User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Medication-induced rhabdomyolysis

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Ms. A, age 32, has a history of anxiety, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder. She is undergoing treatment with lamotrigine 200 mg/d at bedtime, aripiprazole 5 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, clonazepam 0.5 mg twice a day, and hydroxyzine 25 mg twice a day. She presents to the emergency department with myalgia, left upper and lower extremity numbness, and weakness. These symptoms started at approximately 3

Ms. A’s vital signs are hemodynamically stable, but her pulse is 113 bpm. On examination, she appears anxious and has decreased sensation in her upper and lower extremities, with 3/5 strength on the left side. Her laboratory results indicate mild leukocytosis, hyponatremia (129 mmol/L; reference range 136 to 145 mmol/L), and elevations in serum creatinine (3.7 mg/dL; reference range 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (654 U/L; reference range 10 to 42 U/L), alanine transaminase (234 U/L; reference range 10 to 60 U/L), and troponin (2.11 ng/mL; reference range 0 to 0.04 ng/mL). A urinalysis reveals darkly colored urine with large red blood cells.

Neurology and Cardiology consultations are requested to rule out stroke and acute coronary syndromes. A computed tomography scan of the head shows no acute intracranial findings. Her creatinine kinase (CK) level is elevated (>42,670 U/L; reference range 22 to 232 U/L), which prompts a search for causes of rhabdomyolysis, a breakdown of muscle tissue that releases muscle fiber contents into the blood. Ms. A reports no history of recent trauma or strenuous exercise. Infectious, endocrine, and other workups are negative. After a consult to Psychiatry, the treating clinicians suspect that the most likely cause for rhabdomyolysis is aripiprazole.

Ms. A is treated with IV isotonic fluids. Aripiprazole is stopped and her CK levels are closely monitored. CK levels continue to trend down, and by Day 6 of hospitalization her CK level is 1,648 U/L. Her transaminase levels also improve; these elevations are considered likely secondary to rhabdomyolysis. Because there is notable improvement in CK and transaminase levels after stopping aripiprazole, Ms. A is discharged and instructed to follow up with a psychiatrist for further management.

Aripiprazole and rhabdomyolysis

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, an estimated 2.8% of the US population has bipolar disorder and 0.24% to 0.64% has schizophrenia.1,2 Antipsychotics are often used to treat these disorders. The prevalence of antipsychotic use in the general adult population is 1.6%.3 The use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) has increased over recent years with the availability of a variety of formulations, such as immediate-release injectable, long-acting injectable, and orally disintegrating tablets in addition to the customary oral tablets. SGAs can cause several adverse effects, including weight gain, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, QTc prolongation, extrapyramidal side effects, myocarditis, agranulocytosis, cataracts, and sexual adverse effects.4

Antipsychotic use is more commonly associated with serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome than it is with rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis as an adverse effect of antipsychotic use has not been well understood or reported. One study found the prevalence of rhabdomyolysis was approximately 10% among patients who received an antipsychotic medication.5 There have been 4 case reports of clozapine use, 6 of olanzapine use, and 3 of aripiprazole use associated with rhabdomyolysis.6-8 Therefore, this would be the fourth case report to describe aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis.

Aripiprazole is FDA-approved for the treatment of schizophrenia. In this case report, we found that aripiprazole could have led to rhabdomyolysis. Aripiprazole is a quinoline derivative that acts by binding to the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors.9,10 It acts as a partial agonist at 5-HT1A receptors, an antagonist at 5-HT2A receptors, and a partial agonist and stabilizer at the D2 receptor. By binding to the dopamine receptor in its G protein–coupled state, aripiprazole blocks the receptor in the presence of excessive dopamine.11-13 The mechanism of how aripiprazole could cause rhabdomyolysis is unclear. One proposed mechanism is that it can increase the permeability of skeletal muscle by 5-HT2A antagonism. This leads to a decrease in glucose reuptake in the cell and increases the permeability of the cell membrane, leading to elevations in CK levels.14 Another proposed mechanism is that dopamine blockade in the nigrostriatal pathway can result in muscle stiffness, rigidity, parkinsonian-like symptoms, and akathisia, which can result in elevated CK levels.15 There are only 3 other published cases of aripiprazole-induced rhabdomyolysis; we hope this case report will add value to the available literature. More evidence is needed to establish the safety profile of aripiprazole.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of bipolar disorder among adults. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/bipolar-disorder#part_2605

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia#part_2543

3. Dennis JA, Gittner LS, Payne JD, et al. Characteristics of U.S. adults taking prescription antipsychotic medications, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2018. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):483. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02895-4

4. Willner K, Vasan S, Abdijadid S. Atypical antipsychotic agents. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448156/

5. Packard K, Price P, Hanson A. Antipsychotic use and the risk of rhabdomyolysis. J Pharm Pract 2014;27(5):501-512. doi: 10.1177/0897190013516509

6. Wu YF, Chang KY. Aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis in a patient with schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(3):E51.

7. Marzetti E, Bocchino L, Teramo S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis in a patient on aripiprazole with traumatic hip prosthesis luxation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):E40-E41.

8. Zhu X, Hu J, Deng S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and elevated liver enzymes after rapid correction of hyponatremia due to pneumonia and concurrent use of aripiprazole: a case report. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52(2):206. doi:10.1177/0004867417743342

9. Stahl SM. Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Application. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2000.

10. Stahl SM. “Hit-and-run” actions at dopamine receptors, part 1: mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(9):670-671.

11. Leysen JE, Janssen PM, Schotte A, et al. Interaction of antipsychotic drugs with neurotransmitter receptor sites in vitro and in vivo in relation to pharmacological and clinical effects: role of 5HT2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1993;112(1 Suppl):S40-S54.

12. Millan MJ. Improving the treatment of schizophrenia: focus on serotonin (5-HT)(1A) receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295(3):853-861.

13. Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70(2):83-244.

14. Meltzer HY, Cola PA, Parsa M. Marked elevations of serum creatine kinase activity associated with antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15(4):395-405.

15. Devarajan S, Dursun SM. Antipsychotic drugs, serum creatine kinase (CPK) and possible mechanisms. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000;152(1):122.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Ms. A, age 32, has a history of anxiety, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder. She is undergoing treatment with lamotrigine 200 mg/d at bedtime, aripiprazole 5 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, clonazepam 0.5 mg twice a day, and hydroxyzine 25 mg twice a day. She presents to the emergency department with myalgia, left upper and lower extremity numbness, and weakness. These symptoms started at approximately 3

Ms. A’s vital signs are hemodynamically stable, but her pulse is 113 bpm. On examination, she appears anxious and has decreased sensation in her upper and lower extremities, with 3/5 strength on the left side. Her laboratory results indicate mild leukocytosis, hyponatremia (129 mmol/L; reference range 136 to 145 mmol/L), and elevations in serum creatinine (3.7 mg/dL; reference range 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (654 U/L; reference range 10 to 42 U/L), alanine transaminase (234 U/L; reference range 10 to 60 U/L), and troponin (2.11 ng/mL; reference range 0 to 0.04 ng/mL). A urinalysis reveals darkly colored urine with large red blood cells.

Neurology and Cardiology consultations are requested to rule out stroke and acute coronary syndromes. A computed tomography scan of the head shows no acute intracranial findings. Her creatinine kinase (CK) level is elevated (>42,670 U/L; reference range 22 to 232 U/L), which prompts a search for causes of rhabdomyolysis, a breakdown of muscle tissue that releases muscle fiber contents into the blood. Ms. A reports no history of recent trauma or strenuous exercise. Infectious, endocrine, and other workups are negative. After a consult to Psychiatry, the treating clinicians suspect that the most likely cause for rhabdomyolysis is aripiprazole.

Ms. A is treated with IV isotonic fluids. Aripiprazole is stopped and her CK levels are closely monitored. CK levels continue to trend down, and by Day 6 of hospitalization her CK level is 1,648 U/L. Her transaminase levels also improve; these elevations are considered likely secondary to rhabdomyolysis. Because there is notable improvement in CK and transaminase levels after stopping aripiprazole, Ms. A is discharged and instructed to follow up with a psychiatrist for further management.

Aripiprazole and rhabdomyolysis

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, an estimated 2.8% of the US population has bipolar disorder and 0.24% to 0.64% has schizophrenia.1,2 Antipsychotics are often used to treat these disorders. The prevalence of antipsychotic use in the general adult population is 1.6%.3 The use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) has increased over recent years with the availability of a variety of formulations, such as immediate-release injectable, long-acting injectable, and orally disintegrating tablets in addition to the customary oral tablets. SGAs can cause several adverse effects, including weight gain, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, QTc prolongation, extrapyramidal side effects, myocarditis, agranulocytosis, cataracts, and sexual adverse effects.4

Antipsychotic use is more commonly associated with serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome than it is with rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis as an adverse effect of antipsychotic use has not been well understood or reported. One study found the prevalence of rhabdomyolysis was approximately 10% among patients who received an antipsychotic medication.5 There have been 4 case reports of clozapine use, 6 of olanzapine use, and 3 of aripiprazole use associated with rhabdomyolysis.6-8 Therefore, this would be the fourth case report to describe aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis.

Aripiprazole is FDA-approved for the treatment of schizophrenia. In this case report, we found that aripiprazole could have led to rhabdomyolysis. Aripiprazole is a quinoline derivative that acts by binding to the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors.9,10 It acts as a partial agonist at 5-HT1A receptors, an antagonist at 5-HT2A receptors, and a partial agonist and stabilizer at the D2 receptor. By binding to the dopamine receptor in its G protein–coupled state, aripiprazole blocks the receptor in the presence of excessive dopamine.11-13 The mechanism of how aripiprazole could cause rhabdomyolysis is unclear. One proposed mechanism is that it can increase the permeability of skeletal muscle by 5-HT2A antagonism. This leads to a decrease in glucose reuptake in the cell and increases the permeability of the cell membrane, leading to elevations in CK levels.14 Another proposed mechanism is that dopamine blockade in the nigrostriatal pathway can result in muscle stiffness, rigidity, parkinsonian-like symptoms, and akathisia, which can result in elevated CK levels.15 There are only 3 other published cases of aripiprazole-induced rhabdomyolysis; we hope this case report will add value to the available literature. More evidence is needed to establish the safety profile of aripiprazole.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Ms. A, age 32, has a history of anxiety, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder. She is undergoing treatment with lamotrigine 200 mg/d at bedtime, aripiprazole 5 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, clonazepam 0.5 mg twice a day, and hydroxyzine 25 mg twice a day. She presents to the emergency department with myalgia, left upper and lower extremity numbness, and weakness. These symptoms started at approximately 3

Ms. A’s vital signs are hemodynamically stable, but her pulse is 113 bpm. On examination, she appears anxious and has decreased sensation in her upper and lower extremities, with 3/5 strength on the left side. Her laboratory results indicate mild leukocytosis, hyponatremia (129 mmol/L; reference range 136 to 145 mmol/L), and elevations in serum creatinine (3.7 mg/dL; reference range 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (654 U/L; reference range 10 to 42 U/L), alanine transaminase (234 U/L; reference range 10 to 60 U/L), and troponin (2.11 ng/mL; reference range 0 to 0.04 ng/mL). A urinalysis reveals darkly colored urine with large red blood cells.

Neurology and Cardiology consultations are requested to rule out stroke and acute coronary syndromes. A computed tomography scan of the head shows no acute intracranial findings. Her creatinine kinase (CK) level is elevated (>42,670 U/L; reference range 22 to 232 U/L), which prompts a search for causes of rhabdomyolysis, a breakdown of muscle tissue that releases muscle fiber contents into the blood. Ms. A reports no history of recent trauma or strenuous exercise. Infectious, endocrine, and other workups are negative. After a consult to Psychiatry, the treating clinicians suspect that the most likely cause for rhabdomyolysis is aripiprazole.

Ms. A is treated with IV isotonic fluids. Aripiprazole is stopped and her CK levels are closely monitored. CK levels continue to trend down, and by Day 6 of hospitalization her CK level is 1,648 U/L. Her transaminase levels also improve; these elevations are considered likely secondary to rhabdomyolysis. Because there is notable improvement in CK and transaminase levels after stopping aripiprazole, Ms. A is discharged and instructed to follow up with a psychiatrist for further management.

Aripiprazole and rhabdomyolysis

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, an estimated 2.8% of the US population has bipolar disorder and 0.24% to 0.64% has schizophrenia.1,2 Antipsychotics are often used to treat these disorders. The prevalence of antipsychotic use in the general adult population is 1.6%.3 The use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) has increased over recent years with the availability of a variety of formulations, such as immediate-release injectable, long-acting injectable, and orally disintegrating tablets in addition to the customary oral tablets. SGAs can cause several adverse effects, including weight gain, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, QTc prolongation, extrapyramidal side effects, myocarditis, agranulocytosis, cataracts, and sexual adverse effects.4

Antipsychotic use is more commonly associated with serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome than it is with rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis as an adverse effect of antipsychotic use has not been well understood or reported. One study found the prevalence of rhabdomyolysis was approximately 10% among patients who received an antipsychotic medication.5 There have been 4 case reports of clozapine use, 6 of olanzapine use, and 3 of aripiprazole use associated with rhabdomyolysis.6-8 Therefore, this would be the fourth case report to describe aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis.

Aripiprazole is FDA-approved for the treatment of schizophrenia. In this case report, we found that aripiprazole could have led to rhabdomyolysis. Aripiprazole is a quinoline derivative that acts by binding to the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors.9,10 It acts as a partial agonist at 5-HT1A receptors, an antagonist at 5-HT2A receptors, and a partial agonist and stabilizer at the D2 receptor. By binding to the dopamine receptor in its G protein–coupled state, aripiprazole blocks the receptor in the presence of excessive dopamine.11-13 The mechanism of how aripiprazole could cause rhabdomyolysis is unclear. One proposed mechanism is that it can increase the permeability of skeletal muscle by 5-HT2A antagonism. This leads to a decrease in glucose reuptake in the cell and increases the permeability of the cell membrane, leading to elevations in CK levels.14 Another proposed mechanism is that dopamine blockade in the nigrostriatal pathway can result in muscle stiffness, rigidity, parkinsonian-like symptoms, and akathisia, which can result in elevated CK levels.15 There are only 3 other published cases of aripiprazole-induced rhabdomyolysis; we hope this case report will add value to the available literature. More evidence is needed to establish the safety profile of aripiprazole.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of bipolar disorder among adults. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/bipolar-disorder#part_2605

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia#part_2543

3. Dennis JA, Gittner LS, Payne JD, et al. Characteristics of U.S. adults taking prescription antipsychotic medications, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2018. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):483. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02895-4

4. Willner K, Vasan S, Abdijadid S. Atypical antipsychotic agents. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448156/

5. Packard K, Price P, Hanson A. Antipsychotic use and the risk of rhabdomyolysis. J Pharm Pract 2014;27(5):501-512. doi: 10.1177/0897190013516509

6. Wu YF, Chang KY. Aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis in a patient with schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(3):E51.

7. Marzetti E, Bocchino L, Teramo S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis in a patient on aripiprazole with traumatic hip prosthesis luxation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):E40-E41.

8. Zhu X, Hu J, Deng S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and elevated liver enzymes after rapid correction of hyponatremia due to pneumonia and concurrent use of aripiprazole: a case report. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52(2):206. doi:10.1177/0004867417743342

9. Stahl SM. Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Application. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2000.

