User login

Should oxytocin and a Foley catheter be used concurrently for cervical ripening in induction of labor?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

The concurrent use of mechanical and pharmacologic cervical ripening is an area of active interest. Combination methods typically involve placing a Foley catheter and simultaneously administering either prostaglandins or oxytocin. Despite the long-standing belief that using 2 cervical ripening agents simultaneously has no benefit compared with using only 1 cervical ripening agent, several recent large randomized trials are challenging this paradigm by suggesting that using 2 cervical ripening agents together may in fact be superior.

Related Article:

Q: Following cesarean delivery, what is the optimal oxytocin infusion duration to prevent postpartum bleeding?

Details of the study

Schoen and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial that included 184 nulliparous and 139 multiparous women with an unfavorable cervix undergoing induction of labor after 24 weeks of gestation. All participants had a Foley catheter placed intracervically and then were randomly assigned to receive either concurrent oxytocin infusion within 60 minutes or no oxytocin until after Foley catheter expulsion or removal. Nulliparous and multiparous women were randomly assigned separately. Women with premature rupture of membranes and with 1 prior cesarean delivery were included in the trial, but women were excluded if they were in active labor, had suspected abruption, or had a nonreassuring fetal tracing.

The study was powered to detect a 20% increase in total delivery rate within 24 hours of Foley placement, which was the primary study outcome. Secondary induction outcomes of note included time to Foley expulsion, time to second stage, delivery within 12 hours, total time to delivery, duration of oxytocin use, and mode of delivery. Several maternal and neonatal outcomes also were examined, including tachysystole, chorioamnionitis, meconium, postpartum hemorrhage, birth weight, maternal intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and neonatal ICU admission.

Related Article:

Start offering antenatal corticosteroids to women delivering between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation to improve newborn outcomes

Women receiving concurrent Foley and oxytocin delivered sooner. Among nulliparous women, the overall rate of delivery within 24 hours of Foley catheter placement was 64% in the Foley with concurrent oxytocin group compared with 43% in those who received a Foley catheter alone followed by oxytocin (P = .003). The overall time to delivery was 5 hours less in nulliparous women who received combination cervical ripening compared with those who had a Foley catheter alone.

Similarly, multiparous women had an overall rate of delivery within 24 hours of 87% in the concurrent Foley and oxytocin group compared with 72% in women who received Foley catheter followed by oxytocin (P = .022).

Meanwhile, there were no statistically significant differences in mode of delivery between groups for either multiparous or nulliparous patients, and there were no differences in adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes between groups.

Related Article:

How and when umbilical cord gas analysis can justify your obstetric management

Study strengths and weaknesses

This well-designed, randomized control trial clearly demonstrated that the combination of Foley catheter and oxytocin for cervical ripening increases the rate of delivery within 24 hours compared with use of Foley catheter alone. This finding is consistent with those of 2 other large randomized trials in the past 2 years that similarly demonstrated reduced time to delivery when oxytocin infusion was used in combination with Foley catheter compared with Foley alone.1,2

Despite these findings, important questions remain regarding concurrent use of cervical ripening agents. The study by Schoen and colleagues does not address the other option for dual cervical ripening, namely, concurrent use of Foley catheter and misoprostol. Several large randomized trials using Foley catheter with vaginal or oral misoprostol demonstrated reduced time to delivery compared with using either method alone.1,3,4 Only 1 randomized study has compared these 2 dual cervical ripening regimens head-to-head; that study demonstrated that the misoprostol and Foley combination significantly reduced time to delivery compared with combining Foley catheter and oxytocin together.1

Additionally, it is important to note that the study by Schoen and colleagues was not large enough to adequately evaluate potential safety risks with dual combination cervical ripening. More safety data are needed before combination cervical ripening methods can be recommended universally.

-- Christina A. Penfield, MD, MPH, and Deborah A. Wing, MD, MBA

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Levine LD, Downes KL, Elovitz MA, Parry S, Sammel MD, Srinivas SK. Mechanical and pharmacologic methods of labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):1357–1364.

- Connolly KA, Kohari KS, Rekawek P, et al. A randomized trial of Foley balloon induction of labor trial in nulliparas (FIAT-N). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):392.e1–e6.

- Carbone JF, Tuuli MG, Fogertey PJ, Roehl KA, Macones GA. Combination of Foley bulb and vaginal misoprostol compared with vaginal misoprostol alone for cervical ripening and labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 pt 1):247–252.

- Hill JB, Thigpen BD, Bofill JA, Magann E, Moore LE, Martin JN Jr. A randomized clinical trial comparing vaginal misoprostol versus cervical Foley plus oral misoprostol for cervical ripening and labor induction. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26(1):33–38.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

The concurrent use of mechanical and pharmacologic cervical ripening is an area of active interest. Combination methods typically involve placing a Foley catheter and simultaneously administering either prostaglandins or oxytocin. Despite the long-standing belief that using 2 cervical ripening agents simultaneously has no benefit compared with using only 1 cervical ripening agent, several recent large randomized trials are challenging this paradigm by suggesting that using 2 cervical ripening agents together may in fact be superior.

Related Article:

Q: Following cesarean delivery, what is the optimal oxytocin infusion duration to prevent postpartum bleeding?

Details of the study

Schoen and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial that included 184 nulliparous and 139 multiparous women with an unfavorable cervix undergoing induction of labor after 24 weeks of gestation. All participants had a Foley catheter placed intracervically and then were randomly assigned to receive either concurrent oxytocin infusion within 60 minutes or no oxytocin until after Foley catheter expulsion or removal. Nulliparous and multiparous women were randomly assigned separately. Women with premature rupture of membranes and with 1 prior cesarean delivery were included in the trial, but women were excluded if they were in active labor, had suspected abruption, or had a nonreassuring fetal tracing.

The study was powered to detect a 20% increase in total delivery rate within 24 hours of Foley placement, which was the primary study outcome. Secondary induction outcomes of note included time to Foley expulsion, time to second stage, delivery within 12 hours, total time to delivery, duration of oxytocin use, and mode of delivery. Several maternal and neonatal outcomes also were examined, including tachysystole, chorioamnionitis, meconium, postpartum hemorrhage, birth weight, maternal intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and neonatal ICU admission.

Related Article:

Start offering antenatal corticosteroids to women delivering between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation to improve newborn outcomes

Women receiving concurrent Foley and oxytocin delivered sooner. Among nulliparous women, the overall rate of delivery within 24 hours of Foley catheter placement was 64% in the Foley with concurrent oxytocin group compared with 43% in those who received a Foley catheter alone followed by oxytocin (P = .003). The overall time to delivery was 5 hours less in nulliparous women who received combination cervical ripening compared with those who had a Foley catheter alone.

Similarly, multiparous women had an overall rate of delivery within 24 hours of 87% in the concurrent Foley and oxytocin group compared with 72% in women who received Foley catheter followed by oxytocin (P = .022).

Meanwhile, there were no statistically significant differences in mode of delivery between groups for either multiparous or nulliparous patients, and there were no differences in adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes between groups.

Related Article:

How and when umbilical cord gas analysis can justify your obstetric management

Study strengths and weaknesses

This well-designed, randomized control trial clearly demonstrated that the combination of Foley catheter and oxytocin for cervical ripening increases the rate of delivery within 24 hours compared with use of Foley catheter alone. This finding is consistent with those of 2 other large randomized trials in the past 2 years that similarly demonstrated reduced time to delivery when oxytocin infusion was used in combination with Foley catheter compared with Foley alone.1,2

Despite these findings, important questions remain regarding concurrent use of cervical ripening agents. The study by Schoen and colleagues does not address the other option for dual cervical ripening, namely, concurrent use of Foley catheter and misoprostol. Several large randomized trials using Foley catheter with vaginal or oral misoprostol demonstrated reduced time to delivery compared with using either method alone.1,3,4 Only 1 randomized study has compared these 2 dual cervical ripening regimens head-to-head; that study demonstrated that the misoprostol and Foley combination significantly reduced time to delivery compared with combining Foley catheter and oxytocin together.1

Additionally, it is important to note that the study by Schoen and colleagues was not large enough to adequately evaluate potential safety risks with dual combination cervical ripening. More safety data are needed before combination cervical ripening methods can be recommended universally.

-- Christina A. Penfield, MD, MPH, and Deborah A. Wing, MD, MBA

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

The concurrent use of mechanical and pharmacologic cervical ripening is an area of active interest. Combination methods typically involve placing a Foley catheter and simultaneously administering either prostaglandins or oxytocin. Despite the long-standing belief that using 2 cervical ripening agents simultaneously has no benefit compared with using only 1 cervical ripening agent, several recent large randomized trials are challenging this paradigm by suggesting that using 2 cervical ripening agents together may in fact be superior.

Related Article:

Q: Following cesarean delivery, what is the optimal oxytocin infusion duration to prevent postpartum bleeding?

Details of the study

Schoen and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial that included 184 nulliparous and 139 multiparous women with an unfavorable cervix undergoing induction of labor after 24 weeks of gestation. All participants had a Foley catheter placed intracervically and then were randomly assigned to receive either concurrent oxytocin infusion within 60 minutes or no oxytocin until after Foley catheter expulsion or removal. Nulliparous and multiparous women were randomly assigned separately. Women with premature rupture of membranes and with 1 prior cesarean delivery were included in the trial, but women were excluded if they were in active labor, had suspected abruption, or had a nonreassuring fetal tracing.

The study was powered to detect a 20% increase in total delivery rate within 24 hours of Foley placement, which was the primary study outcome. Secondary induction outcomes of note included time to Foley expulsion, time to second stage, delivery within 12 hours, total time to delivery, duration of oxytocin use, and mode of delivery. Several maternal and neonatal outcomes also were examined, including tachysystole, chorioamnionitis, meconium, postpartum hemorrhage, birth weight, maternal intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and neonatal ICU admission.

Related Article:

Start offering antenatal corticosteroids to women delivering between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation to improve newborn outcomes

Women receiving concurrent Foley and oxytocin delivered sooner. Among nulliparous women, the overall rate of delivery within 24 hours of Foley catheter placement was 64% in the Foley with concurrent oxytocin group compared with 43% in those who received a Foley catheter alone followed by oxytocin (P = .003). The overall time to delivery was 5 hours less in nulliparous women who received combination cervical ripening compared with those who had a Foley catheter alone.

Similarly, multiparous women had an overall rate of delivery within 24 hours of 87% in the concurrent Foley and oxytocin group compared with 72% in women who received Foley catheter followed by oxytocin (P = .022).

Meanwhile, there were no statistically significant differences in mode of delivery between groups for either multiparous or nulliparous patients, and there were no differences in adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes between groups.

Related Article:

How and when umbilical cord gas analysis can justify your obstetric management

Study strengths and weaknesses

This well-designed, randomized control trial clearly demonstrated that the combination of Foley catheter and oxytocin for cervical ripening increases the rate of delivery within 24 hours compared with use of Foley catheter alone. This finding is consistent with those of 2 other large randomized trials in the past 2 years that similarly demonstrated reduced time to delivery when oxytocin infusion was used in combination with Foley catheter compared with Foley alone.1,2

Despite these findings, important questions remain regarding concurrent use of cervical ripening agents. The study by Schoen and colleagues does not address the other option for dual cervical ripening, namely, concurrent use of Foley catheter and misoprostol. Several large randomized trials using Foley catheter with vaginal or oral misoprostol demonstrated reduced time to delivery compared with using either method alone.1,3,4 Only 1 randomized study has compared these 2 dual cervical ripening regimens head-to-head; that study demonstrated that the misoprostol and Foley combination significantly reduced time to delivery compared with combining Foley catheter and oxytocin together.1

Additionally, it is important to note that the study by Schoen and colleagues was not large enough to adequately evaluate potential safety risks with dual combination cervical ripening. More safety data are needed before combination cervical ripening methods can be recommended universally.

-- Christina A. Penfield, MD, MPH, and Deborah A. Wing, MD, MBA

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Levine LD, Downes KL, Elovitz MA, Parry S, Sammel MD, Srinivas SK. Mechanical and pharmacologic methods of labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):1357–1364.

- Connolly KA, Kohari KS, Rekawek P, et al. A randomized trial of Foley balloon induction of labor trial in nulliparas (FIAT-N). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):392.e1–e6.

- Carbone JF, Tuuli MG, Fogertey PJ, Roehl KA, Macones GA. Combination of Foley bulb and vaginal misoprostol compared with vaginal misoprostol alone for cervical ripening and labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 pt 1):247–252.

- Hill JB, Thigpen BD, Bofill JA, Magann E, Moore LE, Martin JN Jr. A randomized clinical trial comparing vaginal misoprostol versus cervical Foley plus oral misoprostol for cervical ripening and labor induction. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26(1):33–38.

- Levine LD, Downes KL, Elovitz MA, Parry S, Sammel MD, Srinivas SK. Mechanical and pharmacologic methods of labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):1357–1364.

- Connolly KA, Kohari KS, Rekawek P, et al. A randomized trial of Foley balloon induction of labor trial in nulliparas (FIAT-N). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):392.e1–e6.

- Carbone JF, Tuuli MG, Fogertey PJ, Roehl KA, Macones GA. Combination of Foley bulb and vaginal misoprostol compared with vaginal misoprostol alone for cervical ripening and labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 pt 1):247–252.

- Hill JB, Thigpen BD, Bofill JA, Magann E, Moore LE, Martin JN Jr. A randomized clinical trial comparing vaginal misoprostol versus cervical Foley plus oral misoprostol for cervical ripening and labor induction. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26(1):33–38.

Are women of advanced maternal age at increased risk for severe maternal morbidity?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

While numerous studies have investigated the risk of perinatal outcomes with advancing maternal age, the primary objective of a recent study by Lisonkova and colleagues was to examine the association between advancing maternal age and severe maternal morbidities and mortality.

Details of the study

The population-based retrospective cohort study compared age-specific rates of severe maternal morbidities and mortality among 828,269 pregnancies in Washington state between 2003 and 2013. Singleton births to women 15 to 60 years of age were included; out-of-hospital births were excluded. Information was obtained by linking the Birth Events Record Database (which includes information on maternal, pregnancy, and labor and delivery characteristics and birth outcomes), and the Comprehensive Hospital Abstract Reporting System database (which includes diagnostic and procedural codes for all hospitalizations in Washington state).

The primary objective was to examine the association between age and severe maternal morbidities. Maternal morbidities were divided into categories: antepartum hemorrhage, respiratory morbidity, thromboembolism, cerebrovascular morbidity, acute cardiac morbidity, severe postpartum hemorrhage, maternal sepsis, renal failure, obstetric shock, complications of anesthesia and obstetric interventions, and need for life-saving procedures. A composite outcome, comprised of severe maternal morbidities, intensive care unit admission, and maternal mortality, was also created.

Rates of severe morbidities were compared for age groups 15 to 19, 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, and ≥45 years to the referent category (25 to 29 years). Additional comparisons were also performed for ages 45 to 49 and ≥50 years for the composite and for morbidities with high incidence. Logistic regression and sensitivity analyses were used to control for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, underlying medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics.

Severe maternal morbidities demonstrated a J-shaped association with age: the lowest rates of morbidity were observed in women 20 to 34 years of age, and steeply increasing rates of morbidity were observed for women aged 40 and older. One notable exception was the rate of sepsis, which was increased in teen mothers compared with all other groups.

The unadjusted rate of the composite outcome of severe maternal morbidity and mortality was 2.1% in teenagers, 1.5% among women 25 to 29 years, 2.3% among those aged 40 to 44, and 3.6% among women aged 45 and older.

Although rates were somewhat attenuated after adjustment for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, chronic medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics, most morbidities remained significantly increased among women aged 39 years and older, including the composite outcome. Among the individual morbidities considered, increased risk was highest for renal failure, amniotic fluid embolism, cardiac morbidity, and shock, with adjusted odds ratios of 2.0 or greater for women older than 39 years.

Related article:

Reducing maternal mortality in the United States—Let’s get organized!

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study contributes substantially to the existing literature that demonstrates higher rates of pregnancy-associated morbidities in women of increasing maternal age.1,2 Prior studies in this area focused on perinatal morbidity and mortality and on obstetric outcomes such as cesarean delivery.3–5 This large-scale study examined the association between advancing maternal age and a variety of serious maternal morbidities. In another study, Callaghan and Berg found a similar pattern among mortalities, with high rates of mortality attributable to hemorrhage, embolism, and cardiomyopathy in women aged 40 years and older.1

Exclusion of multiple gestations. As in any study, we must consider the methodology, and it is notable that Lisonkova and colleagues’ study excluded multiple gestations. Given the association with advanced maternal age, assisted reproductive technology, and the incidence of multiple gestations, a high rate of multiple gestations would be expected among women of advanced maternal age. (Generally, maternal age of at least 35 years is considered “advanced,” with greater than 40 years “very advanced.”) Since multiple gestations tend to be associated with increases in morbidity, excluding these pregnancies would likely bias the study results toward the null. If multiple gestations had been included, the rates of serious maternal morbidities in older women might be even higher than those demonstrated, potentially strengthening the associations reported here.

This large, retrospective study (level II evidence) suggests that women of advancing age are at significantly increased risk of severe maternal morbidities, even after controlling for preexisting medical conditions. We therefore recommend that clinicians inform and counsel women who are considering pregnancy at an advanced age, and those considering oocyte cryopreservation as a means of extending their reproductive life span, about the increased maternal morbidities associated with pregnancy at age 40 and older.

-- Amy E. Judy, MD, MPH, and Yasser Y. El-Sayed, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Callaghan WM, Berg CJ. Pregnancy-related mortality among women aged 35 years and older, United States, 1991–1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):1015–1021.

- McCall SJ, Nair M, Knight M. Factors associated with maternal mortality at advanced maternal age: a population-based case-control study. BJOG. 2017;124(8):1225–1233.

- Yogev Y, Melamed N, Bardin R, Tenenbaum-Gavish K, Ben-Shitrit G, Ben-Haroush A. Pregnancy outcome at extremely advanced maternal age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):558.e1–e7.

- Gilbert WM, Nesbitt TS, Danielsen B. Childbearing beyond age 40: pregnancy outcome in 24,032 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(1):9–14.

- Luke B, Brown MB. Elevated risks of pregnancy complications and adverse outcomes with increasing maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(5):1264–1272.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

While numerous studies have investigated the risk of perinatal outcomes with advancing maternal age, the primary objective of a recent study by Lisonkova and colleagues was to examine the association between advancing maternal age and severe maternal morbidities and mortality.

Details of the study

The population-based retrospective cohort study compared age-specific rates of severe maternal morbidities and mortality among 828,269 pregnancies in Washington state between 2003 and 2013. Singleton births to women 15 to 60 years of age were included; out-of-hospital births were excluded. Information was obtained by linking the Birth Events Record Database (which includes information on maternal, pregnancy, and labor and delivery characteristics and birth outcomes), and the Comprehensive Hospital Abstract Reporting System database (which includes diagnostic and procedural codes for all hospitalizations in Washington state).

The primary objective was to examine the association between age and severe maternal morbidities. Maternal morbidities were divided into categories: antepartum hemorrhage, respiratory morbidity, thromboembolism, cerebrovascular morbidity, acute cardiac morbidity, severe postpartum hemorrhage, maternal sepsis, renal failure, obstetric shock, complications of anesthesia and obstetric interventions, and need for life-saving procedures. A composite outcome, comprised of severe maternal morbidities, intensive care unit admission, and maternal mortality, was also created.

Rates of severe morbidities were compared for age groups 15 to 19, 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, and ≥45 years to the referent category (25 to 29 years). Additional comparisons were also performed for ages 45 to 49 and ≥50 years for the composite and for morbidities with high incidence. Logistic regression and sensitivity analyses were used to control for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, underlying medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics.

Severe maternal morbidities demonstrated a J-shaped association with age: the lowest rates of morbidity were observed in women 20 to 34 years of age, and steeply increasing rates of morbidity were observed for women aged 40 and older. One notable exception was the rate of sepsis, which was increased in teen mothers compared with all other groups.

The unadjusted rate of the composite outcome of severe maternal morbidity and mortality was 2.1% in teenagers, 1.5% among women 25 to 29 years, 2.3% among those aged 40 to 44, and 3.6% among women aged 45 and older.

Although rates were somewhat attenuated after adjustment for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, chronic medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics, most morbidities remained significantly increased among women aged 39 years and older, including the composite outcome. Among the individual morbidities considered, increased risk was highest for renal failure, amniotic fluid embolism, cardiac morbidity, and shock, with adjusted odds ratios of 2.0 or greater for women older than 39 years.

Related article:

Reducing maternal mortality in the United States—Let’s get organized!

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study contributes substantially to the existing literature that demonstrates higher rates of pregnancy-associated morbidities in women of increasing maternal age.1,2 Prior studies in this area focused on perinatal morbidity and mortality and on obstetric outcomes such as cesarean delivery.3–5 This large-scale study examined the association between advancing maternal age and a variety of serious maternal morbidities. In another study, Callaghan and Berg found a similar pattern among mortalities, with high rates of mortality attributable to hemorrhage, embolism, and cardiomyopathy in women aged 40 years and older.1

Exclusion of multiple gestations. As in any study, we must consider the methodology, and it is notable that Lisonkova and colleagues’ study excluded multiple gestations. Given the association with advanced maternal age, assisted reproductive technology, and the incidence of multiple gestations, a high rate of multiple gestations would be expected among women of advanced maternal age. (Generally, maternal age of at least 35 years is considered “advanced,” with greater than 40 years “very advanced.”) Since multiple gestations tend to be associated with increases in morbidity, excluding these pregnancies would likely bias the study results toward the null. If multiple gestations had been included, the rates of serious maternal morbidities in older women might be even higher than those demonstrated, potentially strengthening the associations reported here.

This large, retrospective study (level II evidence) suggests that women of advancing age are at significantly increased risk of severe maternal morbidities, even after controlling for preexisting medical conditions. We therefore recommend that clinicians inform and counsel women who are considering pregnancy at an advanced age, and those considering oocyte cryopreservation as a means of extending their reproductive life span, about the increased maternal morbidities associated with pregnancy at age 40 and older.

