User login

Comprehensive assessment of cancer survivors’ concerns to inform program development

Complex cancer treatments, limited personnel resources, and a growing number of cancer survivors are challenging cancer health care professionals’ abilities to provide comprehensive care. Cancer survivors have a range of needs that extend over the cancer care trajectory and that represent physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. Numerous studies have explored supportive care needs and recent systematic reviews have highlighted the supportive care needs related to cancer1 and to specific cancer types, including prostate cancer,2 breast cancer,3 gynecologic cancer,4 hematological cancer,5 and lung cancer.6 However, reviews are limited in that they do not always assess needs across the cancer trajectory or identify demographic or clinical variables that are associated with needs. These data are needed to focus survivorship program development in cancer centers in order to target populations most likely at risk for unmet needs, identify what salient concerns to address, and to appropriately schedule supportive care programs.

The importance of assessing the patient’s subjective view of his/her needs or concerns is well acknowledged as being fundamental to patient-centered care.7 Clinicians routinely assess needs in practice using a variety of screening tools. However, there needs to be a broader assessment of concerns and needs in a population of survivors with mixed cancer diagnoses, along with their appraisal of how well their needs were addressed by their health care team, to provide an overall identification of gaps in supportive care. The primary purpose of the present study was to prioritize survivors’ most salient physical, social, emotional, and spiritual concerns or needs; ascertain survivors’ perceived importance of those needs and the extent to which our institution, the University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, was attentive to those needs; and to identify who might be at risk for having greater concerns. The overall goal was to use the data to inform survivorship and supportive care program development.

Methods

Design, sample and setting

We used a cross-sectional design. Surveys were mailed once to a convenience sample of 2,750 adult patients who had been seen in follow-up during the previous 2 years (2010-2011) at all clinical sites of University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, a Midwestern National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. Patients who had a noncancer diagnosis were excluded. The distribution list was screened for deceased individuals and those patients who had multiple visits during the time period. The project was reviewed and approved as nonresearch by the Case Western Reserve University Cancer Institutional Review Board.

Survey

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, administrators, and researchers adapted the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center’s Cancer Survivors Survey of Needs8 to create a comprehensive survey for the cancer center. Input regarding the scope of the survey was sought from the Patient and Family Advisory Council of the cancer center. The survey, which was formatted for scanning purposes, consisted of 33 questions that were compiled into 4 sections. Sections 1 and 2 focused on demographic and treatment-related information, including use of community and hospital support services and preferences for follow-up care. In section 3, a quality-of-life framework was used to assess physical, social, emotional, and spiritual needs. Respondents were asked to rate their current level of concern for 19 physical effects, 10 social effects, 10 emotional effects, and 5 spiritual effects on a scale ranging from 0 (no concern) to 5 (extreme concern). In section 4, respondents were asked to indicate the importance of the cancer team addressing their physical, social, emotional, and spiritual needs. This was followed by their rating of the cancer team’s attention to their needs as Poor, Fair, Good, Excellent, or They did not ask about my needs. Respondents were asked about preferences for learning about physical, social, emotional, and spiritual effects. In addition to the 33 questions, there were 6 open-ended questions in which respondents were encouraged to share additional information about their needs, sources of support, and other concerns.

Procedures

Eligible respondents were mailed a cover letter explaining the survey from both the director and president of the cancer center, a survey, and a postage-paid return envelope. The option to respond to the survey by a telephone call to the director of the Office of Cancer Survivorship was offered in the cover letter.

Data analysis

Returned surveys were scanned into a Teleform database, verified, and exported into an SPSS data file. Data quality was checked by running frequency analyses and summarizing variables. Time-since-treatment responses were collapsed into 4 categories: on treatment, up to 2 years posttreatment, 2-5 years posttreatment, and more than 5 years posttreatment. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and medical characteristics of the respondents and to calculate the mean score for each concern for the total sample and then for each category of time since treatment. Because of the large number of respondents with breast cancer, the respondents were stratified into two groups, one of breast cancer the other of nonbreast cancer respondents. Then, the Mann-Whitney test was performed for each concern to examine differences between respondents with and without breast cancer.

To identify the most prevalent concerns, ratings for concerns were recoded into no concern (rated as 0), low concern (1 or 2), and moderate/high concern (3, 4, or 5). Since our interest was in the moderate and high concerns, the responses were dichotomized into moderate/high concerns and all other levels. Logistic regression models were then used to identify associations between a set of survivor characteristics or covariates (age, sex, living status, marital status, employment status, cancer type, and time since treatment) with the 12 most highly rated moderate/high concerns. All the analyses were performed using statistical software SPSS 20 and Stata 13.0

Results

Respondents

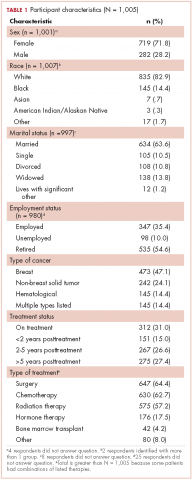

A total of 1,005 surveys were returned for a 37% response rate. Forty-two patients responded by telephone. The mean age of respondents was 64.9 years (range, 22-98; SD, 12.8). The typical respondent was female, white, and married (Table 1). Twenty-four percent of the respondents (n = 240) reported living alone. Although about 47% of respondents (n = 473) reported a breast cancer diagnosis, more than 17 cancers were identified, and 14% of respondents (n = 145) listed multiple diagnoses. About a third of respondents were receiving treatment when they completed the survey.

Just under half of the respondents (n = 498) reported using community resources for support and information about cancer, and 29.5% (n = 296) sought information on the internet during their cancer experience. The most commonly used community resources were The Gathering Place, a local organization offering free supportive programs and services to individuals with cancer and their families (n = 167), and the American Cancer Society (n = 138). Of the 496 respondents who reported accessing hospital resources, most (n = 322) said they used information that their health care team recommended. Other supportive options were used to a lesser degree: support groups (n = 92), chemotherapy and radiation therapy classes (n = 129), and supportive/educational programs offered by the cancer center (n = 27). Most of the respondents (n = 822, 88.6%) preferred to have their follow-up care remain with their cancer care team 1 year after treatments are completed. Almost two-thirds of respondents (n = 601, 64%) cited being seen at the cancer center for follow-up care as the most important factor in considering follow-up care.

Concerns In determining whether the large proportion of respondents with breast cancer skewed the study results, it was determined that median scores differed significantly in only four concerns. Compared with respondents without breast cancer, respondents with breast cancer were more likely to have significantly lower scores for concerns related to fatigue (P <.001) and sexual issues/intimacy (P = .001). Respondents with breast cancer were more likely to have significantly higher scores than respondents without breast cancer for concerns related to genetic counseling (P = .001) and fear of developing a new cancer (P = .010).

