User login

Richard Quinn is an award-winning journalist with 15 years’ experience. He has worked at the Asbury Park Press in New Jersey and The Virginian-Pilot in Norfolk, Va., and currently is managing editor for a leading commercial real estate publication. His freelance work has appeared in The Jewish State, The Hospitalist, The Rheumatologist, ACEP Now, and ENT Today. He lives in New Jersey with his wife and three cats.

The Tablet Revolution

In his June 3 blog post at CIO.com, Tom Kaneshige asks: “Can the iPad cure what ails us?” He goes on to describe new applications for iPads in Texas hospitals, including the remote monitoring of patients’ EKGs by nurses roaming the hospital.

“The big revolution in tablet computing for hospitalists, which has been right around the corner for the past decade, hasn’t quite arrived yet,” says Russ Cucina, MD, MS, hospitalist and medical director of information technology at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center. “But I think we’re getting close, even though I’m not convinced that the iPad will be the vehicle.”

One of the hallmarks of such a technological revolution will be to free up hospitalists and other workers from computer work stations, where they are increasingly removed from face-to-face interactions. “Something gets lost in the name of efficiency,” Dr. Cucina says.

Hurdles to the tablet revolution include:

- Short battery life and the lack of rechargeable batteries. “Doctors need to be on the floor longer than eight hours,” Dr. Cucina says.

- Interacting with a tablet using thumbs and a touchscreen is fundamentally different from using a laptop, and applications should recognize the differences.

- Wireless access to secure electronic health records (EHR) throughout the hospital. “This is more of a cost issue than a technical problem,” Dr. Cucina explains. “It’s also incumbent upon us as physicians to develop good security practices with our tablets.”

- The skills to use the screen in the presence of others—in other words, What is the proper etiquette in front of care team members, patients, their families, etc.?

Hospitalists Look to Partner with New Quality Institute

Don’t be surprised if HM eventually gets a piece of the new Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

The center, funded through a $10 million gift from Johns Hopkins Medicine board of trustees chairman C. Michael Armstrong, will become the umbrella arm in charge of reducing preventable harm and improving healthcare quality.

Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University and director of Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center’s HM division, already sees that as hospitalist turf and could easily see HM partnering with the new institute. Dr. Howell, who already has reached out to the institute’s head, checklist guru Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, wrote in an email to The Hospitalist: “Hospitalists at Hopkins have a long tradition of exactly this type of work.”

Dr. Howell points to recent HM-driven research and initiatives to reduce “red alerts,” the term for ambulance diversions in the ICU, and streamlining the admission process to allow outpatient doctors to bypass the ED for patients for whom hospitalist admission is needed. At Howard County General Hospital, a suburb about 15 miles southwest of Baltimore, the HM group is running all rapid response team (RRT) events.

“In short,” Dr. Howell writes, “the Armstrong Institute will find hospitalists to be a willing partner.”

Hospitalists Must Prepare for Primary-Care Shortfalls

The Milwaukee-based American Society for Quality (ASQ) recently surveyed healthcare quality professionals about anticipated shortages of primary-care physicians (PCPs) and other medical staff, particularly as more Americans gain health insurance under the Accountable Care Act and Medicare). The trend is real, says Joseph Fortuna, MD, chair of ASQ’s Health Care Division, and hospitalists will face challenges in discharging patients who lack a defined PCP.

Survey respondents highlighted some strategies for dealing with the primary-care shortage, including the EHR for improving efficiency, teamwork, and checklists. Dr. Fortuna suggests HM groups:

- Work with PCPs and federally qualified health centers to enhance integrated relationships and improve handoffs. Local public health departments will be important collaborators.

- Define quality not just clinically, but also in terms of financial, operational, and cultural domains, using techniques of change management, root cause analysis, and other quality tools.

- Be involved in patient-centered medical homes as “catalysts, coordinators, and facilitators.”

HM Group Redesigns Workflow to Comply with ACGME Rules and Improve Continuity

As academic HM groups react to the new Accreditation Council for Graduation Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines on how long residents can work, they might want to keep the Toyota Production System (TPS) in mind.

Diana Mancini, MD, a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and associate program director of the University of Colorado Internal Medicine Residency, presented data in the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes competition at HM11 that showed how the use of continuous workflow and standardized tasks—hallmarks of TPS—helped redesign the medicine ward system to both comply with the ACGME rules and improve continuity of care.

The project replaced the traditional call system, and its corresponding floats and moonlighters, with a shift system comprised of two teams of six interns and three residents. At night, one intern worked a “continuity shift.” Using administrative data, Dr. Mancini and colleagues projected that 89% of patients admitted on a continuity shift would be discharged by the end of that intern’s five consecutive shifts. And, by dividing admissions among two teams, the “bolus” effect was halved, she says.

“The continuity shift is crucial for both the patient safety/continuity and educational content/value for the housestaff,” Dr. Mancini wrote in an email. “With the new work hours coming ... the hours would have to be adjusted … but the continuity could most certainly be maintained.”

Feds Delay Deadline for Stage 2 “Meaningful Use” Application Process

If your HM group is among the first cohort that reaches Stage 1 attestation this year for meaningful use of electronic health records (EHR), you may get more time to reach Stage 2. The federal Health Information Technology (HIT) policy committee has voted for a 12-month delay in implementing the criteria for that second stage, agreeing with those who say the current deadline of October 2013 “poses a nearly insurmountable timing challenge.”

The HIT is pushing to delay the deadline until 2014, which would mean providers have three years to verify that they have met Stage 1 meaningful use requirements, according to Government HealthIT. A cadre of medical trade groups, led by the AMA, is now pushing the Department of Health and Human Services to adopt the new timeline.

The ultimate decision rests with the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS).

By the numbers

Number of months without a central-line-associated bloodstream infection (BSI) on the eight-bed ICU at Beaufort Memorial Hospital, a 197-bed community hospital in Beaufort, S.C.

The hospital, which had a higher rate of BSIs than the national average in 2005, created a team to reduce its BSIs, led by infection-prevention specialist Beverly Yoder, RN, and involving hospitalists. Beaufort joined the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s 100K Lives Campaign and the South Carolina Hospital Association’s Stop BSI Project.

The team implemented a central-line “bundle” of quality practices, then simplified the bundle and incorporated it into its EHR. The unit celebrated its 30-month achievement with a luncheon in June.

For information, contact critical-care director Diane Razo, RN, MSN, PCCN, at drazo@bmhsc.org. (For more information about central-line infection prevention, visit SHM's Resource Room (www.hospitalmedicine.org/resource)

In his June 3 blog post at CIO.com, Tom Kaneshige asks: “Can the iPad cure what ails us?” He goes on to describe new applications for iPads in Texas hospitals, including the remote monitoring of patients’ EKGs by nurses roaming the hospital.

“The big revolution in tablet computing for hospitalists, which has been right around the corner for the past decade, hasn’t quite arrived yet,” says Russ Cucina, MD, MS, hospitalist and medical director of information technology at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center. “But I think we’re getting close, even though I’m not convinced that the iPad will be the vehicle.”

One of the hallmarks of such a technological revolution will be to free up hospitalists and other workers from computer work stations, where they are increasingly removed from face-to-face interactions. “Something gets lost in the name of efficiency,” Dr. Cucina says.

Hurdles to the tablet revolution include:

- Short battery life and the lack of rechargeable batteries. “Doctors need to be on the floor longer than eight hours,” Dr. Cucina says.

- Interacting with a tablet using thumbs and a touchscreen is fundamentally different from using a laptop, and applications should recognize the differences.

- Wireless access to secure electronic health records (EHR) throughout the hospital. “This is more of a cost issue than a technical problem,” Dr. Cucina explains. “It’s also incumbent upon us as physicians to develop good security practices with our tablets.”

- The skills to use the screen in the presence of others—in other words, What is the proper etiquette in front of care team members, patients, their families, etc.?

Hospitalists Look to Partner with New Quality Institute

Don’t be surprised if HM eventually gets a piece of the new Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

The center, funded through a $10 million gift from Johns Hopkins Medicine board of trustees chairman C. Michael Armstrong, will become the umbrella arm in charge of reducing preventable harm and improving healthcare quality.

Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University and director of Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center’s HM division, already sees that as hospitalist turf and could easily see HM partnering with the new institute. Dr. Howell, who already has reached out to the institute’s head, checklist guru Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, wrote in an email to The Hospitalist: “Hospitalists at Hopkins have a long tradition of exactly this type of work.”

Dr. Howell points to recent HM-driven research and initiatives to reduce “red alerts,” the term for ambulance diversions in the ICU, and streamlining the admission process to allow outpatient doctors to bypass the ED for patients for whom hospitalist admission is needed. At Howard County General Hospital, a suburb about 15 miles southwest of Baltimore, the HM group is running all rapid response team (RRT) events.

“In short,” Dr. Howell writes, “the Armstrong Institute will find hospitalists to be a willing partner.”

Hospitalists Must Prepare for Primary-Care Shortfalls

The Milwaukee-based American Society for Quality (ASQ) recently surveyed healthcare quality professionals about anticipated shortages of primary-care physicians (PCPs) and other medical staff, particularly as more Americans gain health insurance under the Accountable Care Act and Medicare). The trend is real, says Joseph Fortuna, MD, chair of ASQ’s Health Care Division, and hospitalists will face challenges in discharging patients who lack a defined PCP.

Survey respondents highlighted some strategies for dealing with the primary-care shortage, including the EHR for improving efficiency, teamwork, and checklists. Dr. Fortuna suggests HM groups:

- Work with PCPs and federally qualified health centers to enhance integrated relationships and improve handoffs. Local public health departments will be important collaborators.

- Define quality not just clinically, but also in terms of financial, operational, and cultural domains, using techniques of change management, root cause analysis, and other quality tools.

- Be involved in patient-centered medical homes as “catalysts, coordinators, and facilitators.”

HM Group Redesigns Workflow to Comply with ACGME Rules and Improve Continuity

As academic HM groups react to the new Accreditation Council for Graduation Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines on how long residents can work, they might want to keep the Toyota Production System (TPS) in mind.

Diana Mancini, MD, a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and associate program director of the University of Colorado Internal Medicine Residency, presented data in the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes competition at HM11 that showed how the use of continuous workflow and standardized tasks—hallmarks of TPS—helped redesign the medicine ward system to both comply with the ACGME rules and improve continuity of care.

The project replaced the traditional call system, and its corresponding floats and moonlighters, with a shift system comprised of two teams of six interns and three residents. At night, one intern worked a “continuity shift.” Using administrative data, Dr. Mancini and colleagues projected that 89% of patients admitted on a continuity shift would be discharged by the end of that intern’s five consecutive shifts. And, by dividing admissions among two teams, the “bolus” effect was halved, she says.

“The continuity shift is crucial for both the patient safety/continuity and educational content/value for the housestaff,” Dr. Mancini wrote in an email. “With the new work hours coming ... the hours would have to be adjusted … but the continuity could most certainly be maintained.”

Feds Delay Deadline for Stage 2 “Meaningful Use” Application Process

If your HM group is among the first cohort that reaches Stage 1 attestation this year for meaningful use of electronic health records (EHR), you may get more time to reach Stage 2. The federal Health Information Technology (HIT) policy committee has voted for a 12-month delay in implementing the criteria for that second stage, agreeing with those who say the current deadline of October 2013 “poses a nearly insurmountable timing challenge.”

The HIT is pushing to delay the deadline until 2014, which would mean providers have three years to verify that they have met Stage 1 meaningful use requirements, according to Government HealthIT. A cadre of medical trade groups, led by the AMA, is now pushing the Department of Health and Human Services to adopt the new timeline.

The ultimate decision rests with the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS).

By the numbers

Number of months without a central-line-associated bloodstream infection (BSI) on the eight-bed ICU at Beaufort Memorial Hospital, a 197-bed community hospital in Beaufort, S.C.

The hospital, which had a higher rate of BSIs than the national average in 2005, created a team to reduce its BSIs, led by infection-prevention specialist Beverly Yoder, RN, and involving hospitalists. Beaufort joined the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s 100K Lives Campaign and the South Carolina Hospital Association’s Stop BSI Project.

The team implemented a central-line “bundle” of quality practices, then simplified the bundle and incorporated it into its EHR. The unit celebrated its 30-month achievement with a luncheon in June.

For information, contact critical-care director Diane Razo, RN, MSN, PCCN, at drazo@bmhsc.org. (For more information about central-line infection prevention, visit SHM's Resource Room (www.hospitalmedicine.org/resource)

In his June 3 blog post at CIO.com, Tom Kaneshige asks: “Can the iPad cure what ails us?” He goes on to describe new applications for iPads in Texas hospitals, including the remote monitoring of patients’ EKGs by nurses roaming the hospital.

“The big revolution in tablet computing for hospitalists, which has been right around the corner for the past decade, hasn’t quite arrived yet,” says Russ Cucina, MD, MS, hospitalist and medical director of information technology at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center. “But I think we’re getting close, even though I’m not convinced that the iPad will be the vehicle.”

One of the hallmarks of such a technological revolution will be to free up hospitalists and other workers from computer work stations, where they are increasingly removed from face-to-face interactions. “Something gets lost in the name of efficiency,” Dr. Cucina says.

Hurdles to the tablet revolution include:

- Short battery life and the lack of rechargeable batteries. “Doctors need to be on the floor longer than eight hours,” Dr. Cucina says.

- Interacting with a tablet using thumbs and a touchscreen is fundamentally different from using a laptop, and applications should recognize the differences.

- Wireless access to secure electronic health records (EHR) throughout the hospital. “This is more of a cost issue than a technical problem,” Dr. Cucina explains. “It’s also incumbent upon us as physicians to develop good security practices with our tablets.”

- The skills to use the screen in the presence of others—in other words, What is the proper etiquette in front of care team members, patients, their families, etc.?

Hospitalists Look to Partner with New Quality Institute

Don’t be surprised if HM eventually gets a piece of the new Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

The center, funded through a $10 million gift from Johns Hopkins Medicine board of trustees chairman C. Michael Armstrong, will become the umbrella arm in charge of reducing preventable harm and improving healthcare quality.

Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University and director of Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center’s HM division, already sees that as hospitalist turf and could easily see HM partnering with the new institute. Dr. Howell, who already has reached out to the institute’s head, checklist guru Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, wrote in an email to The Hospitalist: “Hospitalists at Hopkins have a long tradition of exactly this type of work.”

Dr. Howell points to recent HM-driven research and initiatives to reduce “red alerts,” the term for ambulance diversions in the ICU, and streamlining the admission process to allow outpatient doctors to bypass the ED for patients for whom hospitalist admission is needed. At Howard County General Hospital, a suburb about 15 miles southwest of Baltimore, the HM group is running all rapid response team (RRT) events.

“In short,” Dr. Howell writes, “the Armstrong Institute will find hospitalists to be a willing partner.”

Hospitalists Must Prepare for Primary-Care Shortfalls

The Milwaukee-based American Society for Quality (ASQ) recently surveyed healthcare quality professionals about anticipated shortages of primary-care physicians (PCPs) and other medical staff, particularly as more Americans gain health insurance under the Accountable Care Act and Medicare). The trend is real, says Joseph Fortuna, MD, chair of ASQ’s Health Care Division, and hospitalists will face challenges in discharging patients who lack a defined PCP.

