User login

Acute Multiple Flexor Tendon Injury and Carpal Tunnel Syndrome After Open Distal Radius Fracture

The literature on extensor tendon rupture and even chronic flexor tendon rupture after volar plating and distal radius fracture malunion is ubiquitous. However, acute and subacute flexor tendon ruptures caused by distal radius fractures have been reported only in limited case reports. These rare injuries may involve multiple tendons and are associated with high-energy mechanisms. This case report details the involvement of multiple flexor tendon injuries associated with a Gustilo-Anderson type II distal radius fracture and the development of acute carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) after a motor vehicle collision. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

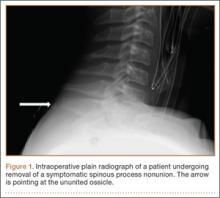

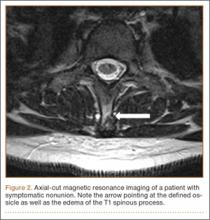

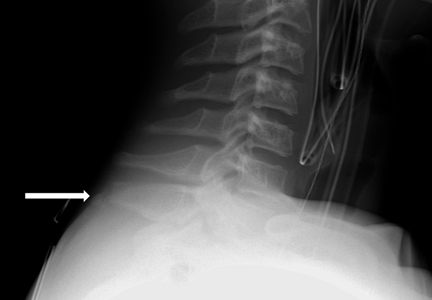

The patient is a 46-year-old woman who was involved in a motor vehicle collision. She was triaged as a trauma patient via Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol, and treated with antibiotic and tetanus prophylaxis. Radiographs showed an open, comminuted, displaced intra-articular distal radius fracture on the right side (Figures 1A, 1B). The fracture was closed reduced and splinted in the emergency department (Figures 2A, 2B). On initial examination, the patient had diffuse paresthesias in the digits that were most pronounced in the median nerve distribution. Motor examination was limited secondary to pain; however, she demonstrated gentle flexion and extension of the digits. The hand was well perfused, and a palpable radial pulse was present.

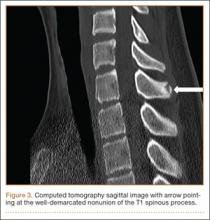

After clearance was obtained, she was taken urgently to the operating room. The wound was volar and transverse, approximately 2 cm in length, and approximately 4 cm proximal to the wrist crease. The wound was extended proximally and distally for a standard volar (Henry) approach. The flexor carpi radialis tendon was found to be partially lacerated, comprising 60% of the tendon. The fracture was readily identified because the deep fascia and the pronator quadratus were disrupted. No deep tendon lacerations were identified. The median nerve was found to be in continuity. After satisfactory débridement of the fracture and the wound, reduction and fixation was achieved with a volar locking plate and a single Kirschner wire. The flexor carpi radialis tendon was repaired with a modified Kessler stitch and epitenon repair. The wound was closed primarily in layers (Figures 3A, 3B).

The patient’s immediate postoperative neurologic examination was compromised secondary to the patient having a supraclavicular nerve block for anesthesia. Regional anesthesia was chosen because the patient’s pulmonologist recommended avoiding general anesthesia owing to her history of severe asthma that frequently required corticosteroid treatment. Once the block wore off, she complained of persistent paresthesias in all digits but most pronounced in the median nerve distribution. She was able to flex the interphalangeal joint to the index finger but could not flex the interphalangeal joint to the thumb. Over the course of the night, she was also noted to have worsening pain out of proportion to her injury.

As the paresthesias became denser in the median nerve distribution, she was diagnosed with acute CTS and was taken urgently back to the operating room under general anesthesia. After releasing the carpal tunnel through a separate incision, the original wound was reopened and explored. The median nerve was again visualized and found to be in continuity. All 4 tendons to both the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus were identified. The flexor pollicis longus (FPL) was not visualized in the wound. The distal portion of the FPL was retracted in the thumb tendon sheath and retrieved blindly with a tendon passer. The proximal portion was retracted to the mid-forearm. The laceration occurred distal to the musculotendinous junction. The tendon was repaired with a modified Kessler stitch as well as a box suture, resulting in 4 core strands across the tendon. The hand and the wrist were splinted in a thumb spica cast, and the patient was started on a modified Duran protocol 1 week after surgery. Median nerve function improved postoperatively.

Discussion

The rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon in nondisplaced distal radius fractures is not uncommon, but occurs in fewer than 5% of nondisplaced distal radius fractures.1 Although less common, chronic complications with flexor tendon rupture after distal radius fracture are well described.1-6 Flexor tendon rupture after distal radius malunion or volar plating is a known complication and is thought to be the result of attritional tendon wear because the flexors rub against protruding bone or plate;3,4,7 however, the initial tendon injury may play a role in those tendons that rupture more quickly.3 When secondary to volar plating, the rupture typically occurs within 1 year of injury,7 but, in both plating and malunion, it has been characterized as a late complication up to 10 years and even 20 years after injury.3,4 Similar to other reports, this rupture was encountered during a volar wrist approach. It has been suggested that, as the incidence of volar plating rises, more acute flexor tendon injuries may be diagnosed because of anatomic exposure,2 but this has not been reported in the literature.

Acute and subacute flexor tendon ruptures are rarely reported in the literature. To our knowledge, there are only 2 other reports of acute flexor tendon rupture2,5 after a distal radius fracture, neither of which involved the FPL. These cases, which involved ruptures of the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor carpi radialis, were thought to be the result of tendon laceration by a volar bone spike. There is also one report of subacute FPL and flexor digitorum profundus rupture approximately 4 weeks after closed reduction of a distal radius fracture.6 Although sparse, the literature regarding flexor tendon rupture and distal radius fractures suggests that involvement of the flexor digitorum superficialis and the flexor digitorum profundus tendons is most common and that the rupture typically occurs in 1 to 4 months.1

We report a rare case of 2 acute flexor tendon lacerations after a Gustilo-Anderson type II open distal radius fracture, likely caused by the volar spike of bone that created the open injury. This case also was complicated by the development of acute CTS.

To our knowledge, despite a rate of acute CTS reported as high as 5.4% in operatively treated distal radius fractures, there are no established associations between acute CTS and flexor tendon rupture in the setting of distal radius fracture.8,9 In a 2008 retrospective case–control study by Dyer and colleagues,8 fracture translation is the most important risk factor for the development of acute CTS associated with fracture of the distal radius. Although not statistically significant, ipsilateral upper extremity trauma, higher-energy injuries, younger age, and male sex were also associated with the development of acute CTS. Open injuries occurred in only 3 of 50 cases of acute CTS.8

In agreement with published reports, the probability and the timing of tendon rupture are likely related to the severity of the deforming forces applied during the initial insult rather than the resultant stresses.1 Clinicians should have a high suspicion of acute CTS and possible tendon injuries after a high-energy injury with a significantly displaced open distal radius fracture and median nerve paresthesias. A thoughtful and complete preoperative examination of the flexor tendons may prevent the need for reoperation. Concerns for flexor injury and acute CTS should be elevated with the observation of a disrupted pronator. For patients with a volarly displaced fragment after fracture reduction, this concern should be even more elevated.9 Preoperative median nerve symptoms in the setting of the severely displaced fracture should necessitate an acute carpal tunnel release. If 1 flexor tendon is injured, the surgeon should remember that multiple flexor tendons may be involved. We recommend that any injured tendons be repaired primarily, if possible, and the patient started on appropriate rehabilitation.

1. Ashall G. Flexor pollicis longus rupture after fracture of the distal radius. Injury. 1991;22(2):153-155.

2. Dimatteo L, Wolf JM. Flexor carpi radialis tendon rupture as a complication of a closed distal radius fracture: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(6):818-820.

3. Kato N, Nemoto K, Arino H, Ichikawa T, Fujikawa K. Ruptures of flexor tendons at the wrist as a complication of fracture of the distal radius. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2002;36(4):245-248.

4. Monda MK, Ellis A, Karmani S. Late rupture of flexor pollicis longus tendon 10 years after volar buttress plate fixation of a distal radius fracture: a case report. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(4):549-551.

