User login

Transplantation palliative care: The time is ripe

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

SVS Now Accepting Abstracts for VAM 2017

Abstracts for the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting are now being accepted. The submission site opened Monday, Nov. 14 for the meeting, to be held May 31 to June 3, 2017, in San Diego. Plenary sessions and exhibits will be June 1 to 3.

Participants may submit abstracts into any of 14 categories and a number of presentation types, including videos. In 2016, organizers selected approximately two-thirds of the submitted abstracts, and this year the VAM Program Committee is seeking additional venues for people to present their work in, including more sessions and other presentation formats.

Click here for abstract guidelines and more information. Abstracts themselves may be submitted here.

Abstracts for the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting are now being accepted. The submission site opened Monday, Nov. 14 for the meeting, to be held May 31 to June 3, 2017, in San Diego. Plenary sessions and exhibits will be June 1 to 3.

Participants may submit abstracts into any of 14 categories and a number of presentation types, including videos. In 2016, organizers selected approximately two-thirds of the submitted abstracts, and this year the VAM Program Committee is seeking additional venues for people to present their work in, including more sessions and other presentation formats.

Click here for abstract guidelines and more information. Abstracts themselves may be submitted here.

Abstracts for the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting are now being accepted. The submission site opened Monday, Nov. 14 for the meeting, to be held May 31 to June 3, 2017, in San Diego. Plenary sessions and exhibits will be June 1 to 3.

Participants may submit abstracts into any of 14 categories and a number of presentation types, including videos. In 2016, organizers selected approximately two-thirds of the submitted abstracts, and this year the VAM Program Committee is seeking additional venues for people to present their work in, including more sessions and other presentation formats.

Click here for abstract guidelines and more information. Abstracts themselves may be submitted here.

Best Practices: Protecting Dry Vulnerable Skin with CeraVe® Healing Ointment

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

Primary Care Clinician and Patient Knowledge, Interest, and Use of Integrative Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain Management

Primary Care Clinician and Patient Knowledge, Interest, and Use of Integrative Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain Management

More than 50 million US adults report experiencing chronic pain, with nearly 7% experiencing high-impact chronic pain.1-3 Chronic pain negatively affects daily function, results in lost productivity, is a leading cause of disability, and is more prevalent among veterans compared with the general population.1,2,4-6 Estimates from 2021 suggest the prevalence of chronic pain among veterans exceeds 30%; > 11% experienced high-impact chronic pain.1

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) have a prominent role in chronic pain management. Pharmacologic options for treating pain, once a mainstay of therapy, present several challenges for patients and PCPs, including drug-drug interactions and adverse effects.7 The US opioid epidemic and shift to a biopsychosocial model of chronic pain care have increased emphasis on nonpharmacologic treatment options.8,9 These include integrative modalities, which incorporate conventional approaches with an array of complementary health approaches.10-12

Integrative therapy is a prominent feature in whole person care, which may be best exemplified by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of care.13-14 Whole health empowers an individual to take charge of their health and well-being so they can “live their life to the fullest.”14 As implemented in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), whole health includes the use of evidence-based

METHODS

Using a cross-sectional survey design, PCPs and patients with chronic back pain affiliated with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System were invited to participate in separate but similar surveys to assess knowledge, interest, and use of nonpharmacologic integrative modalities for the treatment of chronic pain. In May, June, and July 2023, 78 PCPs received 3 email

Both survey instruments are available upon request, were developed by the study team, and included a mix of yes/no questions, “select all that apply” items, Likert scale response items, and open-ended questions. For one question about which modalities they would like available, the respondent was instructed to select up to 5 modalities. The instruments were extensively pretested by members of the study team, which included 2 PCPs and a nonveteran with chronic back pain.

The list of integrative modalities included in the survey was derived from the tier 1 and tier 2 complementary and integrative health modalities identified in a VHA Directive on complementary and integrative health.15,16 Tier 1 approaches are considered to have sufficient evidence and must be made available to veterans either within a VA medical facility or in the community. Tier 2 approaches are generally considered safe and may be made available but do not have sufficient evidence to mandate their provision. For participant ease, the integrative modalities were divided into 5 subgroups: manual therapies, energy/biofield therapies, mental health therapies, nutrition counseling, and movement therapies. The clinician survey assessed clinicians’ training and interest, clinical and personal use, and perceived barriers to providing integrative modalities for chronic pain. Professional and personal demographic data were also collected. Similarly, the patient survey assessed use of integrative therapies, perceptions of and interest in integrative modalities, and potential barriers to use. Demographic and health-related information was also collected.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics (eg, frequency counts, means, medians) and visual graphic displays. Separate analyses were conducted for clinicians and patients in addition to a comparative analysis of the use and potential interest in integrative modalities. Analysis were conducted using R software. This study was deemed nonresearch quality improvement by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System facility research oversight board and institutional review board approval was not solicited.

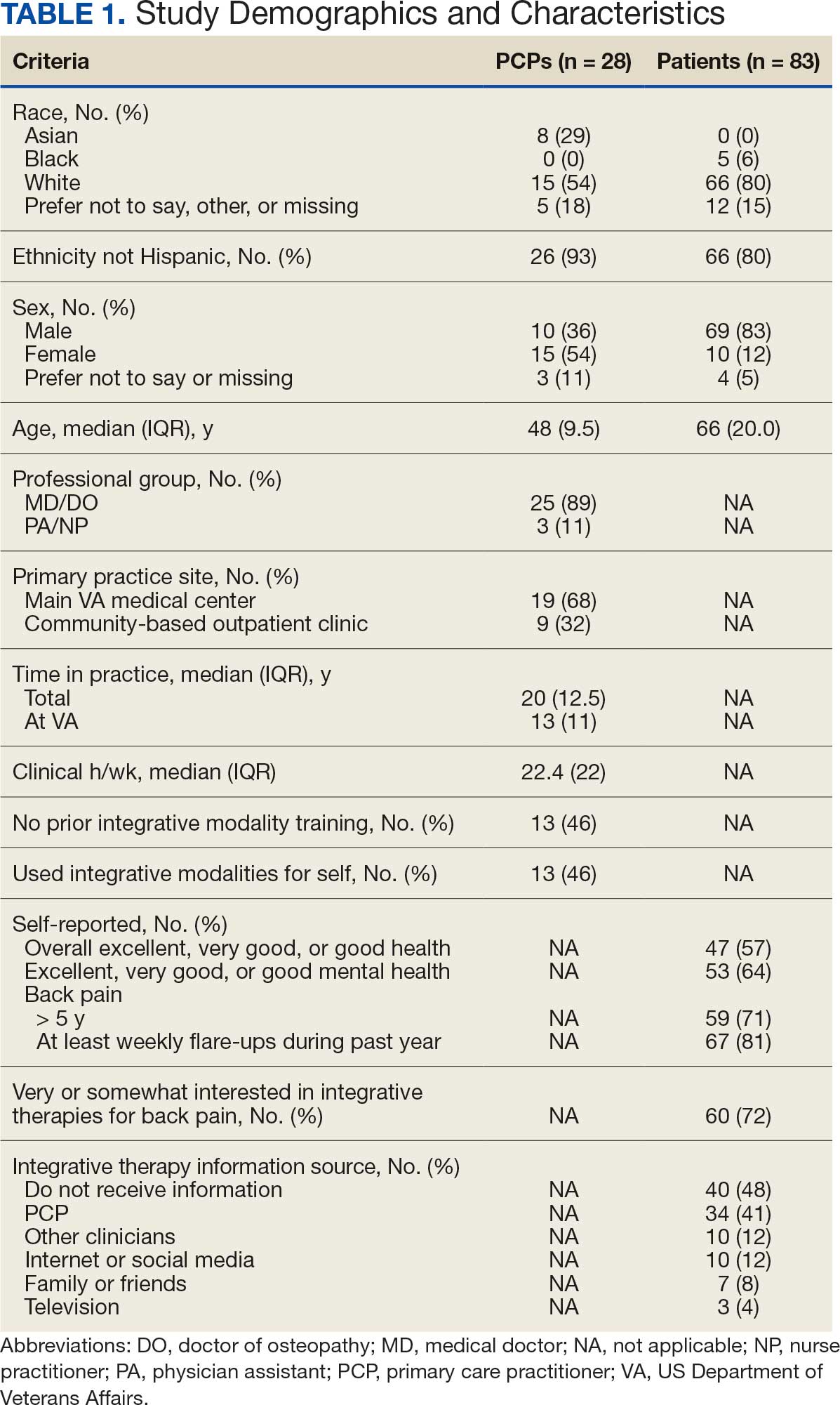

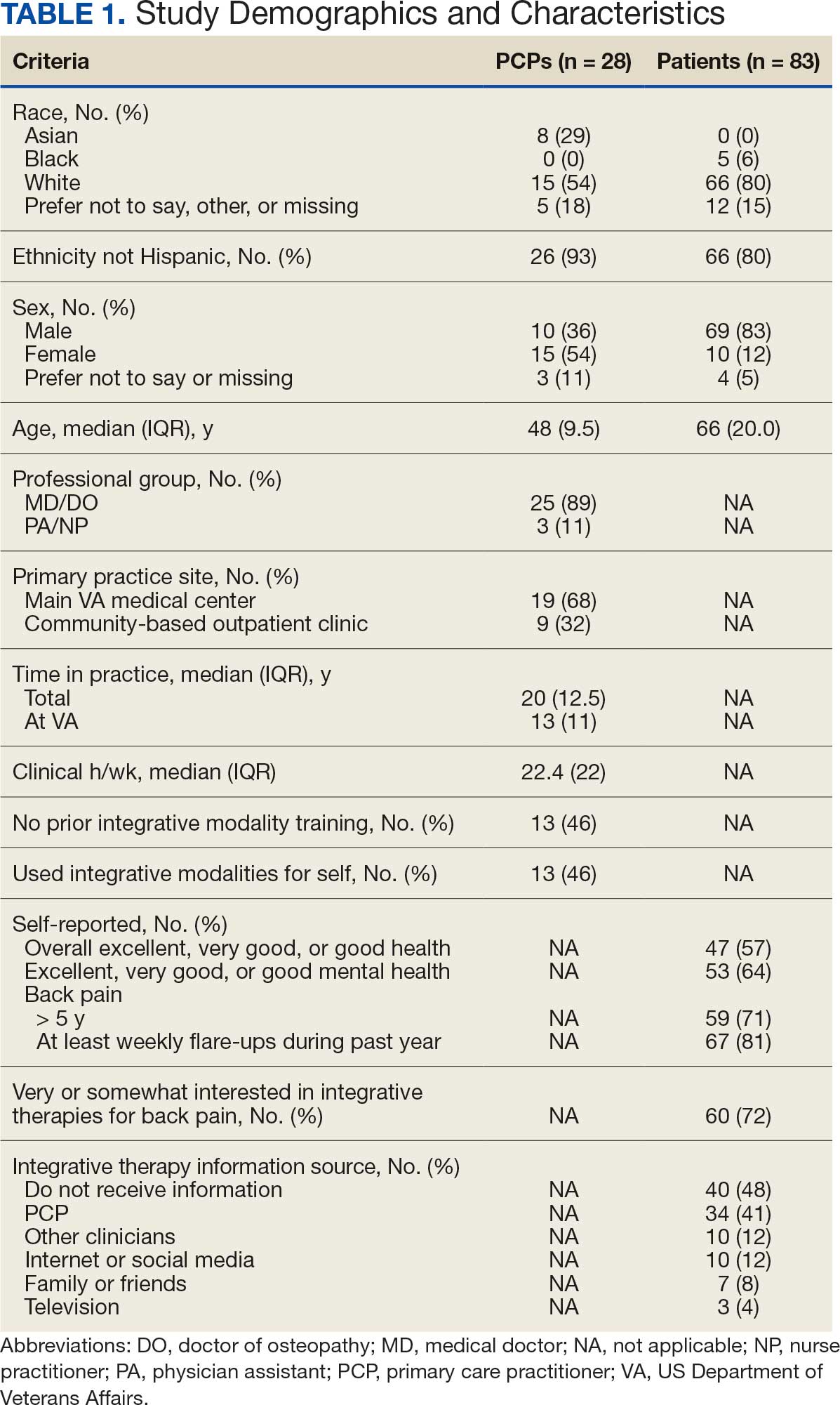

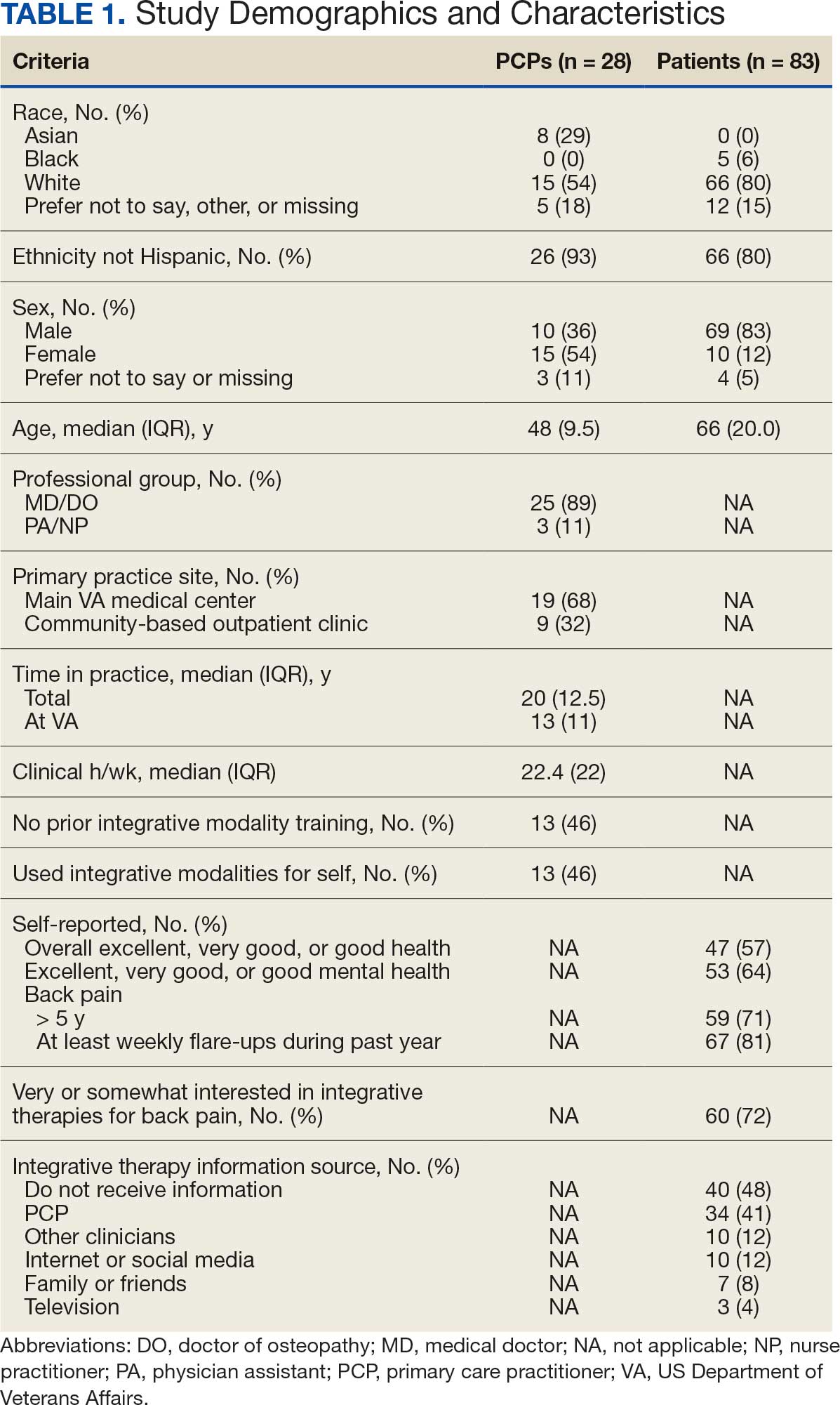

RESULTS

Twenty-eight clinicians completed the survey, yielding a participation rate of 36%. Participating clinicians had a median (IQR) age of 48 years (9.5), 15 self-identified as White (54%), 8 as Asian (29%), 15 as female (54%), 26 as non-Hispanic (93%), and 25 were medical doctors or doctors of osteopathy (89%). Nineteen (68%) worked at the main hospital outpatient clinic, and 9 practiced at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Thirteen respondents (46%) reported having no formal education or training in integrative approaches. Among those with prior training, 8 clinicians had nutrition counseling (29%) and 7 had psychologic therapy training (25%). Thirteen respondents (46%) also reported using integrative modalities for personal health needs: 8 used psychological therapies, 8 used movement therapies, 10 used integrative modalities for stress management or relaxation, and 8 used them for physical symptoms (Table 1).

Overall, 85 of 200 patients (43%) responded to the study survey. Two patients indicated they did not have chronic back pain and were excluded. Patients had a median (IQR) age of 66 (20) years, with 66 self-identifying as White (80%), 69 as male (83%), and 66 as non-Hispanic (80%). Forty-four patients (53%) received care at CBOCs. Forty-seven patients reported excellent, very good, or good overall health (57%), while 53 reported excellent, very good, or good mental health (64%). Fifty-nine patients reported back pain duration > 5 years (71%), and 67 (81%) indicated experiencing back pain flare-ups at least once per week over the previous 12 months. Sixty patients (72%) indicated they were somewhat or very interested in using integrative therapies as a back pain treatment; however, 40 patients (48%) indicated they had not received information about these therapies. Among those who indicated they had received information, the most frequently reported source was their PCP (41%). Most patients (72%) also reported feeling somewhat to very comfortable discussing integrative medicine therapies with their PCP.

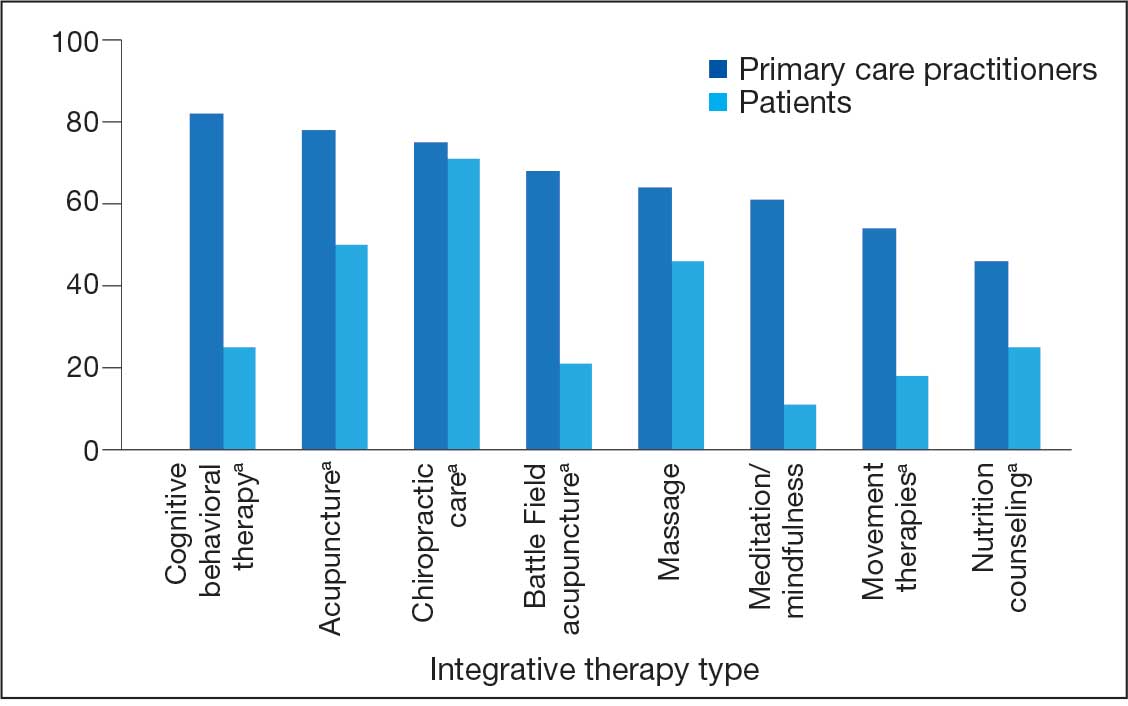

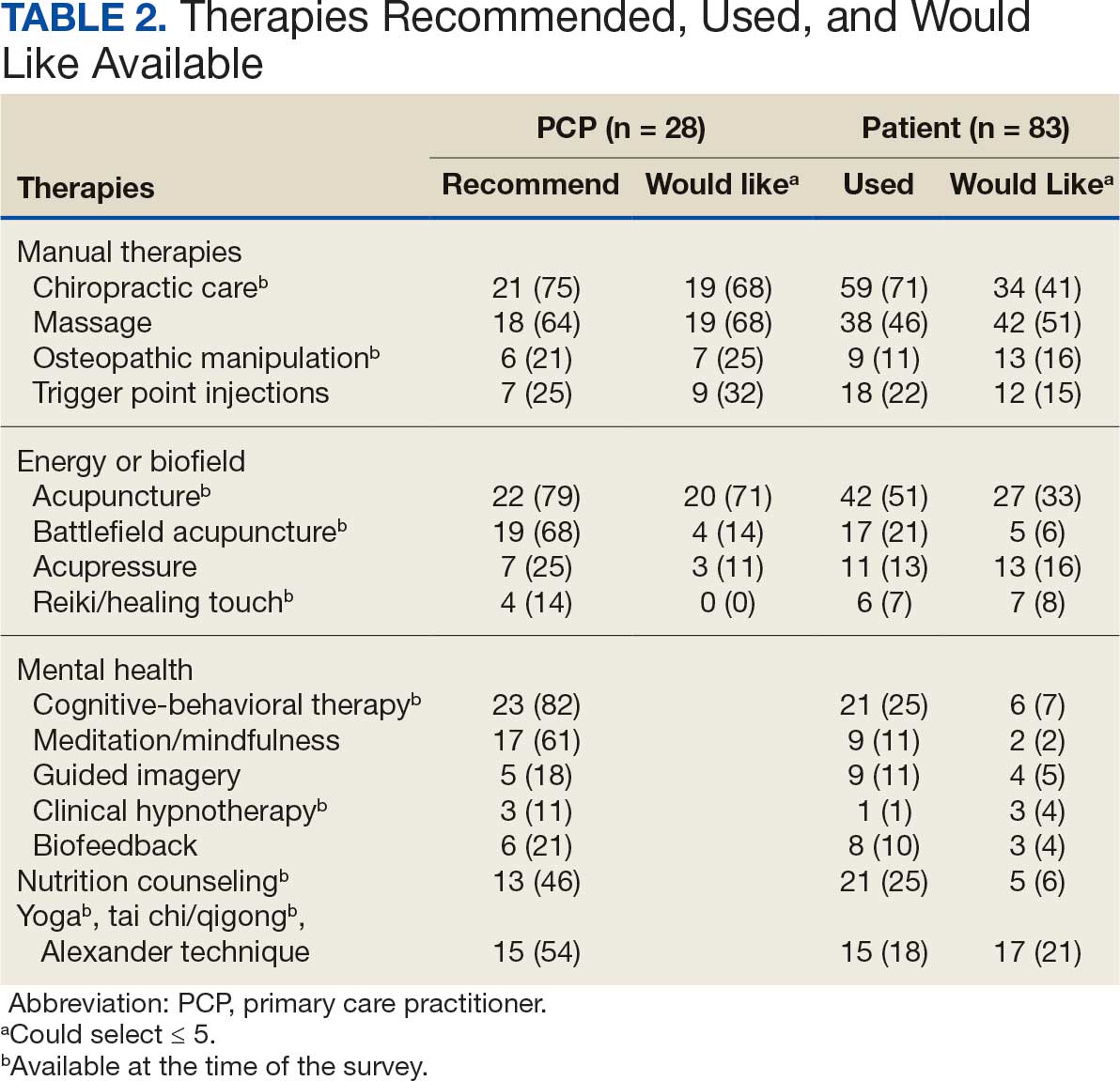

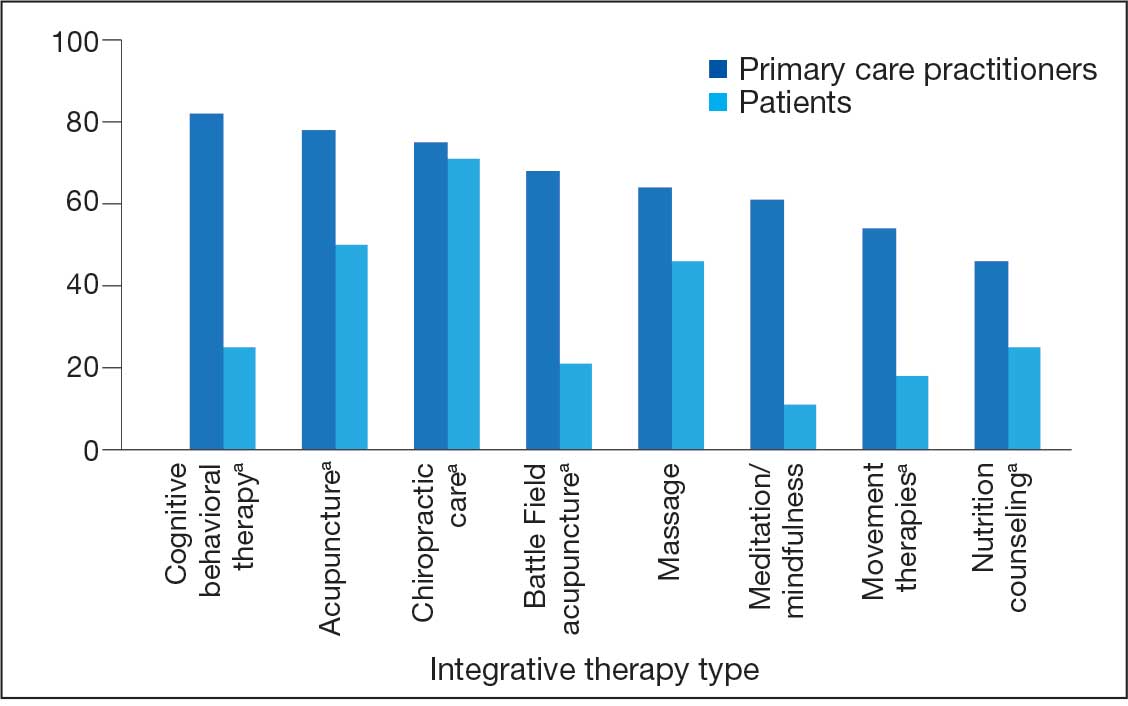

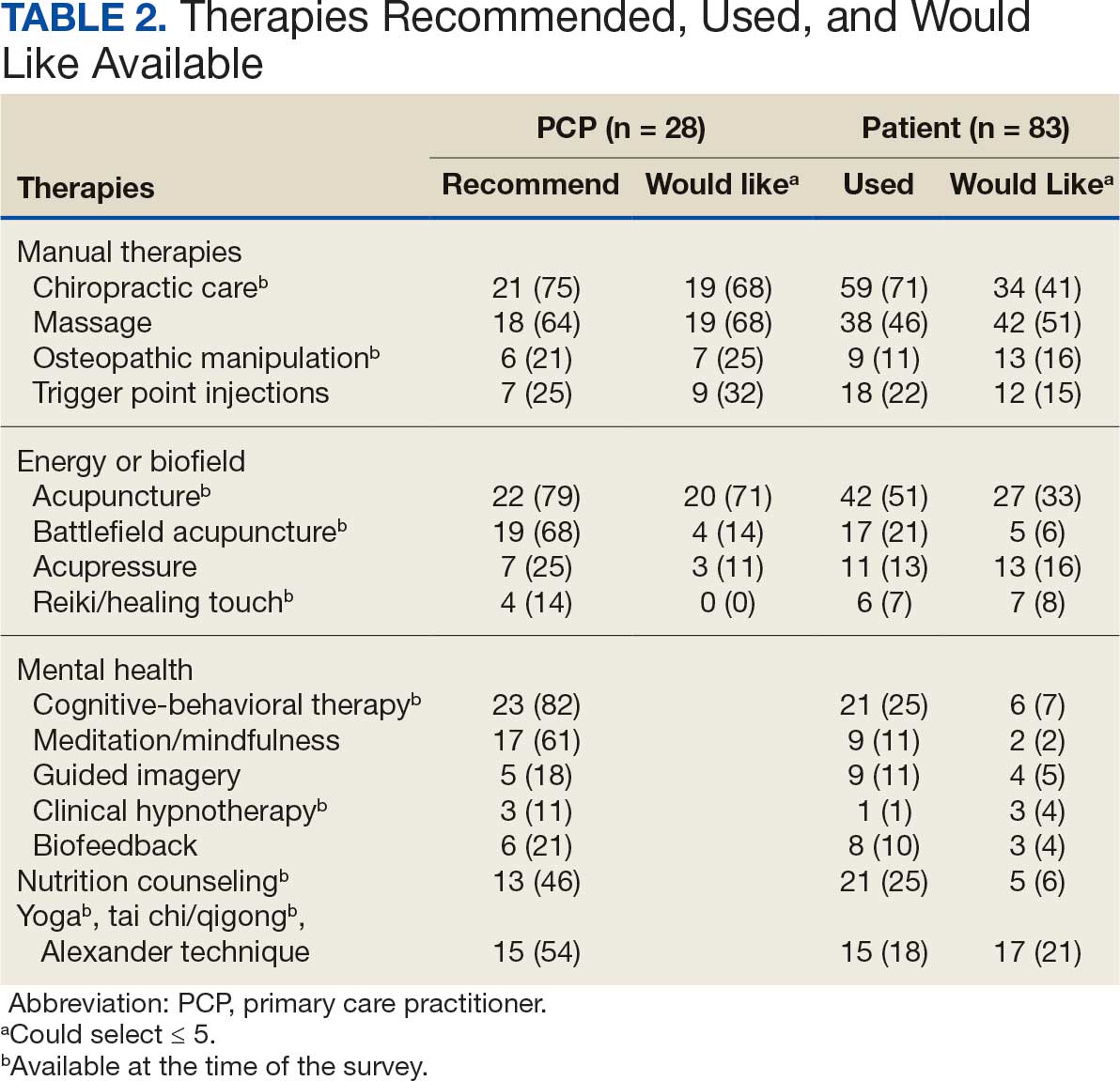

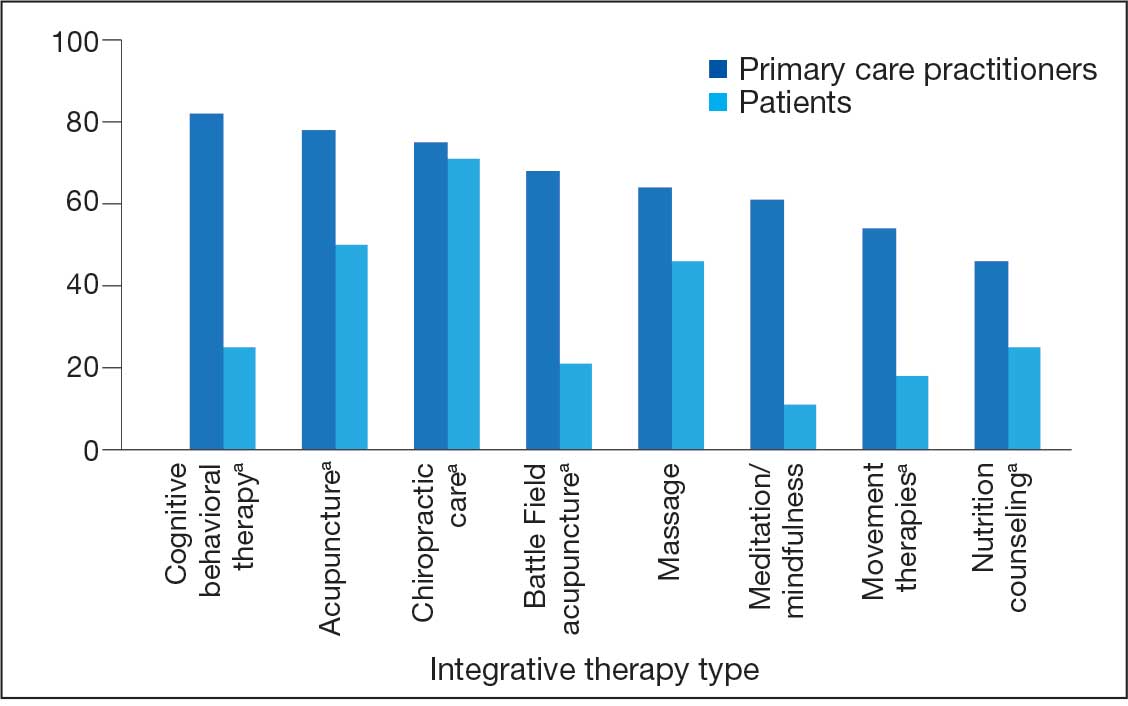

Integrative Therapy Recommendations and Use

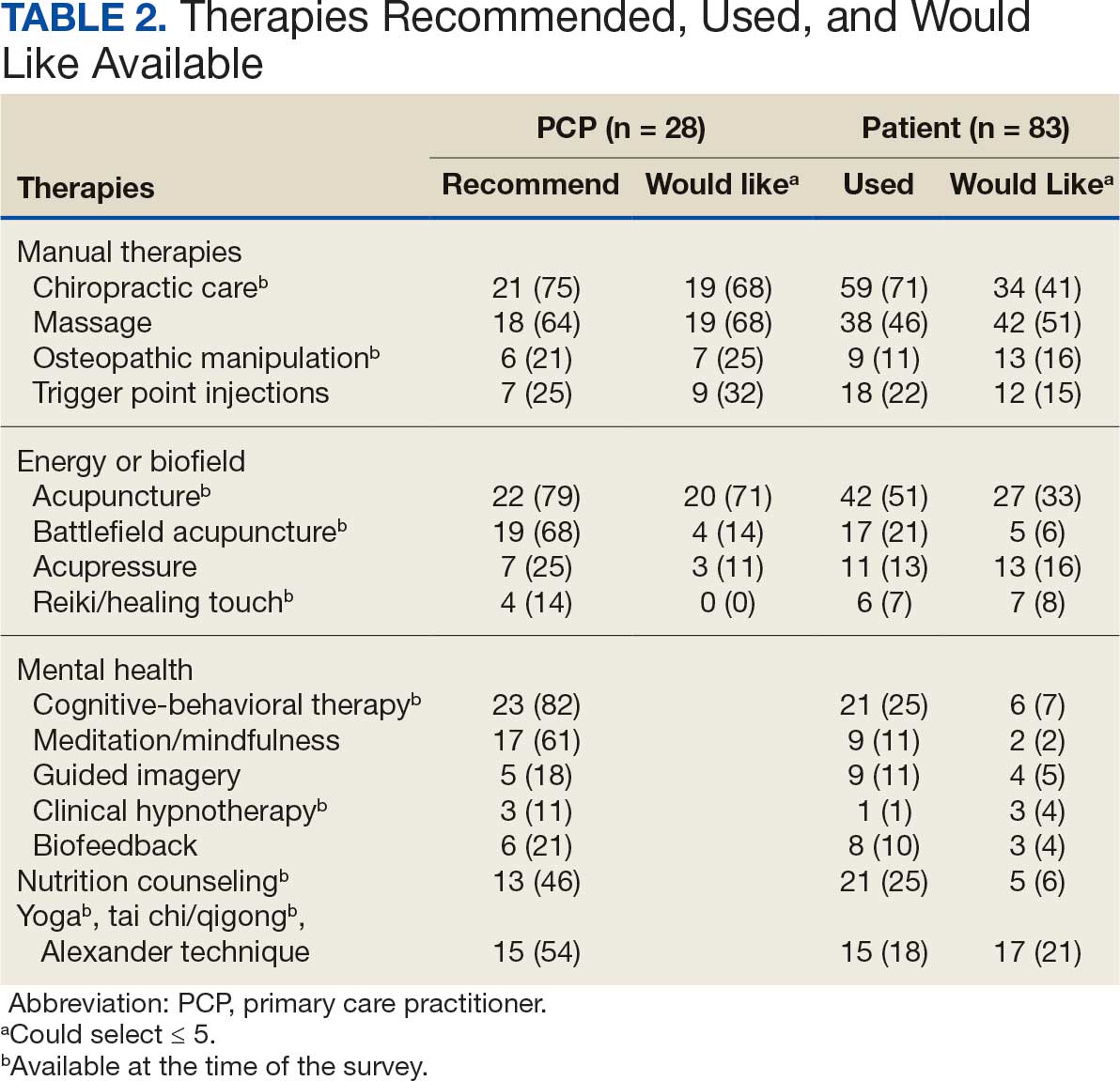

PCPs reported recommending multiple integrative modalities: 23 (82%) recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy, 22 (79%) recommended acupuncture, 21 (75%) recommended chiropractic, 19 (68%) recommended battlefield acupuncture, recommended massage 18 (64%), 17 (61%) recommended meditation or mindfulness, and 15 (54%) recommended movement therapies such as yoga or tai chi/qigong (Figure 1). The only therapies used by at least half of the patients were chiropractic used by 59 patients (71%) and acupuncture by 42 patients (51%). Thirty-eight patients (46%) reported massage use and 21 patients (25%) used cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 2).

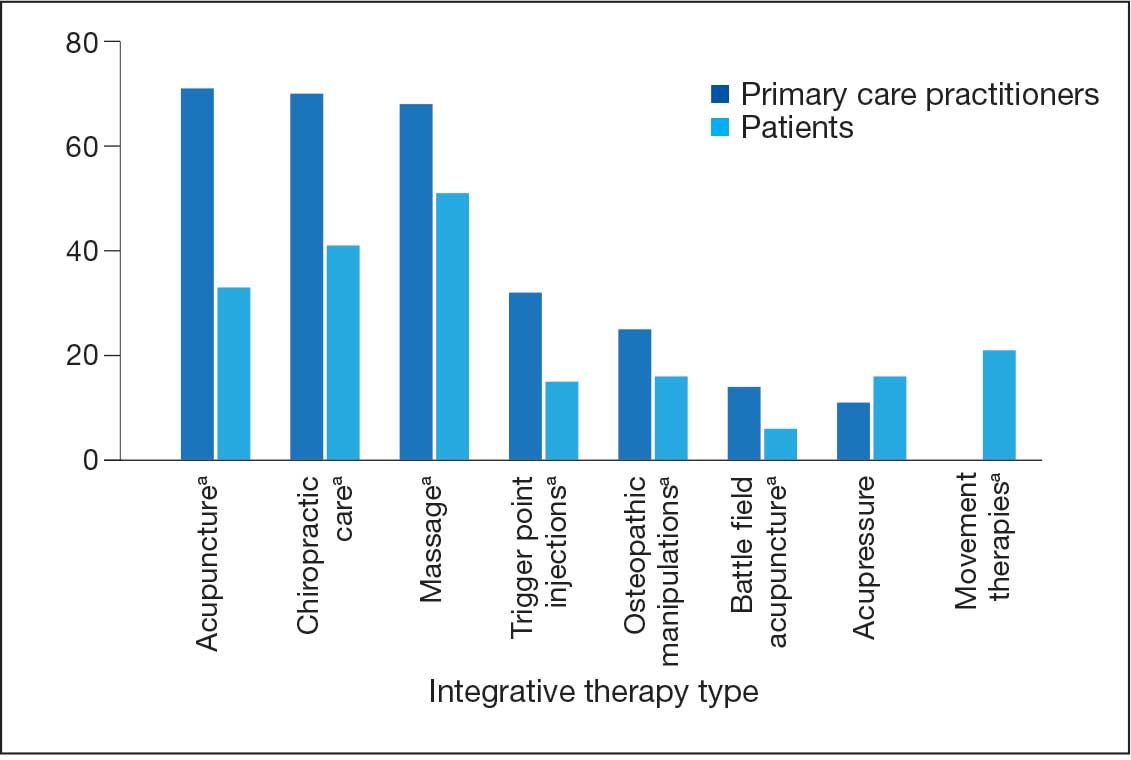

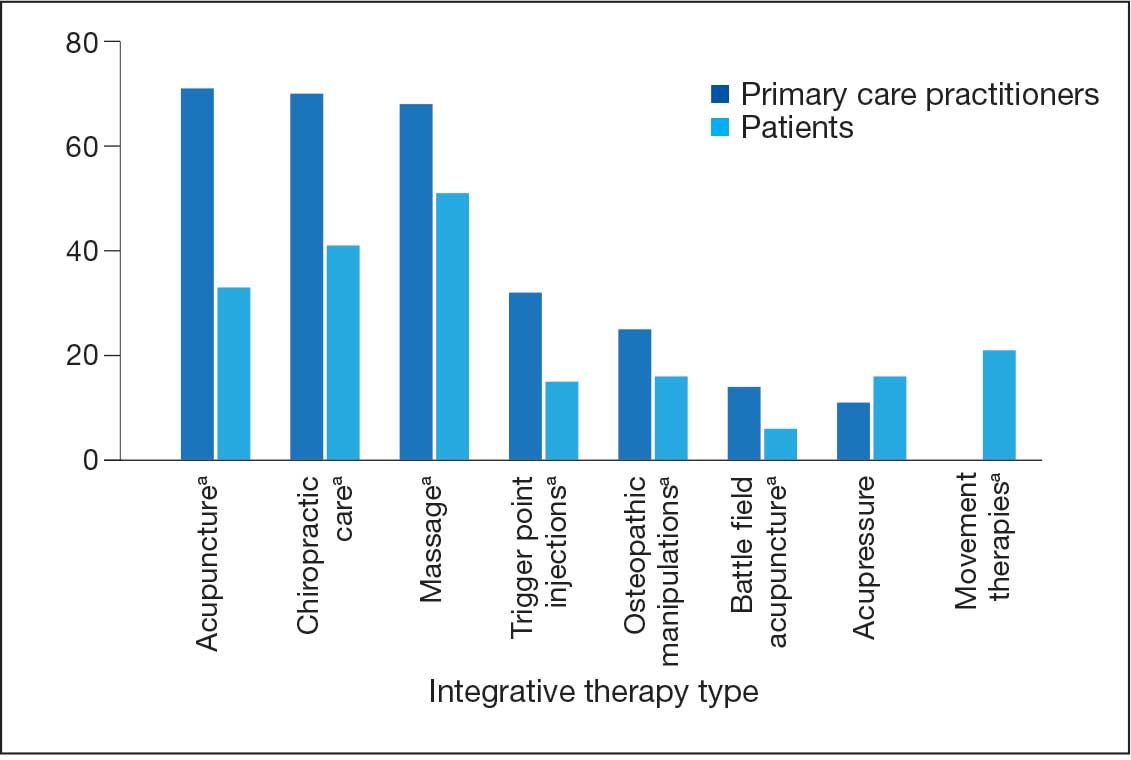

Integrative Therapies Desired

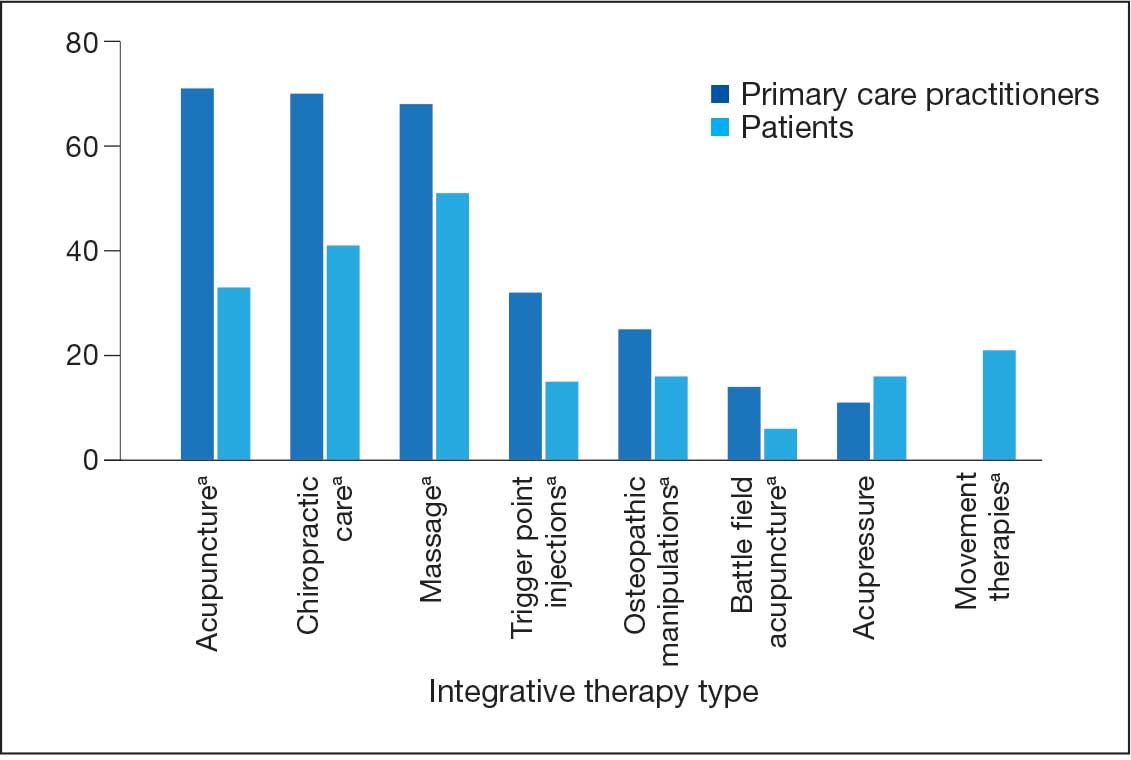

A majority of PCPs identified acupuncture (n = 20, 71%), chiropractic (n = 19, 68%), and massage (n = 19, 68%) as therapies they would most like to have available for patients with chronic pain (Figure 2). Similarly, patients identified massage (n = 42, 51%), chiropractic (n = 34, 41%), and acupuncture (n = 27, 33%) as most desired. Seventeen patients (21%) expressed interest in movement therapies.

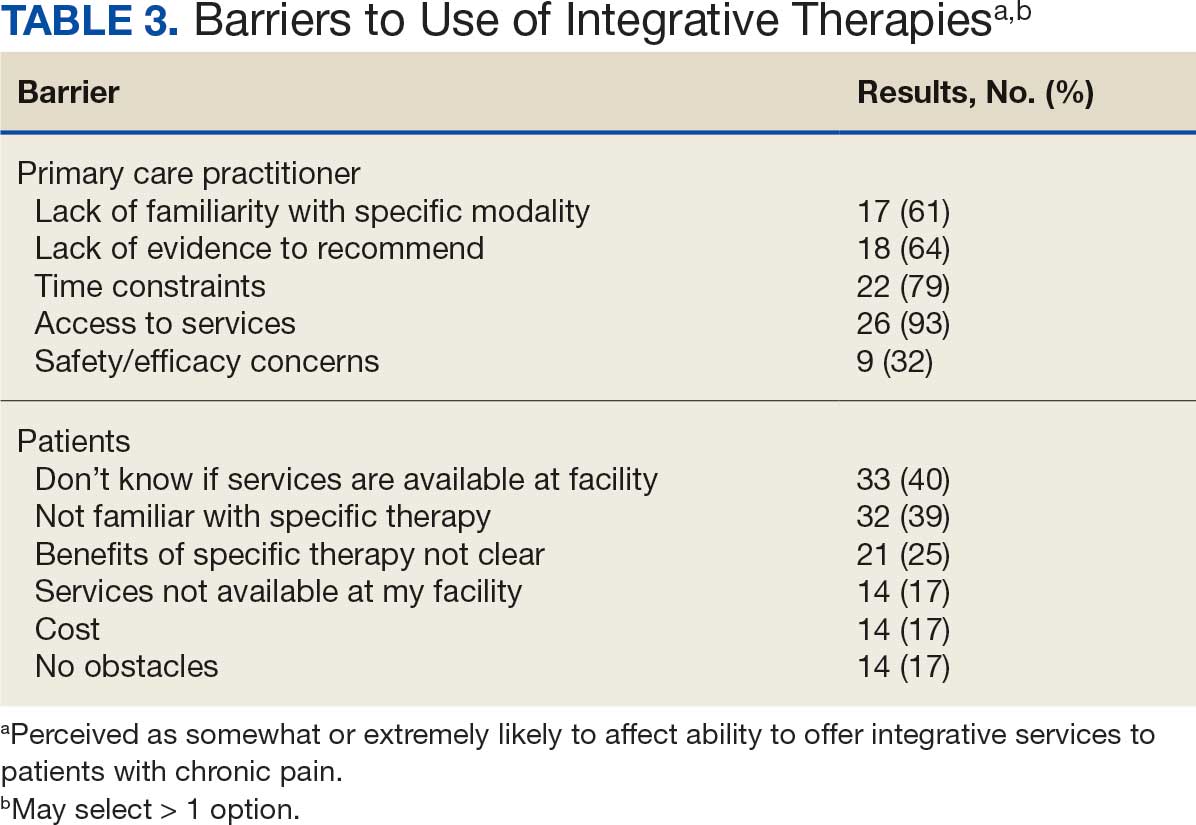

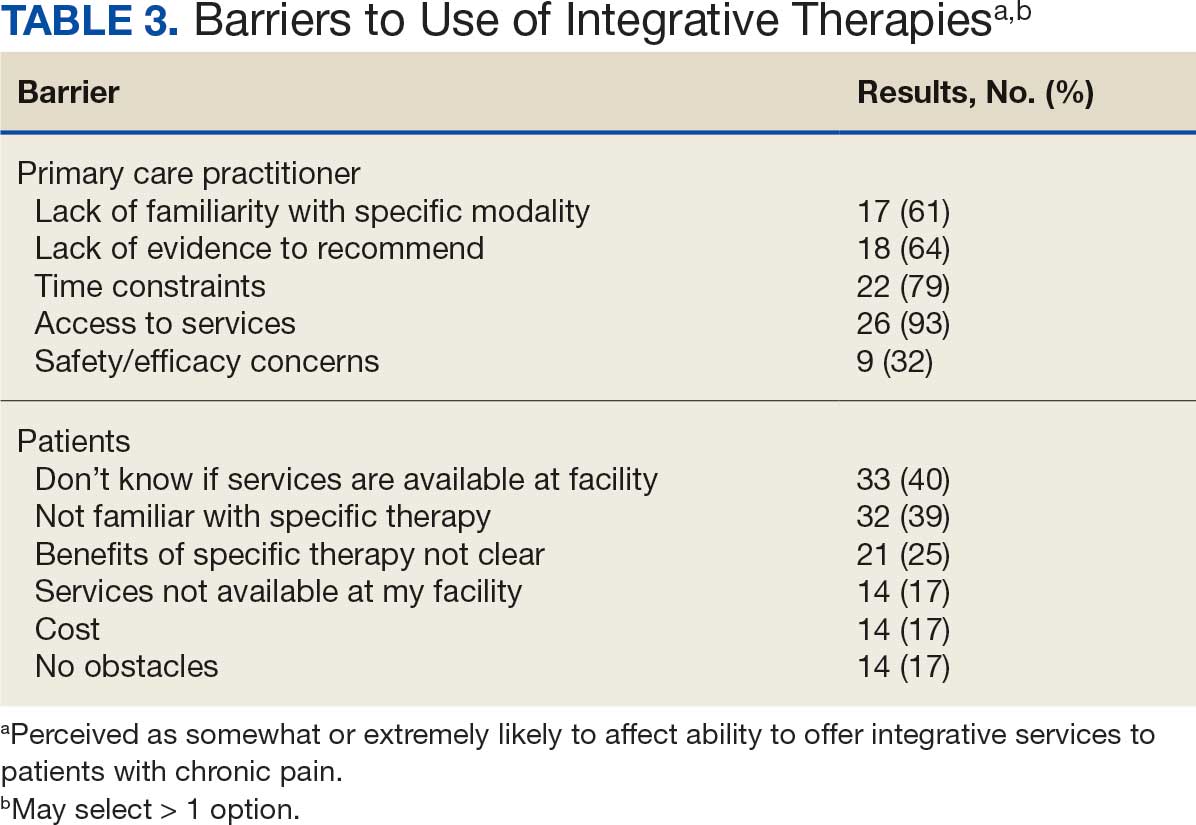

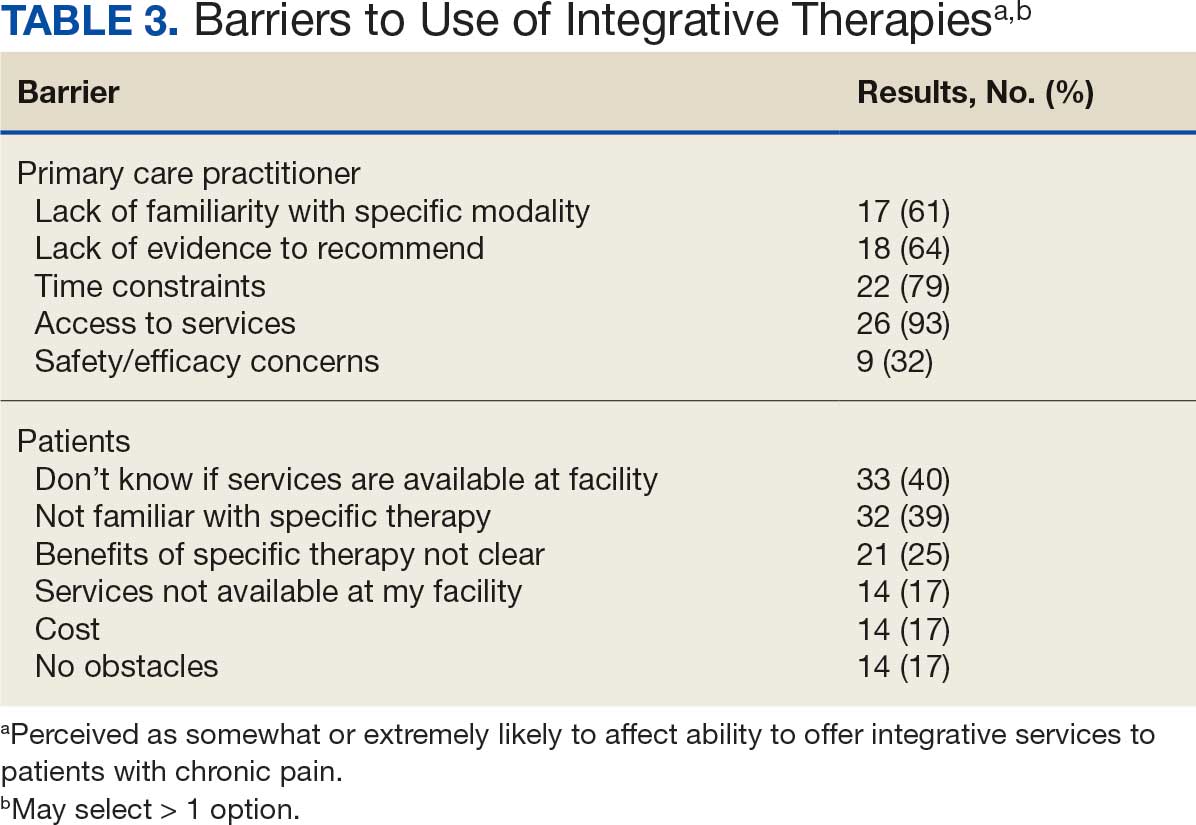

Barriers to Integrative Therapies Use

When asked about barriers to use, 26 PCPs (93%) identified access to services as a somewhat or extremely likely barrier, and 22 identified time constraints (79%) (Table 3). However, 17 PCPs (61%) noted lack of familiarity, and 18 (64%) noted a lack of scientific evidence as barriers to recommending integrative modalities. Among patients, 33 (40%) indicated not knowing what services were available at their facility as a barrier, 32 (39%) were not familiar with specific therapies, and 21 (25%) indicated a lack of clarity about the benefits of a specific therapy. Only 14 patients (17%) indicated that there were no obstacles to use.

DISCUSSION

Use of integrative therapies, including complementary treatments, is an increasingly important part of chronic pain management. This survey study suggests VA PCPs are willing to recommend integrative therapies and patients with chronic back pain both desire and use several therapies. Moreover, both groups expressed interest in greater availability of similar therapies. The results also highlight key barriers, such as knowledge gaps, that should be addressed to increase the uptake of integrative modalities for managing chronic pain.

An increasing number of US adults are using complementary health approaches, an important component of integrative therapy.12 This trend includes an increase in use for pain management, from 42.3% in 2002 to 49.2% in 2022; chiropractic care, acupuncture, and massage were most frequently used.12 Similarly, chiropractic, acupuncture and massage were most often used by this sample of veterans with chronic back pain and were identified by the highest percentages of PCPs and patients as the therapies they would most like available.

There were areas where the opinions of patients and clinicians differed. As has been seen previously reported, clinicians largely recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy while patients showed less interest.17 Additionally, while patients expressed interest in the availability of movement therapies, such as yoga, PCPs expressed more interest in other strategies, such as trigger point injections. These differences may reflect true preference or a tendency for clinicians and patients to select therapies with which they are more familiar. Additional research is needed to better understand the acceptability and potential use of integrative health treatments across a broad array of therapeutic options.

Despite VHA policy requiring facilities to provide certain complementary and integrative health modalities, almost all PCPs identified access to services as a major obstacle.15 Based on evidence and a rigorous vetting process, services currently required on-site, via telehealth, or through community partners include acupuncture and battlefield acupuncture (battlefield auricular acupuncture), biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, guided imagery, medical massage therapy, medication, tai chi/qigong, and yoga. Optional approaches, which may be made available to veterans, include chiropractic and healing touch. Outside the VHA, some states have introduced or enacted legislation mandating insurance coverage of nonpharmacological pain treatments.18 However, these requirements and mandates do not help address challenges such as the availability of trained/qualified practitioners.19,20 Ensuring access to complementary and integrative health treatments requires a more concerted effort to ensure that supply meets demand. It is also important to acknowledge the budgetary and physical space constraints that further limit access to services. Although expansion and integration of integrative medicine services remain a priority within the VA Whole Health program, implementation is contingent on available financial and infrastructure resources.

Time was also identified by PCPs as a barrier to recommending integrative therapies to patients. Developing and implementing time-efficient communication strategies for patient education such as concise talking points and informational handouts could help address this barrier. Furthermore, leveraging existing programs and engaging the entire health care team in patient education and referral could help increase integrative and complementary therapy uptake and use.

Although access and time were identified as major barriers, these findings also suggest that PCP and patient knowledge are another target area for enhancing the use of complementary and integrative therapies. Like prior research, most clinicians identified a lack of familiarity with certain services and a lack of scientific evidence as extremely or somewhat likely to affect their ability to offer integrative services to patients with chronic pain.21 Likewise, about 40% of patients identified being unfamiliar with a specific therapy as one of the major obstacles to receiving integrative therapies, with a similar number identifying PCPs as a source of information. The lack of familiarity may be due in part to the evolving nomenclature, with terms such as alternative, complementary, and integrative used to describe approaches outside what is often considered conventional medicine.10 On the other hand, there has also been considerable expansion in the number of therapies within this domain, along with an expanding evidence base. This suggests a need for targeted educational strategies for clinicians and patients, which can be rapidly deployed and continuously adapted as new therapies and evidence emerge.

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations with a survey-based approach, including sampling, non-response, and social desirability biases. In addition, this study only included PCPs and patients affiliated with a single VA medical center. Steps to mitigate these limitations included maintaining survey anonymity and reporting information about respondent characteristics to enhance transparency about the representativeness of the study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanding the use of nonpharmacological pain treatments, including integrative modalities, is essential for safe and effective chronic pain management and reducing opioid use. Our findings show that VA PCPs and patients with chronic back pain are interested in and have some experience with certain integrative therapies. However, even within the context of a health care system that supports the use of integrative therapies for chronic pain as part of whole person care, increasing uptake will require addressing access and time-related constraints as well as ongoing clinician and patient education.

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, et al. Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2018-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022;163:E328-E332. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291

- Nahin RL, Feinberg T, Kapos FP, Terman GW. Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2313563. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13563

- Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024;403:2133-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 5.

- Qureshi AR, Patel M, Neumark S, et al. Prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain among military veterans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Mil Health. 2025;171:310-314. doi:10.1136/military-2023-002554

- Feldman DE, Nahin RL. Disability among persons with chronic severe back pain: results from a nationally representative population-based sample. J Pain. 2022;23:2144-2154. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.016

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, Kleijnen J, Smeets RJEM. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Practice. 2019;19:224-241. doi:10.1111/papr.12735

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505. doi:10.7326/M16-2459

- Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Updated April 2021. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name.

- Taylor SL, Elwy AR. Complementary and alternative medicine for US veterans and active duty military personnel promising steps to improve their health. Med Care. 2014;52:S1-S4. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000270.

- Nahin RL, Rhee A, Stussman B. Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by US adults. JAMA. 2024;331:613-615. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26775

- Gantt CJ, Donovan N, Khung M. Veterans Affairs’ Whole Health System of Care for transitioning service members and veterans. Mil Med. 2023;188:28-32. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad047

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the Whole Health System of Care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57:53-65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938

- Department of Veterans Affairs VHA. VHA Policy Directive 1137: Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health. December 2022. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10072

- Giannitrapani KF, Holliday JR, Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Taylor SL. Synthesizing the strength of the evidence of complementary and integrative health therapies for pain. Pain Med. 2019;20:1831-1840. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz068

- Belitskaya-Levy I, David Clark J, Shih MC, Bair MJ. Treatment preferences for chronic low back pain: views of veterans and their providers. J Pain Res. 2021;14:161-171. doi:10.2147/JPR.S290400

- Onstott TN, Hurst S, Kronick R, Tsou AC, Groessl E, McMenamin SB. Health insurance mandates for nonpharmacological pain treatments in 7 US states. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:E245737. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5737

- Sullivan M, Leach M, Snow J, Moonaz S. The North American yoga therapy workforce survey. Complement Ther Med. 2017;31:39-48. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.01.006

- Bolton R, Ritter G, Highland K, Larson MJ. The relationship between capacity and utilization of nonpharmacologic therapies in the US Military Health System. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-07700-4

- Stussman BJ, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Scott R, Feinberg T, Ward BW. Reasons office-based physicians in the United States recommend common complementary health approaches to patients: an exploratory study using a national survey. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28:651-663. doi:10.1089/jicm.2022.0493

More than 50 million US adults report experiencing chronic pain, with nearly 7% experiencing high-impact chronic pain.1-3 Chronic pain negatively affects daily function, results in lost productivity, is a leading cause of disability, and is more prevalent among veterans compared with the general population.1,2,4-6 Estimates from 2021 suggest the prevalence of chronic pain among veterans exceeds 30%; > 11% experienced high-impact chronic pain.1

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) have a prominent role in chronic pain management. Pharmacologic options for treating pain, once a mainstay of therapy, present several challenges for patients and PCPs, including drug-drug interactions and adverse effects.7 The US opioid epidemic and shift to a biopsychosocial model of chronic pain care have increased emphasis on nonpharmacologic treatment options.8,9 These include integrative modalities, which incorporate conventional approaches with an array of complementary health approaches.10-12

Integrative therapy is a prominent feature in whole person care, which may be best exemplified by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of care.13-14 Whole health empowers an individual to take charge of their health and well-being so they can “live their life to the fullest.”14 As implemented in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), whole health includes the use of evidence-based

METHODS

Using a cross-sectional survey design, PCPs and patients with chronic back pain affiliated with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System were invited to participate in separate but similar surveys to assess knowledge, interest, and use of nonpharmacologic integrative modalities for the treatment of chronic pain. In May, June, and July 2023, 78 PCPs received 3 email

Both survey instruments are available upon request, were developed by the study team, and included a mix of yes/no questions, “select all that apply” items, Likert scale response items, and open-ended questions. For one question about which modalities they would like available, the respondent was instructed to select up to 5 modalities. The instruments were extensively pretested by members of the study team, which included 2 PCPs and a nonveteran with chronic back pain.

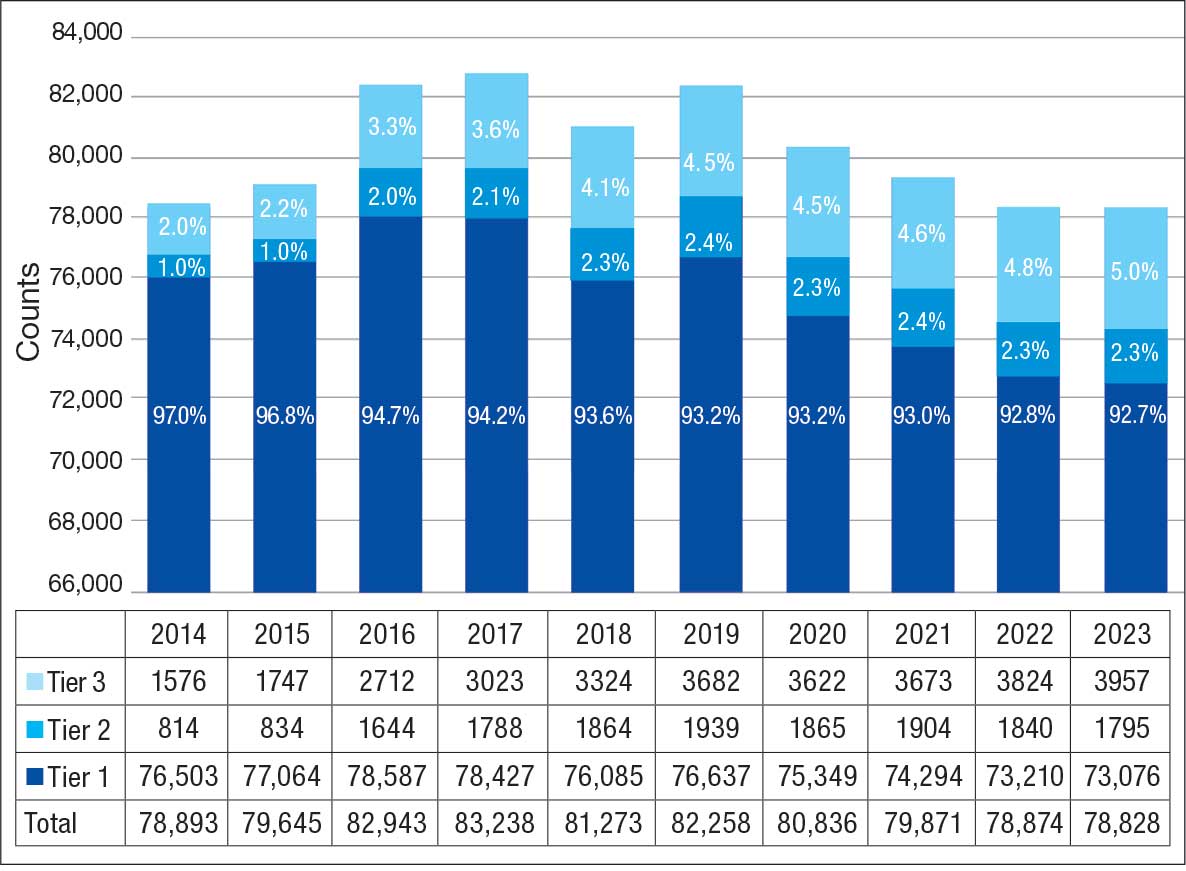

The list of integrative modalities included in the survey was derived from the tier 1 and tier 2 complementary and integrative health modalities identified in a VHA Directive on complementary and integrative health.15,16 Tier 1 approaches are considered to have sufficient evidence and must be made available to veterans either within a VA medical facility or in the community. Tier 2 approaches are generally considered safe and may be made available but do not have sufficient evidence to mandate their provision. For participant ease, the integrative modalities were divided into 5 subgroups: manual therapies, energy/biofield therapies, mental health therapies, nutrition counseling, and movement therapies. The clinician survey assessed clinicians’ training and interest, clinical and personal use, and perceived barriers to providing integrative modalities for chronic pain. Professional and personal demographic data were also collected. Similarly, the patient survey assessed use of integrative therapies, perceptions of and interest in integrative modalities, and potential barriers to use. Demographic and health-related information was also collected.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics (eg, frequency counts, means, medians) and visual graphic displays. Separate analyses were conducted for clinicians and patients in addition to a comparative analysis of the use and potential interest in integrative modalities. Analysis were conducted using R software. This study was deemed nonresearch quality improvement by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System facility research oversight board and institutional review board approval was not solicited.

RESULTS

Twenty-eight clinicians completed the survey, yielding a participation rate of 36%. Participating clinicians had a median (IQR) age of 48 years (9.5), 15 self-identified as White (54%), 8 as Asian (29%), 15 as female (54%), 26 as non-Hispanic (93%), and 25 were medical doctors or doctors of osteopathy (89%). Nineteen (68%) worked at the main hospital outpatient clinic, and 9 practiced at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Thirteen respondents (46%) reported having no formal education or training in integrative approaches. Among those with prior training, 8 clinicians had nutrition counseling (29%) and 7 had psychologic therapy training (25%). Thirteen respondents (46%) also reported using integrative modalities for personal health needs: 8 used psychological therapies, 8 used movement therapies, 10 used integrative modalities for stress management or relaxation, and 8 used them for physical symptoms (Table 1).

Overall, 85 of 200 patients (43%) responded to the study survey. Two patients indicated they did not have chronic back pain and were excluded. Patients had a median (IQR) age of 66 (20) years, with 66 self-identifying as White (80%), 69 as male (83%), and 66 as non-Hispanic (80%). Forty-four patients (53%) received care at CBOCs. Forty-seven patients reported excellent, very good, or good overall health (57%), while 53 reported excellent, very good, or good mental health (64%). Fifty-nine patients reported back pain duration > 5 years (71%), and 67 (81%) indicated experiencing back pain flare-ups at least once per week over the previous 12 months. Sixty patients (72%) indicated they were somewhat or very interested in using integrative therapies as a back pain treatment; however, 40 patients (48%) indicated they had not received information about these therapies. Among those who indicated they had received information, the most frequently reported source was their PCP (41%). Most patients (72%) also reported feeling somewhat to very comfortable discussing integrative medicine therapies with their PCP.

Integrative Therapy Recommendations and Use

PCPs reported recommending multiple integrative modalities: 23 (82%) recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy, 22 (79%) recommended acupuncture, 21 (75%) recommended chiropractic, 19 (68%) recommended battlefield acupuncture, recommended massage 18 (64%), 17 (61%) recommended meditation or mindfulness, and 15 (54%) recommended movement therapies such as yoga or tai chi/qigong (Figure 1). The only therapies used by at least half of the patients were chiropractic used by 59 patients (71%) and acupuncture by 42 patients (51%). Thirty-eight patients (46%) reported massage use and 21 patients (25%) used cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 2).

Integrative Therapies Desired

A majority of PCPs identified acupuncture (n = 20, 71%), chiropractic (n = 19, 68%), and massage (n = 19, 68%) as therapies they would most like to have available for patients with chronic pain (Figure 2). Similarly, patients identified massage (n = 42, 51%), chiropractic (n = 34, 41%), and acupuncture (n = 27, 33%) as most desired. Seventeen patients (21%) expressed interest in movement therapies.

Barriers to Integrative Therapies Use

When asked about barriers to use, 26 PCPs (93%) identified access to services as a somewhat or extremely likely barrier, and 22 identified time constraints (79%) (Table 3). However, 17 PCPs (61%) noted lack of familiarity, and 18 (64%) noted a lack of scientific evidence as barriers to recommending integrative modalities. Among patients, 33 (40%) indicated not knowing what services were available at their facility as a barrier, 32 (39%) were not familiar with specific therapies, and 21 (25%) indicated a lack of clarity about the benefits of a specific therapy. Only 14 patients (17%) indicated that there were no obstacles to use.

DISCUSSION

Use of integrative therapies, including complementary treatments, is an increasingly important part of chronic pain management. This survey study suggests VA PCPs are willing to recommend integrative therapies and patients with chronic back pain both desire and use several therapies. Moreover, both groups expressed interest in greater availability of similar therapies. The results also highlight key barriers, such as knowledge gaps, that should be addressed to increase the uptake of integrative modalities for managing chronic pain.

An increasing number of US adults are using complementary health approaches, an important component of integrative therapy.12 This trend includes an increase in use for pain management, from 42.3% in 2002 to 49.2% in 2022; chiropractic care, acupuncture, and massage were most frequently used.12 Similarly, chiropractic, acupuncture and massage were most often used by this sample of veterans with chronic back pain and were identified by the highest percentages of PCPs and patients as the therapies they would most like available.

There were areas where the opinions of patients and clinicians differed. As has been seen previously reported, clinicians largely recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy while patients showed less interest.17 Additionally, while patients expressed interest in the availability of movement therapies, such as yoga, PCPs expressed more interest in other strategies, such as trigger point injections. These differences may reflect true preference or a tendency for clinicians and patients to select therapies with which they are more familiar. Additional research is needed to better understand the acceptability and potential use of integrative health treatments across a broad array of therapeutic options.

Despite VHA policy requiring facilities to provide certain complementary and integrative health modalities, almost all PCPs identified access to services as a major obstacle.15 Based on evidence and a rigorous vetting process, services currently required on-site, via telehealth, or through community partners include acupuncture and battlefield acupuncture (battlefield auricular acupuncture), biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, guided imagery, medical massage therapy, medication, tai chi/qigong, and yoga. Optional approaches, which may be made available to veterans, include chiropractic and healing touch. Outside the VHA, some states have introduced or enacted legislation mandating insurance coverage of nonpharmacological pain treatments.18 However, these requirements and mandates do not help address challenges such as the availability of trained/qualified practitioners.19,20 Ensuring access to complementary and integrative health treatments requires a more concerted effort to ensure that supply meets demand. It is also important to acknowledge the budgetary and physical space constraints that further limit access to services. Although expansion and integration of integrative medicine services remain a priority within the VA Whole Health program, implementation is contingent on available financial and infrastructure resources.

Time was also identified by PCPs as a barrier to recommending integrative therapies to patients. Developing and implementing time-efficient communication strategies for patient education such as concise talking points and informational handouts could help address this barrier. Furthermore, leveraging existing programs and engaging the entire health care team in patient education and referral could help increase integrative and complementary therapy uptake and use.

Although access and time were identified as major barriers, these findings also suggest that PCP and patient knowledge are another target area for enhancing the use of complementary and integrative therapies. Like prior research, most clinicians identified a lack of familiarity with certain services and a lack of scientific evidence as extremely or somewhat likely to affect their ability to offer integrative services to patients with chronic pain.21 Likewise, about 40% of patients identified being unfamiliar with a specific therapy as one of the major obstacles to receiving integrative therapies, with a similar number identifying PCPs as a source of information. The lack of familiarity may be due in part to the evolving nomenclature, with terms such as alternative, complementary, and integrative used to describe approaches outside what is often considered conventional medicine.10 On the other hand, there has also been considerable expansion in the number of therapies within this domain, along with an expanding evidence base. This suggests a need for targeted educational strategies for clinicians and patients, which can be rapidly deployed and continuously adapted as new therapies and evidence emerge.

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations with a survey-based approach, including sampling, non-response, and social desirability biases. In addition, this study only included PCPs and patients affiliated with a single VA medical center. Steps to mitigate these limitations included maintaining survey anonymity and reporting information about respondent characteristics to enhance transparency about the representativeness of the study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanding the use of nonpharmacological pain treatments, including integrative modalities, is essential for safe and effective chronic pain management and reducing opioid use. Our findings show that VA PCPs and patients with chronic back pain are interested in and have some experience with certain integrative therapies. However, even within the context of a health care system that supports the use of integrative therapies for chronic pain as part of whole person care, increasing uptake will require addressing access and time-related constraints as well as ongoing clinician and patient education.

More than 50 million US adults report experiencing chronic pain, with nearly 7% experiencing high-impact chronic pain.1-3 Chronic pain negatively affects daily function, results in lost productivity, is a leading cause of disability, and is more prevalent among veterans compared with the general population.1,2,4-6 Estimates from 2021 suggest the prevalence of chronic pain among veterans exceeds 30%; > 11% experienced high-impact chronic pain.1

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) have a prominent role in chronic pain management. Pharmacologic options for treating pain, once a mainstay of therapy, present several challenges for patients and PCPs, including drug-drug interactions and adverse effects.7 The US opioid epidemic and shift to a biopsychosocial model of chronic pain care have increased emphasis on nonpharmacologic treatment options.8,9 These include integrative modalities, which incorporate conventional approaches with an array of complementary health approaches.10-12

Integrative therapy is a prominent feature in whole person care, which may be best exemplified by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of care.13-14 Whole health empowers an individual to take charge of their health and well-being so they can “live their life to the fullest.”14 As implemented in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), whole health includes the use of evidence-based

METHODS

Using a cross-sectional survey design, PCPs and patients with chronic back pain affiliated with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System were invited to participate in separate but similar surveys to assess knowledge, interest, and use of nonpharmacologic integrative modalities for the treatment of chronic pain. In May, June, and July 2023, 78 PCPs received 3 email

Both survey instruments are available upon request, were developed by the study team, and included a mix of yes/no questions, “select all that apply” items, Likert scale response items, and open-ended questions. For one question about which modalities they would like available, the respondent was instructed to select up to 5 modalities. The instruments were extensively pretested by members of the study team, which included 2 PCPs and a nonveteran with chronic back pain.

The list of integrative modalities included in the survey was derived from the tier 1 and tier 2 complementary and integrative health modalities identified in a VHA Directive on complementary and integrative health.15,16 Tier 1 approaches are considered to have sufficient evidence and must be made available to veterans either within a VA medical facility or in the community. Tier 2 approaches are generally considered safe and may be made available but do not have sufficient evidence to mandate their provision. For participant ease, the integrative modalities were divided into 5 subgroups: manual therapies, energy/biofield therapies, mental health therapies, nutrition counseling, and movement therapies. The clinician survey assessed clinicians’ training and interest, clinical and personal use, and perceived barriers to providing integrative modalities for chronic pain. Professional and personal demographic data were also collected. Similarly, the patient survey assessed use of integrative therapies, perceptions of and interest in integrative modalities, and potential barriers to use. Demographic and health-related information was also collected.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics (eg, frequency counts, means, medians) and visual graphic displays. Separate analyses were conducted for clinicians and patients in addition to a comparative analysis of the use and potential interest in integrative modalities. Analysis were conducted using R software. This study was deemed nonresearch quality improvement by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System facility research oversight board and institutional review board approval was not solicited.

RESULTS

Twenty-eight clinicians completed the survey, yielding a participation rate of 36%. Participating clinicians had a median (IQR) age of 48 years (9.5), 15 self-identified as White (54%), 8 as Asian (29%), 15 as female (54%), 26 as non-Hispanic (93%), and 25 were medical doctors or doctors of osteopathy (89%). Nineteen (68%) worked at the main hospital outpatient clinic, and 9 practiced at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Thirteen respondents (46%) reported having no formal education or training in integrative approaches. Among those with prior training, 8 clinicians had nutrition counseling (29%) and 7 had psychologic therapy training (25%). Thirteen respondents (46%) also reported using integrative modalities for personal health needs: 8 used psychological therapies, 8 used movement therapies, 10 used integrative modalities for stress management or relaxation, and 8 used them for physical symptoms (Table 1).

Overall, 85 of 200 patients (43%) responded to the study survey. Two patients indicated they did not have chronic back pain and were excluded. Patients had a median (IQR) age of 66 (20) years, with 66 self-identifying as White (80%), 69 as male (83%), and 66 as non-Hispanic (80%). Forty-four patients (53%) received care at CBOCs. Forty-seven patients reported excellent, very good, or good overall health (57%), while 53 reported excellent, very good, or good mental health (64%). Fifty-nine patients reported back pain duration > 5 years (71%), and 67 (81%) indicated experiencing back pain flare-ups at least once per week over the previous 12 months. Sixty patients (72%) indicated they were somewhat or very interested in using integrative therapies as a back pain treatment; however, 40 patients (48%) indicated they had not received information about these therapies. Among those who indicated they had received information, the most frequently reported source was their PCP (41%). Most patients (72%) also reported feeling somewhat to very comfortable discussing integrative medicine therapies with their PCP.

Integrative Therapy Recommendations and Use

PCPs reported recommending multiple integrative modalities: 23 (82%) recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy, 22 (79%) recommended acupuncture, 21 (75%) recommended chiropractic, 19 (68%) recommended battlefield acupuncture, recommended massage 18 (64%), 17 (61%) recommended meditation or mindfulness, and 15 (54%) recommended movement therapies such as yoga or tai chi/qigong (Figure 1). The only therapies used by at least half of the patients were chiropractic used by 59 patients (71%) and acupuncture by 42 patients (51%). Thirty-eight patients (46%) reported massage use and 21 patients (25%) used cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 2).

Integrative Therapies Desired

A majority of PCPs identified acupuncture (n = 20, 71%), chiropractic (n = 19, 68%), and massage (n = 19, 68%) as therapies they would most like to have available for patients with chronic pain (Figure 2). Similarly, patients identified massage (n = 42, 51%), chiropractic (n = 34, 41%), and acupuncture (n = 27, 33%) as most desired. Seventeen patients (21%) expressed interest in movement therapies.

Barriers to Integrative Therapies Use

When asked about barriers to use, 26 PCPs (93%) identified access to services as a somewhat or extremely likely barrier, and 22 identified time constraints (79%) (Table 3). However, 17 PCPs (61%) noted lack of familiarity, and 18 (64%) noted a lack of scientific evidence as barriers to recommending integrative modalities. Among patients, 33 (40%) indicated not knowing what services were available at their facility as a barrier, 32 (39%) were not familiar with specific therapies, and 21 (25%) indicated a lack of clarity about the benefits of a specific therapy. Only 14 patients (17%) indicated that there were no obstacles to use.

DISCUSSION

Use of integrative therapies, including complementary treatments, is an increasingly important part of chronic pain management. This survey study suggests VA PCPs are willing to recommend integrative therapies and patients with chronic back pain both desire and use several therapies. Moreover, both groups expressed interest in greater availability of similar therapies. The results also highlight key barriers, such as knowledge gaps, that should be addressed to increase the uptake of integrative modalities for managing chronic pain.

An increasing number of US adults are using complementary health approaches, an important component of integrative therapy.12 This trend includes an increase in use for pain management, from 42.3% in 2002 to 49.2% in 2022; chiropractic care, acupuncture, and massage were most frequently used.12 Similarly, chiropractic, acupuncture and massage were most often used by this sample of veterans with chronic back pain and were identified by the highest percentages of PCPs and patients as the therapies they would most like available.

There were areas where the opinions of patients and clinicians differed. As has been seen previously reported, clinicians largely recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy while patients showed less interest.17 Additionally, while patients expressed interest in the availability of movement therapies, such as yoga, PCPs expressed more interest in other strategies, such as trigger point injections. These differences may reflect true preference or a tendency for clinicians and patients to select therapies with which they are more familiar. Additional research is needed to better understand the acceptability and potential use of integrative health treatments across a broad array of therapeutic options.

Despite VHA policy requiring facilities to provide certain complementary and integrative health modalities, almost all PCPs identified access to services as a major obstacle.15 Based on evidence and a rigorous vetting process, services currently required on-site, via telehealth, or through community partners include acupuncture and battlefield acupuncture (battlefield auricular acupuncture), biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, guided imagery, medical massage therapy, medication, tai chi/qigong, and yoga. Optional approaches, which may be made available to veterans, include chiropractic and healing touch. Outside the VHA, some states have introduced or enacted legislation mandating insurance coverage of nonpharmacological pain treatments.18 However, these requirements and mandates do not help address challenges such as the availability of trained/qualified practitioners.19,20 Ensuring access to complementary and integrative health treatments requires a more concerted effort to ensure that supply meets demand. It is also important to acknowledge the budgetary and physical space constraints that further limit access to services. Although expansion and integration of integrative medicine services remain a priority within the VA Whole Health program, implementation is contingent on available financial and infrastructure resources.

Time was also identified by PCPs as a barrier to recommending integrative therapies to patients. Developing and implementing time-efficient communication strategies for patient education such as concise talking points and informational handouts could help address this barrier. Furthermore, leveraging existing programs and engaging the entire health care team in patient education and referral could help increase integrative and complementary therapy uptake and use.

Although access and time were identified as major barriers, these findings also suggest that PCP and patient knowledge are another target area for enhancing the use of complementary and integrative therapies. Like prior research, most clinicians identified a lack of familiarity with certain services and a lack of scientific evidence as extremely or somewhat likely to affect their ability to offer integrative services to patients with chronic pain.21 Likewise, about 40% of patients identified being unfamiliar with a specific therapy as one of the major obstacles to receiving integrative therapies, with a similar number identifying PCPs as a source of information. The lack of familiarity may be due in part to the evolving nomenclature, with terms such as alternative, complementary, and integrative used to describe approaches outside what is often considered conventional medicine.10 On the other hand, there has also been considerable expansion in the number of therapies within this domain, along with an expanding evidence base. This suggests a need for targeted educational strategies for clinicians and patients, which can be rapidly deployed and continuously adapted as new therapies and evidence emerge.

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations with a survey-based approach, including sampling, non-response, and social desirability biases. In addition, this study only included PCPs and patients affiliated with a single VA medical center. Steps to mitigate these limitations included maintaining survey anonymity and reporting information about respondent characteristics to enhance transparency about the representativeness of the study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanding the use of nonpharmacological pain treatments, including integrative modalities, is essential for safe and effective chronic pain management and reducing opioid use. Our findings show that VA PCPs and patients with chronic back pain are interested in and have some experience with certain integrative therapies. However, even within the context of a health care system that supports the use of integrative therapies for chronic pain as part of whole person care, increasing uptake will require addressing access and time-related constraints as well as ongoing clinician and patient education.

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, et al. Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2018-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022;163:E328-E332. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291

- Nahin RL, Feinberg T, Kapos FP, Terman GW. Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2313563. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13563

- Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024;403:2133-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 5.

- Qureshi AR, Patel M, Neumark S, et al. Prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain among military veterans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Mil Health. 2025;171:310-314. doi:10.1136/military-2023-002554

- Feldman DE, Nahin RL. Disability among persons with chronic severe back pain: results from a nationally representative population-based sample. J Pain. 2022;23:2144-2154. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.016

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, Kleijnen J, Smeets RJEM. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Practice. 2019;19:224-241. doi:10.1111/papr.12735

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505. doi:10.7326/M16-2459

- Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Updated April 2021. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name.

- Taylor SL, Elwy AR. Complementary and alternative medicine for US veterans and active duty military personnel promising steps to improve their health. Med Care. 2014;52:S1-S4. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000270.

- Nahin RL, Rhee A, Stussman B. Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by US adults. JAMA. 2024;331:613-615. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26775

- Gantt CJ, Donovan N, Khung M. Veterans Affairs’ Whole Health System of Care for transitioning service members and veterans. Mil Med. 2023;188:28-32. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad047

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the Whole Health System of Care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57:53-65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938

- Department of Veterans Affairs VHA. VHA Policy Directive 1137: Provision of Complementary and Integrative Health. December 2022. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10072

- Giannitrapani KF, Holliday JR, Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Taylor SL. Synthesizing the strength of the evidence of complementary and integrative health therapies for pain. Pain Med. 2019;20:1831-1840. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz068

- Belitskaya-Levy I, David Clark J, Shih MC, Bair MJ. Treatment preferences for chronic low back pain: views of veterans and their providers. J Pain Res. 2021;14:161-171. doi:10.2147/JPR.S290400

- Onstott TN, Hurst S, Kronick R, Tsou AC, Groessl E, McMenamin SB. Health insurance mandates for nonpharmacological pain treatments in 7 US states. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:E245737. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5737

- Sullivan M, Leach M, Snow J, Moonaz S. The North American yoga therapy workforce survey. Complement Ther Med. 2017;31:39-48. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.01.006

- Bolton R, Ritter G, Highland K, Larson MJ. The relationship between capacity and utilization of nonpharmacologic therapies in the US Military Health System. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-07700-4

- Stussman BJ, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Scott R, Feinberg T, Ward BW. Reasons office-based physicians in the United States recommend common complementary health approaches to patients: an exploratory study using a national survey. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28:651-663. doi:10.1089/jicm.2022.0493

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, et al. Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2018-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022;163:E328-E332. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291

- Nahin RL, Feinberg T, Kapos FP, Terman GW. Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2313563. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13563

- Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024;403:2133-2161. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 5.

- Qureshi AR, Patel M, Neumark S, et al. Prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain among military veterans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Mil Health. 2025;171:310-314. doi:10.1136/military-2023-002554

- Feldman DE, Nahin RL. Disability among persons with chronic severe back pain: results from a nationally representative population-based sample. J Pain. 2022;23:2144-2154. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.016

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, Kleijnen J, Smeets RJEM. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Practice. 2019;19:224-241. doi:10.1111/papr.12735

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505. doi:10.7326/M16-2459

- Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Updated April 2021. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name.

- Taylor SL, Elwy AR. Complementary and alternative medicine for US veterans and active duty military personnel promising steps to improve their health. Med Care. 2014;52:S1-S4. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000270.

- Nahin RL, Rhee A, Stussman B. Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by US adults. JAMA. 2024;331:613-615. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26775

- Gantt CJ, Donovan N, Khung M. Veterans Affairs’ Whole Health System of Care for transitioning service members and veterans. Mil Med. 2023;188:28-32. doi:10.1093/milmed/usad047