User login

In late 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sofosbuvir and simeprevir, the newest direct-acting antiviral agents for treating chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Multiple clinical trials have demonstrated dramatically improved treatment outcomes with these agents, opening the door to all-oral regimens or interferon-free regimens as the future standard of care for HCV.

In this article, we discuss the results of the trials that established the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir and simeprevir and led to their FDA approval. We also summarize the importance of these agents and evaluate other direct-acting antivirals currently in the pipeline for HCV treatment.

HCV IS A RISING PROBLEM

Chronic HCV infection is a major clinical and public health problem, with the estimated number of people infected exceeding 170 million worldwide, including 3.2 million in the United States.1 It is a leading cause of cirrhosis, and its complications include hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure. Cirrhosis due to HCV remains the leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States, accounting for nearly 40% of liver transplants in adults.2

The clinical impact of HCV will only continue to escalate, and in parallel, so will the cost to society. Models suggest that HCV-related deaths will double between 2010 and 2019, and considering only direct medical costs, the projected financial burden of treating HCV-related disease during this interval is estimated at between $6.5 and $13.6 billion.3

AN RNA VIRUS WITH SIX GENOTYPES

HCV, first identified in 1989, is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA flavivirus of the Hepacivirus genus measuring 50 to 60 nm in diameter.4 There are six viral genotypes, with genotype 1 being the most common in the United States and traditionally the most difficult to treat.

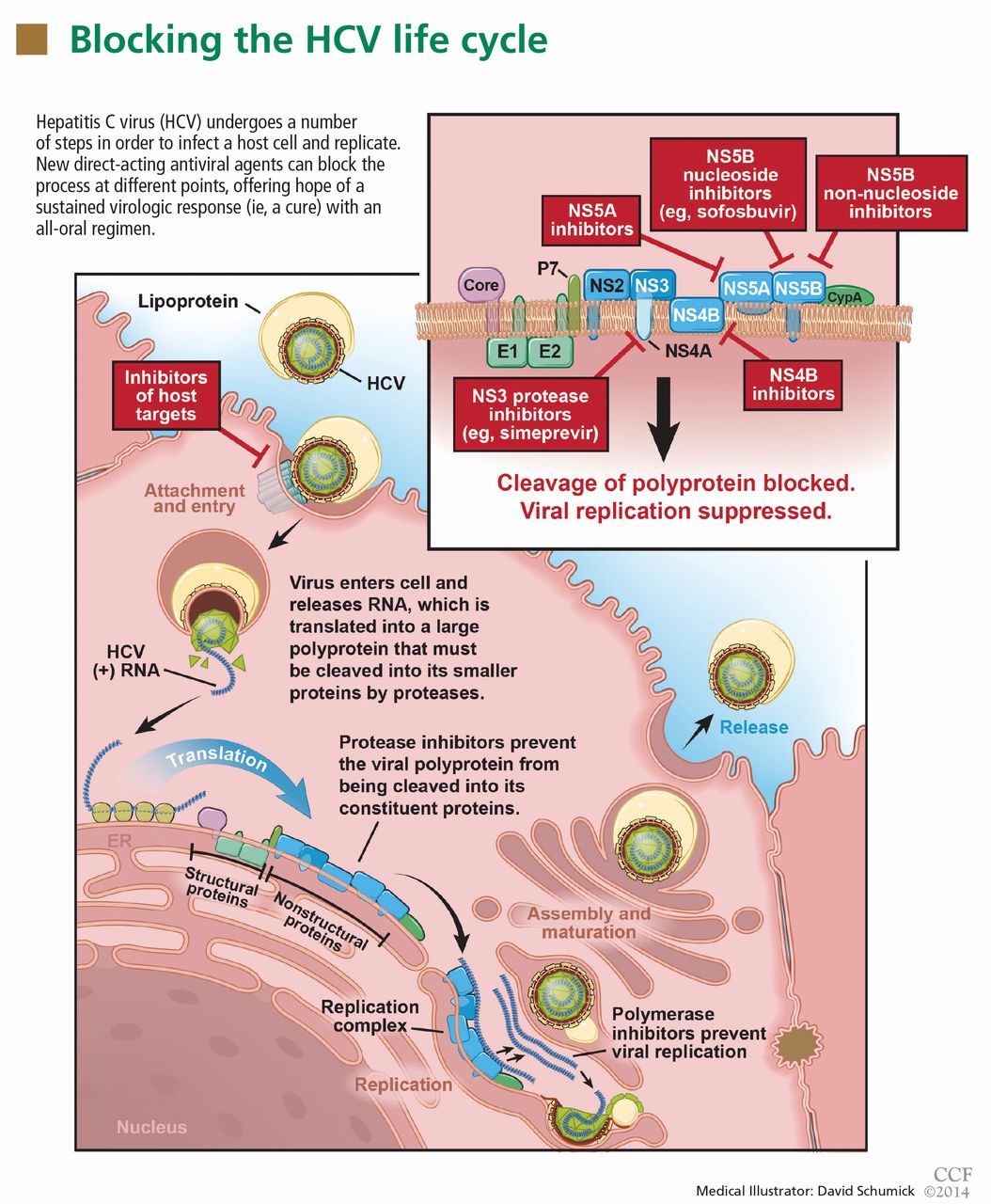

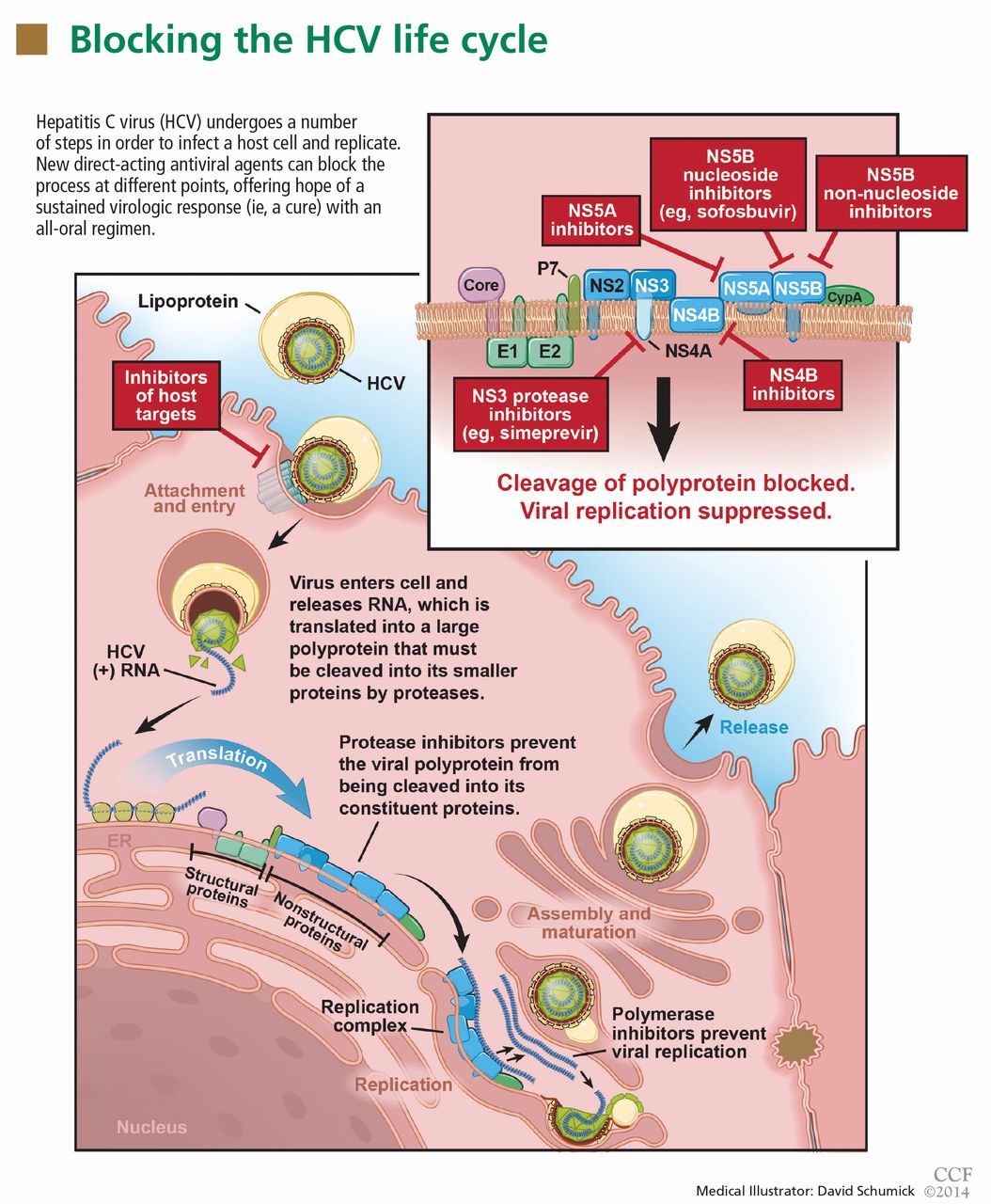

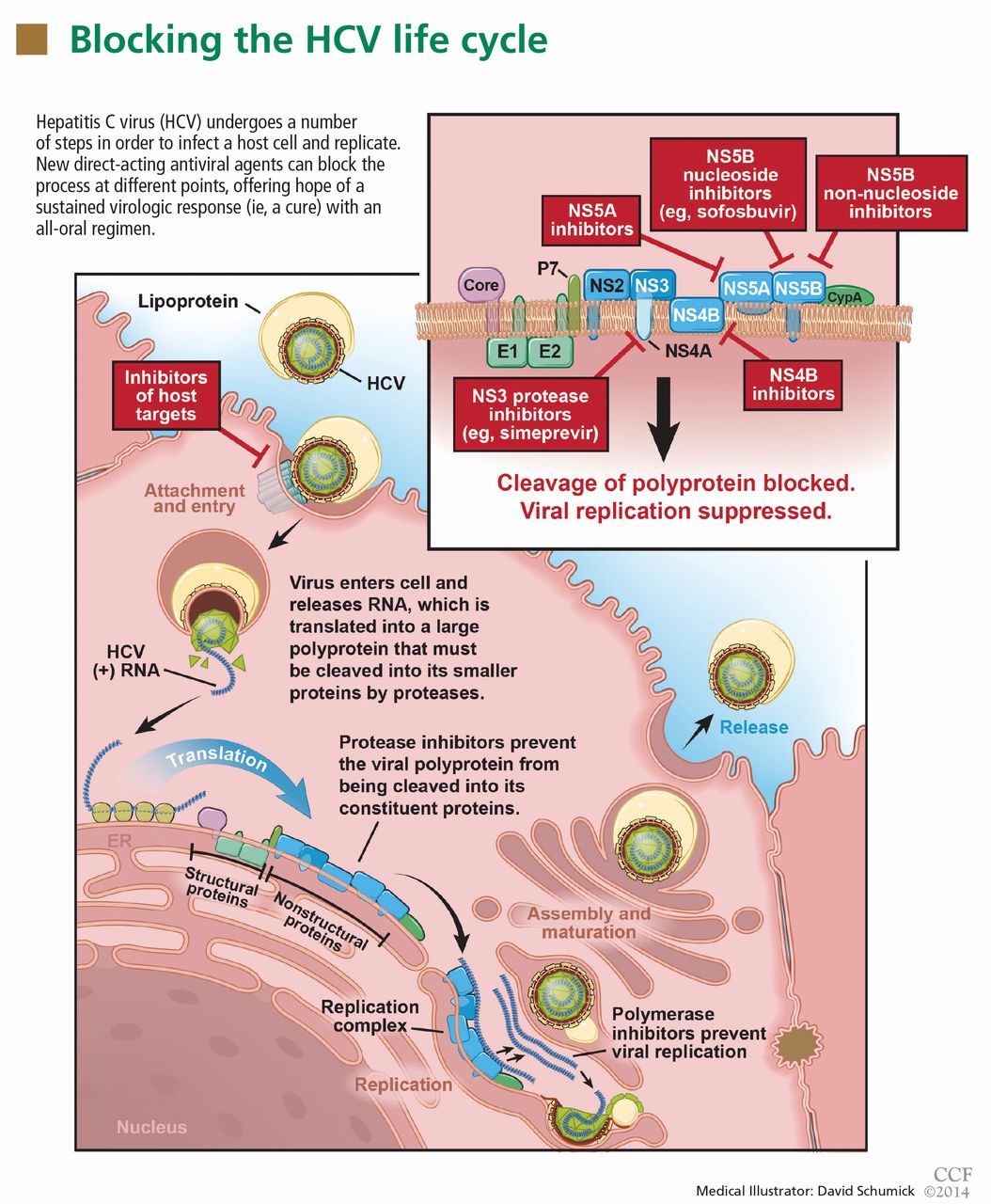

Once inside the host cell, the virus releases its RNA strand, which is translated into a single polyprotein of about 3,000 amino acids. This large molecule is then cleaved by proteases into several domains: three structural proteins (C, E1, and E2), a small protein called p7, and six nonstructural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B) (Figure 1).5 These nonstructural proteins enable the virus to replicate.

GOAL OF TREATING HCV: A SUSTAINED VIROLOGIC RESPONSE

The aim of HCV treatment is to achieve a sustained virologic response, defined as having no detectable viral RNA after completion of antiviral therapy. This is associated with substantially better clinical outcomes, lower rates of liver-related morbidity and all-cause mortality, and stabilization of or even improvement in liver histology.6,7 This end point has traditionally been assessed at 6 months after the end of therapy, but recent data suggest the rates at 12 weeks are essentially equivalent.

Table 1 summarizes the patterns of virologic response in treating HCV infection.

Interferon plus ribavirin: The standard of care for many years

HCV treatment has evolved over the past 20 years. Before 2011, the standard of care was a combination of interferon alfa-polyethylene glycol (peg-interferon), given as a weekly injection, and oral ribavirin. Neither drug has specific antiviral activity, and when they are used together they result in a sustained virologic response in fewer than 50% of patients with HCV genotype 1 and, at best, in 70% to 80% of patients with other genotypes.8

Nearly all patients receiving interferon experience side effects, which can be serious. Fatigue and flu-like symptoms are common, and the drug can also cause psychiatric symptoms (including depression or psychosis), weight loss, seizures, peripheral neuropathy, and bone marrow suppression. Ribavirin causes hemolysis and skin complications and is teratogenic.9

An important bit of information to know when using interferon is the patient’s IL28B genotype. This refers to a single-nucleotide polymorphism (C or T) on chromosome 19q13 (rs12979860) upstream of the IL28B gene encoding for interferon lambda-3. It is strongly associated with responsiveness to interferon: patients with the IL28B CC genotype have a much better chance of a sustained virologic response with interferon than do patients with CT or TT.

Boceprevir and telaprevir: First-generation protease inhibitors

In May 2011, the FDA approved the NS3/4A protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir for treating HCV genotype 1, marking the beginning of the era of direct-acting antiviral agents.10 When these drugs are used in combination with peg-interferon alfa and ribavirin, up to 75% of patients with HCV genotype 1 who have had no previous treatment achieve a sustained virologic response.

But despite greatly improving the response rate, these first-generation protease inhibitors have substantial limitations. Twenty-five percent of patients with HCV genotype 1 who have received no previous treatment and 71% of patients who did not respond to previous treatment will not achieve a sustained virologic response with these agents.11 Further, they are effective only against HCV genotype 1, being highly specific for the amino acid target sequence of the NS3 region.

Also, they must be used in combination with interferon alfa and ribavirin because the virus needs to mutate only a little—a few amino-acid substitutions—to gain resistance to them.12 Therefore, patients are still exposed to interferon and ribavirin, with their toxicity. In addition, dysgeusia is seen with boceprevir, rash with telaprevir, and anemia with both.13,14

Finally, serious drug-drug interactions prompted the FDA to impose warnings for the use of these agents with other medications that interact with CYP3A4, the principal enzyme responsible for their metabolism. Thus, these significant adverse effects dampen the enthusiasm of patients contemplating a long course of treatment with these agents.

The need to improve the rate of sustained virologic response, shorten the duration of treatment, avoid serious side effects, improve efficacy in treating patients infected with genotypes other than 1, and, importantly, eliminate the need for interferon alfa and its serious adverse effects have driven the development of new direct-acting antiviral agents, including the two newly FDA-approved drugs, sofosbuvir and simeprevir.

SOFOSBUVIR: A POLYMERASE INHIBITOR

Sofosbuvir is a uridine nucleotide analogue that selectively inhibits the HCV NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Figure 1). It targets the highly conserved nucleotide-binding pocket of this enzyme and functions as a chain terminator.15 While the protease inhibitors are genotype-dependent, inhibition of the highly conserved viral polymerase has an impact that spans genotypes.

Early clinical trials of sofosbuvir

Sofosbuvir has been tested in combination with interferon alfa and ribavirin, as well as in interferon-free regimens (Table 2).16–20

Rodriguez-Torres et al,15

- 56% with sofosbuvir 100 mg, peg-interferon, and ribavirin

- 83% with sofosbuvir 200 mg, peg-interferon, and ribavirin

- 80% with sofosbuvir 400 mg, peg-interferon, and ribavirin

- 43% with peg-interferon and ribavirin alone.

The ATOMIC trial16 tested the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir in combination with peg-interferon and ribavirin in patients with HCV genotype 1, 4, or 6, without cirrhosis, who had not received any previous treatment. Patients with HCV genotype 1 were randomized to three treatments:

- Sofosbuvir 400 mg orally once daily plus peg-interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks

- The same regimen, but for 24 weeks

- Sofosbuvir plus peg-interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks, followed by 12 weeks of either sofosbuvir monotherapy or sofosbuvir plus ribavirin.

The rates of sustained virologic response were very high and were not significantly different among the three groups: 89%, 89%, and 87%, respectively. Patients who were able to complete a full course of therapy achieved even higher rates of sustained virologic response, ranging from 96% to 98%. The likelihood of response was not adversely affected by the usual markers of a poorer prognosis, such as a high viral load (≥ 800,000 IU/mL) or a non-CC IL28B genotype. Although patients with cirrhosis (another predictor of no response) were excluded from this study, the presence of bridging fibrosis did not seem to affect the rate of sustained virologic response. The results in patients with genotypes other than 1 were very encouraging, but the small number of patients enrolled precluded drawing firm conclusions in this group.

Important implications of the ATOMIC trial include the following:

There is no benefit in prolonging treatment with sofosbuvir beyond 12 weeks, since adverse events increased without any improvement in the rate of sustained virologic response.

There is a very low likelihood of developing viral resistance or mutation when using sofosbuvir.

There is no role for response-guided therapy, a concept used with protease inhibitor-based regimens in which patients who have complete clearance of the virus within the first 4 weeks of treatment (a rapid virologic response) and remain clear through 12 weeks of treatment (an extended rapid viral response) can be treated for a shorter duration without decreasing the likelihood of a sustained virologic response.

