User login

The Changing Landscape of Orthopedic Practice: Challenges and Opportunities

Orthopedic surgery is going through a time of remarkable change. Health care reform, heightened public scrutiny, shifting population demographics, increased reliance on the Internet for information, ongoing metamorphosis of our profession into a business, and lack of consistent high-quality clinical evidence have created a new frontier of challenges and opportunities. At heart are the needs to deliver high-quality education that is in line with new technological media, to reclaim our ability to guide musculoskeletal care at the policymaking level, to fortify our long-held tradition of ethical responsibility, to invest in research and the training of physician-scientists, to maintain unity among the different subspecialties, and to increase female and minority representation. Never before has understanding and applying the key tenets of our philosophy as orthopedic surgeons been more crucial.

The changing landscape of orthopedic practice has been an unsettling topic in many of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) presidential addresses in recent years.1-11 What are the challenges and what can we learn moving forward? In this article, we seek to answer these questions by drawing insights from the combined experience and wisdom of past AAOS presidents since the turn of the 21st century.

Education

Education is the cornerstone of providing quality musculoskeletal care12 and staying up to date with technological advances.13 The modes of education delivery, however, have changed. No longer is orthopedic education confined to tangible textbooks and journal articles, nor is it limited to those of us in the profession. Instead, orthopedic education has shifted toward online learning14 and is available to patients and nonorthopedic providers.12 With more patients gaining access to rapidly growing online resources, a unique challenge has arisen: an abundance of data with variable quality of evidence influencing the decision-making process. This has created what Richard Kyle15 described as the “trap of the new technology war,” where patient misinformation and direct-to-consumer marketing can lead to dangerous musculoskeletal care delivery, including unrealistic patient expectations.3 To compound the problem, our ability to provide orthopedic education in formats compatible with the new learning mediums has not been up to the demand, with issues of cost, accessibility, and efficacy plaguing the current process.3,5 Also, we have yet to unlock the benefits of surgical simulation, which has the potential to provide more effective training at no risk to the patient.4,13 By adapting to the new learning formats, we can provide numerous new opportunities for keeping up to date on evolving practice management principles, which, with added accessibility, will be used more often by orthopedic surgeons and the public.13

Research

Research is vital for quality improvement and the continuation of excellence.5 It is only with research that we can provide groundbreaking advances and measure the outcomes of our interventions.2 Unfortunately, orthopedic research funding continues to be disproportionately low, especially given that musculoskeletal ailments are the leading cause of both physician visits and chronic impairment in the United States.2 For example, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases receives only 10% of what our country spends on cancer research and 15% of what is spent on heart- and lung-disease research.2 To compound the problem of limited funding, the number of physician-scientists has been dropping at an alarming rate.2 As a result, we must not only refocus our research efforts so that they are efficient and effective, but we must also invest in the training of orthopedic physician-scientists to ensure a continuous stream of groundbreaking discoveries. We owe it to our patients to provide them with proven, effective, and high-quality care.

Industry Relationships

Local and national attention will continue to focus on our relationships with industry. The challenge is twofold: mitigating the negative portrayal of industry relationships and navigating the changes applied to industry funding for research and education.9 Our collaboration with industry is important for the development and advancement of orthopedics,15 but it must be guided by the professional and ethical guidelines established by the AAOS, ensuring that the best interest of patients remains a top priority.8,15 We must maintain the public’s trust by using every opportunity to convey our lone goal in collaborating with industry, ie, improving patient care.9 According to James Beaty,7 any relationship with industry should be “so ethical that it could be printed on the front page of the newspaper and we could face our neighbors with our heads held high.”

Gender and Minority Representation

The racial and ethnic makeup of the United States is undergoing a rapid change. Over the next 4 decades, the white population is projected to become the minority, while women will continue to outnumber men.16 Despite the rapidly changing demographics of the United States, health care disparities persist. As of 2011, minorities and women made up only 22.55% and 14.52%, respectively, of all orthopedic surgery residents.17 This limited diversity in orthopedic training programs is alarming and may lead to suboptimal physician–patient relationships, because patients tend to be more comfortable with and respond better to the care provided by physicians of similar background.3 In addition, if we do not integrate women into orthopedics, the number of female medical students applying to orthopedic residency programs might decline.3

Equating excellent medical care with diversity and cultural competence requires that we bridge the gap that has prevented patients from obtaining high-quality care.8 To achieve this goal, we need to continue recruiting orthopedic surgeons from all segments of our population. Ultimately, health care disparities can be effectively reduced through the delivery of culturally competent care.8

Physician–Patient Relationship

Medical liability has resulted in the development of damaging attitudes among physicians, with many viewing patients as potential adversaries and even avoiding high-risk procedures altogether.6 This deterioration of the physician–patient relationship has been another troubling consequence of managed care that emphasizes quantity and speed.1 As a result, we are perceived by the public as impersonal, poor listeners, and difficult to see on short notice.1

The poor perception of orthopedic surgeons by the general public is not acceptable for a field that places such a high value on excellence. Patient-centered care is at the core of quality improvement, and improving patient relationships starts and ends with us and with each patient we treat.6 In a health care environment in which the average orthopedic surgeon cares for thousands of patients each year, we must make certain to use each opportunity to engage our patients and enhance our relationships with them.6 The basic necessities of patient-centered care include empowerment of the patient through education, better communication, and transparency; providing accurate and evidence-based information; and cooperation among physicians.3,6 The benefits of improving personal relationships with patients are multifold and could have lasting positive effects: increased physician and patient satisfaction, better patient compliance, greater practice efficiency, and fewer malpractice lawsuits.1 We can also benefit from mobilizing a greater constituency to advocate alongside us.6

Unity

Despite accounting for less than 3% of all physicians, orthopedic surgeons have assumed an influential voice in the field of medicine.13 This is attributed not only to the success of our interventions but, more importantly, to the fact that we have “stuck together.”13 The concept of “sticking together” may seem a cliché and facile but will certainly be a pressing need as we move ahead. We draw strength from the breadth and diversity of our subspecialties, but this strength may become a weakness if we do not join in promoting the betterment of our profession as a whole.14 To avoid duplications and bring synergy to all our efforts, we should continue to develop new partnerships in our specialty societies6 and speak with one voice to our patients and to the public.15 Joshua Jacobs11 reminds us of the warning Benjamin Franklin imparted to the signers of the Declaration of Independence, “We must hang together, or most assuredly, we will all hang separately.” To ensure the continued strength of the house of orthopedics, we must live by this tenet.

Advocacy

The federal government has become increasingly involved in regulating the practice of medicine.9 Orthopedic surgery has been hit especially hard, because the cost of implants and continued innovation has fueled the belief that our profession is a major contributor to unsustainable health care costs.11 We now face multiple legislative regulations related to physician reimbursement, ownership, self-referral, medical liability, and mandates of the Affordable Care Act.9 As a result, there has been a decreasing role for orthopedic surgeons as independent practitioners, with more orthopedists forgoing physician-owned practices for large hospital corporations. We are also in increasing competition for limited resources.10 This is compounded by the fact that those regulating health care, paying for health care, and allocating research funding fail to comprehend the high societal needs for treatment of musculoskeletal diseases and injuries,6 which will only increase in the coming decades.14

The aforementioned challenges make our involvement at all levels of the political process more necessary than ever before.5,9 E. Anthony Rankin8 reminds us, “As physicians, we cannot in good conscience allow our patients’ access to quality orthopedic care to be determined solely by the government, the insurance companies, the trial lawyers, or others…. Either we will have a voice in defining the future of health care, or it will be defined by others for us.” Our advocacy approach, however, should be very careful. Joshua Jacobs11 cautions that “we will be most effective if our advocacy message is presented as a potential solution to the current health care crisis, not just as a demand for fair reimbursement.” Instead, we can achieve this goal with what Richard Gelberman2 summarized as “doing what we do best: accumulating knowledge, positioning ourselves as the authorities that we are, and using what we learn to advocate for better patient care and research.”

