User login

Managing ‘difficult’ patient encounters

“I did not like those patients… They made me angry and I found myself irritated to experience them as they seemed so distant from myself and from all that is human. This is an astonishing intolerance which brands me a poor psychiatrist.”

Sigmund Freud, Letter to István Hollós (1928)

While Freud was referring to psychotic patients,1 his evident frustration shows that difficult and challenging patients have vexed even the best of us. All physicians and other clinicians will experience patient encounters that lead to anger or frustration, or even challenge their sense of equanimity and professional identity. In short, difficult and challenging patient interactions are unavoidable, regardless of the physician’s discipline.2-5 At times, physicians might struggle with demanding, unpleasant, ungrateful, and possibly dangerous patients, while sometimes the struggle is with the patient’s family members. No physician is immune to the problem, which makes it crucial to learn to anticipate and manage difficult patient interactions, skills which are generally not taught in medical schools or residency programs.

One prospective study of clinic patients found that up to 15% of patient encounters are deemed “difficult.”6 Common scenarios include patients (or their relatives) who seek certain tests after researching symptoms online, threats of legal or social media action in response to feeling that the physician is not listening to them, demands for a second opinion after disagreeing with the physician’s diagnosis, and mistrust of doctors after presenting with symptoms and not receiving a diagnosis. It is also common to care for patients who focus on negative outcomes or fail to adhere to treatment recommendations. These encounters can make physicians feel stressed out, disrespected, abused, or even fearful if threatened. Some physicians may come to feel they are trapped in a hostile work environment with little support from their supervisors or administrators. Patients often have a complaint office or department to turn to, but there is no equivalent for physicians, who are expected to soldier on regardless.

This article highlights a model that describes poor physician-patient encounters, factors contributing to these issues, how to manage these difficult interactions, and what to do if the relationship cannot be remediated.

Describing the ‘difficult’ patient

In a landmark 1978 paper, Groves7 provided one of the first descriptions of “difficult” patients. His colorful observations continue to provide useful insights. Groves emphasized that most medical texts ignore the issue of difficult patients and provide little or no guidance—which is still true 43 years later. He observed that physicians cannot avoid occasional negative feelings toward some patients. Further, Groves suggested that countertransference is often at the root of hateful reactions, a process he defines as “conscious or unconscious unbidden and unwanted hostile or sexual feelings toward the patient.”7Table 17 outlines how Groves divided “hateful” patients into several categories, and how physicians might respond to such patients.

A model for understanding difficult patient encounters

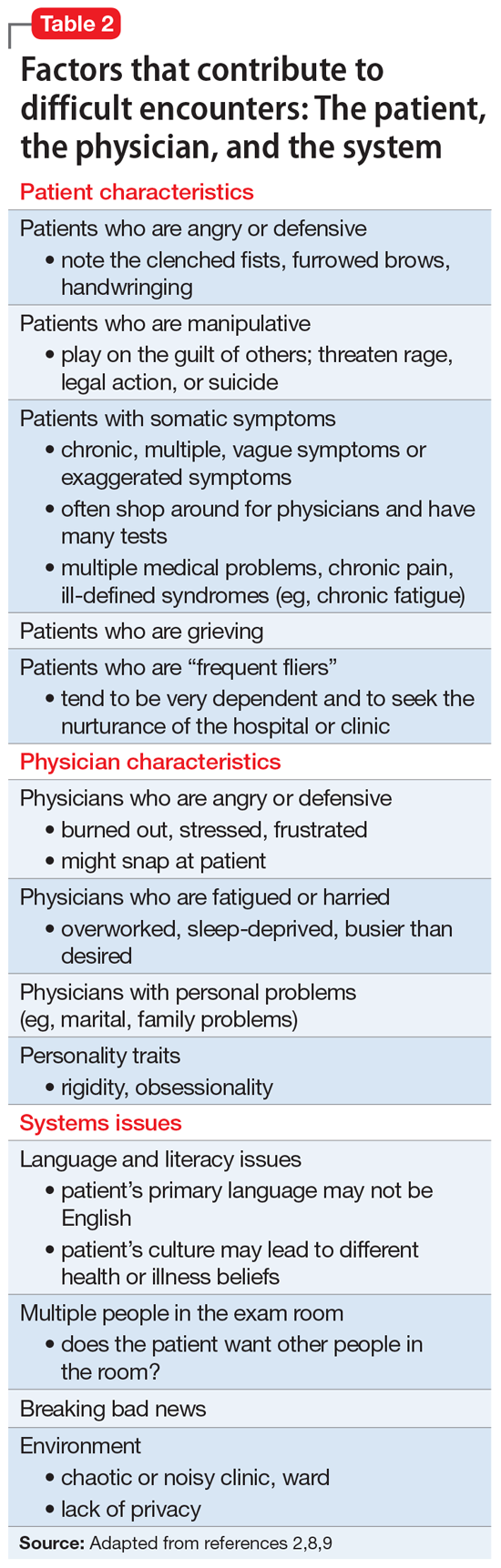

Adams and Murray2 created a model to help explain interactions with difficult or challenging patients that consists of 3 elements: the patient, the physician, and the system (ie, situation or environment). Hull and Broquet8 and Hardavella et al9 later adapted the model and described its components (Table 22,8,9).

Continue to: When considering...

When considering difficult interactions, it is important to be aware that all 3 components could interact, or merely 1 or 2 could come into play, but all should be explored as possible contributing factors.

Patient factors

The patient’s role in initiating or maintaining a problematic interaction should be explored. While some physicians are tempted to conclude that a personality disorder underlies difficult interactions, research shows a more complex picture. First, not all difficult patients have a psychiatric disorder, let alone a personality disorder. Jackson and Kroenke6 reported that among 74 difficult patients in an ambulatory clinic, 29% had a depressive disorder or anxiety disorder, with 11% experiencing 2 or more disorders. Major depressive disorder was present in 8.4% patients, other depressive disorders in 17.4%, panic disorder in 1.4%, and other anxiety disorders in 14.2%.6 These researchers found that difficult patient interactions were associated with the presence of a psychiatric disorder, especially depressive or anxiety disorders, and multiple physical symptoms.

Importantly, difficult patients are not unique to psychiatry, and are found in all medical disciplines and every type of practice situation. Some problematic patients have a substance use disorder, and their difficulty might stem from intoxication, withdrawal, or drug-seeking behaviors. Psychotic disorders can be the source of difficult interactions, typically resulting from the patient’s symptoms (ie, hallucinations, delusions, or bizarre behavior). Physicians tend to be forgiving toward these patients because they understand the extent of the individual’s illness. The same is true for a patient with dementia, who might be disruptive and loud, yet clearly is not in control of their behavior.

Koekkoek et al5 reviewed 94 articles that focused on difficult patients seen in mental health settings. Most patients were male (60% to 68%), and most were age 26 to 32 years. Diagnoses of psychotic disorders and personality disorders were the most frequent, while mood and other disorders were less common. In 1 of the studies reviewed, 6% of psychiatric inpatients were considered difficult. Koekkoek et al5 proposed that there are 3 groups of difficult patients:

- care avoiders: patients with psychosis who lack insight

- care seekers: patients who are chronically ill who have trouble maintaining a steady relationship with their caregivers

- care claimers: patients who do not require long-term care, but need housing, medication, or a “declaration of incompetence.”

Physician factors

Physicians are frequent contributors to bad interactions with their patients.2,7,8 They can become angry or defensive because of burnout, stress, or frustration, which might lead them to snap or otherwise respond inappropriately to their patients. Many physicians are overworked, sleep-deprived, or busier than they would prefer. Personal problems can be preoccupying and contribute to a physician being ill-tempered or distracted (eg, marital or family problems). Some physicians are simply poor communicators and might not understand the need to adapt their communication style to their patient, instead using medical jargon the patient does not understand. Ideally, physicians should modify their language to suit the patient’s level of education, degree of medical sophistication, and cultural background.

Continue to: A physician's personality traits...

A physician’s personality traits could clash with those of the patient, particularly if the physician is especially rigid or obsessional. Rather than “going with the flow,” the overly rigid physician might become impatient with patients who fail to understand diagnostic assessments or treatment recommendations. Inefficient physicians might not be able to keep up with the daily schedule, which could fuel impatience and perhaps even lead them to think that the patient is taking too much of their valuable time. Some might not know how to convey empathy, for example when giving bad news (“The tests show you have cancer…”). Others fail to make consistent eye contact with patients without understanding its importance to communication, a problem made worse by the use of electronic medical record systems (EMRs).