Lawitz et al17 conducted a randomized double-blind phase 2 trial to evaluate the effect of sofosbuvir dosing on response in noncirrhotic, previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1, 2, or 3. Patients with HCV genotype 1 were randomized to one of three treatment groups in a 2:2:1 ratio: sofosbuvir 200 mg orally once daily, sofosbuvir 400 mg orally once daily, or placebo, all for 12 weeks in combination with peg-interferon (180 μg weekly) and ribavirin in a dosage based on weight. Depending on the viral response, patients continued peg-interferon and ribavirin for an additional 12 weeks if they achieved an extended rapid viral response, or 36 weeks if they did not achieve an extended rapid virologic response, and in all patients who received placebo. Patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3 were given sofosbuvir 400 mg once daily in combination with interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks.

As in the ATOMIC trial, all patients treated with sofosbuvir had a very rapid reduction in viral load: 98% of patients with genotype 1 developed a rapid virologic response, and therefore almost all were eligible for the shorter treatment course of 24 weeks.17 The latter finding again suggested that response-guided treatment is not relevant with sofosbuvir-based regimens.

Very high rates of sustained virologic response were seen: 90% in patients with genotype 1 treated with sofosbuvir 200 mg, 91% in those with genotype 1 treated with 400 mg, and 92% in those with genotype 2 or 3. Although 6% of patients in the 200-mg group had virologic breakthrough after completing sofosbuvir treatment, no virologic breakthrough was observed in the 400-mg group, suggesting that the 400-mg dose might suppress the virus more effectively.17

The ELECTRON trial18 was a phase 2 study designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir and ribavirin in interferon-sparing and interferon-free regimens in patients with HCV genotype 1, 2, or 3 infection. Sofosbuvir was tested with peg-interferon and ribavirin, with ribavirin alone, and as monotherapy in previously untreated patients with genotype 2 or 3. A small number of patients with genotype 1 who were previously untreated and who were previously nonresponders were also treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin.

All patients had a rapid virologic response, and viral suppression was sustained through the end of treatment. All patients with genotype 2 or 3 treated with double therapy (sofosbuvir and ribavirin) or triple therapy (sofosbuvir, peg-interferon, and ribavirin) achieved a sustained virologic response, compared with only 60% of patients treated with sofosbuvir monotherapy. The monotherapy group had an equal number of relapsers among those with genotype 2 or 3. Of the genotype 1 patients treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin, 84% of those previously untreated developed a sustained virologic response, whereas only 10% of the previous nonresponders did.

Phase 3 clinical trials of sofosbuvir

The NEUTRINO trial19 studied the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir in previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1, 4, 5, or 6. In this phase 3 open-label study, all patients received sofosbuvir plus peg-interferon and weight-based ribavirin therapy for 12 weeks. Of the patients enrolled, 89% had genotype 1, while 9% had genotype 4 and 2% had genotype 5 or 6. Overall, 17% of the patients had cirrhosis.

The viral load rapidly decreased in all patients treated with sofosbuvir irrespective of the HCV genotype, IL28B status, race, or the presence or absence of cirrhosis. Ninety-nine percent of patients with genotype 1, 4, 5, or 6 achieved a rapid virologic response, and 90% achieved a sustained virologic response at 12 weeks after completion of treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin. Patients with cirrhosis had a slightly lower rate of sustained virologic response (80%, compared with 92% in patients without cirrhosis). Also, patients with non-CC IL28B genotypes had a lower rate of sustained virologic response (87% in non-CC allele vs 98% in patients with the favorable CC allele).

The FISSION trial19 recruited previously untreated patients with genotype 2 or 3 and randomized them to therapy with either sofosbuvir plus ribavirin in a weight-based dose for 12 weeks, or 24 weeks of interferon and ribavirin. In this study, 20% of patients in each treatment group had cirrhosis.

As in the NEUTRINO trial, the viral load rapidly decreased in all patients treated with sofosbuvir irrespective of HCV genotype, IL28B status, race, or the presence or absence of cirrhosis. Here, 100% of patients with genotype 2 or 3 who were treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin achieved a rapid virologic response. Differences in outcome emerged based on genotype: 97% of those with genotype 2 and 56% of those with genotype 3 achieved a sustained virologic response. The overall rate was 67%, which was not different from patients treated with peg-interferon and ribavirin. In the subgroup of patients with cirrhosis, 47% of those treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin achieved a sustained virologic response, vs 38% of those who received peg-interferon plus ribavirin.

In both the NEUTRINO and FISSION trials, few patients discontinued treatment, with higher rates of most adverse events occurring in patients treated with peg-interferon and ribavirin.

POSITRON,20 a phase 3 clinical trial, tested sofosbuvir in patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3 who were ineligible for peg-interferon, unwilling to take peg-interferon, or unable to tolerate peg-interferon (mainly because of clinically significant psychiatric disorders). Patients were randomized to two treatment groups for 12 weeks: sofosbuvir plus ribavirin, or placebo. About 50% of patients had HCV genotype 3, and 16% had cirrhosis.

The overall rate of sustained virologic response at 12 weeks after treatment was 78% in the sofosbuvir-and-ribavirin group (93% in genotype 2 patients and 61% in genotype 3 patients). Again, cirrhosis was associated with a lower rate of sustained virologic response (61% of patients with cirrhosis achieved a sustained virologic response vs 81% of patients without cirrhosis). None of the sofosbuvir-treated patients had virologic failure while on treatment.

FUSION,20 another phase 3 trial, evaluated sofosbuvir in patients infected with HCV genotype 2 or 3 for whom interferon-based treatment had failed. They were randomized to either 12 weeks or 16 weeks of sofosbuvir and weight-based ribavirin treatment. About 60% of patients had HCV genotype 3, and 34% had cirrhosis.

The overall sustained virologic response rate was 50% in the patients treated for 12 weeks and 73% in those treated for 16 weeks: specifically, 86% of patients with genotype 2 achieved a sustained virologic response at 12 weeks and 94% at 16 weeks, whereas in those with genotype 3 the rates were 30% at 12 weeks and 62% at 16 weeks.

Cirrhosis was again a predictor of lack of response to sofosbuvir. In the group treated for 12 weeks, 31% of those with cirrhosis achieved a sustained virologic response compared with 61% in those without cirrhosis. In the group treated for 16 weeks, 61% of those with cirrhosis achieved a sustained virologic response compared with 76% in those without cirrhosis.

In both the POSITRON and FUSION trials, relapse accounted for all treatment failures, and no virologic resistance was detected in patients who did not have a sustained virologic response. The investigators concluded that 12 weeks of treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin can be effective for HCV genotype 2 infection, but extending the treatment to 16 weeks may be beneficial for genotype 3. This may be especially important in patients with cirrhosis or those who did not have a response to peg-interferon-based treatment.

VALENCE,21 an ongoing phase 3 trial in Europe, is assessing the safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir 400 mg once daily and weight-based ribavirin in patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3. Eighty-five percent of the trial participants have received previous treatment, and 21% have cirrhosis. Patients were originally randomized in a 4:1 ratio to receive sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for 12 weeks or matching placebo, but as a result of emerging data suggesting that patients with genotype 3 would benefit from more than 12 weeks of treatment, the study was subsequently amended to extend treatment to 24 weeks for patients with genotype 3.

Overall rates of sustained virologic response were 93% in patients with genotype 2 and 85% in patients with genotype 3. In previously treated patients with genotype 2 who were treated for 12 weeks, the rates of sustained virologic response were 91% in those without cirrhosis vs 88% in those with cirrhosis. In previously treated patients with genotype 3, the rates in those treated for 24 weeks were 87% in patients without cirrhosis vs 60% with cirrhosis. The safety profile was consistent with that of ribavirin.

Side effects of sofosbuvir

In clinical trials, side effects occurred most often when sofosbuvir was combined with interferon and ribavirin and were consistent with the known side effects of the latter two agents. The most frequently reported side effects included fatigue, insomnia, nausea, rash, anemia, headache, and arthralgia, with most of these adverse events rated by treating clinicians as being mild in severity.15,20

In the ATOMIC trial, the most common events leading to drug discontinuation were anemia and neutropenia, both associated with interferon and ribavirin. Patients receiving sofosbuvir monotherapy after 12 weeks of triple therapy showed rapid improvement in hemoglobin levels and neutrophil counts, indicating that hematologic abnormalities attributed solely to sofosbuvir are minimal. In the FISSION trial, the incidence of adverse events was consistently lower in those receiving sofosbuvir-ribavirin than in patients receiving interferon-ribavirin without sofosbuvir.19

In the POSITRON trial, discontinuation of sofosbuvir because of adverse events was uncommon, and there were no differences in the incidence of adverse events and laboratory abnormalities between patients with and without cirrhosis when they received sofosbuvir and ribavirin.20

Sofosbuvir dosage and indications

Sofosbuvir is approved in an oral dose of 400 mg once daily in combination with ribavirin for patients infected with HCV genotype 2 or 3 and in combination with ribavirin and interferon alfa in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4 (Table 3). It could be considered for HCV genotype 1 in combination with ribavirin alone for 24 weeks in patients who are ineligible for interferon.

Sofosbuvir is also recommended in combination with ribavirin in HCV-infected patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who are awaiting liver transplantation, for up to 48 weeks or until they receive a transplant, to prevent posttransplant reinfection with HCV.

Sofosbuvir is expensive

A course of therapy is expected to cost about $84,000, which is significantly more than the cost of previous triple therapy (peg-interferon, ribavirin, and either boceprevir or telaprevir).22 This high cost will undoubtedly lead to less widespread use in developing countries, and potentially even in the United States. As newer direct-acting antiviral agents become available, the price will likely come down, enhancing access to these drugs.

