User login

Geriatric syndromes are multifactorial health conditions that affect older people and include dementia, delirium, impaired mobility, falls, frailty, poor nutrition, weight loss, incontinence, and difficulties with activities of daily living.1 These syndromes are highly prevalent among older patients admitted to acute-care hospitals2,3 and often add complexity to the clinical status of hospitalized older adults with multiple comorbid conditions.4 In the English National Health Service (NHS), the proportion of older people admitted to acute-care hospitals with geriatric syndromes has increased dramatically.5

The recognition and management of geriatric syndromes by hospitalists requires specific knowledge and skill sets.6 However, geriatricians are a scarce resource in many settings, including the NHS. A challenge for service evaluation and research is the generally poor capture of information about geriatric syndromes compared to specific comorbidities in discharge summaries and hospital coding.7 Steps are being taken in the NHS to address this issue, and in 2013 our center started the routine collection of data on clinical frailty, history of dementia (HoD) and acute confusional state (ACS) in all patients 75 years or older admitted nonelectively to the hospital.8The presence of geriatric syndromes in older inpatients is an important driver of adverse outcomes, particularly length of stay (LOS) and admission to institutional care.9 However, acute illness severity (AIS) is also an important determinant of poor outcomes in the inpatient population and may drive disproportionate changes in health status in the most vulnerable.10 Research studies with geriatric syndromes in acute settings have not been able to simultaneously consider AIS.11 In addition, comorbidity is not always associated with an increased number of geriatric syndromes.12

We aimed to study the association of geriatric syndromes such as frailty, HoD and ACS that are measured in routine clinical care with hospital outcomes (prolonged LOS, inpatient mortality, delayed discharge, institutionalization, and 30-day readmission), while controlling for demographics (age, gender), AIS, comorbidity, and discharging specialty (general medicine, geriatric medicine, surgery).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective observational study was conducted in a large tertiary university hospital in England with 1000 acute beds receiving more than 102,000 visits to the emergency department (ED) and admitting over 73,000 patients per year; among the latter, more than 12,000 are 75 years and older.

Sample

We analyzed all first nonelective inpatient episodes (ie, from ED admission to discharge) of people 75 years and older (all specialties) between the October 26, 2014 and the October 26, 2015. Data were obtained via the hospital’s information systems following the implementation of a new electronic patient record on October 26, 2014.

Patients’ Characteristics

The following anonymized variables were extracted:

- Age and gender

- AIS information is routinely collected in our ED using a Modified Early Warning Score (ED-MEWS). The components and scoring of ED-MEWS are shown in Table 1. Where more than 1 ED-MEWS was collected, the highest was used in the analyses.

- Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI, without age adjustment).13 The CCI is based on the discharge diagnoses, as coded according to WHO International Classification of Diseases, v 10 (ICD-10). The CCI was calculated retrospectively and would have not been available to clinicians early during the patients’ admission.

- Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS). The scoring of CFS is based on a global assessment of patients’ comorbidity symptoms, and their level of physical activity and dependency on activities of daily living, estimated to reflect the status immediately before the onset of the acute illness leading to hospitalization. The possible scores are: 1 (very fit), 2 (well), 3 (managing well), 4 (vulnerable), 5 (mildly frail), 6 (moderately frail), 7 (severely frail), 8 (very severely frail), and 9 (terminally ill) ().14 The use of the CFS in admissions of people 75 years and older was introduced in our center in 2013 under a local Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) scheme.8 The CQUIN required that all patients 75 years and older admitted to the hospital, via the ED, be screened for frailty using the CFS within 72 hours of admission. The admitting doctor usually scores the CFS on the electronic admission record, but it can also be completed by ED nurses or by nursing or therapy staff from the trust-wide Specialist Advice for the Frail Elderly team. Training on CFS scoring is provided to staff at a hiring orientation and at regular educational meetings. Permission to use CFS for clinical purposes was obtained from the principal investigator at Geriatric Medicine Research, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada.

- Cognitive variables were collected early during the admission in patients 75 years and older, thanks to a parallel local CQUIN scheme. The cognitive CQUIN variables are screening variables, not gold standard. The admission clerking is designed to clinically classify patients within 72 hours of admission into the following 3 mutually exclusive categories:

○ Known HoD (in the database: no = 0; yes = 1)

○ ACS, without HoD (in the database: no = 0; yes = 1)

○ Neither HoD nor ACS

- The cognitive CQUIN assessment does not intend to diagnose dementia in those who are not known to have it, but tries to separate the dementias that general practitioners (GPs) know from hospital-identified acute cognitive concerns that GPs may need to assess or investigate after discharge. The latter may include delirium and/or undiagnosed dementia.

- In our routine hospital practice, the initial cognitive assessment is performed by a clinician in the following fashion: if the patient is known to have dementia (ie, based on clinical history and/or chart review), the clinician selects the “known history of dementia” option in the admission navigator, and no further cognitive screening is conducted. If the patient has no known dementia, the clinician administers the 4-item Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT4): (1) age, (2) date of birth, (3) place, and (4) year, with impaired cognition indicated by an AMT4 of less than 4 and triggering the selection of “ACS without known HoD” option. If the AMT4 is normal, the clinician selects the “neither HoD nor ACS” option.

- Due to the service evaluation nature of our work, these measures could not be assessed for reliability within the electronic medical records system (eg, regarding sensitivity and specificity against a gold standard or inter-rater reliability).

- Discharged from geriatric medicine (no = 0; yes = 1). Every year, our hospital admits over 12,000 patients 75 years and older, of which 25% are managed by the Department of Medicine for the Elderly (DME). The DME specialist bed base consists of 5 core wards, which specialize in ward-based comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and are supported by dedicated nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and social work teams, as well as by readily available input from speech and language therapy, clinical nutrition, psychogeriatric, pharmacy and palliative care teams. Formal multidisciplinary team meetings occur at least twice weekly. A sixth specialist DME ward with a more acute perspective has been operational for 7 years; this ward was renamed the Frailty and Acute Medicine for the Elderly (FAME) ward in 2014 and has daily multidisciplinary team meetings. Although admission to FAME is through the ED, admission to core DME wards can occur from FAME (ie, within-DME transfer), via the ED, or from other inpatient specialty areas if older patients are perceived to be in high need of CGA after screening by the Specialist Advice for the Frail Elderly team. An audit in our center showed that up to 20% of patients discharged by DME were not initially admitted by DME, underscoring the significant role of core specialist DME wards in absorbing complex cases, especially from the general medical wards.8

- Discharged from general medicine (no = 0; yes = 1). In our setting, virtually all patients discharged by general medicine were first admitted by general medicine.8

- Discharged by a surgical specialty (no = 0; yes = 1)

Hospital Outcomes

The following anonymized variables were identified:

- LOS (days). Prolonged LOS was defined as 10 or more days (no = 0; yes = 1)

- Inpatient mortality (no = 0; yes = 1)

- Delayed discharge (no = 0; yes = 1). This was defined as the total LOS being at least 1 day longer than the LOS up to the last recorded clinically fit date. This date is used in NHS hospitals to indicate that the acute medical episode has finished and discharge-planning arrangements (often via social care providers) can commence.

- Institutionalization (no = 0; yes = 1). This was defined as the discharge destination being a care home, when a care home was not the usual place of residence.

- 30-day readmission (no = 0; yes = 1)

Statistical Analyses

Anonymized data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics (v 22, Armonk, New York) software. Descriptive statistics were given as count (with percentage) or mean (with standard deviation.

To avoid potential problems with multicollinearity in the multivariate regression models, the correlations among the predictor variables were checked using a correlation matrix of 2-sided Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients. Correlations of 0.50 or more were considered large.15,16

Because all outcomes in the study were binary, multivariate binary logistic regression models were computed. In these models, the odds ratio (OR) reflects the effect size of each predictor; 95% confidence intervals (CI) were requested for each OR. Predictors with P < 0.01 were considered as statistically significant. The classification performance of each logistic regression model was assessed calculating its area under the curve (AUC).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted after imputing missing data (SPSS multiple imputation procedure) and after fitting interaction terms between geriatric syndromes and discharge by geriatric medicine.

RESULTS

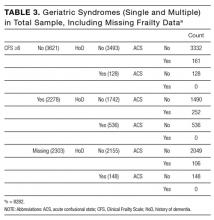

The initial database contained 12,282 nonelective admission and discharge episodes (all specialties) of patients 75 years and older between October 26, 2014 and October 26, 2015. Among those, 8202 (66.8%) were first episodes. Table 2 shows the sample descriptives, and Table 3 shows the breakdown of geriatric syndromes (single and multiple) in the total sample (n = 8282), including missing frailty data.

In the correlation matrix of 2-sided Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients, no correlations with large-effect size were found to suggest issues with multicollinearity; the largest correlation coefficients were between age and CFS (rho = 0.35), HoD and CFS (rho = 0.32), and CCI and CFS (rho = 0.26).

The results of the multivariate regression models are shown in Table 4. The best performing models were the ones for inpatient mortality (AUC = 0.80), followed by institutionalization (AUC = 0.76), and prolonged LOS (AUC = 0.71). After full adjustment, clinical frailty was an independent predictor of prolonged LOS, inpatient mortality, delayed discharge, and institutionalization. HoD was an independent predictor of prolonged LOS, delayed discharge, and institutionalization; and ACS was an independent predictor of prolonged LOS, delayed discharge, institutionalization, and 30-day readmission (Table 4). Results did not significantly change in sensitivity analyses conducted after multiple imputation of missing data and after inclusion of interaction terms (see Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Table

DISCUSSION

Our aim was to study the association of geriatric syndromes (measured in routine clinical care) with hospital outcomes. We found that geriatric syndromes such as clinical frailty, HoD, and ACS were strong independent predictors. Concerning prolonged LOS, delayed discharge, and institutionalization, geriatric syndromes had ORs that were greater than those of traditionally measured factors such as demographics, comorbidity and acute illness severity. Our findings add to the body of knowledge in this area because we accounted for the latter effects. Our experience shows that metrics on geriatric syndromes can be successfully collected in the routine hospital setting and add clear value to the prediction of operational outcomes. This may encourage other hospitals to do the same.

Our findings are consistent with suggestions that accounting for chronic conditions alone may be less informative than also accounting for the co-occurrence of geriatric syndromes.17 The focus of CFS is on the pre-admission level of physical activity and dependency on activities of daily living, and poorer scores may confer vulnerability to adverse outcomes due to reduced physiological reserve and ability to withstand acute stressors.18 Other studies have also found CFS to be a good predictor of inpatient outcomes,19-22 and it has been recommended as a possible means to identify vulnerable older adults in acute-care settings.23

HoD and ACS had independent effects beyond frailty, particularly in prolonging LOS, delaying discharge, and requiring institutionalization. Dementia prolongs LOS,24 and delirium prolongs hospitalization for persons with dementia.25 Older people with cognitive impairment may have an increased risk of acquiring new geriatric syndromes during hospitalization, particularly if it is prolonged.26 One study showed that the risk of poor functional recovery can be as high as 70% in complex delirious patients in hospital.27 All too often, delirium is neither benign nor reversible, with a significant proportion of patients not experiencing restoration ad integrum of cognition and function.28

Our results are consistent with observations that geriatric syndromes are associated with higher risk of institutionalization.29 It was interesting that female gender seemed to be an independent predictor of institutionalization, which is consistent with the results of a systematic review showing that the male-to-female ratio of admission rates ranged between 1 to 1.4 and 1 to 1.6.30

Discharge by general medicine appeared to be associated with a lower likelihood of prolonged LOS, and discharge by geriatric medicine seemed to be associated with a higher likelihood of delayed discharge and institutionalization. Unsurprisingly, geriatric medicine wards tend to absorb the most complex cases, often with complex discharge planning needs.8 In that light, CGA in geriatric wards may not be associated with reduced LOS (and it is possible that the LOS of complex patients might have been higher in nongeriatric wards). In addition, inpatient CGA increases frail patients’ likelihood of survival.31

Our study suggests that routinely collected metrics on frailty, HoD and ACS may be helpful to better adapt hospital care to the real requirements of aged people. The proportion of older people admitted to acute hospitals with geriatric syndromes continues to increase5 and geriatricians are a scarce resource. It will be increasingly important to upskill nongeriatric hospitalists in the recognition and management of geriatric syndromes. Frail older people are becoming the core business of acute hospitals,32 making geriatrics “too important to be left to geriatricians.”33 Therefore, easily collected metrics on geriatric syndromes may help nongeriatricians identify these syndromes and address them early during admission.

Our study has important limitations. Firstly, geriatric syndromes were not identified with gold-standard measures. For example, ACS in the absence of known dementia should be seen only as a surrogate for delirium. ACS as a proxy measure is likely to underestimate the diagnosis of delirium, because the hypoactive type is commonly missed without valid measures. In addition, a patient with delirium superimposed upon dementia would have been coded as a ‘known dementia.’ The geriatric syndromes’ measures could not be assessed for reliability within the electronic medical records system (eg, regarding sensitivity and specificity against a gold standard, or interrater reliability).

About the potential limitations of CFS, there have been concerns that an interobserver discrepancy in CFS scoring may occur between health professionals. However, 1 study investigated the interrater reliability of CFS between clinicians in 107 community-dwelling older adults 75 years and older, finding a substantial agreement with a weighted

Another limitation of our study is that we treated geriatric syndromes and the other predictors in the models as independent variables. However, many of the factors may be interrelated, and they present simultaneously in many patients. Indeed, the bivariate correlation between CFS and HoD was of moderate strength, because worsening cognition should score higher on CFS according to the scoring protocol. As expected, there was also a medium-sized correlation between CFS and CCI. It has been suggested that physical and cognitive frailty may be more informative as a single complex phenotype.36 Indeed, the problems of old age tend to come as a package.37

For 30-day readmission, the AUC of the model was small, suggesting the existence of unmeasured explanatory variables. For example, although our results agree that AIS and chronic illness predict readmission,38 the latter still remains an elusive outcome, and a more accurate prediction may be attained by adding socioeconomic variables to models.39Our study echoes the potential utility of incorporating common geriatric clinical features in routine clinical examination and disposition planning for older patients in acute settings.40 Hospitals may find it informative to undertake large-scale screening for geriatric syndromes including frailty, dementia, and delirium in all older adults admitted via the ED. When combined with other routinely collected variables such as demographics, AIS, and comorbidity data, this process may provide hospitals with information that will help define the acute needs of the local population and aid in the development of care pathways for the growing population of older adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all members of the acute teams in our hospital, without which this initiative would have not been possible. Licensed access to the NHS Foundation Trust’s information systems is also gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

1. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780-791. PubMed

2. Lakhan P, Jones M, Wilson A, Courtney M, Hirdes J, Gray LC. A prospective cohort study of geriatric syndromes among older medical patients admitted to acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2001-2008. PubMed

3. Flood KL, Rohlfing A, Le CV, Carr DB, Rich MW. Geriatric syndromes in elderly patients admitted to an inpatient cardiology ward. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:394-400. PubMed

4. Clerencia-Sierra M, Calderon-Larranaga A, Martinez-Velilla N, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in hospitalized older patients: associations among chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132909. PubMed

