User login

How to explain physician compounding to legislators

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Finding Your Voice in Advocacy

Dear Friends,

Since moving to Missouri a little over 2 years ago, I got involved with the Missouri GI Society. They held their inaugural in-person meeting in September, and it was exciting to see and meet gastroenterologists and associates from all over the state. The meeting sparked conversations about challenges in practices and ways to improve patient care. It was incredibly inspiring to see the beginnings and bright future of a society motivated to mobilize change in the community. On a national scale, AGA Advocacy Day 2025 this fall was another example of how to make an impact for the field. I am grateful that local and national GI communities can be a platform for our voices.

In this issue’s “In Focus,” Dr. Colleen R. Kelly discusses the approach for weight management for the gastroenterologist, including how to discuss lifestyle modifications, anti-obesity medications, endoscopic therapies, and bariatric surgeries. In the “Short Clinical Review,” Dr. Ekta Gupta, Dr. Carol Burke, and Dr. Carole Macaron review available non-invasive blood and stool tests for colorectal cancer screening, including guidelines recommendations and evidence supporting each modality.

In the “Early Career” section, Dr. Mayada Ismail shares her personal journey in making the difficult decision of leaving her first job as an early career gastroenterologist, outlining the challenges and lessons learned along the way.

Dr. Alicia Muratore, Dr. Emily V. Wechsler, and Dr. Eric D. Shah provide a practical guide to tech and device development in the “Finance/Legal” section of this issue, outlining everything from intellectual property ownership to building the right team, and selecting the right incubator.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me (tjudy@wustl.edu) or Danielle Kiefer (dkiefer@gastro.org), Communications/Managing Editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer was only first introduced in the mid-1990s with Medicare coverage for high-risk individuals starting in 1998, followed by coverage for average-risk patients in 2001.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

Since moving to Missouri a little over 2 years ago, I got involved with the Missouri GI Society. They held their inaugural in-person meeting in September, and it was exciting to see and meet gastroenterologists and associates from all over the state. The meeting sparked conversations about challenges in practices and ways to improve patient care. It was incredibly inspiring to see the beginnings and bright future of a society motivated to mobilize change in the community. On a national scale, AGA Advocacy Day 2025 this fall was another example of how to make an impact for the field. I am grateful that local and national GI communities can be a platform for our voices.

In this issue’s “In Focus,” Dr. Colleen R. Kelly discusses the approach for weight management for the gastroenterologist, including how to discuss lifestyle modifications, anti-obesity medications, endoscopic therapies, and bariatric surgeries. In the “Short Clinical Review,” Dr. Ekta Gupta, Dr. Carol Burke, and Dr. Carole Macaron review available non-invasive blood and stool tests for colorectal cancer screening, including guidelines recommendations and evidence supporting each modality.

In the “Early Career” section, Dr. Mayada Ismail shares her personal journey in making the difficult decision of leaving her first job as an early career gastroenterologist, outlining the challenges and lessons learned along the way.

Dr. Alicia Muratore, Dr. Emily V. Wechsler, and Dr. Eric D. Shah provide a practical guide to tech and device development in the “Finance/Legal” section of this issue, outlining everything from intellectual property ownership to building the right team, and selecting the right incubator.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me (tjudy@wustl.edu) or Danielle Kiefer (dkiefer@gastro.org), Communications/Managing Editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer was only first introduced in the mid-1990s with Medicare coverage for high-risk individuals starting in 1998, followed by coverage for average-risk patients in 2001.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

Since moving to Missouri a little over 2 years ago, I got involved with the Missouri GI Society. They held their inaugural in-person meeting in September, and it was exciting to see and meet gastroenterologists and associates from all over the state. The meeting sparked conversations about challenges in practices and ways to improve patient care. It was incredibly inspiring to see the beginnings and bright future of a society motivated to mobilize change in the community. On a national scale, AGA Advocacy Day 2025 this fall was another example of how to make an impact for the field. I am grateful that local and national GI communities can be a platform for our voices.

In this issue’s “In Focus,” Dr. Colleen R. Kelly discusses the approach for weight management for the gastroenterologist, including how to discuss lifestyle modifications, anti-obesity medications, endoscopic therapies, and bariatric surgeries. In the “Short Clinical Review,” Dr. Ekta Gupta, Dr. Carol Burke, and Dr. Carole Macaron review available non-invasive blood and stool tests for colorectal cancer screening, including guidelines recommendations and evidence supporting each modality.

In the “Early Career” section, Dr. Mayada Ismail shares her personal journey in making the difficult decision of leaving her first job as an early career gastroenterologist, outlining the challenges and lessons learned along the way.

Dr. Alicia Muratore, Dr. Emily V. Wechsler, and Dr. Eric D. Shah provide a practical guide to tech and device development in the “Finance/Legal” section of this issue, outlining everything from intellectual property ownership to building the right team, and selecting the right incubator.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me (tjudy@wustl.edu) or Danielle Kiefer (dkiefer@gastro.org), Communications/Managing Editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer was only first introduced in the mid-1990s with Medicare coverage for high-risk individuals starting in 1998, followed by coverage for average-risk patients in 2001.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Non-Invasive Blood and Stool CRC Screening Tests: Available Modalities and Their Clinical Application

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening significantly reduces CRC incidence and mortality, but only 65% of eligible individuals report being up-to-date with screening.1 Colonoscopy is the most widely used opportunistic screening method in the United States and is associated with many barriers to uptake. Providing patients a choice of colonoscopy and/or stool-based tests, improves screening adherence in randomized controlled trials.2,3 Non-invasive screening options have expanded from stool occult blood and multi-target DNA tests, to multi-target stool RNA tests, and novel blood-based tests, the latter only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for patients who refuse colonoscopy and stool-based tests.

Stool Occult Blood Tests

Guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT) significantly reduces CRC mortality by 33%-35% when implemented on an annual or biennial basis.4,5 Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) has supplanted gFOBT with advantages including independence from dietary restriction and medication-related interference, use of antibodies specific to human globin, and the need for only a single stool sample.

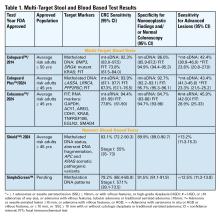

The most common threshold for a positive FIT in the U.S. is ≥ 20 micrograms (μg) of hemoglobin per gram (g) of stool. FIT is approved by the FDA as a qualitative positive or negative result based on a threshold value.6 A meta-analysis summarized test characteristics of commercially available FITs at various detection thresholds.7 The CRC sensitivity and specificity was 75% and 95% for ≥ 20 ug hemoglobin/g stool, and 91% and 90% for 10 ug hemoglobin/g stool, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas ranged from 25% at 20 μg/g to 40% at a 10 μg/g. Programmatic use of FIT in adults ages ≥ 50 years at 20 ug/g of stool, in cohort and case control studies, has been shown to significantly reduce CRC mortality by 33%-40% and advanced stage CRC by 34%.8,9

Over 57,000 average-risk individuals ages 50–69 years were randomized to biennial FIT or one-time colonoscopy and followed for 10 years.10 CRC mortality and incidence was similar between the groups: 0.22% with FIT vs. 0.24% with colonoscopy and 1.13% with FIT vs. 1.22% with colonoscopy, respectively. Thus, confirming biennial FIT screening is non-inferior to one-time colonoscopy in important CRC-related outcomes.

Multi-Target Stool Tests

Two multitarget stool DNA tests (mt-sDNA) known as Cologuard™ and Cologuard Plus™ have been approved by the FDA. Both tests include a FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin per gram of stool) combined with DNA methylation markers. The test result is qualitative, reported as a positive or negative. Cologuard™ markers include methylated BMP3, NDRG4, and mutant KRAS while Cologuard Plus™ assesses methylated LASS4, LRRC4, and PPP2R5C. The respective mt-sDNA tests were studied in 9989 of 12,776 and 20,176 of 26,758 average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy and the results were compared to a commercially available FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool).11,12 In both trials, the sensitivity for CRC and advanced precancerous lesions was higher with the mt-sDNA tests compared to FIT but had a significantly lower specificity for advanced precancerous lesions versus FIT (see Table 1). An age-related decline in specificity was noted in both trials with mt-sDNA, a trend not observed with FIT. This reduction may be attributed to age-related DNA methylation.

Multi-Target Stool RNA Test

A multi-target stool RNA test (mt-sRNA) commercially available as ColoSense™ is FDA-approved. It combines FIT (at a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool) with RNA-based stool markers. The combined results of the RNA markers, FIT, and smoking status provide a qualitative single test result. In the trial, 8,920 adults aged ≥45 underwent the mt-sRNA test and FIT followed by colonoscopy (13). The mt-sRNA showed higher sensitivity for CRC than FIT (94.4% versus 77.8%) and advanced adenomas (45.9% versus 28.9%) but lower CRC specificity (84.7% vs 94.7%) (Table 1). Unlike mt-sDNA-based tests, mt-sRNA showed consistent performance across age groups, addressing concerns about age-related declines in specificity attributed to DNA methylation.

Blood-Based Tests

In 2014, the first blood-based (BBT) CRC screening test known as Epi proColon™ was FDA but not Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved for average-risk adults ≥50 years of age who are offered and refused other U.S Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) endorsed CRC screening tests. It is a qualitative test for detection of circulating methylated Septin 9 (mSeptin9). The accuracy of mSeptin9 to detect CRC was assessed in a subset of 7941 asymptomatic average risk adults undergoing screening colonoscopy.14 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC were 48% and 91.5%, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas was 11.2%. An increase in sensitivity to 63.9% and reduction in specificity to 88.4% for CRC was demonstrated in a sub-analysis of available samples where an additional (third) polymerase chain replicate was performed. Epi proColon™ is not currently reimbursed by Medicare and not endorsed in the latest USPSTF guidelines.

Technologic advancements have improved the detection of circulating tumor markers in the blood. The Shield™ BBT approved by the FDA in 2024 for average risk adults ≥ 45 years integrates three types of cfDNA data (epigenetic changes resulting in the aberrant methylation or fragmentation patterns, and genomic changes resulting in somatic mutations) into a positive or negative test result. In the trial, 22,877 average-risk, asymptomatic individuals ages 45–84 were enrolled and clinical validation was performed in 7,861 of the participants.15 The sensitivity for CRC was 83.1% which decreased to 55% for stage I tumors (see Table 1). CRC specificity was 89.6% and the sensitivity for advanced adenomas and large sessile serrated lesions was 13.2%.

Another BBT SimpleScreen™, which is not yet FDA-approved, analyzed circulating, cell-free DNA methylation patterns in 27,010 evaluable average-risk, asymptomatic adults ages 45–85 years undergoing screening colonoscopy.16 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC was 79.2% and 91.5%, respectively. Similar to Shield, the sensitivity for stage I CRC was low at 57.1%. The sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions, a secondary endpoint, was 12.5% which did not meet the prespecified study criteria.

Effectiveness and Cost Effectiveness

Modeling studies have evaluated novel noninvasive CRC screening tests compared to FIT and colonoscopy.17-20 One compared a hypothetical BBT performed every 3 years that meets the minimum CMS threshold CRC sensitivity and specificity of 74% and 90%, respectively, to other established CRC screening tests beginning at age 45.17 Every 3-year BBT reduced CRC incidence and mortality by 40% and 52%, respectively compared to no screening. However, the reductions were much lower than yearly FIT (72% and 76%, respectively), every 10 year colonoscopy (79% and 81%, respectively), and triennial mt-sDNA (68% and 73%, respectively). The BBT resulted in fewer quality-adjusted life-years per person compared to the alternatives.

Additionally, FIT, colonoscopy, and mt-sDNA were less costly and more effective. Advanced precancerous lesion detection was a key measure for a test’s effectiveness. BBT characteristics would require a CRC sensitivity and specificity of >90% and 90%, respectively, and 80% sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions at a cost of ≤$120–$140 to be cost-effective compared to FIT at comparable participation rates.

Another analysis simulated colorectal neoplasia progression and compared clinical effectiveness and cost between annual FIT, every 3 year stool mt-sRNA, every 3 year stool mt-sDNA tests, every 3 year stool Shield™; these outcomes were compared to colonoscopy every 10 years and no screening in adults ≥ age 45 over different adherence rates.19 At real-world adherence rates of 60%, colonoscopy prevented most CRC cases and associated deaths. FIT was the most cost-effective strategy at all adherence levels. Between the multi-target stool tests and Shield™, mt-sRNA was the most cost-effective. Compared to FIT, mt-sRNA reduced CRC cases and deaths by 1% and 14%.

The third study evaluated CRC incidence and mortality, quality-adjusted life-years and costs with annual FIT, colonoscopy every 10 years, mt- sDNA tests, mt-sRNA test, and BBTs.20 The latest mt-sDNA (Colguard plus™) and mt-sRNA achieved benefits approaching FIT but the Shield™ test was substantially less effective. The authors hypothesized that if 15% of the population substituted Shield™ for current effective CRC screening strategies, an increase in CRC deaths would occur and require 9-10% of the unscreened population to uptake screening with Shield to avert the increases in CRC deaths due to the substitution effect.

Clinical Implications

The effectiveness of non-invasive screening strategies depends on their diagnostic performance, adherence, and ensuring a timely colonoscopy after a positive test. Two claims-based studies found 47.9% and 49% of patients underwent follow-up colonoscopy within 6 months of an abnormal stool or BBT CRC screening test, respectively.21-22

Conclusions

Non-invasive stool mt-sDNA and mt-sRNA have higher effectiveness than the new BBTs. BBTs can lead to increased CRC mortality if substituted for the FDA and CMS-approved, USPSTF-endorsed, CRC screening modalities. If future BBTs increase their sensitivity for CRC (including early-stage CRC) and advanced precancerous lesions and decrease their cost, they may prove to have similar cost-effectiveness to stool-based tests. Currently, BBTs are not a substitute for colonoscopy or other stool tests and should be offered to patients who refuse other CRC screening modalities. A personalized, risk-adapted approach, paired with improved adherence and follow-up are essential to optimize the population-level impact of CRC screening and ensure equitable, effective cancer prevention.

Dr. Gupta is based at the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. Dr. Burke and Dr. Macaron are based at the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Macaron declared no conflicts of interest in regard to this article. Dr. Burke declared research support from Emtora Biosciences. She is a current consultant for Lumabridge, and has been a consultant for Sebela and Almirall. She also disclosed support from Myriad, Genzyme, Ferring, Merck, Sharp and Dohme, Abbvie, Salix, and Natera.

References

1. Benavidez GA, Sedani AE, Felder TM, Asare M, Rogers CR. Rural-urban disparities and trends in cancer screening: an analysis of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data (2018-2022). JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Nov 1;8(6):pkae113

2. Galoosian A, Dai H, Croymans D, et al. Population Health Colorectal Cancer Screening Strategies in Adults Aged 45 to 49 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025 Aug 4:e2512049. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.12049. Epub ahead of print.

3. Pilonis ND, Bugajski M, Wieszczy P, et al. Participation in Competing Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Randomized Health Services Study (PICCOLINO Study). Gastroenterology. 2021 Mar;160(4):1097-1105.

4. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106–1114.

5. Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996 Nov 30;348(9040):1467-71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. PMID: 8942774.

6. Burke CA, Lieberman D, Feuerstein JD. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Approach to the Use of Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening Options: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2022 Mar;162(3):952-956. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.075. Epub 2022 Jan 28. PMID: 35094786.

7. Imperiale TF, Gruber RN Stump TE, et al. Performance characteristics of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer and advanced adenomatous polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2019; 170(5):319-329

8. Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Jensen CD, et al. Fecal Immunochemical Test Screening and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Death. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jul 1;7(7):e2423671. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.23671.

9. Chiu HM, Jen GH, Wang YW, et al. Long-term effectiveness of faecal immunochemical test screening for proximal and distal colorectal cancers. Gut. 2021 Dec;70(12):2321-2329. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322545. Epub 2021 Jan 25.

10. Castells A, Quintero E, Bujanda L, et al; COLONPREV study investigators. Effect of invitation to colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test screening on colorectal cancer mortality (COLONPREV): a pragmatic, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2025;405(10486):1231–1239

11. Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287-1297

12. Imperiale TF, Porter K, Zella J, et al. Next-Generation Multitarget Stool DNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):984-993

13. Barnell EK, Wurtzler EM, La Rocca J, et al. Multitarget Stool RNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. JAMA. 2023 Nov 14;330(18):1760-1768.

14. Church TR, Wandell M, Lofton-Day C, et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut 2014; 63:317–325.

15. Chung DC, Gray DM 2nd, Singh H, et al. A Cell-free DNA Blood-Based Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):973-983.

16. Shaukat A, Burke CA, Chan AT, et al. Clinical Validation of a Circulating Tumor DNA-Based Blood Test to Screen for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA. 2025 Jul 1;334(1):56-63.

17. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Weng Y, et al. Comparative Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer Screening with Blood-Based Biomarkers (Liquid Biopsy) vs Fecal Tests or Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2024 Jul;167(2):378-391.

18. van den Puttelaar R, Nascimento de Lima P, Knudsen AB, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with a blood test that meets the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services coverage decision. Gastroenterology 2024;167:368–377.

19. Shaukat A, Levin TR, Liang PS. Cost-effectiveness of Novel Noninvasive Screening Tests for Colorectal Neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Jun 23:S1542-3565(25)00525-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2025.06.006. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40562290.

20. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Schoen RE, Dominitz JA, Lieberman D. Projected Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Novel Molecular Blood-Based or Stool-Based Screening Tests for Colorectal Cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Dec;177(12):1610-1620.

20. Ciemins EL, Mohl JT, Moreno CA, Colangelo F, Smith RA, Barton M. Development of a Follow-Up Measure to Ensure Complete Screening for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e242693. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2693.

21. Zaki TA, Zhang NJ, Forbes SP, Raymond VM, Das AK, May FP. Colonoscopic Follow-up After Abnormal Blood-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Results. Gastroenterology. 2025 Jul 21:S0016-5085(25)05775-0. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.07.019. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40744392.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening significantly reduces CRC incidence and mortality, but only 65% of eligible individuals report being up-to-date with screening.1 Colonoscopy is the most widely used opportunistic screening method in the United States and is associated with many barriers to uptake. Providing patients a choice of colonoscopy and/or stool-based tests, improves screening adherence in randomized controlled trials.2,3 Non-invasive screening options have expanded from stool occult blood and multi-target DNA tests, to multi-target stool RNA tests, and novel blood-based tests, the latter only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for patients who refuse colonoscopy and stool-based tests.

Stool Occult Blood Tests

Guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT) significantly reduces CRC mortality by 33%-35% when implemented on an annual or biennial basis.4,5 Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) has supplanted gFOBT with advantages including independence from dietary restriction and medication-related interference, use of antibodies specific to human globin, and the need for only a single stool sample.

The most common threshold for a positive FIT in the U.S. is ≥ 20 micrograms (μg) of hemoglobin per gram (g) of stool. FIT is approved by the FDA as a qualitative positive or negative result based on a threshold value.6 A meta-analysis summarized test characteristics of commercially available FITs at various detection thresholds.7 The CRC sensitivity and specificity was 75% and 95% for ≥ 20 ug hemoglobin/g stool, and 91% and 90% for 10 ug hemoglobin/g stool, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas ranged from 25% at 20 μg/g to 40% at a 10 μg/g. Programmatic use of FIT in adults ages ≥ 50 years at 20 ug/g of stool, in cohort and case control studies, has been shown to significantly reduce CRC mortality by 33%-40% and advanced stage CRC by 34%.8,9

Over 57,000 average-risk individuals ages 50–69 years were randomized to biennial FIT or one-time colonoscopy and followed for 10 years.10 CRC mortality and incidence was similar between the groups: 0.22% with FIT vs. 0.24% with colonoscopy and 1.13% with FIT vs. 1.22% with colonoscopy, respectively. Thus, confirming biennial FIT screening is non-inferior to one-time colonoscopy in important CRC-related outcomes.

Multi-Target Stool Tests

Two multitarget stool DNA tests (mt-sDNA) known as Cologuard™ and Cologuard Plus™ have been approved by the FDA. Both tests include a FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin per gram of stool) combined with DNA methylation markers. The test result is qualitative, reported as a positive or negative. Cologuard™ markers include methylated BMP3, NDRG4, and mutant KRAS while Cologuard Plus™ assesses methylated LASS4, LRRC4, and PPP2R5C. The respective mt-sDNA tests were studied in 9989 of 12,776 and 20,176 of 26,758 average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy and the results were compared to a commercially available FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool).11,12 In both trials, the sensitivity for CRC and advanced precancerous lesions was higher with the mt-sDNA tests compared to FIT but had a significantly lower specificity for advanced precancerous lesions versus FIT (see Table 1). An age-related decline in specificity was noted in both trials with mt-sDNA, a trend not observed with FIT. This reduction may be attributed to age-related DNA methylation.

Multi-Target Stool RNA Test

A multi-target stool RNA test (mt-sRNA) commercially available as ColoSense™ is FDA-approved. It combines FIT (at a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool) with RNA-based stool markers. The combined results of the RNA markers, FIT, and smoking status provide a qualitative single test result. In the trial, 8,920 adults aged ≥45 underwent the mt-sRNA test and FIT followed by colonoscopy (13). The mt-sRNA showed higher sensitivity for CRC than FIT (94.4% versus 77.8%) and advanced adenomas (45.9% versus 28.9%) but lower CRC specificity (84.7% vs 94.7%) (Table 1). Unlike mt-sDNA-based tests, mt-sRNA showed consistent performance across age groups, addressing concerns about age-related declines in specificity attributed to DNA methylation.

Blood-Based Tests

In 2014, the first blood-based (BBT) CRC screening test known as Epi proColon™ was FDA but not Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved for average-risk adults ≥50 years of age who are offered and refused other U.S Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) endorsed CRC screening tests. It is a qualitative test for detection of circulating methylated Septin 9 (mSeptin9). The accuracy of mSeptin9 to detect CRC was assessed in a subset of 7941 asymptomatic average risk adults undergoing screening colonoscopy.14 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC were 48% and 91.5%, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas was 11.2%. An increase in sensitivity to 63.9% and reduction in specificity to 88.4% for CRC was demonstrated in a sub-analysis of available samples where an additional (third) polymerase chain replicate was performed. Epi proColon™ is not currently reimbursed by Medicare and not endorsed in the latest USPSTF guidelines.

Technologic advancements have improved the detection of circulating tumor markers in the blood. The Shield™ BBT approved by the FDA in 2024 for average risk adults ≥ 45 years integrates three types of cfDNA data (epigenetic changes resulting in the aberrant methylation or fragmentation patterns, and genomic changes resulting in somatic mutations) into a positive or negative test result. In the trial, 22,877 average-risk, asymptomatic individuals ages 45–84 were enrolled and clinical validation was performed in 7,861 of the participants.15 The sensitivity for CRC was 83.1% which decreased to 55% for stage I tumors (see Table 1). CRC specificity was 89.6% and the sensitivity for advanced adenomas and large sessile serrated lesions was 13.2%.

Another BBT SimpleScreen™, which is not yet FDA-approved, analyzed circulating, cell-free DNA methylation patterns in 27,010 evaluable average-risk, asymptomatic adults ages 45–85 years undergoing screening colonoscopy.16 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC was 79.2% and 91.5%, respectively. Similar to Shield, the sensitivity for stage I CRC was low at 57.1%. The sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions, a secondary endpoint, was 12.5% which did not meet the prespecified study criteria.

Effectiveness and Cost Effectiveness

Modeling studies have evaluated novel noninvasive CRC screening tests compared to FIT and colonoscopy.17-20 One compared a hypothetical BBT performed every 3 years that meets the minimum CMS threshold CRC sensitivity and specificity of 74% and 90%, respectively, to other established CRC screening tests beginning at age 45.17 Every 3-year BBT reduced CRC incidence and mortality by 40% and 52%, respectively compared to no screening. However, the reductions were much lower than yearly FIT (72% and 76%, respectively), every 10 year colonoscopy (79% and 81%, respectively), and triennial mt-sDNA (68% and 73%, respectively). The BBT resulted in fewer quality-adjusted life-years per person compared to the alternatives.

Additionally, FIT, colonoscopy, and mt-sDNA were less costly and more effective. Advanced precancerous lesion detection was a key measure for a test’s effectiveness. BBT characteristics would require a CRC sensitivity and specificity of >90% and 90%, respectively, and 80% sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions at a cost of ≤$120–$140 to be cost-effective compared to FIT at comparable participation rates.

Another analysis simulated colorectal neoplasia progression and compared clinical effectiveness and cost between annual FIT, every 3 year stool mt-sRNA, every 3 year stool mt-sDNA tests, every 3 year stool Shield™; these outcomes were compared to colonoscopy every 10 years and no screening in adults ≥ age 45 over different adherence rates.19 At real-world adherence rates of 60%, colonoscopy prevented most CRC cases and associated deaths. FIT was the most cost-effective strategy at all adherence levels. Between the multi-target stool tests and Shield™, mt-sRNA was the most cost-effective. Compared to FIT, mt-sRNA reduced CRC cases and deaths by 1% and 14%.

The third study evaluated CRC incidence and mortality, quality-adjusted life-years and costs with annual FIT, colonoscopy every 10 years, mt- sDNA tests, mt-sRNA test, and BBTs.20 The latest mt-sDNA (Colguard plus™) and mt-sRNA achieved benefits approaching FIT but the Shield™ test was substantially less effective. The authors hypothesized that if 15% of the population substituted Shield™ for current effective CRC screening strategies, an increase in CRC deaths would occur and require 9-10% of the unscreened population to uptake screening with Shield to avert the increases in CRC deaths due to the substitution effect.

Clinical Implications

The effectiveness of non-invasive screening strategies depends on their diagnostic performance, adherence, and ensuring a timely colonoscopy after a positive test. Two claims-based studies found 47.9% and 49% of patients underwent follow-up colonoscopy within 6 months of an abnormal stool or BBT CRC screening test, respectively.21-22

Conclusions

Non-invasive stool mt-sDNA and mt-sRNA have higher effectiveness than the new BBTs. BBTs can lead to increased CRC mortality if substituted for the FDA and CMS-approved, USPSTF-endorsed, CRC screening modalities. If future BBTs increase their sensitivity for CRC (including early-stage CRC) and advanced precancerous lesions and decrease their cost, they may prove to have similar cost-effectiveness to stool-based tests. Currently, BBTs are not a substitute for colonoscopy or other stool tests and should be offered to patients who refuse other CRC screening modalities. A personalized, risk-adapted approach, paired with improved adherence and follow-up are essential to optimize the population-level impact of CRC screening and ensure equitable, effective cancer prevention.

Dr. Gupta is based at the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. Dr. Burke and Dr. Macaron are based at the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Macaron declared no conflicts of interest in regard to this article. Dr. Burke declared research support from Emtora Biosciences. She is a current consultant for Lumabridge, and has been a consultant for Sebela and Almirall. She also disclosed support from Myriad, Genzyme, Ferring, Merck, Sharp and Dohme, Abbvie, Salix, and Natera.

References

1. Benavidez GA, Sedani AE, Felder TM, Asare M, Rogers CR. Rural-urban disparities and trends in cancer screening: an analysis of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data (2018-2022). JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Nov 1;8(6):pkae113

2. Galoosian A, Dai H, Croymans D, et al. Population Health Colorectal Cancer Screening Strategies in Adults Aged 45 to 49 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025 Aug 4:e2512049. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.12049. Epub ahead of print.

3. Pilonis ND, Bugajski M, Wieszczy P, et al. Participation in Competing Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Randomized Health Services Study (PICCOLINO Study). Gastroenterology. 2021 Mar;160(4):1097-1105.

4. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106–1114.

5. Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996 Nov 30;348(9040):1467-71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. PMID: 8942774.

6. Burke CA, Lieberman D, Feuerstein JD. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Approach to the Use of Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening Options: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2022 Mar;162(3):952-956. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.075. Epub 2022 Jan 28. PMID: 35094786.

7. Imperiale TF, Gruber RN Stump TE, et al. Performance characteristics of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer and advanced adenomatous polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2019; 170(5):319-329

8. Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Jensen CD, et al. Fecal Immunochemical Test Screening and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Death. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jul 1;7(7):e2423671. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.23671.

9. Chiu HM, Jen GH, Wang YW, et al. Long-term effectiveness of faecal immunochemical test screening for proximal and distal colorectal cancers. Gut. 2021 Dec;70(12):2321-2329. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322545. Epub 2021 Jan 25.

10. Castells A, Quintero E, Bujanda L, et al; COLONPREV study investigators. Effect of invitation to colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test screening on colorectal cancer mortality (COLONPREV): a pragmatic, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2025;405(10486):1231–1239

11. Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287-1297

12. Imperiale TF, Porter K, Zella J, et al. Next-Generation Multitarget Stool DNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):984-993

13. Barnell EK, Wurtzler EM, La Rocca J, et al. Multitarget Stool RNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. JAMA. 2023 Nov 14;330(18):1760-1768.

14. Church TR, Wandell M, Lofton-Day C, et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut 2014; 63:317–325.

15. Chung DC, Gray DM 2nd, Singh H, et al. A Cell-free DNA Blood-Based Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):973-983.

16. Shaukat A, Burke CA, Chan AT, et al. Clinical Validation of a Circulating Tumor DNA-Based Blood Test to Screen for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA. 2025 Jul 1;334(1):56-63.

17. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Weng Y, et al. Comparative Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer Screening with Blood-Based Biomarkers (Liquid Biopsy) vs Fecal Tests or Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2024 Jul;167(2):378-391.

18. van den Puttelaar R, Nascimento de Lima P, Knudsen AB, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with a blood test that meets the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services coverage decision. Gastroenterology 2024;167:368–377.

19. Shaukat A, Levin TR, Liang PS. Cost-effectiveness of Novel Noninvasive Screening Tests for Colorectal Neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Jun 23:S1542-3565(25)00525-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2025.06.006. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40562290.

20. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Schoen RE, Dominitz JA, Lieberman D. Projected Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Novel Molecular Blood-Based or Stool-Based Screening Tests for Colorectal Cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Dec;177(12):1610-1620.

20. Ciemins EL, Mohl JT, Moreno CA, Colangelo F, Smith RA, Barton M. Development of a Follow-Up Measure to Ensure Complete Screening for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e242693. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2693.

21. Zaki TA, Zhang NJ, Forbes SP, Raymond VM, Das AK, May FP. Colonoscopic Follow-up After Abnormal Blood-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Results. Gastroenterology. 2025 Jul 21:S0016-5085(25)05775-0. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.07.019. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40744392.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening significantly reduces CRC incidence and mortality, but only 65% of eligible individuals report being up-to-date with screening.1 Colonoscopy is the most widely used opportunistic screening method in the United States and is associated with many barriers to uptake. Providing patients a choice of colonoscopy and/or stool-based tests, improves screening adherence in randomized controlled trials.2,3 Non-invasive screening options have expanded from stool occult blood and multi-target DNA tests, to multi-target stool RNA tests, and novel blood-based tests, the latter only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for patients who refuse colonoscopy and stool-based tests.

Stool Occult Blood Tests

Guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT) significantly reduces CRC mortality by 33%-35% when implemented on an annual or biennial basis.4,5 Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) has supplanted gFOBT with advantages including independence from dietary restriction and medication-related interference, use of antibodies specific to human globin, and the need for only a single stool sample.

The most common threshold for a positive FIT in the U.S. is ≥ 20 micrograms (μg) of hemoglobin per gram (g) of stool. FIT is approved by the FDA as a qualitative positive or negative result based on a threshold value.6 A meta-analysis summarized test characteristics of commercially available FITs at various detection thresholds.7 The CRC sensitivity and specificity was 75% and 95% for ≥ 20 ug hemoglobin/g stool, and 91% and 90% for 10 ug hemoglobin/g stool, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas ranged from 25% at 20 μg/g to 40% at a 10 μg/g. Programmatic use of FIT in adults ages ≥ 50 years at 20 ug/g of stool, in cohort and case control studies, has been shown to significantly reduce CRC mortality by 33%-40% and advanced stage CRC by 34%.8,9

Over 57,000 average-risk individuals ages 50–69 years were randomized to biennial FIT or one-time colonoscopy and followed for 10 years.10 CRC mortality and incidence was similar between the groups: 0.22% with FIT vs. 0.24% with colonoscopy and 1.13% with FIT vs. 1.22% with colonoscopy, respectively. Thus, confirming biennial FIT screening is non-inferior to one-time colonoscopy in important CRC-related outcomes.

Multi-Target Stool Tests

Two multitarget stool DNA tests (mt-sDNA) known as Cologuard™ and Cologuard Plus™ have been approved by the FDA. Both tests include a FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin per gram of stool) combined with DNA methylation markers. The test result is qualitative, reported as a positive or negative. Cologuard™ markers include methylated BMP3, NDRG4, and mutant KRAS while Cologuard Plus™ assesses methylated LASS4, LRRC4, and PPP2R5C. The respective mt-sDNA tests were studied in 9989 of 12,776 and 20,176 of 26,758 average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy and the results were compared to a commercially available FIT (with a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool).11,12 In both trials, the sensitivity for CRC and advanced precancerous lesions was higher with the mt-sDNA tests compared to FIT but had a significantly lower specificity for advanced precancerous lesions versus FIT (see Table 1). An age-related decline in specificity was noted in both trials with mt-sDNA, a trend not observed with FIT. This reduction may be attributed to age-related DNA methylation.

Multi-Target Stool RNA Test

A multi-target stool RNA test (mt-sRNA) commercially available as ColoSense™ is FDA-approved. It combines FIT (at a positivity threshold of 20 μg hemoglobin/gram of stool) with RNA-based stool markers. The combined results of the RNA markers, FIT, and smoking status provide a qualitative single test result. In the trial, 8,920 adults aged ≥45 underwent the mt-sRNA test and FIT followed by colonoscopy (13). The mt-sRNA showed higher sensitivity for CRC than FIT (94.4% versus 77.8%) and advanced adenomas (45.9% versus 28.9%) but lower CRC specificity (84.7% vs 94.7%) (Table 1). Unlike mt-sDNA-based tests, mt-sRNA showed consistent performance across age groups, addressing concerns about age-related declines in specificity attributed to DNA methylation.

Blood-Based Tests

In 2014, the first blood-based (BBT) CRC screening test known as Epi proColon™ was FDA but not Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved for average-risk adults ≥50 years of age who are offered and refused other U.S Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) endorsed CRC screening tests. It is a qualitative test for detection of circulating methylated Septin 9 (mSeptin9). The accuracy of mSeptin9 to detect CRC was assessed in a subset of 7941 asymptomatic average risk adults undergoing screening colonoscopy.14 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC were 48% and 91.5%, respectively. The sensitivity for advanced adenomas was 11.2%. An increase in sensitivity to 63.9% and reduction in specificity to 88.4% for CRC was demonstrated in a sub-analysis of available samples where an additional (third) polymerase chain replicate was performed. Epi proColon™ is not currently reimbursed by Medicare and not endorsed in the latest USPSTF guidelines.

Technologic advancements have improved the detection of circulating tumor markers in the blood. The Shield™ BBT approved by the FDA in 2024 for average risk adults ≥ 45 years integrates three types of cfDNA data (epigenetic changes resulting in the aberrant methylation or fragmentation patterns, and genomic changes resulting in somatic mutations) into a positive or negative test result. In the trial, 22,877 average-risk, asymptomatic individuals ages 45–84 were enrolled and clinical validation was performed in 7,861 of the participants.15 The sensitivity for CRC was 83.1% which decreased to 55% for stage I tumors (see Table 1). CRC specificity was 89.6% and the sensitivity for advanced adenomas and large sessile serrated lesions was 13.2%.

Another BBT SimpleScreen™, which is not yet FDA-approved, analyzed circulating, cell-free DNA methylation patterns in 27,010 evaluable average-risk, asymptomatic adults ages 45–85 years undergoing screening colonoscopy.16 The sensitivity and specificity for CRC was 79.2% and 91.5%, respectively. Similar to Shield, the sensitivity for stage I CRC was low at 57.1%. The sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions, a secondary endpoint, was 12.5% which did not meet the prespecified study criteria.

Effectiveness and Cost Effectiveness

Modeling studies have evaluated novel noninvasive CRC screening tests compared to FIT and colonoscopy.17-20 One compared a hypothetical BBT performed every 3 years that meets the minimum CMS threshold CRC sensitivity and specificity of 74% and 90%, respectively, to other established CRC screening tests beginning at age 45.17 Every 3-year BBT reduced CRC incidence and mortality by 40% and 52%, respectively compared to no screening. However, the reductions were much lower than yearly FIT (72% and 76%, respectively), every 10 year colonoscopy (79% and 81%, respectively), and triennial mt-sDNA (68% and 73%, respectively). The BBT resulted in fewer quality-adjusted life-years per person compared to the alternatives.

Additionally, FIT, colonoscopy, and mt-sDNA were less costly and more effective. Advanced precancerous lesion detection was a key measure for a test’s effectiveness. BBT characteristics would require a CRC sensitivity and specificity of >90% and 90%, respectively, and 80% sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions at a cost of ≤$120–$140 to be cost-effective compared to FIT at comparable participation rates.

Another analysis simulated colorectal neoplasia progression and compared clinical effectiveness and cost between annual FIT, every 3 year stool mt-sRNA, every 3 year stool mt-sDNA tests, every 3 year stool Shield™; these outcomes were compared to colonoscopy every 10 years and no screening in adults ≥ age 45 over different adherence rates.19 At real-world adherence rates of 60%, colonoscopy prevented most CRC cases and associated deaths. FIT was the most cost-effective strategy at all adherence levels. Between the multi-target stool tests and Shield™, mt-sRNA was the most cost-effective. Compared to FIT, mt-sRNA reduced CRC cases and deaths by 1% and 14%.

The third study evaluated CRC incidence and mortality, quality-adjusted life-years and costs with annual FIT, colonoscopy every 10 years, mt- sDNA tests, mt-sRNA test, and BBTs.20 The latest mt-sDNA (Colguard plus™) and mt-sRNA achieved benefits approaching FIT but the Shield™ test was substantially less effective. The authors hypothesized that if 15% of the population substituted Shield™ for current effective CRC screening strategies, an increase in CRC deaths would occur and require 9-10% of the unscreened population to uptake screening with Shield to avert the increases in CRC deaths due to the substitution effect.

Clinical Implications

The effectiveness of non-invasive screening strategies depends on their diagnostic performance, adherence, and ensuring a timely colonoscopy after a positive test. Two claims-based studies found 47.9% and 49% of patients underwent follow-up colonoscopy within 6 months of an abnormal stool or BBT CRC screening test, respectively.21-22

Conclusions

Non-invasive stool mt-sDNA and mt-sRNA have higher effectiveness than the new BBTs. BBTs can lead to increased CRC mortality if substituted for the FDA and CMS-approved, USPSTF-endorsed, CRC screening modalities. If future BBTs increase their sensitivity for CRC (including early-stage CRC) and advanced precancerous lesions and decrease their cost, they may prove to have similar cost-effectiveness to stool-based tests. Currently, BBTs are not a substitute for colonoscopy or other stool tests and should be offered to patients who refuse other CRC screening modalities. A personalized, risk-adapted approach, paired with improved adherence and follow-up are essential to optimize the population-level impact of CRC screening and ensure equitable, effective cancer prevention.

Dr. Gupta is based at the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. Dr. Burke and Dr. Macaron are based at the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Macaron declared no conflicts of interest in regard to this article. Dr. Burke declared research support from Emtora Biosciences. She is a current consultant for Lumabridge, and has been a consultant for Sebela and Almirall. She also disclosed support from Myriad, Genzyme, Ferring, Merck, Sharp and Dohme, Abbvie, Salix, and Natera.

References

1. Benavidez GA, Sedani AE, Felder TM, Asare M, Rogers CR. Rural-urban disparities and trends in cancer screening: an analysis of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data (2018-2022). JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024 Nov 1;8(6):pkae113

2. Galoosian A, Dai H, Croymans D, et al. Population Health Colorectal Cancer Screening Strategies in Adults Aged 45 to 49 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025 Aug 4:e2512049. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.12049. Epub ahead of print.

3. Pilonis ND, Bugajski M, Wieszczy P, et al. Participation in Competing Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Randomized Health Services Study (PICCOLINO Study). Gastroenterology. 2021 Mar;160(4):1097-1105.

4. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106–1114.

5. Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996 Nov 30;348(9040):1467-71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. PMID: 8942774.

6. Burke CA, Lieberman D, Feuerstein JD. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Approach to the Use of Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening Options: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2022 Mar;162(3):952-956. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.075. Epub 2022 Jan 28. PMID: 35094786.

7. Imperiale TF, Gruber RN Stump TE, et al. Performance characteristics of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer and advanced adenomatous polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2019; 170(5):319-329

8. Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Jensen CD, et al. Fecal Immunochemical Test Screening and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Death. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jul 1;7(7):e2423671. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.23671.

9. Chiu HM, Jen GH, Wang YW, et al. Long-term effectiveness of faecal immunochemical test screening for proximal and distal colorectal cancers. Gut. 2021 Dec;70(12):2321-2329. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322545. Epub 2021 Jan 25.

10. Castells A, Quintero E, Bujanda L, et al; COLONPREV study investigators. Effect of invitation to colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test screening on colorectal cancer mortality (COLONPREV): a pragmatic, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2025;405(10486):1231–1239

11. Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287-1297

12. Imperiale TF, Porter K, Zella J, et al. Next-Generation Multitarget Stool DNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):984-993

13. Barnell EK, Wurtzler EM, La Rocca J, et al. Multitarget Stool RNA Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. JAMA. 2023 Nov 14;330(18):1760-1768.

14. Church TR, Wandell M, Lofton-Day C, et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut 2014; 63:317–325.

15. Chung DC, Gray DM 2nd, Singh H, et al. A Cell-free DNA Blood-Based Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2024 Mar 14;390(11):973-983.

16. Shaukat A, Burke CA, Chan AT, et al. Clinical Validation of a Circulating Tumor DNA-Based Blood Test to Screen for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA. 2025 Jul 1;334(1):56-63.

17. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Weng Y, et al. Comparative Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer Screening with Blood-Based Biomarkers (Liquid Biopsy) vs Fecal Tests or Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2024 Jul;167(2):378-391.

18. van den Puttelaar R, Nascimento de Lima P, Knudsen AB, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with a blood test that meets the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services coverage decision. Gastroenterology 2024;167:368–377.

19. Shaukat A, Levin TR, Liang PS. Cost-effectiveness of Novel Noninvasive Screening Tests for Colorectal Neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Jun 23:S1542-3565(25)00525-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2025.06.006. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40562290.

20. Ladabaum U, Mannalithara A, Schoen RE, Dominitz JA, Lieberman D. Projected Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Novel Molecular Blood-Based or Stool-Based Screening Tests for Colorectal Cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Dec;177(12):1610-1620.

20. Ciemins EL, Mohl JT, Moreno CA, Colangelo F, Smith RA, Barton M. Development of a Follow-Up Measure to Ensure Complete Screening for Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e242693. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2693.

21. Zaki TA, Zhang NJ, Forbes SP, Raymond VM, Das AK, May FP. Colonoscopic Follow-up After Abnormal Blood-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Results. Gastroenterology. 2025 Jul 21:S0016-5085(25)05775-0. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.07.019. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40744392.

‘So You Have an Idea…’: A Practical Guide to Tech and Device Development for the Early Career GI

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners

You do not need a full legal team, but you do need a lawyer early. An early consultation with an IP attorney can clarify your rights, guide your filing process (e.g. provisional patents), and help you avoid costly missteps.

Do this before sharing your idea publicly, including in academic presentations, pitch competitions, or even on social media. Public disclosure can start a clock ticking for application to protect your IP.

3. Build a Founding Team with Intent

Think of your startup team like a long-term relationship: you’re committing to build something together through uncertainty, tension, and change.

Strong early-stage teams often include:

- The Visionary – understands the clinical need and vision

- The Builder – engineer, developer, or designer

- The Doer – project manager or operations lead

Before forming a company, clearly define:

- Ownership (equity percentages)

- Roles and responsibilities

- Time commitments

- What happens if someone exits

Have these discussions early and document your agreements. Avoid informal “handshake” deals that can lead to serious disputes later.

4. You Don’t Need to Know Everything on Day One

You do not need to know how to write code, build a prototype, or get FDA clearance on day one. Successful innovators are humble learners. Use a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a simple, functional version of your idea, to test assumptions and gather feedback. Iterate based on what you learn. Do not chase perfection; pursue progress. Consider using online accelerators like Y Combinator’s startup school or AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

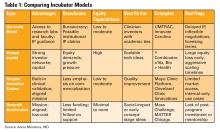

5. Incubators: Use them Strategically

Incubators can offer mentorship, seed funding, legal support, and technical resources, but they vary widely in value (see Table 1). Many may want equity, and not all offer when you truly need.

Ask Yourself:

- Do I need technical help, business mentorship, or just accountability?

- What does this incubator offer in terms of IP protection, exposure, and connections?

- Do I understand the equity trade-off?

- What services and funding do they provide?

- Do they take equity? How much and when?

- What’s their track record with similar ventures?

- Are their incentives aligned with your vision?

6. Academic Institutions: Partners or Pitfalls?

Universities can provide credibility, resources, and early funding through their tech transfer office (TTO).

Key Questions to Ask:

- Will my IP be managed by the TTO?

- How much say do I have in licensing decisions?

- Are there royalty-sharing agreements in place?

- Can I form a startup while employed here?

You may need to negotiate if you want to commercialize your idea independently.

7. Do it for Purpose, Not Payday

Most founders end up owning only a small percentage of their company by the time a product reaches the market. Do not expect to get rich. Do it because it solves a problem you care about. If it happens to come with a nice paycheck, then that is an added bonus.

Your clinical training and insight give you a unique edge. You already know what’s broken. Use that as your compass.

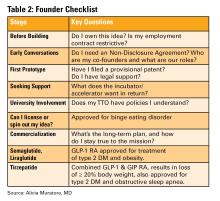

Conclusion

Innovation isn’t about brilliance, it’s about curiosity, structure, and tenacity (see Table 2). Start small. Protect your work. Choose the right partners. Most importantly, stay anchored in your mission to make GI care better.

Dr. Muratore is based at UNC Rex Digestive Health, Raleigh, North Carolina. She has no conflicts related to this article. Dr. Wechsler is based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She holds a patent assigned to Trustees of Dartmouth College. Dr. Shah is based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. He consults for Ardelyx, Laborie, Neuraxis, Salix, Sanofi, and Takeda and holds a patent with the Regents of the University of Michigan.

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners