User login

Diagnostic Testing for Patients With Suspected Ocular Manifestations of Lyme Disease

Diagnostic Testing for Patients With Suspected Ocular Manifestations of Lyme Disease

Since Lyme disease (LD) was first identified in 1975, there has been uncertainty regarding the proper diagnostic testing for suspected cases.1 Challenges involved with ordering Lyme serology testing include navigating tests with an array of false negatives and false positives.2 Confounding these challenges is the wide variety of ocular manifestations of LD, ranging from nonspecific conjunctivitis, cranial palsies, and anterior and posterior segment inflammation.2,3 This article provides diagnostic testing guidelines for eye care clinicians who encounter patients with suspected LD.

BACKGROUND

LD is a bacterial infection caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex transmitted by the Ixodes tick genus. There are 4 species of Ixodes ticks that can infect humans, and only 2 have been identified as principal vectors in North America: Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus. The incidence of LD is on the rise due to increasing global temperatures and expanding geographic borders for the organism. Cases in endemic areas range from 10 per 100,000 people to 50 per 100,000 people.4

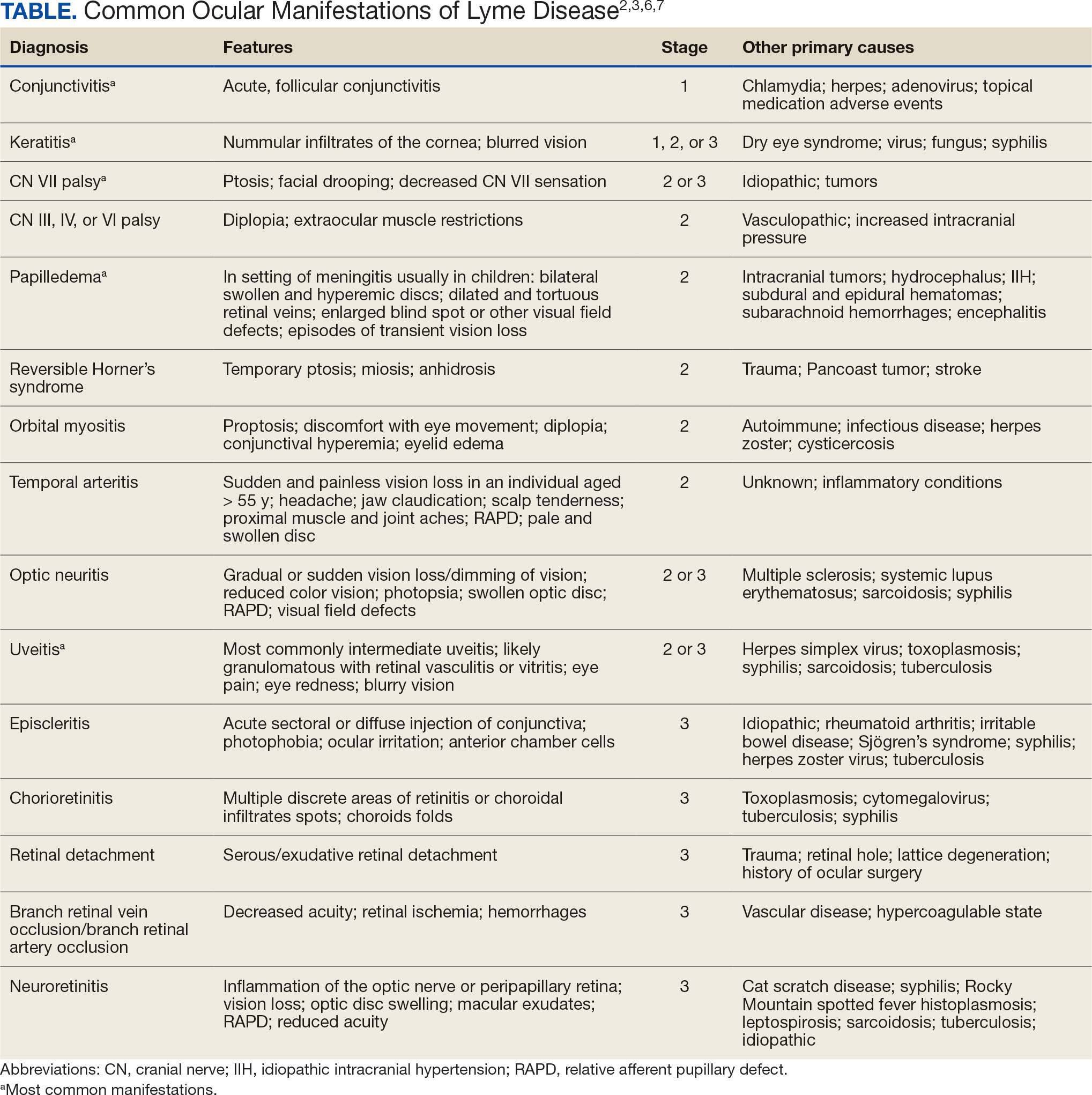

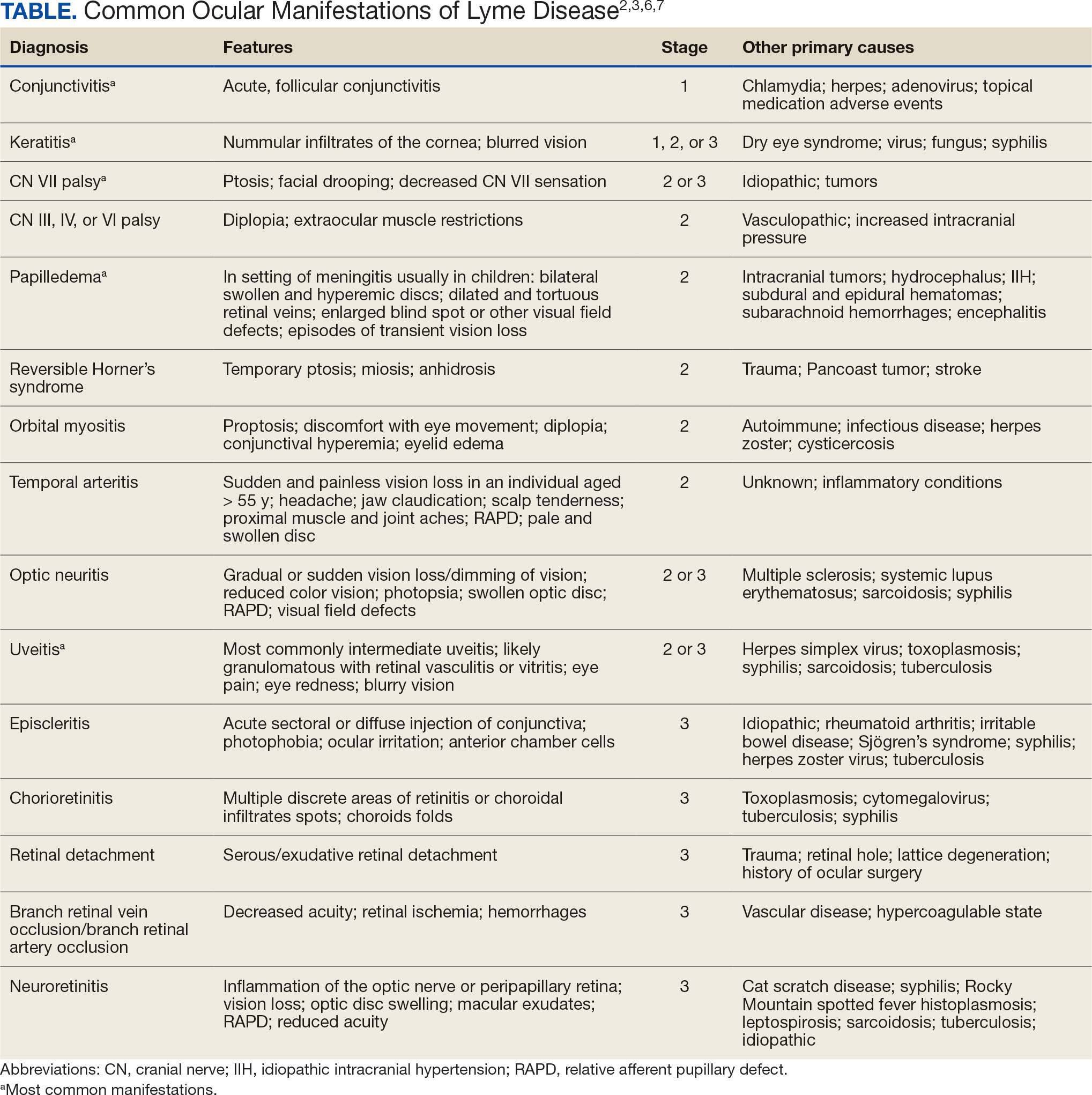

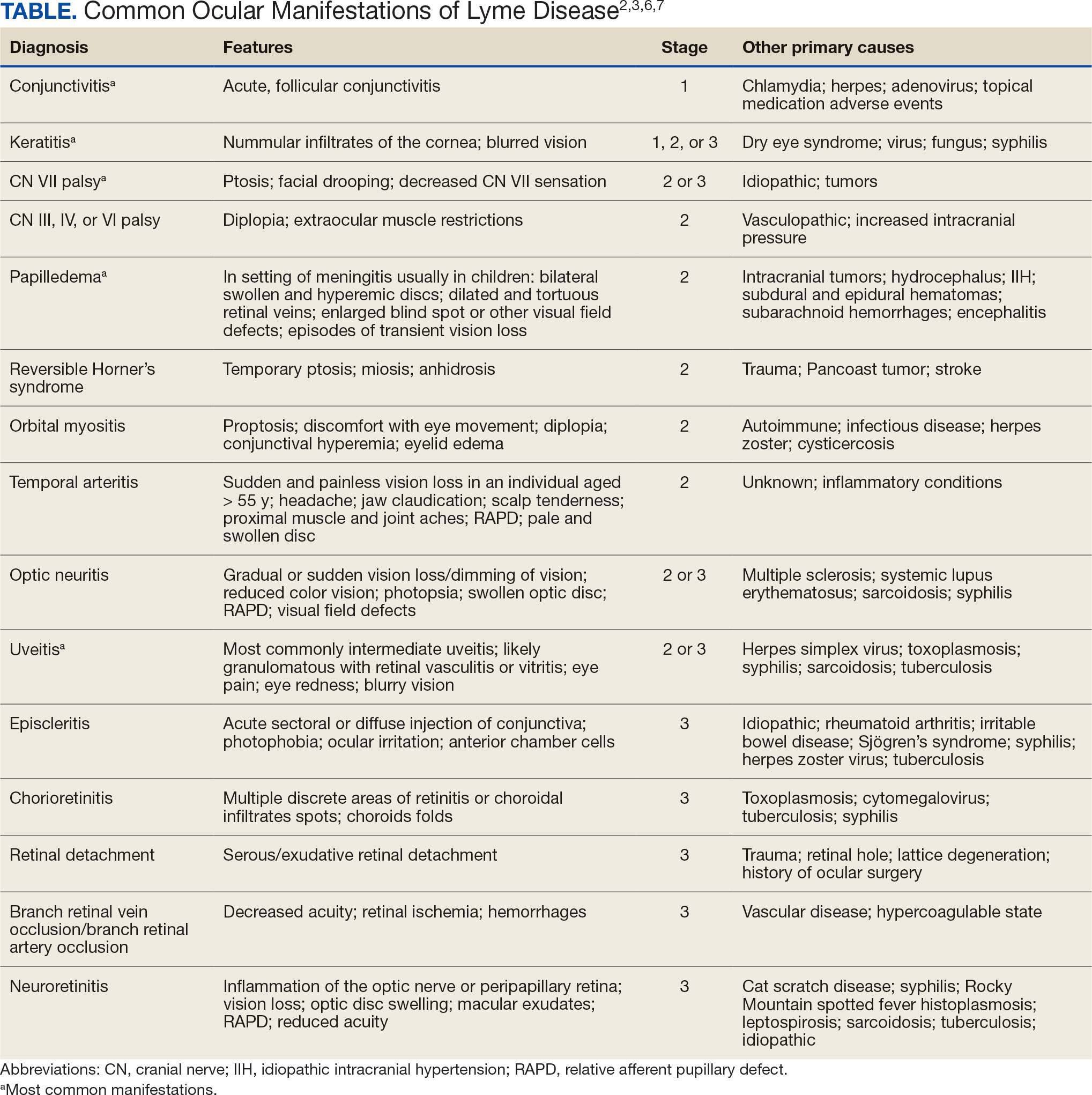

LD occurs in 3 stages: early localized (stage 1), early disseminated (stage 2), and late disseminated (stage 3). In stage 1, patients typically present with erythema migrans (EM) rash (bull’s-eye cutaneous rash) and other nonspecific flu-like symptoms of fever, fatigue, and arthralgia. Stage 2 occurs several weeks to months after the initial infection and the infection has invaded other systemic organs, causing conditions like carditis, meningitis, and arthritis. A small subset of patients may progress to stage 3, which is characterized by chronic arthritis and chronic neurological LD.2,4,5 Ocular manifestations have been well-documented in all stages of LD but are more prevalent in early disseminated disease (Table).2,3,6,7

Indications

Recognizing common ocular manifestations associated with LD will allow eye care practitioners to make a timely diagnosis and initiate treatment. The most common ocular findings from LD include conjunctivitis, keratitis, cranial nerve VII palsy, optic neuritis, granulomatous iridocyclitis, and pars planitis.2,6 While retrospective studies suggest that up to 10% of patients with early localized LD have a nonspecific follicular conjunctivitis, those patients are unlikely to present for ocular evaluation. If a patient does present with an acute conjunctivitis, many clinicians do not consider LD in their differential diagnosis.8 In endemic areas, it is important to query patients for additional symptoms that may indicate LD.

Obtaining a complete patient history is vital in aiding a clinician’s decision to order Lyme serology for suspected LD. Epidemiology, history of geography/travel, pet exposure, sexual history (necessary to rule out other conditions [ie, syphilis] to direct appropriate diagnostic testing), and a complete review of systems should be obtained.2,4 LD may mimic other inflammatory autoimmune conditions or infectious diseases such as syphilis.2,5 This can lead to obtaining unnecessary Lyme serologies or failing to diagnose LD.5,7

Diagnostic testing is not indicated when a patient presents with an asymptomatic tick bite (ie, has no fever, malaise, or EM rash) or if a patient does not live in or has not recently traveled to an endemic area because it would be highly unlikely the patient has LD.9,10 If the patient reports known contact with a tick and has a rash suspicious for EM, the diagnosis may be made without confirmatory testing because EM is pathognomonic for LD.7,11 Serologic testing is not recommended in these cases, particularly if there is a single EM lesion, since the lesion often presents prior to development of an immune response leading to seronegative results.8

Lyme serology is necessary if a patient presents with ocular manifestations known to be associated with LD and resides in, or has recently traveled to, an area where LD is endemic (ie, New England, Minnesota, or Wisconsin).7,12 These criteria are of particular importance: about 50% of patients do not recall a tick bite and 20% to 40% do not present with an EM.2,9

