User login

Grand Rounds: Woman, 38, With Pulseless Electrical Activity

On an autumn day, a 38-year-old woman with a history of asthma presented to the emergency department (ED) with the chief complaint of shortness of breath (SOB). The patient described her SOB as sudden in onset and not relieved by use of her albuterol inhaler; hence the ED visit.

She denied any chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, orthopnea, upper respiratory tract infection, cough, wheezing, fever or chills, headache, vision changes, body aches, sick contacts, or pets at home. She said she uses her albuterol inhaler as needed, and that she had used it that day for the first time in “a few months.” She denied any history of intubation or steroid use. Additionally, she had not been seen by a primary care provider in years.

The woman, a native of Ghana, had been living in the United States for many years. She denied any recent travel or exposure to toxic chemicals; any use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs; or any history of sexually transmitted disease.

The patient was afebrile (temperature, 98.6°F), with a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min; blood pressure, 144/69 mm Hg; and ventricular rate, 125 beats/min. On physical examination, her extraocular movements were intact; pupils were equal, round, reactive to light and accommodation; and sclera were nonicteric. The patient’s head was normocephalic and atraumatic, and the neck was supple with normal range of motion and no jugular venous distension or lymphadenopathy. Her mucous membranes were moist with no pharyngeal erythema or exudates. Cardiovascular examination, including ECG, revealed tachycardia but no murmurs or gallops.

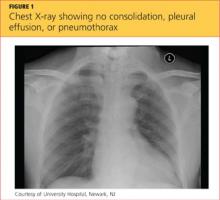

While being evaluated in the ED, the patient became tachypneic and began to experience respiratory distress. She was intubated for airway protection, at which time she developed pulseless electrical activity (PEA), with 30 beats/min. She responded to atropine and epinephrine injections. A repeat ECG showed sinus tachycardia and right atrial enlargement with right-axis deviation. Chest x-ray (see Figure 1) showed no consolidation, pleural effusion, or pneumothorax.

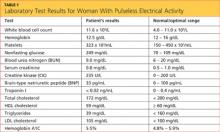

Results from the patient’s lab work are shown in the table, above. Negative results were reported for a urine pregnancy test.

Since there was no clear etiology for the patient’s PEA, she underwent pan-culturing, with the following tests ordered: HIV antibody testing, immunovirology for influenza A and B viruses, and urine toxicology. Doppler ultrasound of the bilateral lower extremities was also ordered, in addition to chest CT and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography (TTE and TEE, respectively). The patient was intubated and transferred to the medical ICU for further management.

The differential diagnosis included cardiac tamponade, acute MI, acute pulmonary embolus (PE), tension pneumothorax, hypovolemia, and asthma exacerbated by viral or bacterial infection.1,2 Although the case patient presented with PEA, she did not have the presenting signs of cardiac tamponade known as Beck’s triad: hypotension, jugular venous distension, and muffled heart sounds.3 TTE showed an ejection fraction of 65% and grade 2 diastolic dysfunction but no pericardial effusions (which accumulate rapidly in the patient with cardiac tamponade, resulting from fluid buildup in the pericardial layers),4 and TEE showed no atrial thrombi (which can masquerade as cardiac tamponade5). The patient had no signs of trauma and denied any history of malignancy (both potential causes of cardiac tamponade). Chest x-ray showed normal heart size and no pneumothorax, consolidations, or pleural effusions.4,6-8 Thus, the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade was ruled out.

Common presenting symptoms of acute MI include sudden-onset chest pain, SOB, palpitations, dizziness, nausea, and/or vomiting. Women may experience less dramatic symptoms—often little more than SOB and fatigue.9 According to a 2000 consensus document from a joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology committee10 in which MI was redefined, the diagnosis of MI relies on a rise in cardiac troponin levels, typical MI symptoms, and changes in ECG showing pathological Q waves or ST elevation or depression. The case patient’s troponin I level was less than 0.02 ng/mL, and ECG did not reveal Q waves or ST-T wave changes; additionally, since the patient had no chest pain, palpitations, diaphoresis, nausea, or vomiting, acute MI was ruled out.

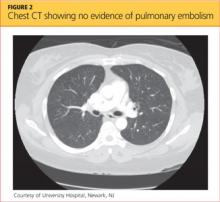

Blood clots capable of blocking the pulmonary artery usually originate in the deep veins of the lower extremities.11 Three main factors, called Virchow’s triad, are known to contribute to these deep vein thromboses (DVTs): venous stasis, endothelial injury, and a hypercoagulability state.12,13 The patient had denied any trauma, recent travel, history of malignancy, or use of tobacco or oral contraceptives, and the result of her urine pregnancy test was negative. Even though the patient presented with tachypnea and acute SOB, with ECG showing right-axis deviation and tachycardia (common presenting signs and symptoms for PE), her chest CT showed no evidence of PE (see Figure 2); additionally, Doppler ultrasound of the bilateral lower extremities revealed no DVTs. Thus, PE was also excluded.

Tension pneumothorax was also ruled out, as chest x-ray showed neither mediastinal shift nor tracheal deviation, and the patient had denied any trauma. Laboratory analyses did not indicate hyponatremia, and the patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit were satisfactory. She was tachycardic on admission, but her blood pressure was stable. As the patient denied any use of vasodilators or diuretics, hypovolemia was ruled out.

Patients experiencing asthma exacerbation can present with acute SOB, which usually resolves following use of IV steroids, nebulizer therapy, and inhaler treatments. Despite being administered IV methylprednisolone and magnesium sulfate in the ED, the patient experienced PEA and respiratory distress and required intubation for airway protection.

The HIV test was nonreactive, and blood and urine cultures did not show any growth. Results of tests for Legionella urinary antigen and Streptococcus pneumoniae antigen were negative. Sputum culture showed normal flora. Immunovirology testing, however, was positive for both influenza A and B antigens.

Chest X-ray showed no acute pulmonary pathology, nor did chest CT show any central, interlobar, or segmental embolism or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. It was determined that the patient’s acute SOB might represent asthma exacerbation secondary to influenza viral infection. Her PEA was attributed to possible acute pericarditis secondary to concomitant influenza A and B viral infection.

DISCUSSION

Currently, the CDC recognizes three types of influenza virus: A, B, and C.14 Only influenza A viruses are further classified into subtypes, based on the presence of surface proteins called hemagglutinin (HA) or neuraminidase (NA) glycoproteins. Humans can be infected by influenza A subtypes H1N1 and H3N2.14 Influenza B viruses, found mostly in humans, are associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Influenza A and B viruses are further classified into strains that change with each flu season—thus, the need to update vaccinations against influenza A and B each year. No vaccination exists against influenza C virus, which is known to cause only mild illness in humans.15

In patients with asthma (as in the case patient), chronic bronchitis, or emphysema, infection with the influenza virus can manifest with SOB, in addition to the more common symptoms of fever, sore throat, headache, rhinorrhea, chills, muscle aches, and general discomfort.16 Patients with coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure (CHF), and/or a history of smoking may experience more severe symptoms and increased risk for influenza-associated mortality than do other patients.17,18

Rare cardiac complications of influenza infections are myocarditis and benign acute pericarditis; myocarditis can progress to CHF and death.19,20 A case of acute myopericarditis was reported by Proby et al21 in a patient with acute influenza A infection who developed pericardial effusions, myositis, tamponade, and pleurisy. That patient recovered after pericardiocentesis and administration of inotropic drugs.

In the literature, a few cases of acute pericarditis have been reported in association with administration of the influenza vaccination.22,23

In the case patient, the diagnosis of influenza A and B was made following testing of nasal and nasopharyngeal swabs with an immunochromatographic assay that uses highly sensitive monoclonal antibodies to detect influenza A and B nucleoprotein antigens.24,25

According to reports in the literature, two-thirds of cases of acute pericarditis are caused by infection, most commonly viral infection (including influenza virus, adenovirus, enterovirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B virus, and herpes simplex virus).26,27 Other etiologies for acute pericarditis are autoimmune (accounting for less than 10% of cases) and neoplastic conditions (5% to 7% of cases).26

PATIENT OUTCOME

Consultation with an infectious disease specialist was obtained. The patient was placed under droplet isolation precautions and was started on a nebulizer, IV steroid treatments, and oseltamivir 75 mg by mouth every 12 hours. She was transferred to a medical floor, where she completed a five-day course of oseltamivir.

