User login

A 61-year-old man, who had recently emigrated from the Ukraine, presented to his primary care provider with a chief complaint of painful oral lesions and weight loss. The patient described the gradual onset of a severe sore throat and mouth pain three months earlier. Originally, he attributed his symptoms to an upper respiratory infection but became concerned when his symptoms did not resolve.

He reported that the pain had worsened over time and that he was now barely able to swallow solid food or tolerate acidic beverages due to considerable discomfort. His son, who accompanied him to the appointment, had also noted weight loss.

The patient denied any concomitant symptoms, including fever, cough, night sweats, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, diarrhea, melena, or concomitant rash. His medical history was remarkable only for stage 1 hypertension, which had been well controlled on hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg/d for the previous three years. However, the patient had received only minimal preventive health care while living in the Ukraine. His family history was unknown.

One week earlier, the patient had seen a dentist complaining of mouth pain, and was referred to an oral medicine specialist; this specialist, in turn, referred the patient to a primary care nurse practitioner for lab work to confirm the suspected diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris.

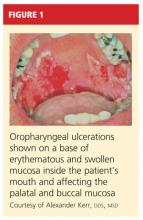

On physical examination, the patient appeared older than his stated age. He was a thin, mildly ill–appearing man, afebrile and normotensive, with heart rate and respirations within normal limits. However, intraoral examination revealed multiple oropharyngeal ulcerations of varying size on a base of erythematous and swollen mucosa on the inside of the man’s cheek and palatal and buccal mucosa (see Figure 1). On his upper back, two round, crusted blisters were noted in isolation (Figure 2). The remaining findings in the physical examination were unremarkable.

Based on the patient’s physical exam findings and clinical guideline recommendations regarding chronic oral ulcerations of unknown etiology,1,2 the patient was scheduled for a cytologic smear to be performed by oral medicine, followed by a gingival biopsy for a direct immunofluorescence test and routine histopathology.3 Unfortunately, due to extensive involvement and concern for possible mucosal shredding, an oral biopsy was not deemed possible.

However, the oral medicine specialist, because he strongly suspected pemphigus vulgaris, recommended testing for circulating autoantibodies against the antigens desmogleins 1 and/or 3 in the epidermis, which are responsible for cellular adhesion. (A positive test result supports, but does not confirm, a diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris.4)

Additionally, baseline labs were performed for signs of systemic illness, including infection, anemia, and liver and kidney disease. Frequent monitoring was conducted for steroid-induced symptoms of elevated blood sugars; the primary care provider was responsible for monitoring the patient for weight gain and steroid-induced psychosis. The patient was referred to gastroenterology for a colonoscopy to ensure that his weight loss and anorexia were not the result of gastrointestinal malignancy. However, the patient declined this test.

DISCUSSION

Painful oral lesions can have numerous etiologies of varying severity and complexity, including herpes simplex virus infection, aphthae, lichen planus, erythema multiforme, squamous cell and other oral carcinomas, primary HIV infection, lupus, and pemphigus. Differentiating among these conditions requires a careful medical history and complete physical exam.5

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is the most common variant of pemphigus, a group of chronic autoimmune diseases that cause blistering and ulceration of the mucous membranes and the skin.6 From the Greek pemphix (bubble), PV is more common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish or Mediterranean descent,6,7 usually occurs in middle-aged and older persons, and occurs about 1.5 times more commonly in women than men.5,7 Until the introduction of systemic steroids, pemphigus was often a fatal disease. Significant mortality still exists, mainly as a result of infection or adverse reactions to medication therapy.5

In patients with PV, flaccid bullae are formed on the skin in a process called acantholysis, in which epidermal cells lose their ability to adhere to one another. This results in rapidly expanding, thin-walled blisters on the oral mucosa, scalp, face, axillae, and groin. The blisters burst easily, leaving irregularly shaped, painful ulcerations.4 Painful oral mucosal membrane erosions are the first presenting sign of PV and often the only sign for an average of five months before other skin lesions develop.3 These lesions are noninfectious.

To make a definitive diagnosis of PV, clinical lesions must be present, with a confirmation of histologic findings, acantholysis on biopsy, and a confirmation of autoantibodies present in tissue and/or serum.4 (For proposed detailed diagnostic criteria, see table4,8.)

Initial misdiagnoses, which often lead to delayed or incorrect treatment, usually include aphthous stomatitis, gingivostomatitis, erythema multiforme, erosive lichen planus, herpes simplex virus, and/or oral candidiasis.3

Common Differentials

Herpes simplex virus. Affecting between 15% and 45% of the population, herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, also known as cold sores, is the most common cause of recurrent oral ulcers.9 HSV is transmitted through direct contact with lesions or via viral shedding. Primary infection, which may occur with flu-like symptoms, causes the sudden onset of multiple clustered vesicles on an erythematous base that quickly ulcerate and crust. Recurrent infections tend to be less severe and are accompanied by minimal systemic symptoms.10

Diagnosis is usually made through history and physical exam. However, diagnostic tests, including Tzanck smears, biopsy, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, and/or viral isolation in culture, are sometimes used to confirm a suspected case.10

Oral lichen planus (OLP). This is a common, chronic, mucocutaneous inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that affects skin and mucous membranes of the mouth, including the buccal mucosa, tongue, and/or gums. These lesions are noninfectious and are an immunologically mediated disease. Stress, anxiety, genetic predisposition, NSAID use, antihypertensive medications (eg, captopril, enalapril, propranolol; considered an oral lichenoid drug reaction), and altered cell-mediated immune response have been considered possible causative factors.11,12 Recent reports suggest an association between hepatitis C virus and OLP.13

Affecting about 4% of the general population, and more predominate in perimenopausal women, OLP lesions appear as white, lacey patches; red, swollen tissues; or open sores, most commonly on the inside of the mouth bilaterally. Patients will present with complaints of burning, roughness, or pain in the mouth, dry mouth, sensitivity to hot or spicy foods, and difficulty swallowing if the throat is involved. Diagnosis is based on history and physical examination and often a confirmatory biopsy. Topical high-potency corticosteroids are generally first-line therapy, with systemic medications such as oral prednisone used to treat severe cases.14,15

Oral candidiasis. Up to 80% of healthy individuals carry Candida albicans in their mouths16; this pathogen accounts for about half of all cases of oral candidiasis (oral thrush). Oral infections occur only with an underlying predisposing condition in the host. Oral thrush presents as creamy white lesions on the oral mucosa; a diagnostic feature is that the plaques can be removed to reveal an erythematous base.16,17

In the chronic form of candidiasis, the mucosal surface is bright red and smooth. When the tongue is involved, it may appear dry, fissured, or cracked. Patients may report a dry mouth, burning pain, and difficulty eating. Infection can be confirmed with periodic acid-Schiff staining of a smear to detect candidal hyphae.9

Use of antifungal creams and lozenges, as well as improved oral hygiene, will often lead to resolution of symptoms.9 Management of any associated underlying conditions, such as diabetes, asthma requiring long-term use of steroid inhalers, or infection with HIV/AIDS, is essential.18

Oral aphthae. Recurrent aphthous ulcers (commonly called canker sores; also referred to as recurrent aphthous stomatitis [RAS]) are a common oral condition. Etiology is unknown and most likely multifactorial, with a strong genetic tendency and multiple predisposing factors, including trauma, stress, food allergies, hormones, and smoking.19 Certain chronic illnesses, including celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), HIV, and neutropenia may also predispose patients to RAS or RAS-like syndromes.

Aphthous ulcers are classified as minor or major. Minor aphthae, which account for 90% of RAS cases, present as single or multiple, small, oval or round ulcers with an erythematous halo on the buccal or labial mucosa or tongue.19 The ulcers last 7 to 10 days and heal spontaneously without scarring.

Diagnosis, based on history and clinical presentation, may include evaluation for systemic causes of oral ulcers. Treatment for both minor and major apthae is palliative, with mainstays including topical corticosteroids, mouth rinses, and, in severe cases, thalidomide, although randomized controlled trials have not shown this agent to be of benefit.9

Treatment for Pemphigus Vulgaris

The outcome goal for management of pemphigus is to achieve and maintain remission. This includes the epithelialization of all skin and mucosal lesions, prevention of relapse, minimization of adverse treatment effects, and successful withdrawal of therapeutic medications.20

The response to treatment varies greatly among patients, as the optimal therapeutic regimen for pemphigus is unknown.20 Systemic glucocorticoids are considered the gold standard of treatment and management, but their use has been associated with several adverse effects, including weight gain and elevated blood sugar levels. Recently, the combination of IV immune globulin and biological therapies (eg, rituximab) that target specific molecules in the inflammatory process have been demonstrated as effective in cases of refractory pemphigus.21,22

PATIENT MANAGEMENT AND OUTCOME

Several referrals were made, including dermatology, for its familiarity with autoimmune diseases of the skin. There, the patient was fully examined and found to have a small truncal lesion compatible with PV. He was referred to an otolaryngologist for a nasal endoscopy to determine the extent of the lesions. They were found to extend far beyond his oral cavity into his esophagus.

Based on a positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for PV antibodies, a cytologic smear with acantholytic cells, and a classic clinical presentation of PV, the patient was started on prednisone 80 mg/d with azathioprine 50 mg/d for the first 14 days.23,24 He responded quickly to these oral medications and underwent a confirmatory oral biopsy within a few weeks.

After several months, the patient was slowly titrated down to lower maintenance doses of prednisone and azathioprine. Now in remission, he continues to receive collaborative management from oral medicine, dermatology, and a nurse practitioner–managed primary care practice. Health care maintenance has included appropriate vaccination and discussion regarding prostate cancer screening, per 2010 guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force.25

CONCLUSION

Since the differential diagnosis for pemphigus vulgaris is extensive and the diagnostic criteria are exacting, many affected patients are undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, with a resulting delay in effective treatment. It is important for the primary care clinician to undertake a frequent review of common oral infections, particularly those with similar presentations.

The authors extend their thanks to Alexander Kerr, DDS, MSD, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillary Pathology, Radiology and Medicine, New York University College of Dentistry, for the images included in this article and for Dr. Kerr’s clinical expertise and partnership.

REFERENCES

1. Sciubba JJ. Oral mucosal diseases in the office setting. Part II. Oral lichen planus, pemphigus vulgaris, and mucosal pemphigoid. Gen Dent. 2007;55(5):464-476.

2. Muñoz-Corcuera M, Esparza-Gómez G, González-Moles MA, Bascones-Martínez A. Oral ulcers: clinical aspects. A tool for dermatologists. Part II. Chronic ulcers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009; 34(4):456-461.

3. Dagistan S, Goregen M, Miloglu O, Cakur B. Oral pemphigus vulgaris: a case report with review of the literature. J Oral Sci. 2008;50(3):359-362.

4. Singh S. Evidence-based treatments for pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus and bullous pemphigoid: a systematic review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77(4):456-469.

5. Ohta M, Osawa S, Endo H, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris confined to the gingiva: a case report. Int J Dent. 2011;2011:207153. Epub 2011 May 11.

6. Mignona MD, Fortuna G, Leuci S. Oral pemphigus. Minerva Stomatol. 2009;58(10):501-518.

7. Mimouni D, Bar H, Gdalevich M, et al. Pemphigus: analysis of epidemiological factors in 155 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008; 22(10):1232-1235.

8. Amagai M, Ikeda S, Shimizu H, et al. A randomized double-blind trial of intravenous immunoglobulin for pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(4):595-603.

9. Gonsalves WC, Chi AC, Neville BW. Common oral lesions: Part I. Superficial mucosal lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(4):501-507.

10. Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz R. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):737-763.

11. Sugerman PB, Savage NW. Oral lichen planus: causes, diagnosis and management. Aust Dent J. 2002;47(4):290-297.

12. Kaomongkolgit R. Oral lichenoid drug reaction associated with antihypertensive and hypoglycemic drugs. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(1):73-75.

13. Petti S, Rabiei M, De Luca M, Scully C. The magnitude of the association between hepatitis C virus infection and oral lichen planus: meta-analysis and case control study. Odontology. 2011;99(2):168-178.

14. Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(1): 53-60.

15. Thongprasom K, Carrozzo M, Furness S, Lodi G. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jul 6; (7):CD001168.

16. Giannini PJ, Shetty KV. Diagnosis and management of oral candidiasis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44(1):231-240, vii.

17. Lynch DP. Oral candidiasis. History, classification, and clinical presentation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78(2):189-193.

18. Williams D, Lewis M. Pathogenesis and treatment of oral candidosis. J Oral Microbiol. 2011 Jan 28;3. doi: 10.3402/jom.v3i0.5771.

19. Scully C, Challacombe SJ. Pemphigus vulgaris: update on etiopathogenesis, oral manifestations, and management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13(5):397-408.

20. Martin LK, Werth V, Villanueva E, Murrell DF. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials for pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(5):903-908.

21. Joly P, Mouquet H, Roujeau JC, et al. A single cycle of rituximab for the treatment of severe pemphigus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):545-552.

22. Diaz LA. Rituximab and pemphigus: a therapeutic advance. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):605-607.

23. Anstey AV, Wakelin S, Reynolds NJ. Guidelines for prescribing azathioprine in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(6):1123-1132.

24. Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M. Prednisolone dosage in pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(3):547.

25. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2010-2011: recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force. AHRQ Publication No. 10-05145, September 2010. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd1011/pocketgd1011.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2012.

A 61-year-old man, who had recently emigrated from the Ukraine, presented to his primary care provider with a chief complaint of painful oral lesions and weight loss. The patient described the gradual onset of a severe sore throat and mouth pain three months earlier. Originally, he attributed his symptoms to an upper respiratory infection but became concerned when his symptoms did not resolve.

He reported that the pain had worsened over time and that he was now barely able to swallow solid food or tolerate acidic beverages due to considerable discomfort. His son, who accompanied him to the appointment, had also noted weight loss.

The patient denied any concomitant symptoms, including fever, cough, night sweats, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, diarrhea, melena, or concomitant rash. His medical history was remarkable only for stage 1 hypertension, which had been well controlled on hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg/d for the previous three years. However, the patient had received only minimal preventive health care while living in the Ukraine. His family history was unknown.

One week earlier, the patient had seen a dentist complaining of mouth pain, and was referred to an oral medicine specialist; this specialist, in turn, referred the patient to a primary care nurse practitioner for lab work to confirm the suspected diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris.

On physical examination, the patient appeared older than his stated age. He was a thin, mildly ill–appearing man, afebrile and normotensive, with heart rate and respirations within normal limits. However, intraoral examination revealed multiple oropharyngeal ulcerations of varying size on a base of erythematous and swollen mucosa on the inside of the man’s cheek and palatal and buccal mucosa (see Figure 1). On his upper back, two round, crusted blisters were noted in isolation (Figure 2). The remaining findings in the physical examination were unremarkable.

Based on the patient’s physical exam findings and clinical guideline recommendations regarding chronic oral ulcerations of unknown etiology,1,2 the patient was scheduled for a cytologic smear to be performed by oral medicine, followed by a gingival biopsy for a direct immunofluorescence test and routine histopathology.3 Unfortunately, due to extensive involvement and concern for possible mucosal shredding, an oral biopsy was not deemed possible.

However, the oral medicine specialist, because he strongly suspected pemphigus vulgaris, recommended testing for circulating autoantibodies against the antigens desmogleins 1 and/or 3 in the epidermis, which are responsible for cellular adhesion. (A positive test result supports, but does not confirm, a diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris.4)

Additionally, baseline labs were performed for signs of systemic illness, including infection, anemia, and liver and kidney disease. Frequent monitoring was conducted for steroid-induced symptoms of elevated blood sugars; the primary care provider was responsible for monitoring the patient for weight gain and steroid-induced psychosis. The patient was referred to gastroenterology for a colonoscopy to ensure that his weight loss and anorexia were not the result of gastrointestinal malignancy. However, the patient declined this test.

DISCUSSION

Painful oral lesions can have numerous etiologies of varying severity and complexity, including herpes simplex virus infection, aphthae, lichen planus, erythema multiforme, squamous cell and other oral carcinomas, primary HIV infection, lupus, and pemphigus. Differentiating among these conditions requires a careful medical history and complete physical exam.5

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is the most common variant of pemphigus, a group of chronic autoimmune diseases that cause blistering and ulceration of the mucous membranes and the skin.6 From the Greek pemphix (bubble), PV is more common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish or Mediterranean descent,6,7 usually occurs in middle-aged and older persons, and occurs about 1.5 times more commonly in women than men.5,7 Until the introduction of systemic steroids, pemphigus was often a fatal disease. Significant mortality still exists, mainly as a result of infection or adverse reactions to medication therapy.5

In patients with PV, flaccid bullae are formed on the skin in a process called acantholysis, in which epidermal cells lose their ability to adhere to one another. This results in rapidly expanding, thin-walled blisters on the oral mucosa, scalp, face, axillae, and groin. The blisters burst easily, leaving irregularly shaped, painful ulcerations.4 Painful oral mucosal membrane erosions are the first presenting sign of PV and often the only sign for an average of five months before other skin lesions develop.3 These lesions are noninfectious.

To make a definitive diagnosis of PV, clinical lesions must be present, with a confirmation of histologic findings, acantholysis on biopsy, and a confirmation of autoantibodies present in tissue and/or serum.4 (For proposed detailed diagnostic criteria, see table4,8.)

Initial misdiagnoses, which often lead to delayed or incorrect treatment, usually include aphthous stomatitis, gingivostomatitis, erythema multiforme, erosive lichen planus, herpes simplex virus, and/or oral candidiasis.3

Common Differentials

Herpes simplex virus. Affecting between 15% and 45% of the population, herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, also known as cold sores, is the most common cause of recurrent oral ulcers.9 HSV is transmitted through direct contact with lesions or via viral shedding. Primary infection, which may occur with flu-like symptoms, causes the sudden onset of multiple clustered vesicles on an erythematous base that quickly ulcerate and crust. Recurrent infections tend to be less severe and are accompanied by minimal systemic symptoms.10

Diagnosis is usually made through history and physical exam. However, diagnostic tests, including Tzanck smears, biopsy, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, and/or viral isolation in culture, are sometimes used to confirm a suspected case.10

Oral lichen planus (OLP). This is a common, chronic, mucocutaneous inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that affects skin and mucous membranes of the mouth, including the buccal mucosa, tongue, and/or gums. These lesions are noninfectious and are an immunologically mediated disease. Stress, anxiety, genetic predisposition, NSAID use, antihypertensive medications (eg, captopril, enalapril, propranolol; considered an oral lichenoid drug reaction), and altered cell-mediated immune response have been considered possible causative factors.11,12 Recent reports suggest an association between hepatitis C virus and OLP.13

Affecting about 4% of the general population, and more predominate in perimenopausal women, OLP lesions appear as white, lacey patches; red, swollen tissues; or open sores, most commonly on the inside of the mouth bilaterally. Patients will present with complaints of burning, roughness, or pain in the mouth, dry mouth, sensitivity to hot or spicy foods, and difficulty swallowing if the throat is involved. Diagnosis is based on history and physical examination and often a confirmatory biopsy. Topical high-potency corticosteroids are generally first-line therapy, with systemic medications such as oral prednisone used to treat severe cases.14,15

Oral candidiasis. Up to 80% of healthy individuals carry Candida albicans in their mouths16; this pathogen accounts for about half of all cases of oral candidiasis (oral thrush). Oral infections occur only with an underlying predisposing condition in the host. Oral thrush presents as creamy white lesions on the oral mucosa; a diagnostic feature is that the plaques can be removed to reveal an erythematous base.16,17

In the chronic form of candidiasis, the mucosal surface is bright red and smooth. When the tongue is involved, it may appear dry, fissured, or cracked. Patients may report a dry mouth, burning pain, and difficulty eating. Infection can be confirmed with periodic acid-Schiff staining of a smear to detect candidal hyphae.9

Use of antifungal creams and lozenges, as well as improved oral hygiene, will often lead to resolution of symptoms.9 Management of any associated underlying conditions, such as diabetes, asthma requiring long-term use of steroid inhalers, or infection with HIV/AIDS, is essential.18

Oral aphthae. Recurrent aphthous ulcers (commonly called canker sores; also referred to as recurrent aphthous stomatitis [RAS]) are a common oral condition. Etiology is unknown and most likely multifactorial, with a strong genetic tendency and multiple predisposing factors, including trauma, stress, food allergies, hormones, and smoking.19 Certain chronic illnesses, including celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), HIV, and neutropenia may also predispose patients to RAS or RAS-like syndromes.

Aphthous ulcers are classified as minor or major. Minor aphthae, which account for 90% of RAS cases, present as single or multiple, small, oval or round ulcers with an erythematous halo on the buccal or labial mucosa or tongue.19 The ulcers last 7 to 10 days and heal spontaneously without scarring.

Diagnosis, based on history and clinical presentation, may include evaluation for systemic causes of oral ulcers. Treatment for both minor and major apthae is palliative, with mainstays including topical corticosteroids, mouth rinses, and, in severe cases, thalidomide, although randomized controlled trials have not shown this agent to be of benefit.9

Treatment for Pemphigus Vulgaris

The outcome goal for management of pemphigus is to achieve and maintain remission. This includes the epithelialization of all skin and mucosal lesions, prevention of relapse, minimization of adverse treatment effects, and successful withdrawal of therapeutic medications.20

The response to treatment varies greatly among patients, as the optimal therapeutic regimen for pemphigus is unknown.20 Systemic glucocorticoids are considered the gold standard of treatment and management, but their use has been associated with several adverse effects, including weight gain and elevated blood sugar levels. Recently, the combination of IV immune globulin and biological therapies (eg, rituximab) that target specific molecules in the inflammatory process have been demonstrated as effective in cases of refractory pemphigus.21,22

PATIENT MANAGEMENT AND OUTCOME

Several referrals were made, including dermatology, for its familiarity with autoimmune diseases of the skin. There, the patient was fully examined and found to have a small truncal lesion compatible with PV. He was referred to an otolaryngologist for a nasal endoscopy to determine the extent of the lesions. They were found to extend far beyond his oral cavity into his esophagus.

Based on a positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for PV antibodies, a cytologic smear with acantholytic cells, and a classic clinical presentation of PV, the patient was started on prednisone 80 mg/d with azathioprine 50 mg/d for the first 14 days.23,24 He responded quickly to these oral medications and underwent a confirmatory oral biopsy within a few weeks.

After several months, the patient was slowly titrated down to lower maintenance doses of prednisone and azathioprine. Now in remission, he continues to receive collaborative management from oral medicine, dermatology, and a nurse practitioner–managed primary care practice. Health care maintenance has included appropriate vaccination and discussion regarding prostate cancer screening, per 2010 guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force.25

CONCLUSION

Since the differential diagnosis for pemphigus vulgaris is extensive and the diagnostic criteria are exacting, many affected patients are undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, with a resulting delay in effective treatment. It is important for the primary care clinician to undertake a frequent review of common oral infections, particularly those with similar presentations.

The authors extend their thanks to Alexander Kerr, DDS, MSD, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillary Pathology, Radiology and Medicine, New York University College of Dentistry, for the images included in this article and for Dr. Kerr’s clinical expertise and partnership.

REFERENCES

1. Sciubba JJ. Oral mucosal diseases in the office setting. Part II. Oral lichen planus, pemphigus vulgaris, and mucosal pemphigoid. Gen Dent. 2007;55(5):464-476.

2. Muñoz-Corcuera M, Esparza-Gómez G, González-Moles MA, Bascones-Martínez A. Oral ulcers: clinical aspects. A tool for dermatologists. Part II. Chronic ulcers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009; 34(4):456-461.

3. Dagistan S, Goregen M, Miloglu O, Cakur B. Oral pemphigus vulgaris: a case report with review of the literature. J Oral Sci. 2008;50(3):359-362.

4. Singh S. Evidence-based treatments for pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus and bullous pemphigoid: a systematic review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77(4):456-469.

5. Ohta M, Osawa S, Endo H, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris confined to the gingiva: a case report. Int J Dent. 2011;2011:207153. Epub 2011 May 11.

6. Mignona MD, Fortuna G, Leuci S. Oral pemphigus. Minerva Stomatol. 2009;58(10):501-518.

7. Mimouni D, Bar H, Gdalevich M, et al. Pemphigus: analysis of epidemiological factors in 155 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008; 22(10):1232-1235.

8. Amagai M, Ikeda S, Shimizu H, et al. A randomized double-blind trial of intravenous immunoglobulin for pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(4):595-603.

9. Gonsalves WC, Chi AC, Neville BW. Common oral lesions: Part I. Superficial mucosal lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(4):501-507.

10. Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz R. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):737-763.

11. Sugerman PB, Savage NW. Oral lichen planus: causes, diagnosis and management. Aust Dent J. 2002;47(4):290-297.

12. Kaomongkolgit R. Oral lichenoid drug reaction associated with antihypertensive and hypoglycemic drugs. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(1):73-75.

13. Petti S, Rabiei M, De Luca M, Scully C. The magnitude of the association between hepatitis C virus infection and oral lichen planus: meta-analysis and case control study. Odontology. 2011;99(2):168-178.

14. Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(1): 53-60.

15. Thongprasom K, Carrozzo M, Furness S, Lodi G. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jul 6; (7):CD001168.

16. Giannini PJ, Shetty KV. Diagnosis and management of oral candidiasis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44(1):231-240, vii.

17. Lynch DP. Oral candidiasis. History, classification, and clinical presentation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78(2):189-193.

18. Williams D, Lewis M. Pathogenesis and treatment of oral candidosis. J Oral Microbiol. 2011 Jan 28;3. doi: 10.3402/jom.v3i0.5771.

19. Scully C, Challacombe SJ. Pemphigus vulgaris: update on etiopathogenesis, oral manifestations, and management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13(5):397-408.

20. Martin LK, Werth V, Villanueva E, Murrell DF. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials for pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(5):903-908.

21. Joly P, Mouquet H, Roujeau JC, et al. A single cycle of rituximab for the treatment of severe pemphigus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):545-552.

22. Diaz LA. Rituximab and pemphigus: a therapeutic advance. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):605-607.

23. Anstey AV, Wakelin S, Reynolds NJ. Guidelines for prescribing azathioprine in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(6):1123-1132.

24. Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M. Prednisolone dosage in pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(3):547.

25. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2010-2011: recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force. AHRQ Publication No. 10-05145, September 2010. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd1011/pocketgd1011.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2012.

A 61-year-old man, who had recently emigrated from the Ukraine, presented to his primary care provider with a chief complaint of painful oral lesions and weight loss. The patient described the gradual onset of a severe sore throat and mouth pain three months earlier. Originally, he attributed his symptoms to an upper respiratory infection but became concerned when his symptoms did not resolve.

He reported that the pain had worsened over time and that he was now barely able to swallow solid food or tolerate acidic beverages due to considerable discomfort. His son, who accompanied him to the appointment, had also noted weight loss.

The patient denied any concomitant symptoms, including fever, cough, night sweats, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, diarrhea, melena, or concomitant rash. His medical history was remarkable only for stage 1 hypertension, which had been well controlled on hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg/d for the previous three years. However, the patient had received only minimal preventive health care while living in the Ukraine. His family history was unknown.

One week earlier, the patient had seen a dentist complaining of mouth pain, and was referred to an oral medicine specialist; this specialist, in turn, referred the patient to a primary care nurse practitioner for lab work to confirm the suspected diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris.

On physical examination, the patient appeared older than his stated age. He was a thin, mildly ill–appearing man, afebrile and normotensive, with heart rate and respirations within normal limits. However, intraoral examination revealed multiple oropharyngeal ulcerations of varying size on a base of erythematous and swollen mucosa on the inside of the man’s cheek and palatal and buccal mucosa (see Figure 1). On his upper back, two round, crusted blisters were noted in isolation (Figure 2). The remaining findings in the physical examination were unremarkable.

Based on the patient’s physical exam findings and clinical guideline recommendations regarding chronic oral ulcerations of unknown etiology,1,2 the patient was scheduled for a cytologic smear to be performed by oral medicine, followed by a gingival biopsy for a direct immunofluorescence test and routine histopathology.3 Unfortunately, due to extensive involvement and concern for possible mucosal shredding, an oral biopsy was not deemed possible.

However, the oral medicine specialist, because he strongly suspected pemphigus vulgaris, recommended testing for circulating autoantibodies against the antigens desmogleins 1 and/or 3 in the epidermis, which are responsible for cellular adhesion. (A positive test result supports, but does not confirm, a diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris.4)

Additionally, baseline labs were performed for signs of systemic illness, including infection, anemia, and liver and kidney disease. Frequent monitoring was conducted for steroid-induced symptoms of elevated blood sugars; the primary care provider was responsible for monitoring the patient for weight gain and steroid-induced psychosis. The patient was referred to gastroenterology for a colonoscopy to ensure that his weight loss and anorexia were not the result of gastrointestinal malignancy. However, the patient declined this test.

DISCUSSION

Painful oral lesions can have numerous etiologies of varying severity and complexity, including herpes simplex virus infection, aphthae, lichen planus, erythema multiforme, squamous cell and other oral carcinomas, primary HIV infection, lupus, and pemphigus. Differentiating among these conditions requires a careful medical history and complete physical exam.5

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is the most common variant of pemphigus, a group of chronic autoimmune diseases that cause blistering and ulceration of the mucous membranes and the skin.6 From the Greek pemphix (bubble), PV is more common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish or Mediterranean descent,6,7 usually occurs in middle-aged and older persons, and occurs about 1.5 times more commonly in women than men.5,7 Until the introduction of systemic steroids, pemphigus was often a fatal disease. Significant mortality still exists, mainly as a result of infection or adverse reactions to medication therapy.5

In patients with PV, flaccid bullae are formed on the skin in a process called acantholysis, in which epidermal cells lose their ability to adhere to one another. This results in rapidly expanding, thin-walled blisters on the oral mucosa, scalp, face, axillae, and groin. The blisters burst easily, leaving irregularly shaped, painful ulcerations.4 Painful oral mucosal membrane erosions are the first presenting sign of PV and often the only sign for an average of five months before other skin lesions develop.3 These lesions are noninfectious.

To make a definitive diagnosis of PV, clinical lesions must be present, with a confirmation of histologic findings, acantholysis on biopsy, and a confirmation of autoantibodies present in tissue and/or serum.4 (For proposed detailed diagnostic criteria, see table4,8.)

Initial misdiagnoses, which often lead to delayed or incorrect treatment, usually include aphthous stomatitis, gingivostomatitis, erythema multiforme, erosive lichen planus, herpes simplex virus, and/or oral candidiasis.3

Common Differentials

Herpes simplex virus. Affecting between 15% and 45% of the population, herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, also known as cold sores, is the most common cause of recurrent oral ulcers.9 HSV is transmitted through direct contact with lesions or via viral shedding. Primary infection, which may occur with flu-like symptoms, causes the sudden onset of multiple clustered vesicles on an erythematous base that quickly ulcerate and crust. Recurrent infections tend to be less severe and are accompanied by minimal systemic symptoms.10

Diagnosis is usually made through history and physical exam. However, diagnostic tests, including Tzanck smears, biopsy, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, and/or viral isolation in culture, are sometimes used to confirm a suspected case.10

Oral lichen planus (OLP). This is a common, chronic, mucocutaneous inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that affects skin and mucous membranes of the mouth, including the buccal mucosa, tongue, and/or gums. These lesions are noninfectious and are an immunologically mediated disease. Stress, anxiety, genetic predisposition, NSAID use, antihypertensive medications (eg, captopril, enalapril, propranolol; considered an oral lichenoid drug reaction), and altered cell-mediated immune response have been considered possible causative factors.11,12 Recent reports suggest an association between hepatitis C virus and OLP.13

Affecting about 4% of the general population, and more predominate in perimenopausal women, OLP lesions appear as white, lacey patches; red, swollen tissues; or open sores, most commonly on the inside of the mouth bilaterally. Patients will present with complaints of burning, roughness, or pain in the mouth, dry mouth, sensitivity to hot or spicy foods, and difficulty swallowing if the throat is involved. Diagnosis is based on history and physical examination and often a confirmatory biopsy. Topical high-potency corticosteroids are generally first-line therapy, with systemic medications such as oral prednisone used to treat severe cases.14,15

Oral candidiasis. Up to 80% of healthy individuals carry Candida albicans in their mouths16; this pathogen accounts for about half of all cases of oral candidiasis (oral thrush). Oral infections occur only with an underlying predisposing condition in the host. Oral thrush presents as creamy white lesions on the oral mucosa; a diagnostic feature is that the plaques can be removed to reveal an erythematous base.16,17

In the chronic form of candidiasis, the mucosal surface is bright red and smooth. When the tongue is involved, it may appear dry, fissured, or cracked. Patients may report a dry mouth, burning pain, and difficulty eating. Infection can be confirmed with periodic acid-Schiff staining of a smear to detect candidal hyphae.9

Use of antifungal creams and lozenges, as well as improved oral hygiene, will often lead to resolution of symptoms.9 Management of any associated underlying conditions, such as diabetes, asthma requiring long-term use of steroid inhalers, or infection with HIV/AIDS, is essential.18

Oral aphthae. Recurrent aphthous ulcers (commonly called canker sores; also referred to as recurrent aphthous stomatitis [RAS]) are a common oral condition. Etiology is unknown and most likely multifactorial, with a strong genetic tendency and multiple predisposing factors, including trauma, stress, food allergies, hormones, and smoking.19 Certain chronic illnesses, including celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), HIV, and neutropenia may also predispose patients to RAS or RAS-like syndromes.

Aphthous ulcers are classified as minor or major. Minor aphthae, which account for 90% of RAS cases, present as single or multiple, small, oval or round ulcers with an erythematous halo on the buccal or labial mucosa or tongue.19 The ulcers last 7 to 10 days and heal spontaneously without scarring.

Diagnosis, based on history and clinical presentation, may include evaluation for systemic causes of oral ulcers. Treatment for both minor and major apthae is palliative, with mainstays including topical corticosteroids, mouth rinses, and, in severe cases, thalidomide, although randomized controlled trials have not shown this agent to be of benefit.9

Treatment for Pemphigus Vulgaris

The outcome goal for management of pemphigus is to achieve and maintain remission. This includes the epithelialization of all skin and mucosal lesions, prevention of relapse, minimization of adverse treatment effects, and successful withdrawal of therapeutic medications.20

The response to treatment varies greatly among patients, as the optimal therapeutic regimen for pemphigus is unknown.20 Systemic glucocorticoids are considered the gold standard of treatment and management, but their use has been associated with several adverse effects, including weight gain and elevated blood sugar levels. Recently, the combination of IV immune globulin and biological therapies (eg, rituximab) that target specific molecules in the inflammatory process have been demonstrated as effective in cases of refractory pemphigus.21,22

PATIENT MANAGEMENT AND OUTCOME

Several referrals were made, including dermatology, for its familiarity with autoimmune diseases of the skin. There, the patient was fully examined and found to have a small truncal lesion compatible with PV. He was referred to an otolaryngologist for a nasal endoscopy to determine the extent of the lesions. They were found to extend far beyond his oral cavity into his esophagus.

Based on a positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for PV antibodies, a cytologic smear with acantholytic cells, and a classic clinical presentation of PV, the patient was started on prednisone 80 mg/d with azathioprine 50 mg/d for the first 14 days.23,24 He responded quickly to these oral medications and underwent a confirmatory oral biopsy within a few weeks.

After several months, the patient was slowly titrated down to lower maintenance doses of prednisone and azathioprine. Now in remission, he continues to receive collaborative management from oral medicine, dermatology, and a nurse practitioner–managed primary care practice. Health care maintenance has included appropriate vaccination and discussion regarding prostate cancer screening, per 2010 guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force.25

CONCLUSION

Since the differential diagnosis for pemphigus vulgaris is extensive and the diagnostic criteria are exacting, many affected patients are undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, with a resulting delay in effective treatment. It is important for the primary care clinician to undertake a frequent review of common oral infections, particularly those with similar presentations.

The authors extend their thanks to Alexander Kerr, DDS, MSD, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillary Pathology, Radiology and Medicine, New York University College of Dentistry, for the images included in this article and for Dr. Kerr’s clinical expertise and partnership.

REFERENCES

1. Sciubba JJ. Oral mucosal diseases in the office setting. Part II. Oral lichen planus, pemphigus vulgaris, and mucosal pemphigoid. Gen Dent. 2007;55(5):464-476.

2. Muñoz-Corcuera M, Esparza-Gómez G, González-Moles MA, Bascones-Martínez A. Oral ulcers: clinical aspects. A tool for dermatologists. Part II. Chronic ulcers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009; 34(4):456-461.

3. Dagistan S, Goregen M, Miloglu O, Cakur B. Oral pemphigus vulgaris: a case report with review of the literature. J Oral Sci. 2008;50(3):359-362.

4. Singh S. Evidence-based treatments for pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus and bullous pemphigoid: a systematic review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77(4):456-469.

5. Ohta M, Osawa S, Endo H, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris confined to the gingiva: a case report. Int J Dent. 2011;2011:207153. Epub 2011 May 11.

6. Mignona MD, Fortuna G, Leuci S. Oral pemphigus. Minerva Stomatol. 2009;58(10):501-518.

7. Mimouni D, Bar H, Gdalevich M, et al. Pemphigus: analysis of epidemiological factors in 155 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008; 22(10):1232-1235.

8. Amagai M, Ikeda S, Shimizu H, et al. A randomized double-blind trial of intravenous immunoglobulin for pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(4):595-603.

9. Gonsalves WC, Chi AC, Neville BW. Common oral lesions: Part I. Superficial mucosal lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(4):501-507.

10. Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz R. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):737-763.

11. Sugerman PB, Savage NW. Oral lichen planus: causes, diagnosis and management. Aust Dent J. 2002;47(4):290-297.

12. Kaomongkolgit R. Oral lichenoid drug reaction associated with antihypertensive and hypoglycemic drugs. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(1):73-75.

13. Petti S, Rabiei M, De Luca M, Scully C. The magnitude of the association between hepatitis C virus infection and oral lichen planus: meta-analysis and case control study. Odontology. 2011;99(2):168-178.

14. Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(1): 53-60.

15. Thongprasom K, Carrozzo M, Furness S, Lodi G. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jul 6; (7):CD001168.

16. Giannini PJ, Shetty KV. Diagnosis and management of oral candidiasis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44(1):231-240, vii.

17. Lynch DP. Oral candidiasis. History, classification, and clinical presentation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78(2):189-193.

18. Williams D, Lewis M. Pathogenesis and treatment of oral candidosis. J Oral Microbiol. 2011 Jan 28;3. doi: 10.3402/jom.v3i0.5771.

19. Scully C, Challacombe SJ. Pemphigus vulgaris: update on etiopathogenesis, oral manifestations, and management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13(5):397-408.

20. Martin LK, Werth V, Villanueva E, Murrell DF. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials for pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(5):903-908.

21. Joly P, Mouquet H, Roujeau JC, et al. A single cycle of rituximab for the treatment of severe pemphigus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):545-552.

22. Diaz LA. Rituximab and pemphigus: a therapeutic advance. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):605-607.

23. Anstey AV, Wakelin S, Reynolds NJ. Guidelines for prescribing azathioprine in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(6):1123-1132.

24. Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M. Prednisolone dosage in pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(3):547.

25. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2010-2011: recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force. AHRQ Publication No. 10-05145, September 2010. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd1011/pocketgd1011.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2012.