Diagnostic Testing

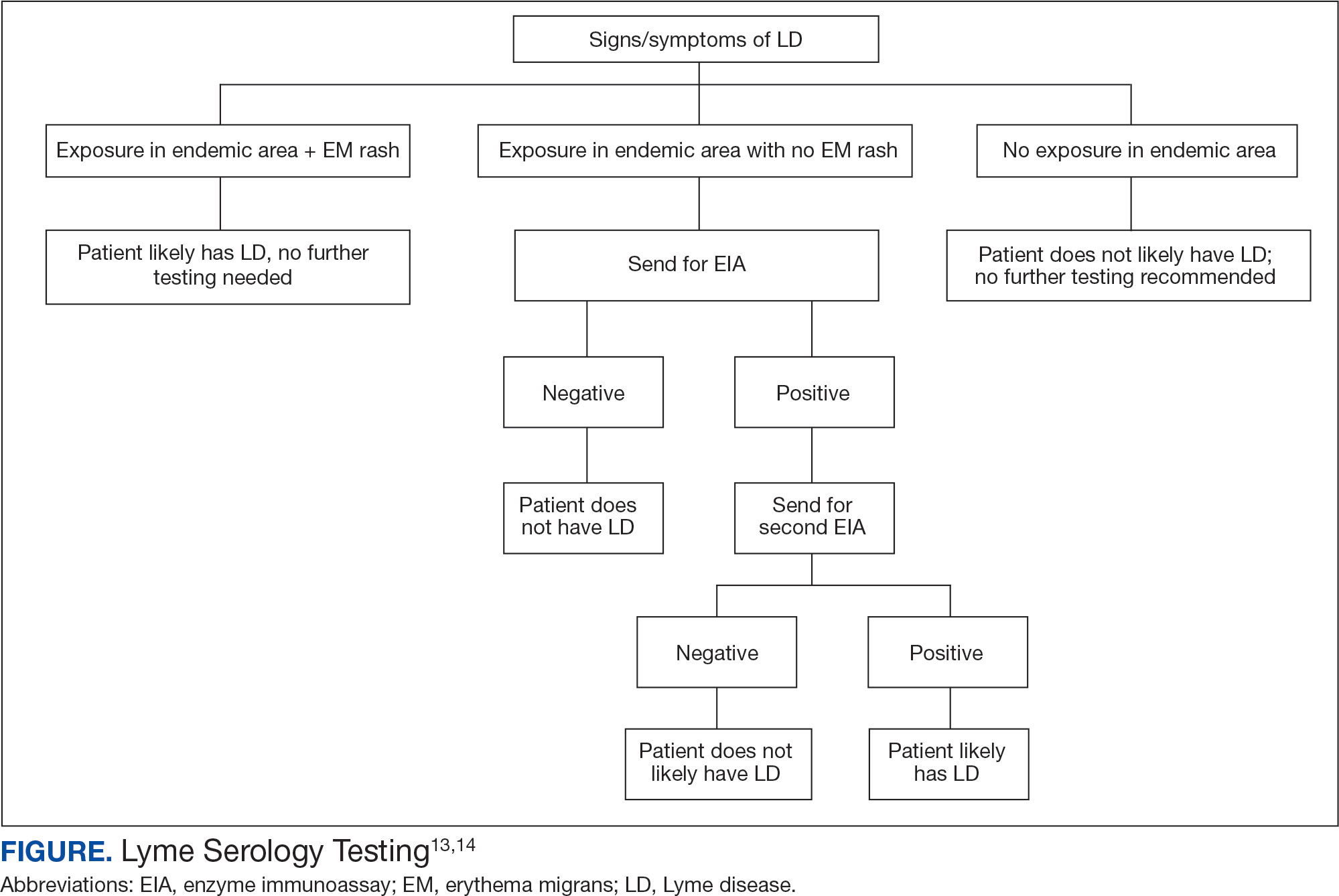

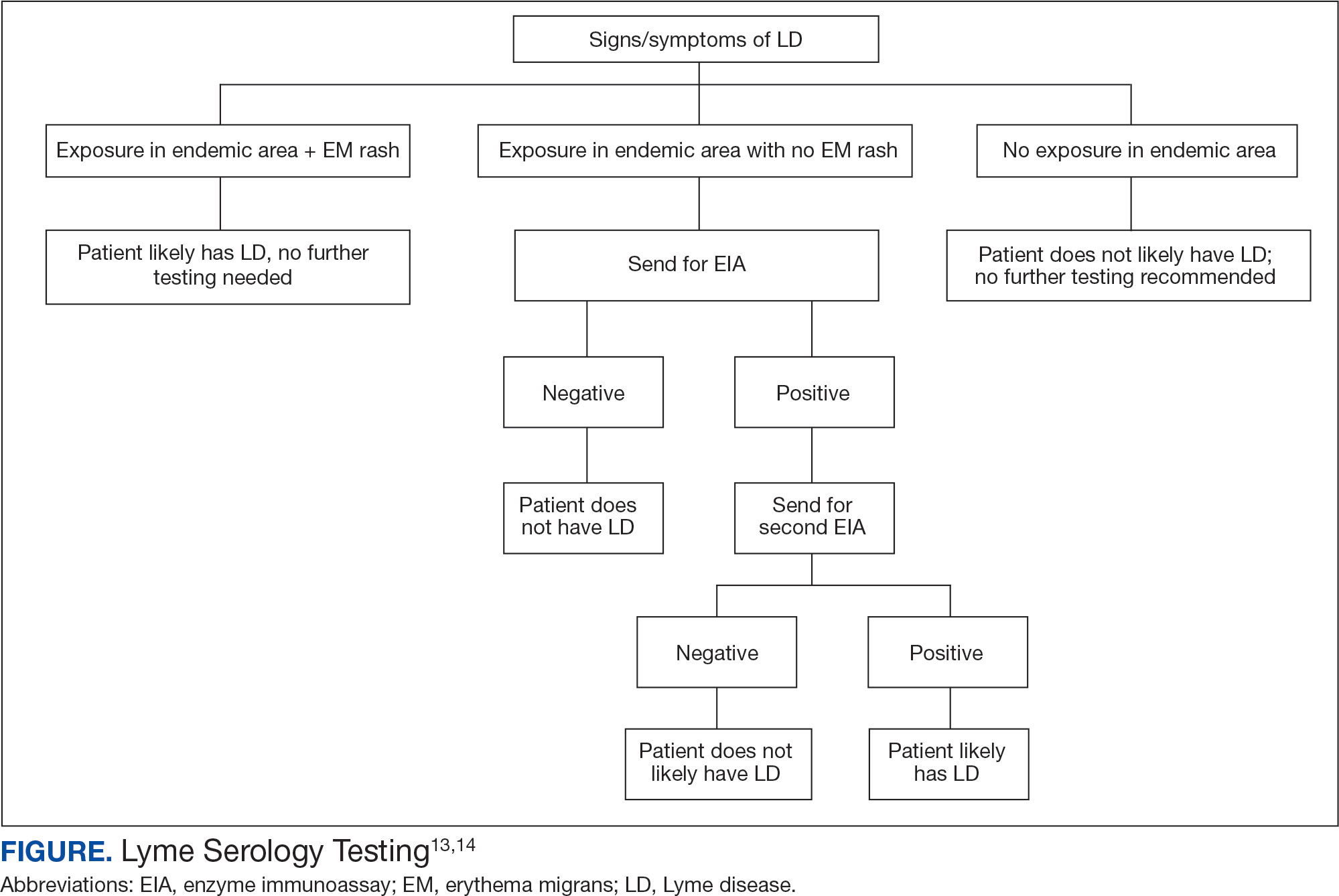

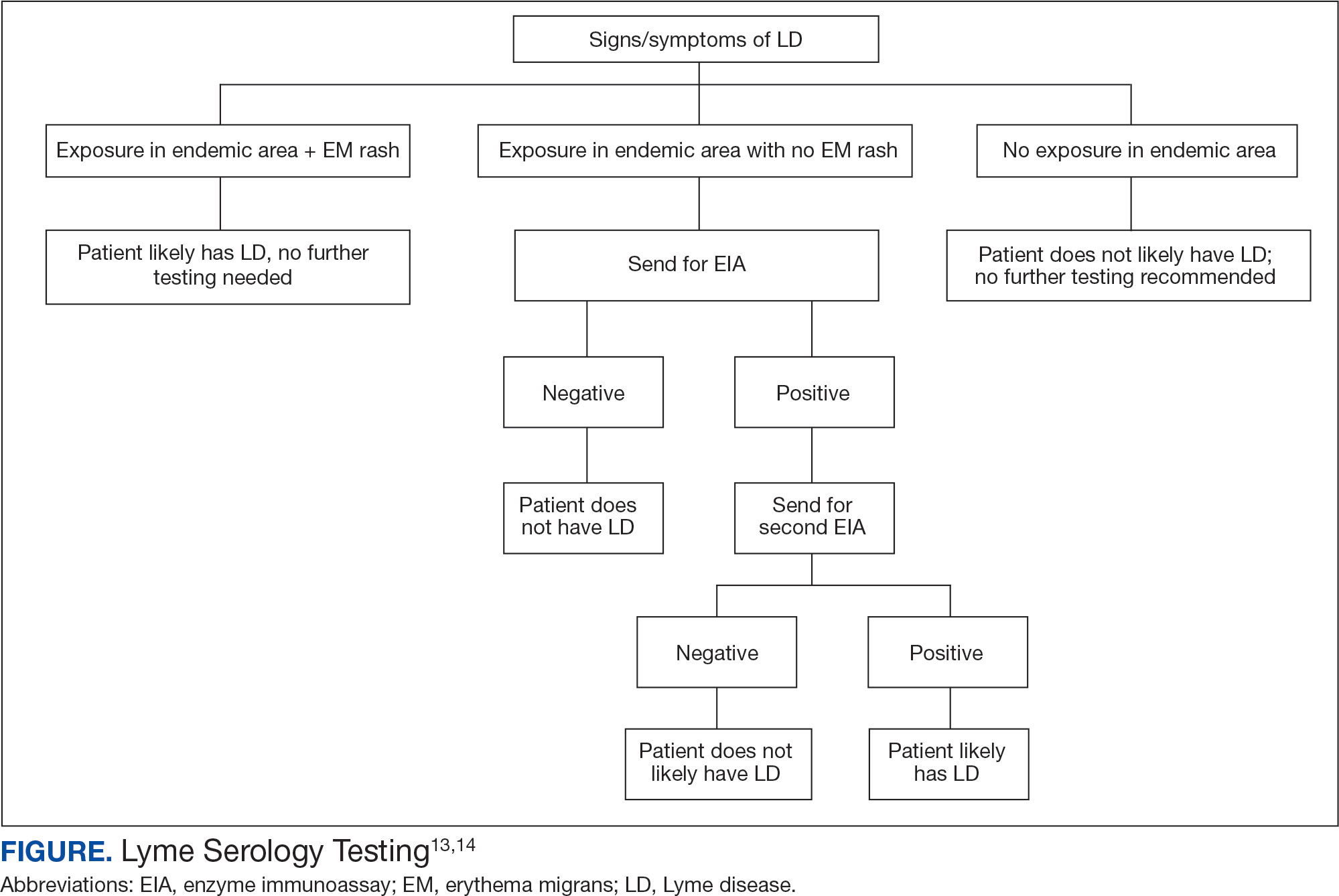

In 2019 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated their testing guidelines to the modified 2-tier testing (MTTT) method. The MTTT first recommends a Lyme enzyme immunoassay (EIA), with a second EIA recommended only if the first is positive.12-14 The MTTT method has better sensitivity in early localized LD compared to standard 2-tier testing.9,11,12 The CDC advises against the use of any laboratory serology tests not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.13 The CDC also advises that LD serology testing should not be performed as a “test for cure,” because even after successful treatment, an individual may still test positive.1,9 Follow-up testing in patients treated early in the disease course (ie, in the setting of EM) may never have an antibody response. In these cases, a negative test should not exclude an LD diagnosis. 9 For patients with suspected neuroborreliosis, a lumbar puncture may not be needed if a patient already has a positive peripheral serology via the MTTT method.12 The Figure depicts a flow chart for the process of ordering and interpreting testing.

Most LD testing, if correlated with clinical disease, is positive after 4 to 6 weeks.9 If an eye disease is noted and the patient has positive Lyme serology, the patient should still be screened for Lyme neuroborreliosis of the central nervous system (CNS). Examination of the fundus for papilledema, review of symptoms of aseptic meningitis, and a careful neurologic examination should be performed.15

If CNS disease is suspected, the patient may need additional CNS testing to support treatment decisions. The 2020 Infectious Diseases Society of America Lyme guidelines recommend to: (1) obtain simultaneous samples of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum for determination of the CSF:serum antibody index; (2) do not obtain CSF serology without measurement of the CSF:serum antibody index; and (3) do not obtain routine polymerase chain reaction or culture of CSF or serum.15 Once an LD diagnosis is confirmed, the CDC recommends a course of 100 mg of oral doxycycline twice daily for 14 to 21 days or an antimicrobial equivalent (eg, amoxicillin) if doxycycline is contraindicated. However, the antimicrobial dosage may vary depending on the stage of LD.11 Patients with confirmed neuroborreliosis should be admitted for 14 days of intravenous ceftriaxone or intravenous penicillin.2

CONCLUSIONS

To ensure timely diagnosis and treatment, eye care clinicians should be familiar with the appropriate diagnostic testing for patients suspected to have ocular manifestations of LD. For patients with suspected LD and a high pretest probability, clinicians should obtain a first-order Lyme EIA.12-14 If testing confirms LD, refer the patient to an infectious disease specialist for antimicrobial treatment and additional management.11

- Kullberg BJ, Vrijmoeth HD, van de Schoor F, Hovius JW. Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2020;369:m1041. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1041

- Zaidman GW. The ocular manifestations of Lyme disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1993;33(1):9-22. doi:10.1097/00004397-199303310-00004

- Lesser RL. Ocular manifestations of Lyme disease. Am J Med. 1995; 98(4A):60S-62S. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80045-x

- Mead P. Epidemiology of Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2022;36(3):495-521. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2022.03.004

- Klig JE. Ophthalmologic complications of systemic disease. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008;26(1):217-viii. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2007.10.003

- Raja H, Starr MR, Bakri SJ. Ocular manifestations of tickborne diseases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61(6):726-744. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.03.011

- Mora P, Carta A. Ocular manifestations of Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6(3):124-125. doi:10.7150/ijms.6.124

- Mikkilä HO, Seppälä IJ, Viljanen MK, Peltomaa MP, Karma A. The expanding clinical spectrum of ocular lyme borreliosis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(3):581-587. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00128-1

- Schriefer ME. Lyme disease diagnosis: serology. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35(4):797-814. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2015.08.001

- Beck AR, Marx GE, Hinckley AF. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention practices for Lyme disease by clinicians, United States, 2013-2015. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(5):609- 617. doi:10.1177/0033354920973235

- Wormser GP, McKenna D, Nowakowski J. Management approaches for suspected and established Lyme disease used at the Lyme disease diagnostic center. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2018;130(15-16):463-467. doi:10.1007/s00508-015-0936-y

- Kobayashi T, Auwaerter PG. Diagnostic testing for Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2022;36(3):605-620. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2022.04.001

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):703. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a4

- Association of Public Health Laboratories. Suggested Reporting Language, Interpretation and Guidance Regarding Lyme Disease Serologic Test Results. April 2024. Accessed December 3, 2024. https://www.aphl.org/aboutAPHL/publications/Documents/ID-2024-Lyme-Disease-Serologic-Testing-Reporting.pdf

- Lantos PM, Rumbaugh P, Bockenstedt L, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(1):e1-e48. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1215

Since Lyme disease (LD) was first identified in 1975, there has been uncertainty regarding the proper diagnostic testing for suspected cases.1 Challenges involved with ordering Lyme serology testing include navigating tests with an array of false negatives and false positives.2 Confounding these challenges is the wide variety of ocular manifestations of LD, ranging from nonspecific conjunctivitis, cranial palsies, and anterior and posterior segment inflammation.2,3 This article provides diagnostic testing guidelines for eye care clinicians who encounter patients with suspected LD.

BACKGROUND

LD is a bacterial infection caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex transmitted by the Ixodes tick genus. There are 4 species of Ixodes ticks that can infect humans, and only 2 have been identified as principal vectors in North America: Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus. The incidence of LD is on the rise due to increasing global temperatures and expanding geographic borders for the organism. Cases in endemic areas range from 10 per 100,000 people to 50 per 100,000 people.4

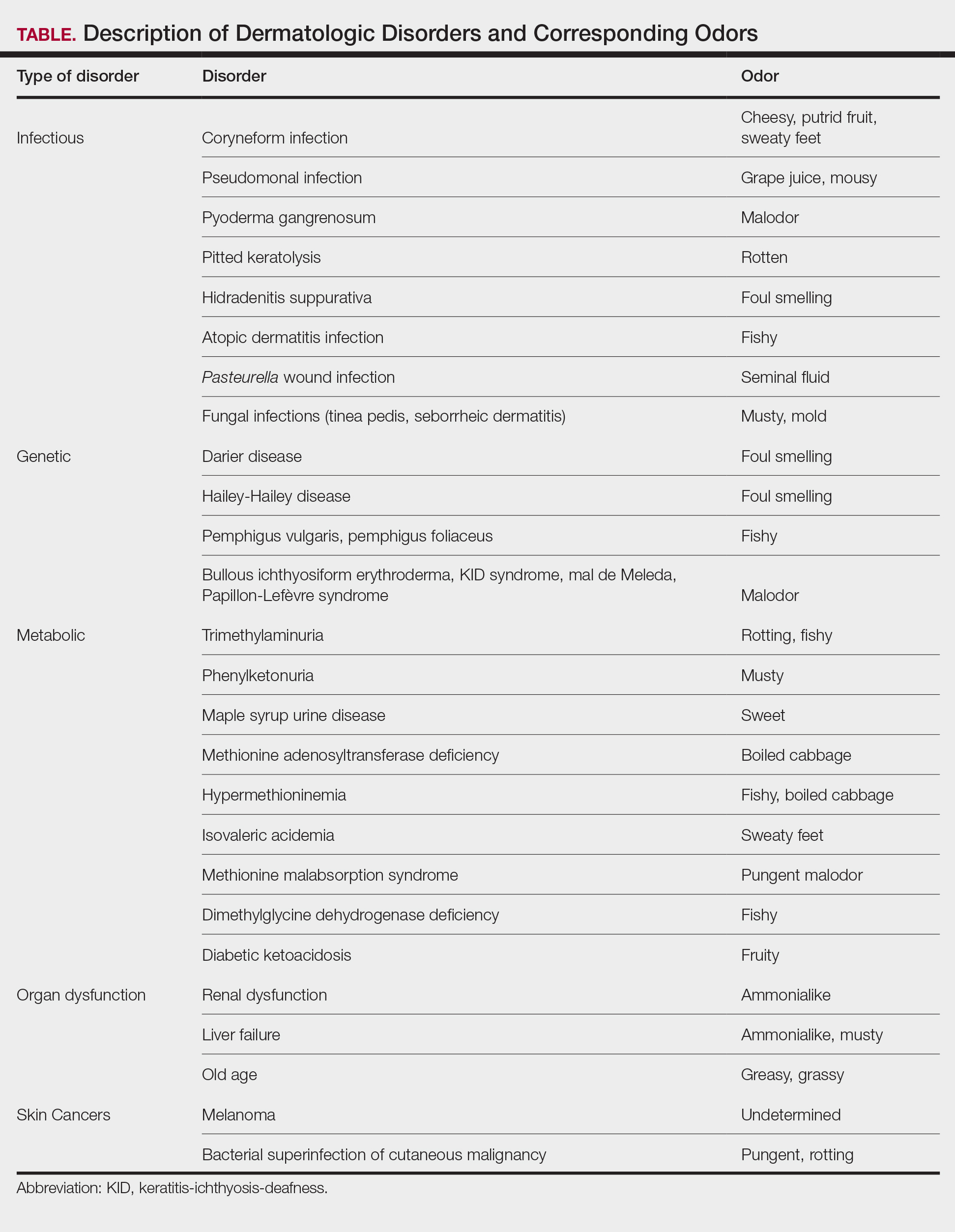

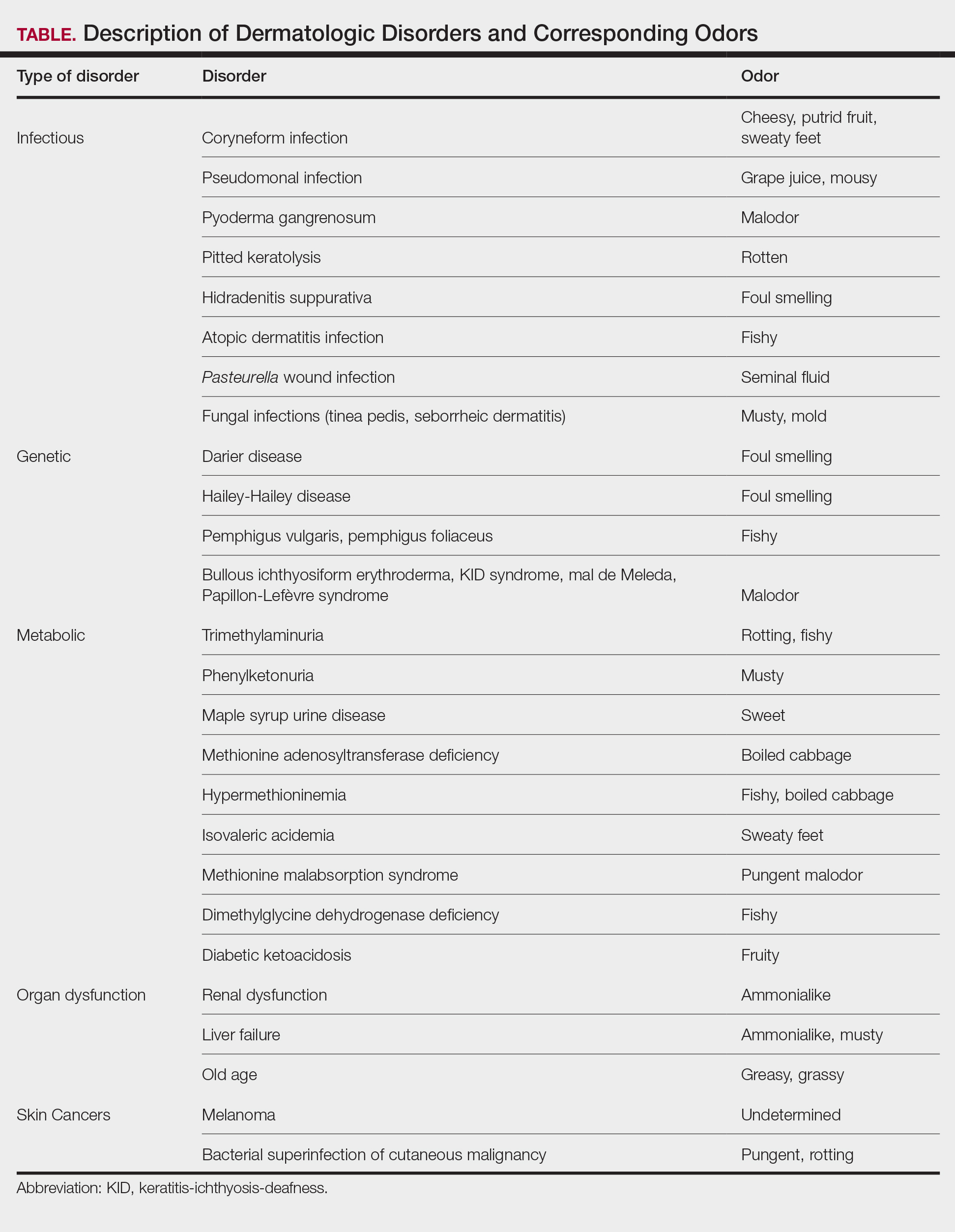

LD occurs in 3 stages: early localized (stage 1), early disseminated (stage 2), and late disseminated (stage 3). In stage 1, patients typically present with erythema migrans (EM) rash (bull’s-eye cutaneous rash) and other nonspecific flu-like symptoms of fever, fatigue, and arthralgia. Stage 2 occurs several weeks to months after the initial infection and the infection has invaded other systemic organs, causing conditions like carditis, meningitis, and arthritis. A small subset of patients may progress to stage 3, which is characterized by chronic arthritis and chronic neurological LD.2,4,5 Ocular manifestations have been well-documented in all stages of LD but are more prevalent in early disseminated disease (Table).2,3,6,7

Indications

Recognizing common ocular manifestations associated with LD will allow eye care practitioners to make a timely diagnosis and initiate treatment. The most common ocular findings from LD include conjunctivitis, keratitis, cranial nerve VII palsy, optic neuritis, granulomatous iridocyclitis, and pars planitis.2,6 While retrospective studies suggest that up to 10% of patients with early localized LD have a nonspecific follicular conjunctivitis, those patients are unlikely to present for ocular evaluation. If a patient does present with an acute conjunctivitis, many clinicians do not consider LD in their differential diagnosis.8 In endemic areas, it is important to query patients for additional symptoms that may indicate LD.

Obtaining a complete patient history is vital in aiding a clinician’s decision to order Lyme serology for suspected LD. Epidemiology, history of geography/travel, pet exposure, sexual history (necessary to rule out other conditions [ie, syphilis] to direct appropriate diagnostic testing), and a complete review of systems should be obtained.2,4 LD may mimic other inflammatory autoimmune conditions or infectious diseases such as syphilis.2,5 This can lead to obtaining unnecessary Lyme serologies or failing to diagnose LD.5,7

Diagnostic testing is not indicated when a patient presents with an asymptomatic tick bite (ie, has no fever, malaise, or EM rash) or if a patient does not live in or has not recently traveled to an endemic area because it would be highly unlikely the patient has LD.9,10 If the patient reports known contact with a tick and has a rash suspicious for EM, the diagnosis may be made without confirmatory testing because EM is pathognomonic for LD.7,11 Serologic testing is not recommended in these cases, particularly if there is a single EM lesion, since the lesion often presents prior to development of an immune response leading to seronegative results.8

Lyme serology is necessary if a patient presents with ocular manifestations known to be associated with LD and resides in, or has recently traveled to, an area where LD is endemic (ie, New England, Minnesota, or Wisconsin).7,12 These criteria are of particular importance: about 50% of patients do not recall a tick bite and 20% to 40% do not present with an EM.2,9

Diagnostic Testing

In 2019 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated their testing guidelines to the modified 2-tier testing (MTTT) method. The MTTT first recommends a Lyme enzyme immunoassay (EIA), with a second EIA recommended only if the first is positive.12-14 The MTTT method has better sensitivity in early localized LD compared to standard 2-tier testing.9,11,12 The CDC advises against the use of any laboratory serology tests not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.13 The CDC also advises that LD serology testing should not be performed as a “test for cure,” because even after successful treatment, an individual may still test positive.1,9 Follow-up testing in patients treated early in the disease course (ie, in the setting of EM) may never have an antibody response. In these cases, a negative test should not exclude an LD diagnosis. 9 For patients with suspected neuroborreliosis, a lumbar puncture may not be needed if a patient already has a positive peripheral serology via the MTTT method.12 The Figure depicts a flow chart for the process of ordering and interpreting testing.