5. Soong J, Poots AJ, Scott S, et al. Quantifying the prevalence of frailty in English hospitals. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008456. PubMed

6. Warshaw GA, Bragg EJ, Fried LP, Hall WJ. Which patients benefit the most from a geriatrician’s care? Consensus among directors of geriatrics academic programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1796-1801. PubMed

7. Ugboma I, Syddall HE, Cox V, Cooper C, Briggs R, Sayer AA. Coding geriatric syndromes: How good are we? CME J Geriatr Med. 2008;10:34-36. PubMed

8. Wallis SJ, Wall J, Biram RW, Romero-Ortuno R. Association of the clinical frailty scale with hospital outcomes. QJM. 2015;108:943-949. PubMed

9. Anpalahan M, Gibson SJ. Geriatric syndromes as predictors of adverse outcomes of hospitalization. Intern Med J. 2008;38:16-23. PubMed

10. Cournane S, Byrne D, O’Riordan D, Fitzgerald B, Silke B. Chronic disabling disease--impact on outcomes and costs in emergency medical admissions. QJM. 2015;108:387-396. PubMed

11. Soong J, Poots AJ, Scott S, Donald K, Bell D. Developing and validating a risk prediction model for acute care based on frailty syndromes. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008457. PubMed

12. Vetrano DL, Foebel AD, Marengoni A, et al. Chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes: The different weight of comorbidity. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;27:62-67. PubMed

13. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. PubMed

14. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489-495. PubMed

15. Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141:2-18. PubMed

16. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

17. Koroukian SM, Schiltz N, Warner DF, et al. Combinations of chronic conditions, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes that predict health outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:630-637. PubMed

18. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752-762. PubMed

19. Romanowski KS, Barsun A, Pamlieri TL, Greenhalgh DG, Sen S. Frailty score on admission predicts outcomes in elderly burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2015;36:1-6. PubMed

20. Ritt M, Schwarz C, Kronawitter V, et al. Analysis of Rockwood et al’s clinical frailty scale and Fried et al’s frailty phenotype as predictors of mortality and other clinical outcomes in older patients who were admitted to a geriatric ward. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:1043-1048. PubMed

21. Murali-Krishnan R, Iqbal J, Rowe R, et al. Impact of frailty on outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective cohort study. Open Heart. 2015;2:e000294. PubMed

22. Kang L, Zhang SY, Zhu WL, et al. Is frailty associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome? J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12:662-667.

23. Conroy S, Chikura G. Emergency care for frail older people-urgent AND important-but what works? Age Ageing. 2015;44:724-725. PubMed

24. Connolly S, O’Shea E. The impact of dementia on length of stay in acute hospitals in Ireland. Dementia (London). 2015;14:650-658. PubMed

25. Fick DM, Steis MR, Waller JL, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia is associated with prolonged length of stay and poor outcomes in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:500-505. PubMed

26. Mecocci P, von Strauss E, Cherubini A, et al. Cognitive impairment is the major risk factor for development of geriatric syndromes during hospitalization: results from the GIFA study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20:262-269. PubMed

27. Dasgupta M, Brymer C. Poor functional recovery after delirium is associated with other geriatric syndromes and additional illnesses. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:793-802. PubMed

28. Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, et al. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:30-39.

29. Wang SY, Shamliyan TA, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Not just specific diseases: systematic review of the association of geriatric syndromes with hospitalization or nursing home admission. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57:16-26. PubMed

30. Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Gender differences in predictors of nursing home placement in the elderly: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:1015-1025. PubMed

31. Ellis G, Whitehead MA, O’Neill D, Langhorne P, Robinson D. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD006211. PubMed

32. HSJ/SERCO. Commission on Hospital Care for Frail Older People. Main Report. Available at: http://www.hsj.co.uk/Journals/2014/11/18/l/q/r/HSJ141121_FRAILOLDERPEOPLE_LO-RES.pdf. 2014.

33. Coni N. The unlikely geriatricians. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:587-589. PubMed

34. Islam A. Gait variability is an independent marker of frailty. Electronic thesis and dissertation repository, the University of Western Ontario, 2012. Available at: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/558. Accessed July 23, 2016.

35. Grossman D, Rootenberg M, Perri GA, et al. Enhancing communication in end-of-life care: a clinical tool translating between the Clinical Frailty Scale and the Palliative Performance Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1562-1567. PubMed

36. Panza F, Seripa D, Solfrizzi V, et al. Targeting cognitive frailty: clinical and neurobiological roadmap for a single complex phenotype. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:793-813. PubMed

37. Fontana L, Kennedy BK, Longo VD, Seals D, Melov S. Medical research: treat ageing. Nature. 2014;511:405-407. PubMed

38. Conway R, Byrne D, O’Riordan D, Silke B. Emergency readmissions are substantially determined by acute illness severity and chronic debilitating illness: a single centre cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:12-17. PubMed

39. Cournane S, Byrne D, Conway R, O’Riordan D, Coveney S, Silke B. Social deprivation and hospital admission rates, length of stay and readmissions in emergency medical admissions. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:766-771. PubMed

40. Costa AP, Hirdes JP, Heckman GA, et al. Geriatric syndromes predict postdischarge outcomes among older emergency department patients: findings from the interRAI Multinational Emergency Department Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:422-433. PubMed

Geriatric syndromes are multifactorial health conditions that affect older people and include dementia, delirium, impaired mobility, falls, frailty, poor nutrition, weight loss, incontinence, and difficulties with activities of daily living.1 These syndromes are highly prevalent among older patients admitted to acute-care hospitals2,3 and often add complexity to the clinical status of hospitalized older adults with multiple comorbid conditions.4 In the English National Health Service (NHS), the proportion of older people admitted to acute-care hospitals with geriatric syndromes has increased dramatically.5

The recognition and management of geriatric syndromes by hospitalists requires specific knowledge and skill sets.6 However, geriatricians are a scarce resource in many settings, including the NHS. A challenge for service evaluation and research is the generally poor capture of information about geriatric syndromes compared to specific comorbidities in discharge summaries and hospital coding.7 Steps are being taken in the NHS to address this issue, and in 2013 our center started the routine collection of data on clinical frailty, history of dementia (HoD) and acute confusional state (ACS) in all patients 75 years or older admitted nonelectively to the hospital.8The presence of geriatric syndromes in older inpatients is an important driver of adverse outcomes, particularly length of stay (LOS) and admission to institutional care.9 However, acute illness severity (AIS) is also an important determinant of poor outcomes in the inpatient population and may drive disproportionate changes in health status in the most vulnerable.10 Research studies with geriatric syndromes in acute settings have not been able to simultaneously consider AIS.11 In addition, comorbidity is not always associated with an increased number of geriatric syndromes.12

We aimed to study the association of geriatric syndromes such as frailty, HoD and ACS that are measured in routine clinical care with hospital outcomes (prolonged LOS, inpatient mortality, delayed discharge, institutionalization, and 30-day readmission), while controlling for demographics (age, gender), AIS, comorbidity, and discharging specialty (general medicine, geriatric medicine, surgery).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective observational study was conducted in a large tertiary university hospital in England with 1000 acute beds receiving more than 102,000 visits to the emergency department (ED) and admitting over 73,000 patients per year; among the latter, more than 12,000 are 75 years and older.

Sample

We analyzed all first nonelective inpatient episodes (ie, from ED admission to discharge) of people 75 years and older (all specialties) between the October 26, 2014 and the October 26, 2015. Data were obtained via the hospital’s information systems following the implementation of a new electronic patient record on October 26, 2014.

