User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Psychotropic medications for chronic pain

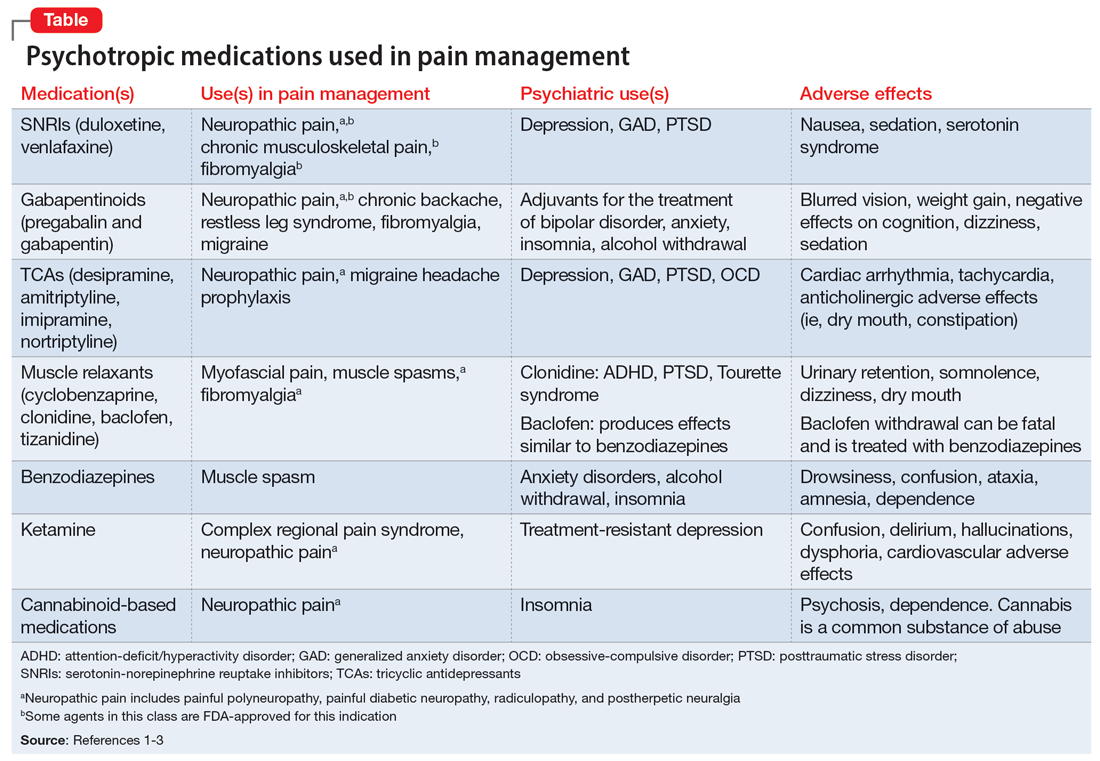

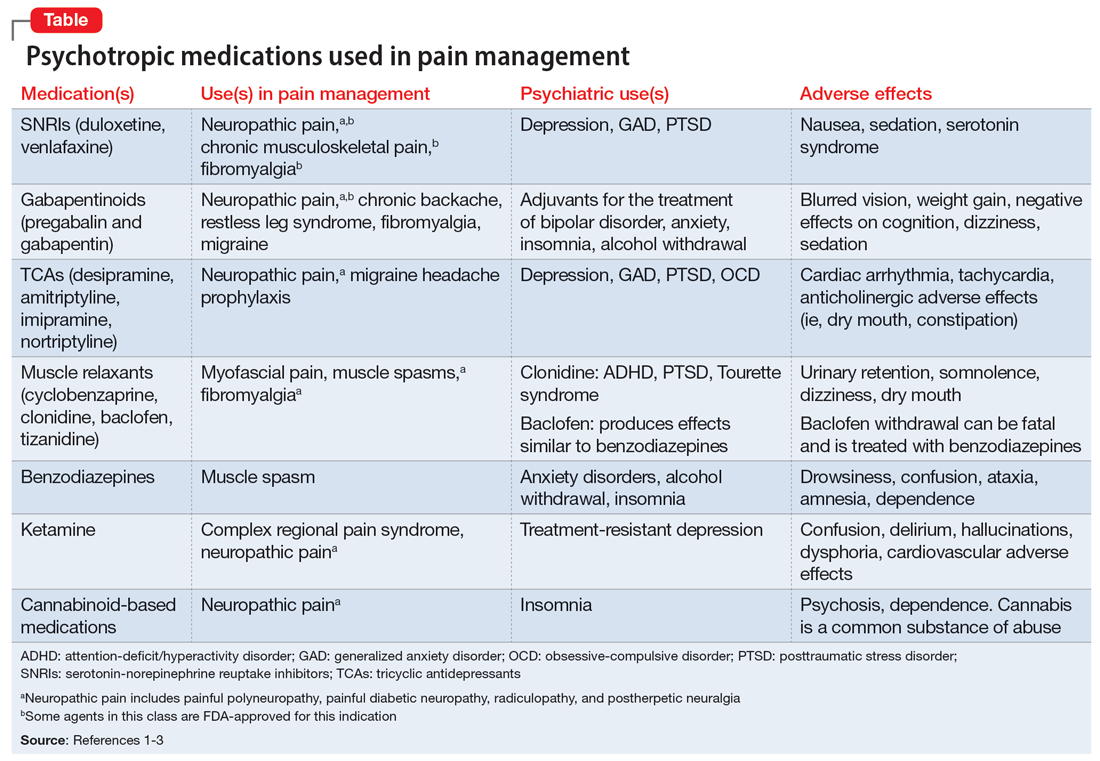

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

The light at the end of the tunnel: Reflecting on a 7-year training journey

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8

2. Wright Jr. JR, Schachar NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E13-E19. doi:10.1503/cjs.003319

3. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-565. doi:10.1080/01421590701477449

4. Liu AC, Liu M, Dannaway J, et al. Are Australian medical students being taught to teach? Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):330-335. doi:10.1111/tct.12591

5. Vasquez MJ, Bingham RP, Barnett JE. Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):653-665. doi:10.1002/jclp.20478

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8

2. Wright Jr. JR, Schachar NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E13-E19. doi:10.1503/cjs.003319

3. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-565. doi:10.1080/01421590701477449

4. Liu AC, Liu M, Dannaway J, et al. Are Australian medical students being taught to teach? Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):330-335. doi:10.1111/tct.12591

5. Vasquez MJ, Bingham RP, Barnett JE. Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):653-665. doi:10.1002/jclp.20478

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8

2. Wright Jr. JR, Schachar NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E13-E19. doi:10.1503/cjs.003319

3. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-565. doi:10.1080/01421590701477449

4. Liu AC, Liu M, Dannaway J, et al. Are Australian medical students being taught to teach? Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):330-335. doi:10.1111/tct.12591

5. Vasquez MJ, Bingham RP, Barnett JE. Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):653-665. doi:10.1002/jclp.20478

Lamotrigine for bipolar depression?

In reading Dr. Nasrallah's August 2022 editorial (“Reversing depression: A plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms,”

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thanks for your message. Lamotrigine is not FDA-approved for bipolar or unipolar depression, either as monotherapy or as an adjunctive therapy. It has never been approved for mania, either (no efficacy at all). Its only FDA-approved psychiatric indication is maintenance therapy after a patient with bipolar I disorder emerges from mania with the help of one of the antimanic drugs. Yet many clinicians may perceive lamotrigine as useful for bipolar depression because more than 20 years ago the manufacturer sponsored several small studies (not FDA trials). Two studies that showed efficacy were published, but 4 other studies that failed to show efficacy were not published. As a result, many clinicians got the false impression that lamotrigine is an effective antidepressant. I hope this explains why lamotrigine was not included in the list of antidepressants in my editorial.

