User login

Mr. C, age 34, presented to the emergency department with his wife because of increasingly bizarre behavior. He reported auditory and visual hallucinations, and believed that the “mob had ordered a hit” against him. He had threatened to shoot his wife and children, which led to his arrest and being briefly jailed. In jail, he was agitated, defecated on the floor, and disrobed. His wife reported that Mr. C had a long history of bipolar disorder and had experienced his first manic episode and hospitalization at age 17. Since then, he had been treated with many different antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers.

Mr. C was admitted to the hospital, where he developed a catatonic syndrome that was treated with a course of electroconvulsive therapy. He was eventually stabilized with

Over the next 8 years, Mr. C was often noncompliant with medication and frequently was hospitalized for mania. His symptoms included poor sleep, grandiosity, pressured speech, racing and disorganized thoughts, increased risk-taking behavior (ie, driving at excessive speeds), and hyperreligiosity (ie, speaking with God). Mr. C also occasionally used methamphetamine, cannabis, and cocaine. Although he had responded well to treatment early in the course of his illness, as he entered his late 30s, his response was less complete, and by his 40s, Mr. C was no longer able to function independently. He eventually was prescribed a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, paliperidone palmitate, 156 mg monthly. Eventually, his family was no longer able to care for him at home, so he was admitted to a residential care facility.

In this facility, based on the long-standing nature of Mr. C’s psychotic disorder and frequency with which he presented with mania, his clinicians changed his diagnosis to schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. It had become clear that mood symptoms comprised >50% of the total duration of his illness.

Schizoaffective disorder (SAD) often has been used as a diagnosis for patients who have an admixture of mood and psychotic symptoms whose diagnosis is uncertain. Its hallmark is the presence of symptoms of a major mood episode (either a depressive or manic episode) concurrent with symptoms characteristic of schizophrenia, such as delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech.1

SAD is a controversial diagnosis. There has been inadequate research regarding the epidemiology, course, etiologic factors, and treatment of this disorder. Debate continues to swirl around its conceptualization; some experts view SAD as an independent disorder, while others see SAD as either a form of schizophrenia or a mood disorder.1 In this review, we describe the classification of SAD and its features, diagnosis, and treatment.

An evolving diagnosis

The term schizoaffective was first used by Jacob Kasanin, MD, in 1933.2 He described 9 patients with “acute schizoaffective psychoses,” each of whom had an abrupt onset. The term was used in the first edition of the DSM as a subtype of schizophrenia.3 In DSM-I, the “schizo-affective type” was defined as a diagnosis for patients with a “significant admixture of schizophrenic and affective reactions.”3 Diagnostic criteria for SAD were developed for DSM-III-R, published in 1987.4 These criteria continued to evolve with subsequent editions of the DSM.

Continue to: DSM-5 provides...

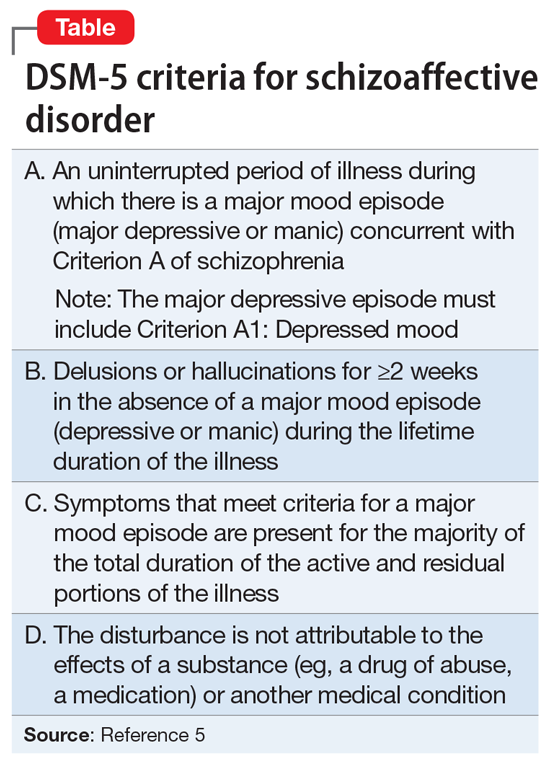

DSM-5 provides a clearer separation between schizophrenia with mood symptoms, bipolar disorder, and SAD (Table5). In addition, DSM-5 shifts away from the DSM-IV diagnosis of SAD as an episode, and instead focuses more on the longitudinal course of the illness. It has been suggested that this change will likely lead to reduced rates of diagnosis of SAD.6 Despite improvements in classification, the diagnosis remains controversial (Box7-11).

Box 1

Despite improvements in classification, controversy continues to swirl around the question of whether schizoaffective disorder (SAD) represents an independent disorder that stands apart from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, whether it is a form of schizophrenia, or whether it is a form of bipolar disorder or a depressive disorder.7,8 Other possibilities are that SAD is heterogeneous or that it represents a middle point on a spectrum that bridges mood and psychotic disorders. While the merits of each possibility are beyond the scope of this review, it is safe to say that each possibility has its proponents. For these reasons, some argue that the concept itself lacks validity and shows the pitfalls of our classification system.7

Poor diagnostic reliability is one reason for concerns about validity. Most recently, a field trial using DSM-5 criteria produced a kappa of 0.50, which is moderate,9 but earlier definitions produced relatively poor results. Wilson et al10 point out that Criterion C, which concerns duration of mood symptoms, produces a particularly low kappa. Another reason is diagnostic switching, whereby patients initially diagnosed with 1 disorder receive a different diagnosis at followup. Diagnostic switching is especially problematic for SAD. In a large meta-analysis by Santelmann et al,11 36% of patients initially diagnosed with SAD had their diagnosis changed when reassessed. This diagnostic shift tended more toward schizophrenia than bipolar disorder. In addition, more than one-half of all patients initially diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder were re-diagnosed with SAD when reassessed.

DSM-5 subtypes and specifiers

In DSM-5,SAD has 2 subtypes5:

- Bipolar type. The bipolar type is marked by the presence of a manic episode (major depressive episodes may also occur)

- Depressive type. The depressive type is marked by the presence of only major depressive episodes.

SAD also includes several specifiers, with the express purpose of giving clinicians greater descriptive ability. The course of SAD can be described as either “first episode,” defined as the first manifestation of the disorder, or as having “multiple episodes,” defined as a minimum of 2 episodes with 1 relapse. In addition, SAD can be described as an acute episode, in partial remission, or in full remission. The course can be described as “continuous” if it is clear that symptoms have been present for the majority of the illness with very brief subthreshold periods. The course is designated as “unspecified” when information is unavailable or lacking. The 5-point Clinician-Rated Dimensions of Psychosis Symptoms was introduced to enable clinicians to make a quantitative assessment of the psychotic symptoms, although its use is not required.

Epidemiology and gender ratio

The epidemiology of SAD has not been well studied. DSM-5 estimates that SAD is approximately one-third as common as schizophrenia, which has a lifetime prevalence of 0.5% to 0.8%.5 This is similar to an estimate by Perälä et al12 of a 0.32% lifetime prevalence based on a nationally representative sample of persons in Finland age ≥30. Scully et al13 calculated a prevalence estimate of 1.1% in a representative sample of adults in rural Ireland. Based on pooled clinical data, Keck et al14 estimated the prevalence in clinical settings at 16%, similar to the figure of 19% reported by Levinson et al15 based on data from New York State psychiatric hospitals. In clinical practice, the diagnosis of SAD is used frequently when there is diagnostic uncertainty, which potentially inflates estimates of lifetime prevalence.