Patients’ Characteristics

The following anonymized variables were extracted:

- Age and gender

- AIS information is routinely collected in our ED using a Modified Early Warning Score (ED-MEWS). The components and scoring of ED-MEWS are shown in Table 1. Where more than 1 ED-MEWS was collected, the highest was used in the analyses.

- Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI, without age adjustment).13 The CCI is based on the discharge diagnoses, as coded according to WHO International Classification of Diseases, v 10 (ICD-10). The CCI was calculated retrospectively and would have not been available to clinicians early during the patients’ admission.

- Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS). The scoring of CFS is based on a global assessment of patients’ comorbidity symptoms, and their level of physical activity and dependency on activities of daily living, estimated to reflect the status immediately before the onset of the acute illness leading to hospitalization. The possible scores are: 1 (very fit), 2 (well), 3 (managing well), 4 (vulnerable), 5 (mildly frail), 6 (moderately frail), 7 (severely frail), 8 (very severely frail), and 9 (terminally ill) ().14 The use of the CFS in admissions of people 75 years and older was introduced in our center in 2013 under a local Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) scheme.8 The CQUIN required that all patients 75 years and older admitted to the hospital, via the ED, be screened for frailty using the CFS within 72 hours of admission. The admitting doctor usually scores the CFS on the electronic admission record, but it can also be completed by ED nurses or by nursing or therapy staff from the trust-wide Specialist Advice for the Frail Elderly team. Training on CFS scoring is provided to staff at a hiring orientation and at regular educational meetings. Permission to use CFS for clinical purposes was obtained from the principal investigator at Geriatric Medicine Research, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada.

- Cognitive variables were collected early during the admission in patients 75 years and older, thanks to a parallel local CQUIN scheme. The cognitive CQUIN variables are screening variables, not gold standard. The admission clerking is designed to clinically classify patients within 72 hours of admission into the following 3 mutually exclusive categories:

○ Known HoD (in the database: no = 0; yes = 1)

○ ACS, without HoD (in the database: no = 0; yes = 1)

○ Neither HoD nor ACS

- The cognitive CQUIN assessment does not intend to diagnose dementia in those who are not known to have it, but tries to separate the dementias that general practitioners (GPs) know from hospital-identified acute cognitive concerns that GPs may need to assess or investigate after discharge. The latter may include delirium and/or undiagnosed dementia.

- In our routine hospital practice, the initial cognitive assessment is performed by a clinician in the following fashion: if the patient is known to have dementia (ie, based on clinical history and/or chart review), the clinician selects the “known history of dementia” option in the admission navigator, and no further cognitive screening is conducted. If the patient has no known dementia, the clinician administers the 4-item Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT4): (1) age, (2) date of birth, (3) place, and (4) year, with impaired cognition indicated by an AMT4 of less than 4 and triggering the selection of “ACS without known HoD” option. If the AMT4 is normal, the clinician selects the “neither HoD nor ACS” option.

- Due to the service evaluation nature of our work, these measures could not be assessed for reliability within the electronic medical records system (eg, regarding sensitivity and specificity against a gold standard or inter-rater reliability).

- Discharged from geriatric medicine (no = 0; yes = 1). Every year, our hospital admits over 12,000 patients 75 years and older, of which 25% are managed by the Department of Medicine for the Elderly (DME). The DME specialist bed base consists of 5 core wards, which specialize in ward-based comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and are supported by dedicated nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and social work teams, as well as by readily available input from speech and language therapy, clinical nutrition, psychogeriatric, pharmacy and palliative care teams. Formal multidisciplinary team meetings occur at least twice weekly. A sixth specialist DME ward with a more acute perspective has been operational for 7 years; this ward was renamed the Frailty and Acute Medicine for the Elderly (FAME) ward in 2014 and has daily multidisciplinary team meetings. Although admission to FAME is through the ED, admission to core DME wards can occur from FAME (ie, within-DME transfer), via the ED, or from other inpatient specialty areas if older patients are perceived to be in high need of CGA after screening by the Specialist Advice for the Frail Elderly team. An audit in our center showed that up to 20% of patients discharged by DME were not initially admitted by DME, underscoring the significant role of core specialist DME wards in absorbing complex cases, especially from the general medical wards.8

- Discharged from general medicine (no = 0; yes = 1). In our setting, virtually all patients discharged by general medicine were first admitted by general medicine.8

- Discharged by a surgical specialty (no = 0; yes = 1)

Hospital Outcomes

The following anonymized variables were identified:

- LOS (days). Prolonged LOS was defined as 10 or more days (no = 0; yes = 1)

- Inpatient mortality (no = 0; yes = 1)

- Delayed discharge (no = 0; yes = 1). This was defined as the total LOS being at least 1 day longer than the LOS up to the last recorded clinically fit date. This date is used in NHS hospitals to indicate that the acute medical episode has finished and discharge-planning arrangements (often via social care providers) can commence.

- Institutionalization (no = 0; yes = 1). This was defined as the discharge destination being a care home, when a care home was not the usual place of residence.

- 30-day readmission (no = 0; yes = 1)

Statistical Analyses

Anonymized data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics (v 22, Armonk, New York) software. Descriptive statistics were given as count (with percentage) or mean (with standard deviation.

To avoid potential problems with multicollinearity in the multivariate regression models, the correlations among the predictor variables were checked using a correlation matrix of 2-sided Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients. Correlations of 0.50 or more were considered large.15,16

Because all outcomes in the study were binary, multivariate binary logistic regression models were computed. In these models, the odds ratio (OR) reflects the effect size of each predictor; 95% confidence intervals (CI) were requested for each OR. Predictors with P < 0.01 were considered as statistically significant. The classification performance of each logistic regression model was assessed calculating its area under the curve (AUC).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted after imputing missing data (SPSS multiple imputation procedure) and after fitting interaction terms between geriatric syndromes and discharge by geriatric medicine.

RESULTS

The initial database contained 12,282 nonelective admission and discharge episodes (all specialties) of patients 75 years and older between October 26, 2014 and October 26, 2015. Among those, 8202 (66.8%) were first episodes. Table 2 shows the sample descriptives, and Table 3 shows the breakdown of geriatric syndromes (single and multiple) in the total sample (n = 8282), including missing frailty data.

In the correlation matrix of 2-sided Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients, no correlations with large-effect size were found to suggest issues with multicollinearity; the largest correlation coefficients were between age and CFS (rho = 0.35), HoD and CFS (rho = 0.32), and CCI and CFS (rho = 0.26).

The results of the multivariate regression models are shown in Table 4. The best performing models were the ones for inpatient mortality (AUC = 0.80), followed by institutionalization (AUC = 0.76), and prolonged LOS (AUC = 0.71). After full adjustment, clinical frailty was an independent predictor of prolonged LOS, inpatient mortality, delayed discharge, and institutionalization. HoD was an independent predictor of prolonged LOS, delayed discharge, and institutionalization; and ACS was an independent predictor of prolonged LOS, delayed discharge, institutionalization, and 30-day readmission (Table 4). Results did not significantly change in sensitivity analyses conducted after multiple imputation of missing data and after inclusion of interaction terms (see Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Table

DISCUSSION

Our aim was to study the association of geriatric syndromes (measured in routine clinical care) with hospital outcomes. We found that geriatric syndromes such as clinical frailty, HoD, and ACS were strong independent predictors. Concerning prolonged LOS, delayed discharge, and institutionalization, geriatric syndromes had ORs that were greater than those of traditionally measured factors such as demographics, comorbidity and acute illness severity. Our findings add to the body of knowledge in this area because we accounted for the latter effects. Our experience shows that metrics on geriatric syndromes can be successfully collected in the routine hospital setting and add clear value to the prediction of operational outcomes. This may encourage other hospitals to do the same.