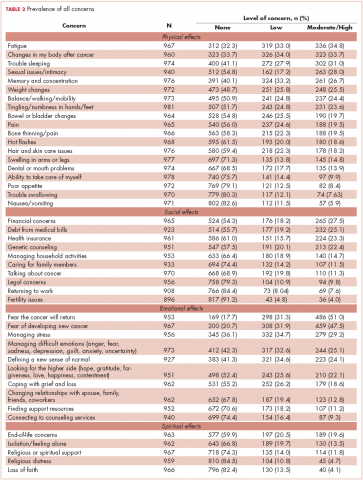

Fears of the cancer returning and developing a new cancer were the two most prevalent concerns, identified by 51% (n = 486) and 47.5% (n = 459), respectively (Table 2). Physical concerns, rated as moderate/high concerns by at least 25% of the sample, were fatigue (n = 336, 34.8%), changes in [the] body after cancer (n = 323, 33.7%), trouble sleeping (n = 302, 31.0%), sexual issues/intimacy (n = 263, 28.0%), memory and concentration (n = 261, 26.7%), and weight changes (n = 248, 25.5%). The most prevalent moderate/high social concerns were related to finances (n = 265, 27.5%) and debt from medical bills (n = 232, 25.1%). Managing stress (n = 279, 29.2%) and difficult emotions (n = 244, 25.1%) were prevalent moderate/high emotional concerns. Spiritual concerns were less often rated as moderate/high concerns. Having a breast cancer diagnosis was not significantly related to the number of reported moderate to high concerns (P = 1.00).

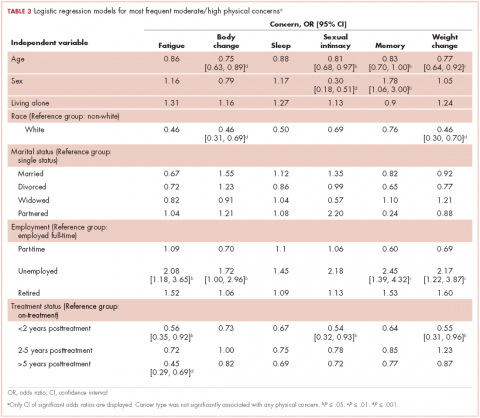

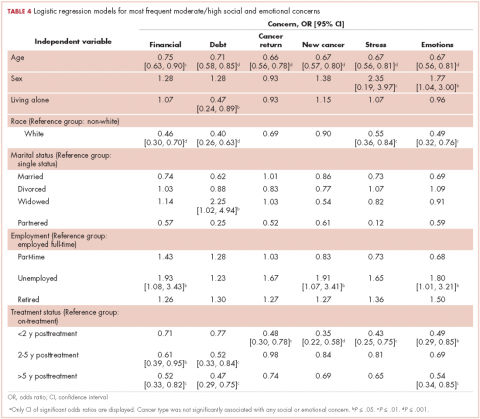

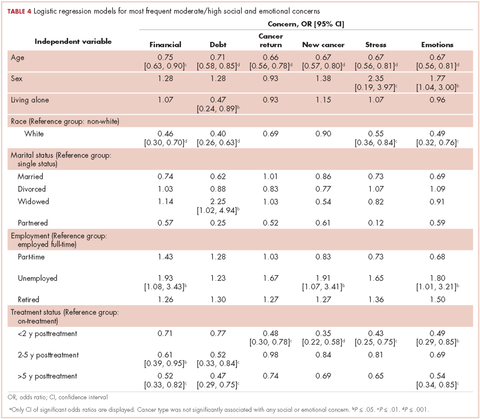

Variables associated with the 12 most frequent moderate/high concerns are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Age was associated with the most moderate/high concerns. With every decade of age, the odds of having the following moderate/high concerns decreased: bodily changes after cancer (odds ratio [OR], 0.75), sexual intimacy (OR, 0.81), memory and concentration (OR, 0.83), weight changes (OR, 0.77), financial (OR, 0.75), debt (OR, 0.71), cancer returning (OR, 0.66), developing a new cancer (OR, 0.67), managing stress (OR, 0.67), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.67).

Female sex was associated with lower odds of having a concern about sexual intimacy (OR, 0.30) and increased odds of having concerns related to memory and concentration (OR, 1.78), managing stress (OR, 2.35), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 1.77). Race was another demographic characteristic statistically associated with numerous moderate/high concerns. Survivors who identified white, were more likely than other people of other races to have fewer moderate/high concerns regarding bodily changes after cancer (OR, 0.46), weight change (OR, 0.46), finances (OR, 0.46), debt (OR, 0.40), managing stress (OR, 0.55), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.49). The odds of having a moderate/high concern regarding debt was 2.25 times higher given widowed marital status compared with those survivors who were single. Unemployment status, when compared with full-time employment, was significantly associated with increased odds of having moderate/high concerns related to fatigue (OR, 2.08), bodily changes after cancer (OR, 1.72), memory and concentration (OR, 2.45), weight changes (OR, 2.17), finances (OR, 1.93), developing a new cancer (OR, 1.91), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 1.80).

As expected, respondents who had completed treatment were less likely to have many of the moderate/high concerns as those still undergoing treatment. Survivors who were up to 2 years posttreatment were significantly more likely than those survivors receiving treatment to have fewer moderate/high concerns regarding fatigue (OR, 0.56), sexual intimacy (OR, 0.54), weight change (OR, 0.55), fears of the cancer returning (OR, 0.48), developing a new cancer (OR, 0.35), managing stress (OR, 0.43), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.49).

However, those improved odds were not sustained over the cancer trajectory. Compared with survivors who were receiving treatment, survivors who were between 2-5 years posttreatment did not have significantly reduced odds for moderate/high concerns related to fatigue, sleep, sexual intimacy, body changes, weight changes, memory, fears of the cancer returning, developing a new cancer, managing stress, and managing difficult emotions. They did have significantly reduced odds for having concerns only related to finances (OR, 0.61) and debt (OR, 0.52).

Long-term survivors, who were beyond 5 years posttreatment, had significantly reduced odds for having moderate/high concerns related to fatigue (OR, 0.45), finances (OR, 0.52), debt (OR, 0.47), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.54), compared with survivors receiving treatment. Moderate/high concerns related to sleep, sexual intimacy, body changes, weight changes, memory, fears of the cancer returning, developing a new cancer, managing stress did not have improved odds for these long-term survivors.