10. Stahl SM. “Hit-and-run” actions at dopamine receptors, part 1: mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(9):670-671.

11. Leysen JE, Janssen PM, Schotte A, et al. Interaction of antipsychotic drugs with neurotransmitter receptor sites in vitro and in vivo in relation to pharmacological and clinical effects: role of 5HT2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1993;112(1 Suppl):S40-S54.

12. Millan MJ. Improving the treatment of schizophrenia: focus on serotonin (5-HT)(1A) receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295(3):853-861.

13. Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70(2):83-244.

14. Meltzer HY, Cola PA, Parsa M. Marked elevations of serum creatine kinase activity associated with antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15(4):395-405.

15. Devarajan S, Dursun SM. Antipsychotic drugs, serum creatine kinase (CPK) and possible mechanisms. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000;152(1):122.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of bipolar disorder among adults. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/bipolar-disorder#part_2605

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia#part_2543

3. Dennis JA, Gittner LS, Payne JD, et al. Characteristics of U.S. adults taking prescription antipsychotic medications, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2018. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):483. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02895-4

4. Willner K, Vasan S, Abdijadid S. Atypical antipsychotic agents. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448156/

5. Packard K, Price P, Hanson A. Antipsychotic use and the risk of rhabdomyolysis. J Pharm Pract 2014;27(5):501-512. doi: 10.1177/0897190013516509

6. Wu YF, Chang KY. Aripiprazole-associated rhabdomyolysis in a patient with schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(3):E51.

7. Marzetti E, Bocchino L, Teramo S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis in a patient on aripiprazole with traumatic hip prosthesis luxation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):E40-E41.

8. Zhu X, Hu J, Deng S, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and elevated liver enzymes after rapid correction of hyponatremia due to pneumonia and concurrent use of aripiprazole: a case report. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52(2):206. doi:10.1177/0004867417743342

9. Stahl SM. Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Application. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2000.

10. Stahl SM. “Hit-and-run” actions at dopamine receptors, part 1: mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(9):670-671.

11. Leysen JE, Janssen PM, Schotte A, et al. Interaction of antipsychotic drugs with neurotransmitter receptor sites in vitro and in vivo in relation to pharmacological and clinical effects: role of 5HT2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1993;112(1 Suppl):S40-S54.

12. Millan MJ. Improving the treatment of schizophrenia: focus on serotonin (5-HT)(1A) receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295(3):853-861.

13. Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70(2):83-244.

14. Meltzer HY, Cola PA, Parsa M. Marked elevations of serum creatine kinase activity associated with antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15(4):395-405.

15. Devarajan S, Dursun SM. Antipsychotic drugs, serum creatine kinase (CPK) and possible mechanisms. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000;152(1):122.

Subtle cognitive decline in a patient with depression and anxiety

CASE Anxious and confused

Mr. M, age 53, a surgeon, presents to the emergency department (ED) following a panic attack and concerns from his staff that he appears confused. Specifically, staff members report that in the past 4 months, Mr. M was observed having problems completing some postoperative tasks related to chart documentation. Mr. M has a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes.

HISTORY A long-standing diagnosis of depression

Mr. M reports that 30 years ago, he received care from a psychiatrist to address symptoms of MDD. He says that around the time he arrived at the ED, he had noticed subtle but gradual changes in his cognition, which led him to skip words and often struggle to find the correct words. These episodes left him confused. Mr. M started getting anxious about these cognitive issues because they disrupted his work and forced him to reduce his duties. He does not have any known family history of mental illness, is single, and lives alone.

EVALUATION After stroke is ruled out, a psychiatric workup

In the ED, a comprehensive exam rules out an acute cerebrovascular event. A neurologic evaluation notes some delay in processing information and observes Mr. M having difficulty following simple commands. Laboratory investigations, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, are unremarkable. An MRI of Mr. M’s brain, with and without contrast, notes no acute findings. He is discharged from the ED with a diagnosis of MDD.

Before he presented to the ED, Mr. M’s medication regimen included duloxetine 60 mg/d, buspirone 10 mg 3 times a day, and aripiprazole 5 mg/d for MDD and anxiety. After the ED visit, Mr. M’s physician refers him to an outpatient psychiatrist for management of worsening depression and panic attacks. During the psychiatrist’s evaluation, Mr. M reports a decreased interest in activities, decreased motivation, being easily fatigued, and having poor sleep. He denies having a depressed mood, difficulty concentrating, or having problems with his appetite. He also denies suicidal thoughts, both past and present.

Mr. M describes his mood as anxious, primarily surrounding his recent cognitive changes. He does not have a substance use disorder, psychotic illness, mania or hypomania, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. He reports adherence to his psychiatric medications. A mental status exam reveals Mr. M to be anxious. His attention is not well sustained, and he has difficulty describing details of his cognitive struggles, providing vague descriptions such as “skipping thought” and “skipping words.” Mr. M’s affect is congruent to his mood with some restriction and the psychiatrist notes that he is experiencing thought latency, poverty of content of thoughts, word-finding difficulties, and circumlocution. Mr. M denies any perceptual abnormalities, and there is no evidence of delusions.

[polldaddy:11320112]

The authors’ observations

Mr. M’s symptoms are significant for subacute cognitive decline that is subtle but gradual and can be easily missed, especially in the beginning. Though his ED evaluation—including brain imaging—ruled out acute or focal neurologic findings and his primary psychiatric presentation was anxiety, Mr. M’s medical history and mental status exam were suggestive of cognitive deficits.

Collateral information was obtained from his work colleagues, which confirmed both cognitive problems and comorbid anxiety. Additionally, given Mr. M’s high cognitive baseline as a surgeon, the new-onset cognitive changes over 4 months warranted further cognitive and neurologic evaluation. There are many causes of cognitive impairment (vascular, cancer, infection, autoimmune, medications, substances or toxins, neurodegenerative, psychiatric, vitamin deficiencies), all of which need to be considered in a patient with a nonspecific presentation such as Mr. M’s. The psychiatrist confirmed Mr. M’s current medication regimen, and discussed tapering aripiprazole while continuing duloxetine and buspirone.

Continue to: EVALUATION A closer look at cognitive deficits

EVALUATION A closer look at cognitive deficits

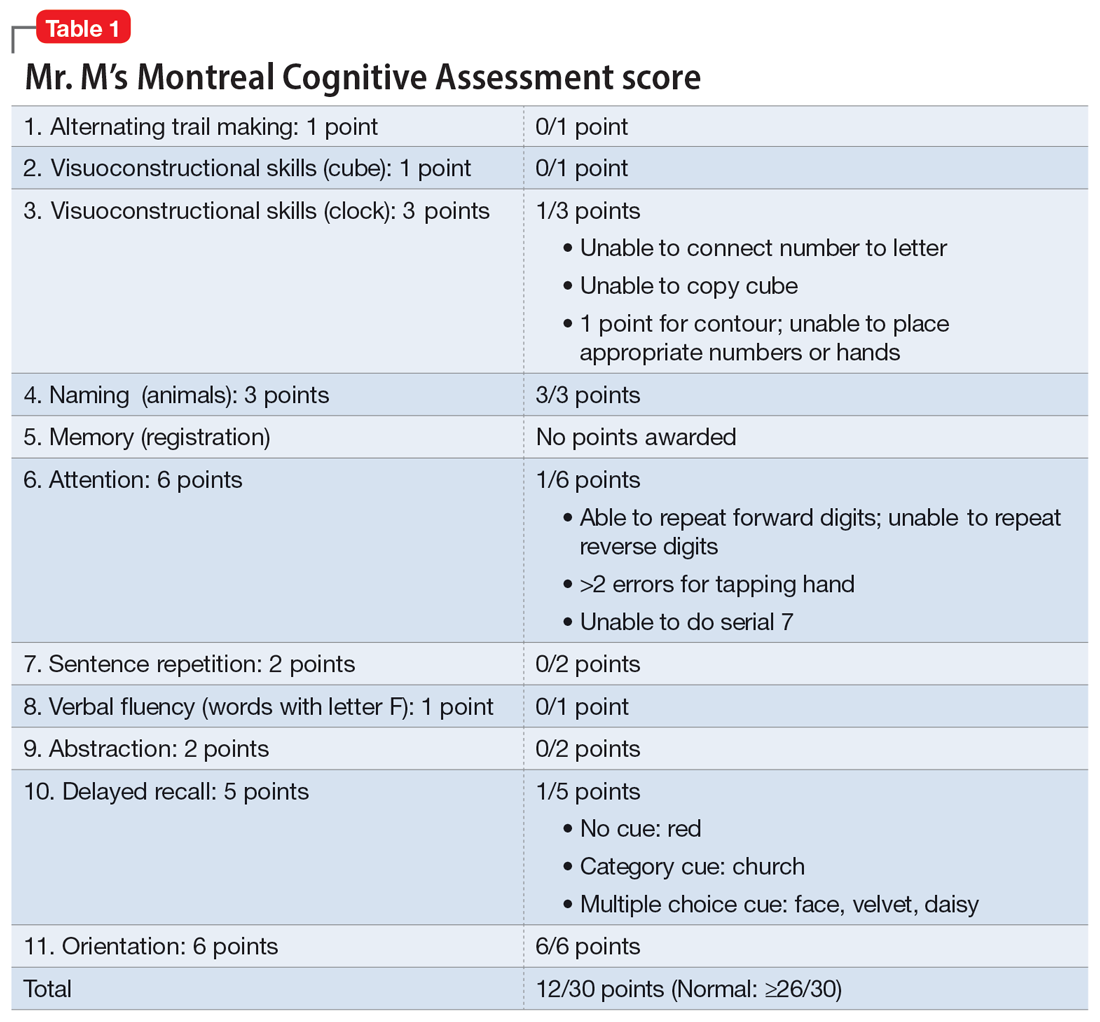

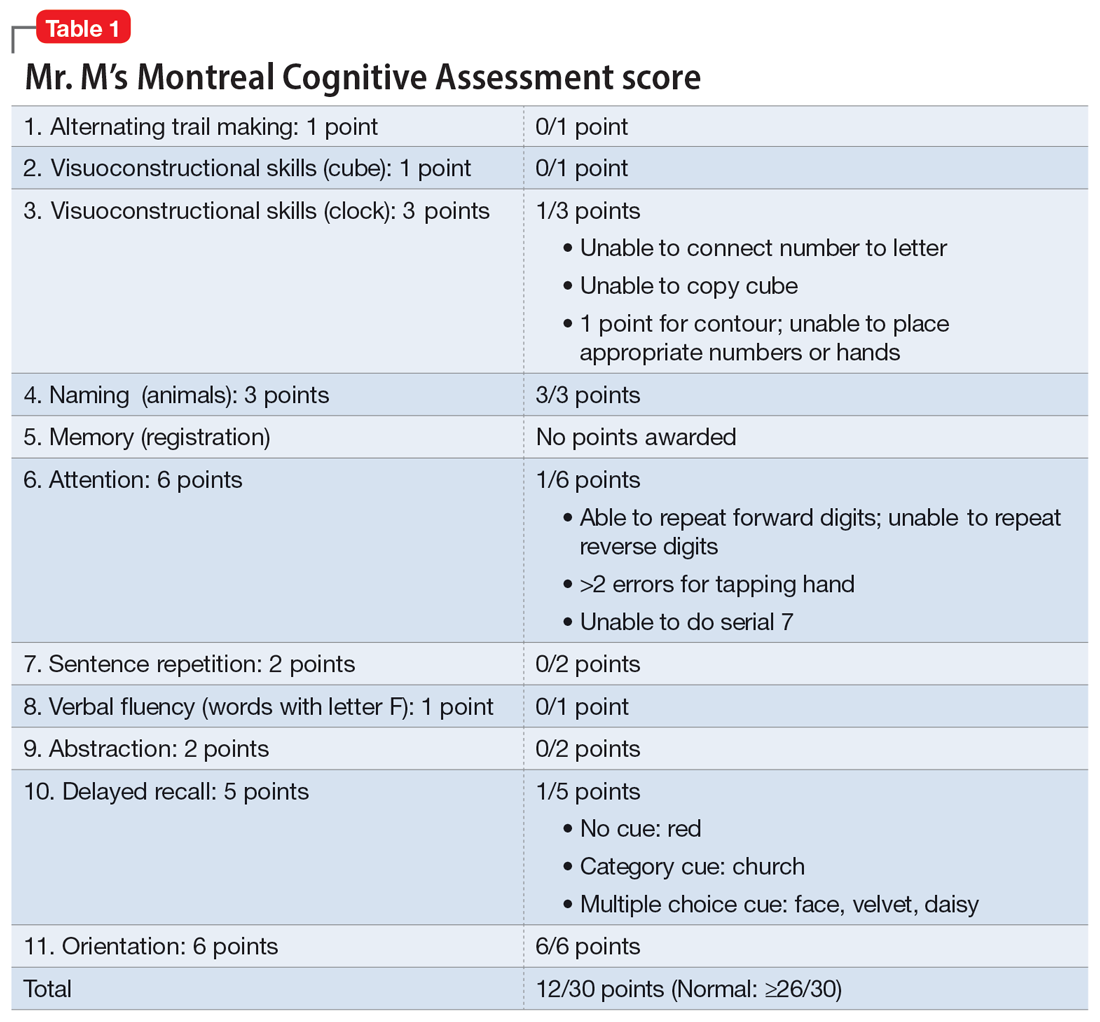

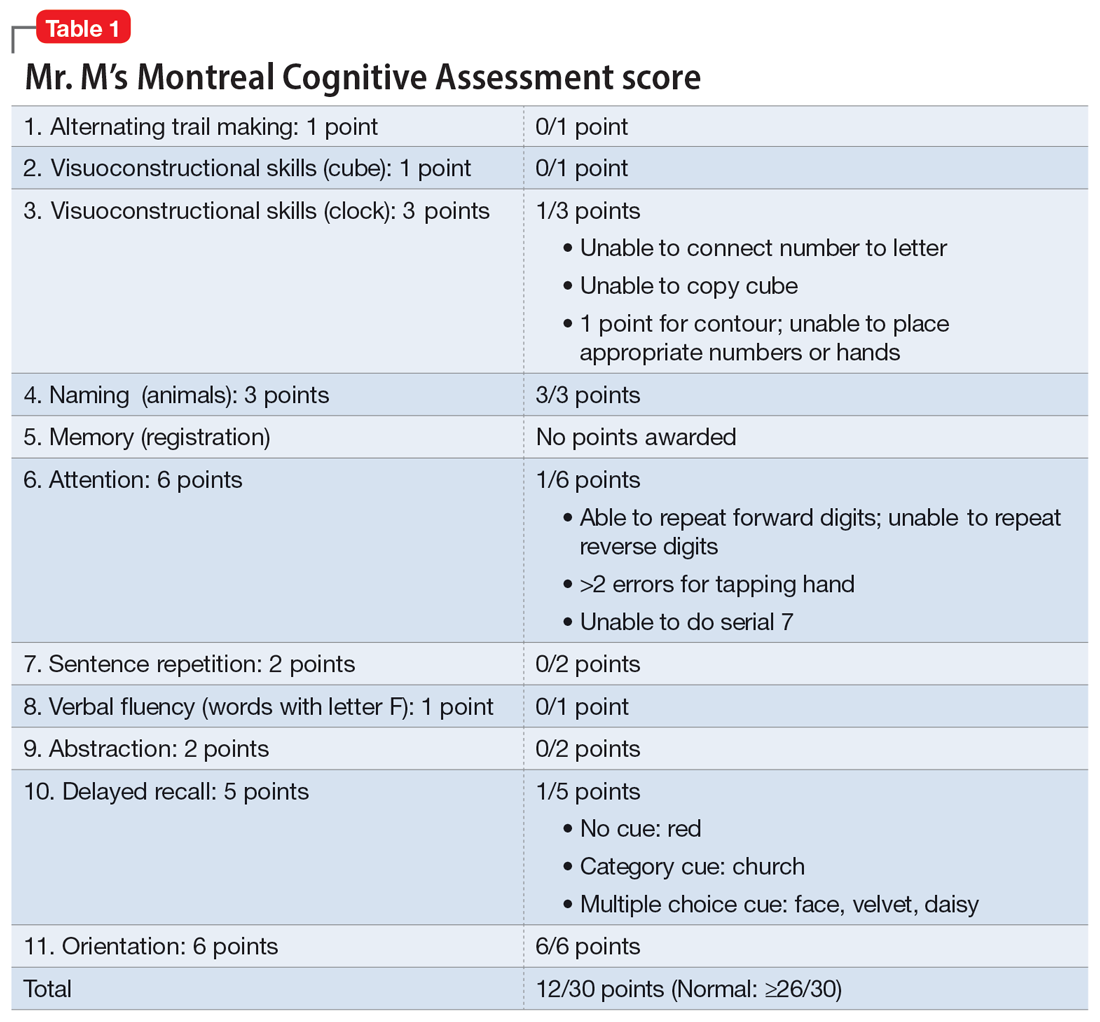

Mr. M scores 12/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicating moderate cognitive impairment (Table 1). The psychiatrist refers Mr. M to Neurology. During his neurologic evaluation, Mr. M continues to report feeling anxious that “something is wrong” and skips his words. The neurologist confirms Mr. M’s symptoms may have started 2 to 3 months before he presented to the ED. Mr. M reports unusual eating habits, including yogurt and cookies for breakfast, Mexican food for lunch, and more cookies for dinner. He denies having a fever, gaining or losing weight, rashes, headaches, neck stiffness, tingling or weakness or stiffness of limbs, vertigo, visual changes, photophobia, unsteady gait, bowel or bladder incontinence, or tremors.

When the neurologist repeats the MoCA, Mr. M again scores 12. The neurologist notes that Mr. M answers questions a little slowly and pauses for thoughts when unable to find an answer. Mr. M has difficulty following some simple commands, such as “touch a finger to your nose.” Other in-office neurologic physical exams (cranial nerves, involuntary movements or tremors, sensation, muscle strength, reflexes, cerebellar signs) are unremarkable except for mildly decreased vibration sense of his toes. The neurologist concludes that Mr. M’s presentation is suggestive of subacute to chronic bradyphrenia and orders additional evaluation, including neuropsychological testing.

[polldaddy:11320114]

The authors’ observations

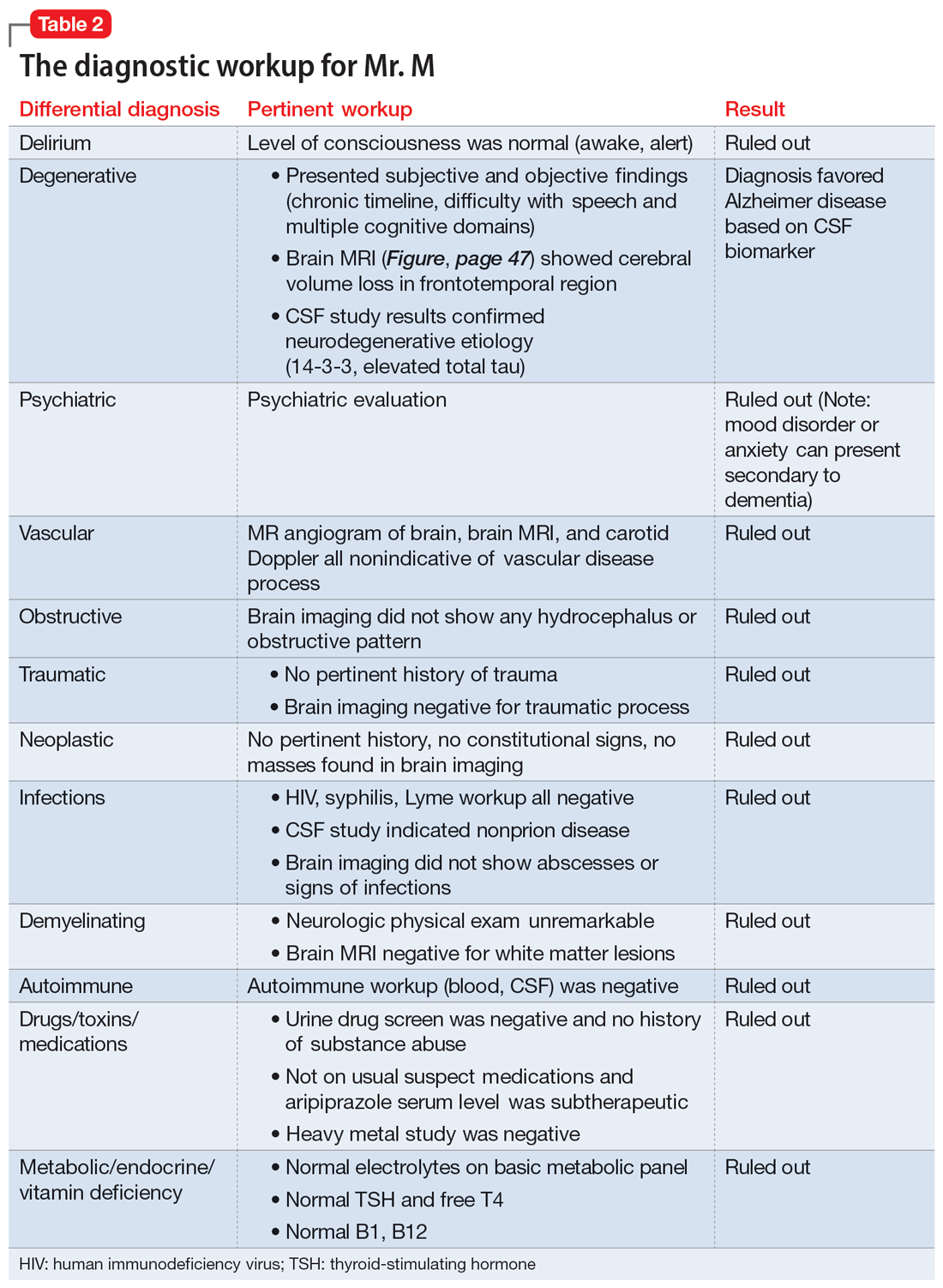

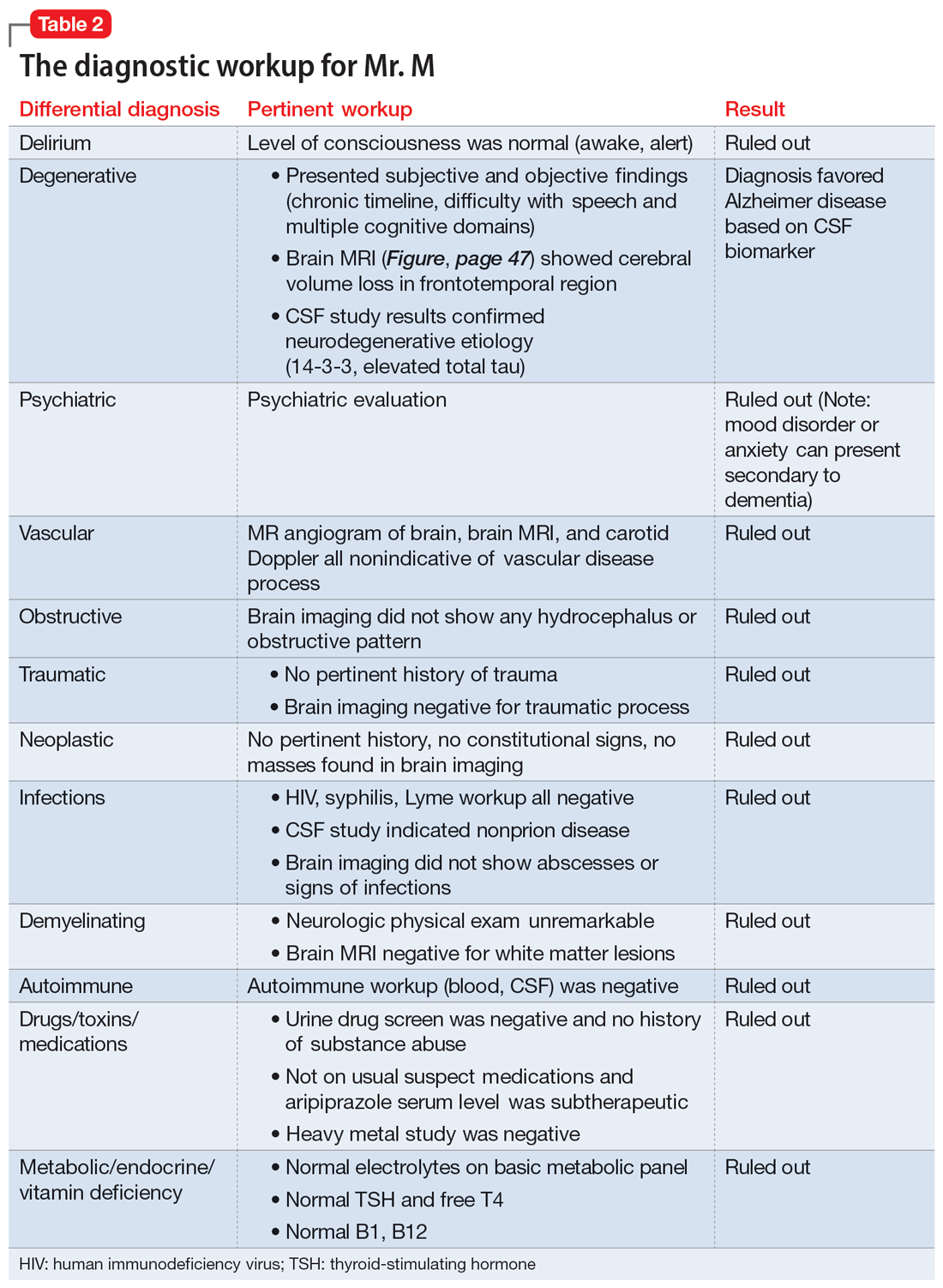

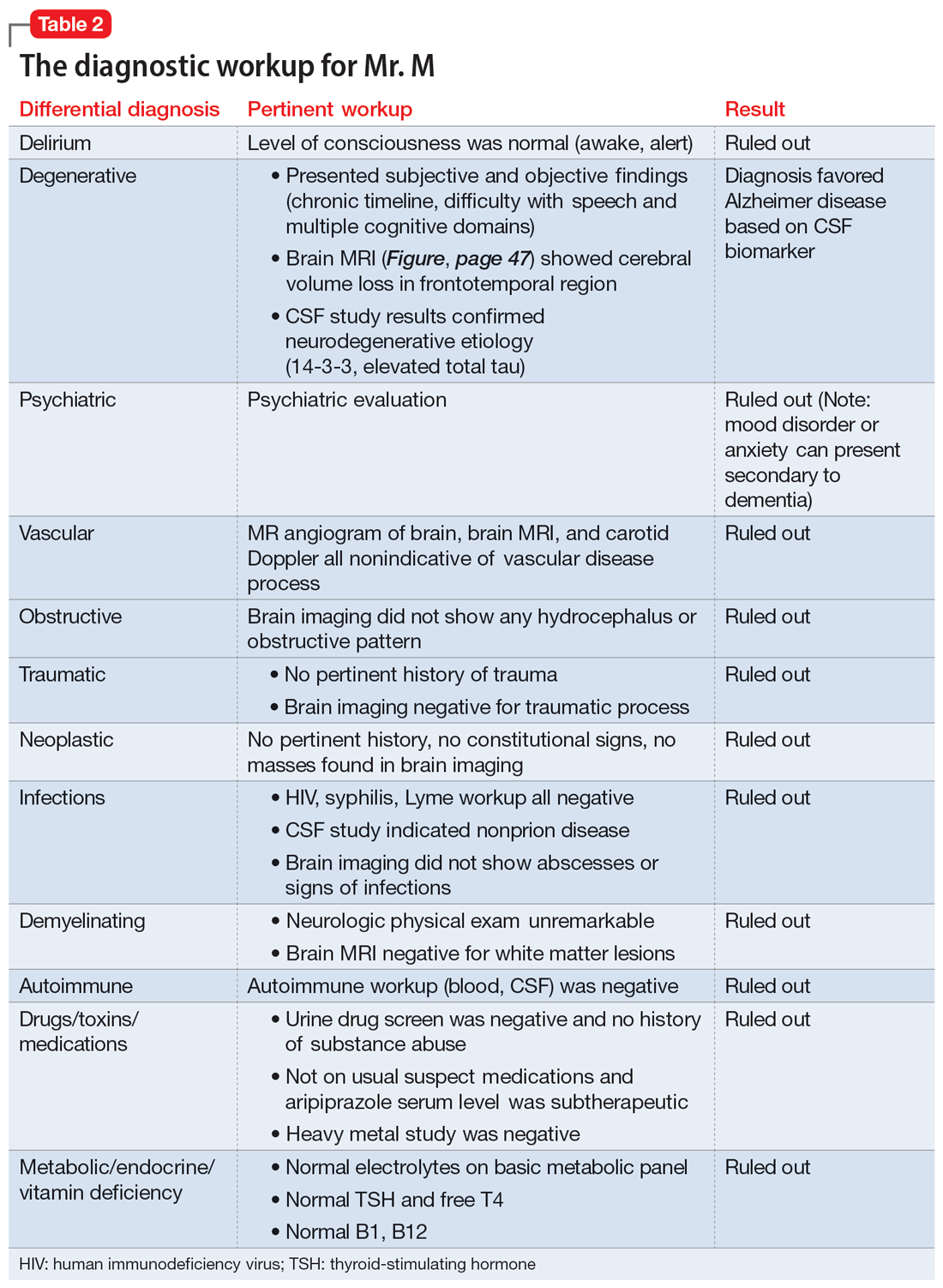

Physical and neurologic exams were not suggestive of any obvious causes of cognitive decline. Both the mental status exam and 2 serial MoCAs suggested deficits in executive function, language, and memory. Each of the differential diagnoses considered was ruled out with workup or exams (Table 2), which led to a most likely diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorder with PPA. Neuropsychological testing confirmed the diagnosis of nonfluent PPA.

