User login

Are sweeping efforts to reduce primary CD rates associated with an increase in maternal or neonatal AEs?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Main EK, Chang SC, Cape V, et al. Safety assessment of a large-scale improvement collaborative to reduce nulliparous cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:613-623.

Cesarean delivery can be lifesaving for both mother and infant. When compared with successful vaginal delivery, however, CD is associated with higher maternal complication rates (including excessive blood loss requiring blood product transfusion, infectious morbidity, and venous thromboembolic events), longer hospital length of stay, and higher cost. While the optimal CD rate is not well defined, it is generally accepted that the CD rate in the United States is excessively high. As such, efforts to reduce the CD rate should be encouraged, but not at the expense of patient safety.

Details about the study

In keeping with the dictum that the most important CD to prevent is the first one, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) in 2016 introduced a large-scale quality improvement project designed to reduce nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex (NTSV) CDs across the state. This bundle included education around joint guidelines issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine on reducing primary CDs,1 introduction of a CMQCC toolkit, increased nursing labor support, and monthly meetings to share best practices across all collaborating sites. The NTSV CD rate in these hospitals did decrease from 29.3% in 2015 to 25.0% in 2017 (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.73–0.78).

Whether or not implementation of the bundle resulted in an inappropriate delay in indicated CDs and, as such, in an increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity is not known. To address this issue, Main and colleagues collected cross-sectional data from more than 50 hospitals with more than 119,000 deliveries throughout California and measured rates of chorioamnionitis, blood transfusions, third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations, operative vaginal delivery, severe unexpected newborn complications, and 5-minute Apgar scores of less than 5. None of the 6 safety measures showed any difference when comparing 2017 (after implementation of the CMQCC bundle) to 2015 (before implementation), suggesting that patient safety was not compromised significantly.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Strengths of this study include its large sample size and multicenter design with inclusion of a variety of collaborating hospitals. Earlier studies examining the effect of standardized protocols to reduce CD rates have been largely underpowered and conducted at single institutions.2-6 Moreover, results have been mixed, with some studies reporting an increase in maternal/neonatal adverse events,2-4 while others suggesting an improvement in select newborn quality outcome metrics.5 The current study provides reassurance to providers and institutions employing strategies to reduce NTSV CD rates that such efforts are safe.

Continue to: This study has several limitations...

This study has several limitations. Data collection relied on birth certificate and discharge diagnoses without a robust quality audit. As such, ascertainment bias, random error, and undercounting cannot be excluded. Although the population was heterogeneous, most women had more than a high school education and private insurance, and only 1 in 5 were obese. Whether these findings are generalizable to other areas within the United States is not known.

All reasonable efforts to decrease the CD rate in the United States should be encouraged, with particular attention paid to avoiding the first CD. However, this should not be done at the expense of patient safety. Large-scale quality improvement initiatives, similar to CMQCC efforts in California in 2016, appear to be one such strategy. Other successful strategies may include, for example, routine induction of labor for all low-risk nulliparous women at 39 weeks' gestation.7 The current report suggests that implementing a large-scale quality improvement initiative to reduce the primary CD rate can likely be done safely, without a significant increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. ACOG Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:693-711.

- Rosenbloom JI, Stout MJ, Tuuli MG, et al. New labor management guidelines and changes in cesarean delivery patterns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:689.e1-689.e8.

- Vadnais MA, Hacker MR, Shah NT, et al. Quality improvement initiatives lead to reduction in nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean delivery rate. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43:53-61.

- Zipori Y, Grunwald O, Ginsberg Y, et al. The impact of extending the second stage of labor to prevent primary cesarean delivery on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 220:191.e1-191.e7.

- Thuillier C, Roy S, Peyronnet V, et al. Impact of recommended changes in labor management for prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:341.e1-341.e9.

- Gimovsky AC, Berghella V. Randomized controlled trial of prolonged second stage: extending the time limit vs usual guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:361.e1-361.e6.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Main EK, Chang SC, Cape V, et al. Safety assessment of a large-scale improvement collaborative to reduce nulliparous cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:613-623.

Cesarean delivery can be lifesaving for both mother and infant. When compared with successful vaginal delivery, however, CD is associated with higher maternal complication rates (including excessive blood loss requiring blood product transfusion, infectious morbidity, and venous thromboembolic events), longer hospital length of stay, and higher cost. While the optimal CD rate is not well defined, it is generally accepted that the CD rate in the United States is excessively high. As such, efforts to reduce the CD rate should be encouraged, but not at the expense of patient safety.

Details about the study

In keeping with the dictum that the most important CD to prevent is the first one, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) in 2016 introduced a large-scale quality improvement project designed to reduce nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex (NTSV) CDs across the state. This bundle included education around joint guidelines issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine on reducing primary CDs,1 introduction of a CMQCC toolkit, increased nursing labor support, and monthly meetings to share best practices across all collaborating sites. The NTSV CD rate in these hospitals did decrease from 29.3% in 2015 to 25.0% in 2017 (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.73–0.78).

Whether or not implementation of the bundle resulted in an inappropriate delay in indicated CDs and, as such, in an increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity is not known. To address this issue, Main and colleagues collected cross-sectional data from more than 50 hospitals with more than 119,000 deliveries throughout California and measured rates of chorioamnionitis, blood transfusions, third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations, operative vaginal delivery, severe unexpected newborn complications, and 5-minute Apgar scores of less than 5. None of the 6 safety measures showed any difference when comparing 2017 (after implementation of the CMQCC bundle) to 2015 (before implementation), suggesting that patient safety was not compromised significantly.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Strengths of this study include its large sample size and multicenter design with inclusion of a variety of collaborating hospitals. Earlier studies examining the effect of standardized protocols to reduce CD rates have been largely underpowered and conducted at single institutions.2-6 Moreover, results have been mixed, with some studies reporting an increase in maternal/neonatal adverse events,2-4 while others suggesting an improvement in select newborn quality outcome metrics.5 The current study provides reassurance to providers and institutions employing strategies to reduce NTSV CD rates that such efforts are safe.

Continue to: This study has several limitations...

This study has several limitations. Data collection relied on birth certificate and discharge diagnoses without a robust quality audit. As such, ascertainment bias, random error, and undercounting cannot be excluded. Although the population was heterogeneous, most women had more than a high school education and private insurance, and only 1 in 5 were obese. Whether these findings are generalizable to other areas within the United States is not known.

All reasonable efforts to decrease the CD rate in the United States should be encouraged, with particular attention paid to avoiding the first CD. However, this should not be done at the expense of patient safety. Large-scale quality improvement initiatives, similar to CMQCC efforts in California in 2016, appear to be one such strategy. Other successful strategies may include, for example, routine induction of labor for all low-risk nulliparous women at 39 weeks' gestation.7 The current report suggests that implementing a large-scale quality improvement initiative to reduce the primary CD rate can likely be done safely, without a significant increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Main EK, Chang SC, Cape V, et al. Safety assessment of a large-scale improvement collaborative to reduce nulliparous cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:613-623.

Cesarean delivery can be lifesaving for both mother and infant. When compared with successful vaginal delivery, however, CD is associated with higher maternal complication rates (including excessive blood loss requiring blood product transfusion, infectious morbidity, and venous thromboembolic events), longer hospital length of stay, and higher cost. While the optimal CD rate is not well defined, it is generally accepted that the CD rate in the United States is excessively high. As such, efforts to reduce the CD rate should be encouraged, but not at the expense of patient safety.

Details about the study

In keeping with the dictum that the most important CD to prevent is the first one, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) in 2016 introduced a large-scale quality improvement project designed to reduce nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex (NTSV) CDs across the state. This bundle included education around joint guidelines issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine on reducing primary CDs,1 introduction of a CMQCC toolkit, increased nursing labor support, and monthly meetings to share best practices across all collaborating sites. The NTSV CD rate in these hospitals did decrease from 29.3% in 2015 to 25.0% in 2017 (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.73–0.78).

Whether or not implementation of the bundle resulted in an inappropriate delay in indicated CDs and, as such, in an increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity is not known. To address this issue, Main and colleagues collected cross-sectional data from more than 50 hospitals with more than 119,000 deliveries throughout California and measured rates of chorioamnionitis, blood transfusions, third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations, operative vaginal delivery, severe unexpected newborn complications, and 5-minute Apgar scores of less than 5. None of the 6 safety measures showed any difference when comparing 2017 (after implementation of the CMQCC bundle) to 2015 (before implementation), suggesting that patient safety was not compromised significantly.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Strengths of this study include its large sample size and multicenter design with inclusion of a variety of collaborating hospitals. Earlier studies examining the effect of standardized protocols to reduce CD rates have been largely underpowered and conducted at single institutions.2-6 Moreover, results have been mixed, with some studies reporting an increase in maternal/neonatal adverse events,2-4 while others suggesting an improvement in select newborn quality outcome metrics.5 The current study provides reassurance to providers and institutions employing strategies to reduce NTSV CD rates that such efforts are safe.

Continue to: This study has several limitations...

This study has several limitations. Data collection relied on birth certificate and discharge diagnoses without a robust quality audit. As such, ascertainment bias, random error, and undercounting cannot be excluded. Although the population was heterogeneous, most women had more than a high school education and private insurance, and only 1 in 5 were obese. Whether these findings are generalizable to other areas within the United States is not known.

All reasonable efforts to decrease the CD rate in the United States should be encouraged, with particular attention paid to avoiding the first CD. However, this should not be done at the expense of patient safety. Large-scale quality improvement initiatives, similar to CMQCC efforts in California in 2016, appear to be one such strategy. Other successful strategies may include, for example, routine induction of labor for all low-risk nulliparous women at 39 weeks' gestation.7 The current report suggests that implementing a large-scale quality improvement initiative to reduce the primary CD rate can likely be done safely, without a significant increase in maternal or neonatal morbidity.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. ACOG Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:693-711.

- Rosenbloom JI, Stout MJ, Tuuli MG, et al. New labor management guidelines and changes in cesarean delivery patterns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:689.e1-689.e8.

- Vadnais MA, Hacker MR, Shah NT, et al. Quality improvement initiatives lead to reduction in nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean delivery rate. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43:53-61.

- Zipori Y, Grunwald O, Ginsberg Y, et al. The impact of extending the second stage of labor to prevent primary cesarean delivery on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 220:191.e1-191.e7.

- Thuillier C, Roy S, Peyronnet V, et al. Impact of recommended changes in labor management for prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:341.e1-341.e9.

- Gimovsky AC, Berghella V. Randomized controlled trial of prolonged second stage: extending the time limit vs usual guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:361.e1-361.e6.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. ACOG Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:693-711.

- Rosenbloom JI, Stout MJ, Tuuli MG, et al. New labor management guidelines and changes in cesarean delivery patterns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:689.e1-689.e8.

- Vadnais MA, Hacker MR, Shah NT, et al. Quality improvement initiatives lead to reduction in nulliparous term singleton vertex cesarean delivery rate. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43:53-61.

- Zipori Y, Grunwald O, Ginsberg Y, et al. The impact of extending the second stage of labor to prevent primary cesarean delivery on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 220:191.e1-191.e7.

- Thuillier C, Roy S, Peyronnet V, et al. Impact of recommended changes in labor management for prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:341.e1-341.e9.

- Gimovsky AC, Berghella V. Randomized controlled trial of prolonged second stage: extending the time limit vs usual guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:361.e1-361.e6.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

The ARRIVE trial: Women’s desideratum versus logistical concerns

Of the 1.5 million nulliparous women who deliver annually in the United States, more than 50% are low-risk pregnancies. Among clinicians, there is a hesitancy to offer elective induction of labor to low-risk nulliparous women, mainly due to early observational studies that noted an association between elective induction of labor and higher rates of cesarean delivery (CD) and other adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. 1-3 This reluctance over time has permeated throughout the ObGyn specialty and is culturally embedded in contemporary practice. The early observational studies lacked proper comparison groups because outcomes of women undergoing induction (elective and medically indicated) were compared to those in spontaneous labor. Since women who are being induced do not have the option to be in spontaneous labor, the appropriate comparator group for women undergoing elective induction is women who are being managed expectantly.

ARRIVE addresses appropriate comparator groups

Challenging this pervaded practice, in August 2018, Grobman and colleagues published the findings of the ARRIVE trial (A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management).4 This trial, conducted by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network, recruited participants from 41 geographically dispersed centers in the United States. Nulliparous women with low-risk pregnancies between 34 0/7 and 38 6/7 weeks were randomly assigned to either induction of labor at 39 0/7 to 39 4/7 weeks or to expectant management, which was defined as delaying induction until 40 5/7 to 42 2/7 weeks. The objective of the ARRIVE trial was to determine if, among low-risk nulliparous women, elective induction of labor at 39 weeks, compared with expectant management, would reduce the rate of adverse outcomes.

The primary outcome was a composite: perinatal death or severe neonatal complications (need for respiratory support within 72 hours of birth, Apgar score of ≤ 3 at 5 minutes, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, seizures, infection [confirmed sepsis or pneumonia], meconium aspiration syndrome, birth trauma [bone fracture, neurologic injury, or retinal damage], intracranial or subgaleal hemorrhage, or hypotension requiring vasopressor support). The secondary outcomes included CD, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, number of hours in the labor and delivery (L&D) unit, length of postpartum hospital stay, and assessment of satisfaction with labor process.

Mothers induced at 39 weeks fared better, while neonatal outcomes were similar. Of 22,533 eligible women, 6,106 (27%) were randomized: 3,062 were assigned to the induction group, and, 3,044 to the expectant management group. The primary composite outcome—perinatal death or severe neonatal complications—was similar in both groups (4.3% in the induction group vs 5.4% in the expectant management group).

However, women who were induced had significantly lower rates of:

- CD (18.6% with induction vs 22.2% for expectant management; relative risk [RR], 0.84; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76–0.93)

- hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (9.1% vs 14.1%; RR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.56–0.74)

- neonatal respiratory support (3.0% vs. 4.2%; RR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55–0.93).

In addition, although women in the induction group had a longer stay in the L&D unit (an expected outcome), the overall postpartum length of stay was shorter. Finally, women in the induction group had higher patient satisfaction scores, with less pain and more control reported during labor.

Continue to: What about uncommon adverse outcomes compared at 39 vs 41 weeks?

What about uncommon adverse outcomes compared at 39 vs 41 weeks?

Due to the study’s sample size, ARRIVE investigators could not ascertain if uncommon adverse outcomes (maternal admission to intensive care unit or neonatal seizure) are significantly more common at 40 and 41 weeks, than at 39 weeks.

To address the issue of uncommon adverse outcomes, Chen and colleagues analyzed the US Vital Statistics datasets to compare composite maternal and neonatal morbidity among low-risk nulliparous women with nonanomalous singleton gestations who labored at 39 to 41 weeks.5 The primary outcome was composite neonatal morbidity that included Apgar score < 5 at 5 minutes, assisted ventilation longer than 6 hours, seizure, or neonatal mortality. The secondary outcome was composite maternal morbidity that included intensive care unit admission, blood transfusion, uterine rupture, or unplanned hysterectomy.

The investigators found that from 2011–2015, among 19.8 million live births in the United States, there were 3.3 million live births among low-risk nulliparous women. Among these women, 43% delivered at 39 weeks’ gestation, 41% at 40 weeks, and 15% at 41 weeks. The overall rate of composite neonatal morbidity was 8.8 per 1,000 live births; compared with those who delivered at 39 weeks, composite neonatal morbidity was significantly higher for those delivered at 40 (adjusted RR [aRR], 1.22; 95% CI, 1.19–1.25) and 41 weeks (aRR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.49–1.58).

The secondary outcome, the overall rate of composite maternal morbidity, was 2.8 per 1,000 live births. As with composite neonatal morbidity, the risk of composite maternal morbidity was also significantly higher for those delivered at 40 (aRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.14–1.25) and 41 weeks’ gestation (aRR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.47–1.65) than at 39 weeks.

Thus, among low-risk nulliparous pregnancies, there is an incremental increase in the rates of composite neonatal and maternal morbidity from 39 to 41 weeks.

Is induction of labor at 39 weeks feasible?

As the evidence demonstrating multiple benefits of 39-week inductions increases, concerns regarding the feasibility and cost of implementation in the current US health care system mount. A planned secondary analysis of the ARRIVE trial evaluated medical resource utilization among low-risk nulliparous women randomly assigned to elective induction at 39 weeks or expectant management.6 Resource utilization was compared between the 2 groups during the antepartum period, delivery admission, and from discharge to 8 weeks postpartum.

For the antepartum period, women in the induction group were significantly less likely than women undergoing expectant management to have at least 1: office visit for routine prenatal care (32.4% vs 68.4%), unanticipated office visit (0.5% vs 2.6%), urgent care/emergency department/triage visit (16.2% vs 44.3%), or hospital admission (0.8% vs 2.2%). When admitted for delivery, as expected, women in the induction group spent significantly more time on the L&D unit (14 hours vs 20 hours) and were more likely to receive interventions for induction (cervical ripening, oxytocin, intrauterine pressure catheter placement). However, they required magnesium sulfate and antibiotics significantly less frequently. For the postpartum group comparison, women in the induction group and their neonates had a significantly shorter duration of hospital stay.

In summary, the investigators found that, compared to women undergoing expectant management, women undergoing elective induction spent longer duration in L&D units and utilized more resources, but they required significantly fewer antepartum clinic and hospital visits, treatments for hypertensive disorders or chorioamnionitis, and had shorter duration of postpartum length of stay.

Continue to: Is induction of labor at 39 weeks cost-effective?

Is induction of labor at 39 weeks cost-effective?

Hersh and colleagues performed a cost-effectiveness analysis for induction of labor at 39 weeks versus expectant management for low-risk nulliparous women.7 Based on 2016 National Vital Statistics Data, there were 3.5 million term births in the United States. Following the exclusion of high-risk pregnancies and term parous low-risk pregnancies, a theoretical cohort of 1.6 million low-risk nulliparous women was included in the analysis. A decision-tree analytic model was created, in which the initial node stratified low-risk nulliparous women into 2 categories: elective induction at 39 weeks and expectant management. Probabilities of maternal and neonatal outcomes were derived from the literature.

Maternal outcomes included hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and delivery mode. Neonatal outcomes included macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, stillbirth, and neonatal death. Costs of clinic and triage visits, induction of labor, modes of delivery, and maternal and neonatal outcomes were derived from previous studies and adjusted for inflation to 2018 dollars. Finally, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were calculated for mothers and neonates and were then used to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of elective induction of labor at 39 weeks. Following accepted standards, the threshold for cost-effectiveness was set at $100,000/QALYs or less.

Induction at 39 weeks comes in lower cost-wise than the standard threshold for QALY. In their analysis, the investigators found that if all 1.6 million women in their theoretical cohort underwent an elective induction of labor at 39 weeks (rather than expectant management), there would be 54,498 fewer CDs, 79,152 fewer cases of hypertensive disorders, 795 fewer cases of stillbirth, and 11 fewer neonatal deaths. Due to the decreased CD rates, the investigators did project an estimated 86 additional cases of neonatal brachial plexus injury. Using these estimates, costs, and utilities, the authors demonstrated that, compared with expectant management, elective induction of labor at 39 weeks was marginally cost-effective with an ICER of $87,692 per QALY, which was lower than the cost-effectiveness threshold of $100,000 per QALY.

Based on additional sensitivity analyses, the authors concluded that cost-effectiveness of elective induction of labor varied based on variations in model inputs. Specifically, the authors demonstrated that cost-effectiveness of induction of labor varied based on labor induction techniques, modes of delivery, and fluctuations in the rates of CD in induction versus expectant management groups.

Despite these theoretically imputed findings, the authors acknowledged the limitations of their study. Their cost-effectiveness model did not account for costs associated with long-term health impact of CD and hypertensive disease of pregnancy. Additionally, their model did not account for an increase in cost and resource utilization associated with increased time on L&D units to accommodate women undergoing induction. Furthermore, the analysis did not take into account the bundled payments for vaginal versus CDs, which are increasing in prevalence. Lastly, the analysis did not consider the incremental increase in severe neonatal and maternal morbidity from 39 to 41 weeks that Chen et al found in their study.5

Will ARRIVE finally arrive?

Cognizant of the medical and economic benefits of 39-week inductions, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology published a joint practice advisory recommending “shared decision-making” when counseling low-risk women about induction.8 While more research is needed to validate the aforementioned findings, particularly in regard to resource utilization, the ARRIVE trial and its associated analyses suggest that a reconsideration to deliver term low-risk nulliparous women at 39 weeks is warranted.

In summary, the overwhelming evidence suggests that, among low-risk nulliparous women there are maternal and neonatal benefits with delivery at 39 weeks, as compared with expectant management. Logistical concerns should not interfere with women’s desideratum for optimal outcomes.

- Vardo JH, Thornburg LL, Glantz JC. Maternal and neonatal morbidity among nulliparous women undergoing elective induction of labor. J Reprod Med. 2011;56:25-30.

- Dunne C, Da Silva O, Schmidt G, Natale R. Outcomes of elective labour induction and elective caesarean section in low-risk pregnancies between 37 and 41 weeks’ gestation. J Obstet Gynaecol Can . 2009;31:1124-1130.

- Guerra GV, Cecatti JG, Souza JP, et al; WHO Global Survey on Maternal Perinatal Health in Latin America Study Group. Elective induction versus spontaneous labour in Latin America. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:657-665.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

- Chen HY, Grobman WA, Blackwell SC, et al. Women at 39-41 weeks of gestation among low-risk nulliparous women, several adverse outcomes—including neonatal mortality—are significantly more frequent with delivery at 40 or 41 weeks of gestation than at 39 weeks. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:729-737.

- Grobman WA, et al. Resource utilization among low-risk nulliparas randomized to elective induction at 39 weeks or expectant management. Oral presentation at: Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine 39th Annual Pregnancy Meeting; February 11-16, 2019; Las Vegas, NV.

- Hersh AR, Skeith AE, Sargent JA, et al. Induction of labor at 39 weeks of gestation vs. expectant management for low-risk nulliparous women: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol . February 12, 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.ajog.2019.02.017.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Publications Committee. SMFM statement on elective induction of labor in low-risk nulliparous women at term: the ARRIVE trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. August 9, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.08.009.

Of the 1.5 million nulliparous women who deliver annually in the United States, more than 50% are low-risk pregnancies. Among clinicians, there is a hesitancy to offer elective induction of labor to low-risk nulliparous women, mainly due to early observational studies that noted an association between elective induction of labor and higher rates of cesarean delivery (CD) and other adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. 1-3 This reluctance over time has permeated throughout the ObGyn specialty and is culturally embedded in contemporary practice. The early observational studies lacked proper comparison groups because outcomes of women undergoing induction (elective and medically indicated) were compared to those in spontaneous labor. Since women who are being induced do not have the option to be in spontaneous labor, the appropriate comparator group for women undergoing elective induction is women who are being managed expectantly.

ARRIVE addresses appropriate comparator groups

Challenging this pervaded practice, in August 2018, Grobman and colleagues published the findings of the ARRIVE trial (A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management).4 This trial, conducted by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network, recruited participants from 41 geographically dispersed centers in the United States. Nulliparous women with low-risk pregnancies between 34 0/7 and 38 6/7 weeks were randomly assigned to either induction of labor at 39 0/7 to 39 4/7 weeks or to expectant management, which was defined as delaying induction until 40 5/7 to 42 2/7 weeks. The objective of the ARRIVE trial was to determine if, among low-risk nulliparous women, elective induction of labor at 39 weeks, compared with expectant management, would reduce the rate of adverse outcomes.

The primary outcome was a composite: perinatal death or severe neonatal complications (need for respiratory support within 72 hours of birth, Apgar score of ≤ 3 at 5 minutes, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, seizures, infection [confirmed sepsis or pneumonia], meconium aspiration syndrome, birth trauma [bone fracture, neurologic injury, or retinal damage], intracranial or subgaleal hemorrhage, or hypotension requiring vasopressor support). The secondary outcomes included CD, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, number of hours in the labor and delivery (L&D) unit, length of postpartum hospital stay, and assessment of satisfaction with labor process.

Mothers induced at 39 weeks fared better, while neonatal outcomes were similar. Of 22,533 eligible women, 6,106 (27%) were randomized: 3,062 were assigned to the induction group, and, 3,044 to the expectant management group. The primary composite outcome—perinatal death or severe neonatal complications—was similar in both groups (4.3% in the induction group vs 5.4% in the expectant management group).

However, women who were induced had significantly lower rates of:

- CD (18.6% with induction vs 22.2% for expectant management; relative risk [RR], 0.84; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76–0.93)

- hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (9.1% vs 14.1%; RR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.56–0.74)

- neonatal respiratory support (3.0% vs. 4.2%; RR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55–0.93).

In addition, although women in the induction group had a longer stay in the L&D unit (an expected outcome), the overall postpartum length of stay was shorter. Finally, women in the induction group had higher patient satisfaction scores, with less pain and more control reported during labor.

Continue to: What about uncommon adverse outcomes compared at 39 vs 41 weeks?

What about uncommon adverse outcomes compared at 39 vs 41 weeks?

Due to the study’s sample size, ARRIVE investigators could not ascertain if uncommon adverse outcomes (maternal admission to intensive care unit or neonatal seizure) are significantly more common at 40 and 41 weeks, than at 39 weeks.

To address the issue of uncommon adverse outcomes, Chen and colleagues analyzed the US Vital Statistics datasets to compare composite maternal and neonatal morbidity among low-risk nulliparous women with nonanomalous singleton gestations who labored at 39 to 41 weeks.5 The primary outcome was composite neonatal morbidity that included Apgar score < 5 at 5 minutes, assisted ventilation longer than 6 hours, seizure, or neonatal mortality. The secondary outcome was composite maternal morbidity that included intensive care unit admission, blood transfusion, uterine rupture, or unplanned hysterectomy.

The investigators found that from 2011–2015, among 19.8 million live births in the United States, there were 3.3 million live births among low-risk nulliparous women. Among these women, 43% delivered at 39 weeks’ gestation, 41% at 40 weeks, and 15% at 41 weeks. The overall rate of composite neonatal morbidity was 8.8 per 1,000 live births; compared with those who delivered at 39 weeks, composite neonatal morbidity was significantly higher for those delivered at 40 (adjusted RR [aRR], 1.22; 95% CI, 1.19–1.25) and 41 weeks (aRR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.49–1.58).

The secondary outcome, the overall rate of composite maternal morbidity, was 2.8 per 1,000 live births. As with composite neonatal morbidity, the risk of composite maternal morbidity was also significantly higher for those delivered at 40 (aRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.14–1.25) and 41 weeks’ gestation (aRR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.47–1.65) than at 39 weeks.

Thus, among low-risk nulliparous pregnancies, there is an incremental increase in the rates of composite neonatal and maternal morbidity from 39 to 41 weeks.

Is induction of labor at 39 weeks feasible?

As the evidence demonstrating multiple benefits of 39-week inductions increases, concerns regarding the feasibility and cost of implementation in the current US health care system mount. A planned secondary analysis of the ARRIVE trial evaluated medical resource utilization among low-risk nulliparous women randomly assigned to elective induction at 39 weeks or expectant management.6 Resource utilization was compared between the 2 groups during the antepartum period, delivery admission, and from discharge to 8 weeks postpartum.

For the antepartum period, women in the induction group were significantly less likely than women undergoing expectant management to have at least 1: office visit for routine prenatal care (32.4% vs 68.4%), unanticipated office visit (0.5% vs 2.6%), urgent care/emergency department/triage visit (16.2% vs 44.3%), or hospital admission (0.8% vs 2.2%). When admitted for delivery, as expected, women in the induction group spent significantly more time on the L&D unit (14 hours vs 20 hours) and were more likely to receive interventions for induction (cervical ripening, oxytocin, intrauterine pressure catheter placement). However, they required magnesium sulfate and antibiotics significantly less frequently. For the postpartum group comparison, women in the induction group and their neonates had a significantly shorter duration of hospital stay.

In summary, the investigators found that, compared to women undergoing expectant management, women undergoing elective induction spent longer duration in L&D units and utilized more resources, but they required significantly fewer antepartum clinic and hospital visits, treatments for hypertensive disorders or chorioamnionitis, and had shorter duration of postpartum length of stay.

Continue to: Is induction of labor at 39 weeks cost-effective?

Is induction of labor at 39 weeks cost-effective?

Hersh and colleagues performed a cost-effectiveness analysis for induction of labor at 39 weeks versus expectant management for low-risk nulliparous women.7 Based on 2016 National Vital Statistics Data, there were 3.5 million term births in the United States. Following the exclusion of high-risk pregnancies and term parous low-risk pregnancies, a theoretical cohort of 1.6 million low-risk nulliparous women was included in the analysis. A decision-tree analytic model was created, in which the initial node stratified low-risk nulliparous women into 2 categories: elective induction at 39 weeks and expectant management. Probabilities of maternal and neonatal outcomes were derived from the literature.

Maternal outcomes included hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and delivery mode. Neonatal outcomes included macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, stillbirth, and neonatal death. Costs of clinic and triage visits, induction of labor, modes of delivery, and maternal and neonatal outcomes were derived from previous studies and adjusted for inflation to 2018 dollars. Finally, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were calculated for mothers and neonates and were then used to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of elective induction of labor at 39 weeks. Following accepted standards, the threshold for cost-effectiveness was set at $100,000/QALYs or less.

Induction at 39 weeks comes in lower cost-wise than the standard threshold for QALY. In their analysis, the investigators found that if all 1.6 million women in their theoretical cohort underwent an elective induction of labor at 39 weeks (rather than expectant management), there would be 54,498 fewer CDs, 79,152 fewer cases of hypertensive disorders, 795 fewer cases of stillbirth, and 11 fewer neonatal deaths. Due to the decreased CD rates, the investigators did project an estimated 86 additional cases of neonatal brachial plexus injury. Using these estimates, costs, and utilities, the authors demonstrated that, compared with expectant management, elective induction of labor at 39 weeks was marginally cost-effective with an ICER of $87,692 per QALY, which was lower than the cost-effectiveness threshold of $100,000 per QALY.

Based on additional sensitivity analyses, the authors concluded that cost-effectiveness of elective induction of labor varied based on variations in model inputs. Specifically, the authors demonstrated that cost-effectiveness of induction of labor varied based on labor induction techniques, modes of delivery, and fluctuations in the rates of CD in induction versus expectant management groups.

Despite these theoretically imputed findings, the authors acknowledged the limitations of their study. Their cost-effectiveness model did not account for costs associated with long-term health impact of CD and hypertensive disease of pregnancy. Additionally, their model did not account for an increase in cost and resource utilization associated with increased time on L&D units to accommodate women undergoing induction. Furthermore, the analysis did not take into account the bundled payments for vaginal versus CDs, which are increasing in prevalence. Lastly, the analysis did not consider the incremental increase in severe neonatal and maternal morbidity from 39 to 41 weeks that Chen et al found in their study.5

Will ARRIVE finally arrive?

Cognizant of the medical and economic benefits of 39-week inductions, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology published a joint practice advisory recommending “shared decision-making” when counseling low-risk women about induction.8 While more research is needed to validate the aforementioned findings, particularly in regard to resource utilization, the ARRIVE trial and its associated analyses suggest that a reconsideration to deliver term low-risk nulliparous women at 39 weeks is warranted.

In summary, the overwhelming evidence suggests that, among low-risk nulliparous women there are maternal and neonatal benefits with delivery at 39 weeks, as compared with expectant management. Logistical concerns should not interfere with women’s desideratum for optimal outcomes.

Of the 1.5 million nulliparous women who deliver annually in the United States, more than 50% are low-risk pregnancies. Among clinicians, there is a hesitancy to offer elective induction of labor to low-risk nulliparous women, mainly due to early observational studies that noted an association between elective induction of labor and higher rates of cesarean delivery (CD) and other adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. 1-3 This reluctance over time has permeated throughout the ObGyn specialty and is culturally embedded in contemporary practice. The early observational studies lacked proper comparison groups because outcomes of women undergoing induction (elective and medically indicated) were compared to those in spontaneous labor. Since women who are being induced do not have the option to be in spontaneous labor, the appropriate comparator group for women undergoing elective induction is women who are being managed expectantly.

ARRIVE addresses appropriate comparator groups

Challenging this pervaded practice, in August 2018, Grobman and colleagues published the findings of the ARRIVE trial (A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management).4 This trial, conducted by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network, recruited participants from 41 geographically dispersed centers in the United States. Nulliparous women with low-risk pregnancies between 34 0/7 and 38 6/7 weeks were randomly assigned to either induction of labor at 39 0/7 to 39 4/7 weeks or to expectant management, which was defined as delaying induction until 40 5/7 to 42 2/7 weeks. The objective of the ARRIVE trial was to determine if, among low-risk nulliparous women, elective induction of labor at 39 weeks, compared with expectant management, would reduce the rate of adverse outcomes.

The primary outcome was a composite: perinatal death or severe neonatal complications (need for respiratory support within 72 hours of birth, Apgar score of ≤ 3 at 5 minutes, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, seizures, infection [confirmed sepsis or pneumonia], meconium aspiration syndrome, birth trauma [bone fracture, neurologic injury, or retinal damage], intracranial or subgaleal hemorrhage, or hypotension requiring vasopressor support). The secondary outcomes included CD, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, number of hours in the labor and delivery (L&D) unit, length of postpartum hospital stay, and assessment of satisfaction with labor process.

Mothers induced at 39 weeks fared better, while neonatal outcomes were similar. Of 22,533 eligible women, 6,106 (27%) were randomized: 3,062 were assigned to the induction group, and, 3,044 to the expectant management group. The primary composite outcome—perinatal death or severe neonatal complications—was similar in both groups (4.3% in the induction group vs 5.4% in the expectant management group).

However, women who were induced had significantly lower rates of:

- CD (18.6% with induction vs 22.2% for expectant management; relative risk [RR], 0.84; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76–0.93)

- hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (9.1% vs 14.1%; RR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.56–0.74)

- neonatal respiratory support (3.0% vs. 4.2%; RR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55–0.93).

In addition, although women in the induction group had a longer stay in the L&D unit (an expected outcome), the overall postpartum length of stay was shorter. Finally, women in the induction group had higher patient satisfaction scores, with less pain and more control reported during labor.

Continue to: What about uncommon adverse outcomes compared at 39 vs 41 weeks?

What about uncommon adverse outcomes compared at 39 vs 41 weeks?

Due to the study’s sample size, ARRIVE investigators could not ascertain if uncommon adverse outcomes (maternal admission to intensive care unit or neonatal seizure) are significantly more common at 40 and 41 weeks, than at 39 weeks.

To address the issue of uncommon adverse outcomes, Chen and colleagues analyzed the US Vital Statistics datasets to compare composite maternal and neonatal morbidity among low-risk nulliparous women with nonanomalous singleton gestations who labored at 39 to 41 weeks.5 The primary outcome was composite neonatal morbidity that included Apgar score < 5 at 5 minutes, assisted ventilation longer than 6 hours, seizure, or neonatal mortality. The secondary outcome was composite maternal morbidity that included intensive care unit admission, blood transfusion, uterine rupture, or unplanned hysterectomy.

The investigators found that from 2011–2015, among 19.8 million live births in the United States, there were 3.3 million live births among low-risk nulliparous women. Among these women, 43% delivered at 39 weeks’ gestation, 41% at 40 weeks, and 15% at 41 weeks. The overall rate of composite neonatal morbidity was 8.8 per 1,000 live births; compared with those who delivered at 39 weeks, composite neonatal morbidity was significantly higher for those delivered at 40 (adjusted RR [aRR], 1.22; 95% CI, 1.19–1.25) and 41 weeks (aRR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.49–1.58).

The secondary outcome, the overall rate of composite maternal morbidity, was 2.8 per 1,000 live births. As with composite neonatal morbidity, the risk of composite maternal morbidity was also significantly higher for those delivered at 40 (aRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.14–1.25) and 41 weeks’ gestation (aRR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.47–1.65) than at 39 weeks.

Thus, among low-risk nulliparous pregnancies, there is an incremental increase in the rates of composite neonatal and maternal morbidity from 39 to 41 weeks.

Is induction of labor at 39 weeks feasible?