As a result of timely intervention, the patient was discharged in stable condition on a therapeutic regimen that included albuterol, fluticasone, and salmeterol inhalation, in addition to tapered-dose steroids. She was advised to follow up with her primary care provider and at the pulmonary clinic.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of acute pericarditis in a patient with concomitant acute infections with influenza A and B. According to conclusions reached in recent literature, further research is needed to explain the pathophysiology of influenza viral infections, associated cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, and the degree to which these can be prevented by influenza vaccination.1,28 Also to be pursued through research is a better understanding of the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza viruses, especially in children and in adults affected by asthma, cardiac disease, and/or obesity.

REFERENCES

1. Finelli L, Chaves SS. Influenza and acute myocardial infarction. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(12):

1701-1704.

2. Steiger HV, Rimbach K, Müller E, Breitkreutz R. Focused emergency echocardiography: lifesaving tool for a 14-year-old girl suffering out-of-hospital pulseless electrical activity arrest because of cardiac tamponade. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(2): 103-105.

3. Goodman A, Perera P, Mailhot T, Mandavia D. The role of bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade.

J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012;5(1):72-75.

4. Restrepo CS, Lemos DF, Lemos JA, et al. Imaging findings in cardiac tamponade with emphasis on CT. Radiographics. 2007;27(6):1595-1610.

5. Papanagnou D, Stone MB. Massive right atrial thrombus masquerading as cardiac tamponade. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):E11.

6. Saito Y, Donohue A, Attai S, et al. The syndrome of cardiac tamponade with “small” pericardial effusion. Echocardiography. 2008;25(3): 321-327.

7. Lin E, Boire A, Hemmige V, et al. Cardiac tamponade mimicking tuberculous pericarditis as the initial presentation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in a 58-year-old woman: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:246.

8. Meniconi A, Attenhofer Jost CH, Jenni R. How to survive myocardial rupture after myocardial infarction. Heart. 2000;84(5):552.

9. Kosuge M, Kimura K, Ishikawa T, et al. Differences between men and women in terms of clinical features of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2006;70(3):222-226.

10. Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined: a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3):959-969.

11. Goldhaber SZ. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2008:1651–1657.

12. Brooks EG, Trotman W, Wadsworth MP, et al. Valves of the deep venous system: an overlooked risk factor. Blood. 2009;114(6):1276-1279.

13. Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Is Virchow’s triad complete? Blood. 2009;114(6):1138-1139.

14. CDC. Seasonal influenza (flu): types of influenza viruses (2012). www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/types.htm. Accessed October 24, 2012.

15. CDC. Seasonal influenza (flu)(2012). www.cdc .gov/flu. Accessed October 24, 2012.

16. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

17. Angelo SJ, Marshall PS, Chrissoheris MP, Chaves AM. Clinical characteristics associated with poor outcome in patients acutely infected with Influenza A. Conn Med. 2004;68(4):199-205.

18. Murin S, Bilello K. Respiratory tract infections: another reason not to smoke. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(10):916-920.

19. Ray CG, Icenogle TB, Minnich LL, et al. The use of intravenous ribavirin to treat influenza virus–associated acute myocarditis. J Infect Dis. 1989; 159(5):829-836.

20. Fairley CK, Ryan M, Wall PG, Weinberg J. The organism reported to cause infective myocarditis and pericarditis in England and Wales. J Infect. 1996;32(3):223-225.

21. Proby CM, Hackett D, Gupta S, Cox TM. Acute myopericarditis in influenza A infection. Q J Med. 1986;60(233):887-892.

22. Streifler JJ, Dux S, Garty M, Rosenfeld JB. Recurrent pericarditis: a rare complication of influenza vaccination. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981; 283(6290):526-527.

23. Desson JF, Leprévost M, Vabret F, Davy A. Acute benign pericarditis after anti-influenza vaccination [in French]. Presse Med. 1997;26 (9):415.

24. BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B Test Kit (product instructions). www.diagnosticsdirect2u.com/images/PDF/Binax%20Now%20416-022%20PPI .pdf. Accessed October 24, 2012.

25. 510(k) Substantial Equivalence Determination Decision Summary [BinaxNow® Influenza A & B Test] (2009). www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/K062109.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2012.

26. Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121(7):916-928.

27. Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al; Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(7):587-610.

28. McCullers JA, Hayden FG. Fatal influenza B infections: time to reexamine influenza research priorities. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(6):870-872.

On an autumn day, a 38-year-old woman with a history of asthma presented to the emergency department (ED) with the chief complaint of shortness of breath (SOB). The patient described her SOB as sudden in onset and not relieved by use of her albuterol inhaler; hence the ED visit.

She denied any chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, orthopnea, upper respiratory tract infection, cough, wheezing, fever or chills, headache, vision changes, body aches, sick contacts, or pets at home. She said she uses her albuterol inhaler as needed, and that she had used it that day for the first time in “a few months.” She denied any history of intubation or steroid use. Additionally, she had not been seen by a primary care provider in years.

The woman, a native of Ghana, had been living in the United States for many years. She denied any recent travel or exposure to toxic chemicals; any use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs; or any history of sexually transmitted disease.

The patient was afebrile (temperature, 98.6°F), with a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min; blood pressure, 144/69 mm Hg; and ventricular rate, 125 beats/min. On physical examination, her extraocular movements were intact; pupils were equal, round, reactive to light and accommodation; and sclera were nonicteric. The patient’s head was normocephalic and atraumatic, and the neck was supple with normal range of motion and no jugular venous distension or lymphadenopathy. Her mucous membranes were moist with no pharyngeal erythema or exudates. Cardiovascular examination, including ECG, revealed tachycardia but no murmurs or gallops.

While being evaluated in the ED, the patient became tachypneic and began to experience respiratory distress. She was intubated for airway protection, at which time she developed pulseless electrical activity (PEA), with 30 beats/min. She responded to atropine and epinephrine injections. A repeat ECG showed sinus tachycardia and right atrial enlargement with right-axis deviation. Chest x-ray (see Figure 1) showed no consolidation, pleural effusion, or pneumothorax.

Results from the patient’s lab work are shown in the table, above. Negative results were reported for a urine pregnancy test.

Since there was no clear etiology for the patient’s PEA, she underwent pan-culturing, with the following tests ordered: HIV antibody testing, immunovirology for influenza A and B viruses, and urine toxicology. Doppler ultrasound of the bilateral lower extremities was also ordered, in addition to chest CT and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography (TTE and TEE, respectively). The patient was intubated and transferred to the medical ICU for further management.

The differential diagnosis included cardiac tamponade, acute MI, acute pulmonary embolus (PE), tension pneumothorax, hypovolemia, and asthma exacerbated by viral or bacterial infection.1,2 Although the case patient presented with PEA, she did not have the presenting signs of cardiac tamponade known as Beck’s triad: hypotension, jugular venous distension, and muffled heart sounds.3 TTE showed an ejection fraction of 65% and grade 2 diastolic dysfunction but no pericardial effusions (which accumulate rapidly in the patient with cardiac tamponade, resulting from fluid buildup in the pericardial layers),4 and TEE showed no atrial thrombi (which can masquerade as cardiac tamponade5). The patient had no signs of trauma and denied any history of malignancy (both potential causes of cardiac tamponade). Chest x-ray showed normal heart size and no pneumothorax, consolidations, or pleural effusions.4,6-8 Thus, the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade was ruled out.

Common presenting symptoms of acute MI include sudden-onset chest pain, SOB, palpitations, dizziness, nausea, and/or vomiting. Women may experience less dramatic symptoms—often little more than SOB and fatigue.9 According to a 2000 consensus document from a joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology committee10 in which MI was redefined, the diagnosis of MI relies on a rise in cardiac troponin levels, typical MI symptoms, and changes in ECG showing pathological Q waves or ST elevation or depression. The case patient’s troponin I level was less than 0.02 ng/mL, and ECG did not reveal Q waves or ST-T wave changes; additionally, since the patient had no chest pain, palpitations, diaphoresis, nausea, or vomiting, acute MI was ruled out.

Blood clots capable of blocking the pulmonary artery usually originate in the deep veins of the lower extremities.11 Three main factors, called Virchow’s triad, are known to contribute to these deep vein thromboses (DVTs): venous stasis, endothelial injury, and a hypercoagulability state.12,13 The patient had denied any trauma, recent travel, history of malignancy, or use of tobacco or oral contraceptives, and the result of her urine pregnancy test was negative. Even though the patient presented with tachypnea and acute SOB, with ECG showing right-axis deviation and tachycardia (common presenting signs and symptoms for PE), her chest CT showed no evidence of PE (see Figure 2); additionally, Doppler ultrasound of the bilateral lower extremities revealed no DVTs. Thus, PE was also excluded.

Tension pneumothorax was also ruled out, as chest x-ray showed neither mediastinal shift nor tracheal deviation, and the patient had denied any trauma. Laboratory analyses did not indicate hyponatremia, and the patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit were satisfactory. She was tachycardic on admission, but her blood pressure was stable. As the patient denied any use of vasodilators or diuretics, hypovolemia was ruled out.

Patients experiencing asthma exacerbation can present with acute SOB, which usually resolves following use of IV steroids, nebulizer therapy, and inhaler treatments. Despite being administered IV methylprednisolone and magnesium sulfate in the ED, the patient experienced PEA and respiratory distress and required intubation for airway protection.

The HIV test was nonreactive, and blood and urine cultures did not show any growth. Results of tests for Legionella urinary antigen and Streptococcus pneumoniae antigen were negative. Sputum culture showed normal flora. Immunovirology testing, however, was positive for both influenza A and B antigens.

Chest X-ray showed no acute pulmonary pathology, nor did chest CT show any central, interlobar, or segmental embolism or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. It was determined that the patient’s acute SOB might represent asthma exacerbation secondary to influenza viral infection. Her PEA was attributed to possible acute pericarditis secondary to concomitant influenza A and B viral infection.

DISCUSSION

Currently, the CDC recognizes three types of influenza virus: A, B, and C.14 Only influenza A viruses are further classified into subtypes, based on the presence of surface proteins called hemagglutinin (HA) or neuraminidase (NA) glycoproteins. Humans can be infected by influenza A subtypes H1N1 and H3N2.14 Influenza B viruses, found mostly in humans, are associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Influenza A and B viruses are further classified into strains that change with each flu season—thus, the need to update vaccinations against influenza A and B each year. No vaccination exists against influenza C virus, which is known to cause only mild illness in humans.15

In patients with asthma (as in the case patient), chronic bronchitis, or emphysema, infection with the influenza virus can manifest with SOB, in addition to the more common symptoms of fever, sore throat, headache, rhinorrhea, chills, muscle aches, and general discomfort.16 Patients with coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure (CHF), and/or a history of smoking may experience more severe symptoms and increased risk for influenza-associated mortality than do other patients.17,18

Rare cardiac complications of influenza infections are myocarditis and benign acute pericarditis; myocarditis can progress to CHF and death.19,20 A case of acute myopericarditis was reported by Proby et al21 in a patient with acute influenza A infection who developed pericardial effusions, myositis, tamponade, and pleurisy. That patient recovered after pericardiocentesis and administration of inotropic drugs.

In the literature, a few cases of acute pericarditis have been reported in association with administration of the influenza vaccination.22,23

In the case patient, the diagnosis of influenza A and B was made following testing of nasal and nasopharyngeal swabs with an immunochromatographic assay that uses highly sensitive monoclonal antibodies to detect influenza A and B nucleoprotein antigens.24,25

According to reports in the literature, two-thirds of cases of acute pericarditis are caused by infection, most commonly viral infection (including influenza virus, adenovirus, enterovirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B virus, and herpes simplex virus).26,27 Other etiologies for acute pericarditis are autoimmune (accounting for less than 10% of cases) and neoplastic conditions (5% to 7% of cases).26

PATIENT OUTCOME

Consultation with an infectious disease specialist was obtained. The patient was placed under droplet isolation precautions and was started on a nebulizer, IV steroid treatments, and oseltamivir 75 mg by mouth every 12 hours. She was transferred to a medical floor, where she completed a five-day course of oseltamivir.

As a result of timely intervention, the patient was discharged in stable condition on a therapeutic regimen that included albuterol, fluticasone, and salmeterol inhalation, in addition to tapered-dose steroids. She was advised to follow up with her primary care provider and at the pulmonary clinic.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of acute pericarditis in a patient with concomitant acute infections with influenza A and B. According to conclusions reached in recent literature, further research is needed to explain the pathophysiology of influenza viral infections, associated cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, and the degree to which these can be prevented by influenza vaccination.1,28 Also to be pursued through research is a better understanding of the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza viruses, especially in children and in adults affected by asthma, cardiac disease, and/or obesity.

REFERENCES

1. Finelli L, Chaves SS. Influenza and acute myocardial infarction. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(12):

1701-1704.

2. Steiger HV, Rimbach K, Müller E, Breitkreutz R. Focused emergency echocardiography: lifesaving tool for a 14-year-old girl suffering out-of-hospital pulseless electrical activity arrest because of cardiac tamponade. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(2): 103-105.

3. Goodman A, Perera P, Mailhot T, Mandavia D. The role of bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade.

J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012;5(1):72-75.

4. Restrepo CS, Lemos DF, Lemos JA, et al. Imaging findings in cardiac tamponade with emphasis on CT. Radiographics. 2007;27(6):1595-1610.

5. Papanagnou D, Stone MB. Massive right atrial thrombus masquerading as cardiac tamponade. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):E11.

6. Saito Y, Donohue A, Attai S, et al. The syndrome of cardiac tamponade with “small” pericardial effusion. Echocardiography. 2008;25(3): 321-327.

7. Lin E, Boire A, Hemmige V, et al. Cardiac tamponade mimicking tuberculous pericarditis as the initial presentation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in a 58-year-old woman: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:246.

8. Meniconi A, Attenhofer Jost CH, Jenni R. How to survive myocardial rupture after myocardial infarction. Heart. 2000;84(5):552.

9. Kosuge M, Kimura K, Ishikawa T, et al. Differences between men and women in terms of clinical features of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2006;70(3):222-226.

10. Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined: a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3):959-969.

11. Goldhaber SZ. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2008:1651–1657.

12. Brooks EG, Trotman W, Wadsworth MP, et al. Valves of the deep venous system: an overlooked risk factor. Blood. 2009;114(6):1276-1279.

13. Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Is Virchow’s triad complete? Blood. 2009;114(6):1138-1139.

14. CDC. Seasonal influenza (flu): types of influenza viruses (2012). www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/types.htm. Accessed October 24, 2012.

15. CDC. Seasonal influenza (flu)(2012). www.cdc .gov/flu. Accessed October 24, 2012.

16. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

17. Angelo SJ, Marshall PS, Chrissoheris MP, Chaves AM. Clinical characteristics associated with poor outcome in patients acutely infected with Influenza A. Conn Med. 2004;68(4):199-205.

18. Murin S, Bilello K. Respiratory tract infections: another reason not to smoke. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(10):916-920.

19. Ray CG, Icenogle TB, Minnich LL, et al. The use of intravenous ribavirin to treat influenza virus–associated acute myocarditis. J Infect Dis. 1989; 159(5):829-836.

20. Fairley CK, Ryan M, Wall PG, Weinberg J. The organism reported to cause infective myocarditis and pericarditis in England and Wales. J Infect. 1996;32(3):223-225.

21. Proby CM, Hackett D, Gupta S, Cox TM. Acute myopericarditis in influenza A infection. Q J Med. 1986;60(233):887-892.

22. Streifler JJ, Dux S, Garty M, Rosenfeld JB. Recurrent pericarditis: a rare complication of influenza vaccination. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981; 283(6290):526-527.

23. Desson JF, Leprévost M, Vabret F, Davy A. Acute benign pericarditis after anti-influenza vaccination [in French]. Presse Med. 1997;26 (9):415.

24. BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B Test Kit (product instructions). www.diagnosticsdirect2u.com/images/PDF/Binax%20Now%20416-022%20PPI .pdf. Accessed October 24, 2012.

25. 510(k) Substantial Equivalence Determination Decision Summary [BinaxNow® Influenza A & B Test] (2009). www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/K062109.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2012.

26. Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121(7):916-928.

27. Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al; Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(7):587-610.

28. McCullers JA, Hayden FG. Fatal influenza B infections: time to reexamine influenza research priorities. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(6):870-872.