SIMEPREVIR: A SECOND-GENERATION PROTEASE INHIBITOR

Telaprevir and boceprevir are NS3/A4 protease inhibitors that belong to the alfa-ketoamid derivative class. Simeprevir belongs to the macrocyclic class and has a different way of binding to the target enzyme.23 Like sofosbuvir, simeprevir was recently approved by the FDA for the treatment of HCV genotype 1.

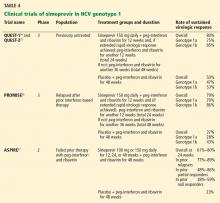

The therapeutic efficacy of simeprevir has been tested in several clinical trials (Table 4), including QUEST-124 and QUEST-225 (in previously untreated patients), PROMISE26 (in prior relapsers), and ASPIRE27 (in prior partial and null responders). Results from these trials showed high overall rates of sustained virologic response with triple therapy (ie, simeprevir combined with peg-interferon and ribavirin). It was generally well tolerated, and most adverse events reported during 12 weeks of treatment were of mild to moderate severity.

In QUEST-1 and QUEST-2, both double-blind phase 3 clinical trials, previously untreated patients infected with HCV genotype 1 were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either simeprevir 150 mg daily or placebo for 12 weeks; both groups also received peg-interferon and ribavirin. Patients then received peg-interferon and ribavirin alone for 12 or 36 weeks in the simeprevir group (based on response) and for 36 weeks in the placebo group.

The overall rate of sustained virologic response at 12 weeks was 80% in the simeprevir group (75% in those with genotype 1a and 85% in those with genotype 1b) vs 50% in the placebo group (receiving peg-interferon and ribavirin alone).24,25

PROMISE,26 another double-blind randomized phase 3 clinical trial, evaluated simeprevir in patients with HCV genotype 1 who relapsed after previous interferon-based therapy. It had a similar design to QUEST-1 and QUEST-2, and 15% of all patients had cirrhosis.

The overall sustained virologic response rate at 12 weeks after treatment was 79% in the simeprevir group (70% in patients with genotype 1a and 86% in those with genotype 1b) vs 37% in the placebo group. Rates were similar in patients with absent to moderate fibrosis (82%), advanced fibrosis (73%), or cirrhosis (74%).

ASPIRE.27 Simeprevir efficacy in patients with HCV genotype 1 for whom previous therapy with peg-interferon and ribavirin had failed was tested in ASPIRE, a double-blind randomized phase 2 clinical trial. Patients were randomized to receive simeprevir (either 100 mg or 150 mg daily) for 12, 24, or 48 weeks in combination with 48 weeks of peg-interferon and ribavirin, or placebo plus peg-interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks.

The primary end point was the rate of sustained virologic response at 24 weeks. Overall, rates were 61% to 80% for the simeprevir treatment groups compared with 23% with placebo, regardless of prior response to peg-interferon and ribavirin. By subgroup, rates were:

- 77% to 89% with simeprevir vs 37% with placebo in prior relapsers

- 48% to 86% with simeprevir vs 9% with placebo in prior partial responders

- 38% to 59% with placebo vs 19% for prior nonresponders.

The best rates of sustained viral response at 24 weeks were in the groups that received simeprevir 150 mg daily: 85% in prior relapsers, 75% in prior partial responders, and 51% in prior nonresponders.

Simeprevir vs other direct-acting antiviral drugs

Advantages of simeprevir over the earlier protease inhibitors include once-daily dosing, a lower rate of adverse events (the most common being fatigue, headache, rash, photosensitivity, and pruritus), a lower likelihood of discontinuation because of adverse events, and fewer drug-drug interactions (since it is a weak inhibitor of the CYP3A4 enzyme).

Unlike sofosbuvir, simeprevir was FDA-approved only for HCV genotype 1 and in combination with interferon alfa and ribavirin. Compared with sofosbuvir, the treatment duration with simeprevir regimens is longer overall (interferon alfa and ribavirin are given for 12 weeks in sofosbuvir-based regimens vs 24 to 48 weeks with simeprevir). As with sofosbuvir, the estimated cost of simeprevir is high, about $66,000 for a 12-week course.

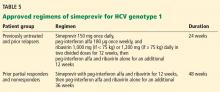

Simeprevir dosage and indications

Simeprevir was approved at an oral dose of 150 mg once daily in combination with ribavirin and interferon alfa in patients with HCV genotype 1 (Table 5).

The approved regimens for simeprevir are fixed in total duration based on the patient’s treatment history. Specifically, all patients receive the drug in combination with peg-interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks. Then, previously untreated patients and prior relapsers continue to receive peg-interferon and ribavirin alone for another 12 weeks, and those with a partial or null response continue with these drugs for another 36 weeks.

Patients infected with HCV genotype 1a should be screened for the NS3 Q80K polymorphism at baseline, as it has been associated with substantially reduced response to simeprevir.

Sofosbuvir and simeprevir in combination

The COSMOS trial.28 Given their differences in mechanism of action, sofosbuvir and simeprevir are being tested in combination. The COSMOS trial is an ongoing phase 2 randomized open-label study investigating the efficacy and safety of simeprevir and sofosbuvir in combination with and without ribavirin in patients with HCV genotype 1, including nonresponders and those with cirrhosis. Early results are promising, with very high rates of sustained virologic response with the sofosbuvir-simeprevir combination (93% to 100%) and indicate that the addition of ribavirin might not be needed to achieve sustained virologic response in this patient population.

THE FUTURE

The emergence of all-oral regimens for HCV treatment with increasingly sophisticated agents such as sofosbuvir and simeprevir will dramatically alter the management of HCV patients. In view of the improvement in sustained virologic response rates with these treatments, and since most HCV-infected persons have no symptoms, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention29 recently recommended one-time testing of the cohort in which the prevalence of HCV infection is highest: all persons born between 1945 and 1965. This undoubtedly will increase the detection of this infection—and the number of new patients expecting treatment.

Future drugs promise further improvements (Table 6).30–35 Advances in knowledge of the HCV molecular structure have led to the development of numerous direct-acting antiviral agents with very specific viral targets. A second wave of protease inhibitors and of nucleoside and nonnucleoside polymerase inhibitors will soon be available. Inhibitors of NS5A (a protein important in the assembly of the viral replication complex) such as daclatasvir and ledipasvir, are currently in phase 3 clinical trials. Other viral proteins involved in assembly of the virus, including the core protein and p7, are being explored as drug targets. In addition, inhibiting host targets such as cyclophilin A and miR122 has gained traction recently, with specific agents currently in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials.

Factors that previously were major determinants of response to treatment, such as IL28B genotype, viral load, race, age, extent of fibrosis, and genotype 1 subtypes, will become much less important with the introduction of highly potent direct-acting antiviral agents.

Many all-oral combinations are being evaluated in clinical trials. For example, the open-label, phase 2 LONESTAR trial tested the utility of combining sofosbuvir and ledipasvir (an NS5A inhibitor) with and without ribavirin for 8 or 12 weeks in previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1, and for 12 weeks in patients with HCV genotype 1 who did not achieve a sustained virologic response after receiving a protease inhibitor-based regimen (half of whom had compensated cirrhosis).36 Sustained virologic response rates were very high (95% to 100%) in both previously treated and previously untreated patients, including those with cirrhosis. Similar rates were achieved by the 8-week and 12-week groups in noncirrhotic patients who had not been previously treated for HCV. The typical hematologic abnormalities associated with interferon were not observed except for mild anemia in patients who received ribavirin. These results suggest that the combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir could offer a very effective, short, all-oral treatment for patients with HCV genotype 1, including those with cirrhosis, who up to now have been difficult to treat.

Challenges remaining

The success of sofosbuvir and simeprevir paves the way for interferon-free regimens.37 For a long time, the treatment of HCV infection required close monitoring of patients while managing the side effects of interferon, but the current and emerging direct-acting antiviral agents will soon change this practice. Given the synergistic effects of combination therapy—targeting the virus at multiple locations, decreasing the likelihood of drug resistance, and improving efficacy—combination regimens seem to be the optimal solution to the HCV epidemic. Lower risk of side effects and shorter treatment duration will definitely improve the acceptance of any new regimen. New agents that act against conserved viral targets, thereby yielding activity across multiple genotypes, will be advantageous as well. Table 7 compares the rates of sustained virologic response of the different currently approved HCV treatment regimens.

Clinical challenges remain, including the management of special patient populations for whom data are still limited. These include patients with cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, renal failure, and concurrent infection with human immunodeficiency virus, and patients who have undergone solid organ transplantation. Clinical trials are under way to evaluate the treatment options for these patients, who will likely need to wait for the emergence of additional agents before dramatic improvement in sustained virologic response rates may be expected.38

As the treatment of HCV becomes simpler, safer, and more effective, primary care physicians will increasingly be expected to manage it. Difficult-to-treat patients, including the special populations above, will require specialist management and individualized treatment regimens, at least until better therapies are available. The high projected cost of the new agents may limit access, at least initially. However, the dramatic improvement in sustained virologic response rates and all that that implies in terms of decreased risk of advanced liver disease and its complications will undoubtedly make these therapies cost-effective.39

- Averhoff FM, Glass N, Holtzman D. Global burden of hepatitis C: considerations for healthcare providers in the united states. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55(suppl 1):S10–S15.

- Wiesner RH, Sorrell M, Villamil F; International Liver Transplantation Society Expert Panel. Report of the first international liver transplantation society expert panel consensus conference on liver transplantation and hepatitis C. Liver Transplant 2003; 9:S1–S9.