Survey respondents highlighted some strategies for dealing with the primary-care shortage, including the EHR for improving efficiency, teamwork, and checklists. Dr. Fortuna suggests HM groups:

- Work with PCPs and federally qualified health centers to enhance integrated relationships and improve handoffs. Local public health departments will be important collaborators.

- Define quality not just clinically, but also in terms of financial, operational, and cultural domains, using techniques of change management, root cause analysis, and other quality tools.

- Be involved in patient-centered medical homes as “catalysts, coordinators, and facilitators.”

HM Group Redesigns Workflow to Comply with ACGME Rules and Improve Continuity

As academic HM groups react to the new Accreditation Council for Graduation Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines on how long residents can work, they might want to keep the Toyota Production System (TPS) in mind.

Diana Mancini, MD, a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and associate program director of the University of Colorado Internal Medicine Residency, presented data in the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes competition at HM11 that showed how the use of continuous workflow and standardized tasks—hallmarks of TPS—helped redesign the medicine ward system to both comply with the ACGME rules and improve continuity of care.

The project replaced the traditional call system, and its corresponding floats and moonlighters, with a shift system comprised of two teams of six interns and three residents. At night, one intern worked a “continuity shift.” Using administrative data, Dr. Mancini and colleagues projected that 89% of patients admitted on a continuity shift would be discharged by the end of that intern’s five consecutive shifts. And, by dividing admissions among two teams, the “bolus” effect was halved, she says.

“The continuity shift is crucial for both the patient safety/continuity and educational content/value for the housestaff,” Dr. Mancini wrote in an email. “With the new work hours coming ... the hours would have to be adjusted … but the continuity could most certainly be maintained.”

Feds Delay Deadline for Stage 2 “Meaningful Use” Application Process

If your HM group is among the first cohort that reaches Stage 1 attestation this year for meaningful use of electronic health records (EHR), you may get more time to reach Stage 2. The federal Health Information Technology (HIT) policy committee has voted for a 12-month delay in implementing the criteria for that second stage, agreeing with those who say the current deadline of October 2013 “poses a nearly insurmountable timing challenge.”

The HIT is pushing to delay the deadline until 2014, which would mean providers have three years to verify that they have met Stage 1 meaningful use requirements, according to Government HealthIT. A cadre of medical trade groups, led by the AMA, is now pushing the Department of Health and Human Services to adopt the new timeline.

The ultimate decision rests with the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS).

By the numbers

Number of months without a central-line-associated bloodstream infection (BSI) on the eight-bed ICU at Beaufort Memorial Hospital, a 197-bed community hospital in Beaufort, S.C.

The hospital, which had a higher rate of BSIs than the national average in 2005, created a team to reduce its BSIs, led by infection-prevention specialist Beverly Yoder, RN, and involving hospitalists. Beaufort joined the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s 100K Lives Campaign and the South Carolina Hospital Association’s Stop BSI Project.

The team implemented a central-line “bundle” of quality practices, then simplified the bundle and incorporated it into its EHR. The unit celebrated its 30-month achievement with a luncheon in June.

For information, contact critical-care director Diane Razo, RN, MSN, PCCN, at drazo@bmhsc.org. (For more information about central-line infection prevention, visit SHM's Resource Room (www.hospitalmedicine.org/resource)

Hospitalist Heralds Shift-Based Work

While most academic hospitalist groups might be struggling with the practicalities of new resident work-hour rules, pediatric hospitalist Glenn Rosenbluth, MD, sees an opportunity if the rules spur a migration from traditional call models to shift-based work.

Dr. Rosenbluth and colleagues at University of California at San Francisco's (UCSF) Benioff Children's Hospital are working on research that shows a shift-based model that complies with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines can cut costs and reduce length of stay (LOS). The ACGME work-hour rules limit first-year residents to 16-hour shifts.

At UCSF Benioff, the traditional call model (with 30-hour shifts) was replaced by shift work in 2008. Medical inpatient teams now feature four interns working four-week blocks. Three weeks are scheduled as day shifts, with one week of night shifts.

"It's not that I think scheduling is the magic bullet," Dr. Rosenbluth says. "But I think scheduling can be leveraged."

In an abstract published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Rosenbluth and colleagues compared LOS and total cost for admitted patients diagnosed with the hospital's 10 most common pediatric diagnoses during the year before and after the schedule change. When the review was limited to non-ICU patients, LOS was reduced by 18% (rate ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73-0.93), and total costs were cut 10% (0.90; 95% CI,0.81-0.99). Dr. Rosenbluth says the model also has increased the staff's ownership of night patients, as interns moving from night shift to day shift will often see the same children.

Dr. Rosenbluth hopes to further his research to draw even more evidence-based conclusions. "I think shorter shifts are the way to go and I think our model shows that," he says. "I haven't proven that, but I do believe that. And that’s what we’re looking to study."

While most academic hospitalist groups might be struggling with the practicalities of new resident work-hour rules, pediatric hospitalist Glenn Rosenbluth, MD, sees an opportunity if the rules spur a migration from traditional call models to shift-based work.

Dr. Rosenbluth and colleagues at University of California at San Francisco's (UCSF) Benioff Children's Hospital are working on research that shows a shift-based model that complies with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines can cut costs and reduce length of stay (LOS). The ACGME work-hour rules limit first-year residents to 16-hour shifts.

At UCSF Benioff, the traditional call model (with 30-hour shifts) was replaced by shift work in 2008. Medical inpatient teams now feature four interns working four-week blocks. Three weeks are scheduled as day shifts, with one week of night shifts.

"It's not that I think scheduling is the magic bullet," Dr. Rosenbluth says. "But I think scheduling can be leveraged."

In an abstract published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Rosenbluth and colleagues compared LOS and total cost for admitted patients diagnosed with the hospital's 10 most common pediatric diagnoses during the year before and after the schedule change. When the review was limited to non-ICU patients, LOS was reduced by 18% (rate ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73-0.93), and total costs were cut 10% (0.90; 95% CI,0.81-0.99). Dr. Rosenbluth says the model also has increased the staff's ownership of night patients, as interns moving from night shift to day shift will often see the same children.

Dr. Rosenbluth hopes to further his research to draw even more evidence-based conclusions. "I think shorter shifts are the way to go and I think our model shows that," he says. "I haven't proven that, but I do believe that. And that’s what we’re looking to study."

While most academic hospitalist groups might be struggling with the practicalities of new resident work-hour rules, pediatric hospitalist Glenn Rosenbluth, MD, sees an opportunity if the rules spur a migration from traditional call models to shift-based work.

Dr. Rosenbluth and colleagues at University of California at San Francisco's (UCSF) Benioff Children's Hospital are working on research that shows a shift-based model that complies with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines can cut costs and reduce length of stay (LOS). The ACGME work-hour rules limit first-year residents to 16-hour shifts.

At UCSF Benioff, the traditional call model (with 30-hour shifts) was replaced by shift work in 2008. Medical inpatient teams now feature four interns working four-week blocks. Three weeks are scheduled as day shifts, with one week of night shifts.

"It's not that I think scheduling is the magic bullet," Dr. Rosenbluth says. "But I think scheduling can be leveraged."

In an abstract published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Rosenbluth and colleagues compared LOS and total cost for admitted patients diagnosed with the hospital's 10 most common pediatric diagnoses during the year before and after the schedule change. When the review was limited to non-ICU patients, LOS was reduced by 18% (rate ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73-0.93), and total costs were cut 10% (0.90; 95% CI,0.81-0.99). Dr. Rosenbluth says the model also has increased the staff's ownership of night patients, as interns moving from night shift to day shift will often see the same children.