The prevalence of SAD is higher in women than men, with a sex ratio of about 2:1, similar to that seen in mood disorders.13,16-19 There are an equal number of men and women with the bipolar subtype, but a female preponderance with the depressive subtype.5 The bipolar subtype is more common in younger patients, while the depressive subtype is more common in older patients. SAD is a rare diagnosis in children.20

Continue to: Course and outcome

Course and outcome

The onset of SAD typically occurs in early adulthood, but can range from childhood to senescence. Approximately one-third of patients are diagnosed before age 25, one-third between age 25 and 35, and one-third after age 35.21-23 Based on a literature review, Cheniaux et al7 concluded that that age at onset for patients with SAD is between those with schizophrenia and those with mood disorders.

The course of SAD is variable but represents a middle ground between that of schizophrenia and the mood disorders. In a 4- to 5-year follow-up,24 patients with SAD had a better overall course than patients with schizophrenia but had poorer functioning than those with bipolar mania, and much poorer than those with unipolar depression. Mood-incongruent psychotic features predict a particularly worse outcome. These findings were reaffirmed at a 10-year follow-up.25 Mood symptoms portend a better outcome than do symptoms of schizophrenia.

The lifetime suicide risk for patients with SAD is estimated at 5%, with a higher risk associated with the presence of depressive symptoms.26 One study found that women with SAD had a 17.5-year reduced life expectancy (64.1 years) compared with a reduction of 8.0 years for men (69.4 years).27

Comorbidity

Patients with SAD are commonly diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders, including anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders.21,28,29 When compared with the general population, patients with SAD are at higher risk for coronary heart disease, stroke, obesity, and smoking, likely contributing to their decreased life expectancy.27,30 Because second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are often used to treat SAD, patients with SAD are at risk for metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus.30

Clinical assessment

Because there are no diagnostic, laboratory, or neuroimaging tests for SAD, the most important basis for making the diagnosis is the patient’s history, supplemented by collateral history from family members or friends, and medical records. Determining the percentage of time spent in a mood episode (DSM-5 Criterion C) is especially important.31 This requires the clinician to pay close attention to the temporal relationship of psychotic and mood symptoms.

Continue to: Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for SAD is broad because it includes all of the possibilities usually considered for major mood disorders and for psychotic disorders5:

- schizophrenia

- bipolar disorder with psychotic features

- major depressive disorder with psychotic features

- depressive or bipolar disorders with catatonic features

- personality disorders (especially the schizotypal, paranoid, and borderline types)

- major neurocognitive disorders in which there are mood and psychotic symptoms

- substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder

- disorders induced by medical conditions.

With schizophrenia, the duration of all episodes of a mood syndrome is brief (<50% of the total duration of the illness) relative to the duration of the psychotic symptoms. Although psychotic symptoms may occur in persons with mood disorders, they are generally not present in the absence of depression or mania, helping to set the boundary between SAD and psychotic mania or depression. As for personality disorders, the individual will not have a true psychosis, although some symptoms, such as feelings of unreality, paranoia, or magical thinking, may cause diagnostic confusion.

Medical conditions also can present with psychotic and mood symptoms and need to be ruled out. These include psychotic disorder due to another medical condition, and delirium. A thorough medical workup should be performed to rule out any possible medical causes for the symptoms.

Substance use should also be ruled out as the cause of the symptoms because many substances are associated with mood and psychotic symptoms. It is usually clear from the history, physical examination, or laboratory tests when a medication/illicit substance has initiated and maintained the disorder.

Neurologic conditions. If a neurologic condition is suspected, a neurologic evaluation may be warranted, including laboratory tests, brain imaging to identify specific anatomical abnormalities, lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and an electroencephalogram to rule out a convulsive disorder.

Continue to: Clinical symptoms

Clinical symptoms

The signs and symptoms of SAD include those typically seen in schizophrenia and the mood disorders. Thus, the patient may exhibit elated mood and/or grandiosity, or severe depression, combined with mood-incongruent psychotic features such as paranoid delusions. The symptoms may present together or in an alternating fashion, and psychotic symptoms may be mood-congruent or mood-incongruent. Mr. C’s case illustrates some of the symptoms of the disorder.

Brain imaging

Significant changes have been reported to occur in the brain structure and function in persons with SAD. Neuroimaging studies using voxel-based morphometry have shown significant reductions in gray matter volume in several areas of the brain, including the medial prefrontal cortex, insula, Rolandic operculum, parts of the temporal lobe, and the hippocampus.32-35 Amann et al32 found that patients with SAD and schizophrenia had widespread and overlapping areas of significant volume reduction, but patients with bipolar disorder did not. These studies suggest that at least from a neuroimaging standpoint, SAD is more closely related to schizophrenia than bipolar disorder, and could represent a variant of schizophrenia.

Treatment of SAD

The pharmacotherapy of SAD is mostly empirical because of the lack of randomized controlled trials. Clinicians have traditionally prescribed an antipsychotic agent along with either a mood stabilizer (eg,

Since that exhaustive review,

Patients with SAD will require maintenance treatment for ongoing symptom control. Medication that is effective for treatment of an acute episode should be considered for maintenance treatment. Both the extended-release and long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of paliperidone have been shown to be efficacious in the maintenance treatment of patients with SAD.40 The LAI form of paliperidone significantly delayed psychotic, depressive, and manic relapses, improved clinical rating scale scores, and increased medication adherence.41,42 In an open-label study, olanzapine LAI was effective in long-term maintenance treatment, although approximately 40% of patients experienced significant weight gain.43 One concern with olanzapine is the possible occurrence of a post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome. For that reason, patients receiving olanzapine must be monitored for at least 3 hours post-injection. The paliperidone LAI does not require monitoring after injection.

Continue to: There is a single clinical trial...

There is a single clinical trial showing that patients with SAD can be successfully switched from other antipsychotics to

Other approaches

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) should be considered for patients with SAD who are acutely ill and have failed to respond adequately to medication. ECT is especially relevant in the setting of acute mood symptoms (ie, depressive or manic symptoms co-occurring with psychosis or in the absence of psychosis).45

As currently conceptualized, the diagnosis of SAD is made in persons having an admixture of mood and psychotic symptoms, although by definition mood symptoms must take up the majority (≥50%) of the total duration of the illness. Unfortunately, SAD has been inadequately researched due to the unreliability of its definition and concerns about its validity. The long-term course of SAD is midway between mood and psychotic disorders, and the disorder can cause significant disability.

Bottom Line

Schizoaffective disorder (SAD) is characterized by the presence of symptoms of a major mood episode (a depressive or manic episode) concurrent with symptoms of schizophrenia. The most important basis for establishing the diagnosis is the patient’s history. Determining the percentage of time spent in a mood episode is especially important. Treatment usually consists of an antipsychotic plus a mood stabilizer or antidepressant. Electroconvulsive therapy is an option for patients with SAD who do not respond well to medication.

Related Resources

- Wy TJP, Saadabadi A. Schizoaffective disorder. NCBI Bookshelf: StatPearls Publishing. Published January 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541012/. Updated April 15, 2020.