- Wong JB, McQuillan GM, McHutchison JG, Poynard T. Estimating future hepatitis C morbidity, mortality, and costs in the United States. Am J Public Health 2000; 90:1562–1569.

- Pawlotsky JM, Chevaliez S, McHutchison JG. The hepatitis C virus life cycle as a target for new antiviral therapies. Gastroenterology 2007; 132:1979–1998.

- Bartenschlager R, Lohmann V. Replication of hepatitis C virus. J Gen Virol 2000; 81:1631–1648.

- Singal AG, Volk ML, Jensen D, Di Bisceglie AM, Schoenfeld PS. A sustained viral response is associated with reduced liver-related morbidity and mortality in patients with hepatitis C virus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 8:280–288,288.e1.

- Camma C, Di Bona D, Schepis F, et al. Effect of peginterferon alfa-2a on liver histology in chronic hepatitis C: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Hepatology 2004; 39:333–342.

- Paeshuyse J, Dallmeier K, Neyts J. Ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a review of the proposed mechanisms of action. Curr Opin Virol 2011; 1:590–598.

- Thomas E, Ghany MG, Liang TJ. The application and mechanism of action of ribavirin in therapy of hepatitis C. Antivir Chem Chemother 2012; 23:1–12.

- Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB; American Association for Study of Liver Diseases. An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2011; 54:1433–1444.

- Soriano V, Vispo E, Poveda E, Labarga P, Barreiro P. Treatment failure with new hepatitis C drugs. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2012; 13:313–323.

- Asselah T, Marcellin P. Interferon free therapy with direct acting antivirals for HCV. Liver Int 2013; 33(suppl 1):93–104.

- Manns MP, McCone J, Davis MN, et al. Overall safety profile of boceprevir plus peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1: a combined analysis of 3 phase 2/3 clinical trials. Liver Int 2013; Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/liv.12300. [Epub ahead of print]

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2405–2416.

- Rodriguez-Torres M, Lawitz E, Kowdley KV, et al. Sofosbuvir (GS-7977) plus peginterferon/ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with HCV genotype 1: a randomized, 28-day, dose-ranging trial. J Hepatol 2013; 58:663–668.

- Kowdley KV, Lawitz E, Crespo I, et al. Sofosbuvir with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for treatment-naive patients with hepatitis C genotype-1 infection (ATOMIC): an open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet 2013; 381:2100–2107.

- Lawitz E, Lalezari JP, Hassanein T, et al. Sofosbuvir in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for non-cirrhotic, treatment-naive patients with genotypes 1, 2, and 3 hepatitis C infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:401–408.

- Gane EJ, Stedman CA, Hyland RH, et al. Nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:34–44.

- Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1878–1887.

- Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV, et al. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1867–1877.

- Zeuzem S, Dusheiko G, Salupere R, et al. Sofosbuvir + ribavirin for 12 or 24 weeks for patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3: the VALENCE trial [abstract no.1085]. 64th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; November 1–5, 2013; Washington, DC.

- Soriano V, Vispo E, de Mendoza C, et al. Hepatitis C therapy with HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitors. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2013; 14:1161–1170.

- You DM, Pockros PJ. Simeprevir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2013; 14:2581–2589.

- Jacobson IM, Dore GJ, Foster G, et al. Simeprevir (TMC435) with peginterferon/ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype-1 infection in treatment-naive patients: results from Quest-1, a phase III trial [abstract no. 1425]. Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver; April 24–28, 2013; Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Manns M, Marcellin P, Poordad FP, et al. Simeprevir (TMC435) with peginterferon/ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype-1 infection in treatment-naïve patients: results from QUEST-2, a phase III trial [abstract no. 1413]. Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver; April 24–28, 2013; Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Lawitz E, Forns X, Zeuzem S, et al. Simeprevir (TMC435) with peginterferon/ribavirin for treatment of chronic HCV genotype 1 infection in patients who relapsed after previous interferon-based therapy: results from promise, a phase III trial [abstract no. 869b]. Digestive Disease Week; May 18–21, 2013; Orlando, FL.

- Zeuzem S, Berg T, Gane E, et al. Simeprevir increases rate of sustained virologic response among treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotype-1 infection: a phase IIb trial. Gastroenterology epub Oct 31, 2013.

- Jacobson IM, Ghalib RM, Rodriguez-Torres M, et al. SVR results of a once-daily regimen of simeprevir (TMC435) plus sofosbuvir (GS-7977) with or without ribavirin in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic HCV genotype 1 treatment-naive and prior null responder patients: the COSMOS study [abstract LB-3]. 64th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; November 1–5, 2013; Washington, DC.

- Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep 2012; 61( RR-4):1–32.

- Sulkowski MS, Kang M, Matining R, et al. Safety and antiviral activity of the HCV entry inhibitor ITX5061 in treatment-naive HCV-infected adults: a randomized, double-blind, phase 1b study. J Infect Dis 2013 Oct 9. [Epub ahead of print]

- Pawlotsky JM. NS5A inhibitors in the treatment of hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2013; 59:375–382.

- Yu M, Corsa AC, Xu S, et al. In vitro efficacy of approved and experimental antivirals against novel genotype 3 hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicons. Antiviral Res 2013; 100:439–445.

- Aghemo A, De Francesco R. New horizons in hepatitis C antiviral therapy with direct-acting antivirals. Hepatology 2013; 58:428–438.

- Liang TJ, Ghany MG. Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1907–1917.

- Flisiak R, Jaroszewicz J, Parfieniuk-Kowerda A. Emerging treatments for hepatitis C. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2013; 18:461–475.

- Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, et al. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2013 Nov 1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62121-2 [Epub ahead of print]

- Drenth JP. HCV treatment—no more room for interferonologists? N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1931–1932.

- Casey LC, Lee WM. Hepatitis C virus therapy update 2013. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2013; 29:243–249.

- Afdhal NH, Zeuzem S, Schooley RT, et al. The new paradigm of hepatitis C therapy: integration of oral therapies into best practices. J Viral Hepatol 2013; 20:745–760.

In late 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sofosbuvir and simeprevir, the newest direct-acting antiviral agents for treating chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Multiple clinical trials have demonstrated dramatically improved treatment outcomes with these agents, opening the door to all-oral regimens or interferon-free regimens as the future standard of care for HCV.

In this article, we discuss the results of the trials that established the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir and simeprevir and led to their FDA approval. We also summarize the importance of these agents and evaluate other direct-acting antivirals currently in the pipeline for HCV treatment.

HCV IS A RISING PROBLEM

Chronic HCV infection is a major clinical and public health problem, with the estimated number of people infected exceeding 170 million worldwide, including 3.2 million in the United States.1 It is a leading cause of cirrhosis, and its complications include hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure. Cirrhosis due to HCV remains the leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States, accounting for nearly 40% of liver transplants in adults.2

The clinical impact of HCV will only continue to escalate, and in parallel, so will the cost to society. Models suggest that HCV-related deaths will double between 2010 and 2019, and considering only direct medical costs, the projected financial burden of treating HCV-related disease during this interval is estimated at between $6.5 and $13.6 billion.3

AN RNA VIRUS WITH SIX GENOTYPES

HCV, first identified in 1989, is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA flavivirus of the Hepacivirus genus measuring 50 to 60 nm in diameter.4 There are six viral genotypes, with genotype 1 being the most common in the United States and traditionally the most difficult to treat.

Once inside the host cell, the virus releases its RNA strand, which is translated into a single polyprotein of about 3,000 amino acids. This large molecule is then cleaved by proteases into several domains: three structural proteins (C, E1, and E2), a small protein called p7, and six nonstructural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B) (Figure 1).5 These nonstructural proteins enable the virus to replicate.

GOAL OF TREATING HCV: A SUSTAINED VIROLOGIC RESPONSE

The aim of HCV treatment is to achieve a sustained virologic response, defined as having no detectable viral RNA after completion of antiviral therapy. This is associated with substantially better clinical outcomes, lower rates of liver-related morbidity and all-cause mortality, and stabilization of or even improvement in liver histology.6,7 This end point has traditionally been assessed at 6 months after the end of therapy, but recent data suggest the rates at 12 weeks are essentially equivalent.

Table 1 summarizes the patterns of virologic response in treating HCV infection.

Interferon plus ribavirin: The standard of care for many years

HCV treatment has evolved over the past 20 years. Before 2011, the standard of care was a combination of interferon alfa-polyethylene glycol (peg-interferon), given as a weekly injection, and oral ribavirin. Neither drug has specific antiviral activity, and when they are used together they result in a sustained virologic response in fewer than 50% of patients with HCV genotype 1 and, at best, in 70% to 80% of patients with other genotypes.8

Nearly all patients receiving interferon experience side effects, which can be serious. Fatigue and flu-like symptoms are common, and the drug can also cause psychiatric symptoms (including depression or psychosis), weight loss, seizures, peripheral neuropathy, and bone marrow suppression. Ribavirin causes hemolysis and skin complications and is teratogenic.9

An important bit of information to know when using interferon is the patient’s IL28B genotype. This refers to a single-nucleotide polymorphism (C or T) on chromosome 19q13 (rs12979860) upstream of the IL28B gene encoding for interferon lambda-3. It is strongly associated with responsiveness to interferon: patients with the IL28B CC genotype have a much better chance of a sustained virologic response with interferon than do patients with CT or TT.

Boceprevir and telaprevir: First-generation protease inhibitors

In May 2011, the FDA approved the NS3/4A protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir for treating HCV genotype 1, marking the beginning of the era of direct-acting antiviral agents.10 When these drugs are used in combination with peg-interferon alfa and ribavirin, up to 75% of patients with HCV genotype 1 who have had no previous treatment achieve a sustained virologic response.