-- Amy E. Judy, MD, MPH, and Yasser Y. El-Sayed, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

While numerous studies have investigated the risk of perinatal outcomes with advancing maternal age, the primary objective of a recent study by Lisonkova and colleagues was to examine the association between advancing maternal age and severe maternal morbidities and mortality.

Details of the study

The population-based retrospective cohort study compared age-specific rates of severe maternal morbidities and mortality among 828,269 pregnancies in Washington state between 2003 and 2013. Singleton births to women 15 to 60 years of age were included; out-of-hospital births were excluded. Information was obtained by linking the Birth Events Record Database (which includes information on maternal, pregnancy, and labor and delivery characteristics and birth outcomes), and the Comprehensive Hospital Abstract Reporting System database (which includes diagnostic and procedural codes for all hospitalizations in Washington state).

The primary objective was to examine the association between age and severe maternal morbidities. Maternal morbidities were divided into categories: antepartum hemorrhage, respiratory morbidity, thromboembolism, cerebrovascular morbidity, acute cardiac morbidity, severe postpartum hemorrhage, maternal sepsis, renal failure, obstetric shock, complications of anesthesia and obstetric interventions, and need for life-saving procedures. A composite outcome, comprised of severe maternal morbidities, intensive care unit admission, and maternal mortality, was also created.

Rates of severe morbidities were compared for age groups 15 to 19, 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, and ≥45 years to the referent category (25 to 29 years). Additional comparisons were also performed for ages 45 to 49 and ≥50 years for the composite and for morbidities with high incidence. Logistic regression and sensitivity analyses were used to control for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, underlying medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics.

Severe maternal morbidities demonstrated a J-shaped association with age: the lowest rates of morbidity were observed in women 20 to 34 years of age, and steeply increasing rates of morbidity were observed for women aged 40 and older. One notable exception was the rate of sepsis, which was increased in teen mothers compared with all other groups.

The unadjusted rate of the composite outcome of severe maternal morbidity and mortality was 2.1% in teenagers, 1.5% among women 25 to 29 years, 2.3% among those aged 40 to 44, and 3.6% among women aged 45 and older.

Although rates were somewhat attenuated after adjustment for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, chronic medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics, most morbidities remained significantly increased among women aged 39 years and older, including the composite outcome. Among the individual morbidities considered, increased risk was highest for renal failure, amniotic fluid embolism, cardiac morbidity, and shock, with adjusted odds ratios of 2.0 or greater for women older than 39 years.

Related article:

Reducing maternal mortality in the United States—Let’s get organized!

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study contributes substantially to the existing literature that demonstrates higher rates of pregnancy-associated morbidities in women of increasing maternal age.1,2 Prior studies in this area focused on perinatal morbidity and mortality and on obstetric outcomes such as cesarean delivery.3–5 This large-scale study examined the association between advancing maternal age and a variety of serious maternal morbidities. In another study, Callaghan and Berg found a similar pattern among mortalities, with high rates of mortality attributable to hemorrhage, embolism, and cardiomyopathy in women aged 40 years and older.1

Exclusion of multiple gestations. As in any study, we must consider the methodology, and it is notable that Lisonkova and colleagues’ study excluded multiple gestations. Given the association with advanced maternal age, assisted reproductive technology, and the incidence of multiple gestations, a high rate of multiple gestations would be expected among women of advanced maternal age. (Generally, maternal age of at least 35 years is considered “advanced,” with greater than 40 years “very advanced.”) Since multiple gestations tend to be associated with increases in morbidity, excluding these pregnancies would likely bias the study results toward the null. If multiple gestations had been included, the rates of serious maternal morbidities in older women might be even higher than those demonstrated, potentially strengthening the associations reported here.

This large, retrospective study (level II evidence) suggests that women of advancing age are at significantly increased risk of severe maternal morbidities, even after controlling for preexisting medical conditions. We therefore recommend that clinicians inform and counsel women who are considering pregnancy at an advanced age, and those considering oocyte cryopreservation as a means of extending their reproductive life span, about the increased maternal morbidities associated with pregnancy at age 40 and older.

-- Amy E. Judy, MD, MPH, and Yasser Y. El-Sayed, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Callaghan WM, Berg CJ. Pregnancy-related mortality among women aged 35 years and older, United States, 1991–1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):1015–1021.

- McCall SJ, Nair M, Knight M. Factors associated with maternal mortality at advanced maternal age: a population-based case-control study. BJOG. 2017;124(8):1225–1233.

- Yogev Y, Melamed N, Bardin R, Tenenbaum-Gavish K, Ben-Shitrit G, Ben-Haroush A. Pregnancy outcome at extremely advanced maternal age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):558.e1–e7.

- Gilbert WM, Nesbitt TS, Danielsen B. Childbearing beyond age 40: pregnancy outcome in 24,032 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(1):9–14.

- Luke B, Brown MB. Elevated risks of pregnancy complications and adverse outcomes with increasing maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(5):1264–1272.

- Callaghan WM, Berg CJ. Pregnancy-related mortality among women aged 35 years and older, United States, 1991–1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):1015–1021.

- McCall SJ, Nair M, Knight M. Factors associated with maternal mortality at advanced maternal age: a population-based case-control study. BJOG. 2017;124(8):1225–1233.

- Yogev Y, Melamed N, Bardin R, Tenenbaum-Gavish K, Ben-Shitrit G, Ben-Haroush A. Pregnancy outcome at extremely advanced maternal age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):558.e1–e7.

- Gilbert WM, Nesbitt TS, Danielsen B. Childbearing beyond age 40: pregnancy outcome in 24,032 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(1):9–14.

- Luke B, Brown MB. Elevated risks of pregnancy complications and adverse outcomes with increasing maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(5):1264–1272.

Obesity medicine: How to incorporate it into your practice

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Resources

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Resources

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Resources

Is sentinel lymph node mapping associated with acceptable performance characteristics for the detection of nodal metastases in women with endometrial cancer?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

The role of lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer has evolved considerably over the last 30 years. While pathologic assessment of the nodes provides important information to tailor adjuvant therapy, 2 randomized trials both reported no survival benefit in women who underwent lymphadenectomy compared with hysterectomy alone.1,2 Further, these trials revealed that lymphadenectomy was associated with significant short- and long-term sequelae.

SLN biopsy, a procedure in which a small number of nodes that represent the first drainage basins of a primary tumor are removed, has been proposed as an alternative to traditional lymphadenectomy. Although SLN biopsy is commonly used for other solid tumors, few large, multicenter studies have been conducted to evaluate the technique’s safety in endometrial cancer.

Related article:

2016 Update on cancer

Details of the study

The Fluorescence Imaging for Robotic Endometrial Sentinel lymph node biopsy (FIRES) trial was a prospective trial evaluating the performance characteristics of SLN biopsy in women with clinical stage 1 endometrial cancer at 10 sites in the United States. After cervical injection of indocyanine green, patients underwent robot-assisted hysterectomy with SLN biopsy followed by pelvic lymphadenectomy. Para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed at the discretion of the attending surgeon. The study’s primary end point was sensitivity of SLN biopsy for detecting metastatic disease in women who had mapping.

Over approximately 3 years, 385 patients were enrolled. Overall, 86% of patients had mapping of at least 1 SLN and 52% had bilateral mapping. Positive nodes were found in 12% of the study population. Among women who had SLNs identified, 35 of 36 nodal metastases were identified (97% sensitivity). Negative SLNs correctly predicted the absence of metastases (negative predictive value) in 99.6% of patients.