Value Medicine

Orthopedic surgeons are now expected to provide not just high-quality care but low-cost care. In line with the emerging emphasis on value, sharp focus has been placed on the assessment of physician performance and treatment outcomes as quality-of-care measures.6 But how have we measured the quality of the care we provide? We have not, or, at least, we have not had valid or reliable means of doing so.6 Gone are the days of telling the world of the excellence of our profession in the treatment of musculoskeletal disease. We now must prove to our patients, the government, and payers that what we do works.12,13 If we fail to communicate the cost effectiveness of our interventions, our new knowledge and technologies will not be accepted or funded.10 We should, however, not be discouraged by the new “value equation,” but use it as an incentive to provide evidence-based care and to improve the efficiency of resource utilization.14 Today, we are urged to be leaders in quality improvement, both in our individual orthopedic practices and as a profession.10,12,13

Conclusion

Meeting increasingly higher demands for musculoskeletal care in an evolving medical landscape will bring a new set of challenges that will be more frequent and more intense than those in the past.14 Today, we are tasked with providing fiscally efficient, culturally competent, high-quality, evidence-based, and compassionate care. We are also tasked with reclaiming our ability to shape the future of our profession at the policymaking level. In doing so, the need for unity, advocacy, commitment to education and research, women and minority representation, and open communication with the public has never been more relevant. As we continue to advance as a profession, we must resist the temptation to look back in defiance of change but move forward, confident in our ability to evolve. ◾

1. Canale ST. The orthopaedic forum. Falling in love again. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(5):739-742.

2. Gelberman RH. The Academy on the edge: taking charge of our future. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(6):946-950.

3. Tolo VT. The challenges of change: is orthopaedics ready? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(9):1707-1713.

4. Herndon JH. One more turn of the wrench. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(10):2036-2048.

5. Bucholz RW. Knowledge is our business. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(7):1575-1578.

6. Weinstein SL. Nothing about you...without you. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1648-1652.

7. Beaty JH. Presidential address: “Building the best . . . Lifelong learning”. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(9):515-518.

8. Rankin EA. Presidential Address: advocacy now... for our patients and our profession. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(6):303-305.

9. Zuckerman JD. Silk purses, sows’ ears, and heap ash—turning challenges into opportunities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(5):271-275.

10. Tongue JR. Strong on vision, flexible on details. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(4):187-189.

11. Jacobs JJ. Moving forward: from curses to blessings. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(5):261-265.

12. Callaghan JJ. Quality of care: getting from good to great. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;8(9):516-519.

13. Berry DJ. Informed by our past, building our future. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(4):187-190.

14. Azar FM. Building a bigger box. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(6):341-345.

15. Kyle RF. Presidential Address: Together we are one. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(5):261-264.

16. Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The Next Four Decades: The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Washington, DC: Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau, US Dept of Commerce; 2010.

17. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Department of Research and Scientific Affairs. 1998-2011 Resident Diversity Survey Report. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www3.aaos.org/about/diversity/pdfs/resident_trend.pdf. Published March 9, 2012. Accessed October 26, 2015.

Orthopedic surgery is going through a time of remarkable change. Health care reform, heightened public scrutiny, shifting population demographics, increased reliance on the Internet for information, ongoing metamorphosis of our profession into a business, and lack of consistent high-quality clinical evidence have created a new frontier of challenges and opportunities. At heart are the needs to deliver high-quality education that is in line with new technological media, to reclaim our ability to guide musculoskeletal care at the policymaking level, to fortify our long-held tradition of ethical responsibility, to invest in research and the training of physician-scientists, to maintain unity among the different subspecialties, and to increase female and minority representation. Never before has understanding and applying the key tenets of our philosophy as orthopedic surgeons been more crucial.

The changing landscape of orthopedic practice has been an unsettling topic in many of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) presidential addresses in recent years.1-11 What are the challenges and what can we learn moving forward? In this article, we seek to answer these questions by drawing insights from the combined experience and wisdom of past AAOS presidents since the turn of the 21st century.

Education

Education is the cornerstone of providing quality musculoskeletal care12 and staying up to date with technological advances.13 The modes of education delivery, however, have changed. No longer is orthopedic education confined to tangible textbooks and journal articles, nor is it limited to those of us in the profession. Instead, orthopedic education has shifted toward online learning14 and is available to patients and nonorthopedic providers.12 With more patients gaining access to rapidly growing online resources, a unique challenge has arisen: an abundance of data with variable quality of evidence influencing the decision-making process. This has created what Richard Kyle15 described as the “trap of the new technology war,” where patient misinformation and direct-to-consumer marketing can lead to dangerous musculoskeletal care delivery, including unrealistic patient expectations.3 To compound the problem, our ability to provide orthopedic education in formats compatible with the new learning mediums has not been up to the demand, with issues of cost, accessibility, and efficacy plaguing the current process.3,5 Also, we have yet to unlock the benefits of surgical simulation, which has the potential to provide more effective training at no risk to the patient.4,13 By adapting to the new learning formats, we can provide numerous new opportunities for keeping up to date on evolving practice management principles, which, with added accessibility, will be used more often by orthopedic surgeons and the public.13

Research

Research is vital for quality improvement and the continuation of excellence.5 It is only with research that we can provide groundbreaking advances and measure the outcomes of our interventions.2 Unfortunately, orthopedic research funding continues to be disproportionately low, especially given that musculoskeletal ailments are the leading cause of both physician visits and chronic impairment in the United States.2 For example, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases receives only 10% of what our country spends on cancer research and 15% of what is spent on heart- and lung-disease research.2 To compound the problem of limited funding, the number of physician-scientists has been dropping at an alarming rate.2 As a result, we must not only refocus our research efforts so that they are efficient and effective, but we must also invest in the training of orthopedic physician-scientists to ensure a continuous stream of groundbreaking discoveries. We owe it to our patients to provide them with proven, effective, and high-quality care.

Industry Relationships

Local and national attention will continue to focus on our relationships with industry. The challenge is twofold: mitigating the negative portrayal of industry relationships and navigating the changes applied to industry funding for research and education.9 Our collaboration with industry is important for the development and advancement of orthopedics,15 but it must be guided by the professional and ethical guidelines established by the AAOS, ensuring that the best interest of patients remains a top priority.8,15 We must maintain the public’s trust by using every opportunity to convey our lone goal in collaborating with industry, ie, improving patient care.9 According to James Beaty,7 any relationship with industry should be “so ethical that it could be printed on the front page of the newspaper and we could face our neighbors with our heads held high.”

