User login

In short team huddles, trainees and PACT teamlets meet to coordinate care and identify ways to improve team processes under the guidance of faculty members who reinforce collaborative practice and continuous improvement.

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). Part of the VA New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs (Boise, Cleveland, San Francisco, Seattle and West Haven) are utilizing VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents, nurse practitioner (NP) students and residents (postgraduate), and other health professions trainees, such as pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants (PAs), dieticians, etc for primary care practice.

The CoEPCEs are interprofessional academic patient aligned care teams (PACTs) defined by VA as a PACT that has at least 2 professions of trainees on the team engaged in learning.

The San Francisco VA Health Care System (SFVAHCS) Education in PACT (EdPACT)/CoEPCE developed and implemented a workplace learning model that embeds trainees into PACT teamlets and clinic workflow.1 Trainees are organized in practice partner triads with 2 second- or third-year internal medicine residents (R2s and R3s) and 1 NP student or resident. Physician residents rotate every 2 months between inpatient and outpatient settings and NP trainees are present continuously for 12 months. In this model, each trainee in the triad has his/her own patient panel and serves as a partner who delivers care to his/her partners’ patients when they are unavailable. Didactic sessions on clinical content and on topics related to the core domains occur 3-times weekly during pre- and postclinic conferences.2

Methods

In 2015, evaluators from the OAA reviewed background documents and conducted open-ended interviews with 9 CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, VA faculty, VA facility leadership, and affiliate faculty. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the huddle to participants, veterans, and the VA.

The Huddle

With the emphasis on patient-centered medical homes and team-based care in the Affordable Care Act, there is an urgent need to develop new training models that provide future health professionals with skills that support interprofessional communication and collaborative practice.2,3 A key aim of the CoEPCE is to expand workplace learning strategies and clinical opportunities for interprofessional trainees to work together as a team to anticipate and address the health care needs of veterans. Research suggests that patient care improves when team members develop a shared understanding of each other’s skill sets, care procedures, and values.4 In 2010, the SFVAHCS began phasing in VA-mandated PACTs. Each patient-aligned care teamlet serves about 1,200 patients and is composed of physician or NP primary care provider(s) (PCPs) and a registered nurse (RN) care manager, a licensed vocational nurse (LVN), and a medical support assistant (MSA). About every 3 teamlets also work with a profession-specific team member from the Social Work and Pharmacy departments. The implementation of PACT created an opportunity for the CoEPCE to add trainees of various professions to 13 preexisting PACTs in 3 SFVAHCS primary care clinics. This arrangement benefits both trainees and teamlets: trainees learn how to collaborate with clinic staff while the clinic PACT teamlets benefit from coaching by faculty skilled in team-based care.

As part of routine clinical activities, huddles provide opportunities for workplace learning related to coordination of care, building relationships, and developing a sense of camaraderie that is essential for team-based, patient-centered care. In their ideal state, huddles are “…the hub of interprofessional, team-based care”; they provide a venue where trainees can learn communication skills, team member roles, systems issues and resources, and clinical knowledge expected of full-time providers and staff.5 Embedding faculty in huddles as huddle coaches help ensure trainees are learning and applying these skills.

Planning and Implementation

After OAA funded the CoEPCE in 2011, faculty had 6 months to develop the EdPACT curriculum, which included a team building retreat, interactive didactic sessions, and workplace learning activities (ie, huddles). In July 2011, 10 trainee triads (each consisting of 2 physician residents and either a student NP or resident NP) were added to preexisting PACTs at the San Francisco VA Medical Center primary care clinic and 2 community-based outpatient clinics.

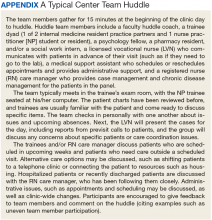

These trainee triads partnered with their PACT teamlets and huddled for 15 minutes at the beginning of each clinic day to plan for the day’s patients and future scheduled patients and to coordinate care needs for their panel of patients. CoEPCE staff built on this basic huddle model and made the following lasting modifications:

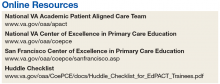

- Developed and implemented a huddle coach model and a huddle checklist to provide structure and feedback to the huddle (Online Resources);

- Scheduled huddles in NP student/resident’s exam room to reduce the hierarchy in the trainee triad;

- Incorporated trainees from other professions and levels into the huddle (psychology fellows, pharmacy residents, social work); and

- Linked the PACT teamlet (staff) to quality improvement projects that are discussed periodically in huddles and didactics.

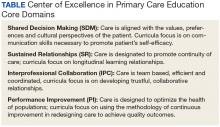

Curriculum. The huddle allows for practical application of the 4 core domains: interprofessional collaboration (IPC), performance improvement (PI), sustained relationships (SR), and shared decision making (SDM) that shape the CoE curriculum.

Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is the primary domain reinforced in the huddle. Trainees learn key content in half-day team retreats held at the beginning of the academic year and in interactive didactic sessions. These sessions, which draw on concepts from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s TeamSTEPPS, an evidence-based teamwork training program for health care workers, teach skills like closed-loop communication, check-backs, negotiation, and conflict resolution.

The CoE trainee triads also lead quality improvement (QI) projects, and the huddle is a venue for getting input, which reinforces the CoE’s performance improvement (PI) curriculum. For example, PACT teamlet staff members provide trainees with feedback on proposed QI interventions, such as increasing the use of telephone visits. The huddle supports SR among team members that enhance patient care while improving the quality of the clinic experience for team members. Strengthened communications and increased understanding of team member roles and system resources supports a patient-centered approach to care and lays the foundation for SDM between patients and team members.

Faculty Roles and Development. The CoEPCE physician and NP faculty members who precept and function as huddle coaches participate in monthly 2-hour faculty development sessions to address topics related to IPE. At least 1 session each year covers review of the items on the huddle checklist, tips on how to coach a huddle, discussions of the role of huddle coaches, and feedback and mentoring skills. Many huddle coach activities are inherent to clinical precepting, such as identifying appropriate clinical resources and answering clinical questions, but the core function of the huddle coach is to facilitate effective communication among team members.

Initially, a coach may guide the huddle by rounding up team members or directing the agenda of the huddle (ie, prompting the LVN to present the day’s patients and suggesting the group identify and discuss high-risk patients). As the year progresses, coaches often take a backseat, and the huddle may be facilitated by the trainees, the RN, LVN, or a combination of all members. During the huddle, coaches also may reinforce specific communication skills, such as a “check back” or ISBAR ( Identify who you are, describe the Situation, provide Background information, offer an Assessment of the situation/needs, make a Recommendation or Request)—skills that are taught during CoE didactic sessions.

The coach may call attention to particular feedback points, such as clarification of the order as an excellent example of a check-back. Each preceptor coaches 1 huddle per precepting session. After the teams huddle, preceptors do a smaller, shorter huddle in the precepting room to share successes, such as interprofessional trainees demonstrating backup behavior (eg, “in today’s huddle, I saw a great example of backup behavior when the medicine resident offered to show the NP student how to consent someone”) and discuss challenges (eg, getting all team members to the huddle).