- Parker G. How well does the DSM-5 capture schizoaffective disorder? Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(9):607-610.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine long-acting injectable • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega sustenna

Valproate • Depacon

1. Miller JN, Black DW. Schizoaffective disorder: a review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2019;31(1):47-53.

2. Kasanin J. The acute schizoaffective psychoses. Am J Psychiatry. 1933;90:97-126.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd ed, revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Malaspina D, Owen M, Heckers S, et al. Schizoaffective disorder in the DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:21-25.

7. Cheniaux E, Landeria-Fernandez J, Telles LL, et al. Does schizoaffective disorder really exist? A systematic review of the studies that compared schizoaffective disorder with schizophrenia or mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:209-217.

8. Kantrowitz JT, Citrome L. Schizoaffective disorder: a review of current research themes and pharmacologic management. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:317-331.

9. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE, et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: test-retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:59-70.

10. Wilson JE, Nian H, Heckers S. The schizoaffective disorder diagnosis: a conundrum in the clinical setting. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:29-34.

11. Santelmann H, Franklin J, Bußhoff J, Baethge C. Test-retest reliability of schizoaffective disorder compared with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depression--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:753-768.

12. Perälä J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, et al. Lifetime Prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2007;64:19-28.

13. Scully PJ, Owens JM, Kinsella A, et al. Schizophrenia, schizoaffective and bipolar disorder within an epidemiologically complete, homogeneous population in rural Ireland: small area variation in rate. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:143-155.

14. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SE, Strakowski SM, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Psychopharmacol. 1994;114:529-538.

15. Levinson DF, Umapathy C, Musthaq M. Treatment of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia with mood symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1138-1148.

16. Angst J, Felder W, Lohmeyer B. Course of schizoaffective psychoses: results of a follow-up study. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6:579-585.

17. Lenz G, Simhandl C, Thau K, et al. Temporal stability of diagnostic criteria for functional psychoses. Psychopathol. 1991;24:328-335.

18. Malhi GS, Green M, Fagiolini A, et al. Schizoaffective disorder: diagnostic issues and future recommendations. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:215-230.

19. Marneros A, Deister A, Rohde A. Psychopathological and social status of patients with affective, schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders after long‐term course. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82:352-358.

20. Werry JS, McClellan JM, Chard L. Childhood and adolescent schizophrenic, bipolar, and schizoaffective disorders: a clinical and outcome study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:457-465.

21. Abrams DJ, Rojas DC, Arciniegas DB. Is schizoaffective disorder a distinct categorical diagnosis? A critical review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:1089-1109.

22. Bromet EJ, Kotov R, Fochtmann LJ, et al. Diagnostic shifts during the decade following first admission for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1186-1194.

23. Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, et al. The McLean-Harvard First Episode Project: two-year stability of DSM-IV diagnoses in 500 first-episode psychotic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:458-466.

24. Grossman LS, Harrow M, Goldberg JF, et al. Outcome of schizoaffective disorder at two long term follow-ups: comparisons with outcome of schizophrenia and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1359-1365.

25. Harrow M, Grossman L, Herbener E, et al. Ten-year outcome: patients with schizoaffective disorders, schizophrenia, affective disorders and mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:421-426.

26. Hor K, Taylor M. Review: suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:81-90.

27. Chang CK, Hayes RD, Perera G, et al. Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19590.

28. Byerly M, Goodman W, Acholonu W, et al. Obsessive compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia: frequency and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2005;76:309-316.

29. Strauss JL, Calhoun PS, Marx CE, et al. Comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with suicidality in male veterans with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2006;84:165-169.

30. Fagiolini A, Goracci A. The effects of undertreated chronic medical illnesses in patients with severe mental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:22-29.

31. Black DW, Grant JE. DSM-5 guidebook: the essential companion to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014.

32. Amann BL, Canales-Rodríguez EJ, Madre M, et al. Brain structural changes in schizoaffective disorder compared to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133:23-33.

33. Ivleva EI, Bidesi AS, Keshavan MS, et al. Gray matter volume as an intermediate phenotype for psychosis: Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP). Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1285-1296.

34. Ivleva EI, Bidesi AS, Thomas BP, et al. Brain gray matter phenotypes across the psychosis dimension. Psychiatry Res. 2012;204:13-24.

35. Radonic

36. Jäger M, Becker T, Weinmann S, et al. Treatment of schizoaffective disorder - a challenge for evidence-based psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:22-32.

37. Glick ID, Mankosli R, Eudicone JM, et al. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of aripiprazole for the treatment of schizoaffective disorder: results from a pooled analysis of a sub-population of subjects from two randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, pivotal trials. J Affect Disord. 2009;115:18-26.

38. Canuso CM, Lindenmayer JP, Kosik-Gonzalez C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study of 2 dose ranges of paliperidone extended-release in the treatment of subjects with schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:587-598.

39. Canuso CM, Schooler NR, Carothers J, et al. Paliperidone extended-release in schizoaffective disorder: a randomized controlled trial comparing a flexible-dose with placebo in patients treated with and without antidepressants and/or mood stabilizers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:487-495.

40. Lindenmayer JP, Kaur A. Antipsychotic management of schizoaffective disorder: a review. Drugs. 2016;76:589-604.

41. Alphs L, Fu DJ, Turkoz I. Paliperidone for the treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;176:871-883.

42. Bossie CA, Turkoz I, Alphs L, et al. Paliperidone palmitate once-monthly treatment in recent onset and chronic illness patients with schizoaffective disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205:324-328.

43. McDonnell DP, Landry J, Detke HC. Long-term safety and efficacy of olanzapine long-acting injection in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a 6-year, multinational, single-arm, open-label study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29:322-331.

44. McEvoy JP, Citrome L, Hernandez D, et al. Effectiveness of lurasidone in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder switched from other antipsychotics: a randomized, 6-week, open-label study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:170-179.

45. Mankad MV, Beyer JL, Wiener RD, et al. Manual of electroconvulsive therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2010.

Mr. C, age 34, presented to the emergency department with his wife because of increasingly bizarre behavior. He reported auditory and visual hallucinations, and believed that the “mob had ordered a hit” against him. He had threatened to shoot his wife and children, which led to his arrest and being briefly jailed. In jail, he was agitated, defecated on the floor, and disrobed. His wife reported that Mr. C had a long history of bipolar disorder and had experienced his first manic episode and hospitalization at age 17. Since then, he had been treated with many different antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers.

Mr. C was admitted to the hospital, where he developed a catatonic syndrome that was treated with a course of electroconvulsive therapy. He was eventually stabilized with

Over the next 8 years, Mr. C was often noncompliant with medication and frequently was hospitalized for mania. His symptoms included poor sleep, grandiosity, pressured speech, racing and disorganized thoughts, increased risk-taking behavior (ie, driving at excessive speeds), and hyperreligiosity (ie, speaking with God). Mr. C also occasionally used methamphetamine, cannabis, and cocaine. Although he had responded well to treatment early in the course of his illness, as he entered his late 30s, his response was less complete, and by his 40s, Mr. C was no longer able to function independently. He eventually was prescribed a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, paliperidone palmitate, 156 mg monthly. Eventually, his family was no longer able to care for him at home, so he was admitted to a residential care facility.

In this facility, based on the long-standing nature of Mr. C’s psychotic disorder and frequency with which he presented with mania, his clinicians changed his diagnosis to schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. It had become clear that mood symptoms comprised >50% of the total duration of his illness.

