User login

CHICAGO – When Superstorm Sandy was done barreling across New York City and the surrounding coast 14 months ago, flooding streets and knocking out power to millions, Dr. Laura Evans, director of the medical intensive care unit at Bellevue Hospital along the East River in Manhattan, emerged weary and wiser.

At one point, the ICU faced the real possibility of having just a handful of working power outlets to serve dozens of patients, and the number of crucial decisions to be made rose along with the water level. "Prior to the storm, disaster preparedness was not a core interest of mine, and it’s something I hope never to repeat," Dr. Evans told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In a recent survey, ICU practitioners who endured havoc caused by Sandy in the New York City region reported having had little to no training in emergency evacuation care. "When I look at these data, I think there is a mismatch in terms of our self-perception of readiness compared to what patients actually require in an evacuation. It’s in stark contrast to the checklist we use every single day to put in a central venous catheter," said Dr. Mary Alice King, who presented her research as a copanelist with Dr. Evans. Dr. King is medical director of the pediatric trauma ICU at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Contingency for loss of power

The nation’s oldest public hospital, Bellevue is adjacent to New York’s tidal East River. The river’s high tide the evening of Oct. 29, 2012, coincided with the arrival of the storm’s surge, and within minutes the hospital’s basement was inundated with 10 million gallons of seawater. And then the main power went out, taking with it the use of 32 elevators, the entire voice-over-Internet-protocol phone system, and the electronic medical records system, Dr. Evans said. The flood also knocked out the hospital’s ability to connect to its Internet servers. "We had very impaired means of communication," Dr. Evans said.

Survey data presented by Dr. King underscored that loss of power affects ICU functions in virtually all ways. The number one tool Dr. King’s survey respondents said they’d depended on most during their disaster response was their flashlights (24%); meanwhile, the top two items the respondents said they wished they’d had on hand were reliable phones, since, as at Bellevue, many of their phones were powered by voice-over-Internet protocols which, for most, went down with power outages; and backup electricity sources such as generators.

Leadership plan

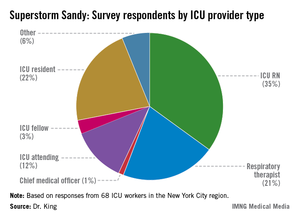

Of the 68 survey respondents, 34% of whom were in evacuation leadership roles, Dr. King said only 23% admitted to having felt ill prepared to manage the pressure and details necessary to safely evacuate their patients. "As nonemergency department hospital providers, we receive little to no training on how to evacuate patients," said Dr. King.

In Bellevue’s case, Dr. Evans said that there was a leadership contingency already in place because of the hospital’s having been prepared the year before, when Hurricane Irene muscled its way up the Northeast’s Atlantic coast, also causing flooding and wind damage, though on a far smaller scare. "We had an ad hoc committee," said Dr. Evans. "Although we didn’t know exactly who would be on it because we didn’t know who would be there during the storm, we knew we would have medical, nursing, and ethical leaders to make resource allocation decisions." Most important about the leadership committee’s makeup, she said, was that ultimately, "none of us were directly involved in patient care, so none of us had the responsibility for being advocates. We wanted the attending physicians to be able to advocate for their patients."

The committee discerned that if backup generators failed, the ICU would have only six power outlets to depend on for its almost 60 patients. "The question was, whom would they be allocated for out of the 56 patients?

"Our responsibility was to make the wisest decisions about allocating a scarce resource," Dr. Evans said.

Practice the plan

Dry runs matter. "Forty-seven percent of survey respondents said that patient triage criteria were determined at the time of [the storm]," and a third of those surveyed said they weren’t aware of any triage criteria, Dr. King said.

And once plans are made, "it’s important to drill them," emphasized Dr. King’s copresenter Dr. Colin Grissom, associate medical director of the shock trauma ICU at Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, Utah. Superstorm Sandy, for all its havoc, came with some notice – the weather forecast. However, he pointed out that typically disasters happen without warning: "More than half of all hospital evacuations occur as a result of an internal event such as a fire or an intruder."