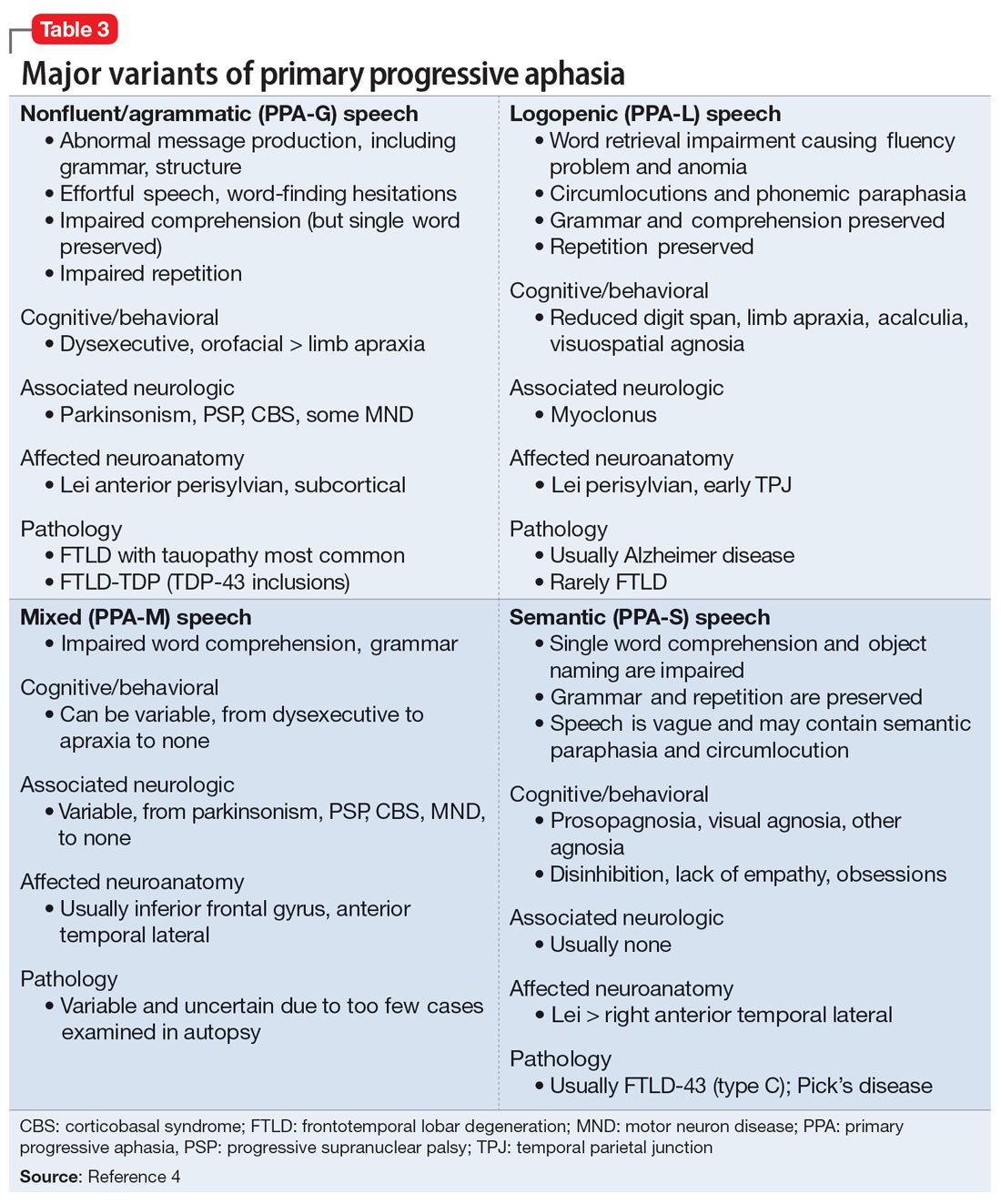

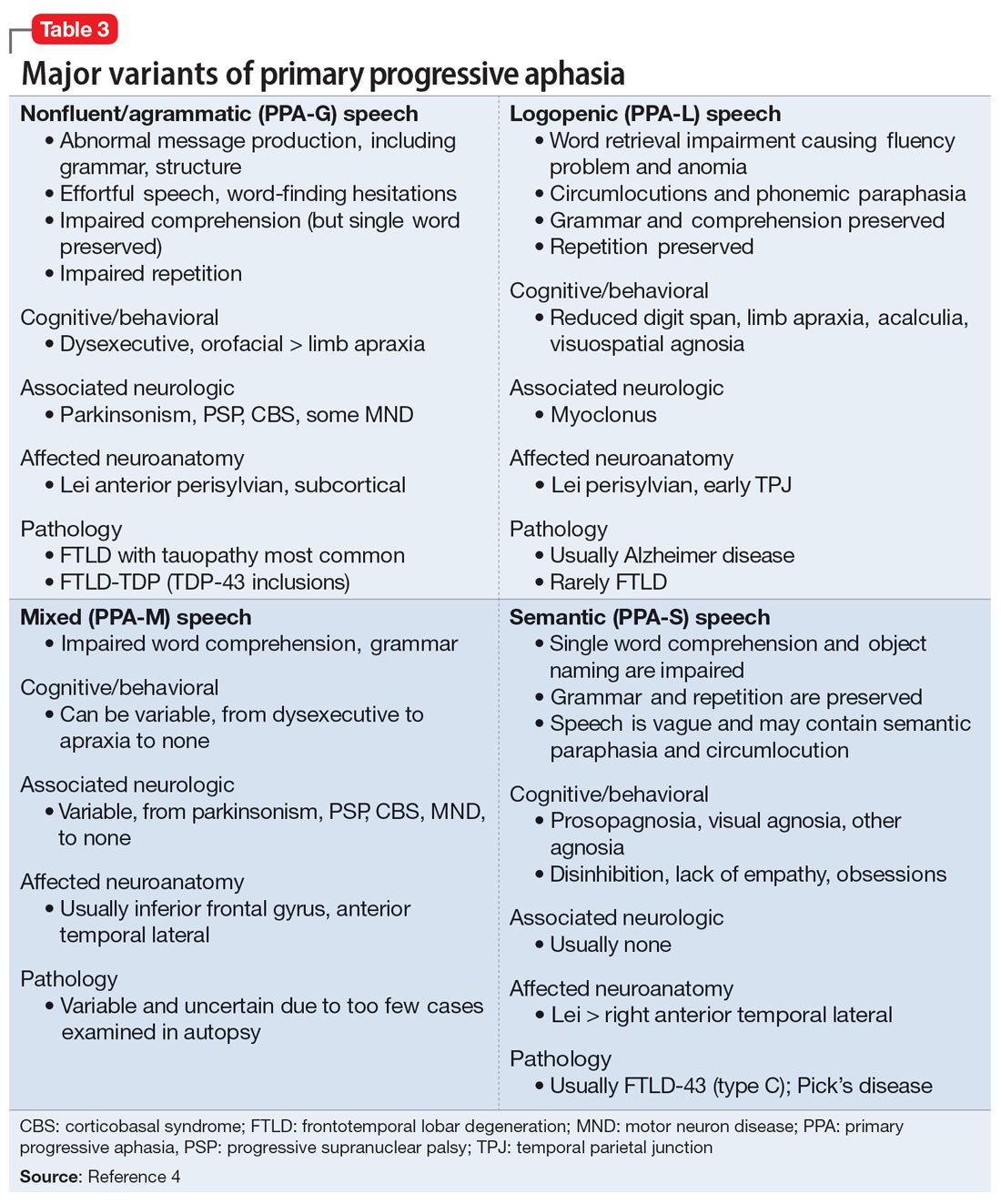

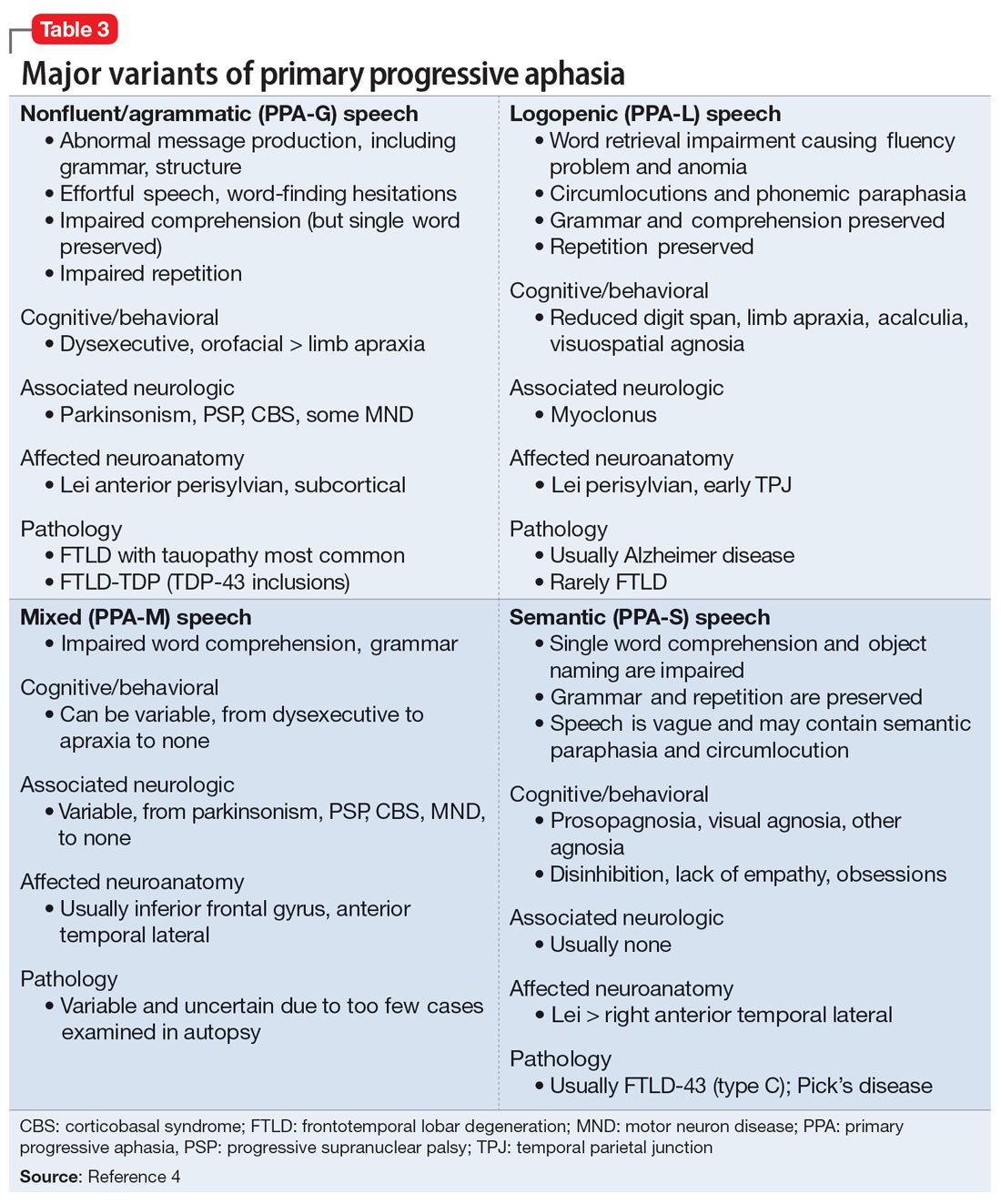

Primary progressive aphasia

PPA is an uncommon, heterogeneous group of disorders stemming from focal degeneration of language-governing centers of the brain.1,2 The estimated prevalence of PPA is 3 in 100,000 cases.2,3 There are 4 major variants of PPA (Table 34), and each presents with distinct language, cognitive, neuroanatomical, and neuropathological characteristics.4 PPA is usually diagnosed in late middle life; however, diagnosis is often delayed due to the relative obscurity of the disorder.4 In Mr. M’s case, it took approximately 4 months of evaluations by various specialists before a diagnosis was confirmed.

The initial phase of PPA can present as a diagnostic challenge because patients can have difficulty articulating their cognitive and language deficits. PPA can be commonly mistaken for a primary psychiatric disorder such as MDD or anxiety, which can further delay an accurate diagnosis and treatment. Special attention to the mental status exam, close observation of the patient’s language, and assessment of cognitive abilities using standardized screenings such as the MoCA or Mini-Mental State Examination can be helpful in clarifying the diagnosis. It is also important to rule out developmental problems (eg, dyslexia) and hearing difficulties, particularly in older patients.

Continue to: TREATMENT Adjusting the medication regimen

TREATMENT Adjusting the medication regimen

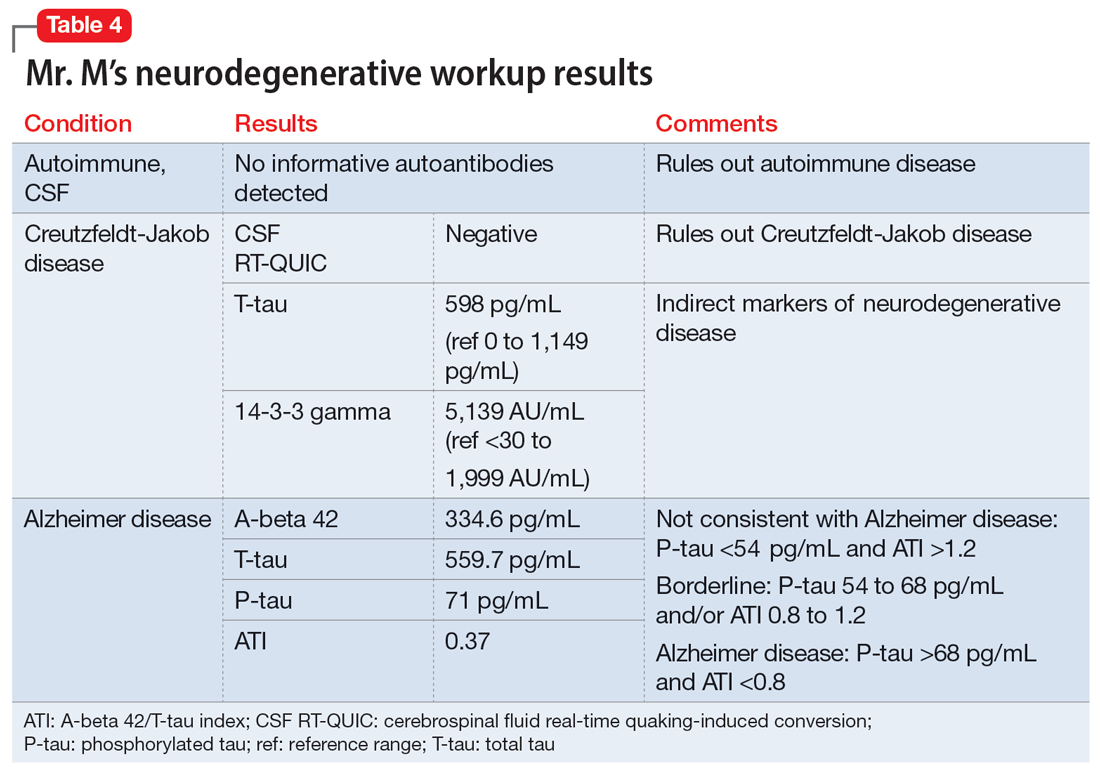

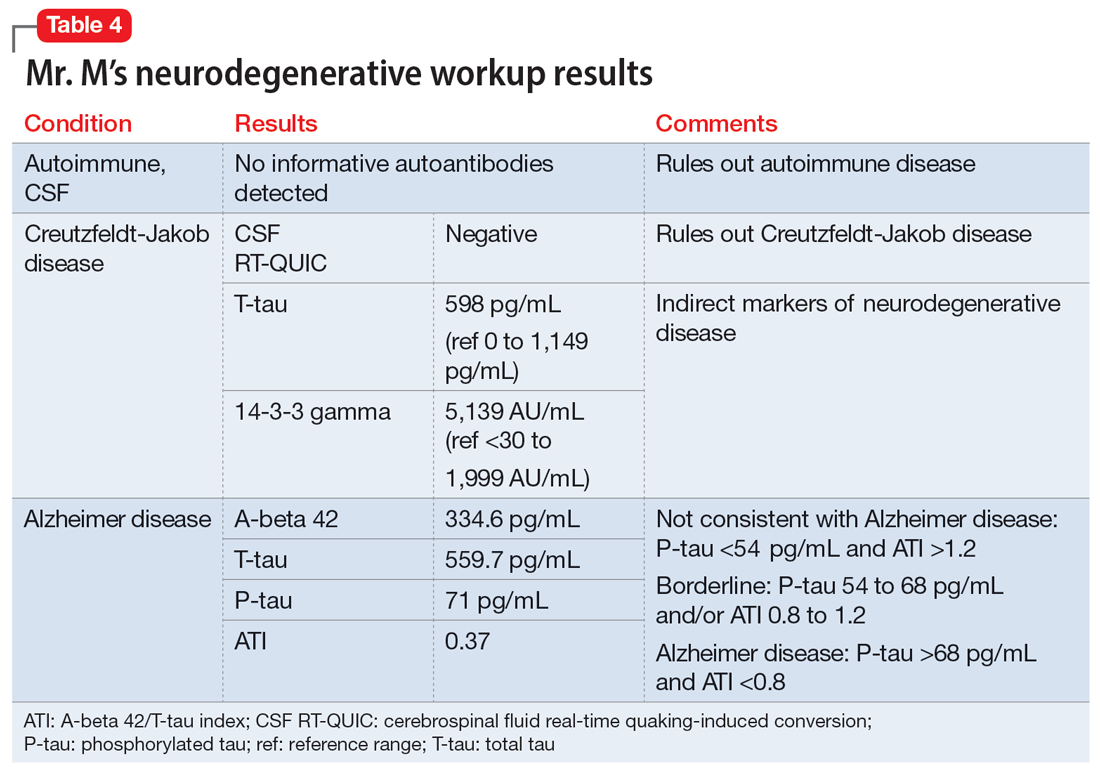

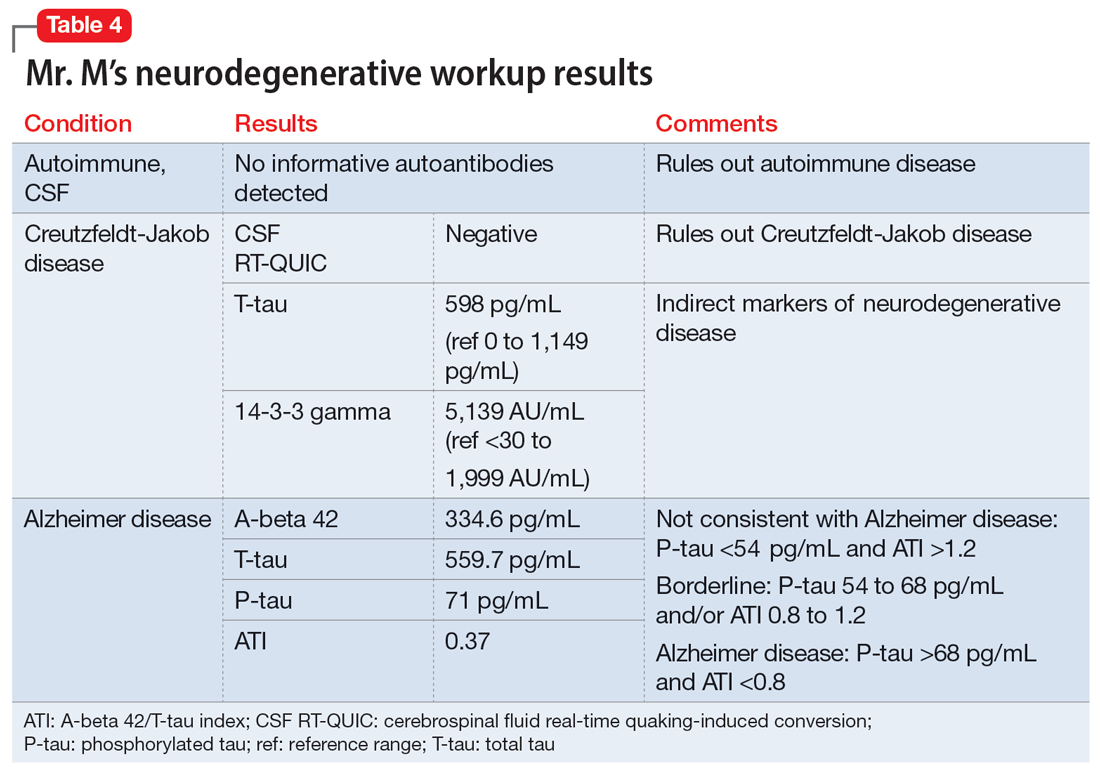

The neurologist completes additional examinations to rule out causes of rare neurodegenerative disorders, including CSF autoimmune disorders, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and Alzheimer disease (AD) (Table 4). Mr. M continues to follow up with his outpatient psychiatrist and his medication regimen is adjusted. Aripiprazole and buspirone are discontinued, and duloxetine is titrated to 60 mg twice a day. During follow-up visits, Mr. M discusses his understanding of his neurologic condition. His concerns shift to his illness and prognosis. During these visits, he continues to deny suicidality.

[polldaddy:11320115]

The authors’ observations

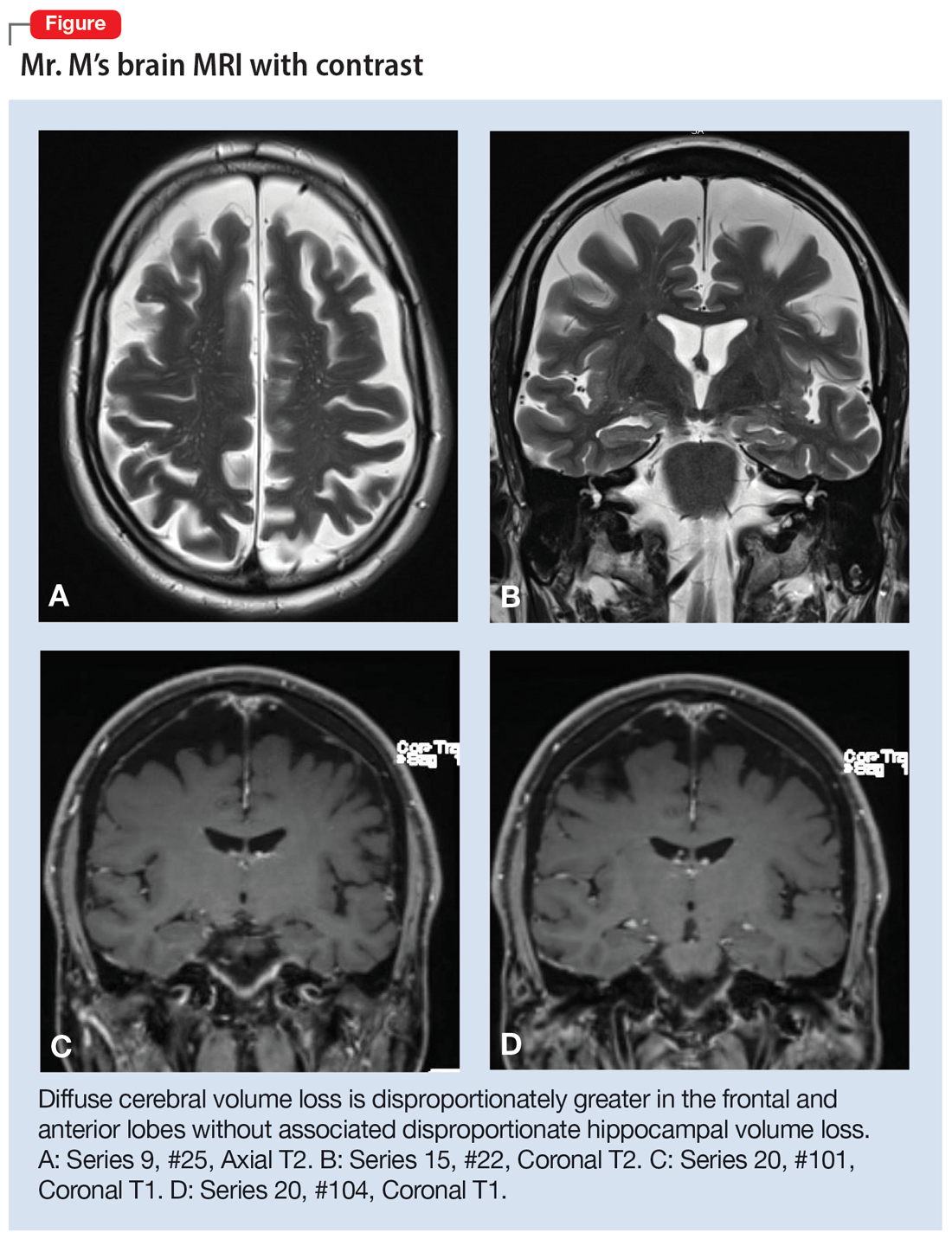

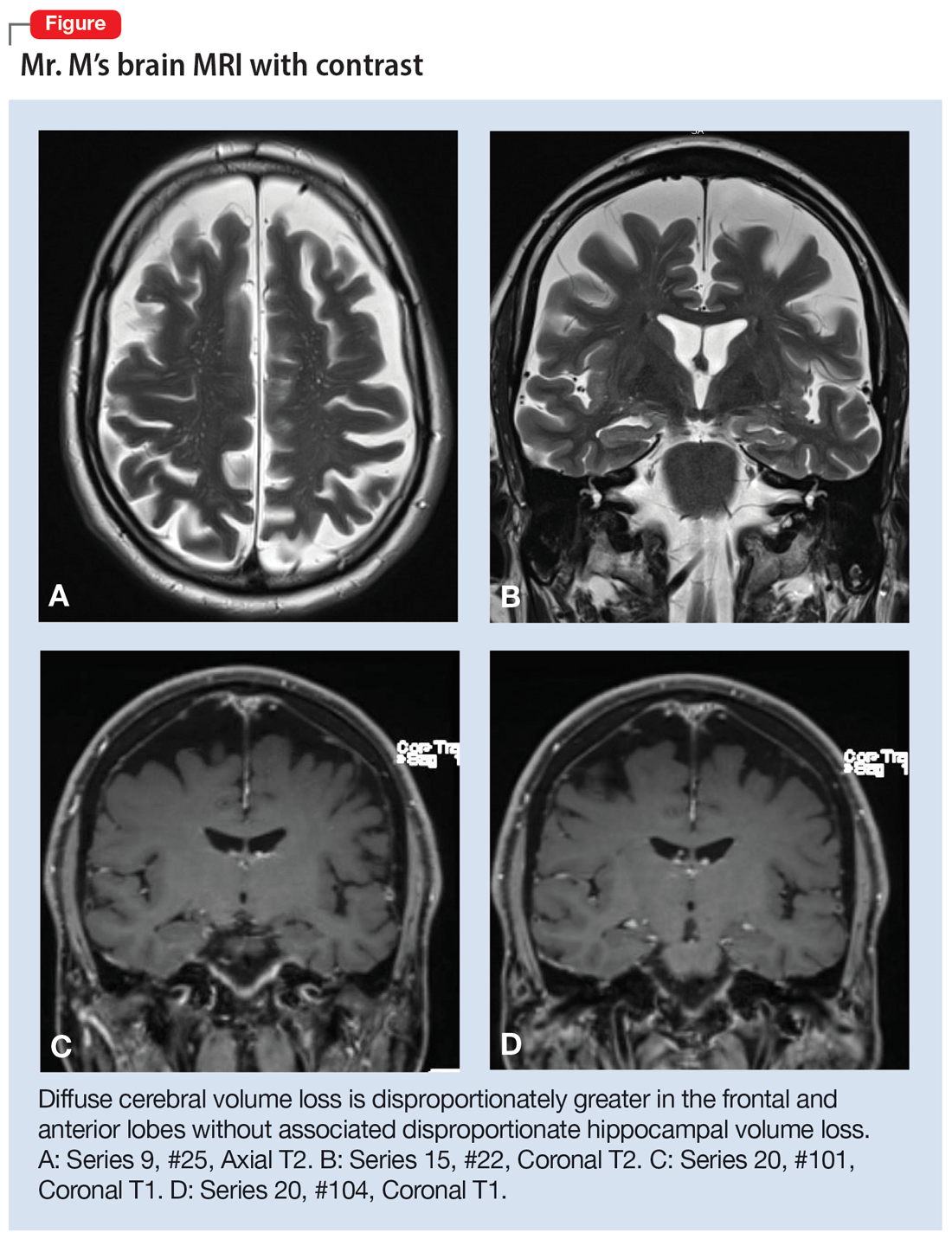

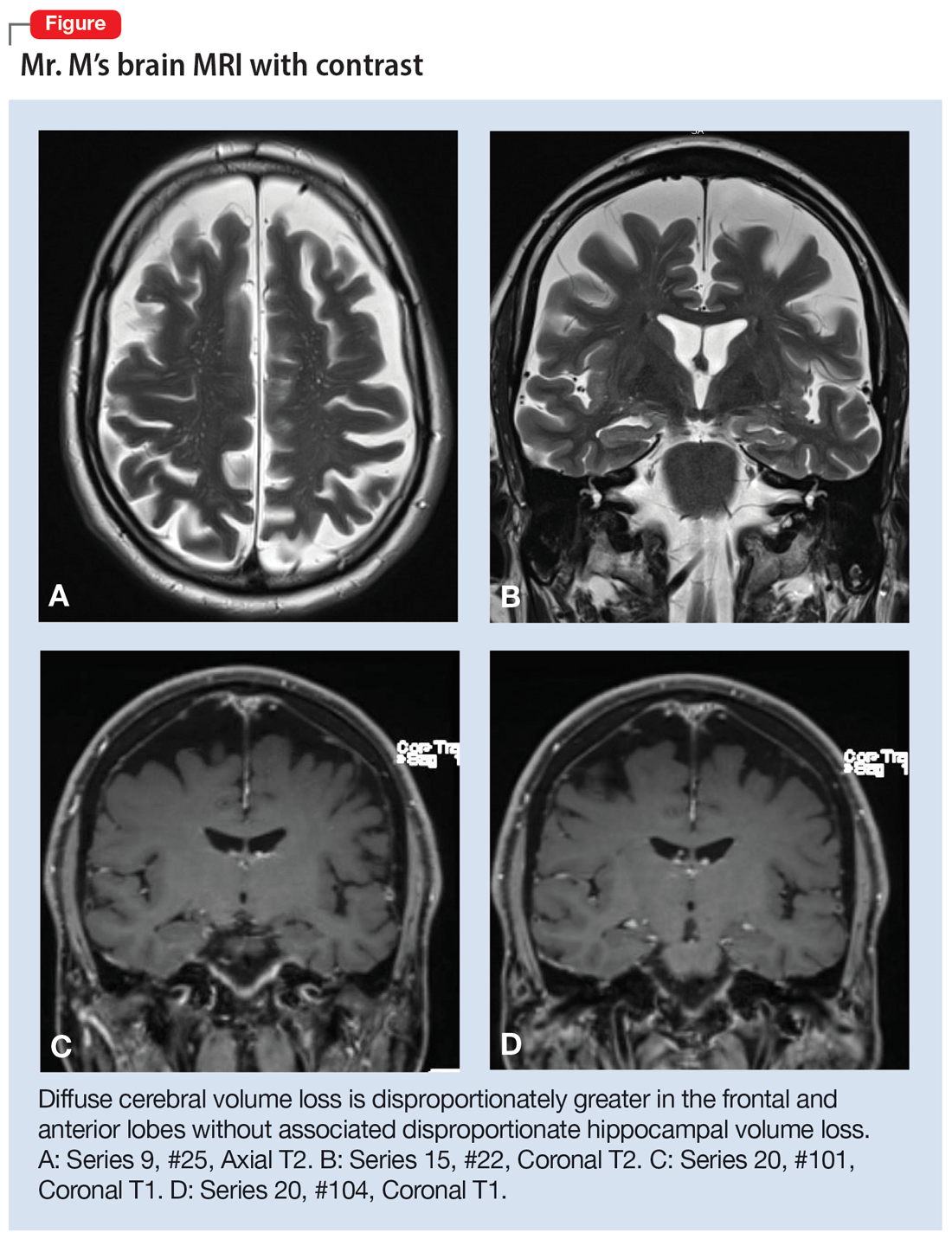

Mr. M’s neurodegenerative workup identified an intriguing diagnostic challenge. A repeat brain MRI (Figure) showed atrophy patterns suggestive of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). On the other hand, his CSF ATI (A-beta 42/T-tau index, a value used to aid in the diagnosis of AD) was <1, suggesting early-onset AD.5,6 Although significant advances have been made to distinguish AD and FTLD following an autopsy, there are still no reliable or definitive biomarkers to distinguish AD from FTLD (particularly in the early stages of FTLD). This can often leave the confirmatory diagnosis as a question.7

A PPA diagnosis (and other dementias) can have a significant impact on the patient and their family due to the uncertain nature of the progression of the disease and quality-of-life issues related to language and other cognitive deficits. Early identification and accurate diagnosis of PPA and its etiology (ie, AD vs FTLD) is important to avoid unnecessary exposure to medications or the use of polypharmacy to treat an inaccurate diagnosis of a primary psychiatric illness. For example, Mr. M was being treated with 3 psychiatric medications (aripiprazole, buspirone, and duloxetine) for depression and anxiety prior to the diagnosis of PPA.

Nonpharmacologic interventions can play an important role in the management of patients with PPA. These include educating the patient and their family about the diagnosis and discussions about future planning, including appropriate social support, employment, and finances.4 Pharmacologic interventions may be limited, as there are currently no disease-modifying treatments for PPA or FTLD. For patients with nonfluent PPA or AD, cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil or N-methyl

Psychiatrists should continue to treat patients with PPA for comorbid anxiety or depression, with appropriate medications and/or supportive therapy to guide the patient through the process of grief. Assessing for suicide risk is also important in patients diagnosed with dementia. A retrospective cohort study of patients age ≥60 with a diagnosis of dementia suggested that the majority of suicides occurred in those with a new dementia diagnosis.9 End-of-life decisions such as advanced directives should be made when the patient still has legal capacity, ideally as soon as possible after diagnosis.10

OUTCOME Remaining engaged in treatment

Mr. M continues to follow-up with the Neurology team. He has also been regularly seeing his psychiatric team for medication management and supportive therapy, and his psychiatric medications have been optimized to reduce polypharmacy. During his sessions, Mr. M discusses his grief and plans for the future. Despite his anxiety about the uncertainty of his prognosis, Mr. M continues to report that he is doing reasonably well and remains engaged in treatment.

Bottom Line

Patients with primary progressive aphasia and rare neurodegenerative disorders may present to an outpatient or emergency setting with symptoms of anxiety and confusion. They are frequently misdiagnosed with a primary psychiatric disorder due to the nature of cognitive and language deficits, particularly in the early stages of the disease. Paying close attention to language and conducting cognitive screening are critical in identifying the true cause of a patient’s symptoms.

Related Resources

- Primary progressive aphasia. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/8541/primary-progressive-aphasia

- Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: A useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Donepezil • Aricept

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Memantine • Namenda

1. Grossman M. Primary progressive aphasia: clinicopathological correlations. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(2):88-97. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.216

2. Mesulam M-M, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, et al. Primary progressive aphasia and the evolving neurology of the language network. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(10):554-569. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.159

3. Coyle-Gilchrist ITS, Dick KM, Patterson K, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. Neurology. 2016;86(18):1736-1743. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002638

4. Marshall CR, Hardy CJD, Volkmer A, et al. Primary progressive aphasia: a clinical approach. J Neurol. 2018;265(6):1474-1490. doi:10.1007/s00415-018-8762-6

5. Blennow K. Cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroRx. 2004;1(2):213-225. doi:10.1602/neurorx.1.2.213

6. Hulstaert F, Blennow K, Ivanoiu A, et al. Improved discrimination of AD patients using beta-amyloid(1-42) and tau levels in CSF. Neurology. 1999;52(8):1555-1562. doi:10.1212/wnl.52.8.1555

7. Thijssen EH, La Joie R, Wolf A, et al. Diagnostic value of plasma phosphorylated tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):387-397. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0762-2

8. Newhart M, Davis C, Kannan V, et al. Therapy for naming deficits in two variants of primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology. 2009;23(7-8):823-834. doi:10.1080/02687030802661762

9. Seyfried LS, Kales HC, Ignacio RV, et al. Predictors of suicide in patients with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(6):567-573. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.01.006

10. Porteri C. Advance directives as a tool to respect patients’ values and preferences: discussion on the case of Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19(1):9. doi:10.1186/s12910-018-0249-6

CASE Anxious and confused

Mr. M, age 53, a surgeon, presents to the emergency department (ED) following a panic attack and concerns from his staff that he appears confused. Specifically, staff members report that in the past 4 months, Mr. M was observed having problems completing some postoperative tasks related to chart documentation. Mr. M has a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes.

HISTORY A long-standing diagnosis of depression

Mr. M reports that 30 years ago, he received care from a psychiatrist to address symptoms of MDD. He says that around the time he arrived at the ED, he had noticed subtle but gradual changes in his cognition, which led him to skip words and often struggle to find the correct words. These episodes left him confused. Mr. M started getting anxious about these cognitive issues because they disrupted his work and forced him to reduce his duties. He does not have any known family history of mental illness, is single, and lives alone.

EVALUATION After stroke is ruled out, a psychiatric workup

In the ED, a comprehensive exam rules out an acute cerebrovascular event. A neurologic evaluation notes some delay in processing information and observes Mr. M having difficulty following simple commands. Laboratory investigations, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, are unremarkable. An MRI of Mr. M’s brain, with and without contrast, notes no acute findings. He is discharged from the ED with a diagnosis of MDD.

Before he presented to the ED, Mr. M’s medication regimen included duloxetine 60 mg/d, buspirone 10 mg 3 times a day, and aripiprazole 5 mg/d for MDD and anxiety. After the ED visit, Mr. M’s physician refers him to an outpatient psychiatrist for management of worsening depression and panic attacks. During the psychiatrist’s evaluation, Mr. M reports a decreased interest in activities, decreased motivation, being easily fatigued, and having poor sleep. He denies having a depressed mood, difficulty concentrating, or having problems with his appetite. He also denies suicidal thoughts, both past and present.

Mr. M describes his mood as anxious, primarily surrounding his recent cognitive changes. He does not have a substance use disorder, psychotic illness, mania or hypomania, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. He reports adherence to his psychiatric medications. A mental status exam reveals Mr. M to be anxious. His attention is not well sustained, and he has difficulty describing details of his cognitive struggles, providing vague descriptions such as “skipping thought” and “skipping words.” Mr. M’s affect is congruent to his mood with some restriction and the psychiatrist notes that he is experiencing thought latency, poverty of content of thoughts, word-finding difficulties, and circumlocution. Mr. M denies any perceptual abnormalities, and there is no evidence of delusions.

[polldaddy:11320112]

The authors’ observations

Mr. M’s symptoms are significant for subacute cognitive decline that is subtle but gradual and can be easily missed, especially in the beginning. Though his ED evaluation—including brain imaging—ruled out acute or focal neurologic findings and his primary psychiatric presentation was anxiety, Mr. M’s medical history and mental status exam were suggestive of cognitive deficits.

Collateral information was obtained from his work colleagues, which confirmed both cognitive problems and comorbid anxiety. Additionally, given Mr. M’s high cognitive baseline as a surgeon, the new-onset cognitive changes over 4 months warranted further cognitive and neurologic evaluation. There are many causes of cognitive impairment (vascular, cancer, infection, autoimmune, medications, substances or toxins, neurodegenerative, psychiatric, vitamin deficiencies), all of which need to be considered in a patient with a nonspecific presentation such as Mr. M’s. The psychiatrist confirmed Mr. M’s current medication regimen, and discussed tapering aripiprazole while continuing duloxetine and buspirone.

Continue to: EVALUATION A closer look at cognitive deficits

EVALUATION A closer look at cognitive deficits

Mr. M scores 12/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicating moderate cognitive impairment (Table 1). The psychiatrist refers Mr. M to Neurology. During his neurologic evaluation, Mr. M continues to report feeling anxious that “something is wrong” and skips his words. The neurologist confirms Mr. M’s symptoms may have started 2 to 3 months before he presented to the ED. Mr. M reports unusual eating habits, including yogurt and cookies for breakfast, Mexican food for lunch, and more cookies for dinner. He denies having a fever, gaining or losing weight, rashes, headaches, neck stiffness, tingling or weakness or stiffness of limbs, vertigo, visual changes, photophobia, unsteady gait, bowel or bladder incontinence, or tremors.

When the neurologist repeats the MoCA, Mr. M again scores 12. The neurologist notes that Mr. M answers questions a little slowly and pauses for thoughts when unable to find an answer. Mr. M has difficulty following some simple commands, such as “touch a finger to your nose.” Other in-office neurologic physical exams (cranial nerves, involuntary movements or tremors, sensation, muscle strength, reflexes, cerebellar signs) are unremarkable except for mildly decreased vibration sense of his toes. The neurologist concludes that Mr. M’s presentation is suggestive of subacute to chronic bradyphrenia and orders additional evaluation, including neuropsychological testing.

[polldaddy:11320114]

The authors’ observations

Physical and neurologic exams were not suggestive of any obvious causes of cognitive decline. Both the mental status exam and 2 serial MoCAs suggested deficits in executive function, language, and memory. Each of the differential diagnoses considered was ruled out with workup or exams (Table 2), which led to a most likely diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorder with PPA. Neuropsychological testing confirmed the diagnosis of nonfluent PPA.

Primary progressive aphasia

PPA is an uncommon, heterogeneous group of disorders stemming from focal degeneration of language-governing centers of the brain.1,2 The estimated prevalence of PPA is 3 in 100,000 cases.2,3 There are 4 major variants of PPA (Table 34), and each presents with distinct language, cognitive, neuroanatomical, and neuropathological characteristics.4 PPA is usually diagnosed in late middle life; however, diagnosis is often delayed due to the relative obscurity of the disorder.4 In Mr. M’s case, it took approximately 4 months of evaluations by various specialists before a diagnosis was confirmed.

The initial phase of PPA can present as a diagnostic challenge because patients can have difficulty articulating their cognitive and language deficits. PPA can be commonly mistaken for a primary psychiatric disorder such as MDD or anxiety, which can further delay an accurate diagnosis and treatment. Special attention to the mental status exam, close observation of the patient’s language, and assessment of cognitive abilities using standardized screenings such as the MoCA or Mini-Mental State Examination can be helpful in clarifying the diagnosis. It is also important to rule out developmental problems (eg, dyslexia) and hearing difficulties, particularly in older patients.

Continue to: TREATMENT Adjusting the medication regimen

TREATMENT Adjusting the medication regimen

The neurologist completes additional examinations to rule out causes of rare neurodegenerative disorders, including CSF autoimmune disorders, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and Alzheimer disease (AD) (Table 4). Mr. M continues to follow up with his outpatient psychiatrist and his medication regimen is adjusted. Aripiprazole and buspirone are discontinued, and duloxetine is titrated to 60 mg twice a day. During follow-up visits, Mr. M discusses his understanding of his neurologic condition. His concerns shift to his illness and prognosis. During these visits, he continues to deny suicidality.

[polldaddy:11320115]

The authors’ observations

Mr. M’s neurodegenerative workup identified an intriguing diagnostic challenge. A repeat brain MRI (Figure) showed atrophy patterns suggestive of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). On the other hand, his CSF ATI (A-beta 42/T-tau index, a value used to aid in the diagnosis of AD) was <1, suggesting early-onset AD.5,6 Although significant advances have been made to distinguish AD and FTLD following an autopsy, there are still no reliable or definitive biomarkers to distinguish AD from FTLD (particularly in the early stages of FTLD). This can often leave the confirmatory diagnosis as a question.7

A PPA diagnosis (and other dementias) can have a significant impact on the patient and their family due to the uncertain nature of the progression of the disease and quality-of-life issues related to language and other cognitive deficits. Early identification and accurate diagnosis of PPA and its etiology (ie, AD vs FTLD) is important to avoid unnecessary exposure to medications or the use of polypharmacy to treat an inaccurate diagnosis of a primary psychiatric illness. For example, Mr. M was being treated with 3 psychiatric medications (aripiprazole, buspirone, and duloxetine) for depression and anxiety prior to the diagnosis of PPA.

Nonpharmacologic interventions can play an important role in the management of patients with PPA. These include educating the patient and their family about the diagnosis and discussions about future planning, including appropriate social support, employment, and finances.4 Pharmacologic interventions may be limited, as there are currently no disease-modifying treatments for PPA or FTLD. For patients with nonfluent PPA or AD, cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil or N-methyl

Psychiatrists should continue to treat patients with PPA for comorbid anxiety or depression, with appropriate medications and/or supportive therapy to guide the patient through the process of grief. Assessing for suicide risk is also important in patients diagnosed with dementia. A retrospective cohort study of patients age ≥60 with a diagnosis of dementia suggested that the majority of suicides occurred in those with a new dementia diagnosis.9 End-of-life decisions such as advanced directives should be made when the patient still has legal capacity, ideally as soon as possible after diagnosis.10

OUTCOME Remaining engaged in treatment

Mr. M continues to follow-up with the Neurology team. He has also been regularly seeing his psychiatric team for medication management and supportive therapy, and his psychiatric medications have been optimized to reduce polypharmacy. During his sessions, Mr. M discusses his grief and plans for the future. Despite his anxiety about the uncertainty of his prognosis, Mr. M continues to report that he is doing reasonably well and remains engaged in treatment.

Bottom Line

Patients with primary progressive aphasia and rare neurodegenerative disorders may present to an outpatient or emergency setting with symptoms of anxiety and confusion. They are frequently misdiagnosed with a primary psychiatric disorder due to the nature of cognitive and language deficits, particularly in the early stages of the disease. Paying close attention to language and conducting cognitive screening are critical in identifying the true cause of a patient’s symptoms.

Related Resources

- Primary progressive aphasia. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/8541/primary-progressive-aphasia

- Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: A useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Donepezil • Aricept

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Memantine • Namenda

CASE Anxious and confused

Mr. M, age 53, a surgeon, presents to the emergency department (ED) following a panic attack and concerns from his staff that he appears confused. Specifically, staff members report that in the past 4 months, Mr. M was observed having problems completing some postoperative tasks related to chart documentation. Mr. M has a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes.