Most LD testing, if correlated with clinical disease, is positive after 4 to 6 weeks.9 If an eye disease is noted and the patient has positive Lyme serology, the patient should still be screened for Lyme neuroborreliosis of the central nervous system (CNS). Examination of the fundus for papilledema, review of symptoms of aseptic meningitis, and a careful neurologic examination should be performed.15

If CNS disease is suspected, the patient may need additional CNS testing to support treatment decisions. The 2020 Infectious Diseases Society of America Lyme guidelines recommend to: (1) obtain simultaneous samples of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum for determination of the CSF:serum antibody index; (2) do not obtain CSF serology without measurement of the CSF:serum antibody index; and (3) do not obtain routine polymerase chain reaction or culture of CSF or serum.15 Once an LD diagnosis is confirmed, the CDC recommends a course of 100 mg of oral doxycycline twice daily for 14 to 21 days or an antimicrobial equivalent (eg, amoxicillin) if doxycycline is contraindicated. However, the antimicrobial dosage may vary depending on the stage of LD.11 Patients with confirmed neuroborreliosis should be admitted for 14 days of intravenous ceftriaxone or intravenous penicillin.2

CONCLUSIONS

To ensure timely diagnosis and treatment, eye care clinicians should be familiar with the appropriate diagnostic testing for patients suspected to have ocular manifestations of LD. For patients with suspected LD and a high pretest probability, clinicians should obtain a first-order Lyme EIA.12-14 If testing confirms LD, refer the patient to an infectious disease specialist for antimicrobial treatment and additional management.11

Since Lyme disease (LD) was first identified in 1975, there has been uncertainty regarding the proper diagnostic testing for suspected cases.1 Challenges involved with ordering Lyme serology testing include navigating tests with an array of false negatives and false positives.2 Confounding these challenges is the wide variety of ocular manifestations of LD, ranging from nonspecific conjunctivitis, cranial palsies, and anterior and posterior segment inflammation.2,3 This article provides diagnostic testing guidelines for eye care clinicians who encounter patients with suspected LD.

BACKGROUND

LD is a bacterial infection caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex transmitted by the Ixodes tick genus. There are 4 species of Ixodes ticks that can infect humans, and only 2 have been identified as principal vectors in North America: Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus. The incidence of LD is on the rise due to increasing global temperatures and expanding geographic borders for the organism. Cases in endemic areas range from 10 per 100,000 people to 50 per 100,000 people.4

LD occurs in 3 stages: early localized (stage 1), early disseminated (stage 2), and late disseminated (stage 3). In stage 1, patients typically present with erythema migrans (EM) rash (bull’s-eye cutaneous rash) and other nonspecific flu-like symptoms of fever, fatigue, and arthralgia. Stage 2 occurs several weeks to months after the initial infection and the infection has invaded other systemic organs, causing conditions like carditis, meningitis, and arthritis. A small subset of patients may progress to stage 3, which is characterized by chronic arthritis and chronic neurological LD.2,4,5 Ocular manifestations have been well-documented in all stages of LD but are more prevalent in early disseminated disease (Table).2,3,6,7

Indications

Recognizing common ocular manifestations associated with LD will allow eye care practitioners to make a timely diagnosis and initiate treatment. The most common ocular findings from LD include conjunctivitis, keratitis, cranial nerve VII palsy, optic neuritis, granulomatous iridocyclitis, and pars planitis.2,6 While retrospective studies suggest that up to 10% of patients with early localized LD have a nonspecific follicular conjunctivitis, those patients are unlikely to present for ocular evaluation. If a patient does present with an acute conjunctivitis, many clinicians do not consider LD in their differential diagnosis.8 In endemic areas, it is important to query patients for additional symptoms that may indicate LD.

Obtaining a complete patient history is vital in aiding a clinician’s decision to order Lyme serology for suspected LD. Epidemiology, history of geography/travel, pet exposure, sexual history (necessary to rule out other conditions [ie, syphilis] to direct appropriate diagnostic testing), and a complete review of systems should be obtained.2,4 LD may mimic other inflammatory autoimmune conditions or infectious diseases such as syphilis.2,5 This can lead to obtaining unnecessary Lyme serologies or failing to diagnose LD.5,7

Diagnostic testing is not indicated when a patient presents with an asymptomatic tick bite (ie, has no fever, malaise, or EM rash) or if a patient does not live in or has not recently traveled to an endemic area because it would be highly unlikely the patient has LD.9,10 If the patient reports known contact with a tick and has a rash suspicious for EM, the diagnosis may be made without confirmatory testing because EM is pathognomonic for LD.7,11 Serologic testing is not recommended in these cases, particularly if there is a single EM lesion, since the lesion often presents prior to development of an immune response leading to seronegative results.8

Lyme serology is necessary if a patient presents with ocular manifestations known to be associated with LD and resides in, or has recently traveled to, an area where LD is endemic (ie, New England, Minnesota, or Wisconsin).7,12 These criteria are of particular importance: about 50% of patients do not recall a tick bite and 20% to 40% do not present with an EM.2,9

Diagnostic Testing

In 2019 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated their testing guidelines to the modified 2-tier testing (MTTT) method. The MTTT first recommends a Lyme enzyme immunoassay (EIA), with a second EIA recommended only if the first is positive.12-14 The MTTT method has better sensitivity in early localized LD compared to standard 2-tier testing.9,11,12 The CDC advises against the use of any laboratory serology tests not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.13 The CDC also advises that LD serology testing should not be performed as a “test for cure,” because even after successful treatment, an individual may still test positive.1,9 Follow-up testing in patients treated early in the disease course (ie, in the setting of EM) may never have an antibody response. In these cases, a negative test should not exclude an LD diagnosis. 9 For patients with suspected neuroborreliosis, a lumbar puncture may not be needed if a patient already has a positive peripheral serology via the MTTT method.12 The Figure depicts a flow chart for the process of ordering and interpreting testing.

Most LD testing, if correlated with clinical disease, is positive after 4 to 6 weeks.9 If an eye disease is noted and the patient has positive Lyme serology, the patient should still be screened for Lyme neuroborreliosis of the central nervous system (CNS). Examination of the fundus for papilledema, review of symptoms of aseptic meningitis, and a careful neurologic examination should be performed.15

If CNS disease is suspected, the patient may need additional CNS testing to support treatment decisions. The 2020 Infectious Diseases Society of America Lyme guidelines recommend to: (1) obtain simultaneous samples of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum for determination of the CSF:serum antibody index; (2) do not obtain CSF serology without measurement of the CSF:serum antibody index; and (3) do not obtain routine polymerase chain reaction or culture of CSF or serum.15 Once an LD diagnosis is confirmed, the CDC recommends a course of 100 mg of oral doxycycline twice daily for 14 to 21 days or an antimicrobial equivalent (eg, amoxicillin) if doxycycline is contraindicated. However, the antimicrobial dosage may vary depending on the stage of LD.11 Patients with confirmed neuroborreliosis should be admitted for 14 days of intravenous ceftriaxone or intravenous penicillin.2

CONCLUSIONS

To ensure timely diagnosis and treatment, eye care clinicians should be familiar with the appropriate diagnostic testing for patients suspected to have ocular manifestations of LD. For patients with suspected LD and a high pretest probability, clinicians should obtain a first-order Lyme EIA.12-14 If testing confirms LD, refer the patient to an infectious disease specialist for antimicrobial treatment and additional management.11

- Kullberg BJ, Vrijmoeth HD, van de Schoor F, Hovius JW. Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2020;369:m1041. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1041

- Zaidman GW. The ocular manifestations of Lyme disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1993;33(1):9-22. doi:10.1097/00004397-199303310-00004

- Lesser RL. Ocular manifestations of Lyme disease. Am J Med. 1995; 98(4A):60S-62S. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80045-x

- Mead P. Epidemiology of Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2022;36(3):495-521. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2022.03.004

- Klig JE. Ophthalmologic complications of systemic disease. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008;26(1):217-viii. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2007.10.003

- Raja H, Starr MR, Bakri SJ. Ocular manifestations of tickborne diseases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61(6):726-744. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.03.011

- Mora P, Carta A. Ocular manifestations of Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6(3):124-125. doi:10.7150/ijms.6.124

- Mikkilä HO, Seppälä IJ, Viljanen MK, Peltomaa MP, Karma A. The expanding clinical spectrum of ocular lyme borreliosis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(3):581-587. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00128-1

- Schriefer ME. Lyme disease diagnosis: serology. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35(4):797-814. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2015.08.001

- Beck AR, Marx GE, Hinckley AF. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention practices for Lyme disease by clinicians, United States, 2013-2015. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(5):609- 617. doi:10.1177/0033354920973235

- Wormser GP, McKenna D, Nowakowski J. Management approaches for suspected and established Lyme disease used at the Lyme disease diagnostic center. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2018;130(15-16):463-467. doi:10.1007/s00508-015-0936-y

- Kobayashi T, Auwaerter PG. Diagnostic testing for Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2022;36(3):605-620. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2022.04.001

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):703. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a4

- Association of Public Health Laboratories. Suggested Reporting Language, Interpretation and Guidance Regarding Lyme Disease Serologic Test Results. April 2024. Accessed December 3, 2024. https://www.aphl.org/aboutAPHL/publications/Documents/ID-2024-Lyme-Disease-Serologic-Testing-Reporting.pdf

- Lantos PM, Rumbaugh P, Bockenstedt L, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(1):e1-e48. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1215

- Kullberg BJ, Vrijmoeth HD, van de Schoor F, Hovius JW. Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2020;369:m1041. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1041

- Zaidman GW. The ocular manifestations of Lyme disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1993;33(1):9-22. doi:10.1097/00004397-199303310-00004

- Lesser RL. Ocular manifestations of Lyme disease. Am J Med. 1995; 98(4A):60S-62S. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80045-x

- Mead P. Epidemiology of Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2022;36(3):495-521. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2022.03.004

- Klig JE. Ophthalmologic complications of systemic disease. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008;26(1):217-viii. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2007.10.003

- Raja H, Starr MR, Bakri SJ. Ocular manifestations of tickborne diseases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61(6):726-744. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.03.011

- Mora P, Carta A. Ocular manifestations of Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6(3):124-125. doi:10.7150/ijms.6.124

- Mikkilä HO, Seppälä IJ, Viljanen MK, Peltomaa MP, Karma A. The expanding clinical spectrum of ocular lyme borreliosis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(3):581-587. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00128-1

- Schriefer ME. Lyme disease diagnosis: serology. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35(4):797-814. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2015.08.001

- Beck AR, Marx GE, Hinckley AF. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention practices for Lyme disease by clinicians, United States, 2013-2015. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(5):609- 617. doi:10.1177/0033354920973235

- Wormser GP, McKenna D, Nowakowski J. Management approaches for suspected and established Lyme disease used at the Lyme disease diagnostic center. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2018;130(15-16):463-467. doi:10.1007/s00508-015-0936-y

- Kobayashi T, Auwaerter PG. Diagnostic testing for Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2022;36(3):605-620. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2022.04.001

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):703. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a4

- Association of Public Health Laboratories. Suggested Reporting Language, Interpretation and Guidance Regarding Lyme Disease Serologic Test Results. April 2024. Accessed December 3, 2024. https://www.aphl.org/aboutAPHL/publications/Documents/ID-2024-Lyme-Disease-Serologic-Testing-Reporting.pdf

- Lantos PM, Rumbaugh P, Bockenstedt L, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(1):e1-e48. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1215

Diagnostic Testing for Patients With Suspected Ocular Manifestations of Lyme Disease

Diagnostic Testing for Patients With Suspected Ocular Manifestations of Lyme Disease

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

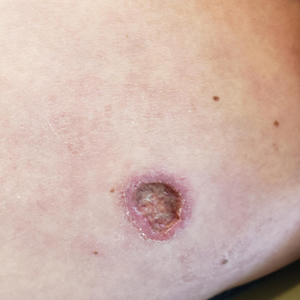

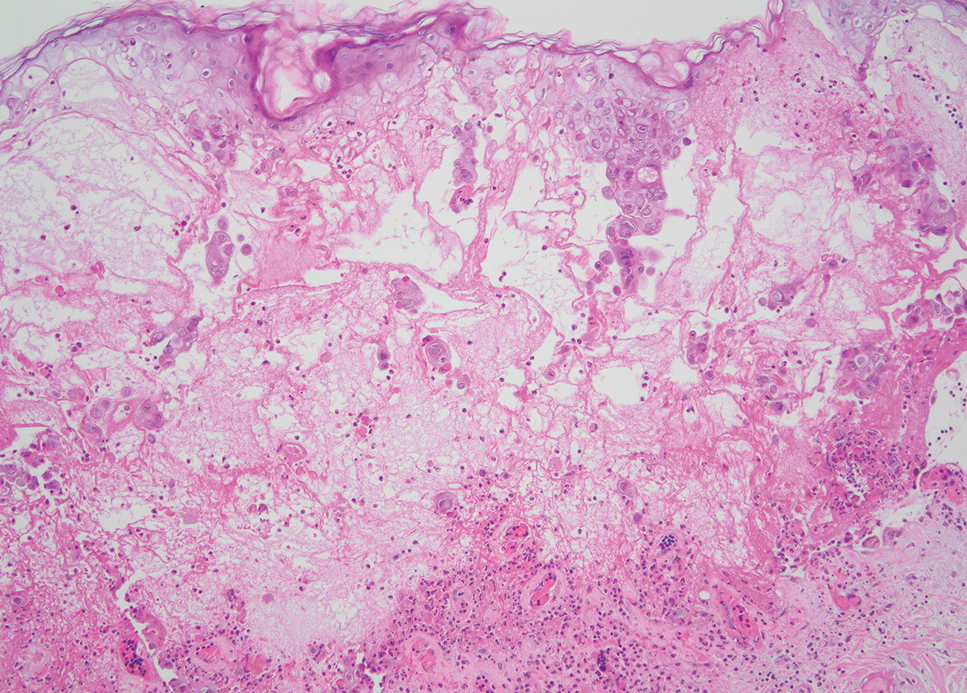

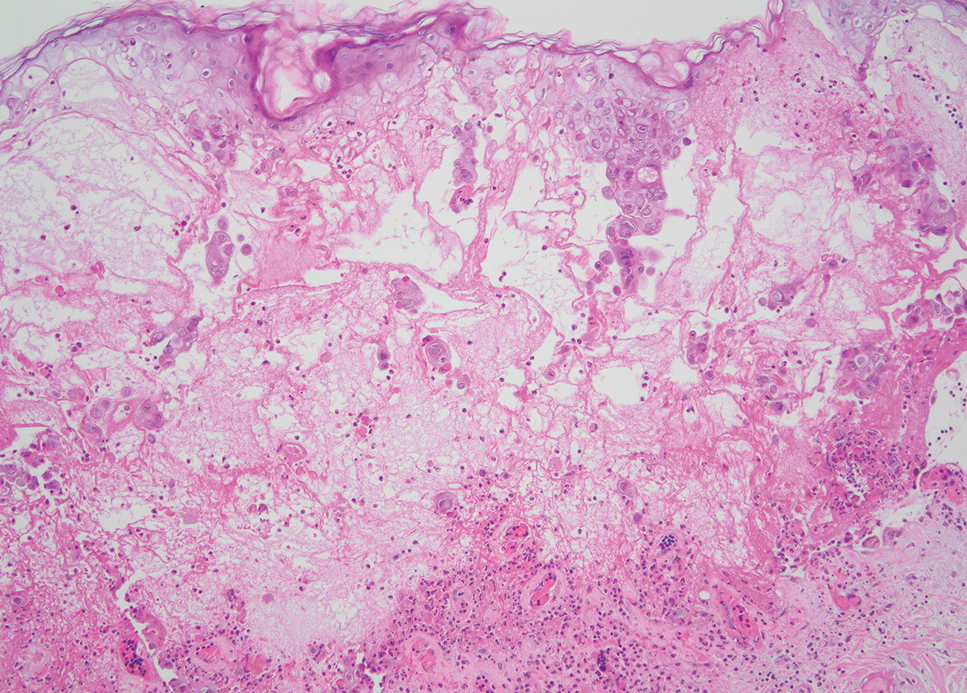

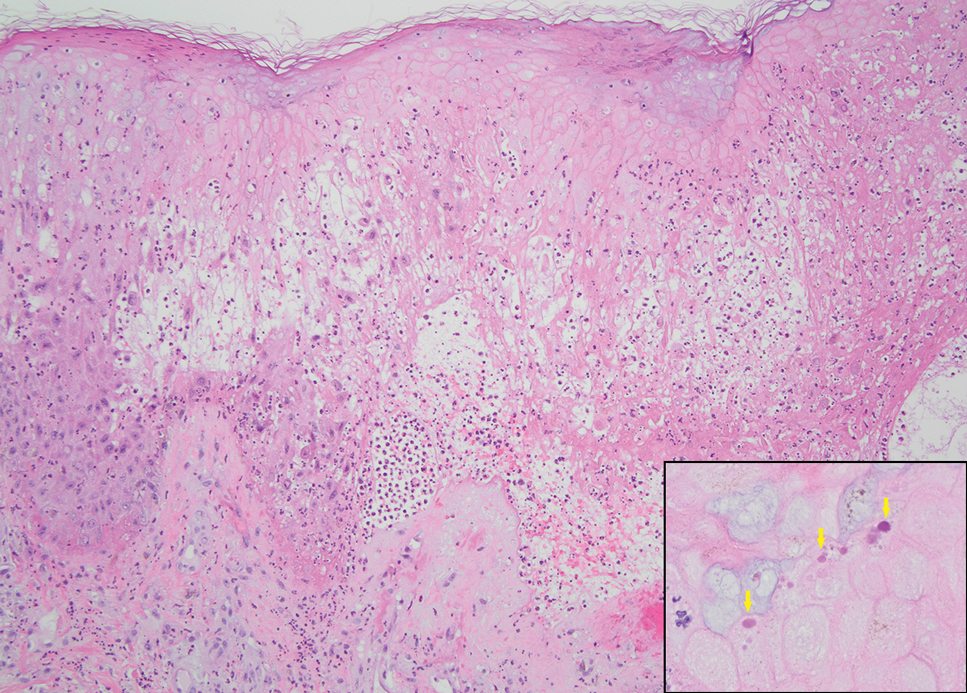

The biopsy results revealed amastigotes at the periphery of parasitized histiocytes, consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed Leishmania guyanensis species complex, which includes both L guyanensis and Leishmania panamensis. In this case of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis (Figure 1), our patient received a prolonged course of systemic therapy with oral miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. At the most recent follow-up appointment, she showed ongoing resolution of ulcerations, subcutaneous plaques, and lymphadenopathy on the trunk and face, but development of subcutaneous nodules continued on the arms and legs. At the next follow-up, physical examination revealed that the lesions slowly started to fade.