Also important to consider, said Dr. King, is that neonatal and pediatric ICUs have different evacuation needs from adult ones. "Regions should consider stockpiling neonatal transport ventilators and circuits," she said. "They should also consider designating pediatric disaster receiving hospitals, similar to burn disaster receiving hospitals."

Ethical considerations

At Bellevue, Dr. Evans said the hospital’s leadership planned patient triage according to influenza pandemic guidelines issued by the provincial government of Ontario, Canada, and the New York State Taskforce on Life and the Law guidelines for ventilator allocation during a public health disaster.

"We knew that if the disaster went very badly, we would be met with much criticism," said Dr. Evans, who joked that she was up nights worried about seeing her name skewered in local headlines: "I kept wondering, ‘What rhymes with Evans?’ "

Using the two sets of guidelines, both heavily oriented toward allocating ventilators, said Dr. Evans, "we did what we thought was ethical and fair. We made the best decisions we could."

The Ontario guidelines, she said, are predicated on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores. Just as the ad hoc committee determined that of the 56 patients in the census, there were "far more folks in the red (highest priority) and yellow (immediate priority) group than we had power outlets," the group received word that the protective housing around the generator fuel pumps had failed, and total loss of power was anticipated in 2 hours.

The committee reconfigured and, among other contingencies, began assigning coverage of two providers each to the bedside of every ventilated patient, and preparing nurses to count drops per minute of continuous medication.

The ‘bucket brigade’

Although the intensivists who’d participated in Superstorm Sandy evacuations said they felt most frustrated by the lack of communication during the event, 57% said that teamwork had been essential to the success of the evacuations.

"We work as teams in our units. That is something I think we bring as a real strength to ICU evacuations," said Dr. King.

And so it was at Bellevue.

"Due to the heroics of a lot of staff and volunteers, we did not have to execute this plan," said Dr. Evans. Instead, the "Bellevue bucket brigade," using 5-gallon jugs, formed a relay team stretching from the ground floor outside where the fuel tanks were, up to the 13th, where the backup generators were located. "The fuel tank up on the 13th floor was only accessible by stepladder, so someone had to climb up there and pour the fuel through a funnel," said Dr. Evans. "But because of this, we never lost backup power, and we successfully evacuated our hospital without complications to our patients."

Individualized plan key to success

While leadership and communication were essential, said Dr. Evans, she concluded that thinking through how existing guidelines can help was also key, but did not go far enough. "Unfortunately, no document can provide for all contingencies. Complete reliance on any [guidelines] is not good. You have to think about how you would individualize things to your own facility."

The survey was sponsored by the ACCP and conducted by Dr. King as part of her role on the ACCP’s mass critical care task force evacuation panel, which will issue a consensus on the topic sometime in early 2014.

Dr. Evans, Dr. King, and Dr. Grissom reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Ten keys to ICU evacuation plan

When not under immediate threat

1) Create transport and other agreements with other facilities in region, including triage criteria.

2) Detail ICU evacuation plan, including vertical evacuation plan; simulate so all parties are familiar with their role, including those involved in patient transport.

3) Designate critical care leadership.

During imminent threat

4) Request assistance from regional facilities and appropriate agencies.

5) Ensure power and transportation resources are operable and in place.

6) Prioritize patients for evacuation.

During evacuation

7) Triage patients.

8) Include all patient information with patient.

9) Transport patients.

10) Track patients and all equipment.

Source: Dr. Colin Grissom

*This story has been updated 11/26/13

Dr. W. Michael Alberts, FCCP, comments: To paraphrase an old saying about insurance, "disaster preparedness is not needed until it is." Those health care facilities that have a clear documented plan and have drilled on the specifics are very pleased that they devoted time and effort when disaster strikes. While – knock on wood – the Moffitt Cancer Center here in Tampa has not needed our "Disaster Management Plan" (or as we in Florida say "Hurricane Management Plan") this year, it is only a matter of time and we’ll be ready when the need arises.

We urge you to review your plan before you need it.