But despite greatly improving the response rate, these first-generation protease inhibitors have substantial limitations. Twenty-five percent of patients with HCV genotype 1 who have received no previous treatment and 71% of patients who did not respond to previous treatment will not achieve a sustained virologic response with these agents.11 Further, they are effective only against HCV genotype 1, being highly specific for the amino acid target sequence of the NS3 region.

Also, they must be used in combination with interferon alfa and ribavirin because the virus needs to mutate only a little—a few amino-acid substitutions—to gain resistance to them.12 Therefore, patients are still exposed to interferon and ribavirin, with their toxicity. In addition, dysgeusia is seen with boceprevir, rash with telaprevir, and anemia with both.13,14

Finally, serious drug-drug interactions prompted the FDA to impose warnings for the use of these agents with other medications that interact with CYP3A4, the principal enzyme responsible for their metabolism. Thus, these significant adverse effects dampen the enthusiasm of patients contemplating a long course of treatment with these agents.

The need to improve the rate of sustained virologic response, shorten the duration of treatment, avoid serious side effects, improve efficacy in treating patients infected with genotypes other than 1, and, importantly, eliminate the need for interferon alfa and its serious adverse effects have driven the development of new direct-acting antiviral agents, including the two newly FDA-approved drugs, sofosbuvir and simeprevir.

SOFOSBUVIR: A POLYMERASE INHIBITOR

Sofosbuvir is a uridine nucleotide analogue that selectively inhibits the HCV NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Figure 1). It targets the highly conserved nucleotide-binding pocket of this enzyme and functions as a chain terminator.15 While the protease inhibitors are genotype-dependent, inhibition of the highly conserved viral polymerase has an impact that spans genotypes.

Early clinical trials of sofosbuvir

Sofosbuvir has been tested in combination with interferon alfa and ribavirin, as well as in interferon-free regimens (Table 2).16–20

Rodriguez-Torres et al,15

- 56% with sofosbuvir 100 mg, peg-interferon, and ribavirin

- 83% with sofosbuvir 200 mg, peg-interferon, and ribavirin

- 80% with sofosbuvir 400 mg, peg-interferon, and ribavirin

- 43% with peg-interferon and ribavirin alone.

The ATOMIC trial16 tested the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir in combination with peg-interferon and ribavirin in patients with HCV genotype 1, 4, or 6, without cirrhosis, who had not received any previous treatment. Patients with HCV genotype 1 were randomized to three treatments:

- Sofosbuvir 400 mg orally once daily plus peg-interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks

- The same regimen, but for 24 weeks

- Sofosbuvir plus peg-interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks, followed by 12 weeks of either sofosbuvir monotherapy or sofosbuvir plus ribavirin.

The rates of sustained virologic response were very high and were not significantly different among the three groups: 89%, 89%, and 87%, respectively. Patients who were able to complete a full course of therapy achieved even higher rates of sustained virologic response, ranging from 96% to 98%. The likelihood of response was not adversely affected by the usual markers of a poorer prognosis, such as a high viral load (≥ 800,000 IU/mL) or a non-CC IL28B genotype. Although patients with cirrhosis (another predictor of no response) were excluded from this study, the presence of bridging fibrosis did not seem to affect the rate of sustained virologic response. The results in patients with genotypes other than 1 were very encouraging, but the small number of patients enrolled precluded drawing firm conclusions in this group.

Important implications of the ATOMIC trial include the following:

There is no benefit in prolonging treatment with sofosbuvir beyond 12 weeks, since adverse events increased without any improvement in the rate of sustained virologic response.

There is a very low likelihood of developing viral resistance or mutation when using sofosbuvir.

There is no role for response-guided therapy, a concept used with protease inhibitor-based regimens in which patients who have complete clearance of the virus within the first 4 weeks of treatment (a rapid virologic response) and remain clear through 12 weeks of treatment (an extended rapid viral response) can be treated for a shorter duration without decreasing the likelihood of a sustained virologic response.

Lawitz et al17 conducted a randomized double-blind phase 2 trial to evaluate the effect of sofosbuvir dosing on response in noncirrhotic, previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1, 2, or 3. Patients with HCV genotype 1 were randomized to one of three treatment groups in a 2:2:1 ratio: sofosbuvir 200 mg orally once daily, sofosbuvir 400 mg orally once daily, or placebo, all for 12 weeks in combination with peg-interferon (180 μg weekly) and ribavirin in a dosage based on weight. Depending on the viral response, patients continued peg-interferon and ribavirin for an additional 12 weeks if they achieved an extended rapid viral response, or 36 weeks if they did not achieve an extended rapid virologic response, and in all patients who received placebo. Patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3 were given sofosbuvir 400 mg once daily in combination with interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks.

As in the ATOMIC trial, all patients treated with sofosbuvir had a very rapid reduction in viral load: 98% of patients with genotype 1 developed a rapid virologic response, and therefore almost all were eligible for the shorter treatment course of 24 weeks.17 The latter finding again suggested that response-guided treatment is not relevant with sofosbuvir-based regimens.

Very high rates of sustained virologic response were seen: 90% in patients with genotype 1 treated with sofosbuvir 200 mg, 91% in those with genotype 1 treated with 400 mg, and 92% in those with genotype 2 or 3. Although 6% of patients in the 200-mg group had virologic breakthrough after completing sofosbuvir treatment, no virologic breakthrough was observed in the 400-mg group, suggesting that the 400-mg dose might suppress the virus more effectively.17

The ELECTRON trial18 was a phase 2 study designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir and ribavirin in interferon-sparing and interferon-free regimens in patients with HCV genotype 1, 2, or 3 infection. Sofosbuvir was tested with peg-interferon and ribavirin, with ribavirin alone, and as monotherapy in previously untreated patients with genotype 2 or 3. A small number of patients with genotype 1 who were previously untreated and who were previously nonresponders were also treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin.

All patients had a rapid virologic response, and viral suppression was sustained through the end of treatment. All patients with genotype 2 or 3 treated with double therapy (sofosbuvir and ribavirin) or triple therapy (sofosbuvir, peg-interferon, and ribavirin) achieved a sustained virologic response, compared with only 60% of patients treated with sofosbuvir monotherapy. The monotherapy group had an equal number of relapsers among those with genotype 2 or 3. Of the genotype 1 patients treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin, 84% of those previously untreated developed a sustained virologic response, whereas only 10% of the previous nonresponders did.

Phase 3 clinical trials of sofosbuvir

The NEUTRINO trial19 studied the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir in previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1, 4, 5, or 6. In this phase 3 open-label study, all patients received sofosbuvir plus peg-interferon and weight-based ribavirin therapy for 12 weeks. Of the patients enrolled, 89% had genotype 1, while 9% had genotype 4 and 2% had genotype 5 or 6. Overall, 17% of the patients had cirrhosis.

The viral load rapidly decreased in all patients treated with sofosbuvir irrespective of the HCV genotype, IL28B status, race, or the presence or absence of cirrhosis. Ninety-nine percent of patients with genotype 1, 4, 5, or 6 achieved a rapid virologic response, and 90% achieved a sustained virologic response at 12 weeks after completion of treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin. Patients with cirrhosis had a slightly lower rate of sustained virologic response (80%, compared with 92% in patients without cirrhosis). Also, patients with non-CC IL28B genotypes had a lower rate of sustained virologic response (87% in non-CC allele vs 98% in patients with the favorable CC allele).

The FISSION trial19 recruited previously untreated patients with genotype 2 or 3 and randomized them to therapy with either sofosbuvir plus ribavirin in a weight-based dose for 12 weeks, or 24 weeks of interferon and ribavirin. In this study, 20% of patients in each treatment group had cirrhosis.

As in the NEUTRINO trial, the viral load rapidly decreased in all patients treated with sofosbuvir irrespective of HCV genotype, IL28B status, race, or the presence or absence of cirrhosis. Here, 100% of patients with genotype 2 or 3 who were treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin achieved a rapid virologic response. Differences in outcome emerged based on genotype: 97% of those with genotype 2 and 56% of those with genotype 3 achieved a sustained virologic response. The overall rate was 67%, which was not different from patients treated with peg-interferon and ribavirin. In the subgroup of patients with cirrhosis, 47% of those treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin achieved a sustained virologic response, vs 38% of those who received peg-interferon plus ribavirin.

In both the NEUTRINO and FISSION trials, few patients discontinued treatment, with higher rates of most adverse events occurring in patients treated with peg-interferon and ribavirin.

POSITRON,20 a phase 3 clinical trial, tested sofosbuvir in patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3 who were ineligible for peg-interferon, unwilling to take peg-interferon, or unable to tolerate peg-interferon (mainly because of clinically significant psychiatric disorders). Patients were randomized to two treatment groups for 12 weeks: sofosbuvir plus ribavirin, or placebo. About 50% of patients had HCV genotype 3, and 16% had cirrhosis.

The overall rate of sustained virologic response at 12 weeks after treatment was 78% in the sofosbuvir-and-ribavirin group (93% in genotype 2 patients and 61% in genotype 3 patients). Again, cirrhosis was associated with a lower rate of sustained virologic response (61% of patients with cirrhosis achieved a sustained virologic response vs 81% of patients without cirrhosis). None of the sofosbuvir-treated patients had virologic failure while on treatment.

FUSION,20 another phase 3 trial, evaluated sofosbuvir in patients infected with HCV genotype 2 or 3 for whom interferon-based treatment had failed. They were randomized to either 12 weeks or 16 weeks of sofosbuvir and weight-based ribavirin treatment. About 60% of patients had HCV genotype 3, and 34% had cirrhosis.