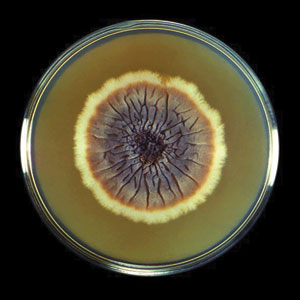

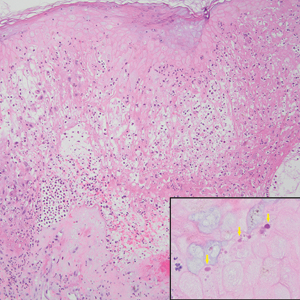

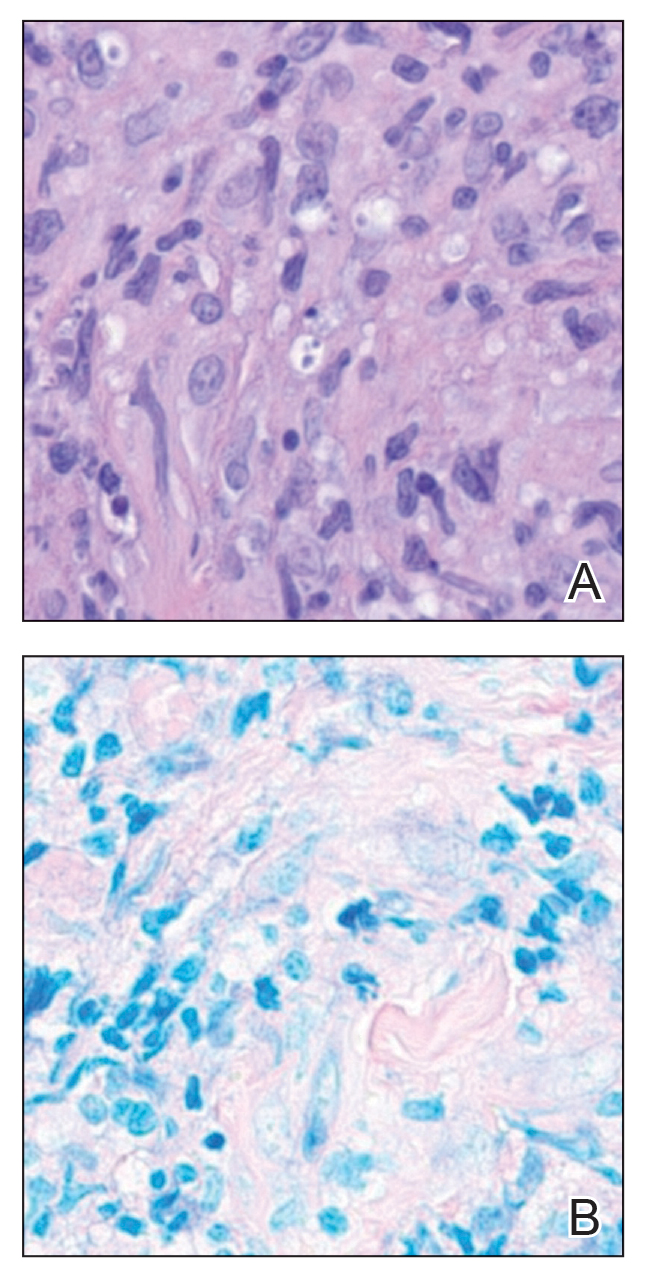

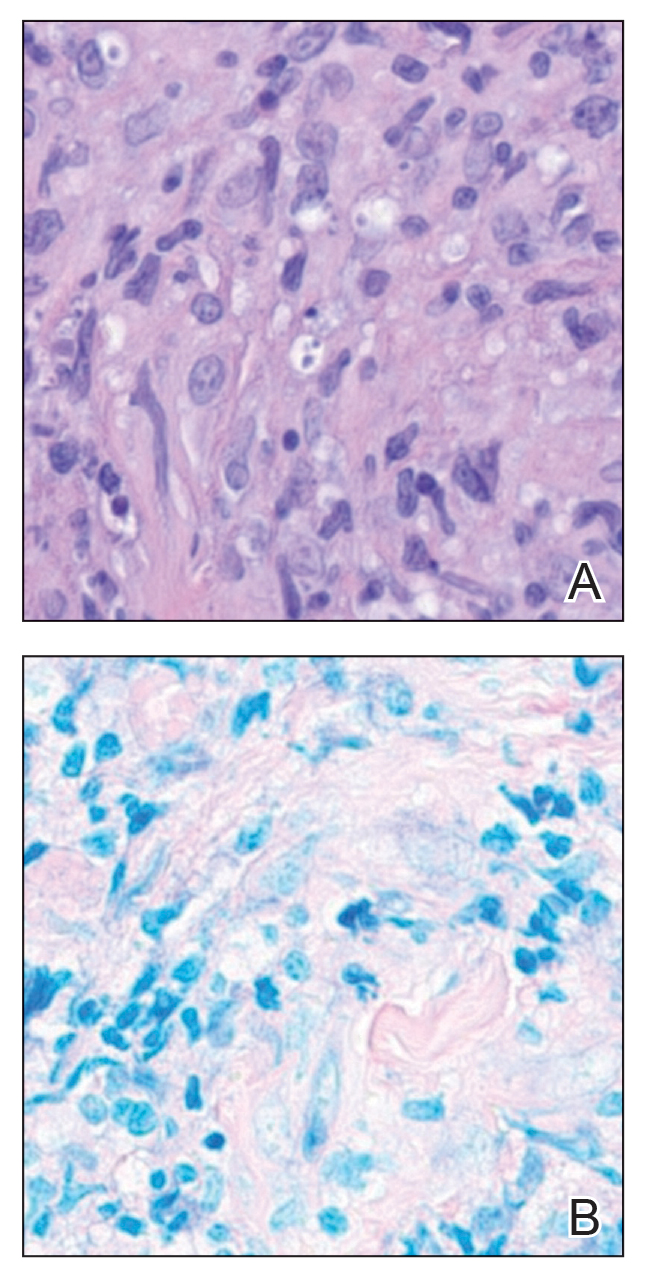

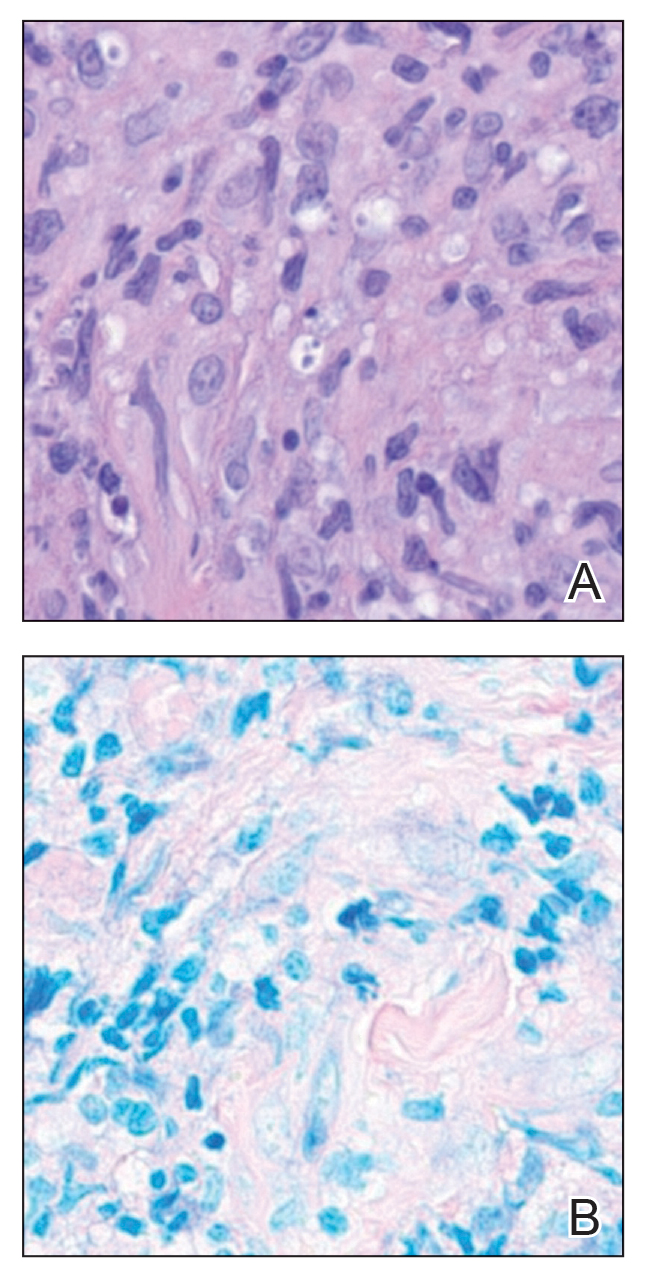

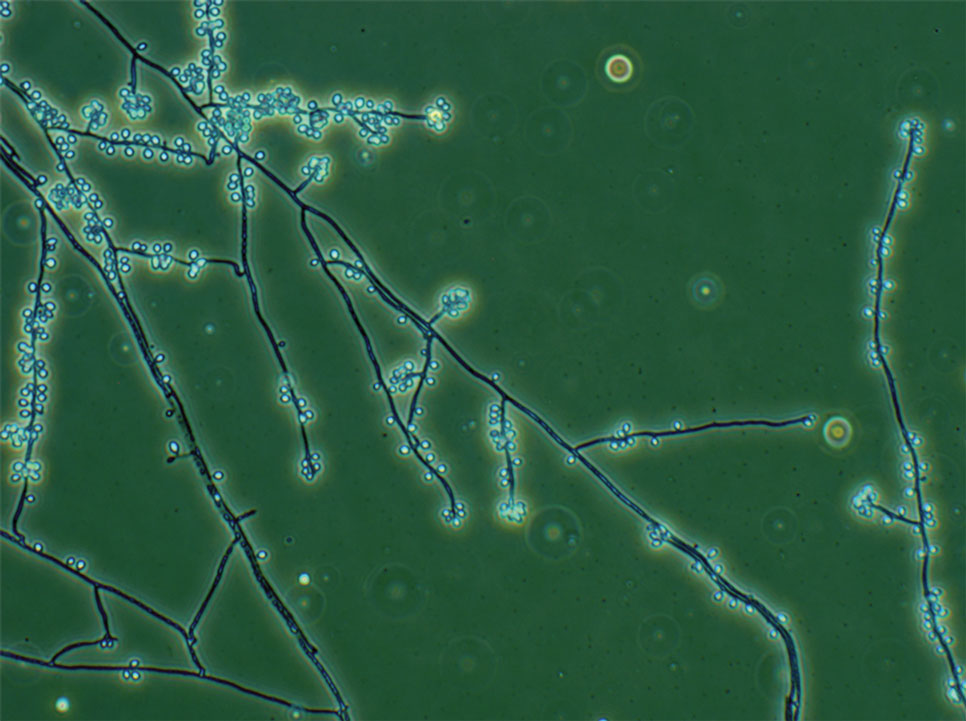

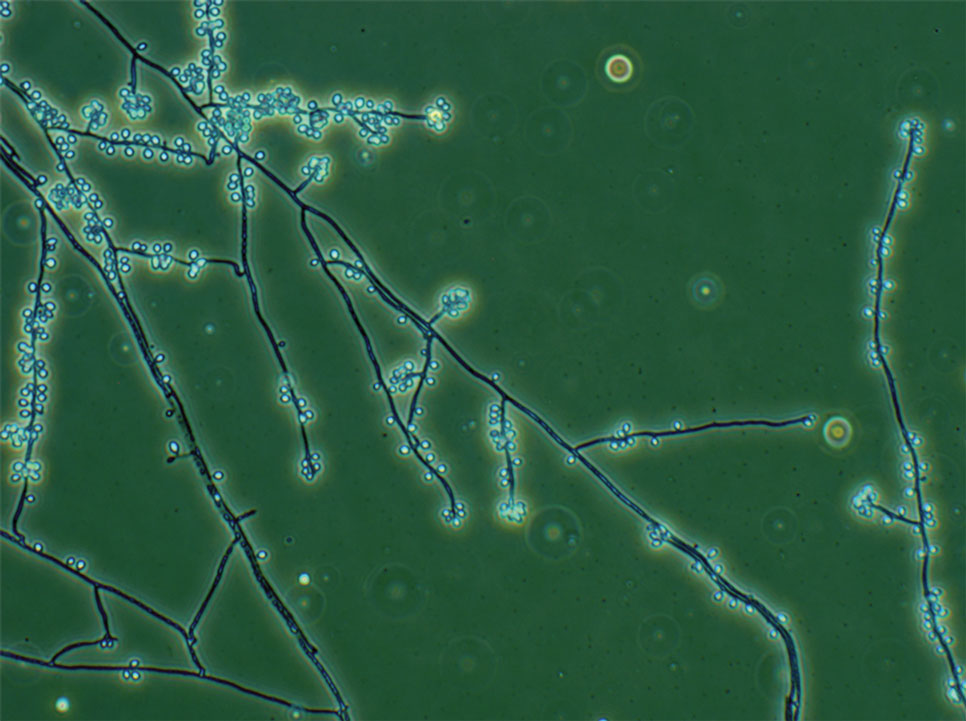

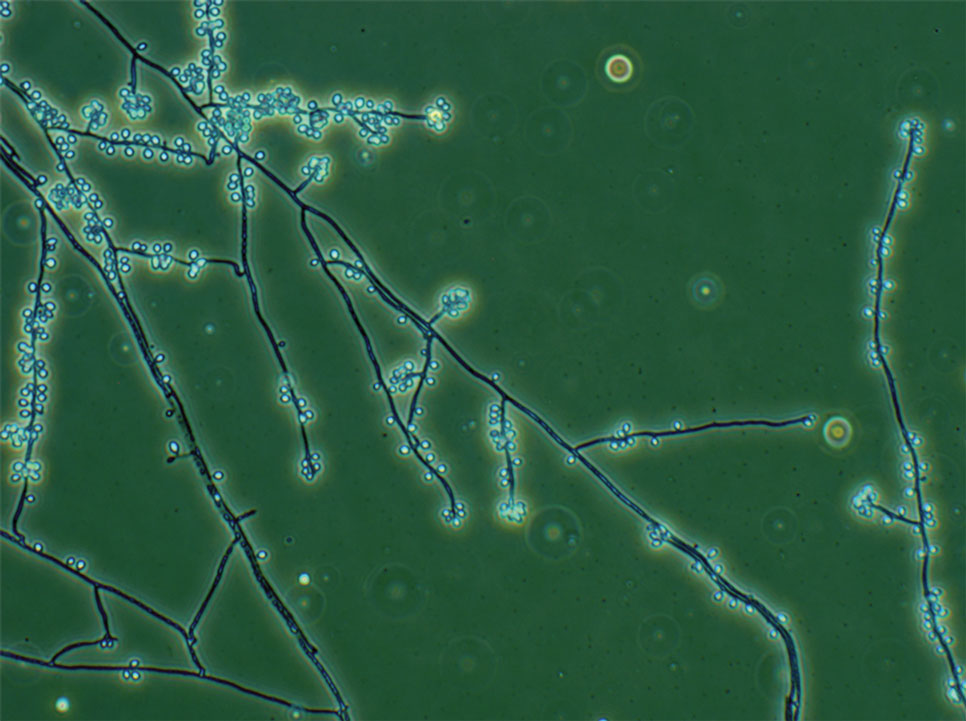

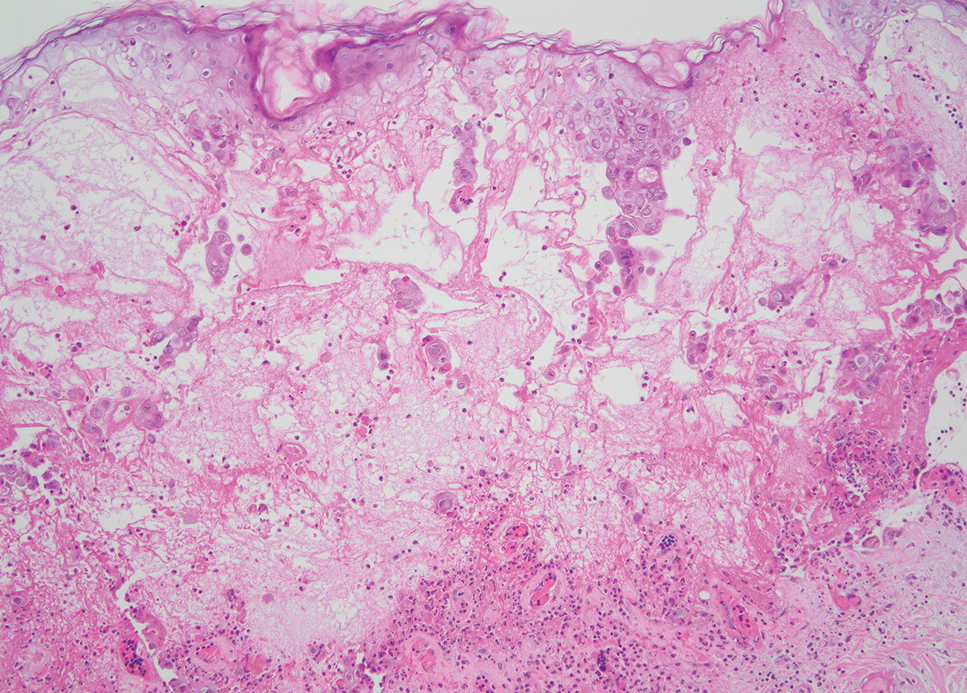

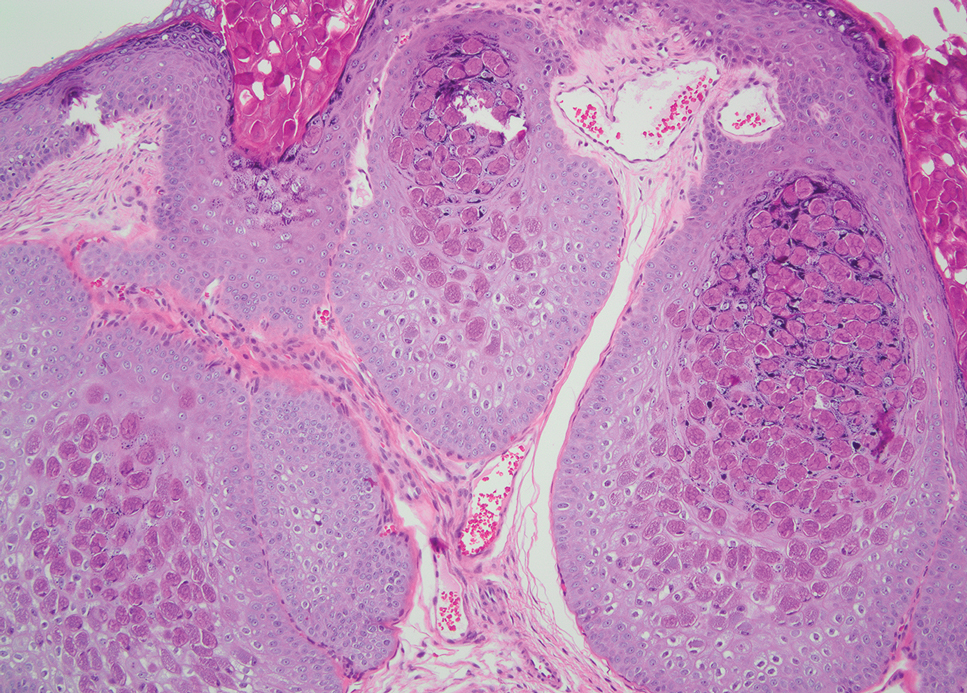

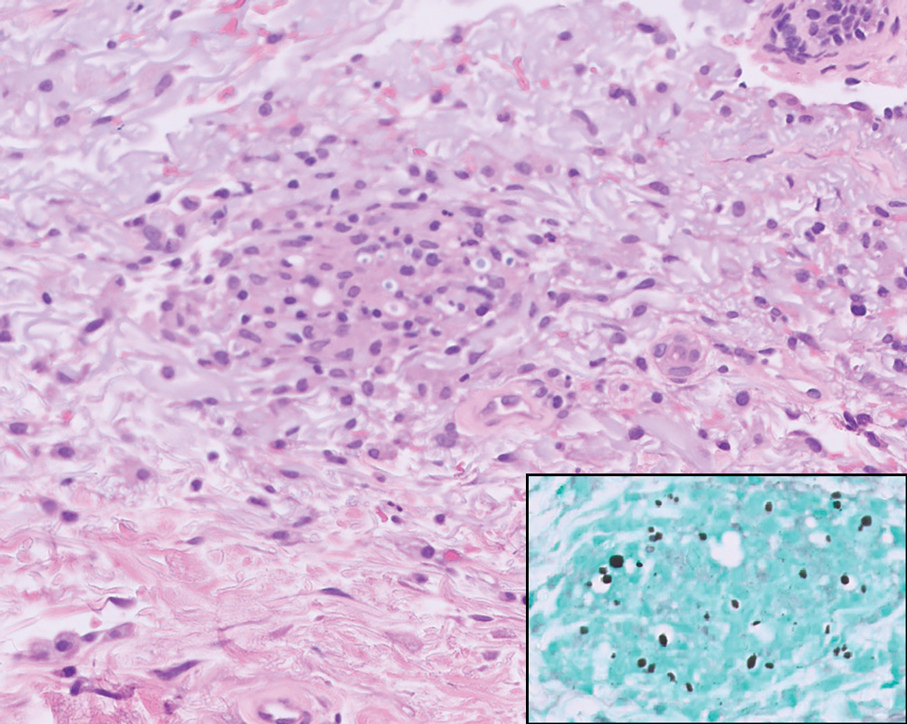

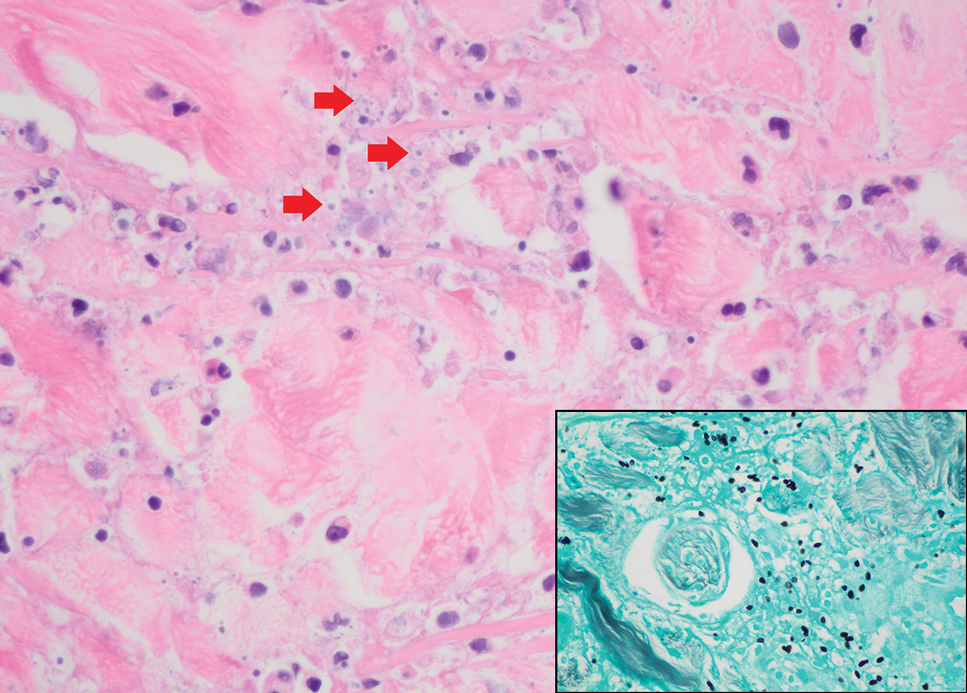

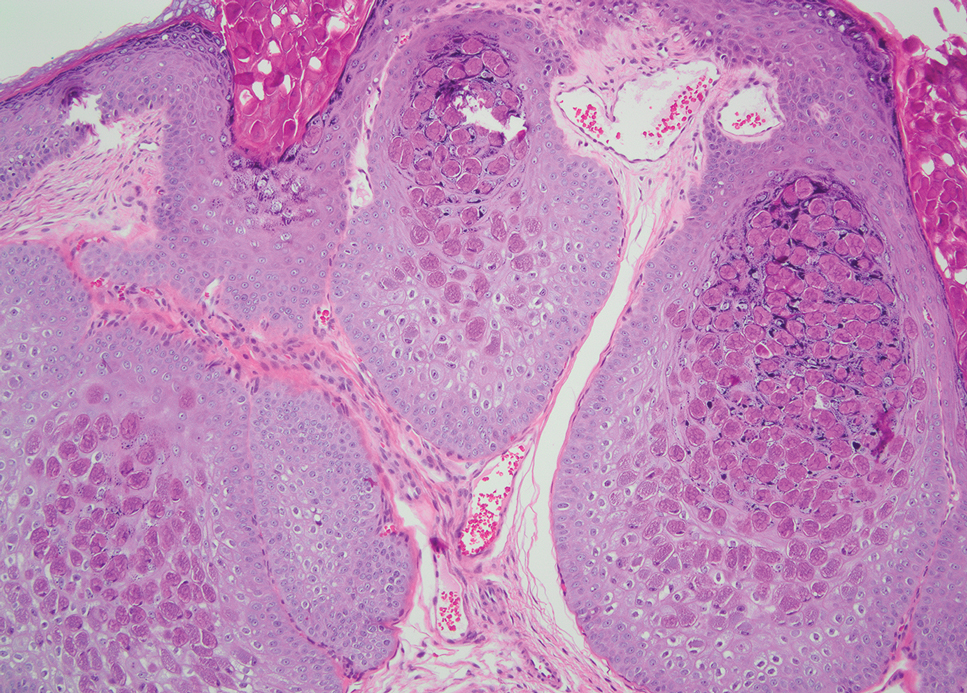

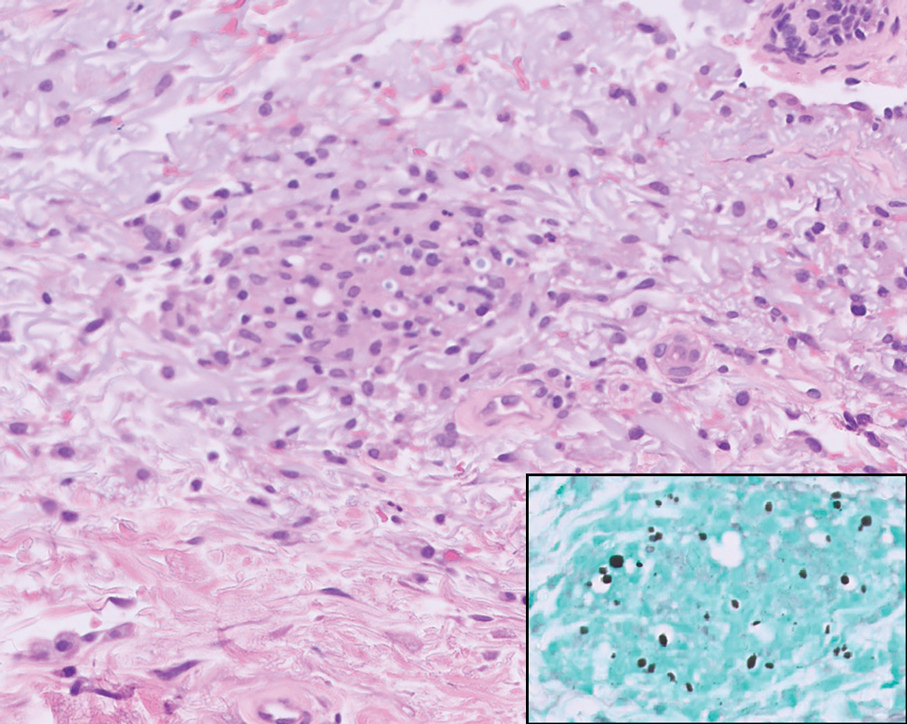

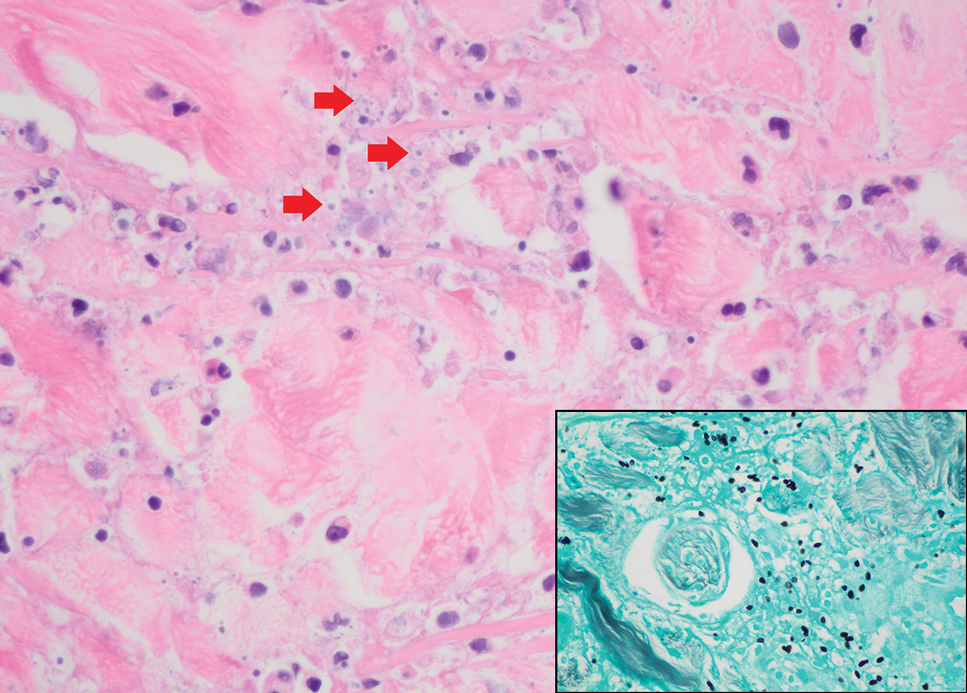

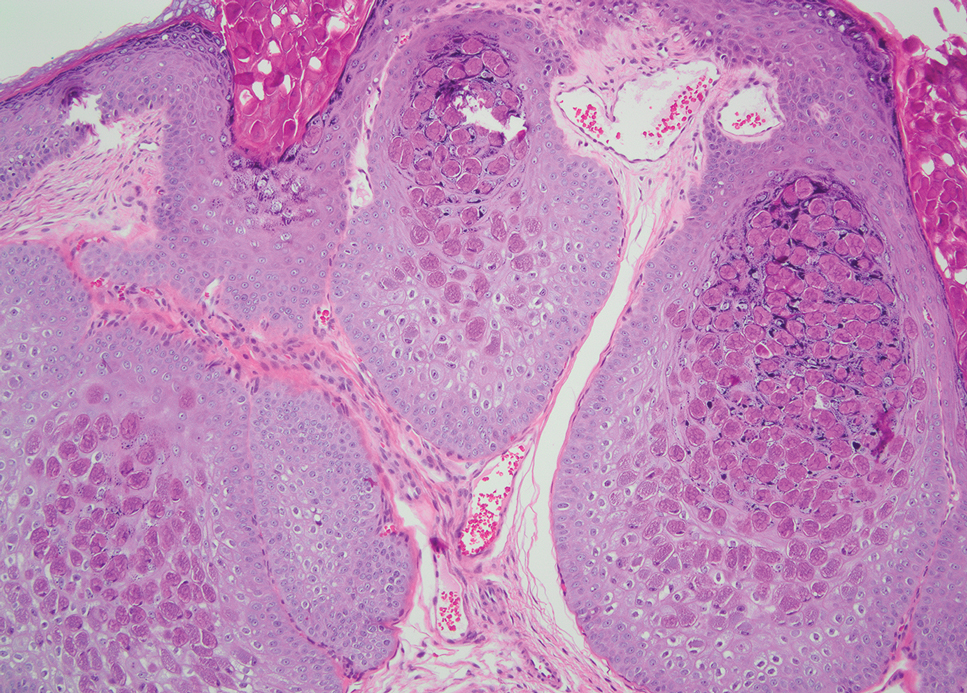

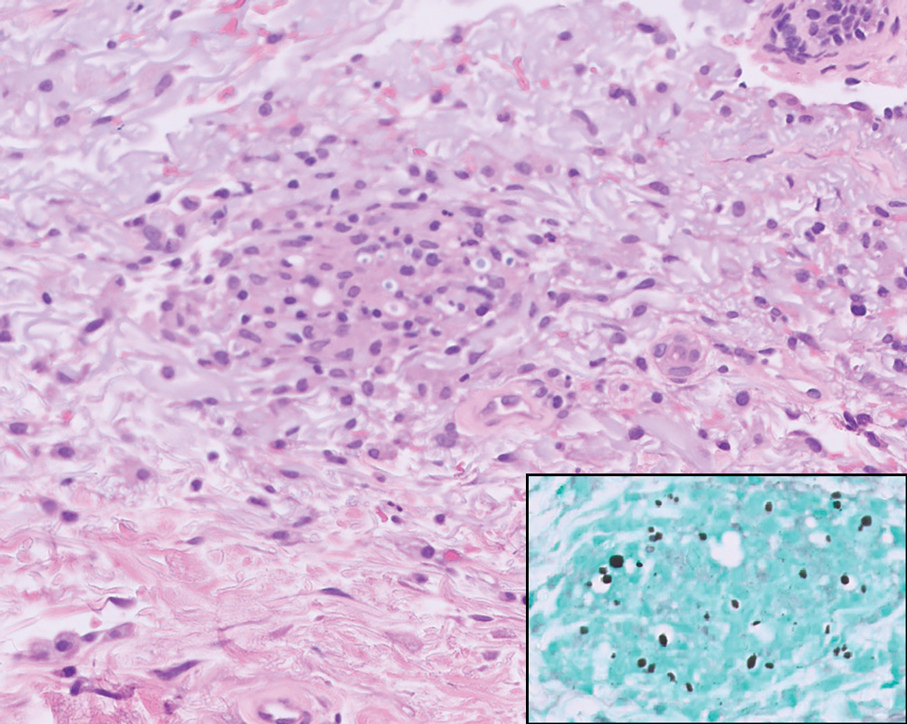

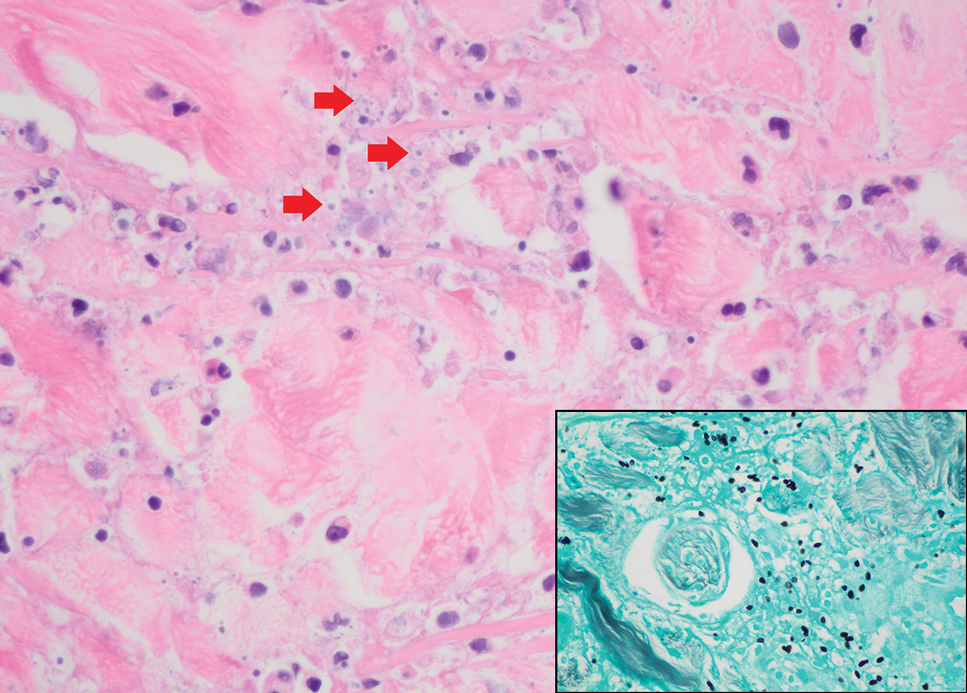

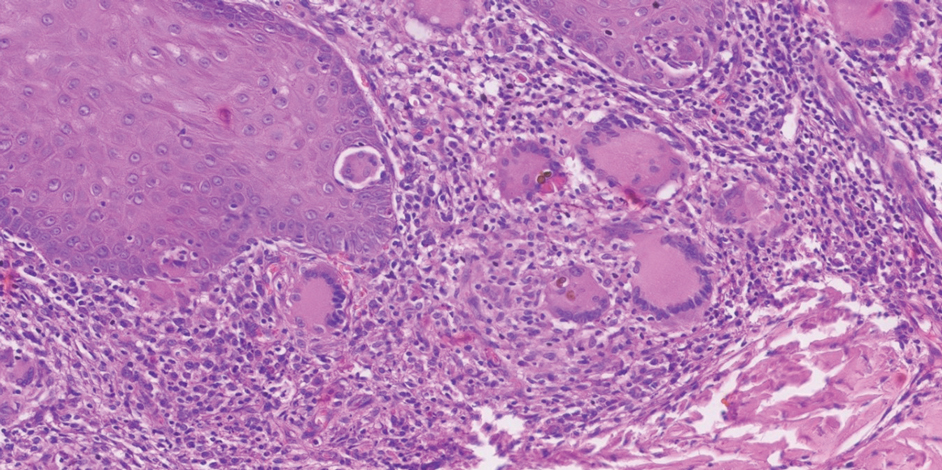

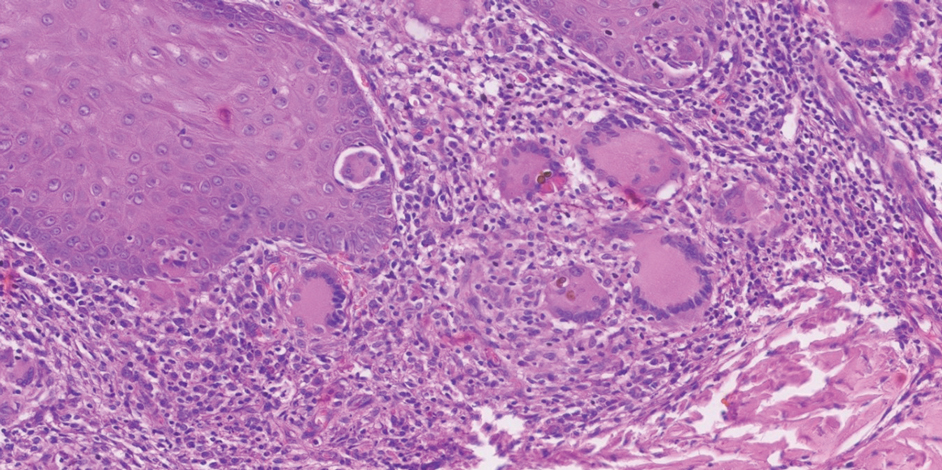

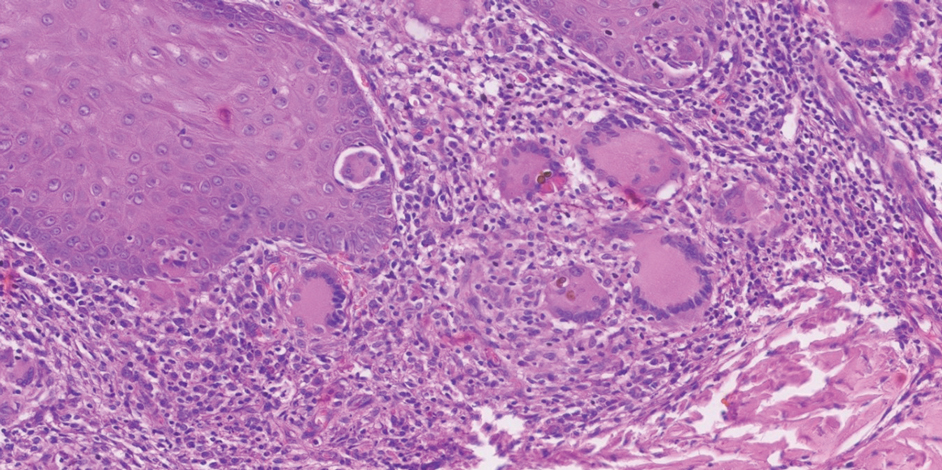

Leishmania species are parasites transmitted by bites of female sand flies, which belong to the genera Phlebotomus (Old World, Eastern Hemisphere) and Lutzomyia (New World, Western Hemisphere) genera.1 Leishmania species have a complex life cycle, propagating within human macrophages, ultimately leading to cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease manifestations.2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis manifests classically as scattered, painless, slow-healing ulcers.3 A biopsy taken from the edge of a cutaneous ulcer for hematoxylin and eosin processing is recommended for initial diagnosis, and subsequent polymerase chain reaction of the sample is required for speciation, which guides therapeutic options.4,5 Classic hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain findings include amastigotes lining the edges of parasitized histiocytes (Figure 2).

Systemic treatment options include sodium stibogluconate, amphotericin B, pentamidine, paromomycin, miltefosine, and azole antifungals.2,5 Geography often plays a critical role in selecting treatment options due to resistance rates of individual Leishmania species; for example, paromomycin compounds are more effective for cutaneous disease caused by Leishmania major than Leishmania tropica. Miltefosine is not effective for treating Leishmania braziliensis which can be acquired outside Guatemala, and higher doses of amphotericin B are recommended for visceral disease from East Africa.2,5 In patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L guyanensis, miltefosine remains a first-line option due to its oral formulation and long half-life within organisms, though there is a risk for teratogenicity.2 Amphotericin B remains the most effective treatment for visceral leishmaniasis and can be used off label to treat mucocutaneous disease or when cutaneous disease is refractory to other treatment options.3

Given the potential of L guyanensis to progress to mucocutaneous disease, monitoring for mucosal involvement should be performed at regular intervals for 6 months to 1 year.2 Treatment may be considered efficacious if no new skin lesions occur after 4 to 6 weeks of therapy; existing skin lesions should be re-epithelializing and reduced by 50% in size, with most cutaneous disease adequately controlled after 3 months of therapy.2

- Olivier M, Minguez-Menendez A, Fernandez-Prada C. Leishmania viannia guyanensis. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:1018-1019. doi:10.1016 /j.pt.2019.06.008

- Singh R, Kashif M, Srivastava P, et al. Recent advances in chemotherapeutics for leishmaniasis: importance of the cellular biochemistry of the parasite and its molecular interaction with the host. Pathogens. 2023;12:706. doi:10.3390/pathogens12050706

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63: 1539-1557. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw742

- Specimen Collection Guide for Laboratory Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticprocedures /other/leish.html

- Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:101-117. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.004