Attention to needs

The health care teams were rated highly for their attention to the patients’ physical needs. Most respondents (n = 845, 92.4%) viewed the health care team’s attention their physical needs as important and 763 (77.6%) survivors rated the team’s attention to these needs as excellent. The importance of addressing emotional needs was affirmed by 723 (78.5%) respondents, and although 454 (46.8%) viewed the team’s attention to these needs as excellent, 119 (12.3%) reported that the health care team did not ask about emotional needs. In addition, 566 respondents (60%) viewed having the health care team address their social needs as important, and most (n = 715, 74.2%) rated the team’s attention to social needs as good or excellent. Yet, 162 (16.8%) respondents reported that team did not ask about their social needs. The health care team’s addressing of spiritual needs was viewed as important by 346 (37.5%) respondents and ratings for how well the team attended to spiritual needs were: 148 (15.6%) poor or fair, 204 (21.5%) good, and 150 (15.8%) excellent. However, 448 (47.2%) respondents reported that the health care team did not ask about their spiritual needs.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this project was to prioritize survivors’ most salient physical, social, emotional, and spiritual concerns or needs and to assess the perceived importance of these needs and the extent to which the cancer center staff were attentive to those needs. The overall goal of this assessment was to inform the development of survivorship and supportive care programs by highlighting common concerns, demographic and medical factors associated with specific concerns, and timing of moderate/high level concerns along the cancer trajectory. There were 3 main findings.

First, the results support the need for enhancing supportive care services to meet emotional concerns of survivors beyond the treatment phase. Similar to other studies,8,9 emotional concerns ranked higher than all other concerns in this study with about 50% of the sample rating “fear the cancer will return” and “fear of developing a new cancer” as moderate/high concern. Although the odds of not having these emotional concerns improved up to 2 years posttreatment, these concerns are likely to resurface, as odds for survivors beyond 2 years were not significantly different from those receiving treatment. A recent systematic review reported that fear of cancer recurrence is experienced by about 73% of cancer survivors, with 49% reporting a moderate to high degree.10 It can have a chronic, stable trajectory for some survivors and is strongly associated with higher levels of anxiety, distress, and depression, and less global, emotional/mental, physical, role, social, and cognitive quality of life.10 In this sample, managing stress and difficult emotions were also rated as moderate/high concerns by at least 25% of the sample.

Second, the findings identified patients at risk for cancer-related concerns throughout the cancer trajectory. As demonstrated in other studies, younger age was associated with greater odds of having multiple greater moderate/high concerns.11-13 Unemployment was the second most common demographic factor associated with multiple moderate/high concerns related to physical symptoms, finances and emotions. Similarly, identifying as black, Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, or other was also associated with greater odds of having numerous physical, financial, and emotional concerns. Women had greater concerns related to memory, sexual intimacy, coping with difficult emotions, and stress.

Third, the results helped to identify gaps in supportive care at our cancer center. Although spiritual concerns were not prevalent as being moderate/high, they were still viewed by about a third of survivors as being an important area for the health care team to address. Yet, consistent with other need assessments, spiritual concerns in this study were least often addressed by staff.1 Assessment of spiritual care needs, screening for spiritual distress, and providing spiritual care are essential components of a clinician-patient relationship that supports healing.14 The importance of attending to spiritual care needs was underscored by a recent systematic review that found a positive association between overall spiritual well-being and quality of life in patients with cancer, with the meaning/peace factor consistently and positively associated with physical and mental health.15 Another identified gap was the health care team’s lack of attention to the patient’s social needs, which included concerns related to finances and debt from medical bills. In all, 46% of the respondents reported having financial concerns, with the odds of having moderate/high financial concerns being greatest during treatment to 2 years posttreatment. Attention to the financial burden of cancer patients is critical because the magnitude of cancer-related financial concerns is a significant, strong predictor of quality of life and adverse psychological issues such as depression, anxiety, and distress.16,17

There were several program implications based on the results. A periodic audit of the concerns of survivors and their views on how well their needs were being met was a relatively low cost endeavor. Although the findings were consistent with the literature, the results, when shared with administrators and clinicians, were instrumental in effecting change because they represented the concerns of survivors at the cancer center. Another program directive, based on the results, was to extend the routine screening of patients’ needs during treatment to posttreatment survivorship. Patients who are young, unemployed, do not identify as white, and female warrant more thorough assessment of needs and concerns along the cancer trajectory. Integral to these screenings is the need for patient-centered communication, with discussion of how cancer is affecting the different domains of quality of life within the context of the patient’s life. Lastly, the results clearly indicated the need for additional training of health care providers on how to assess and address spiritual well-being in cancer survivors.

There were limitations to this study, including use of a nonvalidated survey and cross-sectional approach that limited our ability to explore how concerns might change over the trajectory. Also, it was not possible to clarify medical information of the respondents, such as cancer stage. Although the response rate of this study was not high, we are confident in the results because of the large sample size and the finding that the large proportion of respondents with breast cancer was not influential. Despite these limitations, this needs assessment of cancer survivors over the trajectory of care provided insight into the scope of their concerns, identified vulnerable groups of survivors, and highlighted gaps in addressing those concerns. A quality- of-life framework for assessing needs assured a comprehensive focus and generated practice changes to strengthen holistic, comprehensive oncology care.

1. Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1117-1128.

2. Paterson C, Robertson A, Smith A, Nabi G. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: A systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:405-418.

3. Fiszer C, Dolbeault S, Sultan S, Bredart A. Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23:361-374.

4. Maguire R, Kotronoulas G, Simpson M, Paterson C. A systematic review of the supportive care needs of women living with and beyond cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:478-490.

5. Hall A, Lynagh M, Bryant J, Sanson-Fisher R. Supportive care needs of hematological cancer survivors: A critical review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:102-116.

6. Maguire R, Papadopoulou C, Kotronoulas G, Simpson MF, McPhelim J, Irvine L. A systematic review of supportive care needs of people living with lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:449-464.

7. Adler NE, Page EK. Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Institute of Medicine, 2008.

8. Ness S, Kokal J, Fee-Schroeder K, Novotny P, Satele D, Barton D. Concerns across the survivorship trajectory: results from a survey of cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:35-42.

9. Swash B, Hulbert-Williams N, Bramwell R. Unmet psychosocial needs in haematological cancer: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1131-1141.

10. Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: A systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:300-322.

11. Choi KH, Park JH, Park JH, Park JS. Psychosocial needs of cancer patients and related factors: A multi-center, cross-sectional study in Korea. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1073-1080.

12. Pauwels EE, Charlier C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lechner L, Van Hoof E. Care needs after primary breast cancer treatment. Survivors’ associated sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Psychooncology. 2013;22:125-132.

13. Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1117-1128.

14. Puchalski CM, Blatt B, Kogan M, Butler A. Spirituality and health: The development of a field. Academic Medicine. 2014;89:10-16.

15. Bai M, Lazenby M. A systematic review of associations between spiritual well-being and quality of life at the scale and factor levels in studies among patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:286-298.

16. Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:332-338.

17. Sharp L, Carsin AE, Timmons A. Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological wellbeing among individuals living with cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:745-755.

