology. Melanocytes are preserved and normally distributed. Electron microscopy, while not needed, would not detect any abnormalities in the vascular structure.4

Nothing to worry about for our patient

Our patient required no treatment. We simply provided her with some information on the benign nature of nevus anemicus. (In addition, we dealt with the moles on her arms that prompted her visit. They turned out to be normal melanocytic nevi.)

We told the patient that if the lesion on her chest bothered her, she could hide it with concealer make-up.1,2 Our patient and her grandmother were happy with the explanation and did not seek further care.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shehnaz Zaman, MD, 420 Elmington Avenue, #417, Nashville, TN 37205; shehnazzaman@gmail.com

A 13-year-old Hispanic girl came into our skin clinic with her grandmother for evaluation of suspicious moles on her arms. The grandmother was also concerned about a hypopigmented lesion on the young woman’s chest.

The patient and her grandmother said that the chest lesion had been there since birth, but it had been slowly growing over the years. The lesion was asymptomatic—there was no pruritus, bleeding, or pain. The patient was otherwise healthy and was not taking any medications.

The patient and her grandmother indicated that no one in the family had a similar lesion. The patient had no fever or chills, nor any neurological, respiratory, cardiac, or gastrointestinal problems. The hypopigmented lesion on the patient’s chest had irregular borders and no scale (FIGURE 1).

There was no loss of sensation at the site and, upon applying pressure to the surrounding skin with a glass slide, the border between the lesion and normal skin disappeared.

FIGURE 1

Hypopigmented patch on chest

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Nevus anemicus

The patient had a nevus anemicus, which typically presents as an irregularly shaped hypopigmented patch on surrounding normal skin.1 Sometimes there are satellite macules, as well.2

Nevus anemicus is present at birth or appears shortly thereafter. It continues to grow with the child, and it remains asymptomatic. It is usually located on the trunk—primarily on the upper chest. However, there have been cases involving the extremities, head, and neck.3 The prevalence of this condition in the United States is unknown, but it is not considered rare. It is more common in females.4

Although nevus anemicus is an isolated finding in normal healthy individuals, it may occur in association with genodermatoses such as neurofibromatosis, and in conjunction with nevus flammeus and Mongolian spot in phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.1

Not a true nevus

This lesion is not a true nevus; rather, it is a congenital vascular anomaly with localized hypersensitivity to catecholamines. The vasoconstriction caused by this hypersensitivity results in skin pallor. When pressure is applied to the surrounding skin (diascopy), the border between the nevus and surrounding skin is lost due to blanching of surrounding skin.5

Intralesional injection of vasodilators, such as bradykinin, pilocarpine, acetylcholine, 5-hydroxytryptamine, nicotine, or histamine, fails to produce vasodilation in the affected areas.6 Axillary sympathetic block and intralesional injection of α-adrenergic blocking agents result in erythema.3 These findings support the conclusion that it is not a true nevus, but rather a vascular anomaly.

Differential Dx includes infectious diseases

The differential includes the following:

- Hansen’s disease (leprosy), caused by Mycobacterium leprae, presents with a loss of sensation at the site of hypopigmentation. This loss of sensation is due to nerve involvement. Histopathology yields a very specific pattern of epithelioid cell granulomas around the dermal nerves.7

- Tinea versicolor, caused by Malassezia furfur, has a fine scale on the hypopigmented patch. The lesion fluoresces under a Wood’s lamp, and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation will be positive, revealing the well-known “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern. Hypopigmentation in tinea versicolor results from the inhibition of the enzyme tyrosinase in the melanocytes.7

- Vitiligo results from the complete absence of melanocytes. Vitiligo is rarely present at birth.

- Nevus depigmentosus, also known as nevus achromicus, is a well-demarcated patch of hypopigmentation that tends to occur on the trunk or proximal extremities in a dermatomal pattern (FIGURE 2). It is a true nevus and diascopy will not result in the loss of the border between the hypopigmented patch and surrounding skin.5

FIGURE 2

Don’t be fooled: This is not nevus anemicus

Make the diagnosis based on the exam

The diagnosis of nevus anemicus is made primarily based on the history and exam. A number of techniques aid in confirming the diagnosis and excluding some of the diagnoses mentioned above.

Diascopy results in the loss of the border between nevus anemicus and normal skin.4,5 Anatomic nevi do not demonstrate this loss in border. Shining a Wood’s lamp does not accentuate the lesion, helping to distinguish nevus anemicus from fungal infections that tend to fluoresce.

