User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Scurvy in psychiatric patients: An easy-to-miss diagnosis

Two years ago, I cared for Ms. L, a woman in her late 40s who had a history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Unable to work and highly distressed throughout the day, Ms. L was admitted to our psychiatric unit due to her functional decompensation and symptom severity.

Ms. L was extremely focused on physical symptoms. She had rigid rules regarding which beauty products she could and could not use (she insisted most soaps gave her a rash, though she did not have any clear documentation of this) as well as the types of food she could and could not eat due to fear of an allergic reaction (skin testing was negative for the foods she claimed were problematic, though this did not change her selective eating habits). By the time she was admitted to our unit, in addition to outpatient mental health, she was being treated by internal medicine, allergy and immunology, and dermatology, with largely equivocal objective findings.

During her psychiatric admission intake, Ms. L mentioned that due to her fear of anaphylaxis, she hadn’t eaten any fruits or vegetables for at least 2 years. As a result, I ordered testing of her vitamin C level.

Three days following admission, Ms. L requested to be discharged because she said she needed to care for her pet. She reported feeling less anxious, and because the treatment team felt she did not meet the criteria for an involuntary hold, she was discharged. A week later, the results of her vitamin C level came back, indicating a severe deficiency (<0.1 mg/dL; reference range: 0.3 to 2.7 mg/dL). I contacted her outpatient team, and vitamin C supplementation was started immediately.

Notes from Ms. L’s subsequent outpatient mental health visits indicated improvement in her somatic symptoms (less perseveration), although over the next year her scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scales were largely unchanged (fluctuating within the range of 11 to 17 and 12 to 17, respectively). One year later, Ms. L stopped taking vitamin C supplements because she was afraid she was becoming allergic to them, though there was no objective evidence to support this belief. Her vitamin C levels were within the normal range at the time and have not been rechecked since then.

Ms. L’s obsession with “healthy eating” led to numerous red herrings for clinicians, as she was anxious about every food. Countertransference and feelings of frustration may have also led clinicians in multiple specialties to miss the diagnosis of scurvy. Vitamin C supplementation did not result in remission of Ms. L’s symptoms, which reflects the complexity and severity of her comorbid psychiatric illnesses. However, a decrease in her perseveration on somatic symptoms afforded increased opportunities to address her other psychiatric diagnoses. Ms. L eventually enrolled in an eating disorders program, which was beneficial to her.

Keep scurvy in the differential Dx

Symptoms of scurvy include malaise; lethargy; anemia; myalgia; bone pain; easy bruising; petechiae and perifollicular hemorrhages (due to capillary fragility); gum disease; mood changes; and depression.1 In later stages, the presentation can progress to edema; jaundice; hemolysis and spontaneous bleeding; neuropathy; fever; convulsions; and death.

1. Léger D. Scurvy: reemergence of nutritional deficiencies. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(10):1403-1406.

2. Velandia B, Centor RM, McConnell V, et al. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1281-1284.

3. Meisel K, Daggubati S, Josephson SA. Scurvy in the 21st century? Vitamin C deficiency presenting to the neurologist. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5(6):491-493.

Two years ago, I cared for Ms. L, a woman in her late 40s who had a history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Unable to work and highly distressed throughout the day, Ms. L was admitted to our psychiatric unit due to her functional decompensation and symptom severity.

Ms. L was extremely focused on physical symptoms. She had rigid rules regarding which beauty products she could and could not use (she insisted most soaps gave her a rash, though she did not have any clear documentation of this) as well as the types of food she could and could not eat due to fear of an allergic reaction (skin testing was negative for the foods she claimed were problematic, though this did not change her selective eating habits). By the time she was admitted to our unit, in addition to outpatient mental health, she was being treated by internal medicine, allergy and immunology, and dermatology, with largely equivocal objective findings.

During her psychiatric admission intake, Ms. L mentioned that due to her fear of anaphylaxis, she hadn’t eaten any fruits or vegetables for at least 2 years. As a result, I ordered testing of her vitamin C level.

Three days following admission, Ms. L requested to be discharged because she said she needed to care for her pet. She reported feeling less anxious, and because the treatment team felt she did not meet the criteria for an involuntary hold, she was discharged. A week later, the results of her vitamin C level came back, indicating a severe deficiency (<0.1 mg/dL; reference range: 0.3 to 2.7 mg/dL). I contacted her outpatient team, and vitamin C supplementation was started immediately.

Notes from Ms. L’s subsequent outpatient mental health visits indicated improvement in her somatic symptoms (less perseveration), although over the next year her scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scales were largely unchanged (fluctuating within the range of 11 to 17 and 12 to 17, respectively). One year later, Ms. L stopped taking vitamin C supplements because she was afraid she was becoming allergic to them, though there was no objective evidence to support this belief. Her vitamin C levels were within the normal range at the time and have not been rechecked since then.

Ms. L’s obsession with “healthy eating” led to numerous red herrings for clinicians, as she was anxious about every food. Countertransference and feelings of frustration may have also led clinicians in multiple specialties to miss the diagnosis of scurvy. Vitamin C supplementation did not result in remission of Ms. L’s symptoms, which reflects the complexity and severity of her comorbid psychiatric illnesses. However, a decrease in her perseveration on somatic symptoms afforded increased opportunities to address her other psychiatric diagnoses. Ms. L eventually enrolled in an eating disorders program, which was beneficial to her.

Keep scurvy in the differential Dx

Symptoms of scurvy include malaise; lethargy; anemia; myalgia; bone pain; easy bruising; petechiae and perifollicular hemorrhages (due to capillary fragility); gum disease; mood changes; and depression.1 In later stages, the presentation can progress to edema; jaundice; hemolysis and spontaneous bleeding; neuropathy; fever; convulsions; and death.

Two years ago, I cared for Ms. L, a woman in her late 40s who had a history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Unable to work and highly distressed throughout the day, Ms. L was admitted to our psychiatric unit due to her functional decompensation and symptom severity.

Ms. L was extremely focused on physical symptoms. She had rigid rules regarding which beauty products she could and could not use (she insisted most soaps gave her a rash, though she did not have any clear documentation of this) as well as the types of food she could and could not eat due to fear of an allergic reaction (skin testing was negative for the foods she claimed were problematic, though this did not change her selective eating habits). By the time she was admitted to our unit, in addition to outpatient mental health, she was being treated by internal medicine, allergy and immunology, and dermatology, with largely equivocal objective findings.

During her psychiatric admission intake, Ms. L mentioned that due to her fear of anaphylaxis, she hadn’t eaten any fruits or vegetables for at least 2 years. As a result, I ordered testing of her vitamin C level.

Three days following admission, Ms. L requested to be discharged because she said she needed to care for her pet. She reported feeling less anxious, and because the treatment team felt she did not meet the criteria for an involuntary hold, she was discharged. A week later, the results of her vitamin C level came back, indicating a severe deficiency (<0.1 mg/dL; reference range: 0.3 to 2.7 mg/dL). I contacted her outpatient team, and vitamin C supplementation was started immediately.

Notes from Ms. L’s subsequent outpatient mental health visits indicated improvement in her somatic symptoms (less perseveration), although over the next year her scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scales were largely unchanged (fluctuating within the range of 11 to 17 and 12 to 17, respectively). One year later, Ms. L stopped taking vitamin C supplements because she was afraid she was becoming allergic to them, though there was no objective evidence to support this belief. Her vitamin C levels were within the normal range at the time and have not been rechecked since then.

Ms. L’s obsession with “healthy eating” led to numerous red herrings for clinicians, as she was anxious about every food. Countertransference and feelings of frustration may have also led clinicians in multiple specialties to miss the diagnosis of scurvy. Vitamin C supplementation did not result in remission of Ms. L’s symptoms, which reflects the complexity and severity of her comorbid psychiatric illnesses. However, a decrease in her perseveration on somatic symptoms afforded increased opportunities to address her other psychiatric diagnoses. Ms. L eventually enrolled in an eating disorders program, which was beneficial to her.

Keep scurvy in the differential Dx

Symptoms of scurvy include malaise; lethargy; anemia; myalgia; bone pain; easy bruising; petechiae and perifollicular hemorrhages (due to capillary fragility); gum disease; mood changes; and depression.1 In later stages, the presentation can progress to edema; jaundice; hemolysis and spontaneous bleeding; neuropathy; fever; convulsions; and death.

1. Léger D. Scurvy: reemergence of nutritional deficiencies. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(10):1403-1406.

2. Velandia B, Centor RM, McConnell V, et al. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1281-1284.

3. Meisel K, Daggubati S, Josephson SA. Scurvy in the 21st century? Vitamin C deficiency presenting to the neurologist. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5(6):491-493.

1. Léger D. Scurvy: reemergence of nutritional deficiencies. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(10):1403-1406.

2. Velandia B, Centor RM, McConnell V, et al. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1281-1284.

3. Meisel K, Daggubati S, Josephson SA. Scurvy in the 21st century? Vitamin C deficiency presenting to the neurologist. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5(6):491-493.

Breast cancer screening in women receiving antipsychotics

Women with severe mental illness (SMI) are more likely to develop breast cancer and often have more advanced stages of breast cancer when it is detected.1 Antipsychotics have a wide variety of FDA-approved indications and many important life-saving properties. However, patients treated with antipsychotic medications that increase prolactin levels require special consideration with regards to referral for breast cancer screening. Although no clear causal link between antipsychotic use and breast cancer has been established, antipsychotics that raise serum prolactin levels (haloperidol, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone) are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer than antipsychotics that produce smaller increases in prolactin levels (aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone).2,3 Risperidone and paliperidone have the highest propensities to increase prolactin (45 to >100 ng/mL), whereas other second-generation antipsychotics are associated with only modest elevations.4 Prolonged exposure to high serum prolactin levels should be avoided in women due to the increased risk for breast cancer.2,3 Although there are no clear rules regarding which number or cluster of personal risk factors necessitates a further risk assessment for breast cancer, women receiving antipsychotics (especially those age ≥40) can be referred for further assessment. An individualized, patient-centered approach should be used.

Recognize risk factors

Patients with SMI often need to take a regimen of medications, including antipsychotics, for weeks or months to stabilize their symptoms. Once a woman with SMI is stabilized, consider referral to a clinic that can comprehensively assess for breast cancer risk. Nonmodifiable risk factors include older age, certain genetic mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), early menarche, late menopause, high breast tissue density as detected by mammography, a family history of breast cancer, and exposure to radiation.5,6 Modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, being overweight or obese, hormonal exposure, drinking alcohol, and the presence of certain factors in the patient’s reproductive history (first pregnancy after age 30, not breastfeeding, and never having a full-term pregnancy).2,3 When making such referrals, it is important to avoid making the patient feel alarmed or frightened of antipsychotics. Instead, explain that a referral for breast cancer screening is routine.

When to refer

All women age ≥40 should be offered a referral to a clinic that can provide screening mammography. If a woman has pain, detects a lump in her breast, has a bloody discharge from the nipple, or has changes in the shape or texture of the nipple or breast, a more urgent referral should be made.4 The most important thing to remember is that early breast lesion detection can be life-saving and can avert the need for more invasive surgeries as well as exposure to chemotherapy and radiation.

What to do when prolactin is elevated

Ongoing monitoring of serum prolactin levels can help ensure that the patient’s levels remain in a normal range (<25 ng/mL).2,3,5,6 If hyperprolactinemia is detected, consider switching to an antipsychotic less likely to increase prolactin. Alternatively, the addition of aripiprazole/brexpiprazole or a dopamine agonist as combination therapy can be considered to rapidly restore normal prolactin levels.2 Such changes should be carefully considered because patients may decompensate if antipsychotics are abruptly switched. An individualized risk vs benefit analysis is necessary for any patient in this situation. Risks include not only the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms but also a potential loss of their current level of functioning. Patients may need to continue to take an antipsychotic that is more likely to increase prolactin, in which case close monitoring is advised as well as collaboration with other physicians and members of the patient’s care team. Involving the patient’s support system is helpful.

1. Weinstein LC, Stefancic A, Cunningham AT, et al. Cancer screening, prevention, and treatment in people with mental illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):134-151.

2. Rahman T, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. Risk of breast cancer with prolactin elevating antipsychotic drugs: an observational study of US women (ages 18–64 years). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):7-16.

3. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

4. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421-453.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Breast cancer. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/index.htm

6. Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(12):1361-1366.

Women with severe mental illness (SMI) are more likely to develop breast cancer and often have more advanced stages of breast cancer when it is detected.1 Antipsychotics have a wide variety of FDA-approved indications and many important life-saving properties. However, patients treated with antipsychotic medications that increase prolactin levels require special consideration with regards to referral for breast cancer screening. Although no clear causal link between antipsychotic use and breast cancer has been established, antipsychotics that raise serum prolactin levels (haloperidol, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone) are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer than antipsychotics that produce smaller increases in prolactin levels (aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone).2,3 Risperidone and paliperidone have the highest propensities to increase prolactin (45 to >100 ng/mL), whereas other second-generation antipsychotics are associated with only modest elevations.4 Prolonged exposure to high serum prolactin levels should be avoided in women due to the increased risk for breast cancer.2,3 Although there are no clear rules regarding which number or cluster of personal risk factors necessitates a further risk assessment for breast cancer, women receiving antipsychotics (especially those age ≥40) can be referred for further assessment. An individualized, patient-centered approach should be used.

Recognize risk factors

Patients with SMI often need to take a regimen of medications, including antipsychotics, for weeks or months to stabilize their symptoms. Once a woman with SMI is stabilized, consider referral to a clinic that can comprehensively assess for breast cancer risk. Nonmodifiable risk factors include older age, certain genetic mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), early menarche, late menopause, high breast tissue density as detected by mammography, a family history of breast cancer, and exposure to radiation.5,6 Modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, being overweight or obese, hormonal exposure, drinking alcohol, and the presence of certain factors in the patient’s reproductive history (first pregnancy after age 30, not breastfeeding, and never having a full-term pregnancy).2,3 When making such referrals, it is important to avoid making the patient feel alarmed or frightened of antipsychotics. Instead, explain that a referral for breast cancer screening is routine.

When to refer

All women age ≥40 should be offered a referral to a clinic that can provide screening mammography. If a woman has pain, detects a lump in her breast, has a bloody discharge from the nipple, or has changes in the shape or texture of the nipple or breast, a more urgent referral should be made.4 The most important thing to remember is that early breast lesion detection can be life-saving and can avert the need for more invasive surgeries as well as exposure to chemotherapy and radiation.

What to do when prolactin is elevated

Ongoing monitoring of serum prolactin levels can help ensure that the patient’s levels remain in a normal range (<25 ng/mL).2,3,5,6 If hyperprolactinemia is detected, consider switching to an antipsychotic less likely to increase prolactin. Alternatively, the addition of aripiprazole/brexpiprazole or a dopamine agonist as combination therapy can be considered to rapidly restore normal prolactin levels.2 Such changes should be carefully considered because patients may decompensate if antipsychotics are abruptly switched. An individualized risk vs benefit analysis is necessary for any patient in this situation. Risks include not only the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms but also a potential loss of their current level of functioning. Patients may need to continue to take an antipsychotic that is more likely to increase prolactin, in which case close monitoring is advised as well as collaboration with other physicians and members of the patient’s care team. Involving the patient’s support system is helpful.

Women with severe mental illness (SMI) are more likely to develop breast cancer and often have more advanced stages of breast cancer when it is detected.1 Antipsychotics have a wide variety of FDA-approved indications and many important life-saving properties. However, patients treated with antipsychotic medications that increase prolactin levels require special consideration with regards to referral for breast cancer screening. Although no clear causal link between antipsychotic use and breast cancer has been established, antipsychotics that raise serum prolactin levels (haloperidol, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone) are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer than antipsychotics that produce smaller increases in prolactin levels (aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone).2,3 Risperidone and paliperidone have the highest propensities to increase prolactin (45 to >100 ng/mL), whereas other second-generation antipsychotics are associated with only modest elevations.4 Prolonged exposure to high serum prolactin levels should be avoided in women due to the increased risk for breast cancer.2,3 Although there are no clear rules regarding which number or cluster of personal risk factors necessitates a further risk assessment for breast cancer, women receiving antipsychotics (especially those age ≥40) can be referred for further assessment. An individualized, patient-centered approach should be used.

Recognize risk factors

Patients with SMI often need to take a regimen of medications, including antipsychotics, for weeks or months to stabilize their symptoms. Once a woman with SMI is stabilized, consider referral to a clinic that can comprehensively assess for breast cancer risk. Nonmodifiable risk factors include older age, certain genetic mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), early menarche, late menopause, high breast tissue density as detected by mammography, a family history of breast cancer, and exposure to radiation.5,6 Modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, being overweight or obese, hormonal exposure, drinking alcohol, and the presence of certain factors in the patient’s reproductive history (first pregnancy after age 30, not breastfeeding, and never having a full-term pregnancy).2,3 When making such referrals, it is important to avoid making the patient feel alarmed or frightened of antipsychotics. Instead, explain that a referral for breast cancer screening is routine.

When to refer

All women age ≥40 should be offered a referral to a clinic that can provide screening mammography. If a woman has pain, detects a lump in her breast, has a bloody discharge from the nipple, or has changes in the shape or texture of the nipple or breast, a more urgent referral should be made.4 The most important thing to remember is that early breast lesion detection can be life-saving and can avert the need for more invasive surgeries as well as exposure to chemotherapy and radiation.

What to do when prolactin is elevated

Ongoing monitoring of serum prolactin levels can help ensure that the patient’s levels remain in a normal range (<25 ng/mL).2,3,5,6 If hyperprolactinemia is detected, consider switching to an antipsychotic less likely to increase prolactin. Alternatively, the addition of aripiprazole/brexpiprazole or a dopamine agonist as combination therapy can be considered to rapidly restore normal prolactin levels.2 Such changes should be carefully considered because patients may decompensate if antipsychotics are abruptly switched. An individualized risk vs benefit analysis is necessary for any patient in this situation. Risks include not only the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms but also a potential loss of their current level of functioning. Patients may need to continue to take an antipsychotic that is more likely to increase prolactin, in which case close monitoring is advised as well as collaboration with other physicians and members of the patient’s care team. Involving the patient’s support system is helpful.

1. Weinstein LC, Stefancic A, Cunningham AT, et al. Cancer screening, prevention, and treatment in people with mental illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):134-151.

2. Rahman T, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. Risk of breast cancer with prolactin elevating antipsychotic drugs: an observational study of US women (ages 18–64 years). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):7-16.

3. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

4. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421-453.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Breast cancer. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/index.htm

6. Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(12):1361-1366.

1. Weinstein LC, Stefancic A, Cunningham AT, et al. Cancer screening, prevention, and treatment in people with mental illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):134-151.

2. Rahman T, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. Risk of breast cancer with prolactin elevating antipsychotic drugs: an observational study of US women (ages 18–64 years). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):7-16.

3. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

4. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421-453.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Breast cancer. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/index.htm

6. Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(12):1361-1366.

Should residents be taught how to prescribe monoamine oxidase inhibitors?

What else can I offer this patient?

This thought passed through my mind as the patient’s desperation grew palpable. He had experienced intractable major depressive disorder (MDD) for years and had exhausted multiple classes of antidepressants, trying various combinations without any relief.

The previous resident had arranged for intranasal ketamine treatment, but the patient was unable to receive it due to lack of transportation. As I combed through the list of the dozens of medications the patient previously had been prescribed, I noticed the absence of a certain class of agents: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

My knowledge of MAOIs stemmed from medical school, where the dietary restrictions, potential for hypertensive crisis, and capricious drug-drug interactions were heavily emphasized while their value was minimized. I did not have any practical experience with these medications, and even the attending physician disclosed he had not prescribed an MAOI in more than 30 years. Nonetheless, both the attending physician and patient agreed that the patient would try one.

Following a washout period, the patient began tranylcypromine. After taking tranylcypromine 40 mg/d for 3 months, he reported he felt like a weight had been lifted off his chest. He felt less irritable and depressed, more energetic, and more hopeful for the future. He also felt that his symptoms were improving for the first time in many years.

An older but still potentially helpful class of medications

MDD is one of the leading causes of disability in the United States, affecting millions of people. Its economic burden is estimated to be more than $200 billion, with a large contingent consisting of direct medical cost and suicide-related costs.1 MDD is often recurrent—60% of patients experience another episode within 5 years.2 Most of these patients are classified as having treatment-resistant depression (TRD), which typically is defined as the failure to respond to 2 different medications given at adequate doses for a sufficient duration.3 The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial suggested that after each medication failure, depression becomes increasingly difficult to treat, with many patients developing TRD.4 For some patients with TRD, MAOIs may be a powerful and beneficial option.5,6 Studies have shown that MAOIs (at adequate doses) can be effective in approximately one-half of patients with TRD. Patients with anxious, endogenous, or atypical depression may also respond to MAOIs.7

MAOIs were among the earliest antidepressants on the market, starting in the late 1950s with isocarboxazid, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, and selegiline. The use of MAOIs as a treatment for depression was serendipitously discovered when iproniazid, a tuberculosis drug, was observed to have mood-elevating adverse effects that were explained by its monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitory properties.8 This sparked the hypothesis that a deficiency in serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine played a central role in depressive disorders. MAOs encompass a class of enzymes that metabolize catecholamines, which include the previously mentioned neurotransmitters and the trace amine tyramine. The MAO isoenzymes also inhabit many tissues, including the central and peripheral nervous system, liver, and intestines.

There are 2 subtypes of MAOs: MAO-A and MAO-B. MAO-A inhibits tyramine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. MAO-B is mainly responsible for the degradation of dopamine, which makes MAO-B inhibitors (ie, rasagiline) useful in treating Parkinson disease.9

Continue to: For most psychiatrists...

For most psychiatrists, MAOIs have fallen out of favor due to their discomfort with their potential adverse effects and drug-drug interactions, the dietary restrictions patients must face, and the perception that newer medications have fewer adverse effects.10 Prescribing an MAOI requires the clinician to remain vigilant of any new medication the patient is taking that may potentiate intrasynaptic serotonin, which may include certain antibiotics or analgesics, causing serotonin syndrome. Close monitoring of the patient’s diet also is necessary so the patient avoids foods rich in tyramine that may trigger a hypertensive crisis. This is because excess tyramine can precipitate an increase in catecholamine release, causing a dangerous increase in blood pressure. However, many foods have safe levels of tyramine (<6 mg/serving), although the perception of tyramine levels in modern foods remains overestimated.5

Residents need to know how to use MAOIs

Psychiatrists should weigh the risks and benefits prior to prescribing any new medication, and MAOIs should be no exception. A patient’s enduring pain is often overshadowed by the potential for adverse effects, which occasionally is overemphasized. Other treatments for severe psychiatric illnesses (such as lithium and clozapine) are also declining due to these agents’ requirement for cumbersome monitoring and potential for adverse effects despite evidence of their superior efficacy and antisuicidal properties.11,12

Fortunately, there are many novel therapies available that can be effective for patients with TRD, including transcranial magnetic stimulation, ketamine, and vagal nerve stimulation. However, as psychiatrists, especially during training, our armamentarium should be equipped with all modalities of psychopharmacology. Training and teaching residents to prescribe MAOIs safely and effectively may add a glimmer of hope for an otherwise hopeless patient.

1. Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(6):653-665.

2. Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R, et al. Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(3):184-191.

3. Gaynes BN, Lux L, Gartlehner G, et al. Defining treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(2):134-145.

4. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

5. Fiedorowicz JG, Swartz KL. The role of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in current psychiatric practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(4):239-248.

6. Amsterdam JD, Shults J. MAOI efficacy and safety in advanced stage treatment-resistant depression--a retrospective study. J Affect Disord. 2005;89(1-3):183-188.

7. Amsterdam JD, Hornig-Rohan M. Treatment algorithms in treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19(2):371-386.

8. Ramachandraih CT, Subramanyam N, Bar KJ, et al. Antidepressants: from MAOIs to SSRIs and more. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53(2):180-182.

9. Tipton KF. 90 years of monoamine oxidase: some progress and some confusion. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2018;125(11):1519-1551.

10. Gillman PK, Feinberg SS, Fochtmann LJ. Revitalizing monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a call for action. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(4):452-454.

11. Kelly DL, Wehring HJ, Vyas G. Current status of clozapine in the United States. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2012;24(2):110-113.

12. Tibrewal P, Ng T, Bastiampillai T, et al. Why is lithium use declining? Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;43:219-220.

What else can I offer this patient?

This thought passed through my mind as the patient’s desperation grew palpable. He had experienced intractable major depressive disorder (MDD) for years and had exhausted multiple classes of antidepressants, trying various combinations without any relief.

The previous resident had arranged for intranasal ketamine treatment, but the patient was unable to receive it due to lack of transportation. As I combed through the list of the dozens of medications the patient previously had been prescribed, I noticed the absence of a certain class of agents: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

My knowledge of MAOIs stemmed from medical school, where the dietary restrictions, potential for hypertensive crisis, and capricious drug-drug interactions were heavily emphasized while their value was minimized. I did not have any practical experience with these medications, and even the attending physician disclosed he had not prescribed an MAOI in more than 30 years. Nonetheless, both the attending physician and patient agreed that the patient would try one.

Following a washout period, the patient began tranylcypromine. After taking tranylcypromine 40 mg/d for 3 months, he reported he felt like a weight had been lifted off his chest. He felt less irritable and depressed, more energetic, and more hopeful for the future. He also felt that his symptoms were improving for the first time in many years.

An older but still potentially helpful class of medications

MDD is one of the leading causes of disability in the United States, affecting millions of people. Its economic burden is estimated to be more than $200 billion, with a large contingent consisting of direct medical cost and suicide-related costs.1 MDD is often recurrent—60% of patients experience another episode within 5 years.2 Most of these patients are classified as having treatment-resistant depression (TRD), which typically is defined as the failure to respond to 2 different medications given at adequate doses for a sufficient duration.3 The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial suggested that after each medication failure, depression becomes increasingly difficult to treat, with many patients developing TRD.4 For some patients with TRD, MAOIs may be a powerful and beneficial option.5,6 Studies have shown that MAOIs (at adequate doses) can be effective in approximately one-half of patients with TRD. Patients with anxious, endogenous, or atypical depression may also respond to MAOIs.7

MAOIs were among the earliest antidepressants on the market, starting in the late 1950s with isocarboxazid, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, and selegiline. The use of MAOIs as a treatment for depression was serendipitously discovered when iproniazid, a tuberculosis drug, was observed to have mood-elevating adverse effects that were explained by its monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitory properties.8 This sparked the hypothesis that a deficiency in serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine played a central role in depressive disorders. MAOs encompass a class of enzymes that metabolize catecholamines, which include the previously mentioned neurotransmitters and the trace amine tyramine. The MAO isoenzymes also inhabit many tissues, including the central and peripheral nervous system, liver, and intestines.

There are 2 subtypes of MAOs: MAO-A and MAO-B. MAO-A inhibits tyramine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. MAO-B is mainly responsible for the degradation of dopamine, which makes MAO-B inhibitors (ie, rasagiline) useful in treating Parkinson disease.9

Continue to: For most psychiatrists...

For most psychiatrists, MAOIs have fallen out of favor due to their discomfort with their potential adverse effects and drug-drug interactions, the dietary restrictions patients must face, and the perception that newer medications have fewer adverse effects.10 Prescribing an MAOI requires the clinician to remain vigilant of any new medication the patient is taking that may potentiate intrasynaptic serotonin, which may include certain antibiotics or analgesics, causing serotonin syndrome. Close monitoring of the patient’s diet also is necessary so the patient avoids foods rich in tyramine that may trigger a hypertensive crisis. This is because excess tyramine can precipitate an increase in catecholamine release, causing a dangerous increase in blood pressure. However, many foods have safe levels of tyramine (<6 mg/serving), although the perception of tyramine levels in modern foods remains overestimated.5

Residents need to know how to use MAOIs

Psychiatrists should weigh the risks and benefits prior to prescribing any new medication, and MAOIs should be no exception. A patient’s enduring pain is often overshadowed by the potential for adverse effects, which occasionally is overemphasized. Other treatments for severe psychiatric illnesses (such as lithium and clozapine) are also declining due to these agents’ requirement for cumbersome monitoring and potential for adverse effects despite evidence of their superior efficacy and antisuicidal properties.11,12

Fortunately, there are many novel therapies available that can be effective for patients with TRD, including transcranial magnetic stimulation, ketamine, and vagal nerve stimulation. However, as psychiatrists, especially during training, our armamentarium should be equipped with all modalities of psychopharmacology. Training and teaching residents to prescribe MAOIs safely and effectively may add a glimmer of hope for an otherwise hopeless patient.

What else can I offer this patient?

This thought passed through my mind as the patient’s desperation grew palpable. He had experienced intractable major depressive disorder (MDD) for years and had exhausted multiple classes of antidepressants, trying various combinations without any relief.

The previous resident had arranged for intranasal ketamine treatment, but the patient was unable to receive it due to lack of transportation. As I combed through the list of the dozens of medications the patient previously had been prescribed, I noticed the absence of a certain class of agents: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

My knowledge of MAOIs stemmed from medical school, where the dietary restrictions, potential for hypertensive crisis, and capricious drug-drug interactions were heavily emphasized while their value was minimized. I did not have any practical experience with these medications, and even the attending physician disclosed he had not prescribed an MAOI in more than 30 years. Nonetheless, both the attending physician and patient agreed that the patient would try one.

Following a washout period, the patient began tranylcypromine. After taking tranylcypromine 40 mg/d for 3 months, he reported he felt like a weight had been lifted off his chest. He felt less irritable and depressed, more energetic, and more hopeful for the future. He also felt that his symptoms were improving for the first time in many years.

An older but still potentially helpful class of medications

MDD is one of the leading causes of disability in the United States, affecting millions of people. Its economic burden is estimated to be more than $200 billion, with a large contingent consisting of direct medical cost and suicide-related costs.1 MDD is often recurrent—60% of patients experience another episode within 5 years.2 Most of these patients are classified as having treatment-resistant depression (TRD), which typically is defined as the failure to respond to 2 different medications given at adequate doses for a sufficient duration.3 The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial suggested that after each medication failure, depression becomes increasingly difficult to treat, with many patients developing TRD.4 For some patients with TRD, MAOIs may be a powerful and beneficial option.5,6 Studies have shown that MAOIs (at adequate doses) can be effective in approximately one-half of patients with TRD. Patients with anxious, endogenous, or atypical depression may also respond to MAOIs.7

MAOIs were among the earliest antidepressants on the market, starting in the late 1950s with isocarboxazid, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, and selegiline. The use of MAOIs as a treatment for depression was serendipitously discovered when iproniazid, a tuberculosis drug, was observed to have mood-elevating adverse effects that were explained by its monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitory properties.8 This sparked the hypothesis that a deficiency in serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine played a central role in depressive disorders. MAOs encompass a class of enzymes that metabolize catecholamines, which include the previously mentioned neurotransmitters and the trace amine tyramine. The MAO isoenzymes also inhabit many tissues, including the central and peripheral nervous system, liver, and intestines.

There are 2 subtypes of MAOs: MAO-A and MAO-B. MAO-A inhibits tyramine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. MAO-B is mainly responsible for the degradation of dopamine, which makes MAO-B inhibitors (ie, rasagiline) useful in treating Parkinson disease.9

Continue to: For most psychiatrists...

For most psychiatrists, MAOIs have fallen out of favor due to their discomfort with their potential adverse effects and drug-drug interactions, the dietary restrictions patients must face, and the perception that newer medications have fewer adverse effects.10 Prescribing an MAOI requires the clinician to remain vigilant of any new medication the patient is taking that may potentiate intrasynaptic serotonin, which may include certain antibiotics or analgesics, causing serotonin syndrome. Close monitoring of the patient’s diet also is necessary so the patient avoids foods rich in tyramine that may trigger a hypertensive crisis. This is because excess tyramine can precipitate an increase in catecholamine release, causing a dangerous increase in blood pressure. However, many foods have safe levels of tyramine (<6 mg/serving), although the perception of tyramine levels in modern foods remains overestimated.5

Residents need to know how to use MAOIs

Psychiatrists should weigh the risks and benefits prior to prescribing any new medication, and MAOIs should be no exception. A patient’s enduring pain is often overshadowed by the potential for adverse effects, which occasionally is overemphasized. Other treatments for severe psychiatric illnesses (such as lithium and clozapine) are also declining due to these agents’ requirement for cumbersome monitoring and potential for adverse effects despite evidence of their superior efficacy and antisuicidal properties.11,12

Fortunately, there are many novel therapies available that can be effective for patients with TRD, including transcranial magnetic stimulation, ketamine, and vagal nerve stimulation. However, as psychiatrists, especially during training, our armamentarium should be equipped with all modalities of psychopharmacology. Training and teaching residents to prescribe MAOIs safely and effectively may add a glimmer of hope for an otherwise hopeless patient.

1. Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(6):653-665.

2. Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R, et al. Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(3):184-191.

3. Gaynes BN, Lux L, Gartlehner G, et al. Defining treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(2):134-145.

4. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

5. Fiedorowicz JG, Swartz KL. The role of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in current psychiatric practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(4):239-248.

6. Amsterdam JD, Shults J. MAOI efficacy and safety in advanced stage treatment-resistant depression--a retrospective study. J Affect Disord. 2005;89(1-3):183-188.

7. Amsterdam JD, Hornig-Rohan M. Treatment algorithms in treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19(2):371-386.

8. Ramachandraih CT, Subramanyam N, Bar KJ, et al. Antidepressants: from MAOIs to SSRIs and more. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53(2):180-182.

9. Tipton KF. 90 years of monoamine oxidase: some progress and some confusion. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2018;125(11):1519-1551.

10. Gillman PK, Feinberg SS, Fochtmann LJ. Revitalizing monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a call for action. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(4):452-454.

11. Kelly DL, Wehring HJ, Vyas G. Current status of clozapine in the United States. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2012;24(2):110-113.

12. Tibrewal P, Ng T, Bastiampillai T, et al. Why is lithium use declining? Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;43:219-220.

1. Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(6):653-665.

2. Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R, et al. Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(3):184-191.

3. Gaynes BN, Lux L, Gartlehner G, et al. Defining treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(2):134-145.

4. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

5. Fiedorowicz JG, Swartz KL. The role of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in current psychiatric practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(4):239-248.

6. Amsterdam JD, Shults J. MAOI efficacy and safety in advanced stage treatment-resistant depression--a retrospective study. J Affect Disord. 2005;89(1-3):183-188.

7. Amsterdam JD, Hornig-Rohan M. Treatment algorithms in treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19(2):371-386.

8. Ramachandraih CT, Subramanyam N, Bar KJ, et al. Antidepressants: from MAOIs to SSRIs and more. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53(2):180-182.

9. Tipton KF. 90 years of monoamine oxidase: some progress and some confusion. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2018;125(11):1519-1551.

10. Gillman PK, Feinberg SS, Fochtmann LJ. Revitalizing monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a call for action. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(4):452-454.

11. Kelly DL, Wehring HJ, Vyas G. Current status of clozapine in the United States. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2012;24(2):110-113.

12. Tibrewal P, Ng T, Bastiampillai T, et al. Why is lithium use declining? Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;43:219-220.

What my Grandma’s schizophrenia taught me

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Grandma was sitting in her chair in the corner of the living room, and her eyes were wide, filled with fear and suspicion as she glanced between me, Mom, and Papa. “They are out to get me,” she said, slightly frantic. She glanced down at her right hand, fixated on a spot on the dorsum. Gingerly lifting her arm, she angled her hand toward my mom’s face. “You see that? They have been conducting experiments on me. I AM THE QUEEN,” she sobbed, “and you are planning together” she said, directing her attention to Papa and me. In that moment, Grandma was convinced Papa and I were conspiring to assassinate her. It hurt to see my grandmother look at me with genuine fear in her eyes. It was overwhelming to watch her deteriorate from the person I had been accustomed to for most of my life to the paranoid individual shaking in front of me.

This was the first time I had really observed my grandmother experiencing acute psychosis. My mom explained to me at a young age that my grandmother had an illness in her mind. I noticed that compared to other people in my life, my grandmother seemed to express less emotion and changed topics in conversations frequently, but by having an understanding provided by my mother, my brother and I didn’t think much of it; that was just Grandma. She would occasionally talk about her experiences with hearing voices or people on the television talking about her. For the most part, though, she was stable; she was able to carry out cleaning, cooking, and watching her favorite shows.

That was until she turned 65 and started on Medicare for insurance. The government required her to trial a less expensive medication and wanted her family practitioner to adjust the medications she had been on for years. This decision was made by people unfamiliar with my grandmother and her story. As a result, my family struggled alongside Grandma for over a month as she battled hallucinations and labile emotions. Living in rural Ohio, she had no access to a psychiatrist or other mental health professional during this period. The adjustments to her medications, changes in her insurance coverage, and lack of consistent psychiatric care led to a deterioration of her stability. This was the only time in my life that I saw Grandma at a place where she would have needed to be hospitalized if the symptoms lasted much longer. I spent evenings sitting with her in that dark and scary place, listening, sympathizing, and challenging her distortions of reality. This experience laid the foundation for my growing passion for providing care and advocating for people experiencing mental illness. I observed firsthand how the absence of consistent, compassionate, and informed care could lead to psychiatric hospitalization.

In the past, my grandfather hid my grandmother’s diagnosis from those around them. This approach prevented my uncle from disclosing the same information to my cousins. I observed how they would look at her with confusion and sometimes fear, which was rooted in a lack of understanding. This desire to hide Grandma’s schizophrenia stemmed from the marginalization society imposed upon her. There were sneers, comments regarding lack of religious faith, and expressions that she was not trying hard enough. My grandparents decided together to inform their church of my grandmother’s illness. The results were astounding. People looked at my grandmother not with confusion but with sympathy and would go out of their way to check on her. Knowledge is power, and awareness can break down stigma. Seeing the difference knowledge could have on a church community further solidified my desire to educate not only patients and their family members but also communities.

Access is another huge barrier my grandmother has faced. There is a lack of referring and awareness as well as large geographic disparities of psychiatrists around my hometown. My grandmother has also had struggles with being able to pay for services, medication, and therapy. This shows the desperate need for more mental health professionals who are competent and knowledgeable in how social determinants of health impact outcomes. These factors contributed to my decision to pursue a Master of Public Health degree. I aspire to use this background to prevent what happened to my Grandma from happening to other patients and to be an advocate for enhanced access to services, improving community mental health and awareness, and promoting continuity of care to increase treatment compliance. That is what my Grandma has fostered in me as a future psychiatrist.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Grandma was sitting in her chair in the corner of the living room, and her eyes were wide, filled with fear and suspicion as she glanced between me, Mom, and Papa. “They are out to get me,” she said, slightly frantic. She glanced down at her right hand, fixated on a spot on the dorsum. Gingerly lifting her arm, she angled her hand toward my mom’s face. “You see that? They have been conducting experiments on me. I AM THE QUEEN,” she sobbed, “and you are planning together” she said, directing her attention to Papa and me. In that moment, Grandma was convinced Papa and I were conspiring to assassinate her. It hurt to see my grandmother look at me with genuine fear in her eyes. It was overwhelming to watch her deteriorate from the person I had been accustomed to for most of my life to the paranoid individual shaking in front of me.

This was the first time I had really observed my grandmother experiencing acute psychosis. My mom explained to me at a young age that my grandmother had an illness in her mind. I noticed that compared to other people in my life, my grandmother seemed to express less emotion and changed topics in conversations frequently, but by having an understanding provided by my mother, my brother and I didn’t think much of it; that was just Grandma. She would occasionally talk about her experiences with hearing voices or people on the television talking about her. For the most part, though, she was stable; she was able to carry out cleaning, cooking, and watching her favorite shows.

That was until she turned 65 and started on Medicare for insurance. The government required her to trial a less expensive medication and wanted her family practitioner to adjust the medications she had been on for years. This decision was made by people unfamiliar with my grandmother and her story. As a result, my family struggled alongside Grandma for over a month as she battled hallucinations and labile emotions. Living in rural Ohio, she had no access to a psychiatrist or other mental health professional during this period. The adjustments to her medications, changes in her insurance coverage, and lack of consistent psychiatric care led to a deterioration of her stability. This was the only time in my life that I saw Grandma at a place where she would have needed to be hospitalized if the symptoms lasted much longer. I spent evenings sitting with her in that dark and scary place, listening, sympathizing, and challenging her distortions of reality. This experience laid the foundation for my growing passion for providing care and advocating for people experiencing mental illness. I observed firsthand how the absence of consistent, compassionate, and informed care could lead to psychiatric hospitalization.

In the past, my grandfather hid my grandmother’s diagnosis from those around them. This approach prevented my uncle from disclosing the same information to my cousins. I observed how they would look at her with confusion and sometimes fear, which was rooted in a lack of understanding. This desire to hide Grandma’s schizophrenia stemmed from the marginalization society imposed upon her. There were sneers, comments regarding lack of religious faith, and expressions that she was not trying hard enough. My grandparents decided together to inform their church of my grandmother’s illness. The results were astounding. People looked at my grandmother not with confusion but with sympathy and would go out of their way to check on her. Knowledge is power, and awareness can break down stigma. Seeing the difference knowledge could have on a church community further solidified my desire to educate not only patients and their family members but also communities.

Access is another huge barrier my grandmother has faced. There is a lack of referring and awareness as well as large geographic disparities of psychiatrists around my hometown. My grandmother has also had struggles with being able to pay for services, medication, and therapy. This shows the desperate need for more mental health professionals who are competent and knowledgeable in how social determinants of health impact outcomes. These factors contributed to my decision to pursue a Master of Public Health degree. I aspire to use this background to prevent what happened to my Grandma from happening to other patients and to be an advocate for enhanced access to services, improving community mental health and awareness, and promoting continuity of care to increase treatment compliance. That is what my Grandma has fostered in me as a future psychiatrist.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Grandma was sitting in her chair in the corner of the living room, and her eyes were wide, filled with fear and suspicion as she glanced between me, Mom, and Papa. “They are out to get me,” she said, slightly frantic. She glanced down at her right hand, fixated on a spot on the dorsum. Gingerly lifting her arm, she angled her hand toward my mom’s face. “You see that? They have been conducting experiments on me. I AM THE QUEEN,” she sobbed, “and you are planning together” she said, directing her attention to Papa and me. In that moment, Grandma was convinced Papa and I were conspiring to assassinate her. It hurt to see my grandmother look at me with genuine fear in her eyes. It was overwhelming to watch her deteriorate from the person I had been accustomed to for most of my life to the paranoid individual shaking in front of me.

This was the first time I had really observed my grandmother experiencing acute psychosis. My mom explained to me at a young age that my grandmother had an illness in her mind. I noticed that compared to other people in my life, my grandmother seemed to express less emotion and changed topics in conversations frequently, but by having an understanding provided by my mother, my brother and I didn’t think much of it; that was just Grandma. She would occasionally talk about her experiences with hearing voices or people on the television talking about her. For the most part, though, she was stable; she was able to carry out cleaning, cooking, and watching her favorite shows.

That was until she turned 65 and started on Medicare for insurance. The government required her to trial a less expensive medication and wanted her family practitioner to adjust the medications she had been on for years. This decision was made by people unfamiliar with my grandmother and her story. As a result, my family struggled alongside Grandma for over a month as she battled hallucinations and labile emotions. Living in rural Ohio, she had no access to a psychiatrist or other mental health professional during this period. The adjustments to her medications, changes in her insurance coverage, and lack of consistent psychiatric care led to a deterioration of her stability. This was the only time in my life that I saw Grandma at a place where she would have needed to be hospitalized if the symptoms lasted much longer. I spent evenings sitting with her in that dark and scary place, listening, sympathizing, and challenging her distortions of reality. This experience laid the foundation for my growing passion for providing care and advocating for people experiencing mental illness. I observed firsthand how the absence of consistent, compassionate, and informed care could lead to psychiatric hospitalization.

In the past, my grandfather hid my grandmother’s diagnosis from those around them. This approach prevented my uncle from disclosing the same information to my cousins. I observed how they would look at her with confusion and sometimes fear, which was rooted in a lack of understanding. This desire to hide Grandma’s schizophrenia stemmed from the marginalization society imposed upon her. There were sneers, comments regarding lack of religious faith, and expressions that she was not trying hard enough. My grandparents decided together to inform their church of my grandmother’s illness. The results were astounding. People looked at my grandmother not with confusion but with sympathy and would go out of their way to check on her. Knowledge is power, and awareness can break down stigma. Seeing the difference knowledge could have on a church community further solidified my desire to educate not only patients and their family members but also communities.

Access is another huge barrier my grandmother has faced. There is a lack of referring and awareness as well as large geographic disparities of psychiatrists around my hometown. My grandmother has also had struggles with being able to pay for services, medication, and therapy. This shows the desperate need for more mental health professionals who are competent and knowledgeable in how social determinants of health impact outcomes. These factors contributed to my decision to pursue a Master of Public Health degree. I aspire to use this background to prevent what happened to my Grandma from happening to other patients and to be an advocate for enhanced access to services, improving community mental health and awareness, and promoting continuity of care to increase treatment compliance. That is what my Grandma has fostered in me as a future psychiatrist.

Emergency contraception for psychiatric patients

Ms. A, age 22, is a college student who presents for an initial psychiatric evaluation. Her body mass index (BMI) is 20 (normal range: 18.5 to 24.9), and her medical history is positive only for childhood asthma. She has been treated for major depressive disorder with venlafaxine by her previous psychiatrist. While this antidepressant has been effective for some symptoms, she has experienced adverse effects and is interested in a different medication. During the evaluation, Ms. A remarks that she had a “scare” last night when the condom broke while having sex with her boyfriend. She says that she is interested in having children at some point, but not at present; she is concerned that getting pregnant now would cause her depression to “spiral out of control.”

Unwanted or mistimed pregnancies account for 45% of all pregnancies.1 While there are ramifications for any unintended pregnancy, the risks for patients with mental illness are greater and include potential adverse effects on the neonate from both psychiatric disease and psychiatric medication use, worse obstetrical outcomes for patients with untreated mental illness, and worsening of psychiatric symptoms and suicide risk in the peripartum period.2 These risks become even more pronounced when psychiatric medications are reflexively discontinued or reduced in pregnancy, which is commonly done contrary to best practice recommendations. In the United States, the recent Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization has erased federal protections for abortion previously conferred by Roe v Wade. As a result, as of early October 2022, abortion had been made illegal in 11 states, and was likely to be banned in many others, most commonly in states where there is limited support for either parents or children. Thus, preventing unplanned pregnancies should be a treatment consideration for all medical disciplines.3

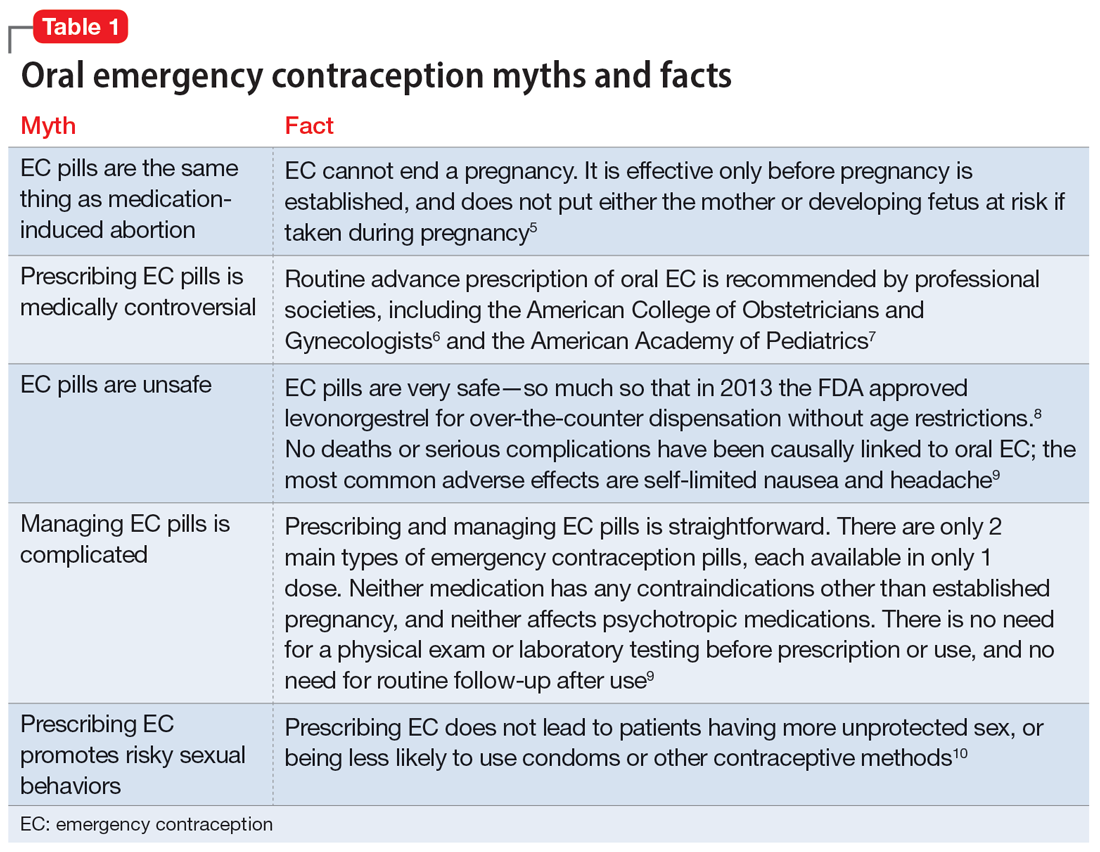

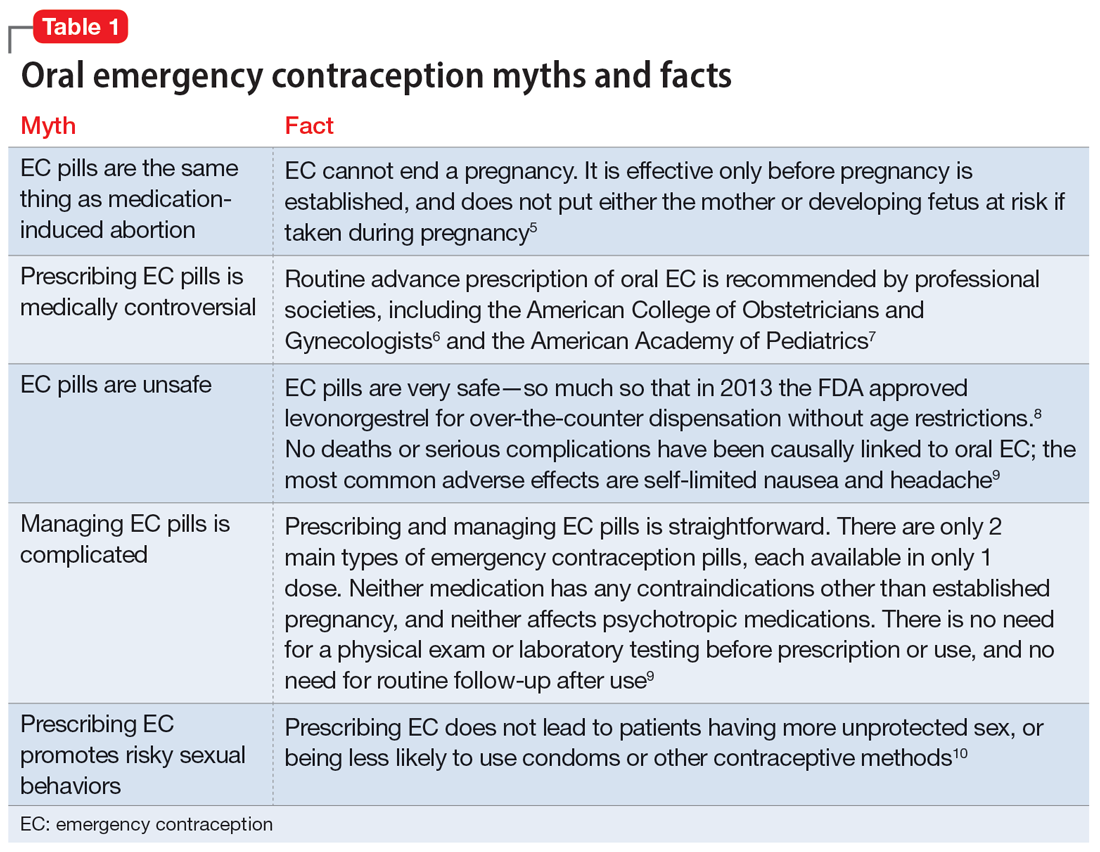

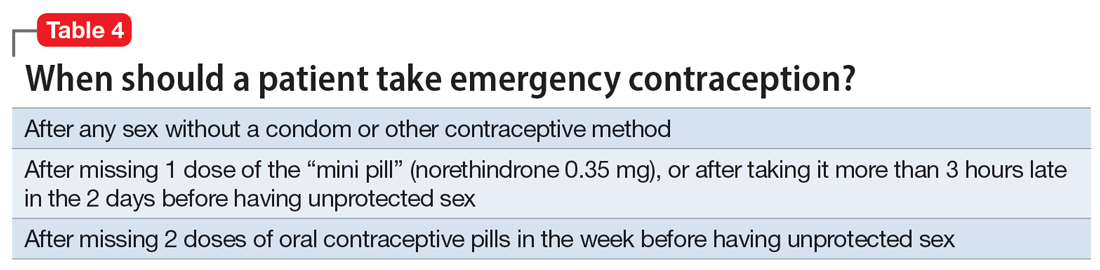

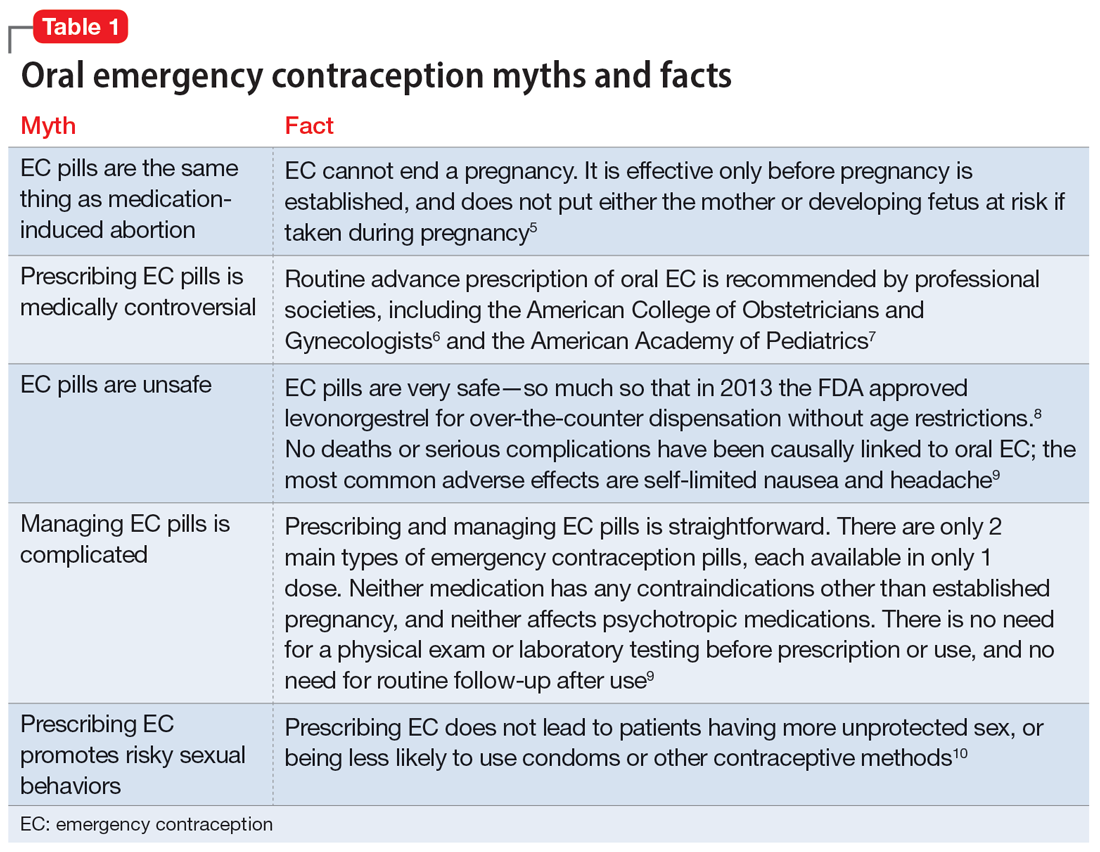

Psychiatrists may hesitate to prescribe emergency contraception (EC) due to fears it falls outside the scope of their practice. However, psychiatry has already moved towards prescribing nonpsychiatric medications when doing so clearly benefits the patient. One example is prescribing metformin to address metabolic syndrome related to the use of second-generation antipsychotics. Emergency contraceptives have strong safety profiles and are easy to prescribe. Unfortunately, there are many barriers to increasing access to emergency contraceptives for psychiatric patients.4 These include the erroneous belief that laboratory and physical exams are needed before starting EC, cost and/or limited stock of emergency contraceptives at pharmacies, and general confusion regarding what constitutes EC vs an oral abortive (Table 15-10). Psychiatrists are particularly well-positioned to support the reproductive autonomy and well-being of patients who struggle to engage with other clinicians. This article aims to help psychiatrists better understand EC so they can comfortably prescribe it before their patients need it.

What is emergency contraception?

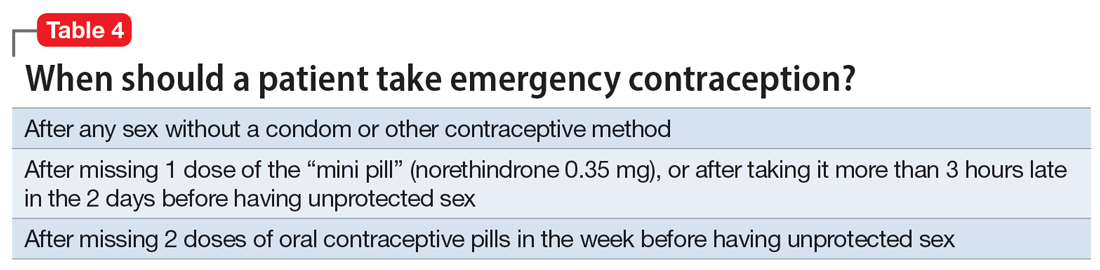

EC is medications or devices that patients can use after sexual intercourse to prevent pregnancy. They do not impede the development of an established pregnancy and thus are not abortifacients. EC is not recommended as a primary means of contraception,9 but it can be extremely valuable to reduce pregnancy risk after unprotected intercourse or contraceptive failures such as broken condoms or missed doses of birth control pills. EC can prevent ≥95% of pregnancies when taken within 5 days of at-risk intercourse.11

Methods of EC fall into 2 categories: oral medications (sometimes referred to as “morning after pills”) and intrauterine devices (IUDs). IUDs are the most effective means of EC, especially for patients with higher BMIs or who may be taking medications such as cytochrome P450 (CYP)3A4 inducers that could interfere with the effectiveness of oral methods. IUDs also have the advantage of providing highly effective ongoing contraception.6 However, IUDs require in-office placement by a trained clinician, and patients may experience difficulty obtaining placement within 5 days of unprotected sex. Therefore, oral medication is the most common form of EC.

Oral EC is safe and effective, and professional societies (including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists6 and the American Academy of Pediatrics7) recommend routinely prescribing oral EC for patients in advance of need. Advance prescribing eliminates barriers to accessing EC, increases the use of EC, and does not encourage risky sexual behaviors.10

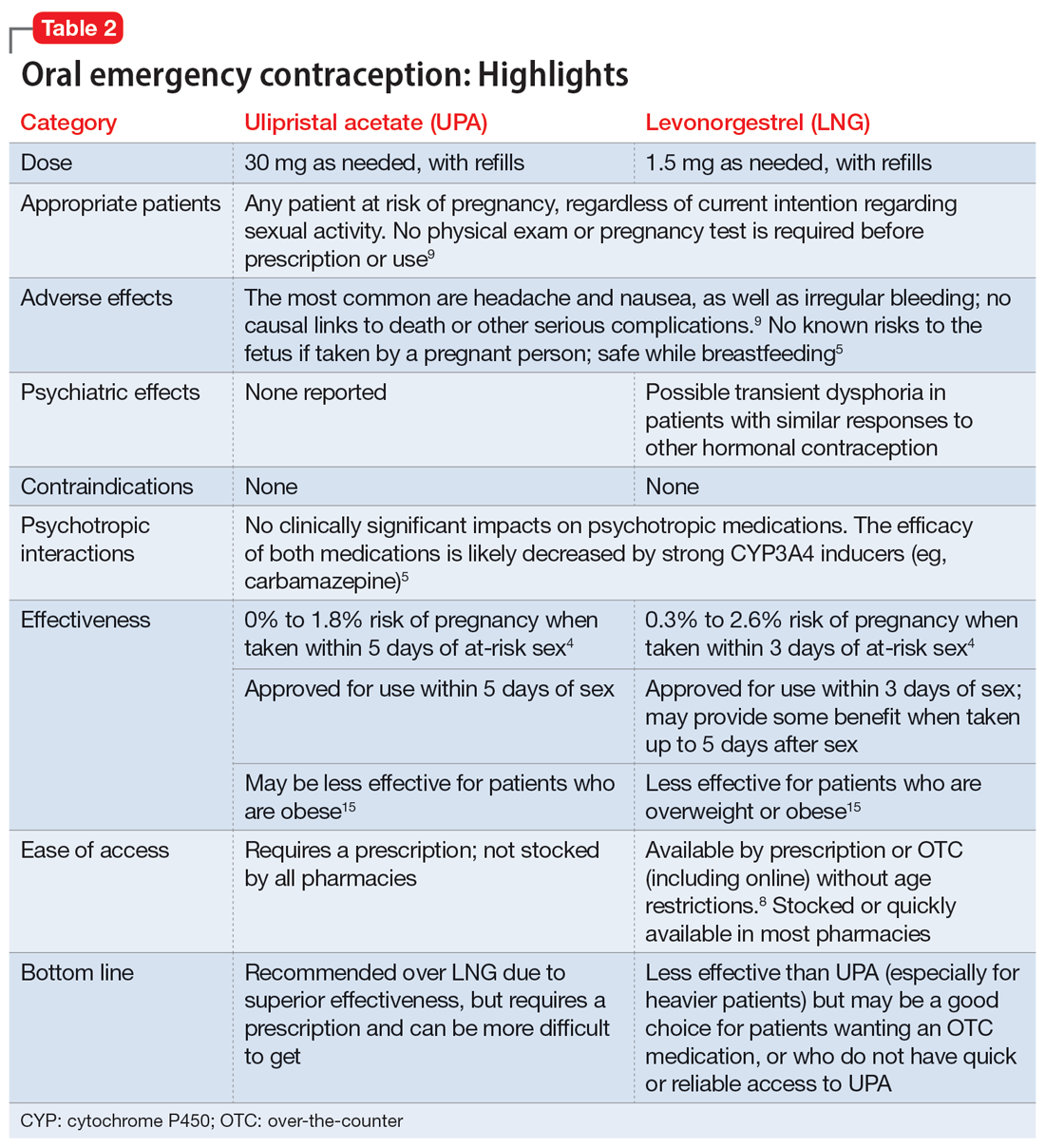

Overview of oral emergency contraception

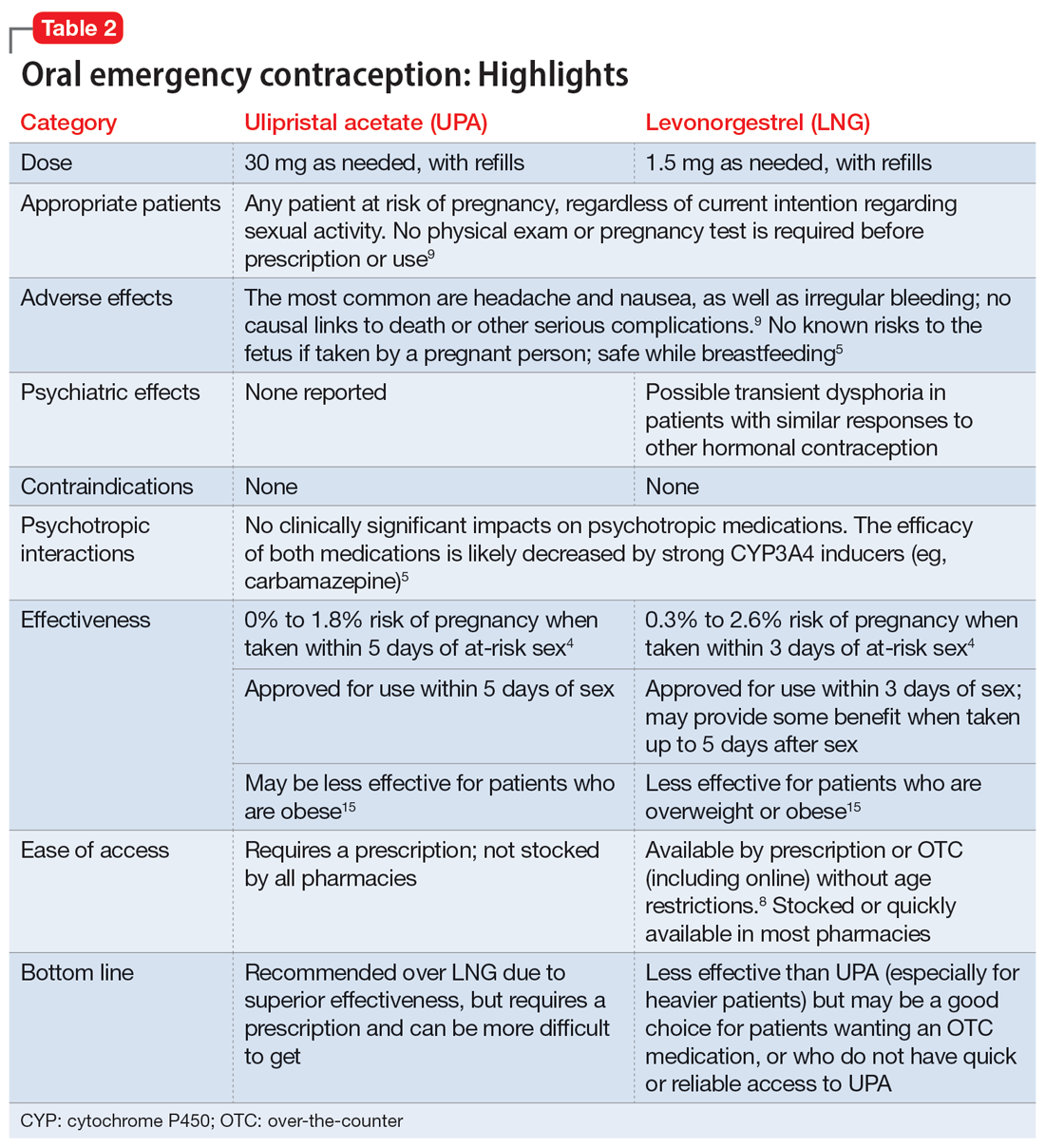

Two medications are FDA-approved for use as oral EC: ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Both are available in generic and branded versions. While many common birth control pills can also be safely used off-label as emergency contraception (an approach known as the Yuzpe method), they are less effective, not as well-tolerated, and require knowledge of the specific type of pill the patient has available.9 Oral EC appears to work primarily through delay or inhibition of ovulation, and is unlikely to prevent implantation of a fertilized egg.9

Continue to: Ulipristal acetate

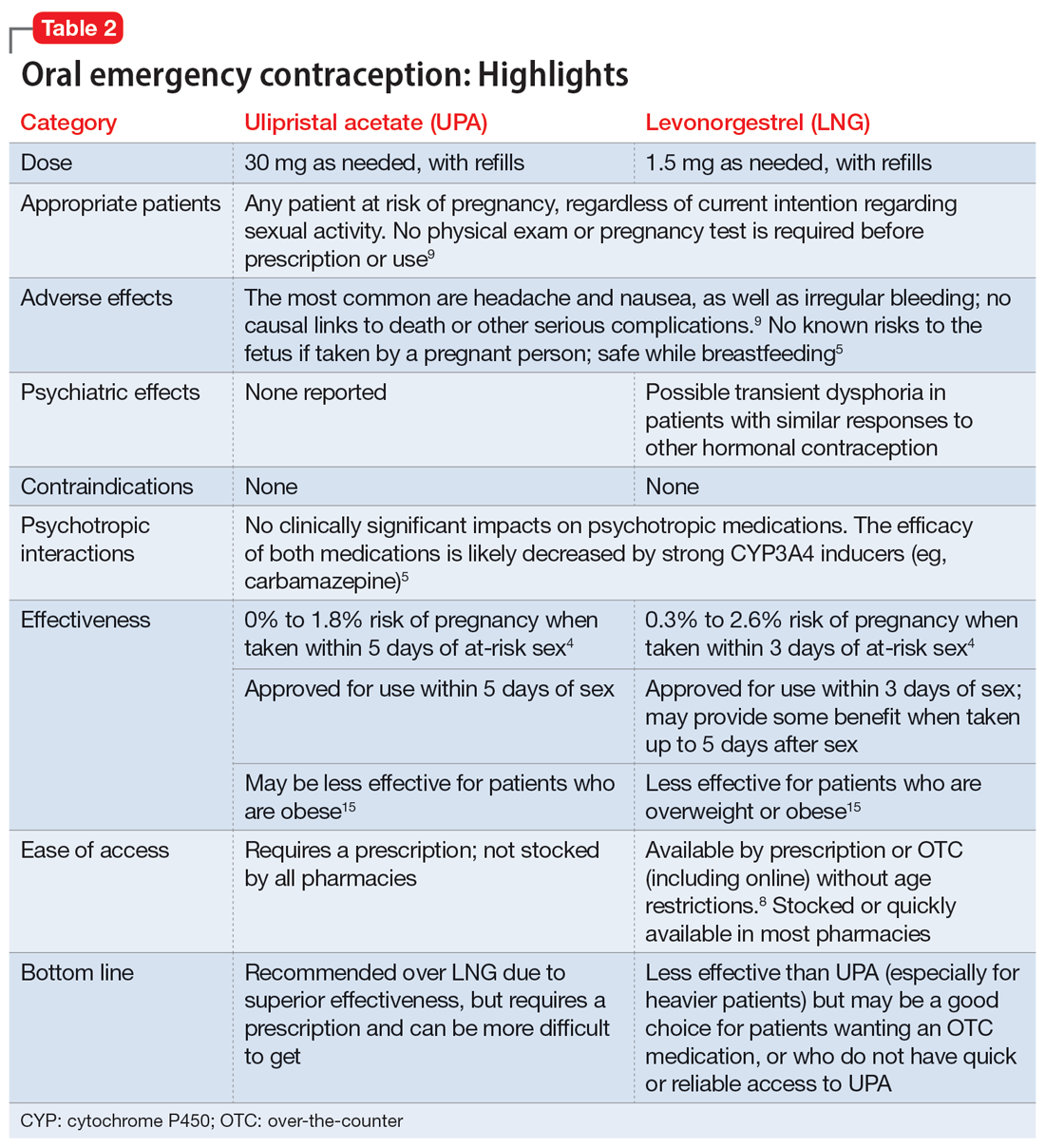

Ulipristal acetate (UPA) is an oral progesterone receptor agonist-antagonist taken as a single 30 mg dose up to 5 days after unprotected sex. Pregnancy rates from a single act of unprotected sex followed by UPA use range from 0% to 1.8%.4 Many pharmacies stock UPA, and others (especially chain pharmacies) report being able to order and fill it within 24 hours.12

Levonorgestrel (LNG) is an oral progestin that is available by prescription and has also been approved for over-the-counter sale to patients of all ages and sexes (without the need to show identification) since 2013.8 It is administered as a single 1.5 mg dose taken as soon as possible up to 3 days after unprotected sex, although it may continue to provide benefits when taken within 5 days. Pregnancy rates from a single act of unprotected sex followed by LNG use range from 0.3% to 2.6%, with much higher odds among women who are obese.4 LNG is available both by prescription or over-the-counter,13 although it is often kept in a locked cabinet or behind the counter, and staff are often misinformed regarding the lack of age restrictions for sale without a prescription.14

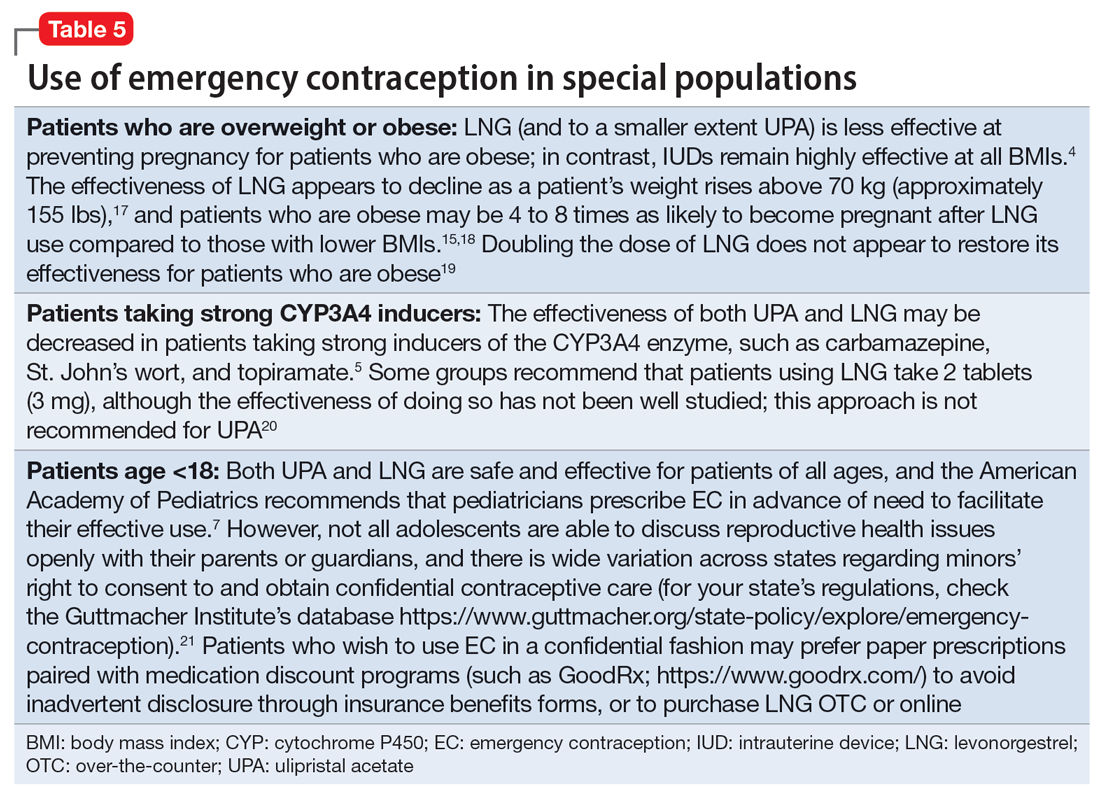

Safety and adverse effects. According to the CDC, there are no conditions for which the risks outweigh the advantages of use of either UPA or LNG,5 and patients for whom hormonal birth control is otherwise contraindicated can still use them safely. If a pregnancy has already occurred, taking EC will not harm the developing fetus; it is also safe to use when breastfeeding.5 Both medications are generally well-tolerated—neither has been causally linked to deaths or serious complications,5 and the most common adverse effects are headache (approximately 19%) and nausea (approximately 12%), in addition to irregular bleeding, fatigue, dizziness, and abdominal pain.15 Oral EC may be used more than once, even within the same menstrual cycle. Patients who use EC repeatedly should be encouraged to discuss more efficacious contraceptive options with their primary physician or gynecologist.

Will oral EC affect psychiatric treatment?

Oral EC is unlikely to have a meaningful effect on psychiatric symptoms or management, particularly when compared to the significant impacts of unintended pregnancies. Neither medication is known to have any clinically significant impacts on the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of psychotropic medications, although the effectiveness of both medications can be impaired by CYP3A4 inducers such as carbamazepine.5 In addition, while research has not specifically examined the impact of EC on psychiatric symptoms, the broader literature on hormonal contraception indicates that most patients with psychiatric disorders generally report similar or lower rates of mood symptoms associated with their use.16 Some women treated with hormonal contraceptives do develop dysphoric mood,16 but any such effects resulting from LNG would likely be transient. Mood disruptions or other psychiatric symptoms have not been associated with UPA use.

How to prescribe oral emergency contraception

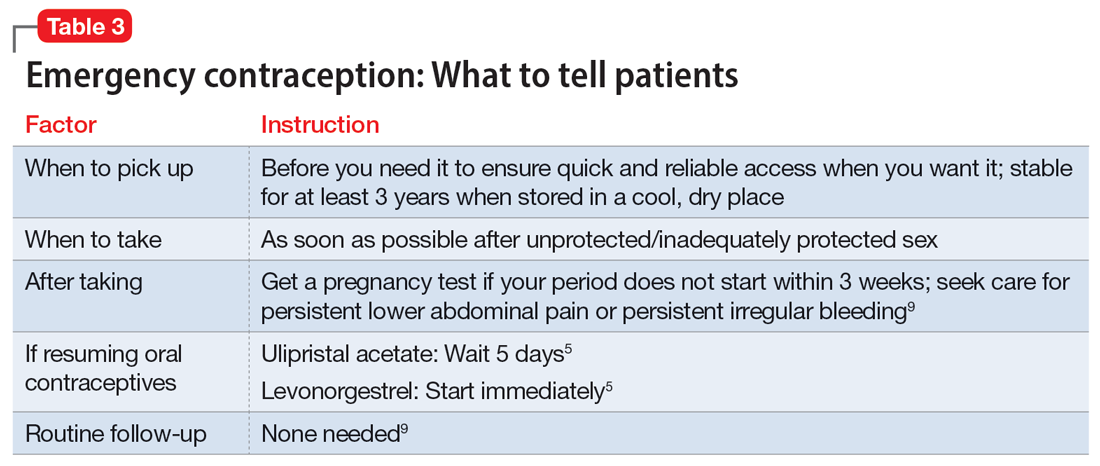

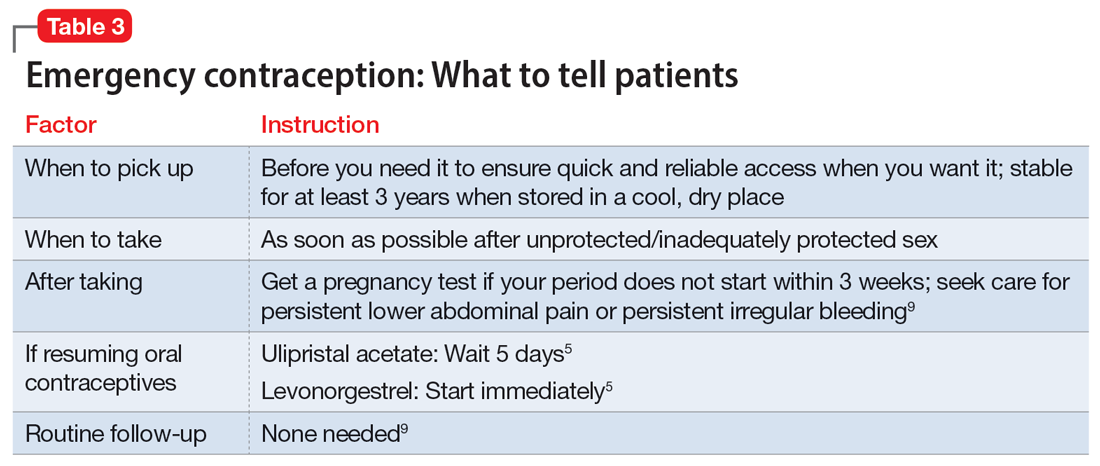

Who and when. Women of reproductive age should be counseled about EC as part of anticipatory guidance, regardless of their current intentions for sexual behaviors. Patients do not need a physical examination or pregnancy test before being prescribed or using oral EC.9 Much like how intranasal naloxone is prescribed, prescriptions should be provided in advance of need, with multiple refills to facilitate ready access when needed.

Continue to: Which to prescribe

Which to prescribe. UPA is more effective in preventing pregnancy than LNG at all time points up to 120 hours after sex, including for women who are overweight or obese.15 As such, it is recommended as the first-line choice. However, because LNG is available without prescription and is more readily available (including via online order), it may be a good choice for patients who need rapid EC or who prefer a medication that does not require a prescription (Table 24,5,8,9,15).

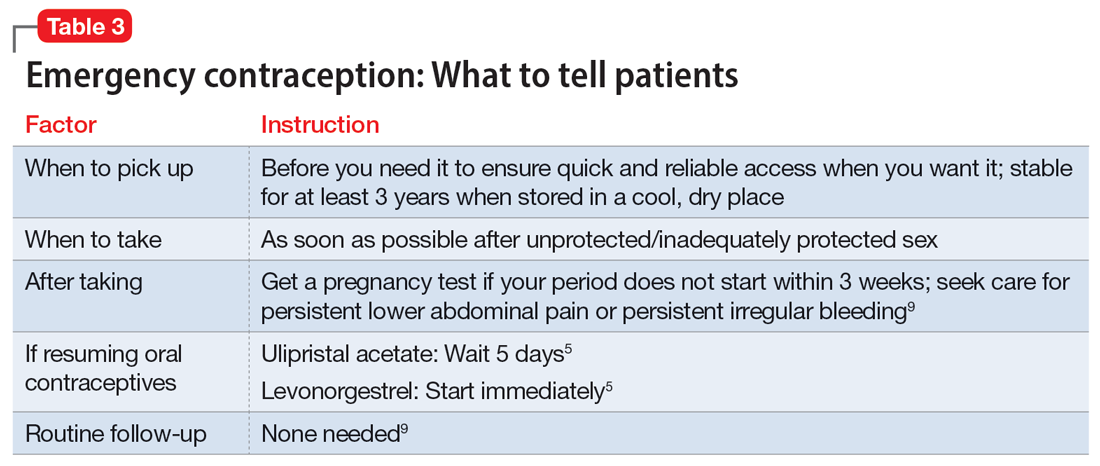

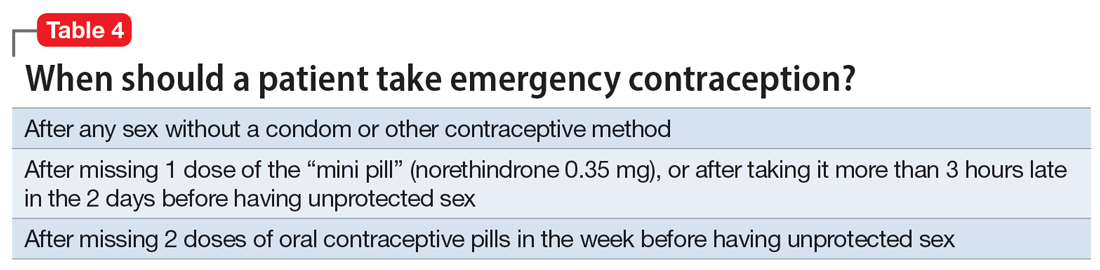

What to tell patients. Patients should be instructed to fill their prescription before they expect to use it, to ensure ready availability when desired (Table 35,9). Oral EC is shelf stable for at least 3 years when stored in a cool, dry environment. Patients should take the medication as soon as possible following at-risk sexual intercourse (Table 4). Tell them that if they vomit within 3 hours of taking the medication, they should take a second dose. Remind patients that EC does not protect against sexually transmitted infections, or from sex that occurs after the medication is taken (in fact, they can increase the possibility of pregnancy later in that menstrual cycle due to delayed ovulation).9 Counsel patients to abstain from sex or to use barrier contraception for 7 days after use. Those who take birth control pills can resume use immediately after using LNG; they should wait 5 days after taking UPA.

No routine follow-up is needed after taking UPA or LNG. However, patients should get a pregnancy test if their period does not start within 3 weeks, and should seek medical evaluation if they experience significant lower abdominal pain or persistent irregular bleeding in order to rule out pregnancy-related complications. Patients who use EC repeatedly should be recommended to pursue routine contraceptive care.

Billing. Counseling your patients about contraception can increase the reimbursement you receive by adding to the complexity of the encounter (regardless of whether you prescribe a medication) through use of the ICD-10 code Z30.0.

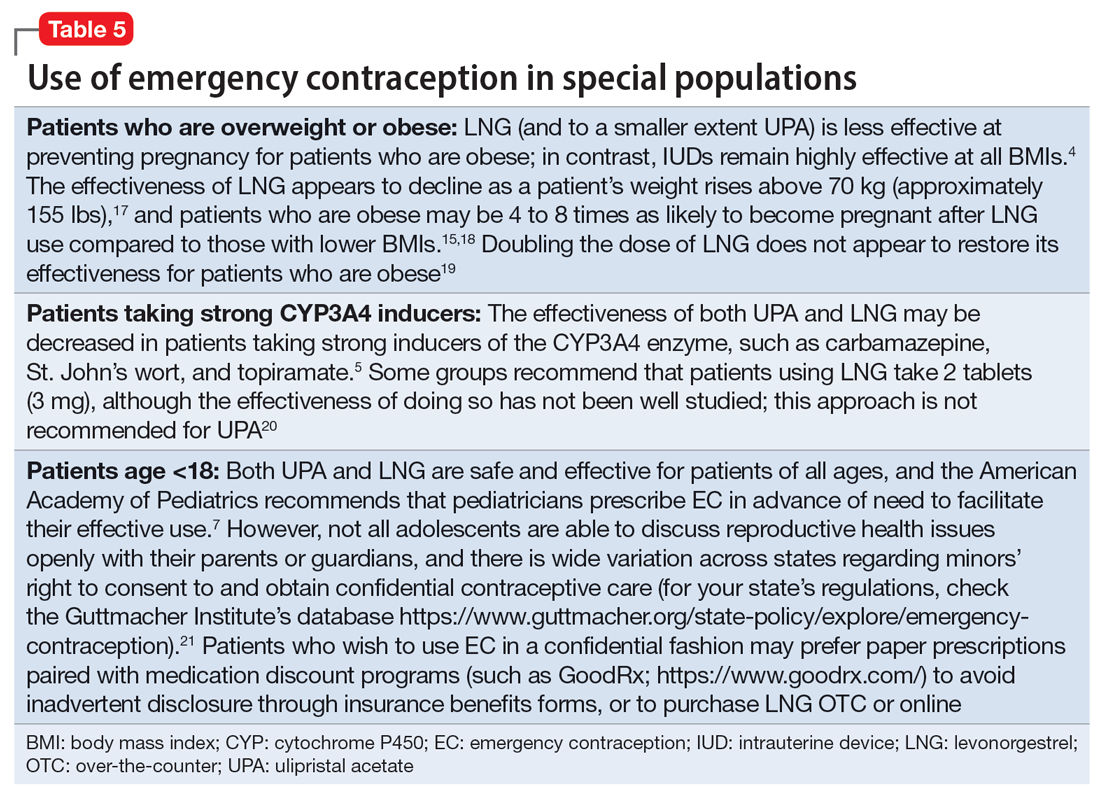

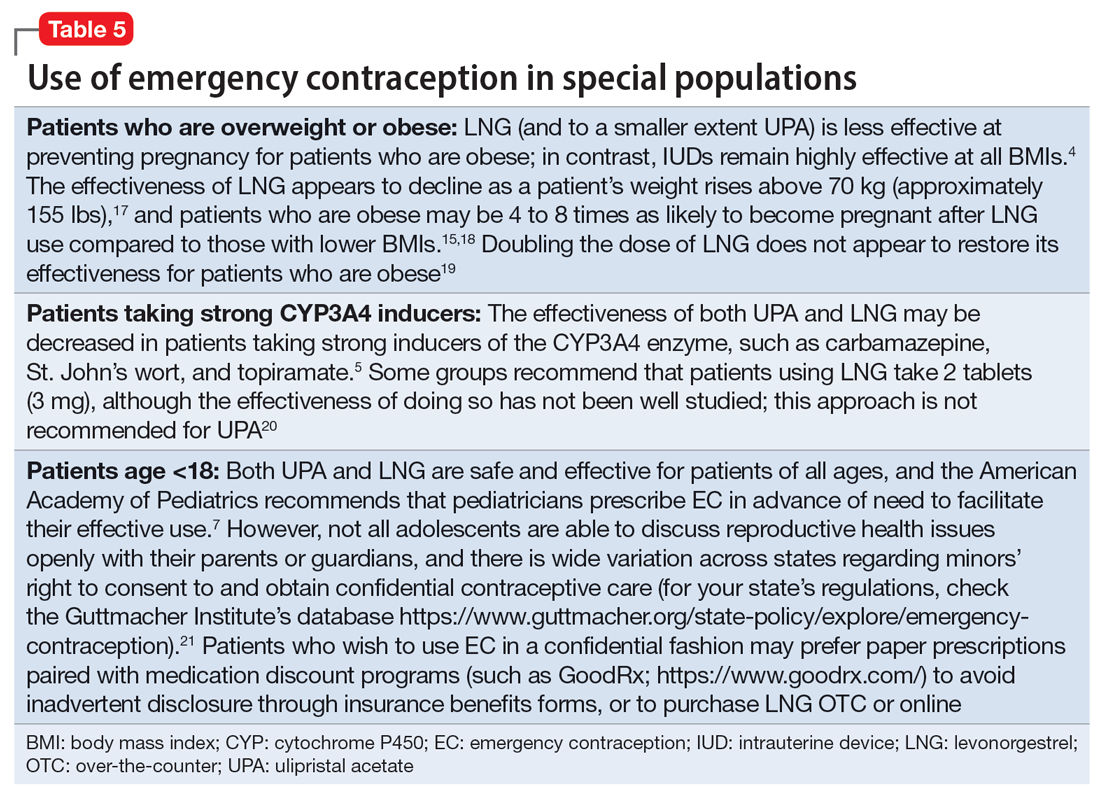

Emergency contraception for special populations

Some patients face additional challenges to effective EC that should be considered when counseling and prescribing. Table 54,5,7,15,17-21 discusses the use of EC in these special populations. Of particular importance for psychiatrists, LNG is less effective at preventing undesired pregnancy among patients who are overweight or obese,15,17,18 and strong CYP3A4-inducing agents may decrease the effectiveness of both LNG and UPA.5 Keep in mind, however, that the advantages of using either UPA or LNG outweigh the risks for all populations.5 Patients must be aware of appropriate information in order to make informed decisions, but should not be discouraged from using EC.

Continue to: Other groups of patients...

Other groups of patients may face barriers due to some clinicians’ hesitancy regarding their ability to consent to reproductive care. Most patients with psychiatric illnesses have decision-making capacity regarding reproductive issues.22 Although EC is supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics,7 patients age <18 have varying rights to consent across states,21 and merit special consideration.

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. A does not wish to get pregnant at this time, and expresses fears that her recent contraceptive failure could lead to an unintended pregnancy. In addition to her psychiatric treatment, her psychiatrist should discuss EC options with her. She has a healthy BMI and had inadequately protected sex <1 day ago, so her clinician may prescribe LNG (to ensure rapid access for immediate use) in addition to UPA for her to have available in case of future “scares.” The psychiatrist should consider pharmacologic treatment with an antidepressant with a relatively safe reproductive record (eg, sertraline).23 This is considered preventive ethics, since Ms. A is of reproductive age, even if she is not presently planning to get pregnant, due to the aforementioned high rate of unplanned pregnancy.23,24 It is also important for the psychiatrist to continue the dialogue in future sessions about preventing unintended pregnancy. Since Ms. A has benefited from a psychotropic medication when not pregnant, it will be important to discuss with her the risks and benefits of medication should she plan a pregnancy.

Bottom Line

Patients with mental illnesses are at increased risk of adverse outcomes resulting from unintended pregnancies. Clinicians should counsel patients about emergency contraception (EC) as a part of routine psychiatric care, and should prescribe oral EC in advance of patient need to facilitate effective use.

Related Resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on Emergency Contraception. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/ articles/2015/09/emergency-contraception

- State policies on emergency contraception. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/emergency-contraception

- State policies on minors’ access to contraceptive services. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/minors-access-contraceptive-services