On an autumn day, a 38-year-old woman with a history of asthma presented to the emergency department (ED) with the chief complaint of shortness of breath (SOB). The patient described her SOB as sudden in onset and not relieved by use of her albuterol inhaler; hence the ED visit.

She denied any chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, orthopnea, upper respiratory tract infection, cough, wheezing, fever or chills, headache, vision changes, body aches, sick contacts, or pets at home. She said she uses her albuterol inhaler as needed, and that she had used it that day for the first time in “a few months.” She denied any history of intubation or steroid use. Additionally, she had not been seen by a primary care provider in years.

The woman, a native of Ghana, had been living in the United States for many years. She denied any recent travel or exposure to toxic chemicals; any use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs; or any history of sexually transmitted disease.

The patient was afebrile (temperature, 98.6°F), with a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min; blood pressure, 144/69 mm Hg; and ventricular rate, 125 beats/min. On physical examination, her extraocular movements were intact; pupils were equal, round, reactive to light and accommodation; and sclera were nonicteric. The patient’s head was normocephalic and atraumatic, and the neck was supple with normal range of motion and no jugular venous distension or lymphadenopathy. Her mucous membranes were moist with no pharyngeal erythema or exudates. Cardiovascular examination, including ECG, revealed tachycardia but no murmurs or gallops.

While being evaluated in the ED, the patient became tachypneic and began to experience respiratory distress. She was intubated for airway protection, at which time she developed pulseless electrical activity (PEA), with 30 beats/min. She responded to atropine and epinephrine injections. A repeat ECG showed sinus tachycardia and right atrial enlargement with right-axis deviation. Chest x-ray (see Figure 1) showed no consolidation, pleural effusion, or pneumothorax.

Results from the patient’s lab work are shown in the table, above. Negative results were reported for a urine pregnancy test.

Since there was no clear etiology for the patient’s PEA, she underwent pan-culturing, with the following tests ordered: HIV antibody testing, immunovirology for influenza A and B viruses, and urine toxicology. Doppler ultrasound of the bilateral lower extremities was also ordered, in addition to chest CT and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography (TTE and TEE, respectively). The patient was intubated and transferred to the medical ICU for further management.

The differential diagnosis included cardiac tamponade, acute MI, acute pulmonary embolus (PE), tension pneumothorax, hypovolemia, and asthma exacerbated by viral or bacterial infection.1,2 Although the case patient presented with PEA, she did not have the presenting signs of cardiac tamponade known as Beck’s triad: hypotension, jugular venous distension, and muffled heart sounds.3 TTE showed an ejection fraction of 65% and grade 2 diastolic dysfunction but no pericardial effusions (which accumulate rapidly in the patient with cardiac tamponade, resulting from fluid buildup in the pericardial layers),4 and TEE showed no atrial thrombi (which can masquerade as cardiac tamponade5). The patient had no signs of trauma and denied any history of malignancy (both potential causes of cardiac tamponade). Chest x-ray showed normal heart size and no pneumothorax, consolidations, or pleural effusions.4,6-8 Thus, the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade was ruled out.

Common presenting symptoms of acute MI include sudden-onset chest pain, SOB, palpitations, dizziness, nausea, and/or vomiting. Women may experience less dramatic symptoms—often little more than SOB and fatigue.9 According to a 2000 consensus document from a joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology committee10 in which MI was redefined, the diagnosis of MI relies on a rise in cardiac troponin levels, typical MI symptoms, and changes in ECG showing pathological Q waves or ST elevation or depression. The case patient’s troponin I level was less than 0.02 ng/mL, and ECG did not reveal Q waves or ST-T wave changes; additionally, since the patient had no chest pain, palpitations, diaphoresis, nausea, or vomiting, acute MI was ruled out.

Blood clots capable of blocking the pulmonary artery usually originate in the deep veins of the lower extremities.11 Three main factors, called Virchow’s triad, are known to contribute to these deep vein thromboses (DVTs): venous stasis, endothelial injury, and a hypercoagulability state.12,13 The patient had denied any trauma, recent travel, history of malignancy, or use of tobacco or oral contraceptives, and the result of her urine pregnancy test was negative. Even though the patient presented with tachypnea and acute SOB, with ECG showing right-axis deviation and tachycardia (common presenting signs and symptoms for PE), her chest CT showed no evidence of PE (see Figure 2); additionally, Doppler ultrasound of the bilateral lower extremities revealed no DVTs. Thus, PE was also excluded.

Tension pneumothorax was also ruled out, as chest x-ray showed neither mediastinal shift nor tracheal deviation, and the patient had denied any trauma. Laboratory analyses did not indicate hyponatremia, and the patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit were satisfactory. She was tachycardic on admission, but her blood pressure was stable. As the patient denied any use of vasodilators or diuretics, hypovolemia was ruled out.

Patients experiencing asthma exacerbation can present with acute SOB, which usually resolves following use of IV steroids, nebulizer therapy, and inhaler treatments. Despite being administered IV methylprednisolone and magnesium sulfate in the ED, the patient experienced PEA and respiratory distress and required intubation for airway protection.

The HIV test was nonreactive, and blood and urine cultures did not show any growth. Results of tests for Legionella urinary antigen and Streptococcus pneumoniae antigen were negative. Sputum culture showed normal flora. Immunovirology testing, however, was positive for both influenza A and B antigens.

Chest X-ray showed no acute pulmonary pathology, nor did chest CT show any central, interlobar, or segmental embolism or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. It was determined that the patient’s acute SOB might represent asthma exacerbation secondary to influenza viral infection. Her PEA was attributed to possible acute pericarditis secondary to concomitant influenza A and B viral infection.

DISCUSSION

Currently, the CDC recognizes three types of influenza virus: A, B, and C.14 Only influenza A viruses are further classified into subtypes, based on the presence of surface proteins called hemagglutinin (HA) or neuraminidase (NA) glycoproteins. Humans can be infected by influenza A subtypes H1N1 and H3N2.14 Influenza B viruses, found mostly in humans, are associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Influenza A and B viruses are further classified into strains that change with each flu season—thus, the need to update vaccinations against influenza A and B each year. No vaccination exists against influenza C virus, which is known to cause only mild illness in humans.15

In patients with asthma (as in the case patient), chronic bronchitis, or emphysema, infection with the influenza virus can manifest with SOB, in addition to the more common symptoms of fever, sore throat, headache, rhinorrhea, chills, muscle aches, and general discomfort.16 Patients with coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure (CHF), and/or a history of smoking may experience more severe symptoms and increased risk for influenza-associated mortality than do other patients.17,18

Rare cardiac complications of influenza infections are myocarditis and benign acute pericarditis; myocarditis can progress to CHF and death.19,20 A case of acute myopericarditis was reported by Proby et al21 in a patient with acute influenza A infection who developed pericardial effusions, myositis, tamponade, and pleurisy. That patient recovered after pericardiocentesis and administration of inotropic drugs.

In the literature, a few cases of acute pericarditis have been reported in association with administration of the influenza vaccination.22,23

In the case patient, the diagnosis of influenza A and B was made following testing of nasal and nasopharyngeal swabs with an immunochromatographic assay that uses highly sensitive monoclonal antibodies to detect influenza A and B nucleoprotein antigens.24,25

According to reports in the literature, two-thirds of cases of acute pericarditis are caused by infection, most commonly viral infection (including influenza virus, adenovirus, enterovirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B virus, and herpes simplex virus).26,27 Other etiologies for acute pericarditis are autoimmune (accounting for less than 10% of cases) and neoplastic conditions (5% to 7% of cases).26

PATIENT OUTCOME

Consultation with an infectious disease specialist was obtained. The patient was placed under droplet isolation precautions and was started on a nebulizer, IV steroid treatments, and oseltamivir 75 mg by mouth every 12 hours. She was transferred to a medical floor, where she completed a five-day course of oseltamivir.

As a result of timely intervention, the patient was discharged in stable condition on a therapeutic regimen that included albuterol, fluticasone, and salmeterol inhalation, in addition to tapered-dose steroids. She was advised to follow up with her primary care provider and at the pulmonary clinic.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of acute pericarditis in a patient with concomitant acute infections with influenza A and B. According to conclusions reached in recent literature, further research is needed to explain the pathophysiology of influenza viral infections, associated cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, and the degree to which these can be prevented by influenza vaccination.1,28 Also to be pursued through research is a better understanding of the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza viruses, especially in children and in adults affected by asthma, cardiac disease, and/or obesity.

