User login

Advice and Preparedness to Quit Smoking

Hospitalization may offer a natural opportunity to screen and advise patients on the advantages of quitting smoking due to a variety of reasons, such as the smoke‐free environment, availability of medical personnel, suitability of tailoring information, and the potential to catch a teachable moment.1, 2 Additionally, a recent meta‐analysis suggested that hospital‐based cessation programs and referrals to cardiac rehabilitation result in significantly higher rates of cessation among discharged smokers.3 In 2008, the U.S. Public Health Service Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence in hospitalized smokers recommended listing smoking status on problem lists, evaluating a smoker's preparedness to quit, providing counseling and medications to treat in‐hospital withdrawal symptoms, and arranging discharge follow‐up to help smokers remain abstinent.4 To promote these practices, the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) has made smoking cessation counseling a quality of care indicator for patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), or pneumonia. This indicator is a critical step in recognizing the importance of smoking cessation counseling in improving mortality and morbidity for these patients.

Despite the importance of promoting smoking cessation among hospitalized patients, few studies have looked at whether or not hospitalized patients are prepared to quit smoking. Ascertaining patients' preparedness to quit smoking is an important first step in understanding a patient's readiness to change their health behaviors because smoking cessation is the culmination of a lengthy process of behavior change.5 Studies of healthy factory workers suggest that smokers who were more prepared to quit smoking had a higher number of previous quit attempts and perceived coworker encouragement.6

Understanding patient preparedness to quit smoking is especially important among African American smokers, who face a disproportionate health burden due to smoking‐related illness. Studies show that African Americans are less likely than other racial groups to engage in formal tobacco cessation interventions and have lower long‐term quit rates, despite a higher desire to quit smoking.5, 79 Understanding preparedness to quit among this particular group of hospitalized patients may be an important first step in identifying those most likely to quit and benefit from tailored, intensive interventions, such as using medications to assist in combination with postdischarge tobacco cessation counseling.

The aim of this study was to characterize the preparedness to quit smoking and to assess quit attempts made, methods used for quitting, and the success of such quit attempts at 1‐month follow‐up in a group comprised of a high proportion of underserved African American hospitalized smokers. In addition, the relationship of hospitalized patients' preparedness to quit and the effect of inpatient advice on the likelihood of subsequent tobacco cessation were examined.

Patients and Methods

The data used for this study were collected for the Cardiology Quality of Care Study, an ongoing prospective study of patients hospitalized on the inpatient cardiology service at the University of Chicago Medical Center. Newly admitted patients were approached by research assistants and consented to the study using a previously described protocol for enrolling hospitalized patients.10 Patients that lacked decisional capacity (score of <17 on the telephone version of the Mini‐Mental Status Exam)11 were excluded. Patients did not receive any scripted intervention during this admission to assist with cessation. The study left cessation counseling and advice to quit up to the discretion of the individual physician caring for the patient in the hospital. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Chicago approved this study.

Inpatient Interview

The inpatient interview is a 60‐item questionnaire taking approximately 15 minutes to administer by trained research assistants. The questionnaire is designed to assess demographic characteristics (race, socioeconomic status, education, sex, and age), smoking habits, and preparedness to quit. Demographics were collected on all consented patients. Seven items focused on cigarette smoking, consistent with questions in the National Health Information Survey.12 Patients were classified as lifetime smokers if they smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. To identify current smokers on admission, patients were asked if they now smoke cigarettes some days or everyday. Additionally, smokers were asked if they had made any quit attempts in the past 12 months.

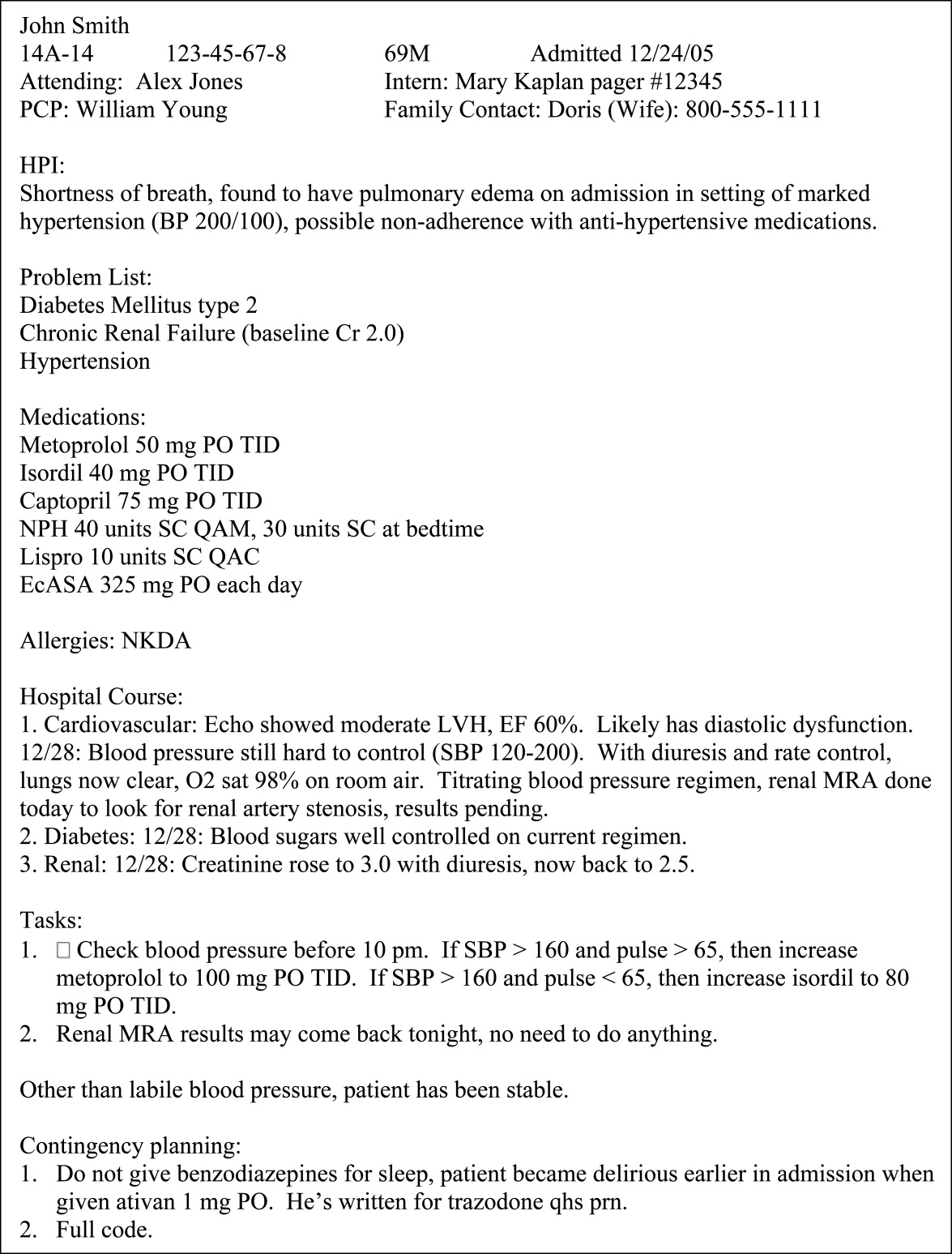

Patients rated their level of preparedness using a modified version of the Biener Abrams Contemplation Ladder. The Contemplation Ladder is an easily‐administered tool represented by a ladder image of rungs with anchor statements developed as an alternative method to the Prochaska and DiClemente Stages of Change.13 The 10‐point scale ranges from 1 (I enjoy smoking and have decided not to quit smoking for my lifetime; I have no interest in quitting) to 10 (I have quit smoking and will never smoke again.) Tobacco users may rank their current level of motivation to quit. A level of 6 (I definitely plan to quit smoking in the next 6 months) or higher is consistent with preparedness to quit. The Contemplation Ladder was validated by Biener and Abrams6 in a work site study which demonstrated that subjects with higher Ladder scores (score 6) were more likely than those with lower Ladder scores (scores < 6) to participate in awareness activities (eg, educational session) and make a quit attempt in 6 months. This instrument is easier to administer than the more well known Transtheoretical Model of Change, given that it is an ordinal scale with clear steps that may be more user‐friendly for both clinicians and patients.6 In a prior study of emergency room patients, an individual's Ladder score was shown to be significantly associated with a patient's reported intention to quit, number of previous quit attempts, perceived coworker encouragement, and socioeconomic status.14

Admission Diagnoses

Chart audit was performed by trained research assistants at the time of the inpatient interview (within 24 hours of admission) to assess whether patients were admitted with the potential diagnoses of AMI, CHF, neither, or both. All were based on the chart documentation of the patients' clinical presentation. This information was used to assess which CMS Quality Indicators applied to cardiology patients, given that smoking cessation is now a quality indicator for patients with AMI or CHF.

Thirty‐day Follow‐up Telephone Survey

Trained research assistants interviewed patients by telephone at approximately 1 month postdischarge. The follow‐up telephone survey included routine questions concerning follow‐up appointments, readmissions, emergency room visits, and patient satisfaction.15, 10 An additional 5 questions related to smoking cessation were added for this study. Questions were developed using the CMS quality indicators16 or were taken from the National Health Information Survey.12 Patients were asked to self‐report quit attempts made postdischarge, whether or not these quit attempts were associated with success (self‐reported abstinence at the time of follow‐up), and what methods were used to quit (ie, nicotine replacement therapy [NRT], other pharmacotherapy, quit line, pamphlet, counseling group, or cold turkey.) Patients were also asked if they recalled receiving advice to quit during their hospitalization from either a nurse or physician.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize Contemplation Ladder scores and types of quit methods used. Chi square tests were used to assess the effect of preparedness (Ladder score 6) on quit behaviors. The main quit behavior was any self‐reported quit attempt made within 1 month after discharge. Additionally, the relationship between preparedness and making a successful quit attempt (defined as a self‐report of not smoking as a result of this quit attempt in the last month) was examined. Multivariate logistic regression, controlling for demographic characteristics, was performed to test the effect of preparedness on quit behaviors (any quit attempt after discharge, or successful quit attempt). While not a primary aim of this study, the association between recall of in‐hospital advice and quit behaviors after discharge was also examined using chi square tests and multivariate logistic regression models, controlling for the demographic characteristics as above. Models also tested the effect of preparedness and recall of in‐hospital advice as independent predictors on quit behaviors and whether or not an interaction between preparedness and advice existed. A linear test of trend was also performed on preparedness and advice. All statistical tests were performed using Intercooled Stata 9.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX), with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