Systems issues

Systems issues also contribute to suboptimal physician-patient interactions, and some issues can be attributed to administrative problems. Examples of systems issues include:

- when a patient has difficulty making an appointment and is forced to listen to a confusing menu of choices

- a busy clinic that can only offer a patient an appointment 6 months away

- crowded or noisy waiting rooms

- language barriers for patients whose primary langage is not English. Not having access to an interpreter can exacerbate their frustration

- the use of EMRs is a growing threat to positive physician-patient interactions, yet their influence is often ignored. Widely disliked by physicians,10 EMRs are required in all but the smallest independent practice settings. Many busy physicians focus their attention on the computer, giving the patient the impression that the physician is not listening to them. Many patients conclude that they are less important than the process.

The consequences of difficult interactions

Following a bad interaction, dissatisfied patients are more likely to leave the clinic or hospital and ignore medical advice. These patients might then show up in crowded emergency departments, which may lead to poor use of health care resources. For physicians, challenging situations sap their emotional energy, cause demoralization, and interfere with their sense of job fulfillment. In extreme cases, such feelings might lead the physician to dislike and even avoid the patient.

How to manage challenging situations

Taking the following steps can help physicians work through challenging situations with their patients.

Diagnose the problem. First, recognize the difficult situation, analyze it, and identify how the patient, the physician, and the system are contributing to a bad physician-patient interaction. Diagnosing the interactional difficulty should precede the diagnosis and management of the patient’s disease. Physicians should acknowledge their own contribution through their attitude or actions. Finally, determine if there are system issues that are contributing to the problem, or if it is the clinic or inpatient setting itself (eg, noisy inpatient unit).

Continue to: Maintain your cool

Maintain your cool. With any difficult interaction, a physician’s first obligation is to remain calm and professional, while modeling appropriate behavior. If the patient is angry or emotionally intense, talking over them or interrupting them only makes the situation worse. Try to see the interaction from the patient’s perspective. Both parties should work together to find a common ground.

Collaborate, respect boundaries, and empathize. One study of a group of 100 family physicians found that having the following 3 skills were essential to successfully managing situations with difficult patients11,12:

- the ability to collaborate (vs opposition)

- the appropriate use of power (vs misuse of power, or violation of boundaries by either party)

- the ability to empathize, which for most physicians involves understanding and validating the patient’s subjective experiences.

Although a description of the many facets of empathy (cognitive, affective, motivational) is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth pointing out that a patient’s positive perception of their physician’s empathy improves not only patient satisfaction but health outcomes.13 The Box describes a difficult patient whose actions changed through the collaboration and empathy of his treatment team.

Box 1

Mr. L, a 60-year-old veteran, is admitted to an inpatient unit following a suicide attempt that was prompted by eviction from his apartment. Mr. L is physically disabled and has difficulty walking without assistance. His main concern is his homelessness, and he insists that the inpatient team find a suitable “Americans with Disabilities (ADA)-compliant apartment” that he can afford on his $800 monthly income. He implies that he will kill himself if the team fails in that task. He makes it clear that his problems are the team’s problems. He is prescribed an antidepressant, and both his mood and reported suicidal ideations gradually resolve.

The team’s social worker finds an opening at a well-run veterans home, but Mr. L rejects it because he doesn’t want to “give up his independence.” The social worker finds a small apartment in a nearby community that is ADA-compliant, but Mr. L complains that it is small. He asks the resident psychiatrist, “Where will I put all my things?” The next day, after insulting the attending psychiatrist for failing to find an adequate apartment, Mr. L says from under the bedsheet: “How come none of you ever help me?”

Mr. L presents a challenge to the entire team. At times, he is rude, demanding, and entitled. The team recognizes that although he had served in the military with distinction, he is now alone after having divorced many years earlier, and nearly friendless because of his increasing disability. The team surmises that Mr. L lashes out due to frustration and feelings of powerlessness.

Resolving this conflict involves treating Mr. L with respect and listening without judgment. No one ever confronts him or argues with him. The team psychologist meets with him to help him work through his many losses. Closer to discharge, he is enrolled in several post-hospitalization programs to keep him connected with other veterans. At discharge, the hospital arranges for his belongings that had been in storage to be delivered to his new home. He is pleasant and social with his peers, and although he is still concerned about the size of the apartment, he thanks the team members for their care.

Verbalize the difficulty. It is important to openly discuss the problem. For example, “We both have very different views about how your symptoms should be investigated, and that’s causing some difficulty between us. Do you agree?” This approach names the “elephant in the room” and avoids casting blame. It also creates a sense of shared ownership by externalizing the problem from both the patient and physician. Verbalizing the difficulty can help build trust and pave the way to working together toward a common solution.

Consider other explanations for the patient’s behavior. For example, anger directed at a physician could be due to anxiety about an unrelated matter, such as the patient’s recent job loss or impending divorce. Psychiatrists might understand this behavior better as displacement, which is considered a maladaptive defense mechanism. It is important to listen to the patient and offer empathy, which will help the patient feel supported and build a rapport that can help to resolve the encounter.

Continue to: When helping patients...

When helping patients with multiple issues, which is a common scenario, the physician might start by asking, “What would you like to address today?”14 Keep a list of the issues so you do not forget the patient’s concerns, and then ask: “What do you think is going on?” Give patients time to verbalize their concerns. Physicians should:

- validate concerns: “I understand where you’re coming from.”

- offer empathy: “I can see how difficult this has been for you.”

- reframe: “Let me make sure I hear you correctly.”

- refocus: “Let’s agree on what we need to do at this visit.”

Find common ground. When the patient and physician have different ideas on diagnosis or treatment, finding common ground is another way to resolve a difficult encounter. Difficulties arise when there appears to be little common ground, which often results from unrealistic expectations. Patients might be seen as “demanding” or “manipulative”’ if they push for a diagnosis or treatment the doctor is not comfortable with. As soon as there is some overlap and common ground, the difficulty rapidly subsides.

Set clear boundaries and limits. Physicians should set limits on what patient behavior might “cross the line.” A “behavioral contract” (or “treatment contract”) can help by setting explicit expectations. For example, showing up late for appointments or inappropriately seeking drugs of abuse (eg, opioids, benzodiazepines) might be identified as violations of the contract. Once the contract is set, the patient should be asked to restate key components. Clarify any confusion or barriers to compliance and define clear expectations. The patient should be informed of potential consequences of contract violations, including termination.

Staff members involved in the patient’s care should agree with the terms of any behavioral contract, and should receive a copy of it. Patients should have “buy in,” meaning that they have had an opportunity to provide input to the contract and have agreed to its elements. Both the physician and patient should sign the document.

When all else fails

When there is a breakdown in rapport that makes it difficult or impossible to continue offering treatment, consider termination. This could be due to threatening or abusive patient behavior, sexual advances, repeated no-shows, treatment noncompliance that jeopardizes patient safety, refusal to follow the treatment plan, or violating the terms of a behavioral contract. In some settings, it might be the failure to pay bills.

Continue to: If a patient is unable to...

If a patient is unable to follow the contract, the physician should explore possible extenuating circumstances. The physician should seek to remedy the problem and involve other team members if possible (eg, case manager, nurse), advising a patient about behaviors that could lead to termination.

If the problem is irremediable, notify the patient in writing, give them time to find another physician, and facilitate the transfer of care.15 Take steps to prevent the patient from running out of any medications associated with withdrawal or discontinuation syndromes (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines) during the care transition. While there is no requirement regarding the amount of time allowed, at least 30 days is typical.

Bottom Line

Difficult patient interactions are common and unavoidable. Physicians should acknowledge and recognize contributing factors in such encounters—including their own role. When handling such situations, physicians should remain calm and model appropriate behavior. Improving communication, offering empathy, and validating the patient’s concerns can help resolve factors that contribute to poor patient interactions. If efforts to remediate the physician-patient relationship fail, termination may be necessary.

Related Resources

- Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

- Pereira MR, Figueiredo AF. Challenging patient-doctor interactions in psychiatry – difficult patient syndrome. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(supplement):S719. doi. org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1297

1. Dupont J. Ferenczi’s madness. Contemp Psychoanal. 1988;24(2):250-261.

2. Adams J, Murray R. The difficult diagnosis: the general approach to the difficult patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1998;16(4):689-700.

3. Davies M. Managing challenging interactions with patients. BMJ. 2013;347:f4673. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f4673

4. Chou C. Dealing with the “difficult” patient. Wisc Med J. 2004;103:35-38.

5. Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

6. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounter in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(10):1069-1075.

7. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Eng J Med. 1978;298:883-887.

8. Hull S, Broquet K. How to manage difficult encounters. Fam Prac Manag. 2007;14(6):30-34.

9. Hardavella G, Aamli-Gaagnat A, Frille A, et al. Top tips to deal with challenging situations: doctor patient interactions. Breathe. 2017;13(2):129-135.

10. Black DW, Balon R. Editorial: electronic medical records (EMRs) and the psychiatrist shortage. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2018;30(4):257-259.

11. Elder N, Ricer R, Tobias B. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):533-541.

12. Campbell RJ. Campbell’s Psychiatric Dictionary. 8th Edition. Oxford University Press; 2004:219-220.

13. Decety J, Fotopoulou A. Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: unifying theories. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457

14. Klugman B. The difficult patient. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/office-of-continuing-medical-education/pdfs/cme-primary-care-days/e2-the-difficult-patient.pdf

15. Mossman D, Farrell HM, Gilday E. ‘Firing’ a patient: may psychiatrists unilaterally terminate care? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):18-29.

“I did not like those patients… They made me angry and I found myself irritated to experience them as they seemed so distant from myself and from all that is human. This is an astonishing intolerance which brands me a poor psychiatrist.”

Sigmund Freud, Letter to István Hollós (1928)

While Freud was referring to psychotic patients,1 his evident frustration shows that difficult and challenging patients have vexed even the best of us. All physicians and other clinicians will experience patient encounters that lead to anger or frustration, or even challenge their sense of equanimity and professional identity. In short, difficult and challenging patient interactions are unavoidable, regardless of the physician’s discipline.2-5 At times, physicians might struggle with demanding, unpleasant, ungrateful, and possibly dangerous patients, while sometimes the struggle is with the patient’s family members. No physician is immune to the problem, which makes it crucial to learn to anticipate and manage difficult patient interactions, skills which are generally not taught in medical schools or residency programs.

One prospective study of clinic patients found that up to 15% of patient encounters are deemed “difficult.”6 Common scenarios include patients (or their relatives) who seek certain tests after researching symptoms online, threats of legal or social media action in response to feeling that the physician is not listening to them, demands for a second opinion after disagreeing with the physician’s diagnosis, and mistrust of doctors after presenting with symptoms and not receiving a diagnosis. It is also common to care for patients who focus on negative outcomes or fail to adhere to treatment recommendations. These encounters can make physicians feel stressed out, disrespected, abused, or even fearful if threatened. Some physicians may come to feel they are trapped in a hostile work environment with little support from their supervisors or administrators. Patients often have a complaint office or department to turn to, but there is no equivalent for physicians, who are expected to soldier on regardless.

This article highlights a model that describes poor physician-patient encounters, factors contributing to these issues, how to manage these difficult interactions, and what to do if the relationship cannot be remediated.

Describing the ‘difficult’ patient

In a landmark 1978 paper, Groves7 provided one of the first descriptions of “difficult” patients. His colorful observations continue to provide useful insights. Groves emphasized that most medical texts ignore the issue of difficult patients and provide little or no guidance—which is still true 43 years later. He observed that physicians cannot avoid occasional negative feelings toward some patients. Further, Groves suggested that countertransference is often at the root of hateful reactions, a process he defines as “conscious or unconscious unbidden and unwanted hostile or sexual feelings toward the patient.”7Table 17 outlines how Groves divided “hateful” patients into several categories, and how physicians might respond to such patients.

A model for understanding difficult patient encounters

Adams and Murray2 created a model to help explain interactions with difficult or challenging patients that consists of 3 elements: the patient, the physician, and the system (ie, situation or environment). Hull and Broquet8 and Hardavella et al9 later adapted the model and described its components (Table 22,8,9).

Continue to: When considering...

When considering difficult interactions, it is important to be aware that all 3 components could interact, or merely 1 or 2 could come into play, but all should be explored as possible contributing factors.

Patient factors

The patient’s role in initiating or maintaining a problematic interaction should be explored. While some physicians are tempted to conclude that a personality disorder underlies difficult interactions, research shows a more complex picture. First, not all difficult patients have a psychiatric disorder, let alone a personality disorder. Jackson and Kroenke6 reported that among 74 difficult patients in an ambulatory clinic, 29% had a depressive disorder or anxiety disorder, with 11% experiencing 2 or more disorders. Major depressive disorder was present in 8.4% patients, other depressive disorders in 17.4%, panic disorder in 1.4%, and other anxiety disorders in 14.2%.6 These researchers found that difficult patient interactions were associated with the presence of a psychiatric disorder, especially depressive or anxiety disorders, and multiple physical symptoms.

Importantly, difficult patients are not unique to psychiatry, and are found in all medical disciplines and every type of practice situation. Some problematic patients have a substance use disorder, and their difficulty might stem from intoxication, withdrawal, or drug-seeking behaviors. Psychotic disorders can be the source of difficult interactions, typically resulting from the patient’s symptoms (ie, hallucinations, delusions, or bizarre behavior). Physicians tend to be forgiving toward these patients because they understand the extent of the individual’s illness. The same is true for a patient with dementia, who might be disruptive and loud, yet clearly is not in control of their behavior.

Koekkoek et al5 reviewed 94 articles that focused on difficult patients seen in mental health settings. Most patients were male (60% to 68%), and most were age 26 to 32 years. Diagnoses of psychotic disorders and personality disorders were the most frequent, while mood and other disorders were less common. In 1 of the studies reviewed, 6% of psychiatric inpatients were considered difficult. Koekkoek et al5 proposed that there are 3 groups of difficult patients:

- care avoiders: patients with psychosis who lack insight

- care seekers: patients who are chronically ill who have trouble maintaining a steady relationship with their caregivers

- care claimers: patients who do not require long-term care, but need housing, medication, or a “declaration of incompetence.”

Physician factors

Physicians are frequent contributors to bad interactions with their patients.2,7,8 They can become angry or defensive because of burnout, stress, or frustration, which might lead them to snap or otherwise respond inappropriately to their patients. Many physicians are overworked, sleep-deprived, or busier than they would prefer. Personal problems can be preoccupying and contribute to a physician being ill-tempered or distracted (eg, marital or family problems). Some physicians are simply poor communicators and might not understand the need to adapt their communication style to their patient, instead using medical jargon the patient does not understand. Ideally, physicians should modify their language to suit the patient’s level of education, degree of medical sophistication, and cultural background.

Continue to: A physician's personality traits...

A physician’s personality traits could clash with those of the patient, particularly if the physician is especially rigid or obsessional. Rather than “going with the flow,” the overly rigid physician might become impatient with patients who fail to understand diagnostic assessments or treatment recommendations. Inefficient physicians might not be able to keep up with the daily schedule, which could fuel impatience and perhaps even lead them to think that the patient is taking too much of their valuable time. Some might not know how to convey empathy, for example when giving bad news (“The tests show you have cancer…”). Others fail to make consistent eye contact with patients without understanding its importance to communication, a problem made worse by the use of electronic medical record systems (EMRs).

Systems issues

Systems issues also contribute to suboptimal physician-patient interactions, and some issues can be attributed to administrative problems. Examples of systems issues include:

- when a patient has difficulty making an appointment and is forced to listen to a confusing menu of choices

- a busy clinic that can only offer a patient an appointment 6 months away

- crowded or noisy waiting rooms

- language barriers for patients whose primary langage is not English. Not having access to an interpreter can exacerbate their frustration

- the use of EMRs is a growing threat to positive physician-patient interactions, yet their influence is often ignored. Widely disliked by physicians,10 EMRs are required in all but the smallest independent practice settings. Many busy physicians focus their attention on the computer, giving the patient the impression that the physician is not listening to them. Many patients conclude that they are less important than the process.

The consequences of difficult interactions

Following a bad interaction, dissatisfied patients are more likely to leave the clinic or hospital and ignore medical advice. These patients might then show up in crowded emergency departments, which may lead to poor use of health care resources. For physicians, challenging situations sap their emotional energy, cause demoralization, and interfere with their sense of job fulfillment. In extreme cases, such feelings might lead the physician to dislike and even avoid the patient.

How to manage challenging situations

Taking the following steps can help physicians work through challenging situations with their patients.

Diagnose the problem. First, recognize the difficult situation, analyze it, and identify how the patient, the physician, and the system are contributing to a bad physician-patient interaction. Diagnosing the interactional difficulty should precede the diagnosis and management of the patient’s disease. Physicians should acknowledge their own contribution through their attitude or actions. Finally, determine if there are system issues that are contributing to the problem, or if it is the clinic or inpatient setting itself (eg, noisy inpatient unit).

Continue to: Maintain your cool

Maintain your cool. With any difficult interaction, a physician’s first obligation is to remain calm and professional, while modeling appropriate behavior. If the patient is angry or emotionally intense, talking over them or interrupting them only makes the situation worse. Try to see the interaction from the patient’s perspective. Both parties should work together to find a common ground.

Collaborate, respect boundaries, and empathize. One study of a group of 100 family physicians found that having the following 3 skills were essential to successfully managing situations with difficult patients11,12:

- the ability to collaborate (vs opposition)

- the appropriate use of power (vs misuse of power, or violation of boundaries by either party)

- the ability to empathize, which for most physicians involves understanding and validating the patient’s subjective experiences.

Although a description of the many facets of empathy (cognitive, affective, motivational) is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth pointing out that a patient’s positive perception of their physician’s empathy improves not only patient satisfaction but health outcomes.13 The Box describes a difficult patient whose actions changed through the collaboration and empathy of his treatment team.

Box 1

Mr. L, a 60-year-old veteran, is admitted to an inpatient unit following a suicide attempt that was prompted by eviction from his apartment. Mr. L is physically disabled and has difficulty walking without assistance. His main concern is his homelessness, and he insists that the inpatient team find a suitable “Americans with Disabilities (ADA)-compliant apartment” that he can afford on his $800 monthly income. He implies that he will kill himself if the team fails in that task. He makes it clear that his problems are the team’s problems. He is prescribed an antidepressant, and both his mood and reported suicidal ideations gradually resolve.

The team’s social worker finds an opening at a well-run veterans home, but Mr. L rejects it because he doesn’t want to “give up his independence.” The social worker finds a small apartment in a nearby community that is ADA-compliant, but Mr. L complains that it is small. He asks the resident psychiatrist, “Where will I put all my things?” The next day, after insulting the attending psychiatrist for failing to find an adequate apartment, Mr. L says from under the bedsheet: “How come none of you ever help me?”

Mr. L presents a challenge to the entire team. At times, he is rude, demanding, and entitled. The team recognizes that although he had served in the military with distinction, he is now alone after having divorced many years earlier, and nearly friendless because of his increasing disability. The team surmises that Mr. L lashes out due to frustration and feelings of powerlessness.

Resolving this conflict involves treating Mr. L with respect and listening without judgment. No one ever confronts him or argues with him. The team psychologist meets with him to help him work through his many losses. Closer to discharge, he is enrolled in several post-hospitalization programs to keep him connected with other veterans. At discharge, the hospital arranges for his belongings that had been in storage to be delivered to his new home. He is pleasant and social with his peers, and although he is still concerned about the size of the apartment, he thanks the team members for their care.

Verbalize the difficulty. It is important to openly discuss the problem. For example, “We both have very different views about how your symptoms should be investigated, and that’s causing some difficulty between us. Do you agree?” This approach names the “elephant in the room” and avoids casting blame. It also creates a sense of shared ownership by externalizing the problem from both the patient and physician. Verbalizing the difficulty can help build trust and pave the way to working together toward a common solution.

Consider other explanations for the patient’s behavior. For example, anger directed at a physician could be due to anxiety about an unrelated matter, such as the patient’s recent job loss or impending divorce. Psychiatrists might understand this behavior better as displacement, which is considered a maladaptive defense mechanism. It is important to listen to the patient and offer empathy, which will help the patient feel supported and build a rapport that can help to resolve the encounter.

Continue to: When helping patients...

When helping patients with multiple issues, which is a common scenario, the physician might start by asking, “What would you like to address today?”14 Keep a list of the issues so you do not forget the patient’s concerns, and then ask: “What do you think is going on?” Give patients time to verbalize their concerns. Physicians should:

- validate concerns: “I understand where you’re coming from.”

- offer empathy: “I can see how difficult this has been for you.”

- reframe: “Let me make sure I hear you correctly.”

- refocus: “Let’s agree on what we need to do at this visit.”

Find common ground. When the patient and physician have different ideas on diagnosis or treatment, finding common ground is another way to resolve a difficult encounter. Difficulties arise when there appears to be little common ground, which often results from unrealistic expectations. Patients might be seen as “demanding” or “manipulative”’ if they push for a diagnosis or treatment the doctor is not comfortable with. As soon as there is some overlap and common ground, the difficulty rapidly subsides.

Set clear boundaries and limits. Physicians should set limits on what patient behavior might “cross the line.” A “behavioral contract” (or “treatment contract”) can help by setting explicit expectations. For example, showing up late for appointments or inappropriately seeking drugs of abuse (eg, opioids, benzodiazepines) might be identified as violations of the contract. Once the contract is set, the patient should be asked to restate key components. Clarify any confusion or barriers to compliance and define clear expectations. The patient should be informed of potential consequences of contract violations, including termination.

Staff members involved in the patient’s care should agree with the terms of any behavioral contract, and should receive a copy of it. Patients should have “buy in,” meaning that they have had an opportunity to provide input to the contract and have agreed to its elements. Both the physician and patient should sign the document.

When all else fails

When there is a breakdown in rapport that makes it difficult or impossible to continue offering treatment, consider termination. This could be due to threatening or abusive patient behavior, sexual advances, repeated no-shows, treatment noncompliance that jeopardizes patient safety, refusal to follow the treatment plan, or violating the terms of a behavioral contract. In some settings, it might be the failure to pay bills.

Continue to: If a patient is unable to...

If a patient is unable to follow the contract, the physician should explore possible extenuating circumstances. The physician should seek to remedy the problem and involve other team members if possible (eg, case manager, nurse), advising a patient about behaviors that could lead to termination.

If the problem is irremediable, notify the patient in writing, give them time to find another physician, and facilitate the transfer of care.15 Take steps to prevent the patient from running out of any medications associated with withdrawal or discontinuation syndromes (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines) during the care transition. While there is no requirement regarding the amount of time allowed, at least 30 days is typical.

Bottom Line

Difficult patient interactions are common and unavoidable. Physicians should acknowledge and recognize contributing factors in such encounters—including their own role. When handling such situations, physicians should remain calm and model appropriate behavior. Improving communication, offering empathy, and validating the patient’s concerns can help resolve factors that contribute to poor patient interactions. If efforts to remediate the physician-patient relationship fail, termination may be necessary.

Related Resources

- Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

- Pereira MR, Figueiredo AF. Challenging patient-doctor interactions in psychiatry – difficult patient syndrome. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(supplement):S719. doi. org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1297

“I did not like those patients… They made me angry and I found myself irritated to experience them as they seemed so distant from myself and from all that is human. This is an astonishing intolerance which brands me a poor psychiatrist.”

Sigmund Freud, Letter to István Hollós (1928)

While Freud was referring to psychotic patients,1 his evident frustration shows that difficult and challenging patients have vexed even the best of us. All physicians and other clinicians will experience patient encounters that lead to anger or frustration, or even challenge their sense of equanimity and professional identity. In short, difficult and challenging patient interactions are unavoidable, regardless of the physician’s discipline.2-5 At times, physicians might struggle with demanding, unpleasant, ungrateful, and possibly dangerous patients, while sometimes the struggle is with the patient’s family members. No physician is immune to the problem, which makes it crucial to learn to anticipate and manage difficult patient interactions, skills which are generally not taught in medical schools or residency programs.

One prospective study of clinic patients found that up to 15% of patient encounters are deemed “difficult.”6 Common scenarios include patients (or their relatives) who seek certain tests after researching symptoms online, threats of legal or social media action in response to feeling that the physician is not listening to them, demands for a second opinion after disagreeing with the physician’s diagnosis, and mistrust of doctors after presenting with symptoms and not receiving a diagnosis. It is also common to care for patients who focus on negative outcomes or fail to adhere to treatment recommendations. These encounters can make physicians feel stressed out, disrespected, abused, or even fearful if threatened. Some physicians may come to feel they are trapped in a hostile work environment with little support from their supervisors or administrators. Patients often have a complaint office or department to turn to, but there is no equivalent for physicians, who are expected to soldier on regardless.

This article highlights a model that describes poor physician-patient encounters, factors contributing to these issues, how to manage these difficult interactions, and what to do if the relationship cannot be remediated.

Describing the ‘difficult’ patient

In a landmark 1978 paper, Groves7 provided one of the first descriptions of “difficult” patients. His colorful observations continue to provide useful insights. Groves emphasized that most medical texts ignore the issue of difficult patients and provide little or no guidance—which is still true 43 years later. He observed that physicians cannot avoid occasional negative feelings toward some patients. Further, Groves suggested that countertransference is often at the root of hateful reactions, a process he defines as “conscious or unconscious unbidden and unwanted hostile or sexual feelings toward the patient.”7Table 17 outlines how Groves divided “hateful” patients into several categories, and how physicians might respond to such patients.

A model for understanding difficult patient encounters

Adams and Murray2 created a model to help explain interactions with difficult or challenging patients that consists of 3 elements: the patient, the physician, and the system (ie, situation or environment). Hull and Broquet8 and Hardavella et al9 later adapted the model and described its components (Table 22,8,9).

Continue to: When considering...

When considering difficult interactions, it is important to be aware that all 3 components could interact, or merely 1 or 2 could come into play, but all should be explored as possible contributing factors.

Patient factors

The patient’s role in initiating or maintaining a problematic interaction should be explored. While some physicians are tempted to conclude that a personality disorder underlies difficult interactions, research shows a more complex picture. First, not all difficult patients have a psychiatric disorder, let alone a personality disorder. Jackson and Kroenke6 reported that among 74 difficult patients in an ambulatory clinic, 29% had a depressive disorder or anxiety disorder, with 11% experiencing 2 or more disorders. Major depressive disorder was present in 8.4% patients, other depressive disorders in 17.4%, panic disorder in 1.4%, and other anxiety disorders in 14.2%.6 These researchers found that difficult patient interactions were associated with the presence of a psychiatric disorder, especially depressive or anxiety disorders, and multiple physical symptoms.

Importantly, difficult patients are not unique to psychiatry, and are found in all medical disciplines and every type of practice situation. Some problematic patients have a substance use disorder, and their difficulty might stem from intoxication, withdrawal, or drug-seeking behaviors. Psychotic disorders can be the source of difficult interactions, typically resulting from the patient’s symptoms (ie, hallucinations, delusions, or bizarre behavior). Physicians tend to be forgiving toward these patients because they understand the extent of the individual’s illness. The same is true for a patient with dementia, who might be disruptive and loud, yet clearly is not in control of their behavior.

Koekkoek et al5 reviewed 94 articles that focused on difficult patients seen in mental health settings. Most patients were male (60% to 68%), and most were age 26 to 32 years. Diagnoses of psychotic disorders and personality disorders were the most frequent, while mood and other disorders were less common. In 1 of the studies reviewed, 6% of psychiatric inpatients were considered difficult. Koekkoek et al5 proposed that there are 3 groups of difficult patients:

- care avoiders: patients with psychosis who lack insight

- care seekers: patients who are chronically ill who have trouble maintaining a steady relationship with their caregivers

- care claimers: patients who do not require long-term care, but need housing, medication, or a “declaration of incompetence.”

Physician factors

Physicians are frequent contributors to bad interactions with their patients.2,7,8 They can become angry or defensive because of burnout, stress, or frustration, which might lead them to snap or otherwise respond inappropriately to their patients. Many physicians are overworked, sleep-deprived, or busier than they would prefer. Personal problems can be preoccupying and contribute to a physician being ill-tempered or distracted (eg, marital or family problems). Some physicians are simply poor communicators and might not understand the need to adapt their communication style to their patient, instead using medical jargon the patient does not understand. Ideally, physicians should modify their language to suit the patient’s level of education, degree of medical sophistication, and cultural background.

Continue to: A physician's personality traits...

A physician’s personality traits could clash with those of the patient, particularly if the physician is especially rigid or obsessional. Rather than “going with the flow,” the overly rigid physician might become impatient with patients who fail to understand diagnostic assessments or treatment recommendations. Inefficient physicians might not be able to keep up with the daily schedule, which could fuel impatience and perhaps even lead them to think that the patient is taking too much of their valuable time. Some might not know how to convey empathy, for example when giving bad news (“The tests show you have cancer…”). Others fail to make consistent eye contact with patients without understanding its importance to communication, a problem made worse by the use of electronic medical record systems (EMRs).

Systems issues

Systems issues also contribute to suboptimal physician-patient interactions, and some issues can be attributed to administrative problems. Examples of systems issues include:

- when a patient has difficulty making an appointment and is forced to listen to a confusing menu of choices

- a busy clinic that can only offer a patient an appointment 6 months away

- crowded or noisy waiting rooms

- language barriers for patients whose primary langage is not English. Not having access to an interpreter can exacerbate their frustration

- the use of EMRs is a growing threat to positive physician-patient interactions, yet their influence is often ignored. Widely disliked by physicians,10 EMRs are required in all but the smallest independent practice settings. Many busy physicians focus their attention on the computer, giving the patient the impression that the physician is not listening to them. Many patients conclude that they are less important than the process.

The consequences of difficult interactions

Following a bad interaction, dissatisfied patients are more likely to leave the clinic or hospital and ignore medical advice. These patients might then show up in crowded emergency departments, which may lead to poor use of health care resources. For physicians, challenging situations sap their emotional energy, cause demoralization, and interfere with their sense of job fulfillment. In extreme cases, such feelings might lead the physician to dislike and even avoid the patient.

How to manage challenging situations

Taking the following steps can help physicians work through challenging situations with their patients.

Diagnose the problem. First, recognize the difficult situation, analyze it, and identify how the patient, the physician, and the system are contributing to a bad physician-patient interaction. Diagnosing the interactional difficulty should precede the diagnosis and management of the patient’s disease. Physicians should acknowledge their own contribution through their attitude or actions. Finally, determine if there are system issues that are contributing to the problem, or if it is the clinic or inpatient setting itself (eg, noisy inpatient unit).

Continue to: Maintain your cool

Maintain your cool. With any difficult interaction, a physician’s first obligation is to remain calm and professional, while modeling appropriate behavior. If the patient is angry or emotionally intense, talking over them or interrupting them only makes the situation worse. Try to see the interaction from the patient’s perspective. Both parties should work together to find a common ground.

Collaborate, respect boundaries, and empathize. One study of a group of 100 family physicians found that having the following 3 skills were essential to successfully managing situations with difficult patients11,12:

- the ability to collaborate (vs opposition)

- the appropriate use of power (vs misuse of power, or violation of boundaries by either party)

- the ability to empathize, which for most physicians involves understanding and validating the patient’s subjective experiences.

Although a description of the many facets of empathy (cognitive, affective, motivational) is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth pointing out that a patient’s positive perception of their physician’s empathy improves not only patient satisfaction but health outcomes.13 The Box describes a difficult patient whose actions changed through the collaboration and empathy of his treatment team.

Box 1

Mr. L, a 60-year-old veteran, is admitted to an inpatient unit following a suicide attempt that was prompted by eviction from his apartment. Mr. L is physically disabled and has difficulty walking without assistance. His main concern is his homelessness, and he insists that the inpatient team find a suitable “Americans with Disabilities (ADA)-compliant apartment” that he can afford on his $800 monthly income. He implies that he will kill himself if the team fails in that task. He makes it clear that his problems are the team’s problems. He is prescribed an antidepressant, and both his mood and reported suicidal ideations gradually resolve.