Overall, the procedure was well tolerated. Adverse events were noted in 9% of patients, and approximately two-thirds were considered serious adverse events. The most common adverse events were neurologic complications, respiratory distress, nausea and vomiting, and bowel injury in 3 patients. One ureteral injury occurred during SLN biopsy.

Related article:

Does laparoscopic versus open abdominal surgery for stage I endometrial cancer affect oncologic outcomes?

Study strengths and weaknesses

The FIRES study provides strong evidence for the effectiveness of SLN biopsy in women with apparent early stage endometrial cancer. The procedure not only was highly accurate in identifying nodal disease but it also had acceptable adverse events. Further, many of the benefits of SLN biopsy, such as a reduction in lymphedema, will require long-term follow-up.

Consider study results in context. As oncologists consider the role of SLN biopsy in practice, this work should be interpreted in the context of the study design. The study was performed by only 18 surgeons at 10 centers. Prior to study initiation, each site and surgeon underwent formal training and observation to ensure that the technique for SLN biopsy was adequate. Clearly, there will be a learning curve for SLN biopsy, and this study’s results may not immediately be generalizable.

Despite rigorous quality control procedures, there was no nodal mapping in 48% of the hemi-pelvises. In practice, these patients require lymph node dissection. The authors estimated that 50% of patients would still require lymphadenectomy (40% unilateral, 10% bilateral) if SLN mapping was used in routine practice. In addition, while the FIRES trial included women with high-risk histologies, the majority of patients had low-risk, endometrioid tumors. Further study will help to define performance of SLN biopsy in populations at higher risk for nodal metastases.

--Jason D. Wright, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707–1716.

- ASTEC Study Group, Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet. 2009;373(9658):125–136.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

The role of lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer has evolved considerably over the last 30 years. While pathologic assessment of the nodes provides important information to tailor adjuvant therapy, 2 randomized trials both reported no survival benefit in women who underwent lymphadenectomy compared with hysterectomy alone.1,2 Further, these trials revealed that lymphadenectomy was associated with significant short- and long-term sequelae.

SLN biopsy, a procedure in which a small number of nodes that represent the first drainage basins of a primary tumor are removed, has been proposed as an alternative to traditional lymphadenectomy. Although SLN biopsy is commonly used for other solid tumors, few large, multicenter studies have been conducted to evaluate the technique’s safety in endometrial cancer.

Related article:

2016 Update on cancer

Details of the study

The Fluorescence Imaging for Robotic Endometrial Sentinel lymph node biopsy (FIRES) trial was a prospective trial evaluating the performance characteristics of SLN biopsy in women with clinical stage 1 endometrial cancer at 10 sites in the United States. After cervical injection of indocyanine green, patients underwent robot-assisted hysterectomy with SLN biopsy followed by pelvic lymphadenectomy. Para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed at the discretion of the attending surgeon. The study’s primary end point was sensitivity of SLN biopsy for detecting metastatic disease in women who had mapping.

Over approximately 3 years, 385 patients were enrolled. Overall, 86% of patients had mapping of at least 1 SLN and 52% had bilateral mapping. Positive nodes were found in 12% of the study population. Among women who had SLNs identified, 35 of 36 nodal metastases were identified (97% sensitivity). Negative SLNs correctly predicted the absence of metastases (negative predictive value) in 99.6% of patients.

Overall, the procedure was well tolerated. Adverse events were noted in 9% of patients, and approximately two-thirds were considered serious adverse events. The most common adverse events were neurologic complications, respiratory distress, nausea and vomiting, and bowel injury in 3 patients. One ureteral injury occurred during SLN biopsy.

Related article:

Does laparoscopic versus open abdominal surgery for stage I endometrial cancer affect oncologic outcomes?

Study strengths and weaknesses

The FIRES study provides strong evidence for the effectiveness of SLN biopsy in women with apparent early stage endometrial cancer. The procedure not only was highly accurate in identifying nodal disease but it also had acceptable adverse events. Further, many of the benefits of SLN biopsy, such as a reduction in lymphedema, will require long-term follow-up.

Consider study results in context. As oncologists consider the role of SLN biopsy in practice, this work should be interpreted in the context of the study design. The study was performed by only 18 surgeons at 10 centers. Prior to study initiation, each site and surgeon underwent formal training and observation to ensure that the technique for SLN biopsy was adequate. Clearly, there will be a learning curve for SLN biopsy, and this study’s results may not immediately be generalizable.

Despite rigorous quality control procedures, there was no nodal mapping in 48% of the hemi-pelvises. In practice, these patients require lymph node dissection. The authors estimated that 50% of patients would still require lymphadenectomy (40% unilateral, 10% bilateral) if SLN mapping was used in routine practice. In addition, while the FIRES trial included women with high-risk histologies, the majority of patients had low-risk, endometrioid tumors. Further study will help to define performance of SLN biopsy in populations at higher risk for nodal metastases.

--Jason D. Wright, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

The role of lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer has evolved considerably over the last 30 years. While pathologic assessment of the nodes provides important information to tailor adjuvant therapy, 2 randomized trials both reported no survival benefit in women who underwent lymphadenectomy compared with hysterectomy alone.1,2 Further, these trials revealed that lymphadenectomy was associated with significant short- and long-term sequelae.

SLN biopsy, a procedure in which a small number of nodes that represent the first drainage basins of a primary tumor are removed, has been proposed as an alternative to traditional lymphadenectomy. Although SLN biopsy is commonly used for other solid tumors, few large, multicenter studies have been conducted to evaluate the technique’s safety in endometrial cancer.

Related article:

2016 Update on cancer

Details of the study

The Fluorescence Imaging for Robotic Endometrial Sentinel lymph node biopsy (FIRES) trial was a prospective trial evaluating the performance characteristics of SLN biopsy in women with clinical stage 1 endometrial cancer at 10 sites in the United States. After cervical injection of indocyanine green, patients underwent robot-assisted hysterectomy with SLN biopsy followed by pelvic lymphadenectomy. Para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed at the discretion of the attending surgeon. The study’s primary end point was sensitivity of SLN biopsy for detecting metastatic disease in women who had mapping.

Over approximately 3 years, 385 patients were enrolled. Overall, 86% of patients had mapping of at least 1 SLN and 52% had bilateral mapping. Positive nodes were found in 12% of the study population. Among women who had SLNs identified, 35 of 36 nodal metastases were identified (97% sensitivity). Negative SLNs correctly predicted the absence of metastases (negative predictive value) in 99.6% of patients.

Overall, the procedure was well tolerated. Adverse events were noted in 9% of patients, and approximately two-thirds were considered serious adverse events. The most common adverse events were neurologic complications, respiratory distress, nausea and vomiting, and bowel injury in 3 patients. One ureteral injury occurred during SLN biopsy.

Related article:

Does laparoscopic versus open abdominal surgery for stage I endometrial cancer affect oncologic outcomes?

Study strengths and weaknesses

The FIRES study provides strong evidence for the effectiveness of SLN biopsy in women with apparent early stage endometrial cancer. The procedure not only was highly accurate in identifying nodal disease but it also had acceptable adverse events. Further, many of the benefits of SLN biopsy, such as a reduction in lymphedema, will require long-term follow-up.

Consider study results in context. As oncologists consider the role of SLN biopsy in practice, this work should be interpreted in the context of the study design. The study was performed by only 18 surgeons at 10 centers. Prior to study initiation, each site and surgeon underwent formal training and observation to ensure that the technique for SLN biopsy was adequate. Clearly, there will be a learning curve for SLN biopsy, and this study’s results may not immediately be generalizable.

Despite rigorous quality control procedures, there was no nodal mapping in 48% of the hemi-pelvises. In practice, these patients require lymph node dissection. The authors estimated that 50% of patients would still require lymphadenectomy (40% unilateral, 10% bilateral) if SLN mapping was used in routine practice. In addition, while the FIRES trial included women with high-risk histologies, the majority of patients had low-risk, endometrioid tumors. Further study will help to define performance of SLN biopsy in populations at higher risk for nodal metastases.

--Jason D. Wright, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707–1716.

- ASTEC Study Group, Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet. 2009;373(9658):125–136.

- Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707–1716.

- ASTEC Study Group, Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet. 2009;373(9658):125–136.

Intra-amniotic sludge: Does its presence rule out cerclage for short cervix?

CASE: Woman with short cervix, intra-amniotic sludge, and prior preterm delivery

An asymptomatic 32-year-old woman with a prior preterm delivery, presently pregnant with a singleton at 17 weeks of gestation, underwent transvaginal ultrasonography and was found to have a cervical length of 22 mm and dense intra-amniotic sludge. She received one dose of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) at 16 weeks of gestation. What are your next steps in management?

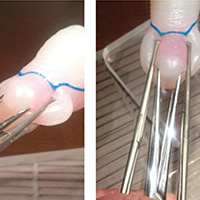

Intra-amniotic sludge is a conundrum

Intra-amniotic sludge is a sonographic finding of free-floating, hyperechoic, particulate matter in the amniotic fluid close to the internal os. The precise nature of this material varies, and it may include blood, meconium, or vernix and may signal inflammation or infection. In a retrospective case-control study, 27% of asymptomatic women with sludge and a short cervix had positive amniotic fluid cultures, and 27% had evidence of inflammation in the amniotic fluid (>50 white blood cells/mm3).1 In a separate report, the authors proposed that "the detection of amniotic fluid 'sludge' represents a sign that microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and an inflammatory process are in progress."2

Benefit of cerclage in high-risk women. Several systematic reviews have highlighted the benefit of cerclage for women with a singleton pregnancy, short cervix, and previous preterm birth or second-trimester loss (ultrasound-indicated cerclage for high-risk women).3 Cerclage is presumed to work by providing some degree of structural support and by maintaining a barrier to protect the fetal membranes against exposure to ascending pathogens.4

Since dense intra-amniotic sludge may represent chronic intra-amniotic infection, can cerclage still be expected to be beneficial when microbiologic invasion of the amniotic cavity already has occurred? Furthermore, intra-amniotic infection has been cited as a possible complication of ultrasound-indicated cerclage, with a rate of 10%.5 The traditional view is that the presence of subclinical intra-amniotic infection may further increase this risk and therefore should be considered a contraindication to cerclage.6

Evaluating the patient for cerclage placement

The patient history and physical examination should focus on the signs and symptoms of labor, vaginal bleeding, amniotic membrane rupture, and intra-amniotic infection. Particular attention should be paid to maternal temperature, pulse, and the presence of uterine tenderness or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. A sterile speculum examination followed by digital examination would complement the ultrasonography evaluation in assessing cervical dilation and effacement. The ultrasonography evaluation should be completed to confirm a viable pregnancy with accurate dating and the absence of detectable fetal anomalies.

Currently, evidence is insufficient for recommending routine amniocentesis to exclude intra-amniotic infection in an asymptomatic woman prior to ultrasound-indicated cerclage, even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge, as there are no data demonstrating improved outcomes.4 In addition, intra-amniotic sludge has been associated with intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation in the form of microbial biofilms, which may prevent detection of infection by routine culture techniques.7

Related Article:

Universal cervical length screening–saving babies lives

Study results offer limited guidance

Data are limited on the clinical implications of intra-amniotic sludge in women with cervical cerclage. In a retrospective cohort of 177 patients with cerclage, 60 had evidence of sludge and 46 of those with sludge underwent ultrasound-indicated cerclage.8 There were no significant differences in the mean gestational age at delivery, neonatal outcomes, rate of preterm delivery, preterm premature rupture of membranes, or intra-amniotic infection between women with or without intra-amniotic sludge. A subanalysis was performed comparing women with sludge detected before or after cerclage and, again, no difference was found in measured outcomes.

Similarly, in a small (N = 20) retrospective review of the Arabin pessary used as a noninvasive intervention for short cervix, the presence of intra-amniotic sludge in 5 cases did not appear to impact outcomes.9

Case patient: How would you manage her care?

Based on her obstetric history and ultrasonography findings, the patient described in the case vignette is at high risk for preterm delivery. The presence of both intra-amniotic sludge and short cervix is associated with an increased risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. After evaluating for clinical intra-amniotic infection and performing a work-up for other contraindications to cerclage placement, cerclage placement may be offered--even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge.

The next practical question is whether 17P, already started, should be continued after cerclage placement. From the literature on 17P, it is unclear whether progesterone provides additional benefit. One randomized, placebo-controlled study in women with at least 2 preterm deliveries or mid-trimester losses and cerclage in place showed that the 17P-treated women had a significant reduction in preterm delivery compared with the control group, from 37.8% to 16.1%.10

By contrast, in a secondary analysis of a randomized trial evaluating cerclage in high-risk women with short cervix in the current pregnancy, addition of 17P to cerclage was not beneficial.11 Results of 2 retrospective cohort studies showed the same lack of difference on preterm delivery rates with the addition of 17P.12,13

Accepting that the interpretation of these data is challenging, in our practice we would choose to continue the progesterone supplementation, siding with other recently expressed expert opinions.14

The bottom line

While clinical intra-amniotic infection is a contraindication to cerclage, there is no evidence to support withholding cerclage from eligible women due to the presence of intra-amniotic fluid sludge alone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Romero R, et al. Clinical significance of the presence of amniotic fluid "sludge" in asymptomatic patients at high risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):706-714.

- Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, et al. What is amniotic fluid "sludge"? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):793-798.

- Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Roberts D, Jorgensen AL. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD008991.

- Abbott D, To M, Shennan A. Cervical cerclage: a review of current evidence. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;52(3):220-223.

- Drassinower D, Poggi SH, Landy HJ, Gilo N, Benson JE, Ghidini A. Perioperative complications of history-indicated and ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):53.e1-e5.

- Mays JK, Figueroa R, Shah J, Khakoo H, Kaminsky S, Tejani N. Amniocentesis for selection before rescue cerclage. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(5):652-655.

- Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Erez IO, et al. Clinical significance of early (<20 weeks) vs late (20-24 weeks) detection of sonographic short cervix in asymptomatic women in the mid-trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):471-481.

- Gorski LA, Huang WH, Iriye BK, Hancock J. Clinical implication of intra-amniotic sludge on ultrasound in patients with cervical cerclage. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):482-485.

- Ting YH, Lao TT, Wa Law LW, et al. Arabin cerclage pessary in the management of cervical insufficiency. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(12):2693-2695.

- Yemini M, Borenstein R, Dreazen E, et al. Prevention of premature labor by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(5):574-577.

- Berghella V, Figueroa D, Szychowski JM, et al; Vaginal Ultrasound Trial Consortium. 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for the prevention of preterm birth in women with prior preterm birth and a short cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):351.e1-e6.

- Rebarber A, Cleary-Goldman J, Istwan NB, et al. The use of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) in women with cervical cerclage. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(5):271-275.