Neither friction (produced by scratching a line across both the lesion and normal surrounding skin), nor cold or heat application, induces erythema in the involved areas.2 And unlike leprosy, there is no loss of sensation at the site of the hypopigmentation. A biopsy of the lesion is not needed, but would reveal normal histology. Melanocytes are preserved and normally distributed. Electron microscopy, while not needed, would not detect any abnormalities in the vascular structure.4

Nothing to worry about for our patient

Our patient required no treatment. We simply provided her with some information on the benign nature of nevus anemicus. (In addition, we dealt with the moles on her arms that prompted her visit. They turned out to be normal melanocytic nevi.)

We told the patient that if the lesion on her chest bothered her, she could hide it with concealer make-up.1,2 Our patient and her grandmother were happy with the explanation and did not seek further care.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shehnaz Zaman, MD, 420 Elmington Avenue, #417, Nashville, TN 37205; shehnazzaman@gmail.com

1. Ahkami RN, Schwartz RA. Nevus anemicus. Dermatology. 1999;198:327-329.

2. Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. Part 1. Hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:523-549.

3. Mountcastle EA, Diestelmeier MR, Lupton GP. Nevus anemicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:628-632.

4. Knoepp TG, Davis L. Nevus anemicus. e Medicine Web site. Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/derm/topic292.htm. Accessed October 13, 2007.

5. Hsu S. Photo quiz: white patch on back. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:1489-1490.

6. Greaves MW, Birkett D, Johnson C. Nevus anemicus: a unique catecholamine-dependent nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1970;102:172-176.

7. Wolff K, Johnson R, Suurmond R. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2005.

1. Ahkami RN, Schwartz RA. Nevus anemicus. Dermatology. 1999;198:327-329.

2. Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. Part 1. Hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:523-549.

3. Mountcastle EA, Diestelmeier MR, Lupton GP. Nevus anemicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:628-632.

4. Knoepp TG, Davis L. Nevus anemicus. e Medicine Web site. Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/derm/topic292.htm. Accessed October 13, 2007.

5. Hsu S. Photo quiz: white patch on back. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:1489-1490.

6. Greaves MW, Birkett D, Johnson C. Nevus anemicus: a unique catecholamine-dependent nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1970;102:172-176.

7. Wolff K, Johnson R, Suurmond R. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2005.

Pruritus in pregnancy

A 32-year-old mother of 2 came into our facility during her 31st week of pregnancy and told us that she couldn’t stop itching. She said that her whole body was itchy and it got worse at night. She was unable to get a good night’s sleep. Up until this point, her pregnancy had been uncomplicated and she had no past history of medical problems.

An examination revealed excoriations—but no blistering—on her abdomen, chest, arms, and legs (FIGURES 1 AND 2). She had no jaundice or scleral icterus. The fundal height was 31 mm and the fetal heart tones were 150 bpm.

FIGURE 1 & 2

Excoriations on the abdomen and chest

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is caused by maternal intrahepatic bile secretory dysfunction.1 The disorder, which is also referred to as obstetric cholestasis and pruritus gravidarum, has no primary skin lesions. Patients have generalized pruritus and secondary excoriations (FIGURE 3). In about 20% of cases, patients are also jaundiced.2

The sudden onset of generalized pruritus, which is the hallmark of ICP, starts during the late second (20%) or third (80%) trimester, followed by secondary skin lesions, namely linear excoriations and excoriated papules caused by scratching.3 These excoriations are typically localized on the extensor surfaces of the limbs, but may also be found on the abdomen and back. The itching may involve the palms and soles, as well. The severity of the skin lesions correlates with the duration and degree of pruritus.3

According to one study, ICP occurred in 0.5% of 3192 pregnancies. The disorder resolves after delivery, and recurs with subsequent pregnancies.4

ICP has been linked to fetal distress (20%–30%), stillbirths (1%–2%), and preterm delivery (20%–60%).3 Autopsies of the placenta have shown signs of acute anoxia. Fetal complications in ICP may be caused by decreased fetal elimination of toxic bile acids.3

Hormones, genes, and even the weather may play a role

Increased hormone production during pregnancy plays a role in ICP. Estrogen, which increases 100-fold during pregnancy, interferes with bile acid secretion across the basolateral and canalicular membrane of the hepatocyte. Particularly noteworthy is the fact that estriol-16 α-D-glucuronide, the estrogen metabolite that increases most during pregnancy, is cholestatic, according to animal studies.3 In addition, progesterone metabolites play an important part in the pathogenesis of ICP. Progesterone inhibits hepatic glucuronyl transferase, thereby reducing the clearance of estrogens and amplifying their effects.

Familial clustering and geographical variation indicate that there is a genetic predisposition for ICP. There is a high prevalence of ICP in Chile (14%), especially among Araucanian Indian women (24%), and in Bolivia.3 ICP patients may have a family history of cholelithiasis and a higher risk of gallstones. There is a family history of cholelithiasis in 50% of ICP cases.2

Exogenous factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of ICP. There is a higher incidence of ICP during the winter. Low selenium levels have also been linked to ICP. This suggests that the environment and nutritional factors play a role.2

FIGURE 3

Excoriations down the legs

The differential Dx includes scabies

Itching has been reported to occur in 17% of pregnancies,2 so it is important to differentiate ICP from the conditions listed below.

- Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy—also known as polymorphic eruption of pregnancy—is a dermatosis of pregnancy. Unlike the excoriations of ICP, this condition involves papulovesicular or urticarial eruptions on the trunk and extremities. It is particularly pronounced around the abdominal striae, and is more common in nulliparous women.

- Pemphigoid gestationis, also known as herpes gestationis because of its appearance, is a bullous or blistering disease that is associated with pregnancy. It is often periumbilical and can also have target lesions, which are absent in ICP.

- Atopic eruption of pregnancy is a new term used to include previous non-specific diagnoses such as prurigo of pregnancy and pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy. Prurigo of pregnancy, which is also called Besnier’s prurigo gestationis, involves bite-like papules that resemble scabies. Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy is characterized by red, follicle-based papules. These 2 conditions differ from ICP in that there is no cholestasis and liver studies are normal. (In ICP, there is an elevation in liver enzymes and serum bile acids.)

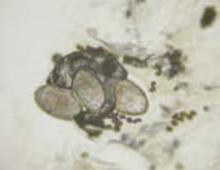

- Scabies infestation can occur during pregnancy. The mite burrows in the skin and produces severe itching between the fingers and in skin folds. Look for burrows and the typical distribution between the fingers, on the wrists, in the axilla, and around the waist. A positive scraping viewed under the microscope will show mites, eggs, and mite feces.

If you suspect ICP in a patient who is also jaundiced, you’ll also need to rule out several other conditions. These include:

- acute liver disease of pregnancy

- preeclampsia complicated by increased liver enzymes

- hyperemesis gravidarum

- viral hepatitis

- drug reaction

- obstructive biliary disease, such as a gallstone lodged in the common bile duct.

Order a blood chemistry or liver profile

If you suspect that your patient has ICP, start by ordering a blood chemistry or liver profile. If any of the liver tests are elevated, order a total bile acid level (which is the most sensitive indicator of ICP) and a hepatitis panel (or specific hepatitis tests based on the patient’s history of exposures and vaccinations). If there is laboratory evidence of cholestasis, a right upper quadrant ultrasound will help you to spot gallstones and evidence of obstruction.

In ICP, there will be mild abnormalities of the liver function tests, including transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin. Bilirubin may be mildly to moderately elevated (2–5 mg/dL). (Jaundice is seen only at the higher levels of bilirubin.) Our patient’s tests, for instance, revealed that her ALT and AST were both over 300; her total bilirubin was elevated at 2.1.

Serum levels of bile acid correlate with the severity of pruritus. Our patient’s bile acids were elevated and her hepatitis panel was negative. Her ultrasound showed gallstones, but we saw no obstruction. An ICP patient’s lipid profile may show mild elevations in total cholesterol and triglycerides, as was the case for our patient.

Malabsorption of fat may cause vitamin K deficiency resulting in a prolonged prothrombin time. Liver biopsy is unnecessary in suspected cases of ICP, but would show cholestatic changes such as dilated bile canaliculi, bile pigment in the parenchyma, and minimal inflammation.

Skin biopsy is not helpful in ICP

In suspected cases of ICP, skin biopsy will only reveal a spectrum of non-specific findings. It is, however, helpful if you suspect pemphigoid gestationis, since it will reveal subepidermal blisters. Similarly, biopsy for direct immunofluorescence is nonspecific in ICP, but helpful in pemphigoid gestationis.