The team’s social worker finds an opening at a well-run veterans home, but Mr. L rejects it because he doesn’t want to “give up his independence.” The social worker finds a small apartment in a nearby community that is ADA-compliant, but Mr. L complains that it is small. He asks the resident psychiatrist, “Where will I put all my things?” The next day, after insulting the attending psychiatrist for failing to find an adequate apartment, Mr. L says from under the bedsheet: “How come none of you ever help me?”

Mr. L presents a challenge to the entire team. At times, he is rude, demanding, and entitled. The team recognizes that although he had served in the military with distinction, he is now alone after having divorced many years earlier, and nearly friendless because of his increasing disability. The team surmises that Mr. L lashes out due to frustration and feelings of powerlessness.

Resolving this conflict involves treating Mr. L with respect and listening without judgment. No one ever confronts him or argues with him. The team psychologist meets with him to help him work through his many losses. Closer to discharge, he is enrolled in several post-hospitalization programs to keep him connected with other veterans. At discharge, the hospital arranges for his belongings that had been in storage to be delivered to his new home. He is pleasant and social with his peers, and although he is still concerned about the size of the apartment, he thanks the team members for their care.

Verbalize the difficulty. It is important to openly discuss the problem. For example, “We both have very different views about how your symptoms should be investigated, and that’s causing some difficulty between us. Do you agree?” This approach names the “elephant in the room” and avoids casting blame. It also creates a sense of shared ownership by externalizing the problem from both the patient and physician. Verbalizing the difficulty can help build trust and pave the way to working together toward a common solution.

Consider other explanations for the patient’s behavior. For example, anger directed at a physician could be due to anxiety about an unrelated matter, such as the patient’s recent job loss or impending divorce. Psychiatrists might understand this behavior better as displacement, which is considered a maladaptive defense mechanism. It is important to listen to the patient and offer empathy, which will help the patient feel supported and build a rapport that can help to resolve the encounter.

Continue to: When helping patients...

When helping patients with multiple issues, which is a common scenario, the physician might start by asking, “What would you like to address today?”14 Keep a list of the issues so you do not forget the patient’s concerns, and then ask: “What do you think is going on?” Give patients time to verbalize their concerns. Physicians should:

- validate concerns: “I understand where you’re coming from.”

- offer empathy: “I can see how difficult this has been for you.”

- reframe: “Let me make sure I hear you correctly.”

- refocus: “Let’s agree on what we need to do at this visit.”

Find common ground. When the patient and physician have different ideas on diagnosis or treatment, finding common ground is another way to resolve a difficult encounter. Difficulties arise when there appears to be little common ground, which often results from unrealistic expectations. Patients might be seen as “demanding” or “manipulative”’ if they push for a diagnosis or treatment the doctor is not comfortable with. As soon as there is some overlap and common ground, the difficulty rapidly subsides.

Set clear boundaries and limits. Physicians should set limits on what patient behavior might “cross the line.” A “behavioral contract” (or “treatment contract”) can help by setting explicit expectations. For example, showing up late for appointments or inappropriately seeking drugs of abuse (eg, opioids, benzodiazepines) might be identified as violations of the contract. Once the contract is set, the patient should be asked to restate key components. Clarify any confusion or barriers to compliance and define clear expectations. The patient should be informed of potential consequences of contract violations, including termination.

Staff members involved in the patient’s care should agree with the terms of any behavioral contract, and should receive a copy of it. Patients should have “buy in,” meaning that they have had an opportunity to provide input to the contract and have agreed to its elements. Both the physician and patient should sign the document.

When all else fails

When there is a breakdown in rapport that makes it difficult or impossible to continue offering treatment, consider termination. This could be due to threatening or abusive patient behavior, sexual advances, repeated no-shows, treatment noncompliance that jeopardizes patient safety, refusal to follow the treatment plan, or violating the terms of a behavioral contract. In some settings, it might be the failure to pay bills.

Continue to: If a patient is unable to...

If a patient is unable to follow the contract, the physician should explore possible extenuating circumstances. The physician should seek to remedy the problem and involve other team members if possible (eg, case manager, nurse), advising a patient about behaviors that could lead to termination.

If the problem is irremediable, notify the patient in writing, give them time to find another physician, and facilitate the transfer of care.15 Take steps to prevent the patient from running out of any medications associated with withdrawal or discontinuation syndromes (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines) during the care transition. While there is no requirement regarding the amount of time allowed, at least 30 days is typical.

Bottom Line

Difficult patient interactions are common and unavoidable. Physicians should acknowledge and recognize contributing factors in such encounters—including their own role. When handling such situations, physicians should remain calm and model appropriate behavior. Improving communication, offering empathy, and validating the patient’s concerns can help resolve factors that contribute to poor patient interactions. If efforts to remediate the physician-patient relationship fail, termination may be necessary.

Related Resources

- Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

- Pereira MR, Figueiredo AF. Challenging patient-doctor interactions in psychiatry – difficult patient syndrome. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(supplement):S719. doi. org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1297

1. Dupont J. Ferenczi’s madness. Contemp Psychoanal. 1988;24(2):250-261.

2. Adams J, Murray R. The difficult diagnosis: the general approach to the difficult patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1998;16(4):689-700.

3. Davies M. Managing challenging interactions with patients. BMJ. 2013;347:f4673. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f4673

4. Chou C. Dealing with the “difficult” patient. Wisc Med J. 2004;103:35-38.

5. Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

6. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounter in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(10):1069-1075.

7. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Eng J Med. 1978;298:883-887.

8. Hull S, Broquet K. How to manage difficult encounters. Fam Prac Manag. 2007;14(6):30-34.

9. Hardavella G, Aamli-Gaagnat A, Frille A, et al. Top tips to deal with challenging situations: doctor patient interactions. Breathe. 2017;13(2):129-135.

10. Black DW, Balon R. Editorial: electronic medical records (EMRs) and the psychiatrist shortage. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2018;30(4):257-259.

11. Elder N, Ricer R, Tobias B. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):533-541.

12. Campbell RJ. Campbell’s Psychiatric Dictionary. 8th Edition. Oxford University Press; 2004:219-220.

13. Decety J, Fotopoulou A. Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: unifying theories. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457

14. Klugman B. The difficult patient. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/office-of-continuing-medical-education/pdfs/cme-primary-care-days/e2-the-difficult-patient.pdf

15. Mossman D, Farrell HM, Gilday E. ‘Firing’ a patient: may psychiatrists unilaterally terminate care? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):18-29.

1. Dupont J. Ferenczi’s madness. Contemp Psychoanal. 1988;24(2):250-261.

2. Adams J, Murray R. The difficult diagnosis: the general approach to the difficult patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1998;16(4):689-700.

3. Davies M. Managing challenging interactions with patients. BMJ. 2013;347:f4673. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f4673

4. Chou C. Dealing with the “difficult” patient. Wisc Med J. 2004;103:35-38.

5. Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

6. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounter in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(10):1069-1075.

7. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Eng J Med. 1978;298:883-887.

8. Hull S, Broquet K. How to manage difficult encounters. Fam Prac Manag. 2007;14(6):30-34.

9. Hardavella G, Aamli-Gaagnat A, Frille A, et al. Top tips to deal with challenging situations: doctor patient interactions. Breathe. 2017;13(2):129-135.

10. Black DW, Balon R. Editorial: electronic medical records (EMRs) and the psychiatrist shortage. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2018;30(4):257-259.

11. Elder N, Ricer R, Tobias B. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):533-541.

12. Campbell RJ. Campbell’s Psychiatric Dictionary. 8th Edition. Oxford University Press; 2004:219-220.

13. Decety J, Fotopoulou A. Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: unifying theories. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457

14. Klugman B. The difficult patient. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/office-of-continuing-medical-education/pdfs/cme-primary-care-days/e2-the-difficult-patient.pdf

15. Mossman D, Farrell HM, Gilday E. ‘Firing’ a patient: may psychiatrists unilaterally terminate care? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):18-29.

