User login

A 62-year-old black nursing home resident was transported to the hospital emergency department with fever of 102°F, new-onset atrial fibrillation (A-fib), and dementia. His medical history was significant for hypertension and multiple strokes.

His inpatient work-up for A-fib and dementia revealed a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level below 0.005 µIU/mL (normal range, 0.3 to 3.0 µIU/mL). Results of thyroid function testing (TFT) revealed a triiodothyronine (T3) level within normal range but a free thyroxine (T4) level of 2.9 ng/dL (normal range, 0.7 to 1.5 ng/dL) and a total T4 of 17.8 µg/dL (normal, 4.5 to 12.0 µg/dL). The abnormal TSH and T4 levels were considered suggestive of a thyrotoxic state, warranting an endocrinology consult. Cardiology was consulted regarding new-onset A-fib.

During history taking, the patient denied any shortness of breath, cough, palpitations, heat intolerance, anxiety, tremors, insomnia, dysphagia, diarrhea, dysuria, weight loss, or recent ingestion of iodine-containing medications or supplements.

On examination, the patient was febrile, with a blood pressure of 106/71 mm Hg; pulse, 74 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 98% to 99% on room air. ECG showed a normal sinus rhythm and a ventricular rate of 64 beats/min.

The patient's weight was 58.9 kg, and his height, 63" (BMI, 22.8). The patient had no skin changes, and his mucous membranes were slightly moist. The patient's head was atraumatic and normocephalic. His extraocular movements were intact, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light, with nonicteric sclera. There was no proptosis or ophthalmoplegia. The patient's neck was supple, with no jugular venous distension, tracheal deviation, or thyromegaly.

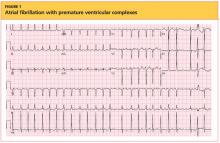

The cardiovascular exam revealed an irregular heartbeat, and repeat ECG showed A-fib with a ventricular rate of 151 beats/min (see Figure 1). The patient's chest was clear, with no wheezing or rhonchi. The abdomen was soft and slightly obese, and bowel sounds were present. The neurologic examination revealed no hyperreflexia. The patient's mental status was altered at times and he was alert, awake, and oriented to others. His speech was slightly slow, and some left-sided weakness was noted.

As recommended during the endocrinology consult, the patient underwent an I-123 sodium iodide thyroid scan, which showed faint uptake at the base of the neck, slightly to the left of midline; and a 24-hour radioactive iodide uptake (RAIU), which measured 2.8% (normal range, 8% to 35%).

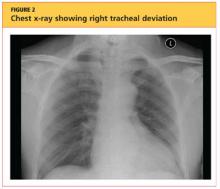

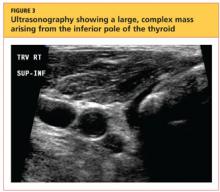

The patient's chest X-ray showed a right tracheal deviation not previously noted on physical examination (see Figure 2); the possible cause of a thyroid mass was considered. Subsequent ultrasonography of the thyroid revealed generally normal dimensions and parenchymal echogenicity. However, a large complex mass was detected, arising from the inferior pole of the thyroid and displacing the trachea toward the right (see Figure 3). According to the radiologist's notes, the mass contained both solid and cystic elements, scattered calcifications, and foci of flow on color Doppler. It measured about 6 cm in the largest (transverse) dimension. A 2.0-mm nodule was noted in the isthmus, slightly to the right of midline, consistent with multinodular goiter.

Following the cardiology consult, a diltiazem drip was initiated, but the patient was later optimized on flecainide for rhythm control and metoprolol for rate control. He was also initially anticoagulated using a heparin drip and bridged to warfarin, with target international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 3.0. Echocardiography revealed normal systolic function with ejection fraction of 55%, left ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 35 mm Hg, and no pericardial effusions or valvular disease.

Regarding the patient's unexplained fever, results of chest imaging were negative for signs of pneumonia or atelectasis, which might have suggested a pulmonary cause. Urinalysis results were normal. Complete blood count showed no leukocytosis. The patient's fever subsided within 48 hours.

The differential diagnosis included Graves' disease, toxic multinodular goiter, Jod-Basedow syndrome, and subacute thyroiditis.

