User login

Man, 57, With Dyspnea After Chiropractic Manipulation

A 57-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a two-day history of worsening shortness of breath, light-headedness, and back pain. The patient, who had a history of ankylosing spondylitis, had been receiving weekly therapy from a chiropractor for about 10 years. One week before presenting to the ED, he had begun to undergo daily manipulations under anesthesia (MUA)—an aggressive chiropractic procedure that is administered while the patient is under monitored, procedural sedation. After the second day of treatment, the patient began to experience worsening back pain and progressive light-headedness and shortness of breath.

At a follow-up visit with his chiropractor, he was found to have decreased O2 saturation and was directed to go to the hospital for evaluation. On arrival at the ED, the patient was awake and alert. He had intact motor strength in all extremities, no sensory abnormalities, intact symmetric reflexes, and no bladder or bowel dysfunction, with a negative Babinski sign. His O2 saturation was 92% on 5 L of oxygen. An absence of breath sounds was noted on the left side.

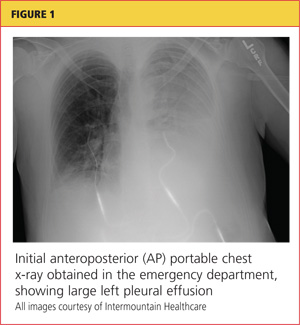

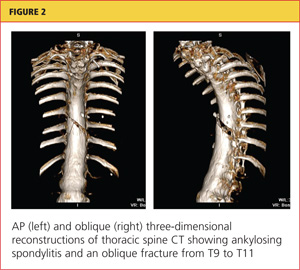

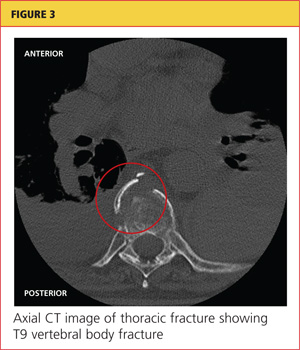

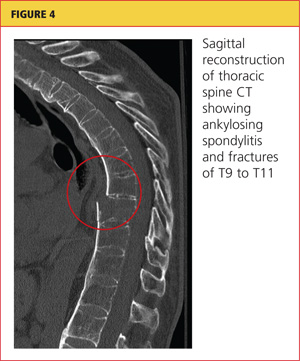

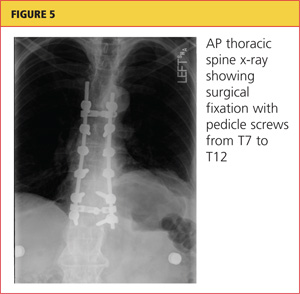

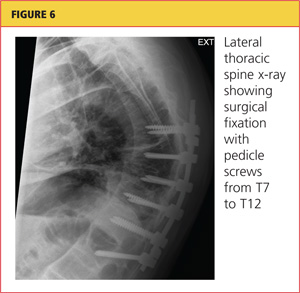

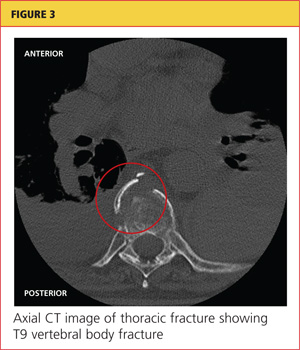

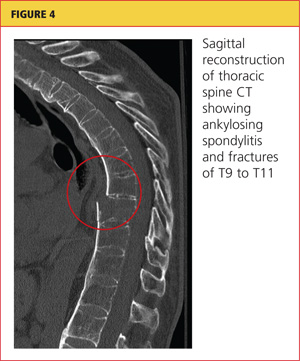

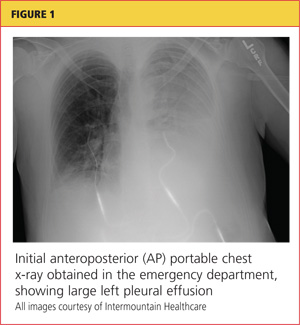

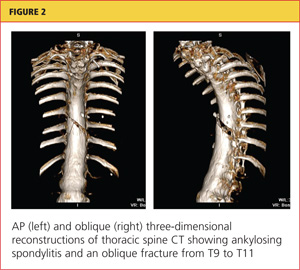

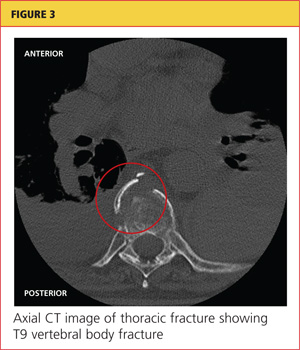

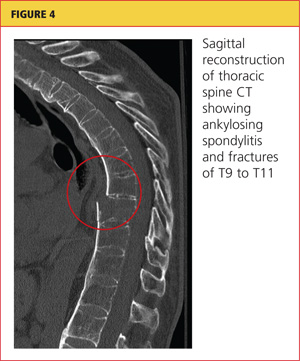

Chest x-ray (see Figure 1) was performed, which demonstrated complete opacification of the left hemithorax, consistent with a large pleural effusion or hemothorax. CT scan of the thoracic spine showed diffuse ankylosis. A complex oblique coronal and transversely oriented fracture with 7 mm of displacement was identified, beginning at the right anterior inferior lateral margin of the T8 vertebral body and extending centrally and inferiorly to the left and right into the T9 vertebral body. The fracture continued through the right T9-10 neural foramen and what was probably the right fused T9-10 facet joint. The fracture exited through the left superior and lateral margin of the T10 vertebral body and the left T10-11 neural foramen (see Figures 2, 3, and 4).

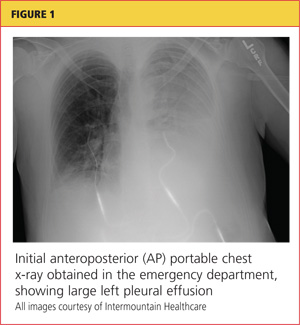

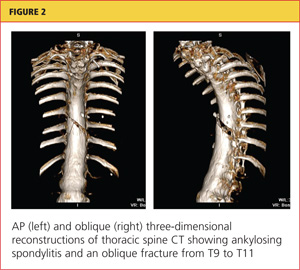

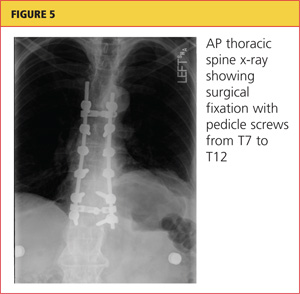

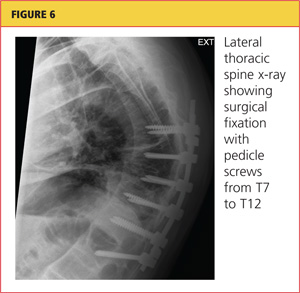

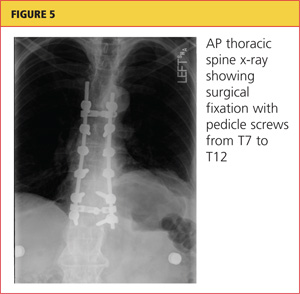

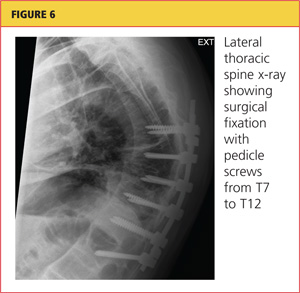

A chest tube was inserted in the ED, and 1,600 mL of old blood was immediately drained. The patient was admitted to the ICU on the trauma service. He was taken to surgery for open reduction and internal fixation of his unstable thoracic spine fracture on day 3 of hospitalization, after his pulmonary condition stabilized. Pedicle screws were placed from T7 through T12 during the spinal fusion. Good reduction of the fracture was observed following the spine surgery (see Figures 5 and 6). At the conclusion of surgery, an epidural catheter was placed in the thoracic spine to administer pain control.

After the spine portion of the procedure, the patient was repositioned and underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery of the left hemithorax for evacuation of retained hemothorax. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was taken to the ICU for recovery.

On postoperative day 2, the patient complained of chest pain and experienced hypoxemia with activity. CT angiography of the chest demonstrated bilateral segmental and subsegmental pulmonary emboli. The epidural catheter was discontinued. Six hours later, a heparin drip was started, and the patient was transitioned to therapeutic enoxaparin and warfarin. When methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) was detected in his hemothorax fluid, he was treated with a course of nafcillin.

The patient was discharged to home on postoperative day 12. He has remained neurologically intact and has returned to his former work activities. He is not taking narcotic pain medications.

Discussion

Chiropractic care is a popular alternative health care modality in the United States. Researchers for the 2007 National Health Interview Study1 reported an annual use of chiropractic manipulation of 8.6%, while the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey2 data yielded an estimate of 12.6 million adults using chiropractic manipulation in 2006—translating to a prevalence of 5.6%. Despite the popularity of chiropractic medicine, few well-designed studies have been conducted to support its use.3,4 Because of its designation as an alternative therapy, however, chiropractic manipulation has not been subjected to rigorous efficacy and safety evaluations.5

Given the inconsistency of the evidence to support chiropractic manipulation, the practice's safety profile is a concern. The risks associated with spinal manipulation are generally described in case reports and small series. Most serious adverse events described in the literature are cerebrovascular in nature and tend to occur after cervical manipulation.6,7 Fractures after spine manipulation are exceedingly rare, and published literature on this topic consists of a few isolated case reports, with all fractures occurring in the cervical spine in patients with an underlying pathologic condition.8-10

In 2009, Gouveia et al5 reviewed the published literature regarding all adverse events resulting from chiropractic manipulation. The authors found one randomized controlled trial, two case-control studies, six prospective studies, 12 surveys, three retrospective studies, and 100 case reports. The spectrum of complications identified ranged from benign and transient, such as local discomfort, to far more serious: stroke, myelopathy, radiculopathy, subdural hematoma, spinal fluid leakage, cauda equina syndrome, herniated disc, diaphragmatic palsy, and vertebral fractures. The authors were unable to perform a true meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity of the data, but they concluded that complications associated with chiropractic procedures are "frequent."5

Manipulations Under Anesthesia

MUA is a procedure that combines chiropractic adjustments and manipulations with general anesthesia or procedural sedation.11 The theory behind this strategy is that the anesthesia or sedation reduces pain and muscle spasm that may hinder the manipulation, allowing the practitioner to more effectively break up joint adhesions and reduce segmental dysfunction than if the patient had not undergone anesthesia.11

MUA is generally indicated in patients who have not responded to a 4- to 8-week trial of traditional manipulation therapy.12 It is also considered in patients who have "painful and restricting muscular guarding [that] interferes with the performance of spinal adjustments, mobilizations, and soft tissue release techniques."13

In the chiropractic literature, between 3% and 10% of patients are estimated to be candidates for MUA.12,14 It is not completely clear, however, what diagnoses are most likely to be treated successfully with this technique. Contraindications to MUA are generally the same as those for manipulation in conscious patients. A published list of contraindications from the Committee for Manipulation under Anesthesia (2003)15 included malignancy with bony metastasis, tuberculosis of the bone, recent fracture, acute arthritis, acute gout, diabetic neuropathy, syphilitic articular lesions, excessive spinal osteoporosis, disk fragmentation, direct nerve root impingement, and evidence of cord or caudal compression by tumor, ankylosis, or other space-occupying lesions.

MUA generally begins with deep procedural sedation, managed by an anesthesiologist. Once an adequate level of sedation is achieved, the manipulations are performed. Both high- and low-velocity thrusts are used, but it is recommended that the force exerted should be much less, and the manipulations performed with more caution, than in patients who are not anesthetized.12

For the thoracic spine, the patient is manipulated in the supine position with the arms crossed over the chest. The practitioner places one hand in a fist under the spine with the other hand on the patient's crossed arms, then delivers an anterior-to-posterior thrust. This is repeated until all affected segments have been treated.11,12

Literature to support the use of MUA for various indications is largely anecdotal. The largest published series13 is of 177 patients with chronic spinal pain who each underwent three MUA sessions followed by four to six weeks of traditional manipulations. The authors found that pain, as measured by visual analog scale, was reduced by 62% in patients with cervical spine pain, and by 60% in patients with lumbar pain. No adverse events were reported in the study.

Kohlbeck and Haldeman12 reviewed the reported complications of MUA across all published literature. They found that in 17 published papers, the overall complication rate was 0.7%, mainly represented by transitory increased pain. No spinal fractures were reported.

This case demonstrates a rare but serious complication of chiropractic MUA. It is unclear exactly what mechanism of injury led to an unstable thoracic spine fracture with massive hemothorax, and the precise cause will probably never be known. The clinicians who treated the case patient find it curious that the reported rate of adverse events following this procedure is so low, but they suspect an element of reporting bias in the chiropractic literature.