Gender and Minority Representation

The racial and ethnic makeup of the United States is undergoing a rapid change. Over the next 4 decades, the white population is projected to become the minority, while women will continue to outnumber men.16 Despite the rapidly changing demographics of the United States, health care disparities persist. As of 2011, minorities and women made up only 22.55% and 14.52%, respectively, of all orthopedic surgery residents.17 This limited diversity in orthopedic training programs is alarming and may lead to suboptimal physician–patient relationships, because patients tend to be more comfortable with and respond better to the care provided by physicians of similar background.3 In addition, if we do not integrate women into orthopedics, the number of female medical students applying to orthopedic residency programs might decline.3

Equating excellent medical care with diversity and cultural competence requires that we bridge the gap that has prevented patients from obtaining high-quality care.8 To achieve this goal, we need to continue recruiting orthopedic surgeons from all segments of our population. Ultimately, health care disparities can be effectively reduced through the delivery of culturally competent care.8

Physician–Patient Relationship

Medical liability has resulted in the development of damaging attitudes among physicians, with many viewing patients as potential adversaries and even avoiding high-risk procedures altogether.6 This deterioration of the physician–patient relationship has been another troubling consequence of managed care that emphasizes quantity and speed.1 As a result, we are perceived by the public as impersonal, poor listeners, and difficult to see on short notice.1

The poor perception of orthopedic surgeons by the general public is not acceptable for a field that places such a high value on excellence. Patient-centered care is at the core of quality improvement, and improving patient relationships starts and ends with us and with each patient we treat.6 In a health care environment in which the average orthopedic surgeon cares for thousands of patients each year, we must make certain to use each opportunity to engage our patients and enhance our relationships with them.6 The basic necessities of patient-centered care include empowerment of the patient through education, better communication, and transparency; providing accurate and evidence-based information; and cooperation among physicians.3,6 The benefits of improving personal relationships with patients are multifold and could have lasting positive effects: increased physician and patient satisfaction, better patient compliance, greater practice efficiency, and fewer malpractice lawsuits.1 We can also benefit from mobilizing a greater constituency to advocate alongside us.6

Unity

Despite accounting for less than 3% of all physicians, orthopedic surgeons have assumed an influential voice in the field of medicine.13 This is attributed not only to the success of our interventions but, more importantly, to the fact that we have “stuck together.”13 The concept of “sticking together” may seem a cliché and facile but will certainly be a pressing need as we move ahead. We draw strength from the breadth and diversity of our subspecialties, but this strength may become a weakness if we do not join in promoting the betterment of our profession as a whole.14 To avoid duplications and bring synergy to all our efforts, we should continue to develop new partnerships in our specialty societies6 and speak with one voice to our patients and to the public.15 Joshua Jacobs11 reminds us of the warning Benjamin Franklin imparted to the signers of the Declaration of Independence, “We must hang together, or most assuredly, we will all hang separately.” To ensure the continued strength of the house of orthopedics, we must live by this tenet.

Advocacy

The federal government has become increasingly involved in regulating the practice of medicine.9 Orthopedic surgery has been hit especially hard, because the cost of implants and continued innovation has fueled the belief that our profession is a major contributor to unsustainable health care costs.11 We now face multiple legislative regulations related to physician reimbursement, ownership, self-referral, medical liability, and mandates of the Affordable Care Act.9 As a result, there has been a decreasing role for orthopedic surgeons as independent practitioners, with more orthopedists forgoing physician-owned practices for large hospital corporations. We are also in increasing competition for limited resources.10 This is compounded by the fact that those regulating health care, paying for health care, and allocating research funding fail to comprehend the high societal needs for treatment of musculoskeletal diseases and injuries,6 which will only increase in the coming decades.14

The aforementioned challenges make our involvement at all levels of the political process more necessary than ever before.5,9 E. Anthony Rankin8 reminds us, “As physicians, we cannot in good conscience allow our patients’ access to quality orthopedic care to be determined solely by the government, the insurance companies, the trial lawyers, or others…. Either we will have a voice in defining the future of health care, or it will be defined by others for us.” Our advocacy approach, however, should be very careful. Joshua Jacobs11 cautions that “we will be most effective if our advocacy message is presented as a potential solution to the current health care crisis, not just as a demand for fair reimbursement.” Instead, we can achieve this goal with what Richard Gelberman2 summarized as “doing what we do best: accumulating knowledge, positioning ourselves as the authorities that we are, and using what we learn to advocate for better patient care and research.”

Value Medicine

Orthopedic surgeons are now expected to provide not just high-quality care but low-cost care. In line with the emerging emphasis on value, sharp focus has been placed on the assessment of physician performance and treatment outcomes as quality-of-care measures.6 But how have we measured the quality of the care we provide? We have not, or, at least, we have not had valid or reliable means of doing so.6 Gone are the days of telling the world of the excellence of our profession in the treatment of musculoskeletal disease. We now must prove to our patients, the government, and payers that what we do works.12,13 If we fail to communicate the cost effectiveness of our interventions, our new knowledge and technologies will not be accepted or funded.10 We should, however, not be discouraged by the new “value equation,” but use it as an incentive to provide evidence-based care and to improve the efficiency of resource utilization.14 Today, we are urged to be leaders in quality improvement, both in our individual orthopedic practices and as a profession.10,12,13

Conclusion

Meeting increasingly higher demands for musculoskeletal care in an evolving medical landscape will bring a new set of challenges that will be more frequent and more intense than those in the past.14 Today, we are tasked with providing fiscally efficient, culturally competent, high-quality, evidence-based, and compassionate care. We are also tasked with reclaiming our ability to shape the future of our profession at the policymaking level. In doing so, the need for unity, advocacy, commitment to education and research, women and minority representation, and open communication with the public has never been more relevant. As we continue to advance as a profession, we must resist the temptation to look back in defiance of change but move forward, confident in our ability to evolve. ◾

Orthopedic surgery is going through a time of remarkable change. Health care reform, heightened public scrutiny, shifting population demographics, increased reliance on the Internet for information, ongoing metamorphosis of our profession into a business, and lack of consistent high-quality clinical evidence have created a new frontier of challenges and opportunities. At heart are the needs to deliver high-quality education that is in line with new technological media, to reclaim our ability to guide musculoskeletal care at the policymaking level, to fortify our long-held tradition of ethical responsibility, to invest in research and the training of physician-scientists, to maintain unity among the different subspecialties, and to increase female and minority representation. Never before has understanding and applying the key tenets of our philosophy as orthopedic surgeons been more crucial.

The changing landscape of orthopedic practice has been an unsettling topic in many of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) presidential addresses in recent years.1-11 What are the challenges and what can we learn moving forward? In this article, we seek to answer these questions by drawing insights from the combined experience and wisdom of past AAOS presidents since the turn of the 21st century.

Education

Education is the cornerstone of providing quality musculoskeletal care12 and staying up to date with technological advances.13 The modes of education delivery, however, have changed. No longer is orthopedic education confined to tangible textbooks and journal articles, nor is it limited to those of us in the profession. Instead, orthopedic education has shifted toward online learning14 and is available to patients and nonorthopedic providers.12 With more patients gaining access to rapidly growing online resources, a unique challenge has arisen: an abundance of data with variable quality of evidence influencing the decision-making process. This has created what Richard Kyle15 described as the “trap of the new technology war,” where patient misinformation and direct-to-consumer marketing can lead to dangerous musculoskeletal care delivery, including unrealistic patient expectations.3 To compound the problem, our ability to provide orthopedic education in formats compatible with the new learning mediums has not been up to the demand, with issues of cost, accessibility, and efficacy plaguing the current process.3,5 Also, we have yet to unlock the benefits of surgical simulation, which has the potential to provide more effective training at no risk to the patient.4,13 By adapting to the new learning formats, we can provide numerous new opportunities for keeping up to date on evolving practice management principles, which, with added accessibility, will be used more often by orthopedic surgeons and the public.13

Research

Research is vital for quality improvement and the continuation of excellence.5 It is only with research that we can provide groundbreaking advances and measure the outcomes of our interventions.2 Unfortunately, orthopedic research funding continues to be disproportionately low, especially given that musculoskeletal ailments are the leading cause of both physician visits and chronic impairment in the United States.2 For example, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases receives only 10% of what our country spends on cancer research and 15% of what is spent on heart- and lung-disease research.2 To compound the problem of limited funding, the number of physician-scientists has been dropping at an alarming rate.2 As a result, we must not only refocus our research efforts so that they are efficient and effective, but we must also invest in the training of orthopedic physician-scientists to ensure a continuous stream of groundbreaking discoveries. We owe it to our patients to provide them with proven, effective, and high-quality care.

Industry Relationships

Local and national attention will continue to focus on our relationships with industry. The challenge is twofold: mitigating the negative portrayal of industry relationships and navigating the changes applied to industry funding for research and education.9 Our collaboration with industry is important for the development and advancement of orthopedics,15 but it must be guided by the professional and ethical guidelines established by the AAOS, ensuring that the best interest of patients remains a top priority.8,15 We must maintain the public’s trust by using every opportunity to convey our lone goal in collaborating with industry, ie, improving patient care.9 According to James Beaty,7 any relationship with industry should be “so ethical that it could be printed on the front page of the newspaper and we could face our neighbors with our heads held high.”

Gender and Minority Representation

The racial and ethnic makeup of the United States is undergoing a rapid change. Over the next 4 decades, the white population is projected to become the minority, while women will continue to outnumber men.16 Despite the rapidly changing demographics of the United States, health care disparities persist. As of 2011, minorities and women made up only 22.55% and 14.52%, respectively, of all orthopedic surgery residents.17 This limited diversity in orthopedic training programs is alarming and may lead to suboptimal physician–patient relationships, because patients tend to be more comfortable with and respond better to the care provided by physicians of similar background.3 In addition, if we do not integrate women into orthopedics, the number of female medical students applying to orthopedic residency programs might decline.3

Equating excellent medical care with diversity and cultural competence requires that we bridge the gap that has prevented patients from obtaining high-quality care.8 To achieve this goal, we need to continue recruiting orthopedic surgeons from all segments of our population. Ultimately, health care disparities can be effectively reduced through the delivery of culturally competent care.8

Physician–Patient Relationship

Medical liability has resulted in the development of damaging attitudes among physicians, with many viewing patients as potential adversaries and even avoiding high-risk procedures altogether.6 This deterioration of the physician–patient relationship has been another troubling consequence of managed care that emphasizes quantity and speed.1 As a result, we are perceived by the public as impersonal, poor listeners, and difficult to see on short notice.1

The poor perception of orthopedic surgeons by the general public is not acceptable for a field that places such a high value on excellence. Patient-centered care is at the core of quality improvement, and improving patient relationships starts and ends with us and with each patient we treat.6 In a health care environment in which the average orthopedic surgeon cares for thousands of patients each year, we must make certain to use each opportunity to engage our patients and enhance our relationships with them.6 The basic necessities of patient-centered care include empowerment of the patient through education, better communication, and transparency; providing accurate and evidence-based information; and cooperation among physicians.3,6 The benefits of improving personal relationships with patients are multifold and could have lasting positive effects: increased physician and patient satisfaction, better patient compliance, greater practice efficiency, and fewer malpractice lawsuits.1 We can also benefit from mobilizing a greater constituency to advocate alongside us.6

Unity

Despite accounting for less than 3% of all physicians, orthopedic surgeons have assumed an influential voice in the field of medicine.13 This is attributed not only to the success of our interventions but, more importantly, to the fact that we have “stuck together.”13 The concept of “sticking together” may seem a cliché and facile but will certainly be a pressing need as we move ahead. We draw strength from the breadth and diversity of our subspecialties, but this strength may become a weakness if we do not join in promoting the betterment of our profession as a whole.14 To avoid duplications and bring synergy to all our efforts, we should continue to develop new partnerships in our specialty societies6 and speak with one voice to our patients and to the public.15 Joshua Jacobs11 reminds us of the warning Benjamin Franklin imparted to the signers of the Declaration of Independence, “We must hang together, or most assuredly, we will all hang separately.” To ensure the continued strength of the house of orthopedics, we must live by this tenet.

Advocacy

The federal government has become increasingly involved in regulating the practice of medicine.9 Orthopedic surgery has been hit especially hard, because the cost of implants and continued innovation has fueled the belief that our profession is a major contributor to unsustainable health care costs.11 We now face multiple legislative regulations related to physician reimbursement, ownership, self-referral, medical liability, and mandates of the Affordable Care Act.9 As a result, there has been a decreasing role for orthopedic surgeons as independent practitioners, with more orthopedists forgoing physician-owned practices for large hospital corporations. We are also in increasing competition for limited resources.10 This is compounded by the fact that those regulating health care, paying for health care, and allocating research funding fail to comprehend the high societal needs for treatment of musculoskeletal diseases and injuries,6 which will only increase in the coming decades.14

The aforementioned challenges make our involvement at all levels of the political process more necessary than ever before.5,9 E. Anthony Rankin8 reminds us, “As physicians, we cannot in good conscience allow our patients’ access to quality orthopedic care to be determined solely by the government, the insurance companies, the trial lawyers, or others…. Either we will have a voice in defining the future of health care, or it will be defined by others for us.” Our advocacy approach, however, should be very careful. Joshua Jacobs11 cautions that “we will be most effective if our advocacy message is presented as a potential solution to the current health care crisis, not just as a demand for fair reimbursement.” Instead, we can achieve this goal with what Richard Gelberman2 summarized as “doing what we do best: accumulating knowledge, positioning ourselves as the authorities that we are, and using what we learn to advocate for better patient care and research.”

Value Medicine

Orthopedic surgeons are now expected to provide not just high-quality care but low-cost care. In line with the emerging emphasis on value, sharp focus has been placed on the assessment of physician performance and treatment outcomes as quality-of-care measures.6 But how have we measured the quality of the care we provide? We have not, or, at least, we have not had valid or reliable means of doing so.6 Gone are the days of telling the world of the excellence of our profession in the treatment of musculoskeletal disease. We now must prove to our patients, the government, and payers that what we do works.12,13 If we fail to communicate the cost effectiveness of our interventions, our new knowledge and technologies will not be accepted or funded.10 We should, however, not be discouraged by the new “value equation,” but use it as an incentive to provide evidence-based care and to improve the efficiency of resource utilization.14 Today, we are urged to be leaders in quality improvement, both in our individual orthopedic practices and as a profession.10,12,13

Conclusion

Meeting increasingly higher demands for musculoskeletal care in an evolving medical landscape will bring a new set of challenges that will be more frequent and more intense than those in the past.14 Today, we are tasked with providing fiscally efficient, culturally competent, high-quality, evidence-based, and compassionate care. We are also tasked with reclaiming our ability to shape the future of our profession at the policymaking level. In doing so, the need for unity, advocacy, commitment to education and research, women and minority representation, and open communication with the public has never been more relevant. As we continue to advance as a profession, we must resist the temptation to look back in defiance of change but move forward, confident in our ability to evolve. ◾

1. Canale ST. The orthopaedic forum. Falling in love again. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(5):739-742.