As the evidence demonstrating multiple benefits of 39-week inductions increases, concerns regarding the feasibility and cost of implementation in the current US health care system mount. A planned secondary analysis of the ARRIVE trial evaluated medical resource utilization among low-risk nulliparous women randomly assigned to elective induction at 39 weeks or expectant management.6 Resource utilization was compared between the 2 groups during the antepartum period, delivery admission, and from discharge to 8 weeks postpartum.

For the antepartum period, women in the induction group were significantly less likely than women undergoing expectant management to have at least 1: office visit for routine prenatal care (32.4% vs 68.4%), unanticipated office visit (0.5% vs 2.6%), urgent care/emergency department/triage visit (16.2% vs 44.3%), or hospital admission (0.8% vs 2.2%). When admitted for delivery, as expected, women in the induction group spent significantly more time on the L&D unit (14 hours vs 20 hours) and were more likely to receive interventions for induction (cervical ripening, oxytocin, intrauterine pressure catheter placement). However, they required magnesium sulfate and antibiotics significantly less frequently. For the postpartum group comparison, women in the induction group and their neonates had a significantly shorter duration of hospital stay.

In summary, the investigators found that, compared to women undergoing expectant management, women undergoing elective induction spent longer duration in L&D units and utilized more resources, but they required significantly fewer antepartum clinic and hospital visits, treatments for hypertensive disorders or chorioamnionitis, and had shorter duration of postpartum length of stay.

Continue to: Is induction of labor at 39 weeks cost-effective?

Is induction of labor at 39 weeks cost-effective?

Hersh and colleagues performed a cost-effectiveness analysis for induction of labor at 39 weeks versus expectant management for low-risk nulliparous women.7 Based on 2016 National Vital Statistics Data, there were 3.5 million term births in the United States. Following the exclusion of high-risk pregnancies and term parous low-risk pregnancies, a theoretical cohort of 1.6 million low-risk nulliparous women was included in the analysis. A decision-tree analytic model was created, in which the initial node stratified low-risk nulliparous women into 2 categories: elective induction at 39 weeks and expectant management. Probabilities of maternal and neonatal outcomes were derived from the literature.

Maternal outcomes included hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and delivery mode. Neonatal outcomes included macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, stillbirth, and neonatal death. Costs of clinic and triage visits, induction of labor, modes of delivery, and maternal and neonatal outcomes were derived from previous studies and adjusted for inflation to 2018 dollars. Finally, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were calculated for mothers and neonates and were then used to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of elective induction of labor at 39 weeks. Following accepted standards, the threshold for cost-effectiveness was set at $100,000/QALYs or less.

Induction at 39 weeks comes in lower cost-wise than the standard threshold for QALY. In their analysis, the investigators found that if all 1.6 million women in their theoretical cohort underwent an elective induction of labor at 39 weeks (rather than expectant management), there would be 54,498 fewer CDs, 79,152 fewer cases of hypertensive disorders, 795 fewer cases of stillbirth, and 11 fewer neonatal deaths. Due to the decreased CD rates, the investigators did project an estimated 86 additional cases of neonatal brachial plexus injury. Using these estimates, costs, and utilities, the authors demonstrated that, compared with expectant management, elective induction of labor at 39 weeks was marginally cost-effective with an ICER of $87,692 per QALY, which was lower than the cost-effectiveness threshold of $100,000 per QALY.

Based on additional sensitivity analyses, the authors concluded that cost-effectiveness of elective induction of labor varied based on variations in model inputs. Specifically, the authors demonstrated that cost-effectiveness of induction of labor varied based on labor induction techniques, modes of delivery, and fluctuations in the rates of CD in induction versus expectant management groups.

Despite these theoretically imputed findings, the authors acknowledged the limitations of their study. Their cost-effectiveness model did not account for costs associated with long-term health impact of CD and hypertensive disease of pregnancy. Additionally, their model did not account for an increase in cost and resource utilization associated with increased time on L&D units to accommodate women undergoing induction. Furthermore, the analysis did not take into account the bundled payments for vaginal versus CDs, which are increasing in prevalence. Lastly, the analysis did not consider the incremental increase in severe neonatal and maternal morbidity from 39 to 41 weeks that Chen et al found in their study.5

Will ARRIVE finally arrive?

Cognizant of the medical and economic benefits of 39-week inductions, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology published a joint practice advisory recommending “shared decision-making” when counseling low-risk women about induction.8 While more research is needed to validate the aforementioned findings, particularly in regard to resource utilization, the ARRIVE trial and its associated analyses suggest that a reconsideration to deliver term low-risk nulliparous women at 39 weeks is warranted.

In summary, the overwhelming evidence suggests that, among low-risk nulliparous women there are maternal and neonatal benefits with delivery at 39 weeks, as compared with expectant management. Logistical concerns should not interfere with women’s desideratum for optimal outcomes.

- Vardo JH, Thornburg LL, Glantz JC. Maternal and neonatal morbidity among nulliparous women undergoing elective induction of labor. J Reprod Med. 2011;56:25-30.

- Dunne C, Da Silva O, Schmidt G, Natale R. Outcomes of elective labour induction and elective caesarean section in low-risk pregnancies between 37 and 41 weeks’ gestation. J Obstet Gynaecol Can . 2009;31:1124-1130.

- Guerra GV, Cecatti JG, Souza JP, et al; WHO Global Survey on Maternal Perinatal Health in Latin America Study Group. Elective induction versus spontaneous labour in Latin America. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:657-665.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

- Chen HY, Grobman WA, Blackwell SC, et al. Women at 39-41 weeks of gestation among low-risk nulliparous women, several adverse outcomes—including neonatal mortality—are significantly more frequent with delivery at 40 or 41 weeks of gestation than at 39 weeks. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:729-737.

- Grobman WA, et al. Resource utilization among low-risk nulliparas randomized to elective induction at 39 weeks or expectant management. Oral presentation at: Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine 39th Annual Pregnancy Meeting; February 11-16, 2019; Las Vegas, NV.

- Hersh AR, Skeith AE, Sargent JA, et al. Induction of labor at 39 weeks of gestation vs. expectant management for low-risk nulliparous women: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol . February 12, 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.ajog.2019.02.017.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Publications Committee. SMFM statement on elective induction of labor in low-risk nulliparous women at term: the ARRIVE trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. August 9, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.08.009.

- Vardo JH, Thornburg LL, Glantz JC. Maternal and neonatal morbidity among nulliparous women undergoing elective induction of labor. J Reprod Med. 2011;56:25-30.

- Dunne C, Da Silva O, Schmidt G, Natale R. Outcomes of elective labour induction and elective caesarean section in low-risk pregnancies between 37 and 41 weeks’ gestation. J Obstet Gynaecol Can . 2009;31:1124-1130.

- Guerra GV, Cecatti JG, Souza JP, et al; WHO Global Survey on Maternal Perinatal Health in Latin America Study Group. Elective induction versus spontaneous labour in Latin America. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:657-665.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

- Chen HY, Grobman WA, Blackwell SC, et al. Women at 39-41 weeks of gestation among low-risk nulliparous women, several adverse outcomes—including neonatal mortality—are significantly more frequent with delivery at 40 or 41 weeks of gestation than at 39 weeks. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:729-737.

- Grobman WA, et al. Resource utilization among low-risk nulliparas randomized to elective induction at 39 weeks or expectant management. Oral presentation at: Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine 39th Annual Pregnancy Meeting; February 11-16, 2019; Las Vegas, NV.

- Hersh AR, Skeith AE, Sargent JA, et al. Induction of labor at 39 weeks of gestation vs. expectant management for low-risk nulliparous women: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol . February 12, 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.ajog.2019.02.017.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Publications Committee. SMFM statement on elective induction of labor in low-risk nulliparous women at term: the ARRIVE trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. August 9, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.08.009.

Treating the pregnant patient with opioid addiction

OBG Management : How has the opioid crisis affected women in general?

Mishka Terplan, MD: Everyone is aware that we are experiencing a massive opioid crisis in the United States, and from a historical perspective, this is at least the third or fourth significant opioid epidemic in our nation’s history.1 It is similar in some ways to the very first one, which also featured a large proportion of women and also was driven initially by physician prescribing practices. However, the magnitude of this crisis is unparalleled compared with prior opioid epidemics.

There are lots of reasons why women are overrepresented in this crisis. There are gender-based differences in pain—chronic pain syndromes are more common in women. In addition, we have a gender bias in prescribing opioids and prescribe more opioids to women (especially older women) than to men. Cultural differences also contribute. As providers, we tend not to think of women as people who use drugs or people who develop addictions the same way as we think of these risks and behaviors for men. Therefore, compared with men, we are less likely to screen, assess, or refer women for substance use, misuse, and addiction. All of this adds up to creating a crisis in which women are increasingly the face of the epidemic.

OBG Management : What are the concerns about opioid addiction and pregnant women specifically?

Dr. Terplan: Addiction is a chronic condition, just like diabetes or depression, and the same principles that we think of in terms of optimizing maternal and newborn health apply to addiction. Ideally, we want, for women with chronic diseases to have stable disease at the time of conception and through pregnancy. We know this maximizes birth outcomes.

Unfortunately, there is a massive treatment gap in the United States. Most people with addiction receive no treatment. Only 11% of people with a substance use disorder report receipt of treatment. By contrast, more than 70% of people with depression, hypertension, or diabetes receive care. This treatment gap is also present in pregnancy. Among use disorders, treatment receipt is highest for opioid use disorder; however, nationally, at best, 25% of pregnant women with opioid addiction receive any care.

In other words, when we encounter addiction clinically, it is often untreated addiction. Therefore, many times providers will have women presenting to care who are both pregnant and have untreated addiction. From both a public health and a clinical practice perspective, the salient distinction is not between people with addiction and those without but between people with treated disease and people with untreated disease.

Untreated addiction is a serious medical condition. It is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight infants. It is associated with acquisition and transmission of HIV and hepatitis C. It is associated with overdose and overdose death. By contrast, treated addiction is associated with term delivery and normal weight infants. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder stabilize the intrauterine environment and allow for normal fetal growth. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder help to structure and stabilize the mom’s social circumstance, providing a platform to deliver prenatal care and essential social services. And pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder protect women and their fetuses from overdose and from overdose deaths. The goal of management of addiction in pregnancy is treatment of the underlying condition, treating the addiction.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : What should the ObGyn do when faced with a patient who might have an addiction?

Dr. Terplan: The good news is that there are lots of recently published guidance documents from the World Health Organization,2 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG),3 and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA),4 and there have been a whole series of trainings throughout the United States organized by both ACOG and SAMHSA.

There is also a collaboration between ACOG and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) to provide buprenorphine waiver trainings specifically designed for ObGyns. Check both the ACOG and ASAM pages for details. I encourage every provider to get a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. There are about 30 ObGyns who are also board certified in addiction medicine in the United States, and all of us are more than happy to help our colleagues in the clinical care of this population, a population that all of us really enjoy taking care of.

Although care in pregnancy is important, we must not forget about the postpartum period. Generally speaking, women do quite well during pregnancy in terms of treatment. Postpartum, however, is a vulnerable period, where relapse happens, where gaps in care happen, where child welfare involvement and sometimes child removal happens, which can be very stressful for anyone much less somebody with a substance use disorder. Recent data demonstrate that one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the US in from overdose, and most of these deaths occur in the postpartum period.5 Regardless of what happens during pregnancy, it is essential that we be able to link and continue care for women with opioid use disorder throughout the postpartum period.

OBG Management : How do you treat opioid use disorder in pregnancy?

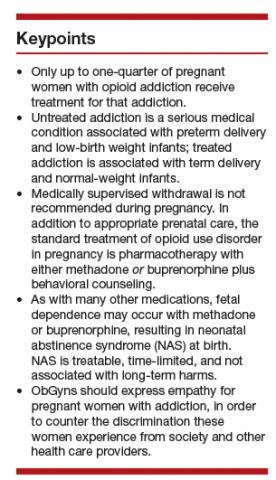

Dr. Terplan: The standard of care for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy is pharmacotherapy with either methadone or buprenorphine (TABLE) plus behavioral counseling—ideally, co-located with prenatal care. The evidence base for pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder in pregnancy is supported by every single professional society that has ever issued guidance on this, from the World Health Organization to ACOG, to ASAM, to the Royal College in the UK as well as Canadian and Australian obstetrics and gynecology societies; literally every single professional society supports medication.

The core principle of maternal fetal medicine rests upon the fact that chronic conditions need to be treated and that treated illness improves birth outcomes. For both maternal and fetal health, treated addiction is way better than untreated addiction. One concern people have regarding methadone and buprenorphine is the development of dependence. Dependence is a physiologic effect of medication and occurs with opioids, as well as with many other medications, such as antidepressants and most hypertensive agents. For the fetus, dependence means that at the time of delivery, the infant may go into withdrawal, which is also called neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal abstinence syndrome is an expected outcome of in-utero opioid exposure. It is a time-limited and treatable condition. Prospective data do not demonstrate any long-term harms among infants whose mothers received pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder during pregnancy.6

The treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome is costly, especially when in a neonatal intensive care unit. It can be quite concerning to a new mother to have an infant that has to spend extra time in the hospital and sometimes be medicated for management of withdrawal.

There has been a renewed interest amongst ObGyns in investigating medically-supervised withdrawal during pregnancy. Although there are remaining questions, overall, the literature does not support withdrawal during pregnancy—mostly because withdrawal is associated with relapse, and relapse is associated with cessation of care (both prenatal care and addiction treatment), acquisition and transmission of HIV and Hepatitis C, and overdose and overdose death. The pertinent clinical and public health goal is the treatment of the chronic condition of addiction during pregnancy. The standard of care remains pharmacotherapy plus behavioral counseling for the treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy.

Clinical care, however, is both evidence-based and person-centered. All of us who have worked in this field, long before there was attention to the opioid crisis, all of us have provided medically-supervised withdrawal of a pregnant person, and that is because we understand the principles of care. When evidence-based care conflicts with person-centered care, the ethical course is the provision of person-centered care. Patients have the right of refusal. If someone wants to discontinue medication, I have tapered the medication during pregnancy, but continued to provide (and often increase) behavioral counseling and prenatal care.

Treated addiction is better for the fetus than untreated addiction. Untreated opioid addiction is associated with preterm birth and low birth weight. These obstetric risks are not because of the opioid per se, but because of the repeated cycles of withdrawal that an individual with untreated addiction experiences. People with untreated addiction are not getting “high” when they use, they are just becoming a little bit less sick. It is this repeated cycle of withdrawal that stresses the fetus, which leads to preterm delivery and low birth weight.

Medications for opioid use disorder are long-acting and dosed daily. In contrast to the repeated cycles of fetal withdrawal in untreated addiction, pharmacotherapy stabilizes the intrauterine environment. There is no cyclic, repeated, stressful withdrawal, and consequentially, the fetus grows normally and delivers at term. Obstetric risk is from repeated cyclic withdrawal more than from opioid exposure itself.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Research reports that women are not using all of the opioids that are prescribed to them after a cesarean delivery. What are the risks for addiction in this setting?

Dr. Terplan: I mark a distinction between use (ie, using something as prescribed) and misuse, which means using a prescribed medication not in the manner in which it was prescribed, or using somebody else’s medications, or using an illicit substance. And I differentiate use and misuse from addiction, which is a behavioral condition, a disease. There has been a lot of attention paid to opioid prescribing in general and in particular postdelivery and post–cesarean delivery, which is one of the most common operative procedures in the United States.

It seems clear from the literature that we have overprescribed opioids postdelivery, and a small number of women, about 1 in 300 will continue an opioid script.7 This means that 1 in 300 women who received an opioid prescription following delivery present for care and get another opioid prescription filled. Now, that is a small number at the level of the individual, but because we do so many cesarean deliveries, this is a large number of women at the level of the population. This does not mean, however, that 1 in 300 women who received opioids after cesarean delivery are going to become addicted to them. It just means that 1 in 300 will continue the prescription. Prescription continuation is a risk factor for opioid misuse, and opioid misuse is on the pathway toward addiction.

Most people who use substances do not develop an addiction to that substance. We know from the opioid literature that at most only 10% of people who receive chronic opioid therapy will meet criteria for opioid use disorder.8 Now 10% is not 100%, nor is it 0%, but because we prescribed so many opioids to so many people for so long, the absolute number of people with opioid use disorder from physician opioid prescribing is large, even though the risk at the level of the individual is not as large as people think.

OBG Management : From your experience in treating addiction during pregnancy, are there clinical pearls you would like to share with ObGyns?

Dr. Terplan: There are a couple of takeaways. One is that all women are motivated to maximize their health and that of their baby to be, and every pregnant woman engages in behavioral change; in fact most women quit or cutback substance use during pregnancy. But some can’t. Those that can’t likely have a substance use disorder. We think of addiction as a chronic condition, centered in the brain, but the primary symptoms of addiction are behaviors. The salient feature of addiction is continued use despite adverse consequences; using something that you know is harming yourself and others but you can’t stop using it. In other words, continuing substance use during pregnancy. When we see clinically a pregnant woman who is using a substance, 99% of the time we are seeing a pregnant woman who has the condition of addiction, and what she needs is treatment. She does not need to be told that injecting heroin is unsafe for her and her fetus, she knows that. What she needs is treatment.

The second point is that pregnant women who use drugs and pregnant women with addiction experience a real specific and strong form of discrimination by providers, by other people with addiction, by the legal system, and by their friends and families. Caring for people who have substance use disorder is grounded in human rights, which means treating people with dignity and respect. It is important for providers to have empathy, especially for pregnant people who use drugs, to counter the discrimination they experience from society and from other health care providers.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Are there specific ways in which ObGyns can show empathy when speaking with a pregnant woman who likely has addiction?

Dr. Terplan: In general when we talk to people about drug use, it is important to ask their permission to talk about it. For example, “Is it okay if I ask you some questions about smoking, drinking, and other drugs?” If someone says, “No, I don’t want you to ask those questions,” we have to respect that. Assessment of substance use should be a universal part of all medical care, as substance use, misuse, and addiction are essential domains of wellness, but I think we should ask permission before screening.

One of the really good things about prenatal care is that people come back; we have multiple visits across the gestational period. The behavioral work of addiction treatment rests upon a strong therapeutic alliance. If you do not respect your patient, then there is no way you can achieve a therapeutic alliance. Asking permission, and then respecting somebody’s answers, I think goes a really long way to establishing a strong therapeutic alliance, which is the basis of any medical care.

- Terplan M. Women and the opioid crisis: historical context and public health solutions. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:195-199.

- Management of substance abuse. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/treatment_opioid_dependence/en/. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e81-e94.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Clinical guidance for treating pregnant and parenting women with opioid use disorder and their infants. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18-5054. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018.

- Metz TD, Royner P, Hoffman MC, et al. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1233-1240.

- Kaltenbach K, O’Grady E, Heil SH, et al. Prenatal exposure to methadone or buprenorphine: early childhood developmental outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:40-49.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naive women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1-353.e18.

OBG Management : How has the opioid crisis affected women in general?

Mishka Terplan, MD: Everyone is aware that we are experiencing a massive opioid crisis in the United States, and from a historical perspective, this is at least the third or fourth significant opioid epidemic in our nation’s history.1 It is similar in some ways to the very first one, which also featured a large proportion of women and also was driven initially by physician prescribing practices. However, the magnitude of this crisis is unparalleled compared with prior opioid epidemics.

There are lots of reasons why women are overrepresented in this crisis. There are gender-based differences in pain—chronic pain syndromes are more common in women. In addition, we have a gender bias in prescribing opioids and prescribe more opioids to women (especially older women) than to men. Cultural differences also contribute. As providers, we tend not to think of women as people who use drugs or people who develop addictions the same way as we think of these risks and behaviors for men. Therefore, compared with men, we are less likely to screen, assess, or refer women for substance use, misuse, and addiction. All of this adds up to creating a crisis in which women are increasingly the face of the epidemic.

OBG Management : What are the concerns about opioid addiction and pregnant women specifically?

Dr. Terplan: Addiction is a chronic condition, just like diabetes or depression, and the same principles that we think of in terms of optimizing maternal and newborn health apply to addiction. Ideally, we want, for women with chronic diseases to have stable disease at the time of conception and through pregnancy. We know this maximizes birth outcomes.

Unfortunately, there is a massive treatment gap in the United States. Most people with addiction receive no treatment. Only 11% of people with a substance use disorder report receipt of treatment. By contrast, more than 70% of people with depression, hypertension, or diabetes receive care. This treatment gap is also present in pregnancy. Among use disorders, treatment receipt is highest for opioid use disorder; however, nationally, at best, 25% of pregnant women with opioid addiction receive any care.

In other words, when we encounter addiction clinically, it is often untreated addiction. Therefore, many times providers will have women presenting to care who are both pregnant and have untreated addiction. From both a public health and a clinical practice perspective, the salient distinction is not between people with addiction and those without but between people with treated disease and people with untreated disease.

Untreated addiction is a serious medical condition. It is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight infants. It is associated with acquisition and transmission of HIV and hepatitis C. It is associated with overdose and overdose death. By contrast, treated addiction is associated with term delivery and normal weight infants. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder stabilize the intrauterine environment and allow for normal fetal growth. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder help to structure and stabilize the mom’s social circumstance, providing a platform to deliver prenatal care and essential social services. And pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder protect women and their fetuses from overdose and from overdose deaths. The goal of management of addiction in pregnancy is treatment of the underlying condition, treating the addiction.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : What should the ObGyn do when faced with a patient who might have an addiction?

Dr. Terplan: The good news is that there are lots of recently published guidance documents from the World Health Organization,2 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG),3 and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA),4 and there have been a whole series of trainings throughout the United States organized by both ACOG and SAMHSA.

There is also a collaboration between ACOG and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) to provide buprenorphine waiver trainings specifically designed for ObGyns. Check both the ACOG and ASAM pages for details. I encourage every provider to get a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. There are about 30 ObGyns who are also board certified in addiction medicine in the United States, and all of us are more than happy to help our colleagues in the clinical care of this population, a population that all of us really enjoy taking care of.