Graves' disease, an autoimmune disease with an unknown trigger, is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. In affected patients, the thyroid gland overproduces thyroid hormones, leading to thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis can result in multiple clinical signs and symptoms, including Graves' ophthalmopathy, pretibial myxedema, and goiter; TFT results typically include elevated T3 and T4 and low TSH.1-5 In the case patient (who had no history of thyroid disease, nor clinical signs or symptoms of Graves' disease), low uptake of iodine on thyroid scan precluded this diagnosis.

Toxic multinodular goiter, the second most common cause of hyperthyroidism, can be responsible for A-fib, tachycardia, and congestive heart failure.6,7 Iodine deficiency causes enlargement of the thyroid gland, where numerous nodules can develop, as seen in the case patient. These nodules can function independently, sometimes producing excess thyroid hormone; this leads to hyperplasia of the thyroid gland, resulting in a nontoxic multinodular goiter. From this goiter, a toxic multinodular goiter can emerge insidiously. However, in this condition, RAIU typically exceeds 30%; in the case patient, low 24-hour RAIU (2.8%) and the absence of functioning nodules on scanning made it possible to rule out this diagnosis.

Jod-Basedow syndrome refers to hyperthyroidism that develops as a result of administration of iodide, either as a dietary supplement or as IV contrast medium, or as an adverse effect of the antiarrhythmic drug amiodarone. This phenomenon is usually seen in a patient with endemic goiter.8-11 The relatively limited nature of the case patient's goiter and absence of a precipitating exposure to iodine made this diagnosis highly unlikely.

Subacute thyroiditis is a condition to which the patient's abnormal TFT results could reasonably be attributed. The patient had a substernal multinodular goiter that could not be palpated on physical examination, but it was visualized in the extended lower neck during thyroid scintigraphy.3 RAIU was minimal—a typical finding in this disorder,6 as TSH is suppressed by leakage of the excessive amounts of thyroid hormone. A tentative diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was made.

As subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting disorder, the patient was not started on any medications for hyperthyroidism but was advised to follow up with his primary care provider or an endocrinologist for repeat TFT and for fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the large thyroid nodule (a complex mass, containing cystic elements and calcifications, with a potential for malignancy) to rule out thyroid cancer.

Repeat ECG before discharge showed normal sinus rhythm with a ventricular rate of 74 beats/min. The patient was alert, awake, and oriented at discharge. He was continued on flecainide, metoprolol, and warfarin and advised to follow up with his primary care provider regarding his target INR.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of subacute thyroiditis, according to findings reported in 2003 from the Rochester Epidemiology Project in Olmsted County, Minnesota,12 is 12.1 cases per 100,000/year, with a higher incidence in women than men. It is most common in young adults and decreases with advancing age. Coxsackie virus, adenovirus, mumps, echovirus, influenza, and Epstein-Barr virus have been implicated in the disorder.12,13

Subacute thyroiditis is associated with a triphasic clinical course of hyperthyroidism, then hypothyroidism, then a return to normal thyroid function—as was seen in the case patient. Onset of subacute thyroiditis has been associated with recent viral infection, which may serve as a precipitant. The cause of this patient's high fever was never identified; thus, the etiology may have been viral.

The initial high thyroid hormone levels result from inflammation of thyroid tissue and release of preformed thyroid hormone into the circulation.6 At this point, TSH is suppressed and patients have very low RAIU, as was true in the case patient.

The condition is self-limiting and does not require treatment in the majority of patients, as TFT results return to normal levels within about two months.6 Patients can appear extremely ill due to thyrotoxicosis from subacute thyroiditis, but this usually lasts no longer than six to eight weeks.3 Subacute thyroiditis can be associated with atrial arrhythmia or heart failure.14,15

PATIENT OUTCOME

New-onset A-fib was attributed to the patient's thyrotoxicosis, which in turn was caused by subacute thyroiditis. He had a multinodular goiter, although he had not received any iodine supplements or IV contrast. As in most cases of subacute thyroiditis, no precipitating event was identified. However, given this patient's residence in a nursing facility and presentation with a high fever with no identifiable cause, a viral etiology for his subacute thyroiditis is possible.6

The patient's dementia may have been secondary to acute thyrotoxicosis, as his mental state improved during the hospital stay. His vitamin B12, folate, and A1C levels were within normal range. CT of the head showed multiple chronic infarcts and cerebral atrophy, and MRI of the brain indicated microvascular ischemic disease.