REFERENCES

1. Finelli L, Chaves SS. Influenza and acute myocardial infarction. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(12):

1701-1704.

2. Steiger HV, Rimbach K, Müller E, Breitkreutz R. Focused emergency echocardiography: lifesaving tool for a 14-year-old girl suffering out-of-hospital pulseless electrical activity arrest because of cardiac tamponade. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(2): 103-105.

3. Goodman A, Perera P, Mailhot T, Mandavia D. The role of bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade.

J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012;5(1):72-75.

4. Restrepo CS, Lemos DF, Lemos JA, et al. Imaging findings in cardiac tamponade with emphasis on CT. Radiographics. 2007;27(6):1595-1610.

5. Papanagnou D, Stone MB. Massive right atrial thrombus masquerading as cardiac tamponade. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):E11.

6. Saito Y, Donohue A, Attai S, et al. The syndrome of cardiac tamponade with “small” pericardial effusion. Echocardiography. 2008;25(3): 321-327.

7. Lin E, Boire A, Hemmige V, et al. Cardiac tamponade mimicking tuberculous pericarditis as the initial presentation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in a 58-year-old woman: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:246.

8. Meniconi A, Attenhofer Jost CH, Jenni R. How to survive myocardial rupture after myocardial infarction. Heart. 2000;84(5):552.

9. Kosuge M, Kimura K, Ishikawa T, et al. Differences between men and women in terms of clinical features of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2006;70(3):222-226.

10. Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined: a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3):959-969.

11. Goldhaber SZ. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2008:1651–1657.

12. Brooks EG, Trotman W, Wadsworth MP, et al. Valves of the deep venous system: an overlooked risk factor. Blood. 2009;114(6):1276-1279.

13. Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Is Virchow’s triad complete? Blood. 2009;114(6):1138-1139.

14. CDC. Seasonal influenza (flu): types of influenza viruses (2012). www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/types.htm. Accessed October 24, 2012.

15. CDC. Seasonal influenza (flu)(2012). www.cdc .gov/flu. Accessed October 24, 2012.

16. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

17. Angelo SJ, Marshall PS, Chrissoheris MP, Chaves AM. Clinical characteristics associated with poor outcome in patients acutely infected with Influenza A. Conn Med. 2004;68(4):199-205.

18. Murin S, Bilello K. Respiratory tract infections: another reason not to smoke. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(10):916-920.

19. Ray CG, Icenogle TB, Minnich LL, et al. The use of intravenous ribavirin to treat influenza virus–associated acute myocarditis. J Infect Dis. 1989; 159(5):829-836.

20. Fairley CK, Ryan M, Wall PG, Weinberg J. The organism reported to cause infective myocarditis and pericarditis in England and Wales. J Infect. 1996;32(3):223-225.

21. Proby CM, Hackett D, Gupta S, Cox TM. Acute myopericarditis in influenza A infection. Q J Med. 1986;60(233):887-892.

22. Streifler JJ, Dux S, Garty M, Rosenfeld JB. Recurrent pericarditis: a rare complication of influenza vaccination. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981; 283(6290):526-527.

23. Desson JF, Leprévost M, Vabret F, Davy A. Acute benign pericarditis after anti-influenza vaccination [in French]. Presse Med. 1997;26 (9):415.

24. BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B Test Kit (product instructions). www.diagnosticsdirect2u.com/images/PDF/Binax%20Now%20416-022%20PPI .pdf. Accessed October 24, 2012.

25. 510(k) Substantial Equivalence Determination Decision Summary [BinaxNow® Influenza A & B Test] (2009). www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/K062109.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2012.

26. Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121(7):916-928.

27. Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al; Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(7):587-610.

28. McCullers JA, Hayden FG. Fatal influenza B infections: time to reexamine influenza research priorities. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(6):870-872.

Grand Rounds: Man, 62, With New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation

A 62-year-old black nursing home resident was transported to the hospital emergency department with fever of 102°F, new-onset atrial fibrillation (A-fib), and dementia. His medical history was significant for hypertension and multiple strokes.

His inpatient work-up for A-fib and dementia revealed a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level below 0.005 µIU/mL (normal range, 0.3 to 3.0 µIU/mL). Results of thyroid function testing (TFT) revealed a triiodothyronine (T3) level within normal range but a free thyroxine (T4) level of 2.9 ng/dL (normal range, 0.7 to 1.5 ng/dL) and a total T4 of 17.8 µg/dL (normal, 4.5 to 12.0 µg/dL). The abnormal TSH and T4 levels were considered suggestive of a thyrotoxic state, warranting an endocrinology consult. Cardiology was consulted regarding new-onset A-fib.

During history taking, the patient denied any shortness of breath, cough, palpitations, heat intolerance, anxiety, tremors, insomnia, dysphagia, diarrhea, dysuria, weight loss, or recent ingestion of iodine-containing medications or supplements.

On examination, the patient was febrile, with a blood pressure of 106/71 mm Hg; pulse, 74 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 98% to 99% on room air. ECG showed a normal sinus rhythm and a ventricular rate of 64 beats/min.

The patient's weight was 58.9 kg, and his height, 63" (BMI, 22.8). The patient had no skin changes, and his mucous membranes were slightly moist. The patient's head was atraumatic and normocephalic. His extraocular movements were intact, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light, with nonicteric sclera. There was no proptosis or ophthalmoplegia. The patient's neck was supple, with no jugular venous distension, tracheal deviation, or thyromegaly.

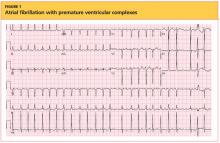

The cardiovascular exam revealed an irregular heartbeat, and repeat ECG showed A-fib with a ventricular rate of 151 beats/min (see Figure 1). The patient's chest was clear, with no wheezing or rhonchi. The abdomen was soft and slightly obese, and bowel sounds were present. The neurologic examination revealed no hyperreflexia. The patient's mental status was altered at times and he was alert, awake, and oriented to others. His speech was slightly slow, and some left-sided weakness was noted.

As recommended during the endocrinology consult, the patient underwent an I-123 sodium iodide thyroid scan, which showed faint uptake at the base of the neck, slightly to the left of midline; and a 24-hour radioactive iodide uptake (RAIU), which measured 2.8% (normal range, 8% to 35%).

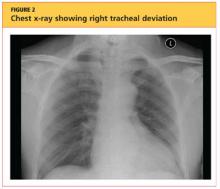

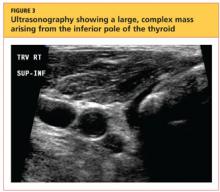

The patient's chest X-ray showed a right tracheal deviation not previously noted on physical examination (see Figure 2); the possible cause of a thyroid mass was considered. Subsequent ultrasonography of the thyroid revealed generally normal dimensions and parenchymal echogenicity. However, a large complex mass was detected, arising from the inferior pole of the thyroid and displacing the trachea toward the right (see Figure 3). According to the radiologist's notes, the mass contained both solid and cystic elements, scattered calcifications, and foci of flow on color Doppler. It measured about 6 cm in the largest (transverse) dimension. A 2.0-mm nodule was noted in the isthmus, slightly to the right of midline, consistent with multinodular goiter.

Following the cardiology consult, a diltiazem drip was initiated, but the patient was later optimized on flecainide for rhythm control and metoprolol for rate control. He was also initially anticoagulated using a heparin drip and bridged to warfarin, with target international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 3.0. Echocardiography revealed normal systolic function with ejection fraction of 55%, left ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 35 mm Hg, and no pericardial effusions or valvular disease.

Regarding the patient's unexplained fever, results of chest imaging were negative for signs of pneumonia or atelectasis, which might have suggested a pulmonary cause. Urinalysis results were normal. Complete blood count showed no leukocytosis. The patient's fever subsided within 48 hours.

The differential diagnosis included Graves' disease, toxic multinodular goiter, Jod-Basedow syndrome, and subacute thyroiditis.

Graves' disease, an autoimmune disease with an unknown trigger, is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. In affected patients, the thyroid gland overproduces thyroid hormones, leading to thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis can result in multiple clinical signs and symptoms, including Graves' ophthalmopathy, pretibial myxedema, and goiter; TFT results typically include elevated T3 and T4 and low TSH.1-5 In the case patient (who had no history of thyroid disease, nor clinical signs or symptoms of Graves' disease), low uptake of iodine on thyroid scan precluded this diagnosis.

Toxic multinodular goiter, the second most common cause of hyperthyroidism, can be responsible for A-fib, tachycardia, and congestive heart failure.6,7 Iodine deficiency causes enlargement of the thyroid gland, where numerous nodules can develop, as seen in the case patient. These nodules can function independently, sometimes producing excess thyroid hormone; this leads to hyperplasia of the thyroid gland, resulting in a nontoxic multinodular goiter. From this goiter, a toxic multinodular goiter can emerge insidiously. However, in this condition, RAIU typically exceeds 30%; in the case patient, low 24-hour RAIU (2.8%) and the absence of functioning nodules on scanning made it possible to rule out this diagnosis.

Jod-Basedow syndrome refers to hyperthyroidism that develops as a result of administration of iodide, either as a dietary supplement or as IV contrast medium, or as an adverse effect of the antiarrhythmic drug amiodarone. This phenomenon is usually seen in a patient with endemic goiter.8-11 The relatively limited nature of the case patient's goiter and absence of a precipitating exposure to iodine made this diagnosis highly unlikely.

Subacute thyroiditis is a condition to which the patient's abnormal TFT results could reasonably be attributed. The patient had a substernal multinodular goiter that could not be palpated on physical examination, but it was visualized in the extended lower neck during thyroid scintigraphy.3 RAIU was minimal—a typical finding in this disorder,6 as TSH is suppressed by leakage of the excessive amounts of thyroid hormone. A tentative diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was made.

As subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting disorder, the patient was not started on any medications for hyperthyroidism but was advised to follow up with his primary care provider or an endocrinologist for repeat TFT and for fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the large thyroid nodule (a complex mass, containing cystic elements and calcifications, with a potential for malignancy) to rule out thyroid cancer.

Repeat ECG before discharge showed normal sinus rhythm with a ventricular rate of 74 beats/min. The patient was alert, awake, and oriented at discharge. He was continued on flecainide, metoprolol, and warfarin and advised to follow up with his primary care provider regarding his target INR.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of subacute thyroiditis, according to findings reported in 2003 from the Rochester Epidemiology Project in Olmsted County, Minnesota,12 is 12.1 cases per 100,000/year, with a higher incidence in women than men. It is most common in young adults and decreases with advancing age. Coxsackie virus, adenovirus, mumps, echovirus, influenza, and Epstein-Barr virus have been implicated in the disorder.12,13

Subacute thyroiditis is associated with a triphasic clinical course of hyperthyroidism, then hypothyroidism, then a return to normal thyroid function—as was seen in the case patient. Onset of subacute thyroiditis has been associated with recent viral infection, which may serve as a precipitant. The cause of this patient's high fever was never identified; thus, the etiology may have been viral.

The initial high thyroid hormone levels result from inflammation of thyroid tissue and release of preformed thyroid hormone into the circulation.6 At this point, TSH is suppressed and patients have very low RAIU, as was true in the case patient.

The condition is self-limiting and does not require treatment in the majority of patients, as TFT results return to normal levels within about two months.6 Patients can appear extremely ill due to thyrotoxicosis from subacute thyroiditis, but this usually lasts no longer than six to eight weeks.3 Subacute thyroiditis can be associated with atrial arrhythmia or heart failure.14,15

PATIENT OUTCOME

New-onset A-fib was attributed to the patient's thyrotoxicosis, which in turn was caused by subacute thyroiditis. He had a multinodular goiter, although he had not received any iodine supplements or IV contrast. As in most cases of subacute thyroiditis, no precipitating event was identified. However, given this patient's residence in a nursing facility and presentation with a high fever with no identifiable cause, a viral etiology for his subacute thyroiditis is possible.6

The patient's dementia may have been secondary to acute thyrotoxicosis, as his mental state improved during the hospital stay. His vitamin B12, folate, and A1C levels were within normal range. CT of the head showed multiple chronic infarcts and cerebral atrophy, and MRI of the brain indicated microvascular ischemic disease.

The patient was readmitted one month later for an episode of near-syncope (which, it was concluded, was a vasovagal episode). At that time, his TSH was found normal at 1.350 µIU/mL. Flecainide and metoprolol were discontinued; he was started on diltiazem for continued rate and rhythm control (as recommended by cardiology) and continued on warfarin.

CONCLUSION

In this case, subacute thyroiditis was most likely caused by a viral infection that led to destruction of the normal thyroid follicles and release of their preformed thyroid hormone into the circulation; this in turn led to sudden-onset A-fib. The diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was suggested based on the abnormalities seen in this patient's TFT results, coupled with the suppressed RAIU—a typical finding in this disease.

Because subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting condition, there is no role for antithyroid medication. Instead, treatment should be focused on relieving the patient's symptoms, such as ß-blockade or calcium channel blockers for tachycardia and corticosteroids or NSAIDs for neck pain.

REFERENCES

1. Weetman AP. Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(17):1236-1248.

2. Delgado Hurtado JJ, Pineda M. Images in medicine: Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364(20):1955.

3. Al-Sharif AA, Abujbara MA, Chiacchio S, et al. Contribution of radioiodine uptake measurement and thyroid scintigraphy to the differential diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis. Hell J Nucl Med. 2010;13(2):132-137.

4. Buccelletti F, Carroccia A, Marsiliani D, et al. Utility of routine thyroid-stimulating hormone determination in new-onset atrial fibrillation in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(9):1158-1162.

5. Ross DS. Radioiodine therapy for hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):542-550.

6. Bahn RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(3):456-520.

7. Erickson D, Gharib H, Li H, van Heerden JA. Treatment of patients with toxic multinodular goiter. Thyroid. 1998;8(4):277-282.

8. Basaria S, Cooper DS. Amiodarone and the thyroid. Am J Med. 2005;118(7):706-714.

9. Bogazzi F, Bartalena L, Martino E. Approach to the patient with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2529-2535.

10. El-Shirbiny AM, Stavrou SS, Dnistrian A, et al. Jod-Basedow syndrome following oral iodine and radioiodinated-antibody administration. J Nucl Med. 1997;38(11):1816-1817.

11. Stanbury JB, Ermans AE, Bourdoux P, et al. Iodine-induced hyperthyroidism: occurrence and epidemiology. Thyroid. 1998;8(1):83-100.

12. Fatourechi V, Aniszewski JP, Fatourechi GZ, et al. Clinical features and outcome of subacute thyroiditis in an incidence cohort: Olmsted County, Minnesota, study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(5):2100-2105.

13. Golden SH, Robinson KA, Saldanha I, et al. Clinical review: prevalence and incidence of endocrine and metabolic disorders in the United States: a comprehensive review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(6):1853-1878.

14. Volpé R. The management of subacute (DeQuervain's) thyroiditis. Thyroid. 1993;3(3):253-255.

15. Lee SL. Subacute thyroiditis (2009). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/125648-overview. Accessed April 17, 2012.

A 62-year-old black nursing home resident was transported to the hospital emergency department with fever of 102°F, new-onset atrial fibrillation (A-fib), and dementia. His medical history was significant for hypertension and multiple strokes.

His inpatient work-up for A-fib and dementia revealed a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level below 0.005 µIU/mL (normal range, 0.3 to 3.0 µIU/mL). Results of thyroid function testing (TFT) revealed a triiodothyronine (T3) level within normal range but a free thyroxine (T4) level of 2.9 ng/dL (normal range, 0.7 to 1.5 ng/dL) and a total T4 of 17.8 µg/dL (normal, 4.5 to 12.0 µg/dL). The abnormal TSH and T4 levels were considered suggestive of a thyrotoxic state, warranting an endocrinology consult. Cardiology was consulted regarding new-onset A-fib.

During history taking, the patient denied any shortness of breath, cough, palpitations, heat intolerance, anxiety, tremors, insomnia, dysphagia, diarrhea, dysuria, weight loss, or recent ingestion of iodine-containing medications or supplements.

On examination, the patient was febrile, with a blood pressure of 106/71 mm Hg; pulse, 74 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 98% to 99% on room air. ECG showed a normal sinus rhythm and a ventricular rate of 64 beats/min.

The patient's weight was 58.9 kg, and his height, 63" (BMI, 22.8). The patient had no skin changes, and his mucous membranes were slightly moist. The patient's head was atraumatic and normocephalic. His extraocular movements were intact, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light, with nonicteric sclera. There was no proptosis or ophthalmoplegia. The patient's neck was supple, with no jugular venous distension, tracheal deviation, or thyromegaly.

The cardiovascular exam revealed an irregular heartbeat, and repeat ECG showed A-fib with a ventricular rate of 151 beats/min (see Figure 1). The patient's chest was clear, with no wheezing or rhonchi. The abdomen was soft and slightly obese, and bowel sounds were present. The neurologic examination revealed no hyperreflexia. The patient's mental status was altered at times and he was alert, awake, and oriented to others. His speech was slightly slow, and some left-sided weakness was noted.

As recommended during the endocrinology consult, the patient underwent an I-123 sodium iodide thyroid scan, which showed faint uptake at the base of the neck, slightly to the left of midline; and a 24-hour radioactive iodide uptake (RAIU), which measured 2.8% (normal range, 8% to 35%).

The patient's chest X-ray showed a right tracheal deviation not previously noted on physical examination (see Figure 2); the possible cause of a thyroid mass was considered. Subsequent ultrasonography of the thyroid revealed generally normal dimensions and parenchymal echogenicity. However, a large complex mass was detected, arising from the inferior pole of the thyroid and displacing the trachea toward the right (see Figure 3). According to the radiologist's notes, the mass contained both solid and cystic elements, scattered calcifications, and foci of flow on color Doppler. It measured about 6 cm in the largest (transverse) dimension. A 2.0-mm nodule was noted in the isthmus, slightly to the right of midline, consistent with multinodular goiter.

Following the cardiology consult, a diltiazem drip was initiated, but the patient was later optimized on flecainide for rhythm control and metoprolol for rate control. He was also initially anticoagulated using a heparin drip and bridged to warfarin, with target international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 3.0. Echocardiography revealed normal systolic function with ejection fraction of 55%, left ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 35 mm Hg, and no pericardial effusions or valvular disease.

Regarding the patient's unexplained fever, results of chest imaging were negative for signs of pneumonia or atelectasis, which might have suggested a pulmonary cause. Urinalysis results were normal. Complete blood count showed no leukocytosis. The patient's fever subsided within 48 hours.

The differential diagnosis included Graves' disease, toxic multinodular goiter, Jod-Basedow syndrome, and subacute thyroiditis.

Graves' disease, an autoimmune disease with an unknown trigger, is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. In affected patients, the thyroid gland overproduces thyroid hormones, leading to thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis can result in multiple clinical signs and symptoms, including Graves' ophthalmopathy, pretibial myxedema, and goiter; TFT results typically include elevated T3 and T4 and low TSH.1-5 In the case patient (who had no history of thyroid disease, nor clinical signs or symptoms of Graves' disease), low uptake of iodine on thyroid scan precluded this diagnosis.

Toxic multinodular goiter, the second most common cause of hyperthyroidism, can be responsible for A-fib, tachycardia, and congestive heart failure.6,7 Iodine deficiency causes enlargement of the thyroid gland, where numerous nodules can develop, as seen in the case patient. These nodules can function independently, sometimes producing excess thyroid hormone; this leads to hyperplasia of the thyroid gland, resulting in a nontoxic multinodular goiter. From this goiter, a toxic multinodular goiter can emerge insidiously. However, in this condition, RAIU typically exceeds 30%; in the case patient, low 24-hour RAIU (2.8%) and the absence of functioning nodules on scanning made it possible to rule out this diagnosis.

Jod-Basedow syndrome refers to hyperthyroidism that develops as a result of administration of iodide, either as a dietary supplement or as IV contrast medium, or as an adverse effect of the antiarrhythmic drug amiodarone. This phenomenon is usually seen in a patient with endemic goiter.8-11 The relatively limited nature of the case patient's goiter and absence of a precipitating exposure to iodine made this diagnosis highly unlikely.

Subacute thyroiditis is a condition to which the patient's abnormal TFT results could reasonably be attributed. The patient had a substernal multinodular goiter that could not be palpated on physical examination, but it was visualized in the extended lower neck during thyroid scintigraphy.3 RAIU was minimal—a typical finding in this disorder,6 as TSH is suppressed by leakage of the excessive amounts of thyroid hormone. A tentative diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was made.

As subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting disorder, the patient was not started on any medications for hyperthyroidism but was advised to follow up with his primary care provider or an endocrinologist for repeat TFT and for fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the large thyroid nodule (a complex mass, containing cystic elements and calcifications, with a potential for malignancy) to rule out thyroid cancer.

Repeat ECG before discharge showed normal sinus rhythm with a ventricular rate of 74 beats/min. The patient was alert, awake, and oriented at discharge. He was continued on flecainide, metoprolol, and warfarin and advised to follow up with his primary care provider regarding his target INR.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of subacute thyroiditis, according to findings reported in 2003 from the Rochester Epidemiology Project in Olmsted County, Minnesota,12 is 12.1 cases per 100,000/year, with a higher incidence in women than men. It is most common in young adults and decreases with advancing age. Coxsackie virus, adenovirus, mumps, echovirus, influenza, and Epstein-Barr virus have been implicated in the disorder.12,13

Subacute thyroiditis is associated with a triphasic clinical course of hyperthyroidism, then hypothyroidism, then a return to normal thyroid function—as was seen in the case patient. Onset of subacute thyroiditis has been associated with recent viral infection, which may serve as a precipitant. The cause of this patient's high fever was never identified; thus, the etiology may have been viral.

The initial high thyroid hormone levels result from inflammation of thyroid tissue and release of preformed thyroid hormone into the circulation.6 At this point, TSH is suppressed and patients have very low RAIU, as was true in the case patient.

The condition is self-limiting and does not require treatment in the majority of patients, as TFT results return to normal levels within about two months.6 Patients can appear extremely ill due to thyrotoxicosis from subacute thyroiditis, but this usually lasts no longer than six to eight weeks.3 Subacute thyroiditis can be associated with atrial arrhythmia or heart failure.14,15

PATIENT OUTCOME

New-onset A-fib was attributed to the patient's thyrotoxicosis, which in turn was caused by subacute thyroiditis. He had a multinodular goiter, although he had not received any iodine supplements or IV contrast. As in most cases of subacute thyroiditis, no precipitating event was identified. However, given this patient's residence in a nursing facility and presentation with a high fever with no identifiable cause, a viral etiology for his subacute thyroiditis is possible.6

The patient's dementia may have been secondary to acute thyrotoxicosis, as his mental state improved during the hospital stay. His vitamin B12, folate, and A1C levels were within normal range. CT of the head showed multiple chronic infarcts and cerebral atrophy, and MRI of the brain indicated microvascular ischemic disease.

The patient was readmitted one month later for an episode of near-syncope (which, it was concluded, was a vasovagal episode). At that time, his TSH was found normal at 1.350 µIU/mL. Flecainide and metoprolol were discontinued; he was started on diltiazem for continued rate and rhythm control (as recommended by cardiology) and continued on warfarin.

CONCLUSION

In this case, subacute thyroiditis was most likely caused by a viral infection that led to destruction of the normal thyroid follicles and release of their preformed thyroid hormone into the circulation; this in turn led to sudden-onset A-fib. The diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was suggested based on the abnormalities seen in this patient's TFT results, coupled with the suppressed RAIU—a typical finding in this disease.

Because subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting condition, there is no role for antithyroid medication. Instead, treatment should be focused on relieving the patient's symptoms, such as ß-blockade or calcium channel blockers for tachycardia and corticosteroids or NSAIDs for neck pain.

REFERENCES

1. Weetman AP. Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(17):1236-1248.

2. Delgado Hurtado JJ, Pineda M. Images in medicine: Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364(20):1955.

3. Al-Sharif AA, Abujbara MA, Chiacchio S, et al. Contribution of radioiodine uptake measurement and thyroid scintigraphy to the differential diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis. Hell J Nucl Med. 2010;13(2):132-137.

4. Buccelletti F, Carroccia A, Marsiliani D, et al. Utility of routine thyroid-stimulating hormone determination in new-onset atrial fibrillation in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(9):1158-1162.

5. Ross DS. Radioiodine therapy for hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):542-550.

6. Bahn RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(3):456-520.

7. Erickson D, Gharib H, Li H, van Heerden JA. Treatment of patients with toxic multinodular goiter. Thyroid. 1998;8(4):277-282.

8. Basaria S, Cooper DS. Amiodarone and the thyroid. Am J Med. 2005;118(7):706-714.

9. Bogazzi F, Bartalena L, Martino E. Approach to the patient with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2529-2535.

10. El-Shirbiny AM, Stavrou SS, Dnistrian A, et al. Jod-Basedow syndrome following oral iodine and radioiodinated-antibody administration. J Nucl Med. 1997;38(11):1816-1817.

11. Stanbury JB, Ermans AE, Bourdoux P, et al. Iodine-induced hyperthyroidism: occurrence and epidemiology. Thyroid. 1998;8(1):83-100.

12. Fatourechi V, Aniszewski JP, Fatourechi GZ, et al. Clinical features and outcome of subacute thyroiditis in an incidence cohort: Olmsted County, Minnesota, study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(5):2100-2105.

13. Golden SH, Robinson KA, Saldanha I, et al. Clinical review: prevalence and incidence of endocrine and metabolic disorders in the United States: a comprehensive review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(6):1853-1878.

14. Volpé R. The management of subacute (DeQuervain's) thyroiditis. Thyroid. 1993;3(3):253-255.

15. Lee SL. Subacute thyroiditis (2009). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/125648-overview. Accessed April 17, 2012.

A 62-year-old black nursing home resident was transported to the hospital emergency department with fever of 102°F, new-onset atrial fibrillation (A-fib), and dementia. His medical history was significant for hypertension and multiple strokes.

His inpatient work-up for A-fib and dementia revealed a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level below 0.005 µIU/mL (normal range, 0.3 to 3.0 µIU/mL). Results of thyroid function testing (TFT) revealed a triiodothyronine (T3) level within normal range but a free thyroxine (T4) level of 2.9 ng/dL (normal range, 0.7 to 1.5 ng/dL) and a total T4 of 17.8 µg/dL (normal, 4.5 to 12.0 µg/dL). The abnormal TSH and T4 levels were considered suggestive of a thyrotoxic state, warranting an endocrinology consult. Cardiology was consulted regarding new-onset A-fib.

During history taking, the patient denied any shortness of breath, cough, palpitations, heat intolerance, anxiety, tremors, insomnia, dysphagia, diarrhea, dysuria, weight loss, or recent ingestion of iodine-containing medications or supplements.

On examination, the patient was febrile, with a blood pressure of 106/71 mm Hg; pulse, 74 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 98% to 99% on room air. ECG showed a normal sinus rhythm and a ventricular rate of 64 beats/min.

The patient's weight was 58.9 kg, and his height, 63" (BMI, 22.8). The patient had no skin changes, and his mucous membranes were slightly moist. The patient's head was atraumatic and normocephalic. His extraocular movements were intact, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light, with nonicteric sclera. There was no proptosis or ophthalmoplegia. The patient's neck was supple, with no jugular venous distension, tracheal deviation, or thyromegaly.

The cardiovascular exam revealed an irregular heartbeat, and repeat ECG showed A-fib with a ventricular rate of 151 beats/min (see Figure 1). The patient's chest was clear, with no wheezing or rhonchi. The abdomen was soft and slightly obese, and bowel sounds were present. The neurologic examination revealed no hyperreflexia. The patient's mental status was altered at times and he was alert, awake, and oriented to others. His speech was slightly slow, and some left-sided weakness was noted.

As recommended during the endocrinology consult, the patient underwent an I-123 sodium iodide thyroid scan, which showed faint uptake at the base of the neck, slightly to the left of midline; and a 24-hour radioactive iodide uptake (RAIU), which measured 2.8% (normal range, 8% to 35%).

The patient's chest X-ray showed a right tracheal deviation not previously noted on physical examination (see Figure 2); the possible cause of a thyroid mass was considered. Subsequent ultrasonography of the thyroid revealed generally normal dimensions and parenchymal echogenicity. However, a large complex mass was detected, arising from the inferior pole of the thyroid and displacing the trachea toward the right (see Figure 3). According to the radiologist's notes, the mass contained both solid and cystic elements, scattered calcifications, and foci of flow on color Doppler. It measured about 6 cm in the largest (transverse) dimension. A 2.0-mm nodule was noted in the isthmus, slightly to the right of midline, consistent with multinodular goiter.

Following the cardiology consult, a diltiazem drip was initiated, but the patient was later optimized on flecainide for rhythm control and metoprolol for rate control. He was also initially anticoagulated using a heparin drip and bridged to warfarin, with target international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 3.0. Echocardiography revealed normal systolic function with ejection fraction of 55%, left ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 35 mm Hg, and no pericardial effusions or valvular disease.

Regarding the patient's unexplained fever, results of chest imaging were negative for signs of pneumonia or atelectasis, which might have suggested a pulmonary cause. Urinalysis results were normal. Complete blood count showed no leukocytosis. The patient's fever subsided within 48 hours.

The differential diagnosis included Graves' disease, toxic multinodular goiter, Jod-Basedow syndrome, and subacute thyroiditis.

Graves' disease, an autoimmune disease with an unknown trigger, is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. In affected patients, the thyroid gland overproduces thyroid hormones, leading to thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis can result in multiple clinical signs and symptoms, including Graves' ophthalmopathy, pretibial myxedema, and goiter; TFT results typically include elevated T3 and T4 and low TSH.1-5 In the case patient (who had no history of thyroid disease, nor clinical signs or symptoms of Graves' disease), low uptake of iodine on thyroid scan precluded this diagnosis.

Toxic multinodular goiter, the second most common cause of hyperthyroidism, can be responsible for A-fib, tachycardia, and congestive heart failure.6,7 Iodine deficiency causes enlargement of the thyroid gland, where numerous nodules can develop, as seen in the case patient. These nodules can function independently, sometimes producing excess thyroid hormone; this leads to hyperplasia of the thyroid gland, resulting in a nontoxic multinodular goiter. From this goiter, a toxic multinodular goiter can emerge insidiously. However, in this condition, RAIU typically exceeds 30%; in the case patient, low 24-hour RAIU (2.8%) and the absence of functioning nodules on scanning made it possible to rule out this diagnosis.

Jod-Basedow syndrome refers to hyperthyroidism that develops as a result of administration of iodide, either as a dietary supplement or as IV contrast medium, or as an adverse effect of the antiarrhythmic drug amiodarone. This phenomenon is usually seen in a patient with endemic goiter.8-11 The relatively limited nature of the case patient's goiter and absence of a precipitating exposure to iodine made this diagnosis highly unlikely.

Subacute thyroiditis is a condition to which the patient's abnormal TFT results could reasonably be attributed. The patient had a substernal multinodular goiter that could not be palpated on physical examination, but it was visualized in the extended lower neck during thyroid scintigraphy.3 RAIU was minimal—a typical finding in this disorder,6 as TSH is suppressed by leakage of the excessive amounts of thyroid hormone. A tentative diagnosis of subacute thyroiditis was made.

As subacute thyroiditis is a self-limiting disorder, the patient was not started on any medications for hyperthyroidism but was advised to follow up with his primary care provider or an endocrinologist for repeat TFT and for fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the large thyroid nodule (a complex mass, containing cystic elements and calcifications, with a potential for malignancy) to rule out thyroid cancer.

Repeat ECG before discharge showed normal sinus rhythm with a ventricular rate of 74 beats/min. The patient was alert, awake, and oriented at discharge. He was continued on flecainide, metoprolol, and warfarin and advised to follow up with his primary care provider regarding his target INR.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of subacute thyroiditis, according to findings reported in 2003 from the Rochester Epidemiology Project in Olmsted County, Minnesota,12 is 12.1 cases per 100,000/year, with a higher incidence in women than men. It is most common in young adults and decreases with advancing age. Coxsackie virus, adenovirus, mumps, echovirus, influenza, and Epstein-Barr virus have been implicated in the disorder.12,13

Subacute thyroiditis is associated with a triphasic clinical course of hyperthyroidism, then hypothyroidism, then a return to normal thyroid function—as was seen in the case patient. Onset of subacute thyroiditis has been associated with recent viral infection, which may serve as a precipitant. The cause of this patient's high fever was never identified; thus, the etiology may have been viral.