5. Southmayd WW, Millender LH, Nalebuff EA. Rupture of the flexor tendons of the index finger after Colles’ fracture. Case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(4):562-563.

6. Wong FY, Pho RW. Median nerve compression, with tendon ruptures, after Colles’ fracture. J Hand Surg Br. 1984;9(2):139-141.

7. Woon CYL, Lee JYL, Ng SW, Teoh LC. Late rupture of flexor pollicis longus tendon after volar distal radius plating: a case report and review of the literature. Inj Extra. 2007;38(7):235-238.

8. Dyer G, Lozano-Calderon S, Gannon C, Baratz M, Ring D. Predictors of acute carpal tunnel syndrome associated with fracture of the distal radius. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(8):1309-1313.

9. Paley D, McMurtry RY. Median nerve compression by volarly displaced fragments of the distal radius. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(215):139-147.

The literature on extensor tendon rupture and even chronic flexor tendon rupture after volar plating and distal radius fracture malunion is ubiquitous. However, acute and subacute flexor tendon ruptures caused by distal radius fractures have been reported only in limited case reports. These rare injuries may involve multiple tendons and are associated with high-energy mechanisms. This case report details the involvement of multiple flexor tendon injuries associated with a Gustilo-Anderson type II distal radius fracture and the development of acute carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) after a motor vehicle collision. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

The patient is a 46-year-old woman who was involved in a motor vehicle collision. She was triaged as a trauma patient via Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol, and treated with antibiotic and tetanus prophylaxis. Radiographs showed an open, comminuted, displaced intra-articular distal radius fracture on the right side (Figures 1A, 1B). The fracture was closed reduced and splinted in the emergency department (Figures 2A, 2B). On initial examination, the patient had diffuse paresthesias in the digits that were most pronounced in the median nerve distribution. Motor examination was limited secondary to pain; however, she demonstrated gentle flexion and extension of the digits. The hand was well perfused, and a palpable radial pulse was present.

After clearance was obtained, she was taken urgently to the operating room. The wound was volar and transverse, approximately 2 cm in length, and approximately 4 cm proximal to the wrist crease. The wound was extended proximally and distally for a standard volar (Henry) approach. The flexor carpi radialis tendon was found to be partially lacerated, comprising 60% of the tendon. The fracture was readily identified because the deep fascia and the pronator quadratus were disrupted. No deep tendon lacerations were identified. The median nerve was found to be in continuity. After satisfactory débridement of the fracture and the wound, reduction and fixation was achieved with a volar locking plate and a single Kirschner wire. The flexor carpi radialis tendon was repaired with a modified Kessler stitch and epitenon repair. The wound was closed primarily in layers (Figures 3A, 3B).

The patient’s immediate postoperative neurologic examination was compromised secondary to the patient having a supraclavicular nerve block for anesthesia. Regional anesthesia was chosen because the patient’s pulmonologist recommended avoiding general anesthesia owing to her history of severe asthma that frequently required corticosteroid treatment. Once the block wore off, she complained of persistent paresthesias in all digits but most pronounced in the median nerve distribution. She was able to flex the interphalangeal joint to the index finger but could not flex the interphalangeal joint to the thumb. Over the course of the night, she was also noted to have worsening pain out of proportion to her injury.

As the paresthesias became denser in the median nerve distribution, she was diagnosed with acute CTS and was taken urgently back to the operating room under general anesthesia. After releasing the carpal tunnel through a separate incision, the original wound was reopened and explored. The median nerve was again visualized and found to be in continuity. All 4 tendons to both the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus were identified. The flexor pollicis longus (FPL) was not visualized in the wound. The distal portion of the FPL was retracted in the thumb tendon sheath and retrieved blindly with a tendon passer. The proximal portion was retracted to the mid-forearm. The laceration occurred distal to the musculotendinous junction. The tendon was repaired with a modified Kessler stitch as well as a box suture, resulting in 4 core strands across the tendon. The hand and the wrist were splinted in a thumb spica cast, and the patient was started on a modified Duran protocol 1 week after surgery. Median nerve function improved postoperatively.

Discussion

The rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon in nondisplaced distal radius fractures is not uncommon, but occurs in fewer than 5% of nondisplaced distal radius fractures.1 Although less common, chronic complications with flexor tendon rupture after distal radius fracture are well described.1-6 Flexor tendon rupture after distal radius malunion or volar plating is a known complication and is thought to be the result of attritional tendon wear because the flexors rub against protruding bone or plate;3,4,7 however, the initial tendon injury may play a role in those tendons that rupture more quickly.3 When secondary to volar plating, the rupture typically occurs within 1 year of injury,7 but, in both plating and malunion, it has been characterized as a late complication up to 10 years and even 20 years after injury.3,4 Similar to other reports, this rupture was encountered during a volar wrist approach. It has been suggested that, as the incidence of volar plating rises, more acute flexor tendon injuries may be diagnosed because of anatomic exposure,2 but this has not been reported in the literature.

Acute and subacute flexor tendon ruptures are rarely reported in the literature. To our knowledge, there are only 2 other reports of acute flexor tendon rupture2,5 after a distal radius fracture, neither of which involved the FPL. These cases, which involved ruptures of the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor carpi radialis, were thought to be the result of tendon laceration by a volar bone spike. There is also one report of subacute FPL and flexor digitorum profundus rupture approximately 4 weeks after closed reduction of a distal radius fracture.6 Although sparse, the literature regarding flexor tendon rupture and distal radius fractures suggests that involvement of the flexor digitorum superficialis and the flexor digitorum profundus tendons is most common and that the rupture typically occurs in 1 to 4 months.1

We report a rare case of 2 acute flexor tendon lacerations after a Gustilo-Anderson type II open distal radius fracture, likely caused by the volar spike of bone that created the open injury. This case also was complicated by the development of acute CTS.

To our knowledge, despite a rate of acute CTS reported as high as 5.4% in operatively treated distal radius fractures, there are no established associations between acute CTS and flexor tendon rupture in the setting of distal radius fracture.8,9 In a 2008 retrospective case–control study by Dyer and colleagues,8 fracture translation is the most important risk factor for the development of acute CTS associated with fracture of the distal radius. Although not statistically significant, ipsilateral upper extremity trauma, higher-energy injuries, younger age, and male sex were also associated with the development of acute CTS. Open injuries occurred in only 3 of 50 cases of acute CTS.8

In agreement with published reports, the probability and the timing of tendon rupture are likely related to the severity of the deforming forces applied during the initial insult rather than the resultant stresses.1 Clinicians should have a high suspicion of acute CTS and possible tendon injuries after a high-energy injury with a significantly displaced open distal radius fracture and median nerve paresthesias. A thoughtful and complete preoperative examination of the flexor tendons may prevent the need for reoperation. Concerns for flexor injury and acute CTS should be elevated with the observation of a disrupted pronator. For patients with a volarly displaced fragment after fracture reduction, this concern should be even more elevated.9 Preoperative median nerve symptoms in the setting of the severely displaced fracture should necessitate an acute carpal tunnel release. If 1 flexor tendon is injured, the surgeon should remember that multiple flexor tendons may be involved. We recommend that any injured tendons be repaired primarily, if possible, and the patient started on appropriate rehabilitation.

The literature on extensor tendon rupture and even chronic flexor tendon rupture after volar plating and distal radius fracture malunion is ubiquitous. However, acute and subacute flexor tendon ruptures caused by distal radius fractures have been reported only in limited case reports. These rare injuries may involve multiple tendons and are associated with high-energy mechanisms. This case report details the involvement of multiple flexor tendon injuries associated with a Gustilo-Anderson type II distal radius fracture and the development of acute carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) after a motor vehicle collision. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

The patient is a 46-year-old woman who was involved in a motor vehicle collision. She was triaged as a trauma patient via Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol, and treated with antibiotic and tetanus prophylaxis. Radiographs showed an open, comminuted, displaced intra-articular distal radius fracture on the right side (Figures 1A, 1B). The fracture was closed reduced and splinted in the emergency department (Figures 2A, 2B). On initial examination, the patient had diffuse paresthesias in the digits that were most pronounced in the median nerve distribution. Motor examination was limited secondary to pain; however, she demonstrated gentle flexion and extension of the digits. The hand was well perfused, and a palpable radial pulse was present.

After clearance was obtained, she was taken urgently to the operating room. The wound was volar and transverse, approximately 2 cm in length, and approximately 4 cm proximal to the wrist crease. The wound was extended proximally and distally for a standard volar (Henry) approach. The flexor carpi radialis tendon was found to be partially lacerated, comprising 60% of the tendon. The fracture was readily identified because the deep fascia and the pronator quadratus were disrupted. No deep tendon lacerations were identified. The median nerve was found to be in continuity. After satisfactory débridement of the fracture and the wound, reduction and fixation was achieved with a volar locking plate and a single Kirschner wire. The flexor carpi radialis tendon was repaired with a modified Kessler stitch and epitenon repair. The wound was closed primarily in layers (Figures 3A, 3B).

The patient’s immediate postoperative neurologic examination was compromised secondary to the patient having a supraclavicular nerve block for anesthesia. Regional anesthesia was chosen because the patient’s pulmonologist recommended avoiding general anesthesia owing to her history of severe asthma that frequently required corticosteroid treatment. Once the block wore off, she complained of persistent paresthesias in all digits but most pronounced in the median nerve distribution. She was able to flex the interphalangeal joint to the index finger but could not flex the interphalangeal joint to the thumb. Over the course of the night, she was also noted to have worsening pain out of proportion to her injury.

As the paresthesias became denser in the median nerve distribution, she was diagnosed with acute CTS and was taken urgently back to the operating room under general anesthesia. After releasing the carpal tunnel through a separate incision, the original wound was reopened and explored. The median nerve was again visualized and found to be in continuity. All 4 tendons to both the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus were identified. The flexor pollicis longus (FPL) was not visualized in the wound. The distal portion of the FPL was retracted in the thumb tendon sheath and retrieved blindly with a tendon passer. The proximal portion was retracted to the mid-forearm. The laceration occurred distal to the musculotendinous junction. The tendon was repaired with a modified Kessler stitch as well as a box suture, resulting in 4 core strands across the tendon. The hand and the wrist were splinted in a thumb spica cast, and the patient was started on a modified Duran protocol 1 week after surgery. Median nerve function improved postoperatively.

Discussion

The rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon in nondisplaced distal radius fractures is not uncommon, but occurs in fewer than 5% of nondisplaced distal radius fractures.1 Although less common, chronic complications with flexor tendon rupture after distal radius fracture are well described.1-6 Flexor tendon rupture after distal radius malunion or volar plating is a known complication and is thought to be the result of attritional tendon wear because the flexors rub against protruding bone or plate;3,4,7 however, the initial tendon injury may play a role in those tendons that rupture more quickly.3 When secondary to volar plating, the rupture typically occurs within 1 year of injury,7 but, in both plating and malunion, it has been characterized as a late complication up to 10 years and even 20 years after injury.3,4 Similar to other reports, this rupture was encountered during a volar wrist approach. It has been suggested that, as the incidence of volar plating rises, more acute flexor tendon injuries may be diagnosed because of anatomic exposure,2 but this has not been reported in the literature.

Acute and subacute flexor tendon ruptures are rarely reported in the literature. To our knowledge, there are only 2 other reports of acute flexor tendon rupture2,5 after a distal radius fracture, neither of which involved the FPL. These cases, which involved ruptures of the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor carpi radialis, were thought to be the result of tendon laceration by a volar bone spike. There is also one report of subacute FPL and flexor digitorum profundus rupture approximately 4 weeks after closed reduction of a distal radius fracture.6 Although sparse, the literature regarding flexor tendon rupture and distal radius fractures suggests that involvement of the flexor digitorum superficialis and the flexor digitorum profundus tendons is most common and that the rupture typically occurs in 1 to 4 months.1

We report a rare case of 2 acute flexor tendon lacerations after a Gustilo-Anderson type II open distal radius fracture, likely caused by the volar spike of bone that created the open injury. This case also was complicated by the development of acute CTS.

To our knowledge, despite a rate of acute CTS reported as high as 5.4% in operatively treated distal radius fractures, there are no established associations between acute CTS and flexor tendon rupture in the setting of distal radius fracture.8,9 In a 2008 retrospective case–control study by Dyer and colleagues,8 fracture translation is the most important risk factor for the development of acute CTS associated with fracture of the distal radius. Although not statistically significant, ipsilateral upper extremity trauma, higher-energy injuries, younger age, and male sex were also associated with the development of acute CTS. Open injuries occurred in only 3 of 50 cases of acute CTS.8

In agreement with published reports, the probability and the timing of tendon rupture are likely related to the severity of the deforming forces applied during the initial insult rather than the resultant stresses.1 Clinicians should have a high suspicion of acute CTS and possible tendon injuries after a high-energy injury with a significantly displaced open distal radius fracture and median nerve paresthesias. A thoughtful and complete preoperative examination of the flexor tendons may prevent the need for reoperation. Concerns for flexor injury and acute CTS should be elevated with the observation of a disrupted pronator. For patients with a volarly displaced fragment after fracture reduction, this concern should be even more elevated.9 Preoperative median nerve symptoms in the setting of the severely displaced fracture should necessitate an acute carpal tunnel release. If 1 flexor tendon is injured, the surgeon should remember that multiple flexor tendons may be involved. We recommend that any injured tendons be repaired primarily, if possible, and the patient started on appropriate rehabilitation.

1. Ashall G. Flexor pollicis longus rupture after fracture of the distal radius. Injury. 1991;22(2):153-155.

2. Dimatteo L, Wolf JM. Flexor carpi radialis tendon rupture as a complication of a closed distal radius fracture: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(6):818-820.

3. Kato N, Nemoto K, Arino H, Ichikawa T, Fujikawa K. Ruptures of flexor tendons at the wrist as a complication of fracture of the distal radius. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2002;36(4):245-248.

4. Monda MK, Ellis A, Karmani S. Late rupture of flexor pollicis longus tendon 10 years after volar buttress plate fixation of a distal radius fracture: a case report. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(4):549-551.

5. Southmayd WW, Millender LH, Nalebuff EA. Rupture of the flexor tendons of the index finger after Colles’ fracture. Case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(4):562-563.

6. Wong FY, Pho RW. Median nerve compression, with tendon ruptures, after Colles’ fracture. J Hand Surg Br. 1984;9(2):139-141.

7. Woon CYL, Lee JYL, Ng SW, Teoh LC. Late rupture of flexor pollicis longus tendon after volar distal radius plating: a case report and review of the literature. Inj Extra. 2007;38(7):235-238.

8. Dyer G, Lozano-Calderon S, Gannon C, Baratz M, Ring D. Predictors of acute carpal tunnel syndrome associated with fracture of the distal radius. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(8):1309-1313.

9. Paley D, McMurtry RY. Median nerve compression by volarly displaced fragments of the distal radius. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(215):139-147.

1. Ashall G. Flexor pollicis longus rupture after fracture of the distal radius. Injury. 1991;22(2):153-155.

2. Dimatteo L, Wolf JM. Flexor carpi radialis tendon rupture as a complication of a closed distal radius fracture: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(6):818-820.

3. Kato N, Nemoto K, Arino H, Ichikawa T, Fujikawa K. Ruptures of flexor tendons at the wrist as a complication of fracture of the distal radius. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2002;36(4):245-248.

4. Monda MK, Ellis A, Karmani S. Late rupture of flexor pollicis longus tendon 10 years after volar buttress plate fixation of a distal radius fracture: a case report. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(4):549-551.

5. Southmayd WW, Millender LH, Nalebuff EA. Rupture of the flexor tendons of the index finger after Colles’ fracture. Case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(4):562-563.

6. Wong FY, Pho RW. Median nerve compression, with tendon ruptures, after Colles’ fracture. J Hand Surg Br. 1984;9(2):139-141.

7. Woon CYL, Lee JYL, Ng SW, Teoh LC. Late rupture of flexor pollicis longus tendon after volar distal radius plating: a case report and review of the literature. Inj Extra. 2007;38(7):235-238.

8. Dyer G, Lozano-Calderon S, Gannon C, Baratz M, Ring D. Predictors of acute carpal tunnel syndrome associated with fracture of the distal radius. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(8):1309-1313.

9. Paley D, McMurtry RY. Median nerve compression by volarly displaced fragments of the distal radius. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(215):139-147.

Medicaid Insurance Is Associated With Larger Curves in Patients Who Require Scoliosis Surgery

Rising health care costs have led many health insurers to limit benefits, which may be a problem for children in need of specialty care. Uninsured children have poorer access to specialty care than insured children. Children with public health coverage have better access to specialty care than uninsured children but inferior access compared with privately insured children.1,2 It is well documented that children with government insurance have limited access to orthopedic care for fractures, ligamentous knee injuries, and other injuries.1,3-5 Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) differs from many other conditions managed by pediatric orthopedists, as it may be progressive, with management becoming increasingly more complex as the curve magnitude increases.6 The ability to access care earlier in the disease process may allow for earlier nonoperative interventions, such as bracing. For patients who require spinal fusion, earlier diagnosis and referral to a specialist could potentially result in shorter fusions and preserve distal motion segments. The ability to access the health care system in a timely fashion would therefore be of utmost importance for patients with scoliosis.

The literature on AIS is lacking in studies focused on care access based on insurance coverage and the potential impact that this may have on curve progression.7-9 We conducted a study to determine whether there is a difference between patients with and without private insurance who present to a busy urban pediatric orthopedic practice for management of scoliosis that eventually resulted in surgical treatment.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients (age, 10-18 years) who underwent posterior spinal fusion (PSF) for newly diagnosed AIS between 2008 and 2012. We excluded patients treated with growing spine instrumentation (growing rods), patients younger than 10 years or older than 18 years at presentation, and patients without adequate radiographs or clinical data, including insurance status. To focus on newly diagnosed scoliosis, we also excluded patients who had been seen for second opinions or whose scoliosis had been managed elsewhere in the past. Patients with syndromic, neuromuscular, or congenital scoliosis were also excluded.

Medical records were checked to ascertain time from initial evaluation to decision for surgery, time from recommendation for surgery until actual procedure, and insurance status. Distance traveled was figured from patients’ home addresses. Cobb angles were calculated from initial preoperative and final preoperative posteroanterior (PA) radiographs. Curves as seen on PA, lateral, and maximal effort, supine bending thoracic and lumbar radiographs from the initial preoperative visit were classified using the system of Lenke and colleagues.10 Hospital records were queried to determine number of levels fused at surgery, number of implants placed, and length of stay. Patients were evaluated without prior screening of insurance status and without prior consultation with referring physicians. Surgical procedures were scheduled on a first-come, first-served basis without preference for insurance status.

Results

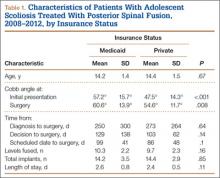

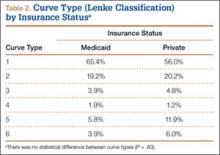

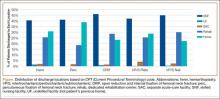

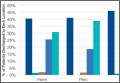

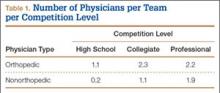

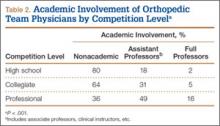

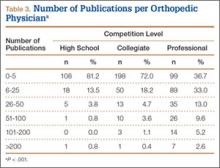

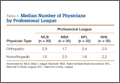

We identified 135 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed AIS treated with PSF by our group between January 2008 and December 2012 (Table 1). Sixty-one percent had private insurance; 39% had Medicaid. There was no difference in age or ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score between groups. Mean (SD) Cobb angle at initial presentation was 47.5° (14.3°) (range, 18.0°-86.0°) for the private insurance group and 57.2° (15.7°) (range, 23.0°-95.0°) for the Medicaid group (P < .0001). At time of surgery, mean (SD) Cobb angles were 54.6° (11.7°) and 60.6° (13.9°) for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively (P = .008). There was no difference in curve types (Lenke and colleagues10 classification) between groups (Table 2, P = .83). Medicaid patients traveled a shorter mean (SD) distance for care, 56.3 (57.0) miles, versus 73.7 (66.7) miles (P = .05). There was no statistical difference (P = .14) in mean (SD) surgical wait time from surgery recommendation to actual surgery, 103.1 (62.4) days and 128.8 (137.5) days for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively. The difference between patient groups in mean (SD) number of levels fused did not reach statistical significance (P = .16), 10.3 (2.2) levels for the Medicaid group and 9.7 (2.3) levels for the private insurance group. Mean (SD) estimated blood loss was higher for Medicaid patients, 445.7 (415.9) mL versus 335.1 (271.5) mL (P = .06), though there was no difference in use of posterior column osteotomies between groups. There was no difference (P = .11) in mean (SD) length of hospital stay between Medicaid patients, 2.6 (0.8) days, and private insurance patients, 2.4 (0.5) days.

Discussion

According to an extensive body of literature, patients with government insurance have limited access to specialty care.1,11,12 Medicaid-insured children in need of orthopedic care are no exception. Sabharwal and colleagues13 examined a database of pediatric fracture cases and found that 52% of the privately insured patients and 22% of the publicly insured patients received orthopedic care (P = .013).13 When Pierce and colleagues14 called 42 orthopedic practices regarding a fictitious 14-year-old patient with an anterior cruciate ligament tear, 38 offered an appointment within 2 weeks to a privately insured patient, and 6 offered such an appointment to a publicly insured patient. Skaggs and colleagues4 surveyed 230 orthopedic practices nationally and found that Medicaid-insured children had limited access to orthopedic care; 41 practices (18%) would not see a child with Medicaid under any circumstances. Using a fictitious case of a 10-year-old boy with a forearm fracture, Iobst and colleagues3 tried making an appointment at 100 orthopedic offices. Eight gave an appointment within 1 week to a Medicaid-insured patient, and 36 gave an appointment to a privately insured patient.3

There are few data regarding insurance status and scoliosis care in children. Spinal deformity differs from simple fractures and ligamentous injuries, as timely care may result in a less invasive treatment (bracing) if the curvature is caught early. Goldstein and colleagues9 recently evaluated 642 patients who presented for scoliosis evaluation over a 10-year period. There was no difference in curve magnitudes between patients with and without Medicaid insurance. Thirty-two percent of these patients were evaluated for a second opinion, and the authors chose not to subdivide patients on the basis of curve severity and treatment needed, noting only no difference between groups. There was no discussion of the potential difference between patients with and without private insurance with respect to surgically versus nonsurgically treated curves. We wanted to focus specifically on patients who required surgical intervention, as our experience has been that many patients with government insurance present with either very mild scoliosis (10°) or very large curves that were not identified because of lack of primary care access or inadequate school screening. Although summing these 2 groups would result in a similar average, they would represent a different cohort than patients with curves along a bell curve. Furthermore, it is the group of patients who would require surgical intervention that is so critical to identify early in order to intervene.

Our data suggest a difference in presenting curves between patients with and without private insurance. The approximately 10° difference between patient groups in this study could potentially represent the difference between bracing and surgery. Furthermore, Miyanji and colleagues6 evaluated the relationship between Cobb angle and health care consumption and correlated larger curve magnitudes with more levels fused, longer surgeries, and higher rates of transfusion. Specifically, every 10° increase in curve magnitude resulted in 7.8 more minutes of operative time, 0.3 extra levels fused, and 1.5 times increased risk for requiring a blood transfusion.

Cho and Egorova15 recently evaluated insurance status with respect to surgical outcomes using a national inpatient database and found that 42.4% of surgeries for AIS in children with Medicaid had fusions involving 9 or more levels, whereas only 33.6% of privately insured patients had fusions of 9 or more levels. There was no difference in osteotomy or reoperation for pseudarthrosis between groups, but there was a slightly higher rate of infectious (1.1% vs 0.6%) and hemorrhagic (2.5% vs 1.7%) complications in the Medicaid group. Hospital stay was longer in patients with Medicaid, though complications were not different between groups.

The mean difference in the magnitude of the curves treated in our study was not more than 10° between patients with and without Medicaid, perhaps explaining the lack of a statistically significant difference in number of levels fused between groups. Although the groups were similar with respect to the percentage requiring posterior column spinal osteotomies, we noted a difference in estimated blood loss between groups, likely explained by the fact that a junior surgeon was added just before initiation of the study period, potentially skewing the estimated blood loss as this surgeon gained experience. Payer status has been correlated to length of hospital stay in children with scoliosis. Vitale and colleagues8 reviewed the effect of payer status on surgical outcomes in 3606 scoliosis patients from a statewide database in California and concluded that, compared with patients having all other payment sources, Medicaid patients had higher odds for complications and longer hospital stay. Our hospital has adopted a highly coordinated care pathway that allows for discharge on postoperative day 2, likely explaining the lack of any difference in postoperative stay.16

The disparity in curve magnitudes among patients with and without private insurance is striking and probably multifactorial. Very likely, the combination of schools with limited screening programs within urban or rural school systems,17 restricted access to pediatricians,18,19 and longer waits to see orthopedic specialists20 all contribute to this disparity. It should be noted that school screening is mandatory in our state. This discrepancy may be related to a previously established tendency in minority populations toward waiting longer to seek care and refusing surgical recommendations, though we were unable to query socioeconomic factors such as race and household income.21,22 It is clearly important to increase access to care for underinsured patients with scoliosis. A comprehensive approach, including providing better education in the schools, establishing communication with referring primary care providers, and increasing access through more physicians or physician extenders, is likely needed. Orthopedists should perhaps treat scoliosis evaluation with the same sense of urgency given to minor fractures, and primary care providers should try to ensure that appropriate referrals for scoliosis are made. Also curious was the shorter travel distance for Medicaid patients versus private insurance patients in this study. We hypothesize this is related to our urban location and its large Medicaid population.

Our study had several limitations. Our electronic medical records (EMR) system does not store data related to the time a patient calls for an initial appointment, limiting our ability to determine how long patients waited for their initial consultation. Furthermore, the decision to undergo surgery is multifactorial and cannot be simplified into time from initial recommendation to surgery, as some patients delay surgery because of school or other obligations. These data should be reasonably consistent over time, as patients seen in the early spring in both groups may delay surgery until the summer, and those diagnosed in June may prefer earlier surgery.

Summary

Children with AIS are at risk for curve progression. Therefore, delays in providing timely care may result in worsening scoliosis. Compared with private insurance patients, Medicaid patients presented with larger curve magnitudes. Further study is needed to better delineate ways to improve care access for patients with scoliosis in communities with larger Medicaid populations.

1. Skaggs DL. Less access to care for children with Medicaid. Orthopedics. 2003;26(12):1184, 1186.

2. Skinner AC, Mayer ML. Effects of insurance status on children’s access to specialty care: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:194.

3. Iobst C, King W, Baitner A, Tidwell M, Swirsky S, Skaggs DL. Access to care for children with fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(3):244-247.

4. Skaggs DL, Lehmann CL, Rice C, et al. Access to orthopaedic care for children with Medicaid versus private insurance: results of a national survey. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(3):400-404.

5. Skaggs DL, Oda JE, Lerman L, et al. Insurance status and delay in orthotic treatment in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(1):94-97.

6. Miyanji F, Slobogean GP, Samdani AF, et al. Is larger scoliosis curve magnitude associated with increased perioperative health-care resource utilization? A multicenter analysis of 325 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis curves. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(9):809-813.

7. Nuno M, Drazin DG, Acosta FL Jr. Differences in treatments and outcomes for idiopathic scoliosis patients treated in the United States from 1998 to 2007: impact of socioeconomic variables and ethnicity. Spine J. 2013;13(2):116-123.

8. Vitale MA, Arons RR, Hyman JE, Skaggs DL, Roye DP, Vitale MG. The contribution of hospital volume, payer status, and other factors on the surgical outcomes of scoliosis patients: a review of 3,606 cases in the state of California. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):393-399.

9. Goldstein RY, Joiner ER, Skaggs DL. Insurance status does not predict curve magnitude in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis at first presentation to an orthopaedic surgeon. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015;35(1):39-42.

10. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169-1181.

11. Alosh H, Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL. Insurance status, geography, race, and ethnicity as predictors of anterior cervical spine surgery rates and in-hospital mortality: an examination of United States trends from 1992 to 2005. Spine. 2009;34(18):1956-1962.

12. Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Hung YY, Wong S, Stoddard JJ. The unmet health needs of America’s children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 2):989-997.

13. Sabharwal S, Zhao C, McClemens E, Kaufmann A. Pediatric orthopaedic patients presenting to a university emergency department after visiting another emergency department: demographics and health insurance status. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):690-694.

14. Pierce TR, Mehlman CT, Tamai J, Skaggs DL. Access to care for the adolescent anterior cruciate ligament patient with Medicaid versus private insurance. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(3):245-248.

15. Cho SK, Egorova NN. The association between insurance status and complications, length of stay, and costs for pediatric idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2015;40(4):247-256.

16. Fletcher ND, Shourbaji N, Mitchell PM, Oswald TS, Devito DP, Bruce RW Jr. Clinical and economic implications of early discharge following posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Child Orthop. 2014;8(3):257-263.

17. Kasper MJ, Robbins L, Root L, Peterson MG, Allegrante JP. A musculoskeletal outreach screening, treatment, and education program for urban minority children. Arthritis Care Res. 1993;6(3):126-133.

18. Berman S, Dolins J, Tang SF, Yudkowsky B. Factors that influence the willingness of private primary care pediatricians to accept more Medicaid patients. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 pt 1):239-248.

19. Sommers BD. Protecting low-income children’s access to care: are physician visits associated with reduced patient dropout from Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program? Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e36-e42.

20. Bisgaier J, Polsky D, Rhodes KV. Academic medical centers and equity in specialty care access for children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):304-310.

21. Sedlis SP, Fisher VJ, Tice D, Esposito R, Madmon L, Steinberg EH. Racial differences in performance of invasive cardiac procedures in a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(8):899-901.

22. Mitchell JB, McCormack LA. Time trends in late-stage diagnosis of cervical cancer. Differences by race/ethnicity and income. Med Care. 1997;35(12):1220-1224.

Rising health care costs have led many health insurers to limit benefits, which may be a problem for children in need of specialty care. Uninsured children have poorer access to specialty care than insured children. Children with public health coverage have better access to specialty care than uninsured children but inferior access compared with privately insured children.1,2 It is well documented that children with government insurance have limited access to orthopedic care for fractures, ligamentous knee injuries, and other injuries.1,3-5 Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) differs from many other conditions managed by pediatric orthopedists, as it may be progressive, with management becoming increasingly more complex as the curve magnitude increases.6 The ability to access care earlier in the disease process may allow for earlier nonoperative interventions, such as bracing. For patients who require spinal fusion, earlier diagnosis and referral to a specialist could potentially result in shorter fusions and preserve distal motion segments. The ability to access the health care system in a timely fashion would therefore be of utmost importance for patients with scoliosis.

The literature on AIS is lacking in studies focused on care access based on insurance coverage and the potential impact that this may have on curve progression.7-9 We conducted a study to determine whether there is a difference between patients with and without private insurance who present to a busy urban pediatric orthopedic practice for management of scoliosis that eventually resulted in surgical treatment.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients (age, 10-18 years) who underwent posterior spinal fusion (PSF) for newly diagnosed AIS between 2008 and 2012. We excluded patients treated with growing spine instrumentation (growing rods), patients younger than 10 years or older than 18 years at presentation, and patients without adequate radiographs or clinical data, including insurance status. To focus on newly diagnosed scoliosis, we also excluded patients who had been seen for second opinions or whose scoliosis had been managed elsewhere in the past. Patients with syndromic, neuromuscular, or congenital scoliosis were also excluded.

Medical records were checked to ascertain time from initial evaluation to decision for surgery, time from recommendation for surgery until actual procedure, and insurance status. Distance traveled was figured from patients’ home addresses. Cobb angles were calculated from initial preoperative and final preoperative posteroanterior (PA) radiographs. Curves as seen on PA, lateral, and maximal effort, supine bending thoracic and lumbar radiographs from the initial preoperative visit were classified using the system of Lenke and colleagues.10 Hospital records were queried to determine number of levels fused at surgery, number of implants placed, and length of stay. Patients were evaluated without prior screening of insurance status and without prior consultation with referring physicians. Surgical procedures were scheduled on a first-come, first-served basis without preference for insurance status.

Results

We identified 135 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed AIS treated with PSF by our group between January 2008 and December 2012 (Table 1). Sixty-one percent had private insurance; 39% had Medicaid. There was no difference in age or ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score between groups. Mean (SD) Cobb angle at initial presentation was 47.5° (14.3°) (range, 18.0°-86.0°) for the private insurance group and 57.2° (15.7°) (range, 23.0°-95.0°) for the Medicaid group (P < .0001). At time of surgery, mean (SD) Cobb angles were 54.6° (11.7°) and 60.6° (13.9°) for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively (P = .008). There was no difference in curve types (Lenke and colleagues10 classification) between groups (Table 2, P = .83). Medicaid patients traveled a shorter mean (SD) distance for care, 56.3 (57.0) miles, versus 73.7 (66.7) miles (P = .05). There was no statistical difference (P = .14) in mean (SD) surgical wait time from surgery recommendation to actual surgery, 103.1 (62.4) days and 128.8 (137.5) days for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively. The difference between patient groups in mean (SD) number of levels fused did not reach statistical significance (P = .16), 10.3 (2.2) levels for the Medicaid group and 9.7 (2.3) levels for the private insurance group. Mean (SD) estimated blood loss was higher for Medicaid patients, 445.7 (415.9) mL versus 335.1 (271.5) mL (P = .06), though there was no difference in use of posterior column osteotomies between groups. There was no difference (P = .11) in mean (SD) length of hospital stay between Medicaid patients, 2.6 (0.8) days, and private insurance patients, 2.4 (0.5) days.

Discussion

According to an extensive body of literature, patients with government insurance have limited access to specialty care.1,11,12 Medicaid-insured children in need of orthopedic care are no exception. Sabharwal and colleagues13 examined a database of pediatric fracture cases and found that 52% of the privately insured patients and 22% of the publicly insured patients received orthopedic care (P = .013).13 When Pierce and colleagues14 called 42 orthopedic practices regarding a fictitious 14-year-old patient with an anterior cruciate ligament tear, 38 offered an appointment within 2 weeks to a privately insured patient, and 6 offered such an appointment to a publicly insured patient. Skaggs and colleagues4 surveyed 230 orthopedic practices nationally and found that Medicaid-insured children had limited access to orthopedic care; 41 practices (18%) would not see a child with Medicaid under any circumstances. Using a fictitious case of a 10-year-old boy with a forearm fracture, Iobst and colleagues3 tried making an appointment at 100 orthopedic offices. Eight gave an appointment within 1 week to a Medicaid-insured patient, and 36 gave an appointment to a privately insured patient.3

There are few data regarding insurance status and scoliosis care in children. Spinal deformity differs from simple fractures and ligamentous injuries, as timely care may result in a less invasive treatment (bracing) if the curvature is caught early. Goldstein and colleagues9 recently evaluated 642 patients who presented for scoliosis evaluation over a 10-year period. There was no difference in curve magnitudes between patients with and without Medicaid insurance. Thirty-two percent of these patients were evaluated for a second opinion, and the authors chose not to subdivide patients on the basis of curve severity and treatment needed, noting only no difference between groups. There was no discussion of the potential difference between patients with and without private insurance with respect to surgically versus nonsurgically treated curves. We wanted to focus specifically on patients who required surgical intervention, as our experience has been that many patients with government insurance present with either very mild scoliosis (10°) or very large curves that were not identified because of lack of primary care access or inadequate school screening. Although summing these 2 groups would result in a similar average, they would represent a different cohort than patients with curves along a bell curve. Furthermore, it is the group of patients who would require surgical intervention that is so critical to identify early in order to intervene.

Our data suggest a difference in presenting curves between patients with and without private insurance. The approximately 10° difference between patient groups in this study could potentially represent the difference between bracing and surgery. Furthermore, Miyanji and colleagues6 evaluated the relationship between Cobb angle and health care consumption and correlated larger curve magnitudes with more levels fused, longer surgeries, and higher rates of transfusion. Specifically, every 10° increase in curve magnitude resulted in 7.8 more minutes of operative time, 0.3 extra levels fused, and 1.5 times increased risk for requiring a blood transfusion.

Cho and Egorova15 recently evaluated insurance status with respect to surgical outcomes using a national inpatient database and found that 42.4% of surgeries for AIS in children with Medicaid had fusions involving 9 or more levels, whereas only 33.6% of privately insured patients had fusions of 9 or more levels. There was no difference in osteotomy or reoperation for pseudarthrosis between groups, but there was a slightly higher rate of infectious (1.1% vs 0.6%) and hemorrhagic (2.5% vs 1.7%) complications in the Medicaid group. Hospital stay was longer in patients with Medicaid, though complications were not different between groups.

The mean difference in the magnitude of the curves treated in our study was not more than 10° between patients with and without Medicaid, perhaps explaining the lack of a statistically significant difference in number of levels fused between groups. Although the groups were similar with respect to the percentage requiring posterior column spinal osteotomies, we noted a difference in estimated blood loss between groups, likely explained by the fact that a junior surgeon was added just before initiation of the study period, potentially skewing the estimated blood loss as this surgeon gained experience. Payer status has been correlated to length of hospital stay in children with scoliosis. Vitale and colleagues8 reviewed the effect of payer status on surgical outcomes in 3606 scoliosis patients from a statewide database in California and concluded that, compared with patients having all other payment sources, Medicaid patients had higher odds for complications and longer hospital stay. Our hospital has adopted a highly coordinated care pathway that allows for discharge on postoperative day 2, likely explaining the lack of any difference in postoperative stay.16

The disparity in curve magnitudes among patients with and without private insurance is striking and probably multifactorial. Very likely, the combination of schools with limited screening programs within urban or rural school systems,17 restricted access to pediatricians,18,19 and longer waits to see orthopedic specialists20 all contribute to this disparity. It should be noted that school screening is mandatory in our state. This discrepancy may be related to a previously established tendency in minority populations toward waiting longer to seek care and refusing surgical recommendations, though we were unable to query socioeconomic factors such as race and household income.21,22 It is clearly important to increase access to care for underinsured patients with scoliosis. A comprehensive approach, including providing better education in the schools, establishing communication with referring primary care providers, and increasing access through more physicians or physician extenders, is likely needed. Orthopedists should perhaps treat scoliosis evaluation with the same sense of urgency given to minor fractures, and primary care providers should try to ensure that appropriate referrals for scoliosis are made. Also curious was the shorter travel distance for Medicaid patients versus private insurance patients in this study. We hypothesize this is related to our urban location and its large Medicaid population.

Our study had several limitations. Our electronic medical records (EMR) system does not store data related to the time a patient calls for an initial appointment, limiting our ability to determine how long patients waited for their initial consultation. Furthermore, the decision to undergo surgery is multifactorial and cannot be simplified into time from initial recommendation to surgery, as some patients delay surgery because of school or other obligations. These data should be reasonably consistent over time, as patients seen in the early spring in both groups may delay surgery until the summer, and those diagnosed in June may prefer earlier surgery.

Summary

Children with AIS are at risk for curve progression. Therefore, delays in providing timely care may result in worsening scoliosis. Compared with private insurance patients, Medicaid patients presented with larger curve magnitudes. Further study is needed to better delineate ways to improve care access for patients with scoliosis in communities with larger Medicaid populations.

Rising health care costs have led many health insurers to limit benefits, which may be a problem for children in need of specialty care. Uninsured children have poorer access to specialty care than insured children. Children with public health coverage have better access to specialty care than uninsured children but inferior access compared with privately insured children.1,2 It is well documented that children with government insurance have limited access to orthopedic care for fractures, ligamentous knee injuries, and other injuries.1,3-5 Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) differs from many other conditions managed by pediatric orthopedists, as it may be progressive, with management becoming increasingly more complex as the curve magnitude increases.6 The ability to access care earlier in the disease process may allow for earlier nonoperative interventions, such as bracing. For patients who require spinal fusion, earlier diagnosis and referral to a specialist could potentially result in shorter fusions and preserve distal motion segments. The ability to access the health care system in a timely fashion would therefore be of utmost importance for patients with scoliosis.

The literature on AIS is lacking in studies focused on care access based on insurance coverage and the potential impact that this may have on curve progression.7-9 We conducted a study to determine whether there is a difference between patients with and without private insurance who present to a busy urban pediatric orthopedic practice for management of scoliosis that eventually resulted in surgical treatment.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients (age, 10-18 years) who underwent posterior spinal fusion (PSF) for newly diagnosed AIS between 2008 and 2012. We excluded patients treated with growing spine instrumentation (growing rods), patients younger than 10 years or older than 18 years at presentation, and patients without adequate radiographs or clinical data, including insurance status. To focus on newly diagnosed scoliosis, we also excluded patients who had been seen for second opinions or whose scoliosis had been managed elsewhere in the past. Patients with syndromic, neuromuscular, or congenital scoliosis were also excluded.

Medical records were checked to ascertain time from initial evaluation to decision for surgery, time from recommendation for surgery until actual procedure, and insurance status. Distance traveled was figured from patients’ home addresses. Cobb angles were calculated from initial preoperative and final preoperative posteroanterior (PA) radiographs. Curves as seen on PA, lateral, and maximal effort, supine bending thoracic and lumbar radiographs from the initial preoperative visit were classified using the system of Lenke and colleagues.10 Hospital records were queried to determine number of levels fused at surgery, number of implants placed, and length of stay. Patients were evaluated without prior screening of insurance status and without prior consultation with referring physicians. Surgical procedures were scheduled on a first-come, first-served basis without preference for insurance status.

Results

We identified 135 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed AIS treated with PSF by our group between January 2008 and December 2012 (Table 1). Sixty-one percent had private insurance; 39% had Medicaid. There was no difference in age or ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score between groups. Mean (SD) Cobb angle at initial presentation was 47.5° (14.3°) (range, 18.0°-86.0°) for the private insurance group and 57.2° (15.7°) (range, 23.0°-95.0°) for the Medicaid group (P < .0001). At time of surgery, mean (SD) Cobb angles were 54.6° (11.7°) and 60.6° (13.9°) for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively (P = .008). There was no difference in curve types (Lenke and colleagues10 classification) between groups (Table 2, P = .83). Medicaid patients traveled a shorter mean (SD) distance for care, 56.3 (57.0) miles, versus 73.7 (66.7) miles (P = .05). There was no statistical difference (P = .14) in mean (SD) surgical wait time from surgery recommendation to actual surgery, 103.1 (62.4) days and 128.8 (137.5) days for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively. The difference between patient groups in mean (SD) number of levels fused did not reach statistical significance (P = .16), 10.3 (2.2) levels for the Medicaid group and 9.7 (2.3) levels for the private insurance group. Mean (SD) estimated blood loss was higher for Medicaid patients, 445.7 (415.9) mL versus 335.1 (271.5) mL (P = .06), though there was no difference in use of posterior column osteotomies between groups. There was no difference (P = .11) in mean (SD) length of hospital stay between Medicaid patients, 2.6 (0.8) days, and private insurance patients, 2.4 (0.5) days.

Discussion

According to an extensive body of literature, patients with government insurance have limited access to specialty care.1,11,12 Medicaid-insured children in need of orthopedic care are no exception. Sabharwal and colleagues13 examined a database of pediatric fracture cases and found that 52% of the privately insured patients and 22% of the publicly insured patients received orthopedic care (P = .013).13 When Pierce and colleagues14 called 42 orthopedic practices regarding a fictitious 14-year-old patient with an anterior cruciate ligament tear, 38 offered an appointment within 2 weeks to a privately insured patient, and 6 offered such an appointment to a publicly insured patient. Skaggs and colleagues4 surveyed 230 orthopedic practices nationally and found that Medicaid-insured children had limited access to orthopedic care; 41 practices (18%) would not see a child with Medicaid under any circumstances. Using a fictitious case of a 10-year-old boy with a forearm fracture, Iobst and colleagues3 tried making an appointment at 100 orthopedic offices. Eight gave an appointment within 1 week to a Medicaid-insured patient, and 36 gave an appointment to a privately insured patient.3

There are few data regarding insurance status and scoliosis care in children. Spinal deformity differs from simple fractures and ligamentous injuries, as timely care may result in a less invasive treatment (bracing) if the curvature is caught early. Goldstein and colleagues9 recently evaluated 642 patients who presented for scoliosis evaluation over a 10-year period. There was no difference in curve magnitudes between patients with and without Medicaid insurance. Thirty-two percent of these patients were evaluated for a second opinion, and the authors chose not to subdivide patients on the basis of curve severity and treatment needed, noting only no difference between groups. There was no discussion of the potential difference between patients with and without private insurance with respect to surgically versus nonsurgically treated curves. We wanted to focus specifically on patients who required surgical intervention, as our experience has been that many patients with government insurance present with either very mild scoliosis (10°) or very large curves that were not identified because of lack of primary care access or inadequate school screening. Although summing these 2 groups would result in a similar average, they would represent a different cohort than patients with curves along a bell curve. Furthermore, it is the group of patients who would require surgical intervention that is so critical to identify early in order to intervene.

Our data suggest a difference in presenting curves between patients with and without private insurance. The approximately 10° difference between patient groups in this study could potentially represent the difference between bracing and surgery. Furthermore, Miyanji and colleagues6 evaluated the relationship between Cobb angle and health care consumption and correlated larger curve magnitudes with more levels fused, longer surgeries, and higher rates of transfusion. Specifically, every 10° increase in curve magnitude resulted in 7.8 more minutes of operative time, 0.3 extra levels fused, and 1.5 times increased risk for requiring a blood transfusion.

Cho and Egorova15 recently evaluated insurance status with respect to surgical outcomes using a national inpatient database and found that 42.4% of surgeries for AIS in children with Medicaid had fusions involving 9 or more levels, whereas only 33.6% of privately insured patients had fusions of 9 or more levels. There was no difference in osteotomy or reoperation for pseudarthrosis between groups, but there was a slightly higher rate of infectious (1.1% vs 0.6%) and hemorrhagic (2.5% vs 1.7%) complications in the Medicaid group. Hospital stay was longer in patients with Medicaid, though complications were not different between groups.

The mean difference in the magnitude of the curves treated in our study was not more than 10° between patients with and without Medicaid, perhaps explaining the lack of a statistically significant difference in number of levels fused between groups. Although the groups were similar with respect to the percentage requiring posterior column spinal osteotomies, we noted a difference in estimated blood loss between groups, likely explained by the fact that a junior surgeon was added just before initiation of the study period, potentially skewing the estimated blood loss as this surgeon gained experience. Payer status has been correlated to length of hospital stay in children with scoliosis. Vitale and colleagues8 reviewed the effect of payer status on surgical outcomes in 3606 scoliosis patients from a statewide database in California and concluded that, compared with patients having all other payment sources, Medicaid patients had higher odds for complications and longer hospital stay. Our hospital has adopted a highly coordinated care pathway that allows for discharge on postoperative day 2, likely explaining the lack of any difference in postoperative stay.16

The disparity in curve magnitudes among patients with and without private insurance is striking and probably multifactorial. Very likely, the combination of schools with limited screening programs within urban or rural school systems,17 restricted access to pediatricians,18,19 and longer waits to see orthopedic specialists20 all contribute to this disparity. It should be noted that school screening is mandatory in our state. This discrepancy may be related to a previously established tendency in minority populations toward waiting longer to seek care and refusing surgical recommendations, though we were unable to query socioeconomic factors such as race and household income.21,22 It is clearly important to increase access to care for underinsured patients with scoliosis. A comprehensive approach, including providing better education in the schools, establishing communication with referring primary care providers, and increasing access through more physicians or physician extenders, is likely needed. Orthopedists should perhaps treat scoliosis evaluation with the same sense of urgency given to minor fractures, and primary care providers should try to ensure that appropriate referrals for scoliosis are made. Also curious was the shorter travel distance for Medicaid patients versus private insurance patients in this study. We hypothesize this is related to our urban location and its large Medicaid population.

Our study had several limitations. Our electronic medical records (EMR) system does not store data related to the time a patient calls for an initial appointment, limiting our ability to determine how long patients waited for their initial consultation. Furthermore, the decision to undergo surgery is multifactorial and cannot be simplified into time from initial recommendation to surgery, as some patients delay surgery because of school or other obligations. These data should be reasonably consistent over time, as patients seen in the early spring in both groups may delay surgery until the summer, and those diagnosed in June may prefer earlier surgery.

Summary

Children with AIS are at risk for curve progression. Therefore, delays in providing timely care may result in worsening scoliosis. Compared with private insurance patients, Medicaid patients presented with larger curve magnitudes. Further study is needed to better delineate ways to improve care access for patients with scoliosis in communities with larger Medicaid populations.

1. Skaggs DL. Less access to care for children with Medicaid. Orthopedics. 2003;26(12):1184, 1186.

2. Skinner AC, Mayer ML. Effects of insurance status on children’s access to specialty care: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:194.

3. Iobst C, King W, Baitner A, Tidwell M, Swirsky S, Skaggs DL. Access to care for children with fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(3):244-247.

4. Skaggs DL, Lehmann CL, Rice C, et al. Access to orthopaedic care for children with Medicaid versus private insurance: results of a national survey. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(3):400-404.

5. Skaggs DL, Oda JE, Lerman L, et al. Insurance status and delay in orthotic treatment in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(1):94-97.

6. Miyanji F, Slobogean GP, Samdani AF, et al. Is larger scoliosis curve magnitude associated with increased perioperative health-care resource utilization? A multicenter analysis of 325 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis curves. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(9):809-813.

7. Nuno M, Drazin DG, Acosta FL Jr. Differences in treatments and outcomes for idiopathic scoliosis patients treated in the United States from 1998 to 2007: impact of socioeconomic variables and ethnicity. Spine J. 2013;13(2):116-123.

8. Vitale MA, Arons RR, Hyman JE, Skaggs DL, Roye DP, Vitale MG. The contribution of hospital volume, payer status, and other factors on the surgical outcomes of scoliosis patients: a review of 3,606 cases in the state of California. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):393-399.

9. Goldstein RY, Joiner ER, Skaggs DL. Insurance status does not predict curve magnitude in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis at first presentation to an orthopaedic surgeon. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015;35(1):39-42.

10. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169-1181.

11. Alosh H, Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL. Insurance status, geography, race, and ethnicity as predictors of anterior cervical spine surgery rates and in-hospital mortality: an examination of United States trends from 1992 to 2005. Spine. 2009;34(18):1956-1962.

12. Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Hung YY, Wong S, Stoddard JJ. The unmet health needs of America’s children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 2):989-997.

13. Sabharwal S, Zhao C, McClemens E, Kaufmann A. Pediatric orthopaedic patients presenting to a university emergency department after visiting another emergency department: demographics and health insurance status. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):690-694.

14. Pierce TR, Mehlman CT, Tamai J, Skaggs DL. Access to care for the adolescent anterior cruciate ligament patient with Medicaid versus private insurance. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(3):245-248.

15. Cho SK, Egorova NN. The association between insurance status and complications, length of stay, and costs for pediatric idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2015;40(4):247-256.

16. Fletcher ND, Shourbaji N, Mitchell PM, Oswald TS, Devito DP, Bruce RW Jr. Clinical and economic implications of early discharge following posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Child Orthop. 2014;8(3):257-263.

17. Kasper MJ, Robbins L, Root L, Peterson MG, Allegrante JP. A musculoskeletal outreach screening, treatment, and education program for urban minority children. Arthritis Care Res. 1993;6(3):126-133.

18. Berman S, Dolins J, Tang SF, Yudkowsky B. Factors that influence the willingness of private primary care pediatricians to accept more Medicaid patients. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 pt 1):239-248.

19. Sommers BD. Protecting low-income children’s access to care: are physician visits associated with reduced patient dropout from Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program? Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e36-e42.

20. Bisgaier J, Polsky D, Rhodes KV. Academic medical centers and equity in specialty care access for children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):304-310.

21. Sedlis SP, Fisher VJ, Tice D, Esposito R, Madmon L, Steinberg EH. Racial differences in performance of invasive cardiac procedures in a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(8):899-901.

22. Mitchell JB, McCormack LA. Time trends in late-stage diagnosis of cervical cancer. Differences by race/ethnicity and income. Med Care. 1997;35(12):1220-1224.

1. Skaggs DL. Less access to care for children with Medicaid. Orthopedics. 2003;26(12):1184, 1186.

2. Skinner AC, Mayer ML. Effects of insurance status on children’s access to specialty care: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:194.

3. Iobst C, King W, Baitner A, Tidwell M, Swirsky S, Skaggs DL. Access to care for children with fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(3):244-247.

4. Skaggs DL, Lehmann CL, Rice C, et al. Access to orthopaedic care for children with Medicaid versus private insurance: results of a national survey. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(3):400-404.

5. Skaggs DL, Oda JE, Lerman L, et al. Insurance status and delay in orthotic treatment in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(1):94-97.

6. Miyanji F, Slobogean GP, Samdani AF, et al. Is larger scoliosis curve magnitude associated with increased perioperative health-care resource utilization? A multicenter analysis of 325 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis curves. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(9):809-813.

7. Nuno M, Drazin DG, Acosta FL Jr. Differences in treatments and outcomes for idiopathic scoliosis patients treated in the United States from 1998 to 2007: impact of socioeconomic variables and ethnicity. Spine J. 2013;13(2):116-123.

8. Vitale MA, Arons RR, Hyman JE, Skaggs DL, Roye DP, Vitale MG. The contribution of hospital volume, payer status, and other factors on the surgical outcomes of scoliosis patients: a review of 3,606 cases in the state of California. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):393-399.

9. Goldstein RY, Joiner ER, Skaggs DL. Insurance status does not predict curve magnitude in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis at first presentation to an orthopaedic surgeon. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015;35(1):39-42.

10. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169-1181.

11. Alosh H, Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL. Insurance status, geography, race, and ethnicity as predictors of anterior cervical spine surgery rates and in-hospital mortality: an examination of United States trends from 1992 to 2005. Spine. 2009;34(18):1956-1962.

12. Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Hung YY, Wong S, Stoddard JJ. The unmet health needs of America’s children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 2):989-997.

13. Sabharwal S, Zhao C, McClemens E, Kaufmann A. Pediatric orthopaedic patients presenting to a university emergency department after visiting another emergency department: demographics and health insurance status. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):690-694.

14. Pierce TR, Mehlman CT, Tamai J, Skaggs DL. Access to care for the adolescent anterior cruciate ligament patient with Medicaid versus private insurance. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(3):245-248.

15. Cho SK, Egorova NN. The association between insurance status and complications, length of stay, and costs for pediatric idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2015;40(4):247-256.

16. Fletcher ND, Shourbaji N, Mitchell PM, Oswald TS, Devito DP, Bruce RW Jr. Clinical and economic implications of early discharge following posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Child Orthop. 2014;8(3):257-263.