The overall sustained virologic response rate was 50% in the patients treated for 12 weeks and 73% in those treated for 16 weeks: specifically, 86% of patients with genotype 2 achieved a sustained virologic response at 12 weeks and 94% at 16 weeks, whereas in those with genotype 3 the rates were 30% at 12 weeks and 62% at 16 weeks.

Cirrhosis was again a predictor of lack of response to sofosbuvir. In the group treated for 12 weeks, 31% of those with cirrhosis achieved a sustained virologic response compared with 61% in those without cirrhosis. In the group treated for 16 weeks, 61% of those with cirrhosis achieved a sustained virologic response compared with 76% in those without cirrhosis.

In both the POSITRON and FUSION trials, relapse accounted for all treatment failures, and no virologic resistance was detected in patients who did not have a sustained virologic response. The investigators concluded that 12 weeks of treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin can be effective for HCV genotype 2 infection, but extending the treatment to 16 weeks may be beneficial for genotype 3. This may be especially important in patients with cirrhosis or those who did not have a response to peg-interferon-based treatment.

VALENCE,21 an ongoing phase 3 trial in Europe, is assessing the safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir 400 mg once daily and weight-based ribavirin in patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3. Eighty-five percent of the trial participants have received previous treatment, and 21% have cirrhosis. Patients were originally randomized in a 4:1 ratio to receive sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for 12 weeks or matching placebo, but as a result of emerging data suggesting that patients with genotype 3 would benefit from more than 12 weeks of treatment, the study was subsequently amended to extend treatment to 24 weeks for patients with genotype 3.

Overall rates of sustained virologic response were 93% in patients with genotype 2 and 85% in patients with genotype 3. In previously treated patients with genotype 2 who were treated for 12 weeks, the rates of sustained virologic response were 91% in those without cirrhosis vs 88% in those with cirrhosis. In previously treated patients with genotype 3, the rates in those treated for 24 weeks were 87% in patients without cirrhosis vs 60% with cirrhosis. The safety profile was consistent with that of ribavirin.

Side effects of sofosbuvir

In clinical trials, side effects occurred most often when sofosbuvir was combined with interferon and ribavirin and were consistent with the known side effects of the latter two agents. The most frequently reported side effects included fatigue, insomnia, nausea, rash, anemia, headache, and arthralgia, with most of these adverse events rated by treating clinicians as being mild in severity.15,20

In the ATOMIC trial, the most common events leading to drug discontinuation were anemia and neutropenia, both associated with interferon and ribavirin. Patients receiving sofosbuvir monotherapy after 12 weeks of triple therapy showed rapid improvement in hemoglobin levels and neutrophil counts, indicating that hematologic abnormalities attributed solely to sofosbuvir are minimal. In the FISSION trial, the incidence of adverse events was consistently lower in those receiving sofosbuvir-ribavirin than in patients receiving interferon-ribavirin without sofosbuvir.19

In the POSITRON trial, discontinuation of sofosbuvir because of adverse events was uncommon, and there were no differences in the incidence of adverse events and laboratory abnormalities between patients with and without cirrhosis when they received sofosbuvir and ribavirin.20

Sofosbuvir dosage and indications

Sofosbuvir is approved in an oral dose of 400 mg once daily in combination with ribavirin for patients infected with HCV genotype 2 or 3 and in combination with ribavirin and interferon alfa in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4 (Table 3). It could be considered for HCV genotype 1 in combination with ribavirin alone for 24 weeks in patients who are ineligible for interferon.

Sofosbuvir is also recommended in combination with ribavirin in HCV-infected patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who are awaiting liver transplantation, for up to 48 weeks or until they receive a transplant, to prevent posttransplant reinfection with HCV.

Sofosbuvir is expensive

A course of therapy is expected to cost about $84,000, which is significantly more than the cost of previous triple therapy (peg-interferon, ribavirin, and either boceprevir or telaprevir).22 This high cost will undoubtedly lead to less widespread use in developing countries, and potentially even in the United States. As newer direct-acting antiviral agents become available, the price will likely come down, enhancing access to these drugs.

SIMEPREVIR: A SECOND-GENERATION PROTEASE INHIBITOR

Telaprevir and boceprevir are NS3/A4 protease inhibitors that belong to the alfa-ketoamid derivative class. Simeprevir belongs to the macrocyclic class and has a different way of binding to the target enzyme.23 Like sofosbuvir, simeprevir was recently approved by the FDA for the treatment of HCV genotype 1.

The therapeutic efficacy of simeprevir has been tested in several clinical trials (Table 4), including QUEST-124 and QUEST-225 (in previously untreated patients), PROMISE26 (in prior relapsers), and ASPIRE27 (in prior partial and null responders). Results from these trials showed high overall rates of sustained virologic response with triple therapy (ie, simeprevir combined with peg-interferon and ribavirin). It was generally well tolerated, and most adverse events reported during 12 weeks of treatment were of mild to moderate severity.

In QUEST-1 and QUEST-2, both double-blind phase 3 clinical trials, previously untreated patients infected with HCV genotype 1 were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either simeprevir 150 mg daily or placebo for 12 weeks; both groups also received peg-interferon and ribavirin. Patients then received peg-interferon and ribavirin alone for 12 or 36 weeks in the simeprevir group (based on response) and for 36 weeks in the placebo group.

The overall rate of sustained virologic response at 12 weeks was 80% in the simeprevir group (75% in those with genotype 1a and 85% in those with genotype 1b) vs 50% in the placebo group (receiving peg-interferon and ribavirin alone).24,25

PROMISE,26 another double-blind randomized phase 3 clinical trial, evaluated simeprevir in patients with HCV genotype 1 who relapsed after previous interferon-based therapy. It had a similar design to QUEST-1 and QUEST-2, and 15% of all patients had cirrhosis.

The overall sustained virologic response rate at 12 weeks after treatment was 79% in the simeprevir group (70% in patients with genotype 1a and 86% in those with genotype 1b) vs 37% in the placebo group. Rates were similar in patients with absent to moderate fibrosis (82%), advanced fibrosis (73%), or cirrhosis (74%).

ASPIRE.27 Simeprevir efficacy in patients with HCV genotype 1 for whom previous therapy with peg-interferon and ribavirin had failed was tested in ASPIRE, a double-blind randomized phase 2 clinical trial. Patients were randomized to receive simeprevir (either 100 mg or 150 mg daily) for 12, 24, or 48 weeks in combination with 48 weeks of peg-interferon and ribavirin, or placebo plus peg-interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks.

The primary end point was the rate of sustained virologic response at 24 weeks. Overall, rates were 61% to 80% for the simeprevir treatment groups compared with 23% with placebo, regardless of prior response to peg-interferon and ribavirin. By subgroup, rates were:

- 77% to 89% with simeprevir vs 37% with placebo in prior relapsers

- 48% to 86% with simeprevir vs 9% with placebo in prior partial responders

- 38% to 59% with placebo vs 19% for prior nonresponders.

The best rates of sustained viral response at 24 weeks were in the groups that received simeprevir 150 mg daily: 85% in prior relapsers, 75% in prior partial responders, and 51% in prior nonresponders.

Simeprevir vs other direct-acting antiviral drugs

Advantages of simeprevir over the earlier protease inhibitors include once-daily dosing, a lower rate of adverse events (the most common being fatigue, headache, rash, photosensitivity, and pruritus), a lower likelihood of discontinuation because of adverse events, and fewer drug-drug interactions (since it is a weak inhibitor of the CYP3A4 enzyme).

Unlike sofosbuvir, simeprevir was FDA-approved only for HCV genotype 1 and in combination with interferon alfa and ribavirin. Compared with sofosbuvir, the treatment duration with simeprevir regimens is longer overall (interferon alfa and ribavirin are given for 12 weeks in sofosbuvir-based regimens vs 24 to 48 weeks with simeprevir). As with sofosbuvir, the estimated cost of simeprevir is high, about $66,000 for a 12-week course.

Simeprevir dosage and indications

Simeprevir was approved at an oral dose of 150 mg once daily in combination with ribavirin and interferon alfa in patients with HCV genotype 1 (Table 5).

The approved regimens for simeprevir are fixed in total duration based on the patient’s treatment history. Specifically, all patients receive the drug in combination with peg-interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks. Then, previously untreated patients and prior relapsers continue to receive peg-interferon and ribavirin alone for another 12 weeks, and those with a partial or null response continue with these drugs for another 36 weeks.

Patients infected with HCV genotype 1a should be screened for the NS3 Q80K polymorphism at baseline, as it has been associated with substantially reduced response to simeprevir.

Sofosbuvir and simeprevir in combination

The COSMOS trial.28 Given their differences in mechanism of action, sofosbuvir and simeprevir are being tested in combination. The COSMOS trial is an ongoing phase 2 randomized open-label study investigating the efficacy and safety of simeprevir and sofosbuvir in combination with and without ribavirin in patients with HCV genotype 1, including nonresponders and those with cirrhosis. Early results are promising, with very high rates of sustained virologic response with the sofosbuvir-simeprevir combination (93% to 100%) and indicate that the addition of ribavirin might not be needed to achieve sustained virologic response in this patient population.

THE FUTURE

The emergence of all-oral regimens for HCV treatment with increasingly sophisticated agents such as sofosbuvir and simeprevir will dramatically alter the management of HCV patients. In view of the improvement in sustained virologic response rates with these treatments, and since most HCV-infected persons have no symptoms, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention29 recently recommended one-time testing of the cohort in which the prevalence of HCV infection is highest: all persons born between 1945 and 1965. This undoubtedly will increase the detection of this infection—and the number of new patients expecting treatment.

Future drugs promise further improvements (Table 6).30–35 Advances in knowledge of the HCV molecular structure have led to the development of numerous direct-acting antiviral agents with very specific viral targets. A second wave of protease inhibitors and of nucleoside and nonnucleoside polymerase inhibitors will soon be available. Inhibitors of NS5A (a protein important in the assembly of the viral replication complex) such as daclatasvir and ledipasvir, are currently in phase 3 clinical trials. Other viral proteins involved in assembly of the virus, including the core protein and p7, are being explored as drug targets. In addition, inhibiting host targets such as cyclophilin A and miR122 has gained traction recently, with specific agents currently in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials.

Factors that previously were major determinants of response to treatment, such as IL28B genotype, viral load, race, age, extent of fibrosis, and genotype 1 subtypes, will become much less important with the introduction of highly potent direct-acting antiviral agents.

Many all-oral combinations are being evaluated in clinical trials. For example, the open-label, phase 2 LONESTAR trial tested the utility of combining sofosbuvir and ledipasvir (an NS5A inhibitor) with and without ribavirin for 8 or 12 weeks in previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1, and for 12 weeks in patients with HCV genotype 1 who did not achieve a sustained virologic response after receiving a protease inhibitor-based regimen (half of whom had compensated cirrhosis).36 Sustained virologic response rates were very high (95% to 100%) in both previously treated and previously untreated patients, including those with cirrhosis. Similar rates were achieved by the 8-week and 12-week groups in noncirrhotic patients who had not been previously treated for HCV. The typical hematologic abnormalities associated with interferon were not observed except for mild anemia in patients who received ribavirin. These results suggest that the combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir could offer a very effective, short, all-oral treatment for patients with HCV genotype 1, including those with cirrhosis, who up to now have been difficult to treat.

Challenges remaining

The success of sofosbuvir and simeprevir paves the way for interferon-free regimens.37 For a long time, the treatment of HCV infection required close monitoring of patients while managing the side effects of interferon, but the current and emerging direct-acting antiviral agents will soon change this practice. Given the synergistic effects of combination therapy—targeting the virus at multiple locations, decreasing the likelihood of drug resistance, and improving efficacy—combination regimens seem to be the optimal solution to the HCV epidemic. Lower risk of side effects and shorter treatment duration will definitely improve the acceptance of any new regimen. New agents that act against conserved viral targets, thereby yielding activity across multiple genotypes, will be advantageous as well. Table 7 compares the rates of sustained virologic response of the different currently approved HCV treatment regimens.

Clinical challenges remain, including the management of special patient populations for whom data are still limited. These include patients with cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, renal failure, and concurrent infection with human immunodeficiency virus, and patients who have undergone solid organ transplantation. Clinical trials are under way to evaluate the treatment options for these patients, who will likely need to wait for the emergence of additional agents before dramatic improvement in sustained virologic response rates may be expected.38

As the treatment of HCV becomes simpler, safer, and more effective, primary care physicians will increasingly be expected to manage it. Difficult-to-treat patients, including the special populations above, will require specialist management and individualized treatment regimens, at least until better therapies are available. The high projected cost of the new agents may limit access, at least initially. However, the dramatic improvement in sustained virologic response rates and all that that implies in terms of decreased risk of advanced liver disease and its complications will undoubtedly make these therapies cost-effective.39

In late 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sofosbuvir and simeprevir, the newest direct-acting antiviral agents for treating chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Multiple clinical trials have demonstrated dramatically improved treatment outcomes with these agents, opening the door to all-oral regimens or interferon-free regimens as the future standard of care for HCV.

In this article, we discuss the results of the trials that established the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir and simeprevir and led to their FDA approval. We also summarize the importance of these agents and evaluate other direct-acting antivirals currently in the pipeline for HCV treatment.

HCV IS A RISING PROBLEM

Chronic HCV infection is a major clinical and public health problem, with the estimated number of people infected exceeding 170 million worldwide, including 3.2 million in the United States.1 It is a leading cause of cirrhosis, and its complications include hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure. Cirrhosis due to HCV remains the leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States, accounting for nearly 40% of liver transplants in adults.2

The clinical impact of HCV will only continue to escalate, and in parallel, so will the cost to society. Models suggest that HCV-related deaths will double between 2010 and 2019, and considering only direct medical costs, the projected financial burden of treating HCV-related disease during this interval is estimated at between $6.5 and $13.6 billion.3

AN RNA VIRUS WITH SIX GENOTYPES

HCV, first identified in 1989, is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA flavivirus of the Hepacivirus genus measuring 50 to 60 nm in diameter.4 There are six viral genotypes, with genotype 1 being the most common in the United States and traditionally the most difficult to treat.

Once inside the host cell, the virus releases its RNA strand, which is translated into a single polyprotein of about 3,000 amino acids. This large molecule is then cleaved by proteases into several domains: three structural proteins (C, E1, and E2), a small protein called p7, and six nonstructural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B) (Figure 1).5 These nonstructural proteins enable the virus to replicate.

GOAL OF TREATING HCV: A SUSTAINED VIROLOGIC RESPONSE

The aim of HCV treatment is to achieve a sustained virologic response, defined as having no detectable viral RNA after completion of antiviral therapy. This is associated with substantially better clinical outcomes, lower rates of liver-related morbidity and all-cause mortality, and stabilization of or even improvement in liver histology.6,7 This end point has traditionally been assessed at 6 months after the end of therapy, but recent data suggest the rates at 12 weeks are essentially equivalent.

Table 1 summarizes the patterns of virologic response in treating HCV infection.

Interferon plus ribavirin: The standard of care for many years

HCV treatment has evolved over the past 20 years. Before 2011, the standard of care was a combination of interferon alfa-polyethylene glycol (peg-interferon), given as a weekly injection, and oral ribavirin. Neither drug has specific antiviral activity, and when they are used together they result in a sustained virologic response in fewer than 50% of patients with HCV genotype 1 and, at best, in 70% to 80% of patients with other genotypes.8

Nearly all patients receiving interferon experience side effects, which can be serious. Fatigue and flu-like symptoms are common, and the drug can also cause psychiatric symptoms (including depression or psychosis), weight loss, seizures, peripheral neuropathy, and bone marrow suppression. Ribavirin causes hemolysis and skin complications and is teratogenic.9

An important bit of information to know when using interferon is the patient’s IL28B genotype. This refers to a single-nucleotide polymorphism (C or T) on chromosome 19q13 (rs12979860) upstream of the IL28B gene encoding for interferon lambda-3. It is strongly associated with responsiveness to interferon: patients with the IL28B CC genotype have a much better chance of a sustained virologic response with interferon than do patients with CT or TT.

Boceprevir and telaprevir: First-generation protease inhibitors

In May 2011, the FDA approved the NS3/4A protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir for treating HCV genotype 1, marking the beginning of the era of direct-acting antiviral agents.10 When these drugs are used in combination with peg-interferon alfa and ribavirin, up to 75% of patients with HCV genotype 1 who have had no previous treatment achieve a sustained virologic response.

But despite greatly improving the response rate, these first-generation protease inhibitors have substantial limitations. Twenty-five percent of patients with HCV genotype 1 who have received no previous treatment and 71% of patients who did not respond to previous treatment will not achieve a sustained virologic response with these agents.11 Further, they are effective only against HCV genotype 1, being highly specific for the amino acid target sequence of the NS3 region.

Also, they must be used in combination with interferon alfa and ribavirin because the virus needs to mutate only a little—a few amino-acid substitutions—to gain resistance to them.12 Therefore, patients are still exposed to interferon and ribavirin, with their toxicity. In addition, dysgeusia is seen with boceprevir, rash with telaprevir, and anemia with both.13,14

Finally, serious drug-drug interactions prompted the FDA to impose warnings for the use of these agents with other medications that interact with CYP3A4, the principal enzyme responsible for their metabolism. Thus, these significant adverse effects dampen the enthusiasm of patients contemplating a long course of treatment with these agents.

The need to improve the rate of sustained virologic response, shorten the duration of treatment, avoid serious side effects, improve efficacy in treating patients infected with genotypes other than 1, and, importantly, eliminate the need for interferon alfa and its serious adverse effects have driven the development of new direct-acting antiviral agents, including the two newly FDA-approved drugs, sofosbuvir and simeprevir.

SOFOSBUVIR: A POLYMERASE INHIBITOR

Sofosbuvir is a uridine nucleotide analogue that selectively inhibits the HCV NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Figure 1). It targets the highly conserved nucleotide-binding pocket of this enzyme and functions as a chain terminator.15 While the protease inhibitors are genotype-dependent, inhibition of the highly conserved viral polymerase has an impact that spans genotypes.

Early clinical trials of sofosbuvir

Sofosbuvir has been tested in combination with interferon alfa and ribavirin, as well as in interferon-free regimens (Table 2).16–20

Rodriguez-Torres et al,15

- 56% with sofosbuvir 100 mg, peg-interferon, and ribavirin

- 83% with sofosbuvir 200 mg, peg-interferon, and ribavirin

- 80% with sofosbuvir 400 mg, peg-interferon, and ribavirin

- 43% with peg-interferon and ribavirin alone.

The ATOMIC trial16 tested the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir in combination with peg-interferon and ribavirin in patients with HCV genotype 1, 4, or 6, without cirrhosis, who had not received any previous treatment. Patients with HCV genotype 1 were randomized to three treatments:

- Sofosbuvir 400 mg orally once daily plus peg-interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks

- The same regimen, but for 24 weeks

- Sofosbuvir plus peg-interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks, followed by 12 weeks of either sofosbuvir monotherapy or sofosbuvir plus ribavirin.