Schizoaffective disorder (SAD) often has been used as a diagnosis for patients who have an admixture of mood and psychotic symptoms whose diagnosis is uncertain. Its hallmark is the presence of symptoms of a major mood episode (either a depressive or manic episode) concurrent with symptoms characteristic of schizophrenia, such as delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech.1

SAD is a controversial diagnosis. There has been inadequate research regarding the epidemiology, course, etiologic factors, and treatment of this disorder. Debate continues to swirl around its conceptualization; some experts view SAD as an independent disorder, while others see SAD as either a form of schizophrenia or a mood disorder.1 In this review, we describe the classification of SAD and its features, diagnosis, and treatment.

An evolving diagnosis

The term schizoaffective was first used by Jacob Kasanin, MD, in 1933.2 He described 9 patients with “acute schizoaffective psychoses,” each of whom had an abrupt onset. The term was used in the first edition of the DSM as a subtype of schizophrenia.3 In DSM-I, the “schizo-affective type” was defined as a diagnosis for patients with a “significant admixture of schizophrenic and affective reactions.”3 Diagnostic criteria for SAD were developed for DSM-III-R, published in 1987.4 These criteria continued to evolve with subsequent editions of the DSM.

Continue to: DSM-5 provides...

DSM-5 provides a clearer separation between schizophrenia with mood symptoms, bipolar disorder, and SAD (Table5). In addition, DSM-5 shifts away from the DSM-IV diagnosis of SAD as an episode, and instead focuses more on the longitudinal course of the illness. It has been suggested that this change will likely lead to reduced rates of diagnosis of SAD.6 Despite improvements in classification, the diagnosis remains controversial (Box7-11).

Box 1

Despite improvements in classification, controversy continues to swirl around the question of whether schizoaffective disorder (SAD) represents an independent disorder that stands apart from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, whether it is a form of schizophrenia, or whether it is a form of bipolar disorder or a depressive disorder.7,8 Other possibilities are that SAD is heterogeneous or that it represents a middle point on a spectrum that bridges mood and psychotic disorders. While the merits of each possibility are beyond the scope of this review, it is safe to say that each possibility has its proponents. For these reasons, some argue that the concept itself lacks validity and shows the pitfalls of our classification system.7

Poor diagnostic reliability is one reason for concerns about validity. Most recently, a field trial using DSM-5 criteria produced a kappa of 0.50, which is moderate,9 but earlier definitions produced relatively poor results. Wilson et al10 point out that Criterion C, which concerns duration of mood symptoms, produces a particularly low kappa. Another reason is diagnostic switching, whereby patients initially diagnosed with 1 disorder receive a different diagnosis at followup. Diagnostic switching is especially problematic for SAD. In a large meta-analysis by Santelmann et al,11 36% of patients initially diagnosed with SAD had their diagnosis changed when reassessed. This diagnostic shift tended more toward schizophrenia than bipolar disorder. In addition, more than one-half of all patients initially diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder were re-diagnosed with SAD when reassessed.

DSM-5 subtypes and specifiers

In DSM-5,SAD has 2 subtypes5:

- Bipolar type. The bipolar type is marked by the presence of a manic episode (major depressive episodes may also occur)

- Depressive type. The depressive type is marked by the presence of only major depressive episodes.

SAD also includes several specifiers, with the express purpose of giving clinicians greater descriptive ability. The course of SAD can be described as either “first episode,” defined as the first manifestation of the disorder, or as having “multiple episodes,” defined as a minimum of 2 episodes with 1 relapse. In addition, SAD can be described as an acute episode, in partial remission, or in full remission. The course can be described as “continuous” if it is clear that symptoms have been present for the majority of the illness with very brief subthreshold periods. The course is designated as “unspecified” when information is unavailable or lacking. The 5-point Clinician-Rated Dimensions of Psychosis Symptoms was introduced to enable clinicians to make a quantitative assessment of the psychotic symptoms, although its use is not required.

Epidemiology and gender ratio

The epidemiology of SAD has not been well studied. DSM-5 estimates that SAD is approximately one-third as common as schizophrenia, which has a lifetime prevalence of 0.5% to 0.8%.5 This is similar to an estimate by Perälä et al12 of a 0.32% lifetime prevalence based on a nationally representative sample of persons in Finland age ≥30. Scully et al13 calculated a prevalence estimate of 1.1% in a representative sample of adults in rural Ireland. Based on pooled clinical data, Keck et al14 estimated the prevalence in clinical settings at 16%, similar to the figure of 19% reported by Levinson et al15 based on data from New York State psychiatric hospitals. In clinical practice, the diagnosis of SAD is used frequently when there is diagnostic uncertainty, which potentially inflates estimates of lifetime prevalence.

The prevalence of SAD is higher in women than men, with a sex ratio of about 2:1, similar to that seen in mood disorders.13,16-19 There are an equal number of men and women with the bipolar subtype, but a female preponderance with the depressive subtype.5 The bipolar subtype is more common in younger patients, while the depressive subtype is more common in older patients. SAD is a rare diagnosis in children.20

Continue to: Course and outcome

Course and outcome

The onset of SAD typically occurs in early adulthood, but can range from childhood to senescence. Approximately one-third of patients are diagnosed before age 25, one-third between age 25 and 35, and one-third after age 35.21-23 Based on a literature review, Cheniaux et al7 concluded that that age at onset for patients with SAD is between those with schizophrenia and those with mood disorders.

The course of SAD is variable but represents a middle ground between that of schizophrenia and the mood disorders. In a 4- to 5-year follow-up,24 patients with SAD had a better overall course than patients with schizophrenia but had poorer functioning than those with bipolar mania, and much poorer than those with unipolar depression. Mood-incongruent psychotic features predict a particularly worse outcome. These findings were reaffirmed at a 10-year follow-up.25 Mood symptoms portend a better outcome than do symptoms of schizophrenia.

The lifetime suicide risk for patients with SAD is estimated at 5%, with a higher risk associated with the presence of depressive symptoms.26 One study found that women with SAD had a 17.5-year reduced life expectancy (64.1 years) compared with a reduction of 8.0 years for men (69.4 years).27

Comorbidity

Patients with SAD are commonly diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders, including anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders.21,28,29 When compared with the general population, patients with SAD are at higher risk for coronary heart disease, stroke, obesity, and smoking, likely contributing to their decreased life expectancy.27,30 Because second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are often used to treat SAD, patients with SAD are at risk for metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus.30

Clinical assessment

Because there are no diagnostic, laboratory, or neuroimaging tests for SAD, the most important basis for making the diagnosis is the patient’s history, supplemented by collateral history from family members or friends, and medical records. Determining the percentage of time spent in a mood episode (DSM-5 Criterion C) is especially important.31 This requires the clinician to pay close attention to the temporal relationship of psychotic and mood symptoms.

Continue to: Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for SAD is broad because it includes all of the possibilities usually considered for major mood disorders and for psychotic disorders5:

- schizophrenia

- bipolar disorder with psychotic features

- major depressive disorder with psychotic features

- depressive or bipolar disorders with catatonic features

- personality disorders (especially the schizotypal, paranoid, and borderline types)

- major neurocognitive disorders in which there are mood and psychotic symptoms

- substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder

- disorders induced by medical conditions.