Dr. Rosenbluth hopes to further his research to draw even more evidence-based conclusions. "I think shorter shifts are the way to go and I think our model shows that," he says. "I haven't proven that, but I do believe that. And that’s what we’re looking to study."

More Bed Space

Hospitalists might be able to save their institutions time and money by shuttling out patients who have a low risk for acute pulmonary embolism (PE), according to one researcher.

Donald Yealy, MD, chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, was among the authors of a new study that reported that in certain cases, "outpatient care can safely and effectively be used in place of inpatient care" (Lancet. 2011;378(9785):41-48).

Dr. Yealy says HM should pay close attention to the results, as patients moved to the outpatient setting clear bed space for more acute cases. "[Hospitalists] should identify low-risk patients and try as quickly as possible to return patients to the setting they prefer: their home," he says.

In a primary analysis, the international noninferiority trial reported that one of 171 outpatients (0.006%) developed recurrent VTE within 90 days compared with none of 168 inpatients (95% upper confidence limit [UCL] 2.7%; P=0.011). Mean length of stay was 0.5 days for outpatients, compared with 3.9 days.

Dr. Yealy notes that the next step for research is to determine which treatment to use for PE cases, as his study focused just on where the treatment was rendered. He also notes that the review focused only on patients diagnosed by ED physicians as having a PE severity index risk class 1 or 2. He compares potential future treatment therapies to those for cancer patients, for which "not everyone who has cancer has a high risk for terrible outcomes."

"All pulmonary emboli are not the same," Dr. Yealy adds. "If you use a strategy that identifies the lowest-risk patients, you have a lot of options. … We need to right-size our approach."

Hospitalists might be able to save their institutions time and money by shuttling out patients who have a low risk for acute pulmonary embolism (PE), according to one researcher.

Donald Yealy, MD, chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, was among the authors of a new study that reported that in certain cases, "outpatient care can safely and effectively be used in place of inpatient care" (Lancet. 2011;378(9785):41-48).

Dr. Yealy says HM should pay close attention to the results, as patients moved to the outpatient setting clear bed space for more acute cases. "[Hospitalists] should identify low-risk patients and try as quickly as possible to return patients to the setting they prefer: their home," he says.

In a primary analysis, the international noninferiority trial reported that one of 171 outpatients (0.006%) developed recurrent VTE within 90 days compared with none of 168 inpatients (95% upper confidence limit [UCL] 2.7%; P=0.011). Mean length of stay was 0.5 days for outpatients, compared with 3.9 days.

Dr. Yealy notes that the next step for research is to determine which treatment to use for PE cases, as his study focused just on where the treatment was rendered. He also notes that the review focused only on patients diagnosed by ED physicians as having a PE severity index risk class 1 or 2. He compares potential future treatment therapies to those for cancer patients, for which "not everyone who has cancer has a high risk for terrible outcomes."

"All pulmonary emboli are not the same," Dr. Yealy adds. "If you use a strategy that identifies the lowest-risk patients, you have a lot of options. … We need to right-size our approach."

Hospitalists might be able to save their institutions time and money by shuttling out patients who have a low risk for acute pulmonary embolism (PE), according to one researcher.

Donald Yealy, MD, chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, was among the authors of a new study that reported that in certain cases, "outpatient care can safely and effectively be used in place of inpatient care" (Lancet. 2011;378(9785):41-48).

Dr. Yealy says HM should pay close attention to the results, as patients moved to the outpatient setting clear bed space for more acute cases. "[Hospitalists] should identify low-risk patients and try as quickly as possible to return patients to the setting they prefer: their home," he says.

In a primary analysis, the international noninferiority trial reported that one of 171 outpatients (0.006%) developed recurrent VTE within 90 days compared with none of 168 inpatients (95% upper confidence limit [UCL] 2.7%; P=0.011). Mean length of stay was 0.5 days for outpatients, compared with 3.9 days.

Dr. Yealy notes that the next step for research is to determine which treatment to use for PE cases, as his study focused just on where the treatment was rendered. He also notes that the review focused only on patients diagnosed by ED physicians as having a PE severity index risk class 1 or 2. He compares potential future treatment therapies to those for cancer patients, for which "not everyone who has cancer has a high risk for terrible outcomes."

"All pulmonary emboli are not the same," Dr. Yealy adds. "If you use a strategy that identifies the lowest-risk patients, you have a lot of options. … We need to right-size our approach."

No Change in Statin Usage

A new study that links intensive-dose statin therapy to increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus is unlikely to convince HM or any other specialty to discontinue the treatment, a hospitalist focused on glycemic issues says.

A recent JAMA article reports that a meta-analysis of five clinical trials showed intensive statin regimen was associated with a 12% increased diabetes incidence over moderate-dose regimens (JAMA. 2011;305(24):2556-2564). The authors found that it would take 498 patients taking a statin to cause one extra case of diabetes. Conversely, only 155 people taking a statin would prevent one heart attack.

“The benefits of statins are just too well documented to ignore,” says Steven C. Smith, MD, FHM, medical director of hospitalist services at Healthcare Authority for Medical West in Bessemer, Ala. Quoting a cardiologist colleague, he adds, “statins are so beneficial, there is no way I wouldn’t use them because of a higher risk for diabetes.”

Dr. Smith, who leads the SHM-sponsored Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation program at his hospital, says the research is a formal link for what many hospitalists already realize: patients taking statins because of cardiovascular risk factors usually are at risk for diabetes. He adds that “modifiable risk factors”—including sedentary lifestyle, weight issues and diet—are prevalent in both patient groups. He refers to the JAMA research as “the last stone on the scale that tips the scale.”

“You have to weigh one versus the other,” Dr. Smith says. “The population of people on statins are already at risk for diabetes...you really have to address the risk factors that will solve both problems.”

A new study that links intensive-dose statin therapy to increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus is unlikely to convince HM or any other specialty to discontinue the treatment, a hospitalist focused on glycemic issues says.

A recent JAMA article reports that a meta-analysis of five clinical trials showed intensive statin regimen was associated with a 12% increased diabetes incidence over moderate-dose regimens (JAMA. 2011;305(24):2556-2564). The authors found that it would take 498 patients taking a statin to cause one extra case of diabetes. Conversely, only 155 people taking a statin would prevent one heart attack.

“The benefits of statins are just too well documented to ignore,” says Steven C. Smith, MD, FHM, medical director of hospitalist services at Healthcare Authority for Medical West in Bessemer, Ala. Quoting a cardiologist colleague, he adds, “statins are so beneficial, there is no way I wouldn’t use them because of a higher risk for diabetes.”

Dr. Smith, who leads the SHM-sponsored Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation program at his hospital, says the research is a formal link for what many hospitalists already realize: patients taking statins because of cardiovascular risk factors usually are at risk for diabetes. He adds that “modifiable risk factors”—including sedentary lifestyle, weight issues and diet—are prevalent in both patient groups. He refers to the JAMA research as “the last stone on the scale that tips the scale.”

“You have to weigh one versus the other,” Dr. Smith says. “The population of people on statins are already at risk for diabetes...you really have to address the risk factors that will solve both problems.”

A new study that links intensive-dose statin therapy to increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus is unlikely to convince HM or any other specialty to discontinue the treatment, a hospitalist focused on glycemic issues says.

A recent JAMA article reports that a meta-analysis of five clinical trials showed intensive statin regimen was associated with a 12% increased diabetes incidence over moderate-dose regimens (JAMA. 2011;305(24):2556-2564). The authors found that it would take 498 patients taking a statin to cause one extra case of diabetes. Conversely, only 155 people taking a statin would prevent one heart attack.