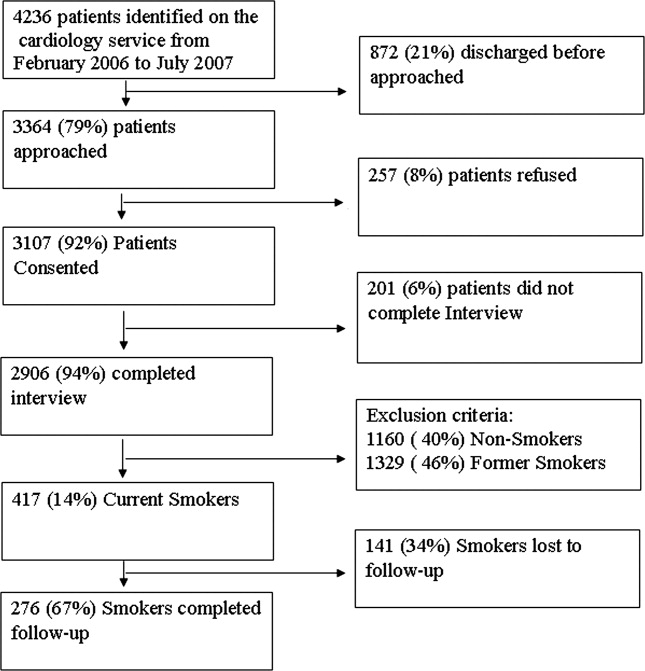

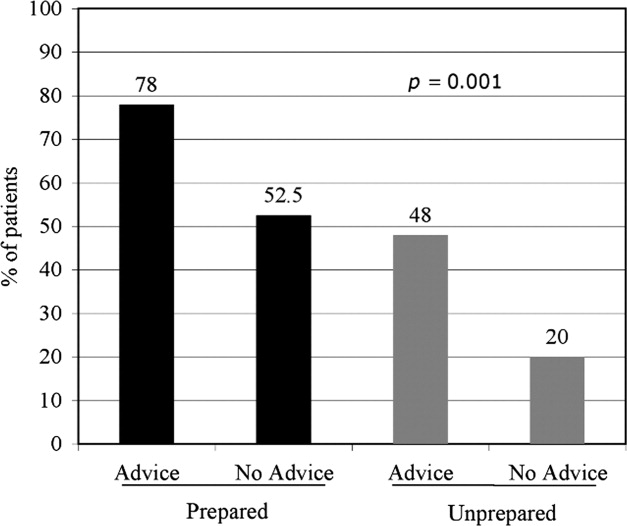

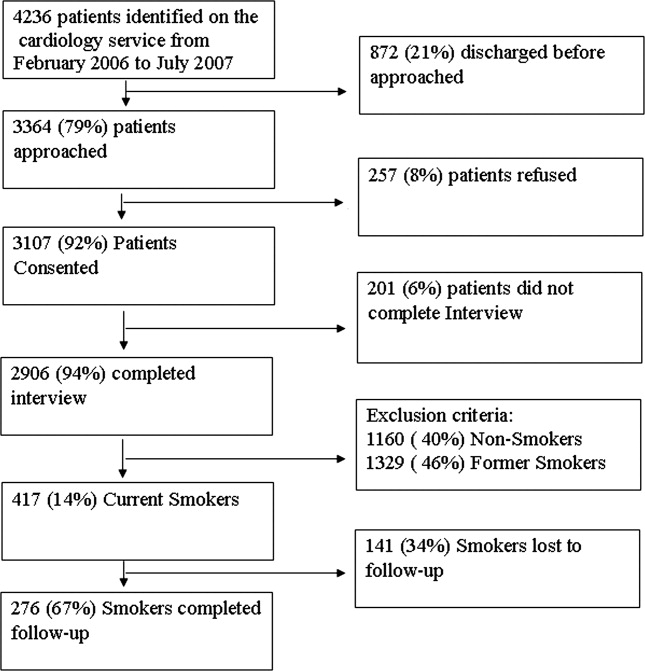

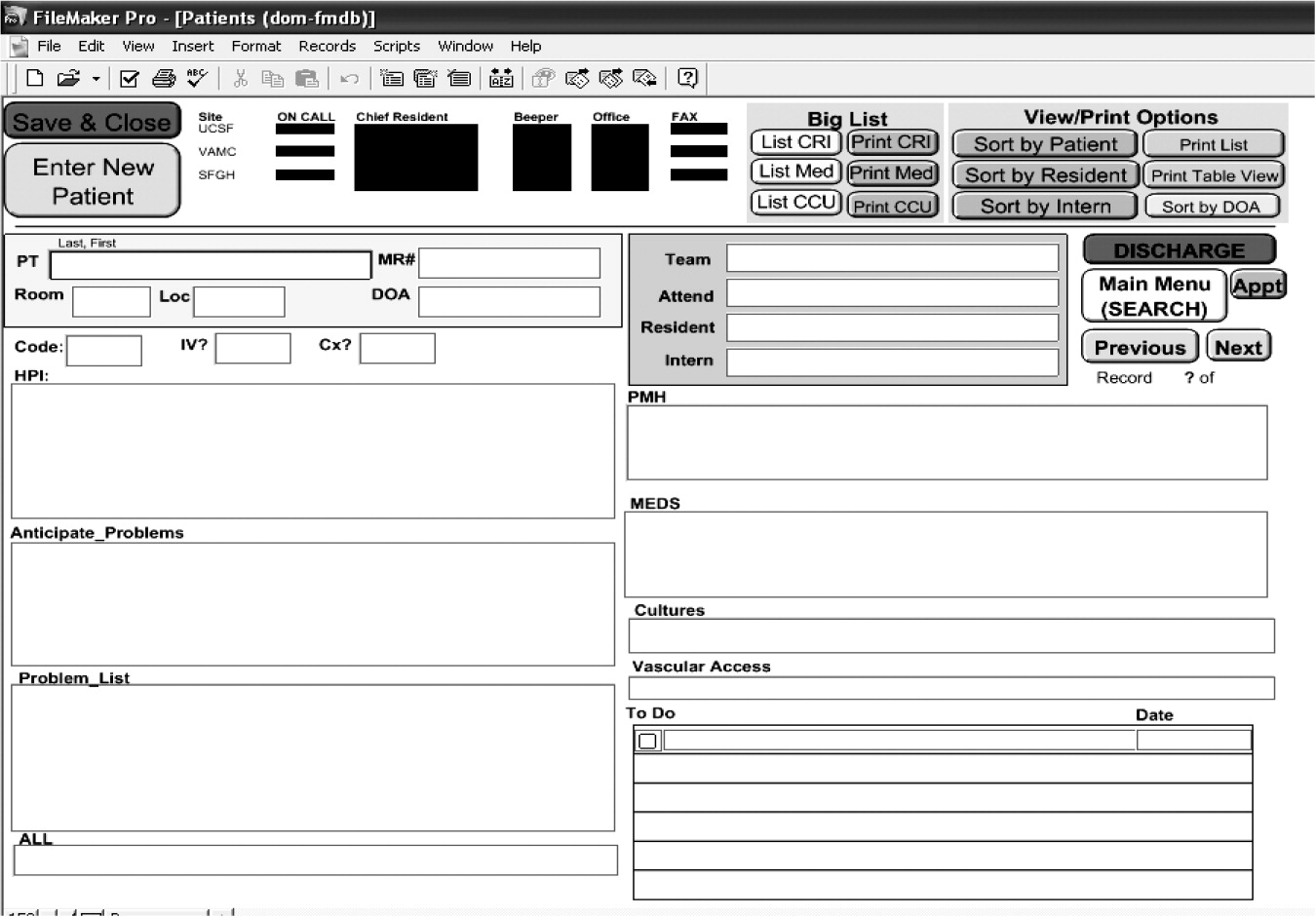

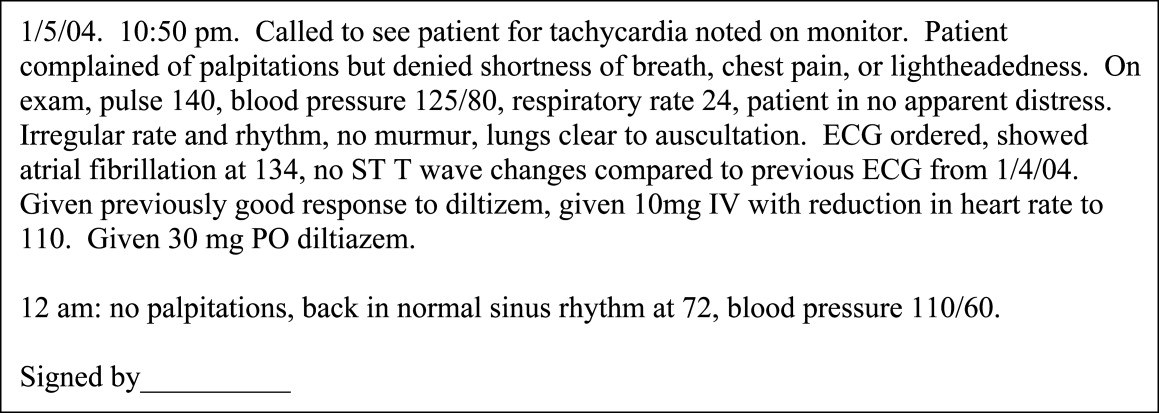

From February 2006 through July 2007, 86% (2906/3364) of all cardiology inpatients approached were interviewed. Fifteen percent (436/2906) of patients enrolled in the study indicated that they were current smokers. Contemplation Ladder scores were obtained on 95% (415/436) of the current smokers, and 1‐month postdischarge follow‐up telephone surveys were completed in 67% (276/415) of the current smokers. Three attempts were made to contact patients who were lost to follow‐up (Figure 1). The major reasons for inability to contact patients included wrong telephone numbers, disconnected phone lines, or no method to leave a message for the patient (ie, no answering machine). Given that we were only able to complete follow‐up interviews on 276 patients, we conducted our analyses on only this group of patients.

The average age of current smokers in the sample was 55 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 54‐58). Most current smokers were of the African American race (83%; 224/276). More than 65% of smokers had completed high school or higher, and nearly one‐half (46%) had an average household income of $25,000 or less before taxes. The most common admitting diagnoses per chart audit among current inpatient smokers were AMI (31%) and CHF (27%). The vast majority (95%) of hospitalized smokers in this sample were first‐time admissions to the University of Chicago. Table 1 shows the demographic data for current smokers compared to former smokers (those who have quit smoking prior to admission). Current smokers were more likely to be African American, had lower income levels, and were less likely to have completed high school. Additionally, current smokers were more likely to carry a potential diagnosis of AMI or CHF and to be a first‐time admission (Table 1).

| Demographic Variables | Current Smokers (n = 276)* | Nonsmoker (n = 1329)* | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Male sex | 156 (57) | 705 (53) | 0.22 |

| African American race | 224 (83) | 886 (67) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 55.3 | 64.0 | <0.001 |