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results revealed amastigotes at the periphery of parasitized histiocytes, consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed Leishmania guyanensis species complex, which includes both L guyanensis and Leishmania panamensis. In this case of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis (Figure 1), our patient received a prolonged course of systemic therapy with oral miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. At the most recent follow-up appointment, she showed ongoing resolution of ulcerations, subcutaneous plaques, and lymphadenopathy on the trunk and face, but development of subcutaneous nodules continued on the arms and legs. At the next follow-up, physical examination revealed that the lesions slowly started to fade.

Leishmania species are parasites transmitted by bites of female sand flies, which belong to the genera Phlebotomus (Old World, Eastern Hemisphere) and Lutzomyia (New World, Western Hemisphere) genera.1 Leishmania species have a complex life cycle, propagating within human macrophages, ultimately leading to cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease manifestations.2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis manifests classically as scattered, painless, slow-healing ulcers.3 A biopsy taken from the edge of a cutaneous ulcer for hematoxylin and eosin processing is recommended for initial diagnosis, and subsequent polymerase chain reaction of the sample is required for speciation, which guides therapeutic options.4,5 Classic hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain findings include amastigotes lining the edges of parasitized histiocytes (Figure 2).

Systemic treatment options include sodium stibogluconate, amphotericin B, pentamidine, paromomycin, miltefosine, and azole antifungals.2,5 Geography often plays a critical role in selecting treatment options due to resistance rates of individual Leishmania species; for example, paromomycin compounds are more effective for cutaneous disease caused by Leishmania major than Leishmania tropica. Miltefosine is not effective for treating Leishmania braziliensis which can be acquired outside Guatemala, and higher doses of amphotericin B are recommended for visceral disease from East Africa.2,5 In patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L guyanensis, miltefosine remains a first-line option due to its oral formulation and long half-life within organisms, though there is a risk for teratogenicity.2 Amphotericin B remains the most effective treatment for visceral leishmaniasis and can be used off label to treat mucocutaneous disease or when cutaneous disease is refractory to other treatment options.3

Given the potential of L guyanensis to progress to mucocutaneous disease, monitoring for mucosal involvement should be performed at regular intervals for 6 months to 1 year.2 Treatment may be considered efficacious if no new skin lesions occur after 4 to 6 weeks of therapy; existing skin lesions should be re-epithelializing and reduced by 50% in size, with most cutaneous disease adequately controlled after 3 months of therapy.2

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results revealed amastigotes at the periphery of parasitized histiocytes, consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed Leishmania guyanensis species complex, which includes both L guyanensis and Leishmania panamensis. In this case of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis (Figure 1), our patient received a prolonged course of systemic therapy with oral miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. At the most recent follow-up appointment, she showed ongoing resolution of ulcerations, subcutaneous plaques, and lymphadenopathy on the trunk and face, but development of subcutaneous nodules continued on the arms and legs. At the next follow-up, physical examination revealed that the lesions slowly started to fade.

Leishmania species are parasites transmitted by bites of female sand flies, which belong to the genera Phlebotomus (Old World, Eastern Hemisphere) and Lutzomyia (New World, Western Hemisphere) genera.1 Leishmania species have a complex life cycle, propagating within human macrophages, ultimately leading to cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease manifestations.2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis manifests classically as scattered, painless, slow-healing ulcers.3 A biopsy taken from the edge of a cutaneous ulcer for hematoxylin and eosin processing is recommended for initial diagnosis, and subsequent polymerase chain reaction of the sample is required for speciation, which guides therapeutic options.4,5 Classic hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stain findings include amastigotes lining the edges of parasitized histiocytes (Figure 2).

Systemic treatment options include sodium stibogluconate, amphotericin B, pentamidine, paromomycin, miltefosine, and azole antifungals.2,5 Geography often plays a critical role in selecting treatment options due to resistance rates of individual Leishmania species; for example, paromomycin compounds are more effective for cutaneous disease caused by Leishmania major than Leishmania tropica. Miltefosine is not effective for treating Leishmania braziliensis which can be acquired outside Guatemala, and higher doses of amphotericin B are recommended for visceral disease from East Africa.2,5 In patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L guyanensis, miltefosine remains a first-line option due to its oral formulation and long half-life within organisms, though there is a risk for teratogenicity.2 Amphotericin B remains the most effective treatment for visceral leishmaniasis and can be used off label to treat mucocutaneous disease or when cutaneous disease is refractory to other treatment options.3

Given the potential of L guyanensis to progress to mucocutaneous disease, monitoring for mucosal involvement should be performed at regular intervals for 6 months to 1 year.2 Treatment may be considered efficacious if no new skin lesions occur after 4 to 6 weeks of therapy; existing skin lesions should be re-epithelializing and reduced by 50% in size, with most cutaneous disease adequately controlled after 3 months of therapy.2

- Olivier M, Minguez-Menendez A, Fernandez-Prada C. Leishmania viannia guyanensis. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:1018-1019. doi:10.1016 /j.pt.2019.06.008

- Singh R, Kashif M, Srivastava P, et al. Recent advances in chemotherapeutics for leishmaniasis: importance of the cellular biochemistry of the parasite and its molecular interaction with the host. Pathogens. 2023;12:706. doi:10.3390/pathogens12050706

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63: 1539-1557. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw742

- Specimen Collection Guide for Laboratory Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticprocedures /other/leish.html

- Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:101-117. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.004

- Olivier M, Minguez-Menendez A, Fernandez-Prada C. Leishmania viannia guyanensis. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:1018-1019. doi:10.1016 /j.pt.2019.06.008

- Singh R, Kashif M, Srivastava P, et al. Recent advances in chemotherapeutics for leishmaniasis: importance of the cellular biochemistry of the parasite and its molecular interaction with the host. Pathogens. 2023;12:706. doi:10.3390/pathogens12050706

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63: 1539-1557. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw742

- Specimen Collection Guide for Laboratory Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticprocedures /other/leish.html

- Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:101-117. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.004

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

Spreading Ulcerations and Lymphadenopathy in a Traveler Returning from Costa Rica

A 43-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with widespread scaly plaques and ulcerations of 2 months’ duration. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. The patient reported that the eruption began after returning from a vacation to Costa Rica, during which she spent time on the beach and white-water rafting. She noted that she had been exposed to numerous insects during her trip, and that her roommate, who had accompanied her, had similar exposure history and lesions. The plaques were refractory to multiple oral antibiotics previously prescribed by primary care. Physical examination revealed submental lymphadenopathy and painless ulcerations with indurated borders without purulent drainage alongside scattered scaly papules and plaques on the face, neck, arms, and legs. A biopsy was taken from an ulceration edge on the left thigh.

Military-Backed French Biotech Brings Ricin Antidote

Military-Backed French Biotech Brings Ricin Antidote

France has authorized Ricimed, the first antibody-based treatment specifically indicated for acute ricin intoxication, providing clinicians with a targeted option beyond supportive care for exposure to one of the most lethal naturally occurring toxins.

Fabentech is a French biopharmaceutical company specializing in medical countermeasures against biological threats and infectious diseases.

The polyclonal antibody technology used in the development of Ricimed has received marketing authorization in France as a treatment for ricin poisoning. Ricin is a highly toxic natural substance that can cause death within hours to a few days of exposure.

Supported by the Ministry of Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs (Directorate General of Armaments [DGA] and Armed Forces Health Service) in France, Ricimed is the first approved antidote for ricin poisoning, a condition for which treatment was previously limited to supportive measures alone.

Historical Incident

One incident, in particular, remains etched in espionage history. On September 7, 1978 in London during the Cold War, Bulgarian dissident writer Georgi Markov, living in exile, was struck by the umbrella of a passer-by while waiting at a bus stop. He felt a slight sting. Four days later, he died in the hospital due to a sudden and unexplained illness. An autopsy revealed that he had been poisoned by a tiny metal pellet implanted at the tip of an umbrella containing ricin, a lethal toxin. The legend of the “Bulgarian umbrella,” later invoked in other assassination attempts, was born.

Since then, although Markov remains the only known individual to have been killed by ricin poisoning, this theoretically extremely toxic substance, which can be manufactured relatively easily from castor beans, a widely available plant, has continued to fascinate authors of thrillers and spy novels.

Numerous works of fiction depict characters who succumb to ricin poisoning. The toxin is notably portrayed as a favored weapon of the main character in the hit television series Breaking Bad.

However, ricin is not confined to the realm of science fiction. For several years, authorities in various countries have feared that extremist groups could carry out attacks using ricin. The threat has been taken particularly seriously since 2018, when a clandestine ricin laboratory operated by members of the Islamic State was dismantled in Germany. Since then, several similar attack plots have been thwarted.

This context triggered a race among major powers to develop an effective antidote as quickly as possible. In this effort, Fabentech has risen to a challenge.

“Having demonstrated its ability to target and then neutralize ricin before it causes irreparable damage, Ricimed is a treatment that works based on polyclonal antibodies and compensates for the absence of a vaccine or specific treatment,” Fabentech said in a press release.

The polyclonal antibody technology used by Fabentech offers potential for the development of antidotes against bioterrorist attacks and for the treatment of many infectious diseases.

Ricimed contributed to the deployment of a European health shield against intentional biological threats in France.

Military Backing

Speaking to Le Figaro, France’s oldest national newspaper, Fabentech CEO Sébastien Iva explained that ricin disrupts the body by halting cell function, while noting several other drug candidates in development at the firm.

Typically, the lungs sustain fatal damage. Our treatment interrupts this toxic process. In animals administered the antidote, we observed pulmonary function recovery, allowing survival.

Given that the possibility of terrorist attacks using ricin is considered a national security issue, Fabentech benefited from the support by the Ministry of the Armed Forces and the DGA and lasted nearly a decade of research and development work.

The granting of marketing authorisation was also supported by the French Armed Forces and welcomed by the French Minister of the Armed Forces, Catherine Vautrin, who previously served as France’s Minister of Labour, Health, and Solidarity.

“Supporting the development of companies in France capable of manufacturing antidotes against certain biological agents helps guarantee the operational superiority of our armed forces. Developing and producing such drugs when they do not yet exist on the market is also serving the nation and the public interest,” she said.

Although the threat posed by ricin remains hypothetical, Fabentech reports a strong interest from potential clients, with many countries seeking protection against possible bioterrorist attacks.

The DGA had already placed an order for several doses of Ricimed for deployment in France. For optimal effectiveness, the antidote must be administered within 6 hours of poisoning. Iva confirmed that multiple countries had already expressed interest in acquiring the antidote.

This story was translated from JIM, part of the Medscape Professional Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

France has authorized Ricimed, the first antibody-based treatment specifically indicated for acute ricin intoxication, providing clinicians with a targeted option beyond supportive care for exposure to one of the most lethal naturally occurring toxins.

Fabentech is a French biopharmaceutical company specializing in medical countermeasures against biological threats and infectious diseases.

The polyclonal antibody technology used in the development of Ricimed has received marketing authorization in France as a treatment for ricin poisoning. Ricin is a highly toxic natural substance that can cause death within hours to a few days of exposure.

Supported by the Ministry of Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs (Directorate General of Armaments [DGA] and Armed Forces Health Service) in France, Ricimed is the first approved antidote for ricin poisoning, a condition for which treatment was previously limited to supportive measures alone.

Historical Incident

One incident, in particular, remains etched in espionage history. On September 7, 1978 in London during the Cold War, Bulgarian dissident writer Georgi Markov, living in exile, was struck by the umbrella of a passer-by while waiting at a bus stop. He felt a slight sting. Four days later, he died in the hospital due to a sudden and unexplained illness. An autopsy revealed that he had been poisoned by a tiny metal pellet implanted at the tip of an umbrella containing ricin, a lethal toxin. The legend of the “Bulgarian umbrella,” later invoked in other assassination attempts, was born.

Since then, although Markov remains the only known individual to have been killed by ricin poisoning, this theoretically extremely toxic substance, which can be manufactured relatively easily from castor beans, a widely available plant, has continued to fascinate authors of thrillers and spy novels.

Numerous works of fiction depict characters who succumb to ricin poisoning. The toxin is notably portrayed as a favored weapon of the main character in the hit television series Breaking Bad.

However, ricin is not confined to the realm of science fiction. For several years, authorities in various countries have feared that extremist groups could carry out attacks using ricin. The threat has been taken particularly seriously since 2018, when a clandestine ricin laboratory operated by members of the Islamic State was dismantled in Germany. Since then, several similar attack plots have been thwarted.

This context triggered a race among major powers to develop an effective antidote as quickly as possible. In this effort, Fabentech has risen to a challenge.

“Having demonstrated its ability to target and then neutralize ricin before it causes irreparable damage, Ricimed is a treatment that works based on polyclonal antibodies and compensates for the absence of a vaccine or specific treatment,” Fabentech said in a press release.

The polyclonal antibody technology used by Fabentech offers potential for the development of antidotes against bioterrorist attacks and for the treatment of many infectious diseases.

Ricimed contributed to the deployment of a European health shield against intentional biological threats in France.

Military Backing

Speaking to Le Figaro, France’s oldest national newspaper, Fabentech CEO Sébastien Iva explained that ricin disrupts the body by halting cell function, while noting several other drug candidates in development at the firm.

Typically, the lungs sustain fatal damage. Our treatment interrupts this toxic process. In animals administered the antidote, we observed pulmonary function recovery, allowing survival.

Given that the possibility of terrorist attacks using ricin is considered a national security issue, Fabentech benefited from the support by the Ministry of the Armed Forces and the DGA and lasted nearly a decade of research and development work.

The granting of marketing authorisation was also supported by the French Armed Forces and welcomed by the French Minister of the Armed Forces, Catherine Vautrin, who previously served as France’s Minister of Labour, Health, and Solidarity.

“Supporting the development of companies in France capable of manufacturing antidotes against certain biological agents helps guarantee the operational superiority of our armed forces. Developing and producing such drugs when they do not yet exist on the market is also serving the nation and the public interest,” she said.

Although the threat posed by ricin remains hypothetical, Fabentech reports a strong interest from potential clients, with many countries seeking protection against possible bioterrorist attacks.

The DGA had already placed an order for several doses of Ricimed for deployment in France. For optimal effectiveness, the antidote must be administered within 6 hours of poisoning. Iva confirmed that multiple countries had already expressed interest in acquiring the antidote.

This story was translated from JIM, part of the Medscape Professional Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

France has authorized Ricimed, the first antibody-based treatment specifically indicated for acute ricin intoxication, providing clinicians with a targeted option beyond supportive care for exposure to one of the most lethal naturally occurring toxins.

Fabentech is a French biopharmaceutical company specializing in medical countermeasures against biological threats and infectious diseases.

The polyclonal antibody technology used in the development of Ricimed has received marketing authorization in France as a treatment for ricin poisoning. Ricin is a highly toxic natural substance that can cause death within hours to a few days of exposure.

Supported by the Ministry of Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs (Directorate General of Armaments [DGA] and Armed Forces Health Service) in France, Ricimed is the first approved antidote for ricin poisoning, a condition for which treatment was previously limited to supportive measures alone.

Historical Incident

One incident, in particular, remains etched in espionage history. On September 7, 1978 in London during the Cold War, Bulgarian dissident writer Georgi Markov, living in exile, was struck by the umbrella of a passer-by while waiting at a bus stop. He felt a slight sting. Four days later, he died in the hospital due to a sudden and unexplained illness. An autopsy revealed that he had been poisoned by a tiny metal pellet implanted at the tip of an umbrella containing ricin, a lethal toxin. The legend of the “Bulgarian umbrella,” later invoked in other assassination attempts, was born.

Since then, although Markov remains the only known individual to have been killed by ricin poisoning, this theoretically extremely toxic substance, which can be manufactured relatively easily from castor beans, a widely available plant, has continued to fascinate authors of thrillers and spy novels.

Numerous works of fiction depict characters who succumb to ricin poisoning. The toxin is notably portrayed as a favored weapon of the main character in the hit television series Breaking Bad.

However, ricin is not confined to the realm of science fiction. For several years, authorities in various countries have feared that extremist groups could carry out attacks using ricin. The threat has been taken particularly seriously since 2018, when a clandestine ricin laboratory operated by members of the Islamic State was dismantled in Germany. Since then, several similar attack plots have been thwarted.

This context triggered a race among major powers to develop an effective antidote as quickly as possible. In this effort, Fabentech has risen to a challenge.

“Having demonstrated its ability to target and then neutralize ricin before it causes irreparable damage, Ricimed is a treatment that works based on polyclonal antibodies and compensates for the absence of a vaccine or specific treatment,” Fabentech said in a press release.

The polyclonal antibody technology used by Fabentech offers potential for the development of antidotes against bioterrorist attacks and for the treatment of many infectious diseases.

Ricimed contributed to the deployment of a European health shield against intentional biological threats in France.

Military Backing

Speaking to Le Figaro, France’s oldest national newspaper, Fabentech CEO Sébastien Iva explained that ricin disrupts the body by halting cell function, while noting several other drug candidates in development at the firm.

Typically, the lungs sustain fatal damage. Our treatment interrupts this toxic process. In animals administered the antidote, we observed pulmonary function recovery, allowing survival.

Given that the possibility of terrorist attacks using ricin is considered a national security issue, Fabentech benefited from the support by the Ministry of the Armed Forces and the DGA and lasted nearly a decade of research and development work.

The granting of marketing authorisation was also supported by the French Armed Forces and welcomed by the French Minister of the Armed Forces, Catherine Vautrin, who previously served as France’s Minister of Labour, Health, and Solidarity.

“Supporting the development of companies in France capable of manufacturing antidotes against certain biological agents helps guarantee the operational superiority of our armed forces. Developing and producing such drugs when they do not yet exist on the market is also serving the nation and the public interest,” she said.

Although the threat posed by ricin remains hypothetical, Fabentech reports a strong interest from potential clients, with many countries seeking protection against possible bioterrorist attacks.

The DGA had already placed an order for several doses of Ricimed for deployment in France. For optimal effectiveness, the antidote must be administered within 6 hours of poisoning. Iva confirmed that multiple countries had already expressed interest in acquiring the antidote.

This story was translated from JIM, part of the Medscape Professional Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Military-Backed French Biotech Brings Ricin Antidote

Military-Backed French Biotech Brings Ricin Antidote

Retrospective Analysis of Prevalence and Treatment Patterns of Skin and Nail Candidiasis From US Health Insurance Claims Data

Retrospective Analysis of Prevalence and Treatment Patterns of Skin and Nail Candidiasis From US Health Insurance Claims Data

Candida is a common commensal organism of human skin and mucous membranes. Candidiasis of the skin and nails is caused by overgrowth of Candida species due to excess skin moisture, skin barrier disruption, or immunosuppression. Candidiasis of the skin manifests as red, moist, itchy patches that develop particularly in skin folds. Nail involvement is associated with onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and subungual debris.1 Data on the prevalence of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States are scarce. In this study, we evaluated the prevalence, characteristics, and treatment practices of candidiasis of the skin and nails using data from 2 large US health insurance claims databases.