In reading Dr. Nasrallah's August 2022 editorial (“Reversing depression: A plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms,”

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thanks for your message. Lamotrigine is not FDA-approved for bipolar or unipolar depression, either as monotherapy or as an adjunctive therapy. It has never been approved for mania, either (no efficacy at all). Its only FDA-approved psychiatric indication is maintenance therapy after a patient with bipolar I disorder emerges from mania with the help of one of the antimanic drugs. Yet many clinicians may perceive lamotrigine as useful for bipolar depression because more than 20 years ago the manufacturer sponsored several small studies (not FDA trials). Two studies that showed efficacy were published, but 4 other studies that failed to show efficacy were not published. As a result, many clinicians got the false impression that lamotrigine is an effective antidepressant. I hope this explains why lamotrigine was not included in the list of antidepressants in my editorial.

In reading Dr. Nasrallah's August 2022 editorial (“Reversing depression: A plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms,”

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thanks for your message. Lamotrigine is not FDA-approved for bipolar or unipolar depression, either as monotherapy or as an adjunctive therapy. It has never been approved for mania, either (no efficacy at all). Its only FDA-approved psychiatric indication is maintenance therapy after a patient with bipolar I disorder emerges from mania with the help of one of the antimanic drugs. Yet many clinicians may perceive lamotrigine as useful for bipolar depression because more than 20 years ago the manufacturer sponsored several small studies (not FDA trials). Two studies that showed efficacy were published, but 4 other studies that failed to show efficacy were not published. As a result, many clinicians got the false impression that lamotrigine is an effective antidepressant. I hope this explains why lamotrigine was not included in the list of antidepressants in my editorial.

A gender primer for psychiatrists

Psychiatrists have a long tradition of supporting LGBTQAI+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, asexual, intersex, and others) persons. In professional and public settings, we are educators, role models, and advocates for self-expression and personal empowerment. By better educating ourselves on the topic of gender and its variations, we can become champions of gender-affirming care.

Sex vs gender

A person’s sex is assigned at birth based on their physiological characteristics, including their genitalia and chromosome composition. Male, female, and intersex are a few recognized sexes. Gender or gender identity describe one’s innermost perception of self as a man, a woman, a variation of both, or neither, that may not always be visible to others. When sex and gender identity align, this is known as cisgender.1

Gender identity

Gender identity is best described as a spectrum rather than a binary. Terms that fall under a gender binary include man, woman, trans man, and trans woman. A nonbinary gender identity is one outside the traditional binary of men or women. Being transgender simply means having a gender identity different than the sex assigned at birth. This includes persons whose gender identities cross the gender spectrum, such as trans men or trans women, and those who fall anywhere outside or in between genders. In this way, nonbinary persons are transgender.1

The nonbinary spectrum

The term nonbinary encompasses many gender-nonconforming identities, such as agender, bigender, demigender, genderfluid, genderqueer, intergender, or pangender. Agender people have little connection to gender. Bigender individuals identify as 2 separate genders. Demigender persons feel a partial connection to a gender. Genderfluid individuals have a gender experience that is fluid and can change over time. Genderqueer people have a gender identity that falls in between or outside the binary. Intergender people have a gender identity between genders or identify as a combination of genders. Pangender people identify with a combination of genders. Note that patients may use some of these terms interchangeably or ascribe to them different meanings.2 As the language around gender continues to evolve, psychiatrists should ask patients from a place of nonjudgmental curiosity what gender terms they use, how they define them, and what their gender means to them.

Gender expression and transitioning

Transitioning is what a transgender person does to align their gender identity and expression.3 Gender expression is the external manifestation of gender, including names, pronouns, clothing, haircuts, behaviors, voice, body characteristics, and more.1 Transgender individuals can transition using a combination of social (name, pronouns, dress), legal (changing sex on legal documents, name change), or medical (surgeries, hormone therapies, puberty blockade) means. Transitions often help ease gender dysphoria, which is the clinically significant distress a person experiences when their sex assigned at birth does not align with their gender identity.3 Note that not all transgender persons choose to change their gender expression, and not all transgender individuals experience gender dysphoria. In this case, the proper medical term is gender incongruence, which is simply when someone’s gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth.4

Names and pronouns

For many transgender persons, names and pronouns are an important part of their gender transition and expression.2 Most of us have gotten into the habit of assuming pronouns because of socially established gender roles. This assumes that a person’s physical appearance matches their gender identity, which is not always the case.1 To be more affirming, psychiatrists and other health care professionals should try to break the habit of assuming pronouns. Often, an easy way to learn someone’s pronouns is to introduce yourself with yours. For example, “I am Dr. Agapoff. I use they/them/theirs pronouns. It is nice to meet you.” This creates a safe and open space for the other person to share their gender identity if they choose.

Why it’s important

One does not have to be a gender specialist to deliver gender-affirming care. As psychiatrists, having a basic understanding of the differences between sex, gender identity, and gender expression can help us build rapport and support our patients who are transgender. Based on the many kinds of gender identity and expression, judging someone’s gender based solely upon physical appearance is misguided at best and harmful at worst. Even people who are cisgender have many kinds of gender expression. For this reason, psychiatrists should approach gender with the same openness and curiosity as sexual orientation or other important considerations of emotional and physical health. Gender-informed care starts with us.

1. LGBTQIA Resource Center Glossary. UC Davis LGBTQIA Resource Center. Accessed July 19, 2022. https://lgbtqia.ucdavis.edu/educated/glossary

2. Richards C, Bouman WP, Seal L, et al. Non-binary or genderqueer genders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):95-102. doi:10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446

3. Understanding transitions. TransFamilies.Org. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://transfamilies.org/understanding-transitions/

4. Claahsen-van der Grinten H, Verhaak C, Steensma T, et al. Gender incongruence and gender dysphoria in childhood and adolescence—current insights in diagnostics, management, and follow-up. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180(5):1349-1357.

Psychiatrists have a long tradition of supporting LGBTQAI+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, asexual, intersex, and others) persons. In professional and public settings, we are educators, role models, and advocates for self-expression and personal empowerment. By better educating ourselves on the topic of gender and its variations, we can become champions of gender-affirming care.

Sex vs gender

A person’s sex is assigned at birth based on their physiological characteristics, including their genitalia and chromosome composition. Male, female, and intersex are a few recognized sexes. Gender or gender identity describe one’s innermost perception of self as a man, a woman, a variation of both, or neither, that may not always be visible to others. When sex and gender identity align, this is known as cisgender.1

Gender identity

Gender identity is best described as a spectrum rather than a binary. Terms that fall under a gender binary include man, woman, trans man, and trans woman. A nonbinary gender identity is one outside the traditional binary of men or women. Being transgender simply means having a gender identity different than the sex assigned at birth. This includes persons whose gender identities cross the gender spectrum, such as trans men or trans women, and those who fall anywhere outside or in between genders. In this way, nonbinary persons are transgender.1

The nonbinary spectrum

The term nonbinary encompasses many gender-nonconforming identities, such as agender, bigender, demigender, genderfluid, genderqueer, intergender, or pangender. Agender people have little connection to gender. Bigender individuals identify as 2 separate genders. Demigender persons feel a partial connection to a gender. Genderfluid individuals have a gender experience that is fluid and can change over time. Genderqueer people have a gender identity that falls in between or outside the binary. Intergender people have a gender identity between genders or identify as a combination of genders. Pangender people identify with a combination of genders. Note that patients may use some of these terms interchangeably or ascribe to them different meanings.2 As the language around gender continues to evolve, psychiatrists should ask patients from a place of nonjudgmental curiosity what gender terms they use, how they define them, and what their gender means to them.

Gender expression and transitioning

Transitioning is what a transgender person does to align their gender identity and expression.3 Gender expression is the external manifestation of gender, including names, pronouns, clothing, haircuts, behaviors, voice, body characteristics, and more.1 Transgender individuals can transition using a combination of social (name, pronouns, dress), legal (changing sex on legal documents, name change), or medical (surgeries, hormone therapies, puberty blockade) means. Transitions often help ease gender dysphoria, which is the clinically significant distress a person experiences when their sex assigned at birth does not align with their gender identity.3 Note that not all transgender persons choose to change their gender expression, and not all transgender individuals experience gender dysphoria. In this case, the proper medical term is gender incongruence, which is simply when someone’s gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth.4

Names and pronouns

For many transgender persons, names and pronouns are an important part of their gender transition and expression.2 Most of us have gotten into the habit of assuming pronouns because of socially established gender roles. This assumes that a person’s physical appearance matches their gender identity, which is not always the case.1 To be more affirming, psychiatrists and other health care professionals should try to break the habit of assuming pronouns. Often, an easy way to learn someone’s pronouns is to introduce yourself with yours. For example, “I am Dr. Agapoff. I use they/them/theirs pronouns. It is nice to meet you.” This creates a safe and open space for the other person to share their gender identity if they choose.

Why it’s important

One does not have to be a gender specialist to deliver gender-affirming care. As psychiatrists, having a basic understanding of the differences between sex, gender identity, and gender expression can help us build rapport and support our patients who are transgender. Based on the many kinds of gender identity and expression, judging someone’s gender based solely upon physical appearance is misguided at best and harmful at worst. Even people who are cisgender have many kinds of gender expression. For this reason, psychiatrists should approach gender with the same openness and curiosity as sexual orientation or other important considerations of emotional and physical health. Gender-informed care starts with us.

Psychiatrists have a long tradition of supporting LGBTQAI+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, asexual, intersex, and others) persons. In professional and public settings, we are educators, role models, and advocates for self-expression and personal empowerment. By better educating ourselves on the topic of gender and its variations, we can become champions of gender-affirming care.

Sex vs gender

A person’s sex is assigned at birth based on their physiological characteristics, including their genitalia and chromosome composition. Male, female, and intersex are a few recognized sexes. Gender or gender identity describe one’s innermost perception of self as a man, a woman, a variation of both, or neither, that may not always be visible to others. When sex and gender identity align, this is known as cisgender.1

Gender identity

Gender identity is best described as a spectrum rather than a binary. Terms that fall under a gender binary include man, woman, trans man, and trans woman. A nonbinary gender identity is one outside the traditional binary of men or women. Being transgender simply means having a gender identity different than the sex assigned at birth. This includes persons whose gender identities cross the gender spectrum, such as trans men or trans women, and those who fall anywhere outside or in between genders. In this way, nonbinary persons are transgender.1

The nonbinary spectrum

The term nonbinary encompasses many gender-nonconforming identities, such as agender, bigender, demigender, genderfluid, genderqueer, intergender, or pangender. Agender people have little connection to gender. Bigender individuals identify as 2 separate genders. Demigender persons feel a partial connection to a gender. Genderfluid individuals have a gender experience that is fluid and can change over time. Genderqueer people have a gender identity that falls in between or outside the binary. Intergender people have a gender identity between genders or identify as a combination of genders. Pangender people identify with a combination of genders. Note that patients may use some of these terms interchangeably or ascribe to them different meanings.2 As the language around gender continues to evolve, psychiatrists should ask patients from a place of nonjudgmental curiosity what gender terms they use, how they define them, and what their gender means to them.

Gender expression and transitioning

Transitioning is what a transgender person does to align their gender identity and expression.3 Gender expression is the external manifestation of gender, including names, pronouns, clothing, haircuts, behaviors, voice, body characteristics, and more.1 Transgender individuals can transition using a combination of social (name, pronouns, dress), legal (changing sex on legal documents, name change), or medical (surgeries, hormone therapies, puberty blockade) means. Transitions often help ease gender dysphoria, which is the clinically significant distress a person experiences when their sex assigned at birth does not align with their gender identity.3 Note that not all transgender persons choose to change their gender expression, and not all transgender individuals experience gender dysphoria. In this case, the proper medical term is gender incongruence, which is simply when someone’s gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth.4

Names and pronouns

For many transgender persons, names and pronouns are an important part of their gender transition and expression.2 Most of us have gotten into the habit of assuming pronouns because of socially established gender roles. This assumes that a person’s physical appearance matches their gender identity, which is not always the case.1 To be more affirming, psychiatrists and other health care professionals should try to break the habit of assuming pronouns. Often, an easy way to learn someone’s pronouns is to introduce yourself with yours. For example, “I am Dr. Agapoff. I use they/them/theirs pronouns. It is nice to meet you.” This creates a safe and open space for the other person to share their gender identity if they choose.

Why it’s important

One does not have to be a gender specialist to deliver gender-affirming care. As psychiatrists, having a basic understanding of the differences between sex, gender identity, and gender expression can help us build rapport and support our patients who are transgender. Based on the many kinds of gender identity and expression, judging someone’s gender based solely upon physical appearance is misguided at best and harmful at worst. Even people who are cisgender have many kinds of gender expression. For this reason, psychiatrists should approach gender with the same openness and curiosity as sexual orientation or other important considerations of emotional and physical health. Gender-informed care starts with us.

1. LGBTQIA Resource Center Glossary. UC Davis LGBTQIA Resource Center. Accessed July 19, 2022. https://lgbtqia.ucdavis.edu/educated/glossary

2. Richards C, Bouman WP, Seal L, et al. Non-binary or genderqueer genders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):95-102. doi:10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446

3. Understanding transitions. TransFamilies.Org. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://transfamilies.org/understanding-transitions/

4. Claahsen-van der Grinten H, Verhaak C, Steensma T, et al. Gender incongruence and gender dysphoria in childhood and adolescence—current insights in diagnostics, management, and follow-up. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180(5):1349-1357.

1. LGBTQIA Resource Center Glossary. UC Davis LGBTQIA Resource Center. Accessed July 19, 2022. https://lgbtqia.ucdavis.edu/educated/glossary

2. Richards C, Bouman WP, Seal L, et al. Non-binary or genderqueer genders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):95-102. doi:10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446

3. Understanding transitions. TransFamilies.Org. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://transfamilies.org/understanding-transitions/

4. Claahsen-van der Grinten H, Verhaak C, Steensma T, et al. Gender incongruence and gender dysphoria in childhood and adolescence—current insights in diagnostics, management, and follow-up. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180(5):1349-1357.

Positive psychiatry: An introduction

Historically, psychology and psychiatry have mostly focused on negative emotions and pathological states. However, during the last few decades, new developments in both disciplines have created novel vistas for a more comprehensive understanding of human behavior.1,2 These developments have taken on the names of positive psychology and positive psychiatry, respectively. Positive psychiatry is the science and practice of psychiatry that focuses on psycho-bio-social study and promotion of well-being and health through enhancement of positive psychosocial factors (eg, resilience, optimism, wisdom, social support) in people with illnesses or disabilities as well as in the community at large.3 This new perspective is aimed at enhancing and enriching psychiatric practice and research rather than replacing our stated aim of providing reliable and valid diagnostic categories along with effective therapeutic interventions.

In this issue of

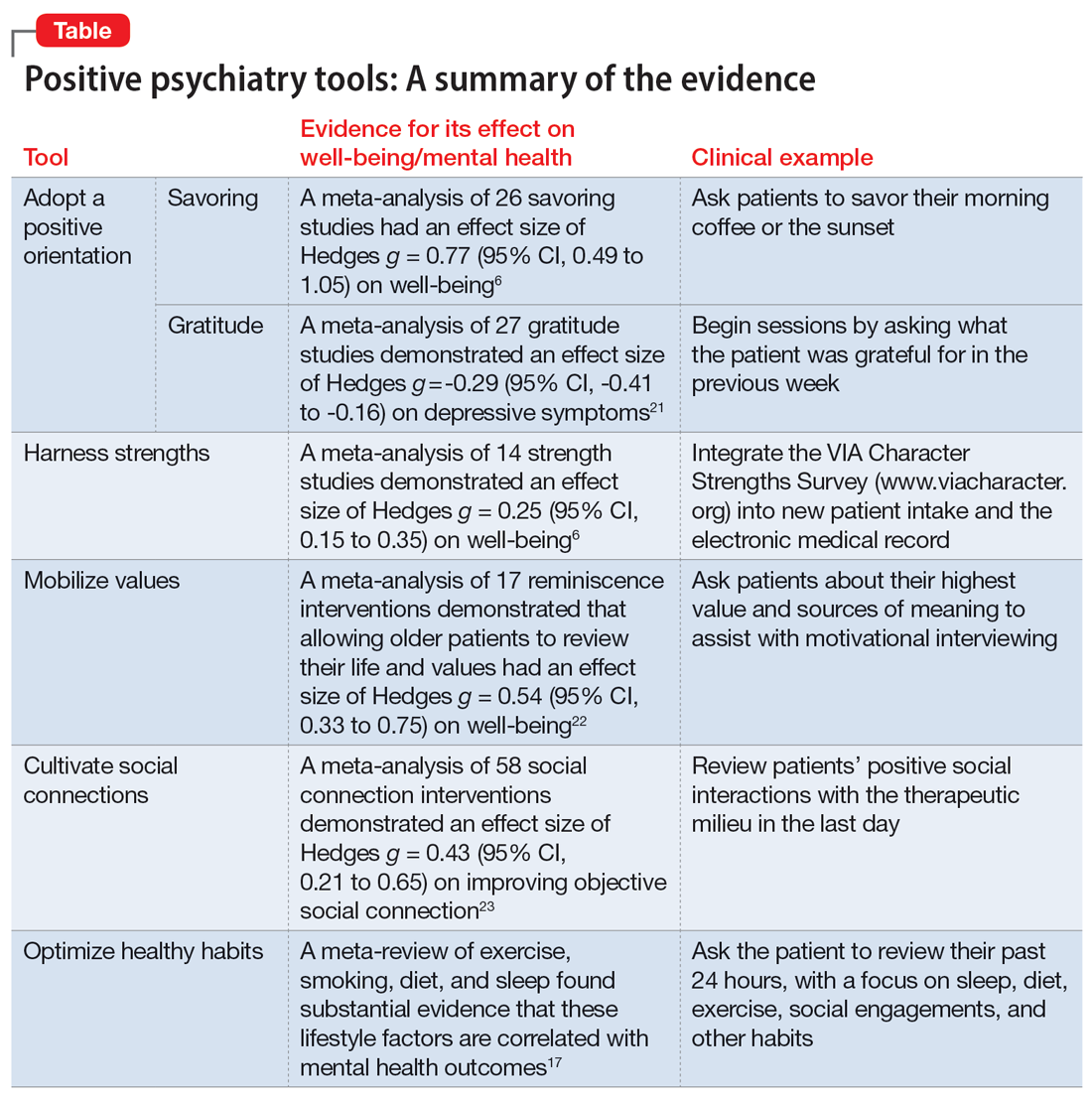

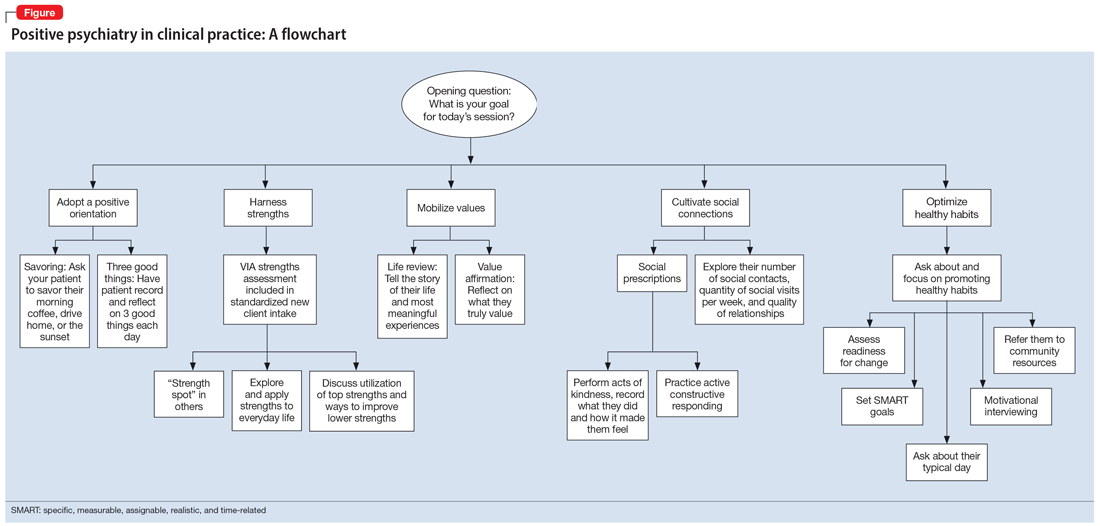

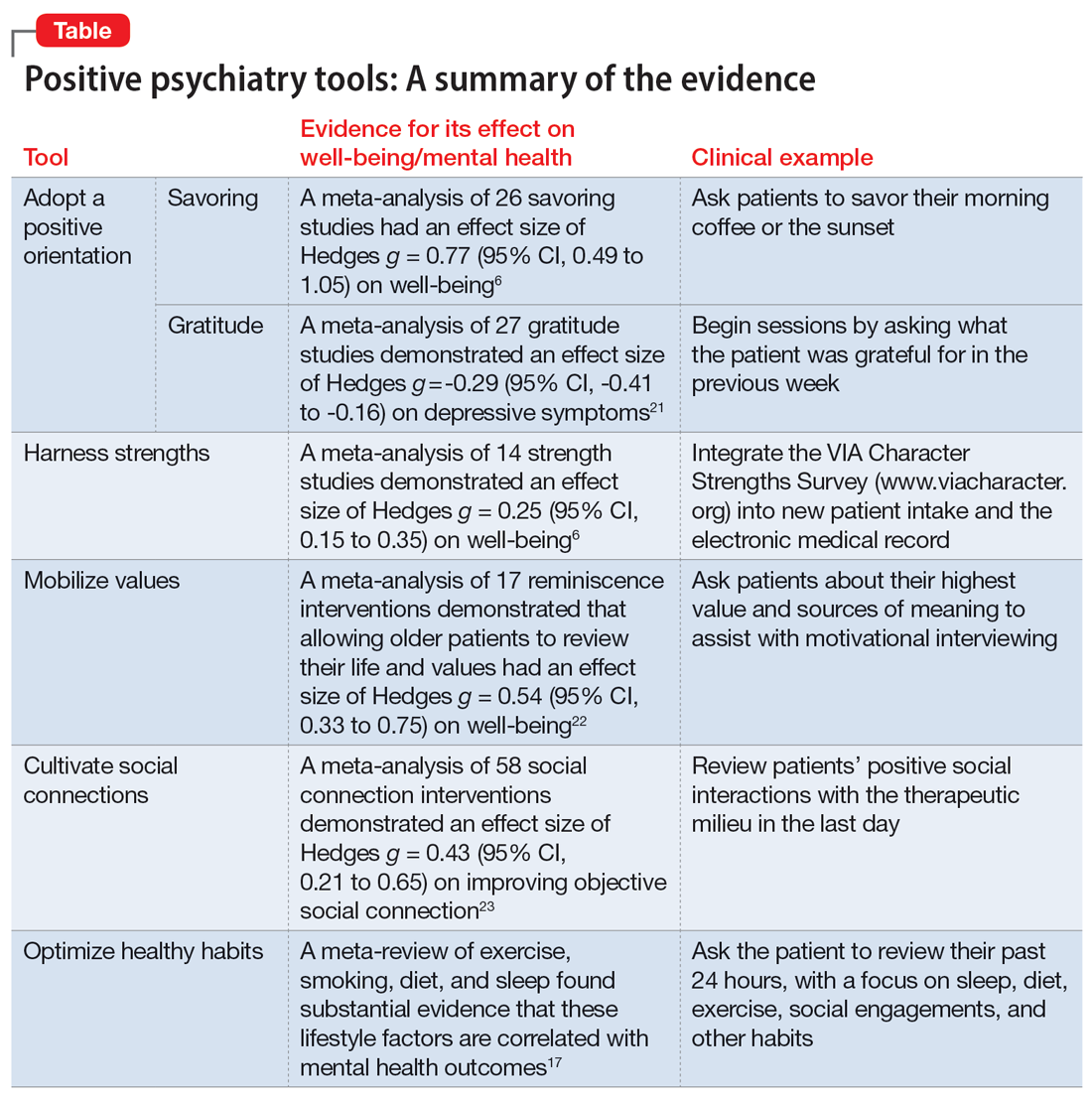

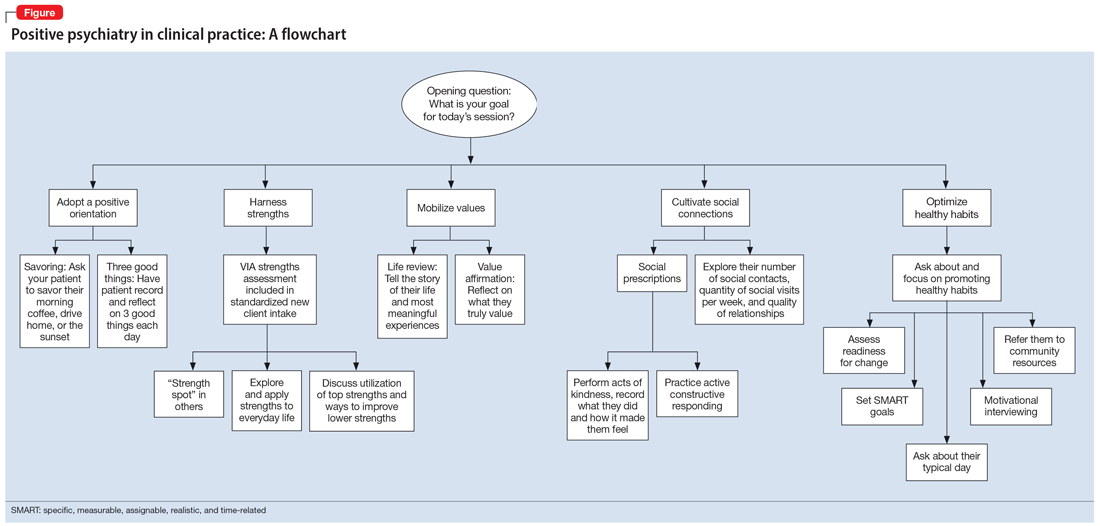

In Part 1, Boardman et al describe positive psychiatry tools to enhance clinical practice through positive interventions in several categories: adopting a positive orientation, harnessing strengths, mobilizing values, cultivating social connections, and optimizing health habits. The authors show how positive psychiatry aims to create a balance between pathogenesis (the study and understanding of diseases) and salutogenesis (the study and creation of health).4

In Part 2, Rettew discusses applying positive psychiatry principles and practices when working with children, adolescents, and their families. The author demonstrates how the principles and practices associated with positive psychiatry represent a natural and highly needed extension of the traditional work within child and adolescent psychiatry, and not a radical transformation of thought or effort. Rettew provides a case example in which he compares traditional and positive psychiatry approaches.

In Part 3, Oughli et al describe resilience in older adults with late-life depression, its clinical and neurocognitive correlates, and associated neurobiological and immunological biomarkers. The authors also narrate resilience-building interventions such as mind-body therapies, which have been reported to enhance resilience through promoting positive perceptions of various experiences and challenges. Evidence suggests that stress reduction, decreased inflammation, and improved emotional regulation may have direct neuroplastic effects on the brain, resulting in greater resilience.

Finally, in Part 4, Hamid Peseschkian summarizes the ideas and practices of positive psychotherapy (PPT) as practiced in Germany since its introduction by Nossrat Peseschkian in 1977. Based on a resource-oriented conception of human beings, PPT combines humanistic, systemic, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral aspects. This short-term method can be readily understood by patients from diverse cultures and social backgrounds.

Taken together, these articles present recent advances in positive psychiatry, especially from an intervention perspective. This is a timely development in view of the evidence of rising global rates of suicide, substance use, anxiety, depression, and perceived stress. By uniting a positive perspective, along with studying its neurobiological underpinnings, and taking a life-long approach, we can now apply these innovations to children, young adults, and older adults, thus providing clinicians with tools to enhance well-being and promote mental health in people with and without mental or physical illnesses.

1. Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

2. Jeste DV. A fulfilling year of APA presidency: from DSM-5 to positive psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(10):1102-1105.

3. Jeste DV. Positive psychiatry comes of age. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(12):1735-1738.

4. Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al (eds). The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Springer; 2017.

Historically, psychology and psychiatry have mostly focused on negative emotions and pathological states. However, during the last few decades, new developments in both disciplines have created novel vistas for a more comprehensive understanding of human behavior.1,2 These developments have taken on the names of positive psychology and positive psychiatry, respectively. Positive psychiatry is the science and practice of psychiatry that focuses on psycho-bio-social study and promotion of well-being and health through enhancement of positive psychosocial factors (eg, resilience, optimism, wisdom, social support) in people with illnesses or disabilities as well as in the community at large.3 This new perspective is aimed at enhancing and enriching psychiatric practice and research rather than replacing our stated aim of providing reliable and valid diagnostic categories along with effective therapeutic interventions.

In this issue of

In Part 1, Boardman et al describe positive psychiatry tools to enhance clinical practice through positive interventions in several categories: adopting a positive orientation, harnessing strengths, mobilizing values, cultivating social connections, and optimizing health habits. The authors show how positive psychiatry aims to create a balance between pathogenesis (the study and understanding of diseases) and salutogenesis (the study and creation of health).4

In Part 2, Rettew discusses applying positive psychiatry principles and practices when working with children, adolescents, and their families. The author demonstrates how the principles and practices associated with positive psychiatry represent a natural and highly needed extension of the traditional work within child and adolescent psychiatry, and not a radical transformation of thought or effort. Rettew provides a case example in which he compares traditional and positive psychiatry approaches.

In Part 3, Oughli et al describe resilience in older adults with late-life depression, its clinical and neurocognitive correlates, and associated neurobiological and immunological biomarkers. The authors also narrate resilience-building interventions such as mind-body therapies, which have been reported to enhance resilience through promoting positive perceptions of various experiences and challenges. Evidence suggests that stress reduction, decreased inflammation, and improved emotional regulation may have direct neuroplastic effects on the brain, resulting in greater resilience.

Finally, in Part 4, Hamid Peseschkian summarizes the ideas and practices of positive psychotherapy (PPT) as practiced in Germany since its introduction by Nossrat Peseschkian in 1977. Based on a resource-oriented conception of human beings, PPT combines humanistic, systemic, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral aspects. This short-term method can be readily understood by patients from diverse cultures and social backgrounds.

Taken together, these articles present recent advances in positive psychiatry, especially from an intervention perspective. This is a timely development in view of the evidence of rising global rates of suicide, substance use, anxiety, depression, and perceived stress. By uniting a positive perspective, along with studying its neurobiological underpinnings, and taking a life-long approach, we can now apply these innovations to children, young adults, and older adults, thus providing clinicians with tools to enhance well-being and promote mental health in people with and without mental or physical illnesses.

Historically, psychology and psychiatry have mostly focused on negative emotions and pathological states. However, during the last few decades, new developments in both disciplines have created novel vistas for a more comprehensive understanding of human behavior.1,2 These developments have taken on the names of positive psychology and positive psychiatry, respectively. Positive psychiatry is the science and practice of psychiatry that focuses on psycho-bio-social study and promotion of well-being and health through enhancement of positive psychosocial factors (eg, resilience, optimism, wisdom, social support) in people with illnesses or disabilities as well as in the community at large.3 This new perspective is aimed at enhancing and enriching psychiatric practice and research rather than replacing our stated aim of providing reliable and valid diagnostic categories along with effective therapeutic interventions.

In this issue of

In Part 1, Boardman et al describe positive psychiatry tools to enhance clinical practice through positive interventions in several categories: adopting a positive orientation, harnessing strengths, mobilizing values, cultivating social connections, and optimizing health habits. The authors show how positive psychiatry aims to create a balance between pathogenesis (the study and understanding of diseases) and salutogenesis (the study and creation of health).4

In Part 2, Rettew discusses applying positive psychiatry principles and practices when working with children, adolescents, and their families. The author demonstrates how the principles and practices associated with positive psychiatry represent a natural and highly needed extension of the traditional work within child and adolescent psychiatry, and not a radical transformation of thought or effort. Rettew provides a case example in which he compares traditional and positive psychiatry approaches.

In Part 3, Oughli et al describe resilience in older adults with late-life depression, its clinical and neurocognitive correlates, and associated neurobiological and immunological biomarkers. The authors also narrate resilience-building interventions such as mind-body therapies, which have been reported to enhance resilience through promoting positive perceptions of various experiences and challenges. Evidence suggests that stress reduction, decreased inflammation, and improved emotional regulation may have direct neuroplastic effects on the brain, resulting in greater resilience.

Finally, in Part 4, Hamid Peseschkian summarizes the ideas and practices of positive psychotherapy (PPT) as practiced in Germany since its introduction by Nossrat Peseschkian in 1977. Based on a resource-oriented conception of human beings, PPT combines humanistic, systemic, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral aspects. This short-term method can be readily understood by patients from diverse cultures and social backgrounds.

Taken together, these articles present recent advances in positive psychiatry, especially from an intervention perspective. This is a timely development in view of the evidence of rising global rates of suicide, substance use, anxiety, depression, and perceived stress. By uniting a positive perspective, along with studying its neurobiological underpinnings, and taking a life-long approach, we can now apply these innovations to children, young adults, and older adults, thus providing clinicians with tools to enhance well-being and promote mental health in people with and without mental or physical illnesses.

1. Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

2. Jeste DV. A fulfilling year of APA presidency: from DSM-5 to positive psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(10):1102-1105.

3. Jeste DV. Positive psychiatry comes of age. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(12):1735-1738.

4. Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al (eds). The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Springer; 2017.

1. Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

2. Jeste DV. A fulfilling year of APA presidency: from DSM-5 to positive psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(10):1102-1105.

3. Jeste DV. Positive psychiatry comes of age. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(12):1735-1738.

4. Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al (eds). The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Springer; 2017.

Using the tools of positive psychiatry to improve clinical practice

FIRST OF 4 PARTS

What does wellness mean to you? A 2018 survey posed this question to more than 6,000 people living with depression and bipolar disorder. In addition to better treatment and greater understanding of their illnesses, other priorities emerged: a longing for better days, a sense of purpose, and a longing to function well and be happy.1 As one respondent explained, “Wellness means stability; well enough to hold a job, well enough to enjoy activities, well enough to feel joy and hope.” Traditional treatment that focuses on alleviating symptoms may not sufficiently address outcomes patients value. When the focus is primarily deficit-based, clinicians and patients may miss opportunities for optimization and transformation.

Positive psychiatry is the science and practice of psychiatry that seeks to enhance and promote well-being and health through the enhancement of positive psychosocial factors such as resilience, optimism, wisdom, and social support in people with illnesses or disabilities as well as those in the community at large.2 It is based on the principles that there is no health without mental health, and that mental health can improve through preventive, therapeutic, and rehabilitative interventions.3

Positive interventions are defined as “treatment methods or intentional activities that aim to cultivate positive feelings, behaviors, or cognitions.”4 They are evidence-based intentional exercises designed to increase well-being and enhance flourishing. Although positive interventions were originally studied as activities for nonclinical populations and for helping healthy people thrive, they are increasingly being valued for their therapeutic role in treating psychopathology.5 By adding positive interventions to their toolbox, psychiatrists can expand the range of treatment options, better engage patients during the treatment process, and bolster positive mental health.

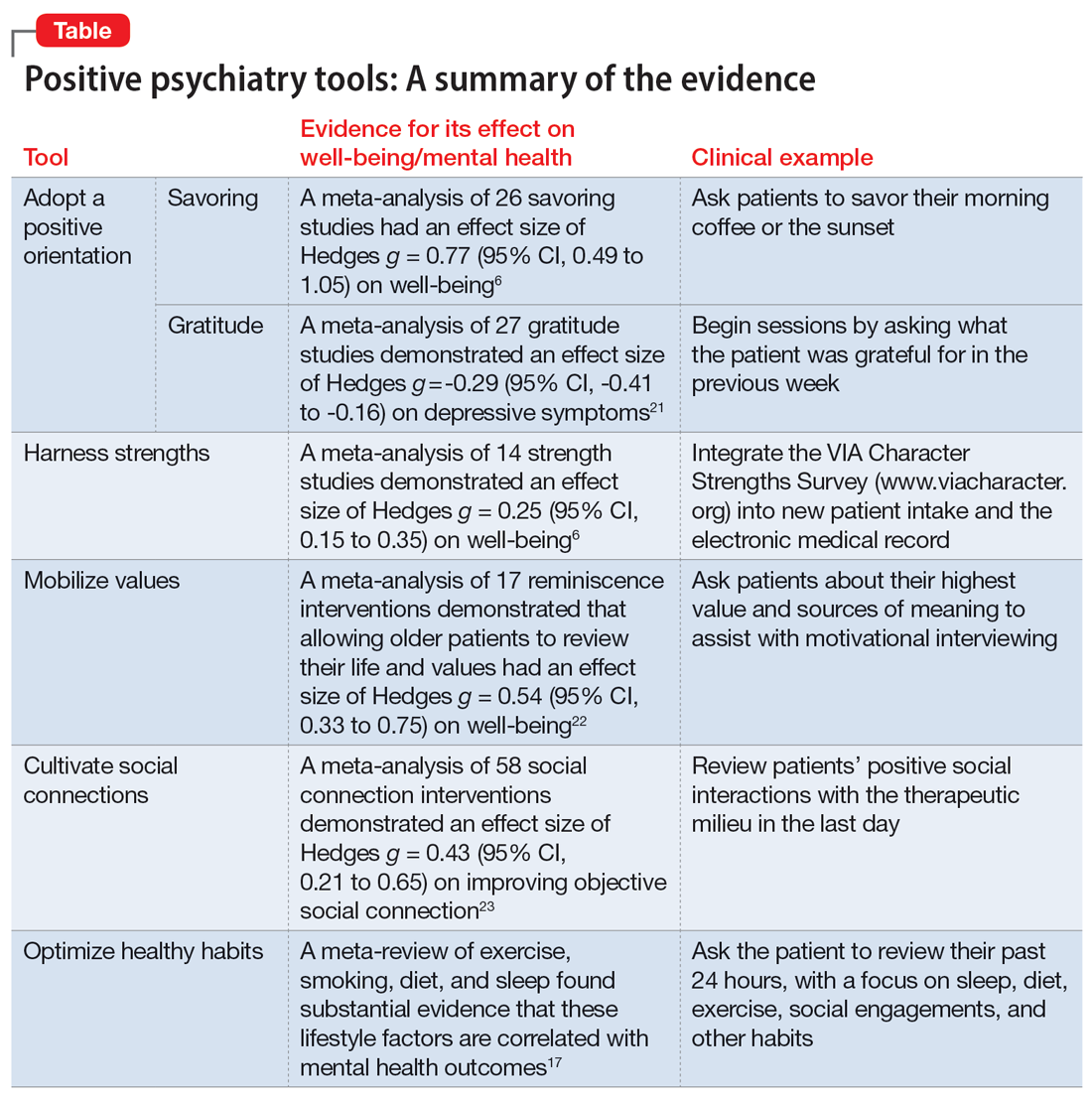

In this article, we provide practical ways to integrate the tools and principles of positive psychiatry into everyday clinical practice. The goal is to broaden how clinicians think about mental health and therapeutic options and, above all, enhance our patients’ everyday well-being. Teaching patients to adopt a positive orientation, harness strengths, mobilize values, cultivate social connections, and optimize healthy habits are strategies clinicians can apply not only to provide a counterweight to the traditional emphasis on illness, but also to enhance the range and richness of their patients’ everyday experience.

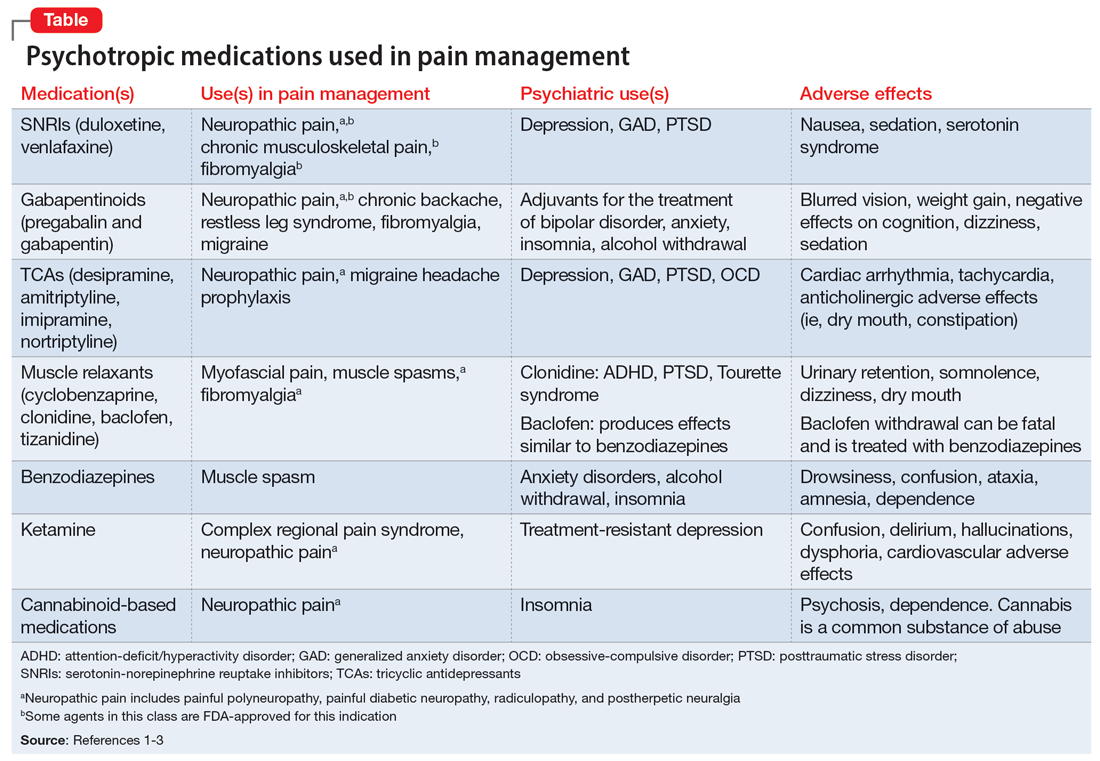

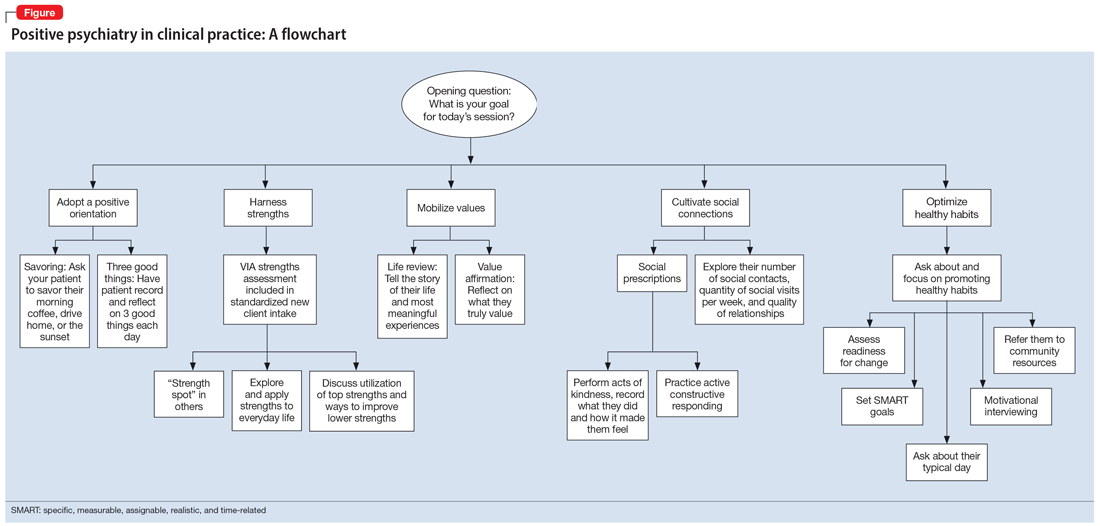

Adopt a positive orientation

When a clinician first meets a patient, “What’s wrong?” is a typical conversation starter, and conversations tend to revolve around problems, failures, and negative experiences. Positive psychiatry posits that there is therapeutic benefit to emphasizing and exploring a patient’s positive emotions, experiences, and aspirations. Questions such as “What was your sense of well-being this week? What is your goal for today’s session? What is your goal for the coming week?” can reorient a session towards an individual’s potential and promote exploration of what’s possible.

To promote a positive orientation, clinicians may consider integrating the Savoring and Three Good Things exercises—2 well-studied interventions—into their repertoire to activate and enhance positive emotional states such as gratitude and joy.6 An example of a Savoring activity is taking a 20-minute daily walk while trying to notice as many positive elements as possible. Similarly, the Three Good Things exercise, in which patients are asked to notice and write down 3 positive events and reflect on why they happened, promotes positive reflection and gratitude. A 14-day daily diary study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that higher levels of gratitude were associated with higher levels of positive affect, lower levels of perceived stress related to COVID-19, and better subjective health.7 In addition to coping with life’s negative events, deliberately enhancing the impact of good things is a positive emotion amplifier. As French writer François de La Rochefoucauld argued, “Happiness does not consist in things themselves but in the relish we have of them.”8

Continue to: Harness strengths

Harness strengths

A growing body of evidence suggests that in addition to focusing on a patient’s chief concern, identifying and cultivating an individual’s signature strengths can mitigate stress and enhance well-being. Signature strengths are positive personality qualities that reflect our core identity and are morally valued. The VIA Character Strengths Survey is the most used and validated psychometric instrument to measure and identify signature strengths such as curiosity, self-regulation, honesty, and teamwork.9

To incorporate this tool into clinical practice, ask patients to complete a strengths survey using a validated assessment tool such as the VIA survey (www.viacharacter.org). After a patient identifies their signature strengths, encourage them to explore and apply these strengths in everyday life and in new ways. In addition to becoming aware of and using their signature strengths, encourage patients to “strengths spot” in others. “What strengths did you notice your coworker, family, or friend using today?” is a potential question to explore with patients. A strengths-based approach may be particularly helpful in uncovering motivation and fully engaging patients in treatment. Moreover, integrating strengths into the typically negatively skewed narrative underscores to patients that therapy isn’t only about untwisting distorted thinking, but also about harnessing one’s strengths, talents, and abilities. Strengths expressed through pragmatic actions can boost coping skills as well as enhance well-being.

Mobilize values

Value affirmation exercises have been shown to generate lasting benefits in creating positive feelings and behaviors.10 Encouraging patients to think about what they genuinely value redirects their gaze towards possibility and diverts self-focus. For instance, ask a patient to identify 2 or 3 values and write about why they are important. By reflecting on their values in writing, they affirm their identity and self-worth, thus creating a virtuous cycle of confidence, effort, and achievement. People who put their values front and center are more attuned to the needs of others as well as their own needs, and they make better connections.11 Including a patient’s values in the treatment plan may increase problem-solving skills, boost motivation, and build better stress management skills.

The “life review” is another intervention that facilitates exploration of a patient’s values. This exercise involves asking patients to recount the story of their life and the experiences that were most meaningful to them. This process allows clinicians to gain a deeper understanding of the patient’s values, which can help guide treatment. Meta-analytic evidence has demonstrated these reminiscence-based interventions have significant effects on well-being.6 As Mahatma Gandhi famously said, “Happiness is when what you think, what you say, and what you do are in harmony.” Creating more overlap between a patient’s values and their everyday actions and behaviors bolsters resilience, buffers against stress, and can restore a healthier self-concept.

Cultivate social connections

Social connection is recognized as a core psychological need and essential for well-being. The opposite of connection—social isolation—has negative effects on overall health, including increases in inflammatory markers, depression rates, and even all-cause mortality.12 A 2015 meta-analytic review demonstrated that loneliness increased the likelihood of mortality by 26%—a similar increase as seen with smoking 15 cigarettes a day.13

Continue to: As with any vital sign...

As with any vital sign, exploring a patient’s number of social contacts, quantity of social visits per week, and quality of relationships is an important indicator of health. Giving patients tools to cultivate social connection and deepen their relationships can enhance therapeutic outcomes. Asking patients to perform acts of kindness is one example of a “social prescription.” Feeding a stranger’s parking meter, picking up litter, helping a friend with a chore, providing a meal to a person in need, and volunteering are potential ways for patients to engage in kind deeds. After each act, encourage the patient to write down what they did and how it made them feel.

“Prescribing” positive communication is another way to enhance a patient’s social connections. For instance, teaching them about active constructive responding (ACR)—responding with enthusiasm when another person shares information or good news—has been shown to strengthen bonds with friends and family.14 Making eye contact, giving the other person one’s full attention, inquiring about details, and responding with enthusiasm and interest are simple ways patients can apply ACR in their daily lives. Counseling a patient on increasing social connections, prescribing connections, and inquiring about quantity and quality of social interactions can help them not only add years to their life but also add health and well-being to those years.

Optimize healthy habits

Mounting research demonstrates that exercise, sleep, and nutrition are important for well-being. Evidence shows that therapeutic lifestyle changes can reduce depressive symptoms and boost positive feelings. Numerous meta-analyses have demonstrated the benefits of sleep and exercise interventions for reducing depressive symptoms in psychiatric patients.15,16 Longitudinal studies have provided evidence that healthy diets increase happiness, even after controlling for potential confounders such as socioeconomic factors.17 Other lifestyle factors—including financial stability, pet ownership, decreased social media use, and spending time in nature—have been shown to contribute to well-being.18

Despite the substantial evidence that lifestyle factors can improve health outcomes, few clinicians ask about, focus on, or promote positive habits.19 Positive psychiatry seeks to reorient clinicians towards lifestyle factors that enhance well-being. Clinicians can deploy a variety of strategies to support patients in making healthy and sustainable changes. Assessing readiness for change, motivational interviewing, setting SMART (specific, measurable, assignable, realistic, and time-related) goals, and referring patients to relevant community resources are ways to encourage and promote therapeutic lifestyle changes. Inquiring about a patient’s typical day—such as how they spend their free time, what they eat, when they go to bed, and how much time they spend outdoors—opens conversations about general well-being and shows the patient that therapy is about the whole person, and not only symptom management. Helping patients have better days can empower them to lead more satisfied lives.20

The Table6,17,21-23 summarizes the scientific evidence for the strategies described in this article. The Figure provides a flowchart for using these strategies in clinical practice.

Continue to: Balancing pathogenesis with salutogenesis

Balancing pathogenesis with salutogenesis

By exploring and emphasizing potential and possibility, positive psychiatry aims to create a balance between pathogenesis (the study and understanding of disease) with salutogenesis (the study and creation of health24). Clinicians are well positioned to manage symptoms and bolster positive states. Rather than an either/or approach to well-being, positive psychiatry strives for a both/and approach to well-being. By adding positive interventions to their toolbox, clinicians can expand the range of treatment options, better engage patients in the treatment process, and bolster mental health.

Bottom Line

Clinicians can integrate the tools and principles of positive psychiatry into clinical practice. Teaching patients to adopt a positive orientation, harness strengths, mobilize values, cultivate social connections, and optimize healthy habits can not only provide a counterweight to the traditional emphasis on illness, but also can enhance the range and richness of patients’ everyday experience.

Related Resources

- University of Pennsylvania. Authentic happiness. https://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW (eds). Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015.

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

1. Morton E, Foxworth P, Dardess P, et al. “Supporting Wellness”: a depression and bipolar support alliance mixed-methods investigation of lived experience perspectives and priorities for mood disorder treatment. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:575-584.

2. Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

3. Jeste DV. Positive psychiatry comes of age. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(12):1735-1738.

4. Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):467-487.

5. Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 2006;61(8):774-788.

6. Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, et al. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2021;16(6):749-769.

7. Jiang D. Feeling gratitude is associated with better well-being across the life span: a daily diary study during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77(4):e36-e45.

8. de La Rochefoucauld F. Maxims and moral reflections (1796). Gale ECCO: 2010.

9. Niemiec RM. VIA character strengths: Research and practice (The first 10 years). In: Knoop HH, Fave AD (eds). Well-being and Cultures. Springer;2013:11-29.

10. Cohen GL, Sherman DK. The psychology of change: self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:333-371.

11. Thomaes S, Bushman BJ, de Castro BO, et al. Arousing “gentle passions” in young adolescents: sustained experimental effects of value affirmations on prosocial feelings and behaviors. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(1):103-110.

12. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, et al. The neuroendocrinology of social isolation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:733-767.

13. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227-237.

14. Gable SL, Reis HT, Impett EA, et al. What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87(2):228-245.

15. Gee B, Orchard F, Clarke E, et al. The effect of non-pharmacological sleep interventions on depression symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;43:118-128.

16. Krogh J, Hjorthøj C, Speyer H, et al. Exercise for patients with major depression: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e014820. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014820

17. Firth J, Solmi M, Wootton RE, et al. A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):360-380.

18. Piotrowski MC, Lunsford J, Gaynes BN. Lifestyle psychiatry for depression and anxiety: beyond diet and exercise. Lifestyle Med. 2021;2(1):e21. doi:10.1002/lim2.21

19. Janney CA, Brzoznowski KF, Richardson Cret al. Moving towards wellness: physical activity practices, perspectives, and preferences of users of outpatient mental health service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;49:63-66.

20. Walsh R. Lifestyle and mental health. Am Psychol. 2011;66(7):579-592.

21. Cregg DR, Cheavens JS. Gratitude interventions: effective self-help? A meta-analysis of the impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. J Happiness Stud. 2021;22(1):413-445.

22. Bohlmeijer E, Roemer M, Cuijpers P, et al. The effects of reminiscence on psychological well-being in older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(3):291-300.

23. Zagic D, Wuthrich VM, Rapee RM, et al. Interventions to improve social connections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(5):885-906.

24. Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al (eds). The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Springer; 2017.

FIRST OF 4 PARTS

What does wellness mean to you? A 2018 survey posed this question to more than 6,000 people living with depression and bipolar disorder. In addition to better treatment and greater understanding of their illnesses, other priorities emerged: a longing for better days, a sense of purpose, and a longing to function well and be happy.1 As one respondent explained, “Wellness means stability; well enough to hold a job, well enough to enjoy activities, well enough to feel joy and hope.” Traditional treatment that focuses on alleviating symptoms may not sufficiently address outcomes patients value. When the focus is primarily deficit-based, clinicians and patients may miss opportunities for optimization and transformation.

Positive psychiatry is the science and practice of psychiatry that seeks to enhance and promote well-being and health through the enhancement of positive psychosocial factors such as resilience, optimism, wisdom, and social support in people with illnesses or disabilities as well as those in the community at large.2 It is based on the principles that there is no health without mental health, and that mental health can improve through preventive, therapeutic, and rehabilitative interventions.3

Positive interventions are defined as “treatment methods or intentional activities that aim to cultivate positive feelings, behaviors, or cognitions.”4 They are evidence-based intentional exercises designed to increase well-being and enhance flourishing. Although positive interventions were originally studied as activities for nonclinical populations and for helping healthy people thrive, they are increasingly being valued for their therapeutic role in treating psychopathology.5 By adding positive interventions to their toolbox, psychiatrists can expand the range of treatment options, better engage patients during the treatment process, and bolster positive mental health.

In this article, we provide practical ways to integrate the tools and principles of positive psychiatry into everyday clinical practice. The goal is to broaden how clinicians think about mental health and therapeutic options and, above all, enhance our patients’ everyday well-being. Teaching patients to adopt a positive orientation, harness strengths, mobilize values, cultivate social connections, and optimize healthy habits are strategies clinicians can apply not only to provide a counterweight to the traditional emphasis on illness, but also to enhance the range and richness of their patients’ everyday experience.

Adopt a positive orientation