Complex cancer treatments, limited personnel resources, and a growing number of cancer survivors are challenging cancer health care professionals’ abilities to provide comprehensive care. Cancer survivors have a range of needs that extend over the cancer care trajectory and that represent physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. Numerous studies have explored supportive care needs and recent systematic reviews have highlighted the supportive care needs related to cancer1 and to specific cancer types, including prostate cancer,2 breast cancer,3 gynecologic cancer,4 hematological cancer,5 and lung cancer.6 However, reviews are limited in that they do not always assess needs across the cancer trajectory or identify demographic or clinical variables that are associated with needs. These data are needed to focus survivorship program development in cancer centers in order to target populations most likely at risk for unmet needs, identify what salient concerns to address, and to appropriately schedule supportive care programs.

The importance of assessing the patient’s subjective view of his/her needs or concerns is well acknowledged as being fundamental to patient-centered care.7 Clinicians routinely assess needs in practice using a variety of screening tools. However, there needs to be a broader assessment of concerns and needs in a population of survivors with mixed cancer diagnoses, along with their appraisal of how well their needs were addressed by their health care team, to provide an overall identification of gaps in supportive care. The primary purpose of the present study was to prioritize survivors’ most salient physical, social, emotional, and spiritual concerns or needs; ascertain survivors’ perceived importance of those needs and the extent to which our institution, the University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, was attentive to those needs; and to identify who might be at risk for having greater concerns. The overall goal was to use the data to inform survivorship and supportive care program development.

Methods

Design, sample and setting

We used a cross-sectional design. Surveys were mailed once to a convenience sample of 2,750 adult patients who had been seen in follow-up during the previous 2 years (2010-2011) at all clinical sites of University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, a Midwestern National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. Patients who had a noncancer diagnosis were excluded. The distribution list was screened for deceased individuals and those patients who had multiple visits during the time period. The project was reviewed and approved as nonresearch by the Case Western Reserve University Cancer Institutional Review Board.

Survey

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, administrators, and researchers adapted the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center’s Cancer Survivors Survey of Needs8 to create a comprehensive survey for the cancer center. Input regarding the scope of the survey was sought from the Patient and Family Advisory Council of the cancer center. The survey, which was formatted for scanning purposes, consisted of 33 questions that were compiled into 4 sections. Sections 1 and 2 focused on demographic and treatment-related information, including use of community and hospital support services and preferences for follow-up care. In section 3, a quality-of-life framework was used to assess physical, social, emotional, and spiritual needs. Respondents were asked to rate their current level of concern for 19 physical effects, 10 social effects, 10 emotional effects, and 5 spiritual effects on a scale ranging from 0 (no concern) to 5 (extreme concern). In section 4, respondents were asked to indicate the importance of the cancer team addressing their physical, social, emotional, and spiritual needs. This was followed by their rating of the cancer team’s attention to their needs as Poor, Fair, Good, Excellent, or They did not ask about my needs. Respondents were asked about preferences for learning about physical, social, emotional, and spiritual effects. In addition to the 33 questions, there were 6 open-ended questions in which respondents were encouraged to share additional information about their needs, sources of support, and other concerns.

Procedures

Eligible respondents were mailed a cover letter explaining the survey from both the director and president of the cancer center, a survey, and a postage-paid return envelope. The option to respond to the survey by a telephone call to the director of the Office of Cancer Survivorship was offered in the cover letter.

Data analysis

Returned surveys were scanned into a Teleform database, verified, and exported into an SPSS data file. Data quality was checked by running frequency analyses and summarizing variables. Time-since-treatment responses were collapsed into 4 categories: on treatment, up to 2 years posttreatment, 2-5 years posttreatment, and more than 5 years posttreatment. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and medical characteristics of the respondents and to calculate the mean score for each concern for the total sample and then for each category of time since treatment. Because of the large number of respondents with breast cancer, the respondents were stratified into two groups, one of breast cancer the other of nonbreast cancer respondents. Then, the Mann-Whitney test was performed for each concern to examine differences between respondents with and without breast cancer.

To identify the most prevalent concerns, ratings for concerns were recoded into no concern (rated as 0), low concern (1 or 2), and moderate/high concern (3, 4, or 5). Since our interest was in the moderate and high concerns, the responses were dichotomized into moderate/high concerns and all other levels. Logistic regression models were then used to identify associations between a set of survivor characteristics or covariates (age, sex, living status, marital status, employment status, cancer type, and time since treatment) with the 12 most highly rated moderate/high concerns. All the analyses were performed using statistical software SPSS 20 and Stata 13.0

Results

Respondents

A total of 1,005 surveys were returned for a 37% response rate. Forty-two patients responded by telephone. The mean age of respondents was 64.9 years (range, 22-98; SD, 12.8). The typical respondent was female, white, and married (Table 1). Twenty-four percent of the respondents (n = 240) reported living alone. Although about 47% of respondents (n = 473) reported a breast cancer diagnosis, more than 17 cancers were identified, and 14% of respondents (n = 145) listed multiple diagnoses. About a third of respondents were receiving treatment when they completed the survey.

Just under half of the respondents (n = 498) reported using community resources for support and information about cancer, and 29.5% (n = 296) sought information on the internet during their cancer experience. The most commonly used community resources were The Gathering Place, a local organization offering free supportive programs and services to individuals with cancer and their families (n = 167), and the American Cancer Society (n = 138). Of the 496 respondents who reported accessing hospital resources, most (n = 322) said they used information that their health care team recommended. Other supportive options were used to a lesser degree: support groups (n = 92), chemotherapy and radiation therapy classes (n = 129), and supportive/educational programs offered by the cancer center (n = 27). Most of the respondents (n = 822, 88.6%) preferred to have their follow-up care remain with their cancer care team 1 year after treatments are completed. Almost two-thirds of respondents (n = 601, 64%) cited being seen at the cancer center for follow-up care as the most important factor in considering follow-up care.

Concerns In determining whether the large proportion of respondents with breast cancer skewed the study results, it was determined that median scores differed significantly in only four concerns. Compared with respondents without breast cancer, respondents with breast cancer were more likely to have significantly lower scores for concerns related to fatigue (P <.001) and sexual issues/intimacy (P = .001). Respondents with breast cancer were more likely to have significantly higher scores than respondents without breast cancer for concerns related to genetic counseling (P = .001) and fear of developing a new cancer (P = .010).

Fears of the cancer returning and developing a new cancer were the two most prevalent concerns, identified by 51% (n = 486) and 47.5% (n = 459), respectively (Table 2). Physical concerns, rated as moderate/high concerns by at least 25% of the sample, were fatigue (n = 336, 34.8%), changes in [the] body after cancer (n = 323, 33.7%), trouble sleeping (n = 302, 31.0%), sexual issues/intimacy (n = 263, 28.0%), memory and concentration (n = 261, 26.7%), and weight changes (n = 248, 25.5%). The most prevalent moderate/high social concerns were related to finances (n = 265, 27.5%) and debt from medical bills (n = 232, 25.1%). Managing stress (n = 279, 29.2%) and difficult emotions (n = 244, 25.1%) were prevalent moderate/high emotional concerns. Spiritual concerns were less often rated as moderate/high concerns. Having a breast cancer diagnosis was not significantly related to the number of reported moderate to high concerns (P = 1.00).