Resources. The CoE staff schedule at least 20 huddles per week and coordinate preceptor and room schedules. The other required resources are clinic staff (RNs, LVNs, and MSAs) and exam rooms large enough to accommodate 8 or more people. Sufficient staffing coverage and staggered huddles also are important to allow cross-coverage for other clinical duties while team members and faculty are huddling.

Monitoring and Assessment. The CoE staff administer the Team Development Measure (TDM) twice yearly and a modified version of the TEAM 360 feedback survey once per year.6-9 The TDM member gages perceptions of team functioning (cohesiveness, communication, role clarity, and clarity of goals and means). Teams meet with a facilitator to debrief their TDM results and discuss ways to improve their team processes. Three-quarters of the way through the academic year, team members also complete the modified TEAM 360 survey on trainees. Each trainee receives a report describing his/her self-ratings and aggregate team member ratings on leadership, communication, interpersonal skills, and feedback.

Partnerships

In addition to CoEPCE staff and faculty support and engagement, huddles at SFVAHCS have benefited from partnerships with VA primary care leadership and with academic affiliates. In particular, support from the VA clinic directors and nurse managers was key to instituting changes to the clinics’ structure to include interprofessional trainees in huddles.

The affiliates—the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine and School of Nursing—are integral partners and assist with NP student and medicine resident recruitment. These affiliates also participate in planning and refinement of CoEPCE curricular activities. The UCSF School of Nursing, School of Medicine, and Center for Faculty Educators were involved in the planning stages of the huddle model.

Challenges and Solutions

Having a staffing ratio that supports trainee participation in and learning through huddles is critical. Preceptor coverage must be in sufficient numbers to allow preceptors to coach the huddles, and clinical staff must be adequate to create cohesive and consistent teams for trainee providers. Clinic staff turnover and changes in teamlet staff can be very disruptive. Over time, teamlet staff often know key details and helpful contextual information about particular patients and clinic processes. This knowledge may be lost with turnover among teamlet staff. If team members miss huddles due to staffing shortages and clinical duties, there may be delays and errors in patient care. For example, if information discussed in the huddle is not relayed to the absent team member in a timely or accurate manner, care may be impacted. However, potential disruptions can be mitigated by a high-functioning team with strong communication skills and situational awareness who readily assist and distribute the workload.

Consistent huddling, huddle coaches, and checklists all help stabilize the group. Integration of trainees in the PACT team initially requires extra work because trainees are part-time and have panels significantly smaller than 1,200 (which means the teamlet staff are assigned to multiple trainee and provider huddles). However, teamlet staff find working with trainee teams personally rewarding, and developing highly functioning teams helps prevent burnout. Integration of pharmacy, psychology, and social work trainees takes time and thoughtful planning of activities and contributions that enhance team functioning while not overburdening trainees with additional responsibilities. If these other professions of health trainees are joining several teams’ huddles, their role may be to weigh in as needed vs preparing for and reviewing several PCPs’ schedules and patients in advance.

Factors for Success

The VA facility and primary care clinic leadership’s commitment to supporting staff participation in huddles was critical for integrating trainees into PACTs. Additionally, VA facility commitment to implementation of PACT was a key facilitating factor. Implementation of PACT, including huddles, has not been consistent at all VA facilities.10 The CoE’s approach to integrating trainees into the huddle was an opportunity to strengthen the huddle and to teach new staff members how to participate with team members in huddles. CoEPCE leadership, which has embraced change, meets regularly with facility leadership as well as an advisory board of UCSF leaders to update them on CoE activities. A critical factor for success was CoE expertise in interprofessional education and its ability to integrate concepts from the 4 core domains into an effective workplace learning experience, including attention to the physical space, scheduling, and the development and implementation of the huddle coach role and checklist.

Accomplishments and Benefits

There is evidence that SFVAHCS team huddles are achieving their goals and CoE trainees are being trained to provide team-based, patient-centered care to veterans. Key outcomes of the CoE’s approach to huddles include components in the next sections.

Interprofessional Educational Capacity. The CoEPCE faculty and staff consider the huddle to be one of the best ways to teach interprofessional communication and collaboration, team functioning, and clinical performance. Unlike a traditional didactic, classroom-based session on interprofessional collaboration, the huddle is an opportunity for health care professionals to work together to provide care in a clinic setting. It also is an activity in which the CoE has continued innovative activities, such as adding a preceptor huddle, incorporating additional professions, and encouraging panel management activities during huddles. The CoE has received significant interest and visibility and has been invited to share the model in numerous presentations.

Participants’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Skills, and Competencies. An aim of the CoE approach to huddles was to provide trainees with general skills in the core domain interprofessional collaboration, including teamwork and communication that transfer to other settings, such as inpatient teams and specialty clinics. Learning about other professions and their scopes of practice and areas of expertise can be helpful beyond huddles and primary care. Trainees also learn concepts and practices from the other core domains:

- Performance Improvement: The huddle is a venue for utilizing clinic metrics as well as focusing on QI projects that benefit from a team approach to solving problems;

- Sustained Relationships: The huddles support and teach the importance of relationships among the team. Trainees learn about the roles of clinic staff members, and clinic staff have more opportunities to interact with trainees and become comfortable with them, supporting coordinated care; and

- Shared Decision Making: The huddle is a venue for discussing options for providing patient decision-making support, such as discussing the pros and cons of colon cancer screening with a patient, improving patient-centered care.

Additionally, huddles can address differences in trainee clinical expertise. For example, new physician interns with less experience in the clinic receive more coaching on system resources and patient histories than they might otherwise. Nurse practitioner residents often participate in more than 1 huddle team and transition to a coaching role.

Sustained Relationships, Role Clarity, and Collaboration. The huddles are structured to facilitate SRs among trainees from different professions and among the PACT teamlet in detail as a team. The huddle increases team efficiency by educating trainees and staff about team member roles. For example, trainees learn how the LVNs and MSAs prepare for patient visits. Moreover, an opportunity exists to learn how provider and clinic staff expertise may overlap. Registered nurse care managers, who have their own hypertension clinics, can help manage a patient’s medication titration. Similarly, pharmacy trainees can suggest a referral for a complicated patient with diabetes to pharmacy clinic, where clinical pharmacists can adjust medications and provide patient education for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia. In this way, role clarity is improved and trainees learn how team members work within their scope of practice and are better able to “share the care.”

There is evidence that huddles have resulted in expanded participant interprofessional collaboration. The CoE administers the TDM twice a year and the huddle teams rate themselves on several dimensions—cohesiveness, communications, role clarity, and goals.6,7 The 2011/2012 findings showed that nearly all teams showed improvement, with the mean scores for all teams combined increasing from 59.4 in the fall to 64.6 in the spring (max score is 100).5 These scores increased again from 62.2 to 70.3 in 2012/2013, from 66.6 to 70.2 in 2013/2014, and from 64.6 to 69.9 in 2014/2015.

Expanding Clinical Knowledge. At the individual level, the huddle is an opportunity for a trainees to expand their clinical expertise in real time. The huddle provides exposure to a variety of patients and corresponding patient care needs. Trainees are encouraged to complete patient prerounds before the huddle in order to focus the huddle discussion on patients with chronic conditions, complex needs, recent hospitalizations, and upcoming appointments. The CoEPCE trainees tap into the expertise and experience of their team members and coach.

