User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

GLP-1 agonists for weight loss: What you need to know

Obesity and overweight, with or without metabolic dysregulation, pose vexing problems for many patients with mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorders. More than one-half of individuals with severe mental illnesses are obese or overweight,1 resulting from multiple factors that may include psychiatric symptoms (eg, anergia and hyperphagia), poor dietary choices, sedentary lifestyle, underlying inflammatory processes, medical comorbidities, and iatrogenic consequences of certain medications. Unfortunately, numerous psychotropic medications can increase weight and appetite due to a variety of mechanisms, including antihistaminergic effects, direct appetite-stimulating effects, and proclivities to cause insulin resistance. While individual agents can vary, a recent review identified an overall 2-fold increased risk for rapid, significant weight gain during treatment with antipsychotics as a class.2 In addition to lifestyle modifications (diet and exercise), many pharmacologic strategies have been proposed to counter iatrogenic weight gain, including appetite suppressants (eg, pro-dopaminergic agents such as phentermine, stimulants, and amantadine), pro-anorectant anticonvulsants (eg, topiramate or zonisamide), opioid receptor antagonists (eg, olanzapine/samidorphan or naltrexone) and oral hypoglycemics such as metformin. However, the magnitude of impact for most of these agents to reverse iatrogenic weight gain tends to be modest, particularly once significant weight gain (ie, ≥7% of initial body weight) has already occurred.

Pharmacologic strategies to modulate or enhance the effects of insulin hold particular importance for combatting psychotropic-associated weight gain. Insulin transports glucose from the intravascular space to end organs for fuel consumption; to varying degrees, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and some other psychotropic medications can cause insulin resistance. This in turn leads to excessive storage of underutilized glucose in the liver (glycogenesis), the potential for developing fatty liver (ie, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis), and conversion of excess carbohydrates to fatty acids and triglycerides, with subsequent storage in adipose tissue. Medications that can enhance the activity of insulin (so-called incretin mimetics) can help to overcome insulin resistance caused by SGAs (and potentially by other psychotropic medications) and essentially lead to weight loss through enhanced “fuel efficiency.”

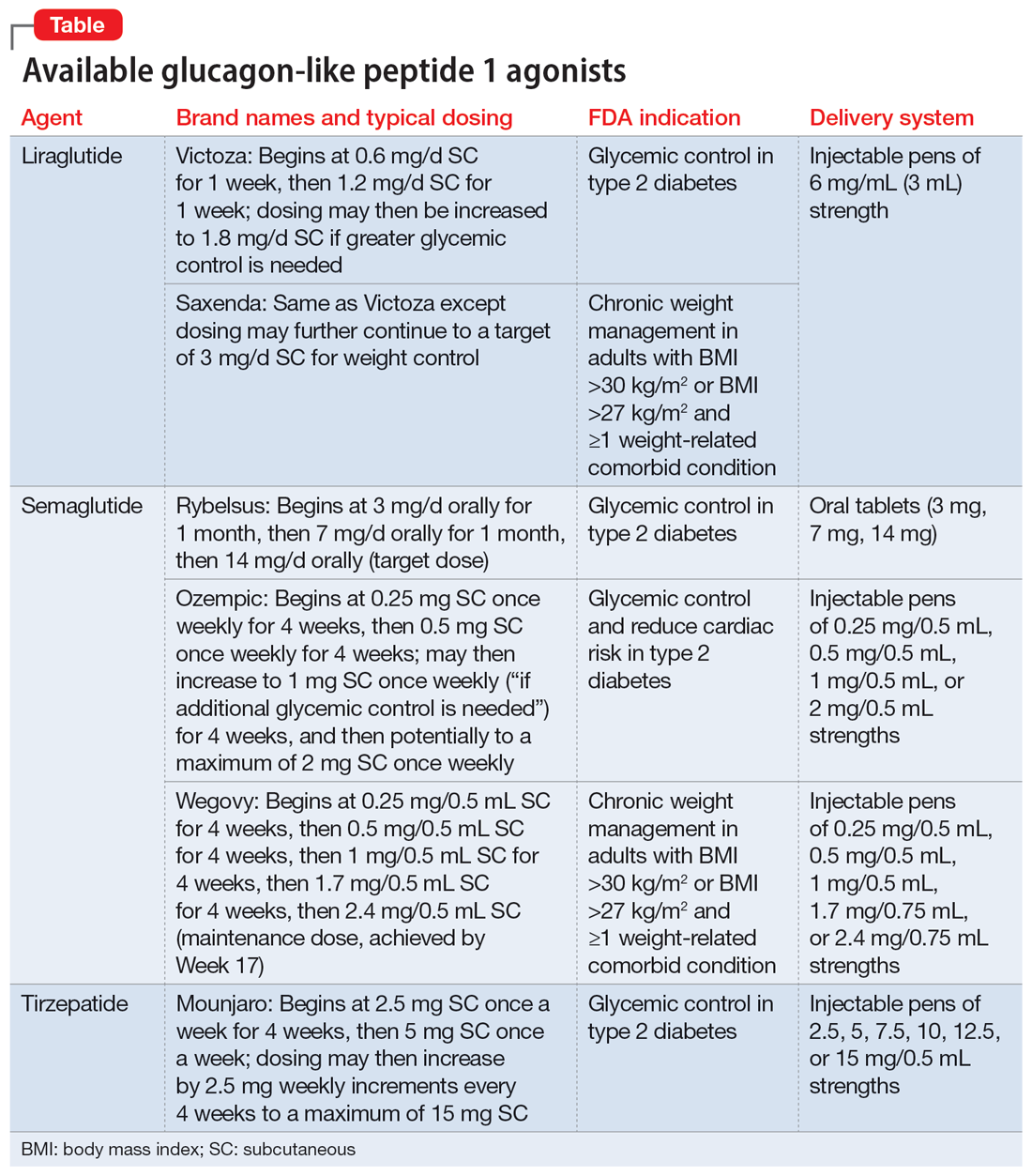

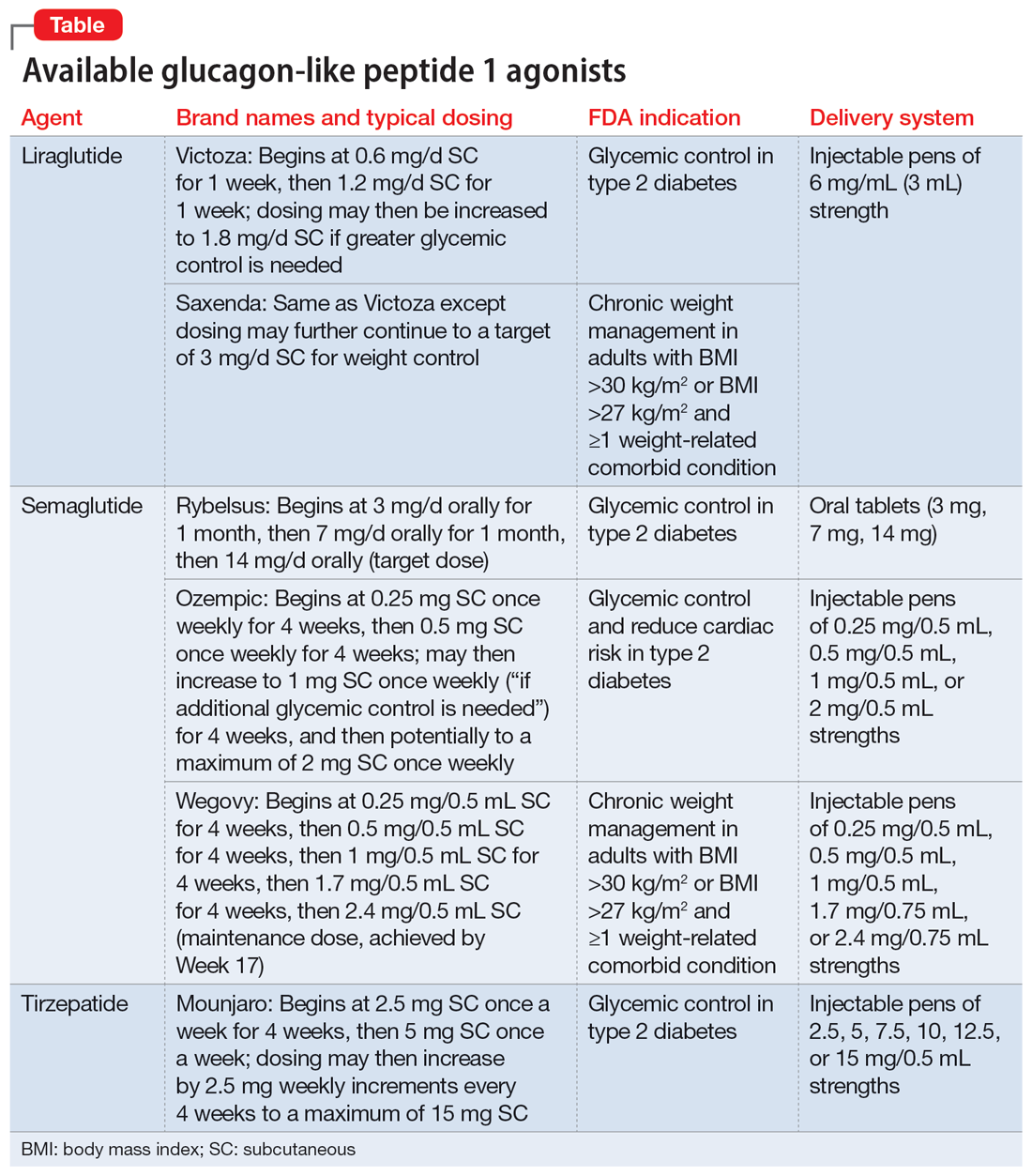

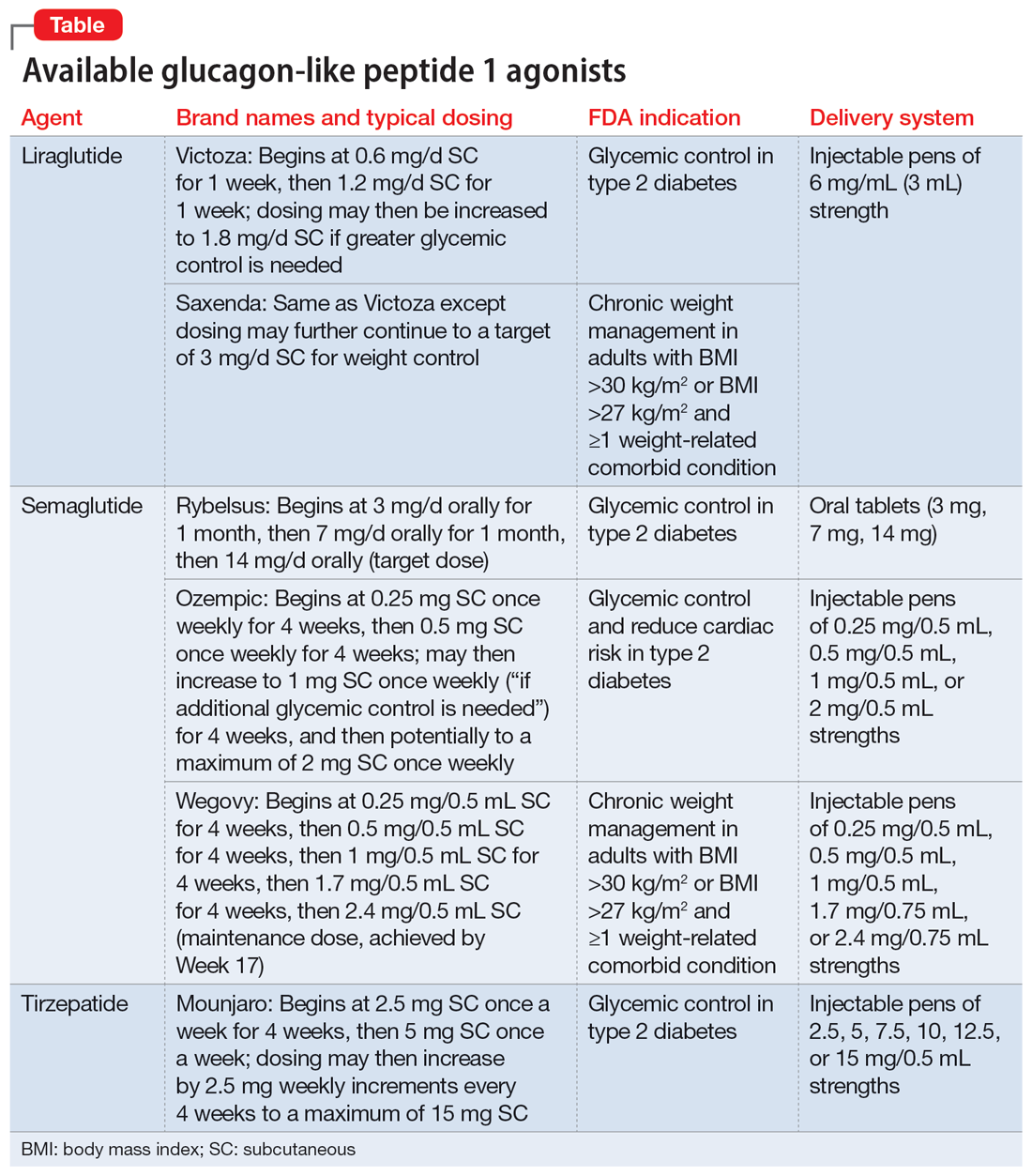

Metformin, typically dosed up to 1,000 mg twice daily with meals, has increasingly become recognized as a first-line strategy to attenuate weight gain and glycemic dysregulation from SGAs via its ability to reduce insulin resistance. Yet meta-analyses have shown that although results are significantly better than placebo, overall long-term weight loss from metformin alone tends to be rather modest (<4 kg) and associated with a reduction in body mass index (BMI) of only approximately 1 point.3 Psychiatrists (and other clinicians who prescribe psychotropic medications that can cause weight gain or metabolic dysregulation) therefore need to become familiar with alternative or adjunctive weight loss options. The use of a relatively new class of incretin mimetics called glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists (Table) has been associated with profound and often dramatic weight loss and improvement of glycemic parameters in patients with obesity and glycemic dysregulation.

What are GLP-1 agonists?

GLP-1 is a hormone secreted by L cells in the intestinal mucosa in response to food. GLP-1 agonists reduce blood sugar by increasing insulin secretion, decreasing glucagon release (thus downregulating further increases in blood sugar), and reducing insulin resistance. GLP-1 agonists also reduce appetite by directly stimulating the satiety center and slowing gastric emptying and GI motility. In addition to GLP-1 agonism, some medications in this family (notably tirzepatide) also agonize a second hormone, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, which can further induce insulin secretion as well as decrease stomach acid secretion, potentially delivering an even more substantial reduction in appetite and weight.

Routes of administration and FDA indications

Due to limited bioavailability, most GLP-1 agonists require subcutaneous (SC) injections (the sole exception is the Rybelsus brand of semaglutide, which comes in a daily pill form). Most are FDA-approved not specifically for weight loss but for patients with type 2 diabetes (defined as a hemoglobin A1C ≥6.5% or a fasting blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dL). Weight loss represents a secondary outcome for GLP-1 agonists FDA-approved for glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. The 2 current exceptions to this classification are the Wegovy brand of semaglutide (ie, dosing of 2.4 mg) and the Saxenda brand of liraglutide, both of which carry FDA indications for chronic weight management alone (when paired with dietary and lifestyle modification) in individuals who are obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes, or for persons who are overweight (BMI >27 kg/m2) and have ≥1 weight-related comorbid condition (eg, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia). Although patients at risk for diabetes (ie, prediabetes, defined as a hemoglobin A1C 5.7% to 6.4% or a fasting blood glucose level 100 to 125 mg/dL) were included in FDA registration trials of Saxenda or Wegovy, prediabetes is not an FDA indication for any GLP-1 agonist.

Data in weight loss

Most of the existing empirical data on weight loss with GLP-1 agonists come from studies of individuals who are overweight or obese, with or without type 2 diabetes, rather than from studies using these agents to counteract iatrogenic weight gain. In a retrospective cohort study of patients with type 2 diabetes, coadministration with serotonergic antidepressants (eg, citalopram/escitalopram) was associated with attenuation of the weight loss effects of GLP-1 agonists.4

Liraglutide currently is the sole GLP-1 agonist studied for treating SGA-associated weight gain. A 16-week randomized trial compared once-daily SC injected liraglutide vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia who incurred weight gain and prediabetes after taking olanzapine or clozapine.5 Significantly more patients taking liraglutide than placebo developed normal glucose tolerance (64% vs 16%), and body weight decreased by a mean of 5.3 kg.

Continue to: In studies of semaglutide...

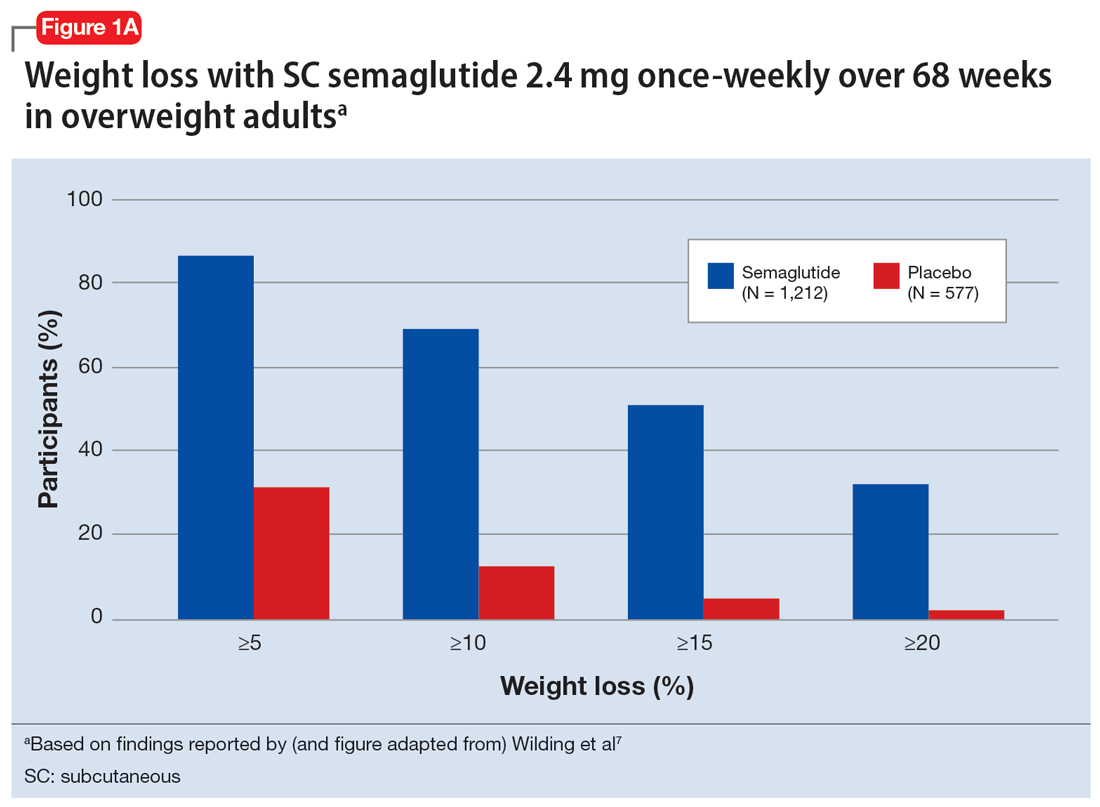

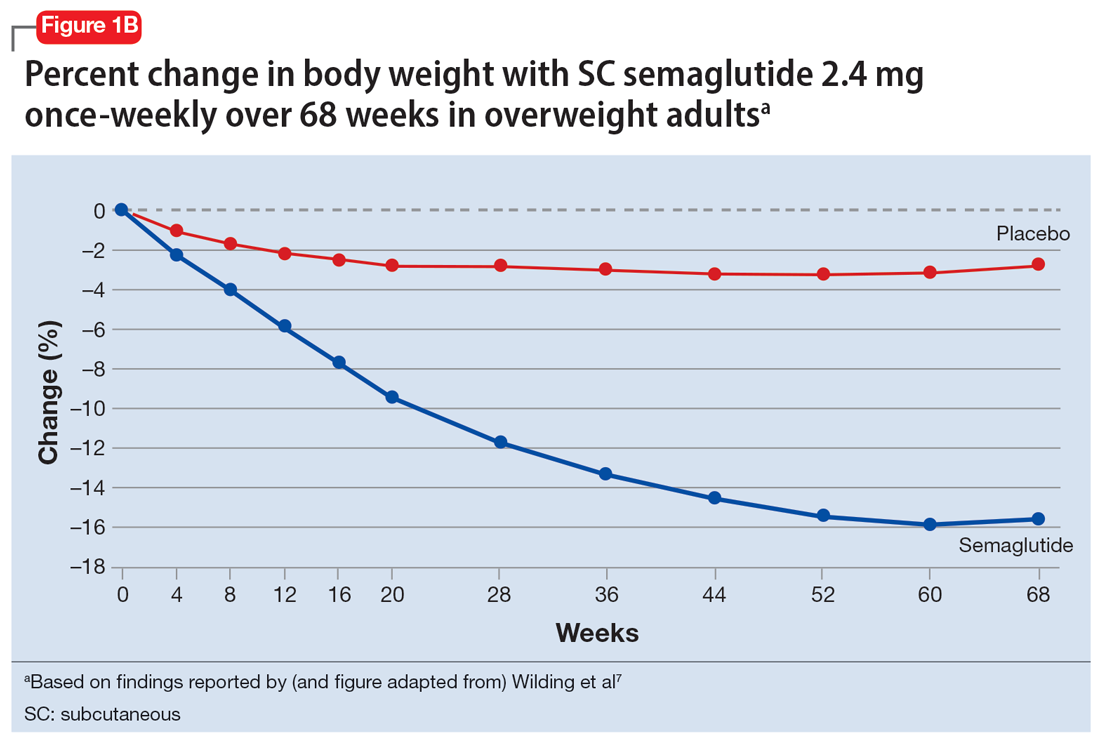

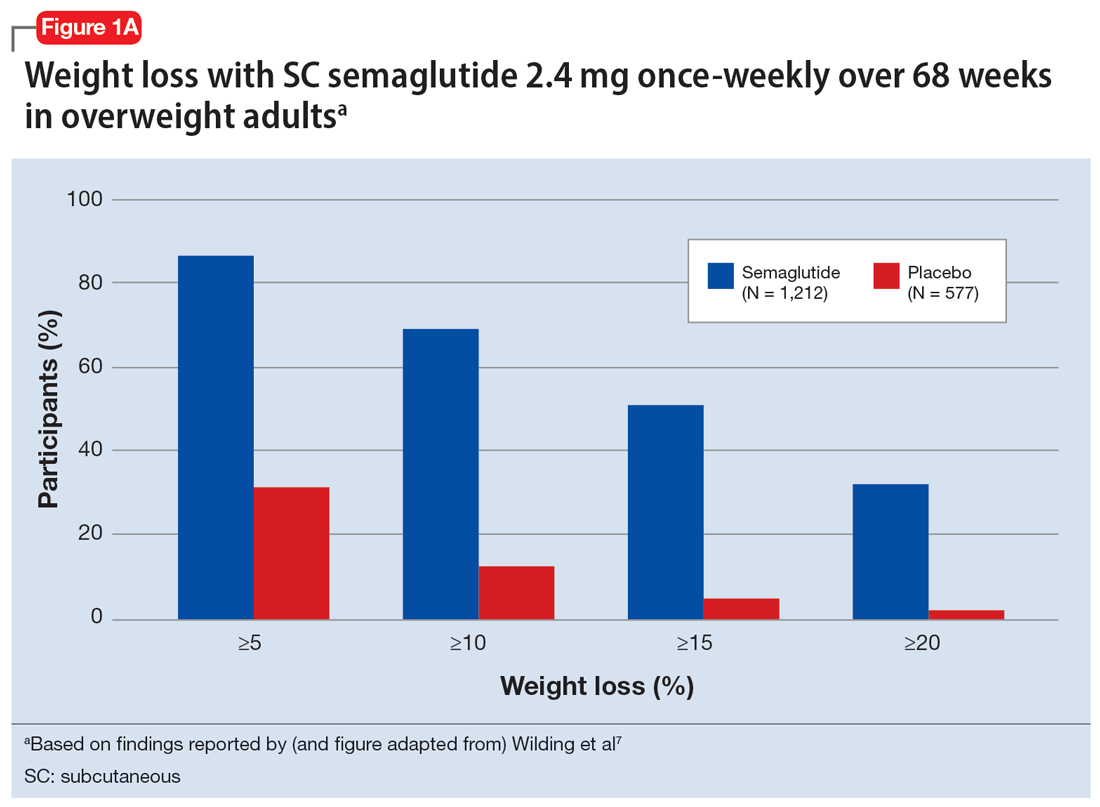

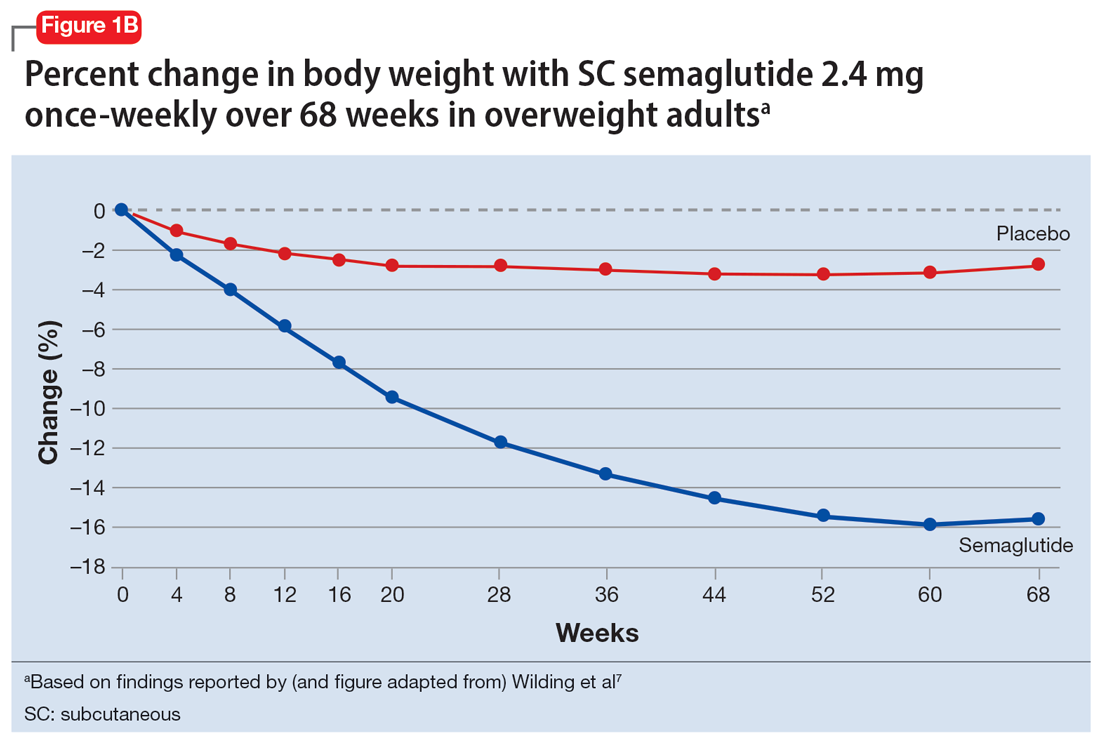

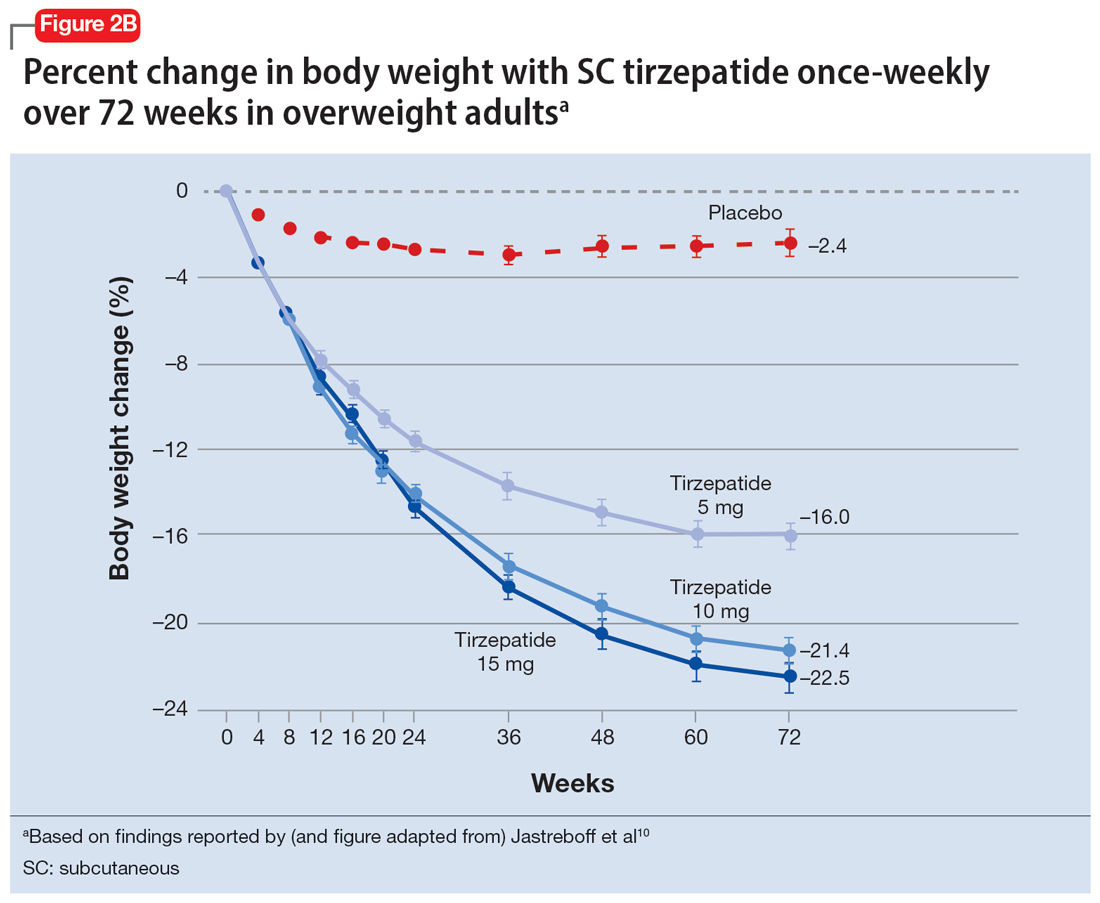

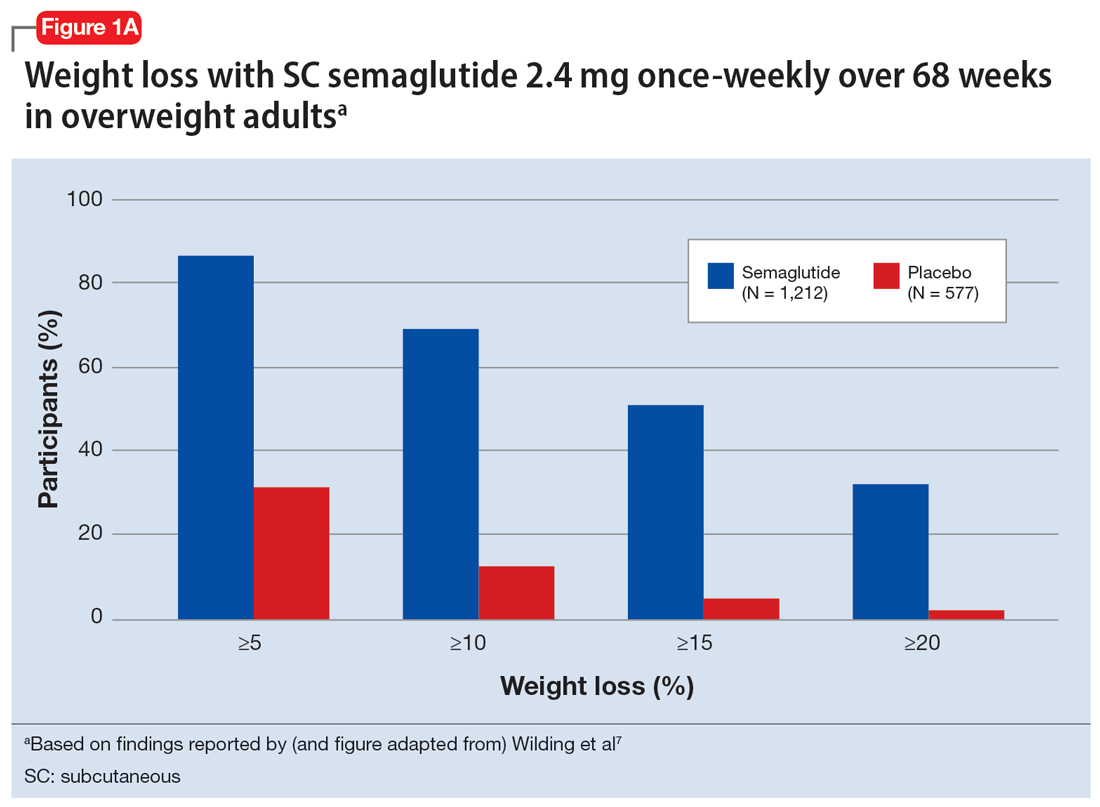

In studies of semaglutide for overweight/obese patients with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, clinical trials of oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) found a mean weight loss over 26 weeks of -1.0 kg with dosing at 7 mg/d and -2.6 kg with dosing at 14 mg/d.6 A 68-week placebo-controlled trial of semaglutide (dosed at 2.4 mg SC weekly) for overweight/obese adults who did not have diabetes yielded a -15.3 kg weight loss (vs -2.6 kg with placebo); one-half of those who received semaglutide lost 15% of their initial body weight (Figure 1A and Figure 1B).7 Similar findings with semaglutide 2.4 mg SC weekly (Wegovy) were observed in overweight/obese adolescents, with 73% of participants losing ≥5% of their baseline weight.8 A comparative randomized trial in patients with type 2 diabetes also found modestly but significantly greater weight loss with oral semaglutide than with SC liraglutide.9

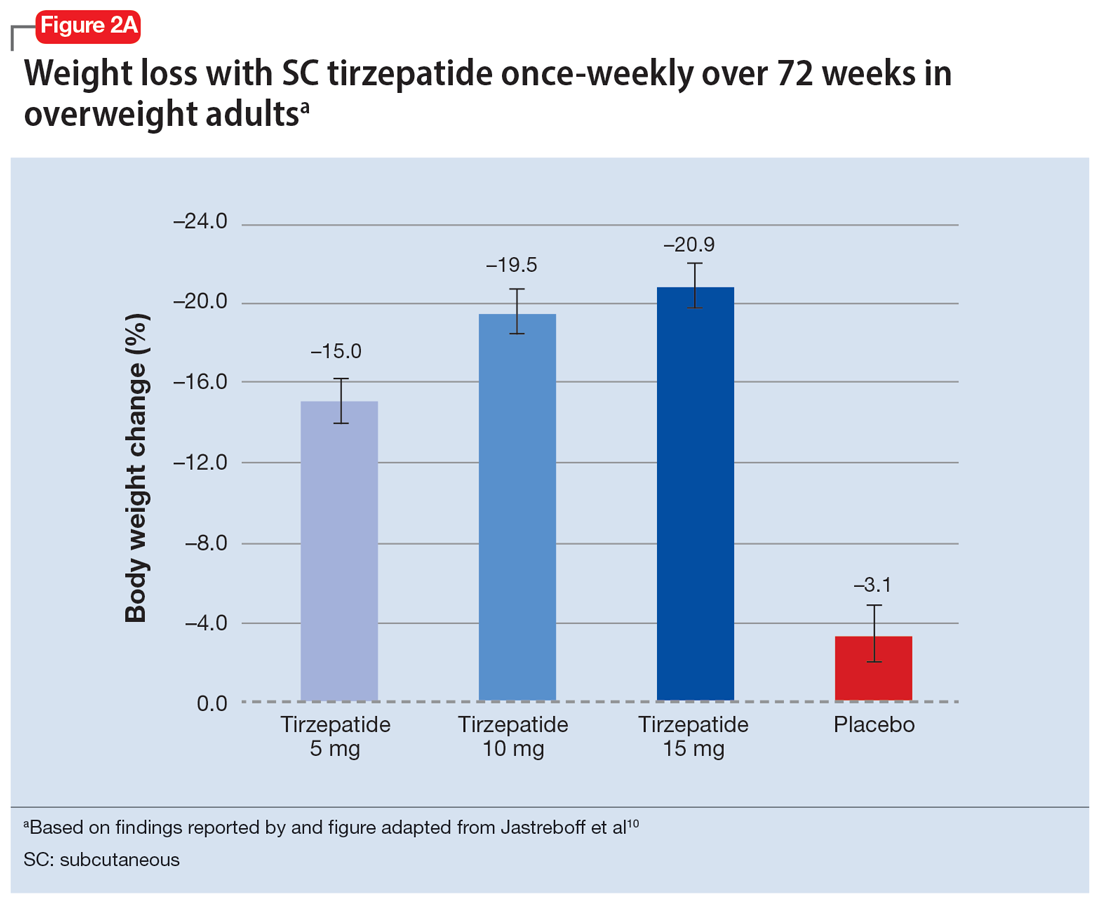

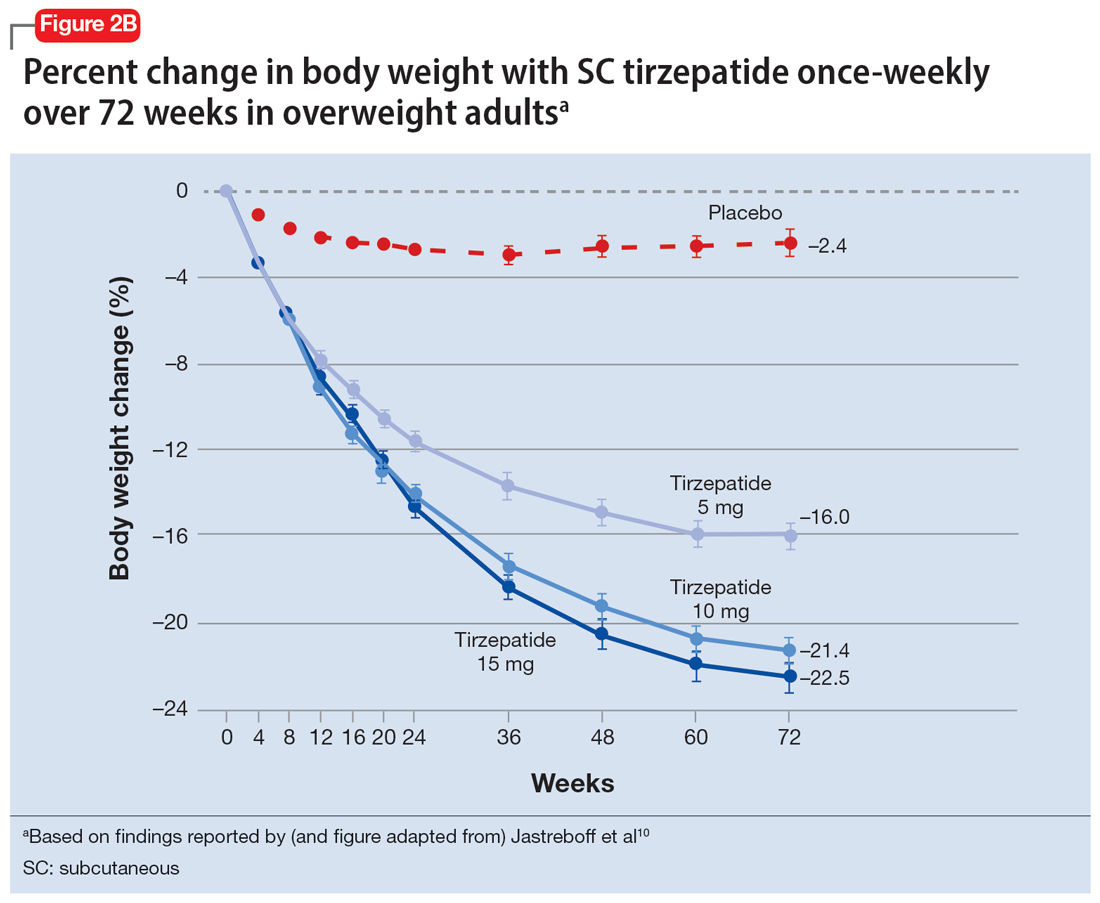

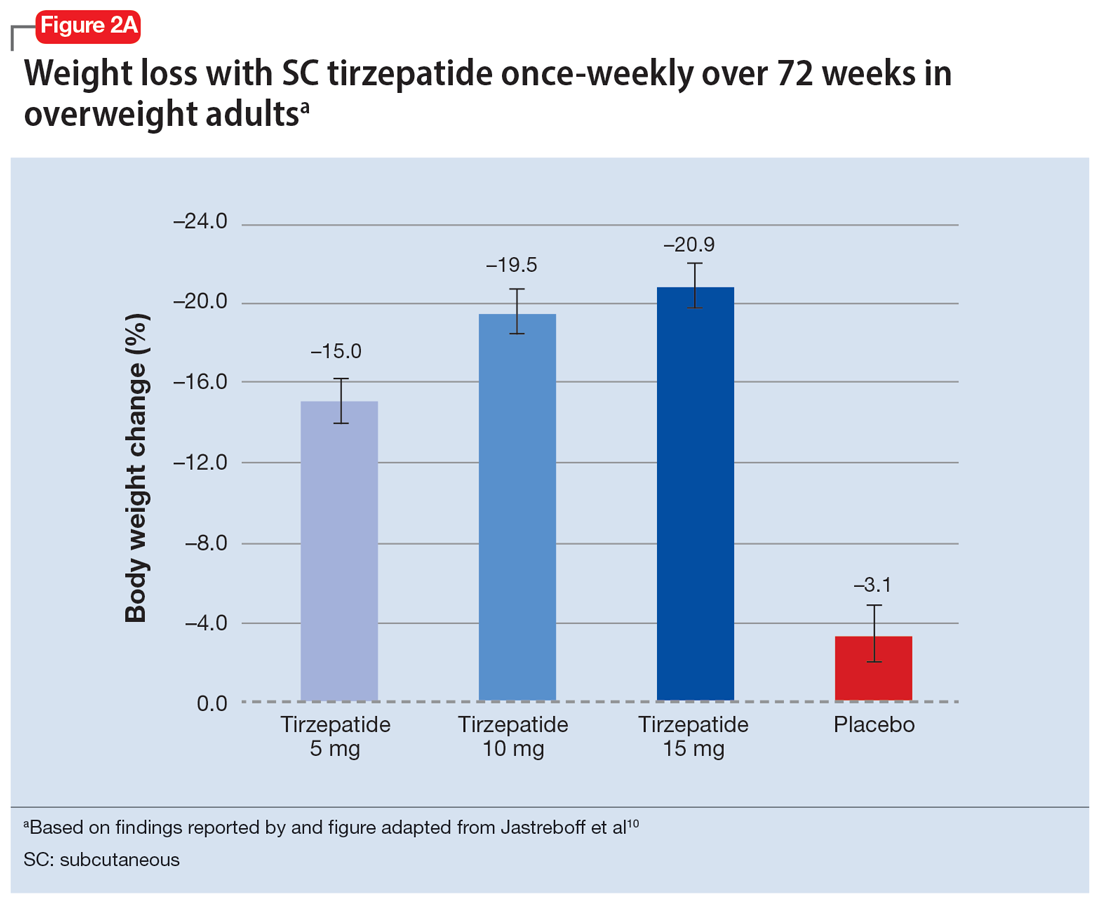

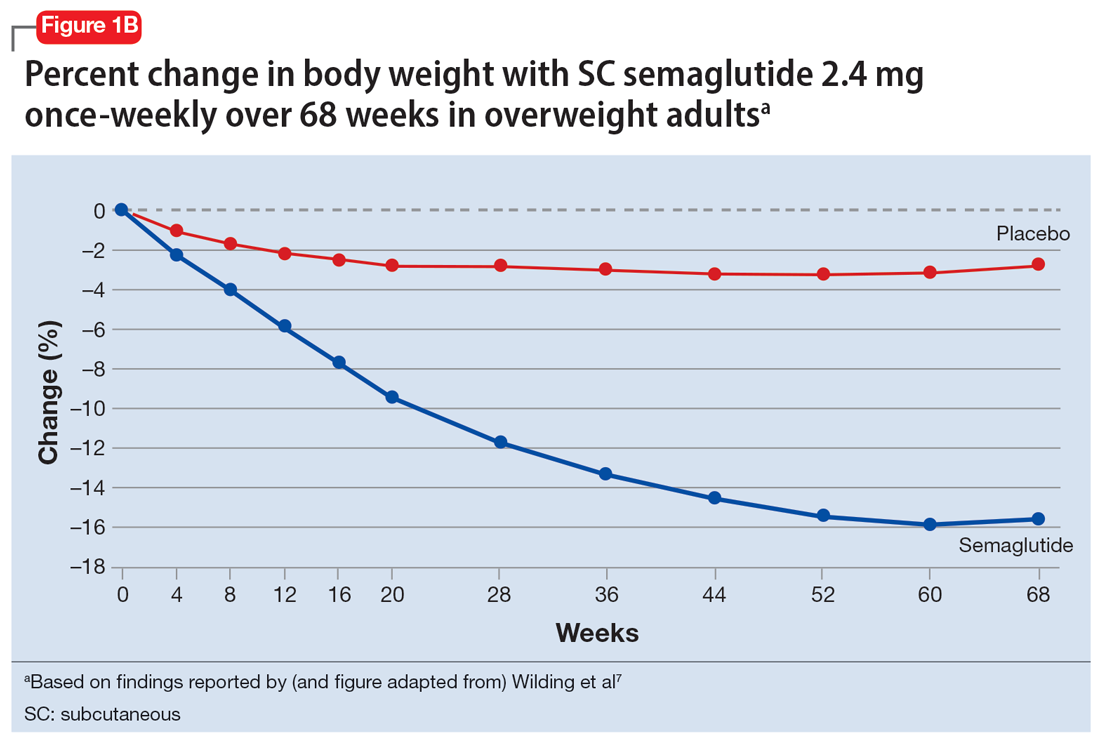

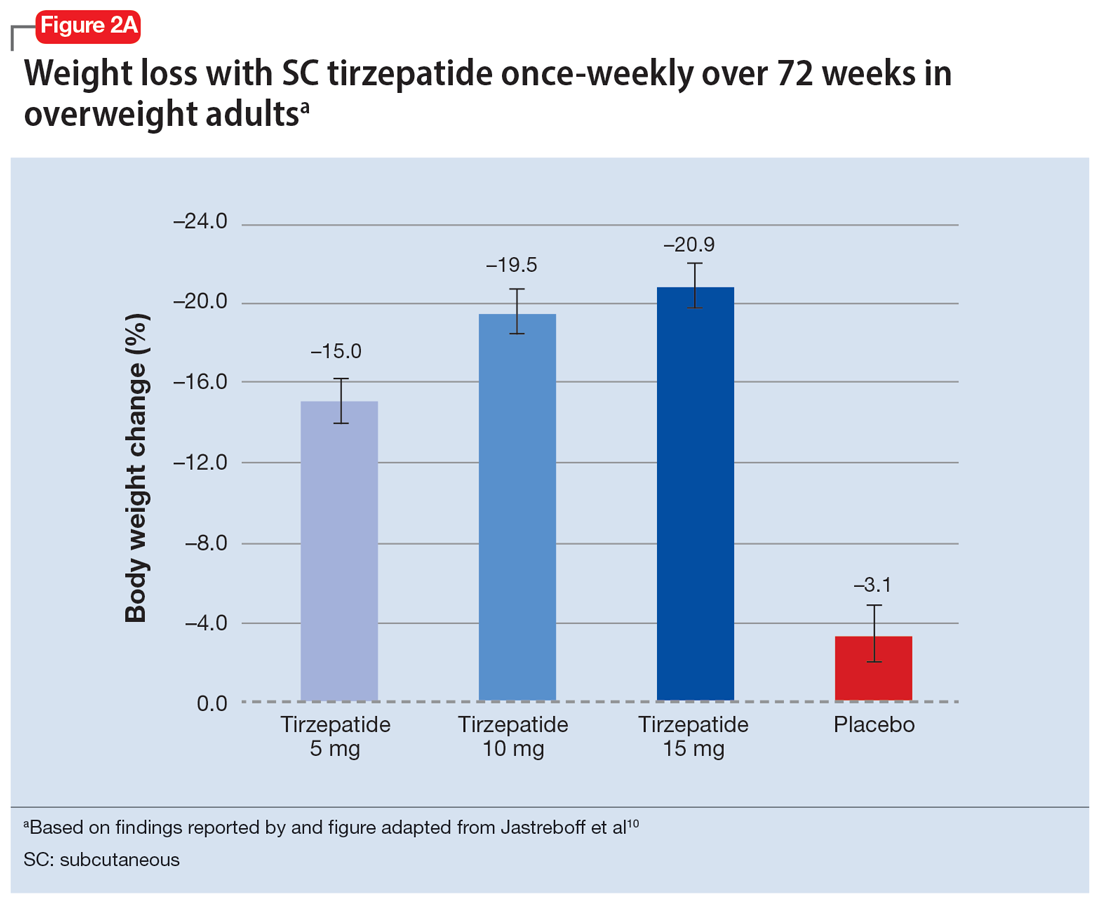

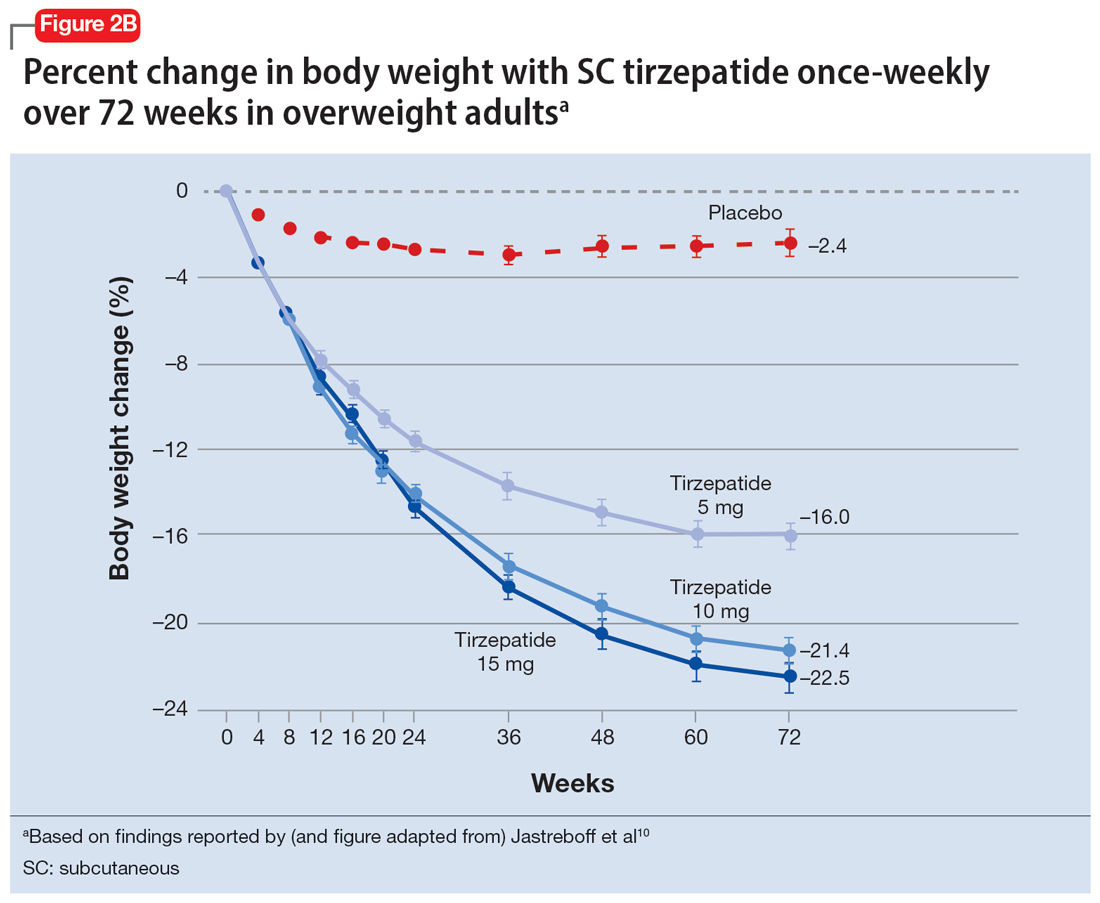

In a 72-week study of tirzepatide specifically for weight loss in nondiabetic patients who were overweight or obese, findings were especially dramatic (Figure 2A and Figure 2B).10 An overall 15% decrease in body weight was observed with 5 mg/week dosing alongside a 19.5% decrease in body weight with 10 mg/week dosing and a 20.9% weight reduction with 15 mg/week dosing.10 As noted in Figure 2B, the observed pattern of weight loss occurred along an exponential decay curve. Notably, a comparative study of tirzepatide vs once-weekly semaglutide (1 mg) in patients with type 2 diabetes11 found significantly greater dose-dependent weight loss with tirzepatide than semaglutide (-1.9 kg at 5 mg, -3.6 kg at 10 mg, and -5.5 kg at 15 mg)—although the somewhat low dosing of semaglutide may have limited its optimal possible weight loss benefit.

Tolerability

Adverse effects with GLP-1 agonists are mainly gastrointestinal (eg, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation)5-11 and generally transient. SC administration is performed in fatty tissue of the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm; site rotation is recommended to minimize injection site pain. All GLP-1 agonists carry manufacturers’ warning and precaution statements identifying the rare potential for acute pancreatitis, acute gall bladder disease, acute kidney injury, and hypoglycemia. Animal studies also have suggested an increased, dose-dependent risk for thyroid C-cell tumors with GLP-1 agonists; this has not been observed in human trials, although postmarketing pharmacovigilance reports have identified cases of medullary thyroid carcinoma in patients who took liraglutide. A manufacturer’s boxed warning indicates that a personal or family history of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid poses a contraindication for taking semaglutide, liraglutide, or tirzepatide.

Initial evidence prompts additional questions

GLP-1 agonists represent an emerging class of novel agents that can modulate glycemic dysregulation and overweight/obesity, often with dramatic results whose magnitude rivals the efficacy of bariatric surgery. Once-weekly formulations of semaglutide (Wegovy) and daily liraglutide (Saxenda) are FDA-approved for weight loss in patients who are overweight or obese while other existing formulations are approved solely for patients with type 2 diabetes, although it is likely that broader indications for weight loss (regardless of glycemic status) are forthcoming. Targeted use of GLP-1 agonists to counteract SGA-associated weight gain is supported by a handful of preliminary reports, with additional studies likely to come. Unanswered questions include:

- When should GLP-1 agonists be considered within a treatment algorithm for iatrogenic weight gain relative to other antidote strategies such as metformin or appetite-suppressing anticonvulsants?

- How effective might GLP-1 agonists be for iatrogenic weight gain from non-SGA psychotropic medications, such as serotonergic antidepressants?

- When and how can GLP-1 agonists be safely coprescribed with other nonincretin mimetic weight loss medications?

- When should psychiatrists prescribe GLP-1 agonists, or do so collaboratively with primary care physicians or endocrinologists, particularly in patients with metabolic syndrome?

Followers of the rapidly emerging literature in this area will likely find themselves best positioned to address these and other questions about optimal management of psychotropic-induced weight gain for the patients they treat.

Bottom Line

The use of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, a relatively new class of incretin mimetics, has been associated with profound and often dramatic weight loss and improvement of glycemic parameters in patients with obesity and glycemic dysregulation. Preliminary reports support the potential targeted use of GLP-1 agonists to counteract weight gain associated with second-generation antipsychotics.

Related Resources

- Singh F, Allen A, Ianni A. Managing metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(12):20-24,26. doi:10.12788/cp.0064

- Ard J, Fitch A, Fruh S, et al. Weight loss and maintenance related to the mechanism of action of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists. Adv Ther. 2021;38(6):2821- 2839. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01710-0

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Citalopram • Celexa

Clozapine • Clozaril

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Liraglutide • Victoza, Saxenda

Metformin • Glucophage

Naltrexone • ReVia

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine/samidorphan • Lybalvi

Phentermine • Ionamin

Semaglutide • Rybelsus, Ozempic, Wegovy

Tirzepatide • Mounjaro

Topiramate • Topamax

Zonisamide • Zonegran

1. Afzal M, Siddiqi N, Ahmad B, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;25;12:769309.

2. Barton BB, Segger F, Fischer K, et al. Update on weight-gain caused by antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Safety. 2020;19(3):295-314.

3. de Silva AV, Suraweera C, Ratnatunga SS, et al. Metformin in prevention and treatment of antipsychotic induced weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):341.

4. Durell N, Franks R, Coon S, et al. Effects of antidepressants on glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist-related weight loss. J Pharm Technol. 2022;38(5):283-288.

5. Larsen JR, Vedtofte L, Jakobsen MSL, et al. Effect of liraglutide treatment on prediabetes and overweight or obesity in clozapine- or olanzapine-treated patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):719-728.

6. Aroda VR, Rosenstock J, Terauchi Y, et al. PIONEER 1: randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide monotherapy in comparison with placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(9):1724-1732.

7. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(11):989-1002.

8. Weghuber D, Barrett T, Barrientos-Pérez M, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adolescents with obesity. N Engl J Med. Published online November 2, 2022. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2208601.

9. Pratley R, Amod A, Hoff ST, et al. Oral semaglutide versus subcutaneous liraglutide and placebo in type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 4): a randomized, double-blind, phase 3a trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):39-50.

10. Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):205-216.

11. Frías JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, et al. Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):503-515.

Obesity and overweight, with or without metabolic dysregulation, pose vexing problems for many patients with mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorders. More than one-half of individuals with severe mental illnesses are obese or overweight,1 resulting from multiple factors that may include psychiatric symptoms (eg, anergia and hyperphagia), poor dietary choices, sedentary lifestyle, underlying inflammatory processes, medical comorbidities, and iatrogenic consequences of certain medications. Unfortunately, numerous psychotropic medications can increase weight and appetite due to a variety of mechanisms, including antihistaminergic effects, direct appetite-stimulating effects, and proclivities to cause insulin resistance. While individual agents can vary, a recent review identified an overall 2-fold increased risk for rapid, significant weight gain during treatment with antipsychotics as a class.2 In addition to lifestyle modifications (diet and exercise), many pharmacologic strategies have been proposed to counter iatrogenic weight gain, including appetite suppressants (eg, pro-dopaminergic agents such as phentermine, stimulants, and amantadine), pro-anorectant anticonvulsants (eg, topiramate or zonisamide), opioid receptor antagonists (eg, olanzapine/samidorphan or naltrexone) and oral hypoglycemics such as metformin. However, the magnitude of impact for most of these agents to reverse iatrogenic weight gain tends to be modest, particularly once significant weight gain (ie, ≥7% of initial body weight) has already occurred.

Pharmacologic strategies to modulate or enhance the effects of insulin hold particular importance for combatting psychotropic-associated weight gain. Insulin transports glucose from the intravascular space to end organs for fuel consumption; to varying degrees, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and some other psychotropic medications can cause insulin resistance. This in turn leads to excessive storage of underutilized glucose in the liver (glycogenesis), the potential for developing fatty liver (ie, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis), and conversion of excess carbohydrates to fatty acids and triglycerides, with subsequent storage in adipose tissue. Medications that can enhance the activity of insulin (so-called incretin mimetics) can help to overcome insulin resistance caused by SGAs (and potentially by other psychotropic medications) and essentially lead to weight loss through enhanced “fuel efficiency.”

Metformin, typically dosed up to 1,000 mg twice daily with meals, has increasingly become recognized as a first-line strategy to attenuate weight gain and glycemic dysregulation from SGAs via its ability to reduce insulin resistance. Yet meta-analyses have shown that although results are significantly better than placebo, overall long-term weight loss from metformin alone tends to be rather modest (<4 kg) and associated with a reduction in body mass index (BMI) of only approximately 1 point.3 Psychiatrists (and other clinicians who prescribe psychotropic medications that can cause weight gain or metabolic dysregulation) therefore need to become familiar with alternative or adjunctive weight loss options. The use of a relatively new class of incretin mimetics called glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists (Table) has been associated with profound and often dramatic weight loss and improvement of glycemic parameters in patients with obesity and glycemic dysregulation.

What are GLP-1 agonists?

GLP-1 is a hormone secreted by L cells in the intestinal mucosa in response to food. GLP-1 agonists reduce blood sugar by increasing insulin secretion, decreasing glucagon release (thus downregulating further increases in blood sugar), and reducing insulin resistance. GLP-1 agonists also reduce appetite by directly stimulating the satiety center and slowing gastric emptying and GI motility. In addition to GLP-1 agonism, some medications in this family (notably tirzepatide) also agonize a second hormone, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, which can further induce insulin secretion as well as decrease stomach acid secretion, potentially delivering an even more substantial reduction in appetite and weight.

Routes of administration and FDA indications

Due to limited bioavailability, most GLP-1 agonists require subcutaneous (SC) injections (the sole exception is the Rybelsus brand of semaglutide, which comes in a daily pill form). Most are FDA-approved not specifically for weight loss but for patients with type 2 diabetes (defined as a hemoglobin A1C ≥6.5% or a fasting blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dL). Weight loss represents a secondary outcome for GLP-1 agonists FDA-approved for glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. The 2 current exceptions to this classification are the Wegovy brand of semaglutide (ie, dosing of 2.4 mg) and the Saxenda brand of liraglutide, both of which carry FDA indications for chronic weight management alone (when paired with dietary and lifestyle modification) in individuals who are obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes, or for persons who are overweight (BMI >27 kg/m2) and have ≥1 weight-related comorbid condition (eg, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia). Although patients at risk for diabetes (ie, prediabetes, defined as a hemoglobin A1C 5.7% to 6.4% or a fasting blood glucose level 100 to 125 mg/dL) were included in FDA registration trials of Saxenda or Wegovy, prediabetes is not an FDA indication for any GLP-1 agonist.

Data in weight loss

Most of the existing empirical data on weight loss with GLP-1 agonists come from studies of individuals who are overweight or obese, with or without type 2 diabetes, rather than from studies using these agents to counteract iatrogenic weight gain. In a retrospective cohort study of patients with type 2 diabetes, coadministration with serotonergic antidepressants (eg, citalopram/escitalopram) was associated with attenuation of the weight loss effects of GLP-1 agonists.4

Liraglutide currently is the sole GLP-1 agonist studied for treating SGA-associated weight gain. A 16-week randomized trial compared once-daily SC injected liraglutide vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia who incurred weight gain and prediabetes after taking olanzapine or clozapine.5 Significantly more patients taking liraglutide than placebo developed normal glucose tolerance (64% vs 16%), and body weight decreased by a mean of 5.3 kg.

Continue to: In studies of semaglutide...

In studies of semaglutide for overweight/obese patients with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, clinical trials of oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) found a mean weight loss over 26 weeks of -1.0 kg with dosing at 7 mg/d and -2.6 kg with dosing at 14 mg/d.6 A 68-week placebo-controlled trial of semaglutide (dosed at 2.4 mg SC weekly) for overweight/obese adults who did not have diabetes yielded a -15.3 kg weight loss (vs -2.6 kg with placebo); one-half of those who received semaglutide lost 15% of their initial body weight (Figure 1A and Figure 1B).7 Similar findings with semaglutide 2.4 mg SC weekly (Wegovy) were observed in overweight/obese adolescents, with 73% of participants losing ≥5% of their baseline weight.8 A comparative randomized trial in patients with type 2 diabetes also found modestly but significantly greater weight loss with oral semaglutide than with SC liraglutide.9

In a 72-week study of tirzepatide specifically for weight loss in nondiabetic patients who were overweight or obese, findings were especially dramatic (Figure 2A and Figure 2B).10 An overall 15% decrease in body weight was observed with 5 mg/week dosing alongside a 19.5% decrease in body weight with 10 mg/week dosing and a 20.9% weight reduction with 15 mg/week dosing.10 As noted in Figure 2B, the observed pattern of weight loss occurred along an exponential decay curve. Notably, a comparative study of tirzepatide vs once-weekly semaglutide (1 mg) in patients with type 2 diabetes11 found significantly greater dose-dependent weight loss with tirzepatide than semaglutide (-1.9 kg at 5 mg, -3.6 kg at 10 mg, and -5.5 kg at 15 mg)—although the somewhat low dosing of semaglutide may have limited its optimal possible weight loss benefit.

Tolerability

Adverse effects with GLP-1 agonists are mainly gastrointestinal (eg, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation)5-11 and generally transient. SC administration is performed in fatty tissue of the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm; site rotation is recommended to minimize injection site pain. All GLP-1 agonists carry manufacturers’ warning and precaution statements identifying the rare potential for acute pancreatitis, acute gall bladder disease, acute kidney injury, and hypoglycemia. Animal studies also have suggested an increased, dose-dependent risk for thyroid C-cell tumors with GLP-1 agonists; this has not been observed in human trials, although postmarketing pharmacovigilance reports have identified cases of medullary thyroid carcinoma in patients who took liraglutide. A manufacturer’s boxed warning indicates that a personal or family history of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid poses a contraindication for taking semaglutide, liraglutide, or tirzepatide.

Initial evidence prompts additional questions

GLP-1 agonists represent an emerging class of novel agents that can modulate glycemic dysregulation and overweight/obesity, often with dramatic results whose magnitude rivals the efficacy of bariatric surgery. Once-weekly formulations of semaglutide (Wegovy) and daily liraglutide (Saxenda) are FDA-approved for weight loss in patients who are overweight or obese while other existing formulations are approved solely for patients with type 2 diabetes, although it is likely that broader indications for weight loss (regardless of glycemic status) are forthcoming. Targeted use of GLP-1 agonists to counteract SGA-associated weight gain is supported by a handful of preliminary reports, with additional studies likely to come. Unanswered questions include:

- When should GLP-1 agonists be considered within a treatment algorithm for iatrogenic weight gain relative to other antidote strategies such as metformin or appetite-suppressing anticonvulsants?

- How effective might GLP-1 agonists be for iatrogenic weight gain from non-SGA psychotropic medications, such as serotonergic antidepressants?

- When and how can GLP-1 agonists be safely coprescribed with other nonincretin mimetic weight loss medications?

- When should psychiatrists prescribe GLP-1 agonists, or do so collaboratively with primary care physicians or endocrinologists, particularly in patients with metabolic syndrome?

Followers of the rapidly emerging literature in this area will likely find themselves best positioned to address these and other questions about optimal management of psychotropic-induced weight gain for the patients they treat.

Bottom Line

The use of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, a relatively new class of incretin mimetics, has been associated with profound and often dramatic weight loss and improvement of glycemic parameters in patients with obesity and glycemic dysregulation. Preliminary reports support the potential targeted use of GLP-1 agonists to counteract weight gain associated with second-generation antipsychotics.

Related Resources

- Singh F, Allen A, Ianni A. Managing metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(12):20-24,26. doi:10.12788/cp.0064

- Ard J, Fitch A, Fruh S, et al. Weight loss and maintenance related to the mechanism of action of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists. Adv Ther. 2021;38(6):2821- 2839. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01710-0

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Citalopram • Celexa

Clozapine • Clozaril

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Liraglutide • Victoza, Saxenda

Metformin • Glucophage

Naltrexone • ReVia

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine/samidorphan • Lybalvi

Phentermine • Ionamin

Semaglutide • Rybelsus, Ozempic, Wegovy

Tirzepatide • Mounjaro

Topiramate • Topamax

Zonisamide • Zonegran

Obesity and overweight, with or without metabolic dysregulation, pose vexing problems for many patients with mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorders. More than one-half of individuals with severe mental illnesses are obese or overweight,1 resulting from multiple factors that may include psychiatric symptoms (eg, anergia and hyperphagia), poor dietary choices, sedentary lifestyle, underlying inflammatory processes, medical comorbidities, and iatrogenic consequences of certain medications. Unfortunately, numerous psychotropic medications can increase weight and appetite due to a variety of mechanisms, including antihistaminergic effects, direct appetite-stimulating effects, and proclivities to cause insulin resistance. While individual agents can vary, a recent review identified an overall 2-fold increased risk for rapid, significant weight gain during treatment with antipsychotics as a class.2 In addition to lifestyle modifications (diet and exercise), many pharmacologic strategies have been proposed to counter iatrogenic weight gain, including appetite suppressants (eg, pro-dopaminergic agents such as phentermine, stimulants, and amantadine), pro-anorectant anticonvulsants (eg, topiramate or zonisamide), opioid receptor antagonists (eg, olanzapine/samidorphan or naltrexone) and oral hypoglycemics such as metformin. However, the magnitude of impact for most of these agents to reverse iatrogenic weight gain tends to be modest, particularly once significant weight gain (ie, ≥7% of initial body weight) has already occurred.

Pharmacologic strategies to modulate or enhance the effects of insulin hold particular importance for combatting psychotropic-associated weight gain. Insulin transports glucose from the intravascular space to end organs for fuel consumption; to varying degrees, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and some other psychotropic medications can cause insulin resistance. This in turn leads to excessive storage of underutilized glucose in the liver (glycogenesis), the potential for developing fatty liver (ie, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis), and conversion of excess carbohydrates to fatty acids and triglycerides, with subsequent storage in adipose tissue. Medications that can enhance the activity of insulin (so-called incretin mimetics) can help to overcome insulin resistance caused by SGAs (and potentially by other psychotropic medications) and essentially lead to weight loss through enhanced “fuel efficiency.”

Metformin, typically dosed up to 1,000 mg twice daily with meals, has increasingly become recognized as a first-line strategy to attenuate weight gain and glycemic dysregulation from SGAs via its ability to reduce insulin resistance. Yet meta-analyses have shown that although results are significantly better than placebo, overall long-term weight loss from metformin alone tends to be rather modest (<4 kg) and associated with a reduction in body mass index (BMI) of only approximately 1 point.3 Psychiatrists (and other clinicians who prescribe psychotropic medications that can cause weight gain or metabolic dysregulation) therefore need to become familiar with alternative or adjunctive weight loss options. The use of a relatively new class of incretin mimetics called glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists (Table) has been associated with profound and often dramatic weight loss and improvement of glycemic parameters in patients with obesity and glycemic dysregulation.

What are GLP-1 agonists?

GLP-1 is a hormone secreted by L cells in the intestinal mucosa in response to food. GLP-1 agonists reduce blood sugar by increasing insulin secretion, decreasing glucagon release (thus downregulating further increases in blood sugar), and reducing insulin resistance. GLP-1 agonists also reduce appetite by directly stimulating the satiety center and slowing gastric emptying and GI motility. In addition to GLP-1 agonism, some medications in this family (notably tirzepatide) also agonize a second hormone, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, which can further induce insulin secretion as well as decrease stomach acid secretion, potentially delivering an even more substantial reduction in appetite and weight.

Routes of administration and FDA indications

Due to limited bioavailability, most GLP-1 agonists require subcutaneous (SC) injections (the sole exception is the Rybelsus brand of semaglutide, which comes in a daily pill form). Most are FDA-approved not specifically for weight loss but for patients with type 2 diabetes (defined as a hemoglobin A1C ≥6.5% or a fasting blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dL). Weight loss represents a secondary outcome for GLP-1 agonists FDA-approved for glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. The 2 current exceptions to this classification are the Wegovy brand of semaglutide (ie, dosing of 2.4 mg) and the Saxenda brand of liraglutide, both of which carry FDA indications for chronic weight management alone (when paired with dietary and lifestyle modification) in individuals who are obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes, or for persons who are overweight (BMI >27 kg/m2) and have ≥1 weight-related comorbid condition (eg, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia). Although patients at risk for diabetes (ie, prediabetes, defined as a hemoglobin A1C 5.7% to 6.4% or a fasting blood glucose level 100 to 125 mg/dL) were included in FDA registration trials of Saxenda or Wegovy, prediabetes is not an FDA indication for any GLP-1 agonist.

Data in weight loss

Most of the existing empirical data on weight loss with GLP-1 agonists come from studies of individuals who are overweight or obese, with or without type 2 diabetes, rather than from studies using these agents to counteract iatrogenic weight gain. In a retrospective cohort study of patients with type 2 diabetes, coadministration with serotonergic antidepressants (eg, citalopram/escitalopram) was associated with attenuation of the weight loss effects of GLP-1 agonists.4

Liraglutide currently is the sole GLP-1 agonist studied for treating SGA-associated weight gain. A 16-week randomized trial compared once-daily SC injected liraglutide vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia who incurred weight gain and prediabetes after taking olanzapine or clozapine.5 Significantly more patients taking liraglutide than placebo developed normal glucose tolerance (64% vs 16%), and body weight decreased by a mean of 5.3 kg.

Continue to: In studies of semaglutide...

In studies of semaglutide for overweight/obese patients with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, clinical trials of oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) found a mean weight loss over 26 weeks of -1.0 kg with dosing at 7 mg/d and -2.6 kg with dosing at 14 mg/d.6 A 68-week placebo-controlled trial of semaglutide (dosed at 2.4 mg SC weekly) for overweight/obese adults who did not have diabetes yielded a -15.3 kg weight loss (vs -2.6 kg with placebo); one-half of those who received semaglutide lost 15% of their initial body weight (Figure 1A and Figure 1B).7 Similar findings with semaglutide 2.4 mg SC weekly (Wegovy) were observed in overweight/obese adolescents, with 73% of participants losing ≥5% of their baseline weight.8 A comparative randomized trial in patients with type 2 diabetes also found modestly but significantly greater weight loss with oral semaglutide than with SC liraglutide.9

In a 72-week study of tirzepatide specifically for weight loss in nondiabetic patients who were overweight or obese, findings were especially dramatic (Figure 2A and Figure 2B).10 An overall 15% decrease in body weight was observed with 5 mg/week dosing alongside a 19.5% decrease in body weight with 10 mg/week dosing and a 20.9% weight reduction with 15 mg/week dosing.10 As noted in Figure 2B, the observed pattern of weight loss occurred along an exponential decay curve. Notably, a comparative study of tirzepatide vs once-weekly semaglutide (1 mg) in patients with type 2 diabetes11 found significantly greater dose-dependent weight loss with tirzepatide than semaglutide (-1.9 kg at 5 mg, -3.6 kg at 10 mg, and -5.5 kg at 15 mg)—although the somewhat low dosing of semaglutide may have limited its optimal possible weight loss benefit.

Tolerability

Adverse effects with GLP-1 agonists are mainly gastrointestinal (eg, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation)5-11 and generally transient. SC administration is performed in fatty tissue of the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm; site rotation is recommended to minimize injection site pain. All GLP-1 agonists carry manufacturers’ warning and precaution statements identifying the rare potential for acute pancreatitis, acute gall bladder disease, acute kidney injury, and hypoglycemia. Animal studies also have suggested an increased, dose-dependent risk for thyroid C-cell tumors with GLP-1 agonists; this has not been observed in human trials, although postmarketing pharmacovigilance reports have identified cases of medullary thyroid carcinoma in patients who took liraglutide. A manufacturer’s boxed warning indicates that a personal or family history of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid poses a contraindication for taking semaglutide, liraglutide, or tirzepatide.

Initial evidence prompts additional questions

GLP-1 agonists represent an emerging class of novel agents that can modulate glycemic dysregulation and overweight/obesity, often with dramatic results whose magnitude rivals the efficacy of bariatric surgery. Once-weekly formulations of semaglutide (Wegovy) and daily liraglutide (Saxenda) are FDA-approved for weight loss in patients who are overweight or obese while other existing formulations are approved solely for patients with type 2 diabetes, although it is likely that broader indications for weight loss (regardless of glycemic status) are forthcoming. Targeted use of GLP-1 agonists to counteract SGA-associated weight gain is supported by a handful of preliminary reports, with additional studies likely to come. Unanswered questions include:

- When should GLP-1 agonists be considered within a treatment algorithm for iatrogenic weight gain relative to other antidote strategies such as metformin or appetite-suppressing anticonvulsants?

- How effective might GLP-1 agonists be for iatrogenic weight gain from non-SGA psychotropic medications, such as serotonergic antidepressants?

- When and how can GLP-1 agonists be safely coprescribed with other nonincretin mimetic weight loss medications?

- When should psychiatrists prescribe GLP-1 agonists, or do so collaboratively with primary care physicians or endocrinologists, particularly in patients with metabolic syndrome?

Followers of the rapidly emerging literature in this area will likely find themselves best positioned to address these and other questions about optimal management of psychotropic-induced weight gain for the patients they treat.

Bottom Line

The use of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, a relatively new class of incretin mimetics, has been associated with profound and often dramatic weight loss and improvement of glycemic parameters in patients with obesity and glycemic dysregulation. Preliminary reports support the potential targeted use of GLP-1 agonists to counteract weight gain associated with second-generation antipsychotics.

Related Resources

- Singh F, Allen A, Ianni A. Managing metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(12):20-24,26. doi:10.12788/cp.0064

- Ard J, Fitch A, Fruh S, et al. Weight loss and maintenance related to the mechanism of action of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists. Adv Ther. 2021;38(6):2821- 2839. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01710-0

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Citalopram • Celexa

Clozapine • Clozaril

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Liraglutide • Victoza, Saxenda

Metformin • Glucophage

Naltrexone • ReVia

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine/samidorphan • Lybalvi

Phentermine • Ionamin

Semaglutide • Rybelsus, Ozempic, Wegovy

Tirzepatide • Mounjaro

Topiramate • Topamax

Zonisamide • Zonegran

1. Afzal M, Siddiqi N, Ahmad B, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;25;12:769309.

2. Barton BB, Segger F, Fischer K, et al. Update on weight-gain caused by antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Safety. 2020;19(3):295-314.

3. de Silva AV, Suraweera C, Ratnatunga SS, et al. Metformin in prevention and treatment of antipsychotic induced weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):341.

4. Durell N, Franks R, Coon S, et al. Effects of antidepressants on glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist-related weight loss. J Pharm Technol. 2022;38(5):283-288.

5. Larsen JR, Vedtofte L, Jakobsen MSL, et al. Effect of liraglutide treatment on prediabetes and overweight or obesity in clozapine- or olanzapine-treated patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):719-728.

6. Aroda VR, Rosenstock J, Terauchi Y, et al. PIONEER 1: randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide monotherapy in comparison with placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(9):1724-1732.

7. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(11):989-1002.

8. Weghuber D, Barrett T, Barrientos-Pérez M, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adolescents with obesity. N Engl J Med. Published online November 2, 2022. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2208601.

9. Pratley R, Amod A, Hoff ST, et al. Oral semaglutide versus subcutaneous liraglutide and placebo in type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 4): a randomized, double-blind, phase 3a trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):39-50.

10. Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):205-216.

11. Frías JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, et al. Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):503-515.

1. Afzal M, Siddiqi N, Ahmad B, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;25;12:769309.

2. Barton BB, Segger F, Fischer K, et al. Update on weight-gain caused by antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Safety. 2020;19(3):295-314.

3. de Silva AV, Suraweera C, Ratnatunga SS, et al. Metformin in prevention and treatment of antipsychotic induced weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):341.

4. Durell N, Franks R, Coon S, et al. Effects of antidepressants on glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist-related weight loss. J Pharm Technol. 2022;38(5):283-288.

5. Larsen JR, Vedtofte L, Jakobsen MSL, et al. Effect of liraglutide treatment on prediabetes and overweight or obesity in clozapine- or olanzapine-treated patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):719-728.

6. Aroda VR, Rosenstock J, Terauchi Y, et al. PIONEER 1: randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide monotherapy in comparison with placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(9):1724-1732.

7. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(11):989-1002.

8. Weghuber D, Barrett T, Barrientos-Pérez M, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adolescents with obesity. N Engl J Med. Published online November 2, 2022. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2208601.

9. Pratley R, Amod A, Hoff ST, et al. Oral semaglutide versus subcutaneous liraglutide and placebo in type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 4): a randomized, double-blind, phase 3a trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):39-50.

10. Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):205-216.

11. Frías JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, et al. Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):503-515.

Managing excited catatonia: A suggested approach

Catatonia is often difficult to identify and treat. The excited catatonia subtype can be particularly challenging to diagnose because it can present with symptoms similar to those seen in mania or psychosis. In this article, we present 3 cases of excited catatonia that illustrate how to identify it, how to treat the catatonia as well as the underlying pathology, and factors to consider during this process to mitigate the risk of adverse outcomes. We also outline a treatment algorithm we used for the 3 cases. Although we describe using this approach for patients with excited catatonia, it is generalizable to other types of catatonia.

Many causes, varying presentations

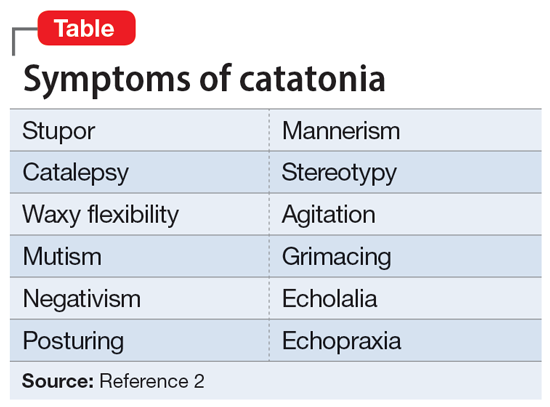

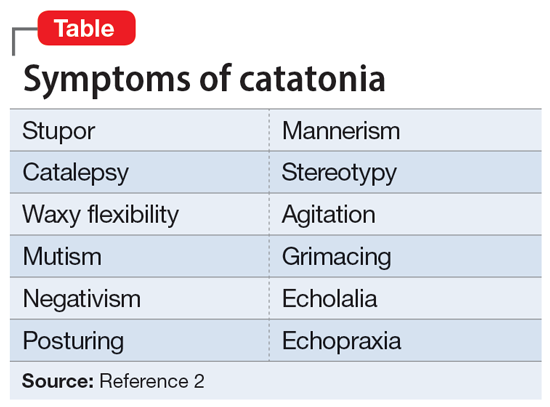

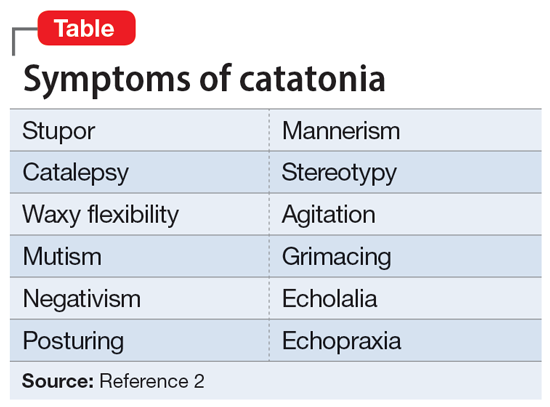

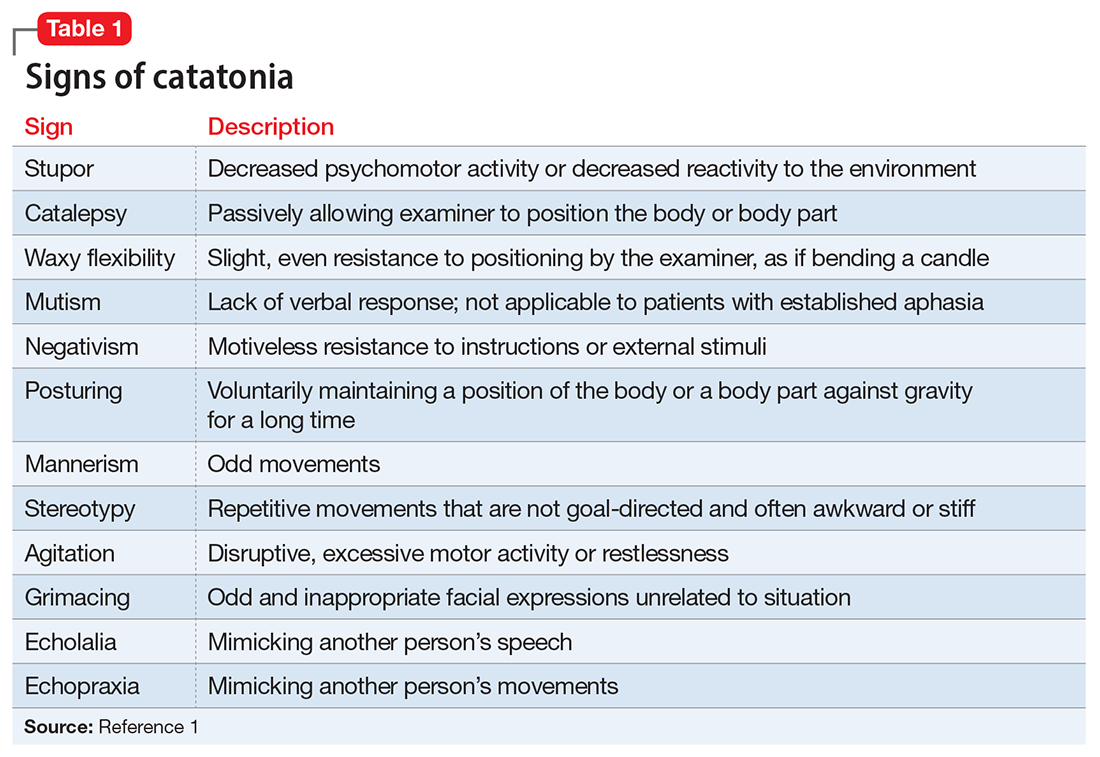

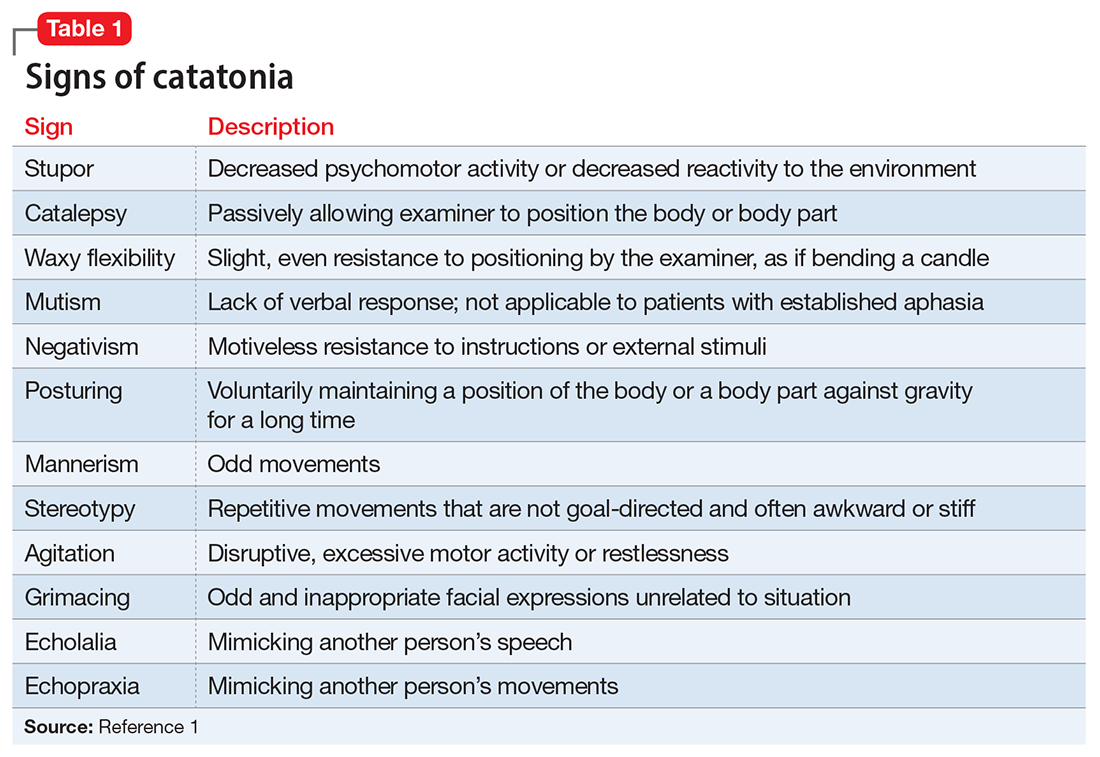

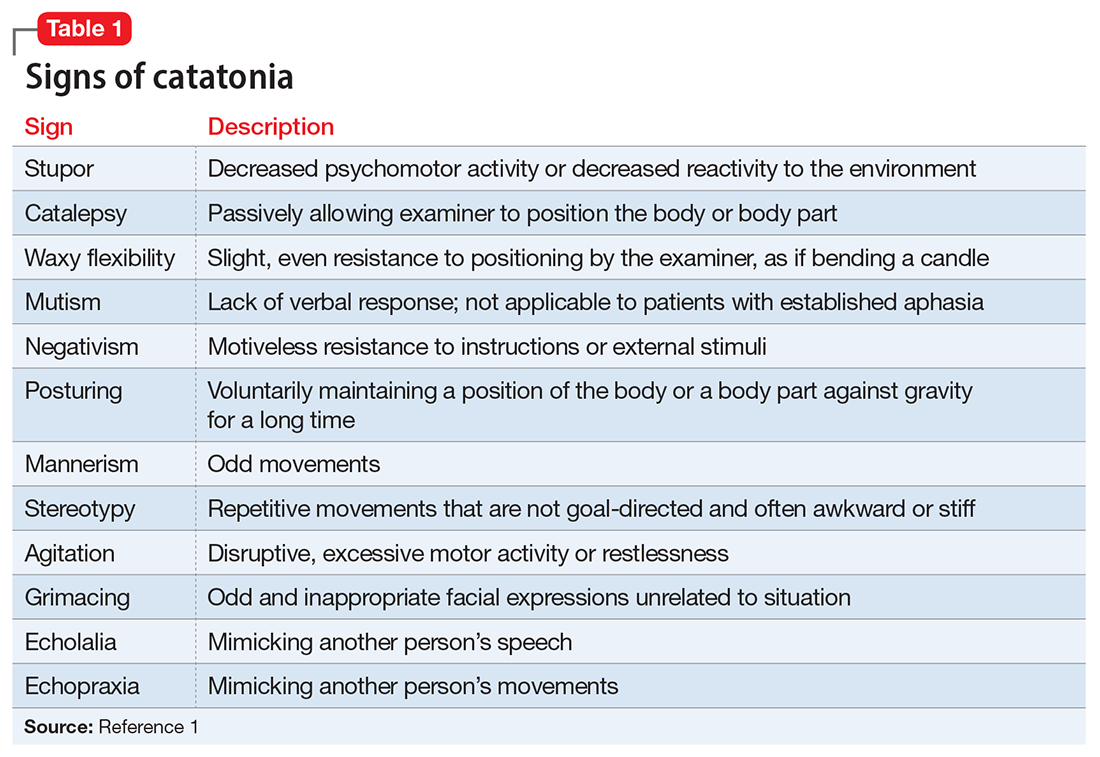

Catatonia is a psychomotor syndrome characterized by mutism, negativism, stereotypy, waxy flexibility, and other symptoms.1 It is defined by the presence of ≥3 of the 12 symptoms listed in the Table.2 Causes of catatonia include metabolic abnormalities, endocrine disorders, drug intoxication, neurodevelopmental disorders, medication adverse effects, psychosis, and mood disorders.1,3

A subtype of this syndrome, excited catatonia, can present with restlessness, agitation, emotional lability, poor sleep, and altered mental status in addition to the more typical symptoms.1,4 Because excited catatonia can resemble mania or psychosis, it is particularly challenging to identify the underlying disorder causing it and appropriate treatment. Fink et al4 discussed how clinicians have interpreted the different presentations of excited catatonia to gain insight into the underlying diagnosis. If the patient’s thought process appears disorganized, psychosis may be suspected.4 If the patient is delusional and grandiose, they may be manic, and when altered mental status dominates the presentation, delirium may be the culprit.4

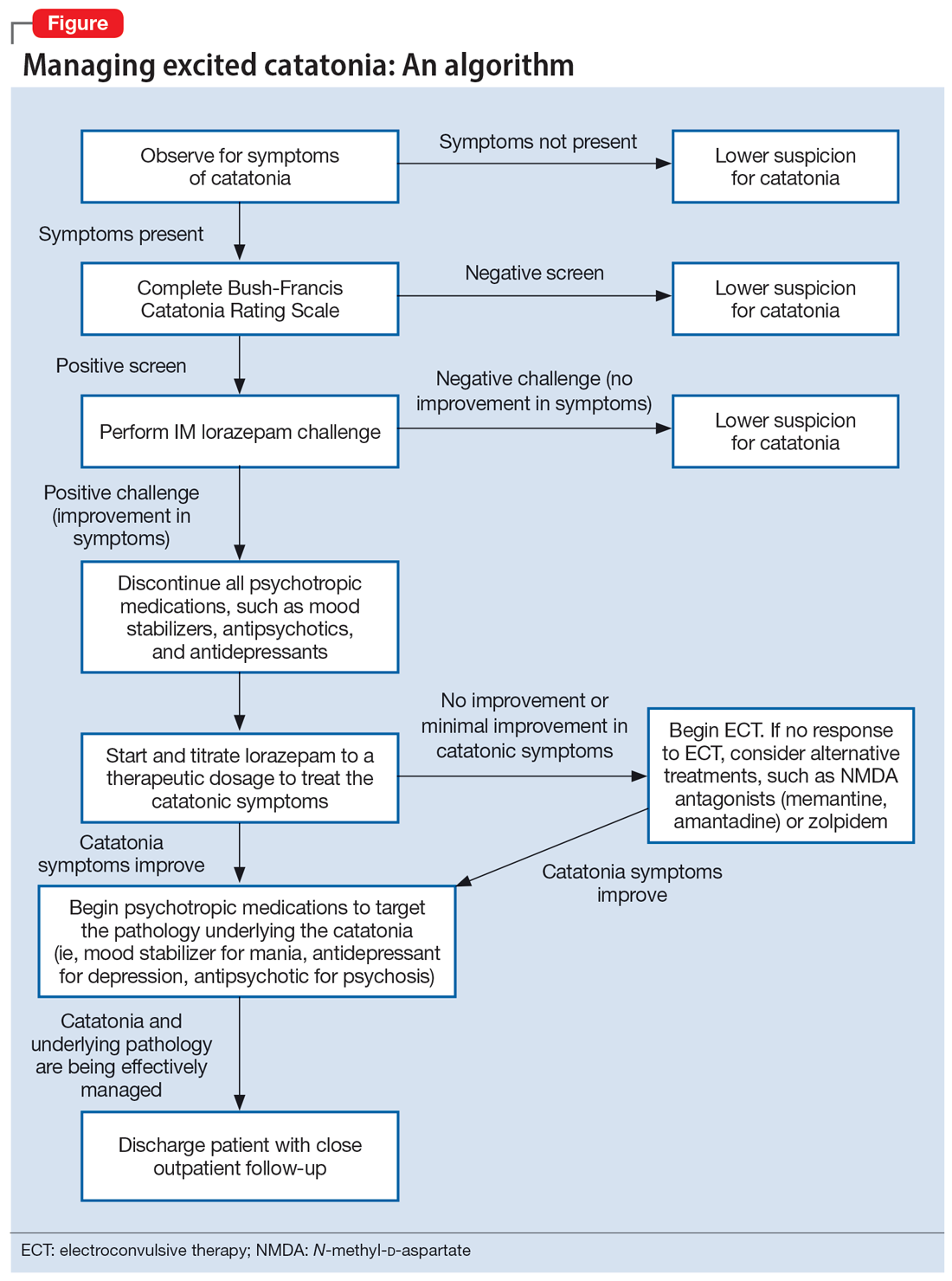

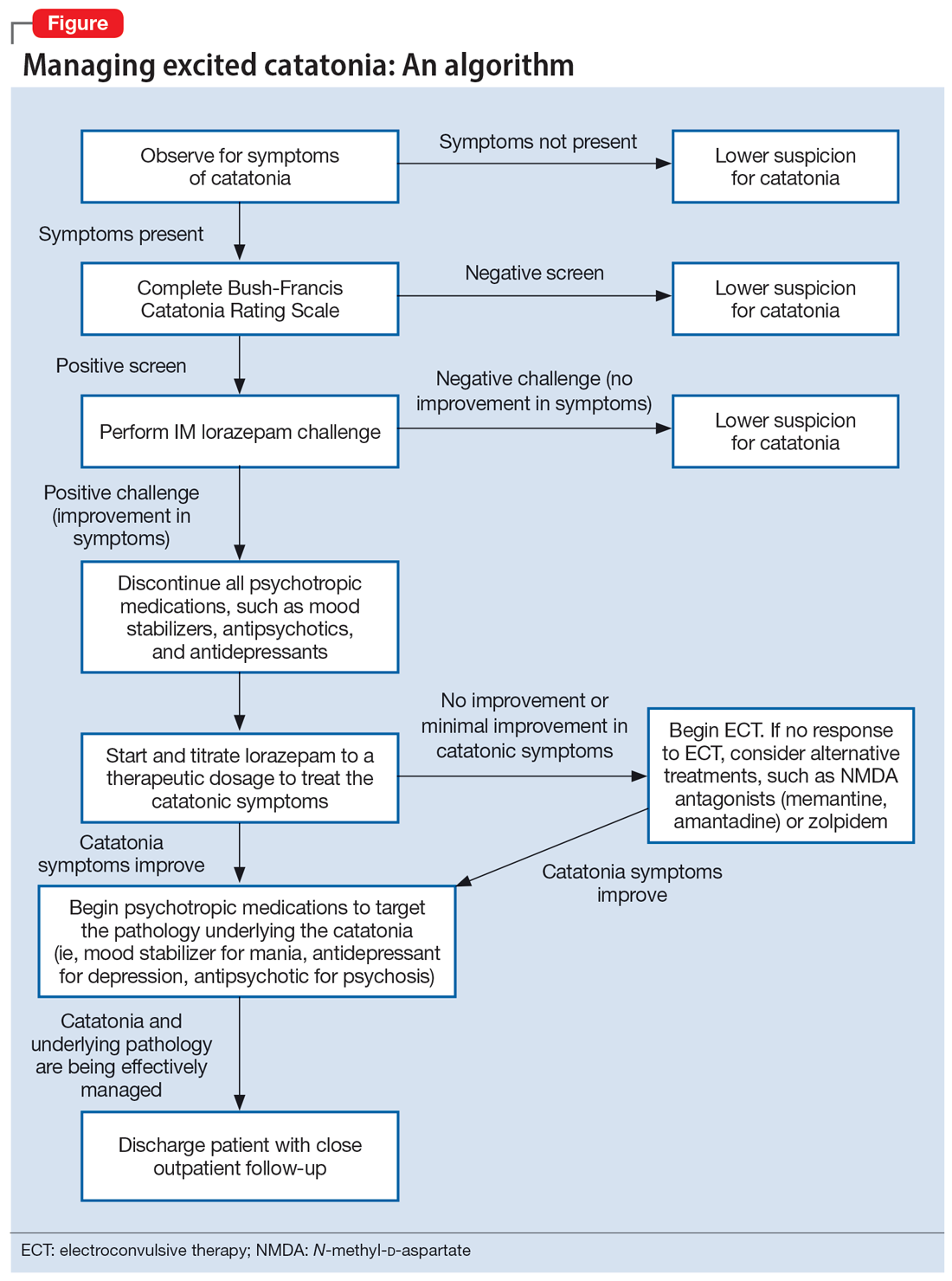

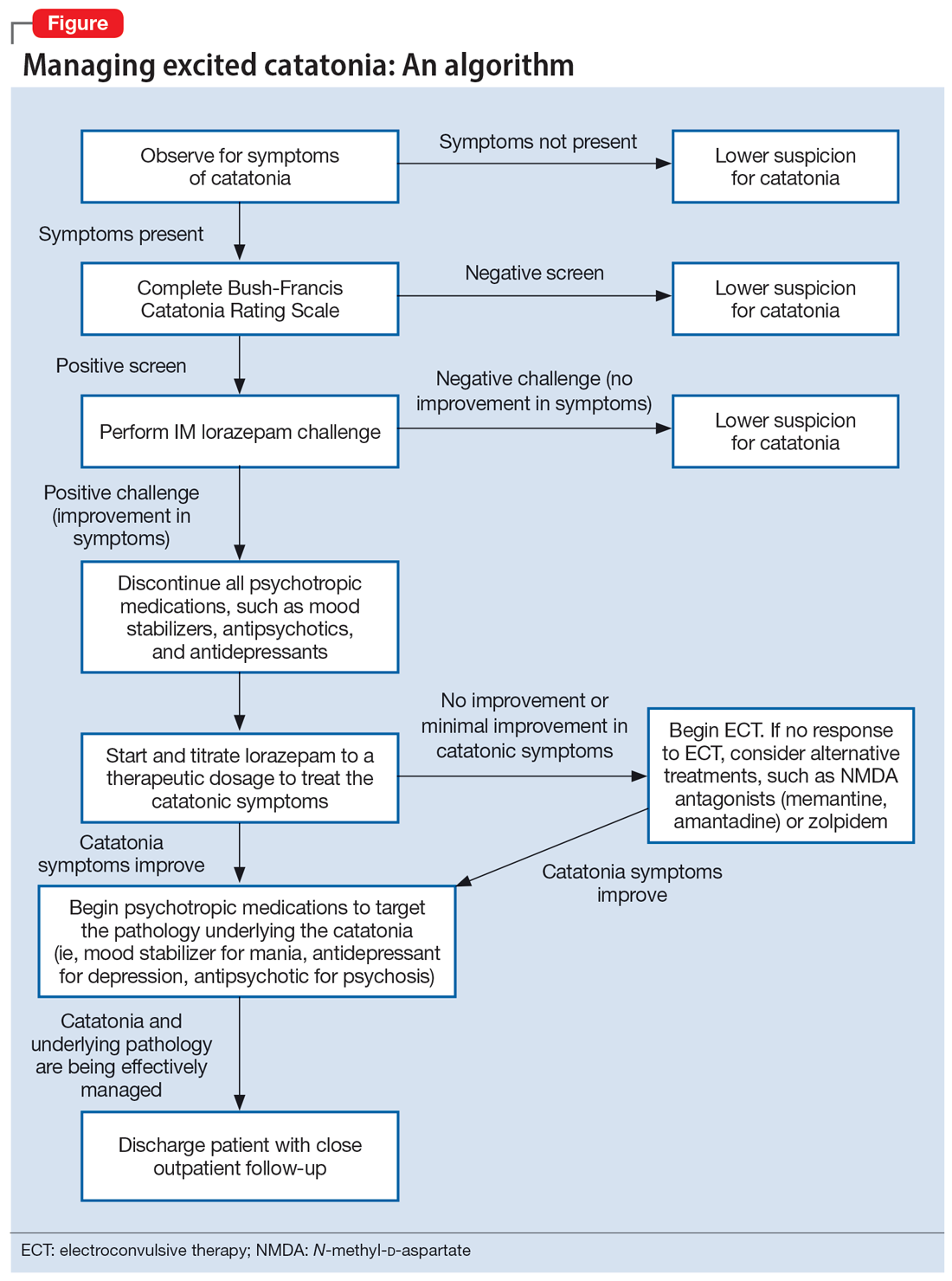

Regardless of the underlying cause, the first step is to treat the catatonia. Benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) are the most well validated treatments for catatonia and have been used to treat excited catatonia.1 Excited catatonia is often misdiagnosed and subsequently mistreated. In the following 3 cases, excited catatonia was successfully identified and treated using the same approach (Figure).

Case 1

Mr. A, age 27, has a history of bipolar I disorder. He was brought to the hospital by ambulance after being found to be yelling and acting belligerently, and he was admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit for manic decompensation due to medication nonadherence. He was started on divalproex sodium 500 mg twice a day for mood stabilization, risperidone 1 mg twice a day for adjunct mood stabilization and psychosis, and lorazepam 1 mg 3 times a day for agitation. Mr. A exhibited odd behavior; he would take off his clothes in the hallway, run around the unit, and randomly yell at staff or to himself. At other times, he would stay silent, repeat the same statements, or oddly posture in the hallway for minutes at a time. These behaviors were seen primarily in the hour or 2 preceding lorazepam administration and improved after he received lorazepam.

Mr. A’s treating team completed the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS), which yielded a positive catatonia screen of 7/14. As a result, divalproex sodium and risperidone were held, and lorazepam was increased to 2 mg twice a day.

After several days, Mr. A was no longer acting oddly and was able to speak more spontaneously; however, he began to exhibit overt signs of mania. He would speak rapidly and make grandiose claims about managing millions of dollars as the CEO of a famous company. Divalproex sodium was restarted at 500 mg twice a day and increased to 500 mg 3 times a day for mood stabilization. Mr. A continued to receive lorazepam 2 mg 3 times a day for catatonia, and risperidone was restarted at 1 mg twice a day to more effectively target his manic symptoms. Risperidone was increased to 2 mg twice a day. After this change, Mr. A’s grandiosity dissipated, his speech normalized, and his thought process became organized. He was discharged on lorazepam 2 mg 3 times a day, divalproex sodium 500 mg 3 times a day, and risperidone 2 mg twice a day. Mr. A’s length of stay (LOS) for this admission was 11 days.

Continue to: Case 2

Case 2

Mr. B, age 49, presented with irritability and odd posturing. He has a history of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type for which he was receiving a maintenance regimen of lithium 600 mg/d at bedtime and risperidone 2 mg/d at bedtime. He had multiple previous psychiatric admissions for catatonia. On this admission, Mr. B was irritable and difficult to redirect. He yelled at staff members and had a stiff gait. The BFCRS yielded a positive screening score of 3/14 and a severity score of 8/23. As a result, the treatment team conducted a lorazepam challenge.

After Mr. B received lorazepam 1 mg IM, his thought organization and irritability improved, which allowed him to have a coherent conversation with the interviewer. His gait stiffness also improved. His risperidone and lithium were held, and oral lorazepam 1 mg 3 times a day was started for catatonia. Lorazepam was gradually increased to 4 mg 3 times a day. Mr. B became euthymic and redirectable, and had an improved gait. However, he was also tangential and hyperverbal; these symptoms were indicative of the underlying mania that precipitated his catatonia.

Divalproex sodium extended release (ER) was started and increased to 1,500 mg/d at bedtime for mood stabilization. Lithium was restarted and increased to 300 mg twice a day for adjunct mood stabilization. Risperidone was not restarted. Toward the end of his admission, Mr. B was noted to be overly sedated, so the lorazepam dosage was decreased. He was discharged on lorazepam 2 mg 3 times a day, divalproex sodium ER 1,500 mg/d at bedtime, and lithium 300 mg twice a day. At discharge, Mr. B was calm and euthymic, with a linear thought process. His LOS was 25 days.

Case 3

Mr. C, age 62, presented to the emergency department (ED) because he had exhibited erratic behavior and had not slept for the past week. He has a history of bipolar I disorder, hypothyroidism, diabetes, and hypertension. For many years, he had been stable on divalproex sodium ER 2,500 mg/d at bedtime for mood stabilization and clozapine 100 mg/d at bedtime for adjunct mood stabilization and psychosis. In the ED, Mr. C was irritable, distractible, and tangential. On admission, he was speaking slowly with increased speech latency in response to questions, exhibiting stereotypy, repeating statements over and over, and walking very slowly.

The BFCRS yielded a positive screening score of 5/14 and a severity score of 10/23. Lorazepam 1 mg IM was administered. After 15 minutes, Mr. C’s speech, gait, and distractibility improved. As a result, clozapine and divalproex sodium were held, and he was started on oral lorazepam 1 mg 3 times a day. After several days, Mr. C was speaking fluently and no longer exhibiting stereotypy or having outbursts where he would make repetitive statements. However, he was tangential and irritable at times, which were signs of his underlying mania. Divalproex sodium ER was restarted at 250 mg/d at bedtime for mood stabilization and gradually increased to 2,500 mg/d at bedtime. Clozapine was also restarted at 25 mg/d at bedtime and gradually increased to 200 mg/d at bedtime. The lorazepam was gradually tapered and discontinued over the course of 3 weeks due to oversedation.

Continue to: At discharge...

At discharge, Mr. C was euthymic, calm, linear, and goal-directed. He was discharged on divalproex sodium ER 2,500 mg/d at bedtime and clozapine 200 mg/d at bedtime. His LOS for this admission was 22 days.

A stepwise approach can improve outcomes

The Figure outlines the method we used to manage excited catatonia in these 3 cases. Each of these patients exhibited signs of excited catatonia, but because those symptoms were nearly identical to those of mania, it was initially difficult to identify catatonia. Excited catatonia was suspected after more typical catatonic symptoms—such as a stiff gait, slowed speech, and stereotypy—were observed. The BFCRS was completed to get an objective measure of the likelihood that the patient was catatonic. In all 3 cases, the BFCRS resulted in a positive screen for catatonia. Following this, the patients described in Case 2 and Case 3 received a lorazepam challenge, which confirmed their catatonia. No lorazepam challenge was performed in Case 1 because the patient was already receiving lorazepam when the BFCRS was completed. Although most catatonic patients will respond to a lorazepam challenge, not all will. Therefore, clinicians should maintain some degree of suspicion for catatonia if a patient has a positive screen on the BFCRS but a negative lorazepam challenge.

In all 3 cases, after catatonia was confirmed, the patient’s psychotropic medications were discontinued. In all 3 cases, the antipsychotic was held to prevent progression to neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) or malignant catatonia. Rasmussen et al3 found that 3.6% of the catatonic patients in their sample who were treated with antipsychotics developed NMS. A review of prospective studies looking at patients treated with antipsychotics found the incidence of NMS was .07% to 1.8%.5 Because NMS is often clinically indistinguishable from malignant catatonia,4,6 this incidence of NMS may have represented an increased incidence in malignant catatonia.

In all 3 cases, the mood stabilizer was held to prevent it from complicating the clinical picture. Discontinuing the mood stabilizer and focusing on treating the catatonia before targeting the underlying mania increased the likelihood of differentiating the patient’s catatonic symptoms from manic symptoms. This resulted in more precise medication selection and titration by allowing us to identify the specific symptoms that were being targeted by each medication.

Oral lorazepam was prescribed to target catatonia in all 3 cases, and the dosage was gradually increased until symptoms began to resolve. As the catatonia resolved, the manic symptoms became more easily identifiable, and at this point a mood stabilizer was started and titrated to a therapeutic dose to target the mania. In Case 1 and Case 3, the antipsychotic was restarted to treat the mania more effectively. It was not restarted in Case 2 because the patient’s mania was effectively being managed by 2 mood stabilizers. The risks and benefits of starting an antipsychotic in a catatonic or recently catatonic patient should be carefully considered. In the 2 cases where the antipsychotic was restarted, the patients were closely monitored, and there were no signs of NMS or malignant catatonia.

Continue to: As discharge approached...

As discharge approached, the dosages of oral lorazepam were reevaluated. Catatonic patients can typically tolerate high doses of benzodiazepines without becoming overly sedated, but each patient has a different threshold at which the dosage causes oversedation. In all 3 patients, lorazepam was initially titrated to a dose that treated their catatonic symptoms without causing intolerable sedation. In Case 2 and Case 3, as the catatonia began to resolve, the patients became increasingly sedated on their existing lorazepam dosage, so it was decreased. Because the patient in Case 1 did not become overly sedated, his lorazepam dosage did not need to be reduced.

For 2 of these patients, our approach resulted in a shorter LOS compared to their previous hospitalizations. The LOS in Case 2 was 25 days; 5 years earlier, he had a 49-day LOS for mania and catatonia. During the past admission, the identification and treatment of the catatonia was delayed, which resulted in the patient requiring multiple transfers to the medical unit for unstable vital signs. The LOS in Case 3 was 22 days; 6 months prior to this admission, the patient had 2 psychiatric admissions that totaled 37 days. Although the patient’s presentation in the 2 previous admissions was similar to his presentation as described in Case 3, catatonia had not been identified or treated in either admission. Since his catatonia and mania were treated in Case 3, he has not required a readmission. The patient in Case 1 was previously hospitalized, but information about the LOS of these admissions was not available. These results suggest that early identification and treatment of catatonia via the approach we used can improve patient outcomes.

Bottom Line

Excited catatonia can be challenging to diagnose and treat because it can present with symptoms similar to those seen in mania or psychosis. We describe 3 cases in which we used a stepwise approach to optimize treatment and improve outcomes for patients with excited catatonia. This approach may work equally well for other catatonia subtypes.

Related Resources

- Dubovsky SL, Dubovsky AN. Catatonia: how to identify and treat it. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):16-26.

- Crouse EL, Joel B. Moran JB. Catatonia: recognition, management, and prevention of complications. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(12):45-49.

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Risperidone • Risperdal

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

1. Fink M, Taylor MA. The many varieties of catatonia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;251(Suppl 1):8-13.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:119-121.

3. Rasmussen SA, Mazurek MF, Rosebush PI. Catatonia: our current understanding of its diagnosis, treatment and pathophysiology. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(4):391-398.

4. Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: A Clinician’s Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. Cambridge University Press; 2003.

5. Adityanjee, Aderibigbe YA, Matthews T. Epidemiology of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1999;22(3):151-158.

6. Strawn JR, Keck PE Jr, Caroff SN. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):870-876.

Catatonia is often difficult to identify and treat. The excited catatonia subtype can be particularly challenging to diagnose because it can present with symptoms similar to those seen in mania or psychosis. In this article, we present 3 cases of excited catatonia that illustrate how to identify it, how to treat the catatonia as well as the underlying pathology, and factors to consider during this process to mitigate the risk of adverse outcomes. We also outline a treatment algorithm we used for the 3 cases. Although we describe using this approach for patients with excited catatonia, it is generalizable to other types of catatonia.

Many causes, varying presentations

Catatonia is a psychomotor syndrome characterized by mutism, negativism, stereotypy, waxy flexibility, and other symptoms.1 It is defined by the presence of ≥3 of the 12 symptoms listed in the Table.2 Causes of catatonia include metabolic abnormalities, endocrine disorders, drug intoxication, neurodevelopmental disorders, medication adverse effects, psychosis, and mood disorders.1,3

A subtype of this syndrome, excited catatonia, can present with restlessness, agitation, emotional lability, poor sleep, and altered mental status in addition to the more typical symptoms.1,4 Because excited catatonia can resemble mania or psychosis, it is particularly challenging to identify the underlying disorder causing it and appropriate treatment. Fink et al4 discussed how clinicians have interpreted the different presentations of excited catatonia to gain insight into the underlying diagnosis. If the patient’s thought process appears disorganized, psychosis may be suspected.4 If the patient is delusional and grandiose, they may be manic, and when altered mental status dominates the presentation, delirium may be the culprit.4

Regardless of the underlying cause, the first step is to treat the catatonia. Benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) are the most well validated treatments for catatonia and have been used to treat excited catatonia.1 Excited catatonia is often misdiagnosed and subsequently mistreated. In the following 3 cases, excited catatonia was successfully identified and treated using the same approach (Figure).

Case 1

Mr. A, age 27, has a history of bipolar I disorder. He was brought to the hospital by ambulance after being found to be yelling and acting belligerently, and he was admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit for manic decompensation due to medication nonadherence. He was started on divalproex sodium 500 mg twice a day for mood stabilization, risperidone 1 mg twice a day for adjunct mood stabilization and psychosis, and lorazepam 1 mg 3 times a day for agitation. Mr. A exhibited odd behavior; he would take off his clothes in the hallway, run around the unit, and randomly yell at staff or to himself. At other times, he would stay silent, repeat the same statements, or oddly posture in the hallway for minutes at a time. These behaviors were seen primarily in the hour or 2 preceding lorazepam administration and improved after he received lorazepam.

Mr. A’s treating team completed the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS), which yielded a positive catatonia screen of 7/14. As a result, divalproex sodium and risperidone were held, and lorazepam was increased to 2 mg twice a day.

After several days, Mr. A was no longer acting oddly and was able to speak more spontaneously; however, he began to exhibit overt signs of mania. He would speak rapidly and make grandiose claims about managing millions of dollars as the CEO of a famous company. Divalproex sodium was restarted at 500 mg twice a day and increased to 500 mg 3 times a day for mood stabilization. Mr. A continued to receive lorazepam 2 mg 3 times a day for catatonia, and risperidone was restarted at 1 mg twice a day to more effectively target his manic symptoms. Risperidone was increased to 2 mg twice a day. After this change, Mr. A’s grandiosity dissipated, his speech normalized, and his thought process became organized. He was discharged on lorazepam 2 mg 3 times a day, divalproex sodium 500 mg 3 times a day, and risperidone 2 mg twice a day. Mr. A’s length of stay (LOS) for this admission was 11 days.

Continue to: Case 2

Case 2

Mr. B, age 49, presented with irritability and odd posturing. He has a history of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type for which he was receiving a maintenance regimen of lithium 600 mg/d at bedtime and risperidone 2 mg/d at bedtime. He had multiple previous psychiatric admissions for catatonia. On this admission, Mr. B was irritable and difficult to redirect. He yelled at staff members and had a stiff gait. The BFCRS yielded a positive screening score of 3/14 and a severity score of 8/23. As a result, the treatment team conducted a lorazepam challenge.

After Mr. B received lorazepam 1 mg IM, his thought organization and irritability improved, which allowed him to have a coherent conversation with the interviewer. His gait stiffness also improved. His risperidone and lithium were held, and oral lorazepam 1 mg 3 times a day was started for catatonia. Lorazepam was gradually increased to 4 mg 3 times a day. Mr. B became euthymic and redirectable, and had an improved gait. However, he was also tangential and hyperverbal; these symptoms were indicative of the underlying mania that precipitated his catatonia.

Divalproex sodium extended release (ER) was started and increased to 1,500 mg/d at bedtime for mood stabilization. Lithium was restarted and increased to 300 mg twice a day for adjunct mood stabilization. Risperidone was not restarted. Toward the end of his admission, Mr. B was noted to be overly sedated, so the lorazepam dosage was decreased. He was discharged on lorazepam 2 mg 3 times a day, divalproex sodium ER 1,500 mg/d at bedtime, and lithium 300 mg twice a day. At discharge, Mr. B was calm and euthymic, with a linear thought process. His LOS was 25 days.

Case 3

Mr. C, age 62, presented to the emergency department (ED) because he had exhibited erratic behavior and had not slept for the past week. He has a history of bipolar I disorder, hypothyroidism, diabetes, and hypertension. For many years, he had been stable on divalproex sodium ER 2,500 mg/d at bedtime for mood stabilization and clozapine 100 mg/d at bedtime for adjunct mood stabilization and psychosis. In the ED, Mr. C was irritable, distractible, and tangential. On admission, he was speaking slowly with increased speech latency in response to questions, exhibiting stereotypy, repeating statements over and over, and walking very slowly.

The BFCRS yielded a positive screening score of 5/14 and a severity score of 10/23. Lorazepam 1 mg IM was administered. After 15 minutes, Mr. C’s speech, gait, and distractibility improved. As a result, clozapine and divalproex sodium were held, and he was started on oral lorazepam 1 mg 3 times a day. After several days, Mr. C was speaking fluently and no longer exhibiting stereotypy or having outbursts where he would make repetitive statements. However, he was tangential and irritable at times, which were signs of his underlying mania. Divalproex sodium ER was restarted at 250 mg/d at bedtime for mood stabilization and gradually increased to 2,500 mg/d at bedtime. Clozapine was also restarted at 25 mg/d at bedtime and gradually increased to 200 mg/d at bedtime. The lorazepam was gradually tapered and discontinued over the course of 3 weeks due to oversedation.

Continue to: At discharge...

At discharge, Mr. C was euthymic, calm, linear, and goal-directed. He was discharged on divalproex sodium ER 2,500 mg/d at bedtime and clozapine 200 mg/d at bedtime. His LOS for this admission was 22 days.

A stepwise approach can improve outcomes

The Figure outlines the method we used to manage excited catatonia in these 3 cases. Each of these patients exhibited signs of excited catatonia, but because those symptoms were nearly identical to those of mania, it was initially difficult to identify catatonia. Excited catatonia was suspected after more typical catatonic symptoms—such as a stiff gait, slowed speech, and stereotypy—were observed. The BFCRS was completed to get an objective measure of the likelihood that the patient was catatonic. In all 3 cases, the BFCRS resulted in a positive screen for catatonia. Following this, the patients described in Case 2 and Case 3 received a lorazepam challenge, which confirmed their catatonia. No lorazepam challenge was performed in Case 1 because the patient was already receiving lorazepam when the BFCRS was completed. Although most catatonic patients will respond to a lorazepam challenge, not all will. Therefore, clinicians should maintain some degree of suspicion for catatonia if a patient has a positive screen on the BFCRS but a negative lorazepam challenge.

In all 3 cases, after catatonia was confirmed, the patient’s psychotropic medications were discontinued. In all 3 cases, the antipsychotic was held to prevent progression to neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) or malignant catatonia. Rasmussen et al3 found that 3.6% of the catatonic patients in their sample who were treated with antipsychotics developed NMS. A review of prospective studies looking at patients treated with antipsychotics found the incidence of NMS was .07% to 1.8%.5 Because NMS is often clinically indistinguishable from malignant catatonia,4,6 this incidence of NMS may have represented an increased incidence in malignant catatonia.

In all 3 cases, the mood stabilizer was held to prevent it from complicating the clinical picture. Discontinuing the mood stabilizer and focusing on treating the catatonia before targeting the underlying mania increased the likelihood of differentiating the patient’s catatonic symptoms from manic symptoms. This resulted in more precise medication selection and titration by allowing us to identify the specific symptoms that were being targeted by each medication.

Oral lorazepam was prescribed to target catatonia in all 3 cases, and the dosage was gradually increased until symptoms began to resolve. As the catatonia resolved, the manic symptoms became more easily identifiable, and at this point a mood stabilizer was started and titrated to a therapeutic dose to target the mania. In Case 1 and Case 3, the antipsychotic was restarted to treat the mania more effectively. It was not restarted in Case 2 because the patient’s mania was effectively being managed by 2 mood stabilizers. The risks and benefits of starting an antipsychotic in a catatonic or recently catatonic patient should be carefully considered. In the 2 cases where the antipsychotic was restarted, the patients were closely monitored, and there were no signs of NMS or malignant catatonia.

Continue to: As discharge approached...

As discharge approached, the dosages of oral lorazepam were reevaluated. Catatonic patients can typically tolerate high doses of benzodiazepines without becoming overly sedated, but each patient has a different threshold at which the dosage causes oversedation. In all 3 patients, lorazepam was initially titrated to a dose that treated their catatonic symptoms without causing intolerable sedation. In Case 2 and Case 3, as the catatonia began to resolve, the patients became increasingly sedated on their existing lorazepam dosage, so it was decreased. Because the patient in Case 1 did not become overly sedated, his lorazepam dosage did not need to be reduced.

For 2 of these patients, our approach resulted in a shorter LOS compared to their previous hospitalizations. The LOS in Case 2 was 25 days; 5 years earlier, he had a 49-day LOS for mania and catatonia. During the past admission, the identification and treatment of the catatonia was delayed, which resulted in the patient requiring multiple transfers to the medical unit for unstable vital signs. The LOS in Case 3 was 22 days; 6 months prior to this admission, the patient had 2 psychiatric admissions that totaled 37 days. Although the patient’s presentation in the 2 previous admissions was similar to his presentation as described in Case 3, catatonia had not been identified or treated in either admission. Since his catatonia and mania were treated in Case 3, he has not required a readmission. The patient in Case 1 was previously hospitalized, but information about the LOS of these admissions was not available. These results suggest that early identification and treatment of catatonia via the approach we used can improve patient outcomes.

Bottom Line

Excited catatonia can be challenging to diagnose and treat because it can present with symptoms similar to those seen in mania or psychosis. We describe 3 cases in which we used a stepwise approach to optimize treatment and improve outcomes for patients with excited catatonia. This approach may work equally well for other catatonia subtypes.

Related Resources

- Dubovsky SL, Dubovsky AN. Catatonia: how to identify and treat it. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):16-26.

- Crouse EL, Joel B. Moran JB. Catatonia: recognition, management, and prevention of complications. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(12):45-49.

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Risperidone • Risperdal

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Catatonia is often difficult to identify and treat. The excited catatonia subtype can be particularly challenging to diagnose because it can present with symptoms similar to those seen in mania or psychosis. In this article, we present 3 cases of excited catatonia that illustrate how to identify it, how to treat the catatonia as well as the underlying pathology, and factors to consider during this process to mitigate the risk of adverse outcomes. We also outline a treatment algorithm we used for the 3 cases. Although we describe using this approach for patients with excited catatonia, it is generalizable to other types of catatonia.

Many causes, varying presentations

Catatonia is a psychomotor syndrome characterized by mutism, negativism, stereotypy, waxy flexibility, and other symptoms.1 It is defined by the presence of ≥3 of the 12 symptoms listed in the Table.2 Causes of catatonia include metabolic abnormalities, endocrine disorders, drug intoxication, neurodevelopmental disorders, medication adverse effects, psychosis, and mood disorders.1,3

A subtype of this syndrome, excited catatonia, can present with restlessness, agitation, emotional lability, poor sleep, and altered mental status in addition to the more typical symptoms.1,4 Because excited catatonia can resemble mania or psychosis, it is particularly challenging to identify the underlying disorder causing it and appropriate treatment. Fink et al4 discussed how clinicians have interpreted the different presentations of excited catatonia to gain insight into the underlying diagnosis. If the patient’s thought process appears disorganized, psychosis may be suspected.4 If the patient is delusional and grandiose, they may be manic, and when altered mental status dominates the presentation, delirium may be the culprit.4

Regardless of the underlying cause, the first step is to treat the catatonia. Benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) are the most well validated treatments for catatonia and have been used to treat excited catatonia.1 Excited catatonia is often misdiagnosed and subsequently mistreated. In the following 3 cases, excited catatonia was successfully identified and treated using the same approach (Figure).

Case 1

Mr. A, age 27, has a history of bipolar I disorder. He was brought to the hospital by ambulance after being found to be yelling and acting belligerently, and he was admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit for manic decompensation due to medication nonadherence. He was started on divalproex sodium 500 mg twice a day for mood stabilization, risperidone 1 mg twice a day for adjunct mood stabilization and psychosis, and lorazepam 1 mg 3 times a day for agitation. Mr. A exhibited odd behavior; he would take off his clothes in the hallway, run around the unit, and randomly yell at staff or to himself. At other times, he would stay silent, repeat the same statements, or oddly posture in the hallway for minutes at a time. These behaviors were seen primarily in the hour or 2 preceding lorazepam administration and improved after he received lorazepam.

Mr. A’s treating team completed the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS), which yielded a positive catatonia screen of 7/14. As a result, divalproex sodium and risperidone were held, and lorazepam was increased to 2 mg twice a day.

After several days, Mr. A was no longer acting oddly and was able to speak more spontaneously; however, he began to exhibit overt signs of mania. He would speak rapidly and make grandiose claims about managing millions of dollars as the CEO of a famous company. Divalproex sodium was restarted at 500 mg twice a day and increased to 500 mg 3 times a day for mood stabilization. Mr. A continued to receive lorazepam 2 mg 3 times a day for catatonia, and risperidone was restarted at 1 mg twice a day to more effectively target his manic symptoms. Risperidone was increased to 2 mg twice a day. After this change, Mr. A’s grandiosity dissipated, his speech normalized, and his thought process became organized. He was discharged on lorazepam 2 mg 3 times a day, divalproex sodium 500 mg 3 times a day, and risperidone 2 mg twice a day. Mr. A’s length of stay (LOS) for this admission was 11 days.

Continue to: Case 2

Case 2

Mr. B, age 49, presented with irritability and odd posturing. He has a history of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type for which he was receiving a maintenance regimen of lithium 600 mg/d at bedtime and risperidone 2 mg/d at bedtime. He had multiple previous psychiatric admissions for catatonia. On this admission, Mr. B was irritable and difficult to redirect. He yelled at staff members and had a stiff gait. The BFCRS yielded a positive screening score of 3/14 and a severity score of 8/23. As a result, the treatment team conducted a lorazepam challenge.

After Mr. B received lorazepam 1 mg IM, his thought organization and irritability improved, which allowed him to have a coherent conversation with the interviewer. His gait stiffness also improved. His risperidone and lithium were held, and oral lorazepam 1 mg 3 times a day was started for catatonia. Lorazepam was gradually increased to 4 mg 3 times a day. Mr. B became euthymic and redirectable, and had an improved gait. However, he was also tangential and hyperverbal; these symptoms were indicative of the underlying mania that precipitated his catatonia.

Divalproex sodium extended release (ER) was started and increased to 1,500 mg/d at bedtime for mood stabilization. Lithium was restarted and increased to 300 mg twice a day for adjunct mood stabilization. Risperidone was not restarted. Toward the end of his admission, Mr. B was noted to be overly sedated, so the lorazepam dosage was decreased. He was discharged on lorazepam 2 mg 3 times a day, divalproex sodium ER 1,500 mg/d at bedtime, and lithium 300 mg twice a day. At discharge, Mr. B was calm and euthymic, with a linear thought process. His LOS was 25 days.

Case 3