| Highest completed level of education | 0.02 | ||

| Junior high school or less | 15 (6) | 98 (7) | |

| Some high school | 67 (25) | 230 (17) | |

| High school graduate | 81 (30) | 403 (31) | |

| Some college education | 68 (25) | 313 (24) | |

| College graduate | 19 (7) | 135 (10) | |

| Graduate level education | 11 (4) | 96 (7) | |

| Household income before taxes | 0.001 | ||

| <$2500 | 33 (12) | 79 (6) | |

| $2501‐$15,000 | 66 (24) | 334 (26) | |

| $15,001‐$50,000 | 51 (19) | 311 (24) | |

| 50,001‐$100,000 | 22 (8) | 126 (9) | |

| >$100,001 | 11 (4) | 50 (4) | |

| Did not answer | 88 (33) | 422 (32) | |

| Diagnosis on admission | 0.02 | ||

| AMI | 66 (31) | 269 (24) | |

| CHF | 58 (27) | 287 (25) | |

| Both | 49 (23) | 273 (24) | |

| Neither | 42 (19) | 305 (27) | |

| Admission status | |||

| New admission | 258 (95) | 1,154 (87) | 0.051 |

| Readmission | 14 (5) | 175 (13) | |

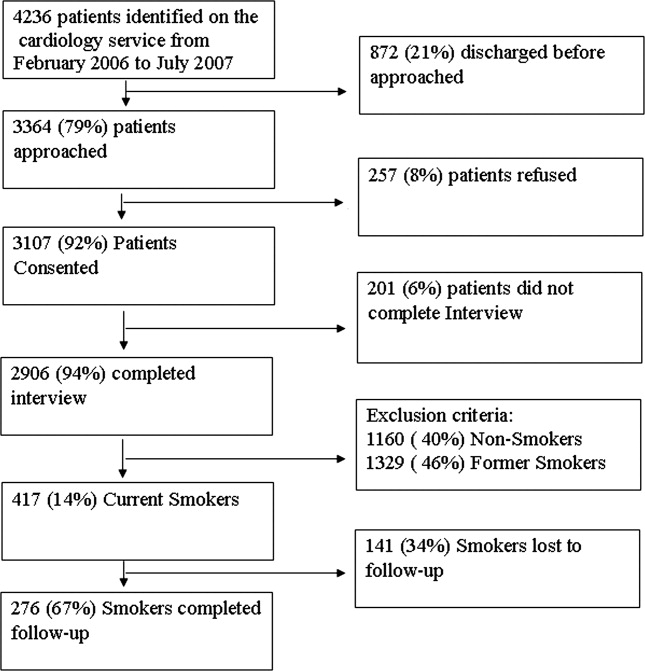

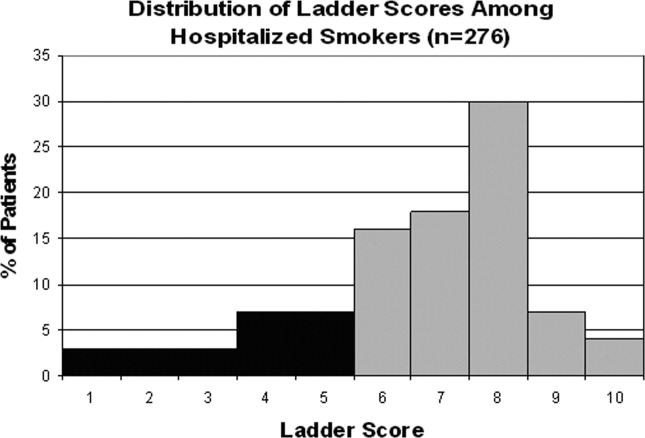

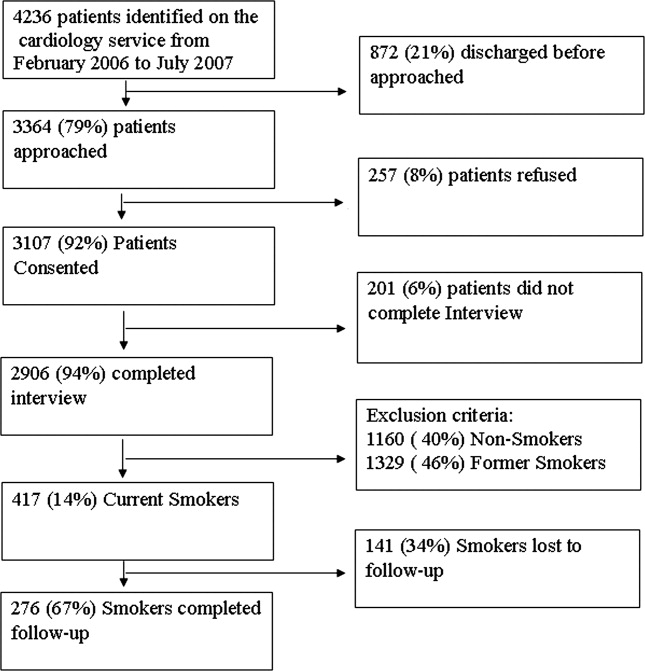

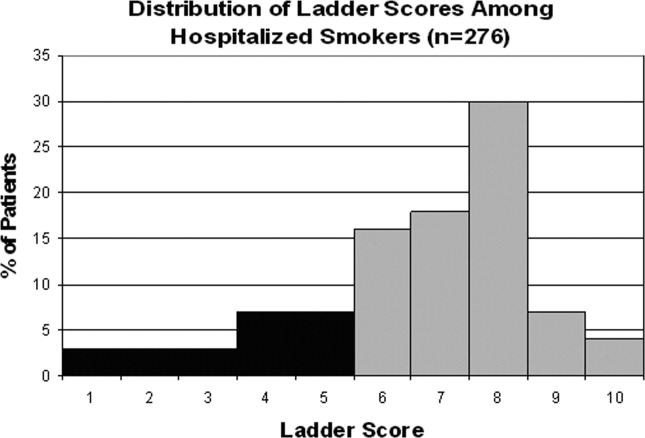

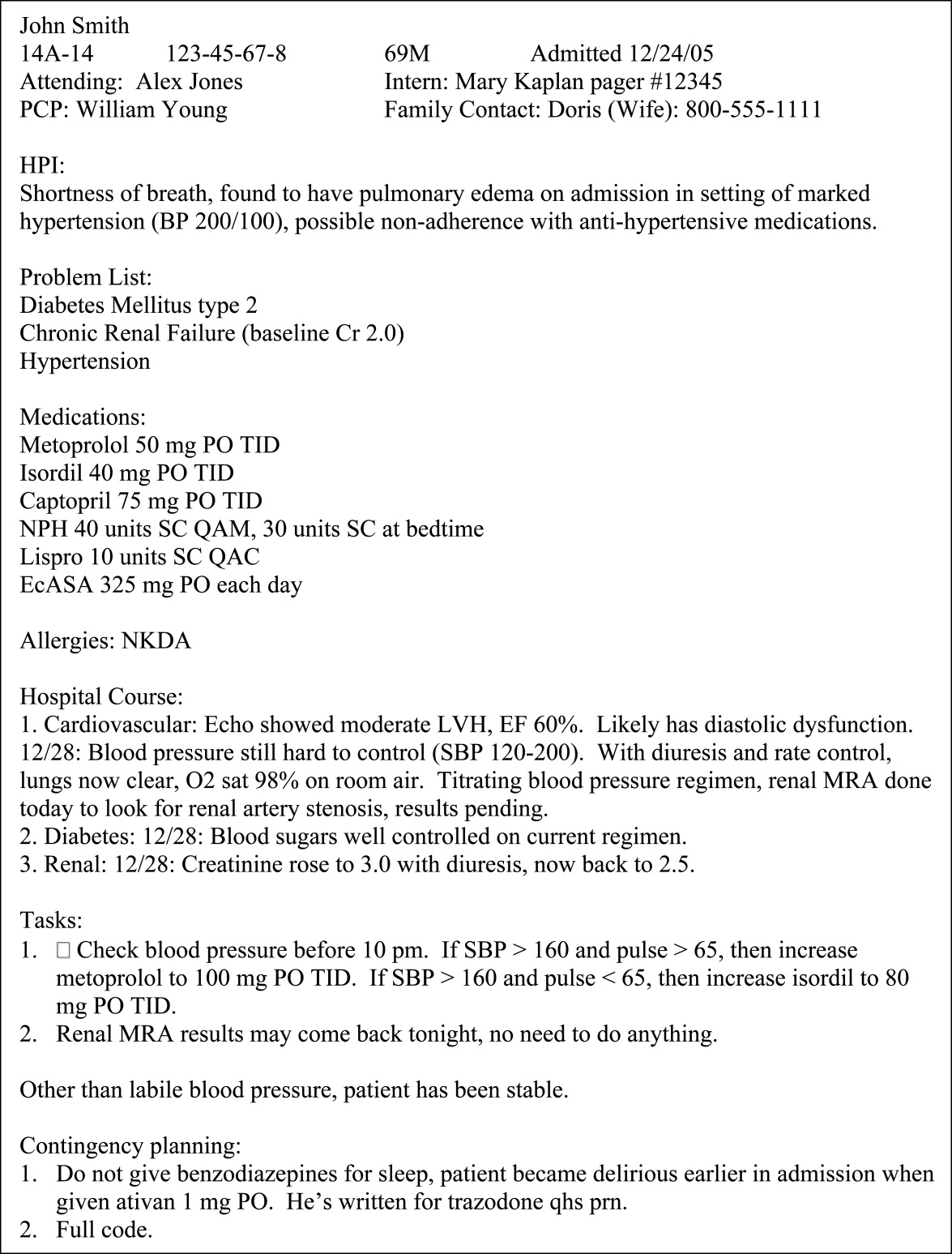

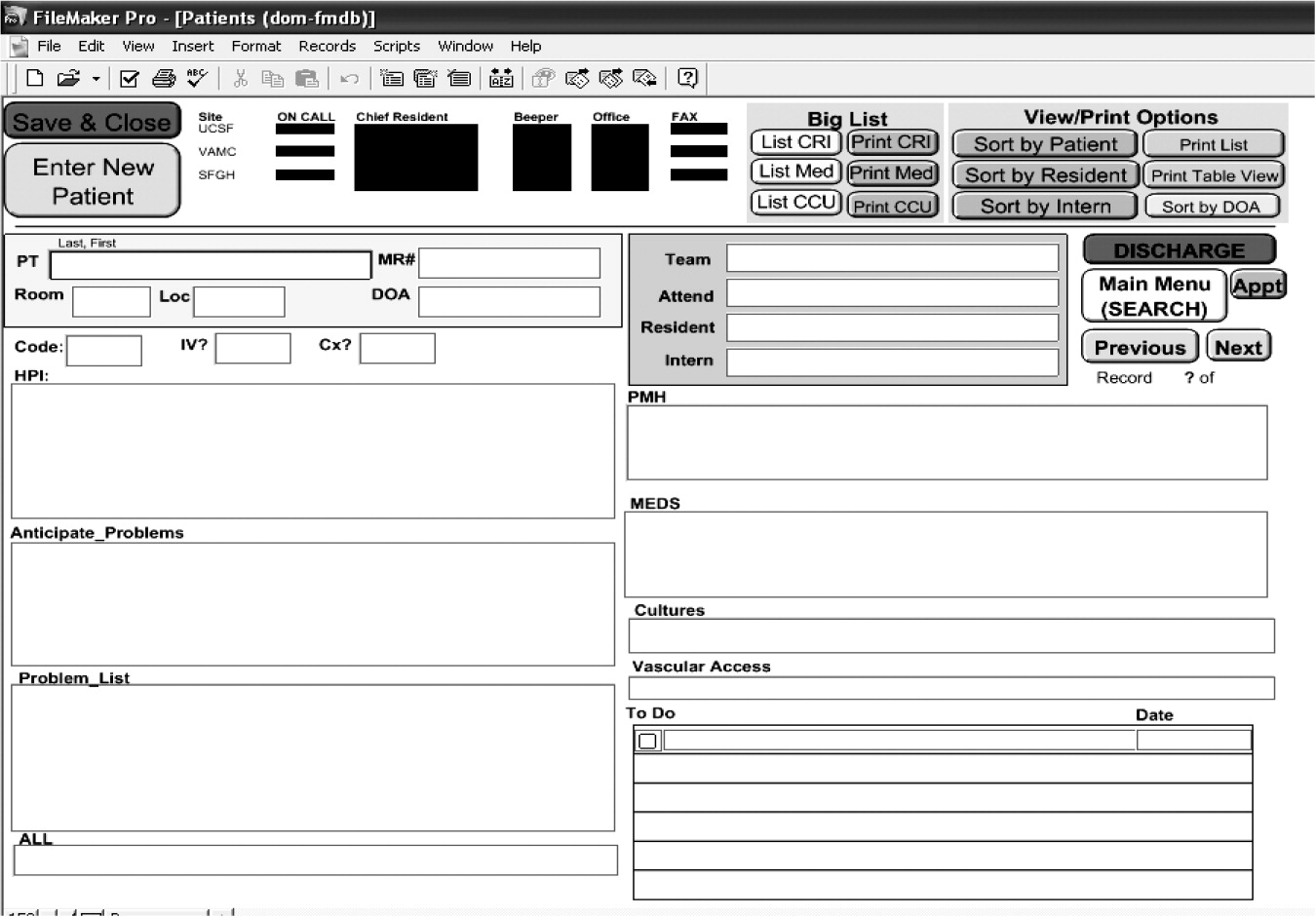

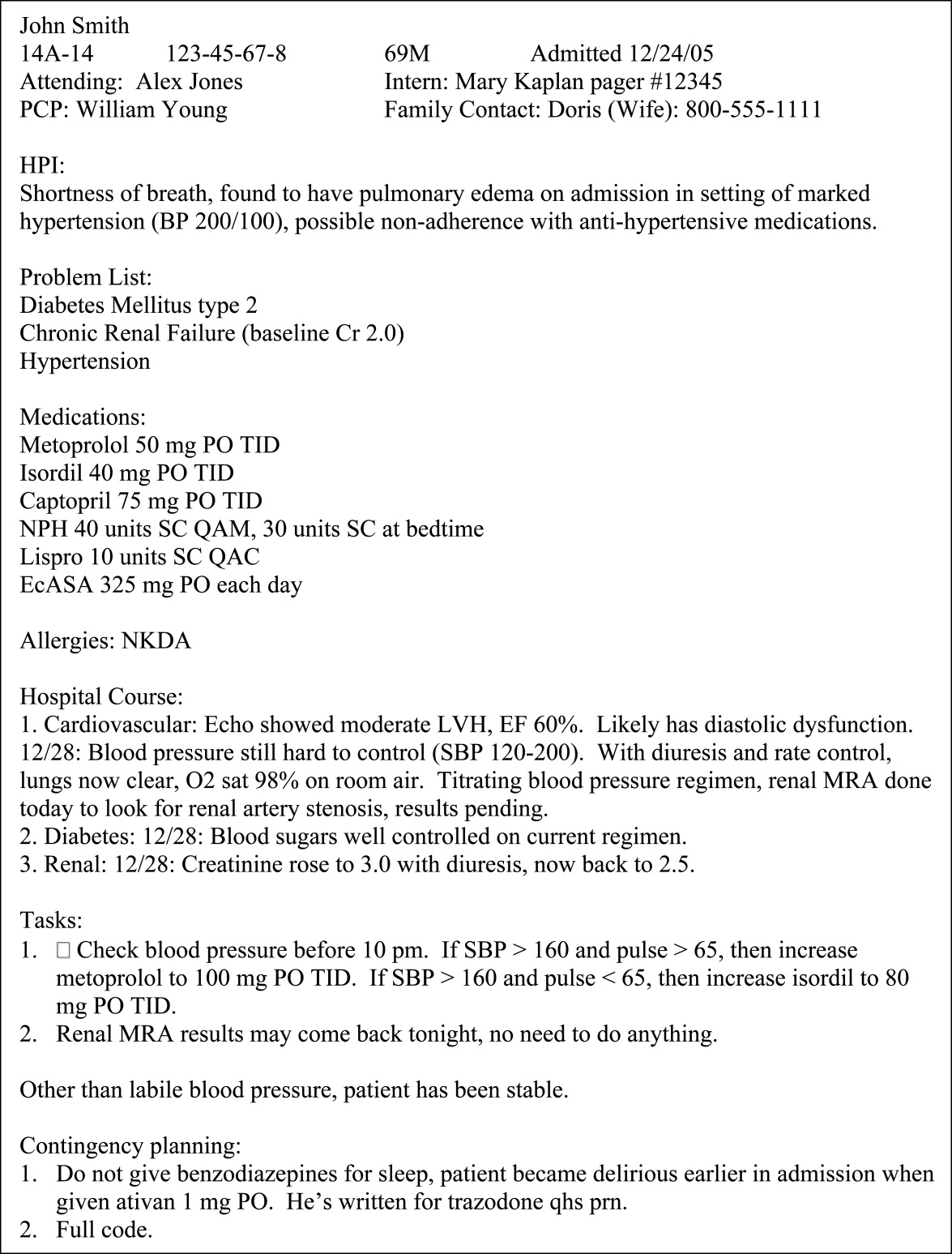

Approximately three‐quarters (76%; 210/276) of current smokers were identified as prepared to quit, with a Ladder score 6. There was a wide distribution of Ladder scores, with one‐third (31%; 86/276) of smokers reporting a Ladder score of 8, indicating that they still smoke, but are ready to set a quit date and another 34% (95/276 patients) with Ladder scores of either 6 or 7 also indicating they were planning to quit smoking (Figure 2). A significant portion of smokers (71%; 195/276) reported making a quit attempt after discharge, and 38% of smokers (106/276) self‐reported that their quit attempt was successful (ie, no longer smoking at 1 month post discharge). Note that the quit rate is reduced to 26% (106/415) at 1 month if one conservatively assumes that those who did not take part in follow‐up were relapsers. Among those who did participate in follow‐up, as shown in Figure 3, the most frequently reported (53%; 145/276) method used to quit smoking was cold turkey. Thirteen percent (37/276) of patients reported making a quit attempt using pharmacological therapy (ie, NRT or bupropion) and only 4% (12/276) of patients reported making a quit attempt using the help of a smoking cessation program (Figure 3).

Preparedness was an important predictor of making a quit attempt. Prepared patients (ie, Ladder score 6) were significantly more likely than patients who were less prepared to report making a quit attempt after discharge (163/212 [77%] vs. 32/64 [50%], respectively; P < 0.001). This result remained significant after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics with a similar effect size (adjusted estimates 76% [95% CI, 75.7‐76.7] prepared vs. 49% [95% CI, 48.5‐49.8]; P < 0.001). These results also remained significant with a similar effect size in analyses using multivariate logistic regression (Table 2). Of those patients who made quit attempts, prepared patients were slightly more likely to report a successful quit attempt (90/163; 55%) than were less‐prepared patients (16/32; 50%), though this was not significant (P = 0.205).

| Statistical test | Quit Behavior | Prepared % (95% CI) | Unprepared % (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Chi square tests | Any quit attempt made after discharge | 76.9 (71.2‐82.6) | 50.0 (37.8‐62.2) | <0.001 |