The clinic staff can get information from trainees about their plan of care while trainees get a more complete picture of a patient’s situation—for example, medical or social history or communication preferences. Additionally, trainees learn team skills, such as communication techniques and warm handoffs, which can be used in other clinical settings outside primary care and beyond the VA. As trainees advance, the huddle helps them learn to delegate appropriately, practice conflict negotiation, and develop leadership skills.

Participants’ Satisfaction With Interventions. There is qualitative evidence that clinic RNs and LVNs like huddles and appreciate having the opportunity to communicate in person with providers as well as to teach trainees how to work interprofessionally. Faculty members who are huddle coaches report that they develop a richer understanding of the skill set of trainees, information that can inform CoE curriculum design. Trainees appreciate the opportunity to develop relationships with team members. In end-of-year interviews, they describe their teams as their families, making them feel more connected to the clinic. They also enjoyed starting their day with familiar faces.

Primary Care Delivery System. The huddle is an important component of a system-wide transformation to provide team-based, patient-centered care to veterans. The efforts to strengthen and standardize the huddle have the potential to hasten this transformation while improving relationships and quality of care. Additionally, the CoE approach to integrating trainees into huddles has broader applicability and is being considered for adoption by other VA centers of excellence in primary care education.Primary Care Services. The huddle may contribute to efficiencies in a busy clinic setting. For example, the RN care manager can have upward of 1,200 patients on his/her panel and, between staff and trainees, as many as 12 health care providers with whom to communicate. The huddle strengthens the communications with providers and is an opportunity to touch base on the patients, coordinate care, and keep track of high-risk patients who might fall off the radar otherwise. The huddle is flexible and can occur with various clinic staff and providers. A 2-person huddle can occur between an RN and the primary provider. The QI projects that have been developed as a result of a huddle have improved clinic primary care services, such as completing opiate consents and urine toxicology or improving continuity through increased telephone clinic usage.Patient Outcomes. The huddle results in a more robust plan of care than might be developed by an individual provider who might not have time to consider options outside the individual’s scope of practice or expertise. While there are few clinical outcomes that are directly influenced by huddles alone, huddles may help indirectly improve patient outcomes on many fronts, including:

- Increased continuity of care because the patient now has a team focusing on care. At times throughout the day when team members cannot talk face to face with one another or with the patient, they know about the patient’s situation and are better able to establish a rapport when the patient calls or comes in for the visit. Trainees also become familiar with their practice partners’ patients, which allows them to ensure continuity when the patient’s primary trainee provider is out of clinic;

- Panel management and identifying and tracking sicker patients;

- Increased access, such as identifying patients who could receive care by a telephone visit, decreasing the number of no shows by making extra efforts to remind patients about appointments and improving follow up; and

- Improved population health outcomes from process improvements, such as the development of a process for having patients on opioids sign new contracts or identifying diabetics who might benefit from a group approach to care.

The Future

The huddle coach concept and checklist have been shared broadly and have applicability in other teaching settings where providers and clinic staff are learning how to implement huddles. A video and resources on “How to Huddle” are available at suzannecgordon.com/how-to-huddle/.

Under stage 2 of the CoEPCE program, the CoE will develop a huddle coaching program implementation kit composed of a huddle how-to guide and a coach training manual. The CoE team huddle is one of many VA huddles and an example of how the huddle continues to evolve. It is a versatile tool that can be used to focus on different topics and include different professions. Currently, it is being adapted to specialty care where there is large patient volume, such as cardiology and orthopedics.

1. Rugen KW, Watts SA, Janson SL, et al. Veteran Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education: transforming nurse practitioner education. Nurs Outlook. 2014;62(2):78-88.

2. Chang A, Bowen JL, Buranosky RA, et al. Transforming primary care training--patient-centered medical home entrustable professional activities for internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(6):801-809.

3. Zabar S, Adams J, Kurland S, et al. Charting a key competency domain: understanding resident physician interprofessional collaboration (IPC) skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(8):846-853.

4. Institute of Medicine. Measuring the Impact of Interprofessional Education (IPE) on Collaborative Practice and Patient Outcomes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015.

5. Shunk R, Dulay M, Chou C, Janson S, O’Brien BC. Huddle-coaching: a dynamic intervention for trainees and staff to support team-based care. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):244-250.

6. Stock R, Mahoney E, Carney PA. Measuring team development in clinical care settings. Fam Med. 2013;45(10):691-700.

7. PeaceHealth. Team development measure. https://www.peacehealth.org/about-peacehealth/medical-professionals/eugene-springfield-cottage-grove/team-measure/Pages/measure. Accessed August 16, 2018.

8. American Board of Internal Medicine. Teamwork effectiveness assessment module. https://team.abim.org. Accessed August 16, 2018.

9. Chesluk BJ, Bernabeo E, Hess B, Lynn LA, Reddy S, Holmboe ES. A new tool to give hospitalists feedback to improve interprofessional teamwork and advance patient care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(11):2485-2492.

10. Rodriguez HP, Meredith LS, Hamilton AB, Yano EM, Rubenstein LV. Huddle up!: the adoption and use of structured team communication for VA medical home implementation. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40(4):286-299.

In short team huddles, trainees and PACT teamlets meet to coordinate care and identify ways to improve team processes under the guidance of faculty members who reinforce collaborative practice and continuous improvement.

In short team huddles, trainees and PACT teamlets meet to coordinate care and identify ways to improve team processes under the guidance of faculty members who reinforce collaborative practice and continuous improvement.

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). Part of the VA New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs (Boise, Cleveland, San Francisco, Seattle and West Haven) are utilizing VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents, nurse practitioner (NP) students and residents (postgraduate), and other health professions trainees, such as pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants (PAs), dieticians, etc for primary care practice.

The CoEPCEs are interprofessional academic patient aligned care teams (PACTs) defined by VA as a PACT that has at least 2 professions of trainees on the team engaged in learning.

The San Francisco VA Health Care System (SFVAHCS) Education in PACT (EdPACT)/CoEPCE developed and implemented a workplace learning model that embeds trainees into PACT teamlets and clinic workflow.1 Trainees are organized in practice partner triads with 2 second- or third-year internal medicine residents (R2s and R3s) and 1 NP student or resident. Physician residents rotate every 2 months between inpatient and outpatient settings and NP trainees are present continuously for 12 months. In this model, each trainee in the triad has his/her own patient panel and serves as a partner who delivers care to his/her partners’ patients when they are unavailable. Didactic sessions on clinical content and on topics related to the core domains occur 3-times weekly during pre- and postclinic conferences.2

Methods

In 2015, evaluators from the OAA reviewed background documents and conducted open-ended interviews with 9 CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, VA faculty, VA facility leadership, and affiliate faculty. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the huddle to participants, veterans, and the VA.

