User login

Geographic tongue

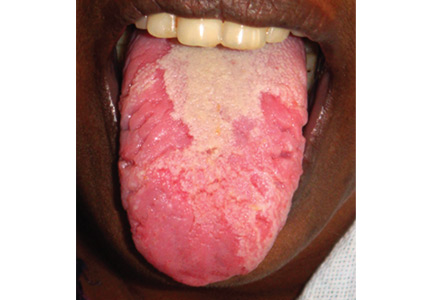

A previously healthy 35-year-old woman presented with reddish discoloration of her tongue for the past 7 days, accompanied by mild soreness over the area when eating spicy foods. The lesion had also changed shape repeatedly. She denied any other local or systemic symptoms.

Lingual examination showed clearly delineated areas of shiny, erythematous mucosa on the dorsal and lateral aspects of the tongue, surrounded by white borders (Figure 1). Examination of the throat and oral cavity were unremarkable. All other systemic examinations were normal. Laboratory testing showed a normal hemogram, blood glucose, and metabolic profile.

These findings were suggestive of geographic tongue, a benign, self-limiting inflammation. The patient was reassured of the benign nature of the condition and was advised to avoid spicy food until resolution of the lesion. A follow-up examination 1 month later showed complete healing of the lesion.

A COMMON, BENIGN, SELF-LIMITING MUCOSAL CONDITION

Geographic tongue—also known as benign migratory glossitis and lingual erythema migrans—is commonly seen in daily practice, with a prevalence of 2% to 3% in the general population.1 In the United States, the condition is more prevalent in whites and blacks than in Hispanics, but has no association with age or sex.

This condition is characterized by circinate, maplike areas of erythema surrounded by well-demarcated scalloped white borders, typically on the dorsum and the lateral borders of the tongue.2 The appearance, which represents loss of filiform papillae (depapillation) from the lingual mucosa, can change in size, shape, or location in a matter of minutes or hours. The name “lingual erythema migrans” reflects the changing clinical picture.3 Rarely, the labial or palatal mucosa is affected.

POSTULATED TO BE AN INTRAORAL FORM OF PSORIASIS

The precise etiology remains obscure.2 Histopathologically, geographic tongue is characterized by hyperparakeratosis and acanthosis resembling psoriasis. Hence, it has been postulated that it represents a form of intraoral psoriasis.2,4 The condition is also associated with allergy, stress, diabetes mellitus, and anemia. Triggers include hot, spicy, and acidic foods and alcohol. Contrary to previous belief, geographic tongue has been found to have an inverse association with smoking.5 Although striking, the lesion rarely warrants further investigation.

REASSURANCE IS THE MAIN TREATMENT

Geographic tongue has a remitting and relapsing course with no complications or permanent sequelae.3 The differential diagnosis includes oral candidiasis, leukoplakia, vitamin deficiency glossitis, lichen planus, systemic lupus erythematosus, drug reaction, and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. The condition is differentiated from oral candidiasis by its presence in an otherwise healthy person and by the changing pattern of the lesions over time. Also, candidal pseudomembranes can be easily removed, leaving a painless red base. Evaluations to rule out anemia, nutritional deficiencies, and diabetes mellitus can be done if these conditions are suspected, as they are associated with geographic tongue.

Reassurance is the main treatment. Topical corticosteroids and local anesthetics may provide symptomatic relief in mild forms of the disease. Topical tacrolimus and systemic cyclosporine have been reported as useful in severe cases.6

- Masferrer E, Jucgla A. Images in clinical medicine. Geographic tongue. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:e44.

- Assimakopoulos D, Patrikakos G, Fotika C, Elisaf M. Benign migratory glossitis or geographic tongue: an enigmatic oral lesion. Am J Med 2002; 113:751–755.

- Scully C, Hegarty A. The oral cavity and lips. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:69–100.

- Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006; 31:192–195.

- Shulman JD, Carpenter WM. Prevalence and risk factors associated with geographic tongue among US adults. Oral Dis 2006; 12:381–386.

- Ishibashi M, Tojo G, Watanabe M, Tamabuchi T, Masu T, Aiba S. Geographic tongue treated with topical tacrolimus. J Dermatol Case Rep 2010; 4:57–59.

A previously healthy 35-year-old woman presented with reddish discoloration of her tongue for the past 7 days, accompanied by mild soreness over the area when eating spicy foods. The lesion had also changed shape repeatedly. She denied any other local or systemic symptoms.

Lingual examination showed clearly delineated areas of shiny, erythematous mucosa on the dorsal and lateral aspects of the tongue, surrounded by white borders (Figure 1). Examination of the throat and oral cavity were unremarkable. All other systemic examinations were normal. Laboratory testing showed a normal hemogram, blood glucose, and metabolic profile.

These findings were suggestive of geographic tongue, a benign, self-limiting inflammation. The patient was reassured of the benign nature of the condition and was advised to avoid spicy food until resolution of the lesion. A follow-up examination 1 month later showed complete healing of the lesion.

A COMMON, BENIGN, SELF-LIMITING MUCOSAL CONDITION

Geographic tongue—also known as benign migratory glossitis and lingual erythema migrans—is commonly seen in daily practice, with a prevalence of 2% to 3% in the general population.1 In the United States, the condition is more prevalent in whites and blacks than in Hispanics, but has no association with age or sex.

This condition is characterized by circinate, maplike areas of erythema surrounded by well-demarcated scalloped white borders, typically on the dorsum and the lateral borders of the tongue.2 The appearance, which represents loss of filiform papillae (depapillation) from the lingual mucosa, can change in size, shape, or location in a matter of minutes or hours. The name “lingual erythema migrans” reflects the changing clinical picture.3 Rarely, the labial or palatal mucosa is affected.

POSTULATED TO BE AN INTRAORAL FORM OF PSORIASIS

The precise etiology remains obscure.2 Histopathologically, geographic tongue is characterized by hyperparakeratosis and acanthosis resembling psoriasis. Hence, it has been postulated that it represents a form of intraoral psoriasis.2,4 The condition is also associated with allergy, stress, diabetes mellitus, and anemia. Triggers include hot, spicy, and acidic foods and alcohol. Contrary to previous belief, geographic tongue has been found to have an inverse association with smoking.5 Although striking, the lesion rarely warrants further investigation.

REASSURANCE IS THE MAIN TREATMENT

Geographic tongue has a remitting and relapsing course with no complications or permanent sequelae.3 The differential diagnosis includes oral candidiasis, leukoplakia, vitamin deficiency glossitis, lichen planus, systemic lupus erythematosus, drug reaction, and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. The condition is differentiated from oral candidiasis by its presence in an otherwise healthy person and by the changing pattern of the lesions over time. Also, candidal pseudomembranes can be easily removed, leaving a painless red base. Evaluations to rule out anemia, nutritional deficiencies, and diabetes mellitus can be done if these conditions are suspected, as they are associated with geographic tongue.

Reassurance is the main treatment. Topical corticosteroids and local anesthetics may provide symptomatic relief in mild forms of the disease. Topical tacrolimus and systemic cyclosporine have been reported as useful in severe cases.6

A previously healthy 35-year-old woman presented with reddish discoloration of her tongue for the past 7 days, accompanied by mild soreness over the area when eating spicy foods. The lesion had also changed shape repeatedly. She denied any other local or systemic symptoms.

Lingual examination showed clearly delineated areas of shiny, erythematous mucosa on the dorsal and lateral aspects of the tongue, surrounded by white borders (Figure 1). Examination of the throat and oral cavity were unremarkable. All other systemic examinations were normal. Laboratory testing showed a normal hemogram, blood glucose, and metabolic profile.

These findings were suggestive of geographic tongue, a benign, self-limiting inflammation. The patient was reassured of the benign nature of the condition and was advised to avoid spicy food until resolution of the lesion. A follow-up examination 1 month later showed complete healing of the lesion.

A COMMON, BENIGN, SELF-LIMITING MUCOSAL CONDITION

Geographic tongue—also known as benign migratory glossitis and lingual erythema migrans—is commonly seen in daily practice, with a prevalence of 2% to 3% in the general population.1 In the United States, the condition is more prevalent in whites and blacks than in Hispanics, but has no association with age or sex.

This condition is characterized by circinate, maplike areas of erythema surrounded by well-demarcated scalloped white borders, typically on the dorsum and the lateral borders of the tongue.2 The appearance, which represents loss of filiform papillae (depapillation) from the lingual mucosa, can change in size, shape, or location in a matter of minutes or hours. The name “lingual erythema migrans” reflects the changing clinical picture.3 Rarely, the labial or palatal mucosa is affected.

POSTULATED TO BE AN INTRAORAL FORM OF PSORIASIS

The precise etiology remains obscure.2 Histopathologically, geographic tongue is characterized by hyperparakeratosis and acanthosis resembling psoriasis. Hence, it has been postulated that it represents a form of intraoral psoriasis.2,4 The condition is also associated with allergy, stress, diabetes mellitus, and anemia. Triggers include hot, spicy, and acidic foods and alcohol. Contrary to previous belief, geographic tongue has been found to have an inverse association with smoking.5 Although striking, the lesion rarely warrants further investigation.