Dr. W. Michael Alberts is chief medical officer, Moffitt Cancer Center, and professor of oncology and medicine at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

Dr. W. Michael Alberts, FCCP, comments: To paraphrase an old saying about insurance, "disaster preparedness is not needed until it is." Those health care facilities that have a clear documented plan and have drilled on the specifics are very pleased that they devoted time and effort when disaster strikes. While – knock on wood – the Moffitt Cancer Center here in Tampa has not needed our "Disaster Management Plan" (or as we in Florida say "Hurricane Management Plan") this year, it is only a matter of time and we’ll be ready when the need arises.

We urge you to review your plan before you need it.

Dr. W. Michael Alberts is chief medical officer, Moffitt Cancer Center, and professor of oncology and medicine at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

Dr. W. Michael Alberts, FCCP, comments: To paraphrase an old saying about insurance, "disaster preparedness is not needed until it is." Those health care facilities that have a clear documented plan and have drilled on the specifics are very pleased that they devoted time and effort when disaster strikes. While – knock on wood – the Moffitt Cancer Center here in Tampa has not needed our "Disaster Management Plan" (or as we in Florida say "Hurricane Management Plan") this year, it is only a matter of time and we’ll be ready when the need arises.

We urge you to review your plan before you need it.

Dr. W. Michael Alberts is chief medical officer, Moffitt Cancer Center, and professor of oncology and medicine at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

CHICAGO – When Superstorm Sandy was done barreling across New York City and the surrounding coast 14 months ago, flooding streets and knocking out power to millions, Dr. Laura Evans, director of the medical intensive care unit at Bellevue Hospital along the East River in Manhattan, emerged weary and wiser.

At one point, the ICU faced the real possibility of having just a handful of working power outlets to serve dozens of patients, and the number of crucial decisions to be made rose along with the water level. "Prior to the storm, disaster preparedness was not a core interest of mine, and it’s something I hope never to repeat," Dr. Evans told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In a recent survey, ICU practitioners who endured havoc caused by Sandy in the New York City region reported having had little to no training in emergency evacuation care. "When I look at these data, I think there is a mismatch in terms of our self-perception of readiness compared to what patients actually require in an evacuation. It’s in stark contrast to the checklist we use every single day to put in a central venous catheter," said Dr. Mary Alice King, who presented her research as a copanelist with Dr. Evans. Dr. King is medical director of the pediatric trauma ICU at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Contingency for loss of power

The nation’s oldest public hospital, Bellevue is adjacent to New York’s tidal East River. The river’s high tide the evening of Oct. 29, 2012, coincided with the arrival of the storm’s surge, and within minutes the hospital’s basement was inundated with 10 million gallons of seawater. And then the main power went out, taking with it the use of 32 elevators, the entire voice-over-Internet-protocol phone system, and the electronic medical records system, Dr. Evans said. The flood also knocked out the hospital’s ability to connect to its Internet servers. "We had very impaired means of communication," Dr. Evans said.

Survey data presented by Dr. King underscored that loss of power affects ICU functions in virtually all ways. The number one tool Dr. King’s survey respondents said they’d depended on most during their disaster response was their flashlights (24%); meanwhile, the top two items the respondents said they wished they’d had on hand were reliable phones, since, as at Bellevue, many of their phones were powered by voice-over-Internet protocols which, for most, went down with power outages; and backup electricity sources such as generators.

Leadership plan

Of the 68 survey respondents, 34% of whom were in evacuation leadership roles, Dr. King said only 23% admitted to having felt ill prepared to manage the pressure and details necessary to safely evacuate their patients. "As nonemergency department hospital providers, we receive little to no training on how to evacuate patients," said Dr. King.

In Bellevue’s case, Dr. Evans said that there was a leadership contingency already in place because of the hospital’s having been prepared the year before, when Hurricane Irene muscled its way up the Northeast’s Atlantic coast, also causing flooding and wind damage, though on a far smaller scare. "We had an ad hoc committee," said Dr. Evans. "Although we didn’t know exactly who would be on it because we didn’t know who would be there during the storm, we knew we would have medical, nursing, and ethical leaders to make resource allocation decisions." Most important about the leadership committee’s makeup, she said, was that ultimately, "none of us were directly involved in patient care, so none of us had the responsibility for being advocates. We wanted the attending physicians to be able to advocate for their patients."

The committee discerned that if backup generators failed, the ICU would have only six power outlets to depend on for its almost 60 patients. "The question was, whom would they be allocated for out of the 56 patients?

"Our responsibility was to make the wisest decisions about allocating a scarce resource," Dr. Evans said.

Practice the plan

Dry runs matter. "Forty-seven percent of survey respondents said that patient triage criteria were determined at the time of [the storm]," and a third of those surveyed said they weren’t aware of any triage criteria, Dr. King said.

And once plans are made, "it’s important to drill them," emphasized Dr. King’s copresenter Dr. Colin Grissom, associate medical director of the shock trauma ICU at Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, Utah. Superstorm Sandy, for all its havoc, came with some notice – the weather forecast. However, he pointed out that typically disasters happen without warning: "More than half of all hospital evacuations occur as a result of an internal event such as a fire or an intruder."

Also important to consider, said Dr. King, is that neonatal and pediatric ICUs have different evacuation needs from adult ones. "Regions should consider stockpiling neonatal transport ventilators and circuits," she said. "They should also consider designating pediatric disaster receiving hospitals, similar to burn disaster receiving hospitals."

Ethical considerations

At Bellevue, Dr. Evans said the hospital’s leadership planned patient triage according to influenza pandemic guidelines issued by the provincial government of Ontario, Canada, and the New York State Taskforce on Life and the Law guidelines for ventilator allocation during a public health disaster.

"We knew that if the disaster went very badly, we would be met with much criticism," said Dr. Evans, who joked that she was up nights worried about seeing her name skewered in local headlines: "I kept wondering, ‘What rhymes with Evans?’ "

Using the two sets of guidelines, both heavily oriented toward allocating ventilators, said Dr. Evans, "we did what we thought was ethical and fair. We made the best decisions we could."

The Ontario guidelines, she said, are predicated on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores. Just as the ad hoc committee determined that of the 56 patients in the census, there were "far more folks in the red (highest priority) and yellow (immediate priority) group than we had power outlets," the group received word that the protective housing around the generator fuel pumps had failed, and total loss of power was anticipated in 2 hours.

The committee reconfigured and, among other contingencies, began assigning coverage of two providers each to the bedside of every ventilated patient, and preparing nurses to count drops per minute of continuous medication.

The ‘bucket brigade’

Although the intensivists who’d participated in Superstorm Sandy evacuations said they felt most frustrated by the lack of communication during the event, 57% said that teamwork had been essential to the success of the evacuations.

"We work as teams in our units. That is something I think we bring as a real strength to ICU evacuations," said Dr. King.

And so it was at Bellevue.

"Due to the heroics of a lot of staff and volunteers, we did not have to execute this plan," said Dr. Evans. Instead, the "Bellevue bucket brigade," using 5-gallon jugs, formed a relay team stretching from the ground floor outside where the fuel tanks were, up to the 13th, where the backup generators were located. "The fuel tank up on the 13th floor was only accessible by stepladder, so someone had to climb up there and pour the fuel through a funnel," said Dr. Evans. "But because of this, we never lost backup power, and we successfully evacuated our hospital without complications to our patients."

Individualized plan key to success

While leadership and communication were essential, said Dr. Evans, she concluded that thinking through how existing guidelines can help was also key, but did not go far enough. "Unfortunately, no document can provide for all contingencies. Complete reliance on any [guidelines] is not good. You have to think about how you would individualize things to your own facility."

The survey was sponsored by the ACCP and conducted by Dr. King as part of her role on the ACCP’s mass critical care task force evacuation panel, which will issue a consensus on the topic sometime in early 2014.

Dr. Evans, Dr. King, and Dr. Grissom reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Ten keys to ICU evacuation plan

When not under immediate threat

1) Create transport and other agreements with other facilities in region, including triage criteria.

2) Detail ICU evacuation plan, including vertical evacuation plan; simulate so all parties are familiar with their role, including those involved in patient transport.