A clinical approach to pharmacotherapy for personality disorders

DSM-5 defines personality disorders (PDs) as the presence of an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that “deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment.”1 As a general rule, PDs are not limited to episodes of illness, but reflect an individual’s long-term adjustment. These disorders occur in 10% to 15% of the general population; the rates are especially high in health care settings, in criminal offenders, and in those with a substance use disorder (SUD).2 PDs nearly always have an onset in adolescence or early adulthood and tend to diminish in severity with advancing age. They are associated with high rates of unemployment, homelessness, divorce and separation, domestic violence, substance misuse, and suicide.3

Psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for PDs, but there has been growing interest in using pharmacotherapy to treat PDs. While much of the PD treatment literature focuses on borderline PD,4-9 this article describes diagnosis, potential pharmacotherapy strategies, and methods to assess response to treatment for patients with all types of PDs.

Recognizing and diagnosing personality disorders

The diagnosis of a PD requires an understanding of DSM-5 criteria combined with a comprehensive psychiatric history and mental status examination. The patient’s history is the most important basis for diagnosing a PD.2 Collateral information from relatives or friends can help confirm the severity and pervasiveness of the individual’s personality problems. In some patients, long-term observation might be necessary to confirm the presence of a PD. Some clinicians are reluctant to diagnose PDs because of stigma, a problem common among patients with borderline PD.10,11

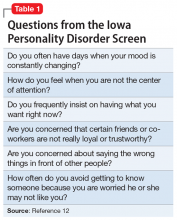

To screen for PDs, a clinician might ask the patient about problems with interpersonal relationships, sense of self, work, affect, impulse control, and reality testing. Table 112 lists general screening questions for the presence of a PD from the Iowa Personality Disorders Screen. Structured diagnostic interviews and self-report assessments could boost recognition of PDs, but these tools are rarely used outside of research settings.13,14

The PD clusters

DSM-5 divides 10 PDs into 3 clusters based on shared phenomenology and diagnostic criteria. Few patients have a “pure” case in which they meet criteria for only a single personality disorder.1

Cluster A. “Eccentric cluster” disorders are united by social aversion, a failure to form close attachments, or paranoia and suspiciousness.15 These include paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal PD. Low self-awareness is typical. There are no treatment guidelines for these disorders, although there is some clinical trial data for schizotypal PD.

Cluster B. “Dramatic cluster” disorders share dramatic, emotional, and erratic characteristics.14 These include narcissistic, antisocial, borderline, and histrionic PD. Antisocial and narcissistic patients have low self-awareness. There are treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, and a variety of clinical trial data is available for the latter.15

Continue to: Cluster C

Cluster C. “Anxious cluster” disorders are united by anxiousness, fearfulness, and poor self-esteem. Many of these patients also display interpersonal rigidity.15 These disorders include avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive PD. There are no treatment guidelines or clinical trial data for these disorders.

Why consider pharmacotherapy for personality disorders?

The consensus among experts is that psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for PDs.15 Despite significant gaps in the evidence base, there has been a growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. For example, research shows that >90% of patients with borderline PD are prescribed medication, most typically antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, stimulants, or sedative-hypnotics.16,17

Increased interest in pharmacotherapy for PDs could be related to research showing the importance of underlying neurobiology, particularly for antisocial and borderline PD.18,19 This work is complemented by genetic research showing the heritability of PD traits and disorders.20,21 Another factor could be renewed interest in dimensional approaches to the classification of PDs, as exemplified by DSM-5’s alternative model for PDs.1 This approach aligns with some expert recommendations to focus on treating PD symptom dimensions, rather than the syndrome itself.22

Importantly, no psychotropic medication is FDA-approved for the treatment of any PD. For that reason, prescribing medication for a PD is “off-label,” although prescribing a medication for a comorbid disorder for which the drug has an FDA-approved indication is not (eg, prescribing an antidepressant for major depressive disorder [MDD]).

Principles for prescribing

Despite gaps in research data, general principles for using medication to treat PDs have emerged from treatment guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD, clinical trial data, reviews and meta-analyses, and expert opinion. Clinicians should address the following considerations before prescribing medication to a patient with a PD.

Continue to: PD diagnosis

PD diagnosis. Has the patient been properly assessed and diagnosed? While history is the most important basis for diagnosis, the clinician should be familiar with the PDs and DSM-5 criteria. Has the patient been informed of the diagnosis and its implications for treatment?

Patient interest in medication. Is the patient interested in taking medication? Patients with borderline PD are often prescribed medication, but there are sparse data for the other PDs. The patient might have little interest in the PD diagnosis or its treatment.

Comorbidity. Has the patient been assessed for comorbid psychiatric disorders that could interfere with medication use (ie, an SUD) or might be a focus of treatment (eg, MDD)? Patients with PDs typically have significant comorbidity that a thorough evaluation will uncover.

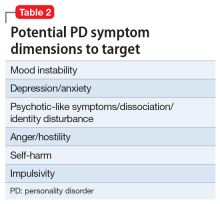

PD symptom dimensions. Has the patient been assessed to determine cognitive or behavioral symptom dimensions of their PD? One or more symptom dimension(s) could be the focus of treatment. Table 2 lists examples of PD symptom dimensions.

Strategies to guide prescribing

Strategies to help guide prescribing include targeting any comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions (eg, impulsive aggression), choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself.

Continue to: Targeting comorbid disorders

Targeting comorbid disorders. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for antisocial and borderline PD recommend that clinicians focus on treating comorbid disorders, a position echoed in Cochrane and other reviews.4,9,22-26 For example, a patient with borderline PD experiencing a major depressive episode could be treated with an antidepressant. Targeting the depressive symptoms could boost the patient’s mood, perhaps lessening the individual’s PD symptoms or reducing their severity.

Targeting important symptom dimensions. For patients with borderline PD, several guidelines and reviews have suggested that treatment should focus on emotional dysregulation and impulsive aggression (mood stabilizers, antipsychotics), or cognitive-perceptual symptoms (antipsychotics).4-6,15 There is some evidence that mood stabilizers or second-generation antipsychotics could help reduce impulsive aggression in patients with antisocial PD.27

Choosing medication based on similarity to another disorder known to respond to medication. Avoidant PD overlaps with social anxiety disorder and can be conceptualized as a chronic, pervasive social phobia. Avoidant PD might respond to a medication known to be effective for treating social anxiety disorder, such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or venlafaxine.28 Treating obsessive-compulsive PD with an SSRI is another example of this strategy, as 1 small study of fluvoxamine suggests.29 Obsessive-compulsive PD is common in persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and overlap includes preoccupation with orders, rules, and lists, and an inability to throw things out.

Targeting the PD syndrome. Another strategy is to target the PD itself. Clinical trial data suggest the antipsychotic risperidone can reduce the symptoms of schizotypal PD.30 Considering that this PD has a genetic association with schizophrenia, it is not surprising that the patient’s ideas of reference, odd communication, or transient paranoia might respond to an antipsychotic. Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support the use of the second-generation antipsychotics aripiprazole and quetiapine to treat BPD.31,32 While older guidelines4,5 supported the use of the mood stabilizer lamotrigine, a recent RCT found that it was no more effective than placebo for borderline PD or its symptom dimensions.33

