User login

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

You’re stuck in your house. Work is closed or you’re working remotely. Your kids’ school is closed or is offering an hour or two a day of Zoom-based instruction. You have a bit of cabin fever which, you suppose, is better than the actual fever that comes with COVID infections, which are running rampant during the height of the pandemic. But still — it’s stressful. What do you do?

We all coped in our own way. We baked sourdough bread. We built that tree house we’d been meaning to build. We started podcasts. And ... we drank. Quite a bit, actually.

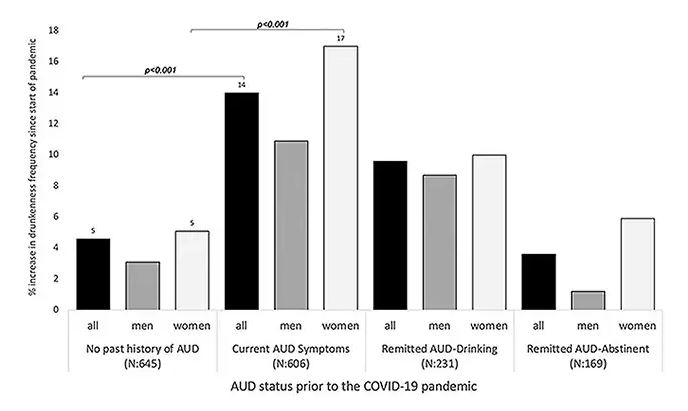

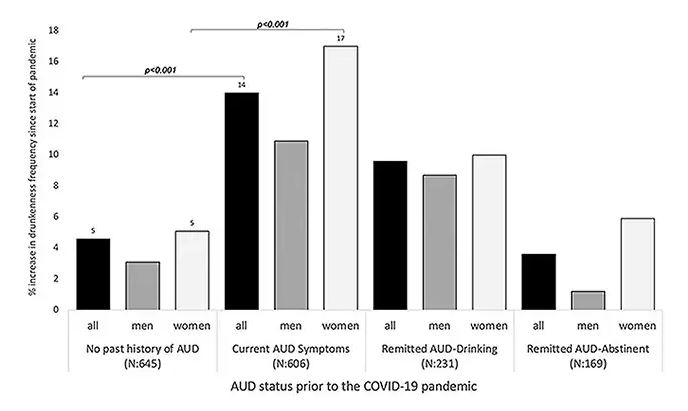

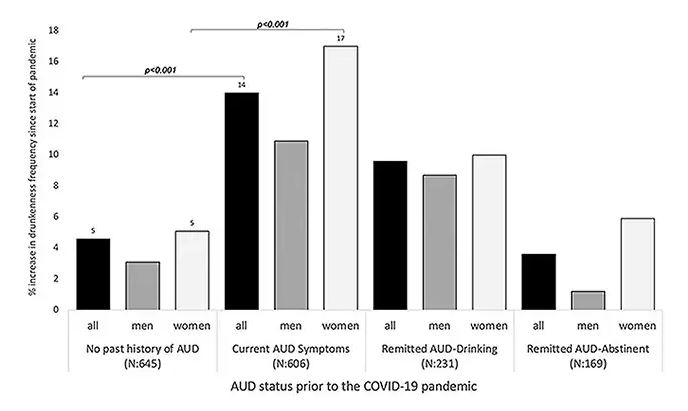

During the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales increased 3%, the largest year-on-year increase in more than 50 years. There was also an increase in drunkenness across the board, though it was most pronounced in those who were already at risk from alcohol use disorder.

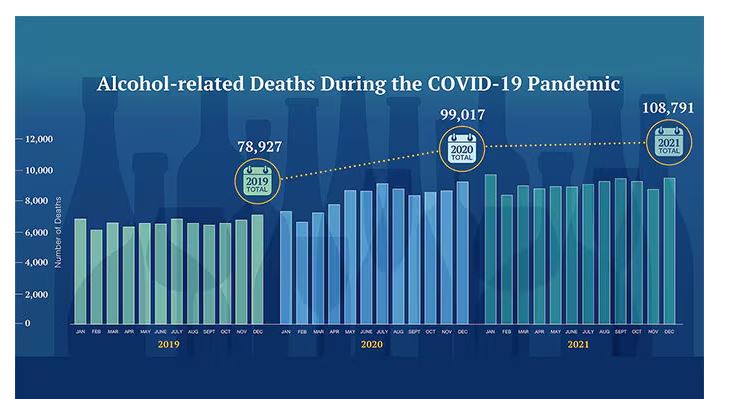

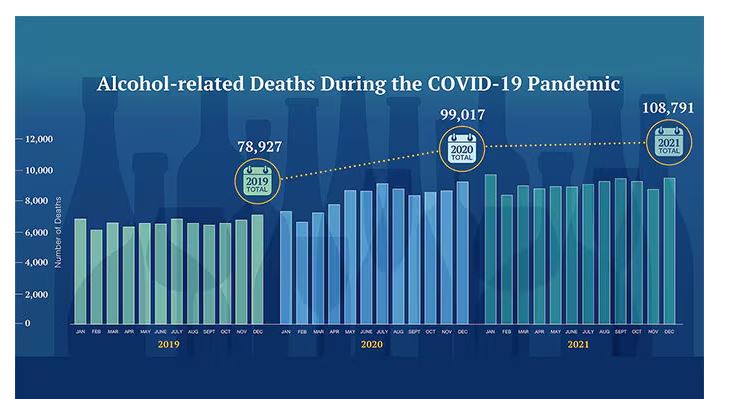

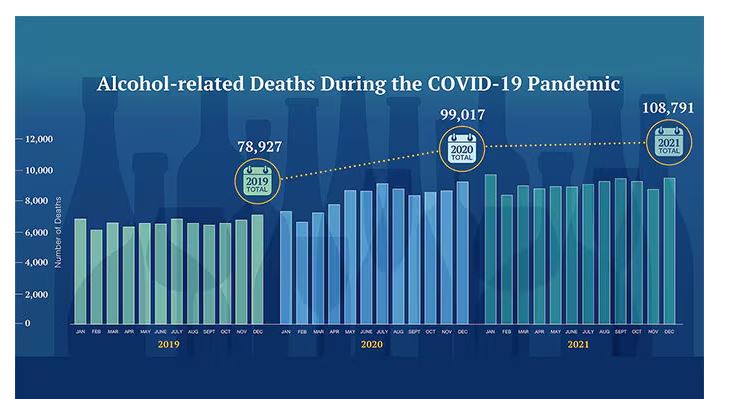

Alcohol-associated deaths increased by around 10% from 2019 to 2020. Obviously, this is a small percentage of COVID-associated deaths, but it is nothing to sneeze at.

But look, we were anxious. And say what you will about alcohol as a risk factor for liver disease, heart disease, and cancer — not to mention traffic accidents — it is an anxiolytic, at least in the short term.

But as the pandemic waned, as society reopened, as we got back to work and reintegrated into our social circles and escaped the confines of our houses and apartments, our drinking habits went back to normal, right?

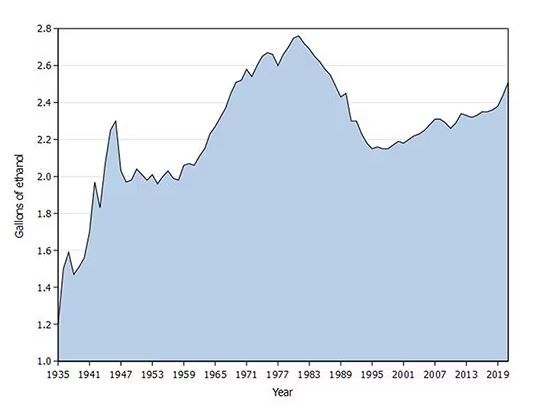

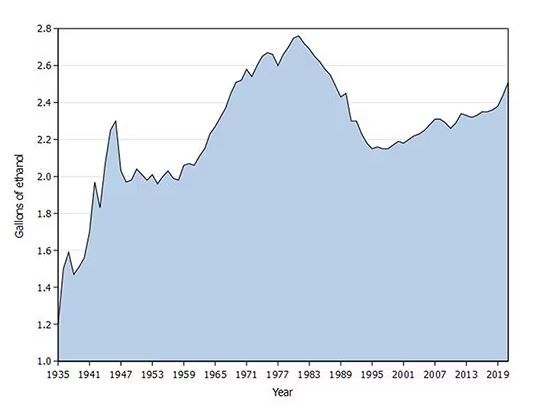

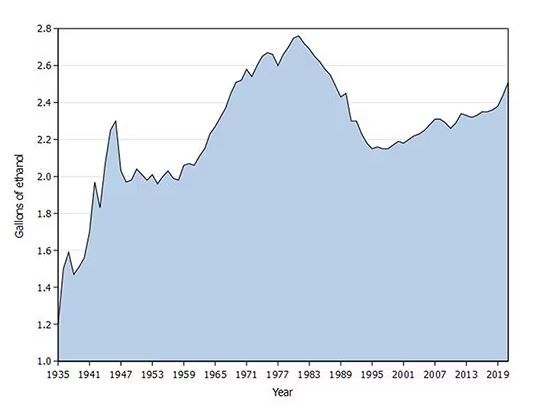

Americans’ love affair with alcohol has been a torrid one, as this graph showing gallons of ethanol consumed per capita over time shows you.

What you see is a steady increase in alcohol consumption from the end of prohibition in 1933 to its peak in the heady days of the early 1980s, followed by a steady decline until the mid-1990s. Since then, there has been another increase with, as you will note, a notable uptick during the early part of the COVID pandemic.

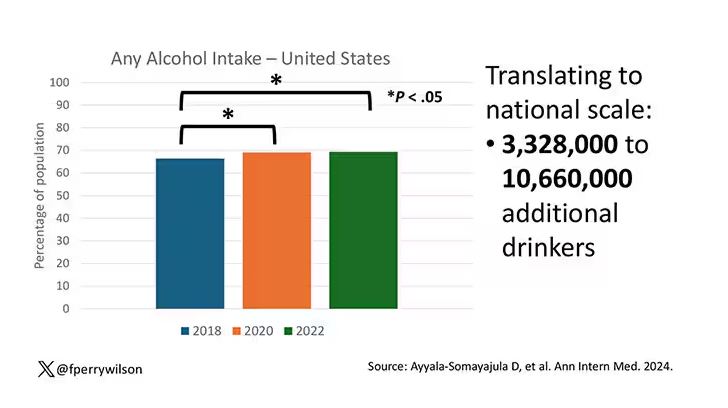

What came across my desk this week was updated data, appearing in a research letter in Annals of Internal Medicine, that compared alcohol consumption in 2020 — the first year of the COVID pandemic — with that in 2022 (the latest available data). And it looks like not much has changed.

This was a population-based survey study leveraging the National Health Interview Survey, including around 80,000 respondents from 2018, 2020, and 2022.

They created two main categories of drinking: drinking any alcohol at all and heavy drinking.

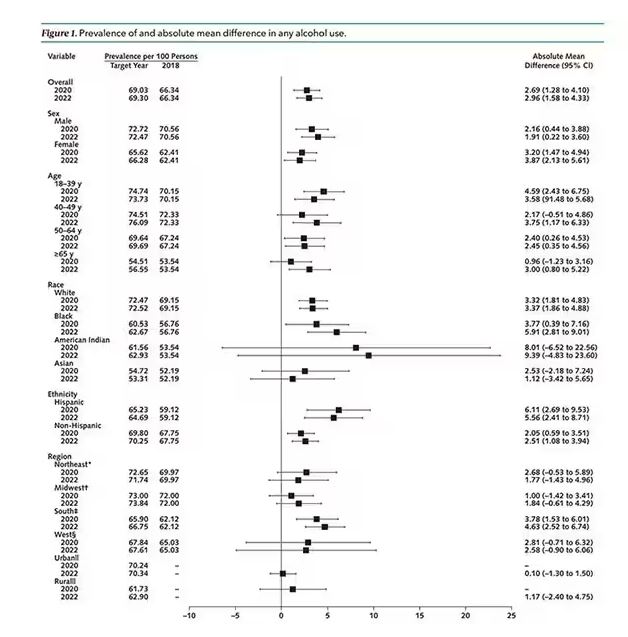

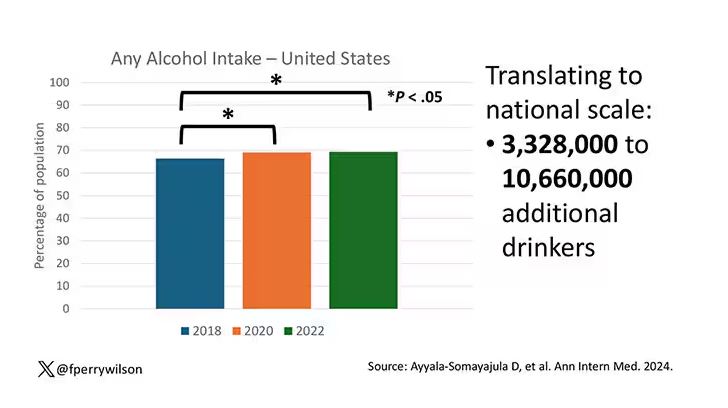

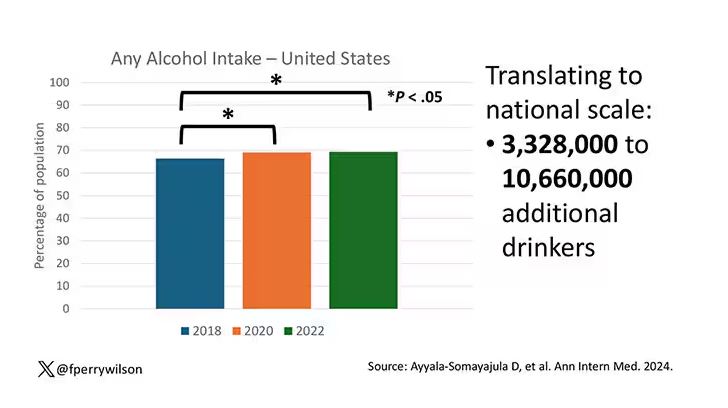

In 2018, 66% of Americans reported drinking any alcohol. That had risen to 69% by 2020, and it stayed at that level even after the lockdown had ended, as you can see here. This may seem like a small increase, but this was a highly significant result. Translating into absolute numbers, it suggests that we have added between 3,328,000 and 10,660,000 net additional drinkers to the population over this time period.

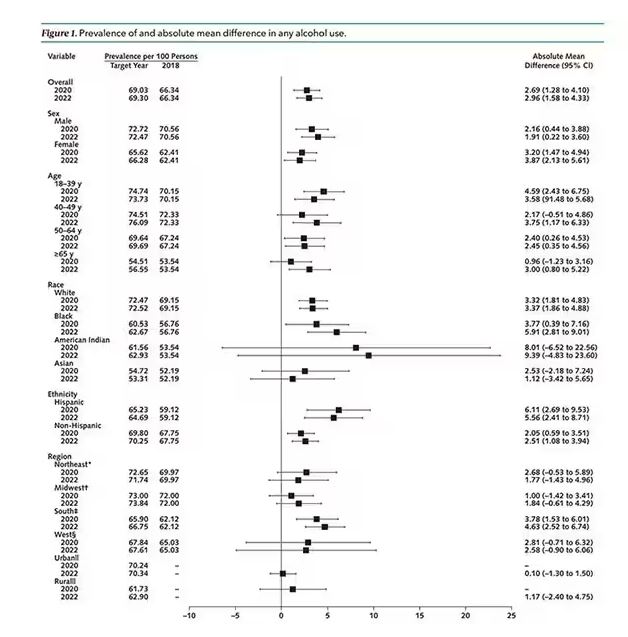

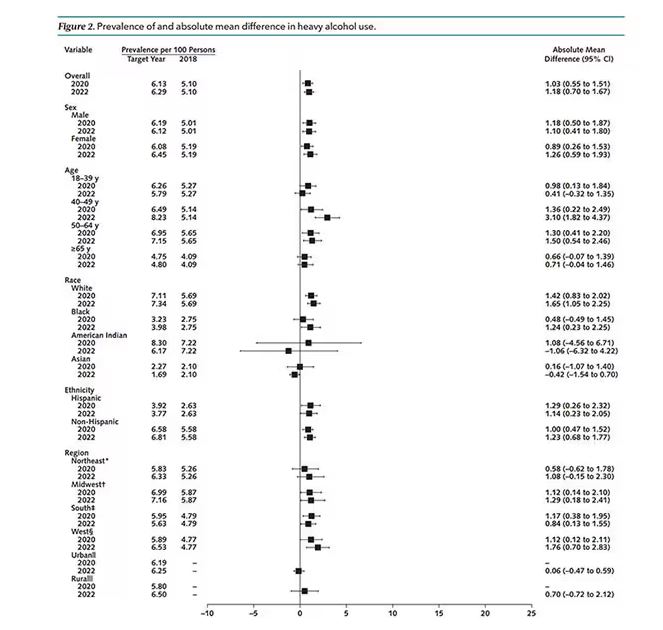

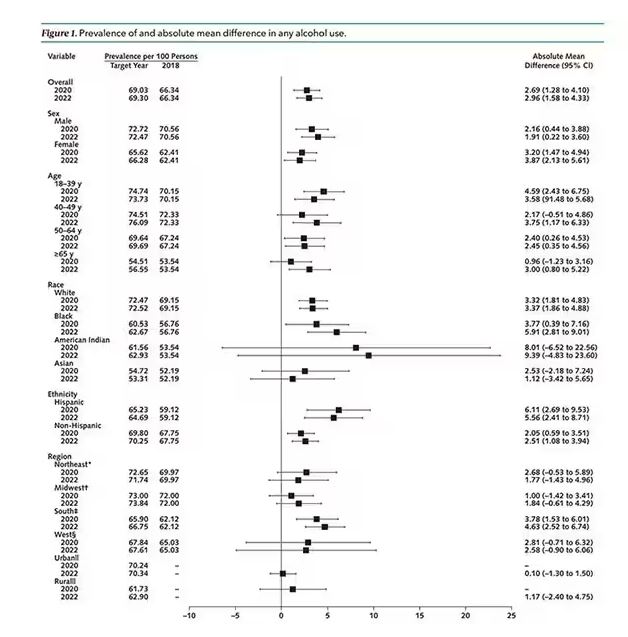

This trend was seen across basically every demographic group, with some notably larger increases among Black and Hispanic individuals, and marginally higher rates among people under age 30.

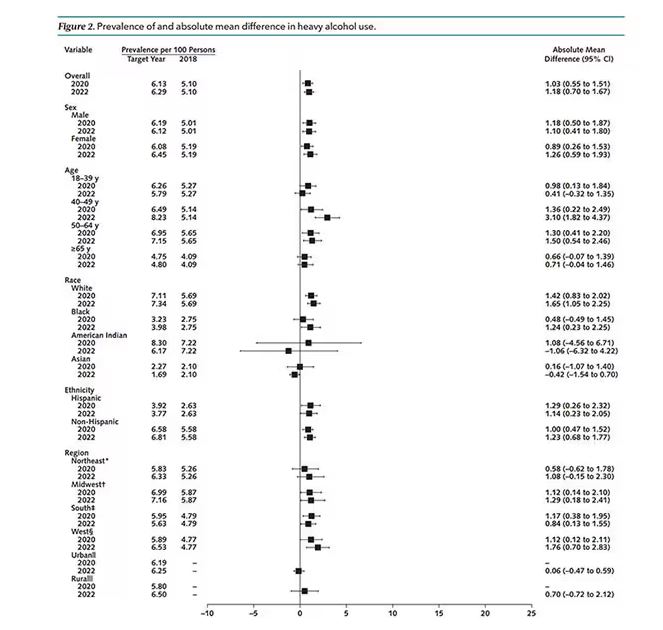

But far be it from me to deny someone a tot of brandy on a cold winter’s night. More interesting is the rate of heavy alcohol use reported in the study. For context, the definitions of heavy alcohol use appear here. For men, it’s any one day with five or more drinks or 15 or more drinks per week. For women it’s four or more drinks on a given day or eight drinks or more per week.

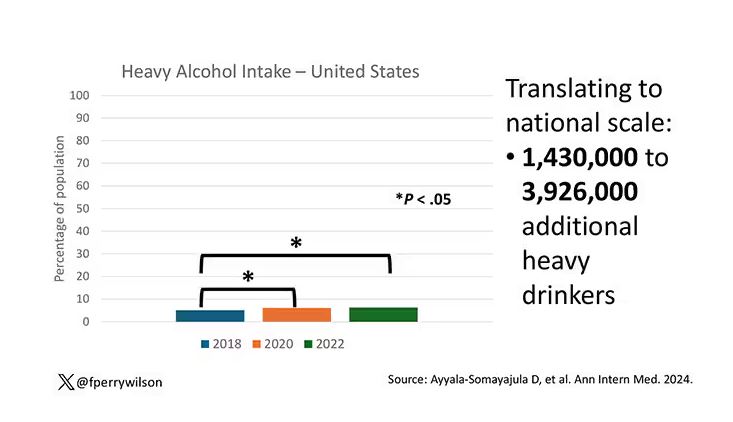

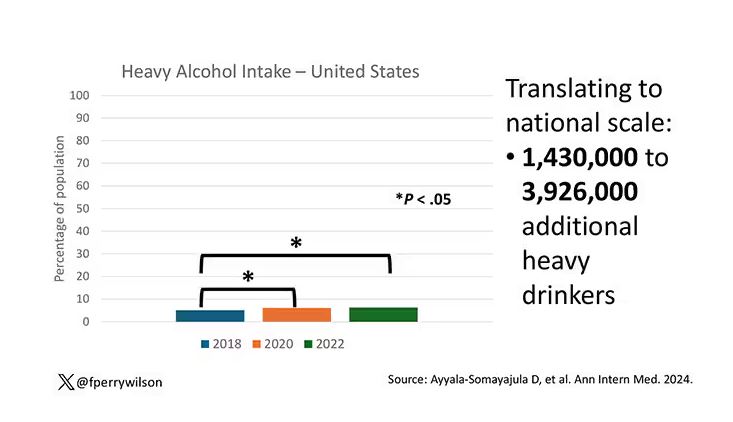

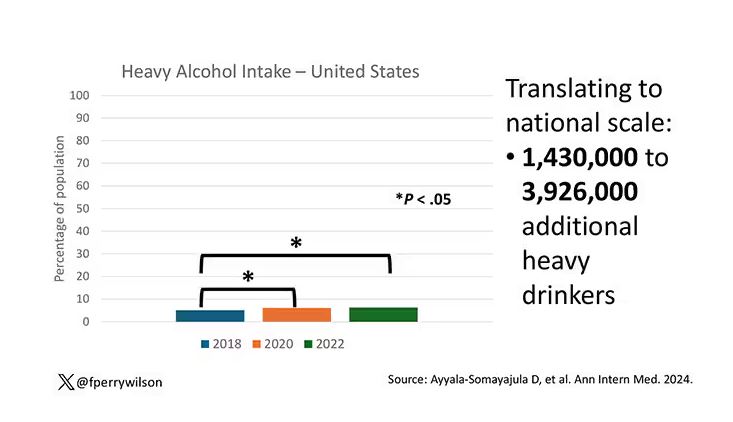

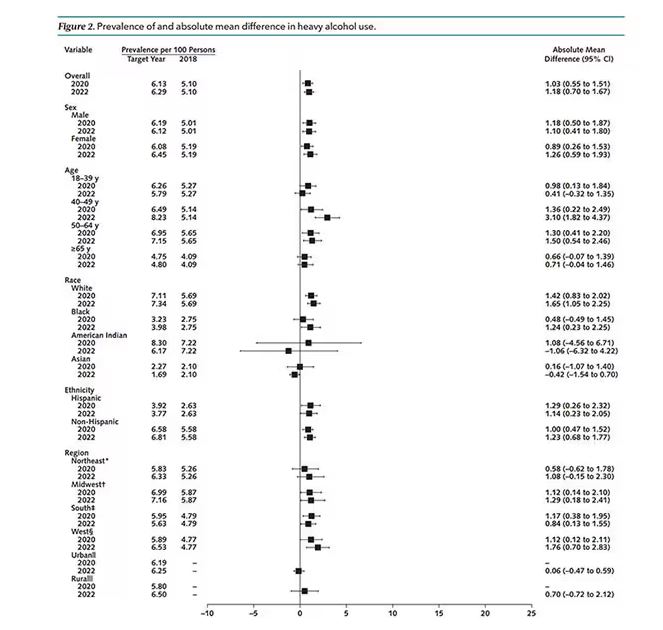

The overall rate of heavy drinking was about 5.1% in 2018 before the start of the pandemic. That rose to more than 6% in 2020 and it rose a bit more into 2022. The net change here, on a population level, is from 1,430,000 to 3,926,000 new heavy drinkers. That’s a number that rises to the level of an actual public health issue.

Again, this trend was fairly broad across demographic groups. Although in this case, the changes were a bit larger among White people and those in the 40- to 49-year age group. This is my cohort, I guess. Cheers.

The information we have from this study is purely descriptive. It tells us that people are drinking more since the pandemic. It doesn’t tell us why, or the impact that this excess drinking will have on subsequent health outcomes, although other studies would suggest that it will contribute to certain chronic conditions, both physical and mental.

Maybe more important is that it reminds us that habits are sticky. Once we become accustomed to something — that glass of wine or two with dinner, and before bed — it has a tendency to stay with us. There’s an upside to that phenomenon as well, of course; it means that we can train good habits too. And those, once they become ingrained, can be just as hard to break. We just need to be mindful of the habits we pick. New Year 2025 is just around the corner. Start brainstorming those resolutions now.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

You’re stuck in your house. Work is closed or you’re working remotely. Your kids’ school is closed or is offering an hour or two a day of Zoom-based instruction. You have a bit of cabin fever which, you suppose, is better than the actual fever that comes with COVID infections, which are running rampant during the height of the pandemic. But still — it’s stressful. What do you do?

We all coped in our own way. We baked sourdough bread. We built that tree house we’d been meaning to build. We started podcasts. And ... we drank. Quite a bit, actually.

During the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales increased 3%, the largest year-on-year increase in more than 50 years. There was also an increase in drunkenness across the board, though it was most pronounced in those who were already at risk from alcohol use disorder.

Alcohol-associated deaths increased by around 10% from 2019 to 2020. Obviously, this is a small percentage of COVID-associated deaths, but it is nothing to sneeze at.

But look, we were anxious. And say what you will about alcohol as a risk factor for liver disease, heart disease, and cancer — not to mention traffic accidents — it is an anxiolytic, at least in the short term.

But as the pandemic waned, as society reopened, as we got back to work and reintegrated into our social circles and escaped the confines of our houses and apartments, our drinking habits went back to normal, right?

Americans’ love affair with alcohol has been a torrid one, as this graph showing gallons of ethanol consumed per capita over time shows you.

What you see is a steady increase in alcohol consumption from the end of prohibition in 1933 to its peak in the heady days of the early 1980s, followed by a steady decline until the mid-1990s. Since then, there has been another increase with, as you will note, a notable uptick during the early part of the COVID pandemic.

What came across my desk this week was updated data, appearing in a research letter in Annals of Internal Medicine, that compared alcohol consumption in 2020 — the first year of the COVID pandemic — with that in 2022 (the latest available data). And it looks like not much has changed.

This was a population-based survey study leveraging the National Health Interview Survey, including around 80,000 respondents from 2018, 2020, and 2022.

They created two main categories of drinking: drinking any alcohol at all and heavy drinking.

In 2018, 66% of Americans reported drinking any alcohol. That had risen to 69% by 2020, and it stayed at that level even after the lockdown had ended, as you can see here. This may seem like a small increase, but this was a highly significant result. Translating into absolute numbers, it suggests that we have added between 3,328,000 and 10,660,000 net additional drinkers to the population over this time period.

This trend was seen across basically every demographic group, with some notably larger increases among Black and Hispanic individuals, and marginally higher rates among people under age 30.

But far be it from me to deny someone a tot of brandy on a cold winter’s night. More interesting is the rate of heavy alcohol use reported in the study. For context, the definitions of heavy alcohol use appear here. For men, it’s any one day with five or more drinks or 15 or more drinks per week. For women it’s four or more drinks on a given day or eight drinks or more per week.

The overall rate of heavy drinking was about 5.1% in 2018 before the start of the pandemic. That rose to more than 6% in 2020 and it rose a bit more into 2022. The net change here, on a population level, is from 1,430,000 to 3,926,000 new heavy drinkers. That’s a number that rises to the level of an actual public health issue.

Again, this trend was fairly broad across demographic groups. Although in this case, the changes were a bit larger among White people and those in the 40- to 49-year age group. This is my cohort, I guess. Cheers.

The information we have from this study is purely descriptive. It tells us that people are drinking more since the pandemic. It doesn’t tell us why, or the impact that this excess drinking will have on subsequent health outcomes, although other studies would suggest that it will contribute to certain chronic conditions, both physical and mental.

Maybe more important is that it reminds us that habits are sticky. Once we become accustomed to something — that glass of wine or two with dinner, and before bed — it has a tendency to stay with us. There’s an upside to that phenomenon as well, of course; it means that we can train good habits too. And those, once they become ingrained, can be just as hard to break. We just need to be mindful of the habits we pick. New Year 2025 is just around the corner. Start brainstorming those resolutions now.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

You’re stuck in your house. Work is closed or you’re working remotely. Your kids’ school is closed or is offering an hour or two a day of Zoom-based instruction. You have a bit of cabin fever which, you suppose, is better than the actual fever that comes with COVID infections, which are running rampant during the height of the pandemic. But still — it’s stressful. What do you do?

We all coped in our own way. We baked sourdough bread. We built that tree house we’d been meaning to build. We started podcasts. And ... we drank. Quite a bit, actually.

During the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales increased 3%, the largest year-on-year increase in more than 50 years. There was also an increase in drunkenness across the board, though it was most pronounced in those who were already at risk from alcohol use disorder.

Alcohol-associated deaths increased by around 10% from 2019 to 2020. Obviously, this is a small percentage of COVID-associated deaths, but it is nothing to sneeze at.

But look, we were anxious. And say what you will about alcohol as a risk factor for liver disease, heart disease, and cancer — not to mention traffic accidents — it is an anxiolytic, at least in the short term.

But as the pandemic waned, as society reopened, as we got back to work and reintegrated into our social circles and escaped the confines of our houses and apartments, our drinking habits went back to normal, right?

Americans’ love affair with alcohol has been a torrid one, as this graph showing gallons of ethanol consumed per capita over time shows you.

What you see is a steady increase in alcohol consumption from the end of prohibition in 1933 to its peak in the heady days of the early 1980s, followed by a steady decline until the mid-1990s. Since then, there has been another increase with, as you will note, a notable uptick during the early part of the COVID pandemic.

What came across my desk this week was updated data, appearing in a research letter in Annals of Internal Medicine, that compared alcohol consumption in 2020 — the first year of the COVID pandemic — with that in 2022 (the latest available data). And it looks like not much has changed.

This was a population-based survey study leveraging the National Health Interview Survey, including around 80,000 respondents from 2018, 2020, and 2022.

They created two main categories of drinking: drinking any alcohol at all and heavy drinking.

In 2018, 66% of Americans reported drinking any alcohol. That had risen to 69% by 2020, and it stayed at that level even after the lockdown had ended, as you can see here. This may seem like a small increase, but this was a highly significant result. Translating into absolute numbers, it suggests that we have added between 3,328,000 and 10,660,000 net additional drinkers to the population over this time period.

This trend was seen across basically every demographic group, with some notably larger increases among Black and Hispanic individuals, and marginally higher rates among people under age 30.

But far be it from me to deny someone a tot of brandy on a cold winter’s night. More interesting is the rate of heavy alcohol use reported in the study. For context, the definitions of heavy alcohol use appear here. For men, it’s any one day with five or more drinks or 15 or more drinks per week. For women it’s four or more drinks on a given day or eight drinks or more per week.

The overall rate of heavy drinking was about 5.1% in 2018 before the start of the pandemic. That rose to more than 6% in 2020 and it rose a bit more into 2022. The net change here, on a population level, is from 1,430,000 to 3,926,000 new heavy drinkers. That’s a number that rises to the level of an actual public health issue.

Again, this trend was fairly broad across demographic groups. Although in this case, the changes were a bit larger among White people and those in the 40- to 49-year age group. This is my cohort, I guess. Cheers.

The information we have from this study is purely descriptive. It tells us that people are drinking more since the pandemic. It doesn’t tell us why, or the impact that this excess drinking will have on subsequent health outcomes, although other studies would suggest that it will contribute to certain chronic conditions, both physical and mental.

Maybe more important is that it reminds us that habits are sticky. Once we become accustomed to something — that glass of wine or two with dinner, and before bed — it has a tendency to stay with us. There’s an upside to that phenomenon as well, of course; it means that we can train good habits too. And those, once they become ingrained, can be just as hard to break. We just need to be mindful of the habits we pick. New Year 2025 is just around the corner. Start brainstorming those resolutions now.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.