“The benefits of statins are just too well documented to ignore,” says Steven C. Smith, MD, FHM, medical director of hospitalist services at Healthcare Authority for Medical West in Bessemer, Ala. Quoting a cardiologist colleague, he adds, “statins are so beneficial, there is no way I wouldn’t use them because of a higher risk for diabetes.”

Dr. Smith, who leads the SHM-sponsored Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation program at his hospital, says the research is a formal link for what many hospitalists already realize: patients taking statins because of cardiovascular risk factors usually are at risk for diabetes. He adds that “modifiable risk factors”—including sedentary lifestyle, weight issues and diet—are prevalent in both patient groups. He refers to the JAMA research as “the last stone on the scale that tips the scale.”

“You have to weigh one versus the other,” Dr. Smith says. “The population of people on statins are already at risk for diabetes...you really have to address the risk factors that will solve both problems.”

How High Can Your Support Payments Go?

Last December, St. Peter’s Hospital, a 122-bed acute-care facility in Helena, Mont., crossed a symbolic line in the decade-long evolution of the financial payments that hospitals have provided to HM groups to make up the gap that exists between the expenses of running a hospitalist service and the professional fees that generate its revenue.

Hospital administrators asked the outpatient providers at the Helena Physicians’ Clinic to pay nearly $400,000 per year to support the in-house HM service at St. Peter’s, according to a series of stories in the local paper, the Helena Independent Record. The fee was never instituted and, in fact, some Helena patients and physicians have questioned whether the high-stakes payment was part of a broader campaign for the hospital to take over the clinic, a process that culminated in March with the hospital’s purchase of the clinic’s building.

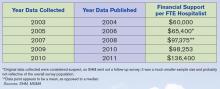

Still, the Montana case focused a spotlight on the doughnut hole of HM ledger sheets: hospital subsidies. More than 80% of HM groups took financial support from their host institutions in fiscal year 2010, according to new data from SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), which will be released in September. And the amount of that support has more than doubled, from $60,000 per full-time equivalent (FTE) in 2003-2004 to $136,400 per FTE in the latest data, according to a presentation at HM11 in May.

HM leaders agree the growth is unsustainable, particularly in the new world of healthcare reform, but they also concur that satisfaction with the benefits a hospitalist service offers make it unlikely other institutions will implement a fee-for-service system similar to that of St. Peter’s (see “Pay to Play?,” p. 38). As hospital administrators struggle to dole out pieces of their ever-shrinking financial pie, hospitalists also agree that they will find it more and more difficult to ask their C-suite for continually larger payments (see Figure 1, “Growth in Hospitalist Financial Support,” p. 37). Even when portrayed as “investments” in physicians that provide more than clinical care (e.g. hospitalists assuming leadership roles on hospital committees and pushing quality-improvement initiatives), a hospital’s bottom line can only afford so much.

“It’s not sustainable,” says Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners in Minneapolis and an SHM board member. “I think hospitals are pretty much tapped out by and large.

“What we’ve been seeing is practices have been able to ramp up their productivity, but people have also found other revenue streams, be it perioperative clinics, be it trying to find direct subsidies from specialty practices, be it educational funds for teaching. … We’re kind of entering a time when payment reform of some sort is going to have to come into play.”

History Lesson

Support payments have been around since HM’s earliest days, Dr. Kealey says. From the outset, it was difficult for most practices to cover their own salaries and expenses with reimbursement to the charges that make up the bulk of the field’s billing opportunities. “The economics of the situation are such that it is pretty difficult for a hospitalist to cover their own salary with the standard E/M codes,” he adds.

Hospitals, though, quickly realized that hospitalist practices were a valuable presence and created a payment stream to help offset the difference.

John Laverty, DHA, vice president of hospital-based physicians at HCA Physician Services in Nashville, Tenn., says four main factors drive the need for the hospitalist subsidy:

- Physician productivity. How many patients can a practice see on a daily or a monthly basis? Most averages teeter between 15 and 20 patients per day, often less in academic models. There is a mathematical point at which a group can generate enough revenue to cover costs, but many HM leaders say that comes at the cost of quality care delivery and physician satisfaction.

- Nonclinical/non-revenue-generating activities performed by hospitalists. HM groups usually are involved in QI and patient-safety initiatives, which, while important, are not necessarily captured by billing codes. Some HM contracts call for compensation tied to those activities, but many still do not, leaving groups with a gap to cover.

- Payor mix. A particularly difficult mix with high charity care and uninsured patients can lower the average net collected revenue per visit. There also is the choice between being a Medicaid participating provider or a nonparticipating provider with managed-care payors. So-called “non-par” providers typically have the ability to negotiate higher rates.

- Expenses. “How rich is your benefit package for your physicians?” Laverty asks. “Do you provide a retirement plan? Health, dental and vision? … Do you pay for CME?”

Dr. Kealey says it’s not “impossible” to cover all of a hospitalist’s costs through professional fees; however, “it usually requires a hospitalist be in an area with a very good payor mix or a hospital of very high efficiency, where they can see lots of patients. And often, there might be a setup where they aren’t covering unproductive times or tasks.”

Another Point of View

Not everyone thinks the subsidy is a fait accompli. Jeff Taylor, president and chief operating officer of IPC: The Hospitalist Co., a national physician group practice based in North Hollywood, Calif., says subsidies do not need to be a factor in a practice’s bottom line. Taylor says that IPC generates just 5% of its revenues from subsidies, with the remaining 95% financed by professional fees.

He attributes much of that to the work schedule, particularly the popular model of seven days on clinical duty followed by seven days off. He says that model has led to increased practice costs that then require financial support from their hospital. The schedule’s popularity is fueled by the balance it offers physicians between their work and personal lives, Taylor says, but it also means that practitioners working under it lose two weeks a month of billing opportunities.

He’s right about the popularity, as more than 70% of hospitalist groups use a shift-based staffing model, according to the State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. The number of HM groups employing call-based and hybrid coverage (some shift, some call) is 30%.

—Todd Nelson, MBA, technical director, Healthcare Financial Management Association, Chicago

“There is nothing else inherent in hospital medicine that makes this expensive, other than scheduling,” Taylor says. “Absent a very difficult payor mix, it’s the scheduling and the number of days worked that drives the cost. … We have been saying that for years, but we haven’t seen much of a waver yet. Once hospitals realize—some of them are starting to get it—that it’s the underlying work schedule that drives cost, they’re not going to continue to do it.”

Todd Nelson, MBA, a technical director at the Healthcare Financial Management Association in Chicago, agrees that the upward trajectory of hospital support payments will have to end, likely in concert with the expected payment reform of the next five years. But, he adds, the mere fact that hospital administrators have allowed the payments to double suggests that they view the support as an investment. In return for that money, though, C-suite members should contract for and then demand adherence to performance measures, he notes.

“Many specialties say, ‘We’re valuable; help us out,’ ” says Nelson, a former chief financial officer at Grinnell Regional Medical Center in Iowa. “In the hospital world, you can’t just ‘help out.’ They need to be providing a service you’re paying them for.”

SHM President Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, could not agree more. “The way I view monies that are sent to a group for nonclinical work is exactly that,” he says. “It’s compensation for nonclinical work. Subsidy, to me, seems to mean that despite whatever you’re doing, you need some more to pay because you can’t make your ends meet. That’s not true. What that figure is, for my group and for the vast majority of groups in this country, is really compensation for nonclinical efforts.”

HM groups should take it upon themselves to discuss their value contribution with their chief financial officer, as many in that position view hospitalist services as a “cost center” rather than as a means to the end of better financial performance for the institution as a whole, says Beth Hawley, senior vice president with Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent HMG.

“You need to look at it from the viewpoint of your CFO,” she says. “It is really important to educate your CFO on the myriad ways that your hospitalist program can create value for the hospital.”

—Jeff Taylor, president, COO, IPC: The Hospitalist Co., North Hollywood, Calif.

Hospitalist John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., says such education should highlight the intangible values of HM services, but it also needs to include firm, eye-opening data points. Put another way: “Have true ROI [return on investment], not soft ROI,” he says.

Dr. Bulger suggests pointing out that what some call a subsidy, he views as simply a payment, no different from the lump-sum check a hospital or healthcare system might cut for the group running its ED, or the check it writes for a cardiology specialty.

“There’s a subsidy for all those groups, but it’s never been looked at as a subsidy,” he adds. “But from a business perspective, it’s the same thing.”

The Future of Support

The relative value, justification, and existence of the support aside, the question remains: What is its future?

“Subsidies are not going to go away, because you can’t recruit and retain physicians in this environment for the most part without them,” says Troy Ahlstrom, MD, SFHM, CFO of Hospitalists of Northern Michigan, a hospitalist-owned and -managed group based in Traverse City. “Especially not when physicians coming out of residency have a desire to maintain a reasonable work and personal life, with fewer shifts where possible, fewer patients per shift. And they also have income goals that they have to maintain with that because they’re coming out of training with larger debt loads than ever before. That’s the tricky part for CMS and the federal government moving forward.”

Nelson, however, says that the future of support will be tied to payment reform, as bundled payments, value-based purchasing (VBP), and other initiatives to reduce overall healthcare spending are implemented. He said HM and other specialties should keep in mind that the point of reform is less overall spending, which translates to less support for everyone.

“When the pie shrinks, the table manners change,” he adds. “People are going to have to figure out how to slice that pie.”

Accountable-care organizations (ACOs) could be one answer. An ACO is a type of healthcare delivery model being piloted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), in which a group of providers band together to coordinate the care of beneficiaries (see “Quality over Quantity,” December 2009, p. 23). Reimbursement is shared by the group and is tied to the quality of care provided. Nelson says the model could significantly cut the need for support, as HM groups are allowed to share in the upside created by the ACO.

The program is set to go live Jan. 1, 2012, but a leading hospitalist already has questioned whether the proposed rules provide enough capitated risk and, therefore, whether the incentive is enough to spur adoption of the model and the potential support reductions it would bring.

“You can certainly start by taking a lower amount of risk, just upside risk,” Cogent HMG chief medical officer Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, SFHM, told The Hospitalist eWire in April, when the proposed rules were issued. “But your plan should be not to stay there. Your plan should be to take more and more risk as soon as you can, as soon as you’re capable.”

Nelson says that the support can continue in some form or fashion in the new models as long as the hospital and its practitioners are integrated and looking to achieve the same goal.

“The reality is, from the hospital perspective, you need to make sure you’re getting some value,” he says. “What are they buying in exchange for that [payment]?” TH

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Last December, St. Peter’s Hospital, a 122-bed acute-care facility in Helena, Mont., crossed a symbolic line in the decade-long evolution of the financial payments that hospitals have provided to HM groups to make up the gap that exists between the expenses of running a hospitalist service and the professional fees that generate its revenue.

Hospital administrators asked the outpatient providers at the Helena Physicians’ Clinic to pay nearly $400,000 per year to support the in-house HM service at St. Peter’s, according to a series of stories in the local paper, the Helena Independent Record. The fee was never instituted and, in fact, some Helena patients and physicians have questioned whether the high-stakes payment was part of a broader campaign for the hospital to take over the clinic, a process that culminated in March with the hospital’s purchase of the clinic’s building.

Still, the Montana case focused a spotlight on the doughnut hole of HM ledger sheets: hospital subsidies. More than 80% of HM groups took financial support from their host institutions in fiscal year 2010, according to new data from SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), which will be released in September. And the amount of that support has more than doubled, from $60,000 per full-time equivalent (FTE) in 2003-2004 to $136,400 per FTE in the latest data, according to a presentation at HM11 in May.

HM leaders agree the growth is unsustainable, particularly in the new world of healthcare reform, but they also concur that satisfaction with the benefits a hospitalist service offers make it unlikely other institutions will implement a fee-for-service system similar to that of St. Peter’s (see “Pay to Play?,” p. 38). As hospital administrators struggle to dole out pieces of their ever-shrinking financial pie, hospitalists also agree that they will find it more and more difficult to ask their C-suite for continually larger payments (see Figure 1, “Growth in Hospitalist Financial Support,” p. 37). Even when portrayed as “investments” in physicians that provide more than clinical care (e.g. hospitalists assuming leadership roles on hospital committees and pushing quality-improvement initiatives), a hospital’s bottom line can only afford so much.

“It’s not sustainable,” says Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners in Minneapolis and an SHM board member. “I think hospitals are pretty much tapped out by and large.

“What we’ve been seeing is practices have been able to ramp up their productivity, but people have also found other revenue streams, be it perioperative clinics, be it trying to find direct subsidies from specialty practices, be it educational funds for teaching. … We’re kind of entering a time when payment reform of some sort is going to have to come into play.”

History Lesson

Support payments have been around since HM’s earliest days, Dr. Kealey says. From the outset, it was difficult for most practices to cover their own salaries and expenses with reimbursement to the charges that make up the bulk of the field’s billing opportunities. “The economics of the situation are such that it is pretty difficult for a hospitalist to cover their own salary with the standard E/M codes,” he adds.

Hospitals, though, quickly realized that hospitalist practices were a valuable presence and created a payment stream to help offset the difference.

John Laverty, DHA, vice president of hospital-based physicians at HCA Physician Services in Nashville, Tenn., says four main factors drive the need for the hospitalist subsidy:

- Physician productivity. How many patients can a practice see on a daily or a monthly basis? Most averages teeter between 15 and 20 patients per day, often less in academic models. There is a mathematical point at which a group can generate enough revenue to cover costs, but many HM leaders say that comes at the cost of quality care delivery and physician satisfaction.

- Nonclinical/non-revenue-generating activities performed by hospitalists. HM groups usually are involved in QI and patient-safety initiatives, which, while important, are not necessarily captured by billing codes. Some HM contracts call for compensation tied to those activities, but many still do not, leaving groups with a gap to cover.

- Payor mix. A particularly difficult mix with high charity care and uninsured patients can lower the average net collected revenue per visit. There also is the choice between being a Medicaid participating provider or a nonparticipating provider with managed-care payors. So-called “non-par” providers typically have the ability to negotiate higher rates.

- Expenses. “How rich is your benefit package for your physicians?” Laverty asks. “Do you provide a retirement plan? Health, dental and vision? … Do you pay for CME?”

Dr. Kealey says it’s not “impossible” to cover all of a hospitalist’s costs through professional fees; however, “it usually requires a hospitalist be in an area with a very good payor mix or a hospital of very high efficiency, where they can see lots of patients. And often, there might be a setup where they aren’t covering unproductive times or tasks.”

Another Point of View

Not everyone thinks the subsidy is a fait accompli. Jeff Taylor, president and chief operating officer of IPC: The Hospitalist Co., a national physician group practice based in North Hollywood, Calif., says subsidies do not need to be a factor in a practice’s bottom line. Taylor says that IPC generates just 5% of its revenues from subsidies, with the remaining 95% financed by professional fees.

He attributes much of that to the work schedule, particularly the popular model of seven days on clinical duty followed by seven days off. He says that model has led to increased practice costs that then require financial support from their hospital. The schedule’s popularity is fueled by the balance it offers physicians between their work and personal lives, Taylor says, but it also means that practitioners working under it lose two weeks a month of billing opportunities.