HISTORY A long-standing diagnosis of depression

Mr. M reports that 30 years ago, he received care from a psychiatrist to address symptoms of MDD. He says that around the time he arrived at the ED, he had noticed subtle but gradual changes in his cognition, which led him to skip words and often struggle to find the correct words. These episodes left him confused. Mr. M started getting anxious about these cognitive issues because they disrupted his work and forced him to reduce his duties. He does not have any known family history of mental illness, is single, and lives alone.

EVALUATION After stroke is ruled out, a psychiatric workup

In the ED, a comprehensive exam rules out an acute cerebrovascular event. A neurologic evaluation notes some delay in processing information and observes Mr. M having difficulty following simple commands. Laboratory investigations, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, are unremarkable. An MRI of Mr. M’s brain, with and without contrast, notes no acute findings. He is discharged from the ED with a diagnosis of MDD.

Before he presented to the ED, Mr. M’s medication regimen included duloxetine 60 mg/d, buspirone 10 mg 3 times a day, and aripiprazole 5 mg/d for MDD and anxiety. After the ED visit, Mr. M’s physician refers him to an outpatient psychiatrist for management of worsening depression and panic attacks. During the psychiatrist’s evaluation, Mr. M reports a decreased interest in activities, decreased motivation, being easily fatigued, and having poor sleep. He denies having a depressed mood, difficulty concentrating, or having problems with his appetite. He also denies suicidal thoughts, both past and present.

Mr. M describes his mood as anxious, primarily surrounding his recent cognitive changes. He does not have a substance use disorder, psychotic illness, mania or hypomania, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. He reports adherence to his psychiatric medications. A mental status exam reveals Mr. M to be anxious. His attention is not well sustained, and he has difficulty describing details of his cognitive struggles, providing vague descriptions such as “skipping thought” and “skipping words.” Mr. M’s affect is congruent to his mood with some restriction and the psychiatrist notes that he is experiencing thought latency, poverty of content of thoughts, word-finding difficulties, and circumlocution. Mr. M denies any perceptual abnormalities, and there is no evidence of delusions.

[polldaddy:11320112]

The authors’ observations

Mr. M’s symptoms are significant for subacute cognitive decline that is subtle but gradual and can be easily missed, especially in the beginning. Though his ED evaluation—including brain imaging—ruled out acute or focal neurologic findings and his primary psychiatric presentation was anxiety, Mr. M’s medical history and mental status exam were suggestive of cognitive deficits.

Collateral information was obtained from his work colleagues, which confirmed both cognitive problems and comorbid anxiety. Additionally, given Mr. M’s high cognitive baseline as a surgeon, the new-onset cognitive changes over 4 months warranted further cognitive and neurologic evaluation. There are many causes of cognitive impairment (vascular, cancer, infection, autoimmune, medications, substances or toxins, neurodegenerative, psychiatric, vitamin deficiencies), all of which need to be considered in a patient with a nonspecific presentation such as Mr. M’s. The psychiatrist confirmed Mr. M’s current medication regimen, and discussed tapering aripiprazole while continuing duloxetine and buspirone.

Continue to: EVALUATION A closer look at cognitive deficits

EVALUATION A closer look at cognitive deficits

Mr. M scores 12/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicating moderate cognitive impairment (Table 1). The psychiatrist refers Mr. M to Neurology. During his neurologic evaluation, Mr. M continues to report feeling anxious that “something is wrong” and skips his words. The neurologist confirms Mr. M’s symptoms may have started 2 to 3 months before he presented to the ED. Mr. M reports unusual eating habits, including yogurt and cookies for breakfast, Mexican food for lunch, and more cookies for dinner. He denies having a fever, gaining or losing weight, rashes, headaches, neck stiffness, tingling or weakness or stiffness of limbs, vertigo, visual changes, photophobia, unsteady gait, bowel or bladder incontinence, or tremors.

When the neurologist repeats the MoCA, Mr. M again scores 12. The neurologist notes that Mr. M answers questions a little slowly and pauses for thoughts when unable to find an answer. Mr. M has difficulty following some simple commands, such as “touch a finger to your nose.” Other in-office neurologic physical exams (cranial nerves, involuntary movements or tremors, sensation, muscle strength, reflexes, cerebellar signs) are unremarkable except for mildly decreased vibration sense of his toes. The neurologist concludes that Mr. M’s presentation is suggestive of subacute to chronic bradyphrenia and orders additional evaluation, including neuropsychological testing.

[polldaddy:11320114]

The authors’ observations

Physical and neurologic exams were not suggestive of any obvious causes of cognitive decline. Both the mental status exam and 2 serial MoCAs suggested deficits in executive function, language, and memory. Each of the differential diagnoses considered was ruled out with workup or exams (Table 2), which led to a most likely diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorder with PPA. Neuropsychological testing confirmed the diagnosis of nonfluent PPA.

Primary progressive aphasia

PPA is an uncommon, heterogeneous group of disorders stemming from focal degeneration of language-governing centers of the brain.1,2 The estimated prevalence of PPA is 3 in 100,000 cases.2,3 There are 4 major variants of PPA (Table 34), and each presents with distinct language, cognitive, neuroanatomical, and neuropathological characteristics.4 PPA is usually diagnosed in late middle life; however, diagnosis is often delayed due to the relative obscurity of the disorder.4 In Mr. M’s case, it took approximately 4 months of evaluations by various specialists before a diagnosis was confirmed.

The initial phase of PPA can present as a diagnostic challenge because patients can have difficulty articulating their cognitive and language deficits. PPA can be commonly mistaken for a primary psychiatric disorder such as MDD or anxiety, which can further delay an accurate diagnosis and treatment. Special attention to the mental status exam, close observation of the patient’s language, and assessment of cognitive abilities using standardized screenings such as the MoCA or Mini-Mental State Examination can be helpful in clarifying the diagnosis. It is also important to rule out developmental problems (eg, dyslexia) and hearing difficulties, particularly in older patients.

Continue to: TREATMENT Adjusting the medication regimen

TREATMENT Adjusting the medication regimen

The neurologist completes additional examinations to rule out causes of rare neurodegenerative disorders, including CSF autoimmune disorders, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and Alzheimer disease (AD) (Table 4). Mr. M continues to follow up with his outpatient psychiatrist and his medication regimen is adjusted. Aripiprazole and buspirone are discontinued, and duloxetine is titrated to 60 mg twice a day. During follow-up visits, Mr. M discusses his understanding of his neurologic condition. His concerns shift to his illness and prognosis. During these visits, he continues to deny suicidality.

[polldaddy:11320115]

The authors’ observations

Mr. M’s neurodegenerative workup identified an intriguing diagnostic challenge. A repeat brain MRI (Figure) showed atrophy patterns suggestive of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). On the other hand, his CSF ATI (A-beta 42/T-tau index, a value used to aid in the diagnosis of AD) was <1, suggesting early-onset AD.5,6 Although significant advances have been made to distinguish AD and FTLD following an autopsy, there are still no reliable or definitive biomarkers to distinguish AD from FTLD (particularly in the early stages of FTLD). This can often leave the confirmatory diagnosis as a question.7

A PPA diagnosis (and other dementias) can have a significant impact on the patient and their family due to the uncertain nature of the progression of the disease and quality-of-life issues related to language and other cognitive deficits. Early identification and accurate diagnosis of PPA and its etiology (ie, AD vs FTLD) is important to avoid unnecessary exposure to medications or the use of polypharmacy to treat an inaccurate diagnosis of a primary psychiatric illness. For example, Mr. M was being treated with 3 psychiatric medications (aripiprazole, buspirone, and duloxetine) for depression and anxiety prior to the diagnosis of PPA.

Nonpharmacologic interventions can play an important role in the management of patients with PPA. These include educating the patient and their family about the diagnosis and discussions about future planning, including appropriate social support, employment, and finances.4 Pharmacologic interventions may be limited, as there are currently no disease-modifying treatments for PPA or FTLD. For patients with nonfluent PPA or AD, cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil or N-methyl

Psychiatrists should continue to treat patients with PPA for comorbid anxiety or depression, with appropriate medications and/or supportive therapy to guide the patient through the process of grief. Assessing for suicide risk is also important in patients diagnosed with dementia. A retrospective cohort study of patients age ≥60 with a diagnosis of dementia suggested that the majority of suicides occurred in those with a new dementia diagnosis.9 End-of-life decisions such as advanced directives should be made when the patient still has legal capacity, ideally as soon as possible after diagnosis.10

OUTCOME Remaining engaged in treatment

Mr. M continues to follow-up with the Neurology team. He has also been regularly seeing his psychiatric team for medication management and supportive therapy, and his psychiatric medications have been optimized to reduce polypharmacy. During his sessions, Mr. M discusses his grief and plans for the future. Despite his anxiety about the uncertainty of his prognosis, Mr. M continues to report that he is doing reasonably well and remains engaged in treatment.

Bottom Line

Patients with primary progressive aphasia and rare neurodegenerative disorders may present to an outpatient or emergency setting with symptoms of anxiety and confusion. They are frequently misdiagnosed with a primary psychiatric disorder due to the nature of cognitive and language deficits, particularly in the early stages of the disease. Paying close attention to language and conducting cognitive screening are critical in identifying the true cause of a patient’s symptoms.

Related Resources

- Primary progressive aphasia. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/8541/primary-progressive-aphasia

- Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: A useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Donepezil • Aricept

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Memantine • Namenda

1. Grossman M. Primary progressive aphasia: clinicopathological correlations. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(2):88-97. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.216

2. Mesulam M-M, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, et al. Primary progressive aphasia and the evolving neurology of the language network. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(10):554-569. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.159

3. Coyle-Gilchrist ITS, Dick KM, Patterson K, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. Neurology. 2016;86(18):1736-1743. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002638

4. Marshall CR, Hardy CJD, Volkmer A, et al. Primary progressive aphasia: a clinical approach. J Neurol. 2018;265(6):1474-1490. doi:10.1007/s00415-018-8762-6

5. Blennow K. Cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroRx. 2004;1(2):213-225. doi:10.1602/neurorx.1.2.213

6. Hulstaert F, Blennow K, Ivanoiu A, et al. Improved discrimination of AD patients using beta-amyloid(1-42) and tau levels in CSF. Neurology. 1999;52(8):1555-1562. doi:10.1212/wnl.52.8.1555

7. Thijssen EH, La Joie R, Wolf A, et al. Diagnostic value of plasma phosphorylated tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):387-397. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0762-2

8. Newhart M, Davis C, Kannan V, et al. Therapy for naming deficits in two variants of primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology. 2009;23(7-8):823-834. doi:10.1080/02687030802661762

9. Seyfried LS, Kales HC, Ignacio RV, et al. Predictors of suicide in patients with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(6):567-573. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.01.006

10. Porteri C. Advance directives as a tool to respect patients’ values and preferences: discussion on the case of Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19(1):9. doi:10.1186/s12910-018-0249-6

1. Grossman M. Primary progressive aphasia: clinicopathological correlations. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(2):88-97. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.216

2. Mesulam M-M, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, et al. Primary progressive aphasia and the evolving neurology of the language network. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(10):554-569. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.159

3. Coyle-Gilchrist ITS, Dick KM, Patterson K, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. Neurology. 2016;86(18):1736-1743. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002638

4. Marshall CR, Hardy CJD, Volkmer A, et al. Primary progressive aphasia: a clinical approach. J Neurol. 2018;265(6):1474-1490. doi:10.1007/s00415-018-8762-6

5. Blennow K. Cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroRx. 2004;1(2):213-225. doi:10.1602/neurorx.1.2.213

6. Hulstaert F, Blennow K, Ivanoiu A, et al. Improved discrimination of AD patients using beta-amyloid(1-42) and tau levels in CSF. Neurology. 1999;52(8):1555-1562. doi:10.1212/wnl.52.8.1555

7. Thijssen EH, La Joie R, Wolf A, et al. Diagnostic value of plasma phosphorylated tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):387-397. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0762-2

8. Newhart M, Davis C, Kannan V, et al. Therapy for naming deficits in two variants of primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology. 2009;23(7-8):823-834. doi:10.1080/02687030802661762

9. Seyfried LS, Kales HC, Ignacio RV, et al. Predictors of suicide in patients with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(6):567-573. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.01.006

10. Porteri C. Advance directives as a tool to respect patients’ values and preferences: discussion on the case of Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19(1):9. doi:10.1186/s12910-018-0249-6

More on psilocybin

I would like to remark on “Psychedelics for treating psychiatric disorders: Are they safe?” (

The Oregon Psilocybin Services that will begin in 2023 are not specific to therapeutic use; this is a common misconception. These are specifically referred to as “psilocybin services” in the Oregon Administrative Rules (OAR), and psilocybin facilitators are required to limit their scope such that they are not practicing psychotherapy or other interventions, even if they do have a medical or psychotherapy background. The intention of the Oregon Psilocybin Services rollout was that these services would not be of the medical model. In the spirit of this, services do not require a medical diagnosis or referral, and services are not a medical or clinical treatment (OAR 333-333-5040). Additionally, services cannot be provided in a health care facility (OAR 441). Facilitators receive robust training as defined by Oregon law, and licensed facilitators provide this information during preparation for services. When discussing this model on a large public scale, I have noticed substantial misconceptions; it is imperative that we refer to these services as they are defined so that individuals with mental health conditions who seek them are aware that such services are different from psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Instead, Oregon Psilocybin Services might be better categorized as supported psilocybin use.

I would like to remark on “Psychedelics for treating psychiatric disorders: Are they safe?” (

The Oregon Psilocybin Services that will begin in 2023 are not specific to therapeutic use; this is a common misconception. These are specifically referred to as “psilocybin services” in the Oregon Administrative Rules (OAR), and psilocybin facilitators are required to limit their scope such that they are not practicing psychotherapy or other interventions, even if they do have a medical or psychotherapy background. The intention of the Oregon Psilocybin Services rollout was that these services would not be of the medical model. In the spirit of this, services do not require a medical diagnosis or referral, and services are not a medical or clinical treatment (OAR 333-333-5040). Additionally, services cannot be provided in a health care facility (OAR 441). Facilitators receive robust training as defined by Oregon law, and licensed facilitators provide this information during preparation for services. When discussing this model on a large public scale, I have noticed substantial misconceptions; it is imperative that we refer to these services as they are defined so that individuals with mental health conditions who seek them are aware that such services are different from psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Instead, Oregon Psilocybin Services might be better categorized as supported psilocybin use.

I would like to remark on “Psychedelics for treating psychiatric disorders: Are they safe?” (

The Oregon Psilocybin Services that will begin in 2023 are not specific to therapeutic use; this is a common misconception. These are specifically referred to as “psilocybin services” in the Oregon Administrative Rules (OAR), and psilocybin facilitators are required to limit their scope such that they are not practicing psychotherapy or other interventions, even if they do have a medical or psychotherapy background. The intention of the Oregon Psilocybin Services rollout was that these services would not be of the medical model. In the spirit of this, services do not require a medical diagnosis or referral, and services are not a medical or clinical treatment (OAR 333-333-5040). Additionally, services cannot be provided in a health care facility (OAR 441). Facilitators receive robust training as defined by Oregon law, and licensed facilitators provide this information during preparation for services. When discussing this model on a large public scale, I have noticed substantial misconceptions; it is imperative that we refer to these services as they are defined so that individuals with mental health conditions who seek them are aware that such services are different from psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Instead, Oregon Psilocybin Services might be better categorized as supported psilocybin use.