The Huddle

With the emphasis on patient-centered medical homes and team-based care in the Affordable Care Act, there is an urgent need to develop new training models that provide future health professionals with skills that support interprofessional communication and collaborative practice.2,3 A key aim of the CoEPCE is to expand workplace learning strategies and clinical opportunities for interprofessional trainees to work together as a team to anticipate and address the health care needs of veterans. Research suggests that patient care improves when team members develop a shared understanding of each other’s skill sets, care procedures, and values.4 In 2010, the SFVAHCS began phasing in VA-mandated PACTs. Each patient-aligned care teamlet serves about 1,200 patients and is composed of physician or NP primary care provider(s) (PCPs) and a registered nurse (RN) care manager, a licensed vocational nurse (LVN), and a medical support assistant (MSA). About every 3 teamlets also work with a profession-specific team member from the Social Work and Pharmacy departments. The implementation of PACT created an opportunity for the CoEPCE to add trainees of various professions to 13 preexisting PACTs in 3 SFVAHCS primary care clinics. This arrangement benefits both trainees and teamlets: trainees learn how to collaborate with clinic staff while the clinic PACT teamlets benefit from coaching by faculty skilled in team-based care.

As part of routine clinical activities, huddles provide opportunities for workplace learning related to coordination of care, building relationships, and developing a sense of camaraderie that is essential for team-based, patient-centered care. In their ideal state, huddles are “…the hub of interprofessional, team-based care”; they provide a venue where trainees can learn communication skills, team member roles, systems issues and resources, and clinical knowledge expected of full-time providers and staff.5 Embedding faculty in huddles as huddle coaches help ensure trainees are learning and applying these skills.

Planning and Implementation

After OAA funded the CoEPCE in 2011, faculty had 6 months to develop the EdPACT curriculum, which included a team building retreat, interactive didactic sessions, and workplace learning activities (ie, huddles). In July 2011, 10 trainee triads (each consisting of 2 physician residents and either a student NP or resident NP) were added to preexisting PACTs at the San Francisco VA Medical Center primary care clinic and 2 community-based outpatient clinics.

These trainee triads partnered with their PACT teamlets and huddled for 15 minutes at the beginning of each clinic day to plan for the day’s patients and future scheduled patients and to coordinate care needs for their panel of patients. CoEPCE staff built on this basic huddle model and made the following lasting modifications:

- Developed and implemented a huddle coach model and a huddle checklist to provide structure and feedback to the huddle (Online Resources);

- Scheduled huddles in NP student/resident’s exam room to reduce the hierarchy in the trainee triad;

- Incorporated trainees from other professions and levels into the huddle (psychology fellows, pharmacy residents, social work); and

- Linked the PACT teamlet (staff) to quality improvement projects that are discussed periodically in huddles and didactics.

Curriculum. The huddle allows for practical application of the 4 core domains: interprofessional collaboration (IPC), performance improvement (PI), sustained relationships (SR), and shared decision making (SDM) that shape the CoE curriculum.

Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is the primary domain reinforced in the huddle. Trainees learn key content in half-day team retreats held at the beginning of the academic year and in interactive didactic sessions. These sessions, which draw on concepts from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s TeamSTEPPS, an evidence-based teamwork training program for health care workers, teach skills like closed-loop communication, check-backs, negotiation, and conflict resolution.

The CoE trainee triads also lead quality improvement (QI) projects, and the huddle is a venue for getting input, which reinforces the CoE’s performance improvement (PI) curriculum. For example, PACT teamlet staff members provide trainees with feedback on proposed QI interventions, such as increasing the use of telephone visits. The huddle supports SR among team members that enhance patient care while improving the quality of the clinic experience for team members. Strengthened communications and increased understanding of team member roles and system resources supports a patient-centered approach to care and lays the foundation for SDM between patients and team members.

Faculty Roles and Development. The CoEPCE physician and NP faculty members who precept and function as huddle coaches participate in monthly 2-hour faculty development sessions to address topics related to IPE. At least 1 session each year covers review of the items on the huddle checklist, tips on how to coach a huddle, discussions of the role of huddle coaches, and feedback and mentoring skills. Many huddle coach activities are inherent to clinical precepting, such as identifying appropriate clinical resources and answering clinical questions, but the core function of the huddle coach is to facilitate effective communication among team members.

Initially, a coach may guide the huddle by rounding up team members or directing the agenda of the huddle (ie, prompting the LVN to present the day’s patients and suggesting the group identify and discuss high-risk patients). As the year progresses, coaches often take a backseat, and the huddle may be facilitated by the trainees, the RN, LVN, or a combination of all members. During the huddle, coaches also may reinforce specific communication skills, such as a “check back” or ISBAR ( Identify who you are, describe the Situation, provide Background information, offer an Assessment of the situation/needs, make a Recommendation or Request)—skills that are taught during CoE didactic sessions.

The coach may call attention to particular feedback points, such as clarification of the order as an excellent example of a check-back. Each preceptor coaches 1 huddle per precepting session. After the teams huddle, preceptors do a smaller, shorter huddle in the precepting room to share successes, such as interprofessional trainees demonstrating backup behavior (eg, “in today’s huddle, I saw a great example of backup behavior when the medicine resident offered to show the NP student how to consent someone”) and discuss challenges (eg, getting all team members to the huddle).

Resources. The CoE staff schedule at least 20 huddles per week and coordinate preceptor and room schedules. The other required resources are clinic staff (RNs, LVNs, and MSAs) and exam rooms large enough to accommodate 8 or more people. Sufficient staffing coverage and staggered huddles also are important to allow cross-coverage for other clinical duties while team members and faculty are huddling.

Monitoring and Assessment. The CoE staff administer the Team Development Measure (TDM) twice yearly and a modified version of the TEAM 360 feedback survey once per year.6-9 The TDM member gages perceptions of team functioning (cohesiveness, communication, role clarity, and clarity of goals and means). Teams meet with a facilitator to debrief their TDM results and discuss ways to improve their team processes. Three-quarters of the way through the academic year, team members also complete the modified TEAM 360 survey on trainees. Each trainee receives a report describing his/her self-ratings and aggregate team member ratings on leadership, communication, interpersonal skills, and feedback.

Partnerships

In addition to CoEPCE staff and faculty support and engagement, huddles at SFVAHCS have benefited from partnerships with VA primary care leadership and with academic affiliates. In particular, support from the VA clinic directors and nurse managers was key to instituting changes to the clinics’ structure to include interprofessional trainees in huddles.

The affiliates—the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine and School of Nursing—are integral partners and assist with NP student and medicine resident recruitment. These affiliates also participate in planning and refinement of CoEPCE curricular activities. The UCSF School of Nursing, School of Medicine, and Center for Faculty Educators were involved in the planning stages of the huddle model.

Challenges and Solutions

Having a staffing ratio that supports trainee participation in and learning through huddles is critical. Preceptor coverage must be in sufficient numbers to allow preceptors to coach the huddles, and clinical staff must be adequate to create cohesive and consistent teams for trainee providers. Clinic staff turnover and changes in teamlet staff can be very disruptive. Over time, teamlet staff often know key details and helpful contextual information about particular patients and clinic processes. This knowledge may be lost with turnover among teamlet staff. If team members miss huddles due to staffing shortages and clinical duties, there may be delays and errors in patient care. For example, if information discussed in the huddle is not relayed to the absent team member in a timely or accurate manner, care may be impacted. However, potential disruptions can be mitigated by a high-functioning team with strong communication skills and situational awareness who readily assist and distribute the workload.

Consistent huddling, huddle coaches, and checklists all help stabilize the group. Integration of trainees in the PACT team initially requires extra work because trainees are part-time and have panels significantly smaller than 1,200 (which means the teamlet staff are assigned to multiple trainee and provider huddles). However, teamlet staff find working with trainee teams personally rewarding, and developing highly functioning teams helps prevent burnout. Integration of pharmacy, psychology, and social work trainees takes time and thoughtful planning of activities and contributions that enhance team functioning while not overburdening trainees with additional responsibilities. If these other professions of health trainees are joining several teams’ huddles, their role may be to weigh in as needed vs preparing for and reviewing several PCPs’ schedules and patients in advance.

Factors for Success

The VA facility and primary care clinic leadership’s commitment to supporting staff participation in huddles was critical for integrating trainees into PACTs. Additionally, VA facility commitment to implementation of PACT was a key facilitating factor. Implementation of PACT, including huddles, has not been consistent at all VA facilities.10 The CoE’s approach to integrating trainees into the huddle was an opportunity to strengthen the huddle and to teach new staff members how to participate with team members in huddles. CoEPCE leadership, which has embraced change, meets regularly with facility leadership as well as an advisory board of UCSF leaders to update them on CoE activities. A critical factor for success was CoE expertise in interprofessional education and its ability to integrate concepts from the 4 core domains into an effective workplace learning experience, including attention to the physical space, scheduling, and the development and implementation of the huddle coach role and checklist.

Accomplishments and Benefits

There is evidence that SFVAHCS team huddles are achieving their goals and CoE trainees are being trained to provide team-based, patient-centered care to veterans. Key outcomes of the CoE’s approach to huddles include components in the next sections.

Interprofessional Educational Capacity. The CoEPCE faculty and staff consider the huddle to be one of the best ways to teach interprofessional communication and collaboration, team functioning, and clinical performance. Unlike a traditional didactic, classroom-based session on interprofessional collaboration, the huddle is an opportunity for health care professionals to work together to provide care in a clinic setting. It also is an activity in which the CoE has continued innovative activities, such as adding a preceptor huddle, incorporating additional professions, and encouraging panel management activities during huddles. The CoE has received significant interest and visibility and has been invited to share the model in numerous presentations.

Participants’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Skills, and Competencies. An aim of the CoE approach to huddles was to provide trainees with general skills in the core domain interprofessional collaboration, including teamwork and communication that transfer to other settings, such as inpatient teams and specialty clinics. Learning about other professions and their scopes of practice and areas of expertise can be helpful beyond huddles and primary care. Trainees also learn concepts and practices from the other core domains:

- Performance Improvement: The huddle is a venue for utilizing clinic metrics as well as focusing on QI projects that benefit from a team approach to solving problems;

- Sustained Relationships: The huddles support and teach the importance of relationships among the team. Trainees learn about the roles of clinic staff members, and clinic staff have more opportunities to interact with trainees and become comfortable with them, supporting coordinated care; and

- Shared Decision Making: The huddle is a venue for discussing options for providing patient decision-making support, such as discussing the pros and cons of colon cancer screening with a patient, improving patient-centered care.

Additionally, huddles can address differences in trainee clinical expertise. For example, new physician interns with less experience in the clinic receive more coaching on system resources and patient histories than they might otherwise. Nurse practitioner residents often participate in more than 1 huddle team and transition to a coaching role.

Sustained Relationships, Role Clarity, and Collaboration. The huddles are structured to facilitate SRs among trainees from different professions and among the PACT teamlet in detail as a team. The huddle increases team efficiency by educating trainees and staff about team member roles. For example, trainees learn how the LVNs and MSAs prepare for patient visits. Moreover, an opportunity exists to learn how provider and clinic staff expertise may overlap. Registered nurse care managers, who have their own hypertension clinics, can help manage a patient’s medication titration. Similarly, pharmacy trainees can suggest a referral for a complicated patient with diabetes to pharmacy clinic, where clinical pharmacists can adjust medications and provide patient education for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia. In this way, role clarity is improved and trainees learn how team members work within their scope of practice and are better able to “share the care.”

There is evidence that huddles have resulted in expanded participant interprofessional collaboration. The CoE administers the TDM twice a year and the huddle teams rate themselves on several dimensions—cohesiveness, communications, role clarity, and goals.6,7 The 2011/2012 findings showed that nearly all teams showed improvement, with the mean scores for all teams combined increasing from 59.4 in the fall to 64.6 in the spring (max score is 100).5 These scores increased again from 62.2 to 70.3 in 2012/2013, from 66.6 to 70.2 in 2013/2014, and from 64.6 to 69.9 in 2014/2015.

Expanding Clinical Knowledge. At the individual level, the huddle is an opportunity for a trainees to expand their clinical expertise in real time. The huddle provides exposure to a variety of patients and corresponding patient care needs. Trainees are encouraged to complete patient prerounds before the huddle in order to focus the huddle discussion on patients with chronic conditions, complex needs, recent hospitalizations, and upcoming appointments. The CoEPCE trainees tap into the expertise and experience of their team members and coach.

The clinic staff can get information from trainees about their plan of care while trainees get a more complete picture of a patient’s situation—for example, medical or social history or communication preferences. Additionally, trainees learn team skills, such as communication techniques and warm handoffs, which can be used in other clinical settings outside primary care and beyond the VA. As trainees advance, the huddle helps them learn to delegate appropriately, practice conflict negotiation, and develop leadership skills.

Participants’ Satisfaction With Interventions. There is qualitative evidence that clinic RNs and LVNs like huddles and appreciate having the opportunity to communicate in person with providers as well as to teach trainees how to work interprofessionally. Faculty members who are huddle coaches report that they develop a richer understanding of the skill set of trainees, information that can inform CoE curriculum design. Trainees appreciate the opportunity to develop relationships with team members. In end-of-year interviews, they describe their teams as their families, making them feel more connected to the clinic. They also enjoyed starting their day with familiar faces.

Primary Care Delivery System. The huddle is an important component of a system-wide transformation to provide team-based, patient-centered care to veterans. The efforts to strengthen and standardize the huddle have the potential to hasten this transformation while improving relationships and quality of care. Additionally, the CoE approach to integrating trainees into huddles has broader applicability and is being considered for adoption by other VA centers of excellence in primary care education.Primary Care Services. The huddle may contribute to efficiencies in a busy clinic setting. For example, the RN care manager can have upward of 1,200 patients on his/her panel and, between staff and trainees, as many as 12 health care providers with whom to communicate. The huddle strengthens the communications with providers and is an opportunity to touch base on the patients, coordinate care, and keep track of high-risk patients who might fall off the radar otherwise. The huddle is flexible and can occur with various clinic staff and providers. A 2-person huddle can occur between an RN and the primary provider. The QI projects that have been developed as a result of a huddle have improved clinic primary care services, such as completing opiate consents and urine toxicology or improving continuity through increased telephone clinic usage.Patient Outcomes. The huddle results in a more robust plan of care than might be developed by an individual provider who might not have time to consider options outside the individual’s scope of practice or expertise. While there are few clinical outcomes that are directly influenced by huddles alone, huddles may help indirectly improve patient outcomes on many fronts, including:

- Increased continuity of care because the patient now has a team focusing on care. At times throughout the day when team members cannot talk face to face with one another or with the patient, they know about the patient’s situation and are better able to establish a rapport when the patient calls or comes in for the visit. Trainees also become familiar with their practice partners’ patients, which allows them to ensure continuity when the patient’s primary trainee provider is out of clinic;

- Panel management and identifying and tracking sicker patients;

- Increased access, such as identifying patients who could receive care by a telephone visit, decreasing the number of no shows by making extra efforts to remind patients about appointments and improving follow up; and

- Improved population health outcomes from process improvements, such as the development of a process for having patients on opioids sign new contracts or identifying diabetics who might benefit from a group approach to care.

