User login

Special Report II: Tackling Burnout

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Endometrial Cancer: 5 Things to Know

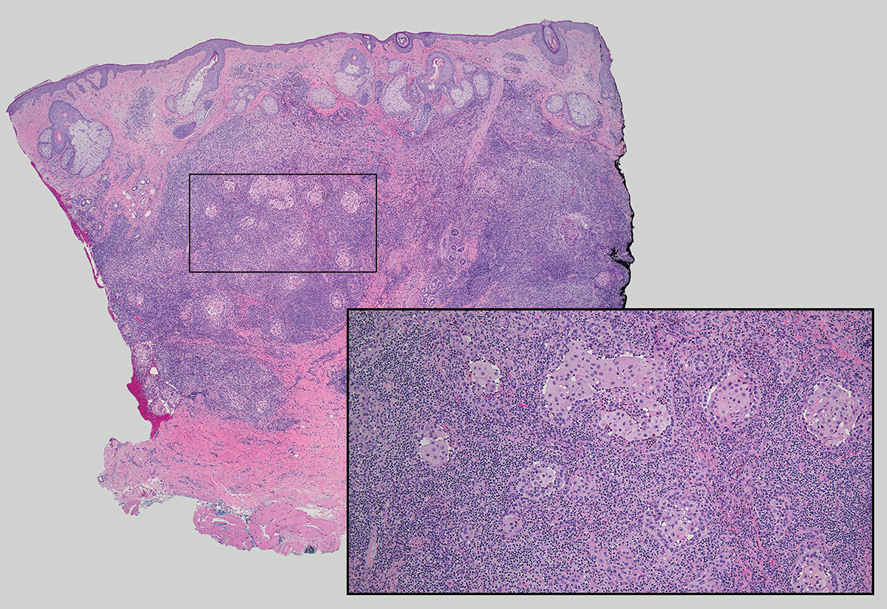

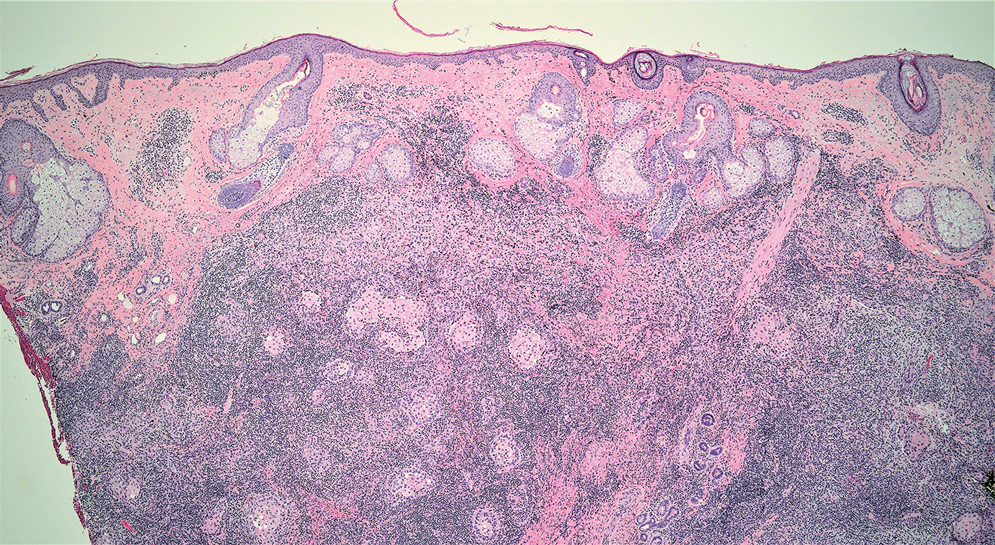

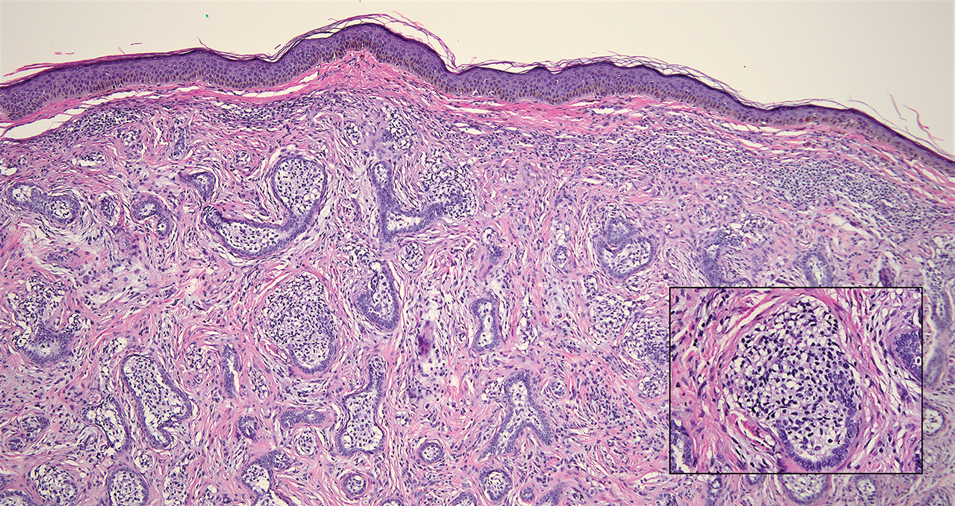

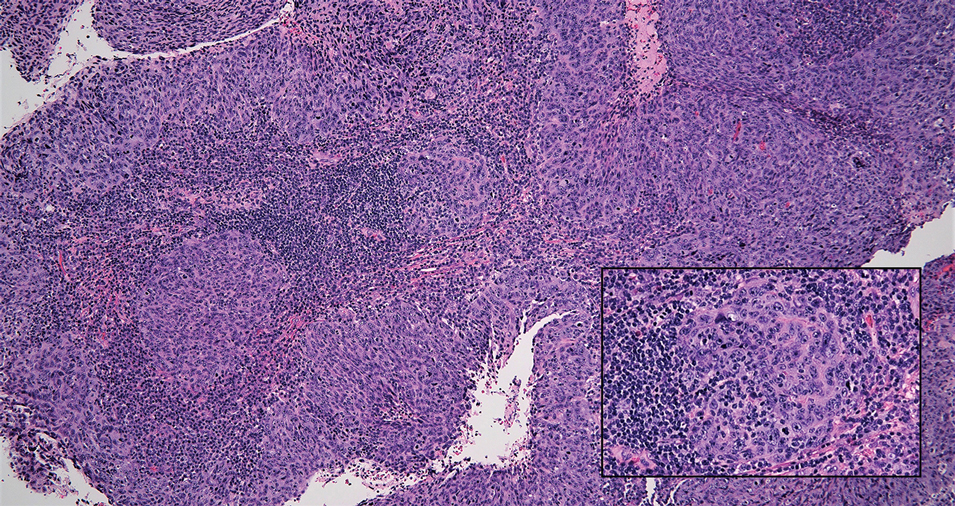

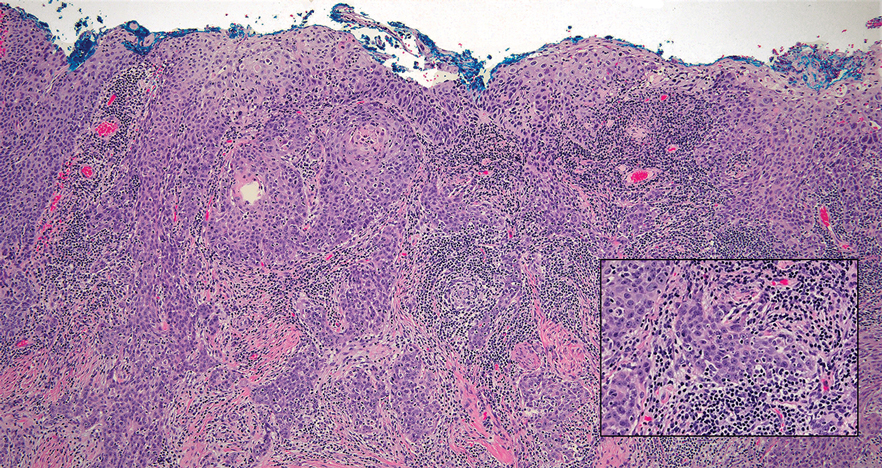

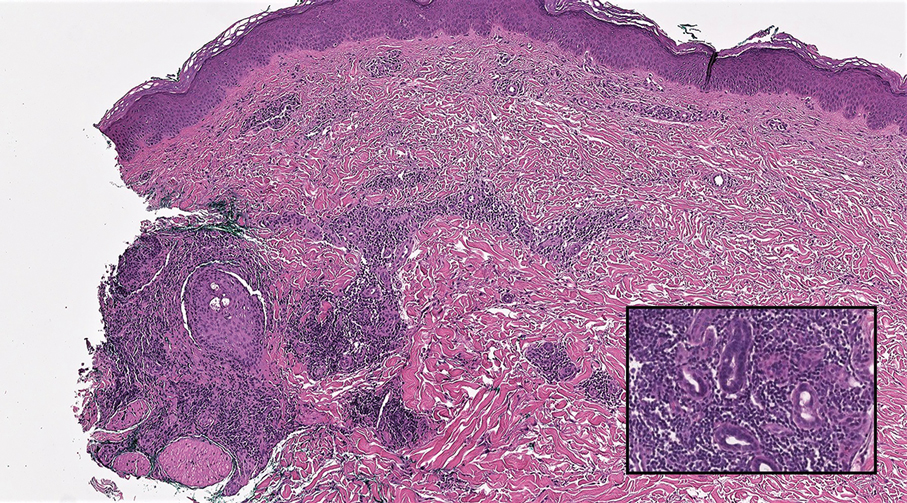

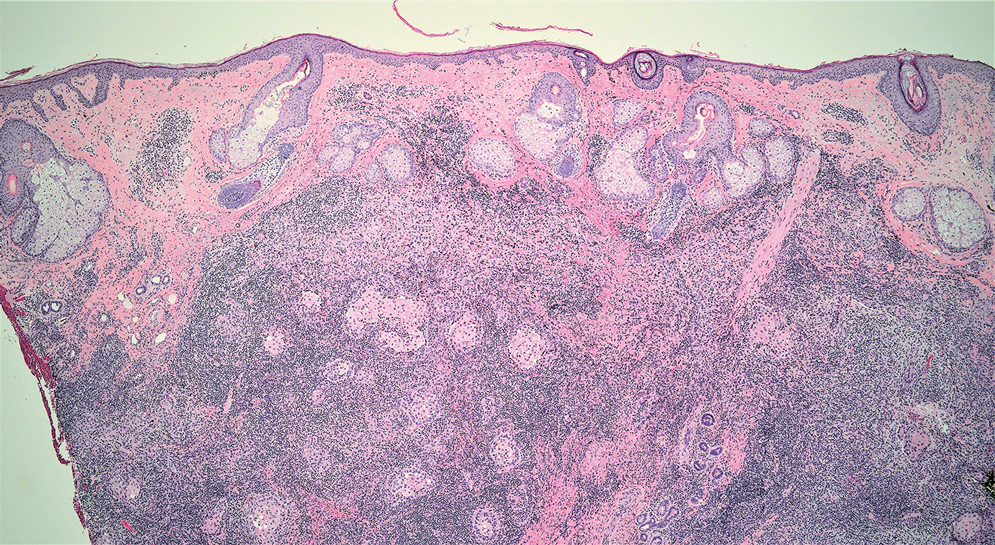

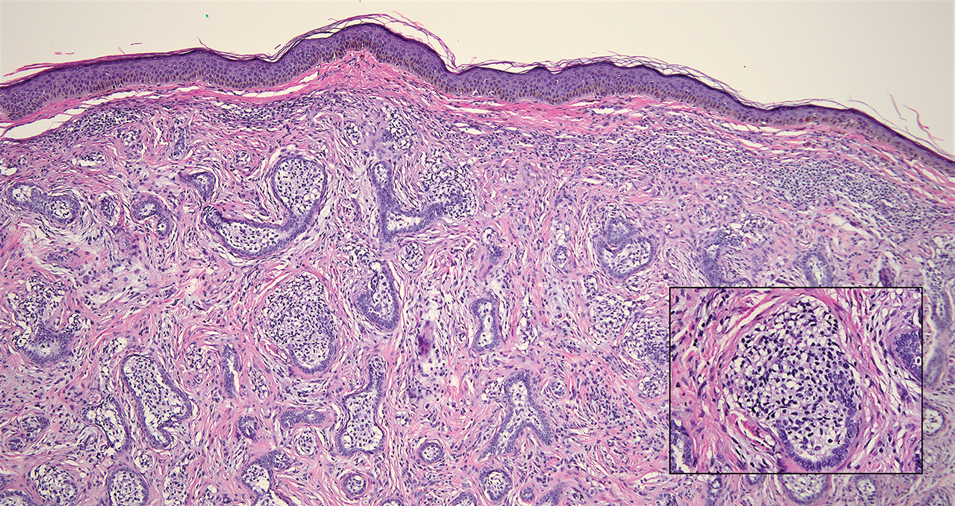

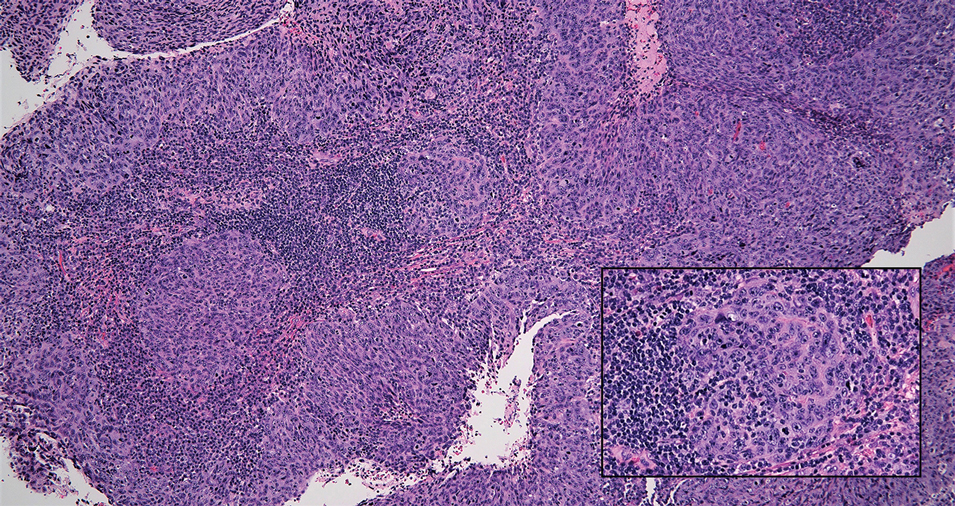

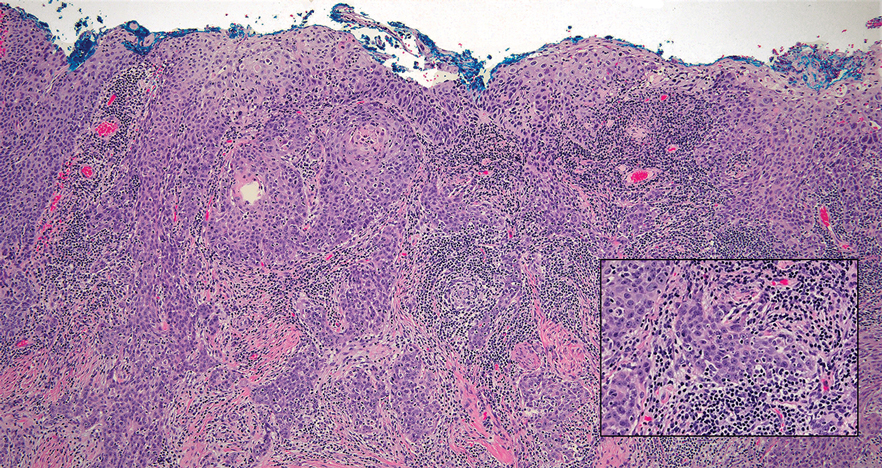

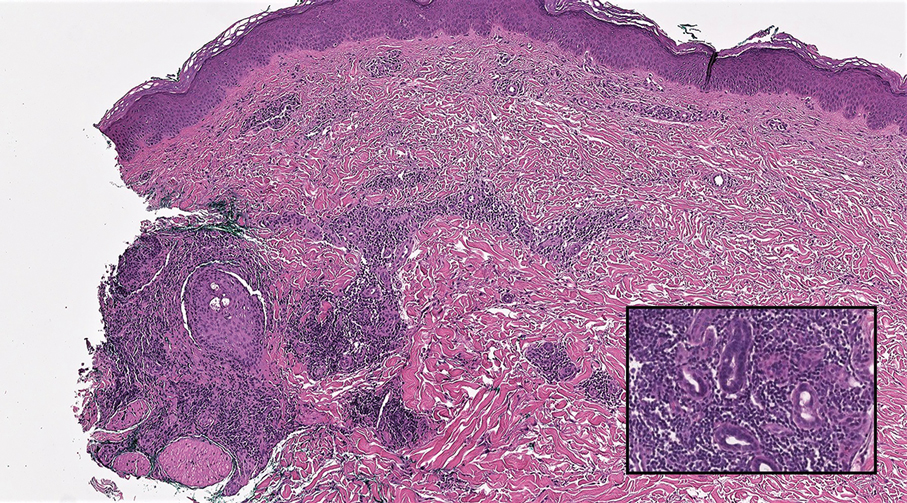

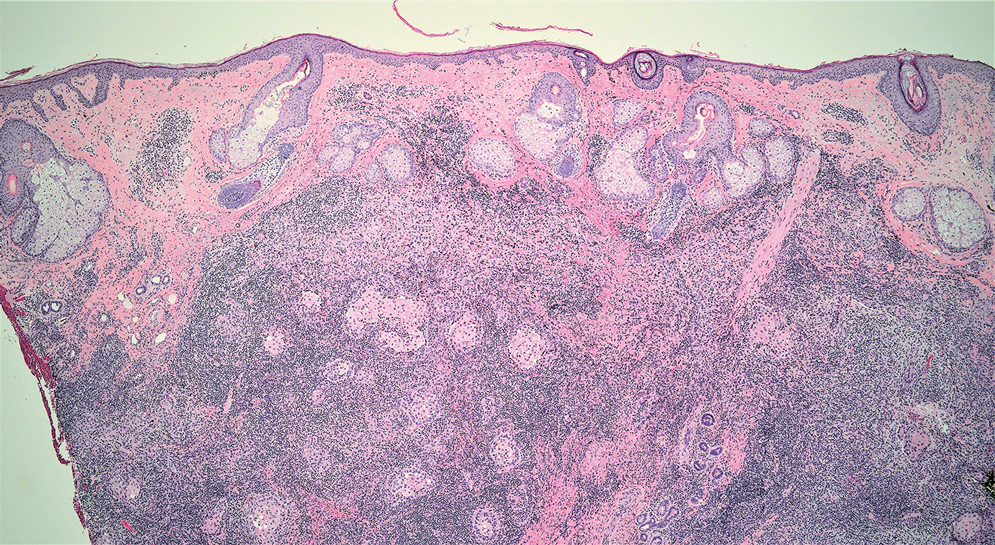

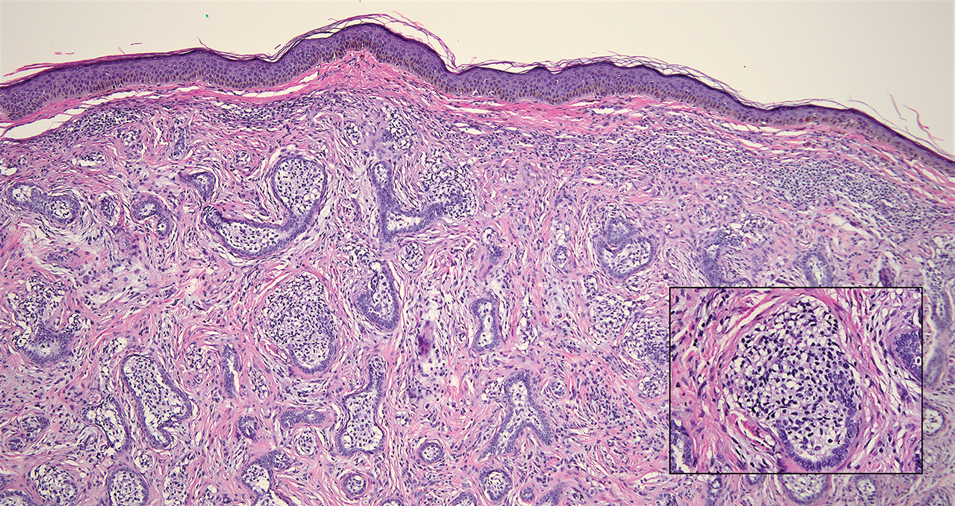

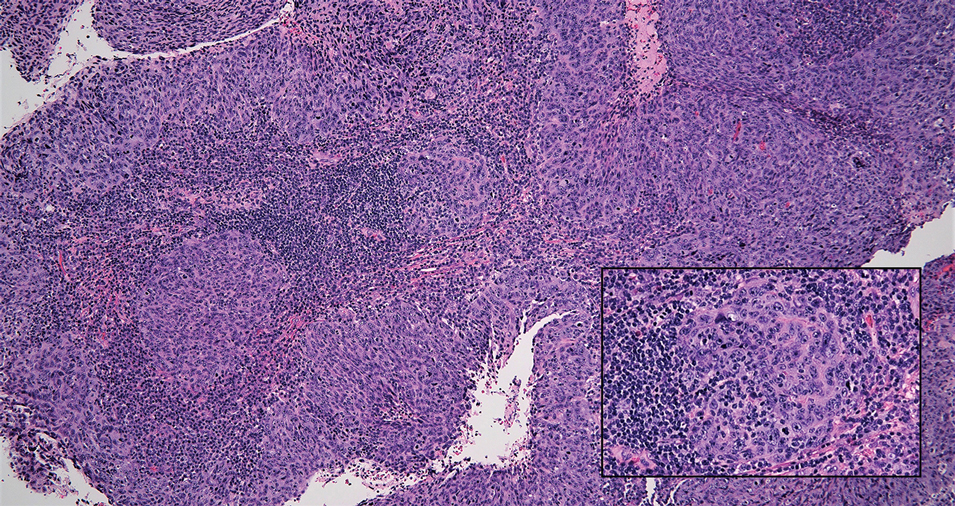

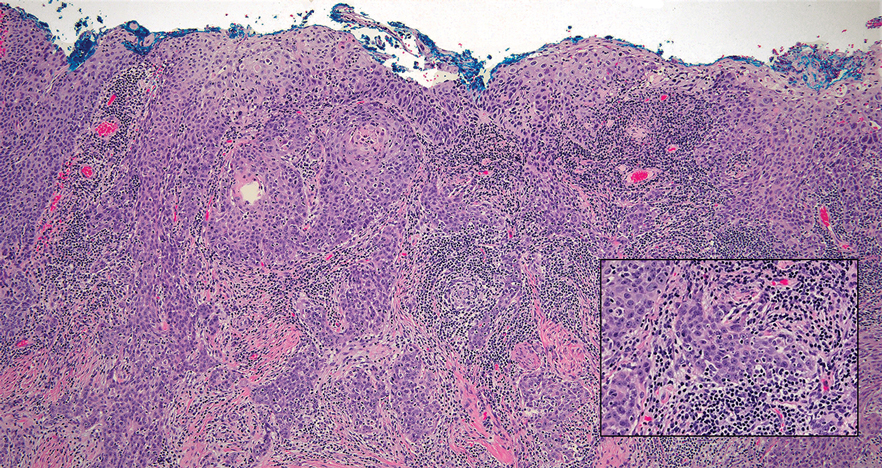

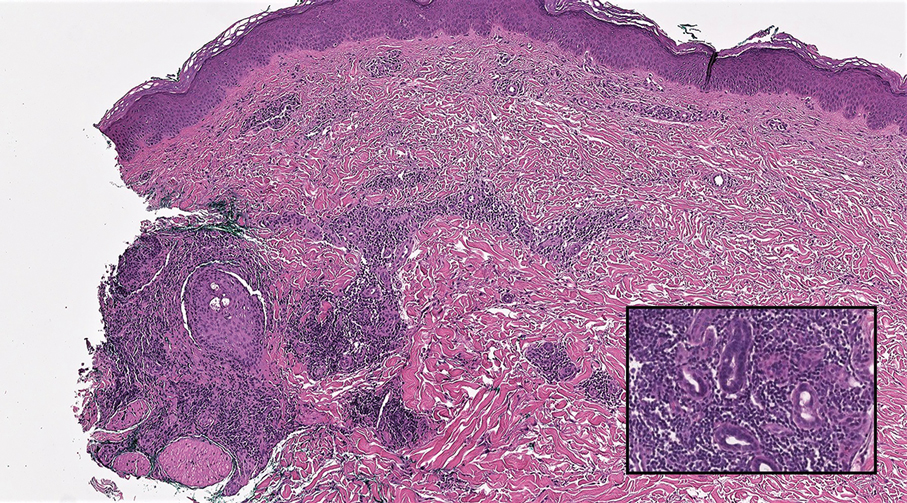

Endometrial cancer is a common type of gynecologic cancer, and its incidence is rising steadily in the United States and globally. Most cases are endometrioid adenocarcinomas, arising from the inner lining of the uterus — the endometrium. While many patients are diagnosed early because of noticeable symptoms like abnormal bleeding, trends in both incidence and mortality are concerning, especially given the persistent racial and socioeconomic disparities in outcomes.

In addition to being the most common uterine malignancy, endometrial cancer is at the forefront of precision oncology in gynecology. The traditional classification systems based on histology and hormone dependence are now being augmented by molecular subtyping that better informs prognosis and treatment. As diagnostic tools, genetic testing, and therapeutic strategies advance, the management of endometrial cancer is becoming increasingly personalized.

Here are five things to know about endometrial cancer:

1. Endometrial cancer is one of the few cancers with increasing mortality.

Endometrial cancer accounts for the majority of uterine cancers in the United States with an overall lifetime risk for women of about 1 in 40. Since the mid-2000s, incidence rates have risen steadily, by > 1% per year, reflecting both lifestyle and environmental factors. Importantly, the disease tends to be diagnosed at an early stage due to the presence of warning signs like postmenopausal bleeding, which contributes to relatively favorable survival outcomes when caught early.

However, mortality trends continue to evolve. From 1999 to 2013, death rates from endometrial cancer in the US declined slightly, but since 2013, they have increased sharply — by > 8% annually — according to recent data. This upward trend in mortality disproportionately affects non-Hispanic Black women, who experience the highest mortality rate (4.7 per 100,000) among all racial and ethnic groups. This disparity is likely caused by a complex interplay of factors, including delays in diagnosis, more aggressive tumor biology, and inequities in access to care. Addressing these disparities remains a key priority in improving outcomes.

2. Risk factors go beyond hormones and age.

Risk factors for endometrial cancer include prolonged exposure to unopposed estrogen, which can result from estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy, higher BMI, and early menarche or late menopause. Nulliparity (having never been pregnant) and older age also increase risk, as does tamoxifen use — a medication commonly prescribed for breast cancer prevention. These factors cumulatively increase endometrial proliferation and the potential for atypical cellular changes. Endometrial hyperplasia, a known precursor to cancer, is often linked to these hormonal imbalances and may require surveillance or treatment.

Beyond estrogen’s influence, a growing body of research is uncovering additional risk contributors. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), metabolic syndrome, or diabetes face elevated risk of developing endometrial cancer. Genetic syndromes, particularly Lynch and Cowden syndromes, are associated with significantly increased lifetime risks of endometrial cancer. Environmental exposures, such as the use of hair relaxers, are being investigated as emerging risk factors. Additionally, race remains a risk marker, with Black women not only experiencing higher mortality but also more aggressive subtypes of the disease. These complex, overlapping risks highlight the importance of individualized risk assessment and early intervention strategies.

3. Postmenopausal bleeding is the hallmark symptom — but not the only one.

In endometrial cancer, the majority of cases are diagnosed at an early stage, largely because of the hallmark symptom of postmenopausal bleeding. In addition to bleeding, patients may present with vaginal discharge, pyometra, and even pain and abdominal distension in advanced disease. Any bleeding in a postmenopausal woman should prompt evaluation, as it may signal endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma. In premenopausal women, irregular or heavy menstrual bleeding may raise suspicion, particularly when accompanied by risk factors such as PCOS.

The diagnostic workup for suspected endometrial cancer in women, particularly those presenting with postmenopausal bleeding, begins with a focused clinical assessment and frequently includes transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) to evaluate the endometrium. While TVUS can aid in identifying structural abnormalities or suggest malignancy, endometrial sampling is warranted in all postmenopausal women with abnormal bleeding, regardless of endometrial thickness. Office-based biopsy is the preferred initial approach due to its convenience and diagnostic yield; however, if the sample is nondiagnostic or technically difficult to obtain, hysteroscopy with directed biopsy or dilation and curettage should be pursued.

4. Classification systems are evolving to include molecular subtypes.

Historically, endometrial cancers were classified using the World Health Organization system based on histology and by hormone dependence: Type 1 (estrogen-dependent, typically endometrioid and low grade) and Type 2 (non-estrogen dependent, often serous and high grade). Type 1 cancers tend to have a better prognosis and slower progression, while Type 2 cancers are more aggressive and require intensive treatment. While helpful, this binary classification does not fully capture the biological diversity or treatment responsiveness of the disease.

The field is now moving toward molecular classification, which offers a more nuanced understanding. The four main molecular subtypes include: polymerase epsilon (POLE)-mutant, mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient, p53-abnormal, and no specific molecular profile (NSMP). These groups differ in prognosis and therapeutic implications. POLE-mutant tumors with extremely high mutational burdens generally have excellent outcomes and may not require aggressive adjuvant therapy. In contrast, p53-abnormal tumors are associated with chromosomal instability, TP53 mutations, and poor outcomes, necessitating more aggressive multimodal treatment. MMR-deficient tumors are particularly responsive to immunotherapy. These molecular distinctions are changing how clinicians approach risk stratification and management in patients with endometrial cancer.

5. Treatment is increasingly personalized — and immunotherapy is expanding.

The cornerstone of treatment for early-stage endometrial cancer is surgical: total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, often with sentinel node mapping or lymphadenectomy. Adjuvant therapy depends on factors such as stage, grade, histology, and molecular subtype. Fertility-sparing management with progestin therapy is an option for highly selected patients with early-stage, low-grade tumors. Clinical guidelines recommend that fertility desires be addressed prior to initiating treatment, as standard surgical management typically results in loss of reproductive capacity.

For advanced or recurrent disease, treatment becomes more complex and increasingly individualized. Chemotherapy, often with carboplatin and paclitaxel, is standard for stage III/IV and recurrent disease. Molecular findings now guide additional therapy: For instance, MMR-deficient tumors may respond to checkpoint inhibitors. As targeted agents and combination regimens continue to emerge, treatment of endometrial is increasingly focused on precision medicine.

Markman is professor of medical oncology and therapeutics research and President of Medicine & Science at City of Hope in Atlanta and Chicago. He has disclosed relevant financial relationships with AstraZeneca, GSK and Myriad.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Endometrial cancer is a common type of gynecologic cancer, and its incidence is rising steadily in the United States and globally. Most cases are endometrioid adenocarcinomas, arising from the inner lining of the uterus — the endometrium. While many patients are diagnosed early because of noticeable symptoms like abnormal bleeding, trends in both incidence and mortality are concerning, especially given the persistent racial and socioeconomic disparities in outcomes.

In addition to being the most common uterine malignancy, endometrial cancer is at the forefront of precision oncology in gynecology. The traditional classification systems based on histology and hormone dependence are now being augmented by molecular subtyping that better informs prognosis and treatment. As diagnostic tools, genetic testing, and therapeutic strategies advance, the management of endometrial cancer is becoming increasingly personalized.

Here are five things to know about endometrial cancer:

1. Endometrial cancer is one of the few cancers with increasing mortality.

Endometrial cancer accounts for the majority of uterine cancers in the United States with an overall lifetime risk for women of about 1 in 40. Since the mid-2000s, incidence rates have risen steadily, by > 1% per year, reflecting both lifestyle and environmental factors. Importantly, the disease tends to be diagnosed at an early stage due to the presence of warning signs like postmenopausal bleeding, which contributes to relatively favorable survival outcomes when caught early.

However, mortality trends continue to evolve. From 1999 to 2013, death rates from endometrial cancer in the US declined slightly, but since 2013, they have increased sharply — by > 8% annually — according to recent data. This upward trend in mortality disproportionately affects non-Hispanic Black women, who experience the highest mortality rate (4.7 per 100,000) among all racial and ethnic groups. This disparity is likely caused by a complex interplay of factors, including delays in diagnosis, more aggressive tumor biology, and inequities in access to care. Addressing these disparities remains a key priority in improving outcomes.

2. Risk factors go beyond hormones and age.

Risk factors for endometrial cancer include prolonged exposure to unopposed estrogen, which can result from estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy, higher BMI, and early menarche or late menopause. Nulliparity (having never been pregnant) and older age also increase risk, as does tamoxifen use — a medication commonly prescribed for breast cancer prevention. These factors cumulatively increase endometrial proliferation and the potential for atypical cellular changes. Endometrial hyperplasia, a known precursor to cancer, is often linked to these hormonal imbalances and may require surveillance or treatment.

Beyond estrogen’s influence, a growing body of research is uncovering additional risk contributors. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), metabolic syndrome, or diabetes face elevated risk of developing endometrial cancer. Genetic syndromes, particularly Lynch and Cowden syndromes, are associated with significantly increased lifetime risks of endometrial cancer. Environmental exposures, such as the use of hair relaxers, are being investigated as emerging risk factors. Additionally, race remains a risk marker, with Black women not only experiencing higher mortality but also more aggressive subtypes of the disease. These complex, overlapping risks highlight the importance of individualized risk assessment and early intervention strategies.

3. Postmenopausal bleeding is the hallmark symptom — but not the only one.

In endometrial cancer, the majority of cases are diagnosed at an early stage, largely because of the hallmark symptom of postmenopausal bleeding. In addition to bleeding, patients may present with vaginal discharge, pyometra, and even pain and abdominal distension in advanced disease. Any bleeding in a postmenopausal woman should prompt evaluation, as it may signal endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma. In premenopausal women, irregular or heavy menstrual bleeding may raise suspicion, particularly when accompanied by risk factors such as PCOS.

The diagnostic workup for suspected endometrial cancer in women, particularly those presenting with postmenopausal bleeding, begins with a focused clinical assessment and frequently includes transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) to evaluate the endometrium. While TVUS can aid in identifying structural abnormalities or suggest malignancy, endometrial sampling is warranted in all postmenopausal women with abnormal bleeding, regardless of endometrial thickness. Office-based biopsy is the preferred initial approach due to its convenience and diagnostic yield; however, if the sample is nondiagnostic or technically difficult to obtain, hysteroscopy with directed biopsy or dilation and curettage should be pursued.

4. Classification systems are evolving to include molecular subtypes.

Historically, endometrial cancers were classified using the World Health Organization system based on histology and by hormone dependence: Type 1 (estrogen-dependent, typically endometrioid and low grade) and Type 2 (non-estrogen dependent, often serous and high grade). Type 1 cancers tend to have a better prognosis and slower progression, while Type 2 cancers are more aggressive and require intensive treatment. While helpful, this binary classification does not fully capture the biological diversity or treatment responsiveness of the disease.

The field is now moving toward molecular classification, which offers a more nuanced understanding. The four main molecular subtypes include: polymerase epsilon (POLE)-mutant, mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient, p53-abnormal, and no specific molecular profile (NSMP). These groups differ in prognosis and therapeutic implications. POLE-mutant tumors with extremely high mutational burdens generally have excellent outcomes and may not require aggressive adjuvant therapy. In contrast, p53-abnormal tumors are associated with chromosomal instability, TP53 mutations, and poor outcomes, necessitating more aggressive multimodal treatment. MMR-deficient tumors are particularly responsive to immunotherapy. These molecular distinctions are changing how clinicians approach risk stratification and management in patients with endometrial cancer.

5. Treatment is increasingly personalized — and immunotherapy is expanding.

The cornerstone of treatment for early-stage endometrial cancer is surgical: total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, often with sentinel node mapping or lymphadenectomy. Adjuvant therapy depends on factors such as stage, grade, histology, and molecular subtype. Fertility-sparing management with progestin therapy is an option for highly selected patients with early-stage, low-grade tumors. Clinical guidelines recommend that fertility desires be addressed prior to initiating treatment, as standard surgical management typically results in loss of reproductive capacity.

For advanced or recurrent disease, treatment becomes more complex and increasingly individualized. Chemotherapy, often with carboplatin and paclitaxel, is standard for stage III/IV and recurrent disease. Molecular findings now guide additional therapy: For instance, MMR-deficient tumors may respond to checkpoint inhibitors. As targeted agents and combination regimens continue to emerge, treatment of endometrial is increasingly focused on precision medicine.

Markman is professor of medical oncology and therapeutics research and President of Medicine & Science at City of Hope in Atlanta and Chicago. He has disclosed relevant financial relationships with AstraZeneca, GSK and Myriad.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Endometrial cancer is a common type of gynecologic cancer, and its incidence is rising steadily in the United States and globally. Most cases are endometrioid adenocarcinomas, arising from the inner lining of the uterus — the endometrium. While many patients are diagnosed early because of noticeable symptoms like abnormal bleeding, trends in both incidence and mortality are concerning, especially given the persistent racial and socioeconomic disparities in outcomes.

In addition to being the most common uterine malignancy, endometrial cancer is at the forefront of precision oncology in gynecology. The traditional classification systems based on histology and hormone dependence are now being augmented by molecular subtyping that better informs prognosis and treatment. As diagnostic tools, genetic testing, and therapeutic strategies advance, the management of endometrial cancer is becoming increasingly personalized.

Here are five things to know about endometrial cancer:

1. Endometrial cancer is one of the few cancers with increasing mortality.

Endometrial cancer accounts for the majority of uterine cancers in the United States with an overall lifetime risk for women of about 1 in 40. Since the mid-2000s, incidence rates have risen steadily, by > 1% per year, reflecting both lifestyle and environmental factors. Importantly, the disease tends to be diagnosed at an early stage due to the presence of warning signs like postmenopausal bleeding, which contributes to relatively favorable survival outcomes when caught early.

However, mortality trends continue to evolve. From 1999 to 2013, death rates from endometrial cancer in the US declined slightly, but since 2013, they have increased sharply — by > 8% annually — according to recent data. This upward trend in mortality disproportionately affects non-Hispanic Black women, who experience the highest mortality rate (4.7 per 100,000) among all racial and ethnic groups. This disparity is likely caused by a complex interplay of factors, including delays in diagnosis, more aggressive tumor biology, and inequities in access to care. Addressing these disparities remains a key priority in improving outcomes.

2. Risk factors go beyond hormones and age.

Risk factors for endometrial cancer include prolonged exposure to unopposed estrogen, which can result from estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy, higher BMI, and early menarche or late menopause. Nulliparity (having never been pregnant) and older age also increase risk, as does tamoxifen use — a medication commonly prescribed for breast cancer prevention. These factors cumulatively increase endometrial proliferation and the potential for atypical cellular changes. Endometrial hyperplasia, a known precursor to cancer, is often linked to these hormonal imbalances and may require surveillance or treatment.

Beyond estrogen’s influence, a growing body of research is uncovering additional risk contributors. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), metabolic syndrome, or diabetes face elevated risk of developing endometrial cancer. Genetic syndromes, particularly Lynch and Cowden syndromes, are associated with significantly increased lifetime risks of endometrial cancer. Environmental exposures, such as the use of hair relaxers, are being investigated as emerging risk factors. Additionally, race remains a risk marker, with Black women not only experiencing higher mortality but also more aggressive subtypes of the disease. These complex, overlapping risks highlight the importance of individualized risk assessment and early intervention strategies.

3. Postmenopausal bleeding is the hallmark symptom — but not the only one.

In endometrial cancer, the majority of cases are diagnosed at an early stage, largely because of the hallmark symptom of postmenopausal bleeding. In addition to bleeding, patients may present with vaginal discharge, pyometra, and even pain and abdominal distension in advanced disease. Any bleeding in a postmenopausal woman should prompt evaluation, as it may signal endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma. In premenopausal women, irregular or heavy menstrual bleeding may raise suspicion, particularly when accompanied by risk factors such as PCOS.

The diagnostic workup for suspected endometrial cancer in women, particularly those presenting with postmenopausal bleeding, begins with a focused clinical assessment and frequently includes transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) to evaluate the endometrium. While TVUS can aid in identifying structural abnormalities or suggest malignancy, endometrial sampling is warranted in all postmenopausal women with abnormal bleeding, regardless of endometrial thickness. Office-based biopsy is the preferred initial approach due to its convenience and diagnostic yield; however, if the sample is nondiagnostic or technically difficult to obtain, hysteroscopy with directed biopsy or dilation and curettage should be pursued.

4. Classification systems are evolving to include molecular subtypes.

Historically, endometrial cancers were classified using the World Health Organization system based on histology and by hormone dependence: Type 1 (estrogen-dependent, typically endometrioid and low grade) and Type 2 (non-estrogen dependent, often serous and high grade). Type 1 cancers tend to have a better prognosis and slower progression, while Type 2 cancers are more aggressive and require intensive treatment. While helpful, this binary classification does not fully capture the biological diversity or treatment responsiveness of the disease.

The field is now moving toward molecular classification, which offers a more nuanced understanding. The four main molecular subtypes include: polymerase epsilon (POLE)-mutant, mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient, p53-abnormal, and no specific molecular profile (NSMP). These groups differ in prognosis and therapeutic implications. POLE-mutant tumors with extremely high mutational burdens generally have excellent outcomes and may not require aggressive adjuvant therapy. In contrast, p53-abnormal tumors are associated with chromosomal instability, TP53 mutations, and poor outcomes, necessitating more aggressive multimodal treatment. MMR-deficient tumors are particularly responsive to immunotherapy. These molecular distinctions are changing how clinicians approach risk stratification and management in patients with endometrial cancer.

5. Treatment is increasingly personalized — and immunotherapy is expanding.

The cornerstone of treatment for early-stage endometrial cancer is surgical: total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, often with sentinel node mapping or lymphadenectomy. Adjuvant therapy depends on factors such as stage, grade, histology, and molecular subtype. Fertility-sparing management with progestin therapy is an option for highly selected patients with early-stage, low-grade tumors. Clinical guidelines recommend that fertility desires be addressed prior to initiating treatment, as standard surgical management typically results in loss of reproductive capacity.

For advanced or recurrent disease, treatment becomes more complex and increasingly individualized. Chemotherapy, often with carboplatin and paclitaxel, is standard for stage III/IV and recurrent disease. Molecular findings now guide additional therapy: For instance, MMR-deficient tumors may respond to checkpoint inhibitors. As targeted agents and combination regimens continue to emerge, treatment of endometrial is increasingly focused on precision medicine.

Markman is professor of medical oncology and therapeutics research and President of Medicine & Science at City of Hope in Atlanta and Chicago. He has disclosed relevant financial relationships with AstraZeneca, GSK and Myriad.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Cancer Patient’s Bittersweet Reminder

Recently, a 40-year-old woman took to Facebook to announce that she had died.

Rachel Davies, of Wales, wrote: “If you’re reading this, then it means I’m no longer here. What a life I’ve had, and surprisingly, since cancer entered my life. When I look through my photos, I’ve done and seen so much since cancer, and probably some of my best memories are from this period. In so many ways, I have to thank it for learning how to live fully. What I wish is that everyone can experience the same but without needing cancer. Get out there, experience life fully, and wear that dress!!! I’m so sad to leave my family and friends, I wish I never had to go. I’m so grateful to have had Charlie young so that I’ve watched him grow into the man he is today. I’m unbelievably proud of him. I am thankful I had the opportunity to have Kacey and Jacob in my life. Lastly, I was blessed to meet the love of my life, my husband, and my best friend. I have no regrets, I have had a wonderful life. So to all of you, don’t be sad I’ve gone. Live your life and live it well. Love, Rachel x.”

I didn’t know Ms. Davies, but am likely among many who wish I had. In a terrible situation she kept trying.

She had HER2 metastatic breast cancer, which can respond to the drug Enhertu (trastuzumab). Unfortunately, she never had the chance, because it wasn’t available to her in Wales. In the United Kingdom it’s available only in Scotland.

I’m not saying it was a cure. Statistically, it likely would have bought her another 6 months of family time. But that’s still another half year.

I’m not blaming the Welsh NHS, though they made the decision not to cover it because of cost. The jobs of such committees is a thankless one, trying to decide where the limited money goes — vaccines for many children that are proven to lessen morbidity and mortality over the course of a lifetime, or to add 6 months to the lives of comparatively fewer women with HER2 metastatic breast cancer.

I’m not blaming the company that makes Enhertu, though it was the cost that kept her from getting it. Bringing a drug to market, with all the labs and clinical research behind it, ain’t cheap. If the company can’t keep the lights on they’re not going to able to develop future pharmaceuticals to help others, though I do wonder if a better price could have been negotiated. (I’m not trying to justify the salaries of insurance CEOs — don’t even get me started on those.)

Money is always limited, and human suffering is infinite. Every health care organization, public or private, has to face that simple fact. There is no right place to draw the line, so we use the greatest good for the greatest many as our best guess.

In her last post, though, Ms. Davies didn’t dwell on any of this. She reflected on her joys and blessings, and encouraged others to live life fully. Things we should all focus on.

Thank you, Ms. Davies, for the reminder.

Allan M. Block, MD, has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Recently, a 40-year-old woman took to Facebook to announce that she had died.

Rachel Davies, of Wales, wrote: “If you’re reading this, then it means I’m no longer here. What a life I’ve had, and surprisingly, since cancer entered my life. When I look through my photos, I’ve done and seen so much since cancer, and probably some of my best memories are from this period. In so many ways, I have to thank it for learning how to live fully. What I wish is that everyone can experience the same but without needing cancer. Get out there, experience life fully, and wear that dress!!! I’m so sad to leave my family and friends, I wish I never had to go. I’m so grateful to have had Charlie young so that I’ve watched him grow into the man he is today. I’m unbelievably proud of him. I am thankful I had the opportunity to have Kacey and Jacob in my life. Lastly, I was blessed to meet the love of my life, my husband, and my best friend. I have no regrets, I have had a wonderful life. So to all of you, don’t be sad I’ve gone. Live your life and live it well. Love, Rachel x.”

I didn’t know Ms. Davies, but am likely among many who wish I had. In a terrible situation she kept trying.

She had HER2 metastatic breast cancer, which can respond to the drug Enhertu (trastuzumab). Unfortunately, she never had the chance, because it wasn’t available to her in Wales. In the United Kingdom it’s available only in Scotland.

I’m not saying it was a cure. Statistically, it likely would have bought her another 6 months of family time. But that’s still another half year.

I’m not blaming the Welsh NHS, though they made the decision not to cover it because of cost. The jobs of such committees is a thankless one, trying to decide where the limited money goes — vaccines for many children that are proven to lessen morbidity and mortality over the course of a lifetime, or to add 6 months to the lives of comparatively fewer women with HER2 metastatic breast cancer.

I’m not blaming the company that makes Enhertu, though it was the cost that kept her from getting it. Bringing a drug to market, with all the labs and clinical research behind it, ain’t cheap. If the company can’t keep the lights on they’re not going to able to develop future pharmaceuticals to help others, though I do wonder if a better price could have been negotiated. (I’m not trying to justify the salaries of insurance CEOs — don’t even get me started on those.)

Money is always limited, and human suffering is infinite. Every health care organization, public or private, has to face that simple fact. There is no right place to draw the line, so we use the greatest good for the greatest many as our best guess.

In her last post, though, Ms. Davies didn’t dwell on any of this. She reflected on her joys and blessings, and encouraged others to live life fully. Things we should all focus on.

Thank you, Ms. Davies, for the reminder.

Allan M. Block, MD, has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Recently, a 40-year-old woman took to Facebook to announce that she had died.

Rachel Davies, of Wales, wrote: “If you’re reading this, then it means I’m no longer here. What a life I’ve had, and surprisingly, since cancer entered my life. When I look through my photos, I’ve done and seen so much since cancer, and probably some of my best memories are from this period. In so many ways, I have to thank it for learning how to live fully. What I wish is that everyone can experience the same but without needing cancer. Get out there, experience life fully, and wear that dress!!! I’m so sad to leave my family and friends, I wish I never had to go. I’m so grateful to have had Charlie young so that I’ve watched him grow into the man he is today. I’m unbelievably proud of him. I am thankful I had the opportunity to have Kacey and Jacob in my life. Lastly, I was blessed to meet the love of my life, my husband, and my best friend. I have no regrets, I have had a wonderful life. So to all of you, don’t be sad I’ve gone. Live your life and live it well. Love, Rachel x.”

I didn’t know Ms. Davies, but am likely among many who wish I had. In a terrible situation she kept trying.

She had HER2 metastatic breast cancer, which can respond to the drug Enhertu (trastuzumab). Unfortunately, she never had the chance, because it wasn’t available to her in Wales. In the United Kingdom it’s available only in Scotland.

I’m not saying it was a cure. Statistically, it likely would have bought her another 6 months of family time. But that’s still another half year.

I’m not blaming the Welsh NHS, though they made the decision not to cover it because of cost. The jobs of such committees is a thankless one, trying to decide where the limited money goes — vaccines for many children that are proven to lessen morbidity and mortality over the course of a lifetime, or to add 6 months to the lives of comparatively fewer women with HER2 metastatic breast cancer.

I’m not blaming the company that makes Enhertu, though it was the cost that kept her from getting it. Bringing a drug to market, with all the labs and clinical research behind it, ain’t cheap. If the company can’t keep the lights on they’re not going to able to develop future pharmaceuticals to help others, though I do wonder if a better price could have been negotiated. (I’m not trying to justify the salaries of insurance CEOs — don’t even get me started on those.)

Money is always limited, and human suffering is infinite. Every health care organization, public or private, has to face that simple fact. There is no right place to draw the line, so we use the greatest good for the greatest many as our best guess.

In her last post, though, Ms. Davies didn’t dwell on any of this. She reflected on her joys and blessings, and encouraged others to live life fully. Things we should all focus on.

Thank you, Ms. Davies, for the reminder.

Allan M. Block, MD, has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Have Your Cake and Eat It, Too: Findings Based on Ingredients in Christmas Desserts From The Great British Bake Off

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hello. I’m David Kerr, professor of cancer medicine at University of Oxford. As I become, sadly, older, I’ve become much more interested in the concept of cancer prevention than cancer treatment. Of course, I’m still a practicing cancer physician and researcher. That’s my daily bread and butter. But prevention is important.

There’s a really interesting article in the Christmas edition of The BMJ. This is an opportunity for us to take good science, but lighthearted science, to titillate and amuse our Christmas readers. This is a nice article from the States led by Joshua Wallach. As I say, this brings together good science in a sometimes absurd setting. I’ll read its title: “Association of Health Benefits and Harms of Christmas Dessert Ingredients in Recipes From The Great British Bake Off: Umbrella Review of Umbrella Reviews of Meta-analyses of Observational Studies.”

It’s obviously a very strong statistical underpinning from this group from Yale, predominantly — a half-decent university, as those of us from Oxford would have to admit. They used The Great British Bake Off website, Embase, Medline, and Scopus. They looked at the whole host of umbrella reviews and so on.

They were interested in looking at the relative balance of dangerous and protective ingredients that were recommended in Christmas desserts on this immensely popular television show called The Great British Bake Off. Some of you have watched it and have enjoyed watching the trials and tribulations of the various contestants.

They looked at 48 recipes for Christmas desserts, including cakes, biscuits, pastries, puddings, and conventional desserts. Of all these, there were 178 unique ingredients. Literature research then parsed whether these ingredients were good for you or bad for you.

It was very interesting that, when they put the summary together, the umbrella review of umbrella reviews of meta-analyses compressed together, it was good news for us all. Recipes for Christmas desserts, particularly from The Great British Bake Off — which should be enormously proud of this — tend to use ingredient groups that are associated with reductions rather than increases in the risk for disease. Hurrah!

This means that, clearly, Christmas is a time in which those of us who can, tend to overindulge in food. The granddad falling asleep with a full tummy, sitting with the family in front of a hot fire — all of us can remember and imagine all of that.

Perhaps the most important takeaway point from this observationally, critically important study is that, yes — at Christmas time, enjoy the dessert. You can have your cake and eat it, too. You heard it here. It’s philosophically true and statistically proven: You can have your cake and eat it.

Thanks for listening. I’d be very interested in your own recipes, and whether we think that the American Thanksgiving desserts correlate with British Christmas desserts in some way and are beneficial to your health.

Have a look at this article that is cleverly, wittily written. As always, Medscapers, for the time being, thanks for listening. Over and out.

Dr Kerr, Professor, Nuffield Department of Clinical Laboratory Science, University of Oxford; Professor of Cancer Medicine, Oxford Cancer Centre, Oxford, United Kingdom, has disclosed ties with Celleron Therapeutics, Oxford Cancer Biomarkers (Board of Directors); Afrox (charity; Trustee); GlaxoSmithKline and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals (Consultant); Genomic Health; Merck Serono, Roche.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hello. I’m David Kerr, professor of cancer medicine at University of Oxford. As I become, sadly, older, I’ve become much more interested in the concept of cancer prevention than cancer treatment. Of course, I’m still a practicing cancer physician and researcher. That’s my daily bread and butter. But prevention is important.

There’s a really interesting article in the Christmas edition of The BMJ. This is an opportunity for us to take good science, but lighthearted science, to titillate and amuse our Christmas readers. This is a nice article from the States led by Joshua Wallach. As I say, this brings together good science in a sometimes absurd setting. I’ll read its title: “Association of Health Benefits and Harms of Christmas Dessert Ingredients in Recipes From The Great British Bake Off: Umbrella Review of Umbrella Reviews of Meta-analyses of Observational Studies.”

It’s obviously a very strong statistical underpinning from this group from Yale, predominantly — a half-decent university, as those of us from Oxford would have to admit. They used The Great British Bake Off website, Embase, Medline, and Scopus. They looked at the whole host of umbrella reviews and so on.

They were interested in looking at the relative balance of dangerous and protective ingredients that were recommended in Christmas desserts on this immensely popular television show called The Great British Bake Off. Some of you have watched it and have enjoyed watching the trials and tribulations of the various contestants.

They looked at 48 recipes for Christmas desserts, including cakes, biscuits, pastries, puddings, and conventional desserts. Of all these, there were 178 unique ingredients. Literature research then parsed whether these ingredients were good for you or bad for you.

It was very interesting that, when they put the summary together, the umbrella review of umbrella reviews of meta-analyses compressed together, it was good news for us all. Recipes for Christmas desserts, particularly from The Great British Bake Off — which should be enormously proud of this — tend to use ingredient groups that are associated with reductions rather than increases in the risk for disease. Hurrah!

This means that, clearly, Christmas is a time in which those of us who can, tend to overindulge in food. The granddad falling asleep with a full tummy, sitting with the family in front of a hot fire — all of us can remember and imagine all of that.

Perhaps the most important takeaway point from this observationally, critically important study is that, yes — at Christmas time, enjoy the dessert. You can have your cake and eat it, too. You heard it here. It’s philosophically true and statistically proven: You can have your cake and eat it.

Thanks for listening. I’d be very interested in your own recipes, and whether we think that the American Thanksgiving desserts correlate with British Christmas desserts in some way and are beneficial to your health.

Have a look at this article that is cleverly, wittily written. As always, Medscapers, for the time being, thanks for listening. Over and out.

Dr Kerr, Professor, Nuffield Department of Clinical Laboratory Science, University of Oxford; Professor of Cancer Medicine, Oxford Cancer Centre, Oxford, United Kingdom, has disclosed ties with Celleron Therapeutics, Oxford Cancer Biomarkers (Board of Directors); Afrox (charity; Trustee); GlaxoSmithKline and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals (Consultant); Genomic Health; Merck Serono, Roche.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hello. I’m David Kerr, professor of cancer medicine at University of Oxford. As I become, sadly, older, I’ve become much more interested in the concept of cancer prevention than cancer treatment. Of course, I’m still a practicing cancer physician and researcher. That’s my daily bread and butter. But prevention is important.

There’s a really interesting article in the Christmas edition of The BMJ. This is an opportunity for us to take good science, but lighthearted science, to titillate and amuse our Christmas readers. This is a nice article from the States led by Joshua Wallach. As I say, this brings together good science in a sometimes absurd setting. I’ll read its title: “Association of Health Benefits and Harms of Christmas Dessert Ingredients in Recipes From The Great British Bake Off: Umbrella Review of Umbrella Reviews of Meta-analyses of Observational Studies.”

It’s obviously a very strong statistical underpinning from this group from Yale, predominantly — a half-decent university, as those of us from Oxford would have to admit. They used The Great British Bake Off website, Embase, Medline, and Scopus. They looked at the whole host of umbrella reviews and so on.

They were interested in looking at the relative balance of dangerous and protective ingredients that were recommended in Christmas desserts on this immensely popular television show called The Great British Bake Off. Some of you have watched it and have enjoyed watching the trials and tribulations of the various contestants.

They looked at 48 recipes for Christmas desserts, including cakes, biscuits, pastries, puddings, and conventional desserts. Of all these, there were 178 unique ingredients. Literature research then parsed whether these ingredients were good for you or bad for you.

It was very interesting that, when they put the summary together, the umbrella review of umbrella reviews of meta-analyses compressed together, it was good news for us all. Recipes for Christmas desserts, particularly from The Great British Bake Off — which should be enormously proud of this — tend to use ingredient groups that are associated with reductions rather than increases in the risk for disease. Hurrah!

This means that, clearly, Christmas is a time in which those of us who can, tend to overindulge in food. The granddad falling asleep with a full tummy, sitting with the family in front of a hot fire — all of us can remember and imagine all of that.

Perhaps the most important takeaway point from this observationally, critically important study is that, yes — at Christmas time, enjoy the dessert. You can have your cake and eat it, too. You heard it here. It’s philosophically true and statistically proven: You can have your cake and eat it.

Thanks for listening. I’d be very interested in your own recipes, and whether we think that the American Thanksgiving desserts correlate with British Christmas desserts in some way and are beneficial to your health.

Have a look at this article that is cleverly, wittily written. As always, Medscapers, for the time being, thanks for listening. Over and out.