Soothing baths can help, ursodiol is most effective

Mild cholestasis responds to symptomatic treatment with soothing baths, topical antipruritics, emollients, and primrose oil, among others. Antihistamines are rarely effective. Anion exchange resins, such as cholestyramine, can be helpful, too; they bind bile acids and decrease their enterohepatic circulation.2

Patients who do not respond to cholestyramine, or who cannot tolerate it, may be treated with ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol). The research indicates that ursodiol works faster than cholestyramine, has a more sustained effect on pruritus, and is more effective in improving the biochemical abnormalities of ICP (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on good-quality patient-oriented evidence). Ursodiol is considered safe for both mother and fetus.5 For all of these reasons, ursodiol has replaced cholestyramine as the first-line agent for ICP.

Doses range from 1 g/day to high doses of 1.5 to 2.0 g/d.6 The dose is maintained until delivery. Davies et al5 suggest that the use of ursodiol can reduce fetal mortality associated with ICP (SOR: C, based on consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series).

Weekly non-stress tests beginning at the 34th week of gestation are advisable (SOR: C).2 Labor may need to be induced in the 38th week in mild cases of ICP, and in the 36th week in severe cases (SOR: C).2

Ursodiol for our patient, labor was induced

We treated our patient with oral ursodiol and topical 1% hydrocortisone cream. Her bile acids and transaminase levels dropped and her pruritus improved—though it did not completely resolve until after delivery. Our obstetrics department recommended weekly non-stress tests starting at the 34th week of gestation. The non-stress tests were reactive. Due to the severity of her condition, labor was induced at 36 weeks.

Our patient had a healthy baby girl without complications. After delivery, the itching went away completely and her skin began to heal from all of those excoriations. Our patient is planning an elective cholecystectomy in the coming months because she doesn’t want to take a chance that she might have problems with her gallstones in the future.

Disclosure

1. Galaria NA, Mercurio MG. Dermatoses of pregnancy. The Female Patient 2003. Available at: www.femalepatient.com/html/arc/sel/may03/028_05_024.asp. Accessed on October 8, 2007.

2. Kroumpouzos G. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: what’s new. European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2002;16:316-318.

3. Ambros-Rudolph CM, Müllegger RR, Vaughan Jones SA, et al. The specific dermatoses of pregnancy revisited and reclassified: results of a retrospective two-center study on 505 pregnant patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:395-404.

4. Odom R, James W. Andrews’Diseases of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 2006.

5. Davies MH, da Silva RCMA, Jones SR, et al. Fetal mortality associated with cholestasis of pregnancy and the potential benefit of therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid. Gut 1995;37:580-584.

6. Mazzella G, Nicola R, Francesco A, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid administration in patients with cholestasis of pregnancy: Effects on primary bile acids in babies and mothers. Hepatology 2001;33:504-508.

A 32-year-old mother of 2 came into our facility during her 31st week of pregnancy and told us that she couldn’t stop itching. She said that her whole body was itchy and it got worse at night. She was unable to get a good night’s sleep. Up until this point, her pregnancy had been uncomplicated and she had no past history of medical problems.

An examination revealed excoriations—but no blistering—on her abdomen, chest, arms, and legs (FIGURES 1 AND 2). She had no jaundice or scleral icterus. The fundal height was 31 mm and the fetal heart tones were 150 bpm.

FIGURE 1 & 2

Excoriations on the abdomen and chest

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is caused by maternal intrahepatic bile secretory dysfunction.1 The disorder, which is also referred to as obstetric cholestasis and pruritus gravidarum, has no primary skin lesions. Patients have generalized pruritus and secondary excoriations (FIGURE 3). In about 20% of cases, patients are also jaundiced.2

The sudden onset of generalized pruritus, which is the hallmark of ICP, starts during the late second (20%) or third (80%) trimester, followed by secondary skin lesions, namely linear excoriations and excoriated papules caused by scratching.3 These excoriations are typically localized on the extensor surfaces of the limbs, but may also be found on the abdomen and back. The itching may involve the palms and soles, as well. The severity of the skin lesions correlates with the duration and degree of pruritus.3

According to one study, ICP occurred in 0.5% of 3192 pregnancies. The disorder resolves after delivery, and recurs with subsequent pregnancies.4

ICP has been linked to fetal distress (20%–30%), stillbirths (1%–2%), and preterm delivery (20%–60%).3 Autopsies of the placenta have shown signs of acute anoxia. Fetal complications in ICP may be caused by decreased fetal elimination of toxic bile acids.3

Hormones, genes, and even the weather may play a role

Increased hormone production during pregnancy plays a role in ICP. Estrogen, which increases 100-fold during pregnancy, interferes with bile acid secretion across the basolateral and canalicular membrane of the hepatocyte. Particularly noteworthy is the fact that estriol-16 α-D-glucuronide, the estrogen metabolite that increases most during pregnancy, is cholestatic, according to animal studies.3 In addition, progesterone metabolites play an important part in the pathogenesis of ICP. Progesterone inhibits hepatic glucuronyl transferase, thereby reducing the clearance of estrogens and amplifying their effects.