The Future

The huddle coach concept and checklist have been shared broadly and have applicability in other teaching settings where providers and clinic staff are learning how to implement huddles. A video and resources on “How to Huddle” are available at suzannecgordon.com/how-to-huddle/.

Under stage 2 of the CoEPCE program, the CoE will develop a huddle coaching program implementation kit composed of a huddle how-to guide and a coach training manual. The CoE team huddle is one of many VA huddles and an example of how the huddle continues to evolve. It is a versatile tool that can be used to focus on different topics and include different professions. Currently, it is being adapted to specialty care where there is large patient volume, such as cardiology and orthopedics.

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). Part of the VA New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs (Boise, Cleveland, San Francisco, Seattle and West Haven) are utilizing VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents, nurse practitioner (NP) students and residents (postgraduate), and other health professions trainees, such as pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants (PAs), dieticians, etc for primary care practice.

The CoEPCEs are interprofessional academic patient aligned care teams (PACTs) defined by VA as a PACT that has at least 2 professions of trainees on the team engaged in learning.

The San Francisco VA Health Care System (SFVAHCS) Education in PACT (EdPACT)/CoEPCE developed and implemented a workplace learning model that embeds trainees into PACT teamlets and clinic workflow.1 Trainees are organized in practice partner triads with 2 second- or third-year internal medicine residents (R2s and R3s) and 1 NP student or resident. Physician residents rotate every 2 months between inpatient and outpatient settings and NP trainees are present continuously for 12 months. In this model, each trainee in the triad has his/her own patient panel and serves as a partner who delivers care to his/her partners’ patients when they are unavailable. Didactic sessions on clinical content and on topics related to the core domains occur 3-times weekly during pre- and postclinic conferences.2

Methods

In 2015, evaluators from the OAA reviewed background documents and conducted open-ended interviews with 9 CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, VA faculty, VA facility leadership, and affiliate faculty. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the huddle to participants, veterans, and the VA.

The Huddle

With the emphasis on patient-centered medical homes and team-based care in the Affordable Care Act, there is an urgent need to develop new training models that provide future health professionals with skills that support interprofessional communication and collaborative practice.2,3 A key aim of the CoEPCE is to expand workplace learning strategies and clinical opportunities for interprofessional trainees to work together as a team to anticipate and address the health care needs of veterans. Research suggests that patient care improves when team members develop a shared understanding of each other’s skill sets, care procedures, and values.4 In 2010, the SFVAHCS began phasing in VA-mandated PACTs. Each patient-aligned care teamlet serves about 1,200 patients and is composed of physician or NP primary care provider(s) (PCPs) and a registered nurse (RN) care manager, a licensed vocational nurse (LVN), and a medical support assistant (MSA). About every 3 teamlets also work with a profession-specific team member from the Social Work and Pharmacy departments. The implementation of PACT created an opportunity for the CoEPCE to add trainees of various professions to 13 preexisting PACTs in 3 SFVAHCS primary care clinics. This arrangement benefits both trainees and teamlets: trainees learn how to collaborate with clinic staff while the clinic PACT teamlets benefit from coaching by faculty skilled in team-based care.

As part of routine clinical activities, huddles provide opportunities for workplace learning related to coordination of care, building relationships, and developing a sense of camaraderie that is essential for team-based, patient-centered care. In their ideal state, huddles are “…the hub of interprofessional, team-based care”; they provide a venue where trainees can learn communication skills, team member roles, systems issues and resources, and clinical knowledge expected of full-time providers and staff.5 Embedding faculty in huddles as huddle coaches help ensure trainees are learning and applying these skills.

Planning and Implementation

After OAA funded the CoEPCE in 2011, faculty had 6 months to develop the EdPACT curriculum, which included a team building retreat, interactive didactic sessions, and workplace learning activities (ie, huddles). In July 2011, 10 trainee triads (each consisting of 2 physician residents and either a student NP or resident NP) were added to preexisting PACTs at the San Francisco VA Medical Center primary care clinic and 2 community-based outpatient clinics.

These trainee triads partnered with their PACT teamlets and huddled for 15 minutes at the beginning of each clinic day to plan for the day’s patients and future scheduled patients and to coordinate care needs for their panel of patients. CoEPCE staff built on this basic huddle model and made the following lasting modifications:

- Developed and implemented a huddle coach model and a huddle checklist to provide structure and feedback to the huddle (Online Resources);

- Scheduled huddles in NP student/resident’s exam room to reduce the hierarchy in the trainee triad;

- Incorporated trainees from other professions and levels into the huddle (psychology fellows, pharmacy residents, social work); and

- Linked the PACT teamlet (staff) to quality improvement projects that are discussed periodically in huddles and didactics.

Curriculum. The huddle allows for practical application of the 4 core domains: interprofessional collaboration (IPC), performance improvement (PI), sustained relationships (SR), and shared decision making (SDM) that shape the CoE curriculum.

Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is the primary domain reinforced in the huddle. Trainees learn key content in half-day team retreats held at the beginning of the academic year and in interactive didactic sessions. These sessions, which draw on concepts from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s TeamSTEPPS, an evidence-based teamwork training program for health care workers, teach skills like closed-loop communication, check-backs, negotiation, and conflict resolution.

The CoE trainee triads also lead quality improvement (QI) projects, and the huddle is a venue for getting input, which reinforces the CoE’s performance improvement (PI) curriculum. For example, PACT teamlet staff members provide trainees with feedback on proposed QI interventions, such as increasing the use of telephone visits. The huddle supports SR among team members that enhance patient care while improving the quality of the clinic experience for team members. Strengthened communications and increased understanding of team member roles and system resources supports a patient-centered approach to care and lays the foundation for SDM between patients and team members.

Faculty Roles and Development. The CoEPCE physician and NP faculty members who precept and function as huddle coaches participate in monthly 2-hour faculty development sessions to address topics related to IPE. At least 1 session each year covers review of the items on the huddle checklist, tips on how to coach a huddle, discussions of the role of huddle coaches, and feedback and mentoring skills. Many huddle coach activities are inherent to clinical precepting, such as identifying appropriate clinical resources and answering clinical questions, but the core function of the huddle coach is to facilitate effective communication among team members.

Initially, a coach may guide the huddle by rounding up team members or directing the agenda of the huddle (ie, prompting the LVN to present the day’s patients and suggesting the group identify and discuss high-risk patients). As the year progresses, coaches often take a backseat, and the huddle may be facilitated by the trainees, the RN, LVN, or a combination of all members. During the huddle, coaches also may reinforce specific communication skills, such as a “check back” or ISBAR ( Identify who you are, describe the Situation, provide Background information, offer an Assessment of the situation/needs, make a Recommendation or Request)—skills that are taught during CoE didactic sessions.

The coach may call attention to particular feedback points, such as clarification of the order as an excellent example of a check-back. Each preceptor coaches 1 huddle per precepting session. After the teams huddle, preceptors do a smaller, shorter huddle in the precepting room to share successes, such as interprofessional trainees demonstrating backup behavior (eg, “in today’s huddle, I saw a great example of backup behavior when the medicine resident offered to show the NP student how to consent someone”) and discuss challenges (eg, getting all team members to the huddle).

Resources. The CoE staff schedule at least 20 huddles per week and coordinate preceptor and room schedules. The other required resources are clinic staff (RNs, LVNs, and MSAs) and exam rooms large enough to accommodate 8 or more people. Sufficient staffing coverage and staggered huddles also are important to allow cross-coverage for other clinical duties while team members and faculty are huddling.

Monitoring and Assessment. The CoE staff administer the Team Development Measure (TDM) twice yearly and a modified version of the TEAM 360 feedback survey once per year.6-9 The TDM member gages perceptions of team functioning (cohesiveness, communication, role clarity, and clarity of goals and means). Teams meet with a facilitator to debrief their TDM results and discuss ways to improve their team processes. Three-quarters of the way through the academic year, team members also complete the modified TEAM 360 survey on trainees. Each trainee receives a report describing his/her self-ratings and aggregate team member ratings on leadership, communication, interpersonal skills, and feedback.

Partnerships

In addition to CoEPCE staff and faculty support and engagement, huddles at SFVAHCS have benefited from partnerships with VA primary care leadership and with academic affiliates. In particular, support from the VA clinic directors and nurse managers was key to instituting changes to the clinics’ structure to include interprofessional trainees in huddles.

The affiliates—the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine and School of Nursing—are integral partners and assist with NP student and medicine resident recruitment. These affiliates also participate in planning and refinement of CoEPCE curricular activities. The UCSF School of Nursing, School of Medicine, and Center for Faculty Educators were involved in the planning stages of the huddle model.

Challenges and Solutions

Having a staffing ratio that supports trainee participation in and learning through huddles is critical. Preceptor coverage must be in sufficient numbers to allow preceptors to coach the huddles, and clinical staff must be adequate to create cohesive and consistent teams for trainee providers. Clinic staff turnover and changes in teamlet staff can be very disruptive. Over time, teamlet staff often know key details and helpful contextual information about particular patients and clinic processes. This knowledge may be lost with turnover among teamlet staff. If team members miss huddles due to staffing shortages and clinical duties, there may be delays and errors in patient care. For example, if information discussed in the huddle is not relayed to the absent team member in a timely or accurate manner, care may be impacted. However, potential disruptions can be mitigated by a high-functioning team with strong communication skills and situational awareness who readily assist and distribute the workload.

Consistent huddling, huddle coaches, and checklists all help stabilize the group. Integration of trainees in the PACT team initially requires extra work because trainees are part-time and have panels significantly smaller than 1,200 (which means the teamlet staff are assigned to multiple trainee and provider huddles). However, teamlet staff find working with trainee teams personally rewarding, and developing highly functioning teams helps prevent burnout. Integration of pharmacy, psychology, and social work trainees takes time and thoughtful planning of activities and contributions that enhance team functioning while not overburdening trainees with additional responsibilities. If these other professions of health trainees are joining several teams’ huddles, their role may be to weigh in as needed vs preparing for and reviewing several PCPs’ schedules and patients in advance.

Factors for Success

The VA facility and primary care clinic leadership’s commitment to supporting staff participation in huddles was critical for integrating trainees into PACTs. Additionally, VA facility commitment to implementation of PACT was a key facilitating factor. Implementation of PACT, including huddles, has not been consistent at all VA facilities.10 The CoE’s approach to integrating trainees into the huddle was an opportunity to strengthen the huddle and to teach new staff members how to participate with team members in huddles. CoEPCE leadership, which has embraced change, meets regularly with facility leadership as well as an advisory board of UCSF leaders to update them on CoE activities. A critical factor for success was CoE expertise in interprofessional education and its ability to integrate concepts from the 4 core domains into an effective workplace learning experience, including attention to the physical space, scheduling, and the development and implementation of the huddle coach role and checklist.

Accomplishments and Benefits

There is evidence that SFVAHCS team huddles are achieving their goals and CoE trainees are being trained to provide team-based, patient-centered care to veterans. Key outcomes of the CoE’s approach to huddles include components in the next sections.

Interprofessional Educational Capacity. The CoEPCE faculty and staff consider the huddle to be one of the best ways to teach interprofessional communication and collaboration, team functioning, and clinical performance. Unlike a traditional didactic, classroom-based session on interprofessional collaboration, the huddle is an opportunity for health care professionals to work together to provide care in a clinic setting. It also is an activity in which the CoE has continued innovative activities, such as adding a preceptor huddle, incorporating additional professions, and encouraging panel management activities during huddles. The CoE has received significant interest and visibility and has been invited to share the model in numerous presentations.

Participants’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Skills, and Competencies. An aim of the CoE approach to huddles was to provide trainees with general skills in the core domain interprofessional collaboration, including teamwork and communication that transfer to other settings, such as inpatient teams and specialty clinics. Learning about other professions and their scopes of practice and areas of expertise can be helpful beyond huddles and primary care. Trainees also learn concepts and practices from the other core domains:

- Performance Improvement: The huddle is a venue for utilizing clinic metrics as well as focusing on QI projects that benefit from a team approach to solving problems;

- Sustained Relationships: The huddles support and teach the importance of relationships among the team. Trainees learn about the roles of clinic staff members, and clinic staff have more opportunities to interact with trainees and become comfortable with them, supporting coordinated care; and

- Shared Decision Making: The huddle is a venue for discussing options for providing patient decision-making support, such as discussing the pros and cons of colon cancer screening with a patient, improving patient-centered care.

Additionally, huddles can address differences in trainee clinical expertise. For example, new physician interns with less experience in the clinic receive more coaching on system resources and patient histories than they might otherwise. Nurse practitioner residents often participate in more than 1 huddle team and transition to a coaching role.

Sustained Relationships, Role Clarity, and Collaboration. The huddles are structured to facilitate SRs among trainees from different professions and among the PACT teamlet in detail as a team. The huddle increases team efficiency by educating trainees and staff about team member roles. For example, trainees learn how the LVNs and MSAs prepare for patient visits. Moreover, an opportunity exists to learn how provider and clinic staff expertise may overlap. Registered nurse care managers, who have their own hypertension clinics, can help manage a patient’s medication titration. Similarly, pharmacy trainees can suggest a referral for a complicated patient with diabetes to pharmacy clinic, where clinical pharmacists can adjust medications and provide patient education for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia. In this way, role clarity is improved and trainees learn how team members work within their scope of practice and are better able to “share the care.”

There is evidence that huddles have resulted in expanded participant interprofessional collaboration. The CoE administers the TDM twice a year and the huddle teams rate themselves on several dimensions—cohesiveness, communications, role clarity, and goals.6,7 The 2011/2012 findings showed that nearly all teams showed improvement, with the mean scores for all teams combined increasing from 59.4 in the fall to 64.6 in the spring (max score is 100).5 These scores increased again from 62.2 to 70.3 in 2012/2013, from 66.6 to 70.2 in 2013/2014, and from 64.6 to 69.9 in 2014/2015.