3) Designate critical care leadership.

During imminent threat

4) Request assistance from regional facilities and appropriate agencies.

5) Ensure power and transportation resources are operable and in place.

6) Prioritize patients for evacuation.

During evacuation

7) Triage patients.

8) Include all patient information with patient.

9) Transport patients.

10) Track patients and all equipment.

Source: Dr. Colin Grissom

*This story has been updated 11/26/13

CHICAGO – When Superstorm Sandy was done barreling across New York City and the surrounding coast 14 months ago, flooding streets and knocking out power to millions, Dr. Laura Evans, director of the medical intensive care unit at Bellevue Hospital along the East River in Manhattan, emerged weary and wiser.

At one point, the ICU faced the real possibility of having just a handful of working power outlets to serve dozens of patients, and the number of crucial decisions to be made rose along with the water level. "Prior to the storm, disaster preparedness was not a core interest of mine, and it’s something I hope never to repeat," Dr. Evans told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In a recent survey, ICU practitioners who endured havoc caused by Sandy in the New York City region reported having had little to no training in emergency evacuation care. "When I look at these data, I think there is a mismatch in terms of our self-perception of readiness compared to what patients actually require in an evacuation. It’s in stark contrast to the checklist we use every single day to put in a central venous catheter," said Dr. Mary Alice King, who presented her research as a copanelist with Dr. Evans. Dr. King is medical director of the pediatric trauma ICU at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

Contingency for loss of power

The nation’s oldest public hospital, Bellevue is adjacent to New York’s tidal East River. The river’s high tide the evening of Oct. 29, 2012, coincided with the arrival of the storm’s surge, and within minutes the hospital’s basement was inundated with 10 million gallons of seawater. And then the main power went out, taking with it the use of 32 elevators, the entire voice-over-Internet-protocol phone system, and the electronic medical records system, Dr. Evans said. The flood also knocked out the hospital’s ability to connect to its Internet servers. "We had very impaired means of communication," Dr. Evans said.

Survey data presented by Dr. King underscored that loss of power affects ICU functions in virtually all ways. The number one tool Dr. King’s survey respondents said they’d depended on most during their disaster response was their flashlights (24%); meanwhile, the top two items the respondents said they wished they’d had on hand were reliable phones, since, as at Bellevue, many of their phones were powered by voice-over-Internet protocols which, for most, went down with power outages; and backup electricity sources such as generators.

Leadership plan

Of the 68 survey respondents, 34% of whom were in evacuation leadership roles, Dr. King said only 23% admitted to having felt ill prepared to manage the pressure and details necessary to safely evacuate their patients. "As nonemergency department hospital providers, we receive little to no training on how to evacuate patients," said Dr. King.

In Bellevue’s case, Dr. Evans said that there was a leadership contingency already in place because of the hospital’s having been prepared the year before, when Hurricane Irene muscled its way up the Northeast’s Atlantic coast, also causing flooding and wind damage, though on a far smaller scare. "We had an ad hoc committee," said Dr. Evans. "Although we didn’t know exactly who would be on it because we didn’t know who would be there during the storm, we knew we would have medical, nursing, and ethical leaders to make resource allocation decisions." Most important about the leadership committee’s makeup, she said, was that ultimately, "none of us were directly involved in patient care, so none of us had the responsibility for being advocates. We wanted the attending physicians to be able to advocate for their patients."

The committee discerned that if backup generators failed, the ICU would have only six power outlets to depend on for its almost 60 patients. "The question was, whom would they be allocated for out of the 56 patients?

"Our responsibility was to make the wisest decisions about allocating a scarce resource," Dr. Evans said.

Practice the plan

Dry runs matter. "Forty-seven percent of survey respondents said that patient triage criteria were determined at the time of [the storm]," and a third of those surveyed said they weren’t aware of any triage criteria, Dr. King said.

And once plans are made, "it’s important to drill them," emphasized Dr. King’s copresenter Dr. Colin Grissom, associate medical director of the shock trauma ICU at Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, Utah. Superstorm Sandy, for all its havoc, came with some notice – the weather forecast. However, he pointed out that typically disasters happen without warning: "More than half of all hospital evacuations occur as a result of an internal event such as a fire or an intruder."