Conclusion

Iatrogenic injury after chiropractic manipulation is uncommon, but it can be devastating. Few serious complications of chiropractic MUA have been reported, but the literature is lacking in well-designed research studies. Despite the dearth of clinical trials to support its safety and efficacy, use of MUA has continued in the chiropractic community. This case demonstrates that serious adverse outcomes can occur, and more rigorous studies are needed to delineate the true benefits and risks of this set of chiropractic procedures.

References

1. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;12:1-9.

2. Davis MA, Sirovich BE, Weeks WB. Utilization and expenditures on chiropractic care in the United States from 1997 to 2006. Health Serv Res. 2009;45:748-761.

3. Canadian Chiropractic Association; Canadian Federation of Chiropractic Regulatory Boards; Clinical Practice Guidelines Development Initiative; Guidelines Development Committee. Chiropractic clinical practice guideline: evidence-based treatment of adult neck pain not due to whiplash. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2005;49:417-421.

4.

Hurwitz EL, Aker PD, Adams AH, et al. Manipulation and mobilization of the cervical spine: a systematic review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:1746-1760.

5.Gouveia LO, Castanho P, Ferreira JJ. Safety of chiropractic interventions: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:E405-E413.

6. Di Fabio RP. Manipulation of the cervical spine: risks and benefits. Phys Ther. 1999;79:50-65.

7. Nadareishvili Z, Norris JW. Stroke from traumatic arterial dissection. Lancet. 1999;354:159-160.

8. Austin RT. Pathological vertebral fractures after spinal manipulation. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291:1114-1115.

9. Ea HK, Weber AJ, Yon F, Lioté F. Osteoporotic fracture of the dens revealed by cervical manipulation. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:246-250.

10. Schmitz A, Lutterbey G, von Engelhardt L, et al. Pathological cervical fracture after spinal manipulation in a pregnant patient. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:633-636.

11. Cremata E, Collins S, Clauson W, et al. Manipulation under anesthesia: a report of four cases. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:526-533.

12. Kohlbeck FJ, Haldeman S. Medication-assisted spinal manipulation. Spine J. 2002;2:288-302.

13. West DT, Mathews RS, Miller MR, Kent GM. Effective management of spinal pain in one hundred seventy-seven patients evaluated for manipulation under anesthesia. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22:299-308.

14. Morey LW Jr. Osteopathic manipulation under general anesthesia. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1973;73:116-127.

15. Tain L, Gunderson C, Cremata E, et al; Committee for Manipulation Under Anesthesia. Recommendations to the Industrial Medical Council Work Group of California for manipulation under anesthesia use for injured workers. Sacramento, CA: Industrial Medical Council; 2003.

A 57-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a two-day history of worsening shortness of breath, light-headedness, and back pain. The patient, who had a history of ankylosing spondylitis, had been receiving weekly therapy from a chiropractor for about 10 years. One week before presenting to the ED, he had begun to undergo daily manipulations under anesthesia (MUA)—an aggressive chiropractic procedure that is administered while the patient is under monitored, procedural sedation. After the second day of treatment, the patient began to experience worsening back pain and progressive light-headedness and shortness of breath.

At a follow-up visit with his chiropractor, he was found to have decreased O2 saturation and was directed to go to the hospital for evaluation. On arrival at the ED, the patient was awake and alert. He had intact motor strength in all extremities, no sensory abnormalities, intact symmetric reflexes, and no bladder or bowel dysfunction, with a negative Babinski sign. His O2 saturation was 92% on 5 L of oxygen. An absence of breath sounds was noted on the left side.

Chest x-ray (see Figure 1) was performed, which demonstrated complete opacification of the left hemithorax, consistent with a large pleural effusion or hemothorax. CT scan of the thoracic spine showed diffuse ankylosis. A complex oblique coronal and transversely oriented fracture with 7 mm of displacement was identified, beginning at the right anterior inferior lateral margin of the T8 vertebral body and extending centrally and inferiorly to the left and right into the T9 vertebral body. The fracture continued through the right T9-10 neural foramen and what was probably the right fused T9-10 facet joint. The fracture exited through the left superior and lateral margin of the T10 vertebral body and the left T10-11 neural foramen (see Figures 2, 3, and 4).

A chest tube was inserted in the ED, and 1,600 mL of old blood was immediately drained. The patient was admitted to the ICU on the trauma service. He was taken to surgery for open reduction and internal fixation of his unstable thoracic spine fracture on day 3 of hospitalization, after his pulmonary condition stabilized. Pedicle screws were placed from T7 through T12 during the spinal fusion. Good reduction of the fracture was observed following the spine surgery (see Figures 5 and 6). At the conclusion of surgery, an epidural catheter was placed in the thoracic spine to administer pain control.

After the spine portion of the procedure, the patient was repositioned and underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery of the left hemithorax for evacuation of retained hemothorax. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was taken to the ICU for recovery.

On postoperative day 2, the patient complained of chest pain and experienced hypoxemia with activity. CT angiography of the chest demonstrated bilateral segmental and subsegmental pulmonary emboli. The epidural catheter was discontinued. Six hours later, a heparin drip was started, and the patient was transitioned to therapeutic enoxaparin and warfarin. When methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) was detected in his hemothorax fluid, he was treated with a course of nafcillin.

The patient was discharged to home on postoperative day 12. He has remained neurologically intact and has returned to his former work activities. He is not taking narcotic pain medications.

Discussion

Chiropractic care is a popular alternative health care modality in the United States. Researchers for the 2007 National Health Interview Study1 reported an annual use of chiropractic manipulation of 8.6%, while the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey2 data yielded an estimate of 12.6 million adults using chiropractic manipulation in 2006—translating to a prevalence of 5.6%. Despite the popularity of chiropractic medicine, few well-designed studies have been conducted to support its use.3,4 Because of its designation as an alternative therapy, however, chiropractic manipulation has not been subjected to rigorous efficacy and safety evaluations.5

Given the inconsistency of the evidence to support chiropractic manipulation, the practice's safety profile is a concern. The risks associated with spinal manipulation are generally described in case reports and small series. Most serious adverse events described in the literature are cerebrovascular in nature and tend to occur after cervical manipulation.6,7 Fractures after spine manipulation are exceedingly rare, and published literature on this topic consists of a few isolated case reports, with all fractures occurring in the cervical spine in patients with an underlying pathologic condition.8-10

In 2009, Gouveia et al5 reviewed the published literature regarding all adverse events resulting from chiropractic manipulation. The authors found one randomized controlled trial, two case-control studies, six prospective studies, 12 surveys, three retrospective studies, and 100 case reports. The spectrum of complications identified ranged from benign and transient, such as local discomfort, to far more serious: stroke, myelopathy, radiculopathy, subdural hematoma, spinal fluid leakage, cauda equina syndrome, herniated disc, diaphragmatic palsy, and vertebral fractures. The authors were unable to perform a true meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity of the data, but they concluded that complications associated with chiropractic procedures are "frequent."5

Manipulations Under Anesthesia

MUA is a procedure that combines chiropractic adjustments and manipulations with general anesthesia or procedural sedation.11 The theory behind this strategy is that the anesthesia or sedation reduces pain and muscle spasm that may hinder the manipulation, allowing the practitioner to more effectively break up joint adhesions and reduce segmental dysfunction than if the patient had not undergone anesthesia.11

MUA is generally indicated in patients who have not responded to a 4- to 8-week trial of traditional manipulation therapy.12 It is also considered in patients who have "painful and restricting muscular guarding [that] interferes with the performance of spinal adjustments, mobilizations, and soft tissue release techniques."13

In the chiropractic literature, between 3% and 10% of patients are estimated to be candidates for MUA.12,14 It is not completely clear, however, what diagnoses are most likely to be treated successfully with this technique. Contraindications to MUA are generally the same as those for manipulation in conscious patients. A published list of contraindications from the Committee for Manipulation under Anesthesia (2003)15 included malignancy with bony metastasis, tuberculosis of the bone, recent fracture, acute arthritis, acute gout, diabetic neuropathy, syphilitic articular lesions, excessive spinal osteoporosis, disk fragmentation, direct nerve root impingement, and evidence of cord or caudal compression by tumor, ankylosis, or other space-occupying lesions.

MUA generally begins with deep procedural sedation, managed by an anesthesiologist. Once an adequate level of sedation is achieved, the manipulations are performed. Both high- and low-velocity thrusts are used, but it is recommended that the force exerted should be much less, and the manipulations performed with more caution, than in patients who are not anesthetized.12

For the thoracic spine, the patient is manipulated in the supine position with the arms crossed over the chest. The practitioner places one hand in a fist under the spine with the other hand on the patient's crossed arms, then delivers an anterior-to-posterior thrust. This is repeated until all affected segments have been treated.11,12

Literature to support the use of MUA for various indications is largely anecdotal. The largest published series13 is of 177 patients with chronic spinal pain who each underwent three MUA sessions followed by four to six weeks of traditional manipulations. The authors found that pain, as measured by visual analog scale, was reduced by 62% in patients with cervical spine pain, and by 60% in patients with lumbar pain. No adverse events were reported in the study.

Kohlbeck and Haldeman12 reviewed the reported complications of MUA across all published literature. They found that in 17 published papers, the overall complication rate was 0.7%, mainly represented by transitory increased pain. No spinal fractures were reported.

This case demonstrates a rare but serious complication of chiropractic MUA. It is unclear exactly what mechanism of injury led to an unstable thoracic spine fracture with massive hemothorax, and the precise cause will probably never be known. The clinicians who treated the case patient find it curious that the reported rate of adverse events following this procedure is so low, but they suspect an element of reporting bias in the chiropractic literature.

Conclusion

Iatrogenic injury after chiropractic manipulation is uncommon, but it can be devastating. Few serious complications of chiropractic MUA have been reported, but the literature is lacking in well-designed research studies. Despite the dearth of clinical trials to support its safety and efficacy, use of MUA has continued in the chiropractic community. This case demonstrates that serious adverse outcomes can occur, and more rigorous studies are needed to delineate the true benefits and risks of this set of chiropractic procedures.

References

1. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;12:1-9.

2. Davis MA, Sirovich BE, Weeks WB. Utilization and expenditures on chiropractic care in the United States from 1997 to 2006. Health Serv Res. 2009;45:748-761.

3. Canadian Chiropractic Association; Canadian Federation of Chiropractic Regulatory Boards; Clinical Practice Guidelines Development Initiative; Guidelines Development Committee. Chiropractic clinical practice guideline: evidence-based treatment of adult neck pain not due to whiplash. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2005;49:417-421.

4.

Hurwitz EL, Aker PD, Adams AH, et al. Manipulation and mobilization of the cervical spine: a systematic review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:1746-1760.

5.Gouveia LO, Castanho P, Ferreira JJ. Safety of chiropractic interventions: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:E405-E413.

6. Di Fabio RP. Manipulation of the cervical spine: risks and benefits. Phys Ther. 1999;79:50-65.

7. Nadareishvili Z, Norris JW. Stroke from traumatic arterial dissection. Lancet. 1999;354:159-160.

8. Austin RT. Pathological vertebral fractures after spinal manipulation. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291:1114-1115.

9. Ea HK, Weber AJ, Yon F, Lioté F. Osteoporotic fracture of the dens revealed by cervical manipulation. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:246-250.

10. Schmitz A, Lutterbey G, von Engelhardt L, et al. Pathological cervical fracture after spinal manipulation in a pregnant patient. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:633-636.

11. Cremata E, Collins S, Clauson W, et al. Manipulation under anesthesia: a report of four cases. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:526-533.

12. Kohlbeck FJ, Haldeman S. Medication-assisted spinal manipulation. Spine J. 2002;2:288-302.

13. West DT, Mathews RS, Miller MR, Kent GM. Effective management of spinal pain in one hundred seventy-seven patients evaluated for manipulation under anesthesia. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22:299-308.

14. Morey LW Jr. Osteopathic manipulation under general anesthesia. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1973;73:116-127.

15. Tain L, Gunderson C, Cremata E, et al; Committee for Manipulation Under Anesthesia. Recommendations to the Industrial Medical Council Work Group of California for manipulation under anesthesia use for injured workers. Sacramento, CA: Industrial Medical Council; 2003.

A 57-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a two-day history of worsening shortness of breath, light-headedness, and back pain. The patient, who had a history of ankylosing spondylitis, had been receiving weekly therapy from a chiropractor for about 10 years. One week before presenting to the ED, he had begun to undergo daily manipulations under anesthesia (MUA)—an aggressive chiropractic procedure that is administered while the patient is under monitored, procedural sedation. After the second day of treatment, the patient began to experience worsening back pain and progressive light-headedness and shortness of breath.

At a follow-up visit with his chiropractor, he was found to have decreased O2 saturation and was directed to go to the hospital for evaluation. On arrival at the ED, the patient was awake and alert. He had intact motor strength in all extremities, no sensory abnormalities, intact symmetric reflexes, and no bladder or bowel dysfunction, with a negative Babinski sign. His O2 saturation was 92% on 5 L of oxygen. An absence of breath sounds was noted on the left side.

Chest x-ray (see Figure 1) was performed, which demonstrated complete opacification of the left hemithorax, consistent with a large pleural effusion or hemothorax. CT scan of the thoracic spine showed diffuse ankylosis. A complex oblique coronal and transversely oriented fracture with 7 mm of displacement was identified, beginning at the right anterior inferior lateral margin of the T8 vertebral body and extending centrally and inferiorly to the left and right into the T9 vertebral body. The fracture continued through the right T9-10 neural foramen and what was probably the right fused T9-10 facet joint. The fracture exited through the left superior and lateral margin of the T10 vertebral body and the left T10-11 neural foramen (see Figures 2, 3, and 4).

A chest tube was inserted in the ED, and 1,600 mL of old blood was immediately drained. The patient was admitted to the ICU on the trauma service. He was taken to surgery for open reduction and internal fixation of his unstable thoracic spine fracture on day 3 of hospitalization, after his pulmonary condition stabilized. Pedicle screws were placed from T7 through T12 during the spinal fusion. Good reduction of the fracture was observed following the spine surgery (see Figures 5 and 6). At the conclusion of surgery, an epidural catheter was placed in the thoracic spine to administer pain control.

After the spine portion of the procedure, the patient was repositioned and underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery of the left hemithorax for evacuation of retained hemothorax. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was taken to the ICU for recovery.

On postoperative day 2, the patient complained of chest pain and experienced hypoxemia with activity. CT angiography of the chest demonstrated bilateral segmental and subsegmental pulmonary emboli. The epidural catheter was discontinued. Six hours later, a heparin drip was started, and the patient was transitioned to therapeutic enoxaparin and warfarin. When methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) was detected in his hemothorax fluid, he was treated with a course of nafcillin.

The patient was discharged to home on postoperative day 12. He has remained neurologically intact and has returned to his former work activities. He is not taking narcotic pain medications.

Discussion

Chiropractic care is a popular alternative health care modality in the United States. Researchers for the 2007 National Health Interview Study1 reported an annual use of chiropractic manipulation of 8.6%, while the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey2 data yielded an estimate of 12.6 million adults using chiropractic manipulation in 2006—translating to a prevalence of 5.6%. Despite the popularity of chiropractic medicine, few well-designed studies have been conducted to support its use.3,4 Because of its designation as an alternative therapy, however, chiropractic manipulation has not been subjected to rigorous efficacy and safety evaluations.5

Given the inconsistency of the evidence to support chiropractic manipulation, the practice's safety profile is a concern. The risks associated with spinal manipulation are generally described in case reports and small series. Most serious adverse events described in the literature are cerebrovascular in nature and tend to occur after cervical manipulation.6,7 Fractures after spine manipulation are exceedingly rare, and published literature on this topic consists of a few isolated case reports, with all fractures occurring in the cervical spine in patients with an underlying pathologic condition.8-10

In 2009, Gouveia et al5 reviewed the published literature regarding all adverse events resulting from chiropractic manipulation. The authors found one randomized controlled trial, two case-control studies, six prospective studies, 12 surveys, three retrospective studies, and 100 case reports. The spectrum of complications identified ranged from benign and transient, such as local discomfort, to far more serious: stroke, myelopathy, radiculopathy, subdural hematoma, spinal fluid leakage, cauda equina syndrome, herniated disc, diaphragmatic palsy, and vertebral fractures. The authors were unable to perform a true meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity of the data, but they concluded that complications associated with chiropractic procedures are "frequent."5

Manipulations Under Anesthesia

MUA is a procedure that combines chiropractic adjustments and manipulations with general anesthesia or procedural sedation.11 The theory behind this strategy is that the anesthesia or sedation reduces pain and muscle spasm that may hinder the manipulation, allowing the practitioner to more effectively break up joint adhesions and reduce segmental dysfunction than if the patient had not undergone anesthesia.11

MUA is generally indicated in patients who have not responded to a 4- to 8-week trial of traditional manipulation therapy.12 It is also considered in patients who have "painful and restricting muscular guarding [that] interferes with the performance of spinal adjustments, mobilizations, and soft tissue release techniques."13

In the chiropractic literature, between 3% and 10% of patients are estimated to be candidates for MUA.12,14 It is not completely clear, however, what diagnoses are most likely to be treated successfully with this technique. Contraindications to MUA are generally the same as those for manipulation in conscious patients. A published list of contraindications from the Committee for Manipulation under Anesthesia (2003)15 included malignancy with bony metastasis, tuberculosis of the bone, recent fracture, acute arthritis, acute gout, diabetic neuropathy, syphilitic articular lesions, excessive spinal osteoporosis, disk fragmentation, direct nerve root impingement, and evidence of cord or caudal compression by tumor, ankylosis, or other space-occupying lesions.

MUA generally begins with deep procedural sedation, managed by an anesthesiologist. Once an adequate level of sedation is achieved, the manipulations are performed. Both high- and low-velocity thrusts are used, but it is recommended that the force exerted should be much less, and the manipulations performed with more caution, than in patients who are not anesthetized.12

For the thoracic spine, the patient is manipulated in the supine position with the arms crossed over the chest. The practitioner places one hand in a fist under the spine with the other hand on the patient's crossed arms, then delivers an anterior-to-posterior thrust. This is repeated until all affected segments have been treated.11,12

Literature to support the use of MUA for various indications is largely anecdotal. The largest published series13 is of 177 patients with chronic spinal pain who each underwent three MUA sessions followed by four to six weeks of traditional manipulations. The authors found that pain, as measured by visual analog scale, was reduced by 62% in patients with cervical spine pain, and by 60% in patients with lumbar pain. No adverse events were reported in the study.

Kohlbeck and Haldeman12 reviewed the reported complications of MUA across all published literature. They found that in 17 published papers, the overall complication rate was 0.7%, mainly represented by transitory increased pain. No spinal fractures were reported.

This case demonstrates a rare but serious complication of chiropractic MUA. It is unclear exactly what mechanism of injury led to an unstable thoracic spine fracture with massive hemothorax, and the precise cause will probably never be known. The clinicians who treated the case patient find it curious that the reported rate of adverse events following this procedure is so low, but they suspect an element of reporting bias in the chiropractic literature.

Conclusion

Iatrogenic injury after chiropractic manipulation is uncommon, but it can be devastating. Few serious complications of chiropractic MUA have been reported, but the literature is lacking in well-designed research studies. Despite the dearth of clinical trials to support its safety and efficacy, use of MUA has continued in the chiropractic community. This case demonstrates that serious adverse outcomes can occur, and more rigorous studies are needed to delineate the true benefits and risks of this set of chiropractic procedures.

References

1. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;12:1-9.

2. Davis MA, Sirovich BE, Weeks WB. Utilization and expenditures on chiropractic care in the United States from 1997 to 2006. Health Serv Res. 2009;45:748-761.

3. Canadian Chiropractic Association; Canadian Federation of Chiropractic Regulatory Boards; Clinical Practice Guidelines Development Initiative; Guidelines Development Committee. Chiropractic clinical practice guideline: evidence-based treatment of adult neck pain not due to whiplash. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2005;49:417-421.

4.

Hurwitz EL, Aker PD, Adams AH, et al. Manipulation and mobilization of the cervical spine: a systematic review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:1746-1760.

5.Gouveia LO, Castanho P, Ferreira JJ. Safety of chiropractic interventions: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:E405-E413.

6. Di Fabio RP. Manipulation of the cervical spine: risks and benefits. Phys Ther. 1999;79:50-65.

7. Nadareishvili Z, Norris JW. Stroke from traumatic arterial dissection. Lancet. 1999;354:159-160.

8. Austin RT. Pathological vertebral fractures after spinal manipulation. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291:1114-1115.

9. Ea HK, Weber AJ, Yon F, Lioté F. Osteoporotic fracture of the dens revealed by cervical manipulation. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:246-250.

10. Schmitz A, Lutterbey G, von Engelhardt L, et al. Pathological cervical fracture after spinal manipulation in a pregnant patient. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:633-636.

11. Cremata E, Collins S, Clauson W, et al. Manipulation under anesthesia: a report of four cases. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:526-533.

12. Kohlbeck FJ, Haldeman S. Medication-assisted spinal manipulation. Spine J. 2002;2:288-302.

13. West DT, Mathews RS, Miller MR, Kent GM. Effective management of spinal pain in one hundred seventy-seven patients evaluated for manipulation under anesthesia. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22:299-308.

14. Morey LW Jr. Osteopathic manipulation under general anesthesia. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1973;73:116-127.

15. Tain L, Gunderson C, Cremata E, et al; Committee for Manipulation Under Anesthesia. Recommendations to the Industrial Medical Council Work Group of California for manipulation under anesthesia use for injured workers. Sacramento, CA: Industrial Medical Council; 2003.