2. Gelberman RH. The Academy on the edge: taking charge of our future. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(6):946-950.

3. Tolo VT. The challenges of change: is orthopaedics ready? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(9):1707-1713.

4. Herndon JH. One more turn of the wrench. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(10):2036-2048.

5. Bucholz RW. Knowledge is our business. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(7):1575-1578.

6. Weinstein SL. Nothing about you...without you. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1648-1652.

7. Beaty JH. Presidential address: “Building the best . . . Lifelong learning”. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(9):515-518.

8. Rankin EA. Presidential Address: advocacy now... for our patients and our profession. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(6):303-305.

9. Zuckerman JD. Silk purses, sows’ ears, and heap ash—turning challenges into opportunities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(5):271-275.

10. Tongue JR. Strong on vision, flexible on details. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(4):187-189.

11. Jacobs JJ. Moving forward: from curses to blessings. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(5):261-265.

12. Callaghan JJ. Quality of care: getting from good to great. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;8(9):516-519.

13. Berry DJ. Informed by our past, building our future. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(4):187-190.

14. Azar FM. Building a bigger box. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(6):341-345.

15. Kyle RF. Presidential Address: Together we are one. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(5):261-264.

16. Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The Next Four Decades: The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Washington, DC: Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau, US Dept of Commerce; 2010.

17. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Department of Research and Scientific Affairs. 1998-2011 Resident Diversity Survey Report. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www3.aaos.org/about/diversity/pdfs/resident_trend.pdf. Published March 9, 2012. Accessed October 26, 2015.

1. Canale ST. The orthopaedic forum. Falling in love again. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(5):739-742.

2. Gelberman RH. The Academy on the edge: taking charge of our future. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(6):946-950.

3. Tolo VT. The challenges of change: is orthopaedics ready? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(9):1707-1713.

4. Herndon JH. One more turn of the wrench. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(10):2036-2048.

5. Bucholz RW. Knowledge is our business. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(7):1575-1578.

6. Weinstein SL. Nothing about you...without you. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1648-1652.

7. Beaty JH. Presidential address: “Building the best . . . Lifelong learning”. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(9):515-518.

8. Rankin EA. Presidential Address: advocacy now... for our patients and our profession. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(6):303-305.

9. Zuckerman JD. Silk purses, sows’ ears, and heap ash—turning challenges into opportunities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(5):271-275.

10. Tongue JR. Strong on vision, flexible on details. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(4):187-189.

11. Jacobs JJ. Moving forward: from curses to blessings. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(5):261-265.

12. Callaghan JJ. Quality of care: getting from good to great. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;8(9):516-519.

13. Berry DJ. Informed by our past, building our future. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(4):187-190.

14. Azar FM. Building a bigger box. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(6):341-345.

15. Kyle RF. Presidential Address: Together we are one. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(5):261-264.

16. Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The Next Four Decades: The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Washington, DC: Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau, US Dept of Commerce; 2010.

17. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Department of Research and Scientific Affairs. 1998-2011 Resident Diversity Survey Report. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website. http://www3.aaos.org/about/diversity/pdfs/resident_trend.pdf. Published March 9, 2012. Accessed October 26, 2015.

Current Evidence Does Not Support Medicare’s 3-Day Rule in Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty

Medicare beneficiaries’ demand for total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has increased significantly over the past several years, with recent studies reporting 209,945 primary THAs and 243,802 primary TKAs performed annually.1,2 With this demand has come an increase in the percentage of patients discharged to an extended-care facility (ECF) for skilled nursing care or acute rehabilitation—an estimated 49.3% for THA and 41.5% for TKA.1,2 To qualify for discharge to an ECF, Medicare beneficiaries are required to have an inpatient stay of at least 3 consecutive days.3 Although the basis of this rule is unclear, it is thought to prevent hasty discharge of unstable patients.

We conducted a study to explore the effect of this policy on length of stay (LOS) in a population of patients who underwent primary total joint arthroplasty (TJA). Based on a pilot study by our group, we hypothesized that such a statuary requirement would be associated with increased LOS and would not prevent discharge of potentially unstable patients. Specifically, we explored whether patients who could have been discharged earlier experienced any later inpatient complications or 30-day readmission to justify staying past their discharge readiness.

Materials and Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study. Between 2011 and 2012, the senior authors (Dr. Wellman, Dr. Attarian, Dr. Bolognesi) treated 985 patients with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 27130 (THA) and 27447 (TKA). Of the 985 patients, 287 (29.13%) were discharged to an ECF and were included in the study. Three of the 287 were excluded: 2 for requiring preadmission for medical optimization and 1 for having another procedure with plastic surgery. All patients were admitted from home on day of surgery and had a standardized clinical pathway with respect to pain control, mobilization, and anticoagulation. Physical therapy and occupational therapy (PT/OT) were initiated on day of surgery and were continued daily until discharge.

The primary outcome was discharge readiness, defined as meeting the criteria of stable blood pressure, pulse, and breathing; no fever over 101.5°F for 24 hours before discharge; wound healing with no concerns; pain controlled with oral medications; and ambulation or the potential for rehabilitation at the receiving facility. Secondary outcomes were changes in PT/OT progress, medical interventions, and 30-day readmission rate. PT/OT progress was categorized as either slow or steady by the therapist assigned to each patient at time of hospitalization. Steady progress indicated overall improvement on several measures, including transfers, ambulation distance, and ability to adhere to postoperative precautions; slow progress indicated no improvement on these measures.

Results for continuous variables were summarized with means, standard deviations, and ranges, and results for categorical variables were summarized with counts and percentages. Student t test was used to evaluate increase in LOS, and the McNemar test for paired data was used to analyze rehabilitation gains from readiness-for-discharge day to the next postoperative day (POD). SAS Version 9.2 software (SAS Institute) was used for all analyses.

Results

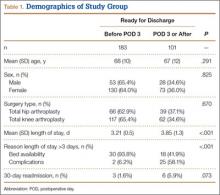

Of the 284 patients included in the study, 203 were female (71.5%), 81 male (28.5%). Mean (SD) age was 68 (11) years (range, 21-92 years). One hundred seventy-nine patients (63.0%) underwent TKA, and 105 (37.0%) underwent THA. Two hundred twenty-seven patients (80.0%) were discharged to skilled nursing care, and 57 (20.1%) to inpatient rehabilitation. Mean (SD) LOS was 3.44 (0.92) days (range, 3-9 days). One hundred eighty-three patients (64.4%) were ready for discharge on POD 2, 76 (26.8%) on POD 3, and 25 (8.8%) after POD 3. Delaying discharge until POD 3 increased LOS by 1.08 days (P < .001). Two hundred nine patients (73.6%) were discharged on POD 3, and 75 (26.4%) after POD 3. Reasons for being discharged after POD 3 were lack of ECF bed availability (48 patients, 64.0%) and postoperative complications (27 patients, 36.0%). Patients ready for discharge on POD 2 had fewer complications than patients ready after POD 2 (P < .001).

Analysis of the 183 patients who were ready for discharge on POD 2 demonstrated a statistically significant (P = .038) change in rehabilitation progress by staying an additional hospital day. However, this difference was not clinically significant: Only 17.5% of patients improved, while 82.5% remained unchanged or declined in progress. Most important, among patients who demonstrated rehabilitation gains, the improvement was not sufficient to change the decision regarding discharge destination. Three patients (1.6%) ready for discharge on POD 2 were readmitted within 30 days of discharge (2 for wound infection, 1 for syncope). Risk for 30-day readmission or development of an inpatient complication in patients ready for discharge on POD 2 was not significant (P = .073). Table 1 summarizes the statistical results.

