User login

Veterans have a high burden of digestive diseases, and gastroenterologists are needed for the diagnosis and management of these conditions.1-4 According to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) office, the physician specialties with the greatest shortages are psychiatry, primary care, and gastroenterology.5 The VHA estimates it must hire 70 new gastroenterologists annually between fiscal years 2023 and 2027 to provide timely digestive care.5

Filling these positions will be increasingly difficult as competition for gastroenterologists is fierce. A recent Merritt Hawkins review states, “Gastroenterologists were the most in-demand type of provider during the 2022 review period.”6 In 2022, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was reported to be $561,375.7 Currently, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has an aggregate annual pay limit of $400,000 for all federal employees and cannot compete based on salary alone.

Retention of existing VA gastroenterologists also is challenging. The WMC has reported that 21.6% of VA gastroenterologists are eligible to retire, and in 2021, 8.2% left the VA to retire or seek non-VA positions.5 While not specific to the VA, a survey of practicing gastroenterologists conducted by the American College of Gastroenterology found a 49% burnout rate among respondents.8 Factors contributing to burnout at all career stages included administrative nonclinical work and a lack of clinical support staff.8 Burnout is also linked with higher rates of medical errors, interpersonal conflicts, and patient dissatisfaction. Burnout is more common among those with an innate strong sense of purpose and responsibility for their patients, characteristics we have observed in our VA colleagues.9

As members of the Section Chief Subcommittee of the VA Gastroenterology Field Advisory Board (GI FAB), we are passionate about providing outstanding gastroenterology care to US veterans, and we are alarmed at the struggles we are observing with recruiting and retaining a qualified national gastroenterology physician workforce. As such, we set out to survey the VA gastroenterology section chief community to gain insights into recruitment and retention challenges they have faced and identify potential solutions to these problems.

Methods

The GI FAB Section Chief Subcommittee developed a survey on gastroenterologist recruitment and retention using Microsoft Forms (Appendix). A link to the survey, which included 11 questions about facility location, current vacancies, and free text responses on barriers to recruitment and retention and potential solutions, was sent via email to all gastroenterology section chiefs on the National Gastroenterology and Hepatology Program Office’s email list of section chiefs on January 31, 2023. A reminder to complete the survey was sent to all section chiefs on February 8, 2023. Survey responses were aggregated and analyzed by the authors using descriptive statistics.

Results

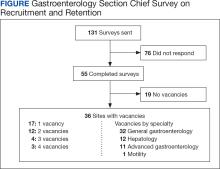

The VA gastroenterologist recruitment and retention survey was emailed to 131 gastroenterology section chiefs and completed by 55 respondents (42%) (Figure). Of the responding section chiefs, 36 (65%) reported gastroenterologist vacancies at their facilities. Seventeen respondents (47%) reported a single vacancy, 12 (33%) reported 2 vacancies, 4 (11%) reported 3 vacancies, and 3 (8%) reported 4 vacancies. Of the sites with reported vacancies, 32 (89%) reported a need for a general gastroenterologist, 12 (33%) reported a need for a hepatologist, 11 (31%) reported a need for an advanced endoscopist, 9 (25%) reported a need for a gastroenterologist with specialized expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases, and 1 (3%) reported a need for a gastrointestinal motility specialist.

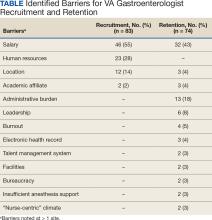

Numerous barriers to the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists were reported. Given the large number of respondents that reported a unique barrier (ie, being the only respondents to report the barrier), a decision was made to include only barriers to recruitment and retention that were reported by at least 2 sites (Table). While there were some common themes, the reported barriers to retention differed from those to recruitment. The most reported barriers to recruitment were 46 respondents who noted salary, 23 reported human resources-related challenges, and 12 reported location. Respondents also noted various retention barriers, including 32 respondents who reported salary barriers; 13 reported administrative burden barriers, 6 reported medical center leadership, and 4 reported burnout.

Survey respondents provided multiple recommendations on how the VA can best support the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists. The most frequent recommendations were to increase financial compensation by increasing the current aggregate salary cap to > $400,000, increasing the use of recruitment and retention incentives, and ensuring that gastroenterology is on the national Educational Debt Reduction Program (EDRP) list, which facilitates student loan repayment. It was recommended that a third-party company assist with hiring to overcome perceived issues with human resources. Additionally, there were multiple recommendations for improving administrative and clinical support. These included mandating how many support staff should be assigned to each gastroenterologist and providing best practice recommendations for support staff so that gastroenterologists can focus on physician-level work. Recommendations also included having a dedicated gastroenterology practice manager, nurse care coordinators, a colorectal cancer screening/surveillance coordinator, sufficient medical support assistants, and quality improvement personnel tracking ongoing professional practice evaluation data. Survey respondents also highlighted specific suggestions for recruiting recent graduates. These included offering a 4-day work week, as recent graduates place a premium on work-life balance, and ensuring gastroenterologists have individual offices. One respondent commented that gastroenterology fellows seeing VA gastroenterology attendings in cramped, shared offices, contrasted with private practice gastroenterologists in large private offices, may contribute to choosing private practice over joining the VA.

Discussion

Gastroenterology is currently listed by VHA WMC as 1 of the top 3 medical specialties in the VA with the most physician shortages.5 Working as a physician in the VA has long been recognized to have many benefits. First and foremost, many physicians are motivated by the VA mission to serve veterans, as this offers personal fulfillment and other intangible benefits. In addition, the VA can provide work-life balance, which is often not possible in fee-for-service settings, with patient panels and call volumes typically lower than in comparable private hospital settings. Moreover, VA physicians have outstanding teaching opportunities, as the VA is the largest supporter of medical education, with postgraduate trainees rotating through > 150 VA medical centers. Likewise, the VA offers a variety of student loan repayment programs (eg, the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program and the EDRP). The VA offers research funding such as the Cooperative Studies Programs or program project funding, and rewards in parallel with the National Institute of Health (eg, career development awards, or merit review awards) and other grants. VA researchers have conducted many landmark studies that continue to shape the practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. From the earliest studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of screening colonoscopy, to the largest ongoing clinical trial in US history to assess the effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) vs screening colonoscopy.10-12 The VA has also led the field in the study of gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C treatment, and liver cancer screening.13-15 VA physicians also benefit from participation in the Federal Employee Retirement System, including its pension system.

These benefits apply to all medical specialties, making the VA a potentially appealing workplace for gastroenterologists. However, recent trends indicate that recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists is increasingly challenging, as the VA gastroenterology workforce grew by 5.0% in fiscal year (FY) 2020 and 1.8% in FY 2021. However, it was on track to end FY 2022 with a loss (-1.1%).5 It must be noted that this trend is not limited to the VA, and the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis predicts that gastroenterology will remain among the highest projected specialty shortages. Driven by increased demand for digestive health care services, more physicians nearing traditional retirement age, and substantially higher rates of burnout after the COVID-19 pandemic.16 All these factors are likely to result in an increasingly competitive market for gastroenterology, highlight the growing differences between VA and non-VA positions, and may augment the impact of differences for the individual gastroenterologist weighing employment options within and outside the VA.

The survey responses from VA gastroenterology section chiefs help identify potential impediments to the successful recruitment and retention in the specialty. Noncompetitive salary was the most significant barrier to the successful recruitment of gastroenterologists, identified by 46 of 55 respondents. According to a 2022 Medical Group Management Association report, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was $561,375.7 According to internal VA WMC data, the median 2022 VA gastroenterologist salary ranged between $287,976 and $346,435, depending on facility complexity level, excluding recruitment, retention, or relocation bonuses; performance pay; or cash awards. The current aggregate salary cap of $400,000 indicates that the VHA will likely be increasingly noncompetitive in the coming years unless novel pay authorizations are implemented.

Suboptimal human resources were the second most commonly cited impediment to recruiting gastroenterologists. Many section chiefs expressed frustration with the inefficient and slow administrative process of onboarding new gastroenterologists, which may take many months and not infrequently results in losing candidates to competing entities. While this issue is specific to recruitment, recurring and long-standing vacancies can increase work burdens, complicate logistics for remaining faculty, and may also negatively impact retention. One potential opportunity to improve VHA competitiveness is to streamline the administrative component of recruitment and optimize human resources support. The use of a third-party hiring company also should be considered.

Survey responses also indicated that administrative burden and insufficient support staff were significant retention challenges. Several respondents described a lack of efficient endoscopy workflow and delegation of simple administrative tasks to gastroenterologists as more likely in units without proper task distribution. Importantly, these shortcomings occur at the expense of workload-generating activities and career-enhancing opportunities.

While burnout rates among VA gastroenterologists have not been documented systematically, they likely correlate with workplace frustration and jeopardizegastroenterologist retention. Successful retention of gastroenterologists as highly trained medical professionals is more likely in workplaces that are vertically organized, efficient, and use physicians at the top of their skill level.

Conclusions

The VA offers the opportunity for a rewarding lifelong career in gastroenterology. The fulfillment of serving veterans, teaching future health care leaders, performing impactful research, and having job security is invaluable. Despite the tremendous benefits, this survey supports improving VA recruitment and retention strategies for the high-demand gastroenterology specialty. Improved salary parity is needed for workforce maintenance and recruitment, as is improved administrative and clinical support to maintain the high level of care our veterans deserve.

1. Shin A, Xu H, Imperiale TF. The prevalence, humanistic burden, and health care impact of irritable bowel syndrome among united states veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):1061-1069.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.08.005.

2. Kent KG. Prevalence of gastrointestinal disease in US military veterans under outpatient care at the veterans health administration. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211049112. doi:10.1177/20503121211049112

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

5. VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/WMCPortal/WFP/Documents/Reports/VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint FY 23-27.pdf [Source not verified]

6. AMN Healthcare. 2022 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www1.amnhealthcare.com/l/123142/2022-07-13/q6ywxg/123142/1657737392vyuONaZZ/mha2022incentivesurgraphic.pdf

7. Medical Group Management Association. MGMA DataDive Provider Compensation Data. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.mgma.com/datadive/provider-compensation

8. Anderson JC, Bilal M, Burke CA, et al. Burnout among US gastroenterologists and fellows in training: identifying contributing factors and offering solutions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(10):1063-1069. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001781

9. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311-317. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

10. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans affairs cooperative study group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):162-168. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430301

11. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):555-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010328

12. Robertson DJ, Dominitz JA, Beed A, et al. Baseline features and reasons for nonparticipation in the colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test in reducing mortality from colorectal cancer (CONFIRM) study, a colorectal cancer screening trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321730. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21730

13. Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811424

14. Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):32-39. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.027

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans affairs cooperative studies program (CSP). CSP #2023. Updated July 2022. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

16. US Health Resources & Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

Veterans have a high burden of digestive diseases, and gastroenterologists are needed for the diagnosis and management of these conditions.1-4 According to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) office, the physician specialties with the greatest shortages are psychiatry, primary care, and gastroenterology.5 The VHA estimates it must hire 70 new gastroenterologists annually between fiscal years 2023 and 2027 to provide timely digestive care.5

Filling these positions will be increasingly difficult as competition for gastroenterologists is fierce. A recent Merritt Hawkins review states, “Gastroenterologists were the most in-demand type of provider during the 2022 review period.”6 In 2022, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was reported to be $561,375.7 Currently, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has an aggregate annual pay limit of $400,000 for all federal employees and cannot compete based on salary alone.

Retention of existing VA gastroenterologists also is challenging. The WMC has reported that 21.6% of VA gastroenterologists are eligible to retire, and in 2021, 8.2% left the VA to retire or seek non-VA positions.5 While not specific to the VA, a survey of practicing gastroenterologists conducted by the American College of Gastroenterology found a 49% burnout rate among respondents.8 Factors contributing to burnout at all career stages included administrative nonclinical work and a lack of clinical support staff.8 Burnout is also linked with higher rates of medical errors, interpersonal conflicts, and patient dissatisfaction. Burnout is more common among those with an innate strong sense of purpose and responsibility for their patients, characteristics we have observed in our VA colleagues.9

As members of the Section Chief Subcommittee of the VA Gastroenterology Field Advisory Board (GI FAB), we are passionate about providing outstanding gastroenterology care to US veterans, and we are alarmed at the struggles we are observing with recruiting and retaining a qualified national gastroenterology physician workforce. As such, we set out to survey the VA gastroenterology section chief community to gain insights into recruitment and retention challenges they have faced and identify potential solutions to these problems.

Methods

The GI FAB Section Chief Subcommittee developed a survey on gastroenterologist recruitment and retention using Microsoft Forms (Appendix). A link to the survey, which included 11 questions about facility location, current vacancies, and free text responses on barriers to recruitment and retention and potential solutions, was sent via email to all gastroenterology section chiefs on the National Gastroenterology and Hepatology Program Office’s email list of section chiefs on January 31, 2023. A reminder to complete the survey was sent to all section chiefs on February 8, 2023. Survey responses were aggregated and analyzed by the authors using descriptive statistics.

Results

The VA gastroenterologist recruitment and retention survey was emailed to 131 gastroenterology section chiefs and completed by 55 respondents (42%) (Figure). Of the responding section chiefs, 36 (65%) reported gastroenterologist vacancies at their facilities. Seventeen respondents (47%) reported a single vacancy, 12 (33%) reported 2 vacancies, 4 (11%) reported 3 vacancies, and 3 (8%) reported 4 vacancies. Of the sites with reported vacancies, 32 (89%) reported a need for a general gastroenterologist, 12 (33%) reported a need for a hepatologist, 11 (31%) reported a need for an advanced endoscopist, 9 (25%) reported a need for a gastroenterologist with specialized expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases, and 1 (3%) reported a need for a gastrointestinal motility specialist.

Numerous barriers to the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists were reported. Given the large number of respondents that reported a unique barrier (ie, being the only respondents to report the barrier), a decision was made to include only barriers to recruitment and retention that were reported by at least 2 sites (Table). While there were some common themes, the reported barriers to retention differed from those to recruitment. The most reported barriers to recruitment were 46 respondents who noted salary, 23 reported human resources-related challenges, and 12 reported location. Respondents also noted various retention barriers, including 32 respondents who reported salary barriers; 13 reported administrative burden barriers, 6 reported medical center leadership, and 4 reported burnout.

Survey respondents provided multiple recommendations on how the VA can best support the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists. The most frequent recommendations were to increase financial compensation by increasing the current aggregate salary cap to > $400,000, increasing the use of recruitment and retention incentives, and ensuring that gastroenterology is on the national Educational Debt Reduction Program (EDRP) list, which facilitates student loan repayment. It was recommended that a third-party company assist with hiring to overcome perceived issues with human resources. Additionally, there were multiple recommendations for improving administrative and clinical support. These included mandating how many support staff should be assigned to each gastroenterologist and providing best practice recommendations for support staff so that gastroenterologists can focus on physician-level work. Recommendations also included having a dedicated gastroenterology practice manager, nurse care coordinators, a colorectal cancer screening/surveillance coordinator, sufficient medical support assistants, and quality improvement personnel tracking ongoing professional practice evaluation data. Survey respondents also highlighted specific suggestions for recruiting recent graduates. These included offering a 4-day work week, as recent graduates place a premium on work-life balance, and ensuring gastroenterologists have individual offices. One respondent commented that gastroenterology fellows seeing VA gastroenterology attendings in cramped, shared offices, contrasted with private practice gastroenterologists in large private offices, may contribute to choosing private practice over joining the VA.

Discussion

Gastroenterology is currently listed by VHA WMC as 1 of the top 3 medical specialties in the VA with the most physician shortages.5 Working as a physician in the VA has long been recognized to have many benefits. First and foremost, many physicians are motivated by the VA mission to serve veterans, as this offers personal fulfillment and other intangible benefits. In addition, the VA can provide work-life balance, which is often not possible in fee-for-service settings, with patient panels and call volumes typically lower than in comparable private hospital settings. Moreover, VA physicians have outstanding teaching opportunities, as the VA is the largest supporter of medical education, with postgraduate trainees rotating through > 150 VA medical centers. Likewise, the VA offers a variety of student loan repayment programs (eg, the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program and the EDRP). The VA offers research funding such as the Cooperative Studies Programs or program project funding, and rewards in parallel with the National Institute of Health (eg, career development awards, or merit review awards) and other grants. VA researchers have conducted many landmark studies that continue to shape the practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. From the earliest studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of screening colonoscopy, to the largest ongoing clinical trial in US history to assess the effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) vs screening colonoscopy.10-12 The VA has also led the field in the study of gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C treatment, and liver cancer screening.13-15 VA physicians also benefit from participation in the Federal Employee Retirement System, including its pension system.

These benefits apply to all medical specialties, making the VA a potentially appealing workplace for gastroenterologists. However, recent trends indicate that recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists is increasingly challenging, as the VA gastroenterology workforce grew by 5.0% in fiscal year (FY) 2020 and 1.8% in FY 2021. However, it was on track to end FY 2022 with a loss (-1.1%).5 It must be noted that this trend is not limited to the VA, and the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis predicts that gastroenterology will remain among the highest projected specialty shortages. Driven by increased demand for digestive health care services, more physicians nearing traditional retirement age, and substantially higher rates of burnout after the COVID-19 pandemic.16 All these factors are likely to result in an increasingly competitive market for gastroenterology, highlight the growing differences between VA and non-VA positions, and may augment the impact of differences for the individual gastroenterologist weighing employment options within and outside the VA.

The survey responses from VA gastroenterology section chiefs help identify potential impediments to the successful recruitment and retention in the specialty. Noncompetitive salary was the most significant barrier to the successful recruitment of gastroenterologists, identified by 46 of 55 respondents. According to a 2022 Medical Group Management Association report, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was $561,375.7 According to internal VA WMC data, the median 2022 VA gastroenterologist salary ranged between $287,976 and $346,435, depending on facility complexity level, excluding recruitment, retention, or relocation bonuses; performance pay; or cash awards. The current aggregate salary cap of $400,000 indicates that the VHA will likely be increasingly noncompetitive in the coming years unless novel pay authorizations are implemented.

Suboptimal human resources were the second most commonly cited impediment to recruiting gastroenterologists. Many section chiefs expressed frustration with the inefficient and slow administrative process of onboarding new gastroenterologists, which may take many months and not infrequently results in losing candidates to competing entities. While this issue is specific to recruitment, recurring and long-standing vacancies can increase work burdens, complicate logistics for remaining faculty, and may also negatively impact retention. One potential opportunity to improve VHA competitiveness is to streamline the administrative component of recruitment and optimize human resources support. The use of a third-party hiring company also should be considered.

Survey responses also indicated that administrative burden and insufficient support staff were significant retention challenges. Several respondents described a lack of efficient endoscopy workflow and delegation of simple administrative tasks to gastroenterologists as more likely in units without proper task distribution. Importantly, these shortcomings occur at the expense of workload-generating activities and career-enhancing opportunities.

While burnout rates among VA gastroenterologists have not been documented systematically, they likely correlate with workplace frustration and jeopardizegastroenterologist retention. Successful retention of gastroenterologists as highly trained medical professionals is more likely in workplaces that are vertically organized, efficient, and use physicians at the top of their skill level.

Conclusions

The VA offers the opportunity for a rewarding lifelong career in gastroenterology. The fulfillment of serving veterans, teaching future health care leaders, performing impactful research, and having job security is invaluable. Despite the tremendous benefits, this survey supports improving VA recruitment and retention strategies for the high-demand gastroenterology specialty. Improved salary parity is needed for workforce maintenance and recruitment, as is improved administrative and clinical support to maintain the high level of care our veterans deserve.

Veterans have a high burden of digestive diseases, and gastroenterologists are needed for the diagnosis and management of these conditions.1-4 According to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) office, the physician specialties with the greatest shortages are psychiatry, primary care, and gastroenterology.5 The VHA estimates it must hire 70 new gastroenterologists annually between fiscal years 2023 and 2027 to provide timely digestive care.5

Filling these positions will be increasingly difficult as competition for gastroenterologists is fierce. A recent Merritt Hawkins review states, “Gastroenterologists were the most in-demand type of provider during the 2022 review period.”6 In 2022, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was reported to be $561,375.7 Currently, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has an aggregate annual pay limit of $400,000 for all federal employees and cannot compete based on salary alone.

Retention of existing VA gastroenterologists also is challenging. The WMC has reported that 21.6% of VA gastroenterologists are eligible to retire, and in 2021, 8.2% left the VA to retire or seek non-VA positions.5 While not specific to the VA, a survey of practicing gastroenterologists conducted by the American College of Gastroenterology found a 49% burnout rate among respondents.8 Factors contributing to burnout at all career stages included administrative nonclinical work and a lack of clinical support staff.8 Burnout is also linked with higher rates of medical errors, interpersonal conflicts, and patient dissatisfaction. Burnout is more common among those with an innate strong sense of purpose and responsibility for their patients, characteristics we have observed in our VA colleagues.9

As members of the Section Chief Subcommittee of the VA Gastroenterology Field Advisory Board (GI FAB), we are passionate about providing outstanding gastroenterology care to US veterans, and we are alarmed at the struggles we are observing with recruiting and retaining a qualified national gastroenterology physician workforce. As such, we set out to survey the VA gastroenterology section chief community to gain insights into recruitment and retention challenges they have faced and identify potential solutions to these problems.

Methods

The GI FAB Section Chief Subcommittee developed a survey on gastroenterologist recruitment and retention using Microsoft Forms (Appendix). A link to the survey, which included 11 questions about facility location, current vacancies, and free text responses on barriers to recruitment and retention and potential solutions, was sent via email to all gastroenterology section chiefs on the National Gastroenterology and Hepatology Program Office’s email list of section chiefs on January 31, 2023. A reminder to complete the survey was sent to all section chiefs on February 8, 2023. Survey responses were aggregated and analyzed by the authors using descriptive statistics.

Results

The VA gastroenterologist recruitment and retention survey was emailed to 131 gastroenterology section chiefs and completed by 55 respondents (42%) (Figure). Of the responding section chiefs, 36 (65%) reported gastroenterologist vacancies at their facilities. Seventeen respondents (47%) reported a single vacancy, 12 (33%) reported 2 vacancies, 4 (11%) reported 3 vacancies, and 3 (8%) reported 4 vacancies. Of the sites with reported vacancies, 32 (89%) reported a need for a general gastroenterologist, 12 (33%) reported a need for a hepatologist, 11 (31%) reported a need for an advanced endoscopist, 9 (25%) reported a need for a gastroenterologist with specialized expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases, and 1 (3%) reported a need for a gastrointestinal motility specialist.

Numerous barriers to the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists were reported. Given the large number of respondents that reported a unique barrier (ie, being the only respondents to report the barrier), a decision was made to include only barriers to recruitment and retention that were reported by at least 2 sites (Table). While there were some common themes, the reported barriers to retention differed from those to recruitment. The most reported barriers to recruitment were 46 respondents who noted salary, 23 reported human resources-related challenges, and 12 reported location. Respondents also noted various retention barriers, including 32 respondents who reported salary barriers; 13 reported administrative burden barriers, 6 reported medical center leadership, and 4 reported burnout.

Survey respondents provided multiple recommendations on how the VA can best support the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists. The most frequent recommendations were to increase financial compensation by increasing the current aggregate salary cap to > $400,000, increasing the use of recruitment and retention incentives, and ensuring that gastroenterology is on the national Educational Debt Reduction Program (EDRP) list, which facilitates student loan repayment. It was recommended that a third-party company assist with hiring to overcome perceived issues with human resources. Additionally, there were multiple recommendations for improving administrative and clinical support. These included mandating how many support staff should be assigned to each gastroenterologist and providing best practice recommendations for support staff so that gastroenterologists can focus on physician-level work. Recommendations also included having a dedicated gastroenterology practice manager, nurse care coordinators, a colorectal cancer screening/surveillance coordinator, sufficient medical support assistants, and quality improvement personnel tracking ongoing professional practice evaluation data. Survey respondents also highlighted specific suggestions for recruiting recent graduates. These included offering a 4-day work week, as recent graduates place a premium on work-life balance, and ensuring gastroenterologists have individual offices. One respondent commented that gastroenterology fellows seeing VA gastroenterology attendings in cramped, shared offices, contrasted with private practice gastroenterologists in large private offices, may contribute to choosing private practice over joining the VA.

Discussion

Gastroenterology is currently listed by VHA WMC as 1 of the top 3 medical specialties in the VA with the most physician shortages.5 Working as a physician in the VA has long been recognized to have many benefits. First and foremost, many physicians are motivated by the VA mission to serve veterans, as this offers personal fulfillment and other intangible benefits. In addition, the VA can provide work-life balance, which is often not possible in fee-for-service settings, with patient panels and call volumes typically lower than in comparable private hospital settings. Moreover, VA physicians have outstanding teaching opportunities, as the VA is the largest supporter of medical education, with postgraduate trainees rotating through > 150 VA medical centers. Likewise, the VA offers a variety of student loan repayment programs (eg, the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program and the EDRP). The VA offers research funding such as the Cooperative Studies Programs or program project funding, and rewards in parallel with the National Institute of Health (eg, career development awards, or merit review awards) and other grants. VA researchers have conducted many landmark studies that continue to shape the practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. From the earliest studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of screening colonoscopy, to the largest ongoing clinical trial in US history to assess the effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) vs screening colonoscopy.10-12 The VA has also led the field in the study of gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C treatment, and liver cancer screening.13-15 VA physicians also benefit from participation in the Federal Employee Retirement System, including its pension system.

These benefits apply to all medical specialties, making the VA a potentially appealing workplace for gastroenterologists. However, recent trends indicate that recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists is increasingly challenging, as the VA gastroenterology workforce grew by 5.0% in fiscal year (FY) 2020 and 1.8% in FY 2021. However, it was on track to end FY 2022 with a loss (-1.1%).5 It must be noted that this trend is not limited to the VA, and the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis predicts that gastroenterology will remain among the highest projected specialty shortages. Driven by increased demand for digestive health care services, more physicians nearing traditional retirement age, and substantially higher rates of burnout after the COVID-19 pandemic.16 All these factors are likely to result in an increasingly competitive market for gastroenterology, highlight the growing differences between VA and non-VA positions, and may augment the impact of differences for the individual gastroenterologist weighing employment options within and outside the VA.

The survey responses from VA gastroenterology section chiefs help identify potential impediments to the successful recruitment and retention in the specialty. Noncompetitive salary was the most significant barrier to the successful recruitment of gastroenterologists, identified by 46 of 55 respondents. According to a 2022 Medical Group Management Association report, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was $561,375.7 According to internal VA WMC data, the median 2022 VA gastroenterologist salary ranged between $287,976 and $346,435, depending on facility complexity level, excluding recruitment, retention, or relocation bonuses; performance pay; or cash awards. The current aggregate salary cap of $400,000 indicates that the VHA will likely be increasingly noncompetitive in the coming years unless novel pay authorizations are implemented.

Suboptimal human resources were the second most commonly cited impediment to recruiting gastroenterologists. Many section chiefs expressed frustration with the inefficient and slow administrative process of onboarding new gastroenterologists, which may take many months and not infrequently results in losing candidates to competing entities. While this issue is specific to recruitment, recurring and long-standing vacancies can increase work burdens, complicate logistics for remaining faculty, and may also negatively impact retention. One potential opportunity to improve VHA competitiveness is to streamline the administrative component of recruitment and optimize human resources support. The use of a third-party hiring company also should be considered.

Survey responses also indicated that administrative burden and insufficient support staff were significant retention challenges. Several respondents described a lack of efficient endoscopy workflow and delegation of simple administrative tasks to gastroenterologists as more likely in units without proper task distribution. Importantly, these shortcomings occur at the expense of workload-generating activities and career-enhancing opportunities.

While burnout rates among VA gastroenterologists have not been documented systematically, they likely correlate with workplace frustration and jeopardizegastroenterologist retention. Successful retention of gastroenterologists as highly trained medical professionals is more likely in workplaces that are vertically organized, efficient, and use physicians at the top of their skill level.

Conclusions

The VA offers the opportunity for a rewarding lifelong career in gastroenterology. The fulfillment of serving veterans, teaching future health care leaders, performing impactful research, and having job security is invaluable. Despite the tremendous benefits, this survey supports improving VA recruitment and retention strategies for the high-demand gastroenterology specialty. Improved salary parity is needed for workforce maintenance and recruitment, as is improved administrative and clinical support to maintain the high level of care our veterans deserve.

1. Shin A, Xu H, Imperiale TF. The prevalence, humanistic burden, and health care impact of irritable bowel syndrome among united states veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):1061-1069.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.08.005.

2. Kent KG. Prevalence of gastrointestinal disease in US military veterans under outpatient care at the veterans health administration. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211049112. doi:10.1177/20503121211049112

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

5. VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/WMCPortal/WFP/Documents/Reports/VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint FY 23-27.pdf [Source not verified]

6. AMN Healthcare. 2022 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www1.amnhealthcare.com/l/123142/2022-07-13/q6ywxg/123142/1657737392vyuONaZZ/mha2022incentivesurgraphic.pdf

7. Medical Group Management Association. MGMA DataDive Provider Compensation Data. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.mgma.com/datadive/provider-compensation

8. Anderson JC, Bilal M, Burke CA, et al. Burnout among US gastroenterologists and fellows in training: identifying contributing factors and offering solutions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(10):1063-1069. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001781

9. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311-317. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

10. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans affairs cooperative study group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):162-168. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430301

11. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):555-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010328

12. Robertson DJ, Dominitz JA, Beed A, et al. Baseline features and reasons for nonparticipation in the colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test in reducing mortality from colorectal cancer (CONFIRM) study, a colorectal cancer screening trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321730. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21730

13. Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811424

14. Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):32-39. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.027

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans affairs cooperative studies program (CSP). CSP #2023. Updated July 2022. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

16. US Health Resources & Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

1. Shin A, Xu H, Imperiale TF. The prevalence, humanistic burden, and health care impact of irritable bowel syndrome among united states veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):1061-1069.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.08.005.

2. Kent KG. Prevalence of gastrointestinal disease in US military veterans under outpatient care at the veterans health administration. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211049112. doi:10.1177/20503121211049112

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

5. VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/WMCPortal/WFP/Documents/Reports/VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint FY 23-27.pdf [Source not verified]

6. AMN Healthcare. 2022 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www1.amnhealthcare.com/l/123142/2022-07-13/q6ywxg/123142/1657737392vyuONaZZ/mha2022incentivesurgraphic.pdf

7. Medical Group Management Association. MGMA DataDive Provider Compensation Data. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.mgma.com/datadive/provider-compensation

8. Anderson JC, Bilal M, Burke CA, et al. Burnout among US gastroenterologists and fellows in training: identifying contributing factors and offering solutions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(10):1063-1069. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001781

9. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311-317. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

10. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans affairs cooperative study group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):162-168. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430301

11. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):555-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010328

12. Robertson DJ, Dominitz JA, Beed A, et al. Baseline features and reasons for nonparticipation in the colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test in reducing mortality from colorectal cancer (CONFIRM) study, a colorectal cancer screening trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321730. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21730

13. Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811424

14. Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):32-39. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.027

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans affairs cooperative studies program (CSP). CSP #2023. Updated July 2022. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

16. US Health Resources & Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections