User login

Six Keys to a Successful Annual Meeting

Michael Pistoria, DO, FACP, SFHM, is as guilty as you are of not always getting the most out of the annual meeting—and he’s one of the people planning it.

Dr. Pistoria, HM12 assistant course director and hospitalist at Lehigh Valley Health Network in Allentown, Pa., always suggests that if an HM group sends more than one person to the annual meeting, those people should split up and go to as many different sessions as possible. But then, at HM11 in Dallas, an interesting course about an accountable-care unit caught the attention of three people from his office.

“I went, our senior vice president of care continuum went, and the director of our program—we were all there,” Dr. Pistoria says. “I’m thinking, ‘Well this is good, we’re all going to get a slightly different take on it and we’re all going to be listening for different things, and, when we do sit down to compare notes, this is going to be helpful.’ But there were other sessions we could be in.”

To be clear, there is no wrong way to attend an annual meeting. But like knowing which nurse shepherds a smoother discharge, there’s always a way to do it better. Tips from Dr. Pistoria and HM12 course director Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, include:

—Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, HM12 course director

- Prepare. Set up at least a basic schedule or pick out a few sessions to sit in on before arriving at HM12, or you risk trying to build a successful meeting on the fly. “I would treat this much like you would your first semester of college,” Dr. Glasheen says. “You wouldn’t just show up and see what course you wanted to go to. You’d spend some time prior to showing up....If you don’t have a game plan, you’re going to end up missing out on something you want to learn.”

- Go where you friends don’t. As Dr. Pistoria attests, it’s a natural tendency to want to attend sessions with colleagues and critique together. However, this is a once-a-year opportunity. Attend different sessions and compare notes.

- Attend the keynote addresses. This year’s lineup features a national election analyst for “CBS News,” the chief medical officer of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and the incoming chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). Between them, there probably are a few good nuggets to glean.

- Attend the special-interest forums. SHM holds a series of small-group sessions focused on such hyperlocal topics as rural HM and health information technology (HIT), among others. Society staff and leadership take notes and let attendees drive the conversation.

- Network, network, network. Everyone had that first meeting where they didn’t know who was who, so feel free to introduce yourself to anybody. Get business cards from everybody. And hit the hotel hotspots armed with questions and a willingness to buy a potential new relationship a drink.

- “There’s a tremendous willingness to help new people, to answer questions, to have the hallway questions, the conversations that occur at 11 o’clock at night at the bar,” Dr. Pistoria says. “If you see somebody and you say, ‘Hey, you know, I was in your session earlier, can I ask you a couple of follow-up questions?’ People are going to say, ‘Hell yes, sit down. Let’s talk.’ If people remember that and aren’t shy, I think people really can maximize the potential benefit.”

- Share what you learn. Start a quality initiative or talk with your C-suite about starting a project. Email some of your new contacts to start a dialogue. Don’t go home, give one brown-bag session to your colleagues, and wait until next year’s annual meeting to think about the “big picture” again.

“It’s easy to get back home and fall right back into the patterns you were doing before,” Dr. Glasheen says. “If you get excited by something at the annual meeting, go back home and really work at putting that into place.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

To get involved, visit www.hospitalmedicine2012.org/schedule

Michael Pistoria, DO, FACP, SFHM, is as guilty as you are of not always getting the most out of the annual meeting—and he’s one of the people planning it.

Dr. Pistoria, HM12 assistant course director and hospitalist at Lehigh Valley Health Network in Allentown, Pa., always suggests that if an HM group sends more than one person to the annual meeting, those people should split up and go to as many different sessions as possible. But then, at HM11 in Dallas, an interesting course about an accountable-care unit caught the attention of three people from his office.

“I went, our senior vice president of care continuum went, and the director of our program—we were all there,” Dr. Pistoria says. “I’m thinking, ‘Well this is good, we’re all going to get a slightly different take on it and we’re all going to be listening for different things, and, when we do sit down to compare notes, this is going to be helpful.’ But there were other sessions we could be in.”

To be clear, there is no wrong way to attend an annual meeting. But like knowing which nurse shepherds a smoother discharge, there’s always a way to do it better. Tips from Dr. Pistoria and HM12 course director Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, include:

—Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, HM12 course director

- Prepare. Set up at least a basic schedule or pick out a few sessions to sit in on before arriving at HM12, or you risk trying to build a successful meeting on the fly. “I would treat this much like you would your first semester of college,” Dr. Glasheen says. “You wouldn’t just show up and see what course you wanted to go to. You’d spend some time prior to showing up....If you don’t have a game plan, you’re going to end up missing out on something you want to learn.”

- Go where you friends don’t. As Dr. Pistoria attests, it’s a natural tendency to want to attend sessions with colleagues and critique together. However, this is a once-a-year opportunity. Attend different sessions and compare notes.

- Attend the keynote addresses. This year’s lineup features a national election analyst for “CBS News,” the chief medical officer of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and the incoming chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). Between them, there probably are a few good nuggets to glean.

- Attend the special-interest forums. SHM holds a series of small-group sessions focused on such hyperlocal topics as rural HM and health information technology (HIT), among others. Society staff and leadership take notes and let attendees drive the conversation.

- Network, network, network. Everyone had that first meeting where they didn’t know who was who, so feel free to introduce yourself to anybody. Get business cards from everybody. And hit the hotel hotspots armed with questions and a willingness to buy a potential new relationship a drink.

- “There’s a tremendous willingness to help new people, to answer questions, to have the hallway questions, the conversations that occur at 11 o’clock at night at the bar,” Dr. Pistoria says. “If you see somebody and you say, ‘Hey, you know, I was in your session earlier, can I ask you a couple of follow-up questions?’ People are going to say, ‘Hell yes, sit down. Let’s talk.’ If people remember that and aren’t shy, I think people really can maximize the potential benefit.”

- Share what you learn. Start a quality initiative or talk with your C-suite about starting a project. Email some of your new contacts to start a dialogue. Don’t go home, give one brown-bag session to your colleagues, and wait until next year’s annual meeting to think about the “big picture” again.

“It’s easy to get back home and fall right back into the patterns you were doing before,” Dr. Glasheen says. “If you get excited by something at the annual meeting, go back home and really work at putting that into place.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

To get involved, visit www.hospitalmedicine2012.org/schedule

Michael Pistoria, DO, FACP, SFHM, is as guilty as you are of not always getting the most out of the annual meeting—and he’s one of the people planning it.

Dr. Pistoria, HM12 assistant course director and hospitalist at Lehigh Valley Health Network in Allentown, Pa., always suggests that if an HM group sends more than one person to the annual meeting, those people should split up and go to as many different sessions as possible. But then, at HM11 in Dallas, an interesting course about an accountable-care unit caught the attention of three people from his office.

“I went, our senior vice president of care continuum went, and the director of our program—we were all there,” Dr. Pistoria says. “I’m thinking, ‘Well this is good, we’re all going to get a slightly different take on it and we’re all going to be listening for different things, and, when we do sit down to compare notes, this is going to be helpful.’ But there were other sessions we could be in.”

To be clear, there is no wrong way to attend an annual meeting. But like knowing which nurse shepherds a smoother discharge, there’s always a way to do it better. Tips from Dr. Pistoria and HM12 course director Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, include:

—Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, HM12 course director

- Prepare. Set up at least a basic schedule or pick out a few sessions to sit in on before arriving at HM12, or you risk trying to build a successful meeting on the fly. “I would treat this much like you would your first semester of college,” Dr. Glasheen says. “You wouldn’t just show up and see what course you wanted to go to. You’d spend some time prior to showing up....If you don’t have a game plan, you’re going to end up missing out on something you want to learn.”

- Go where you friends don’t. As Dr. Pistoria attests, it’s a natural tendency to want to attend sessions with colleagues and critique together. However, this is a once-a-year opportunity. Attend different sessions and compare notes.

- Attend the keynote addresses. This year’s lineup features a national election analyst for “CBS News,” the chief medical officer of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and the incoming chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). Between them, there probably are a few good nuggets to glean.

- Attend the special-interest forums. SHM holds a series of small-group sessions focused on such hyperlocal topics as rural HM and health information technology (HIT), among others. Society staff and leadership take notes and let attendees drive the conversation.

- Network, network, network. Everyone had that first meeting where they didn’t know who was who, so feel free to introduce yourself to anybody. Get business cards from everybody. And hit the hotel hotspots armed with questions and a willingness to buy a potential new relationship a drink.

- “There’s a tremendous willingness to help new people, to answer questions, to have the hallway questions, the conversations that occur at 11 o’clock at night at the bar,” Dr. Pistoria says. “If you see somebody and you say, ‘Hey, you know, I was in your session earlier, can I ask you a couple of follow-up questions?’ People are going to say, ‘Hell yes, sit down. Let’s talk.’ If people remember that and aren’t shy, I think people really can maximize the potential benefit.”

- Share what you learn. Start a quality initiative or talk with your C-suite about starting a project. Email some of your new contacts to start a dialogue. Don’t go home, give one brown-bag session to your colleagues, and wait until next year’s annual meeting to think about the “big picture” again.

“It’s easy to get back home and fall right back into the patterns you were doing before,” Dr. Glasheen says. “If you get excited by something at the annual meeting, go back home and really work at putting that into place.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

To get involved, visit www.hospitalmedicine2012.org/schedule

Policy Experts Say Hospital Medicine Should be Ready to Tackle Reform Challenges

In a restaurant, it’s called being in the weeds: when the duties of one’s job become so overwhelming that you can’t keep up with the pace. Think five new admissions at the end of a 12-hour workday.

That’s where Norm Ornstein, one of the keynote speakers at HM12 in San Diego, can help. A resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., and a longtime observer of all things political, Ornstein is in the weeds of healthcare reform on a partisan and policy level. He pens a weekly column for the Congressional newspaper Roll Call and also provides election analysis for “CBS News.” He has authored or edited multiple books, including “Intensive Care: How Congress Shapes Health Policy” and “The Permanent Campaign and Its Future.”

So hospitalists who too often feel that, between patient care and clinical research, they don’t have time to study the political landscape should probably plan to attend Ornstein’s address, tentatively dubbed “Making Health Policy in an Age of Dysfunctional Politics.” The Hospitalist spent a few moments with Ornstein as he prepared for his HM12 address.

What do you plan to speak about and what do you want hospitalists to take away from your talk?

We’re really going to be looking toward the fall matchup in the presidential campaign. And we know that health policy is going to be not the No. 1 issue—it’s pretty clear now that the economy and jobs will be the No. 1 issue—but it will be following pretty closely behind at No. 2. And we know we’re going to get a very hot debate on whether we can or should repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA). … But we also know that, repeal or not … health policy is up in the air. We’re going to go through some tumultuous changes. Everybody is on the line; who’s actually delivering services, or trying to, is going to have enormous challenges. It’s a perfect time to talk about these issues.

Healthcare professionals aren’t used to being part of the political maelstrom. What is their role in this process?

If anything, the last year or two should make it very clear to them they better be involved. … Whatever happens with the Affordable Care Act, we’re going to be making adjustments in public policy, and we’re going to be seeing massive adjustments in the private sector for years to come. Lots of people are going to be looking for the best ideas and looking for ways to make sure we can bend the cost curve, to use the cliché, but not sacrifice significantly services to people—and maybe even improve those services. It’s time, I think, for people in this world to understand it’s in their own self-interest to be engaged.

How nervous should hospitalists be that there really is a chance the ACA can be repealed?

I don’t think they should be worried that the whole kit and caboodle will be replaced. I think they should be concerned that we will see a combination of some elements of it perhaps repealed, but even more that the corrosive nature of our politics is such that Republicans, if they can’t repeal it, will do everything they can to bollocks up its implementation so that they can both score political points but also say, “See, we told you so.” This would be a challenge under the best of circumstances to make this work. But I think everybody has to be braced for what I think will be a series of some substantial bumps and jolts in the road along the way.

That is a lot of uncertainty for a hospitalist. How can they prepare?

I don’t think one can prepare adequately for the changes that are going to take place. What hospitalists have to do first is to make sure that they fulfill their own roles in caring for patients, but they should also be thinking about innovative approaches and ways of delivering services that are good for patents but also good for the system.

Is that enough—being at the vanguard of care delivery?

No, and I can’t give people assurances that there is any specific thing they can do that will make things work, or work better, because we’re moving into an uncertain environment—an uncertain environment in the real world where we’re going to see health as a share of GDP probably continue to go up for a while, but there will be some pushback against that; uncertainty as we try to integrate the public and private halves of our healthcare system a little bit better than we have; uncertainty as we find that the fiscal realities of America mean that you’ve got to put even more of a squeeze on Medicare, Medicaid, and even veterans’ health. Those things don’t happen in isolation.

Should doctors see this as an exciting time?

I think there is a bright side to this, which is there really is an opportunity here for innovation in ways to fulfill their oaths. There is an opportunity to find ways to provide better healthcare for people, better services to make their lives better.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

To get involved, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/advocacy

In a restaurant, it’s called being in the weeds: when the duties of one’s job become so overwhelming that you can’t keep up with the pace. Think five new admissions at the end of a 12-hour workday.

That’s where Norm Ornstein, one of the keynote speakers at HM12 in San Diego, can help. A resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., and a longtime observer of all things political, Ornstein is in the weeds of healthcare reform on a partisan and policy level. He pens a weekly column for the Congressional newspaper Roll Call and also provides election analysis for “CBS News.” He has authored or edited multiple books, including “Intensive Care: How Congress Shapes Health Policy” and “The Permanent Campaign and Its Future.”

So hospitalists who too often feel that, between patient care and clinical research, they don’t have time to study the political landscape should probably plan to attend Ornstein’s address, tentatively dubbed “Making Health Policy in an Age of Dysfunctional Politics.” The Hospitalist spent a few moments with Ornstein as he prepared for his HM12 address.

What do you plan to speak about and what do you want hospitalists to take away from your talk?

We’re really going to be looking toward the fall matchup in the presidential campaign. And we know that health policy is going to be not the No. 1 issue—it’s pretty clear now that the economy and jobs will be the No. 1 issue—but it will be following pretty closely behind at No. 2. And we know we’re going to get a very hot debate on whether we can or should repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA). … But we also know that, repeal or not … health policy is up in the air. We’re going to go through some tumultuous changes. Everybody is on the line; who’s actually delivering services, or trying to, is going to have enormous challenges. It’s a perfect time to talk about these issues.

Healthcare professionals aren’t used to being part of the political maelstrom. What is their role in this process?

If anything, the last year or two should make it very clear to them they better be involved. … Whatever happens with the Affordable Care Act, we’re going to be making adjustments in public policy, and we’re going to be seeing massive adjustments in the private sector for years to come. Lots of people are going to be looking for the best ideas and looking for ways to make sure we can bend the cost curve, to use the cliché, but not sacrifice significantly services to people—and maybe even improve those services. It’s time, I think, for people in this world to understand it’s in their own self-interest to be engaged.

How nervous should hospitalists be that there really is a chance the ACA can be repealed?

I don’t think they should be worried that the whole kit and caboodle will be replaced. I think they should be concerned that we will see a combination of some elements of it perhaps repealed, but even more that the corrosive nature of our politics is such that Republicans, if they can’t repeal it, will do everything they can to bollocks up its implementation so that they can both score political points but also say, “See, we told you so.” This would be a challenge under the best of circumstances to make this work. But I think everybody has to be braced for what I think will be a series of some substantial bumps and jolts in the road along the way.

That is a lot of uncertainty for a hospitalist. How can they prepare?

I don’t think one can prepare adequately for the changes that are going to take place. What hospitalists have to do first is to make sure that they fulfill their own roles in caring for patients, but they should also be thinking about innovative approaches and ways of delivering services that are good for patents but also good for the system.

Is that enough—being at the vanguard of care delivery?

No, and I can’t give people assurances that there is any specific thing they can do that will make things work, or work better, because we’re moving into an uncertain environment—an uncertain environment in the real world where we’re going to see health as a share of GDP probably continue to go up for a while, but there will be some pushback against that; uncertainty as we try to integrate the public and private halves of our healthcare system a little bit better than we have; uncertainty as we find that the fiscal realities of America mean that you’ve got to put even more of a squeeze on Medicare, Medicaid, and even veterans’ health. Those things don’t happen in isolation.

Should doctors see this as an exciting time?

I think there is a bright side to this, which is there really is an opportunity here for innovation in ways to fulfill their oaths. There is an opportunity to find ways to provide better healthcare for people, better services to make their lives better.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

To get involved, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/advocacy

In a restaurant, it’s called being in the weeds: when the duties of one’s job become so overwhelming that you can’t keep up with the pace. Think five new admissions at the end of a 12-hour workday.

That’s where Norm Ornstein, one of the keynote speakers at HM12 in San Diego, can help. A resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., and a longtime observer of all things political, Ornstein is in the weeds of healthcare reform on a partisan and policy level. He pens a weekly column for the Congressional newspaper Roll Call and also provides election analysis for “CBS News.” He has authored or edited multiple books, including “Intensive Care: How Congress Shapes Health Policy” and “The Permanent Campaign and Its Future.”

So hospitalists who too often feel that, between patient care and clinical research, they don’t have time to study the political landscape should probably plan to attend Ornstein’s address, tentatively dubbed “Making Health Policy in an Age of Dysfunctional Politics.” The Hospitalist spent a few moments with Ornstein as he prepared for his HM12 address.

What do you plan to speak about and what do you want hospitalists to take away from your talk?

We’re really going to be looking toward the fall matchup in the presidential campaign. And we know that health policy is going to be not the No. 1 issue—it’s pretty clear now that the economy and jobs will be the No. 1 issue—but it will be following pretty closely behind at No. 2. And we know we’re going to get a very hot debate on whether we can or should repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA). … But we also know that, repeal or not … health policy is up in the air. We’re going to go through some tumultuous changes. Everybody is on the line; who’s actually delivering services, or trying to, is going to have enormous challenges. It’s a perfect time to talk about these issues.

Healthcare professionals aren’t used to being part of the political maelstrom. What is their role in this process?

If anything, the last year or two should make it very clear to them they better be involved. … Whatever happens with the Affordable Care Act, we’re going to be making adjustments in public policy, and we’re going to be seeing massive adjustments in the private sector for years to come. Lots of people are going to be looking for the best ideas and looking for ways to make sure we can bend the cost curve, to use the cliché, but not sacrifice significantly services to people—and maybe even improve those services. It’s time, I think, for people in this world to understand it’s in their own self-interest to be engaged.

How nervous should hospitalists be that there really is a chance the ACA can be repealed?

I don’t think they should be worried that the whole kit and caboodle will be replaced. I think they should be concerned that we will see a combination of some elements of it perhaps repealed, but even more that the corrosive nature of our politics is such that Republicans, if they can’t repeal it, will do everything they can to bollocks up its implementation so that they can both score political points but also say, “See, we told you so.” This would be a challenge under the best of circumstances to make this work. But I think everybody has to be braced for what I think will be a series of some substantial bumps and jolts in the road along the way.

That is a lot of uncertainty for a hospitalist. How can they prepare?

I don’t think one can prepare adequately for the changes that are going to take place. What hospitalists have to do first is to make sure that they fulfill their own roles in caring for patients, but they should also be thinking about innovative approaches and ways of delivering services that are good for patents but also good for the system.

Is that enough—being at the vanguard of care delivery?

No, and I can’t give people assurances that there is any specific thing they can do that will make things work, or work better, because we’re moving into an uncertain environment—an uncertain environment in the real world where we’re going to see health as a share of GDP probably continue to go up for a while, but there will be some pushback against that; uncertainty as we try to integrate the public and private halves of our healthcare system a little bit better than we have; uncertainty as we find that the fiscal realities of America mean that you’ve got to put even more of a squeeze on Medicare, Medicaid, and even veterans’ health. Those things don’t happen in isolation.

Should doctors see this as an exciting time?

I think there is a bright side to this, which is there really is an opportunity here for innovation in ways to fulfill their oaths. There is an opportunity to find ways to provide better healthcare for people, better services to make their lives better.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

To get involved, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/advocacy

CME Credit at HM12

HM12 is planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of Blackwell Futura Media Services (BFMS) and SHM. BFMS is accredited by ACCME to provide CME for physicians.

HM12 registration is available at www.hospitalmedicine2012.org until March 5. SHM also permits walk-up registration at the San Diego Convention Center.

BFMS designates the educational activity for SHM’s annual meeting at a maximum of 19.75 Category 1 credits toward the AMA Physician’s Recognition Award. Each physician should claim only those hours of credit they actually spend in each educational activity. BFMS has designated a credit schedule for HM12’s pre-courses on April 1 as follows:

- ABIM MOC learning session, 6.5 credits;

- Advanced Interactive Critical Care, 7.75 credits;

- CMS’s Value-Based Purchasing Program, 3.75 credits;

- Medical Procedures, 7.5 credits;

- Portable Ultrasounds, 3.75 credits;

- Perioperative Medicine, 7.75 credits; and

- Practice Management, 7.5 credits.

Source: www.hospitalmedicine.org

HM12 is planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of Blackwell Futura Media Services (BFMS) and SHM. BFMS is accredited by ACCME to provide CME for physicians.

HM12 registration is available at www.hospitalmedicine2012.org until March 5. SHM also permits walk-up registration at the San Diego Convention Center.

BFMS designates the educational activity for SHM’s annual meeting at a maximum of 19.75 Category 1 credits toward the AMA Physician’s Recognition Award. Each physician should claim only those hours of credit they actually spend in each educational activity. BFMS has designated a credit schedule for HM12’s pre-courses on April 1 as follows:

- ABIM MOC learning session, 6.5 credits;

- Advanced Interactive Critical Care, 7.75 credits;

- CMS’s Value-Based Purchasing Program, 3.75 credits;

- Medical Procedures, 7.5 credits;

- Portable Ultrasounds, 3.75 credits;

- Perioperative Medicine, 7.75 credits; and

- Practice Management, 7.5 credits.

Source: www.hospitalmedicine.org

HM12 is planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of Blackwell Futura Media Services (BFMS) and SHM. BFMS is accredited by ACCME to provide CME for physicians.

HM12 registration is available at www.hospitalmedicine2012.org until March 5. SHM also permits walk-up registration at the San Diego Convention Center.

BFMS designates the educational activity for SHM’s annual meeting at a maximum of 19.75 Category 1 credits toward the AMA Physician’s Recognition Award. Each physician should claim only those hours of credit they actually spend in each educational activity. BFMS has designated a credit schedule for HM12’s pre-courses on April 1 as follows:

- ABIM MOC learning session, 6.5 credits;

- Advanced Interactive Critical Care, 7.75 credits;

- CMS’s Value-Based Purchasing Program, 3.75 credits;

- Medical Procedures, 7.5 credits;

- Portable Ultrasounds, 3.75 credits;

- Perioperative Medicine, 7.75 credits; and

- Practice Management, 7.5 credits.

Source: www.hospitalmedicine.org

HM12 Organizers Strive for ‘Meaningful’ Educational Offerings for Hospitalists

Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, has been going to SHM’s annual meetings for a decade. He’s played the part of poster presenter, session leader, physician editor of The Hospitalist, and even just a healthcare consumer eager to hear what a keynote speaker has to say.

This year, he’s added a new title: HM12 course director. The sobriquet has given him a new appreciation for the work that goes into the four-day summit, April 1-4 at the San Diego Convention Center.

“It’s been a great experience to see how much work really goes into these meetings behind the scenes and how thoughtful people are to try to program content that all different types of hospitalists would be interested in,” says Dr. Glasheen, associate professor of medicine and director of the hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado Denver. “Trying to target enough stuff so that it’s meaningful for everybody ends up being incredibly challenging.”

The challenge is important because continuing medical education (CME) arguably is the biggest draw for the annual meeting. From pre-courses offering Category 1 credits toward the AMA Physician’s Recognition Award to rapid-fire sessions offering “Jeopardy!”-like chances to test current knowledge, a majority of past attendees say CME and pedagogy keep them coming back.

“It’s one of the top reasons people come, and it should be,” Dr. Glasheen adds. “This is the opportunity for people to come and hear new ideas. And I don’t mean that just in terms of clinical medicine, but also nonclinical medicine. This is our opportunity to pull ourselves out of the weeds … and really get a sense of what’s coming down the pike.”

Dr. Glasheen and assistant course director Michael Pistoria, DO, FACP, SFHM, say the goals of each year’s offerings are to keep things current and user-friendly.

—Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, HM12 course director

Take “How to Improve Performance in CMS’s Value-Based Purchasing Program,” a debut pre-course designed as a primer for the new VBP rules going into effect Oct. 1. The session is led by SHM’s senior vice president and chief solutions officer Joseph Miller and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La. The new pre-course joins the now well-established American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) course as one of the sessions that, although they didn’t exist a few years ago, are viewed as crucial to the specialty’s future development.

“It’s the natural evolution of what hospitalists do,” Dr. Glasheen says. “If we went back to the first year of this meeting, it was primarily a clinical meeting. But I think over time, just as my role as a hospitalist has evolved over 10 years, so has the society’s annual meeting. Yes, we have the clinical core that everybody needs. But there’s a lot of other stuff that’s happening in the world around us—including healthcare policy, payment reform—and we need to know about those things.”

Constant change to the HM12 course menu keeps things fresh, says Dr. Pistoria, HM13’s course director, who works at Lehigh Valley Health Network in Allentown, Pa. “Quite frankly, it allows us to some degree to keep the faculty fresh as well,” he says. “If you give them a year off, they come back fully charged with new ideas. Even if it’s the same information, maybe they’ve got some new ideas of how to present it.”

Another area where the importance of the meeting’s educational offerings becomes self-evident is the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition. The popularity of the competition continues to grow; the review committee was deluged with 200 more submissions for HM12 than for HM11. Organizers felt that was too many posters to give attendees enough quality time with their presenters, so the session has been expanded and broken up into two sessions—one for Research and Innovations (Monday, April 2, 5-7 p.m.), and one for Vignettes (Tuesday, April 3, noon-1:30 p.m.).

“It speaks to the fact that academic hospital medicine is really growing up,” Dr. Glasheen says. “Ten years ago, we were all just trying to get enough docs to take care of patients. Now we’re getting to the point where academic hospitalists really can develop a career as a scholar and a researcher.”

An educational twist to this year’s meeting is an approach called “Pathways.” The tack is an online map of interrelated courses that may appear in different categorical tracks. For example, the “pathway” highlights for attendees how they can find sessions devoted to early-career hospitalist issues, palliative care, or transitions of care. So if two people from one institution wanted to break up the sessions by a topic, they now have an easier way.

“It affords people the opportunity to plan,” Dr. Pistoria says. “And again, it keeps us fresh. As the annual meeting committee, we’re constantly looking: What can we do what can we do differently? What can we do better?”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, has been going to SHM’s annual meetings for a decade. He’s played the part of poster presenter, session leader, physician editor of The Hospitalist, and even just a healthcare consumer eager to hear what a keynote speaker has to say.

This year, he’s added a new title: HM12 course director. The sobriquet has given him a new appreciation for the work that goes into the four-day summit, April 1-4 at the San Diego Convention Center.

“It’s been a great experience to see how much work really goes into these meetings behind the scenes and how thoughtful people are to try to program content that all different types of hospitalists would be interested in,” says Dr. Glasheen, associate professor of medicine and director of the hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado Denver. “Trying to target enough stuff so that it’s meaningful for everybody ends up being incredibly challenging.”

The challenge is important because continuing medical education (CME) arguably is the biggest draw for the annual meeting. From pre-courses offering Category 1 credits toward the AMA Physician’s Recognition Award to rapid-fire sessions offering “Jeopardy!”-like chances to test current knowledge, a majority of past attendees say CME and pedagogy keep them coming back.

“It’s one of the top reasons people come, and it should be,” Dr. Glasheen adds. “This is the opportunity for people to come and hear new ideas. And I don’t mean that just in terms of clinical medicine, but also nonclinical medicine. This is our opportunity to pull ourselves out of the weeds … and really get a sense of what’s coming down the pike.”

Dr. Glasheen and assistant course director Michael Pistoria, DO, FACP, SFHM, say the goals of each year’s offerings are to keep things current and user-friendly.

—Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, HM12 course director

Take “How to Improve Performance in CMS’s Value-Based Purchasing Program,” a debut pre-course designed as a primer for the new VBP rules going into effect Oct. 1. The session is led by SHM’s senior vice president and chief solutions officer Joseph Miller and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La. The new pre-course joins the now well-established American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) course as one of the sessions that, although they didn’t exist a few years ago, are viewed as crucial to the specialty’s future development.

“It’s the natural evolution of what hospitalists do,” Dr. Glasheen says. “If we went back to the first year of this meeting, it was primarily a clinical meeting. But I think over time, just as my role as a hospitalist has evolved over 10 years, so has the society’s annual meeting. Yes, we have the clinical core that everybody needs. But there’s a lot of other stuff that’s happening in the world around us—including healthcare policy, payment reform—and we need to know about those things.”

Constant change to the HM12 course menu keeps things fresh, says Dr. Pistoria, HM13’s course director, who works at Lehigh Valley Health Network in Allentown, Pa. “Quite frankly, it allows us to some degree to keep the faculty fresh as well,” he says. “If you give them a year off, they come back fully charged with new ideas. Even if it’s the same information, maybe they’ve got some new ideas of how to present it.”

Another area where the importance of the meeting’s educational offerings becomes self-evident is the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition. The popularity of the competition continues to grow; the review committee was deluged with 200 more submissions for HM12 than for HM11. Organizers felt that was too many posters to give attendees enough quality time with their presenters, so the session has been expanded and broken up into two sessions—one for Research and Innovations (Monday, April 2, 5-7 p.m.), and one for Vignettes (Tuesday, April 3, noon-1:30 p.m.).

“It speaks to the fact that academic hospital medicine is really growing up,” Dr. Glasheen says. “Ten years ago, we were all just trying to get enough docs to take care of patients. Now we’re getting to the point where academic hospitalists really can develop a career as a scholar and a researcher.”

An educational twist to this year’s meeting is an approach called “Pathways.” The tack is an online map of interrelated courses that may appear in different categorical tracks. For example, the “pathway” highlights for attendees how they can find sessions devoted to early-career hospitalist issues, palliative care, or transitions of care. So if two people from one institution wanted to break up the sessions by a topic, they now have an easier way.

“It affords people the opportunity to plan,” Dr. Pistoria says. “And again, it keeps us fresh. As the annual meeting committee, we’re constantly looking: What can we do what can we do differently? What can we do better?”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, has been going to SHM’s annual meetings for a decade. He’s played the part of poster presenter, session leader, physician editor of The Hospitalist, and even just a healthcare consumer eager to hear what a keynote speaker has to say.

This year, he’s added a new title: HM12 course director. The sobriquet has given him a new appreciation for the work that goes into the four-day summit, April 1-4 at the San Diego Convention Center.

“It’s been a great experience to see how much work really goes into these meetings behind the scenes and how thoughtful people are to try to program content that all different types of hospitalists would be interested in,” says Dr. Glasheen, associate professor of medicine and director of the hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado Denver. “Trying to target enough stuff so that it’s meaningful for everybody ends up being incredibly challenging.”

The challenge is important because continuing medical education (CME) arguably is the biggest draw for the annual meeting. From pre-courses offering Category 1 credits toward the AMA Physician’s Recognition Award to rapid-fire sessions offering “Jeopardy!”-like chances to test current knowledge, a majority of past attendees say CME and pedagogy keep them coming back.

“It’s one of the top reasons people come, and it should be,” Dr. Glasheen adds. “This is the opportunity for people to come and hear new ideas. And I don’t mean that just in terms of clinical medicine, but also nonclinical medicine. This is our opportunity to pull ourselves out of the weeds … and really get a sense of what’s coming down the pike.”

Dr. Glasheen and assistant course director Michael Pistoria, DO, FACP, SFHM, say the goals of each year’s offerings are to keep things current and user-friendly.

—Jeff Glasheen, MD, SFHM, HM12 course director

Take “How to Improve Performance in CMS’s Value-Based Purchasing Program,” a debut pre-course designed as a primer for the new VBP rules going into effect Oct. 1. The session is led by SHM’s senior vice president and chief solutions officer Joseph Miller and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La. The new pre-course joins the now well-established American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) course as one of the sessions that, although they didn’t exist a few years ago, are viewed as crucial to the specialty’s future development.

“It’s the natural evolution of what hospitalists do,” Dr. Glasheen says. “If we went back to the first year of this meeting, it was primarily a clinical meeting. But I think over time, just as my role as a hospitalist has evolved over 10 years, so has the society’s annual meeting. Yes, we have the clinical core that everybody needs. But there’s a lot of other stuff that’s happening in the world around us—including healthcare policy, payment reform—and we need to know about those things.”

Constant change to the HM12 course menu keeps things fresh, says Dr. Pistoria, HM13’s course director, who works at Lehigh Valley Health Network in Allentown, Pa. “Quite frankly, it allows us to some degree to keep the faculty fresh as well,” he says. “If you give them a year off, they come back fully charged with new ideas. Even if it’s the same information, maybe they’ve got some new ideas of how to present it.”

Another area where the importance of the meeting’s educational offerings becomes self-evident is the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition. The popularity of the competition continues to grow; the review committee was deluged with 200 more submissions for HM12 than for HM11. Organizers felt that was too many posters to give attendees enough quality time with their presenters, so the session has been expanded and broken up into two sessions—one for Research and Innovations (Monday, April 2, 5-7 p.m.), and one for Vignettes (Tuesday, April 3, noon-1:30 p.m.).

“It speaks to the fact that academic hospital medicine is really growing up,” Dr. Glasheen says. “Ten years ago, we were all just trying to get enough docs to take care of patients. Now we’re getting to the point where academic hospitalists really can develop a career as a scholar and a researcher.”

An educational twist to this year’s meeting is an approach called “Pathways.” The tack is an online map of interrelated courses that may appear in different categorical tracks. For example, the “pathway” highlights for attendees how they can find sessions devoted to early-career hospitalist issues, palliative care, or transitions of care. So if two people from one institution wanted to break up the sessions by a topic, they now have an easier way.

“It affords people the opportunity to plan,” Dr. Pistoria says. “And again, it keeps us fresh. As the annual meeting committee, we’re constantly looking: What can we do what can we do differently? What can we do better?”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

HM12’s Host City of San Diego Offers Plenty of Fun Things to Do

Clinical updates, plenary addresses from D.C. heavyweights, and special-interest forums—sure, those are necessary parts of SHM’s annual meeting in San Diego.

But a local hospitalist’s favorite restaurant? That’s downright important.

“You know, I’d have to say my son and I’s is Casa Guadalajara in Old Town,” says Pedro Ramos, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California at San Diego. “He loves the bean burritos. It’s sort of a slower pace, so when you go, it’s going to take some time, but the food’s really good.”

HM12 is a perfect chance to learn about San Diego. (Did you know it is the eighth-largest city in the U.S., with 1.3 million residents?) San Diego offers a plethora of attractions for those with time to explore, and the San Diego Convention Center’s location—along San Diego Bay—is a big reason why (as is the average high temperature: 68 degrees in April). Hospitalists and their families will be within walking distance of:

- The Gaslamp Quarter, a national historic district and entertainment destination. The trendy neighborhood offers scores of dining options, from elbows-on-the-table relaxation to white-linen prix fixe.

- Petco Park, the baseball stadium for the San Diego Padres. The team plays its home opener on April 4, the start of a four-game series with the rival Los Angeles Dodgers.

- Just north of the village are two museums of note for sailors: the USS Midway Museum and the Maritime Museum of San Diego. The USS Midway offers tours of an aircraft carrier; MMSD visitors experience the world’s oldest active ship, the Star of India.

- Coronado: A ferry brings visitors and locals alike to a luxury resort area whose name in Spanish means “the crowned one.” Sometimes called Coronado Island—though the land mass is technically a peninsula—visitors can rent bikes to tour its streets. A particular highlight is Hotel Del Coronado, built in 1888 and now a historic landmark. The property has been featured in major motion pictures, including the Marilyn Monroe classic “Some Like it Hot.”

—Pedro Ramos, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine, University of California at San Diego

And that’s just the pedestrian-friendly parts of the city. Board a trolley, a pedi-cab, or a light-rail train, and Dr. Ramos says a few other jewels are a few minutes away.

First up is Old Town San Diego, where Dr. Ramos and his son go for those burritos. The neighborhood is a mix of historic buildings, eateries, and two of the city’s best-known recreation areas: Old Town San Diego State Historic Park and Presidio Park.

Second, and perhaps more prized to Dr. Ramos, is the city’s namesake zoo and its environs. “It’s a short cab ride away,” he says, “and it’s connected to Balboa Park, which has these great museums, a huge park, lots of beautiful things to see there.”

To get involved, visit www.hospitalmedicine2012.org/family_activities

Clinical updates, plenary addresses from D.C. heavyweights, and special-interest forums—sure, those are necessary parts of SHM’s annual meeting in San Diego.

But a local hospitalist’s favorite restaurant? That’s downright important.

“You know, I’d have to say my son and I’s is Casa Guadalajara in Old Town,” says Pedro Ramos, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California at San Diego. “He loves the bean burritos. It’s sort of a slower pace, so when you go, it’s going to take some time, but the food’s really good.”

HM12 is a perfect chance to learn about San Diego. (Did you know it is the eighth-largest city in the U.S., with 1.3 million residents?) San Diego offers a plethora of attractions for those with time to explore, and the San Diego Convention Center’s location—along San Diego Bay—is a big reason why (as is the average high temperature: 68 degrees in April). Hospitalists and their families will be within walking distance of:

- The Gaslamp Quarter, a national historic district and entertainment destination. The trendy neighborhood offers scores of dining options, from elbows-on-the-table relaxation to white-linen prix fixe.

- Petco Park, the baseball stadium for the San Diego Padres. The team plays its home opener on April 4, the start of a four-game series with the rival Los Angeles Dodgers.

- Just north of the village are two museums of note for sailors: the USS Midway Museum and the Maritime Museum of San Diego. The USS Midway offers tours of an aircraft carrier; MMSD visitors experience the world’s oldest active ship, the Star of India.

- Coronado: A ferry brings visitors and locals alike to a luxury resort area whose name in Spanish means “the crowned one.” Sometimes called Coronado Island—though the land mass is technically a peninsula—visitors can rent bikes to tour its streets. A particular highlight is Hotel Del Coronado, built in 1888 and now a historic landmark. The property has been featured in major motion pictures, including the Marilyn Monroe classic “Some Like it Hot.”

—Pedro Ramos, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine, University of California at San Diego

And that’s just the pedestrian-friendly parts of the city. Board a trolley, a pedi-cab, or a light-rail train, and Dr. Ramos says a few other jewels are a few minutes away.

First up is Old Town San Diego, where Dr. Ramos and his son go for those burritos. The neighborhood is a mix of historic buildings, eateries, and two of the city’s best-known recreation areas: Old Town San Diego State Historic Park and Presidio Park.

Second, and perhaps more prized to Dr. Ramos, is the city’s namesake zoo and its environs. “It’s a short cab ride away,” he says, “and it’s connected to Balboa Park, which has these great museums, a huge park, lots of beautiful things to see there.”

To get involved, visit www.hospitalmedicine2012.org/family_activities

Clinical updates, plenary addresses from D.C. heavyweights, and special-interest forums—sure, those are necessary parts of SHM’s annual meeting in San Diego.

But a local hospitalist’s favorite restaurant? That’s downright important.

“You know, I’d have to say my son and I’s is Casa Guadalajara in Old Town,” says Pedro Ramos, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California at San Diego. “He loves the bean burritos. It’s sort of a slower pace, so when you go, it’s going to take some time, but the food’s really good.”

HM12 is a perfect chance to learn about San Diego. (Did you know it is the eighth-largest city in the U.S., with 1.3 million residents?) San Diego offers a plethora of attractions for those with time to explore, and the San Diego Convention Center’s location—along San Diego Bay—is a big reason why (as is the average high temperature: 68 degrees in April). Hospitalists and their families will be within walking distance of:

- The Gaslamp Quarter, a national historic district and entertainment destination. The trendy neighborhood offers scores of dining options, from elbows-on-the-table relaxation to white-linen prix fixe.

- Petco Park, the baseball stadium for the San Diego Padres. The team plays its home opener on April 4, the start of a four-game series with the rival Los Angeles Dodgers.

- Just north of the village are two museums of note for sailors: the USS Midway Museum and the Maritime Museum of San Diego. The USS Midway offers tours of an aircraft carrier; MMSD visitors experience the world’s oldest active ship, the Star of India.

- Coronado: A ferry brings visitors and locals alike to a luxury resort area whose name in Spanish means “the crowned one.” Sometimes called Coronado Island—though the land mass is technically a peninsula—visitors can rent bikes to tour its streets. A particular highlight is Hotel Del Coronado, built in 1888 and now a historic landmark. The property has been featured in major motion pictures, including the Marilyn Monroe classic “Some Like it Hot.”

—Pedro Ramos, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine, University of California at San Diego

And that’s just the pedestrian-friendly parts of the city. Board a trolley, a pedi-cab, or a light-rail train, and Dr. Ramos says a few other jewels are a few minutes away.

First up is Old Town San Diego, where Dr. Ramos and his son go for those burritos. The neighborhood is a mix of historic buildings, eateries, and two of the city’s best-known recreation areas: Old Town San Diego State Historic Park and Presidio Park.

Second, and perhaps more prized to Dr. Ramos, is the city’s namesake zoo and its environs. “It’s a short cab ride away,” he says, “and it’s connected to Balboa Park, which has these great museums, a huge park, lots of beautiful things to see there.”

To get involved, visit www.hospitalmedicine2012.org/family_activities

Welcome to San Diego for HM12

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

Wachter to Examine ‘Great Physicians’ at HM12

Let’s face it: Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has a way with words.

The man who co-dubbed the term “hospitalist” has used his vocabulary wisely in his career, from his day jobs as professor and chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine and chief of the medical service at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center to his appointment as a 2012 Fulbright Scholar, which took him to London, to his nascent title of chair-elect for the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM).

And yet the author of the HM blog Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld.com) might best be known for the penultimate address he delivers at SHM’s annual meeting. This year he takes center stage at the San Diego Convention Center at noon April 4, capping HM12.

So, without further adieu, Dr. Wachter, in his own words:

—Robert Wachter, MD, MHM

- On how to keep his talks fresh after nearly 15 years: “It’s increasingly a struggle. One of the things that’s fun about the hospitalist field is that we are so linked to the changes in the world of healthcare, both having to pay a lot of attention to them and, to some extent, leading them. As long as the world of healthcare changes, there’s new content.”

- On his HM12 address, “The Great Physician, Circa 2012”: How Hospitalists Must Lead Efforts to Identify and Become This New Breed”: “I’ve been thinking more and more about the role of individual physicians. Part of that is opportunistic, in that I’m becoming the chair of the ABIM in July. If you’re in charge of the largest accreditation group for doctors, certainly in the county, you have to think pretty deeply about what is good and competent, and what does a great physician look like? … That line of thinking got me to then settle on a theme for this year: What does the great physician in 2012 look like? How do we train such a person? What is the mental model for that person? And how do we ensure in our field that we are both producing those people and creating a field and a professional society that encourages them and nurtures them and ensures that we are at the cutting edge?”

- On what a great hospitalist looks like in 2012: “A great hospitalist will welcome accountability and measurement and transparency. He or she will be absolutely comfortable being a member of, and a leader of, or a nonleader of, high-functioning teams. He or she will be comfortable with working through some challenging questions about what things do I need to do versus what things can others do more effectively, or as effectively, but at a lower cost. The great hospitalist now and the great doctor in the future will recognize that delivering high-quality, safe, and patient-centric care that is agnostic about how much that case costs is no longer ethical.”

- On where HM stands in its evolution as a specialty: “I’ve talked before about our field being in its adolescence. We’re rapidly reaching the adult phase where the kind of slack you gave your kid or even your teenager for transgressions, well, no one’s going to give us anymore.

- On what leadership looks like in the face of generational healthcare reform: “We should be the canaries in the coal mine, the first ones to notice that there are important changes afoot. We’ll also be the first ones that feel pressures to change ourselves in response to these forces. And the first ones to really lead the charge. I think we saw that a decade ago, with respect to safety and quality. I think we also saw it when we embraced the importance of coordination of care and communication and teamwork.”

Let’s face it: Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has a way with words.

The man who co-dubbed the term “hospitalist” has used his vocabulary wisely in his career, from his day jobs as professor and chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine and chief of the medical service at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center to his appointment as a 2012 Fulbright Scholar, which took him to London, to his nascent title of chair-elect for the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM).

And yet the author of the HM blog Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld.com) might best be known for the penultimate address he delivers at SHM’s annual meeting. This year he takes center stage at the San Diego Convention Center at noon April 4, capping HM12.

So, without further adieu, Dr. Wachter, in his own words:

—Robert Wachter, MD, MHM

- On how to keep his talks fresh after nearly 15 years: “It’s increasingly a struggle. One of the things that’s fun about the hospitalist field is that we are so linked to the changes in the world of healthcare, both having to pay a lot of attention to them and, to some extent, leading them. As long as the world of healthcare changes, there’s new content.”

- On his HM12 address, “The Great Physician, Circa 2012”: How Hospitalists Must Lead Efforts to Identify and Become This New Breed”: “I’ve been thinking more and more about the role of individual physicians. Part of that is opportunistic, in that I’m becoming the chair of the ABIM in July. If you’re in charge of the largest accreditation group for doctors, certainly in the county, you have to think pretty deeply about what is good and competent, and what does a great physician look like? … That line of thinking got me to then settle on a theme for this year: What does the great physician in 2012 look like? How do we train such a person? What is the mental model for that person? And how do we ensure in our field that we are both producing those people and creating a field and a professional society that encourages them and nurtures them and ensures that we are at the cutting edge?”

- On what a great hospitalist looks like in 2012: “A great hospitalist will welcome accountability and measurement and transparency. He or she will be absolutely comfortable being a member of, and a leader of, or a nonleader of, high-functioning teams. He or she will be comfortable with working through some challenging questions about what things do I need to do versus what things can others do more effectively, or as effectively, but at a lower cost. The great hospitalist now and the great doctor in the future will recognize that delivering high-quality, safe, and patient-centric care that is agnostic about how much that case costs is no longer ethical.”

- On where HM stands in its evolution as a specialty: “I’ve talked before about our field being in its adolescence. We’re rapidly reaching the adult phase where the kind of slack you gave your kid or even your teenager for transgressions, well, no one’s going to give us anymore.

- On what leadership looks like in the face of generational healthcare reform: “We should be the canaries in the coal mine, the first ones to notice that there are important changes afoot. We’ll also be the first ones that feel pressures to change ourselves in response to these forces. And the first ones to really lead the charge. I think we saw that a decade ago, with respect to safety and quality. I think we also saw it when we embraced the importance of coordination of care and communication and teamwork.”

Let’s face it: Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has a way with words.

The man who co-dubbed the term “hospitalist” has used his vocabulary wisely in his career, from his day jobs as professor and chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine and chief of the medical service at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center to his appointment as a 2012 Fulbright Scholar, which took him to London, to his nascent title of chair-elect for the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM).

And yet the author of the HM blog Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld.com) might best be known for the penultimate address he delivers at SHM’s annual meeting. This year he takes center stage at the San Diego Convention Center at noon April 4, capping HM12.

So, without further adieu, Dr. Wachter, in his own words:

—Robert Wachter, MD, MHM

- On how to keep his talks fresh after nearly 15 years: “It’s increasingly a struggle. One of the things that’s fun about the hospitalist field is that we are so linked to the changes in the world of healthcare, both having to pay a lot of attention to them and, to some extent, leading them. As long as the world of healthcare changes, there’s new content.”

- On his HM12 address, “The Great Physician, Circa 2012”: How Hospitalists Must Lead Efforts to Identify and Become This New Breed”: “I’ve been thinking more and more about the role of individual physicians. Part of that is opportunistic, in that I’m becoming the chair of the ABIM in July. If you’re in charge of the largest accreditation group for doctors, certainly in the county, you have to think pretty deeply about what is good and competent, and what does a great physician look like? … That line of thinking got me to then settle on a theme for this year: What does the great physician in 2012 look like? How do we train such a person? What is the mental model for that person? And how do we ensure in our field that we are both producing those people and creating a field and a professional society that encourages them and nurtures them and ensures that we are at the cutting edge?”

- On what a great hospitalist looks like in 2012: “A great hospitalist will welcome accountability and measurement and transparency. He or she will be absolutely comfortable being a member of, and a leader of, or a nonleader of, high-functioning teams. He or she will be comfortable with working through some challenging questions about what things do I need to do versus what things can others do more effectively, or as effectively, but at a lower cost. The great hospitalist now and the great doctor in the future will recognize that delivering high-quality, safe, and patient-centric care that is agnostic about how much that case costs is no longer ethical.”

- On where HM stands in its evolution as a specialty: “I’ve talked before about our field being in its adolescence. We’re rapidly reaching the adult phase where the kind of slack you gave your kid or even your teenager for transgressions, well, no one’s going to give us anymore.

- On what leadership looks like in the face of generational healthcare reform: “We should be the canaries in the coal mine, the first ones to notice that there are important changes afoot. We’ll also be the first ones that feel pressures to change ourselves in response to these forces. And the first ones to really lead the charge. I think we saw that a decade ago, with respect to safety and quality. I think we also saw it when we embraced the importance of coordination of care and communication and teamwork.”

How Should Acute Alcoholic Hepatitis be Treated?

Case

A 53-year-old man with a history of daily alcohol use presents with one week of jaundice. His blood pressure is 95/60 mmHg, pulse 105/minute, and temperature 38.0°C. Examination discloses icterus, ascites, and an enlarged, tender liver. His bilirubin is 9 mg/dl, AST 250 IU/dL, ALT 115 IU/dL, prothromin time 22 seconds, INR 2.7, creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, and leukocyte count 15,000/cu mm with 70% neutrophils. He is admitted with a diagnosis of acute alcoholic hepatitis. How should he be treated?

Background

Hospitalists frequently encounter patients who use alcohol and have abnormal liver tests. Regular, heavy alcohol consumption is associated with a variety of forms of liver disease, including fatty liver, inflammation, hepatic fibrosis, and cirrhosis. The term “alcoholic hepatitis” describes a more severe form of alcohol-related liver disease associated with significant short-term mortality.

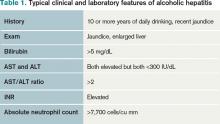

Alcoholic hepatitis typically occurs after more than 10 years of regular heavy alcohol use; average consumption in one study was 100 g/day (the equivalent of 10 drinks per day).1 The typical patient presents with recent onset of jaundice, ascites, and proximal muscle loss. Fever and leukocytosis also are common but should prompt an evaluation for infection, especially spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver biopsy in these patients shows steatosis, swollen hepatocytes containing eosinophilic inclusion (Mallory) bodies, and a prominent neutrophilic inflammatory cell infiltrate. Because of the accuracy of clinical diagnosis, biopsy is rarely required, relying instead on clinical and laboratory features for diagnosis (see Table 1, below).

Prognosis can be determined with prediction models. The most common are Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and Maddrey’s discriminate score (see Table 2). Several websites allow quick calculation of these scores and provide estimated 30-day or 90-day mortality. These scores can be used to guide therapy.

Review of the Data

How should hospitalists treat this serious illness? The evidence-based literature supporting the efficacy of treatments for alcoholic hepatitis is limited, and expert opinions sometimes conflict.

Abstinence has been shown to improve survival in all stages of alcohol-related liver disease.2 This can be accomplished by admitting this patient population to the hospital. A number of interventions and therapies are available to increase the chance of continued abstinence following discharge (see Table 3).

Nutritional support. Protein-calorie malnutrition is seen in up to 90% of patients with cirrhosis.3 The cause of malnutrition in these patients includes decreased caloric intake, metabolic derangements that accompany liver disease, and micronutrient and vitamin deficiencies. Many of these patients rely almost solely on alcohol for caloric intake; this contributes to potassium depletion, which is frequently seen. After admission, these patients are often evaluated for other conditions (such as gastrointestinal bleeding and altered mental status) that require them to be NPO overnight, thus further confounding their malnutrition. Enteral nutritional support was shown in a multicenter study to be associated with reduced infectious complications and improved one-year mortality.4

Little clinical data support specific recommendations for the amount of nutritional support. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends 35 calories/kg to 40 calories/kg of body weight per day and a protein intake of 1.2 g/kg to 1.5g/kg per day.5 In an average, 70-kg patient, this is 2,450 to 2,800 calories a day. For patients who are not able to meet these nutritional needs by mouth, enteral feeding with a small-bore (Dobhoff) feeding tube can be used, even in patients with known esophageal varices.

Most of these patients have anorexia and nausea and do not meet these caloric recommendations by eating. Nutritional support is a low-risk intervention that can be provided on almost all inpatient medical care areas. Hospitalists should be attentive to nutritional support early in the hospitalization of these patients.

Corticosteroid therapy is recommended by the ACG for patients with alcoholic hepatitis and a Maddrey’s discriminant function greater than 32.5 There is much debate about this recommendation, as conflicting data about efficacy exist.

A 2008 Cochrane review included clinical trials published before July 2007 that examined corticosteroid use in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. A total of 15 trials with 721 randomized patients were included. The review concluded that corticosteroids did not statistically reduce mortality compared with placebo or no intervention; however, mortality was reduced in the subgroup of patients with Maddrey’s scores greater than 32 and hepatic encephalopathy.6 The review concluded that current evidence does not support the use of corticosteroids in alcoholic hepatitis, and more randomized trials were needed.

Another meta-analysis demonstrated a mortality benefit when the largest studies, which included 221 patients with high Maddrey’s scores, were analyzed separately.7 Contraindications to corticosteroid treatment include active infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute pancreatitis, and renal failure. Other concerns about corticosteroids include potential adverse reactions (hyperglycemia) and increased risk of infection. Prednisolone is preferred over prednisone because it is the active drug. The recommended dosage is 40 mg/day for 28 days followed by a taper (20 mg/day for one week, then 10 mg/day for one week).

Some data suggest that if patients on corticosteroid therapy do not demonstrate a decrease in their bilirubin levels by Day 7, they are at higher risk of developing infections, have a poorer prognosis, and that corticosteroid therapy should be stopped.8 Some experts use the Lille model to decide whether to continue corticosteroids. In one study, patients who did not respond to prednisolone did not improve when switched to pentoxifyline.9

Patients discharged on corticosteroids require very careful coordination with outpatient providers as prolonged corticosteroid treatment courses can lead to serious complications and death. Critics of corticosteroid therapy in these patients often cite problems related to prolonged steroid use, especially in patients who do not respond to therapy.10

Pentoxifylline, an oral phosphodiesterase inhibitor, is recommended by the ACG, especially if corticosteroids are contraindicated.5 In 2008, 101 patients with alcoholic hepatitis were enrolled in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing pentoxifylline and placebo. This study demonstrated that patients who received pentoxifylline had decreased 28-day mortality (24.6% versus 46% receiving placebo). Of those patients who died during the study, only 50% (versus 91% in the placebo group) developed hepatorenal syndrome.11 However, a Cochrane review of all studies with pentoxifylline concluded that no firm conclusions could be drawn.12

One small, randomized trial comparing pentoxifylline with prednisolone demonstrated that pentoxifylline was superior.13 Pentoxifylline can be prescribed to patients who have contraindications to corticosteroid use (infection or gastrointestinal bleeding). The recommended dose is 400 mg orally three times daily (TID) for four weeks. Common side effects are nausea and vomiting. Pentoxifylline cannot be administered by nasogastric tubes and should not be used in patients with recent cerebral or retinal hemorrhage.

Other therapies. Several studies have examined vitamin E, N-acetylcystine, and other antioxidants as treatment for alcoholic hepatitis. No clear benefit has been demonstrated for any of these drugs. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors (e.g. infliximab) have been studied, but increased mortality was demonstrated and these studies were discontinued. Patients are not usually considered for liver transplantation until they have at least six months of abstinence from alcohol as recommended by the American Society of Transplantation.14

Discharge considerations. No clinical trials have studied optimal timing of discharge. Expert opinion based on clinical experience recommends that patients be kept in the hospital until they are eating, signs of alcohol withdrawal and encephalopathy are absent, and bilirubin is less than 10 mg/dL.14 These patients often are quite sick and hospitalization frequently exceeds 10 days. Careful outpatient follow-up and assistance with continued abstinence is very important.

Back to the Case

The patient fits the typical clinical picture of alcoholic hepatitis. Cessation of alcohol consumption is the most important treatment and is accomplished by admission to the hospital. Because of his daily alcohol consumption, folate, thiamine, multivitamins, and oral vitamin K are ordered. Though he has no symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, a note is added about potential withdrawal to the handoff report.

An infectious workup is completed by ordering blood and urine cultures, a chest X-ray, and performing paracentesis to exclude spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A dietary consult with calorie count is given, along with a plan to discuss with the patient the importance of consuming at least 2,500 calories a day is made. Tube feedings will be considered if the patient does not meet this goal in 48 hours. Clinical calculators determine his Maddrey’s and MELD scores (50 and 25, respectively). If he is actively bleeding or infected, pentoxifylline (400 mg TID for 28 days) is favored due to its lower-side-effect profile.

His MELD score predicts a 90-day mortality of 43%; a meeting is planned to discuss code status and end-of-life issues with the patient and his family. Due to the severity of his illness, a gastroenterology consultation is recommended.

Bottom Line

Alcoholic hepatitis is a serious disease with significant short-term mortality. Treatment options are limited but include abstinence from alcohol, supplemental nutrition, and, for select patients, pentoxifylline or corticosteroids. Because most transplant centers require six months of abstinence, these patients usually are not eligible for urgent liver transplantation.

Dr. Parada is a clinical instructor and chief medical resident in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and the University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque. Dr. Pierce is associate professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and the University of New Mexico Hospital.

References

- Naveau S, Giraud V, Borotto E, Aubert A, Capron F, Chaput JC. Excess weight risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;25:108-111.

- Pessione F, Ramond MJ, Peters L, et al. Five-year survival predictive factors in patients with excessive alcohol intake and cirrhosis. Effect of alcoholic hepatitis, smoking and abstinence. Liver Int. 2003;23:45-53.

- Mendenhall CL, Anderson S, Weesner RE, Goldberg SJ, Crolic KA. Protein-calorie malnutrition associated with alcoholic hepatitis. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Med. 1984;76:211-222.

- Cabre E, Rodriguez-Iglesias P, Caballeria J, et al. Short- and long-term outcome of severe alcohol-induced hepatitis treated with steroids or enteral nutrition: a multicenter randomized trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:36-42.

- O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:307-328.

- Rambaldi A, Saconato HH, Christensen E, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Systematic review: Glucocorticosteroids for alcoholic hepatitis—a Cochrane hepato-biliary group systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomized clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1167-1178.

- Mathurin P, Mendenhall CL, Carithers RL Jr., et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH): individual data analysis of the last three randomized placebo controlled double blind trials of corticosteroids in severe AH. J Hepatol. 2002;36:480-487.

- Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, et al. The Lille model: A new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology. 2007;45:1348-1354.

- Louvet A, Diaz E, Dharancy S, et al. Early switch topentoxifylline in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis is inefficient in non-responders to corticosteroids. J Hepatol. 2008;48:465-470.

- Amini M, Runyon BA. Alcoholic hepatitis 2010: A clinician’s guide to diagnosis and therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4905-4912.

- Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1637-1648.

- Whitfield K, Rambaldi A, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD007339.

- De BK, Gangopadhyay S, Dutta D, Baksi SD, Pani A, Ghosh P. Pentoxifylline versus prednisolone for severe alcoholic hepatitis: A randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1613-1619.