Our findings are consistent with suggestions that accounting for chronic conditions alone may be less informative than also accounting for the co-occurrence of geriatric syndromes.17 The focus of CFS is on the pre-admission level of physical activity and dependency on activities of daily living, and poorer scores may confer vulnerability to adverse outcomes due to reduced physiological reserve and ability to withstand acute stressors.18 Other studies have also found CFS to be a good predictor of inpatient outcomes,19-22 and it has been recommended as a possible means to identify vulnerable older adults in acute-care settings.23

HoD and ACS had independent effects beyond frailty, particularly in prolonging LOS, delaying discharge, and requiring institutionalization. Dementia prolongs LOS,24 and delirium prolongs hospitalization for persons with dementia.25 Older people with cognitive impairment may have an increased risk of acquiring new geriatric syndromes during hospitalization, particularly if it is prolonged.26 One study showed that the risk of poor functional recovery can be as high as 70% in complex delirious patients in hospital.27 All too often, delirium is neither benign nor reversible, with a significant proportion of patients not experiencing restoration ad integrum of cognition and function.28

Our results are consistent with observations that geriatric syndromes are associated with higher risk of institutionalization.29 It was interesting that female gender seemed to be an independent predictor of institutionalization, which is consistent with the results of a systematic review showing that the male-to-female ratio of admission rates ranged between 1 to 1.4 and 1 to 1.6.30

Discharge by general medicine appeared to be associated with a lower likelihood of prolonged LOS, and discharge by geriatric medicine seemed to be associated with a higher likelihood of delayed discharge and institutionalization. Unsurprisingly, geriatric medicine wards tend to absorb the most complex cases, often with complex discharge planning needs.8 In that light, CGA in geriatric wards may not be associated with reduced LOS (and it is possible that the LOS of complex patients might have been higher in nongeriatric wards). In addition, inpatient CGA increases frail patients’ likelihood of survival.31

Our study suggests that routinely collected metrics on frailty, HoD and ACS may be helpful to better adapt hospital care to the real requirements of aged people. The proportion of older people admitted to acute hospitals with geriatric syndromes continues to increase5 and geriatricians are a scarce resource. It will be increasingly important to upskill nongeriatric hospitalists in the recognition and management of geriatric syndromes. Frail older people are becoming the core business of acute hospitals,32 making geriatrics “too important to be left to geriatricians.”33 Therefore, easily collected metrics on geriatric syndromes may help nongeriatricians identify these syndromes and address them early during admission.

Our study has important limitations. Firstly, geriatric syndromes were not identified with gold-standard measures. For example, ACS in the absence of known dementia should be seen only as a surrogate for delirium. ACS as a proxy measure is likely to underestimate the diagnosis of delirium, because the hypoactive type is commonly missed without valid measures. In addition, a patient with delirium superimposed upon dementia would have been coded as a ‘known dementia.’ The geriatric syndromes’ measures could not be assessed for reliability within the electronic medical records system (eg, regarding sensitivity and specificity against a gold standard, or interrater reliability).

About the potential limitations of CFS, there have been concerns that an interobserver discrepancy in CFS scoring may occur between health professionals. However, 1 study investigated the interrater reliability of CFS between clinicians in 107 community-dwelling older adults 75 years and older, finding a substantial agreement with a weighted

Another limitation of our study is that we treated geriatric syndromes and the other predictors in the models as independent variables. However, many of the factors may be interrelated, and they present simultaneously in many patients. Indeed, the bivariate correlation between CFS and HoD was of moderate strength, because worsening cognition should score higher on CFS according to the scoring protocol. As expected, there was also a medium-sized correlation between CFS and CCI. It has been suggested that physical and cognitive frailty may be more informative as a single complex phenotype.36 Indeed, the problems of old age tend to come as a package.37

For 30-day readmission, the AUC of the model was small, suggesting the existence of unmeasured explanatory variables. For example, although our results agree that AIS and chronic illness predict readmission,38 the latter still remains an elusive outcome, and a more accurate prediction may be attained by adding socioeconomic variables to models.39Our study echoes the potential utility of incorporating common geriatric clinical features in routine clinical examination and disposition planning for older patients in acute settings.40 Hospitals may find it informative to undertake large-scale screening for geriatric syndromes including frailty, dementia, and delirium in all older adults admitted via the ED. When combined with other routinely collected variables such as demographics, AIS, and comorbidity data, this process may provide hospitals with information that will help define the acute needs of the local population and aid in the development of care pathways for the growing population of older adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all members of the acute teams in our hospital, without which this initiative would have not been possible. Licensed access to the NHS Foundation Trust’s information systems is also gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

Geriatric syndromes are multifactorial health conditions that affect older people and include dementia, delirium, impaired mobility, falls, frailty, poor nutrition, weight loss, incontinence, and difficulties with activities of daily living.1 These syndromes are highly prevalent among older patients admitted to acute-care hospitals2,3 and often add complexity to the clinical status of hospitalized older adults with multiple comorbid conditions.4 In the English National Health Service (NHS), the proportion of older people admitted to acute-care hospitals with geriatric syndromes has increased dramatically.5

The recognition and management of geriatric syndromes by hospitalists requires specific knowledge and skill sets.6 However, geriatricians are a scarce resource in many settings, including the NHS. A challenge for service evaluation and research is the generally poor capture of information about geriatric syndromes compared to specific comorbidities in discharge summaries and hospital coding.7 Steps are being taken in the NHS to address this issue, and in 2013 our center started the routine collection of data on clinical frailty, history of dementia (HoD) and acute confusional state (ACS) in all patients 75 years or older admitted nonelectively to the hospital.8The presence of geriatric syndromes in older inpatients is an important driver of adverse outcomes, particularly length of stay (LOS) and admission to institutional care.9 However, acute illness severity (AIS) is also an important determinant of poor outcomes in the inpatient population and may drive disproportionate changes in health status in the most vulnerable.10 Research studies with geriatric syndromes in acute settings have not been able to simultaneously consider AIS.11 In addition, comorbidity is not always associated with an increased number of geriatric syndromes.12

We aimed to study the association of geriatric syndromes such as frailty, HoD and ACS that are measured in routine clinical care with hospital outcomes (prolonged LOS, inpatient mortality, delayed discharge, institutionalization, and 30-day readmission), while controlling for demographics (age, gender), AIS, comorbidity, and discharging specialty (general medicine, geriatric medicine, surgery).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective observational study was conducted in a large tertiary university hospital in England with 1000 acute beds receiving more than 102,000 visits to the emergency department (ED) and admitting over 73,000 patients per year; among the latter, more than 12,000 are 75 years and older.

Sample

We analyzed all first nonelective inpatient episodes (ie, from ED admission to discharge) of people 75 years and older (all specialties) between the October 26, 2014 and the October 26, 2015. Data were obtained via the hospital’s information systems following the implementation of a new electronic patient record on October 26, 2014.

Patients’ Characteristics

The following anonymized variables were extracted:

- Age and gender

- AIS information is routinely collected in our ED using a Modified Early Warning Score (ED-MEWS). The components and scoring of ED-MEWS are shown in Table 1. Where more than 1 ED-MEWS was collected, the highest was used in the analyses.

- Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI, without age adjustment).13 The CCI is based on the discharge diagnoses, as coded according to WHO International Classification of Diseases, v 10 (ICD-10). The CCI was calculated retrospectively and would have not been available to clinicians early during the patients’ admission.

- Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS). The scoring of CFS is based on a global assessment of patients’ comorbidity symptoms, and their level of physical activity and dependency on activities of daily living, estimated to reflect the status immediately before the onset of the acute illness leading to hospitalization. The possible scores are: 1 (very fit), 2 (well), 3 (managing well), 4 (vulnerable), 5 (mildly frail), 6 (moderately frail), 7 (severely frail), 8 (very severely frail), and 9 (terminally ill) ().14 The use of the CFS in admissions of people 75 years and older was introduced in our center in 2013 under a local Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) scheme.8 The CQUIN required that all patients 75 years and older admitted to the hospital, via the ED, be screened for frailty using the CFS within 72 hours of admission. The admitting doctor usually scores the CFS on the electronic admission record, but it can also be completed by ED nurses or by nursing or therapy staff from the trust-wide Specialist Advice for the Frail Elderly team. Training on CFS scoring is provided to staff at a hiring orientation and at regular educational meetings. Permission to use CFS for clinical purposes was obtained from the principal investigator at Geriatric Medicine Research, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada.

- Cognitive variables were collected early during the admission in patients 75 years and older, thanks to a parallel local CQUIN scheme. The cognitive CQUIN variables are screening variables, not gold standard. The admission clerking is designed to clinically classify patients within 72 hours of admission into the following 3 mutually exclusive categories:

○ Known HoD (in the database: no = 0; yes = 1)

○ ACS, without HoD (in the database: no = 0; yes = 1)

○ Neither HoD nor ACS

- The cognitive CQUIN assessment does not intend to diagnose dementia in those who are not known to have it, but tries to separate the dementias that general practitioners (GPs) know from hospital-identified acute cognitive concerns that GPs may need to assess or investigate after discharge. The latter may include delirium and/or undiagnosed dementia.

- In our routine hospital practice, the initial cognitive assessment is performed by a clinician in the following fashion: if the patient is known to have dementia (ie, based on clinical history and/or chart review), the clinician selects the “known history of dementia” option in the admission navigator, and no further cognitive screening is conducted. If the patient has no known dementia, the clinician administers the 4-item Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT4): (1) age, (2) date of birth, (3) place, and (4) year, with impaired cognition indicated by an AMT4 of less than 4 and triggering the selection of “ACS without known HoD” option. If the AMT4 is normal, the clinician selects the “neither HoD nor ACS” option.

- Due to the service evaluation nature of our work, these measures could not be assessed for reliability within the electronic medical records system (eg, regarding sensitivity and specificity against a gold standard or inter-rater reliability).

- Discharged from geriatric medicine (no = 0; yes = 1). Every year, our hospital admits over 12,000 patients 75 years and older, of which 25% are managed by the Department of Medicine for the Elderly (DME). The DME specialist bed base consists of 5 core wards, which specialize in ward-based comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and are supported by dedicated nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and social work teams, as well as by readily available input from speech and language therapy, clinical nutrition, psychogeriatric, pharmacy and palliative care teams. Formal multidisciplinary team meetings occur at least twice weekly. A sixth specialist DME ward with a more acute perspective has been operational for 7 years; this ward was renamed the Frailty and Acute Medicine for the Elderly (FAME) ward in 2014 and has daily multidisciplinary team meetings. Although admission to FAME is through the ED, admission to core DME wards can occur from FAME (ie, within-DME transfer), via the ED, or from other inpatient specialty areas if older patients are perceived to be in high need of CGA after screening by the Specialist Advice for the Frail Elderly team. An audit in our center showed that up to 20% of patients discharged by DME were not initially admitted by DME, underscoring the significant role of core specialist DME wards in absorbing complex cases, especially from the general medical wards.8

- Discharged from general medicine (no = 0; yes = 1). In our setting, virtually all patients discharged by general medicine were first admitted by general medicine.8

- Discharged by a surgical specialty (no = 0; yes = 1)

Hospital Outcomes

The following anonymized variables were identified:

- LOS (days). Prolonged LOS was defined as 10 or more days (no = 0; yes = 1)

- Inpatient mortality (no = 0; yes = 1)

- Delayed discharge (no = 0; yes = 1). This was defined as the total LOS being at least 1 day longer than the LOS up to the last recorded clinically fit date. This date is used in NHS hospitals to indicate that the acute medical episode has finished and discharge-planning arrangements (often via social care providers) can commence.

- Institutionalization (no = 0; yes = 1). This was defined as the discharge destination being a care home, when a care home was not the usual place of residence.

- 30-day readmission (no = 0; yes = 1)

Statistical Analyses

Anonymized data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics (v 22, Armonk, New York) software. Descriptive statistics were given as count (with percentage) or mean (with standard deviation.

To avoid potential problems with multicollinearity in the multivariate regression models, the correlations among the predictor variables were checked using a correlation matrix of 2-sided Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients. Correlations of 0.50 or more were considered large.15,16

Because all outcomes in the study were binary, multivariate binary logistic regression models were computed. In these models, the odds ratio (OR) reflects the effect size of each predictor; 95% confidence intervals (CI) were requested for each OR. Predictors with P < 0.01 were considered as statistically significant. The classification performance of each logistic regression model was assessed calculating its area under the curve (AUC).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted after imputing missing data (SPSS multiple imputation procedure) and after fitting interaction terms between geriatric syndromes and discharge by geriatric medicine.

RESULTS

The initial database contained 12,282 nonelective admission and discharge episodes (all specialties) of patients 75 years and older between October 26, 2014 and October 26, 2015. Among those, 8202 (66.8%) were first episodes. Table 2 shows the sample descriptives, and Table 3 shows the breakdown of geriatric syndromes (single and multiple) in the total sample (n = 8282), including missing frailty data.

In the correlation matrix of 2-sided Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients, no correlations with large-effect size were found to suggest issues with multicollinearity; the largest correlation coefficients were between age and CFS (rho = 0.35), HoD and CFS (rho = 0.32), and CCI and CFS (rho = 0.26).

The results of the multivariate regression models are shown in Table 4. The best performing models were the ones for inpatient mortality (AUC = 0.80), followed by institutionalization (AUC = 0.76), and prolonged LOS (AUC = 0.71). After full adjustment, clinical frailty was an independent predictor of prolonged LOS, inpatient mortality, delayed discharge, and institutionalization. HoD was an independent predictor of prolonged LOS, delayed discharge, and institutionalization; and ACS was an independent predictor of prolonged LOS, delayed discharge, institutionalization, and 30-day readmission (Table 4). Results did not significantly change in sensitivity analyses conducted after multiple imputation of missing data and after inclusion of interaction terms (see Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Table

DISCUSSION

Our aim was to study the association of geriatric syndromes (measured in routine clinical care) with hospital outcomes. We found that geriatric syndromes such as clinical frailty, HoD, and ACS were strong independent predictors. Concerning prolonged LOS, delayed discharge, and institutionalization, geriatric syndromes had ORs that were greater than those of traditionally measured factors such as demographics, comorbidity and acute illness severity. Our findings add to the body of knowledge in this area because we accounted for the latter effects. Our experience shows that metrics on geriatric syndromes can be successfully collected in the routine hospital setting and add clear value to the prediction of operational outcomes. This may encourage other hospitals to do the same.