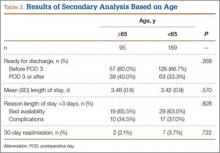

As age 65 years or older is one of the major criteria for Medicare eligibility, a secondary analysis was performed to explore whether there were age-related differences in the study outcomes. We found no significant differences between patients 65 years or older and patients younger than 65 years with respect to discharge readiness, LOS, postoperative complications, or 30-day readmission. Table 2 summarizes the statistical results based on age.

Discussion

Consistent with our pilot study,4 the majority of patients discharged to an ECF were ready for discharge on POD 2. Delaying discharge until POD 3 increased LOS by 1.08 days with no significant risk in 30-day readmission if patients were allowed to be discharged 1 day earlier. Different from our pilot study results, however, 17.5% of patients who stayed past their discharge readiness showed improvement in PT/OT progress, though this was not clinically sufficient to alter the decision regarding discharge destination. This difference can be attributed to the fact that the current study (vs the pilot study) was adequately powered for this outcome.

Our study was specifically designed to evaluate the effect of Medicare’s 3-day rule—the requirement of an inpatient hospital stay of at least 3 consecutive days to qualify for coverage for treatment at an ECF. This policy creates tremendous unnecessary hospitalization and resource utilization and denies patients earlier access to specialized postacute care. To put the economic implications of this policy in perspective, almost half of the 1 million TJAs performed annually are performed for Medicare beneficiaries, and almost half of those patients are discharged to an ECF.1,2,5 This equates to about 161,000 days of unnecessary hospitalization per year (64.4% of 250,000 patients), which translates into $310,730,000 in expenditures based on an average cost of $1930 per inpatient day for state/local government, nonprofit, and for-profit hospitals.6 Furthermore, with a growing trend toward outpatient TJA, the Medicare statute may leave substantial bills for patients who happen to require unplanned discharge to an ECF.

This study had its weaknesses. First, it was a retrospective review of charts at a single tertiary-care hospital. However, observer bias may have been eliminated, as the data were collected before a study was planned. An outcome such as discharge readiness, if prospectively assessed, could easily have been influenced by study personnel. Second, our patient sample was too small to definitively resolve this issue and be able to effect public policy change. However, there was sufficient power for the primary outcome. We also analyzed a consecutive group of patients who underwent a standardized postoperative clinical pathway with clear discharge-readiness criteria.

The effect of this study in the era of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and its Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative deserves special attention. The BPCI initiative is divided into 4 models that reconcile payments associated with an episode of care (eg, TKA) against a predetermined payment amount.7 Relevant to our study, BPCI model 2 covers inpatient hospitalization up to 30, 60, or 90 days after discharge and includes a waiver of the 3-day rule for inpatient hospitalization. There are only 60 BPCI model 2–participating health care organizations. On the basis of our study results, we think the waiver is a step in the right direction, as no demonstrable benefits were realized from having patients stay hospitalized longer. However, the waiver should not be limited to select entities, and we hope that, with further research, the statutory requirement of 3-day inpatient hospitalization will be repealed.

Conclusion

Our study results call into question the validity of Medicare’s 3-day rule, and we hope they stimulate further research to definitively resolve this question. The majority of our study patients destined for discharge to an ECF could have been safely discharged on POD 2. The implications of reducing LOS cannot be overstated. From a hospital perspective, reducing LOS eliminates unnecessary hospitalization and resource utilization. From a patient perspective, it allows earlier access to specialized care and eliminates billing confusion. From a payer perspective, it may reduce costs significantly.

1. Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991–2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227-1236.

2. Cram P, Lu X, Callaghan JJ, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Cai X, Li Y. Long-term trends in hip arthroplasty use and volume. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):278-285.e2.

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Coverage of Skilled Nursing Facility Care. Baltimore, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Product No. 10153. http://www.medicare.gov/pubs/pdf/10153.pdf. Revised January 2015. Accessed August 24, 2015.

4. Halawi MJ, Vovos TJ, Green CL, Wellman SS, Attarian DE, Bolognesi MP. Medicare’s 3-day rule: time for a rethink. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1483-1484.

5. Inpatient surgery. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/inpatient-surgery.htm. Updated April 29, 2015. Accessed August 24, 2015.

6 Hospital adjusted expenses per inpatient day by ownership. 2013. Kaiser Family Foundation website. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/expenses-per-inpatient-day-by-ownership. Accessed August 24, 2015.

7. BPCI [Bundled Payments for Care Improvement] model 2: retrospective acute & post acute care episode. Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services website. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/BPCI-Model-2. Updated August 20, 2015. Accessed August 24, 2015.

Medicare beneficiaries’ demand for total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has increased significantly over the past several years, with recent studies reporting 209,945 primary THAs and 243,802 primary TKAs performed annually.1,2 With this demand has come an increase in the percentage of patients discharged to an extended-care facility (ECF) for skilled nursing care or acute rehabilitation—an estimated 49.3% for THA and 41.5% for TKA.1,2 To qualify for discharge to an ECF, Medicare beneficiaries are required to have an inpatient stay of at least 3 consecutive days.3 Although the basis of this rule is unclear, it is thought to prevent hasty discharge of unstable patients.

We conducted a study to explore the effect of this policy on length of stay (LOS) in a population of patients who underwent primary total joint arthroplasty (TJA). Based on a pilot study by our group, we hypothesized that such a statuary requirement would be associated with increased LOS and would not prevent discharge of potentially unstable patients. Specifically, we explored whether patients who could have been discharged earlier experienced any later inpatient complications or 30-day readmission to justify staying past their discharge readiness.

Materials and Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study. Between 2011 and 2012, the senior authors (Dr. Wellman, Dr. Attarian, Dr. Bolognesi) treated 985 patients with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 27130 (THA) and 27447 (TKA). Of the 985 patients, 287 (29.13%) were discharged to an ECF and were included in the study. Three of the 287 were excluded: 2 for requiring preadmission for medical optimization and 1 for having another procedure with plastic surgery. All patients were admitted from home on day of surgery and had a standardized clinical pathway with respect to pain control, mobilization, and anticoagulation. Physical therapy and occupational therapy (PT/OT) were initiated on day of surgery and were continued daily until discharge.

The primary outcome was discharge readiness, defined as meeting the criteria of stable blood pressure, pulse, and breathing; no fever over 101.5°F for 24 hours before discharge; wound healing with no concerns; pain controlled with oral medications; and ambulation or the potential for rehabilitation at the receiving facility. Secondary outcomes were changes in PT/OT progress, medical interventions, and 30-day readmission rate. PT/OT progress was categorized as either slow or steady by the therapist assigned to each patient at time of hospitalization. Steady progress indicated overall improvement on several measures, including transfers, ambulation distance, and ability to adhere to postoperative precautions; slow progress indicated no improvement on these measures.

Results for continuous variables were summarized with means, standard deviations, and ranges, and results for categorical variables were summarized with counts and percentages. Student t test was used to evaluate increase in LOS, and the McNemar test for paired data was used to analyze rehabilitation gains from readiness-for-discharge day to the next postoperative day (POD). SAS Version 9.2 software (SAS Institute) was used for all analyses.