The patient was readmitted one month later for an episode of near-syncope (which, it was concluded, was a vasovagal episode). At that time, his TSH was found normal at 1.350 µIU/mL. Flecainide and metoprolol were discontinued; he was started on diltiazem for continued rate and rhythm control (as recommended by cardiology) and continued on warfarin.

CONCLUSION

In this case, subacute thyroiditis was most likely caused by a viral infection that led to destruction of the normal thyroid follicles and release of their preformed thyroid hormone into the circulation; this in turn led to sudden-onset A-fib. The diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was suggested based on the abnormalities seen in this patient's TFT results, coupled with the suppressed RAIU—a typical finding in this disease.

Because subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting condition, there is no role for antithyroid medication. Instead, treatment should be focused on relieving the patient's symptoms, such as ß-blockade or calcium channel blockers for tachycardia and corticosteroids or NSAIDs for neck pain.

REFERENCES

1. Weetman AP. Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(17):1236-1248.

2. Delgado Hurtado JJ, Pineda M. Images in medicine: Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364(20):1955.

3. Al-Sharif AA, Abujbara MA, Chiacchio S, et al. Contribution of radioiodine uptake measurement and thyroid scintigraphy to the differential diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis. Hell J Nucl Med. 2010;13(2):132-137.

4. Buccelletti F, Carroccia A, Marsiliani D, et al. Utility of routine thyroid-stimulating hormone determination in new-onset atrial fibrillation in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(9):1158-1162.

5. Ross DS. Radioiodine therapy for hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):542-550.

6. Bahn RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(3):456-520.

7. Erickson D, Gharib H, Li H, van Heerden JA. Treatment of patients with toxic multinodular goiter. Thyroid. 1998;8(4):277-282.

8. Basaria S, Cooper DS. Amiodarone and the thyroid. Am J Med. 2005;118(7):706-714.

9. Bogazzi F, Bartalena L, Martino E. Approach to the patient with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2529-2535.

10. El-Shirbiny AM, Stavrou SS, Dnistrian A, et al. Jod-Basedow syndrome following oral iodine and radioiodinated-antibody administration. J Nucl Med. 1997;38(11):1816-1817.

11. Stanbury JB, Ermans AE, Bourdoux P, et al. Iodine-induced hyperthyroidism: occurrence and epidemiology. Thyroid. 1998;8(1):83-100.

12. Fatourechi V, Aniszewski JP, Fatourechi GZ, et al. Clinical features and outcome of subacute thyroiditis in an incidence cohort: Olmsted County, Minnesota, study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(5):2100-2105.

13. Golden SH, Robinson KA, Saldanha I, et al. Clinical review: prevalence and incidence of endocrine and metabolic disorders in the United States: a comprehensive review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(6):1853-1878.

14. Volpé R. The management of subacute (DeQuervain's) thyroiditis. Thyroid. 1993;3(3):253-255.

15. Lee SL. Subacute thyroiditis (2009). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/125648-overview. Accessed April 17, 2012.

A 62-year-old black nursing home resident was transported to the hospital emergency department with fever of 102°F, new-onset atrial fibrillation (A-fib), and dementia. His medical history was significant for hypertension and multiple strokes.

His inpatient work-up for A-fib and dementia revealed a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level below 0.005 µIU/mL (normal range, 0.3 to 3.0 µIU/mL). Results of thyroid function testing (TFT) revealed a triiodothyronine (T3) level within normal range but a free thyroxine (T4) level of 2.9 ng/dL (normal range, 0.7 to 1.5 ng/dL) and a total T4 of 17.8 µg/dL (normal, 4.5 to 12.0 µg/dL). The abnormal TSH and T4 levels were considered suggestive of a thyrotoxic state, warranting an endocrinology consult. Cardiology was consulted regarding new-onset A-fib.

During history taking, the patient denied any shortness of breath, cough, palpitations, heat intolerance, anxiety, tremors, insomnia, dysphagia, diarrhea, dysuria, weight loss, or recent ingestion of iodine-containing medications or supplements.

On examination, the patient was febrile, with a blood pressure of 106/71 mm Hg; pulse, 74 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 98% to 99% on room air. ECG showed a normal sinus rhythm and a ventricular rate of 64 beats/min.

The patient's weight was 58.9 kg, and his height, 63" (BMI, 22.8). The patient had no skin changes, and his mucous membranes were slightly moist. The patient's head was atraumatic and normocephalic. His extraocular movements were intact, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light, with nonicteric sclera. There was no proptosis or ophthalmoplegia. The patient's neck was supple, with no jugular venous distension, tracheal deviation, or thyromegaly.

The cardiovascular exam revealed an irregular heartbeat, and repeat ECG showed A-fib with a ventricular rate of 151 beats/min (see Figure 1). The patient's chest was clear, with no wheezing or rhonchi. The abdomen was soft and slightly obese, and bowel sounds were present. The neurologic examination revealed no hyperreflexia. The patient's mental status was altered at times and he was alert, awake, and oriented to others. His speech was slightly slow, and some left-sided weakness was noted.

As recommended during the endocrinology consult, the patient underwent an I-123 sodium iodide thyroid scan, which showed faint uptake at the base of the neck, slightly to the left of midline; and a 24-hour radioactive iodide uptake (RAIU), which measured 2.8% (normal range, 8% to 35%).

The patient's chest X-ray showed a right tracheal deviation not previously noted on physical examination (see Figure 2); the possible cause of a thyroid mass was considered. Subsequent ultrasonography of the thyroid revealed generally normal dimensions and parenchymal echogenicity. However, a large complex mass was detected, arising from the inferior pole of the thyroid and displacing the trachea toward the right (see Figure 3). According to the radiologist's notes, the mass contained both solid and cystic elements, scattered calcifications, and foci of flow on color Doppler. It measured about 6 cm in the largest (transverse) dimension. A 2.0-mm nodule was noted in the isthmus, slightly to the right of midline, consistent with multinodular goiter.

Following the cardiology consult, a diltiazem drip was initiated, but the patient was later optimized on flecainide for rhythm control and metoprolol for rate control. He was also initially anticoagulated using a heparin drip and bridged to warfarin, with target international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 3.0. Echocardiography revealed normal systolic function with ejection fraction of 55%, left ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 35 mm Hg, and no pericardial effusions or valvular disease.

Regarding the patient's unexplained fever, results of chest imaging were negative for signs of pneumonia or atelectasis, which might have suggested a pulmonary cause. Urinalysis results were normal. Complete blood count showed no leukocytosis. The patient's fever subsided within 48 hours.

The differential diagnosis included Graves' disease, toxic multinodular goiter, Jod-Basedow syndrome, and subacute thyroiditis.

Graves' disease, an autoimmune disease with an unknown trigger, is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. In affected patients, the thyroid gland overproduces thyroid hormones, leading to thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis can result in multiple clinical signs and symptoms, including Graves' ophthalmopathy, pretibial myxedema, and goiter; TFT results typically include elevated T3 and T4 and low TSH.1-5 In the case patient (who had no history of thyroid disease, nor clinical signs or symptoms of Graves' disease), low uptake of iodine on thyroid scan precluded this diagnosis.

Toxic multinodular goiter, the second most common cause of hyperthyroidism, can be responsible for A-fib, tachycardia, and congestive heart failure.6,7 Iodine deficiency causes enlargement of the thyroid gland, where numerous nodules can develop, as seen in the case patient. These nodules can function independently, sometimes producing excess thyroid hormone; this leads to hyperplasia of the thyroid gland, resulting in a nontoxic multinodular goiter. From this goiter, a toxic multinodular goiter can emerge insidiously. However, in this condition, RAIU typically exceeds 30%; in the case patient, low 24-hour RAIU (2.8%) and the absence of functioning nodules on scanning made it possible to rule out this diagnosis.

Jod-Basedow syndrome refers to hyperthyroidism that develops as a result of administration of iodide, either as a dietary supplement or as IV contrast medium, or as an adverse effect of the antiarrhythmic drug amiodarone. This phenomenon is usually seen in a patient with endemic goiter.8-11 The relatively limited nature of the case patient's goiter and absence of a precipitating exposure to iodine made this diagnosis highly unlikely.