Expanding Clinical Knowledge. At the individual level, the huddle is an opportunity for a trainees to expand their clinical expertise in real time. The huddle provides exposure to a variety of patients and corresponding patient care needs. Trainees are encouraged to complete patient prerounds before the huddle in order to focus the huddle discussion on patients with chronic conditions, complex needs, recent hospitalizations, and upcoming appointments. The CoEPCE trainees tap into the expertise and experience of their team members and coach.

The clinic staff can get information from trainees about their plan of care while trainees get a more complete picture of a patient’s situation—for example, medical or social history or communication preferences. Additionally, trainees learn team skills, such as communication techniques and warm handoffs, which can be used in other clinical settings outside primary care and beyond the VA. As trainees advance, the huddle helps them learn to delegate appropriately, practice conflict negotiation, and develop leadership skills.

Participants’ Satisfaction With Interventions. There is qualitative evidence that clinic RNs and LVNs like huddles and appreciate having the opportunity to communicate in person with providers as well as to teach trainees how to work interprofessionally. Faculty members who are huddle coaches report that they develop a richer understanding of the skill set of trainees, information that can inform CoE curriculum design. Trainees appreciate the opportunity to develop relationships with team members. In end-of-year interviews, they describe their teams as their families, making them feel more connected to the clinic. They also enjoyed starting their day with familiar faces.

Primary Care Delivery System. The huddle is an important component of a system-wide transformation to provide team-based, patient-centered care to veterans. The efforts to strengthen and standardize the huddle have the potential to hasten this transformation while improving relationships and quality of care. Additionally, the CoE approach to integrating trainees into huddles has broader applicability and is being considered for adoption by other VA centers of excellence in primary care education.Primary Care Services. The huddle may contribute to efficiencies in a busy clinic setting. For example, the RN care manager can have upward of 1,200 patients on his/her panel and, between staff and trainees, as many as 12 health care providers with whom to communicate. The huddle strengthens the communications with providers and is an opportunity to touch base on the patients, coordinate care, and keep track of high-risk patients who might fall off the radar otherwise. The huddle is flexible and can occur with various clinic staff and providers. A 2-person huddle can occur between an RN and the primary provider. The QI projects that have been developed as a result of a huddle have improved clinic primary care services, such as completing opiate consents and urine toxicology or improving continuity through increased telephone clinic usage.Patient Outcomes. The huddle results in a more robust plan of care than might be developed by an individual provider who might not have time to consider options outside the individual’s scope of practice or expertise. While there are few clinical outcomes that are directly influenced by huddles alone, huddles may help indirectly improve patient outcomes on many fronts, including:

- Increased continuity of care because the patient now has a team focusing on care. At times throughout the day when team members cannot talk face to face with one another or with the patient, they know about the patient’s situation and are better able to establish a rapport when the patient calls or comes in for the visit. Trainees also become familiar with their practice partners’ patients, which allows them to ensure continuity when the patient’s primary trainee provider is out of clinic;

- Panel management and identifying and tracking sicker patients;

- Increased access, such as identifying patients who could receive care by a telephone visit, decreasing the number of no shows by making extra efforts to remind patients about appointments and improving follow up; and

- Improved population health outcomes from process improvements, such as the development of a process for having patients on opioids sign new contracts or identifying diabetics who might benefit from a group approach to care.

The Future

The huddle coach concept and checklist have been shared broadly and have applicability in other teaching settings where providers and clinic staff are learning how to implement huddles. A video and resources on “How to Huddle” are available at suzannecgordon.com/how-to-huddle/.

Under stage 2 of the CoEPCE program, the CoE will develop a huddle coaching program implementation kit composed of a huddle how-to guide and a coach training manual. The CoE team huddle is one of many VA huddles and an example of how the huddle continues to evolve. It is a versatile tool that can be used to focus on different topics and include different professions. Currently, it is being adapted to specialty care where there is large patient volume, such as cardiology and orthopedics.

1. Rugen KW, Watts SA, Janson SL, et al. Veteran Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education: transforming nurse practitioner education. Nurs Outlook. 2014;62(2):78-88.

2. Chang A, Bowen JL, Buranosky RA, et al. Transforming primary care training--patient-centered medical home entrustable professional activities for internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(6):801-809.

3. Zabar S, Adams J, Kurland S, et al. Charting a key competency domain: understanding resident physician interprofessional collaboration (IPC) skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(8):846-853.

4. Institute of Medicine. Measuring the Impact of Interprofessional Education (IPE) on Collaborative Practice and Patient Outcomes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015.

5. Shunk R, Dulay M, Chou C, Janson S, O’Brien BC. Huddle-coaching: a dynamic intervention for trainees and staff to support team-based care. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):244-250.

6. Stock R, Mahoney E, Carney PA. Measuring team development in clinical care settings. Fam Med. 2013;45(10):691-700.

7. PeaceHealth. Team development measure. https://www.peacehealth.org/about-peacehealth/medical-professionals/eugene-springfield-cottage-grove/team-measure/Pages/measure. Accessed August 16, 2018.

8. American Board of Internal Medicine. Teamwork effectiveness assessment module. https://team.abim.org. Accessed August 16, 2018.

9. Chesluk BJ, Bernabeo E, Hess B, Lynn LA, Reddy S, Holmboe ES. A new tool to give hospitalists feedback to improve interprofessional teamwork and advance patient care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(11):2485-2492.

10. Rodriguez HP, Meredith LS, Hamilton AB, Yano EM, Rubenstein LV. Huddle up!: the adoption and use of structured team communication for VA medical home implementation. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40(4):286-299.

1. Rugen KW, Watts SA, Janson SL, et al. Veteran Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education: transforming nurse practitioner education. Nurs Outlook. 2014;62(2):78-88.

2. Chang A, Bowen JL, Buranosky RA, et al. Transforming primary care training--patient-centered medical home entrustable professional activities for internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(6):801-809.

3. Zabar S, Adams J, Kurland S, et al. Charting a key competency domain: understanding resident physician interprofessional collaboration (IPC) skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(8):846-853.

4. Institute of Medicine. Measuring the Impact of Interprofessional Education (IPE) on Collaborative Practice and Patient Outcomes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015.

5. Shunk R, Dulay M, Chou C, Janson S, O’Brien BC. Huddle-coaching: a dynamic intervention for trainees and staff to support team-based care. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):244-250.

6. Stock R, Mahoney E, Carney PA. Measuring team development in clinical care settings. Fam Med. 2013;45(10):691-700.

7. PeaceHealth. Team development measure. https://www.peacehealth.org/about-peacehealth/medical-professionals/eugene-springfield-cottage-grove/team-measure/Pages/measure. Accessed August 16, 2018.

8. American Board of Internal Medicine. Teamwork effectiveness assessment module. https://team.abim.org. Accessed August 16, 2018.

9. Chesluk BJ, Bernabeo E, Hess B, Lynn LA, Reddy S, Holmboe ES. A new tool to give hospitalists feedback to improve interprofessional teamwork and advance patient care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(11):2485-2492.

10. Rodriguez HP, Meredith LS, Hamilton AB, Yano EM, Rubenstein LV. Huddle up!: the adoption and use of structured team communication for VA medical home implementation. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40(4):286-299.