Lithium toxicity: Lessons learned

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Lithium carbonate is a mood stabilizer that is effective in the treatment of bipolar disorder, particularly in controlling mania.1 Lithium can reduce the risk of suicide,2 treat aggression and self-mutilating behavior,3 and prevent steroid-induced psychosis.4 It also can raise the white cell count in patients with clozapine-induced leukopenia.5

To prevent or lower the risk of relapse, the therapeutic plasma level of lithium should be regularly monitored to ensure an optimal concentration in the CNS. The highest tolerable level of lithium in the plasma is 0.6 to 0.8 mmol/L, with the optimal level ranging up to 1.2 mmol/L.6 Regular monitoring of renal function is also required to prevent renal toxicity, particularly if the plasma level exceeds 0.8 mmol/L.7 Because of lithium’s relatively narrow therapeutic index, its interaction with other medications, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and carbamazepine, can also precipitate lithium toxicity.8 We describe a lesson learned from a case of lithium toxicity in an otherwise healthy patient with bipolar disorder.

Case report

An otherwise healthy 39-year-old woman diagnosed with bipolar type I disorder was receiving valproate sodium 600 mg/d and olanzapine 10 mg/d. Despite improvement in her mood, she gained 11.6 kg following 6 months of treatment. As a result, olanzapine was switched to aripiprazole 10 mg/d that was later increased to 15 mg/d, and sodium valproate was gradually optimized up to 1,000 mg/d. She later complained of hair thinning and hair loss so she self-adjusted her medication dosages, which resulted in frequent relapses. Her mood stabilizer was changed from sodium valproate to lithium 600 mg/d.

Unfortunately, after taking lithium for 15 days, she returned to us with fever associated with reduced oral intake, poor sleep, bilateral upper limb rigidity, and bilateral hand tremor. She also complained of extreme thirst and fatigue but no vomiting or diarrhea. She had difficulty falling asleep and slept for only 1 to 2 hours a day. Her symptoms worsened when a general practitioner prescribed NSAIDs for her fever and body ache. Her tremors were later generalized, which made it difficult for her to take her oral medications and disturbed her speech and movement.

On evaluation, our patient appeared comfortable and not agitated. She was orientated to time, place, and person. Her blood pressure was 139/89 mmHg, heart rate was 104 bpm, and she was afebrile. She was dehydrated with minimal urine output. She had coarse tremor in her upper and lower limbs, which were hypertonic but did not display hyperreflexia or clonus. There was no nystagmus or ataxia. A mental state examination showed no signs of manic, hypomanic, or depressive symptoms. She had slurred speech, and her affect was restricted.

Blood investigation revealed a suprathreshold lithium level of 1.70 mmol/L (normal: 0.8 to 1.2 mmol/L). Biochemical parameters showed evidence of acute kidney injury (urea: 6.1 mmol/L; creatinine: 0.140 mmol/L), with no electrolyte imbalance. There was no evidence of hypothyroidism (thyroid-stimulating hormone: 14.9 mIU/L; free thyroxine: 9.9 pmol/L), hyperparathyroidism, or hypercalcemia. Autoimmune markers were positive for antinuclear antibody (titre 1:320) and anti-double stranded DNA (76.8 IU/mL). Apart from hair loss, she denied other symptoms associated with autoimmune disease, such as joint pain, butterfly rash, or persistent fatigue. Other routine blood investigations were within normal limits. Her urine protein throughout admission had shown persistent proteinuria ranging from 3+ to 4+. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed normal sinus rhythm with no T wave inversion or QT prolongation.

Continue to: A detailed family history...

A detailed family history later confirmed a strong family history of renal disease: her mother had lupus nephritis with nephrotic syndrome, and her brother had died from complications of a rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Her renal function prior to lithium initiation was within normal limits (urea: 4.0 mmol/L; serum creatinine: 78 µmol/L).

In the ward, lithium and aripiprazole were discontinued, and she was hydrated. Combined care with the psychiatric and medical teams was established early to safeguard against potential CNS deterioration. She showed marked clinical improvement by Day 3, with the resolution of coarse tremor and rigidity as well as normalization of blood parameters. Her lithium level returned to a therapeutic level by Day 4 after lithium discontinuation, and her renal profile gradually normalized. She was restarted on aripiprazole 10 mg/d for her bipolar illness and responded well. She was discharged on Day 5 with a referral to the nephrology team for further intervention.

Lessons learned

This case highlights the issue of lithium safety in susceptible individuals and the importance of risk stratification in this group of patients. Lithium is an effective treatment for bipolar I disorder and has also been used as adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder, schizoaffective disorder, treatment-resistant schizophrenia, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, and the control of chronic aggression.9 Lithium is completely absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract following ingestion, is not metabolized, and is eliminated almost entirely by the kidneys (though trace amounts may be found in feces and perspiration).

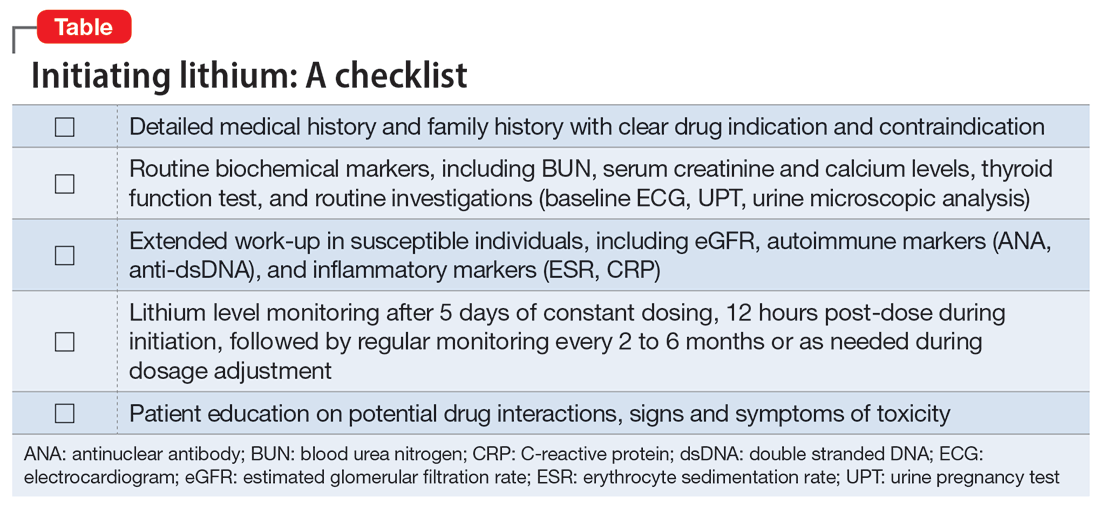

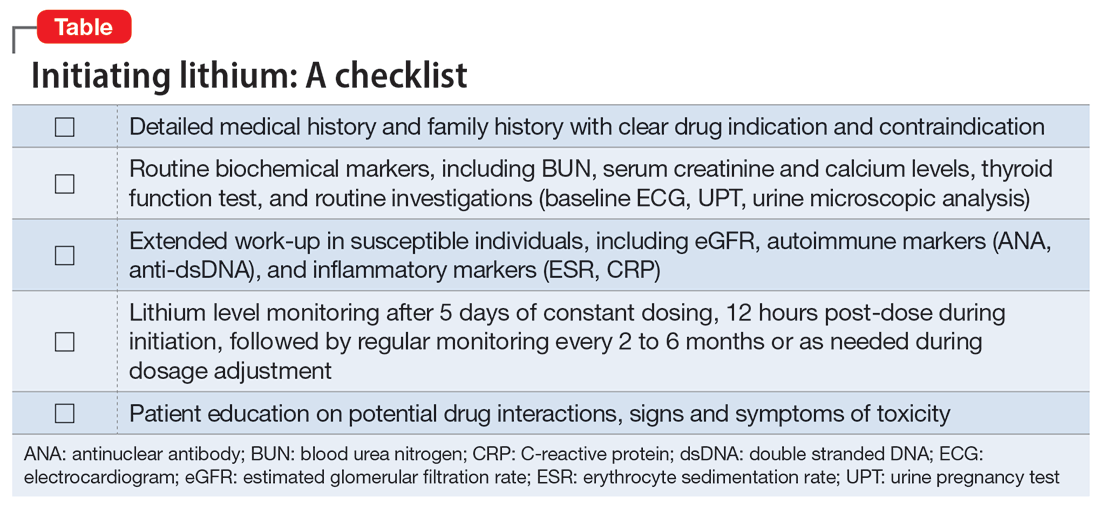

In our case, a detailed family history of renal disease was not adequately explored until our patient presented with signs suggestive of lithium toxicity. Our patient had been prescribed lithium 600 mg/d as a maintenance therapy. Upon starting lithium, her baseline biochemical parameters were within normal limits, and renal issues were not suspected. The hair thinning and hair loss she experienced could have been an adverse effect of valproate sodium or a manifestation of an underlying autoimmune disease. Coupled with the use of NSAIDs that could have precipitated acute kidney injury, her poor oral intake and dehydration during the acute illness further impaired lithium excretion, leading to a suprathreshold plasma level despite a low dose of lithium. Therefore, before prescribing lithium, a thorough medical and family history is needed, supplemented by an evaluation of renal function, serum electrolytes, and thyroid function to determine the starting dosage of lithium. Routine vital sign assessment and ECG should also be conducted, and concurrent medications and pregnancy status should be confirmed before prescribing lithium. Regular lithium level monitoring is essential.

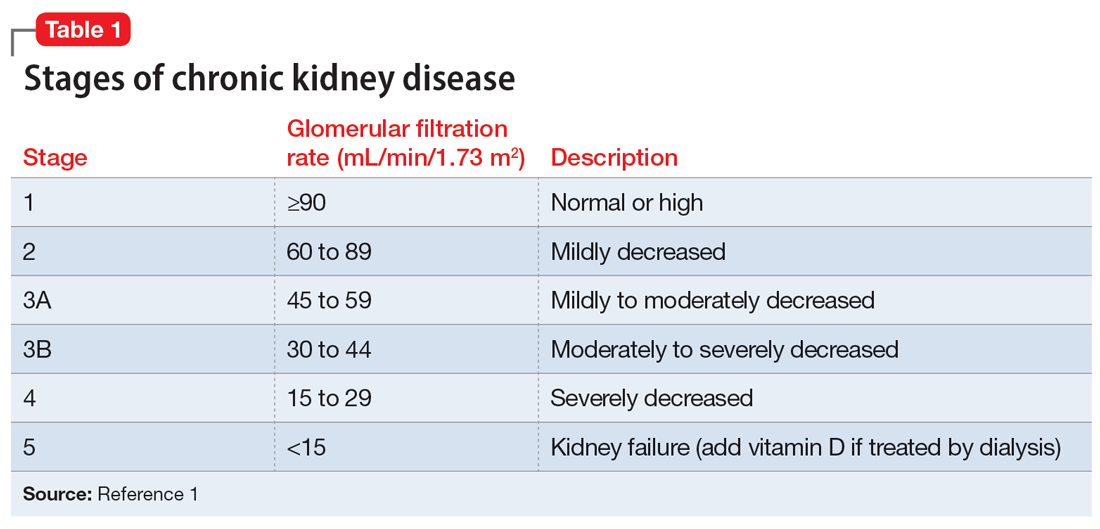

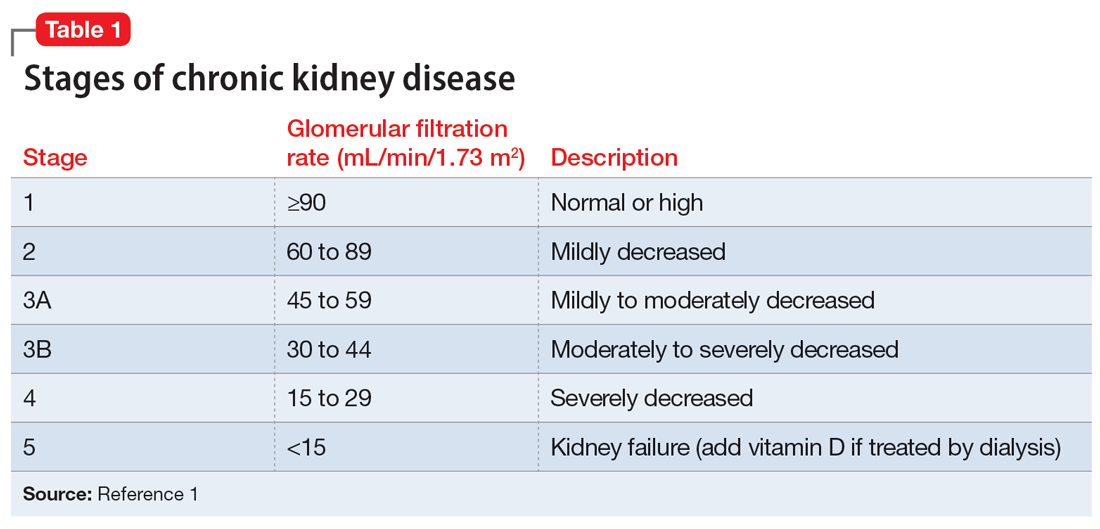

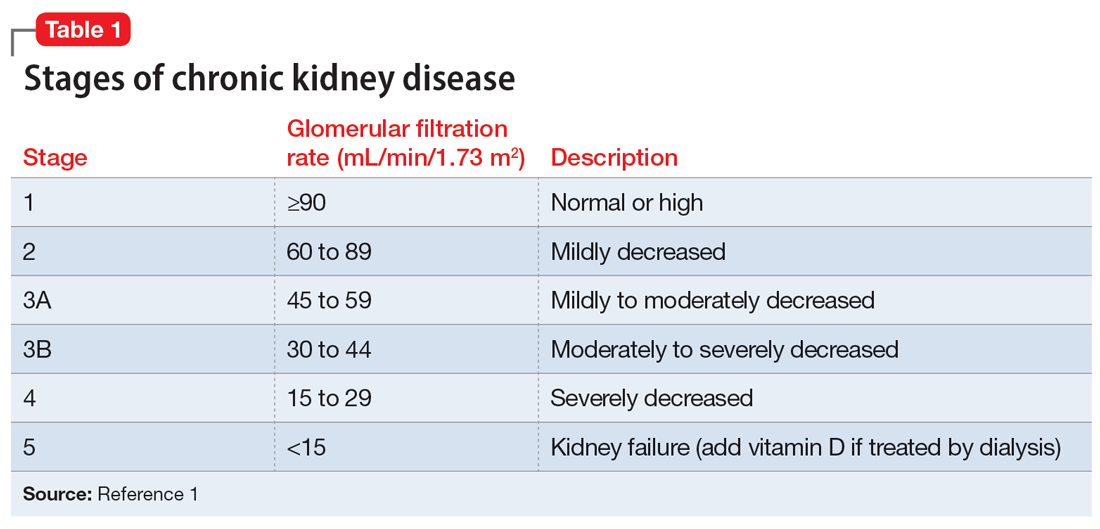

Measuring a patient’s estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is recommended to validate renal status10 and classify and stage kidney disease.11 Combining eGFR with blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and urine microscopic analysis further improves the prediction of renal disease in early stages. We recommend considering a blood test for autoimmune markers in patients with clinical suspicion of autoimmune disease, in the presence of suggestive signs and symptoms, and/or in patients with a positive family history (Table).