Subacute thyroiditis is a condition to which the patient's abnormal TFT results could reasonably be attributed. The patient had a substernal multinodular goiter that could not be palpated on physical examination, but it was visualized in the extended lower neck during thyroid scintigraphy.3 RAIU was minimal—a typical finding in this disorder,6 as TSH is suppressed by leakage of the excessive amounts of thyroid hormone. A tentative diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was made.

As subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting disorder, the patient was not started on any medications for hyperthyroidism but was advised to follow up with his primary care provider or an endocrinologist for repeat TFT and for fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the large thyroid nodule (a complex mass, containing cystic elements and calcifications, with a potential for malignancy) to rule out thyroid cancer.

Repeat ECG before discharge showed normal sinus rhythm with a ventricular rate of 74 beats/min. The patient was alert, awake, and oriented at discharge. He was continued on flecainide, metoprolol, and warfarin and advised to follow up with his primary care provider regarding his target INR.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of subacute thyroiditis, according to findings reported in 2003 from the Rochester Epidemiology Project in Olmsted County, Minnesota,12 is 12.1 cases per 100,000/year, with a higher incidence in women than men. It is most common in young adults and decreases with advancing age. Coxsackie virus, adenovirus, mumps, echovirus, influenza, and Epstein-Barr virus have been implicated in the disorder.12,13

Subacute thyroiditis is associated with a triphasic clinical course of hyperthyroidism, then hypothyroidism, then a return to normal thyroid function—as was seen in the case patient. Onset of subacute thyroiditis has been associated with recent viral infection, which may serve as a precipitant. The cause of this patient's high fever was never identified; thus, the etiology may have been viral.

The initial high thyroid hormone levels result from inflammation of thyroid tissue and release of preformed thyroid hormone into the circulation.6 At this point, TSH is suppressed and patients have very low RAIU, as was true in the case patient.

The condition is self-limiting and does not require treatment in the majority of patients, as TFT results return to normal levels within about two months.6 Patients can appear extremely ill due to thyrotoxicosis from subacute thyroiditis, but this usually lasts no longer than six to eight weeks.3 Subacute thyroiditis can be associated with atrial arrhythmia or heart failure.14,15

PATIENT OUTCOME

New-onset A-fib was attributed to the patient's thyrotoxicosis, which in turn was caused by subacute thyroiditis. He had a multinodular goiter, although he had not received any iodine supplements or IV contrast. As in most cases of subacute thyroiditis, no precipitating event was identified. However, given this patient's residence in a nursing facility and presentation with a high fever with no identifiable cause, a viral etiology for his subacute thyroiditis is possible.6

The patient's dementia may have been secondary to acute thyrotoxicosis, as his mental state improved during the hospital stay. His vitamin B12, folate, and A1C levels were within normal range. CT of the head showed multiple chronic infarcts and cerebral atrophy, and MRI of the brain indicated microvascular ischemic disease.

The patient was readmitted one month later for an episode of near-syncope (which, it was concluded, was a vasovagal episode). At that time, his TSH was found normal at 1.350 µIU/mL. Flecainide and metoprolol were discontinued; he was started on diltiazem for continued rate and rhythm control (as recommended by cardiology) and continued on warfarin.

CONCLUSION

In this case, subacute thyroiditis was most likely caused by a viral infection that led to destruction of the normal thyroid follicles and release of their preformed thyroid hormone into the circulation; this in turn led to sudden-onset A-fib. The diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was suggested based on the abnormalities seen in this patient's TFT results, coupled with the suppressed RAIU—a typical finding in this disease.

Because subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting condition, there is no role for antithyroid medication. Instead, treatment should be focused on relieving the patient's symptoms, such as ß-blockade or calcium channel blockers for tachycardia and corticosteroids or NSAIDs for neck pain.

REFERENCES

1. Weetman AP. Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(17):1236-1248.

2. Delgado Hurtado JJ, Pineda M. Images in medicine: Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364(20):1955.

3. Al-Sharif AA, Abujbara MA, Chiacchio S, et al. Contribution of radioiodine uptake measurement and thyroid scintigraphy to the differential diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis. Hell J Nucl Med. 2010;13(2):132-137.

4. Buccelletti F, Carroccia A, Marsiliani D, et al. Utility of routine thyroid-stimulating hormone determination in new-onset atrial fibrillation in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(9):1158-1162.

5. Ross DS. Radioiodine therapy for hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):542-550.

6. Bahn RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(3):456-520.

7. Erickson D, Gharib H, Li H, van Heerden JA. Treatment of patients with toxic multinodular goiter. Thyroid. 1998;8(4):277-282.

8. Basaria S, Cooper DS. Amiodarone and the thyroid. Am J Med. 2005;118(7):706-714.

9. Bogazzi F, Bartalena L, Martino E. Approach to the patient with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2529-2535.

10. El-Shirbiny AM, Stavrou SS, Dnistrian A, et al. Jod-Basedow syndrome following oral iodine and radioiodinated-antibody administration. J Nucl Med. 1997;38(11):1816-1817.

11. Stanbury JB, Ermans AE, Bourdoux P, et al. Iodine-induced hyperthyroidism: occurrence and epidemiology. Thyroid. 1998;8(1):83-100.

12. Fatourechi V, Aniszewski JP, Fatourechi GZ, et al. Clinical features and outcome of subacute thyroiditis in an incidence cohort: Olmsted County, Minnesota, study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(5):2100-2105.

13. Golden SH, Robinson KA, Saldanha I, et al. Clinical review: prevalence and incidence of endocrine and metabolic disorders in the United States: a comprehensive review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(6):1853-1878.

14. Volpé R. The management of subacute (DeQuervain's) thyroiditis. Thyroid. 1993;3(3):253-255.

15. Lee SL. Subacute thyroiditis (2009). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/125648-overview. Accessed April 17, 2012.

A 62-year-old black nursing home resident was transported to the hospital emergency department with fever of 102°F, new-onset atrial fibrillation (A-fib), and dementia. His medical history was significant for hypertension and multiple strokes.

His inpatient work-up for A-fib and dementia revealed a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level below 0.005 µIU/mL (normal range, 0.3 to 3.0 µIU/mL). Results of thyroid function testing (TFT) revealed a triiodothyronine (T3) level within normal range but a free thyroxine (T4) level of 2.9 ng/dL (normal range, 0.7 to 1.5 ng/dL) and a total T4 of 17.8 µg/dL (normal, 4.5 to 12.0 µg/dL). The abnormal TSH and T4 levels were considered suggestive of a thyrotoxic state, warranting an endocrinology consult. Cardiology was consulted regarding new-onset A-fib.

During history taking, the patient denied any shortness of breath, cough, palpitations, heat intolerance, anxiety, tremors, insomnia, dysphagia, diarrhea, dysuria, weight loss, or recent ingestion of iodine-containing medications or supplements.

On examination, the patient was febrile, with a blood pressure of 106/71 mm Hg; pulse, 74 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 98% to 99% on room air. ECG showed a normal sinus rhythm and a ventricular rate of 64 beats/min.

The patient's weight was 58.9 kg, and his height, 63" (BMI, 22.8). The patient had no skin changes, and his mucous membranes were slightly moist. The patient's head was atraumatic and normocephalic. His extraocular movements were intact, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light, with nonicteric sclera. There was no proptosis or ophthalmoplegia. The patient's neck was supple, with no jugular venous distension, tracheal deviation, or thyromegaly.

The cardiovascular exam revealed an irregular heartbeat, and repeat ECG showed A-fib with a ventricular rate of 151 beats/min (see Figure 1). The patient's chest was clear, with no wheezing or rhonchi. The abdomen was soft and slightly obese, and bowel sounds were present. The neurologic examination revealed no hyperreflexia. The patient's mental status was altered at times and he was alert, awake, and oriented to others. His speech was slightly slow, and some left-sided weakness was noted.

As recommended during the endocrinology consult, the patient underwent an I-123 sodium iodide thyroid scan, which showed faint uptake at the base of the neck, slightly to the left of midline; and a 24-hour radioactive iodide uptake (RAIU), which measured 2.8% (normal range, 8% to 35%).

The patient's chest X-ray showed a right tracheal deviation not previously noted on physical examination (see Figure 2); the possible cause of a thyroid mass was considered. Subsequent ultrasonography of the thyroid revealed generally normal dimensions and parenchymal echogenicity. However, a large complex mass was detected, arising from the inferior pole of the thyroid and displacing the trachea toward the right (see Figure 3). According to the radiologist's notes, the mass contained both solid and cystic elements, scattered calcifications, and foci of flow on color Doppler. It measured about 6 cm in the largest (transverse) dimension. A 2.0-mm nodule was noted in the isthmus, slightly to the right of midline, consistent with multinodular goiter.

Following the cardiology consult, a diltiazem drip was initiated, but the patient was later optimized on flecainide for rhythm control and metoprolol for rate control. He was also initially anticoagulated using a heparin drip and bridged to warfarin, with target international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 3.0. Echocardiography revealed normal systolic function with ejection fraction of 55%, left ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 35 mm Hg, and no pericardial effusions or valvular disease.

Regarding the patient's unexplained fever, results of chest imaging were negative for signs of pneumonia or atelectasis, which might have suggested a pulmonary cause. Urinalysis results were normal. Complete blood count showed no leukocytosis. The patient's fever subsided within 48 hours.

The differential diagnosis included Graves' disease, toxic multinodular goiter, Jod-Basedow syndrome, and subacute thyroiditis.

Graves' disease, an autoimmune disease with an unknown trigger, is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. In affected patients, the thyroid gland overproduces thyroid hormones, leading to thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis can result in multiple clinical signs and symptoms, including Graves' ophthalmopathy, pretibial myxedema, and goiter; TFT results typically include elevated T3 and T4 and low TSH.1-5 In the case patient (who had no history of thyroid disease, nor clinical signs or symptoms of Graves' disease), low uptake of iodine on thyroid scan precluded this diagnosis.

Toxic multinodular goiter, the second most common cause of hyperthyroidism, can be responsible for A-fib, tachycardia, and congestive heart failure.6,7 Iodine deficiency causes enlargement of the thyroid gland, where numerous nodules can develop, as seen in the case patient. These nodules can function independently, sometimes producing excess thyroid hormone; this leads to hyperplasia of the thyroid gland, resulting in a nontoxic multinodular goiter. From this goiter, a toxic multinodular goiter can emerge insidiously. However, in this condition, RAIU typically exceeds 30%; in the case patient, low 24-hour RAIU (2.8%) and the absence of functioning nodules on scanning made it possible to rule out this diagnosis.

Jod-Basedow syndrome refers to hyperthyroidism that develops as a result of administration of iodide, either as a dietary supplement or as IV contrast medium, or as an adverse effect of the antiarrhythmic drug amiodarone. This phenomenon is usually seen in a patient with endemic goiter.8-11 The relatively limited nature of the case patient's goiter and absence of a precipitating exposure to iodine made this diagnosis highly unlikely.

Subacute thyroiditis is a condition to which the patient's abnormal TFT results could reasonably be attributed. The patient had a substernal multinodular goiter that could not be palpated on physical examination, but it was visualized in the extended lower neck during thyroid scintigraphy.3 RAIU was minimal—a typical finding in this disorder,6 as TSH is suppressed by leakage of the excessive amounts of thyroid hormone. A tentative diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was made.

As subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting disorder, the patient was not started on any medications for hyperthyroidism but was advised to follow up with his primary care provider or an endocrinologist for repeat TFT and for fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the large thyroid nodule (a complex mass, containing cystic elements and calcifications, with a potential for malignancy) to rule out thyroid cancer.

Repeat ECG before discharge showed normal sinus rhythm with a ventricular rate of 74 beats/min. The patient was alert, awake, and oriented at discharge. He was continued on flecainide, metoprolol, and warfarin and advised to follow up with his primary care provider regarding his target INR.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of subacute thyroiditis, according to findings reported in 2003 from the Rochester Epidemiology Project in Olmsted County, Minnesota,12 is 12.1 cases per 100,000/year, with a higher incidence in women than men. It is most common in young adults and decreases with advancing age. Coxsackie virus, adenovirus, mumps, echovirus, influenza, and Epstein-Barr virus have been implicated in the disorder.12,13

Subacute thyroiditis is associated with a triphasic clinical course of hyperthyroidism, then hypothyroidism, then a return to normal thyroid function—as was seen in the case patient. Onset of subacute thyroiditis has been associated with recent viral infection, which may serve as a precipitant. The cause of this patient's high fever was never identified; thus, the etiology may have been viral.

The initial high thyroid hormone levels result from inflammation of thyroid tissue and release of preformed thyroid hormone into the circulation.6 At this point, TSH is suppressed and patients have very low RAIU, as was true in the case patient.

The condition is self-limiting and does not require treatment in the majority of patients, as TFT results return to normal levels within about two months.6 Patients can appear extremely ill due to thyrotoxicosis from subacute thyroiditis, but this usually lasts no longer than six to eight weeks.3 Subacute thyroiditis can be associated with atrial arrhythmia or heart failure.14,15

PATIENT OUTCOME

New-onset A-fib was attributed to the patient's thyrotoxicosis, which in turn was caused by subacute thyroiditis. He had a multinodular goiter, although he had not received any iodine supplements or IV contrast. As in most cases of subacute thyroiditis, no precipitating event was identified. However, given this patient's residence in a nursing facility and presentation with a high fever with no identifiable cause, a viral etiology for his subacute thyroiditis is possible.6

The patient's dementia may have been secondary to acute thyrotoxicosis, as his mental state improved during the hospital stay. His vitamin B12, folate, and A1C levels were within normal range. CT of the head showed multiple chronic infarcts and cerebral atrophy, and MRI of the brain indicated microvascular ischemic disease.

The patient was readmitted one month later for an episode of near-syncope (which, it was concluded, was a vasovagal episode). At that time, his TSH was found normal at 1.350 µIU/mL. Flecainide and metoprolol were discontinued; he was started on diltiazem for continued rate and rhythm control (as recommended by cardiology) and continued on warfarin.

CONCLUSION

In this case, subacute thyroiditis was most likely caused by a viral infection that led to destruction of the normal thyroid follicles and release of their preformed thyroid hormone into the circulation; this in turn led to sudden-onset A-fib. The diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was suggested based on the abnormalities seen in this patient's TFT results, coupled with the suppressed RAIU—a typical finding in this disease.

Because subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting condition, there is no role for antithyroid medication. Instead, treatment should be focused on relieving the patient's symptoms, such as ß-blockade or calcium channel blockers for tachycardia and corticosteroids or NSAIDs for neck pain.

REFERENCES

1. Weetman AP. Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(17):1236-1248.

2. Delgado Hurtado JJ, Pineda M. Images in medicine: Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364(20):1955.

3. Al-Sharif AA, Abujbara MA, Chiacchio S, et al. Contribution of radioiodine uptake measurement and thyroid scintigraphy to the differential diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis. Hell J Nucl Med. 2010;13(2):132-137.

4. Buccelletti F, Carroccia A, Marsiliani D, et al. Utility of routine thyroid-stimulating hormone determination in new-onset atrial fibrillation in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(9):1158-1162.

5. Ross DS. Radioiodine therapy for hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):542-550.

6. Bahn RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(3):456-520.

7. Erickson D, Gharib H, Li H, van Heerden JA. Treatment of patients with toxic multinodular goiter. Thyroid. 1998;8(4):277-282.

8. Basaria S, Cooper DS. Amiodarone and the thyroid. Am J Med. 2005;118(7):706-714.

9. Bogazzi F, Bartalena L, Martino E. Approach to the patient with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2529-2535.

10. El-Shirbiny AM, Stavrou SS, Dnistrian A, et al. Jod-Basedow syndrome following oral iodine and radioiodinated-antibody administration. J Nucl Med. 1997;38(11):1816-1817.

11. Stanbury JB, Ermans AE, Bourdoux P, et al. Iodine-induced hyperthyroidism: occurrence and epidemiology. Thyroid. 1998;8(1):83-100.

12. Fatourechi V, Aniszewski JP, Fatourechi GZ, et al. Clinical features and outcome of subacute thyroiditis in an incidence cohort: Olmsted County, Minnesota, study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(5):2100-2105.

13. Golden SH, Robinson KA, Saldanha I, et al. Clinical review: prevalence and incidence of endocrine and metabolic disorders in the United States: a comprehensive review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(6):1853-1878.

14. Volpé R. The management of subacute (DeQuervain's) thyroiditis. Thyroid. 1993;3(3):253-255.

15. Lee SL. Subacute thyroiditis (2009). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/125648-overview. Accessed April 17, 2012.