Results

Of the 284 patients included in the study, 203 were female (71.5%), 81 male (28.5%). Mean (SD) age was 68 (11) years (range, 21-92 years). One hundred seventy-nine patients (63.0%) underwent TKA, and 105 (37.0%) underwent THA. Two hundred twenty-seven patients (80.0%) were discharged to skilled nursing care, and 57 (20.1%) to inpatient rehabilitation. Mean (SD) LOS was 3.44 (0.92) days (range, 3-9 days). One hundred eighty-three patients (64.4%) were ready for discharge on POD 2, 76 (26.8%) on POD 3, and 25 (8.8%) after POD 3. Delaying discharge until POD 3 increased LOS by 1.08 days (P < .001). Two hundred nine patients (73.6%) were discharged on POD 3, and 75 (26.4%) after POD 3. Reasons for being discharged after POD 3 were lack of ECF bed availability (48 patients, 64.0%) and postoperative complications (27 patients, 36.0%). Patients ready for discharge on POD 2 had fewer complications than patients ready after POD 2 (P < .001).

Analysis of the 183 patients who were ready for discharge on POD 2 demonstrated a statistically significant (P = .038) change in rehabilitation progress by staying an additional hospital day. However, this difference was not clinically significant: Only 17.5% of patients improved, while 82.5% remained unchanged or declined in progress. Most important, among patients who demonstrated rehabilitation gains, the improvement was not sufficient to change the decision regarding discharge destination. Three patients (1.6%) ready for discharge on POD 2 were readmitted within 30 days of discharge (2 for wound infection, 1 for syncope). Risk for 30-day readmission or development of an inpatient complication in patients ready for discharge on POD 2 was not significant (P = .073). Table 1 summarizes the statistical results.

As age 65 years or older is one of the major criteria for Medicare eligibility, a secondary analysis was performed to explore whether there were age-related differences in the study outcomes. We found no significant differences between patients 65 years or older and patients younger than 65 years with respect to discharge readiness, LOS, postoperative complications, or 30-day readmission. Table 2 summarizes the statistical results based on age.

Discussion

Consistent with our pilot study,4 the majority of patients discharged to an ECF were ready for discharge on POD 2. Delaying discharge until POD 3 increased LOS by 1.08 days with no significant risk in 30-day readmission if patients were allowed to be discharged 1 day earlier. Different from our pilot study results, however, 17.5% of patients who stayed past their discharge readiness showed improvement in PT/OT progress, though this was not clinically sufficient to alter the decision regarding discharge destination. This difference can be attributed to the fact that the current study (vs the pilot study) was adequately powered for this outcome.

Our study was specifically designed to evaluate the effect of Medicare’s 3-day rule—the requirement of an inpatient hospital stay of at least 3 consecutive days to qualify for coverage for treatment at an ECF. This policy creates tremendous unnecessary hospitalization and resource utilization and denies patients earlier access to specialized postacute care. To put the economic implications of this policy in perspective, almost half of the 1 million TJAs performed annually are performed for Medicare beneficiaries, and almost half of those patients are discharged to an ECF.1,2,5 This equates to about 161,000 days of unnecessary hospitalization per year (64.4% of 250,000 patients), which translates into $310,730,000 in expenditures based on an average cost of $1930 per inpatient day for state/local government, nonprofit, and for-profit hospitals.6 Furthermore, with a growing trend toward outpatient TJA, the Medicare statute may leave substantial bills for patients who happen to require unplanned discharge to an ECF.

This study had its weaknesses. First, it was a retrospective review of charts at a single tertiary-care hospital. However, observer bias may have been eliminated, as the data were collected before a study was planned. An outcome such as discharge readiness, if prospectively assessed, could easily have been influenced by study personnel. Second, our patient sample was too small to definitively resolve this issue and be able to effect public policy change. However, there was sufficient power for the primary outcome. We also analyzed a consecutive group of patients who underwent a standardized postoperative clinical pathway with clear discharge-readiness criteria.

The effect of this study in the era of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and its Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative deserves special attention. The BPCI initiative is divided into 4 models that reconcile payments associated with an episode of care (eg, TKA) against a predetermined payment amount.7 Relevant to our study, BPCI model 2 covers inpatient hospitalization up to 30, 60, or 90 days after discharge and includes a waiver of the 3-day rule for inpatient hospitalization. There are only 60 BPCI model 2–participating health care organizations. On the basis of our study results, we think the waiver is a step in the right direction, as no demonstrable benefits were realized from having patients stay hospitalized longer. However, the waiver should not be limited to select entities, and we hope that, with further research, the statutory requirement of 3-day inpatient hospitalization will be repealed.

Conclusion

Our study results call into question the validity of Medicare’s 3-day rule, and we hope they stimulate further research to definitively resolve this question. The majority of our study patients destined for discharge to an ECF could have been safely discharged on POD 2. The implications of reducing LOS cannot be overstated. From a hospital perspective, reducing LOS eliminates unnecessary hospitalization and resource utilization. From a patient perspective, it allows earlier access to specialized care and eliminates billing confusion. From a payer perspective, it may reduce costs significantly.

Medicare beneficiaries’ demand for total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has increased significantly over the past several years, with recent studies reporting 209,945 primary THAs and 243,802 primary TKAs performed annually.1,2 With this demand has come an increase in the percentage of patients discharged to an extended-care facility (ECF) for skilled nursing care or acute rehabilitation—an estimated 49.3% for THA and 41.5% for TKA.1,2 To qualify for discharge to an ECF, Medicare beneficiaries are required to have an inpatient stay of at least 3 consecutive days.3 Although the basis of this rule is unclear, it is thought to prevent hasty discharge of unstable patients.

We conducted a study to explore the effect of this policy on length of stay (LOS) in a population of patients who underwent primary total joint arthroplasty (TJA). Based on a pilot study by our group, we hypothesized that such a statuary requirement would be associated with increased LOS and would not prevent discharge of potentially unstable patients. Specifically, we explored whether patients who could have been discharged earlier experienced any later inpatient complications or 30-day readmission to justify staying past their discharge readiness.

Materials and Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study. Between 2011 and 2012, the senior authors (Dr. Wellman, Dr. Attarian, Dr. Bolognesi) treated 985 patients with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 27130 (THA) and 27447 (TKA). Of the 985 patients, 287 (29.13%) were discharged to an ECF and were included in the study. Three of the 287 were excluded: 2 for requiring preadmission for medical optimization and 1 for having another procedure with plastic surgery. All patients were admitted from home on day of surgery and had a standardized clinical pathway with respect to pain control, mobilization, and anticoagulation. Physical therapy and occupational therapy (PT/OT) were initiated on day of surgery and were continued daily until discharge.

The primary outcome was discharge readiness, defined as meeting the criteria of stable blood pressure, pulse, and breathing; no fever over 101.5°F for 24 hours before discharge; wound healing with no concerns; pain controlled with oral medications; and ambulation or the potential for rehabilitation at the receiving facility. Secondary outcomes were changes in PT/OT progress, medical interventions, and 30-day readmission rate. PT/OT progress was categorized as either slow or steady by the therapist assigned to each patient at time of hospitalization. Steady progress indicated overall improvement on several measures, including transfers, ambulation distance, and ability to adhere to postoperative precautions; slow progress indicated no improvement on these measures.