Variables associated with the 12 most frequent moderate/high concerns are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Age was associated with the most moderate/high concerns. With every decade of age, the odds of having the following moderate/high concerns decreased: bodily changes after cancer (odds ratio [OR], 0.75), sexual intimacy (OR, 0.81), memory and concentration (OR, 0.83), weight changes (OR, 0.77), financial (OR, 0.75), debt (OR, 0.71), cancer returning (OR, 0.66), developing a new cancer (OR, 0.67), managing stress (OR, 0.67), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.67).

Female sex was associated with lower odds of having a concern about sexual intimacy (OR, 0.30) and increased odds of having concerns related to memory and concentration (OR, 1.78), managing stress (OR, 2.35), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 1.77). Race was another demographic characteristic statistically associated with numerous moderate/high concerns. Survivors who identified white, were more likely than other people of other races to have fewer moderate/high concerns regarding bodily changes after cancer (OR, 0.46), weight change (OR, 0.46), finances (OR, 0.46), debt (OR, 0.40), managing stress (OR, 0.55), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.49). The odds of having a moderate/high concern regarding debt was 2.25 times higher given widowed marital status compared with those survivors who were single. Unemployment status, when compared with full-time employment, was significantly associated with increased odds of having moderate/high concerns related to fatigue (OR, 2.08), bodily changes after cancer (OR, 1.72), memory and concentration (OR, 2.45), weight changes (OR, 2.17), finances (OR, 1.93), developing a new cancer (OR, 1.91), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 1.80).

As expected, respondents who had completed treatment were less likely to have many of the moderate/high concerns as those still undergoing treatment. Survivors who were up to 2 years posttreatment were significantly more likely than those survivors receiving treatment to have fewer moderate/high concerns regarding fatigue (OR, 0.56), sexual intimacy (OR, 0.54), weight change (OR, 0.55), fears of the cancer returning (OR, 0.48), developing a new cancer (OR, 0.35), managing stress (OR, 0.43), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.49).

However, those improved odds were not sustained over the cancer trajectory. Compared with survivors who were receiving treatment, survivors who were between 2-5 years posttreatment did not have significantly reduced odds for moderate/high concerns related to fatigue, sleep, sexual intimacy, body changes, weight changes, memory, fears of the cancer returning, developing a new cancer, managing stress, and managing difficult emotions. They did have significantly reduced odds for having concerns only related to finances (OR, 0.61) and debt (OR, 0.52).

Long-term survivors, who were beyond 5 years posttreatment, had significantly reduced odds for having moderate/high concerns related to fatigue (OR, 0.45), finances (OR, 0.52), debt (OR, 0.47), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.54), compared with survivors receiving treatment. Moderate/high concerns related to sleep, sexual intimacy, body changes, weight changes, memory, fears of the cancer returning, developing a new cancer, managing stress did not have improved odds for these long-term survivors.

Attention to needs

The health care teams were rated highly for their attention to the patients’ physical needs. Most respondents (n = 845, 92.4%) viewed the health care team’s attention their physical needs as important and 763 (77.6%) survivors rated the team’s attention to these needs as excellent. The importance of addressing emotional needs was affirmed by 723 (78.5%) respondents, and although 454 (46.8%) viewed the team’s attention to these needs as excellent, 119 (12.3%) reported that the health care team did not ask about emotional needs. In addition, 566 respondents (60%) viewed having the health care team address their social needs as important, and most (n = 715, 74.2%) rated the team’s attention to social needs as good or excellent. Yet, 162 (16.8%) respondents reported that team did not ask about their social needs. The health care team’s addressing of spiritual needs was viewed as important by 346 (37.5%) respondents and ratings for how well the team attended to spiritual needs were: 148 (15.6%) poor or fair, 204 (21.5%) good, and 150 (15.8%) excellent. However, 448 (47.2%) respondents reported that the health care team did not ask about their spiritual needs.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this project was to prioritize survivors’ most salient physical, social, emotional, and spiritual concerns or needs and to assess the perceived importance of these needs and the extent to which the cancer center staff were attentive to those needs. The overall goal of this assessment was to inform the development of survivorship and supportive care programs by highlighting common concerns, demographic and medical factors associated with specific concerns, and timing of moderate/high level concerns along the cancer trajectory. There were 3 main findings.

First, the results support the need for enhancing supportive care services to meet emotional concerns of survivors beyond the treatment phase. Similar to other studies,8,9 emotional concerns ranked higher than all other concerns in this study with about 50% of the sample rating “fear the cancer will return” and “fear of developing a new cancer” as moderate/high concern. Although the odds of not having these emotional concerns improved up to 2 years posttreatment, these concerns are likely to resurface, as odds for survivors beyond 2 years were not significantly different from those receiving treatment. A recent systematic review reported that fear of cancer recurrence is experienced by about 73% of cancer survivors, with 49% reporting a moderate to high degree.10 It can have a chronic, stable trajectory for some survivors and is strongly associated with higher levels of anxiety, distress, and depression, and less global, emotional/mental, physical, role, social, and cognitive quality of life.10 In this sample, managing stress and difficult emotions were also rated as moderate/high concerns by at least 25% of the sample.

Second, the findings identified patients at risk for cancer-related concerns throughout the cancer trajectory. As demonstrated in other studies, younger age was associated with greater odds of having multiple greater moderate/high concerns.11-13 Unemployment was the second most common demographic factor associated with multiple moderate/high concerns related to physical symptoms, finances and emotions. Similarly, identifying as black, Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, or other was also associated with greater odds of having numerous physical, financial, and emotional concerns. Women had greater concerns related to memory, sexual intimacy, coping with difficult emotions, and stress.

Third, the results helped to identify gaps in supportive care at our cancer center. Although spiritual concerns were not prevalent as being moderate/high, they were still viewed by about a third of survivors as being an important area for the health care team to address. Yet, consistent with other need assessments, spiritual concerns in this study were least often addressed by staff.1 Assessment of spiritual care needs, screening for spiritual distress, and providing spiritual care are essential components of a clinician-patient relationship that supports healing.14 The importance of attending to spiritual care needs was underscored by a recent systematic review that found a positive association between overall spiritual well-being and quality of life in patients with cancer, with the meaning/peace factor consistently and positively associated with physical and mental health.15 Another identified gap was the health care team’s lack of attention to the patient’s social needs, which included concerns related to finances and debt from medical bills. In all, 46% of the respondents reported having financial concerns, with the odds of having moderate/high financial concerns being greatest during treatment to 2 years posttreatment. Attention to the financial burden of cancer patients is critical because the magnitude of cancer-related financial concerns is a significant, strong predictor of quality of life and adverse psychological issues such as depression, anxiety, and distress.16,17

There were several program implications based on the results. A periodic audit of the concerns of survivors and their views on how well their needs were being met was a relatively low cost endeavor. Although the findings were consistent with the literature, the results, when shared with administrators and clinicians, were instrumental in effecting change because they represented the concerns of survivors at the cancer center. Another program directive, based on the results, was to extend the routine screening of patients’ needs during treatment to posttreatment survivorship. Patients who are young, unemployed, do not identify as white, and female warrant more thorough assessment of needs and concerns along the cancer trajectory. Integral to these screenings is the need for patient-centered communication, with discussion of how cancer is affecting the different domains of quality of life within the context of the patient’s life. Lastly, the results clearly indicated the need for additional training of health care providers on how to assess and address spiritual well-being in cancer survivors.