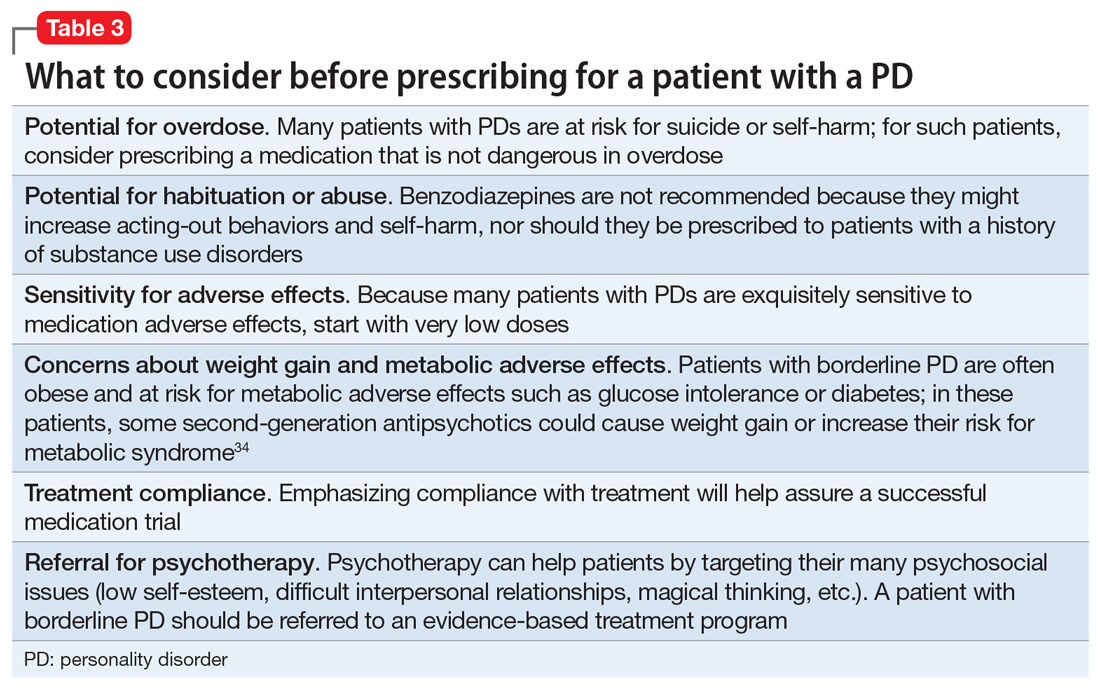

What to do before prescribing

Before writing a prescription, the clinician and patient should discuss the presence of a PD and the desirability of treatment. The patient should understand the limited evidence base and know that medication prescribed for a PD is off-label. The clinician should discuss medication selection and its rationale, and whether the medication is targeting a comorbid disorder, symptom dimension(s), or the PD itself. Additional considerations for prescribing for patients with PDs are listed in Table 3.34

Continue to: Avoid polypharmacy

Avoid polypharmacy. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed multiple psychotropic medications.16,17 This approach leads to greater expense and more adverse effects, and is not evidence-based.

Avoid benzodiazepines. Many patients with borderline PD are prescribed benzodiazepines, often as part of a polypharmacy regimen. These drugs can cause disinhibition, thereby increasing acting-out behaviors and self-harm.35 Also, patients with PDs often have SUDs, which is a contraindication for benzodiazepine use.

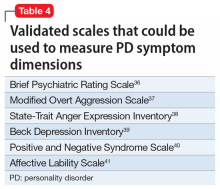

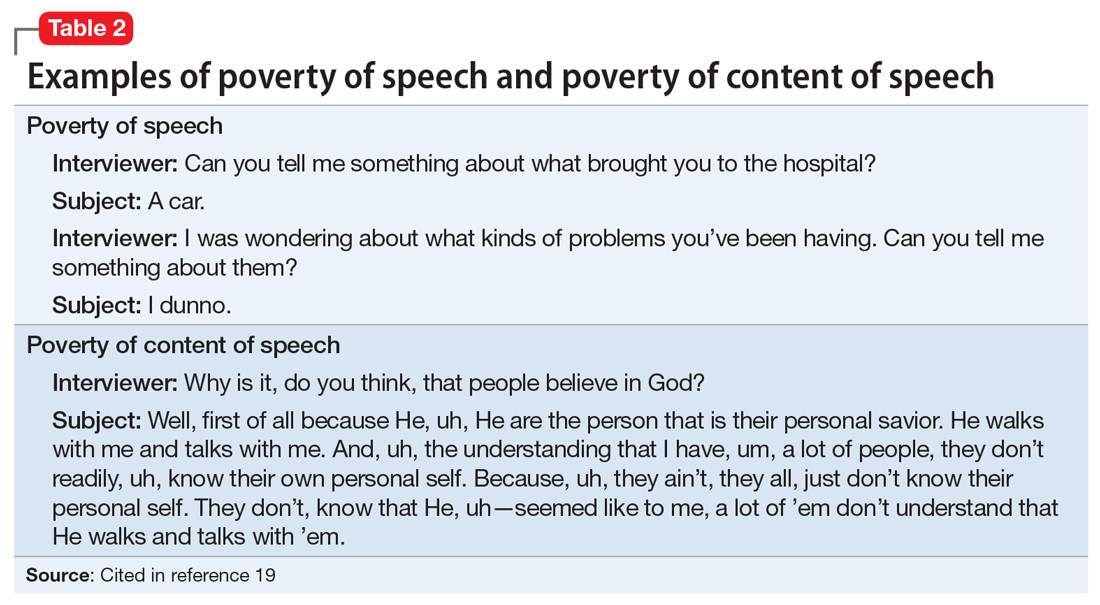

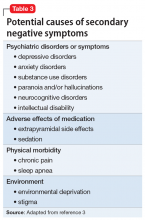

Rate the patient’s improvement. Both the patient and clinician can benefit from monitoring symptomatic improvement. Several validated scales can be used to rate depression, anxiety, impulsivity, mood lability, anger, and aggression (Table 436-41).Some validated scales for borderline PD align with DSM-5 criteria. Two such widely used instruments are the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD)42 and the self-rated Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST).43 Each has questions that could be pulled to rate a symptom dimension of interest, such as affective instability, anger dyscontrol, or abandonment fears (Table 542,43).

A visual analog scale is easy to use and can target symptom dimensions of interest.44 For example, a clinician could use a visual analog scale to rate mood instability by asking a patient to rate their mood severity by making a mark along a 10-cm line (0 = “Most erratic emotions I have experienced,” 10 = “Most stable I have ever experienced my emotions to be”). This score can be recorded at baseline and subsequent visits.

Take-home points

PDs are common in the general population and health care settings. They are underrecognized by the general public and mental health professionals, often because of stigma. Clinicians could boost their recognition of these disorders by embedding simple screening questions in their patient assessments. Many patients with PDs will be interested in pharmacotherapy for their disorder or symptoms. Treatment strategies include targeting the comorbid disorder(s), targeting important PD symptom dimensions, choosing medication based on the similarity of the PD to another disorder known to respond to medication, and targeting the PD itself. Each strategy has its limitations and varying degrees of empirical support. Treatment response can be monitored using validated scales or a visual analog scale.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although psychotherapy is the first-line treatment and no medications are FDAapproved for treating personality disorders (PDs), there has been growing interest in using psychotropic medication to treat PDs. Strategies for pharmacotherapy include targeting comorbid disorders, PD symptom dimensions, or the PD itself. Choice of medication can be based on the similarity of the PD with another disorder known to respond to medication.

Related Resources

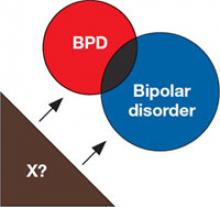

- Correa Da Costa S, Sanches M, Soares JC. Bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):26-29,35-39.

- Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Black DW, Andreasen N. Personality disorders. In: Black DW, Andreasen N. Introductory textbook of psychiatry, 7th edition. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2020:410-423.

3. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord 2004;18(3):226-239.

4. Lieb K, Völlm B, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):4-12.

5. Vita A, De Peri L, Sacchetti E. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and placebo on the symptom dimensions of borderline personality disorder – a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and open-label trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):613-624.

6. Stoffers JM, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder – current evidence and recent trends. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1):534.

7. Hancock-Johnson E, Griffiths C, Picchioni M. A focused systematic review of pharmacological treatment for borderline personality disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):345-356.

8. Black DW, Paris J, Schulz SC. Personality disorders: evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M, ed. Cognitive behavioral psychopharmacology: the clinical practice of evidence-based biopsychosocial integration. John Wiley & Sons; 2018:137-165.

9. Stoffers-Winterling J, Sorebø OJ, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: an update of published, unpublished and ongoing studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(8):37.

10. Lewis G, Appleby L. Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:44-49.

11. Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(3):67-74.

12. Langbehn DR, Pfohl BM, Reynolds S, et al. The Iowa Personality Disorder Screen: development and preliminary validation of a brief screening interview. J Pers Disord. 1999;13(1):75-89.

13. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV). American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Part II: multisite test-retest reliability study. J Pers Disord. 1995;9(2):92-104.

15. Bateman A, Gunderson J, Mulder R. Treatment of personality disorders. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):735-743.

16. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Treatment rates for patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality disorders: a 16-year study. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(1):15-20.

17. Black DW, Allen J, McCormick B, et al. Treatment received by persons with BPD participating in a randomized clinical trial of the Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving programme. Person Ment Health. 2011;5(3):159-168.