He’s right about the popularity, as more than 70% of hospitalist groups use a shift-based staffing model, according to the State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. The number of HM groups employing call-based and hybrid coverage (some shift, some call) is 30%.

—Todd Nelson, MBA, technical director, Healthcare Financial Management Association, Chicago

“There is nothing else inherent in hospital medicine that makes this expensive, other than scheduling,” Taylor says. “Absent a very difficult payor mix, it’s the scheduling and the number of days worked that drives the cost. … We have been saying that for years, but we haven’t seen much of a waver yet. Once hospitals realize—some of them are starting to get it—that it’s the underlying work schedule that drives cost, they’re not going to continue to do it.”

Todd Nelson, MBA, a technical director at the Healthcare Financial Management Association in Chicago, agrees that the upward trajectory of hospital support payments will have to end, likely in concert with the expected payment reform of the next five years. But, he adds, the mere fact that hospital administrators have allowed the payments to double suggests that they view the support as an investment. In return for that money, though, C-suite members should contract for and then demand adherence to performance measures, he notes.

“Many specialties say, ‘We’re valuable; help us out,’ ” says Nelson, a former chief financial officer at Grinnell Regional Medical Center in Iowa. “In the hospital world, you can’t just ‘help out.’ They need to be providing a service you’re paying them for.”

SHM President Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, could not agree more. “The way I view monies that are sent to a group for nonclinical work is exactly that,” he says. “It’s compensation for nonclinical work. Subsidy, to me, seems to mean that despite whatever you’re doing, you need some more to pay because you can’t make your ends meet. That’s not true. What that figure is, for my group and for the vast majority of groups in this country, is really compensation for nonclinical efforts.”

HM groups should take it upon themselves to discuss their value contribution with their chief financial officer, as many in that position view hospitalist services as a “cost center” rather than as a means to the end of better financial performance for the institution as a whole, says Beth Hawley, senior vice president with Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent HMG.

“You need to look at it from the viewpoint of your CFO,” she says. “It is really important to educate your CFO on the myriad ways that your hospitalist program can create value for the hospital.”

—Jeff Taylor, president, COO, IPC: The Hospitalist Co., North Hollywood, Calif.

Hospitalist John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., says such education should highlight the intangible values of HM services, but it also needs to include firm, eye-opening data points. Put another way: “Have true ROI [return on investment], not soft ROI,” he says.

Dr. Bulger suggests pointing out that what some call a subsidy, he views as simply a payment, no different from the lump-sum check a hospital or healthcare system might cut for the group running its ED, or the check it writes for a cardiology specialty.

“There’s a subsidy for all those groups, but it’s never been looked at as a subsidy,” he adds. “But from a business perspective, it’s the same thing.”

The Future of Support

The relative value, justification, and existence of the support aside, the question remains: What is its future?

“Subsidies are not going to go away, because you can’t recruit and retain physicians in this environment for the most part without them,” says Troy Ahlstrom, MD, SFHM, CFO of Hospitalists of Northern Michigan, a hospitalist-owned and -managed group based in Traverse City. “Especially not when physicians coming out of residency have a desire to maintain a reasonable work and personal life, with fewer shifts where possible, fewer patients per shift. And they also have income goals that they have to maintain with that because they’re coming out of training with larger debt loads than ever before. That’s the tricky part for CMS and the federal government moving forward.”

Nelson, however, says that the future of support will be tied to payment reform, as bundled payments, value-based purchasing (VBP), and other initiatives to reduce overall healthcare spending are implemented. He said HM and other specialties should keep in mind that the point of reform is less overall spending, which translates to less support for everyone.

“When the pie shrinks, the table manners change,” he adds. “People are going to have to figure out how to slice that pie.”

Accountable-care organizations (ACOs) could be one answer. An ACO is a type of healthcare delivery model being piloted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), in which a group of providers band together to coordinate the care of beneficiaries (see “Quality over Quantity,” December 2009, p. 23). Reimbursement is shared by the group and is tied to the quality of care provided. Nelson says the model could significantly cut the need for support, as HM groups are allowed to share in the upside created by the ACO.

The program is set to go live Jan. 1, 2012, but a leading hospitalist already has questioned whether the proposed rules provide enough capitated risk and, therefore, whether the incentive is enough to spur adoption of the model and the potential support reductions it would bring.

“You can certainly start by taking a lower amount of risk, just upside risk,” Cogent HMG chief medical officer Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, SFHM, told The Hospitalist eWire in April, when the proposed rules were issued. “But your plan should be not to stay there. Your plan should be to take more and more risk as soon as you can, as soon as you’re capable.”

Nelson says that the support can continue in some form or fashion in the new models as long as the hospital and its practitioners are integrated and looking to achieve the same goal.

“The reality is, from the hospital perspective, you need to make sure you’re getting some value,” he says. “What are they buying in exchange for that [payment]?” TH

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Last December, St. Peter’s Hospital, a 122-bed acute-care facility in Helena, Mont., crossed a symbolic line in the decade-long evolution of the financial payments that hospitals have provided to HM groups to make up the gap that exists between the expenses of running a hospitalist service and the professional fees that generate its revenue.

Hospital administrators asked the outpatient providers at the Helena Physicians’ Clinic to pay nearly $400,000 per year to support the in-house HM service at St. Peter’s, according to a series of stories in the local paper, the Helena Independent Record. The fee was never instituted and, in fact, some Helena patients and physicians have questioned whether the high-stakes payment was part of a broader campaign for the hospital to take over the clinic, a process that culminated in March with the hospital’s purchase of the clinic’s building.

Still, the Montana case focused a spotlight on the doughnut hole of HM ledger sheets: hospital subsidies. More than 80% of HM groups took financial support from their host institutions in fiscal year 2010, according to new data from SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), which will be released in September. And the amount of that support has more than doubled, from $60,000 per full-time equivalent (FTE) in 2003-2004 to $136,400 per FTE in the latest data, according to a presentation at HM11 in May.

HM leaders agree the growth is unsustainable, particularly in the new world of healthcare reform, but they also concur that satisfaction with the benefits a hospitalist service offers make it unlikely other institutions will implement a fee-for-service system similar to that of St. Peter’s (see “Pay to Play?,” p. 38). As hospital administrators struggle to dole out pieces of their ever-shrinking financial pie, hospitalists also agree that they will find it more and more difficult to ask their C-suite for continually larger payments (see Figure 1, “Growth in Hospitalist Financial Support,” p. 37). Even when portrayed as “investments” in physicians that provide more than clinical care (e.g. hospitalists assuming leadership roles on hospital committees and pushing quality-improvement initiatives), a hospital’s bottom line can only afford so much.

“It’s not sustainable,” says Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners in Minneapolis and an SHM board member. “I think hospitals are pretty much tapped out by and large.

“What we’ve been seeing is practices have been able to ramp up their productivity, but people have also found other revenue streams, be it perioperative clinics, be it trying to find direct subsidies from specialty practices, be it educational funds for teaching. … We’re kind of entering a time when payment reform of some sort is going to have to come into play.”

History Lesson

Support payments have been around since HM’s earliest days, Dr. Kealey says. From the outset, it was difficult for most practices to cover their own salaries and expenses with reimbursement to the charges that make up the bulk of the field’s billing opportunities. “The economics of the situation are such that it is pretty difficult for a hospitalist to cover their own salary with the standard E/M codes,” he adds.

Hospitals, though, quickly realized that hospitalist practices were a valuable presence and created a payment stream to help offset the difference.

John Laverty, DHA, vice president of hospital-based physicians at HCA Physician Services in Nashville, Tenn., says four main factors drive the need for the hospitalist subsidy:

- Physician productivity. How many patients can a practice see on a daily or a monthly basis? Most averages teeter between 15 and 20 patients per day, often less in academic models. There is a mathematical point at which a group can generate enough revenue to cover costs, but many HM leaders say that comes at the cost of quality care delivery and physician satisfaction.

- Nonclinical/non-revenue-generating activities performed by hospitalists. HM groups usually are involved in QI and patient-safety initiatives, which, while important, are not necessarily captured by billing codes. Some HM contracts call for compensation tied to those activities, but many still do not, leaving groups with a gap to cover.

- Payor mix. A particularly difficult mix with high charity care and uninsured patients can lower the average net collected revenue per visit. There also is the choice between being a Medicaid participating provider or a nonparticipating provider with managed-care payors. So-called “non-par” providers typically have the ability to negotiate higher rates.

- Expenses. “How rich is your benefit package for your physicians?” Laverty asks. “Do you provide a retirement plan? Health, dental and vision? … Do you pay for CME?”

Dr. Kealey says it’s not “impossible” to cover all of a hospitalist’s costs through professional fees; however, “it usually requires a hospitalist be in an area with a very good payor mix or a hospital of very high efficiency, where they can see lots of patients. And often, there might be a setup where they aren’t covering unproductive times or tasks.”

Another Point of View

Not everyone thinks the subsidy is a fait accompli. Jeff Taylor, president and chief operating officer of IPC: The Hospitalist Co., a national physician group practice based in North Hollywood, Calif., says subsidies do not need to be a factor in a practice’s bottom line. Taylor says that IPC generates just 5% of its revenues from subsidies, with the remaining 95% financed by professional fees.

He attributes much of that to the work schedule, particularly the popular model of seven days on clinical duty followed by seven days off. He says that model has led to increased practice costs that then require financial support from their hospital. The schedule’s popularity is fueled by the balance it offers physicians between their work and personal lives, Taylor says, but it also means that practitioners working under it lose two weeks a month of billing opportunities.

He’s right about the popularity, as more than 70% of hospitalist groups use a shift-based staffing model, according to the State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. The number of HM groups employing call-based and hybrid coverage (some shift, some call) is 30%.

—Todd Nelson, MBA, technical director, Healthcare Financial Management Association, Chicago

“There is nothing else inherent in hospital medicine that makes this expensive, other than scheduling,” Taylor says. “Absent a very difficult payor mix, it’s the scheduling and the number of days worked that drives the cost. … We have been saying that for years, but we haven’t seen much of a waver yet. Once hospitals realize—some of them are starting to get it—that it’s the underlying work schedule that drives cost, they’re not going to continue to do it.”

Todd Nelson, MBA, a technical director at the Healthcare Financial Management Association in Chicago, agrees that the upward trajectory of hospital support payments will have to end, likely in concert with the expected payment reform of the next five years. But, he adds, the mere fact that hospital administrators have allowed the payments to double suggests that they view the support as an investment. In return for that money, though, C-suite members should contract for and then demand adherence to performance measures, he notes.

“Many specialties say, ‘We’re valuable; help us out,’ ” says Nelson, a former chief financial officer at Grinnell Regional Medical Center in Iowa. “In the hospital world, you can’t just ‘help out.’ They need to be providing a service you’re paying them for.”

SHM President Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, could not agree more. “The way I view monies that are sent to a group for nonclinical work is exactly that,” he says. “It’s compensation for nonclinical work. Subsidy, to me, seems to mean that despite whatever you’re doing, you need some more to pay because you can’t make your ends meet. That’s not true. What that figure is, for my group and for the vast majority of groups in this country, is really compensation for nonclinical efforts.”

HM groups should take it upon themselves to discuss their value contribution with their chief financial officer, as many in that position view hospitalist services as a “cost center” rather than as a means to the end of better financial performance for the institution as a whole, says Beth Hawley, senior vice president with Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent HMG.

“You need to look at it from the viewpoint of your CFO,” she says. “It is really important to educate your CFO on the myriad ways that your hospitalist program can create value for the hospital.”

—Jeff Taylor, president, COO, IPC: The Hospitalist Co., North Hollywood, Calif.

Hospitalist John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., says such education should highlight the intangible values of HM services, but it also needs to include firm, eye-opening data points. Put another way: “Have true ROI [return on investment], not soft ROI,” he says.

Dr. Bulger suggests pointing out that what some call a subsidy, he views as simply a payment, no different from the lump-sum check a hospital or healthcare system might cut for the group running its ED, or the check it writes for a cardiology specialty.

“There’s a subsidy for all those groups, but it’s never been looked at as a subsidy,” he adds. “But from a business perspective, it’s the same thing.”

The Future of Support

The relative value, justification, and existence of the support aside, the question remains: What is its future?

“Subsidies are not going to go away, because you can’t recruit and retain physicians in this environment for the most part without them,” says Troy Ahlstrom, MD, SFHM, CFO of Hospitalists of Northern Michigan, a hospitalist-owned and -managed group based in Traverse City. “Especially not when physicians coming out of residency have a desire to maintain a reasonable work and personal life, with fewer shifts where possible, fewer patients per shift. And they also have income goals that they have to maintain with that because they’re coming out of training with larger debt loads than ever before. That’s the tricky part for CMS and the federal government moving forward.”

Nelson, however, says that the future of support will be tied to payment reform, as bundled payments, value-based purchasing (VBP), and other initiatives to reduce overall healthcare spending are implemented. He said HM and other specialties should keep in mind that the point of reform is less overall spending, which translates to less support for everyone.

“When the pie shrinks, the table manners change,” he adds. “People are going to have to figure out how to slice that pie.”

Accountable-care organizations (ACOs) could be one answer. An ACO is a type of healthcare delivery model being piloted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), in which a group of providers band together to coordinate the care of beneficiaries (see “Quality over Quantity,” December 2009, p. 23). Reimbursement is shared by the group and is tied to the quality of care provided. Nelson says the model could significantly cut the need for support, as HM groups are allowed to share in the upside created by the ACO.

The program is set to go live Jan. 1, 2012, but a leading hospitalist already has questioned whether the proposed rules provide enough capitated risk and, therefore, whether the incentive is enough to spur adoption of the model and the potential support reductions it would bring.

“You can certainly start by taking a lower amount of risk, just upside risk,” Cogent HMG chief medical officer Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, SFHM, told The Hospitalist eWire in April, when the proposed rules were issued. “But your plan should be not to stay there. Your plan should be to take more and more risk as soon as you can, as soon as you’re capable.”

Nelson says that the support can continue in some form or fashion in the new models as long as the hospital and its practitioners are integrated and looking to achieve the same goal.

“The reality is, from the hospital perspective, you need to make sure you’re getting some value,” he says. “What are they buying in exchange for that [payment]?” TH

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Hospitalists discuss the time-honored tradition of hospital payments to HM groups

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Subsidy or Investment?

Branding is defined by Merriam-Webster as the promotion of a product or service tied to a particular brand. Most hospitalists say HM has done a good job branding itself as the go-to physician specialty for patient safety and quality-improvement (QI) initiatives.

But labeling the financial support payments that help pay for that service as a subsidy?

“It’s a horrible branding exercise,” says Troy Ahlstrom, MD, SFHM, chief financial officer of Hospitalists of Northern Michigan, a hospitalist-owned and -managed group based in Traverse City.

The monies that change hands between hospitals and HM groups have long been known as subsidies, with one consulting group’s marketing materials giving advice on why subsidies are necessary. Hospitalist John Bulger, DO, FACP, FHM, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., says the payments must be viewed the same as financial agreements with other specialties, which rarely are viewed as subsidies.