REASSURANCE IS THE MAIN TREATMENT

Geographic tongue has a remitting and relapsing course with no complications or permanent sequelae.3 The differential diagnosis includes oral candidiasis, leukoplakia, vitamin deficiency glossitis, lichen planus, systemic lupus erythematosus, drug reaction, and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. The condition is differentiated from oral candidiasis by its presence in an otherwise healthy person and by the changing pattern of the lesions over time. Also, candidal pseudomembranes can be easily removed, leaving a painless red base. Evaluations to rule out anemia, nutritional deficiencies, and diabetes mellitus can be done if these conditions are suspected, as they are associated with geographic tongue.

Reassurance is the main treatment. Topical corticosteroids and local anesthetics may provide symptomatic relief in mild forms of the disease. Topical tacrolimus and systemic cyclosporine have been reported as useful in severe cases.6

- Masferrer E, Jucgla A. Images in clinical medicine. Geographic tongue. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:e44.

- Assimakopoulos D, Patrikakos G, Fotika C, Elisaf M. Benign migratory glossitis or geographic tongue: an enigmatic oral lesion. Am J Med 2002; 113:751–755.

- Scully C, Hegarty A. The oral cavity and lips. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:69–100.

- Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006; 31:192–195.

- Shulman JD, Carpenter WM. Prevalence and risk factors associated with geographic tongue among US adults. Oral Dis 2006; 12:381–386.

- Ishibashi M, Tojo G, Watanabe M, Tamabuchi T, Masu T, Aiba S. Geographic tongue treated with topical tacrolimus. J Dermatol Case Rep 2010; 4:57–59.

- Masferrer E, Jucgla A. Images in clinical medicine. Geographic tongue. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:e44.

- Assimakopoulos D, Patrikakos G, Fotika C, Elisaf M. Benign migratory glossitis or geographic tongue: an enigmatic oral lesion. Am J Med 2002; 113:751–755.

- Scully C, Hegarty A. The oral cavity and lips. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:69–100.

- Zargari O. The prevalence and significance of fissured tongue and geographical tongue in psoriatic patients. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006; 31:192–195.

- Shulman JD, Carpenter WM. Prevalence and risk factors associated with geographic tongue among US adults. Oral Dis 2006; 12:381–386.

- Ishibashi M, Tojo G, Watanabe M, Tamabuchi T, Masu T, Aiba S. Geographic tongue treated with topical tacrolimus. J Dermatol Case Rep 2010; 4:57–59.

Advanced-stage calciphylaxis: Think before you punch

A 53-year-old woman presented with extensive, nonulcerated, painful plaques on both calves. She had long-standing diabetes mellitus and had recently started hemodialysis. She had no fever or trauma and did not appear to be in shock.

On physical examination, she had extensive, well-demarcated, nonulcerated, indurated dark eschar over the right calf (Figure 1). Her left calf had similar lesions that appeared as focal, discrete, nonulcerated, violaceous plaques, with associated tenderness. No significant erythema, edema, drainage, or fluctuance was noted.

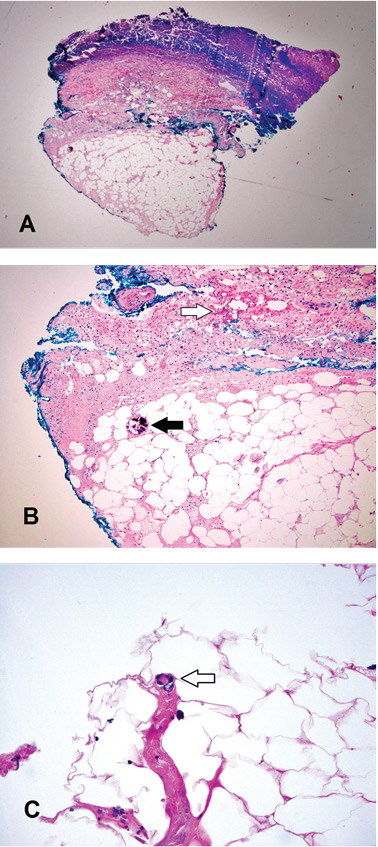

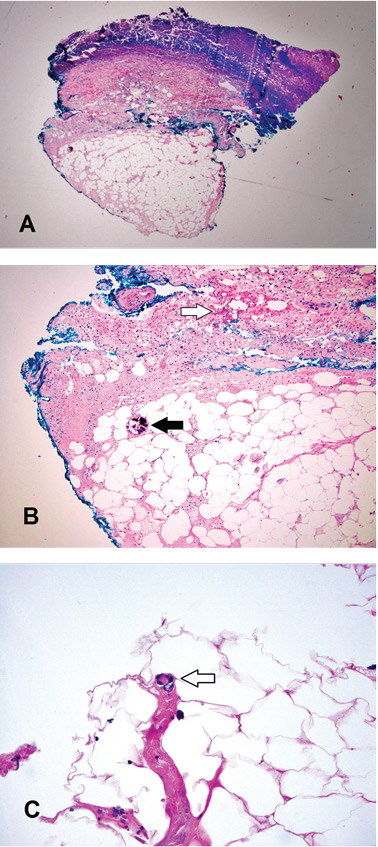

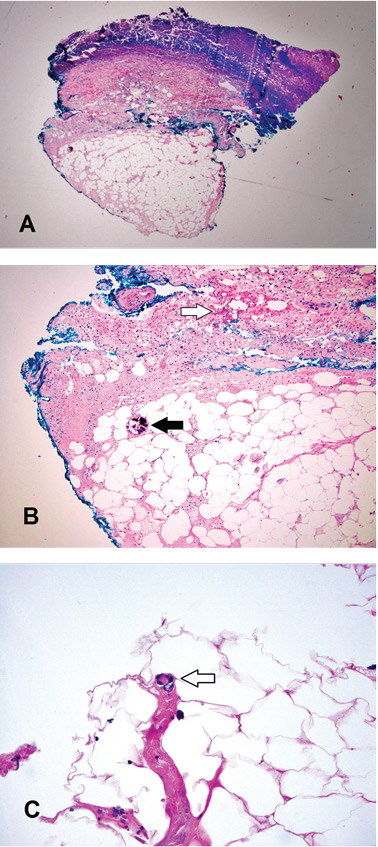

A broad-spectrum antibiotic was started empirically but was discontinued when routine blood testing and magnetic resonance imaging showed no evidence of infection. Histologic study of a full-thickness skin biopsy specimen (Figure 2) showed tissue necrosis, ulceration, and concentric calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels, many with luminal thrombi, all of which together were diagnostic for calciphylaxis.

Treatment was started with cinacalcet, low-calcium dialysis baths, phosphate binders, and sodium thiosulfate. However, within a few days of the biopsy procedure, an infection developed at the biopsy site, and the patient developed sepsis and septic shock. She received broad-spectrum antibiotics and underwent extensive debridement with wound care. After a protracted hospital course, the infection resolved.

CALCIPHYLAXIS RISK FACTORS

Calciphylaxis, also referred to as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare and often fatal condition in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis (1% to 4% of dialysis patients).1–3 It is also seen in patients who have undergone renal transplant and in patients with chronic kidney disease who have a chronic inflammatory disease or who have been exposed to corticosteroids or warfarin. However, it can also occur in patients without chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease.

The term “calcific uremic arteriolopathy” is a misnomer, as this condition can occur in patients with normal renal function (nonuremic calciphylaxis). Also, despite what the term calciphylaxis implies, there is no systemic anaphylaxis.3–5

Documented risk factors include obesity; female sex; use of warfarin, corticosteroids, or vitamin D analogues; low serum albumin; hypercoagulable states; hyperparathyroidism; alcoholic liver disease; elevated calcium-phosphorus product; inflammation; connective tissue disease; and cancer.4–6

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

There are no strict guidelines for the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, and the exact pathophysiology of calciphylaxis is not understood.1–4

Ulceration is considered the clinical hallmark, but there are increasing reports of patients presenting with nonulcerated plaques, as in our patient. The literature suggests a mortality rate of 33% at 6 months in these patients, but ulceration increases the risk of death to over 80%, and sepsis is the leading cause of death.7,8

Histologic features identified on full-thickness biopsy specimens are intravascular deposition of calcium in the media of the blood vessels, as well as fibrin thrombi formation, intimal proliferation, tissue necrosis, and resultant ischemia. However, as in our patient and as discussed below, the biopsy procedure can induce or exacerbate ulceration, increasing the risk of sepsis, and is thus controversial.7

In the early stages, lesions of calciphylaxis are focal and appear as erythema or livedo reticularis with or without subcutaneous plaques or ulcers. As the disease progresses, the ischemic changes coalesce to form denser violaceous, painful, plaquelike subcutaneous nodules with eschar. In the advanced stages, the eschar or ulceration involves an extensive area.

Diagnosis in the early stages is challenging because of the focal nature of involvement. The differential diagnosis includes potentially fatal conditions such as systemic vasculitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, gangrene from peripheral arterial disease, cholesterol embolization, warfarin-induced necrosis, purpura fulminans, and oxalate vasculopathy.7

In the advanced stages, the diagnosis of calciphylaxis is clinically more evident, and the differential diagnosis usually narrows. Well-demarcated, necrotic, indurated lesions that are bilateral in a patient with end-stage renal disease without shock makes the diagnosis very likely.

The dangers of biopsy

As seen in our patient, biopsy for histologic confirmation of calciphylaxis can increase the risk of infection and sepsis.7 Also, the efficacy and clinical utility are uncertain because the quantity or depth of tissue obtained may not be enough for diagnosis. Deep incisional cutaneous biopsy is needed rather than punch biopsy to provide ample subcutaneous tissue for histologic study.3

Further, the biopsy procedure induces ulceration in the region of the incision, increasing the risk of infection and poor healing and escalating the risk of sepsis and death.7–9 Since extensive necrosis predisposes to a negative biopsy, a high clinical suspicion should drive early treatment of calciphylaxis.10 Noninvasive imaging studies such as plain radiography and bone scintigraphy can aid the diagnosis by detecting moderate to severe soft-tissue vascular calcification in these areas.7–11

DEBRIDEMENT IS CONTROVERSIAL

Conservative measures are the mainstay of care and include dietary alterations, noncalcium and nonaluminum phosphate binders, and low-calcium bath dialysis. There is mounting evidence for the use of calcimimetics and sodium thiosulfate.7,12–14

The role of wound debridement is controversial, as concomitant poor peripheral vascular perfusion can delay wound healing and, if ulceration ensues, there is a dramatic escalation of mortality risk. The decision for wound debridement is determined case by case, based on an assessment of the comorbidities, vascular perfusion, and status of the eschar.

Extensive wound debridement should be considered immediately after biopsy or with any signs of ulceration or infection—this in addition to meticulous wound care, which will promote healing and prevent serious complications secondary to infection.15

A TEAM APPROACH IMPROVES OUTCOMES

A multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, nephrologists, dermatologists, dermatopathologists, wound or burn care team, nutrition team, pain management team, and infectious disease team is important to improve outcomes.7

Management mainly involves controlling pain; avoiding local trauma; treating and preventing infection; stopping causative agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids; intensive hemodialysis with an increase in both frequency and duration; intravenous sodium thiosulphate; non-calcium-phosphorus binders and cinacalcet in patients with elevated parathyroid hormone; and hyperbaric oxygen.12–14 There are also reports of success with oral etidronate and intravenous pamidronate.16,17

- Spanakis EK, Sellmeyer DE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis precipitated by teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] therapy in the setting of chronic warfarin and glucocorticoid treatment. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25:1411–1414.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol 2011; 24:142–148.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial 2002; 15:172–186.

- Rimtepathip P, Cohen D. A rare presentation of calciphylaxis in normal renal function. Int J Case Rep Images 2015; 6:366–369.

- Lonowski S, Martin S, Worswick S. Widespread calciphylaxis and normal renal function: no improvement with sodium thiosulfate. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21:13030/qt76845802.

- Zhou Q, Neubauer J, Kern JS, Grotz W, Walz G, Huber TB. Calciphylaxis. Lancet 2014; 383:1067.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66:133–146.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int 2002; 61:2210–2217.

- Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013; 17:498–503.

- Stavros K, Motiwala R, Zhou L, Sejdiu F, Shin S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2014; 15:108–111.

- Bonchak JG, Park KK, Vethanayagamony T, Sheikh MM, Winterfield LS. Calciphylaxis: a case series and the role of radiology in diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Ross EA. Evolution of treatment strategies for calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol 2011; 34:460–467.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:1104–1108.

- Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Specht P, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis in CKD and beyond. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:1314–1318.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage 2004; 50:64–66.

- Shiraishi N, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:151–154.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, Umegaki N, Nishimura Y, Katayama I. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57:1021–1025.

A 53-year-old woman presented with extensive, nonulcerated, painful plaques on both calves. She had long-standing diabetes mellitus and had recently started hemodialysis. She had no fever or trauma and did not appear to be in shock.

On physical examination, she had extensive, well-demarcated, nonulcerated, indurated dark eschar over the right calf (Figure 1). Her left calf had similar lesions that appeared as focal, discrete, nonulcerated, violaceous plaques, with associated tenderness. No significant erythema, edema, drainage, or fluctuance was noted.

A broad-spectrum antibiotic was started empirically but was discontinued when routine blood testing and magnetic resonance imaging showed no evidence of infection. Histologic study of a full-thickness skin biopsy specimen (Figure 2) showed tissue necrosis, ulceration, and concentric calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels, many with luminal thrombi, all of which together were diagnostic for calciphylaxis.

Treatment was started with cinacalcet, low-calcium dialysis baths, phosphate binders, and sodium thiosulfate. However, within a few days of the biopsy procedure, an infection developed at the biopsy site, and the patient developed sepsis and septic shock. She received broad-spectrum antibiotics and underwent extensive debridement with wound care. After a protracted hospital course, the infection resolved.

CALCIPHYLAXIS RISK FACTORS

Calciphylaxis, also referred to as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare and often fatal condition in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis (1% to 4% of dialysis patients).1–3 It is also seen in patients who have undergone renal transplant and in patients with chronic kidney disease who have a chronic inflammatory disease or who have been exposed to corticosteroids or warfarin. However, it can also occur in patients without chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease.

The term “calcific uremic arteriolopathy” is a misnomer, as this condition can occur in patients with normal renal function (nonuremic calciphylaxis). Also, despite what the term calciphylaxis implies, there is no systemic anaphylaxis.3–5

Documented risk factors include obesity; female sex; use of warfarin, corticosteroids, or vitamin D analogues; low serum albumin; hypercoagulable states; hyperparathyroidism; alcoholic liver disease; elevated calcium-phosphorus product; inflammation; connective tissue disease; and cancer.4–6

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

There are no strict guidelines for the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, and the exact pathophysiology of calciphylaxis is not understood.1–4

Ulceration is considered the clinical hallmark, but there are increasing reports of patients presenting with nonulcerated plaques, as in our patient. The literature suggests a mortality rate of 33% at 6 months in these patients, but ulceration increases the risk of death to over 80%, and sepsis is the leading cause of death.7,8

Histologic features identified on full-thickness biopsy specimens are intravascular deposition of calcium in the media of the blood vessels, as well as fibrin thrombi formation, intimal proliferation, tissue necrosis, and resultant ischemia. However, as in our patient and as discussed below, the biopsy procedure can induce or exacerbate ulceration, increasing the risk of sepsis, and is thus controversial.7

In the early stages, lesions of calciphylaxis are focal and appear as erythema or livedo reticularis with or without subcutaneous plaques or ulcers. As the disease progresses, the ischemic changes coalesce to form denser violaceous, painful, plaquelike subcutaneous nodules with eschar. In the advanced stages, the eschar or ulceration involves an extensive area.

Diagnosis in the early stages is challenging because of the focal nature of involvement. The differential diagnosis includes potentially fatal conditions such as systemic vasculitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, gangrene from peripheral arterial disease, cholesterol embolization, warfarin-induced necrosis, purpura fulminans, and oxalate vasculopathy.7

In the advanced stages, the diagnosis of calciphylaxis is clinically more evident, and the differential diagnosis usually narrows. Well-demarcated, necrotic, indurated lesions that are bilateral in a patient with end-stage renal disease without shock makes the diagnosis very likely.

The dangers of biopsy

As seen in our patient, biopsy for histologic confirmation of calciphylaxis can increase the risk of infection and sepsis.7 Also, the efficacy and clinical utility are uncertain because the quantity or depth of tissue obtained may not be enough for diagnosis. Deep incisional cutaneous biopsy is needed rather than punch biopsy to provide ample subcutaneous tissue for histologic study.3

Further, the biopsy procedure induces ulceration in the region of the incision, increasing the risk of infection and poor healing and escalating the risk of sepsis and death.7–9 Since extensive necrosis predisposes to a negative biopsy, a high clinical suspicion should drive early treatment of calciphylaxis.10 Noninvasive imaging studies such as plain radiography and bone scintigraphy can aid the diagnosis by detecting moderate to severe soft-tissue vascular calcification in these areas.7–11

DEBRIDEMENT IS CONTROVERSIAL

Conservative measures are the mainstay of care and include dietary alterations, noncalcium and nonaluminum phosphate binders, and low-calcium bath dialysis. There is mounting evidence for the use of calcimimetics and sodium thiosulfate.7,12–14

The role of wound debridement is controversial, as concomitant poor peripheral vascular perfusion can delay wound healing and, if ulceration ensues, there is a dramatic escalation of mortality risk. The decision for wound debridement is determined case by case, based on an assessment of the comorbidities, vascular perfusion, and status of the eschar.

Extensive wound debridement should be considered immediately after biopsy or with any signs of ulceration or infection—this in addition to meticulous wound care, which will promote healing and prevent serious complications secondary to infection.15

A TEAM APPROACH IMPROVES OUTCOMES

A multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, nephrologists, dermatologists, dermatopathologists, wound or burn care team, nutrition team, pain management team, and infectious disease team is important to improve outcomes.7

Management mainly involves controlling pain; avoiding local trauma; treating and preventing infection; stopping causative agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids; intensive hemodialysis with an increase in both frequency and duration; intravenous sodium thiosulphate; non-calcium-phosphorus binders and cinacalcet in patients with elevated parathyroid hormone; and hyperbaric oxygen.12–14 There are also reports of success with oral etidronate and intravenous pamidronate.16,17

A 53-year-old woman presented with extensive, nonulcerated, painful plaques on both calves. She had long-standing diabetes mellitus and had recently started hemodialysis. She had no fever or trauma and did not appear to be in shock.

On physical examination, she had extensive, well-demarcated, nonulcerated, indurated dark eschar over the right calf (Figure 1). Her left calf had similar lesions that appeared as focal, discrete, nonulcerated, violaceous plaques, with associated tenderness. No significant erythema, edema, drainage, or fluctuance was noted.

A broad-spectrum antibiotic was started empirically but was discontinued when routine blood testing and magnetic resonance imaging showed no evidence of infection. Histologic study of a full-thickness skin biopsy specimen (Figure 2) showed tissue necrosis, ulceration, and concentric calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels, many with luminal thrombi, all of which together were diagnostic for calciphylaxis.

Treatment was started with cinacalcet, low-calcium dialysis baths, phosphate binders, and sodium thiosulfate. However, within a few days of the biopsy procedure, an infection developed at the biopsy site, and the patient developed sepsis and septic shock. She received broad-spectrum antibiotics and underwent extensive debridement with wound care. After a protracted hospital course, the infection resolved.

CALCIPHYLAXIS RISK FACTORS

Calciphylaxis, also referred to as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare and often fatal condition in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis (1% to 4% of dialysis patients).1–3 It is also seen in patients who have undergone renal transplant and in patients with chronic kidney disease who have a chronic inflammatory disease or who have been exposed to corticosteroids or warfarin. However, it can also occur in patients without chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease.

The term “calcific uremic arteriolopathy” is a misnomer, as this condition can occur in patients with normal renal function (nonuremic calciphylaxis). Also, despite what the term calciphylaxis implies, there is no systemic anaphylaxis.3–5

Documented risk factors include obesity; female sex; use of warfarin, corticosteroids, or vitamin D analogues; low serum albumin; hypercoagulable states; hyperparathyroidism; alcoholic liver disease; elevated calcium-phosphorus product; inflammation; connective tissue disease; and cancer.4–6

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

There are no strict guidelines for the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, and the exact pathophysiology of calciphylaxis is not understood.1–4

Ulceration is considered the clinical hallmark, but there are increasing reports of patients presenting with nonulcerated plaques, as in our patient. The literature suggests a mortality rate of 33% at 6 months in these patients, but ulceration increases the risk of death to over 80%, and sepsis is the leading cause of death.7,8

Histologic features identified on full-thickness biopsy specimens are intravascular deposition of calcium in the media of the blood vessels, as well as fibrin thrombi formation, intimal proliferation, tissue necrosis, and resultant ischemia. However, as in our patient and as discussed below, the biopsy procedure can induce or exacerbate ulceration, increasing the risk of sepsis, and is thus controversial.7

In the early stages, lesions of calciphylaxis are focal and appear as erythema or livedo reticularis with or without subcutaneous plaques or ulcers. As the disease progresses, the ischemic changes coalesce to form denser violaceous, painful, plaquelike subcutaneous nodules with eschar. In the advanced stages, the eschar or ulceration involves an extensive area.

Diagnosis in the early stages is challenging because of the focal nature of involvement. The differential diagnosis includes potentially fatal conditions such as systemic vasculitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, gangrene from peripheral arterial disease, cholesterol embolization, warfarin-induced necrosis, purpura fulminans, and oxalate vasculopathy.7

In the advanced stages, the diagnosis of calciphylaxis is clinically more evident, and the differential diagnosis usually narrows. Well-demarcated, necrotic, indurated lesions that are bilateral in a patient with end-stage renal disease without shock makes the diagnosis very likely.

The dangers of biopsy

As seen in our patient, biopsy for histologic confirmation of calciphylaxis can increase the risk of infection and sepsis.7 Also, the efficacy and clinical utility are uncertain because the quantity or depth of tissue obtained may not be enough for diagnosis. Deep incisional cutaneous biopsy is needed rather than punch biopsy to provide ample subcutaneous tissue for histologic study.3

Further, the biopsy procedure induces ulceration in the region of the incision, increasing the risk of infection and poor healing and escalating the risk of sepsis and death.7–9 Since extensive necrosis predisposes to a negative biopsy, a high clinical suspicion should drive early treatment of calciphylaxis.10 Noninvasive imaging studies such as plain radiography and bone scintigraphy can aid the diagnosis by detecting moderate to severe soft-tissue vascular calcification in these areas.7–11

DEBRIDEMENT IS CONTROVERSIAL

Conservative measures are the mainstay of care and include dietary alterations, noncalcium and nonaluminum phosphate binders, and low-calcium bath dialysis. There is mounting evidence for the use of calcimimetics and sodium thiosulfate.7,12–14

The role of wound debridement is controversial, as concomitant poor peripheral vascular perfusion can delay wound healing and, if ulceration ensues, there is a dramatic escalation of mortality risk. The decision for wound debridement is determined case by case, based on an assessment of the comorbidities, vascular perfusion, and status of the eschar.

Extensive wound debridement should be considered immediately after biopsy or with any signs of ulceration or infection—this in addition to meticulous wound care, which will promote healing and prevent serious complications secondary to infection.15

A TEAM APPROACH IMPROVES OUTCOMES

A multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, nephrologists, dermatologists, dermatopathologists, wound or burn care team, nutrition team, pain management team, and infectious disease team is important to improve outcomes.7

Management mainly involves controlling pain; avoiding local trauma; treating and preventing infection; stopping causative agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids; intensive hemodialysis with an increase in both frequency and duration; intravenous sodium thiosulphate; non-calcium-phosphorus binders and cinacalcet in patients with elevated parathyroid hormone; and hyperbaric oxygen.12–14 There are also reports of success with oral etidronate and intravenous pamidronate.16,17

- Spanakis EK, Sellmeyer DE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis precipitated by teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] therapy in the setting of chronic warfarin and glucocorticoid treatment. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25:1411–1414.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol 2011; 24:142–148.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial 2002; 15:172–186.

- Rimtepathip P, Cohen D. A rare presentation of calciphylaxis in normal renal function. Int J Case Rep Images 2015; 6:366–369.

- Lonowski S, Martin S, Worswick S. Widespread calciphylaxis and normal renal function: no improvement with sodium thiosulfate. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21:13030/qt76845802.

- Zhou Q, Neubauer J, Kern JS, Grotz W, Walz G, Huber TB. Calciphylaxis. Lancet 2014; 383:1067.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66:133–146.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int 2002; 61:2210–2217.

- Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013; 17:498–503.

- Stavros K, Motiwala R, Zhou L, Sejdiu F, Shin S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2014; 15:108–111.

- Bonchak JG, Park KK, Vethanayagamony T, Sheikh MM, Winterfield LS. Calciphylaxis: a case series and the role of radiology in diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Ross EA. Evolution of treatment strategies for calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol 2011; 34:460–467.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:1104–1108.

- Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Specht P, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis in CKD and beyond. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:1314–1318.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage 2004; 50:64–66.

- Shiraishi N, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:151–154.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, Umegaki N, Nishimura Y, Katayama I. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57:1021–1025.

- Spanakis EK, Sellmeyer DE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis precipitated by teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] therapy in the setting of chronic warfarin and glucocorticoid treatment. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25:1411–1414.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol 2011; 24:142–148.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial 2002; 15:172–186.

- Rimtepathip P, Cohen D. A rare presentation of calciphylaxis in normal renal function. Int J Case Rep Images 2015; 6:366–369.

- Lonowski S, Martin S, Worswick S. Widespread calciphylaxis and normal renal function: no improvement with sodium thiosulfate. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21:13030/qt76845802.

- Zhou Q, Neubauer J, Kern JS, Grotz W, Walz G, Huber TB. Calciphylaxis. Lancet 2014; 383:1067.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66:133–146.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int 2002; 61:2210–2217.

- Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013; 17:498–503.

- Stavros K, Motiwala R, Zhou L, Sejdiu F, Shin S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2014; 15:108–111.

- Bonchak JG, Park KK, Vethanayagamony T, Sheikh MM, Winterfield LS. Calciphylaxis: a case series and the role of radiology in diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Ross EA. Evolution of treatment strategies for calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol 2011; 34:460–467.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:1104–1108.

- Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Specht P, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis in CKD and beyond. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:1314–1318.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage 2004; 50:64–66.

- Shiraishi N, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:151–154.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, Umegaki N, Nishimura Y, Katayama I. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57:1021–1025.