| Successful quit attempt at time of follow‐up | 55.0 (45.9‐60.2) | 50.0 (25.4‐58.2) | 0.20 | |

| Multivariate logistic regression* | Any quit attempt made after discharge | 76.2 (75.7‐76.7) | 49.2 (48.5‐49.9) | <0.001 |

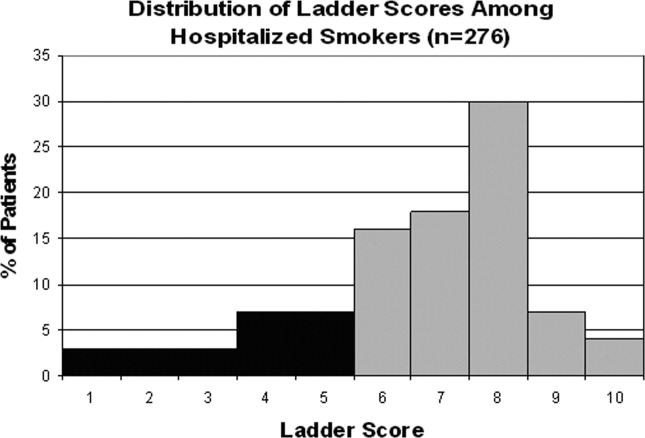

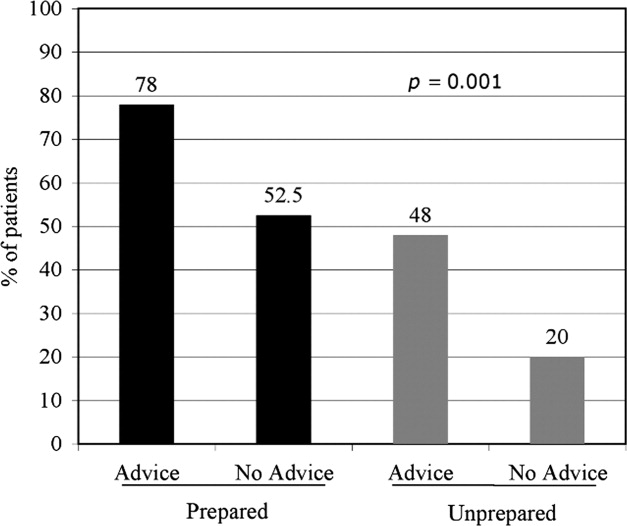

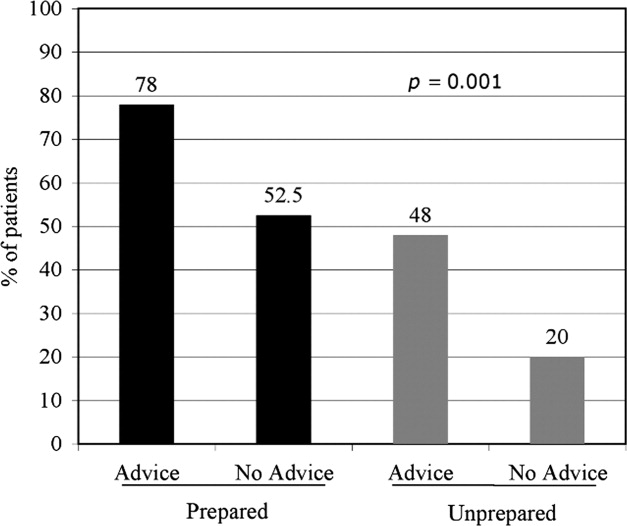

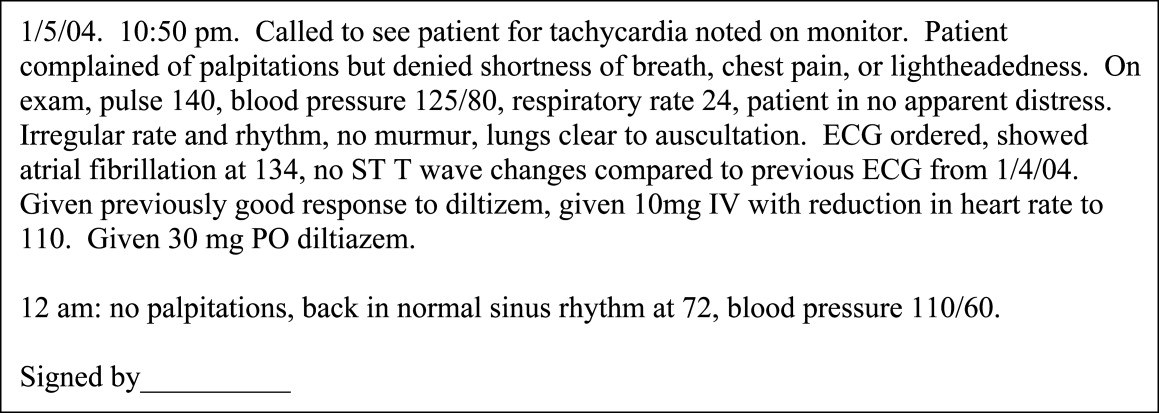

In the follow‐up sample, 17% could not remember if they received advice to quit smoking. Among those who were able to recall receiving advice, the majority (78%; 180/230) reported that they received advice from a nurse or physician during hospitalization, compared to 22% who did not recall ever being advised to quit by any healthcare provider during the admission. Patients who reported receiving advice to quit were more likely to report making a quit attempt postdischarge as compared to those that did not recall receiving advice (70% vs. 46%, respectively; P = 0.002). In a multivariate logistic regression, controlling for demographic factors and admitting diagnosis, both preparedness and receipt of in‐hospital advice were independent predictors of making a future quit attempt (odds ratio [OR] = 4.05; 95% CI, 1.91‐8.60; P < 0.001 for preparedness; OR = 3.96; 95% CI, 1.84‐8.54; P < 0.001 for advice). Additionally, there was no significant interaction or synergistic effect between being prepared to quit smoking and receiving in‐hospital advice to quit (OR = 1.24; 95% CI, 0.17‐9.21; P = 0.836) (Figure 4). When analyzing the effects of preparedness and advice on quit attempts, only preparedness to quit remained a significant predictor of a successful quit attempt (OR = 2.93; 95% CI, 1.13‐7.60; P = 0.027 for preparedness; OR = 2.16; 95% CI, 0.85‐5.49; P = 0.10 for advice to quit). As demonstrated in Table 2, a higher percentage of prepared patients made a quit attempt after discharge (76.9% vs. 50%) and had a successful quit attempt and short‐term abstinence (55% prepared patients vs. 50% less prepared patients).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that in a group of hospitalized underserved, and predominantly African American smokers, the majority of patients reported being prepared to quit smoking at the time of hospitalization. Prepared patients were more likely to report making a quit attempt after discharge and more likely to report being successful in their quit attempt than patients who reported being less prepared to quit during their hospitalization. Nevertheless, approximately one‐half of unprepared patients did make a quit attempt 1 month after discharge, demonstrating a desire to quit smoking after hospitalization among this population. However, short‐term success rates in this group were lower than in patients prepared to quit. In addition, preparedness to quit and receipt of in‐hospital advice to quit smoking were both found to be independent predictors of making a quit attempt, with nearly identical ORs; however, only preparedness remained significant after controlling for advice to quit. Last, although the majority of hospitalized cardiac patients were making quit attempts after discharge, most patients reported using the least effective quit methods (ie, cold turkey) rather than more effective and intensive interventions such as counseling in combination with pharmacotherapy.

These findings have important implications for current quality initiatives targeted at promoting smoking cessation among cardiac patients. First, these results highlight the need for evidence‐based methods to be made available to hospitalized smokers who are prepared to quit. Our results are consistent with other studies reporting rare use (5.2%) of NRT in the hospital setting, despite the proven benefit in treating nicotine withdrawal symptoms.17 This is also consistent with data reporting that among nonhospitalized smokers, quitting cold turkey was the most commonly used and least effective cessation method.18 Second, the rate of recall of in‐hospital advice among patients (78%) was generally consistent with those reported to CMS (most recent quarter 95% for AMI and 88% for CHF).19

In addition to receiving advice, preparedness to quit was associated with higher quit attempts, therefore highlighting the importance of assessing level of preparedness in addition to giving advice. The fact that most quit attempts were made using cold turkey and resulted in low short‐term success rates underscores the need to reevaluate the current CMS quality indicator of advice alone for hospitalized smokers. Furthermore, the recently updated 2008 U.S. Public Health guidelines recently recommend, in addition to advice, that all hospitalized smokers be assessed for readiness to change, be assisted in quitting with pharmacotherapy, and be arranged follow‐up for tobacco cessation postdischarge, highlighting the inadequacy of advice alone.4 While it is important to continue to advise all hospitalized smokers to quit, the study findings demonstrate that assessing preparedness may result in targeting more prepared patients with more intensive interventions. Further policy implications include that less prepared patients may need motivational techniques to increase their level of preparedness to quit during hospitalization.

Several limitations are worth mentioning. First, the study included a relatively small sample size drawn from a single urban medical center. The prevalence of current smokers in our sample was 15%, which is lower than many studies looking at cardiology inpatient smokers.3, 20 This limitation of our study may be attributed to the advanced age of the majority of our patients, as compared with other studies, as well as the possibility of socially desirable response bias that many low‐income African American smokers may experience, leaving them less likely to admit to smoking at the time of hospitalization. Second, there was a low follow‐up rate, with 66% of patients undergoing follow‐up postdischarge. While this may raise the concerns of differences between ladder scores in those patients that participated in follow‐up and those that did not, analyses show no significant difference between level of preparedness in these 2 groups (68% prepared in patients who received follow‐up vs. 63% prepared patients in those who did not participate in follow‐up; P = 0.36). Third, follow‐up of quit attempts and receipt of advice were all assessed using self‐report, and, therefore, were limited by lack of verification and lack of assessment for potential recall bias. Fourth, in this pilot study, the follow‐up period was relatively short at 1 month postdischarge. It is likely that rates of successful quit attempts would be lower with longer‐term follow‐up periods, given previous literature demonstrating the difficulty with long‐term abstinence.21 Last, the study was not able to account for potential effects that hospitalization itself may have on preparedness, as patients may be more likely to report being prepared to quit when in the face of a health shock,22 as well as the fact that some patients may demonstrate a socially desirable response bias influenced by hospitalization.

In conclusion, the majority of underserved smokers with cardiac disease reported being prepared to quit smoking and were more likely to self‐report making a quit attempt after discharge. However, the majority of these quit attempts were made via cold turkey, without the support of available evidence‐based methods to quit. It is possible that by directly providing education, access to pharmacotherapy, and counseling options, the utilization rates for more efficacious treatments would increase in cardiac patients who are prepared to quit. While recall of in‐hospital advice was associated with future quit attempts, prepared patients who recalled receiving advice were more likely to make a quit attempt than prepared patients who did not recall receiving advice, as well as unprepared patients. Together, these findings highlight the need to consider a patient's level of preparedness to quit in understanding the success of in‐hospital advice and the importance of making evidence‐based cessation methods available to hospitalized smokers who are prepared to quit. Additionally, identifying patients not prepared to quit may help in providing them with appropriate motivational therapy, to move them along the stages of change, as well as educational information on how to quit once they have decided to do so.

- ,,.Helping hospitalized smokers quit: new directions for treatment and research.J Consult Clin Psychol.1993;61:778–789.

- ,.Smokers who are hospitalized: a window of opportunity for cessation interventions.Prev Med.1992;21:262–269.

- ,,, et al.Predictors of smoking cessation after a myocardial infarction: the role of institutional smoking cessation programs in improving success.Arch Intern Med.2008;168(18):1961–1967.

- Guideline Panel.Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence.Washington, DC:Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services;2008.

- ,.Stages and processes of self‐change in smoking: toward an integrative model of change.J Consult Clin Psychol.1983;51:390–395.

- ,.The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation.Health Psychol.1991;10(5):360–365.

- ,,,,.Smoking cessation factors among African Americans and Whites.Am J Public Health.1993;83(2):220–226.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation.Rockville, MD:Office on Smoking and Health, Centers for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Public Health Service,U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,Washington, DC;2000.

- ,,,,.Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. the changing influence of gender and race.JAMA.1989;261(1):49–55.

- ,,, et al.Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists.Ann Intern Med.2002;137(11):866–874.

- ,,,.Validation of a telephone version of the Mini‐Mental State Examination.J Am Geriatr Soc.1992;40(7):697–702.

- National Health Information Survey Questionnaire, Sample Adult,Adult Health Behaviors;2004.

- ,,, et al.The Marijuana Ladder: measuring motivation to change marijuana use in incarcerated adolescents.Drug Alcohol Depend.2006;83:42–48.

- ,,,,.Motivation for stopping tobacco use among emergency department patients.Acad Emerg Med.2005;12:568–571.

- Picker‐Commonwealth Survey of Patient‐Centered Care.Health Aff.1991.

- Hospital Quality Initiatives. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HospitalQualtiyInits. Accessed April2009.

- ,,, et al.The use of nicotine replacement therapy by hospitalized smokers.Am J Prev Med.1999;17(4):255–259.

- ,,,,.Methods used to quit smoking in the United States: do cessation programs help?JAMA.1990;263(20):2795–2796.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.Hospital Compare.2006 Data Graphs. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Accessed April2009.

- ,,, et al.Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2006.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2007;56:1157–1161.

- ,,.Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers.Arch Intern Med.2008;168(18):1950–1960.

- ,.Health beliefs and smoking patterns in heart patients and their wives: a longitudinal study.Am J Public Health.1977;67:921–930.

Hospitalization may offer a natural opportunity to screen and advise patients on the advantages of quitting smoking due to a variety of reasons, such as the smoke‐free environment, availability of medical personnel, suitability of tailoring information, and the potential to catch a teachable moment.1, 2 Additionally, a recent meta‐analysis suggested that hospital‐based cessation programs and referrals to cardiac rehabilitation result in significantly higher rates of cessation among discharged smokers.3 In 2008, the U.S. Public Health Service Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence in hospitalized smokers recommended listing smoking status on problem lists, evaluating a smoker's preparedness to quit, providing counseling and medications to treat in‐hospital withdrawal symptoms, and arranging discharge follow‐up to help smokers remain abstinent.4 To promote these practices, the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) has made smoking cessation counseling a quality of care indicator for patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), or pneumonia. This indicator is a critical step in recognizing the importance of smoking cessation counseling in improving mortality and morbidity for these patients.

Despite the importance of promoting smoking cessation among hospitalized patients, few studies have looked at whether or not hospitalized patients are prepared to quit smoking. Ascertaining patients' preparedness to quit smoking is an important first step in understanding a patient's readiness to change their health behaviors because smoking cessation is the culmination of a lengthy process of behavior change.5 Studies of healthy factory workers suggest that smokers who were more prepared to quit smoking had a higher number of previous quit attempts and perceived coworker encouragement.6

Understanding patient preparedness to quit smoking is especially important among African American smokers, who face a disproportionate health burden due to smoking‐related illness. Studies show that African Americans are less likely than other racial groups to engage in formal tobacco cessation interventions and have lower long‐term quit rates, despite a higher desire to quit smoking.5, 79 Understanding preparedness to quit among this particular group of hospitalized patients may be an important first step in identifying those most likely to quit and benefit from tailored, intensive interventions, such as using medications to assist in combination with postdischarge tobacco cessation counseling.

The aim of this study was to characterize the preparedness to quit smoking and to assess quit attempts made, methods used for quitting, and the success of such quit attempts at 1‐month follow‐up in a group comprised of a high proportion of underserved African American hospitalized smokers. In addition, the relationship of hospitalized patients' preparedness to quit and the effect of inpatient advice on the likelihood of subsequent tobacco cessation were examined.

Patients and Methods

The data used for this study were collected for the Cardiology Quality of Care Study, an ongoing prospective study of patients hospitalized on the inpatient cardiology service at the University of Chicago Medical Center. Newly admitted patients were approached by research assistants and consented to the study using a previously described protocol for enrolling hospitalized patients.10 Patients that lacked decisional capacity (score of <17 on the telephone version of the Mini‐Mental Status Exam)11 were excluded. Patients did not receive any scripted intervention during this admission to assist with cessation. The study left cessation counseling and advice to quit up to the discretion of the individual physician caring for the patient in the hospital. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Chicago approved this study.

Inpatient Interview

The inpatient interview is a 60‐item questionnaire taking approximately 15 minutes to administer by trained research assistants. The questionnaire is designed to assess demographic characteristics (race, socioeconomic status, education, sex, and age), smoking habits, and preparedness to quit. Demographics were collected on all consented patients. Seven items focused on cigarette smoking, consistent with questions in the National Health Information Survey.12 Patients were classified as lifetime smokers if they smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. To identify current smokers on admission, patients were asked if they now smoke cigarettes some days or everyday. Additionally, smokers were asked if they had made any quit attempts in the past 12 months.

Patients rated their level of preparedness using a modified version of the Biener Abrams Contemplation Ladder. The Contemplation Ladder is an easily‐administered tool represented by a ladder image of rungs with anchor statements developed as an alternative method to the Prochaska and DiClemente Stages of Change.13 The 10‐point scale ranges from 1 (I enjoy smoking and have decided not to quit smoking for my lifetime; I have no interest in quitting) to 10 (I have quit smoking and will never smoke again.) Tobacco users may rank their current level of motivation to quit. A level of 6 (I definitely plan to quit smoking in the next 6 months) or higher is consistent with preparedness to quit. The Contemplation Ladder was validated by Biener and Abrams6 in a work site study which demonstrated that subjects with higher Ladder scores (score 6) were more likely than those with lower Ladder scores (scores < 6) to participate in awareness activities (eg, educational session) and make a quit attempt in 6 months. This instrument is easier to administer than the more well known Transtheoretical Model of Change, given that it is an ordinal scale with clear steps that may be more user‐friendly for both clinicians and patients.6 In a prior study of emergency room patients, an individual's Ladder score was shown to be significantly associated with a patient's reported intention to quit, number of previous quit attempts, perceived coworker encouragement, and socioeconomic status.14

Admission Diagnoses

Chart audit was performed by trained research assistants at the time of the inpatient interview (within 24 hours of admission) to assess whether patients were admitted with the potential diagnoses of AMI, CHF, neither, or both. All were based on the chart documentation of the patients' clinical presentation. This information was used to assess which CMS Quality Indicators applied to cardiology patients, given that smoking cessation is now a quality indicator for patients with AMI or CHF.