- Stetson B, Hibbard JU, Wilkins I, Leftwich H. Outcomes with cerclage alone compared with cerclage plus 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):983-988.

- Iams JD. Identification of candidates for progesterone: why, who, how, and when? Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1317-1326.

CASE: Woman with short cervix, intra-amniotic sludge, and prior preterm delivery

An asymptomatic 32-year-old woman with a prior preterm delivery, presently pregnant with a singleton at 17 weeks of gestation, underwent transvaginal ultrasonography and was found to have a cervical length of 22 mm and dense intra-amniotic sludge. She received one dose of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) at 16 weeks of gestation. What are your next steps in management?

Intra-amniotic sludge is a conundrum

Intra-amniotic sludge is a sonographic finding of free-floating, hyperechoic, particulate matter in the amniotic fluid close to the internal os. The precise nature of this material varies, and it may include blood, meconium, or vernix and may signal inflammation or infection. In a retrospective case-control study, 27% of asymptomatic women with sludge and a short cervix had positive amniotic fluid cultures, and 27% had evidence of inflammation in the amniotic fluid (>50 white blood cells/mm3).1 In a separate report, the authors proposed that "the detection of amniotic fluid 'sludge' represents a sign that microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and an inflammatory process are in progress."2

Benefit of cerclage in high-risk women. Several systematic reviews have highlighted the benefit of cerclage for women with a singleton pregnancy, short cervix, and previous preterm birth or second-trimester loss (ultrasound-indicated cerclage for high-risk women).3 Cerclage is presumed to work by providing some degree of structural support and by maintaining a barrier to protect the fetal membranes against exposure to ascending pathogens.4

Since dense intra-amniotic sludge may represent chronic intra-amniotic infection, can cerclage still be expected to be beneficial when microbiologic invasion of the amniotic cavity already has occurred? Furthermore, intra-amniotic infection has been cited as a possible complication of ultrasound-indicated cerclage, with a rate of 10%.5 The traditional view is that the presence of subclinical intra-amniotic infection may further increase this risk and therefore should be considered a contraindication to cerclage.6

Evaluating the patient for cerclage placement

The patient history and physical examination should focus on the signs and symptoms of labor, vaginal bleeding, amniotic membrane rupture, and intra-amniotic infection. Particular attention should be paid to maternal temperature, pulse, and the presence of uterine tenderness or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. A sterile speculum examination followed by digital examination would complement the ultrasonography evaluation in assessing cervical dilation and effacement. The ultrasonography evaluation should be completed to confirm a viable pregnancy with accurate dating and the absence of detectable fetal anomalies.

Currently, evidence is insufficient for recommending routine amniocentesis to exclude intra-amniotic infection in an asymptomatic woman prior to ultrasound-indicated cerclage, even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge, as there are no data demonstrating improved outcomes.4 In addition, intra-amniotic sludge has been associated with intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation in the form of microbial biofilms, which may prevent detection of infection by routine culture techniques.7

Related Article:

Universal cervical length screening–saving babies lives

Study results offer limited guidance

Data are limited on the clinical implications of intra-amniotic sludge in women with cervical cerclage. In a retrospective cohort of 177 patients with cerclage, 60 had evidence of sludge and 46 of those with sludge underwent ultrasound-indicated cerclage.8 There were no significant differences in the mean gestational age at delivery, neonatal outcomes, rate of preterm delivery, preterm premature rupture of membranes, or intra-amniotic infection between women with or without intra-amniotic sludge. A subanalysis was performed comparing women with sludge detected before or after cerclage and, again, no difference was found in measured outcomes.

Similarly, in a small (N = 20) retrospective review of the Arabin pessary used as a noninvasive intervention for short cervix, the presence of intra-amniotic sludge in 5 cases did not appear to impact outcomes.9

Case patient: How would you manage her care?

Based on her obstetric history and ultrasonography findings, the patient described in the case vignette is at high risk for preterm delivery. The presence of both intra-amniotic sludge and short cervix is associated with an increased risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. After evaluating for clinical intra-amniotic infection and performing a work-up for other contraindications to cerclage placement, cerclage placement may be offered--even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge.

The next practical question is whether 17P, already started, should be continued after cerclage placement. From the literature on 17P, it is unclear whether progesterone provides additional benefit. One randomized, placebo-controlled study in women with at least 2 preterm deliveries or mid-trimester losses and cerclage in place showed that the 17P-treated women had a significant reduction in preterm delivery compared with the control group, from 37.8% to 16.1%.10

By contrast, in a secondary analysis of a randomized trial evaluating cerclage in high-risk women with short cervix in the current pregnancy, addition of 17P to cerclage was not beneficial.11 Results of 2 retrospective cohort studies showed the same lack of difference on preterm delivery rates with the addition of 17P.12,13

Accepting that the interpretation of these data is challenging, in our practice we would choose to continue the progesterone supplementation, siding with other recently expressed expert opinions.14

The bottom line

While clinical intra-amniotic infection is a contraindication to cerclage, there is no evidence to support withholding cerclage from eligible women due to the presence of intra-amniotic fluid sludge alone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: Woman with short cervix, intra-amniotic sludge, and prior preterm delivery

An asymptomatic 32-year-old woman with a prior preterm delivery, presently pregnant with a singleton at 17 weeks of gestation, underwent transvaginal ultrasonography and was found to have a cervical length of 22 mm and dense intra-amniotic sludge. She received one dose of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) at 16 weeks of gestation. What are your next steps in management?

Intra-amniotic sludge is a conundrum

Intra-amniotic sludge is a sonographic finding of free-floating, hyperechoic, particulate matter in the amniotic fluid close to the internal os. The precise nature of this material varies, and it may include blood, meconium, or vernix and may signal inflammation or infection. In a retrospective case-control study, 27% of asymptomatic women with sludge and a short cervix had positive amniotic fluid cultures, and 27% had evidence of inflammation in the amniotic fluid (>50 white blood cells/mm3).1 In a separate report, the authors proposed that "the detection of amniotic fluid 'sludge' represents a sign that microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and an inflammatory process are in progress."2

Benefit of cerclage in high-risk women. Several systematic reviews have highlighted the benefit of cerclage for women with a singleton pregnancy, short cervix, and previous preterm birth or second-trimester loss (ultrasound-indicated cerclage for high-risk women).3 Cerclage is presumed to work by providing some degree of structural support and by maintaining a barrier to protect the fetal membranes against exposure to ascending pathogens.4

Since dense intra-amniotic sludge may represent chronic intra-amniotic infection, can cerclage still be expected to be beneficial when microbiologic invasion of the amniotic cavity already has occurred? Furthermore, intra-amniotic infection has been cited as a possible complication of ultrasound-indicated cerclage, with a rate of 10%.5 The traditional view is that the presence of subclinical intra-amniotic infection may further increase this risk and therefore should be considered a contraindication to cerclage.6

Evaluating the patient for cerclage placement

The patient history and physical examination should focus on the signs and symptoms of labor, vaginal bleeding, amniotic membrane rupture, and intra-amniotic infection. Particular attention should be paid to maternal temperature, pulse, and the presence of uterine tenderness or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. A sterile speculum examination followed by digital examination would complement the ultrasonography evaluation in assessing cervical dilation and effacement. The ultrasonography evaluation should be completed to confirm a viable pregnancy with accurate dating and the absence of detectable fetal anomalies.

Currently, evidence is insufficient for recommending routine amniocentesis to exclude intra-amniotic infection in an asymptomatic woman prior to ultrasound-indicated cerclage, even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge, as there are no data demonstrating improved outcomes.4 In addition, intra-amniotic sludge has been associated with intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation in the form of microbial biofilms, which may prevent detection of infection by routine culture techniques.7

Related Article:

Universal cervical length screening–saving babies lives

Study results offer limited guidance

Data are limited on the clinical implications of intra-amniotic sludge in women with cervical cerclage. In a retrospective cohort of 177 patients with cerclage, 60 had evidence of sludge and 46 of those with sludge underwent ultrasound-indicated cerclage.8 There were no significant differences in the mean gestational age at delivery, neonatal outcomes, rate of preterm delivery, preterm premature rupture of membranes, or intra-amniotic infection between women with or without intra-amniotic sludge. A subanalysis was performed comparing women with sludge detected before or after cerclage and, again, no difference was found in measured outcomes.

Similarly, in a small (N = 20) retrospective review of the Arabin pessary used as a noninvasive intervention for short cervix, the presence of intra-amniotic sludge in 5 cases did not appear to impact outcomes.9

Case patient: How would you manage her care?

Based on her obstetric history and ultrasonography findings, the patient described in the case vignette is at high risk for preterm delivery. The presence of both intra-amniotic sludge and short cervix is associated with an increased risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. After evaluating for clinical intra-amniotic infection and performing a work-up for other contraindications to cerclage placement, cerclage placement may be offered--even in the presence of intra-amniotic sludge.

The next practical question is whether 17P, already started, should be continued after cerclage placement. From the literature on 17P, it is unclear whether progesterone provides additional benefit. One randomized, placebo-controlled study in women with at least 2 preterm deliveries or mid-trimester losses and cerclage in place showed that the 17P-treated women had a significant reduction in preterm delivery compared with the control group, from 37.8% to 16.1%.10

By contrast, in a secondary analysis of a randomized trial evaluating cerclage in high-risk women with short cervix in the current pregnancy, addition of 17P to cerclage was not beneficial.11 Results of 2 retrospective cohort studies showed the same lack of difference on preterm delivery rates with the addition of 17P.12,13

Accepting that the interpretation of these data is challenging, in our practice we would choose to continue the progesterone supplementation, siding with other recently expressed expert opinions.14

The bottom line

While clinical intra-amniotic infection is a contraindication to cerclage, there is no evidence to support withholding cerclage from eligible women due to the presence of intra-amniotic fluid sludge alone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Romero R, et al. Clinical significance of the presence of amniotic fluid "sludge" in asymptomatic patients at high risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):706-714.

- Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, et al. What is amniotic fluid "sludge"? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):793-798.

- Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Roberts D, Jorgensen AL. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD008991.

- Abbott D, To M, Shennan A. Cervical cerclage: a review of current evidence. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;52(3):220-223.

- Drassinower D, Poggi SH, Landy HJ, Gilo N, Benson JE, Ghidini A. Perioperative complications of history-indicated and ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):53.e1-e5.

- Mays JK, Figueroa R, Shah J, Khakoo H, Kaminsky S, Tejani N. Amniocentesis for selection before rescue cerclage. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(5):652-655.

- Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Erez IO, et al. Clinical significance of early (<20 weeks) vs late (20-24 weeks) detection of sonographic short cervix in asymptomatic women in the mid-trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):471-481.

- Gorski LA, Huang WH, Iriye BK, Hancock J. Clinical implication of intra-amniotic sludge on ultrasound in patients with cervical cerclage. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):482-485.

- Ting YH, Lao TT, Wa Law LW, et al. Arabin cerclage pessary in the management of cervical insufficiency. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(12):2693-2695.

- Yemini M, Borenstein R, Dreazen E, et al. Prevention of premature labor by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(5):574-577.

- Berghella V, Figueroa D, Szychowski JM, et al; Vaginal Ultrasound Trial Consortium. 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for the prevention of preterm birth in women with prior preterm birth and a short cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):351.e1-e6.

- Rebarber A, Cleary-Goldman J, Istwan NB, et al. The use of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) in women with cervical cerclage. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(5):271-275.

- Stetson B, Hibbard JU, Wilkins I, Leftwich H. Outcomes with cerclage alone compared with cerclage plus 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):983-988.

- Iams JD. Identification of candidates for progesterone: why, who, how, and when? Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1317-1326.

- Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Romero R, et al. Clinical significance of the presence of amniotic fluid "sludge" in asymptomatic patients at high risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):706-714.

- Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, et al. What is amniotic fluid "sludge"? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):793-798.

- Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Roberts D, Jorgensen AL. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD008991.

- Abbott D, To M, Shennan A. Cervical cerclage: a review of current evidence. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;52(3):220-223.

- Drassinower D, Poggi SH, Landy HJ, Gilo N, Benson JE, Ghidini A. Perioperative complications of history-indicated and ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):53.e1-e5.

- Mays JK, Figueroa R, Shah J, Khakoo H, Kaminsky S, Tejani N. Amniocentesis for selection before rescue cerclage. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(5):652-655.

- Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Erez IO, et al. Clinical significance of early (<20 weeks) vs late (20-24 weeks) detection of sonographic short cervix in asymptomatic women in the mid-trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):471-481.

- Gorski LA, Huang WH, Iriye BK, Hancock J. Clinical implication of intra-amniotic sludge on ultrasound in patients with cervical cerclage. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(4):482-485.

- Ting YH, Lao TT, Wa Law LW, et al. Arabin cerclage pessary in the management of cervical insufficiency. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(12):2693-2695.

- Yemini M, Borenstein R, Dreazen E, et al. Prevention of premature labor by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(5):574-577.

- Berghella V, Figueroa D, Szychowski JM, et al; Vaginal Ultrasound Trial Consortium. 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for the prevention of preterm birth in women with prior preterm birth and a short cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):351.e1-e6.

- Rebarber A, Cleary-Goldman J, Istwan NB, et al. The use of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) in women with cervical cerclage. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(5):271-275.

- Stetson B, Hibbard JU, Wilkins I, Leftwich H. Outcomes with cerclage alone compared with cerclage plus 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):983-988.

- Iams JD. Identification of candidates for progesterone: why, who, how, and when? Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1317-1326.

Does laparoscopic versus open abdominal surgery for stage I endometrial cancer affect oncologic outcomes?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

The objective of the study by Janda and colleagues (known as the “LACE” trial) was to evaluate the equivalency of total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) with staging versus the standard procedure, which is total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) with staging, for surgical management of women with presumed low-risk, early-stage endometrial cancer.

Related Article:

2016 Update on cancer

Details of the study

This nonblinded, randomized controlled multicenter equivalency trial included 760 women from Australia, New Zealand, and Hong Kong undergoing surgical management of presumed stage I uterine endometrioid adenocarcinoma. All surgeries were performed or supervised by trained gynecologic oncologists. Pelvic lymph node sampling was required but omission was permitted for: morbid obesity, low risk of metastasis based on frozen section results, medically unfit status, or institutional guidelines prohibiting the procedure. Patients were excluded for preoperative nonendometrioid histology, suspected ultimate FIGO stage II–IV based on preoperative imaging, or uterine size greater than 10 weeks’ gestation.

The primary outcome was disease-free survival, defined as the time from surgery to the date of first recurrence, which included disease progression, development of a new primary malignancy, or death. Secondary outcomes included disease recurrence, patterns of recurrence, and overall survival. A 7% difference in disease-free survival at 4.5 years postoperatively was prespecified and determined based on previously published literature.1–4