Results for continuous variables were summarized with means, standard deviations, and ranges, and results for categorical variables were summarized with counts and percentages. Student t test was used to evaluate increase in LOS, and the McNemar test for paired data was used to analyze rehabilitation gains from readiness-for-discharge day to the next postoperative day (POD). SAS Version 9.2 software (SAS Institute) was used for all analyses.

Results

Of the 284 patients included in the study, 203 were female (71.5%), 81 male (28.5%). Mean (SD) age was 68 (11) years (range, 21-92 years). One hundred seventy-nine patients (63.0%) underwent TKA, and 105 (37.0%) underwent THA. Two hundred twenty-seven patients (80.0%) were discharged to skilled nursing care, and 57 (20.1%) to inpatient rehabilitation. Mean (SD) LOS was 3.44 (0.92) days (range, 3-9 days). One hundred eighty-three patients (64.4%) were ready for discharge on POD 2, 76 (26.8%) on POD 3, and 25 (8.8%) after POD 3. Delaying discharge until POD 3 increased LOS by 1.08 days (P < .001). Two hundred nine patients (73.6%) were discharged on POD 3, and 75 (26.4%) after POD 3. Reasons for being discharged after POD 3 were lack of ECF bed availability (48 patients, 64.0%) and postoperative complications (27 patients, 36.0%). Patients ready for discharge on POD 2 had fewer complications than patients ready after POD 2 (P < .001).

Analysis of the 183 patients who were ready for discharge on POD 2 demonstrated a statistically significant (P = .038) change in rehabilitation progress by staying an additional hospital day. However, this difference was not clinically significant: Only 17.5% of patients improved, while 82.5% remained unchanged or declined in progress. Most important, among patients who demonstrated rehabilitation gains, the improvement was not sufficient to change the decision regarding discharge destination. Three patients (1.6%) ready for discharge on POD 2 were readmitted within 30 days of discharge (2 for wound infection, 1 for syncope). Risk for 30-day readmission or development of an inpatient complication in patients ready for discharge on POD 2 was not significant (P = .073). Table 1 summarizes the statistical results.

As age 65 years or older is one of the major criteria for Medicare eligibility, a secondary analysis was performed to explore whether there were age-related differences in the study outcomes. We found no significant differences between patients 65 years or older and patients younger than 65 years with respect to discharge readiness, LOS, postoperative complications, or 30-day readmission. Table 2 summarizes the statistical results based on age.

Discussion

Consistent with our pilot study,4 the majority of patients discharged to an ECF were ready for discharge on POD 2. Delaying discharge until POD 3 increased LOS by 1.08 days with no significant risk in 30-day readmission if patients were allowed to be discharged 1 day earlier. Different from our pilot study results, however, 17.5% of patients who stayed past their discharge readiness showed improvement in PT/OT progress, though this was not clinically sufficient to alter the decision regarding discharge destination. This difference can be attributed to the fact that the current study (vs the pilot study) was adequately powered for this outcome.

Our study was specifically designed to evaluate the effect of Medicare’s 3-day rule—the requirement of an inpatient hospital stay of at least 3 consecutive days to qualify for coverage for treatment at an ECF. This policy creates tremendous unnecessary hospitalization and resource utilization and denies patients earlier access to specialized postacute care. To put the economic implications of this policy in perspective, almost half of the 1 million TJAs performed annually are performed for Medicare beneficiaries, and almost half of those patients are discharged to an ECF.1,2,5 This equates to about 161,000 days of unnecessary hospitalization per year (64.4% of 250,000 patients), which translates into $310,730,000 in expenditures based on an average cost of $1930 per inpatient day for state/local government, nonprofit, and for-profit hospitals.6 Furthermore, with a growing trend toward outpatient TJA, the Medicare statute may leave substantial bills for patients who happen to require unplanned discharge to an ECF.

This study had its weaknesses. First, it was a retrospective review of charts at a single tertiary-care hospital. However, observer bias may have been eliminated, as the data were collected before a study was planned. An outcome such as discharge readiness, if prospectively assessed, could easily have been influenced by study personnel. Second, our patient sample was too small to definitively resolve this issue and be able to effect public policy change. However, there was sufficient power for the primary outcome. We also analyzed a consecutive group of patients who underwent a standardized postoperative clinical pathway with clear discharge-readiness criteria.

The effect of this study in the era of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and its Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative deserves special attention. The BPCI initiative is divided into 4 models that reconcile payments associated with an episode of care (eg, TKA) against a predetermined payment amount.7 Relevant to our study, BPCI model 2 covers inpatient hospitalization up to 30, 60, or 90 days after discharge and includes a waiver of the 3-day rule for inpatient hospitalization. There are only 60 BPCI model 2–participating health care organizations. On the basis of our study results, we think the waiver is a step in the right direction, as no demonstrable benefits were realized from having patients stay hospitalized longer. However, the waiver should not be limited to select entities, and we hope that, with further research, the statutory requirement of 3-day inpatient hospitalization will be repealed.

Conclusion

Our study results call into question the validity of Medicare’s 3-day rule, and we hope they stimulate further research to definitively resolve this question. The majority of our study patients destined for discharge to an ECF could have been safely discharged on POD 2. The implications of reducing LOS cannot be overstated. From a hospital perspective, reducing LOS eliminates unnecessary hospitalization and resource utilization. From a patient perspective, it allows earlier access to specialized care and eliminates billing confusion. From a payer perspective, it may reduce costs significantly.

1. Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991–2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227-1236.

2. Cram P, Lu X, Callaghan JJ, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Cai X, Li Y. Long-term trends in hip arthroplasty use and volume. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):278-285.e2.

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Coverage of Skilled Nursing Facility Care. Baltimore, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Product No. 10153. http://www.medicare.gov/pubs/pdf/10153.pdf. Revised January 2015. Accessed August 24, 2015.

4. Halawi MJ, Vovos TJ, Green CL, Wellman SS, Attarian DE, Bolognesi MP. Medicare’s 3-day rule: time for a rethink. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1483-1484.

5. Inpatient surgery. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/inpatient-surgery.htm. Updated April 29, 2015. Accessed August 24, 2015.

6 Hospital adjusted expenses per inpatient day by ownership. 2013. Kaiser Family Foundation website. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/expenses-per-inpatient-day-by-ownership. Accessed August 24, 2015.

7. BPCI [Bundled Payments for Care Improvement] model 2: retrospective acute & post acute care episode. Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services website. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/BPCI-Model-2. Updated August 20, 2015. Accessed August 24, 2015.

1. Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991–2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227-1236.

2. Cram P, Lu X, Callaghan JJ, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Cai X, Li Y. Long-term trends in hip arthroplasty use and volume. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):278-285.e2.

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Coverage of Skilled Nursing Facility Care. Baltimore, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Product No. 10153. http://www.medicare.gov/pubs/pdf/10153.pdf. Revised January 2015. Accessed August 24, 2015.

4. Halawi MJ, Vovos TJ, Green CL, Wellman SS, Attarian DE, Bolognesi MP. Medicare’s 3-day rule: time for a rethink. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1483-1484.

5. Inpatient surgery. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics website. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/inpatient-surgery.htm. Updated April 29, 2015. Accessed August 24, 2015.

6 Hospital adjusted expenses per inpatient day by ownership. 2013. Kaiser Family Foundation website. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/expenses-per-inpatient-day-by-ownership. Accessed August 24, 2015.

7. BPCI [Bundled Payments for Care Improvement] model 2: retrospective acute & post acute care episode. Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services website. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/BPCI-Model-2. Updated August 20, 2015. Accessed August 24, 2015.