With schizophrenia, the duration of all episodes of a mood syndrome is brief (<50% of the total duration of the illness) relative to the duration of the psychotic symptoms. Although psychotic symptoms may occur in persons with mood disorders, they are generally not present in the absence of depression or mania, helping to set the boundary between SAD and psychotic mania or depression. As for personality disorders, the individual will not have a true psychosis, although some symptoms, such as feelings of unreality, paranoia, or magical thinking, may cause diagnostic confusion.

Medical conditions also can present with psychotic and mood symptoms and need to be ruled out. These include psychotic disorder due to another medical condition, and delirium. A thorough medical workup should be performed to rule out any possible medical causes for the symptoms.

Substance use should also be ruled out as the cause of the symptoms because many substances are associated with mood and psychotic symptoms. It is usually clear from the history, physical examination, or laboratory tests when a medication/illicit substance has initiated and maintained the disorder.

Neurologic conditions. If a neurologic condition is suspected, a neurologic evaluation may be warranted, including laboratory tests, brain imaging to identify specific anatomical abnormalities, lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and an electroencephalogram to rule out a convulsive disorder.

Continue to: Clinical symptoms

Clinical symptoms

The signs and symptoms of SAD include those typically seen in schizophrenia and the mood disorders. Thus, the patient may exhibit elated mood and/or grandiosity, or severe depression, combined with mood-incongruent psychotic features such as paranoid delusions. The symptoms may present together or in an alternating fashion, and psychotic symptoms may be mood-congruent or mood-incongruent. Mr. C’s case illustrates some of the symptoms of the disorder.

Brain imaging

Significant changes have been reported to occur in the brain structure and function in persons with SAD. Neuroimaging studies using voxel-based morphometry have shown significant reductions in gray matter volume in several areas of the brain, including the medial prefrontal cortex, insula, Rolandic operculum, parts of the temporal lobe, and the hippocampus.32-35 Amann et al32 found that patients with SAD and schizophrenia had widespread and overlapping areas of significant volume reduction, but patients with bipolar disorder did not. These studies suggest that at least from a neuroimaging standpoint, SAD is more closely related to schizophrenia than bipolar disorder, and could represent a variant of schizophrenia.

Treatment of SAD

The pharmacotherapy of SAD is mostly empirical because of the lack of randomized controlled trials. Clinicians have traditionally prescribed an antipsychotic agent along with either a mood stabilizer (eg,

Since that exhaustive review,

Patients with SAD will require maintenance treatment for ongoing symptom control. Medication that is effective for treatment of an acute episode should be considered for maintenance treatment. Both the extended-release and long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of paliperidone have been shown to be efficacious in the maintenance treatment of patients with SAD.40 The LAI form of paliperidone significantly delayed psychotic, depressive, and manic relapses, improved clinical rating scale scores, and increased medication adherence.41,42 In an open-label study, olanzapine LAI was effective in long-term maintenance treatment, although approximately 40% of patients experienced significant weight gain.43 One concern with olanzapine is the possible occurrence of a post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome. For that reason, patients receiving olanzapine must be monitored for at least 3 hours post-injection. The paliperidone LAI does not require monitoring after injection.

Continue to: There is a single clinical trial...

There is a single clinical trial showing that patients with SAD can be successfully switched from other antipsychotics to

Other approaches

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) should be considered for patients with SAD who are acutely ill and have failed to respond adequately to medication. ECT is especially relevant in the setting of acute mood symptoms (ie, depressive or manic symptoms co-occurring with psychosis or in the absence of psychosis).45

As currently conceptualized, the diagnosis of SAD is made in persons having an admixture of mood and psychotic symptoms, although by definition mood symptoms must take up the majority (≥50%) of the total duration of the illness. Unfortunately, SAD has been inadequately researched due to the unreliability of its definition and concerns about its validity. The long-term course of SAD is midway between mood and psychotic disorders, and the disorder can cause significant disability.

Bottom Line

Schizoaffective disorder (SAD) is characterized by the presence of symptoms of a major mood episode (a depressive or manic episode) concurrent with symptoms of schizophrenia. The most important basis for establishing the diagnosis is the patient’s history. Determining the percentage of time spent in a mood episode is especially important. Treatment usually consists of an antipsychotic plus a mood stabilizer or antidepressant. Electroconvulsive therapy is an option for patients with SAD who do not respond well to medication.

Related Resources

- Wy TJP, Saadabadi A. Schizoaffective disorder. NCBI Bookshelf: StatPearls Publishing. Published January 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541012/. Updated April 15, 2020.

- Parker G. How well does the DSM-5 capture schizoaffective disorder? Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(9):607-610.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine long-acting injectable • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega sustenna

Valproate • Depacon

Mr. C, age 34, presented to the emergency department with his wife because of increasingly bizarre behavior. He reported auditory and visual hallucinations, and believed that the “mob had ordered a hit” against him. He had threatened to shoot his wife and children, which led to his arrest and being briefly jailed. In jail, he was agitated, defecated on the floor, and disrobed. His wife reported that Mr. C had a long history of bipolar disorder and had experienced his first manic episode and hospitalization at age 17. Since then, he had been treated with many different antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers.

Mr. C was admitted to the hospital, where he developed a catatonic syndrome that was treated with a course of electroconvulsive therapy. He was eventually stabilized with

Over the next 8 years, Mr. C was often noncompliant with medication and frequently was hospitalized for mania. His symptoms included poor sleep, grandiosity, pressured speech, racing and disorganized thoughts, increased risk-taking behavior (ie, driving at excessive speeds), and hyperreligiosity (ie, speaking with God). Mr. C also occasionally used methamphetamine, cannabis, and cocaine. Although he had responded well to treatment early in the course of his illness, as he entered his late 30s, his response was less complete, and by his 40s, Mr. C was no longer able to function independently. He eventually was prescribed a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, paliperidone palmitate, 156 mg monthly. Eventually, his family was no longer able to care for him at home, so he was admitted to a residential care facility.

In this facility, based on the long-standing nature of Mr. C’s psychotic disorder and frequency with which he presented with mania, his clinicians changed his diagnosis to schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. It had become clear that mood symptoms comprised >50% of the total duration of his illness.

Schizoaffective disorder (SAD) often has been used as a diagnosis for patients who have an admixture of mood and psychotic symptoms whose diagnosis is uncertain. Its hallmark is the presence of symptoms of a major mood episode (either a depressive or manic episode) concurrent with symptoms characteristic of schizophrenia, such as delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech.1

SAD is a controversial diagnosis. There has been inadequate research regarding the epidemiology, course, etiologic factors, and treatment of this disorder. Debate continues to swirl around its conceptualization; some experts view SAD as an independent disorder, while others see SAD as either a form of schizophrenia or a mood disorder.1 In this review, we describe the classification of SAD and its features, diagnosis, and treatment.

An evolving diagnosis

The term schizoaffective was first used by Jacob Kasanin, MD, in 1933.2 He described 9 patients with “acute schizoaffective psychoses,” each of whom had an abrupt onset. The term was used in the first edition of the DSM as a subtype of schizophrenia.3 In DSM-I, the “schizo-affective type” was defined as a diagnosis for patients with a “significant admixture of schizophrenic and affective reactions.”3 Diagnostic criteria for SAD were developed for DSM-III-R, published in 1987.4 These criteria continued to evolve with subsequent editions of the DSM.

Continue to: DSM-5 provides...

DSM-5 provides a clearer separation between schizophrenia with mood symptoms, bipolar disorder, and SAD (Table5). In addition, DSM-5 shifts away from the DSM-IV diagnosis of SAD as an episode, and instead focuses more on the longitudinal course of the illness. It has been suggested that this change will likely lead to reduced rates of diagnosis of SAD.6 Despite improvements in classification, the diagnosis remains controversial (Box7-11).

Box 1

Despite improvements in classification, controversy continues to swirl around the question of whether schizoaffective disorder (SAD) represents an independent disorder that stands apart from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, whether it is a form of schizophrenia, or whether it is a form of bipolar disorder or a depressive disorder.7,8 Other possibilities are that SAD is heterogeneous or that it represents a middle point on a spectrum that bridges mood and psychotic disorders. While the merits of each possibility are beyond the scope of this review, it is safe to say that each possibility has its proponents. For these reasons, some argue that the concept itself lacks validity and shows the pitfalls of our classification system.7

Poor diagnostic reliability is one reason for concerns about validity. Most recently, a field trial using DSM-5 criteria produced a kappa of 0.50, which is moderate,9 but earlier definitions produced relatively poor results. Wilson et al10 point out that Criterion C, which concerns duration of mood symptoms, produces a particularly low kappa. Another reason is diagnostic switching, whereby patients initially diagnosed with 1 disorder receive a different diagnosis at followup. Diagnostic switching is especially problematic for SAD. In a large meta-analysis by Santelmann et al,11 36% of patients initially diagnosed with SAD had their diagnosis changed when reassessed. This diagnostic shift tended more toward schizophrenia than bipolar disorder. In addition, more than one-half of all patients initially diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder were re-diagnosed with SAD when reassessed.

DSM-5 subtypes and specifiers

In DSM-5,SAD has 2 subtypes5:

- Bipolar type. The bipolar type is marked by the presence of a manic episode (major depressive episodes may also occur)

- Depressive type. The depressive type is marked by the presence of only major depressive episodes.

SAD also includes several specifiers, with the express purpose of giving clinicians greater descriptive ability. The course of SAD can be described as either “first episode,” defined as the first manifestation of the disorder, or as having “multiple episodes,” defined as a minimum of 2 episodes with 1 relapse. In addition, SAD can be described as an acute episode, in partial remission, or in full remission. The course can be described as “continuous” if it is clear that symptoms have been present for the majority of the illness with very brief subthreshold periods. The course is designated as “unspecified” when information is unavailable or lacking. The 5-point Clinician-Rated Dimensions of Psychosis Symptoms was introduced to enable clinicians to make a quantitative assessment of the psychotic symptoms, although its use is not required.

Epidemiology and gender ratio

The epidemiology of SAD has not been well studied. DSM-5 estimates that SAD is approximately one-third as common as schizophrenia, which has a lifetime prevalence of 0.5% to 0.8%.5 This is similar to an estimate by Perälä et al12 of a 0.32% lifetime prevalence based on a nationally representative sample of persons in Finland age ≥30. Scully et al13 calculated a prevalence estimate of 1.1% in a representative sample of adults in rural Ireland. Based on pooled clinical data, Keck et al14 estimated the prevalence in clinical settings at 16%, similar to the figure of 19% reported by Levinson et al15 based on data from New York State psychiatric hospitals. In clinical practice, the diagnosis of SAD is used frequently when there is diagnostic uncertainty, which potentially inflates estimates of lifetime prevalence.

The prevalence of SAD is higher in women than men, with a sex ratio of about 2:1, similar to that seen in mood disorders.13,16-19 There are an equal number of men and women with the bipolar subtype, but a female preponderance with the depressive subtype.5 The bipolar subtype is more common in younger patients, while the depressive subtype is more common in older patients. SAD is a rare diagnosis in children.20

Continue to: Course and outcome

Course and outcome

The onset of SAD typically occurs in early adulthood, but can range from childhood to senescence. Approximately one-third of patients are diagnosed before age 25, one-third between age 25 and 35, and one-third after age 35.21-23 Based on a literature review, Cheniaux et al7 concluded that that age at onset for patients with SAD is between those with schizophrenia and those with mood disorders.

The course of SAD is variable but represents a middle ground between that of schizophrenia and the mood disorders. In a 4- to 5-year follow-up,24 patients with SAD had a better overall course than patients with schizophrenia but had poorer functioning than those with bipolar mania, and much poorer than those with unipolar depression. Mood-incongruent psychotic features predict a particularly worse outcome. These findings were reaffirmed at a 10-year follow-up.25 Mood symptoms portend a better outcome than do symptoms of schizophrenia.

The lifetime suicide risk for patients with SAD is estimated at 5%, with a higher risk associated with the presence of depressive symptoms.26 One study found that women with SAD had a 17.5-year reduced life expectancy (64.1 years) compared with a reduction of 8.0 years for men (69.4 years).27

Comorbidity

Patients with SAD are commonly diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders, including anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders.21,28,29 When compared with the general population, patients with SAD are at higher risk for coronary heart disease, stroke, obesity, and smoking, likely contributing to their decreased life expectancy.27,30 Because second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are often used to treat SAD, patients with SAD are at risk for metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus.30

Clinical assessment

Because there are no diagnostic, laboratory, or neuroimaging tests for SAD, the most important basis for making the diagnosis is the patient’s history, supplemented by collateral history from family members or friends, and medical records. Determining the percentage of time spent in a mood episode (DSM-5 Criterion C) is especially important.31 This requires the clinician to pay close attention to the temporal relationship of psychotic and mood symptoms.

Continue to: Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for SAD is broad because it includes all of the possibilities usually considered for major mood disorders and for psychotic disorders5:

- schizophrenia

- bipolar disorder with psychotic features

- major depressive disorder with psychotic features

- depressive or bipolar disorders with catatonic features

- personality disorders (especially the schizotypal, paranoid, and borderline types)

- major neurocognitive disorders in which there are mood and psychotic symptoms

- substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder

- disorders induced by medical conditions.

With schizophrenia, the duration of all episodes of a mood syndrome is brief (<50% of the total duration of the illness) relative to the duration of the psychotic symptoms. Although psychotic symptoms may occur in persons with mood disorders, they are generally not present in the absence of depression or mania, helping to set the boundary between SAD and psychotic mania or depression. As for personality disorders, the individual will not have a true psychosis, although some symptoms, such as feelings of unreality, paranoia, or magical thinking, may cause diagnostic confusion.

Medical conditions also can present with psychotic and mood symptoms and need to be ruled out. These include psychotic disorder due to another medical condition, and delirium. A thorough medical workup should be performed to rule out any possible medical causes for the symptoms.

Substance use should also be ruled out as the cause of the symptoms because many substances are associated with mood and psychotic symptoms. It is usually clear from the history, physical examination, or laboratory tests when a medication/illicit substance has initiated and maintained the disorder.

Neurologic conditions. If a neurologic condition is suspected, a neurologic evaluation may be warranted, including laboratory tests, brain imaging to identify specific anatomical abnormalities, lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and an electroencephalogram to rule out a convulsive disorder.

Continue to: Clinical symptoms

Clinical symptoms

The signs and symptoms of SAD include those typically seen in schizophrenia and the mood disorders. Thus, the patient may exhibit elated mood and/or grandiosity, or severe depression, combined with mood-incongruent psychotic features such as paranoid delusions. The symptoms may present together or in an alternating fashion, and psychotic symptoms may be mood-congruent or mood-incongruent. Mr. C’s case illustrates some of the symptoms of the disorder.

Brain imaging

Significant changes have been reported to occur in the brain structure and function in persons with SAD. Neuroimaging studies using voxel-based morphometry have shown significant reductions in gray matter volume in several areas of the brain, including the medial prefrontal cortex, insula, Rolandic operculum, parts of the temporal lobe, and the hippocampus.32-35 Amann et al32 found that patients with SAD and schizophrenia had widespread and overlapping areas of significant volume reduction, but patients with bipolar disorder did not. These studies suggest that at least from a neuroimaging standpoint, SAD is more closely related to schizophrenia than bipolar disorder, and could represent a variant of schizophrenia.

Treatment of SAD

The pharmacotherapy of SAD is mostly empirical because of the lack of randomized controlled trials. Clinicians have traditionally prescribed an antipsychotic agent along with either a mood stabilizer (eg,

Since that exhaustive review,

Patients with SAD will require maintenance treatment for ongoing symptom control. Medication that is effective for treatment of an acute episode should be considered for maintenance treatment. Both the extended-release and long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of paliperidone have been shown to be efficacious in the maintenance treatment of patients with SAD.40 The LAI form of paliperidone significantly delayed psychotic, depressive, and manic relapses, improved clinical rating scale scores, and increased medication adherence.41,42 In an open-label study, olanzapine LAI was effective in long-term maintenance treatment, although approximately 40% of patients experienced significant weight gain.43 One concern with olanzapine is the possible occurrence of a post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome. For that reason, patients receiving olanzapine must be monitored for at least 3 hours post-injection. The paliperidone LAI does not require monitoring after injection.

Continue to: There is a single clinical trial...

There is a single clinical trial showing that patients with SAD can be successfully switched from other antipsychotics to

Other approaches

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) should be considered for patients with SAD who are acutely ill and have failed to respond adequately to medication. ECT is especially relevant in the setting of acute mood symptoms (ie, depressive or manic symptoms co-occurring with psychosis or in the absence of psychosis).45

As currently conceptualized, the diagnosis of SAD is made in persons having an admixture of mood and psychotic symptoms, although by definition mood symptoms must take up the majority (≥50%) of the total duration of the illness. Unfortunately, SAD has been inadequately researched due to the unreliability of its definition and concerns about its validity. The long-term course of SAD is midway between mood and psychotic disorders, and the disorder can cause significant disability.

Bottom Line

Schizoaffective disorder (SAD) is characterized by the presence of symptoms of a major mood episode (a depressive or manic episode) concurrent with symptoms of schizophrenia. The most important basis for establishing the diagnosis is the patient’s history. Determining the percentage of time spent in a mood episode is especially important. Treatment usually consists of an antipsychotic plus a mood stabilizer or antidepressant. Electroconvulsive therapy is an option for patients with SAD who do not respond well to medication.

Related Resources

- Wy TJP, Saadabadi A. Schizoaffective disorder. NCBI Bookshelf: StatPearls Publishing. Published January 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541012/. Updated April 15, 2020.

- Parker G. How well does the DSM-5 capture schizoaffective disorder? Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(9):607-610.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine long-acting injectable • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega sustenna

Valproate • Depacon

1. Miller JN, Black DW. Schizoaffective disorder: a review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2019;31(1):47-53.

2. Kasanin J. The acute schizoaffective psychoses. Am J Psychiatry. 1933;90:97-126.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd ed, revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Malaspina D, Owen M, Heckers S, et al. Schizoaffective disorder in the DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:21-25.

7. Cheniaux E, Landeria-Fernandez J, Telles LL, et al. Does schizoaffective disorder really exist? A systematic review of the studies that compared schizoaffective disorder with schizophrenia or mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:209-217.

8. Kantrowitz JT, Citrome L. Schizoaffective disorder: a review of current research themes and pharmacologic management. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:317-331.

9. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE, et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: test-retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:59-70.

10. Wilson JE, Nian H, Heckers S. The schizoaffective disorder diagnosis: a conundrum in the clinical setting. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:29-34.

11. Santelmann H, Franklin J, Bußhoff J, Baethge C. Test-retest reliability of schizoaffective disorder compared with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depression--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:753-768.

12. Perälä J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, et al. Lifetime Prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2007;64:19-28.

13. Scully PJ, Owens JM, Kinsella A, et al. Schizophrenia, schizoaffective and bipolar disorder within an epidemiologically complete, homogeneous population in rural Ireland: small area variation in rate. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:143-155.

14. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SE, Strakowski SM, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Psychopharmacol. 1994;114:529-538.

15. Levinson DF, Umapathy C, Musthaq M. Treatment of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia with mood symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1138-1148.

16. Angst J, Felder W, Lohmeyer B. Course of schizoaffective psychoses: results of a follow-up study. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6:579-585.

17. Lenz G, Simhandl C, Thau K, et al. Temporal stability of diagnostic criteria for functional psychoses. Psychopathol. 1991;24:328-335.

18. Malhi GS, Green M, Fagiolini A, et al. Schizoaffective disorder: diagnostic issues and future recommendations. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:215-230.

19. Marneros A, Deister A, Rohde A. Psychopathological and social status of patients with affective, schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders after long‐term course. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82:352-358.

20. Werry JS, McClellan JM, Chard L. Childhood and adolescent schizophrenic, bipolar, and schizoaffective disorders: a clinical and outcome study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:457-465.

21. Abrams DJ, Rojas DC, Arciniegas DB. Is schizoaffective disorder a distinct categorical diagnosis? A critical review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:1089-1109.

22. Bromet EJ, Kotov R, Fochtmann LJ, et al. Diagnostic shifts during the decade following first admission for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1186-1194.

23. Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, et al. The McLean-Harvard First Episode Project: two-year stability of DSM-IV diagnoses in 500 first-episode psychotic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:458-466.

24. Grossman LS, Harrow M, Goldberg JF, et al. Outcome of schizoaffective disorder at two long term follow-ups: comparisons with outcome of schizophrenia and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1359-1365.

25. Harrow M, Grossman L, Herbener E, et al. Ten-year outcome: patients with schizoaffective disorders, schizophrenia, affective disorders and mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:421-426.

26. Hor K, Taylor M. Review: suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:81-90.

27. Chang CK, Hayes RD, Perera G, et al. Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19590.

28. Byerly M, Goodman W, Acholonu W, et al. Obsessive compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia: frequency and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2005;76:309-316.

29. Strauss JL, Calhoun PS, Marx CE, et al. Comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with suicidality in male veterans with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2006;84:165-169.

30. Fagiolini A, Goracci A. The effects of undertreated chronic medical illnesses in patients with severe mental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:22-29.

31. Black DW, Grant JE. DSM-5 guidebook: the essential companion to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014.

32. Amann BL, Canales-Rodríguez EJ, Madre M, et al. Brain structural changes in schizoaffective disorder compared to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133:23-33.

33. Ivleva EI, Bidesi AS, Keshavan MS, et al. Gray matter volume as an intermediate phenotype for psychosis: Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP). Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1285-1296.

34. Ivleva EI, Bidesi AS, Thomas BP, et al. Brain gray matter phenotypes across the psychosis dimension. Psychiatry Res. 2012;204:13-24.

35. Radonic

36. Jäger M, Becker T, Weinmann S, et al. Treatment of schizoaffective disorder - a challenge for evidence-based psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:22-32.