Our findings are consistent with suggestions that accounting for chronic conditions alone may be less informative than also accounting for the co-occurrence of geriatric syndromes.17 The focus of CFS is on the pre-admission level of physical activity and dependency on activities of daily living, and poorer scores may confer vulnerability to adverse outcomes due to reduced physiological reserve and ability to withstand acute stressors.18 Other studies have also found CFS to be a good predictor of inpatient outcomes,19-22 and it has been recommended as a possible means to identify vulnerable older adults in acute-care settings.23

HoD and ACS had independent effects beyond frailty, particularly in prolonging LOS, delaying discharge, and requiring institutionalization. Dementia prolongs LOS,24 and delirium prolongs hospitalization for persons with dementia.25 Older people with cognitive impairment may have an increased risk of acquiring new geriatric syndromes during hospitalization, particularly if it is prolonged.26 One study showed that the risk of poor functional recovery can be as high as 70% in complex delirious patients in hospital.27 All too often, delirium is neither benign nor reversible, with a significant proportion of patients not experiencing restoration ad integrum of cognition and function.28

Our results are consistent with observations that geriatric syndromes are associated with higher risk of institutionalization.29 It was interesting that female gender seemed to be an independent predictor of institutionalization, which is consistent with the results of a systematic review showing that the male-to-female ratio of admission rates ranged between 1 to 1.4 and 1 to 1.6.30

Discharge by general medicine appeared to be associated with a lower likelihood of prolonged LOS, and discharge by geriatric medicine seemed to be associated with a higher likelihood of delayed discharge and institutionalization. Unsurprisingly, geriatric medicine wards tend to absorb the most complex cases, often with complex discharge planning needs.8 In that light, CGA in geriatric wards may not be associated with reduced LOS (and it is possible that the LOS of complex patients might have been higher in nongeriatric wards). In addition, inpatient CGA increases frail patients’ likelihood of survival.31

Our study suggests that routinely collected metrics on frailty, HoD and ACS may be helpful to better adapt hospital care to the real requirements of aged people. The proportion of older people admitted to acute hospitals with geriatric syndromes continues to increase5 and geriatricians are a scarce resource. It will be increasingly important to upskill nongeriatric hospitalists in the recognition and management of geriatric syndromes. Frail older people are becoming the core business of acute hospitals,32 making geriatrics “too important to be left to geriatricians.”33 Therefore, easily collected metrics on geriatric syndromes may help nongeriatricians identify these syndromes and address them early during admission.

Our study has important limitations. Firstly, geriatric syndromes were not identified with gold-standard measures. For example, ACS in the absence of known dementia should be seen only as a surrogate for delirium. ACS as a proxy measure is likely to underestimate the diagnosis of delirium, because the hypoactive type is commonly missed without valid measures. In addition, a patient with delirium superimposed upon dementia would have been coded as a ‘known dementia.’ The geriatric syndromes’ measures could not be assessed for reliability within the electronic medical records system (eg, regarding sensitivity and specificity against a gold standard, or interrater reliability).

About the potential limitations of CFS, there have been concerns that an interobserver discrepancy in CFS scoring may occur between health professionals. However, 1 study investigated the interrater reliability of CFS between clinicians in 107 community-dwelling older adults 75 years and older, finding a substantial agreement with a weighted

Another limitation of our study is that we treated geriatric syndromes and the other predictors in the models as independent variables. However, many of the factors may be interrelated, and they present simultaneously in many patients. Indeed, the bivariate correlation between CFS and HoD was of moderate strength, because worsening cognition should score higher on CFS according to the scoring protocol. As expected, there was also a medium-sized correlation between CFS and CCI. It has been suggested that physical and cognitive frailty may be more informative as a single complex phenotype.36 Indeed, the problems of old age tend to come as a package.37

For 30-day readmission, the AUC of the model was small, suggesting the existence of unmeasured explanatory variables. For example, although our results agree that AIS and chronic illness predict readmission,38 the latter still remains an elusive outcome, and a more accurate prediction may be attained by adding socioeconomic variables to models.39Our study echoes the potential utility of incorporating common geriatric clinical features in routine clinical examination and disposition planning for older patients in acute settings.40 Hospitals may find it informative to undertake large-scale screening for geriatric syndromes including frailty, dementia, and delirium in all older adults admitted via the ED. When combined with other routinely collected variables such as demographics, AIS, and comorbidity data, this process may provide hospitals with information that will help define the acute needs of the local population and aid in the development of care pathways for the growing population of older adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all members of the acute teams in our hospital, without which this initiative would have not been possible. Licensed access to the NHS Foundation Trust’s information systems is also gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

1. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780-791. PubMed

2. Lakhan P, Jones M, Wilson A, Courtney M, Hirdes J, Gray LC. A prospective cohort study of geriatric syndromes among older medical patients admitted to acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2001-2008. PubMed

3. Flood KL, Rohlfing A, Le CV, Carr DB, Rich MW. Geriatric syndromes in elderly patients admitted to an inpatient cardiology ward. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:394-400. PubMed

4. Clerencia-Sierra M, Calderon-Larranaga A, Martinez-Velilla N, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in hospitalized older patients: associations among chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132909. PubMed

5. Soong J, Poots AJ, Scott S, et al. Quantifying the prevalence of frailty in English hospitals. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008456. PubMed

6. Warshaw GA, Bragg EJ, Fried LP, Hall WJ. Which patients benefit the most from a geriatrician’s care? Consensus among directors of geriatrics academic programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1796-1801. PubMed

7. Ugboma I, Syddall HE, Cox V, Cooper C, Briggs R, Sayer AA. Coding geriatric syndromes: How good are we? CME J Geriatr Med. 2008;10:34-36. PubMed

8. Wallis SJ, Wall J, Biram RW, Romero-Ortuno R. Association of the clinical frailty scale with hospital outcomes. QJM. 2015;108:943-949. PubMed

9. Anpalahan M, Gibson SJ. Geriatric syndromes as predictors of adverse outcomes of hospitalization. Intern Med J. 2008;38:16-23. PubMed

10. Cournane S, Byrne D, O’Riordan D, Fitzgerald B, Silke B. Chronic disabling disease--impact on outcomes and costs in emergency medical admissions. QJM. 2015;108:387-396. PubMed

11. Soong J, Poots AJ, Scott S, Donald K, Bell D. Developing and validating a risk prediction model for acute care based on frailty syndromes. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008457. PubMed

12. Vetrano DL, Foebel AD, Marengoni A, et al. Chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes: The different weight of comorbidity. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;27:62-67. PubMed

13. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. PubMed

14. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489-495. PubMed

15. Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141:2-18. PubMed

16. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

17. Koroukian SM, Schiltz N, Warner DF, et al. Combinations of chronic conditions, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes that predict health outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:630-637. PubMed

18. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752-762. PubMed

19. Romanowski KS, Barsun A, Pamlieri TL, Greenhalgh DG, Sen S. Frailty score on admission predicts outcomes in elderly burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2015;36:1-6. PubMed

20. Ritt M, Schwarz C, Kronawitter V, et al. Analysis of Rockwood et al’s clinical frailty scale and Fried et al’s frailty phenotype as predictors of mortality and other clinical outcomes in older patients who were admitted to a geriatric ward. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:1043-1048. PubMed

21. Murali-Krishnan R, Iqbal J, Rowe R, et al. Impact of frailty on outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective cohort study. Open Heart. 2015;2:e000294. PubMed

22. Kang L, Zhang SY, Zhu WL, et al. Is frailty associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome? J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12:662-667.

23. Conroy S, Chikura G. Emergency care for frail older people-urgent AND important-but what works? Age Ageing. 2015;44:724-725. PubMed

24. Connolly S, O’Shea E. The impact of dementia on length of stay in acute hospitals in Ireland. Dementia (London). 2015;14:650-658. PubMed

25. Fick DM, Steis MR, Waller JL, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia is associated with prolonged length of stay and poor outcomes in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:500-505. PubMed

26. Mecocci P, von Strauss E, Cherubini A, et al. Cognitive impairment is the major risk factor for development of geriatric syndromes during hospitalization: results from the GIFA study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20:262-269. PubMed

27. Dasgupta M, Brymer C. Poor functional recovery after delirium is associated with other geriatric syndromes and additional illnesses. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:793-802. PubMed

28. Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, et al. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:30-39.