Methods

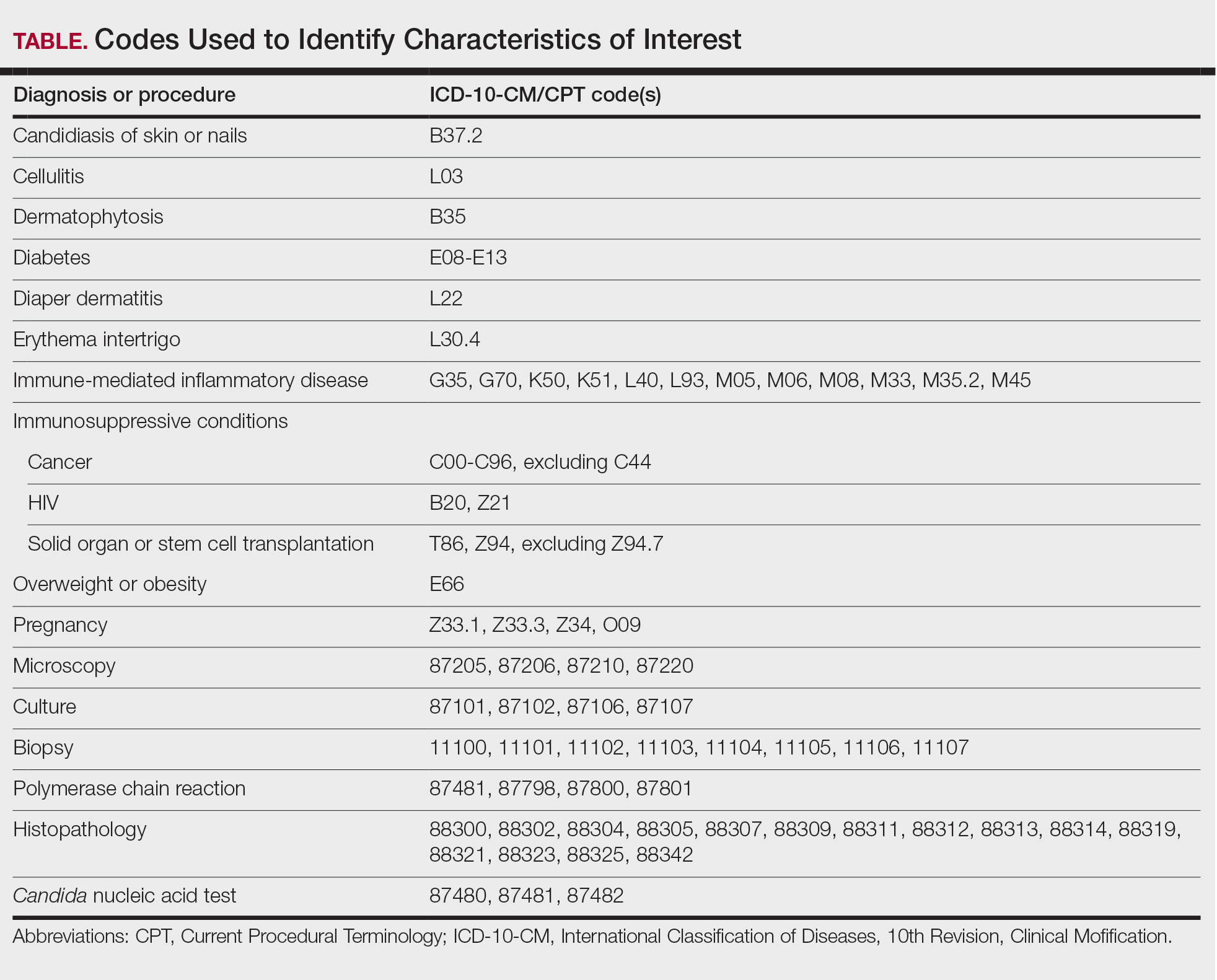

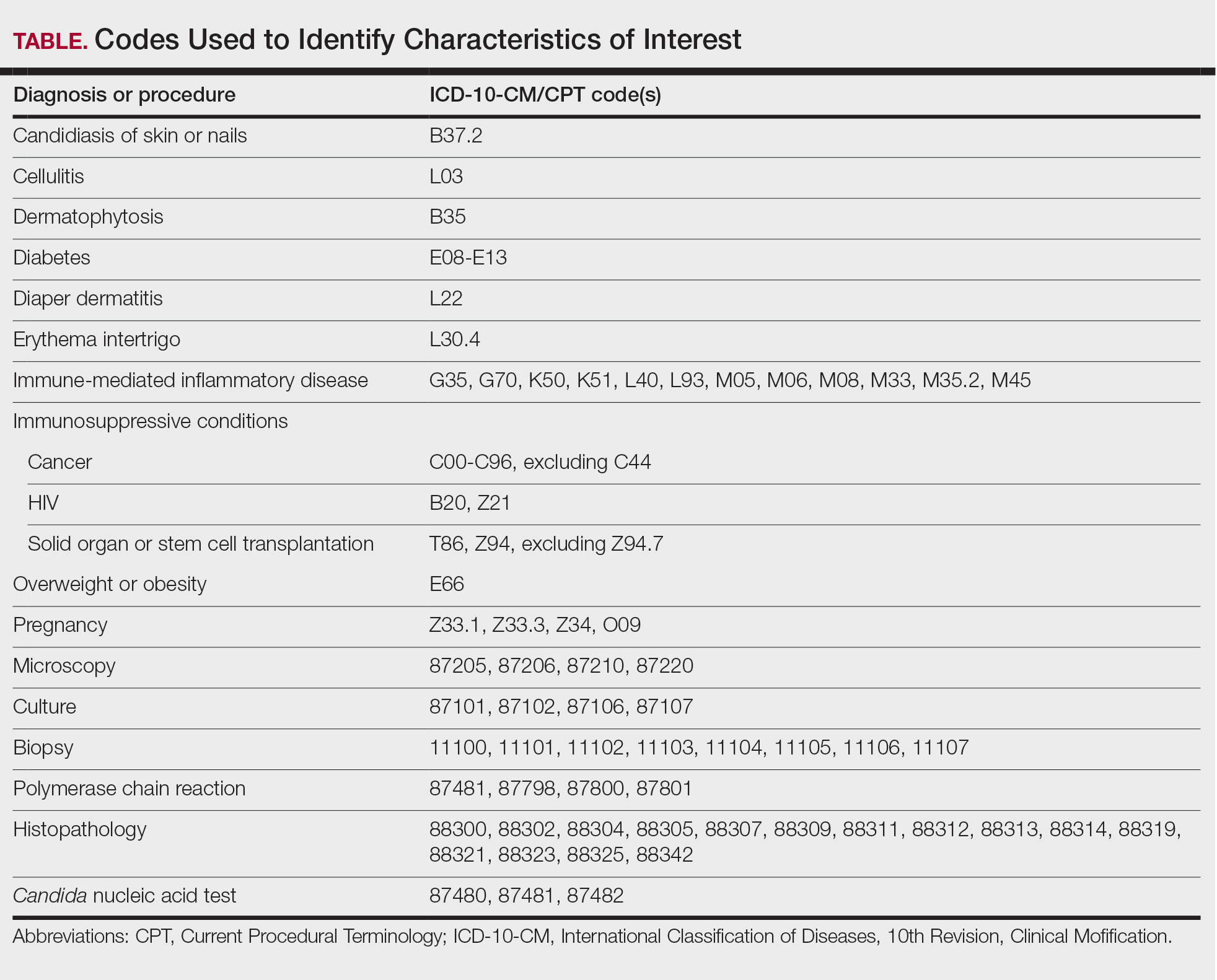

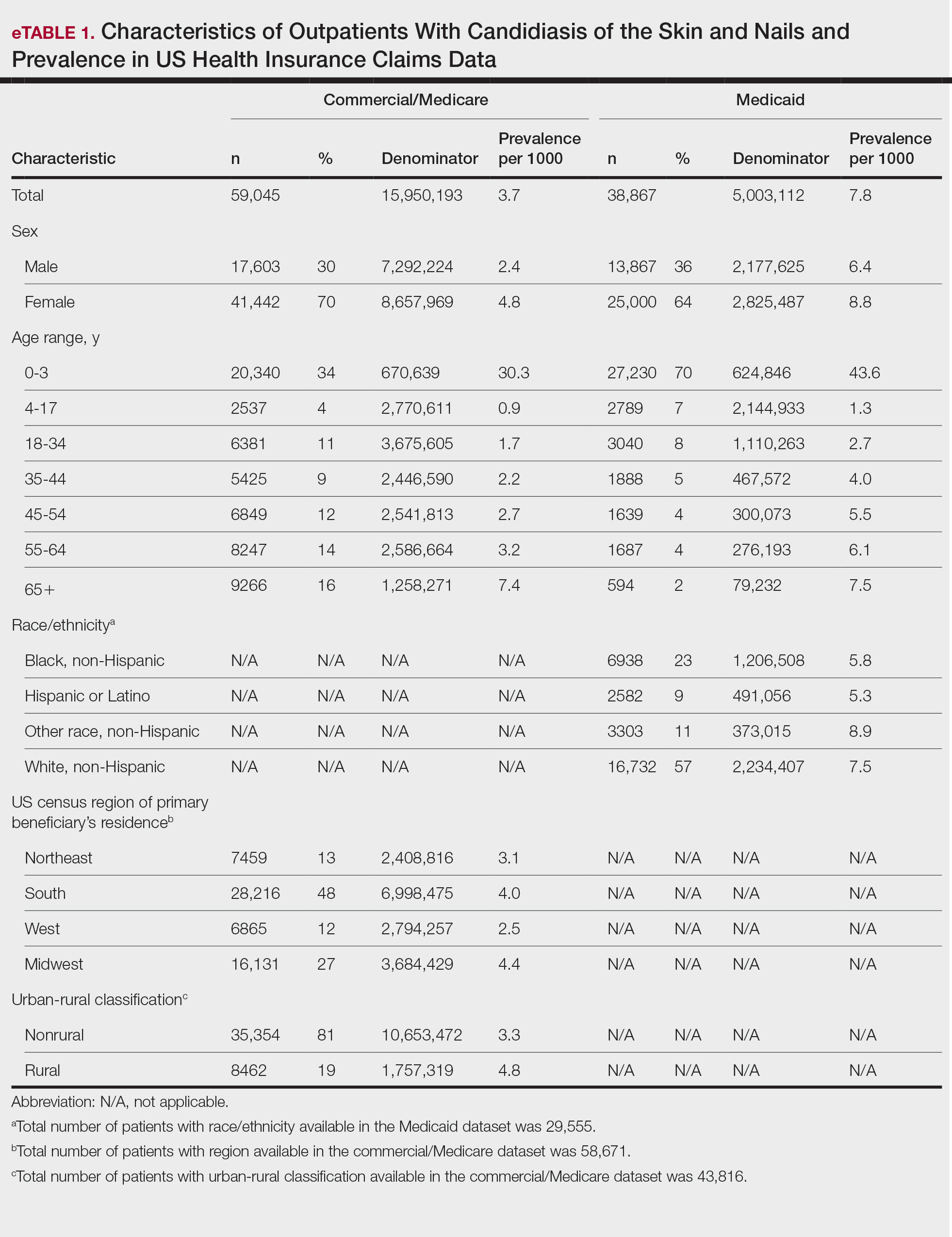

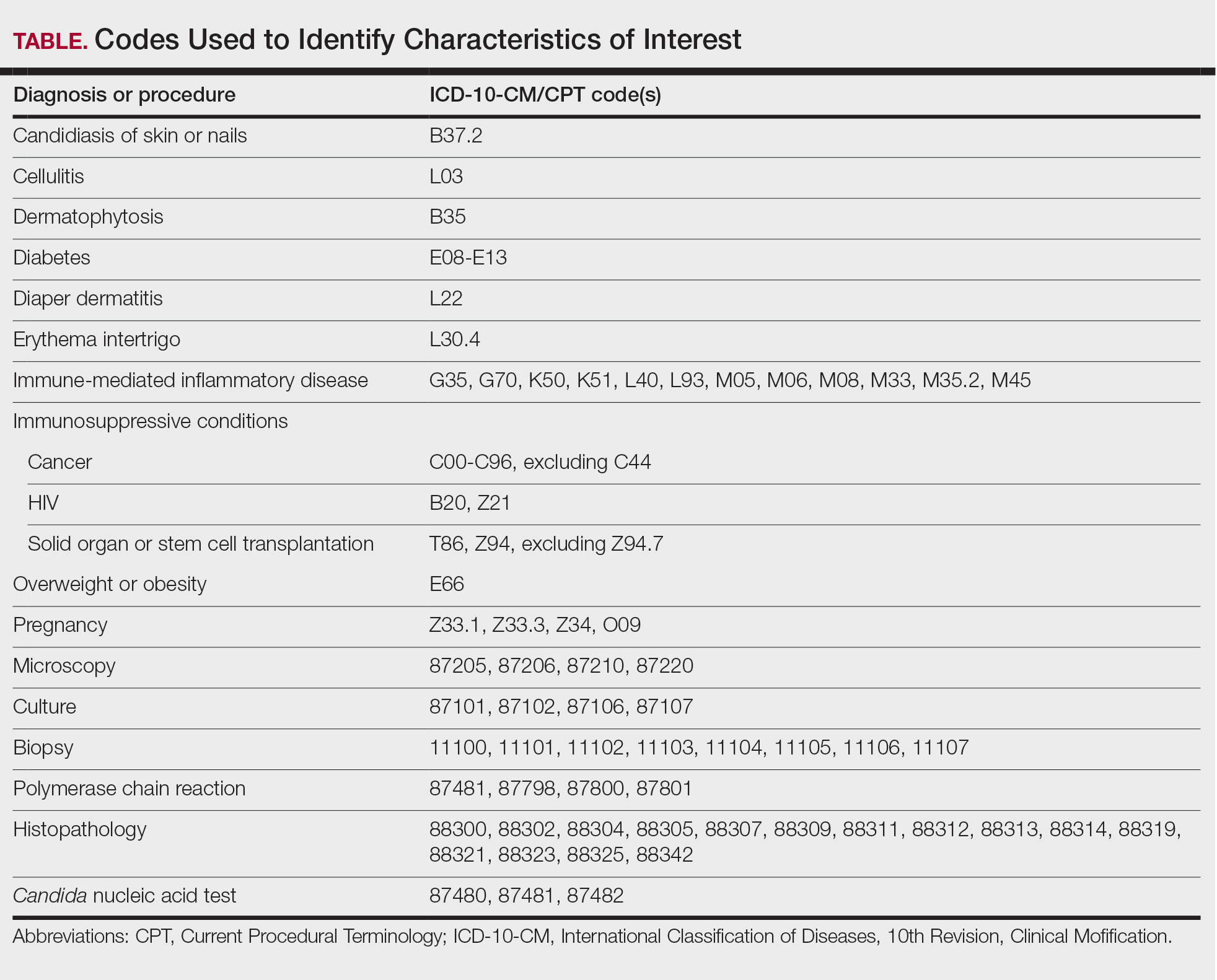

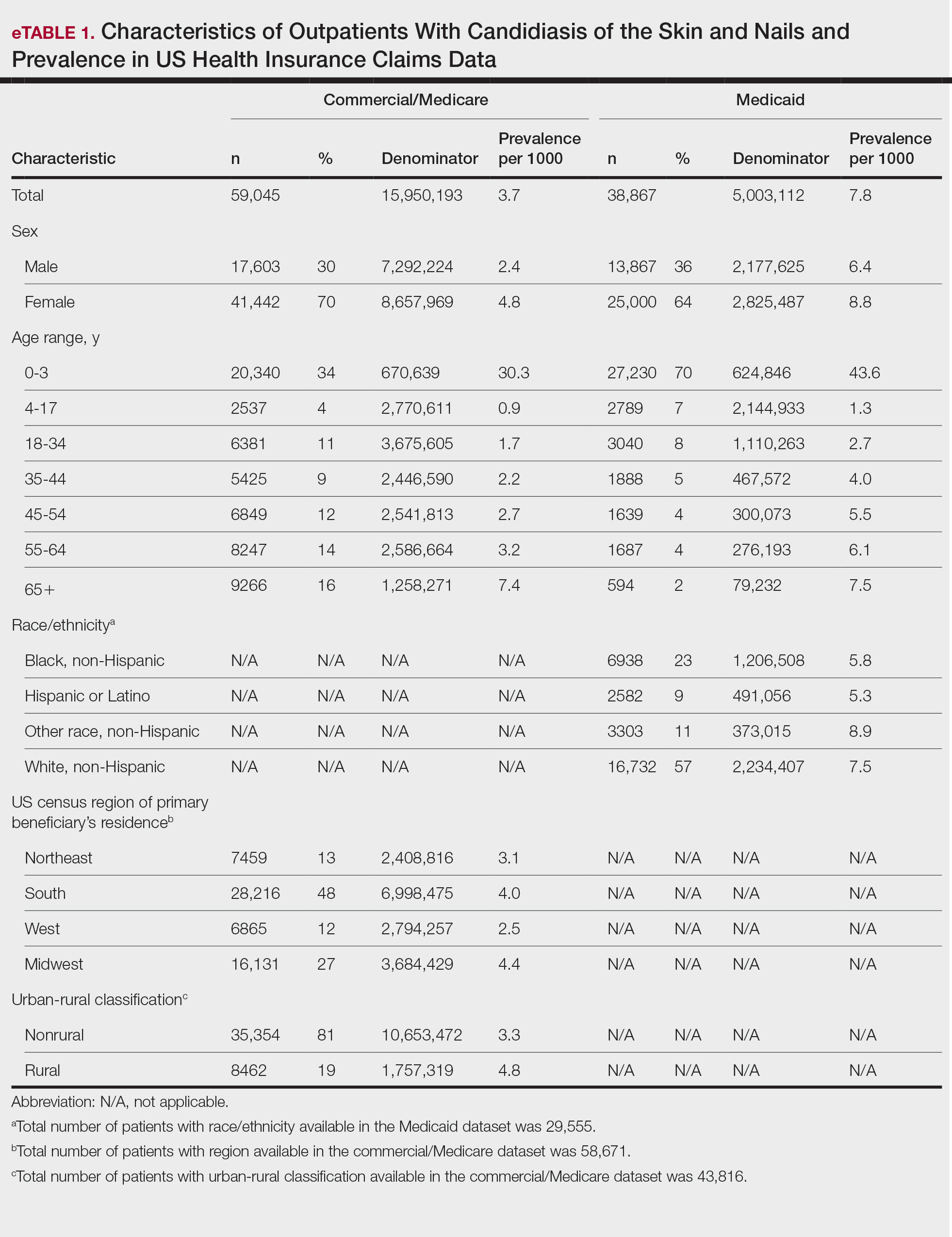

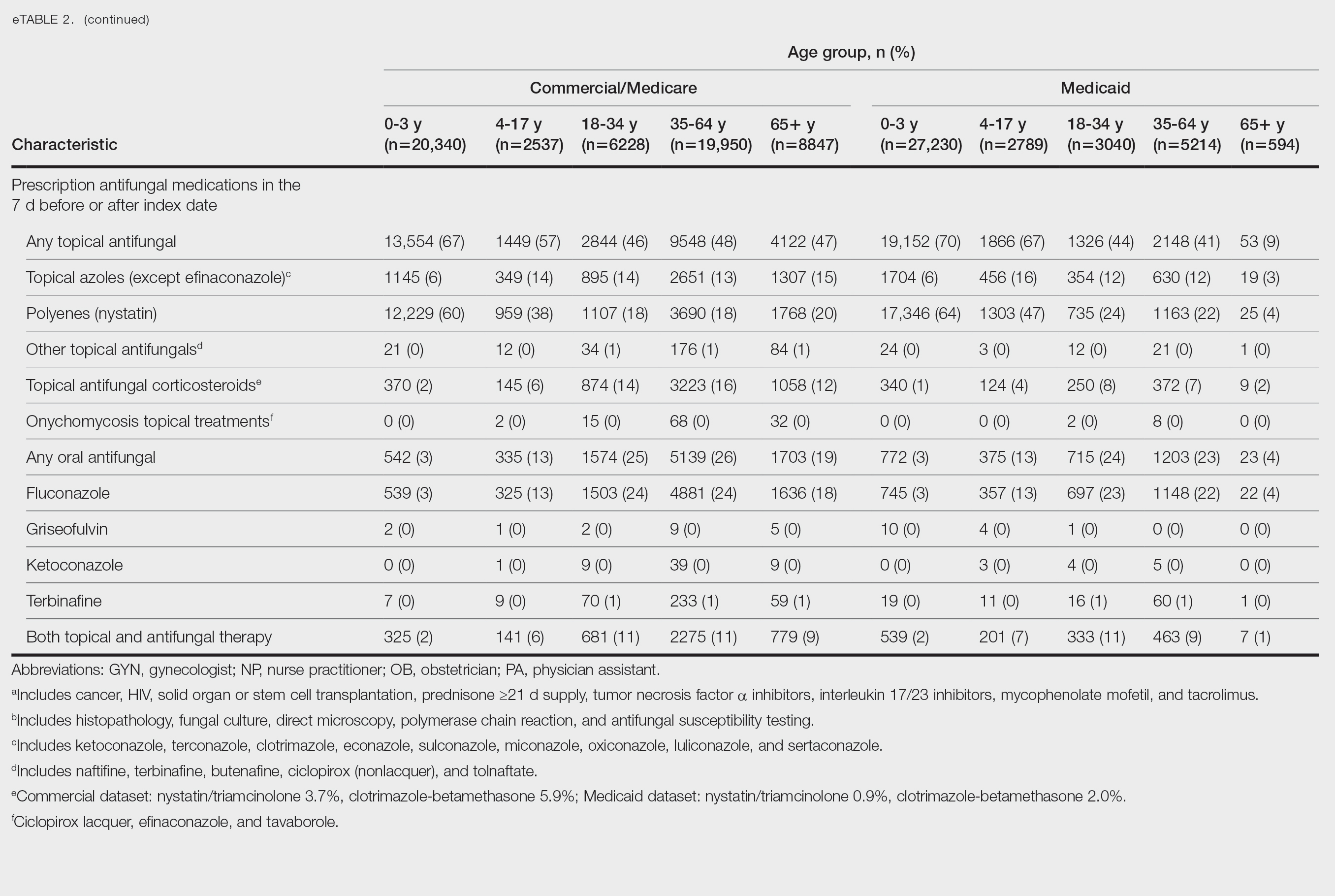

We used the 2023 Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases (https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases) to identify outpatients with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code B37.2 for candidiasis of the skin and nails. The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases include health insurance claims data submitted by large employers and health plans for more than 19 million patients throughout the United States, and the Multi-State Medicaid database includes similar data from more than 5 million patients across several geographically dispersed states. The index date for each patient corresponded with their first qualifying diagnosis of skin and nail candidiasis during January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. Inclusion in the study required continuous insurance enrollment from 30 days prior to 7 days after the index date, resulting in exclusion of 7% of commercial/Medicare patients and 8% of Medicaid patients. Prevalence per 1000 outpatients was calculated, with stratification by demographic characteristics.

We examined selected diagnoses made on or within 30 days before the index date, diagnostic testing performed within the 7 days before or after the index date after using specific Current Procedural Terminology codes, and outpatient antifungal and combination antifungal-corticosteroid prescriptions made within 7 days before or after the index date (Table). Race/ethnicity data are unavailable in the commercial/Medicare database, and geographic data are unavailable in the Medicaid database.

Results

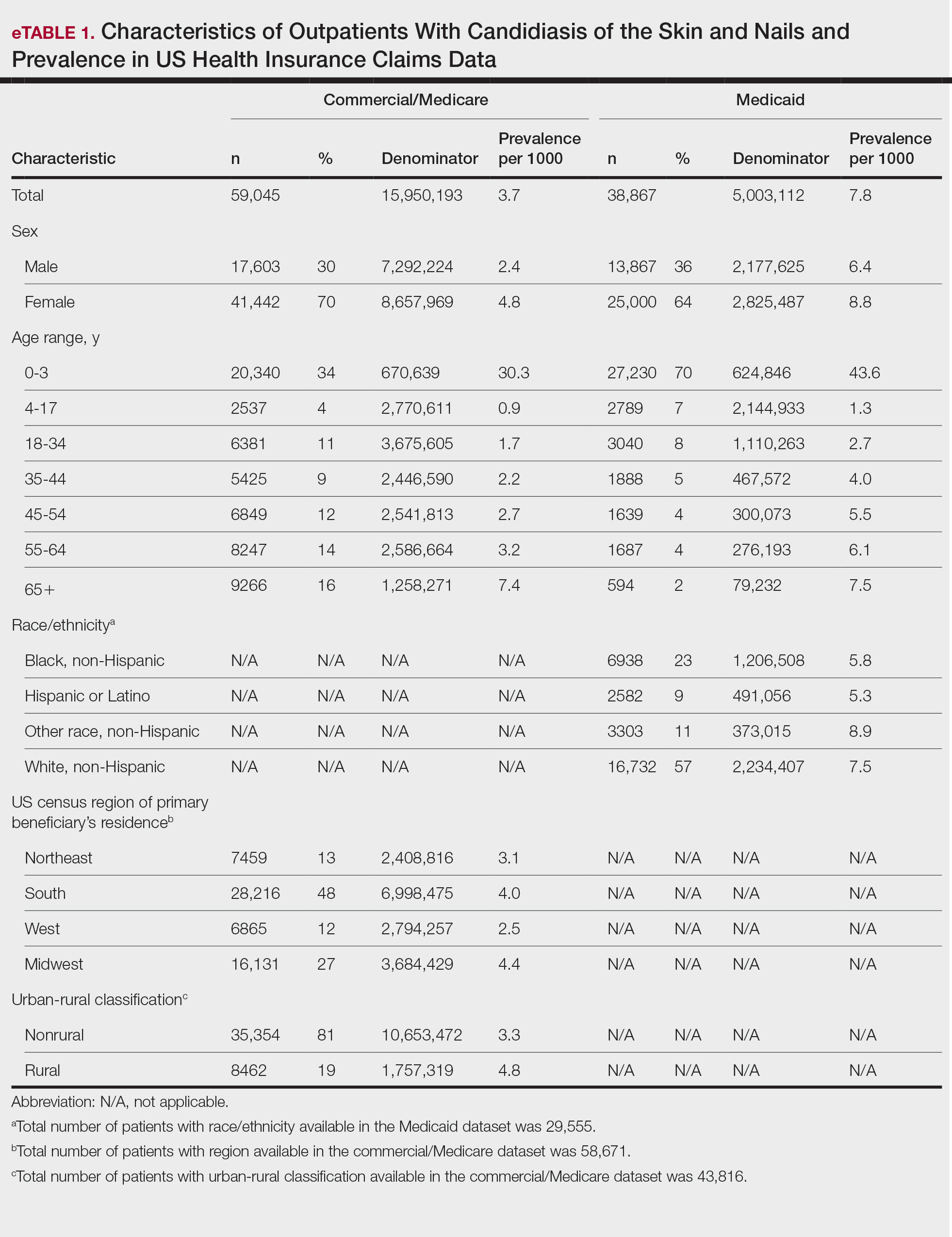

The prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis was 3.7 per 1000 commercial/Medicare outpatients and 7.8 per 1000 Medicaid outpatients (eTable 1). Prevalence was highest among patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 30.3 per 1000; Medicaid, 43.6 per 1000), followed by patients 65 years or older (commercial/Medicare, 7.4 per 1000; Medicaid, 7.5 per 1000). Prevalence was higher among females compared with males (commercial/Medicare, 4.8 vs 2.4 per 1000, respectively; Medicaid, 8.8 vs 6.4 per 1000, respectively). Among Medicaid patients, prevalence was highest among those of other race, non-Hispanic (8.9 per 1000) and White non-Hispanic patients (7.5 per 1000). In the commercial/Medicare dataset, prevalence was highest in patients residing in the Midwest (4.4 per 1000) and the South (4.0 per 1000).

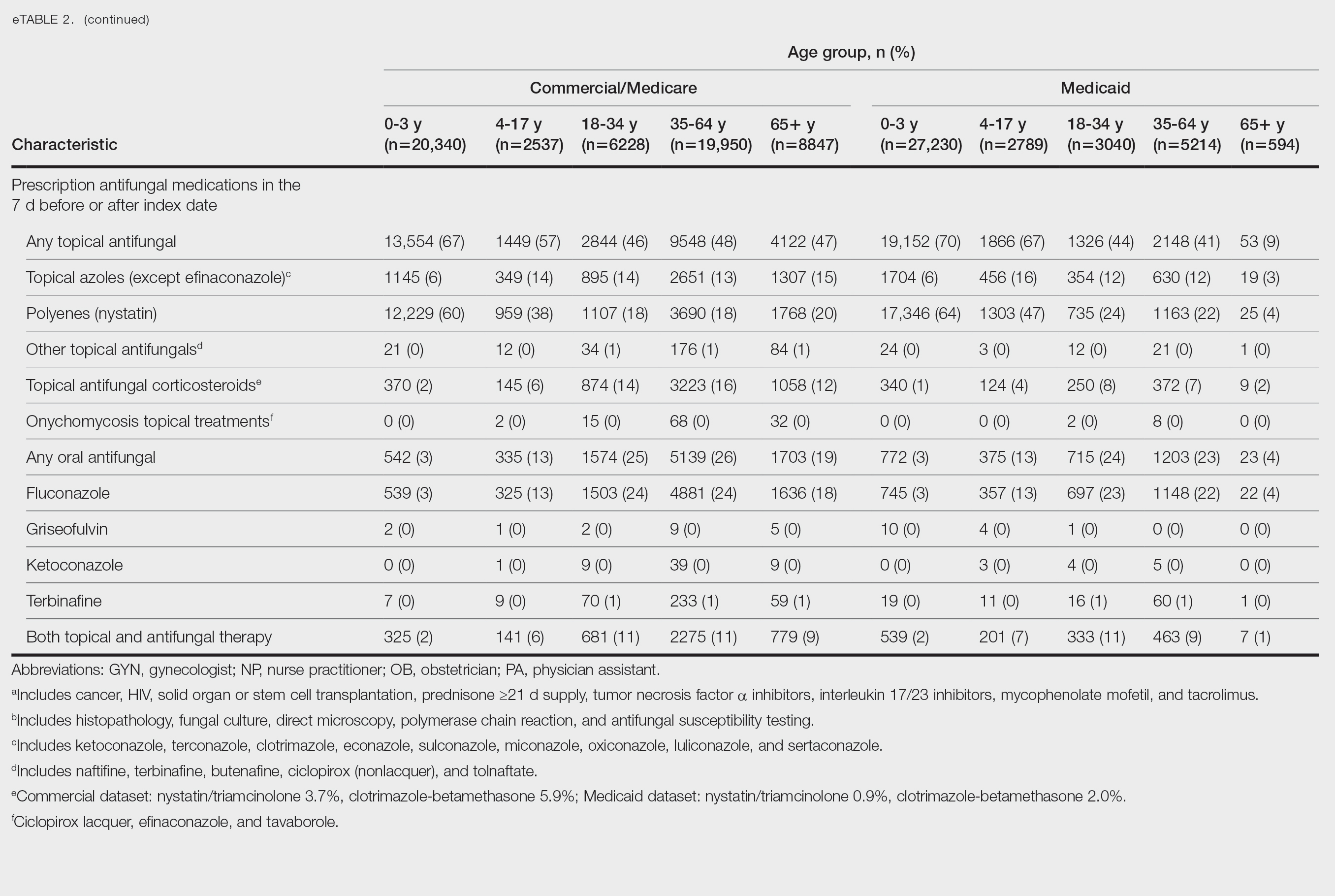

Diaper dermatitis was listed as a concurrent diagnosis among 51% of patients aged 0 to 3 years in both datasets (eTable 2). Diabetes (commercial/Medicare, 32%; Medicaid, 36%) and immunosuppressive conditions (commercial/Medicare, 10%; Medicaid, 7%) were most frequent among patients aged 65 years or older. Obesity was most commonly listed as a concurrent diagnosis among patients aged 35 to 64 years (commercial/Medicare, 17%; Medicaid, 23%).

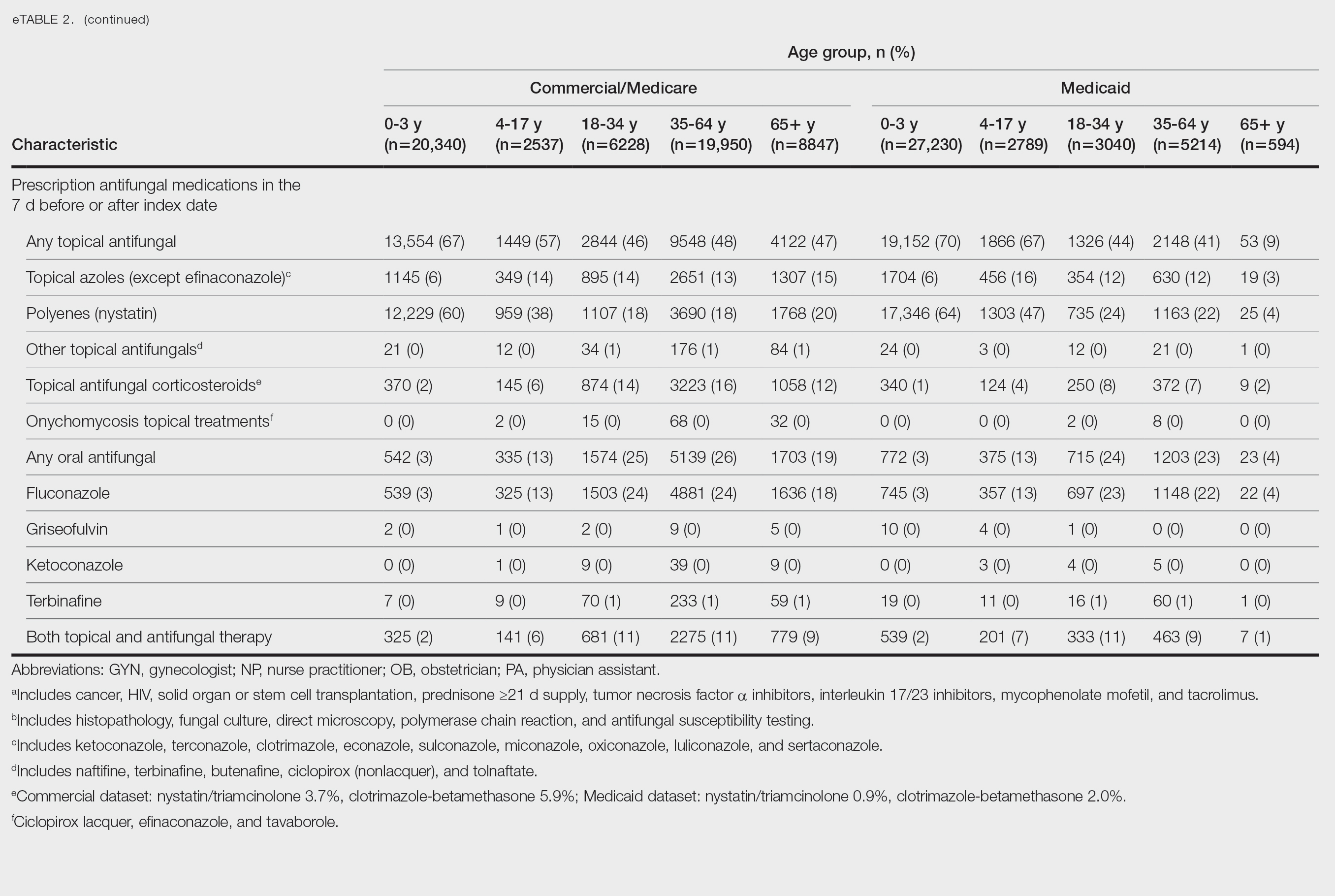

Patients aged 18 to 34 years had the highest rates of diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date (commercial/Medicare, 9%; Medicaid, 10%). Topical antifungal medications (primarily nystatin) were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 67%; Medicaid, 70%). Topical combination antifungal-corticosteroid medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (16%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (8%). Topical onychomycosis treatments were prescribed for fewer than 1% of patients in both datasets. Oral antifungal medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (26%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (24%). Fewer than 11% of patients across all age groups in both datasets were prescribed both topical and oral antifungal medications.

Comment

Our analysis provides preliminary insight into the prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis in the United States based on health insurance claims data. Higher prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis among patients with Medicaid compared with those with commercial/Medicare health insurance is consistent with previous studies showing increased rates of other superficial fungal infections (eg, dermatophytosis) among patients of lower socioeconomic status.2 This finding could reflect differences in underlying health status or reduced access to health care, which could delay treatment or follow-up care and potentially lead to prolonged exposure to conditions favoring the development of candidiasis.

In both the commercial/Medicare health insurance and Medicaid datasets, prevalence of diagnosis codes for candidiasis of the skin and nails was highest among infants and toddlers. Diaper dermatitis also was observed in more than half of patients aged 0 to 3 years; this is a well-established risk factor for cutaneous candidiasis, as immature skin barrier function and prolonged exposure to moisture and occlusion facilitate fungal overgrowth.3 In adults, diabetes and obesity were among the most frequent comorbidities observed; both conditions are recognized risk factors for superficial candidiasis due to their impact on immune function and skin integrity.4

In both study cohorts, diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date was infrequent (≤10%), consistent with most cases being diagnosed clinically.5 Topical antifungals, especially nystatin, were most frequently prescribed for young children, while oral antifungals were more frequently prescribed for adults; nystatin is one of the most well-studied topical treatments for cutaneous candidiasis, and oral fluconazole is the primary systemic treatment for cutaneous candidiasis.1 In our study, the ICD-10-CM code B37.2 appeared to be used primarily for diagnosis of skin rather than nail infections based on the low proportions of patients who received treatment that was onychomycosis specific.

Our study was limited by potential misclassification inherent to data based on diagnosis codes; incomplete capture of underlying conditions given the short continuous enrollment criteria; and lack of information about affected body site(s) and laboratory results, including data identifying the Candida species. A previous study found that Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans were the most common species involved in candidiasis of the skin and nails and that one-third of isolates exhibited low sensitivity to commonly used antifungals.6 For nails, Candida species are sometimes contaminants rather than pathogens.

Conclusion

Our findings provide a baseline understanding of the epidemiology of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States. The growing threat of antifungal resistance, particularly among non-albicans Candida species, underscores the need for appropriate use of antifungals.7 Future epidemiologic studies about laboratory-confirmed candidiasis of the skin and nails to understand causative species and drug resistance would be useful, as would further investigation into disparities.

- Taudorf EH, Jemec GBE, Hay RJ, et al. Cutaneous candidiasis—an evidence-based review of topical and systemic treatments to inform clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1863-1873. doi:10.1111/jdv.15782

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102325. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102325

- Benitez Ojeda AB, Mendez MD. Diaper dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559067/

- Shahabudin S, Azmi NS, Lani MN, et al. Candida albicans skin infection in diabetic patients: an updated review of pathogenesis and management. Mycoses. 2024;67:E13753. doi:10.1111/myc.13753

- Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Kinney BS. Intertrigo and secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:569-573.

- Ranđelovic M, Ignjatovic A, Đorđevic M, et al. Superficial candidiasis: cluster analysis of species distribution and their antifungal susceptibility in vitro. J Fungi (Basel). 2025;11:338.

- Hay R. Therapy of skin, hair and nail fungal infections. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:99. doi:10.3390/jof4030099

Candida is a common commensal organism of human skin and mucous membranes. Candidiasis of the skin and nails is caused by overgrowth of Candida species due to excess skin moisture, skin barrier disruption, or immunosuppression. Candidiasis of the skin manifests as red, moist, itchy patches that develop particularly in skin folds. Nail involvement is associated with onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and subungual debris.1 Data on the prevalence of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States are scarce. In this study, we evaluated the prevalence, characteristics, and treatment practices of candidiasis of the skin and nails using data from 2 large US health insurance claims databases.

Methods

We used the 2023 Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases (https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases) to identify outpatients with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code B37.2 for candidiasis of the skin and nails. The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases include health insurance claims data submitted by large employers and health plans for more than 19 million patients throughout the United States, and the Multi-State Medicaid database includes similar data from more than 5 million patients across several geographically dispersed states. The index date for each patient corresponded with their first qualifying diagnosis of skin and nail candidiasis during January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. Inclusion in the study required continuous insurance enrollment from 30 days prior to 7 days after the index date, resulting in exclusion of 7% of commercial/Medicare patients and 8% of Medicaid patients. Prevalence per 1000 outpatients was calculated, with stratification by demographic characteristics.

We examined selected diagnoses made on or within 30 days before the index date, diagnostic testing performed within the 7 days before or after the index date after using specific Current Procedural Terminology codes, and outpatient antifungal and combination antifungal-corticosteroid prescriptions made within 7 days before or after the index date (Table). Race/ethnicity data are unavailable in the commercial/Medicare database, and geographic data are unavailable in the Medicaid database.

Results

The prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis was 3.7 per 1000 commercial/Medicare outpatients and 7.8 per 1000 Medicaid outpatients (eTable 1). Prevalence was highest among patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 30.3 per 1000; Medicaid, 43.6 per 1000), followed by patients 65 years or older (commercial/Medicare, 7.4 per 1000; Medicaid, 7.5 per 1000). Prevalence was higher among females compared with males (commercial/Medicare, 4.8 vs 2.4 per 1000, respectively; Medicaid, 8.8 vs 6.4 per 1000, respectively). Among Medicaid patients, prevalence was highest among those of other race, non-Hispanic (8.9 per 1000) and White non-Hispanic patients (7.5 per 1000). In the commercial/Medicare dataset, prevalence was highest in patients residing in the Midwest (4.4 per 1000) and the South (4.0 per 1000).

Diaper dermatitis was listed as a concurrent diagnosis among 51% of patients aged 0 to 3 years in both datasets (eTable 2). Diabetes (commercial/Medicare, 32%; Medicaid, 36%) and immunosuppressive conditions (commercial/Medicare, 10%; Medicaid, 7%) were most frequent among patients aged 65 years or older. Obesity was most commonly listed as a concurrent diagnosis among patients aged 35 to 64 years (commercial/Medicare, 17%; Medicaid, 23%).

Patients aged 18 to 34 years had the highest rates of diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date (commercial/Medicare, 9%; Medicaid, 10%). Topical antifungal medications (primarily nystatin) were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 67%; Medicaid, 70%). Topical combination antifungal-corticosteroid medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (16%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (8%). Topical onychomycosis treatments were prescribed for fewer than 1% of patients in both datasets. Oral antifungal medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (26%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (24%). Fewer than 11% of patients across all age groups in both datasets were prescribed both topical and oral antifungal medications.

Comment

Our analysis provides preliminary insight into the prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis in the United States based on health insurance claims data. Higher prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis among patients with Medicaid compared with those with commercial/Medicare health insurance is consistent with previous studies showing increased rates of other superficial fungal infections (eg, dermatophytosis) among patients of lower socioeconomic status.2 This finding could reflect differences in underlying health status or reduced access to health care, which could delay treatment or follow-up care and potentially lead to prolonged exposure to conditions favoring the development of candidiasis.

In both the commercial/Medicare health insurance and Medicaid datasets, prevalence of diagnosis codes for candidiasis of the skin and nails was highest among infants and toddlers. Diaper dermatitis also was observed in more than half of patients aged 0 to 3 years; this is a well-established risk factor for cutaneous candidiasis, as immature skin barrier function and prolonged exposure to moisture and occlusion facilitate fungal overgrowth.3 In adults, diabetes and obesity were among the most frequent comorbidities observed; both conditions are recognized risk factors for superficial candidiasis due to their impact on immune function and skin integrity.4

In both study cohorts, diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date was infrequent (≤10%), consistent with most cases being diagnosed clinically.5 Topical antifungals, especially nystatin, were most frequently prescribed for young children, while oral antifungals were more frequently prescribed for adults; nystatin is one of the most well-studied topical treatments for cutaneous candidiasis, and oral fluconazole is the primary systemic treatment for cutaneous candidiasis.1 In our study, the ICD-10-CM code B37.2 appeared to be used primarily for diagnosis of skin rather than nail infections based on the low proportions of patients who received treatment that was onychomycosis specific.

Our study was limited by potential misclassification inherent to data based on diagnosis codes; incomplete capture of underlying conditions given the short continuous enrollment criteria; and lack of information about affected body site(s) and laboratory results, including data identifying the Candida species. A previous study found that Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans were the most common species involved in candidiasis of the skin and nails and that one-third of isolates exhibited low sensitivity to commonly used antifungals.6 For nails, Candida species are sometimes contaminants rather than pathogens.

Conclusion

Our findings provide a baseline understanding of the epidemiology of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States. The growing threat of antifungal resistance, particularly among non-albicans Candida species, underscores the need for appropriate use of antifungals.7 Future epidemiologic studies about laboratory-confirmed candidiasis of the skin and nails to understand causative species and drug resistance would be useful, as would further investigation into disparities.

Candida is a common commensal organism of human skin and mucous membranes. Candidiasis of the skin and nails is caused by overgrowth of Candida species due to excess skin moisture, skin barrier disruption, or immunosuppression. Candidiasis of the skin manifests as red, moist, itchy patches that develop particularly in skin folds. Nail involvement is associated with onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and subungual debris.1 Data on the prevalence of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States are scarce. In this study, we evaluated the prevalence, characteristics, and treatment practices of candidiasis of the skin and nails using data from 2 large US health insurance claims databases.

Methods

We used the 2023 Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases (https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases) to identify outpatients with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code B37.2 for candidiasis of the skin and nails. The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases include health insurance claims data submitted by large employers and health plans for more than 19 million patients throughout the United States, and the Multi-State Medicaid database includes similar data from more than 5 million patients across several geographically dispersed states. The index date for each patient corresponded with their first qualifying diagnosis of skin and nail candidiasis during January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. Inclusion in the study required continuous insurance enrollment from 30 days prior to 7 days after the index date, resulting in exclusion of 7% of commercial/Medicare patients and 8% of Medicaid patients. Prevalence per 1000 outpatients was calculated, with stratification by demographic characteristics.

We examined selected diagnoses made on or within 30 days before the index date, diagnostic testing performed within the 7 days before or after the index date after using specific Current Procedural Terminology codes, and outpatient antifungal and combination antifungal-corticosteroid prescriptions made within 7 days before or after the index date (Table). Race/ethnicity data are unavailable in the commercial/Medicare database, and geographic data are unavailable in the Medicaid database.

Results

The prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis was 3.7 per 1000 commercial/Medicare outpatients and 7.8 per 1000 Medicaid outpatients (eTable 1). Prevalence was highest among patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 30.3 per 1000; Medicaid, 43.6 per 1000), followed by patients 65 years or older (commercial/Medicare, 7.4 per 1000; Medicaid, 7.5 per 1000). Prevalence was higher among females compared with males (commercial/Medicare, 4.8 vs 2.4 per 1000, respectively; Medicaid, 8.8 vs 6.4 per 1000, respectively). Among Medicaid patients, prevalence was highest among those of other race, non-Hispanic (8.9 per 1000) and White non-Hispanic patients (7.5 per 1000). In the commercial/Medicare dataset, prevalence was highest in patients residing in the Midwest (4.4 per 1000) and the South (4.0 per 1000).