Familial clustering and geographical variation indicate that there is a genetic predisposition for ICP. There is a high prevalence of ICP in Chile (14%), especially among Araucanian Indian women (24%), and in Bolivia.3 ICP patients may have a family history of cholelithiasis and a higher risk of gallstones. There is a family history of cholelithiasis in 50% of ICP cases.2

Exogenous factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of ICP. There is a higher incidence of ICP during the winter. Low selenium levels have also been linked to ICP. This suggests that the environment and nutritional factors play a role.2

FIGURE 3

Excoriations down the legs

The differential Dx includes scabies

Itching has been reported to occur in 17% of pregnancies,2 so it is important to differentiate ICP from the conditions listed below.

- Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy—also known as polymorphic eruption of pregnancy—is a dermatosis of pregnancy. Unlike the excoriations of ICP, this condition involves papulovesicular or urticarial eruptions on the trunk and extremities. It is particularly pronounced around the abdominal striae, and is more common in nulliparous women.

- Pemphigoid gestationis, also known as herpes gestationis because of its appearance, is a bullous or blistering disease that is associated with pregnancy. It is often periumbilical and can also have target lesions, which are absent in ICP.

- Atopic eruption of pregnancy is a new term used to include previous non-specific diagnoses such as prurigo of pregnancy and pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy. Prurigo of pregnancy, which is also called Besnier’s prurigo gestationis, involves bite-like papules that resemble scabies. Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy is characterized by red, follicle-based papules. These 2 conditions differ from ICP in that there is no cholestasis and liver studies are normal. (In ICP, there is an elevation in liver enzymes and serum bile acids.)

- Scabies infestation can occur during pregnancy. The mite burrows in the skin and produces severe itching between the fingers and in skin folds. Look for burrows and the typical distribution between the fingers, on the wrists, in the axilla, and around the waist. A positive scraping viewed under the microscope will show mites, eggs, and mite feces.

If you suspect ICP in a patient who is also jaundiced, you’ll also need to rule out several other conditions. These include:

- acute liver disease of pregnancy

- preeclampsia complicated by increased liver enzymes

- hyperemesis gravidarum

- viral hepatitis

- drug reaction

- obstructive biliary disease, such as a gallstone lodged in the common bile duct.

Order a blood chemistry or liver profile

If you suspect that your patient has ICP, start by ordering a blood chemistry or liver profile. If any of the liver tests are elevated, order a total bile acid level (which is the most sensitive indicator of ICP) and a hepatitis panel (or specific hepatitis tests based on the patient’s history of exposures and vaccinations). If there is laboratory evidence of cholestasis, a right upper quadrant ultrasound will help you to spot gallstones and evidence of obstruction.

In ICP, there will be mild abnormalities of the liver function tests, including transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin. Bilirubin may be mildly to moderately elevated (2–5 mg/dL). (Jaundice is seen only at the higher levels of bilirubin.) Our patient’s tests, for instance, revealed that her ALT and AST were both over 300; her total bilirubin was elevated at 2.1.

Serum levels of bile acid correlate with the severity of pruritus. Our patient’s bile acids were elevated and her hepatitis panel was negative. Her ultrasound showed gallstones, but we saw no obstruction. An ICP patient’s lipid profile may show mild elevations in total cholesterol and triglycerides, as was the case for our patient.

Malabsorption of fat may cause vitamin K deficiency resulting in a prolonged prothrombin time. Liver biopsy is unnecessary in suspected cases of ICP, but would show cholestatic changes such as dilated bile canaliculi, bile pigment in the parenchyma, and minimal inflammation.

Skin biopsy is not helpful in ICP

In suspected cases of ICP, skin biopsy will only reveal a spectrum of non-specific findings. It is, however, helpful if you suspect pemphigoid gestationis, since it will reveal subepidermal blisters. Similarly, biopsy for direct immunofluorescence is nonspecific in ICP, but helpful in pemphigoid gestationis.

Soothing baths can help, ursodiol is most effective

Mild cholestasis responds to symptomatic treatment with soothing baths, topical antipruritics, emollients, and primrose oil, among others. Antihistamines are rarely effective. Anion exchange resins, such as cholestyramine, can be helpful, too; they bind bile acids and decrease their enterohepatic circulation.2