29. Wang SY, Shamliyan TA, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Not just specific diseases: systematic review of the association of geriatric syndromes with hospitalization or nursing home admission. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57:16-26. PubMed

30. Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Gender differences in predictors of nursing home placement in the elderly: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:1015-1025. PubMed

31. Ellis G, Whitehead MA, O’Neill D, Langhorne P, Robinson D. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD006211. PubMed

32. HSJ/SERCO. Commission on Hospital Care for Frail Older People. Main Report. Available at: http://www.hsj.co.uk/Journals/2014/11/18/l/q/r/HSJ141121_FRAILOLDERPEOPLE_LO-RES.pdf. 2014.

33. Coni N. The unlikely geriatricians. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:587-589. PubMed

34. Islam A. Gait variability is an independent marker of frailty. Electronic thesis and dissertation repository, the University of Western Ontario, 2012. Available at: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/558. Accessed July 23, 2016.

35. Grossman D, Rootenberg M, Perri GA, et al. Enhancing communication in end-of-life care: a clinical tool translating between the Clinical Frailty Scale and the Palliative Performance Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1562-1567. PubMed

36. Panza F, Seripa D, Solfrizzi V, et al. Targeting cognitive frailty: clinical and neurobiological roadmap for a single complex phenotype. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:793-813. PubMed

37. Fontana L, Kennedy BK, Longo VD, Seals D, Melov S. Medical research: treat ageing. Nature. 2014;511:405-407. PubMed

38. Conway R, Byrne D, O’Riordan D, Silke B. Emergency readmissions are substantially determined by acute illness severity and chronic debilitating illness: a single centre cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:12-17. PubMed

39. Cournane S, Byrne D, Conway R, O’Riordan D, Coveney S, Silke B. Social deprivation and hospital admission rates, length of stay and readmissions in emergency medical admissions. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:766-771. PubMed

40. Costa AP, Hirdes JP, Heckman GA, et al. Geriatric syndromes predict postdischarge outcomes among older emergency department patients: findings from the interRAI Multinational Emergency Department Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:422-433. PubMed

1. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780-791. PubMed

2. Lakhan P, Jones M, Wilson A, Courtney M, Hirdes J, Gray LC. A prospective cohort study of geriatric syndromes among older medical patients admitted to acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2001-2008. PubMed

3. Flood KL, Rohlfing A, Le CV, Carr DB, Rich MW. Geriatric syndromes in elderly patients admitted to an inpatient cardiology ward. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:394-400. PubMed

4. Clerencia-Sierra M, Calderon-Larranaga A, Martinez-Velilla N, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in hospitalized older patients: associations among chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132909. PubMed

5. Soong J, Poots AJ, Scott S, et al. Quantifying the prevalence of frailty in English hospitals. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008456. PubMed

6. Warshaw GA, Bragg EJ, Fried LP, Hall WJ. Which patients benefit the most from a geriatrician’s care? Consensus among directors of geriatrics academic programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1796-1801. PubMed

7. Ugboma I, Syddall HE, Cox V, Cooper C, Briggs R, Sayer AA. Coding geriatric syndromes: How good are we? CME J Geriatr Med. 2008;10:34-36. PubMed

8. Wallis SJ, Wall J, Biram RW, Romero-Ortuno R. Association of the clinical frailty scale with hospital outcomes. QJM. 2015;108:943-949. PubMed

9. Anpalahan M, Gibson SJ. Geriatric syndromes as predictors of adverse outcomes of hospitalization. Intern Med J. 2008;38:16-23. PubMed

10. Cournane S, Byrne D, O’Riordan D, Fitzgerald B, Silke B. Chronic disabling disease--impact on outcomes and costs in emergency medical admissions. QJM. 2015;108:387-396. PubMed

11. Soong J, Poots AJ, Scott S, Donald K, Bell D. Developing and validating a risk prediction model for acute care based on frailty syndromes. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008457. PubMed

12. Vetrano DL, Foebel AD, Marengoni A, et al. Chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes: The different weight of comorbidity. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;27:62-67. PubMed

13. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. PubMed

14. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489-495. PubMed

15. Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141:2-18. PubMed

16. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

17. Koroukian SM, Schiltz N, Warner DF, et al. Combinations of chronic conditions, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes that predict health outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:630-637. PubMed

18. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752-762. PubMed

19. Romanowski KS, Barsun A, Pamlieri TL, Greenhalgh DG, Sen S. Frailty score on admission predicts outcomes in elderly burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2015;36:1-6. PubMed

20. Ritt M, Schwarz C, Kronawitter V, et al. Analysis of Rockwood et al’s clinical frailty scale and Fried et al’s frailty phenotype as predictors of mortality and other clinical outcomes in older patients who were admitted to a geriatric ward. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:1043-1048. PubMed

21. Murali-Krishnan R, Iqbal J, Rowe R, et al. Impact of frailty on outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective cohort study. Open Heart. 2015;2:e000294. PubMed

22. Kang L, Zhang SY, Zhu WL, et al. Is frailty associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome? J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12:662-667.

23. Conroy S, Chikura G. Emergency care for frail older people-urgent AND important-but what works? Age Ageing. 2015;44:724-725. PubMed

24. Connolly S, O’Shea E. The impact of dementia on length of stay in acute hospitals in Ireland. Dementia (London). 2015;14:650-658. PubMed

25. Fick DM, Steis MR, Waller JL, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia is associated with prolonged length of stay and poor outcomes in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:500-505. PubMed

26. Mecocci P, von Strauss E, Cherubini A, et al. Cognitive impairment is the major risk factor for development of geriatric syndromes during hospitalization: results from the GIFA study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20:262-269. PubMed

27. Dasgupta M, Brymer C. Poor functional recovery after delirium is associated with other geriatric syndromes and additional illnesses. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:793-802. PubMed

28. Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, et al. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:30-39.

29. Wang SY, Shamliyan TA, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Not just specific diseases: systematic review of the association of geriatric syndromes with hospitalization or nursing home admission. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57:16-26. PubMed

30. Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Gender differences in predictors of nursing home placement in the elderly: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:1015-1025. PubMed

31. Ellis G, Whitehead MA, O’Neill D, Langhorne P, Robinson D. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD006211. PubMed

32. HSJ/SERCO. Commission on Hospital Care for Frail Older People. Main Report. Available at: http://www.hsj.co.uk/Journals/2014/11/18/l/q/r/HSJ141121_FRAILOLDERPEOPLE_LO-RES.pdf. 2014.

33. Coni N. The unlikely geriatricians. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:587-589. PubMed

34. Islam A. Gait variability is an independent marker of frailty. Electronic thesis and dissertation repository, the University of Western Ontario, 2012. Available at: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/558. Accessed July 23, 2016.

35. Grossman D, Rootenberg M, Perri GA, et al. Enhancing communication in end-of-life care: a clinical tool translating between the Clinical Frailty Scale and the Palliative Performance Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1562-1567. PubMed

36. Panza F, Seripa D, Solfrizzi V, et al. Targeting cognitive frailty: clinical and neurobiological roadmap for a single complex phenotype. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:793-813. PubMed

37. Fontana L, Kennedy BK, Longo VD, Seals D, Melov S. Medical research: treat ageing. Nature. 2014;511:405-407. PubMed

38. Conway R, Byrne D, O’Riordan D, Silke B. Emergency readmissions are substantially determined by acute illness severity and chronic debilitating illness: a single centre cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:12-17. PubMed

39. Cournane S, Byrne D, Conway R, O’Riordan D, Coveney S, Silke B. Social deprivation and hospital admission rates, length of stay and readmissions in emergency medical admissions. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:766-771. PubMed

40. Costa AP, Hirdes JP, Heckman GA, et al. Geriatric syndromes predict postdischarge outcomes among older emergency department patients: findings from the interRAI Multinational Emergency Department Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:422-433. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine