User login

Genomic Testing in Women with Early-Stage Hormone Receptor–Positive, HER2-Negative Breast Cancer

Introduction

Over the past several decades, while the incidence of breast cancer has increased, breast cancer mortality has decreased. This decrease is likely due to both early detection and advances in systemic therapy. However, with more widespread use of screening mammography, there are increasing concerns about potential overdiagnosis of cancer.1 One key challenge is that breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease. Improved tools for determining breast cancer biology can help physicians individualize treatments. Patients with low-risk cancers can be approached with less aggressive treatments, thus preventing unnecessary toxicities, while those with higher-risk cancers remain treated appropriately with more aggressive therapies.

Traditionally, adjuvant chemotherapy was recommended based on tumor features such as stage (tumor size, regional nodal involvement), grade, expression of hormone receptors (estrogen receptor [ER] and progesterone receptor [PR]) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2), and patient features (age, menopausal status). However, this approach is not accurate enough to guide individualized treatment approaches, which are based on the risk for recurrence and the reduction in this risk that can be achieved with various systemic treatments. In particular, women with low-risk hormone receptor (HR)–positive, HER2-negative breast cancers could be spared the toxicities of cytotoxic chemotherapies without compromising the prognosis.

Beyond chemotherapy, endocrine therapies also have risks, especially when given over extended periods of time. Recently, extended endocrine therapy has been shown to prevent late recurrences of HR-positive breast cancers. In the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group’s MA.17R study, extended endocrine therapy with letrozole for a total of 10 years (beyond 5 years of an aromatase inhibitor [AI]) decreased the risk for breast cancer recurrence or the occurrence of contralateral breast cancer by 34%.2 However, the overall survival was similar between the 2 groups and the disease-free survival benefits were not confirmed in other studies.3–5 Identifying the subgroup of patients who benefit from this extended AI therapy is important in the era of personalized medicine. Several tumor genomic assays have been developed to provide additional prognostic and predictive information with the goal of individualizing adjuvant therapies for breast cancer. Although assays are also being evaluated in HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer, this review will focus on HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer.

Tests for Guiding Adjuvant Chemotherapy Decisions

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 54-year-old postmenopausal woman with no significant past medical history presents with an abnormal screening mammogram, which shows a focal asymmetry in the 10 o’clock position at middle depth of the left breast. Further work-up with a diagnostic mammogram and ultrasound of the left breast shows a suspicious hypoechoic solid mass with irregular margins measuring 17 mm. The patient undergoes an ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the suspicious mass, the results of which are consistent with an invasive ductal carcinoma, Nottingham grade 2, ER strongly positive (95%), PR weakly positive (5%), HER2-negative, and Ki-67 of 15%. She undergoes a left partial mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy, with final pathology demonstrating a single focus of invasive ductal carcinoma, measuring 2.2 cm in greatest dimension with no evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Margins are clear and 2 sentinel lymph nodes are negative for metastatic disease (final pathologic stage IIA, pT2 pN0 cM0). She is referred to medical oncology to discuss adjuvant systemic therapy.

- Can additional testing be used to determine prognosis and guide systemic therapy recommendations for early-stage HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer?

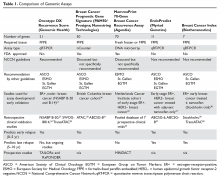

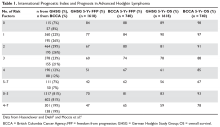

After a diagnosis of early-stage breast cancer, the key clinical question faced by the patient and medical oncologist is: what is the individual’s risk for a metastatic breast cancer recurrence and thus the risk for death due to breast cancer? Once the risk for recurrence is established, systemic adjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and/or HER2-directed therapy are considered based on the receptor status (ER/PR and HER2) to reduce this risk. HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer is the most common type of breast cancer. Although adjuvant endocrine therapy has significantly reduced the risk for recurrence and improved survival for patients with HR-positive breast cancer,6 the role of adjuvant chemotherapy for this subset of breast cancer remains unclear. Prior to genomic testing, the recommendation for adjuvant chemotherapy for HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors was primarily based on patient age and tumor stage and grade. However, chemotherapy overtreatment remained a concern given the potential short- and long-term risks of chemotherapy. Further studies into HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors have shown that these tumors can be divided into 2 main subtypes, luminal A and luminal B.7 These subtypes represent unique biology and differ in terms of prognosis and response to endocrine therapy and chemotherapy. Luminal A tumors are strongly endocrine responsive and have a good prognosis, while luminal B tumors are less endocrine responsive and are associated with a poorer prognosis; the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy is often considered for luminal B tumors.8 Several tests, including tumor genomic assays, are now available to help with delineating the tumor subtype and aid in decision-making regarding adjuvant chemotherapy for HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancers.

Ki-67 Assays, Including IHC4 and PEPI

Proliferation is a hallmark of cancer cells.9 Ki-67, a nuclear nonhistone protein whose expression varies in intensity throughout the cell cycle, has been used as a measurement of tumor cell proliferation.10 Two large meta-analyses have demonstrated that high Ki-67 expression in breast tumors is independently associated with worse disease-free and overall survival rates.11,12 Ki-67 expression has also been used to classify HR-positive tumors as luminal A or B. After classifying tumor subtypes based on intrinsic gene expression profiling, Cheang and colleagues determined that a Ki-67 cut point of 13.25% differentiated luminal A and B tumors.13 However, the ideal cut point for Ki-67 remains unclear, as the sensitivity and specificity in this study was 77% and 78%, respectively. Others have combined Ki-67 with standard ER, PR, and HER2 testing. This immunohistochemical 4 (IHC4) score, which weighs each of these variables, was validated in postmenopausal patients from the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial who had ER-positive tumors and did not receive chemotherapy.14 The prognostic information from the IHC4 was similar to that seen with the 21-gene recurrence score (Oncotype DX), which is discussed later in this article. The key challenge with Ki-67 testing currently is the lack of a validated test methodology and intra-observer variability in interpreting the Ki-67 results.15 Recent series have suggested that Ki-67 be considered as a continuous marker rather than a set cut point.16 These issues continue to impact the clinical utility of Ki-67 for decision-making for adjuvant chemotherapy.

Ki-67 and the preoperative endocrine prognostic index (PEPI) score have been explored in the neoadjuvant setting to separate postmenopausal women with endocrine-sensitive versus intrinsically resistant disease and identify patients at risk for recurrent disease.17 The on-treatment levels of Ki-67 in response to endocrine therapy have been shown to be more prognostic than baseline values, and a decrease in Ki-67 as early as 2 weeks after initiation of neoadjuvant endocrine therapy is associated with endocrine-sensitive tumors and improved outcome. The PEPI score was developed through retrospective analysis of the P024 trial18 to evaluate the relationship between post-neoadjuvant endocrine therapy tumor characteristics and risk for early relapse. The score was subsequently validated in an independent data set from the IMPACT (Immediate Preoperative Anastrozole, Tamoxifen, or Combined with Tamoxifen) trial.19 Patients with low pathological stage (0 or 1) and a favorable biomarker profile (PEPI score 0) at surgery had the best prognosis in the absence of chemotherapy. On the other hand, higher pathological stage at surgery and a poor biomarker profile with loss of ER positivity or persistently elevated Ki-67 (PEPI score of 3) identified de novo endocrine-resistant tumors that are higher risk for early relapse.20 The ongoing Alliance A011106 ALTERNATE trial (ALTernate approaches for clinical stage II or III Estrogen Receptor positive breast cancer NeoAdjuvant TrEatment in postmenopausal women, NCT01953588) is a phase 3 study to prospectively test this hypothesis.

21-Gene Recurrence Score (Onco type DX Assay)

The 21-gene Oncotype DX assay is conducted on paraffin-embedded tumor tissue and measures the expression of 16 cancer related genes and 5 reference genes using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The genes included in this assay are mainly related to proliferation (including Ki-67), invasion, and HER2 or estrogen signaling.21 Originally, the 21-gene recurrence score assay was analyzed as a prognostic biomarker tool in a prospective-retrospective biomarker substudy of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-14 clinical trial in which patients with node-negative, ER-positive tumors were randomly assigned to receive tamoxifen or placebo without chemotherapy.22 Using the standard reported values of low risk (< 18), intermediate risk (18–30), or high risk (≥ 31) for recurrence, among the tamoxifen-treated patients, cancers with a high-risk recurrence score had a significantly worse rate of distant recurrence and overall survival.21 Inferior breast cancer survival in cancers with a high recurrence score was also confirmed in other series of endocrine-treated patients with node-negative and node-positive disease.23–25

The predictive utility of the 21-gene recurrence score for endocrine therapy has also been evaluated. A comparison of the placebo- and tamoxifen-treated patients from the NSABP B-14 trial demonstrated that the 21-gene recurrence score predicted benefit from tamoxifen in cancers with low- or intermediate-risk recurrence scores.26 However, there was no benefit from the use of tamoxifen over placebo in cancers with high-risk recurrence scores. To date, this intriguing data has not been prospectively confirmed, and thus the 21-gene recurrence score is not used to avoid endocrine therapy.

The 21-gene recurrence score is primarily used by oncologists to aid in decision-making regarding adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-negative and node-positive (with up to 3 positive lymph nodes), HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancers. The predictive utility of the 21-gene recurrence score for adjuvant chemotherapy was initially tested using tumor samples from the NSABP B-20 study. This study initially compared adjuvant tamoxifen alone with tamoxifen plus chemotherapy in patients with node-negative, HR-positive tumors. The prospective-retrospective biomarker analysis showed that the patients with high-risk 21-gene recurrence scores benefited from the addition of chemotherapy, whereas those with low or intermediate risk did not have an improved freedom from distant recurrence with chemotherapy.27 Similarly, an analysis from the prospective phase 3 Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) 8814 trial comparing tamoxifen to tamoxifen with chemotherapy showed that for node-positive tumors, chemotherapy benefit was only seen in those with high 21-gene recurrence scores.24

Prospective studies are now starting to report results regarding the predictive role of the 21-gene recurrence score. The TAILORx (Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment) trial includes women with node-negative, HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors measuring 0.6 to 5 cm. All patients were treated with standard-of-care endocrine therapy for at least 5 years. Chemotherapy was determined based on the 21-gene recurrence score results on the primary tumor. The 21-gene recurrence score cutoffs were changed to low (0–10), intermediate (11–25), and high (≥ 26). Patients with scores of 26 or higher were treated with chemotherapy, and those with intermediate scores were randomly assigned to chemotherapy or no chemotherapy; results from this cohort are still pending. However, excellent breast cancer outcomes with endocrine therapy alone were reported from the 1626 (15.9% of total cohort) prospectively followed patients with low recurrence score tumors. The 5-year invasive disease-free survival was 93.8%, with overall survival of 98%.28 Given that 5 years is appropriate follow-up to see any chemotherapy benefit, this data supports the recommendation for no chemotherapy in this cohort of patients with very low 21-gene recurrence scores.

The RxPONDER (Rx for Positive Node, Endocrine Responsive Breast Cancer) trial is evaluating women with 1 to 3 node-positive, HR-positive, HER2-negative tumors. In this trial, patients with 21-gene recurrence scores of 0 to 25 were assigned to adjuvant chemotherapy or none. Those with scores of 26 or higher were assigned to chemotherapy. All patients received standard adjuvant endocrine therapy. This study has completed accrual and results are pending. Of note, TAILORx and RxPONDER did not investigate the potential lack of benefit of endocrine therapy in cancers with high recurrence scores. Furthermore, despite data suggesting that chemotherapy may not even benefit women with 4 or more nodes involved but who have a low recurrence score,24 due to the lack of prospective data in this cohort and the quite high risk for distant recurrence, chemotherapy continues to be the standard of care for these patients.

PAM50 (Breast Cancer Prognostic Gene Signature)

Using microarray and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, the Breast Cancer Prognostic Gene Signature (PAM50) assay was initially developed to identify intrinsic breast cancer subtypes, including luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, and basal-like.7,29 Based on the prediction analysis of microarray (PAM) method, the assay measures the expression levels of 50 genes, provides a risk category (low, intermediate, and high), and generates a numerical risk of recurrence score (ROR). The intrinsic subtype and ROR have been shown to add significant prognostic value to the clinicopathological characteristics of tumors. Clinical validity of PAM50 was evaluated in postmenopausal women with HR-positive early-stage breast cancer treated in the prospective ATAC and ABCSG-8 (Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group 8) trials.30,31 In 1017 patients with ER-positive breast cancer treated with anastrozole or tamoxifen in the ATAC trial, ROR added significant prognostic information beyond the clinical treatment score (integrated prognostic information from nodal status, tumor size, histopathologic grade, age, and anastrozole or tamoxifen treatment) in all patients. Also, compared with the 21-gene recurrence score, ROR provided more prognostic information in ER-positive, node-negative disease and better differentiation of intermediate- and higher-risk groups. Fewer patients were categorized as intermediate risk by ROR and more as high risk, which could reduce the uncertainty in the estimate of clinical benefit from chemotherapy.30 The clinical utility of PAM50 as a prognostic model was also validated in 1478 postmenopausal women with ER-positive early-stage breast cancer enrolled in the ABCSG-8 trial. In this study, ROR assigned 47% of patients with node-negative disease to the low-risk category. In this low-risk group, the 10-year metastasis risk was less than 3.5%, indicating lack of benefit from additional chemotherapy.31 A key limitation of the PAM50 is the lack of any prospective studies with this assay.

PAM50 has been designed to be carried out in any qualified pathology laboratory. Moreover, the ROR score provides additional prognostic information about risk of late recurrence, which will be discussed in the next section.

70-Gene Breast Cancer Recurrence Assay (MammaPrint)

MammaPrint is a 70-gene assay that was initially developed using an unsupervised, hierarchical clustering algorithm on whole-genome expression arrays with early-stage breast cancer. Among 295 consecutive patients who had MammaPrint testing, those classified with a good-prognosis tumor signature (n = 115) had an excellent 10-year survival rate (94.5%) compared to those with a poor-prognosis signature (54.5%), and the signature remained prognostic upon multivariate analysis.32 Subsequently, a pooled analysis comparing outcomes by MammaPrint score in patients with node-negative or 1 to 3 node-positive breast cancers treated as per discretion of their medical team with either adjuvant chemotherapy plus endocrine therapy or endocrine therapy alone reported that only those patients with a high-risk score benefited from chemotherapy.33 Recently, a prospective phase 3 study (MINDACT [Microarray In Node negative Disease may Avoid ChemoTherapy]) evaluating the utility of MammaPrint for adjuvant chemotherapy decision-making reported results.34 In this study, 6693 women with early-stage breast cancer were assessed by clinical risk and genomic risk using MammaPrint. Those with low clinical and genomic risk did not receive chemotherapy, while those with high clinical and genomic risk all received chemotherapy. The primary goal of the study was to assess whether forgoing chemotherapy would be associated with a low rate of recurrence in those patients with a low-risk prognostic MammaPrint signature but high clinical risk. A total of 1550 patients (23.2%) were in the discordant group, and the majority of these patients had HR-positive disease (98.1%). Without chemotherapy, the rate of survival without distant metastasis at 5 years in this group was 94.7% (95% confidence interval [CI] 92.5% to 96.2%), which met the primary endpoint. Of note, initially, MammaPrint was only available for fresh tissue analysis, but recent advances in RNA processing now allow for this analysis on FFPE tissue.35

Summary

These genomic and biomarker assays can identify different subsets of HR-positive breast cancers, including those patients who have tumors with an excellent prognosis with endocrine therapies alone. Thus, we now have the tools to help avoid the toxicities of chemotherapy in many women with early-stage breast cancer.

Tests for Assessing Risk for Late Recurrence

Case Continued

The patient undergoes 21-gene recurrence score testing, which shows a low recurrence score of 10, estimating the 10-year risk of distant recurrence to be approximately 7% with 5 years of tamoxifen. Chemotherapy is not recommended. The patient completes adjuvant whole breast radiation therapy, and then, based on data supporting AIs over tamoxifen in postmenopausal women, she is started on anastrozole.41 She initially experiences mild side effects from treatment, including fatigue, arthralgia, and vaginal dryness, but her symptoms are able to be managed. As she approaches 5 years of adjuvant endocrine therapy with anastrozole, she is struggling with rotator cuff injury and is anxious about recurrence, but has no evidence of recurrent cancer. Her bone density scan in the beginning of her fourth year of therapy shows a decrease in bone mineral density, with the lowest T score of –1.5 at the left femoral neck, consistent with osteopenia. She has been treated with calcium and vitamin D supplements.

- How long should this patient continue treatment with anastrozole?

The risk for recurrence is highest during the first 5 years after diagnosis for all patients with early breast cancer.42 Although HR-positive breast cancers have a better prognosis than HR-negative disease, the pattern of recurrence is different between the 2 groups, and it is estimated that approximately half of the recurrences among patients with HR-positive early breast cancer occur after the first 5 years from diagnosis. Annualized hazard of recurrence in HR-positive breast cancer has been shown to remain elevated and fairly stable beyond 10 years, even for those with low tumor burden and node-negative disease.43 Prospective trials showed that for women with HR-positive early breast cancer, 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen could substantially reduce recurrence rates and improve survival, and this became the standard of care.44 AIs are considered the standard of care for adjuvant endocrine therapy in most postmenopausal women, as they result in a significantly lower recurrence rate compared with tamoxifen, either as initial adjuvant therapy or sequentially following 2 to 3 years of tamoxifen.45

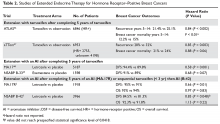

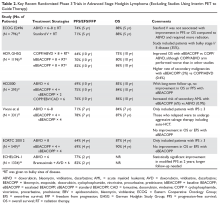

Due to the risk for later recurrences with HR-positive breast cancer, more patients and oncologists are considering extended endocrine therapy. This is based on results from the ATLAS (Adjuvant Tamoxifen: Longer Against Shorter) and aTTOM (Adjuvant Tamoxifen–To Offer More?) studies, both of which showed that women with HR-positive breast cancer who continued tamoxifen for 10 years had a lower late recurrence rate and a lower breast cancer mortality rate compared with those who stopped at 5 years.46,47 Furthermore, the NCIC MA.17 trial evaluated extended endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with 5 years of letrozole following 5 years of tamoxifen. Letrozole was shown to improve both disease-free and distant disease-free survival. The overall survival benefit was limited to patients with node-positive disease.48 A summary of studies of extended endocrine therapy for HR-positive breast cancers is shown in Table 2.2,3,46–49

However, extending AI therapy from 5 years to 10 years is not clearly beneficial. In the MA.17R trial, although longer AI therapy resulted in significantly better disease-free survival (95% versus 91%, hazard ratio 0.66, P = 0.01), this was primarily due to a lower incidence of contralateral breast cancer in those taking the AI compared with placebo. The distant recurrence risks were similar and low (4.4% versus 5.5%), and there was no overall survival difference.2 Also, the NSABP B-42 study, which was presented at the 2016 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, did not meet its predefined endpoint for benefit from extending adjuvant AI therapy with letrozole beyond 5 years.3 Thus, the absolute benefit from extended endocrine therapy has been modest across these studies. Although endocrine therapy is considered relatively safe and well tolerated, side effects can be significant and even associated with morbidity. Ideally, extended endocrine therapy should be offered to the subset of patients who would benefit the most. Several genomic diagnostic assays, including the EndoPredict test, PAM50, and the Breast Cancer Index (BCI) tests, specifically assess the risk for late recurrence in HR-positive cancers.

PAM50

Studies suggest that the ROR score also has value in predicting late recurrences. Analysis of data in patients enrolled in the ABCSG-8 trial showed that ROR could identify patients with endocrine-sensitive disease who are at low risk for late relapse and could be spared from unwanted toxicities of extended endocrine therapies. In 1246 ABCSG-8 patients between years 5 and 15, the PAM50 ROR demonstrated an absolute risk of distant recurrence of 2.4% in the low-risk group, as compared with 17.5% in the high-risk group.50 Also, a combined analysis of patients from both the ATAC and ABCSG-8 trials demonstrated the utility of ROR in identifying this subgroup of patients with low risk for late relapse.51

EndoPredict

EndoPredict is another quantitative RT-PCR–based assay which uses FFPE tissues to calculate a risk score based on 8 cancer-related and 3 reference genes. The score is combined with clinicopathological factors including tumor size and nodal status to make a comprehensive risk score (EPclin). EPclin is used to dichotomize patients into EndoPredict low- and high-risk groups. EndoPredict has been validated in 2 cohorts of patients enrolled in separate randomized studies, ABCSG-6 and ABCSG-8. EP provided prognostic information beyond clinicopathological variables to predict distant recurrence in patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative early breast cancer.37 More important, EndoPredict has been shown to predict early (years 0–5) versus late (> 5 years after diagnosis) recurrences and identify a low-risk subset of patients who would not be expected to benefit from further treatment beyond 5 years of endocrine therapy.52 Recently, EndoPredict and EPclin were compared with the 21-gene (Oncotype DX) recurrence score in a patient population from the TransATAC study. Both EndoPredict and EPclin provided more prognostic information compared to the 21-gene recurrence score and identified early and late relapse events.53 EndoPredict is the first multigene expression assay that could be routinely performed in decentralized molecular pathological laboratories with a short turnaround time.54

Breast Cancer Index

The BCI is a RT-PCR–based gene expression assay that consists of 2 gene expression biomarkers: molecular grade index (MGI) and HOXB13/IL17BR (H/I). The BCI was developed as a prognostic test to assess risk for breast cancer recurrence using a cohort of ER-positive patients (n = 588) treated with adjuvant tamoxifen versus observation from the prospective randomized Stockholm trial.38 In this blinded retrospective study, H/I and MGI were measured and a continuous risk model (BCI) was developed in the tamoxifen-treated group. More than 50% of the patients in this group were classified as having a low risk of recurrence. The rate of distant recurrence or death in this low-risk group at 10 years was less than 3%. The performance of the BCI model was then tested in the untreated arm of the Stockholm trial. In the untreated arm, BCI classified 53%, 27%, and 20% of patients as low, intermediate, and high risk, respectively. The rate of distant metastasis at 10 years in these risk groups was 8.3% (95% CI 4.7% to 14.4%), 22.9% (95% CI 14.5% to 35.2%), and 28.5% (95% CI 17.9% to 43.6%), respectively, and the rate of breast cancer–specific mortality was 5.1% (95% CI 1.3% to 8.7%), 19.8% (95% CI 10.0% to 28.6%), and 28.8% (95% CI 15.3% to 40.2%).38

The prognostic and predictive values of the BCI have been validated in other large, randomized studies and in patients with both node-negative and node-positive disease.39,55 The predictive value of the endocrine-response biomarker, the H/I ratio, has been demonstrated in randomized studies. In the MA.17 trial, a high H/I ratio was associated with increased risk for late recurrence in the absence of letrozole. However, extended endocrine therapy with letrozole in patients with high H/I ratios predicted benefit from therapy and decreased the probability of late disease recurrence.56 BCI was also compared to IHC4 and the 21-gene recurrence score in the TransATAC study and was the only test to show prognostic significance for both early (0–5 years) and late (5–10 year) recurrence.40

The impact of the BCI results on physicians’ recommendations for extended endocrine therapy was assessed by a prospective study. This study showed that the test result had a significant effect on both physician treatment recommendation and patient satisfaction. BCI testing resulted in a change in physician recommendations for extended endocrine therapy, with an overall decrease in recommendations for extended endocrine therapy from 74% to 54%. Knowledge of the test result also led to improved patient satisfaction and decreased anxiety.57

Summary

Due to the risk for late recurrence, extended endocrine therapy is being recommended for many patients with HR-positive breast cancers. Multiple genomic assays are being developed to better understand an individual’s risk for late recurrence and the potential for benefit from extended endocrine therapies. However, none of the assays has been validated in prospective randomized studies. Further validation is needed prior to routine use of these assays.

Case Continued

A BCI test is done and the result shows 4.3% BCI low-risk category in years 5–10, which is consistent with a low likelihood of benefit from extended endocrine therapy. After discussing the results of the BCI test in the context of no survival benefit from extending AIs beyond 5 years, both the patient and her oncologist feel comfortable with discontinuing endocrine therapy at the end of 5 years.

Conclusion

Reduction in breast cancer mortality is mainly the result of improved systemic treatments. With advances in breast cancer screening tools in recent years, the rate of cancer detection has increased. This has raised concerns regarding overdiagnosis. To prevent unwanted toxicities associated with overtreatment, better treatment decision tools are needed. Several genomic assays are currently available and widely used to provide prognostic and predictive information and aid in decisions regarding appropriate use of adjuvant chemotherapy in HR-positive/HER2-negative early-stage breast cancer. Ongoing studies are refining the cutoffs for these assays and expanding the applicability to node-positive breast cancers. Furthermore, with several studies now showing benefit from the use of extended endocrine therapy, some of these assays may be able to identify the subset of patients who are at increased risk for late recurrence and who might benefit from extended endocrine therapy. Advances in molecular testing has enabled clinicians to offer more personalized treatments to their patients, improve patients’ compliance, and decrease anxiety and conflict associated with management decisions. Although small numbers of patients with HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancers were also included in some of these studies, use of genomic assays in this subset of patients is very limited and currently not recommended.

1. Welch HG, Prorok PC, O’Malley AJ, Kramer BS. Breast-cancer tumor size, overdiagnosis, and mammography screening effectiveness. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1438–47.

2. Goss PE, Ingle JN, Pritchard KI, et al. Extending aromatase-inhibitor adjuvant therapy to 10 years. N Engl J Med 2016;375:209–19.

3. Mamounas E, Bandos H, Lembersky B. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy with letrozole in postmenopausal women with hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer who have completed previous adjuvant treatment with an aromatase inhibitor. In: Proceedings from the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 6–10, 2016; San Antonio, TX. Abstract S1-05.

4. Tjan-Heijnen VC, Van Hellemond IE, Peer PG, et al: First results from the multicenter phase III DATA study comparing 3 versus 6 years of anastrozole after 2-3 years of tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive early breast cancer. In: Proceedings from the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 6–10, 2016; San Antonio, TX. Abstract S1-03.

5. Blok EJ, Van de Velde CJH, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg EM, et al: Optimal duration of extended letrozole treatment after 5 years of adjuvant endocrine therapy. In: Proceedings from the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 6–10, 2016; San Antonio, TX. Abstract S1-04.

6. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Lancet 2005;365:1687–717.

7. Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2000;406:747–52.

8. Coates AS, Winer EP, Goldhirsch A, et al. Tailoring therapies--improving the management of early breast cancer: St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2015. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1533–46.

9. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000;100:57–70.

10. Urruticoechea A, Smith IE, Dowsett M. Proliferation marker Ki-67 in early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7212–20.

11. de Azambuja E, Cardoso F, de Castro G Jr, et al. Ki-67 as prognostic marker in early breast cancer: a meta-analysis of published studies involving 12,155 patients. Br J Cancer 2007;96:1504–13.

12. Petrelli F, Viale G, Cabiddu M, Barni S. Prognostic value of different cut-off levels of Ki-67 in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64,196 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;153:477–91.

13. Cheang MC, Chia SK, Voduc D, et al. Ki67 index, HER2 status, and prognosis of patients with luminal B breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:736–50.

14. Cuzick J, Dowsett M, Pineda S, et al. Prognostic value of a combined estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, Ki-67, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 immunohistochemical score and com-parison with the Genomic Health recurrence score in early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4273–8.

15. Pathmanathan N, Balleine RL. Ki67 and proliferation in breast cancer. J Clin Pathol 2013;66:512–6.

16. Denkert C, Budczies J, von Minckwitz G, et al. Strategies for developing Ki67 as a useful biomarker in breast cancer. Breast 2015; 24 Suppl 2:S67–72.

17. Ma CX, Bose R, Ellis MJ. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers of endocrine responsiveness for estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016;882:125–54.

18. Eiermann W, Paepke S, Appfelstaedt J, et al. Preoperative treatment of postmenopausal breast cancer patients with letrozole: a randomized double-blind multicenter study. Ann Oncol 2001;12:1527–32.

19. Smith IE, Dowsett M, Ebbs SR, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment of postmenopausal breast cancer with anastrozole, tamoxifen, or both in combination: the Immediate Preoperative Anas-trozole, Tamoxifen, or Combined with Tamoxifen (IMPACT) multicenter double-blind randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5108–16.

20. Ellis MJ, Tao Y, Luo J, et al. Outcome prediction for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer based on postneoadjuvant endocrine therapy tumor characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1380–8.

21. Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2817–26.

22. Fisher B, Jeong JH, Bryant J, et al. Treatment of lymph-node-negative, oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer: long-term findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2004;364:858–68.

23. Habel LA, Shak S, Jacobs MK, et al. A population-based study of tumor gene expression and risk of breast cancer death among lymph node-negative patients. Breast Cancer Res 2006;8:R25.

24. Albain KS, Barlow WE, Shak S, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of the 21-gene recurrence score assay in postmenopausal women with node-positive, oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer on chemotherapy: a retrospective analysis of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:55–65.

25. Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Wale C, et al. Prediction of risk of distant recurrence using the 21-gene recurrence score in node-negative and node-positive postmenopausal patients with breast cancer treated with anastrozole or tamoxifen: a TransATAC study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1829–34.

26. Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, et al. Expression of the 21 genes in the recurrence score assay and tamoxifen clinical benefit in the NSABP study B-14 of node negative, estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23: suppl:510.

27. Paik S, Tang G, Shak S, et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3726–34.

28. Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Prospective validation of a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2005–14.

29. Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MC, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1160–7.

30. Dowsett M, Sestak I, Lopez-Knowles E, et al. Comparison of PAM50 risk of recurrence score with oncotype DX and IHC4 for predicting risk of distant recurrence after endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2783–90.

31. Gnant M, Filipits M, Greil R, et al. Predicting distant recurrence in receptor-positive breast cancer patients with limited clinicopathological risk: using the PAM50 Risk of Recurrence score in 1478 post-menopausal patients of the ABCSG-8 trial treated with adjuvant endocrine therapy alone. Ann Oncol 2014;25:339–45.

32. van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van’t Veer LJ, et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1999–2009.

33. Knauer M, Mook S, Rutgers EJ, et al. The predictive value of the 70-gene signature for adjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010;120:655–61.

34. Cardoso F, van’t Veer LJ, Bogaerts J, et al. 70-gene signature as an aid to treatment decisions in early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:717–29.

35. Sapino A, Roepman P, Linn SC, et al. MammaPrint molecular diagnostics on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. J Mol Diagn 2014;16:190–7.

36. Nielsen TO, Parker JS, Leung S, et al. A comparison of PAM50 intrinsic subtyping with immunohistochemistry and clinical prognostic factors in tamoxifen-treated estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:5222–32.

37. Filipits M, Rudas M, Jakesz R, et al. A new molecular predictor of distant recurrence in ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer adds independent information to conventional clinical risk factors. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:6012–20.

38. Jerevall PL, Ma XJ, Li H, et al. Prognostic utility of HOXB13:IL17BR and molecular grade index in early-stage breast cancer patients from the Stockholm trial. Br J Cancer 2011;104:1762–9.

39. Zhang Y, Schnabel CA, Schroeder BE, et al. Breast cancer index identifies early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients at risk for early- and late-distant recurrence. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:4196–205.

40. Sgroi DC, Sestak I, Cuzick J, et al. Prediction of late distant recurrence in patients with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer: a prospective comparison of the breast-cancer index (BCI) assay, 21-gene recurrence score, and IHC4 in the TransATAC study population. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1067–76.

41. Burstein HJ, Griggs JJ, Prestrud AA, Temin S. American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline update on adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Oncol Pract 2010;6:243–6.

42. Saphner T, Tormey DC, Gray R. Annual hazard rates of recurrence for breast cancer after primary therapy. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:2738–46.

43. Colleoni M, Sun Z, Price KN, et al. Annual hazard rates of recurrence for breast cancer during 24 years of follow-up: results from the International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I to V. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:927–35.

44. Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2011;378:771–84.

45. Dowsett M, Forbes JF, Bradley R, et al. Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: patient-level meta-analysis of the randomised trials. Lancet 2015;386:1341–52.

46. Davies C, Pan H, Godwin J, et al. Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trial. Lancet 2013;381:805–16.

47. Gray R, Rea D, Handley K, et al. aTTom: Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years in 6,953 women with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31 (suppl):5.

48. Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. Randomized trial of letrozole following tamoxifen as extended adjuvant therapy in receptor-positive breast cancer: updated findings from NCIC CTG MA.17. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:1262–71.

49. Mamounas EP, Jeong JH, Wickerham DL, et al. Benefit from exemestane as extended adjuvant therapy after 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen: intention-to-treat analysis of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-33 trial. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1965–71.

50. Filipits M, Nielsen TO, Rudas M, et al. The PAM50 risk-of-recurrence score predicts risk for late distant recurrence after endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:1298–305.

51. Sestak I, Cuzick J, Dowsett M, et al. Prediction of late distant recurrence after 5 years of endocrine treatment: a combined analysis of patients from the Austrian breast and colorectal cancer study group 8 and arimidex, tamoxifen alone or in combination randomized trials using the PAM50 risk of recurrence score. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:916–22.

52. Dubsky P, Brase JC, Jakesz R, et al. The EndoPredict score provides prognostic information on late distant metastases in ER+/HER2- breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2013;109:2959–64.

53. Buus R, Sestak I, Kronenwett R, et al. Comparison of EndoPredict and EPclin with Oncotype DX Recurrence Score for prediction of risk of distant recurrence after endocrine therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108:djw149.

54. Muller BM, Keil E, Lehmann A, et al. The EndoPredict gene-expression assay in clinical practice - performance and impact on clinical decisions. PLoS One 2013;8:e68252.

55. Sgroi DC, Chapman JA, Badovinac-Crnjevic T, et al. Assessment of the prognostic and predictive utility of the Breast Cancer Index (BCI): an NCIC CTG MA.14 study. Breast Cancer Res 2016;18:1.

56. Sgroi DC, Carney E, Zarrella E, et al. Prediction of late disease recurrence and extended adjuvant letrozole benefit by the HOXB13/IL17BR biomarker. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:1036–42.

57. Sanft T, Aktas B, Schroeder B, et al. Prospective assessment of the decision-making impact of the Breast Cancer Index in recommending extended adjuvant endocrine therapy for patients with early-stage ER-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;154:533–41.

Introduction

Over the past several decades, while the incidence of breast cancer has increased, breast cancer mortality has decreased. This decrease is likely due to both early detection and advances in systemic therapy. However, with more widespread use of screening mammography, there are increasing concerns about potential overdiagnosis of cancer.1 One key challenge is that breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease. Improved tools for determining breast cancer biology can help physicians individualize treatments. Patients with low-risk cancers can be approached with less aggressive treatments, thus preventing unnecessary toxicities, while those with higher-risk cancers remain treated appropriately with more aggressive therapies.

Traditionally, adjuvant chemotherapy was recommended based on tumor features such as stage (tumor size, regional nodal involvement), grade, expression of hormone receptors (estrogen receptor [ER] and progesterone receptor [PR]) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2), and patient features (age, menopausal status). However, this approach is not accurate enough to guide individualized treatment approaches, which are based on the risk for recurrence and the reduction in this risk that can be achieved with various systemic treatments. In particular, women with low-risk hormone receptor (HR)–positive, HER2-negative breast cancers could be spared the toxicities of cytotoxic chemotherapies without compromising the prognosis.

Beyond chemotherapy, endocrine therapies also have risks, especially when given over extended periods of time. Recently, extended endocrine therapy has been shown to prevent late recurrences of HR-positive breast cancers. In the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group’s MA.17R study, extended endocrine therapy with letrozole for a total of 10 years (beyond 5 years of an aromatase inhibitor [AI]) decreased the risk for breast cancer recurrence or the occurrence of contralateral breast cancer by 34%.2 However, the overall survival was similar between the 2 groups and the disease-free survival benefits were not confirmed in other studies.3–5 Identifying the subgroup of patients who benefit from this extended AI therapy is important in the era of personalized medicine. Several tumor genomic assays have been developed to provide additional prognostic and predictive information with the goal of individualizing adjuvant therapies for breast cancer. Although assays are also being evaluated in HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer, this review will focus on HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer.

Tests for Guiding Adjuvant Chemotherapy Decisions

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 54-year-old postmenopausal woman with no significant past medical history presents with an abnormal screening mammogram, which shows a focal asymmetry in the 10 o’clock position at middle depth of the left breast. Further work-up with a diagnostic mammogram and ultrasound of the left breast shows a suspicious hypoechoic solid mass with irregular margins measuring 17 mm. The patient undergoes an ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the suspicious mass, the results of which are consistent with an invasive ductal carcinoma, Nottingham grade 2, ER strongly positive (95%), PR weakly positive (5%), HER2-negative, and Ki-67 of 15%. She undergoes a left partial mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy, with final pathology demonstrating a single focus of invasive ductal carcinoma, measuring 2.2 cm in greatest dimension with no evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Margins are clear and 2 sentinel lymph nodes are negative for metastatic disease (final pathologic stage IIA, pT2 pN0 cM0). She is referred to medical oncology to discuss adjuvant systemic therapy.

- Can additional testing be used to determine prognosis and guide systemic therapy recommendations for early-stage HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer?

After a diagnosis of early-stage breast cancer, the key clinical question faced by the patient and medical oncologist is: what is the individual’s risk for a metastatic breast cancer recurrence and thus the risk for death due to breast cancer? Once the risk for recurrence is established, systemic adjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and/or HER2-directed therapy are considered based on the receptor status (ER/PR and HER2) to reduce this risk. HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer is the most common type of breast cancer. Although adjuvant endocrine therapy has significantly reduced the risk for recurrence and improved survival for patients with HR-positive breast cancer,6 the role of adjuvant chemotherapy for this subset of breast cancer remains unclear. Prior to genomic testing, the recommendation for adjuvant chemotherapy for HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors was primarily based on patient age and tumor stage and grade. However, chemotherapy overtreatment remained a concern given the potential short- and long-term risks of chemotherapy. Further studies into HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors have shown that these tumors can be divided into 2 main subtypes, luminal A and luminal B.7 These subtypes represent unique biology and differ in terms of prognosis and response to endocrine therapy and chemotherapy. Luminal A tumors are strongly endocrine responsive and have a good prognosis, while luminal B tumors are less endocrine responsive and are associated with a poorer prognosis; the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy is often considered for luminal B tumors.8 Several tests, including tumor genomic assays, are now available to help with delineating the tumor subtype and aid in decision-making regarding adjuvant chemotherapy for HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancers.

Ki-67 Assays, Including IHC4 and PEPI

Proliferation is a hallmark of cancer cells.9 Ki-67, a nuclear nonhistone protein whose expression varies in intensity throughout the cell cycle, has been used as a measurement of tumor cell proliferation.10 Two large meta-analyses have demonstrated that high Ki-67 expression in breast tumors is independently associated with worse disease-free and overall survival rates.11,12 Ki-67 expression has also been used to classify HR-positive tumors as luminal A or B. After classifying tumor subtypes based on intrinsic gene expression profiling, Cheang and colleagues determined that a Ki-67 cut point of 13.25% differentiated luminal A and B tumors.13 However, the ideal cut point for Ki-67 remains unclear, as the sensitivity and specificity in this study was 77% and 78%, respectively. Others have combined Ki-67 with standard ER, PR, and HER2 testing. This immunohistochemical 4 (IHC4) score, which weighs each of these variables, was validated in postmenopausal patients from the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial who had ER-positive tumors and did not receive chemotherapy.14 The prognostic information from the IHC4 was similar to that seen with the 21-gene recurrence score (Oncotype DX), which is discussed later in this article. The key challenge with Ki-67 testing currently is the lack of a validated test methodology and intra-observer variability in interpreting the Ki-67 results.15 Recent series have suggested that Ki-67 be considered as a continuous marker rather than a set cut point.16 These issues continue to impact the clinical utility of Ki-67 for decision-making for adjuvant chemotherapy.

Ki-67 and the preoperative endocrine prognostic index (PEPI) score have been explored in the neoadjuvant setting to separate postmenopausal women with endocrine-sensitive versus intrinsically resistant disease and identify patients at risk for recurrent disease.17 The on-treatment levels of Ki-67 in response to endocrine therapy have been shown to be more prognostic than baseline values, and a decrease in Ki-67 as early as 2 weeks after initiation of neoadjuvant endocrine therapy is associated with endocrine-sensitive tumors and improved outcome. The PEPI score was developed through retrospective analysis of the P024 trial18 to evaluate the relationship between post-neoadjuvant endocrine therapy tumor characteristics and risk for early relapse. The score was subsequently validated in an independent data set from the IMPACT (Immediate Preoperative Anastrozole, Tamoxifen, or Combined with Tamoxifen) trial.19 Patients with low pathological stage (0 or 1) and a favorable biomarker profile (PEPI score 0) at surgery had the best prognosis in the absence of chemotherapy. On the other hand, higher pathological stage at surgery and a poor biomarker profile with loss of ER positivity or persistently elevated Ki-67 (PEPI score of 3) identified de novo endocrine-resistant tumors that are higher risk for early relapse.20 The ongoing Alliance A011106 ALTERNATE trial (ALTernate approaches for clinical stage II or III Estrogen Receptor positive breast cancer NeoAdjuvant TrEatment in postmenopausal women, NCT01953588) is a phase 3 study to prospectively test this hypothesis.

21-Gene Recurrence Score (Onco type DX Assay)

The 21-gene Oncotype DX assay is conducted on paraffin-embedded tumor tissue and measures the expression of 16 cancer related genes and 5 reference genes using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The genes included in this assay are mainly related to proliferation (including Ki-67), invasion, and HER2 or estrogen signaling.21 Originally, the 21-gene recurrence score assay was analyzed as a prognostic biomarker tool in a prospective-retrospective biomarker substudy of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-14 clinical trial in which patients with node-negative, ER-positive tumors were randomly assigned to receive tamoxifen or placebo without chemotherapy.22 Using the standard reported values of low risk (< 18), intermediate risk (18–30), or high risk (≥ 31) for recurrence, among the tamoxifen-treated patients, cancers with a high-risk recurrence score had a significantly worse rate of distant recurrence and overall survival.21 Inferior breast cancer survival in cancers with a high recurrence score was also confirmed in other series of endocrine-treated patients with node-negative and node-positive disease.23–25

The predictive utility of the 21-gene recurrence score for endocrine therapy has also been evaluated. A comparison of the placebo- and tamoxifen-treated patients from the NSABP B-14 trial demonstrated that the 21-gene recurrence score predicted benefit from tamoxifen in cancers with low- or intermediate-risk recurrence scores.26 However, there was no benefit from the use of tamoxifen over placebo in cancers with high-risk recurrence scores. To date, this intriguing data has not been prospectively confirmed, and thus the 21-gene recurrence score is not used to avoid endocrine therapy.

The 21-gene recurrence score is primarily used by oncologists to aid in decision-making regarding adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-negative and node-positive (with up to 3 positive lymph nodes), HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancers. The predictive utility of the 21-gene recurrence score for adjuvant chemotherapy was initially tested using tumor samples from the NSABP B-20 study. This study initially compared adjuvant tamoxifen alone with tamoxifen plus chemotherapy in patients with node-negative, HR-positive tumors. The prospective-retrospective biomarker analysis showed that the patients with high-risk 21-gene recurrence scores benefited from the addition of chemotherapy, whereas those with low or intermediate risk did not have an improved freedom from distant recurrence with chemotherapy.27 Similarly, an analysis from the prospective phase 3 Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) 8814 trial comparing tamoxifen to tamoxifen with chemotherapy showed that for node-positive tumors, chemotherapy benefit was only seen in those with high 21-gene recurrence scores.24

Prospective studies are now starting to report results regarding the predictive role of the 21-gene recurrence score. The TAILORx (Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment) trial includes women with node-negative, HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors measuring 0.6 to 5 cm. All patients were treated with standard-of-care endocrine therapy for at least 5 years. Chemotherapy was determined based on the 21-gene recurrence score results on the primary tumor. The 21-gene recurrence score cutoffs were changed to low (0–10), intermediate (11–25), and high (≥ 26). Patients with scores of 26 or higher were treated with chemotherapy, and those with intermediate scores were randomly assigned to chemotherapy or no chemotherapy; results from this cohort are still pending. However, excellent breast cancer outcomes with endocrine therapy alone were reported from the 1626 (15.9% of total cohort) prospectively followed patients with low recurrence score tumors. The 5-year invasive disease-free survival was 93.8%, with overall survival of 98%.28 Given that 5 years is appropriate follow-up to see any chemotherapy benefit, this data supports the recommendation for no chemotherapy in this cohort of patients with very low 21-gene recurrence scores.

The RxPONDER (Rx for Positive Node, Endocrine Responsive Breast Cancer) trial is evaluating women with 1 to 3 node-positive, HR-positive, HER2-negative tumors. In this trial, patients with 21-gene recurrence scores of 0 to 25 were assigned to adjuvant chemotherapy or none. Those with scores of 26 or higher were assigned to chemotherapy. All patients received standard adjuvant endocrine therapy. This study has completed accrual and results are pending. Of note, TAILORx and RxPONDER did not investigate the potential lack of benefit of endocrine therapy in cancers with high recurrence scores. Furthermore, despite data suggesting that chemotherapy may not even benefit women with 4 or more nodes involved but who have a low recurrence score,24 due to the lack of prospective data in this cohort and the quite high risk for distant recurrence, chemotherapy continues to be the standard of care for these patients.

PAM50 (Breast Cancer Prognostic Gene Signature)

Using microarray and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, the Breast Cancer Prognostic Gene Signature (PAM50) assay was initially developed to identify intrinsic breast cancer subtypes, including luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, and basal-like.7,29 Based on the prediction analysis of microarray (PAM) method, the assay measures the expression levels of 50 genes, provides a risk category (low, intermediate, and high), and generates a numerical risk of recurrence score (ROR). The intrinsic subtype and ROR have been shown to add significant prognostic value to the clinicopathological characteristics of tumors. Clinical validity of PAM50 was evaluated in postmenopausal women with HR-positive early-stage breast cancer treated in the prospective ATAC and ABCSG-8 (Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group 8) trials.30,31 In 1017 patients with ER-positive breast cancer treated with anastrozole or tamoxifen in the ATAC trial, ROR added significant prognostic information beyond the clinical treatment score (integrated prognostic information from nodal status, tumor size, histopathologic grade, age, and anastrozole or tamoxifen treatment) in all patients. Also, compared with the 21-gene recurrence score, ROR provided more prognostic information in ER-positive, node-negative disease and better differentiation of intermediate- and higher-risk groups. Fewer patients were categorized as intermediate risk by ROR and more as high risk, which could reduce the uncertainty in the estimate of clinical benefit from chemotherapy.30 The clinical utility of PAM50 as a prognostic model was also validated in 1478 postmenopausal women with ER-positive early-stage breast cancer enrolled in the ABCSG-8 trial. In this study, ROR assigned 47% of patients with node-negative disease to the low-risk category. In this low-risk group, the 10-year metastasis risk was less than 3.5%, indicating lack of benefit from additional chemotherapy.31 A key limitation of the PAM50 is the lack of any prospective studies with this assay.

PAM50 has been designed to be carried out in any qualified pathology laboratory. Moreover, the ROR score provides additional prognostic information about risk of late recurrence, which will be discussed in the next section.

70-Gene Breast Cancer Recurrence Assay (MammaPrint)

MammaPrint is a 70-gene assay that was initially developed using an unsupervised, hierarchical clustering algorithm on whole-genome expression arrays with early-stage breast cancer. Among 295 consecutive patients who had MammaPrint testing, those classified with a good-prognosis tumor signature (n = 115) had an excellent 10-year survival rate (94.5%) compared to those with a poor-prognosis signature (54.5%), and the signature remained prognostic upon multivariate analysis.32 Subsequently, a pooled analysis comparing outcomes by MammaPrint score in patients with node-negative or 1 to 3 node-positive breast cancers treated as per discretion of their medical team with either adjuvant chemotherapy plus endocrine therapy or endocrine therapy alone reported that only those patients with a high-risk score benefited from chemotherapy.33 Recently, a prospective phase 3 study (MINDACT [Microarray In Node negative Disease may Avoid ChemoTherapy]) evaluating the utility of MammaPrint for adjuvant chemotherapy decision-making reported results.34 In this study, 6693 women with early-stage breast cancer were assessed by clinical risk and genomic risk using MammaPrint. Those with low clinical and genomic risk did not receive chemotherapy, while those with high clinical and genomic risk all received chemotherapy. The primary goal of the study was to assess whether forgoing chemotherapy would be associated with a low rate of recurrence in those patients with a low-risk prognostic MammaPrint signature but high clinical risk. A total of 1550 patients (23.2%) were in the discordant group, and the majority of these patients had HR-positive disease (98.1%). Without chemotherapy, the rate of survival without distant metastasis at 5 years in this group was 94.7% (95% confidence interval [CI] 92.5% to 96.2%), which met the primary endpoint. Of note, initially, MammaPrint was only available for fresh tissue analysis, but recent advances in RNA processing now allow for this analysis on FFPE tissue.35

Summary

These genomic and biomarker assays can identify different subsets of HR-positive breast cancers, including those patients who have tumors with an excellent prognosis with endocrine therapies alone. Thus, we now have the tools to help avoid the toxicities of chemotherapy in many women with early-stage breast cancer.

Tests for Assessing Risk for Late Recurrence

Case Continued

The patient undergoes 21-gene recurrence score testing, which shows a low recurrence score of 10, estimating the 10-year risk of distant recurrence to be approximately 7% with 5 years of tamoxifen. Chemotherapy is not recommended. The patient completes adjuvant whole breast radiation therapy, and then, based on data supporting AIs over tamoxifen in postmenopausal women, she is started on anastrozole.41 She initially experiences mild side effects from treatment, including fatigue, arthralgia, and vaginal dryness, but her symptoms are able to be managed. As she approaches 5 years of adjuvant endocrine therapy with anastrozole, she is struggling with rotator cuff injury and is anxious about recurrence, but has no evidence of recurrent cancer. Her bone density scan in the beginning of her fourth year of therapy shows a decrease in bone mineral density, with the lowest T score of –1.5 at the left femoral neck, consistent with osteopenia. She has been treated with calcium and vitamin D supplements.

- How long should this patient continue treatment with anastrozole?

The risk for recurrence is highest during the first 5 years after diagnosis for all patients with early breast cancer.42 Although HR-positive breast cancers have a better prognosis than HR-negative disease, the pattern of recurrence is different between the 2 groups, and it is estimated that approximately half of the recurrences among patients with HR-positive early breast cancer occur after the first 5 years from diagnosis. Annualized hazard of recurrence in HR-positive breast cancer has been shown to remain elevated and fairly stable beyond 10 years, even for those with low tumor burden and node-negative disease.43 Prospective trials showed that for women with HR-positive early breast cancer, 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen could substantially reduce recurrence rates and improve survival, and this became the standard of care.44 AIs are considered the standard of care for adjuvant endocrine therapy in most postmenopausal women, as they result in a significantly lower recurrence rate compared with tamoxifen, either as initial adjuvant therapy or sequentially following 2 to 3 years of tamoxifen.45

Due to the risk for later recurrences with HR-positive breast cancer, more patients and oncologists are considering extended endocrine therapy. This is based on results from the ATLAS (Adjuvant Tamoxifen: Longer Against Shorter) and aTTOM (Adjuvant Tamoxifen–To Offer More?) studies, both of which showed that women with HR-positive breast cancer who continued tamoxifen for 10 years had a lower late recurrence rate and a lower breast cancer mortality rate compared with those who stopped at 5 years.46,47 Furthermore, the NCIC MA.17 trial evaluated extended endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with 5 years of letrozole following 5 years of tamoxifen. Letrozole was shown to improve both disease-free and distant disease-free survival. The overall survival benefit was limited to patients with node-positive disease.48 A summary of studies of extended endocrine therapy for HR-positive breast cancers is shown in Table 2.2,3,46–49

However, extending AI therapy from 5 years to 10 years is not clearly beneficial. In the MA.17R trial, although longer AI therapy resulted in significantly better disease-free survival (95% versus 91%, hazard ratio 0.66, P = 0.01), this was primarily due to a lower incidence of contralateral breast cancer in those taking the AI compared with placebo. The distant recurrence risks were similar and low (4.4% versus 5.5%), and there was no overall survival difference.2 Also, the NSABP B-42 study, which was presented at the 2016 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, did not meet its predefined endpoint for benefit from extending adjuvant AI therapy with letrozole beyond 5 years.3 Thus, the absolute benefit from extended endocrine therapy has been modest across these studies. Although endocrine therapy is considered relatively safe and well tolerated, side effects can be significant and even associated with morbidity. Ideally, extended endocrine therapy should be offered to the subset of patients who would benefit the most. Several genomic diagnostic assays, including the EndoPredict test, PAM50, and the Breast Cancer Index (BCI) tests, specifically assess the risk for late recurrence in HR-positive cancers.

PAM50

Studies suggest that the ROR score also has value in predicting late recurrences. Analysis of data in patients enrolled in the ABCSG-8 trial showed that ROR could identify patients with endocrine-sensitive disease who are at low risk for late relapse and could be spared from unwanted toxicities of extended endocrine therapies. In 1246 ABCSG-8 patients between years 5 and 15, the PAM50 ROR demonstrated an absolute risk of distant recurrence of 2.4% in the low-risk group, as compared with 17.5% in the high-risk group.50 Also, a combined analysis of patients from both the ATAC and ABCSG-8 trials demonstrated the utility of ROR in identifying this subgroup of patients with low risk for late relapse.51

EndoPredict

EndoPredict is another quantitative RT-PCR–based assay which uses FFPE tissues to calculate a risk score based on 8 cancer-related and 3 reference genes. The score is combined with clinicopathological factors including tumor size and nodal status to make a comprehensive risk score (EPclin). EPclin is used to dichotomize patients into EndoPredict low- and high-risk groups. EndoPredict has been validated in 2 cohorts of patients enrolled in separate randomized studies, ABCSG-6 and ABCSG-8. EP provided prognostic information beyond clinicopathological variables to predict distant recurrence in patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative early breast cancer.37 More important, EndoPredict has been shown to predict early (years 0–5) versus late (> 5 years after diagnosis) recurrences and identify a low-risk subset of patients who would not be expected to benefit from further treatment beyond 5 years of endocrine therapy.52 Recently, EndoPredict and EPclin were compared with the 21-gene (Oncotype DX) recurrence score in a patient population from the TransATAC study. Both EndoPredict and EPclin provided more prognostic information compared to the 21-gene recurrence score and identified early and late relapse events.53 EndoPredict is the first multigene expression assay that could be routinely performed in decentralized molecular pathological laboratories with a short turnaround time.54

Breast Cancer Index

The BCI is a RT-PCR–based gene expression assay that consists of 2 gene expression biomarkers: molecular grade index (MGI) and HOXB13/IL17BR (H/I). The BCI was developed as a prognostic test to assess risk for breast cancer recurrence using a cohort of ER-positive patients (n = 588) treated with adjuvant tamoxifen versus observation from the prospective randomized Stockholm trial.38 In this blinded retrospective study, H/I and MGI were measured and a continuous risk model (BCI) was developed in the tamoxifen-treated group. More than 50% of the patients in this group were classified as having a low risk of recurrence. The rate of distant recurrence or death in this low-risk group at 10 years was less than 3%. The performance of the BCI model was then tested in the untreated arm of the Stockholm trial. In the untreated arm, BCI classified 53%, 27%, and 20% of patients as low, intermediate, and high risk, respectively. The rate of distant metastasis at 10 years in these risk groups was 8.3% (95% CI 4.7% to 14.4%), 22.9% (95% CI 14.5% to 35.2%), and 28.5% (95% CI 17.9% to 43.6%), respectively, and the rate of breast cancer–specific mortality was 5.1% (95% CI 1.3% to 8.7%), 19.8% (95% CI 10.0% to 28.6%), and 28.8% (95% CI 15.3% to 40.2%).38

The prognostic and predictive values of the BCI have been validated in other large, randomized studies and in patients with both node-negative and node-positive disease.39,55 The predictive value of the endocrine-response biomarker, the H/I ratio, has been demonstrated in randomized studies. In the MA.17 trial, a high H/I ratio was associated with increased risk for late recurrence in the absence of letrozole. However, extended endocrine therapy with letrozole in patients with high H/I ratios predicted benefit from therapy and decreased the probability of late disease recurrence.56 BCI was also compared to IHC4 and the 21-gene recurrence score in the TransATAC study and was the only test to show prognostic significance for both early (0–5 years) and late (5–10 year) recurrence.40

The impact of the BCI results on physicians’ recommendations for extended endocrine therapy was assessed by a prospective study. This study showed that the test result had a significant effect on both physician treatment recommendation and patient satisfaction. BCI testing resulted in a change in physician recommendations for extended endocrine therapy, with an overall decrease in recommendations for extended endocrine therapy from 74% to 54%. Knowledge of the test result also led to improved patient satisfaction and decreased anxiety.57

Summary

Due to the risk for late recurrence, extended endocrine therapy is being recommended for many patients with HR-positive breast cancers. Multiple genomic assays are being developed to better understand an individual’s risk for late recurrence and the potential for benefit from extended endocrine therapies. However, none of the assays has been validated in prospective randomized studies. Further validation is needed prior to routine use of these assays.

Case Continued

A BCI test is done and the result shows 4.3% BCI low-risk category in years 5–10, which is consistent with a low likelihood of benefit from extended endocrine therapy. After discussing the results of the BCI test in the context of no survival benefit from extending AIs beyond 5 years, both the patient and her oncologist feel comfortable with discontinuing endocrine therapy at the end of 5 years.

Conclusion

Reduction in breast cancer mortality is mainly the result of improved systemic treatments. With advances in breast cancer screening tools in recent years, the rate of cancer detection has increased. This has raised concerns regarding overdiagnosis. To prevent unwanted toxicities associated with overtreatment, better treatment decision tools are needed. Several genomic assays are currently available and widely used to provide prognostic and predictive information and aid in decisions regarding appropriate use of adjuvant chemotherapy in HR-positive/HER2-negative early-stage breast cancer. Ongoing studies are refining the cutoffs for these assays and expanding the applicability to node-positive breast cancers. Furthermore, with several studies now showing benefit from the use of extended endocrine therapy, some of these assays may be able to identify the subset of patients who are at increased risk for late recurrence and who might benefit from extended endocrine therapy. Advances in molecular testing has enabled clinicians to offer more personalized treatments to their patients, improve patients’ compliance, and decrease anxiety and conflict associated with management decisions. Although small numbers of patients with HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancers were also included in some of these studies, use of genomic assays in this subset of patients is very limited and currently not recommended.

Introduction

Over the past several decades, while the incidence of breast cancer has increased, breast cancer mortality has decreased. This decrease is likely due to both early detection and advances in systemic therapy. However, with more widespread use of screening mammography, there are increasing concerns about potential overdiagnosis of cancer.1 One key challenge is that breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease. Improved tools for determining breast cancer biology can help physicians individualize treatments. Patients with low-risk cancers can be approached with less aggressive treatments, thus preventing unnecessary toxicities, while those with higher-risk cancers remain treated appropriately with more aggressive therapies.

Traditionally, adjuvant chemotherapy was recommended based on tumor features such as stage (tumor size, regional nodal involvement), grade, expression of hormone receptors (estrogen receptor [ER] and progesterone receptor [PR]) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2), and patient features (age, menopausal status). However, this approach is not accurate enough to guide individualized treatment approaches, which are based on the risk for recurrence and the reduction in this risk that can be achieved with various systemic treatments. In particular, women with low-risk hormone receptor (HR)–positive, HER2-negative breast cancers could be spared the toxicities of cytotoxic chemotherapies without compromising the prognosis.

Beyond chemotherapy, endocrine therapies also have risks, especially when given over extended periods of time. Recently, extended endocrine therapy has been shown to prevent late recurrences of HR-positive breast cancers. In the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group’s MA.17R study, extended endocrine therapy with letrozole for a total of 10 years (beyond 5 years of an aromatase inhibitor [AI]) decreased the risk for breast cancer recurrence or the occurrence of contralateral breast cancer by 34%.2 However, the overall survival was similar between the 2 groups and the disease-free survival benefits were not confirmed in other studies.3–5 Identifying the subgroup of patients who benefit from this extended AI therapy is important in the era of personalized medicine. Several tumor genomic assays have been developed to provide additional prognostic and predictive information with the goal of individualizing adjuvant therapies for breast cancer. Although assays are also being evaluated in HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer, this review will focus on HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer.

Tests for Guiding Adjuvant Chemotherapy Decisions

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 54-year-old postmenopausal woman with no significant past medical history presents with an abnormal screening mammogram, which shows a focal asymmetry in the 10 o’clock position at middle depth of the left breast. Further work-up with a diagnostic mammogram and ultrasound of the left breast shows a suspicious hypoechoic solid mass with irregular margins measuring 17 mm. The patient undergoes an ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the suspicious mass, the results of which are consistent with an invasive ductal carcinoma, Nottingham grade 2, ER strongly positive (95%), PR weakly positive (5%), HER2-negative, and Ki-67 of 15%. She undergoes a left partial mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy, with final pathology demonstrating a single focus of invasive ductal carcinoma, measuring 2.2 cm in greatest dimension with no evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Margins are clear and 2 sentinel lymph nodes are negative for metastatic disease (final pathologic stage IIA, pT2 pN0 cM0). She is referred to medical oncology to discuss adjuvant systemic therapy.

- Can additional testing be used to determine prognosis and guide systemic therapy recommendations for early-stage HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer?

After a diagnosis of early-stage breast cancer, the key clinical question faced by the patient and medical oncologist is: what is the individual’s risk for a metastatic breast cancer recurrence and thus the risk for death due to breast cancer? Once the risk for recurrence is established, systemic adjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and/or HER2-directed therapy are considered based on the receptor status (ER/PR and HER2) to reduce this risk. HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer is the most common type of breast cancer. Although adjuvant endocrine therapy has significantly reduced the risk for recurrence and improved survival for patients with HR-positive breast cancer,6 the role of adjuvant chemotherapy for this subset of breast cancer remains unclear. Prior to genomic testing, the recommendation for adjuvant chemotherapy for HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors was primarily based on patient age and tumor stage and grade. However, chemotherapy overtreatment remained a concern given the potential short- and long-term risks of chemotherapy. Further studies into HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors have shown that these tumors can be divided into 2 main subtypes, luminal A and luminal B.7 These subtypes represent unique biology and differ in terms of prognosis and response to endocrine therapy and chemotherapy. Luminal A tumors are strongly endocrine responsive and have a good prognosis, while luminal B tumors are less endocrine responsive and are associated with a poorer prognosis; the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy is often considered for luminal B tumors.8 Several tests, including tumor genomic assays, are now available to help with delineating the tumor subtype and aid in decision-making regarding adjuvant chemotherapy for HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancers.

Ki-67 Assays, Including IHC4 and PEPI