There were limitations to this study, including use of a nonvalidated survey and cross-sectional approach that limited our ability to explore how concerns might change over the trajectory. Also, it was not possible to clarify medical information of the respondents, such as cancer stage. Although the response rate of this study was not high, we are confident in the results because of the large sample size and the finding that the large proportion of respondents with breast cancer was not influential. Despite these limitations, this needs assessment of cancer survivors over the trajectory of care provided insight into the scope of their concerns, identified vulnerable groups of survivors, and highlighted gaps in addressing those concerns. A quality- of-life framework for assessing needs assured a comprehensive focus and generated practice changes to strengthen holistic, comprehensive oncology care.

Complex cancer treatments, limited personnel resources, and a growing number of cancer survivors are challenging cancer health care professionals’ abilities to provide comprehensive care. Cancer survivors have a range of needs that extend over the cancer care trajectory and that represent physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. Numerous studies have explored supportive care needs and recent systematic reviews have highlighted the supportive care needs related to cancer1 and to specific cancer types, including prostate cancer,2 breast cancer,3 gynecologic cancer,4 hematological cancer,5 and lung cancer.6 However, reviews are limited in that they do not always assess needs across the cancer trajectory or identify demographic or clinical variables that are associated with needs. These data are needed to focus survivorship program development in cancer centers in order to target populations most likely at risk for unmet needs, identify what salient concerns to address, and to appropriately schedule supportive care programs.

The importance of assessing the patient’s subjective view of his/her needs or concerns is well acknowledged as being fundamental to patient-centered care.7 Clinicians routinely assess needs in practice using a variety of screening tools. However, there needs to be a broader assessment of concerns and needs in a population of survivors with mixed cancer diagnoses, along with their appraisal of how well their needs were addressed by their health care team, to provide an overall identification of gaps in supportive care. The primary purpose of the present study was to prioritize survivors’ most salient physical, social, emotional, and spiritual concerns or needs; ascertain survivors’ perceived importance of those needs and the extent to which our institution, the University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, was attentive to those needs; and to identify who might be at risk for having greater concerns. The overall goal was to use the data to inform survivorship and supportive care program development.

Methods

Design, sample and setting

We used a cross-sectional design. Surveys were mailed once to a convenience sample of 2,750 adult patients who had been seen in follow-up during the previous 2 years (2010-2011) at all clinical sites of University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, a Midwestern National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. Patients who had a noncancer diagnosis were excluded. The distribution list was screened for deceased individuals and those patients who had multiple visits during the time period. The project was reviewed and approved as nonresearch by the Case Western Reserve University Cancer Institutional Review Board.

Survey

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, administrators, and researchers adapted the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center’s Cancer Survivors Survey of Needs8 to create a comprehensive survey for the cancer center. Input regarding the scope of the survey was sought from the Patient and Family Advisory Council of the cancer center. The survey, which was formatted for scanning purposes, consisted of 33 questions that were compiled into 4 sections. Sections 1 and 2 focused on demographic and treatment-related information, including use of community and hospital support services and preferences for follow-up care. In section 3, a quality-of-life framework was used to assess physical, social, emotional, and spiritual needs. Respondents were asked to rate their current level of concern for 19 physical effects, 10 social effects, 10 emotional effects, and 5 spiritual effects on a scale ranging from 0 (no concern) to 5 (extreme concern). In section 4, respondents were asked to indicate the importance of the cancer team addressing their physical, social, emotional, and spiritual needs. This was followed by their rating of the cancer team’s attention to their needs as Poor, Fair, Good, Excellent, or They did not ask about my needs. Respondents were asked about preferences for learning about physical, social, emotional, and spiritual effects. In addition to the 33 questions, there were 6 open-ended questions in which respondents were encouraged to share additional information about their needs, sources of support, and other concerns.

Procedures

Eligible respondents were mailed a cover letter explaining the survey from both the director and president of the cancer center, a survey, and a postage-paid return envelope. The option to respond to the survey by a telephone call to the director of the Office of Cancer Survivorship was offered in the cover letter.

Data analysis

Returned surveys were scanned into a Teleform database, verified, and exported into an SPSS data file. Data quality was checked by running frequency analyses and summarizing variables. Time-since-treatment responses were collapsed into 4 categories: on treatment, up to 2 years posttreatment, 2-5 years posttreatment, and more than 5 years posttreatment. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and medical characteristics of the respondents and to calculate the mean score for each concern for the total sample and then for each category of time since treatment. Because of the large number of respondents with breast cancer, the respondents were stratified into two groups, one of breast cancer the other of nonbreast cancer respondents. Then, the Mann-Whitney test was performed for each concern to examine differences between respondents with and without breast cancer.

To identify the most prevalent concerns, ratings for concerns were recoded into no concern (rated as 0), low concern (1 or 2), and moderate/high concern (3, 4, or 5). Since our interest was in the moderate and high concerns, the responses were dichotomized into moderate/high concerns and all other levels. Logistic regression models were then used to identify associations between a set of survivor characteristics or covariates (age, sex, living status, marital status, employment status, cancer type, and time since treatment) with the 12 most highly rated moderate/high concerns. All the analyses were performed using statistical software SPSS 20 and Stata 13.0

Results

Respondents

A total of 1,005 surveys were returned for a 37% response rate. Forty-two patients responded by telephone. The mean age of respondents was 64.9 years (range, 22-98; SD, 12.8). The typical respondent was female, white, and married (Table 1). Twenty-four percent of the respondents (n = 240) reported living alone. Although about 47% of respondents (n = 473) reported a breast cancer diagnosis, more than 17 cancers were identified, and 14% of respondents (n = 145) listed multiple diagnoses. About a third of respondents were receiving treatment when they completed the survey.

Just under half of the respondents (n = 498) reported using community resources for support and information about cancer, and 29.5% (n = 296) sought information on the internet during their cancer experience. The most commonly used community resources were The Gathering Place, a local organization offering free supportive programs and services to individuals with cancer and their families (n = 167), and the American Cancer Society (n = 138). Of the 496 respondents who reported accessing hospital resources, most (n = 322) said they used information that their health care team recommended. Other supportive options were used to a lesser degree: support groups (n = 92), chemotherapy and radiation therapy classes (n = 129), and supportive/educational programs offered by the cancer center (n = 27). Most of the respondents (n = 822, 88.6%) preferred to have their follow-up care remain with their cancer care team 1 year after treatments are completed. Almost two-thirds of respondents (n = 601, 64%) cited being seen at the cancer center for follow-up care as the most important factor in considering follow-up care.

Concerns In determining whether the large proportion of respondents with breast cancer skewed the study results, it was determined that median scores differed significantly in only four concerns. Compared with respondents without breast cancer, respondents with breast cancer were more likely to have significantly lower scores for concerns related to fatigue (P <.001) and sexual issues/intimacy (P = .001). Respondents with breast cancer were more likely to have significantly higher scores than respondents without breast cancer for concerns related to genetic counseling (P = .001) and fear of developing a new cancer (P = .010).

Fears of the cancer returning and developing a new cancer were the two most prevalent concerns, identified by 51% (n = 486) and 47.5% (n = 459), respectively (Table 2). Physical concerns, rated as moderate/high concerns by at least 25% of the sample, were fatigue (n = 336, 34.8%), changes in [the] body after cancer (n = 323, 33.7%), trouble sleeping (n = 302, 31.0%), sexual issues/intimacy (n = 263, 28.0%), memory and concentration (n = 261, 26.7%), and weight changes (n = 248, 25.5%). The most prevalent moderate/high social concerns were related to finances (n = 265, 27.5%) and debt from medical bills (n = 232, 25.1%). Managing stress (n = 279, 29.2%) and difficult emotions (n = 244, 25.1%) were prevalent moderate/high emotional concerns. Spiritual concerns were less often rated as moderate/high concerns. Having a breast cancer diagnosis was not significantly related to the number of reported moderate to high concerns (P = 1.00).

Variables associated with the 12 most frequent moderate/high concerns are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Age was associated with the most moderate/high concerns. With every decade of age, the odds of having the following moderate/high concerns decreased: bodily changes after cancer (odds ratio [OR], 0.75), sexual intimacy (OR, 0.81), memory and concentration (OR, 0.83), weight changes (OR, 0.77), financial (OR, 0.75), debt (OR, 0.71), cancer returning (OR, 0.66), developing a new cancer (OR, 0.67), managing stress (OR, 0.67), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.67).

Female sex was associated with lower odds of having a concern about sexual intimacy (OR, 0.30) and increased odds of having concerns related to memory and concentration (OR, 1.78), managing stress (OR, 2.35), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 1.77). Race was another demographic characteristic statistically associated with numerous moderate/high concerns. Survivors who identified white, were more likely than other people of other races to have fewer moderate/high concerns regarding bodily changes after cancer (OR, 0.46), weight change (OR, 0.46), finances (OR, 0.46), debt (OR, 0.40), managing stress (OR, 0.55), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.49). The odds of having a moderate/high concern regarding debt was 2.25 times higher given widowed marital status compared with those survivors who were single. Unemployment status, when compared with full-time employment, was significantly associated with increased odds of having moderate/high concerns related to fatigue (OR, 2.08), bodily changes after cancer (OR, 1.72), memory and concentration (OR, 2.45), weight changes (OR, 2.17), finances (OR, 1.93), developing a new cancer (OR, 1.91), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 1.80).

As expected, respondents who had completed treatment were less likely to have many of the moderate/high concerns as those still undergoing treatment. Survivors who were up to 2 years posttreatment were significantly more likely than those survivors receiving treatment to have fewer moderate/high concerns regarding fatigue (OR, 0.56), sexual intimacy (OR, 0.54), weight change (OR, 0.55), fears of the cancer returning (OR, 0.48), developing a new cancer (OR, 0.35), managing stress (OR, 0.43), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.49).

However, those improved odds were not sustained over the cancer trajectory. Compared with survivors who were receiving treatment, survivors who were between 2-5 years posttreatment did not have significantly reduced odds for moderate/high concerns related to fatigue, sleep, sexual intimacy, body changes, weight changes, memory, fears of the cancer returning, developing a new cancer, managing stress, and managing difficult emotions. They did have significantly reduced odds for having concerns only related to finances (OR, 0.61) and debt (OR, 0.52).

Long-term survivors, who were beyond 5 years posttreatment, had significantly reduced odds for having moderate/high concerns related to fatigue (OR, 0.45), finances (OR, 0.52), debt (OR, 0.47), and managing difficult emotions (OR, 0.54), compared with survivors receiving treatment. Moderate/high concerns related to sleep, sexual intimacy, body changes, weight changes, memory, fears of the cancer returning, developing a new cancer, managing stress did not have improved odds for these long-term survivors.

Attention to needs

The health care teams were rated highly for their attention to the patients’ physical needs. Most respondents (n = 845, 92.4%) viewed the health care team’s attention their physical needs as important and 763 (77.6%) survivors rated the team’s attention to these needs as excellent. The importance of addressing emotional needs was affirmed by 723 (78.5%) respondents, and although 454 (46.8%) viewed the team’s attention to these needs as excellent, 119 (12.3%) reported that the health care team did not ask about emotional needs. In addition, 566 respondents (60%) viewed having the health care team address their social needs as important, and most (n = 715, 74.2%) rated the team’s attention to social needs as good or excellent. Yet, 162 (16.8%) respondents reported that team did not ask about their social needs. The health care team’s addressing of spiritual needs was viewed as important by 346 (37.5%) respondents and ratings for how well the team attended to spiritual needs were: 148 (15.6%) poor or fair, 204 (21.5%) good, and 150 (15.8%) excellent. However, 448 (47.2%) respondents reported that the health care team did not ask about their spiritual needs.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this project was to prioritize survivors’ most salient physical, social, emotional, and spiritual concerns or needs and to assess the perceived importance of these needs and the extent to which the cancer center staff were attentive to those needs. The overall goal of this assessment was to inform the development of survivorship and supportive care programs by highlighting common concerns, demographic and medical factors associated with specific concerns, and timing of moderate/high level concerns along the cancer trajectory. There were 3 main findings.

First, the results support the need for enhancing supportive care services to meet emotional concerns of survivors beyond the treatment phase. Similar to other studies,8,9 emotional concerns ranked higher than all other concerns in this study with about 50% of the sample rating “fear the cancer will return” and “fear of developing a new cancer” as moderate/high concern. Although the odds of not having these emotional concerns improved up to 2 years posttreatment, these concerns are likely to resurface, as odds for survivors beyond 2 years were not significantly different from those receiving treatment. A recent systematic review reported that fear of cancer recurrence is experienced by about 73% of cancer survivors, with 49% reporting a moderate to high degree.10 It can have a chronic, stable trajectory for some survivors and is strongly associated with higher levels of anxiety, distress, and depression, and less global, emotional/mental, physical, role, social, and cognitive quality of life.10 In this sample, managing stress and difficult emotions were also rated as moderate/high concerns by at least 25% of the sample.

Second, the findings identified patients at risk for cancer-related concerns throughout the cancer trajectory. As demonstrated in other studies, younger age was associated with greater odds of having multiple greater moderate/high concerns.11-13 Unemployment was the second most common demographic factor associated with multiple moderate/high concerns related to physical symptoms, finances and emotions. Similarly, identifying as black, Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, or other was also associated with greater odds of having numerous physical, financial, and emotional concerns. Women had greater concerns related to memory, sexual intimacy, coping with difficult emotions, and stress.

Third, the results helped to identify gaps in supportive care at our cancer center. Although spiritual concerns were not prevalent as being moderate/high, they were still viewed by about a third of survivors as being an important area for the health care team to address. Yet, consistent with other need assessments, spiritual concerns in this study were least often addressed by staff.1 Assessment of spiritual care needs, screening for spiritual distress, and providing spiritual care are essential components of a clinician-patient relationship that supports healing.14 The importance of attending to spiritual care needs was underscored by a recent systematic review that found a positive association between overall spiritual well-being and quality of life in patients with cancer, with the meaning/peace factor consistently and positively associated with physical and mental health.15 Another identified gap was the health care team’s lack of attention to the patient’s social needs, which included concerns related to finances and debt from medical bills. In all, 46% of the respondents reported having financial concerns, with the odds of having moderate/high financial concerns being greatest during treatment to 2 years posttreatment. Attention to the financial burden of cancer patients is critical because the magnitude of cancer-related financial concerns is a significant, strong predictor of quality of life and adverse psychological issues such as depression, anxiety, and distress.16,17

There were several program implications based on the results. A periodic audit of the concerns of survivors and their views on how well their needs were being met was a relatively low cost endeavor. Although the findings were consistent with the literature, the results, when shared with administrators and clinicians, were instrumental in effecting change because they represented the concerns of survivors at the cancer center. Another program directive, based on the results, was to extend the routine screening of patients’ needs during treatment to posttreatment survivorship. Patients who are young, unemployed, do not identify as white, and female warrant more thorough assessment of needs and concerns along the cancer trajectory. Integral to these screenings is the need for patient-centered communication, with discussion of how cancer is affecting the different domains of quality of life within the context of the patient’s life. Lastly, the results clearly indicated the need for additional training of health care providers on how to assess and address spiritual well-being in cancer survivors.

There were limitations to this study, including use of a nonvalidated survey and cross-sectional approach that limited our ability to explore how concerns might change over the trajectory. Also, it was not possible to clarify medical information of the respondents, such as cancer stage. Although the response rate of this study was not high, we are confident in the results because of the large sample size and the finding that the large proportion of respondents with breast cancer was not influential. Despite these limitations, this needs assessment of cancer survivors over the trajectory of care provided insight into the scope of their concerns, identified vulnerable groups of survivors, and highlighted gaps in addressing those concerns. A quality- of-life framework for assessing needs assured a comprehensive focus and generated practice changes to strengthen holistic, comprehensive oncology care.

1. Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1117-1128.

2. Paterson C, Robertson A, Smith A, Nabi G. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: A systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:405-418.

3. Fiszer C, Dolbeault S, Sultan S, Bredart A. Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23:361-374.

4. Maguire R, Kotronoulas G, Simpson M, Paterson C. A systematic review of the supportive care needs of women living with and beyond cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:478-490.

5. Hall A, Lynagh M, Bryant J, Sanson-Fisher R. Supportive care needs of hematological cancer survivors: A critical review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:102-116.

6. Maguire R, Papadopoulou C, Kotronoulas G, Simpson MF, McPhelim J, Irvine L. A systematic review of supportive care needs of people living with lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:449-464.

7. Adler NE, Page EK. Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Institute of Medicine, 2008.

8. Ness S, Kokal J, Fee-Schroeder K, Novotny P, Satele D, Barton D. Concerns across the survivorship trajectory: results from a survey of cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:35-42.

9. Swash B, Hulbert-Williams N, Bramwell R. Unmet psychosocial needs in haematological cancer: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1131-1141.

10. Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: A systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:300-322.

11. Choi KH, Park JH, Park JH, Park JS. Psychosocial needs of cancer patients and related factors: A multi-center, cross-sectional study in Korea. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1073-1080.

12. Pauwels EE, Charlier C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lechner L, Van Hoof E. Care needs after primary breast cancer treatment. Survivors’ associated sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Psychooncology. 2013;22:125-132.

13. Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1117-1128.

14. Puchalski CM, Blatt B, Kogan M, Butler A. Spirituality and health: The development of a field. Academic Medicine. 2014;89:10-16.

15. Bai M, Lazenby M. A systematic review of associations between spiritual well-being and quality of life at the scale and factor levels in studies among patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:286-298.

16. Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:332-338.

17. Sharp L, Carsin AE, Timmons A. Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological wellbeing among individuals living with cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:745-755.

1. Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1117-1128.

2. Paterson C, Robertson A, Smith A, Nabi G. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: A systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:405-418.

3. Fiszer C, Dolbeault S, Sultan S, Bredart A. Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23:361-374.

4. Maguire R, Kotronoulas G, Simpson M, Paterson C. A systematic review of the supportive care needs of women living with and beyond cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:478-490.

5. Hall A, Lynagh M, Bryant J, Sanson-Fisher R. Supportive care needs of hematological cancer survivors: A critical review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:102-116.

6. Maguire R, Papadopoulou C, Kotronoulas G, Simpson MF, McPhelim J, Irvine L. A systematic review of supportive care needs of people living with lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:449-464.

7. Adler NE, Page EK. Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Institute of Medicine, 2008.

8. Ness S, Kokal J, Fee-Schroeder K, Novotny P, Satele D, Barton D. Concerns across the survivorship trajectory: results from a survey of cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:35-42.

9. Swash B, Hulbert-Williams N, Bramwell R. Unmet psychosocial needs in haematological cancer: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1131-1141.

10. Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: A systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:300-322.

11. Choi KH, Park JH, Park JH, Park JS. Psychosocial needs of cancer patients and related factors: A multi-center, cross-sectional study in Korea. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1073-1080.

12. Pauwels EE, Charlier C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lechner L, Van Hoof E. Care needs after primary breast cancer treatment. Survivors’ associated sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Psychooncology. 2013;22:125-132.

13. Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1117-1128.

14. Puchalski CM, Blatt B, Kogan M, Butler A. Spirituality and health: The development of a field. Academic Medicine. 2014;89:10-16.

15. Bai M, Lazenby M. A systematic review of associations between spiritual well-being and quality of life at the scale and factor levels in studies among patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:286-298.

16. Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:332-338.

17. Sharp L, Carsin AE, Timmons A. Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological wellbeing among individuals living with cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:745-755.