Thirty‐day Follow‐up Telephone Survey

Trained research assistants interviewed patients by telephone at approximately 1 month postdischarge. The follow‐up telephone survey included routine questions concerning follow‐up appointments, readmissions, emergency room visits, and patient satisfaction.15, 10 An additional 5 questions related to smoking cessation were added for this study. Questions were developed using the CMS quality indicators16 or were taken from the National Health Information Survey.12 Patients were asked to self‐report quit attempts made postdischarge, whether or not these quit attempts were associated with success (self‐reported abstinence at the time of follow‐up), and what methods were used to quit (ie, nicotine replacement therapy [NRT], other pharmacotherapy, quit line, pamphlet, counseling group, or cold turkey.) Patients were also asked if they recalled receiving advice to quit during their hospitalization from either a nurse or physician.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize Contemplation Ladder scores and types of quit methods used. Chi square tests were used to assess the effect of preparedness (Ladder score 6) on quit behaviors. The main quit behavior was any self‐reported quit attempt made within 1 month after discharge. Additionally, the relationship between preparedness and making a successful quit attempt (defined as a self‐report of not smoking as a result of this quit attempt in the last month) was examined. Multivariate logistic regression, controlling for demographic characteristics, was performed to test the effect of preparedness on quit behaviors (any quit attempt after discharge, or successful quit attempt). While not a primary aim of this study, the association between recall of in‐hospital advice and quit behaviors after discharge was also examined using chi square tests and multivariate logistic regression models, controlling for the demographic characteristics as above. Models also tested the effect of preparedness and recall of in‐hospital advice as independent predictors on quit behaviors and whether or not an interaction between preparedness and advice existed. A linear test of trend was also performed on preparedness and advice. All statistical tests were performed using Intercooled Stata 9.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX), with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

From February 2006 through July 2007, 86% (2906/3364) of all cardiology inpatients approached were interviewed. Fifteen percent (436/2906) of patients enrolled in the study indicated that they were current smokers. Contemplation Ladder scores were obtained on 95% (415/436) of the current smokers, and 1‐month postdischarge follow‐up telephone surveys were completed in 67% (276/415) of the current smokers. Three attempts were made to contact patients who were lost to follow‐up (Figure 1). The major reasons for inability to contact patients included wrong telephone numbers, disconnected phone lines, or no method to leave a message for the patient (ie, no answering machine). Given that we were only able to complete follow‐up interviews on 276 patients, we conducted our analyses on only this group of patients.

The average age of current smokers in the sample was 55 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 54‐58). Most current smokers were of the African American race (83%; 224/276). More than 65% of smokers had completed high school or higher, and nearly one‐half (46%) had an average household income of $25,000 or less before taxes. The most common admitting diagnoses per chart audit among current inpatient smokers were AMI (31%) and CHF (27%). The vast majority (95%) of hospitalized smokers in this sample were first‐time admissions to the University of Chicago. Table 1 shows the demographic data for current smokers compared to former smokers (those who have quit smoking prior to admission). Current smokers were more likely to be African American, had lower income levels, and were less likely to have completed high school. Additionally, current smokers were more likely to carry a potential diagnosis of AMI or CHF and to be a first‐time admission (Table 1).

| Demographic Variables | Current Smokers (n = 276)* | Nonsmoker (n = 1329)* | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Male sex | 156 (57) | 705 (53) | 0.22 |

| African American race | 224 (83) | 886 (67) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 55.3 | 64.0 | <0.001 |

| Highest completed level of education | 0.02 | ||

| Junior high school or less | 15 (6) | 98 (7) | |

| Some high school | 67 (25) | 230 (17) | |

| High school graduate | 81 (30) | 403 (31) | |

| Some college education | 68 (25) | 313 (24) | |

| College graduate | 19 (7) | 135 (10) | |

| Graduate level education | 11 (4) | 96 (7) | |

| Household income before taxes | 0.001 | ||

| <$2500 | 33 (12) | 79 (6) | |

| $2501‐$15,000 | 66 (24) | 334 (26) | |

| $15,001‐$50,000 | 51 (19) | 311 (24) | |

| 50,001‐$100,000 | 22 (8) | 126 (9) | |

| >$100,001 | 11 (4) | 50 (4) | |

| Did not answer | 88 (33) | 422 (32) | |

| Diagnosis on admission | 0.02 | ||

| AMI | 66 (31) | 269 (24) | |

| CHF | 58 (27) | 287 (25) | |

| Both | 49 (23) | 273 (24) | |

| Neither | 42 (19) | 305 (27) | |

| Admission status | |||

| New admission | 258 (95) | 1,154 (87) | 0.051 |

| Readmission | 14 (5) | 175 (13) | |

Approximately three‐quarters (76%; 210/276) of current smokers were identified as prepared to quit, with a Ladder score 6. There was a wide distribution of Ladder scores, with one‐third (31%; 86/276) of smokers reporting a Ladder score of 8, indicating that they still smoke, but are ready to set a quit date and another 34% (95/276 patients) with Ladder scores of either 6 or 7 also indicating they were planning to quit smoking (Figure 2). A significant portion of smokers (71%; 195/276) reported making a quit attempt after discharge, and 38% of smokers (106/276) self‐reported that their quit attempt was successful (ie, no longer smoking at 1 month post discharge). Note that the quit rate is reduced to 26% (106/415) at 1 month if one conservatively assumes that those who did not take part in follow‐up were relapsers. Among those who did participate in follow‐up, as shown in Figure 3, the most frequently reported (53%; 145/276) method used to quit smoking was cold turkey. Thirteen percent (37/276) of patients reported making a quit attempt using pharmacological therapy (ie, NRT or bupropion) and only 4% (12/276) of patients reported making a quit attempt using the help of a smoking cessation program (Figure 3).

Preparedness was an important predictor of making a quit attempt. Prepared patients (ie, Ladder score 6) were significantly more likely than patients who were less prepared to report making a quit attempt after discharge (163/212 [77%] vs. 32/64 [50%], respectively; P < 0.001). This result remained significant after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics with a similar effect size (adjusted estimates 76% [95% CI, 75.7‐76.7] prepared vs. 49% [95% CI, 48.5‐49.8]; P < 0.001). These results also remained significant with a similar effect size in analyses using multivariate logistic regression (Table 2). Of those patients who made quit attempts, prepared patients were slightly more likely to report a successful quit attempt (90/163; 55%) than were less‐prepared patients (16/32; 50%), though this was not significant (P = 0.205).

| Statistical test | Quit Behavior | Prepared % (95% CI) | Unprepared % (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Chi square tests | Any quit attempt made after discharge | 76.9 (71.2‐82.6) | 50.0 (37.8‐62.2) | <0.001 |

| Successful quit attempt at time of follow‐up | 55.0 (45.9‐60.2) | 50.0 (25.4‐58.2) | 0.20 | |

| Multivariate logistic regression* | Any quit attempt made after discharge | 76.2 (75.7‐76.7) | 49.2 (48.5‐49.9) | <0.001 |

In the follow‐up sample, 17% could not remember if they received advice to quit smoking. Among those who were able to recall receiving advice, the majority (78%; 180/230) reported that they received advice from a nurse or physician during hospitalization, compared to 22% who did not recall ever being advised to quit by any healthcare provider during the admission. Patients who reported receiving advice to quit were more likely to report making a quit attempt postdischarge as compared to those that did not recall receiving advice (70% vs. 46%, respectively; P = 0.002). In a multivariate logistic regression, controlling for demographic factors and admitting diagnosis, both preparedness and receipt of in‐hospital advice were independent predictors of making a future quit attempt (odds ratio [OR] = 4.05; 95% CI, 1.91‐8.60; P < 0.001 for preparedness; OR = 3.96; 95% CI, 1.84‐8.54; P < 0.001 for advice). Additionally, there was no significant interaction or synergistic effect between being prepared to quit smoking and receiving in‐hospital advice to quit (OR = 1.24; 95% CI, 0.17‐9.21; P = 0.836) (Figure 4). When analyzing the effects of preparedness and advice on quit attempts, only preparedness to quit remained a significant predictor of a successful quit attempt (OR = 2.93; 95% CI, 1.13‐7.60; P = 0.027 for preparedness; OR = 2.16; 95% CI, 0.85‐5.49; P = 0.10 for advice to quit). As demonstrated in Table 2, a higher percentage of prepared patients made a quit attempt after discharge (76.9% vs. 50%) and had a successful quit attempt and short‐term abstinence (55% prepared patients vs. 50% less prepared patients).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that in a group of hospitalized underserved, and predominantly African American smokers, the majority of patients reported being prepared to quit smoking at the time of hospitalization. Prepared patients were more likely to report making a quit attempt after discharge and more likely to report being successful in their quit attempt than patients who reported being less prepared to quit during their hospitalization. Nevertheless, approximately one‐half of unprepared patients did make a quit attempt 1 month after discharge, demonstrating a desire to quit smoking after hospitalization among this population. However, short‐term success rates in this group were lower than in patients prepared to quit. In addition, preparedness to quit and receipt of in‐hospital advice to quit smoking were both found to be independent predictors of making a quit attempt, with nearly identical ORs; however, only preparedness remained significant after controlling for advice to quit. Last, although the majority of hospitalized cardiac patients were making quit attempts after discharge, most patients reported using the least effective quit methods (ie, cold turkey) rather than more effective and intensive interventions such as counseling in combination with pharmacotherapy.

These findings have important implications for current quality initiatives targeted at promoting smoking cessation among cardiac patients. First, these results highlight the need for evidence‐based methods to be made available to hospitalized smokers who are prepared to quit. Our results are consistent with other studies reporting rare use (5.2%) of NRT in the hospital setting, despite the proven benefit in treating nicotine withdrawal symptoms.17 This is also consistent with data reporting that among nonhospitalized smokers, quitting cold turkey was the most commonly used and least effective cessation method.18 Second, the rate of recall of in‐hospital advice among patients (78%) was generally consistent with those reported to CMS (most recent quarter 95% for AMI and 88% for CHF).19

In addition to receiving advice, preparedness to quit was associated with higher quit attempts, therefore highlighting the importance of assessing level of preparedness in addition to giving advice. The fact that most quit attempts were made using cold turkey and resulted in low short‐term success rates underscores the need to reevaluate the current CMS quality indicator of advice alone for hospitalized smokers. Furthermore, the recently updated 2008 U.S. Public Health guidelines recently recommend, in addition to advice, that all hospitalized smokers be assessed for readiness to change, be assisted in quitting with pharmacotherapy, and be arranged follow‐up for tobacco cessation postdischarge, highlighting the inadequacy of advice alone.4 While it is important to continue to advise all hospitalized smokers to quit, the study findings demonstrate that assessing preparedness may result in targeting more prepared patients with more intensive interventions. Further policy implications include that less prepared patients may need motivational techniques to increase their level of preparedness to quit during hospitalization.

Several limitations are worth mentioning. First, the study included a relatively small sample size drawn from a single urban medical center. The prevalence of current smokers in our sample was 15%, which is lower than many studies looking at cardiology inpatient smokers.3, 20 This limitation of our study may be attributed to the advanced age of the majority of our patients, as compared with other studies, as well as the possibility of socially desirable response bias that many low‐income African American smokers may experience, leaving them less likely to admit to smoking at the time of hospitalization. Second, there was a low follow‐up rate, with 66% of patients undergoing follow‐up postdischarge. While this may raise the concerns of differences between ladder scores in those patients that participated in follow‐up and those that did not, analyses show no significant difference between level of preparedness in these 2 groups (68% prepared in patients who received follow‐up vs. 63% prepared patients in those who did not participate in follow‐up; P = 0.36). Third, follow‐up of quit attempts and receipt of advice were all assessed using self‐report, and, therefore, were limited by lack of verification and lack of assessment for potential recall bias. Fourth, in this pilot study, the follow‐up period was relatively short at 1 month postdischarge. It is likely that rates of successful quit attempts would be lower with longer‐term follow‐up periods, given previous literature demonstrating the difficulty with long‐term abstinence.21 Last, the study was not able to account for potential effects that hospitalization itself may have on preparedness, as patients may be more likely to report being prepared to quit when in the face of a health shock,22 as well as the fact that some patients may demonstrate a socially desirable response bias influenced by hospitalization.

In conclusion, the majority of underserved smokers with cardiac disease reported being prepared to quit smoking and were more likely to self‐report making a quit attempt after discharge. However, the majority of these quit attempts were made via cold turkey, without the support of available evidence‐based methods to quit. It is possible that by directly providing education, access to pharmacotherapy, and counseling options, the utilization rates for more efficacious treatments would increase in cardiac patients who are prepared to quit. While recall of in‐hospital advice was associated with future quit attempts, prepared patients who recalled receiving advice were more likely to make a quit attempt than prepared patients who did not recall receiving advice, as well as unprepared patients. Together, these findings highlight the need to consider a patient's level of preparedness to quit in understanding the success of in‐hospital advice and the importance of making evidence‐based cessation methods available to hospitalized smokers who are prepared to quit. Additionally, identifying patients not prepared to quit may help in providing them with appropriate motivational therapy, to move them along the stages of change, as well as educational information on how to quit once they have decided to do so.

Hospitalization may offer a natural opportunity to screen and advise patients on the advantages of quitting smoking due to a variety of reasons, such as the smoke‐free environment, availability of medical personnel, suitability of tailoring information, and the potential to catch a teachable moment.1, 2 Additionally, a recent meta‐analysis suggested that hospital‐based cessation programs and referrals to cardiac rehabilitation result in significantly higher rates of cessation among discharged smokers.3 In 2008, the U.S. Public Health Service Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence in hospitalized smokers recommended listing smoking status on problem lists, evaluating a smoker's preparedness to quit, providing counseling and medications to treat in‐hospital withdrawal symptoms, and arranging discharge follow‐up to help smokers remain abstinent.4 To promote these practices, the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) has made smoking cessation counseling a quality of care indicator for patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), or pneumonia. This indicator is a critical step in recognizing the importance of smoking cessation counseling in improving mortality and morbidity for these patients.

Despite the importance of promoting smoking cessation among hospitalized patients, few studies have looked at whether or not hospitalized patients are prepared to quit smoking. Ascertaining patients' preparedness to quit smoking is an important first step in understanding a patient's readiness to change their health behaviors because smoking cessation is the culmination of a lengthy process of behavior change.5 Studies of healthy factory workers suggest that smokers who were more prepared to quit smoking had a higher number of previous quit attempts and perceived coworker encouragement.6

Understanding patient preparedness to quit smoking is especially important among African American smokers, who face a disproportionate health burden due to smoking‐related illness. Studies show that African Americans are less likely than other racial groups to engage in formal tobacco cessation interventions and have lower long‐term quit rates, despite a higher desire to quit smoking.5, 79 Understanding preparedness to quit among this particular group of hospitalized patients may be an important first step in identifying those most likely to quit and benefit from tailored, intensive interventions, such as using medications to assist in combination with postdischarge tobacco cessation counseling.

The aim of this study was to characterize the preparedness to quit smoking and to assess quit attempts made, methods used for quitting, and the success of such quit attempts at 1‐month follow‐up in a group comprised of a high proportion of underserved African American hospitalized smokers. In addition, the relationship of hospitalized patients' preparedness to quit and the effect of inpatient advice on the likelihood of subsequent tobacco cessation were examined.

Patients and Methods

The data used for this study were collected for the Cardiology Quality of Care Study, an ongoing prospective study of patients hospitalized on the inpatient cardiology service at the University of Chicago Medical Center. Newly admitted patients were approached by research assistants and consented to the study using a previously described protocol for enrolling hospitalized patients.10 Patients that lacked decisional capacity (score of <17 on the telephone version of the Mini‐Mental Status Exam)11 were excluded. Patients did not receive any scripted intervention during this admission to assist with cessation. The study left cessation counseling and advice to quit up to the discretion of the individual physician caring for the patient in the hospital. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Chicago approved this study.

Inpatient Interview

The inpatient interview is a 60‐item questionnaire taking approximately 15 minutes to administer by trained research assistants. The questionnaire is designed to assess demographic characteristics (race, socioeconomic status, education, sex, and age), smoking habits, and preparedness to quit. Demographics were collected on all consented patients. Seven items focused on cigarette smoking, consistent with questions in the National Health Information Survey.12 Patients were classified as lifetime smokers if they smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. To identify current smokers on admission, patients were asked if they now smoke cigarettes some days or everyday. Additionally, smokers were asked if they had made any quit attempts in the past 12 months.

Patients rated their level of preparedness using a modified version of the Biener Abrams Contemplation Ladder. The Contemplation Ladder is an easily‐administered tool represented by a ladder image of rungs with anchor statements developed as an alternative method to the Prochaska and DiClemente Stages of Change.13 The 10‐point scale ranges from 1 (I enjoy smoking and have decided not to quit smoking for my lifetime; I have no interest in quitting) to 10 (I have quit smoking and will never smoke again.) Tobacco users may rank their current level of motivation to quit. A level of 6 (I definitely plan to quit smoking in the next 6 months) or higher is consistent with preparedness to quit. The Contemplation Ladder was validated by Biener and Abrams6 in a work site study which demonstrated that subjects with higher Ladder scores (score 6) were more likely than those with lower Ladder scores (scores < 6) to participate in awareness activities (eg, educational session) and make a quit attempt in 6 months. This instrument is easier to administer than the more well known Transtheoretical Model of Change, given that it is an ordinal scale with clear steps that may be more user‐friendly for both clinicians and patients.6 In a prior study of emergency room patients, an individual's Ladder score was shown to be significantly associated with a patient's reported intention to quit, number of previous quit attempts, perceived coworker encouragement, and socioeconomic status.14

Admission Diagnoses

Chart audit was performed by trained research assistants at the time of the inpatient interview (within 24 hours of admission) to assess whether patients were admitted with the potential diagnoses of AMI, CHF, neither, or both. All were based on the chart documentation of the patients' clinical presentation. This information was used to assess which CMS Quality Indicators applied to cardiology patients, given that smoking cessation is now a quality indicator for patients with AMI or CHF.

Thirty‐day Follow‐up Telephone Survey

Trained research assistants interviewed patients by telephone at approximately 1 month postdischarge. The follow‐up telephone survey included routine questions concerning follow‐up appointments, readmissions, emergency room visits, and patient satisfaction.15, 10 An additional 5 questions related to smoking cessation were added for this study. Questions were developed using the CMS quality indicators16 or were taken from the National Health Information Survey.12 Patients were asked to self‐report quit attempts made postdischarge, whether or not these quit attempts were associated with success (self‐reported abstinence at the time of follow‐up), and what methods were used to quit (ie, nicotine replacement therapy [NRT], other pharmacotherapy, quit line, pamphlet, counseling group, or cold turkey.) Patients were also asked if they recalled receiving advice to quit during their hospitalization from either a nurse or physician.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize Contemplation Ladder scores and types of quit methods used. Chi square tests were used to assess the effect of preparedness (Ladder score 6) on quit behaviors. The main quit behavior was any self‐reported quit attempt made within 1 month after discharge. Additionally, the relationship between preparedness and making a successful quit attempt (defined as a self‐report of not smoking as a result of this quit attempt in the last month) was examined. Multivariate logistic regression, controlling for demographic characteristics, was performed to test the effect of preparedness on quit behaviors (any quit attempt after discharge, or successful quit attempt). While not a primary aim of this study, the association between recall of in‐hospital advice and quit behaviors after discharge was also examined using chi square tests and multivariate logistic regression models, controlling for the demographic characteristics as above. Models also tested the effect of preparedness and recall of in‐hospital advice as independent predictors on quit behaviors and whether or not an interaction between preparedness and advice existed. A linear test of trend was also performed on preparedness and advice. All statistical tests were performed using Intercooled Stata 9.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX), with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

From February 2006 through July 2007, 86% (2906/3364) of all cardiology inpatients approached were interviewed. Fifteen percent (436/2906) of patients enrolled in the study indicated that they were current smokers. Contemplation Ladder scores were obtained on 95% (415/436) of the current smokers, and 1‐month postdischarge follow‐up telephone surveys were completed in 67% (276/415) of the current smokers. Three attempts were made to contact patients who were lost to follow‐up (Figure 1). The major reasons for inability to contact patients included wrong telephone numbers, disconnected phone lines, or no method to leave a message for the patient (ie, no answering machine). Given that we were only able to complete follow‐up interviews on 276 patients, we conducted our analyses on only this group of patients.

The average age of current smokers in the sample was 55 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 54‐58). Most current smokers were of the African American race (83%; 224/276). More than 65% of smokers had completed high school or higher, and nearly one‐half (46%) had an average household income of $25,000 or less before taxes. The most common admitting diagnoses per chart audit among current inpatient smokers were AMI (31%) and CHF (27%). The vast majority (95%) of hospitalized smokers in this sample were first‐time admissions to the University of Chicago. Table 1 shows the demographic data for current smokers compared to former smokers (those who have quit smoking prior to admission). Current smokers were more likely to be African American, had lower income levels, and were less likely to have completed high school. Additionally, current smokers were more likely to carry a potential diagnosis of AMI or CHF and to be a first‐time admission (Table 1).

| Demographic Variables | Current Smokers (n = 276)* | Nonsmoker (n = 1329)* | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Male sex | 156 (57) | 705 (53) | 0.22 |

| African American race | 224 (83) | 886 (67) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 55.3 | 64.0 | <0.001 |

| Highest completed level of education | 0.02 | ||

| Junior high school or less | 15 (6) | 98 (7) | |

| Some high school | 67 (25) | 230 (17) | |

| High school graduate | 81 (30) | 403 (31) | |

| Some college education | 68 (25) | 313 (24) | |

| College graduate | 19 (7) | 135 (10) | |

| Graduate level education | 11 (4) | 96 (7) | |

| Household income before taxes | 0.001 | ||

| <$2500 | 33 (12) | 79 (6) | |

| $2501‐$15,000 | 66 (24) | 334 (26) | |

| $15,001‐$50,000 | 51 (19) | 311 (24) | |

| 50,001‐$100,000 | 22 (8) | 126 (9) | |

| >$100,001 | 11 (4) | 50 (4) | |

| Did not answer | 88 (33) | 422 (32) | |

| Diagnosis on admission | 0.02 | ||

| AMI | 66 (31) | 269 (24) | |

| CHF | 58 (27) | 287 (25) | |

| Both | 49 (23) | 273 (24) | |

| Neither | 42 (19) | 305 (27) | |

| Admission status | |||

| New admission | 258 (95) | 1,154 (87) | 0.051 |

| Readmission | 14 (5) | 175 (13) | |

Approximately three‐quarters (76%; 210/276) of current smokers were identified as prepared to quit, with a Ladder score 6. There was a wide distribution of Ladder scores, with one‐third (31%; 86/276) of smokers reporting a Ladder score of 8, indicating that they still smoke, but are ready to set a quit date and another 34% (95/276 patients) with Ladder scores of either 6 or 7 also indicating they were planning to quit smoking (Figure 2). A significant portion of smokers (71%; 195/276) reported making a quit attempt after discharge, and 38% of smokers (106/276) self‐reported that their quit attempt was successful (ie, no longer smoking at 1 month post discharge). Note that the quit rate is reduced to 26% (106/415) at 1 month if one conservatively assumes that those who did not take part in follow‐up were relapsers. Among those who did participate in follow‐up, as shown in Figure 3, the most frequently reported (53%; 145/276) method used to quit smoking was cold turkey. Thirteen percent (37/276) of patients reported making a quit attempt using pharmacological therapy (ie, NRT or bupropion) and only 4% (12/276) of patients reported making a quit attempt using the help of a smoking cessation program (Figure 3).

Preparedness was an important predictor of making a quit attempt. Prepared patients (ie, Ladder score 6) were significantly more likely than patients who were less prepared to report making a quit attempt after discharge (163/212 [77%] vs. 32/64 [50%], respectively; P < 0.001). This result remained significant after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics with a similar effect size (adjusted estimates 76% [95% CI, 75.7‐76.7] prepared vs. 49% [95% CI, 48.5‐49.8]; P < 0.001). These results also remained significant with a similar effect size in analyses using multivariate logistic regression (Table 2). Of those patients who made quit attempts, prepared patients were slightly more likely to report a successful quit attempt (90/163; 55%) than were less‐prepared patients (16/32; 50%), though this was not significant (P = 0.205).

| Statistical test | Quit Behavior | Prepared % (95% CI) | Unprepared % (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Chi square tests | Any quit attempt made after discharge | 76.9 (71.2‐82.6) | 50.0 (37.8‐62.2) | <0.001 |

| Successful quit attempt at time of follow‐up | 55.0 (45.9‐60.2) | 50.0 (25.4‐58.2) | 0.20 | |

| Multivariate logistic regression* | Any quit attempt made after discharge | 76.2 (75.7‐76.7) | 49.2 (48.5‐49.9) | <0.001 |

In the follow‐up sample, 17% could not remember if they received advice to quit smoking. Among those who were able to recall receiving advice, the majority (78%; 180/230) reported that they received advice from a nurse or physician during hospitalization, compared to 22% who did not recall ever being advised to quit by any healthcare provider during the admission. Patients who reported receiving advice to quit were more likely to report making a quit attempt postdischarge as compared to those that did not recall receiving advice (70% vs. 46%, respectively; P = 0.002). In a multivariate logistic regression, controlling for demographic factors and admitting diagnosis, both preparedness and receipt of in‐hospital advice were independent predictors of making a future quit attempt (odds ratio [OR] = 4.05; 95% CI, 1.91‐8.60; P < 0.001 for preparedness; OR = 3.96; 95% CI, 1.84‐8.54; P < 0.001 for advice). Additionally, there was no significant interaction or synergistic effect between being prepared to quit smoking and receiving in‐hospital advice to quit (OR = 1.24; 95% CI, 0.17‐9.21; P = 0.836) (Figure 4). When analyzing the effects of preparedness and advice on quit attempts, only preparedness to quit remained a significant predictor of a successful quit attempt (OR = 2.93; 95% CI, 1.13‐7.60; P = 0.027 for preparedness; OR = 2.16; 95% CI, 0.85‐5.49; P = 0.10 for advice to quit). As demonstrated in Table 2, a higher percentage of prepared patients made a quit attempt after discharge (76.9% vs. 50%) and had a successful quit attempt and short‐term abstinence (55% prepared patients vs. 50% less prepared patients).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that in a group of hospitalized underserved, and predominantly African American smokers, the majority of patients reported being prepared to quit smoking at the time of hospitalization. Prepared patients were more likely to report making a quit attempt after discharge and more likely to report being successful in their quit attempt than patients who reported being less prepared to quit during their hospitalization. Nevertheless, approximately one‐half of unprepared patients did make a quit attempt 1 month after discharge, demonstrating a desire to quit smoking after hospitalization among this population. However, short‐term success rates in this group were lower than in patients prepared to quit. In addition, preparedness to quit and receipt of in‐hospital advice to quit smoking were both found to be independent predictors of making a quit attempt, with nearly identical ORs; however, only preparedness remained significant after controlling for advice to quit. Last, although the majority of hospitalized cardiac patients were making quit attempts after discharge, most patients reported using the least effective quit methods (ie, cold turkey) rather than more effective and intensive interventions such as counseling in combination with pharmacotherapy.

These findings have important implications for current quality initiatives targeted at promoting smoking cessation among cardiac patients. First, these results highlight the need for evidence‐based methods to be made available to hospitalized smokers who are prepared to quit. Our results are consistent with other studies reporting rare use (5.2%) of NRT in the hospital setting, despite the proven benefit in treating nicotine withdrawal symptoms.17 This is also consistent with data reporting that among nonhospitalized smokers, quitting cold turkey was the most commonly used and least effective cessation method.18 Second, the rate of recall of in‐hospital advice among patients (78%) was generally consistent with those reported to CMS (most recent quarter 95% for AMI and 88% for CHF).19

In addition to receiving advice, preparedness to quit was associated with higher quit attempts, therefore highlighting the importance of assessing level of preparedness in addition to giving advice. The fact that most quit attempts were made using cold turkey and resulted in low short‐term success rates underscores the need to reevaluate the current CMS quality indicator of advice alone for hospitalized smokers. Furthermore, the recently updated 2008 U.S. Public Health guidelines recently recommend, in addition to advice, that all hospitalized smokers be assessed for readiness to change, be assisted in quitting with pharmacotherapy, and be arranged follow‐up for tobacco cessation postdischarge, highlighting the inadequacy of advice alone.4 While it is important to continue to advise all hospitalized smokers to quit, the study findings demonstrate that assessing preparedness may result in targeting more prepared patients with more intensive interventions. Further policy implications include that less prepared patients may need motivational techniques to increase their level of preparedness to quit during hospitalization.

Several limitations are worth mentioning. First, the study included a relatively small sample size drawn from a single urban medical center. The prevalence of current smokers in our sample was 15%, which is lower than many studies looking at cardiology inpatient smokers.3, 20 This limitation of our study may be attributed to the advanced age of the majority of our patients, as compared with other studies, as well as the possibility of socially desirable response bias that many low‐income African American smokers may experience, leaving them less likely to admit to smoking at the time of hospitalization. Second, there was a low follow‐up rate, with 66% of patients undergoing follow‐up postdischarge. While this may raise the concerns of differences between ladder scores in those patients that participated in follow‐up and those that did not, analyses show no significant difference between level of preparedness in these 2 groups (68% prepared in patients who received follow‐up vs. 63% prepared patients in those who did not participate in follow‐up; P = 0.36). Third, follow‐up of quit attempts and receipt of advice were all assessed using self‐report, and, therefore, were limited by lack of verification and lack of assessment for potential recall bias. Fourth, in this pilot study, the follow‐up period was relatively short at 1 month postdischarge. It is likely that rates of successful quit attempts would be lower with longer‐term follow‐up periods, given previous literature demonstrating the difficulty with long‐term abstinence.21 Last, the study was not able to account for potential effects that hospitalization itself may have on preparedness, as patients may be more likely to report being prepared to quit when in the face of a health shock,22 as well as the fact that some patients may demonstrate a socially desirable response bias influenced by hospitalization.

In conclusion, the majority of underserved smokers with cardiac disease reported being prepared to quit smoking and were more likely to self‐report making a quit attempt after discharge. However, the majority of these quit attempts were made via cold turkey, without the support of available evidence‐based methods to quit. It is possible that by directly providing education, access to pharmacotherapy, and counseling options, the utilization rates for more efficacious treatments would increase in cardiac patients who are prepared to quit. While recall of in‐hospital advice was associated with future quit attempts, prepared patients who recalled receiving advice were more likely to make a quit attempt than prepared patients who did not recall receiving advice, as well as unprepared patients. Together, these findings highlight the need to consider a patient's level of preparedness to quit in understanding the success of in‐hospital advice and the importance of making evidence‐based cessation methods available to hospitalized smokers who are prepared to quit. Additionally, identifying patients not prepared to quit may help in providing them with appropriate motivational therapy, to move them along the stages of change, as well as educational information on how to quit once they have decided to do so.

- ,,.Helping hospitalized smokers quit: new directions for treatment and research.J Consult Clin Psychol.1993;61:778–789.

- ,.Smokers who are hospitalized: a window of opportunity for cessation interventions.Prev Med.1992;21:262–269.

- ,,, et al.Predictors of smoking cessation after a myocardial infarction: the role of institutional smoking cessation programs in improving success.Arch Intern Med.2008;168(18):1961–1967.

- Guideline Panel.Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence.Washington, DC:Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services;2008.

- ,.Stages and processes of self‐change in smoking: toward an integrative model of change.J Consult Clin Psychol.1983;51:390–395.

- ,.The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation.Health Psychol.1991;10(5):360–365.

- ,,,,.Smoking cessation factors among African Americans and Whites.Am J Public Health.1993;83(2):220–226.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation.Rockville, MD:Office on Smoking and Health, Centers for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Public Health Service,U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,Washington, DC;2000.

- ,,,,.Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. the changing influence of gender and race.JAMA.1989;261(1):49–55.

- ,,, et al.Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists.Ann Intern Med.2002;137(11):866–874.

- ,,,.Validation of a telephone version of the Mini‐Mental State Examination.J Am Geriatr Soc.1992;40(7):697–702.

- National Health Information Survey Questionnaire, Sample Adult,Adult Health Behaviors;2004.

- ,,, et al.The Marijuana Ladder: measuring motivation to change marijuana use in incarcerated adolescents.Drug Alcohol Depend.2006;83:42–48.

- ,,,,.Motivation for stopping tobacco use among emergency department patients.Acad Emerg Med.2005;12:568–571.

- Picker‐Commonwealth Survey of Patient‐Centered Care.Health Aff.1991.

- Hospital Quality Initiatives. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HospitalQualtiyInits. Accessed April2009.

- ,,, et al.The use of nicotine replacement therapy by hospitalized smokers.Am J Prev Med.1999;17(4):255–259.

- ,,,,.Methods used to quit smoking in the United States: do cessation programs help?JAMA.1990;263(20):2795–2796.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.Hospital Compare.2006 Data Graphs. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Accessed April2009.

- ,,, et al.Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2006.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2007;56:1157–1161.

- ,,.Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers.Arch Intern Med.2008;168(18):1950–1960.

- ,.Health beliefs and smoking patterns in heart patients and their wives: a longitudinal study.Am J Public Health.1977;67:921–930.

- ,,.Helping hospitalized smokers quit: new directions for treatment and research.J Consult Clin Psychol.1993;61:778–789.

- ,.Smokers who are hospitalized: a window of opportunity for cessation interventions.Prev Med.1992;21:262–269.

- ,,, et al.Predictors of smoking cessation after a myocardial infarction: the role of institutional smoking cessation programs in improving success.Arch Intern Med.2008;168(18):1961–1967.

- Guideline Panel.Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence.Washington, DC:Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services;2008.

- ,.Stages and processes of self‐change in smoking: toward an integrative model of change.J Consult Clin Psychol.1983;51:390–395.

- ,.The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation.Health Psychol.1991;10(5):360–365.

- ,,,,.Smoking cessation factors among African Americans and Whites.Am J Public Health.1993;83(2):220–226.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation.Rockville, MD:Office on Smoking and Health, Centers for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Public Health Service,U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,Washington, DC;2000.

- ,,,,.Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. the changing influence of gender and race.JAMA.1989;261(1):49–55.

- ,,, et al.Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists.Ann Intern Med.2002;137(11):866–874.

- ,,,.Validation of a telephone version of the Mini‐Mental State Examination.J Am Geriatr Soc.1992;40(7):697–702.

- National Health Information Survey Questionnaire, Sample Adult,Adult Health Behaviors;2004.

- ,,, et al.The Marijuana Ladder: measuring motivation to change marijuana use in incarcerated adolescents.Drug Alcohol Depend.2006;83:42–48.

- ,,,,.Motivation for stopping tobacco use among emergency department patients.Acad Emerg Med.2005;12:568–571.

- Picker‐Commonwealth Survey of Patient‐Centered Care.Health Aff.1991.

- Hospital Quality Initiatives. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HospitalQualtiyInits. Accessed April2009.

- ,,, et al.The use of nicotine replacement therapy by hospitalized smokers.Am J Prev Med.1999;17(4):255–259.

- ,,,,.Methods used to quit smoking in the United States: do cessation programs help?JAMA.1990;263(20):2795–2796.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.Hospital Compare.2006 Data Graphs. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Accessed April2009.

- ,,, et al.Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2006.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2007;56:1157–1161.

- ,,.Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers.Arch Intern Med.2008;168(18):1950–1960.

- ,.Health beliefs and smoking patterns in heart patients and their wives: a longitudinal study.Am J Public Health.1977;67:921–930.

Copyright © 2010 Society of Hospital Medicine

Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient

A crucial arena of innovative educational programs for the care of the elderly must include the hospital setting, a place of great cost, morbidity, and mortality for a population currently occupying approximately half of US hospital beds.1 With a marked acceleration in the number of persons living to an advanced age, there is a clear imperative to address the health‐care needs of the elderly, particularly the complex and frail.24 An educational grounding that steps beyond the traditional organ‐based models of disease to a much broader patient‐centered framework of care is necessary to aid physicians in advanced clinical decision‐making in the care of older patients. Organizing the medical care of the older patient within existing systems of care and a team care management network must also be improved.