Also important to consider, said Dr. King, is that neonatal and pediatric ICUs have different evacuation needs from adult ones. "Regions should consider stockpiling neonatal transport ventilators and circuits," she said. "They should also consider designating pediatric disaster receiving hospitals, similar to burn disaster receiving hospitals."

Ethical considerations

At Bellevue, Dr. Evans said the hospital’s leadership planned patient triage according to influenza pandemic guidelines issued by the provincial government of Ontario, Canada, and the New York State Taskforce on Life and the Law guidelines for ventilator allocation during a public health disaster.

"We knew that if the disaster went very badly, we would be met with much criticism," said Dr. Evans, who joked that she was up nights worried about seeing her name skewered in local headlines: "I kept wondering, ‘What rhymes with Evans?’ "

Using the two sets of guidelines, both heavily oriented toward allocating ventilators, said Dr. Evans, "we did what we thought was ethical and fair. We made the best decisions we could."

The Ontario guidelines, she said, are predicated on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores. Just as the ad hoc committee determined that of the 56 patients in the census, there were "far more folks in the red (highest priority) and yellow (immediate priority) group than we had power outlets," the group received word that the protective housing around the generator fuel pumps had failed, and total loss of power was anticipated in 2 hours.

The committee reconfigured and, among other contingencies, began assigning coverage of two providers each to the bedside of every ventilated patient, and preparing nurses to count drops per minute of continuous medication.

The ‘bucket brigade’

Although the intensivists who’d participated in Superstorm Sandy evacuations said they felt most frustrated by the lack of communication during the event, 57% said that teamwork had been essential to the success of the evacuations.

"We work as teams in our units. That is something I think we bring as a real strength to ICU evacuations," said Dr. King.

And so it was at Bellevue.

"Due to the heroics of a lot of staff and volunteers, we did not have to execute this plan," said Dr. Evans. Instead, the "Bellevue bucket brigade," using 5-gallon jugs, formed a relay team stretching from the ground floor outside where the fuel tanks were, up to the 13th, where the backup generators were located. "The fuel tank up on the 13th floor was only accessible by stepladder, so someone had to climb up there and pour the fuel through a funnel," said Dr. Evans. "But because of this, we never lost backup power, and we successfully evacuated our hospital without complications to our patients."

Individualized plan key to success

While leadership and communication were essential, said Dr. Evans, she concluded that thinking through how existing guidelines can help was also key, but did not go far enough. "Unfortunately, no document can provide for all contingencies. Complete reliance on any [guidelines] is not good. You have to think about how you would individualize things to your own facility."

The survey was sponsored by the ACCP and conducted by Dr. King as part of her role on the ACCP’s mass critical care task force evacuation panel, which will issue a consensus on the topic sometime in early 2014.

Dr. Evans, Dr. King, and Dr. Grissom reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Ten keys to ICU evacuation plan

When not under immediate threat

1) Create transport and other agreements with other facilities in region, including triage criteria.

2) Detail ICU evacuation plan, including vertical evacuation plan; simulate so all parties are familiar with their role, including those involved in patient transport.

3) Designate critical care leadership.

During imminent threat

4) Request assistance from regional facilities and appropriate agencies.

5) Ensure power and transportation resources are operable and in place.

6) Prioritize patients for evacuation.

During evacuation

7) Triage patients.

8) Include all patient information with patient.

9) Transport patients.

10) Track patients and all equipment.

Source: Dr. Colin Grissom

*This story has been updated 11/26/13

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CHEST 2013

Major finding: Although 78% of ICU staff had never performed a vertical ICU evacuation drill, only 23% admitted to feeling "inadequately trained" during Superstorm Sandy evacuations.

Data source: Survey of 68 ICU workers in the New York City region, all of whom worked through Superstorm Sandy.

Disclosures: Dr. Evans, Dr. King, and Dr. Grissom reported no relevant financial disclosures.