37. Glick ID, Mankosli R, Eudicone JM, et al. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of aripiprazole for the treatment of schizoaffective disorder: results from a pooled analysis of a sub-population of subjects from two randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, pivotal trials. J Affect Disord. 2009;115:18-26.

38. Canuso CM, Lindenmayer JP, Kosik-Gonzalez C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study of 2 dose ranges of paliperidone extended-release in the treatment of subjects with schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:587-598.

39. Canuso CM, Schooler NR, Carothers J, et al. Paliperidone extended-release in schizoaffective disorder: a randomized controlled trial comparing a flexible-dose with placebo in patients treated with and without antidepressants and/or mood stabilizers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:487-495.

40. Lindenmayer JP, Kaur A. Antipsychotic management of schizoaffective disorder: a review. Drugs. 2016;76:589-604.

41. Alphs L, Fu DJ, Turkoz I. Paliperidone for the treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;176:871-883.

42. Bossie CA, Turkoz I, Alphs L, et al. Paliperidone palmitate once-monthly treatment in recent onset and chronic illness patients with schizoaffective disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205:324-328.

43. McDonnell DP, Landry J, Detke HC. Long-term safety and efficacy of olanzapine long-acting injection in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a 6-year, multinational, single-arm, open-label study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29:322-331.

44. McEvoy JP, Citrome L, Hernandez D, et al. Effectiveness of lurasidone in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder switched from other antipsychotics: a randomized, 6-week, open-label study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:170-179.

45. Mankad MV, Beyer JL, Wiener RD, et al. Manual of electroconvulsive therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2010.

1. Miller JN, Black DW. Schizoaffective disorder: a review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2019;31(1):47-53.

2. Kasanin J. The acute schizoaffective psychoses. Am J Psychiatry. 1933;90:97-126.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd ed, revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Malaspina D, Owen M, Heckers S, et al. Schizoaffective disorder in the DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:21-25.

7. Cheniaux E, Landeria-Fernandez J, Telles LL, et al. Does schizoaffective disorder really exist? A systematic review of the studies that compared schizoaffective disorder with schizophrenia or mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:209-217.

8. Kantrowitz JT, Citrome L. Schizoaffective disorder: a review of current research themes and pharmacologic management. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:317-331.

9. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE, et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: test-retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:59-70.

10. Wilson JE, Nian H, Heckers S. The schizoaffective disorder diagnosis: a conundrum in the clinical setting. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:29-34.

11. Santelmann H, Franklin J, Bußhoff J, Baethge C. Test-retest reliability of schizoaffective disorder compared with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depression--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:753-768.

12. Perälä J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, et al. Lifetime Prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2007;64:19-28.

13. Scully PJ, Owens JM, Kinsella A, et al. Schizophrenia, schizoaffective and bipolar disorder within an epidemiologically complete, homogeneous population in rural Ireland: small area variation in rate. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:143-155.

14. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SE, Strakowski SM, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Psychopharmacol. 1994;114:529-538.

15. Levinson DF, Umapathy C, Musthaq M. Treatment of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia with mood symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1138-1148.

16. Angst J, Felder W, Lohmeyer B. Course of schizoaffective psychoses: results of a follow-up study. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6:579-585.

17. Lenz G, Simhandl C, Thau K, et al. Temporal stability of diagnostic criteria for functional psychoses. Psychopathol. 1991;24:328-335.

18. Malhi GS, Green M, Fagiolini A, et al. Schizoaffective disorder: diagnostic issues and future recommendations. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:215-230.

19. Marneros A, Deister A, Rohde A. Psychopathological and social status of patients with affective, schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders after long‐term course. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82:352-358.

20. Werry JS, McClellan JM, Chard L. Childhood and adolescent schizophrenic, bipolar, and schizoaffective disorders: a clinical and outcome study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:457-465.

21. Abrams DJ, Rojas DC, Arciniegas DB. Is schizoaffective disorder a distinct categorical diagnosis? A critical review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:1089-1109.

22. Bromet EJ, Kotov R, Fochtmann LJ, et al. Diagnostic shifts during the decade following first admission for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1186-1194.

23. Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, et al. The McLean-Harvard First Episode Project: two-year stability of DSM-IV diagnoses in 500 first-episode psychotic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:458-466.

24. Grossman LS, Harrow M, Goldberg JF, et al. Outcome of schizoaffective disorder at two long term follow-ups: comparisons with outcome of schizophrenia and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1359-1365.

25. Harrow M, Grossman L, Herbener E, et al. Ten-year outcome: patients with schizoaffective disorders, schizophrenia, affective disorders and mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:421-426.

26. Hor K, Taylor M. Review: suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:81-90.

27. Chang CK, Hayes RD, Perera G, et al. Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19590.

28. Byerly M, Goodman W, Acholonu W, et al. Obsessive compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia: frequency and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2005;76:309-316.

29. Strauss JL, Calhoun PS, Marx CE, et al. Comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with suicidality in male veterans with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2006;84:165-169.

30. Fagiolini A, Goracci A. The effects of undertreated chronic medical illnesses in patients with severe mental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:22-29.

31. Black DW, Grant JE. DSM-5 guidebook: the essential companion to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014.

32. Amann BL, Canales-Rodríguez EJ, Madre M, et al. Brain structural changes in schizoaffective disorder compared to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133:23-33.

33. Ivleva EI, Bidesi AS, Keshavan MS, et al. Gray matter volume as an intermediate phenotype for psychosis: Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP). Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1285-1296.

34. Ivleva EI, Bidesi AS, Thomas BP, et al. Brain gray matter phenotypes across the psychosis dimension. Psychiatry Res. 2012;204:13-24.

35. Radonic

36. Jäger M, Becker T, Weinmann S, et al. Treatment of schizoaffective disorder - a challenge for evidence-based psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:22-32.

37. Glick ID, Mankosli R, Eudicone JM, et al. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of aripiprazole for the treatment of schizoaffective disorder: results from a pooled analysis of a sub-population of subjects from two randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, pivotal trials. J Affect Disord. 2009;115:18-26.

38. Canuso CM, Lindenmayer JP, Kosik-Gonzalez C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study of 2 dose ranges of paliperidone extended-release in the treatment of subjects with schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:587-598.

39. Canuso CM, Schooler NR, Carothers J, et al. Paliperidone extended-release in schizoaffective disorder: a randomized controlled trial comparing a flexible-dose with placebo in patients treated with and without antidepressants and/or mood stabilizers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:487-495.

40. Lindenmayer JP, Kaur A. Antipsychotic management of schizoaffective disorder: a review. Drugs. 2016;76:589-604.

41. Alphs L, Fu DJ, Turkoz I. Paliperidone for the treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;176:871-883.

42. Bossie CA, Turkoz I, Alphs L, et al. Paliperidone palmitate once-monthly treatment in recent onset and chronic illness patients with schizoaffective disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205:324-328.

43. McDonnell DP, Landry J, Detke HC. Long-term safety and efficacy of olanzapine long-acting injection in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a 6-year, multinational, single-arm, open-label study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29:322-331.

44. McEvoy JP, Citrome L, Hernandez D, et al. Effectiveness of lurasidone in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder switched from other antipsychotics: a randomized, 6-week, open-label study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:170-179.

45. Mankad MV, Beyer JL, Wiener RD, et al. Manual of electroconvulsive therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2010.