User login

Universal cervical length screening–saving babies lives

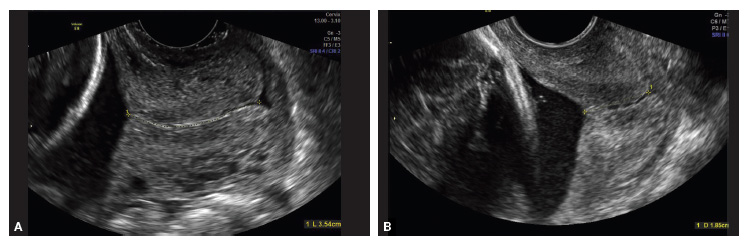

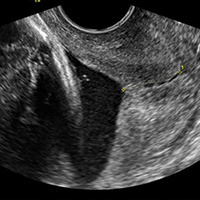

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) cervical length (CL) screening for prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) is among the most transformative clinical changes in obstetrics in the last decades. TVU CL screening should now be offered to all pregnant women: hence the appellative ‘universal CL screening.’

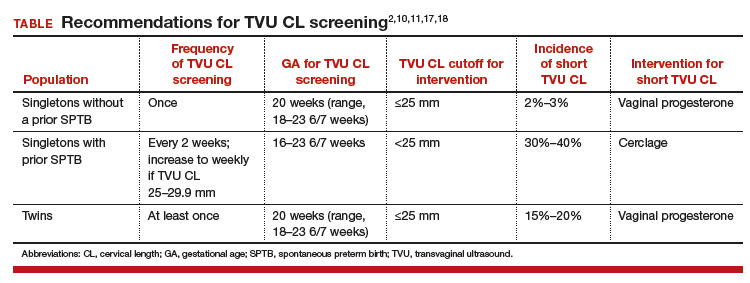

TVU CL screening is an excellent screening test for several reasons. It screens for SPTB, which is a clinically important, well-defined disease whose prevalence and natural history is known, and has an early recognizable asymptomatic phase in CL shortening detected by TVU. TVU CL screening is a well-described technique, safe and acceptable, with a reasonable cutoff (25 mm) now identified for all populations, and results are reproducible and accurate. There are hundreds of studies proving these facts. In the last 10 years, TVU measurement of CL as a screening test has been accepted1,2: it identifies women at risk for SPTB, and an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation) is effective in preventing SPTB. Screening and treatment of short cervix is cost-effective and readily available as an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation), is effective in preventing the outcome (SPTB), treating abnormal results is cost-effective, and facilities for screening are available and treatments are readily available.3–5 It is also important to emphasize that CL screening for prevention of SPTB should be done by TVU, and not by transabdominal ultrasound.6It is best to review TVU CL screening by populations: singletons without prior SPTB, singletons with prior SPTB, and twins (Table).

Related Article:

Can transabdominal ultrasound exclude short cervix?

Singletons without prior SPTB

Women with no previous SPTB who are carrying a singleton pregnancy is the population in which TVU CL could have the greatest impact on decreasing SPTB, for several reasons:

- Up to 60% to 90% of SPTB occur in this population.

- More than 90% of these women have risk factors for SPTB.7,8

- Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant 39% decrease in PTB at <33 weeks of gestation and a significant 38% decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 606 women without prior PTB.9,10

- Cost-effectiveness studies have shown that TVU CL screening in this specific population prevents thousands of preterm births, saves or improves from death or major morbidity 350 babies’ lives annually, and saves approximately $320,000 per year in the US alone.3 These numbers may be even higher now as the TVU CL cutoff for offering vaginal progesterone has moved in many centers from ≤20 mm to ≤25 mm, including more women (from about 0.8% to about 2% to 3%, respectively11) who benefit from screening.

- Real-world implementation studies have indeed shown significant decreases in SPTB when a policy of universal TVU CL screening in this specific population is implemented.12,13

Universal TVU CL screening recently called into question

In a recent article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association,14 TVU CL screening in this population, in particular for nulliparous women, has come under interrogation. The authors found only an 8% sensitivity of TVU CL screening for SPTB using a cutoff of ≤25 mm at 16 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks of gestation in 9,410 nulliparous women. This result is different compared with other previous cohort studies in this area, however, and is likely related to a number of issues in the methodology.

First, TVU CL screening was done in many women at too early a gestational age. The earlier the CL screening, the lower the sensitivity of the procedure. Data at 16 and 17 weeks of gestation should have been excluded, as almost all RCTs and other studies on universal TVU CL screening in this population recommended doing screening at about 18 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks.

Second, women with TVU CL <15 mm received vaginal progesterone. This would decrease the incidence of PTB and, therefore, sensitivity.

Third, outcomes data were not available for 469 women and, compared with women analyzed, these women were at higher risk for SPTB as they were more likely to be aged 21 years or younger, black, with less than a high school education, and single, all significant risk factors for SPTB. (Not all risk factors for SPTB were reported in this study.)

Fourth, pregnancy losses before 20 weeks were excluded, and these could have been early SPTB; therefore, the sensitivity could have been decreased if women with this outcome were excluded.

Fifth, prior studies have shown that TVU CL screening in singletons without prior SPTB has a sensitivity of about 30% to 40%.15,16 In nulliparas, the sensitivity of TVU CL ≤20 mm had been reported previously to be 20%.16 Additional data from 2012–2014 at our institution demonstrate that the incidence of CL ≤25 mm is about 2.8% in nulliparous women, with a sensitivity of 19.5% for SPTB <37 weeks. These numbers show again that 8% sensitivity was low in the JAMA study14 due the shortcomings we just highlighted. Furthermore, the reported sensitivity of TVU CL ≤25 mm for PTB <32 weeks was 24% in Esplin and colleagues’ study,14 while 60% in our data. Given that early preterm births are the most significant source of neonatal morbidity and mortality, women with a singleton gestation and no prior SPTB but with a short TVU CL are perhaps the most important subgroup to identify.

Sixth, a low sensitivity in and of itself is not reflective of a poor screening test. We have known for a long time that SPTB has many etiologies. No one screening test, and no one intervention, would independently prevent all SPTBs. In a population that accounts for more than half of PTBs and for whom no other screening test has been found to be effective, much less cost effective, it is important not to cast aside the dramatic potential clinical benefit to TVU CL screening.

Related Article:

A stepwise approach to cervical cerclage

Singletons with a prior SPTB

This is the first population in which TVU CL screening was first proven beneficial for prevention of SPTB. These women all should receive progesterone starting at 16 weeks because of the prior SPTB. In these women, TVU CL screening should be initiated at 16 weeks, and repeated every 2 weeks (weekly if TVU CL is found to be 25 mm to 29 mm) until 23 6/7 weeks. If the TVU CL is identified to be <25 mm before 24 weeks, cerclage should be recommended.1,2,17

Twins

Twins are the most recent population in which an intervention based on TVU CL screening has been shown to be beneficial. Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant decrease in SPTB as well as in some neonatal outcomes in twin gestations found to have a TVU CL <25 mm in the midtrimester in a meta-analysis of RCTs.18 Based on these results, we at our institution recently have started offering TVU CL screening at the time of the anatomy scan (about 20 weeks) to twin gestations.

Related Article:

Which perioperative strategies for transvaginal cervical cerclage are backed by data?

Bottom line

In summary, universal second trimester TVU CL screening of both singletons and twin gestations should be considered seriously by obstetric practitioners to successfully decrease the grave burden of SPTB.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Berghella V. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: Translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376-386.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 130: Prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964-973.

- Werner EF, Hamel MS, Orzechowski K, Berghella V, Thung SF. Cost-effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening in singletons without a prior preterm birth: an update. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):554.e1-e6.

- Einerson BD, Grobman WA, Miller ES. Cost-effectiveness of risk-based screening for cervical length to prevent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):100.e1-e7.

- McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T; Society for Maternal-Fetal medicine. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):B2-B7.

- Khalifeh A, Quist-Nelson J. Current implementation of universal cervical length screening for preterm birth prevention in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(suppl 1):7S.

- Mella MT, Mackeen AD, Gache D, Baxter JK, Berghella V. The utility of screening for historical risk factors for preterm birth in women with known second trimester cervical length. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(7):710-715.

- Saccone G, Perriera L, Berghella V. Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):572-591.

- Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: A systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):124.e1-e19.

- Romero R, Nicolaides KH, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth ≤34 weeks of gestation in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis including data from the OPPTIMUM study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):308-317.

- Orzechoski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520-525.

- Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid-trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):365.e1-e5.

- Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG, et al. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):523.e1-e8.

- Esplin MS, Elovitz MA, Iams JD, et al; njMoM2b Network. Predictive accuracy of serial ttransvaginal cervical lengths and quantitative vaginal fetal fibronectin levels for spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1047-1056.

- Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567-572.

- Orzechowski KM, Boelig R, Nicholas SS, Baxter J, Berghella V. Is universal cervical length screening indicated in women with prior term birth? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):234.e1-e5.

- Preterm labour and birth. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25?unlid=9291036072016213201257. Published November 2015. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, El-Refaie W, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(3):303-314.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) cervical length (CL) screening for prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) is among the most transformative clinical changes in obstetrics in the last decades. TVU CL screening should now be offered to all pregnant women: hence the appellative ‘universal CL screening.’

TVU CL screening is an excellent screening test for several reasons. It screens for SPTB, which is a clinically important, well-defined disease whose prevalence and natural history is known, and has an early recognizable asymptomatic phase in CL shortening detected by TVU. TVU CL screening is a well-described technique, safe and acceptable, with a reasonable cutoff (25 mm) now identified for all populations, and results are reproducible and accurate. There are hundreds of studies proving these facts. In the last 10 years, TVU measurement of CL as a screening test has been accepted1,2: it identifies women at risk for SPTB, and an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation) is effective in preventing SPTB. Screening and treatment of short cervix is cost-effective and readily available as an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation), is effective in preventing the outcome (SPTB), treating abnormal results is cost-effective, and facilities for screening are available and treatments are readily available.3–5 It is also important to emphasize that CL screening for prevention of SPTB should be done by TVU, and not by transabdominal ultrasound.6It is best to review TVU CL screening by populations: singletons without prior SPTB, singletons with prior SPTB, and twins (Table).

Related Article:

Can transabdominal ultrasound exclude short cervix?

Singletons without prior SPTB

Women with no previous SPTB who are carrying a singleton pregnancy is the population in which TVU CL could have the greatest impact on decreasing SPTB, for several reasons:

- Up to 60% to 90% of SPTB occur in this population.

- More than 90% of these women have risk factors for SPTB.7,8

- Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant 39% decrease in PTB at <33 weeks of gestation and a significant 38% decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 606 women without prior PTB.9,10

- Cost-effectiveness studies have shown that TVU CL screening in this specific population prevents thousands of preterm births, saves or improves from death or major morbidity 350 babies’ lives annually, and saves approximately $320,000 per year in the US alone.3 These numbers may be even higher now as the TVU CL cutoff for offering vaginal progesterone has moved in many centers from ≤20 mm to ≤25 mm, including more women (from about 0.8% to about 2% to 3%, respectively11) who benefit from screening.

- Real-world implementation studies have indeed shown significant decreases in SPTB when a policy of universal TVU CL screening in this specific population is implemented.12,13

Universal TVU CL screening recently called into question

In a recent article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association,14 TVU CL screening in this population, in particular for nulliparous women, has come under interrogation. The authors found only an 8% sensitivity of TVU CL screening for SPTB using a cutoff of ≤25 mm at 16 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks of gestation in 9,410 nulliparous women. This result is different compared with other previous cohort studies in this area, however, and is likely related to a number of issues in the methodology.

First, TVU CL screening was done in many women at too early a gestational age. The earlier the CL screening, the lower the sensitivity of the procedure. Data at 16 and 17 weeks of gestation should have been excluded, as almost all RCTs and other studies on universal TVU CL screening in this population recommended doing screening at about 18 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks.

Second, women with TVU CL <15 mm received vaginal progesterone. This would decrease the incidence of PTB and, therefore, sensitivity.

Third, outcomes data were not available for 469 women and, compared with women analyzed, these women were at higher risk for SPTB as they were more likely to be aged 21 years or younger, black, with less than a high school education, and single, all significant risk factors for SPTB. (Not all risk factors for SPTB were reported in this study.)

Fourth, pregnancy losses before 20 weeks were excluded, and these could have been early SPTB; therefore, the sensitivity could have been decreased if women with this outcome were excluded.

Fifth, prior studies have shown that TVU CL screening in singletons without prior SPTB has a sensitivity of about 30% to 40%.15,16 In nulliparas, the sensitivity of TVU CL ≤20 mm had been reported previously to be 20%.16 Additional data from 2012–2014 at our institution demonstrate that the incidence of CL ≤25 mm is about 2.8% in nulliparous women, with a sensitivity of 19.5% for SPTB <37 weeks. These numbers show again that 8% sensitivity was low in the JAMA study14 due the shortcomings we just highlighted. Furthermore, the reported sensitivity of TVU CL ≤25 mm for PTB <32 weeks was 24% in Esplin and colleagues’ study,14 while 60% in our data. Given that early preterm births are the most significant source of neonatal morbidity and mortality, women with a singleton gestation and no prior SPTB but with a short TVU CL are perhaps the most important subgroup to identify.

Sixth, a low sensitivity in and of itself is not reflective of a poor screening test. We have known for a long time that SPTB has many etiologies. No one screening test, and no one intervention, would independently prevent all SPTBs. In a population that accounts for more than half of PTBs and for whom no other screening test has been found to be effective, much less cost effective, it is important not to cast aside the dramatic potential clinical benefit to TVU CL screening.

Related Article:

A stepwise approach to cervical cerclage

Singletons with a prior SPTB

This is the first population in which TVU CL screening was first proven beneficial for prevention of SPTB. These women all should receive progesterone starting at 16 weeks because of the prior SPTB. In these women, TVU CL screening should be initiated at 16 weeks, and repeated every 2 weeks (weekly if TVU CL is found to be 25 mm to 29 mm) until 23 6/7 weeks. If the TVU CL is identified to be <25 mm before 24 weeks, cerclage should be recommended.1,2,17

Twins

Twins are the most recent population in which an intervention based on TVU CL screening has been shown to be beneficial. Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant decrease in SPTB as well as in some neonatal outcomes in twin gestations found to have a TVU CL <25 mm in the midtrimester in a meta-analysis of RCTs.18 Based on these results, we at our institution recently have started offering TVU CL screening at the time of the anatomy scan (about 20 weeks) to twin gestations.

Related Article:

Which perioperative strategies for transvaginal cervical cerclage are backed by data?

Bottom line

In summary, universal second trimester TVU CL screening of both singletons and twin gestations should be considered seriously by obstetric practitioners to successfully decrease the grave burden of SPTB.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) cervical length (CL) screening for prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) is among the most transformative clinical changes in obstetrics in the last decades. TVU CL screening should now be offered to all pregnant women: hence the appellative ‘universal CL screening.’

TVU CL screening is an excellent screening test for several reasons. It screens for SPTB, which is a clinically important, well-defined disease whose prevalence and natural history is known, and has an early recognizable asymptomatic phase in CL shortening detected by TVU. TVU CL screening is a well-described technique, safe and acceptable, with a reasonable cutoff (25 mm) now identified for all populations, and results are reproducible and accurate. There are hundreds of studies proving these facts. In the last 10 years, TVU measurement of CL as a screening test has been accepted1,2: it identifies women at risk for SPTB, and an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation) is effective in preventing SPTB. Screening and treatment of short cervix is cost-effective and readily available as an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation), is effective in preventing the outcome (SPTB), treating abnormal results is cost-effective, and facilities for screening are available and treatments are readily available.3–5 It is also important to emphasize that CL screening for prevention of SPTB should be done by TVU, and not by transabdominal ultrasound.6It is best to review TVU CL screening by populations: singletons without prior SPTB, singletons with prior SPTB, and twins (Table).

Related Article:

Can transabdominal ultrasound exclude short cervix?

Singletons without prior SPTB

Women with no previous SPTB who are carrying a singleton pregnancy is the population in which TVU CL could have the greatest impact on decreasing SPTB, for several reasons:

- Up to 60% to 90% of SPTB occur in this population.

- More than 90% of these women have risk factors for SPTB.7,8

- Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant 39% decrease in PTB at <33 weeks of gestation and a significant 38% decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 606 women without prior PTB.9,10

- Cost-effectiveness studies have shown that TVU CL screening in this specific population prevents thousands of preterm births, saves or improves from death or major morbidity 350 babies’ lives annually, and saves approximately $320,000 per year in the US alone.3 These numbers may be even higher now as the TVU CL cutoff for offering vaginal progesterone has moved in many centers from ≤20 mm to ≤25 mm, including more women (from about 0.8% to about 2% to 3%, respectively11) who benefit from screening.

- Real-world implementation studies have indeed shown significant decreases in SPTB when a policy of universal TVU CL screening in this specific population is implemented.12,13

Universal TVU CL screening recently called into question

In a recent article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association,14 TVU CL screening in this population, in particular for nulliparous women, has come under interrogation. The authors found only an 8% sensitivity of TVU CL screening for SPTB using a cutoff of ≤25 mm at 16 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks of gestation in 9,410 nulliparous women. This result is different compared with other previous cohort studies in this area, however, and is likely related to a number of issues in the methodology.

First, TVU CL screening was done in many women at too early a gestational age. The earlier the CL screening, the lower the sensitivity of the procedure. Data at 16 and 17 weeks of gestation should have been excluded, as almost all RCTs and other studies on universal TVU CL screening in this population recommended doing screening at about 18 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks.

Second, women with TVU CL <15 mm received vaginal progesterone. This would decrease the incidence of PTB and, therefore, sensitivity.

Third, outcomes data were not available for 469 women and, compared with women analyzed, these women were at higher risk for SPTB as they were more likely to be aged 21 years or younger, black, with less than a high school education, and single, all significant risk factors for SPTB. (Not all risk factors for SPTB were reported in this study.)

Fourth, pregnancy losses before 20 weeks were excluded, and these could have been early SPTB; therefore, the sensitivity could have been decreased if women with this outcome were excluded.

Fifth, prior studies have shown that TVU CL screening in singletons without prior SPTB has a sensitivity of about 30% to 40%.15,16 In nulliparas, the sensitivity of TVU CL ≤20 mm had been reported previously to be 20%.16 Additional data from 2012–2014 at our institution demonstrate that the incidence of CL ≤25 mm is about 2.8% in nulliparous women, with a sensitivity of 19.5% for SPTB <37 weeks. These numbers show again that 8% sensitivity was low in the JAMA study14 due the shortcomings we just highlighted. Furthermore, the reported sensitivity of TVU CL ≤25 mm for PTB <32 weeks was 24% in Esplin and colleagues’ study,14 while 60% in our data. Given that early preterm births are the most significant source of neonatal morbidity and mortality, women with a singleton gestation and no prior SPTB but with a short TVU CL are perhaps the most important subgroup to identify.

Sixth, a low sensitivity in and of itself is not reflective of a poor screening test. We have known for a long time that SPTB has many etiologies. No one screening test, and no one intervention, would independently prevent all SPTBs. In a population that accounts for more than half of PTBs and for whom no other screening test has been found to be effective, much less cost effective, it is important not to cast aside the dramatic potential clinical benefit to TVU CL screening.

Related Article:

A stepwise approach to cervical cerclage

Singletons with a prior SPTB

This is the first population in which TVU CL screening was first proven beneficial for prevention of SPTB. These women all should receive progesterone starting at 16 weeks because of the prior SPTB. In these women, TVU CL screening should be initiated at 16 weeks, and repeated every 2 weeks (weekly if TVU CL is found to be 25 mm to 29 mm) until 23 6/7 weeks. If the TVU CL is identified to be <25 mm before 24 weeks, cerclage should be recommended.1,2,17

Twins

Twins are the most recent population in which an intervention based on TVU CL screening has been shown to be beneficial. Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant decrease in SPTB as well as in some neonatal outcomes in twin gestations found to have a TVU CL <25 mm in the midtrimester in a meta-analysis of RCTs.18 Based on these results, we at our institution recently have started offering TVU CL screening at the time of the anatomy scan (about 20 weeks) to twin gestations.

Related Article:

Which perioperative strategies for transvaginal cervical cerclage are backed by data?

Bottom line

In summary, universal second trimester TVU CL screening of both singletons and twin gestations should be considered seriously by obstetric practitioners to successfully decrease the grave burden of SPTB.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Berghella V. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: Translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376-386.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 130: Prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964-973.

- Werner EF, Hamel MS, Orzechowski K, Berghella V, Thung SF. Cost-effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening in singletons without a prior preterm birth: an update. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):554.e1-e6.

- Einerson BD, Grobman WA, Miller ES. Cost-effectiveness of risk-based screening for cervical length to prevent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):100.e1-e7.

- McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T; Society for Maternal-Fetal medicine. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):B2-B7.

- Khalifeh A, Quist-Nelson J. Current implementation of universal cervical length screening for preterm birth prevention in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(suppl 1):7S.

- Mella MT, Mackeen AD, Gache D, Baxter JK, Berghella V. The utility of screening for historical risk factors for preterm birth in women with known second trimester cervical length. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(7):710-715.

- Saccone G, Perriera L, Berghella V. Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):572-591.

- Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: A systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):124.e1-e19.

- Romero R, Nicolaides KH, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth ≤34 weeks of gestation in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis including data from the OPPTIMUM study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):308-317.

- Orzechoski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520-525.

- Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid-trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):365.e1-e5.

- Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG, et al. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):523.e1-e8.

- Esplin MS, Elovitz MA, Iams JD, et al; njMoM2b Network. Predictive accuracy of serial ttransvaginal cervical lengths and quantitative vaginal fetal fibronectin levels for spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1047-1056.

- Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567-572.

- Orzechowski KM, Boelig R, Nicholas SS, Baxter J, Berghella V. Is universal cervical length screening indicated in women with prior term birth? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):234.e1-e5.

- Preterm labour and birth. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25?unlid=9291036072016213201257. Published November 2015. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, El-Refaie W, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(3):303-314.

- Berghella V. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: Translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376-386.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 130: Prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964-973.

- Werner EF, Hamel MS, Orzechowski K, Berghella V, Thung SF. Cost-effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening in singletons without a prior preterm birth: an update. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):554.e1-e6.

- Einerson BD, Grobman WA, Miller ES. Cost-effectiveness of risk-based screening for cervical length to prevent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):100.e1-e7.

- McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T; Society for Maternal-Fetal medicine. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):B2-B7.

- Khalifeh A, Quist-Nelson J. Current implementation of universal cervical length screening for preterm birth prevention in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(suppl 1):7S.

- Mella MT, Mackeen AD, Gache D, Baxter JK, Berghella V. The utility of screening for historical risk factors for preterm birth in women with known second trimester cervical length. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(7):710-715.

- Saccone G, Perriera L, Berghella V. Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):572-591.

- Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: A systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):124.e1-e19.

- Romero R, Nicolaides KH, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth ≤34 weeks of gestation in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis including data from the OPPTIMUM study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):308-317.

- Orzechoski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520-525.

- Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid-trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):365.e1-e5.

- Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG, et al. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):523.e1-e8.

- Esplin MS, Elovitz MA, Iams JD, et al; njMoM2b Network. Predictive accuracy of serial ttransvaginal cervical lengths and quantitative vaginal fetal fibronectin levels for spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1047-1056.

- Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567-572.

- Orzechowski KM, Boelig R, Nicholas SS, Baxter J, Berghella V. Is universal cervical length screening indicated in women with prior term birth? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):234.e1-e5.

- Preterm labour and birth. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25?unlid=9291036072016213201257. Published November 2015. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, El-Refaie W, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(3):303-314.

Should recent evidence of improved outcomes for neonates born during the periviable period change our approach to these deliveries?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Pregnancy management when delivery appears to be imminent at 22 to 26 weeks’ gestation—a window defined as the periviable period—is among the most challenging situations that obstetricians face. Expert guidance exists both at a national level in a shared guideline from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine and, ideally, at a local level where teams of obstetricians and neonatologists have considered in their facility what represents best care

Among the most important yet often missing data points are outcomes of neonates born in the periviable period. Surveys suggest that obstetric care providers often underestimate the chance of survival following periviable delivery.2 Understanding and weighing anticipated outcomes inform decision making regarding management and planned obstetric and neonatal interventions, including plans for neonatal resuscitation.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, survival of periviable neonates has been linked clearly to willingness to undertake resuscitation.3 Yet decisions are not and should not be all about survival. Patients and providers want to know about short- and long-term morbidity, especially neurologic health, among survivors. Available collections of morbidity and mortality data, however, often are limited by whether all cases are captured or just those from specialized centers with particular management approaches, which outcomes are included and how they are defined, and the inevitable reality that the outcome of death “competes” with the outcome of neurologic development (that is, those neonates who die are not at risk for later abnormal neurologic outcome).

Given the need for more and better information, the data from a recent study by Younge and colleagues is especially welcome. The investigators reported on survival and neurologic outcome among more than 4,000 births between 22 and 24 weeks’ gestation at 11 centers in the United States.

Details of the study

The authors compared outcomes among three 3-year epochs between 2000 and 2011 and reported that the rate of survival without neurodevelopmental impairment increased over this period while the rate of survival with such impairment did not change. This argues that the observed overall increase in survival over these 12 years was not simply a tradeoff for life with significant impairment.

Within that overall message, however, the details of the data are important. Survival without neurodevelopmental impairment did improve from epoch 1 to epoch 3, but just from 16% to 20% (95% confidence interval [CI], 18–23; P = .001). Most neonates in the 2008–2011 epoch died (64%; 95% CI, 61–66; P<.001) or were severely impaired (16%; 95% CI, 14–18; P = .29). This led the authors to conclude that “despite improvements over time, the incidence of death, neurodevelopmental impairment, and other adverse outcomes remains high.” Examined separately, outcomes for infants born at 22 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation were very limited and unchanged over the 3 epochs studied, with death rates of 97% to 98% and survival without neurodevelopmental impairment of just 1%. In my own practice I do not encourage neonatal resuscitation, cesarean delivery, or many other interventions at less than 23 weeks’ gestation.

By contrast, the study showed that at 24 0/7 to 24 6/7 weeks’ gestation in the 2008–2011 epoch, 55% of neonates survived and, overall, 32% of infants survived without evidence of neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 22 months of age.

Related Article:

Is expectant management a safe alternative to immediate delivery in patients with PPROM close to term?

Study strengths and weaknesses

It is important to note that the definition of neurodevelopmental impairment used in the Younge study included only what many would classify as severe impairment, and survivors in this cohort “without” neurodevelopmental impairment may still have had important neurologic and other health concerns. In addition, the study did not track outcomes of the children at school age or beyond, when other developmental issues may become evident. As well, the study data may not be generalizable, for it included births from just 11 specialized centers, albeit a consortium accounting for 4% to 5% of periviable births in the United States.

Nevertheless, in supporting findings from other US and European analyses, these new data will help inform counseling conversations in the years to come. Such conversations should consider options for resuscitation, palliative care, and, at less than 24 weeks’ gestation, pregnancy termination. In individual cases these and many other decisions will be informed by both specific clinical circumstances—estimated fetal weight, fetal sex, presence of infection, use of antenatal steroids—and, perhaps most important, individual and family values and preferences. Despite these new data, managing periviable gestations will remain a great and important challenge.

--Jeffrey L. Ecker, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Obstetric Care Consensus No. 4: Periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(6):e157-e169.

- Haywood JL, Goldenberg RL, Bronstein J, Nelson KG, Carlo WA. Comparison of perceived and actual rates of survival and freedom from handicap in premature infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(2):432-439.

- Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Unit. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1801-1811.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Pregnancy management when delivery appears to be imminent at 22 to 26 weeks’ gestation—a window defined as the periviable period—is among the most challenging situations that obstetricians face. Expert guidance exists both at a national level in a shared guideline from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine and, ideally, at a local level where teams of obstetricians and neonatologists have considered in their facility what represents best care

Among the most important yet often missing data points are outcomes of neonates born in the periviable period. Surveys suggest that obstetric care providers often underestimate the chance of survival following periviable delivery.2 Understanding and weighing anticipated outcomes inform decision making regarding management and planned obstetric and neonatal interventions, including plans for neonatal resuscitation.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, survival of periviable neonates has been linked clearly to willingness to undertake resuscitation.3 Yet decisions are not and should not be all about survival. Patients and providers want to know about short- and long-term morbidity, especially neurologic health, among survivors. Available collections of morbidity and mortality data, however, often are limited by whether all cases are captured or just those from specialized centers with particular management approaches, which outcomes are included and how they are defined, and the inevitable reality that the outcome of death “competes” with the outcome of neurologic development (that is, those neonates who die are not at risk for later abnormal neurologic outcome).

Given the need for more and better information, the data from a recent study by Younge and colleagues is especially welcome. The investigators reported on survival and neurologic outcome among more than 4,000 births between 22 and 24 weeks’ gestation at 11 centers in the United States.

Details of the study

The authors compared outcomes among three 3-year epochs between 2000 and 2011 and reported that the rate of survival without neurodevelopmental impairment increased over this period while the rate of survival with such impairment did not change. This argues that the observed overall increase in survival over these 12 years was not simply a tradeoff for life with significant impairment.

Within that overall message, however, the details of the data are important. Survival without neurodevelopmental impairment did improve from epoch 1 to epoch 3, but just from 16% to 20% (95% confidence interval [CI], 18–23; P = .001). Most neonates in the 2008–2011 epoch died (64%; 95% CI, 61–66; P<.001) or were severely impaired (16%; 95% CI, 14–18; P = .29). This led the authors to conclude that “despite improvements over time, the incidence of death, neurodevelopmental impairment, and other adverse outcomes remains high.” Examined separately, outcomes for infants born at 22 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation were very limited and unchanged over the 3 epochs studied, with death rates of 97% to 98% and survival without neurodevelopmental impairment of just 1%. In my own practice I do not encourage neonatal resuscitation, cesarean delivery, or many other interventions at less than 23 weeks’ gestation.

By contrast, the study showed that at 24 0/7 to 24 6/7 weeks’ gestation in the 2008–2011 epoch, 55% of neonates survived and, overall, 32% of infants survived without evidence of neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 22 months of age.

Related Article:

Is expectant management a safe alternative to immediate delivery in patients with PPROM close to term?

Study strengths and weaknesses

It is important to note that the definition of neurodevelopmental impairment used in the Younge study included only what many would classify as severe impairment, and survivors in this cohort “without” neurodevelopmental impairment may still have had important neurologic and other health concerns. In addition, the study did not track outcomes of the children at school age or beyond, when other developmental issues may become evident. As well, the study data may not be generalizable, for it included births from just 11 specialized centers, albeit a consortium accounting for 4% to 5% of periviable births in the United States.

Nevertheless, in supporting findings from other US and European analyses, these new data will help inform counseling conversations in the years to come. Such conversations should consider options for resuscitation, palliative care, and, at less than 24 weeks’ gestation, pregnancy termination. In individual cases these and many other decisions will be informed by both specific clinical circumstances—estimated fetal weight, fetal sex, presence of infection, use of antenatal steroids—and, perhaps most important, individual and family values and preferences. Despite these new data, managing periviable gestations will remain a great and important challenge.

--Jeffrey L. Ecker, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Pregnancy management when delivery appears to be imminent at 22 to 26 weeks’ gestation—a window defined as the periviable period—is among the most challenging situations that obstetricians face. Expert guidance exists both at a national level in a shared guideline from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine and, ideally, at a local level where teams of obstetricians and neonatologists have considered in their facility what represents best care

Among the most important yet often missing data points are outcomes of neonates born in the periviable period. Surveys suggest that obstetric care providers often underestimate the chance of survival following periviable delivery.2 Understanding and weighing anticipated outcomes inform decision making regarding management and planned obstetric and neonatal interventions, including plans for neonatal resuscitation.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, survival of periviable neonates has been linked clearly to willingness to undertake resuscitation.3 Yet decisions are not and should not be all about survival. Patients and providers want to know about short- and long-term morbidity, especially neurologic health, among survivors. Available collections of morbidity and mortality data, however, often are limited by whether all cases are captured or just those from specialized centers with particular management approaches, which outcomes are included and how they are defined, and the inevitable reality that the outcome of death “competes” with the outcome of neurologic development (that is, those neonates who die are not at risk for later abnormal neurologic outcome).

Given the need for more and better information, the data from a recent study by Younge and colleagues is especially welcome. The investigators reported on survival and neurologic outcome among more than 4,000 births between 22 and 24 weeks’ gestation at 11 centers in the United States.

Details of the study

The authors compared outcomes among three 3-year epochs between 2000 and 2011 and reported that the rate of survival without neurodevelopmental impairment increased over this period while the rate of survival with such impairment did not change. This argues that the observed overall increase in survival over these 12 years was not simply a tradeoff for life with significant impairment.

Within that overall message, however, the details of the data are important. Survival without neurodevelopmental impairment did improve from epoch 1 to epoch 3, but just from 16% to 20% (95% confidence interval [CI], 18–23; P = .001). Most neonates in the 2008–2011 epoch died (64%; 95% CI, 61–66; P<.001) or were severely impaired (16%; 95% CI, 14–18; P = .29). This led the authors to conclude that “despite improvements over time, the incidence of death, neurodevelopmental impairment, and other adverse outcomes remains high.” Examined separately, outcomes for infants born at 22 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation were very limited and unchanged over the 3 epochs studied, with death rates of 97% to 98% and survival without neurodevelopmental impairment of just 1%. In my own practice I do not encourage neonatal resuscitation, cesarean delivery, or many other interventions at less than 23 weeks’ gestation.

By contrast, the study showed that at 24 0/7 to 24 6/7 weeks’ gestation in the 2008–2011 epoch, 55% of neonates survived and, overall, 32% of infants survived without evidence of neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 22 months of age.

Related Article:

Is expectant management a safe alternative to immediate delivery in patients with PPROM close to term?

Study strengths and weaknesses

It is important to note that the definition of neurodevelopmental impairment used in the Younge study included only what many would classify as severe impairment, and survivors in this cohort “without” neurodevelopmental impairment may still have had important neurologic and other health concerns. In addition, the study did not track outcomes of the children at school age or beyond, when other developmental issues may become evident. As well, the study data may not be generalizable, for it included births from just 11 specialized centers, albeit a consortium accounting for 4% to 5% of periviable births in the United States.

Nevertheless, in supporting findings from other US and European analyses, these new data will help inform counseling conversations in the years to come. Such conversations should consider options for resuscitation, palliative care, and, at less than 24 weeks’ gestation, pregnancy termination. In individual cases these and many other decisions will be informed by both specific clinical circumstances—estimated fetal weight, fetal sex, presence of infection, use of antenatal steroids—and, perhaps most important, individual and family values and preferences. Despite these new data, managing periviable gestations will remain a great and important challenge.

--Jeffrey L. Ecker, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Obstetric Care Consensus No. 4: Periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(6):e157-e169.

- Haywood JL, Goldenberg RL, Bronstein J, Nelson KG, Carlo WA. Comparison of perceived and actual rates of survival and freedom from handicap in premature infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(2):432-439.

- Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Unit. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1801-1811.

- Obstetric Care Consensus No. 4: Periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(6):e157-e169.

- Haywood JL, Goldenberg RL, Bronstein J, Nelson KG, Carlo WA. Comparison of perceived and actual rates of survival and freedom from handicap in premature infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(2):432-439.

- Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Unit. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1801-1811.

Bacterial vaginosis: Meet patients' needs with effective diagnosis and treatment

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Which treatments for pelvic floor disorders are backed by evidence?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Care of women with pelvic floor disorders, primarily urinary incontinence and POP, involves:

- assessing the patient’s symptoms and determining how bothersome they are

- educating the patient about her condition and the options for treatment

- initiating treatment with the most conservative and least invasive therapies.

Safe treatments include PFMT and pessaries, and both can be effective. However, since approximately 25% of women experience one or more pelvic floor disorders during their life, surgical repair of these disorders is common. The lifetime risk of surgery for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) or POP is 20%,1 and one-third of patients will undergo reoperation for the same condition. Midurethral mesh slings are the gold standard for surgical management of SUI.2 Use of transvaginal mesh for primary prolapse repairs, however, is associated with challenging adverse effects, and its use should be reserved for carefully selected patients.

Data from 3 recent studies contribute to our evidence base on various treatments for pelvic floor disorders.

Details of the studies

PFMT for secondary prevention of POP. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, Hagen and colleagues randomly assigned 414 women with POP, with or without symptoms, to an intervention group or a control group. The women had previously participated in a longitudinal study of postpartum pelvic floor function. Participants in the intervention group (n = 207) received 5 formal sessions of PFMT over 16 weeks, followed by Pilates-based classes focused on pelvic floor exercises; those in the control group (n = 207) received an informational leaflet about prolapse and lifestyle. The primary outcome was self-reported prolapse symptoms, assessed with the POP Symptom Score (POP-SS) at 2 years.

At study end, the mean (SD) POP-SS score in the intervention group was 3.2 (3.4), compared with a mean (SD) score of 4.2 (4.4) in the control group (adjusted mean difference, −1.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.70 to −0.33; P = .004).

Investigators’ interpretation. The researchers concluded that the participants in the PFMT group had a small but significant—and clinically important—decrease in prolapse symptoms.

The PROSPECT study: Standard versus augmented surgical repair. In a multicenter trial in the United Kingdom by Glazener and associates, 1,352 women with symptomatic POP were randomly allocated to surgical repair with native tissue alone (standard repair) or to standard surgical repair augmented either with polypropylene mesh or with biological graft. The primary outcomes were participant-reported prolapse symptoms (assessed with POP-SS) and prolapse-related quality of life scores; these were measured at 1 year and at 2 years.

One year after surgery, failure rates (defined as prolapse beyond the hymen) were similar in all groups (range, 14%–18%); serious adverse events were also similar in all surgical groups (range, 6%–10%). Overall, 6% of women underwent reoperation for recurrent symptoms. Among women randomly assigned to repair with mesh, 12% to 14% experienced mesh-related adverse events; three-quarters of these women ultimately required surgical excision of the mesh.

Study takeaway. Thus, in terms of effectiveness, quality of life, and adverse effects, augmentation of a vaginal surgical repair with either mesh or graft material did not improve the outcomes of women with POP.

Adverse events after surgical procedures for pelvic floor disorders. In Scotland, Morling and colleagues performed a retrospective observational cohort study of first-time surgeries for SUI (mesh or colposuspension; 16,660 procedures) and prolapse (mesh or native tissue; 18,986 procedures).

After 5 years of follow-up, women who underwent midurethral mesh sling placement or colposuspension had similar rates of repeat surgery for recurrent SUI (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.73–1.11). Use of mesh slings was associated with fewer immediate complications (adjusted relative risk, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.36–0.55) compared with nonmesh surgery.

Among women who underwent surgery for prolapse, those who had anterior and posterior repair with mesh experienced higher late complication rates than those who underwent native tissue repair. Risk for subsequent prolapse repair was similar with mesh and native-tissue procedures.

Authors’ commentary. The researchers noted that their data support the use of mesh procedures for incontinence but additional research on longer-term outcomes would be useful. However, for prolapse repair, the study results do not decidedly favor any one vault repair procedure.

--Meadow M. Good, DO

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Funk MJ. Lifetime risk of stress incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201–1206.

- Nager C, Tulikangas P, Miller D, Rovner E, Goldman H. Position statement on mesh midurethral slings for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(3):123–125.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Care of women with pelvic floor disorders, primarily urinary incontinence and POP, involves:

- assessing the patient’s symptoms and determining how bothersome they are

- educating the patient about her condition and the options for treatment

- initiating treatment with the most conservative and least invasive therapies.

Safe treatments include PFMT and pessaries, and both can be effective. However, since approximately 25% of women experience one or more pelvic floor disorders during their life, surgical repair of these disorders is common. The lifetime risk of surgery for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) or POP is 20%,1 and one-third of patients will undergo reoperation for the same condition. Midurethral mesh slings are the gold standard for surgical management of SUI.2 Use of transvaginal mesh for primary prolapse repairs, however, is associated with challenging adverse effects, and its use should be reserved for carefully selected patients.

Data from 3 recent studies contribute to our evidence base on various treatments for pelvic floor disorders.

Details of the studies

PFMT for secondary prevention of POP. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, Hagen and colleagues randomly assigned 414 women with POP, with or without symptoms, to an intervention group or a control group. The women had previously participated in a longitudinal study of postpartum pelvic floor function. Participants in the intervention group (n = 207) received 5 formal sessions of PFMT over 16 weeks, followed by Pilates-based classes focused on pelvic floor exercises; those in the control group (n = 207) received an informational leaflet about prolapse and lifestyle. The primary outcome was self-reported prolapse symptoms, assessed with the POP Symptom Score (POP-SS) at 2 years.

At study end, the mean (SD) POP-SS score in the intervention group was 3.2 (3.4), compared with a mean (SD) score of 4.2 (4.4) in the control group (adjusted mean difference, −1.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.70 to −0.33; P = .004).

Investigators’ interpretation. The researchers concluded that the participants in the PFMT group had a small but significant—and clinically important—decrease in prolapse symptoms.

The PROSPECT study: Standard versus augmented surgical repair. In a multicenter trial in the United Kingdom by Glazener and associates, 1,352 women with symptomatic POP were randomly allocated to surgical repair with native tissue alone (standard repair) or to standard surgical repair augmented either with polypropylene mesh or with biological graft. The primary outcomes were participant-reported prolapse symptoms (assessed with POP-SS) and prolapse-related quality of life scores; these were measured at 1 year and at 2 years.

One year after surgery, failure rates (defined as prolapse beyond the hymen) were similar in all groups (range, 14%–18%); serious adverse events were also similar in all surgical groups (range, 6%–10%). Overall, 6% of women underwent reoperation for recurrent symptoms. Among women randomly assigned to repair with mesh, 12% to 14% experienced mesh-related adverse events; three-quarters of these women ultimately required surgical excision of the mesh.

Study takeaway. Thus, in terms of effectiveness, quality of life, and adverse effects, augmentation of a vaginal surgical repair with either mesh or graft material did not improve the outcomes of women with POP.

Adverse events after surgical procedures for pelvic floor disorders. In Scotland, Morling and colleagues performed a retrospective observational cohort study of first-time surgeries for SUI (mesh or colposuspension; 16,660 procedures) and prolapse (mesh or native tissue; 18,986 procedures).

After 5 years of follow-up, women who underwent midurethral mesh sling placement or colposuspension had similar rates of repeat surgery for recurrent SUI (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.73–1.11). Use of mesh slings was associated with fewer immediate complications (adjusted relative risk, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.36–0.55) compared with nonmesh surgery.

Among women who underwent surgery for prolapse, those who had anterior and posterior repair with mesh experienced higher late complication rates than those who underwent native tissue repair. Risk for subsequent prolapse repair was similar with mesh and native-tissue procedures.

Authors’ commentary. The researchers noted that their data support the use of mesh procedures for incontinence but additional research on longer-term outcomes would be useful. However, for prolapse repair, the study results do not decidedly favor any one vault repair procedure.

--Meadow M. Good, DO

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Care of women with pelvic floor disorders, primarily urinary incontinence and POP, involves:

- assessing the patient’s symptoms and determining how bothersome they are

- educating the patient about her condition and the options for treatment

- initiating treatment with the most conservative and least invasive therapies.

Safe treatments include PFMT and pessaries, and both can be effective. However, since approximately 25% of women experience one or more pelvic floor disorders during their life, surgical repair of these disorders is common. The lifetime risk of surgery for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) or POP is 20%,1 and one-third of patients will undergo reoperation for the same condition. Midurethral mesh slings are the gold standard for surgical management of SUI.2 Use of transvaginal mesh for primary prolapse repairs, however, is associated with challenging adverse effects, and its use should be reserved for carefully selected patients.

Data from 3 recent studies contribute to our evidence base on various treatments for pelvic floor disorders.

Details of the studies

PFMT for secondary prevention of POP. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, Hagen and colleagues randomly assigned 414 women with POP, with or without symptoms, to an intervention group or a control group. The women had previously participated in a longitudinal study of postpartum pelvic floor function. Participants in the intervention group (n = 207) received 5 formal sessions of PFMT over 16 weeks, followed by Pilates-based classes focused on pelvic floor exercises; those in the control group (n = 207) received an informational leaflet about prolapse and lifestyle. The primary outcome was self-reported prolapse symptoms, assessed with the POP Symptom Score (POP-SS) at 2 years.

At study end, the mean (SD) POP-SS score in the intervention group was 3.2 (3.4), compared with a mean (SD) score of 4.2 (4.4) in the control group (adjusted mean difference, −1.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.70 to −0.33; P = .004).

Investigators’ interpretation. The researchers concluded that the participants in the PFMT group had a small but significant—and clinically important—decrease in prolapse symptoms.

The PROSPECT study: Standard versus augmented surgical repair. In a multicenter trial in the United Kingdom by Glazener and associates, 1,352 women with symptomatic POP were randomly allocated to surgical repair with native tissue alone (standard repair) or to standard surgical repair augmented either with polypropylene mesh or with biological graft. The primary outcomes were participant-reported prolapse symptoms (assessed with POP-SS) and prolapse-related quality of life scores; these were measured at 1 year and at 2 years.

One year after surgery, failure rates (defined as prolapse beyond the hymen) were similar in all groups (range, 14%–18%); serious adverse events were also similar in all surgical groups (range, 6%–10%). Overall, 6% of women underwent reoperation for recurrent symptoms. Among women randomly assigned to repair with mesh, 12% to 14% experienced mesh-related adverse events; three-quarters of these women ultimately required surgical excision of the mesh.

Study takeaway. Thus, in terms of effectiveness, quality of life, and adverse effects, augmentation of a vaginal surgical repair with either mesh or graft material did not improve the outcomes of women with POP.

Adverse events after surgical procedures for pelvic floor disorders. In Scotland, Morling and colleagues performed a retrospective observational cohort study of first-time surgeries for SUI (mesh or colposuspension; 16,660 procedures) and prolapse (mesh or native tissue; 18,986 procedures).

After 5 years of follow-up, women who underwent midurethral mesh sling placement or colposuspension had similar rates of repeat surgery for recurrent SUI (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.73–1.11). Use of mesh slings was associated with fewer immediate complications (adjusted relative risk, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.36–0.55) compared with nonmesh surgery.

Among women who underwent surgery for prolapse, those who had anterior and posterior repair with mesh experienced higher late complication rates than those who underwent native tissue repair. Risk for subsequent prolapse repair was similar with mesh and native-tissue procedures.

Authors’ commentary. The researchers noted that their data support the use of mesh procedures for incontinence but additional research on longer-term outcomes would be useful. However, for prolapse repair, the study results do not decidedly favor any one vault repair procedure.

--Meadow M. Good, DO

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Funk MJ. Lifetime risk of stress incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201–1206.

- Nager C, Tulikangas P, Miller D, Rovner E, Goldman H. Position statement on mesh midurethral slings for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(3):123–125.

- Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Funk MJ. Lifetime risk of stress incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201–1206.

- Nager C, Tulikangas P, Miller D, Rovner E, Goldman H. Position statement on mesh midurethral slings for stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(3):123–125.

Vulvovaginal disorders: When should you biopsy a suspicious lesion?

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Also from PAGS 2016:

- Dr. Tommaso Falcone offers Top 3 things I learned at the PAGS 2016 symposium

- Visit PAGS

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Also from PAGS 2016:

- Dr. Tommaso Falcone offers Top 3 things I learned at the PAGS 2016 symposium

- Visit PAGS

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Also from PAGS 2016:

- Dr. Tommaso Falcone offers Top 3 things I learned at the PAGS 2016 symposium

- Visit PAGS

It is time for HPV vaccination to be considered part of routine preventive health care

The recognition that human papillomavirus (HPV) oncogenic viruses cause cervical carcinoma remains one of the most game-changing medical discoveries of the last century. Improvements in screening options for detecting cervical cancer precursors followed. We now have the ability to detect high-risk HPV subtypes in routine specimens. Finally, a highly effective vaccine was developed that targets HPV types 16 and 18, which are responsible for causing approximately 70% of all cases of cervical carcinoma.

In one of the original vaccines HPV types 6 and 11, responsible for 90% of all genital warts, were also targeted. In 2014, a 9-valent vaccine incorporating an additional 5 HPV strains (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) was approved and is set to replace all previous vaccine versions. Together, these 7 oncogenic HPV types are responsible for approximately 90% of HPV-related cancers, including cervical, anal, oropharyngeal, vaginal, and vulvar cancer.

By vaccinating boys and girls between ages 9 and 21 (for males) and 9 and 26 (for females), we could effectively eliminate 90% of genital warts and 90% of all HPV-related cancers. So why have we not capitalized on this extraordinary discovery? In 2016, why were only 40% of teenage girls and less than 25% of teenage boys vaccinated against HPV when we are immunizing 80% to 90% of these populations with tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertusis (Tdap) and meningococcal vaccines?

Related article:

2016 Update on cervical disease

Barriers to HPV vaccination

When the first HPV vaccine was approved in 2006, cost was a significant factor. Many health insurance plans did not cover this “discretionary” vaccine, which was viewed as a prevention for sexually transmitted infections rather than as a valuable intervention for the prevention of cervical and other cancers. At well over $125 per dose with 3 doses required for a full series, ObGyns were reluctant to stock and provide these expensive vaccines without assurance of reimbursement. The logistics of recalling patients for their subsequent vaccine doses were challenging for offices that were not accustomed to seeing patients for preventive care activities more than once a year. In addition, the office infrastructure required to maintain the vaccine stock and manage the necessary paperwork could be daunting. Finally, the requirement that patients be observed for 15 to 30 minutes in the office after vaccine administration created efficiency and rooming problems in busy, active practices.

Over time, almost all payers covered the HPV vaccines, but the logistical issues in ObGyn practices remain. Pediatric practices, on the other hand, are ideally suited for vaccine administration. Unfortunately, our colleagues delivering preventive care to young teens have persisted in considering the HPV vaccine as an optional adjunct to routine vaccination despite the advice of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which for many years has recommended the HPV vaccine for girls. In 2011, the ACIP extended the HPV vaccine recommendation to include boys beginning at ages 11 to 12.

New 2-dose HPV vaccine schedule for children <15 years

In October 2016, 10 years after the first HPV vaccine approval, the ACIP and the CDC approved a reduced, 2-dose schedule for those younger than 15.1 The first dose can be administered simultaneously with other recommended vaccines for 11- to 12-year-olds (the meningococcal and Tdap vaccines) and the second dose, 6 or 12 months later.2 The 12-month interval would allow administration, once again, of all required vaccines at the annual visit.

Pivotal immunogenicity study

The new recommendation is based on robust multinational data (52 sites in 15 countries, N = 1,518) from an open-label trial.3 Immunogenicity of 2 doses of the 9-valent HPV vaccine in girls and boys ages 9 to 14 was compared with that of a standard 3-dose regimen in adolescents and young women ages 16 to 26. Five cohorts were studied: boys 9 to 14 given 2 doses at 6-month intervals; girls 9 to 14 given 2 doses at 6-month intervals; boys and girls 9 to 14 given 2 doses at a 12-month interval; girls 9 to 14 given the standard 3-dose regimen; and girls and young women 16 to 26 receiving 3 doses over 6 months.

The authors assessed the antibody responses against each HPV subtype 1 month after the final vaccine dose. Data from 1,377 participants (90.7% of the original cohort) were analyzed. Prespecified antibody titers were set conservatively to ensure adequate immunogenicity. Noninferiority criteria had to be met for all 9 HPV types.

Trial results. The immune responses for the 9- to 14-year-olds were consistently higher than those for the 16- to 26-year-old age group regardless of the regimen—not a surprising finding since the initial trials for HPV vaccine demonstrated a greater response among younger vaccine recipients. In this trial, higher antibody responses were found for the 12-month dosing interval than for the 6-month interval, although both regimens produced an adequate response.

Immunogenicity remained at 6 months. Antibody levels were retested 6 months after the last dose of HPV vaccine in a post hoc analysis. In all groups the antib

Related article:

2015 Update on cervical disease: New ammo for HPV prevention and screening

Simplified dosing may help increase vaccination rates

What does this new dosing regimen mean for practice? It will be simpler to incorporate HPV vaccination routinely into the standard vaccine regimen for preadolescent boys and girls. In addition, counseling for HPV vaccine administration can be combined with counseling for the meningococcal vaccine and routine Tdap booster.

Notably, primary care physicians have reported perceiving HPV vaccine discussions with parents as burdensome, and they tend to discuss it last after conversations about Tdap and meningococcal vaccines.4 Brewer and colleagues5 documented a 5% increase in first HPV vaccine doses among patients in practices in which the providers were taught to “announce” the need for HPV vaccine along with other routine vaccines. There was no increase in HPV vaccine uptake among practices in which providers were taught to “discuss” HPV with parents and to address their concerns, or in control practices. Therefore, less conversation about HPV and the HPV vaccine, as distinct from any other recommended vaccines, is better.

With the new 2-dose regimen, it should be easier to convey that the HPV vaccine is another necessary, routine intervention for children’s health. We should be able to achieve 90% vaccination rates for HPV—similar to rates for Tdap.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC recommends only two HPV shots for younger adolescents. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p1020-hpv-shots.html. Published October 19, 2016. Accessed February 22, 2017.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep MMWR. 2016;65(49)1405–1408.

- Iverson OE, Miranda MJ, Ulied A, et al. Immunogenicity of the 9-valent HPV vaccine using 2-dose regimens in girls and boys vs a 3-dose regimen in women. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2411–2421.

- Gilkey MB, Moss JL, Coyne-Beasley T, Hall ME, Shah PH, Brewer NT. Physician communication about adolescent vaccination: how is human papillomavirus vaccine different? Prev Med. 2015;77:181–185.

The recognition that human papillomavirus (HPV) oncogenic viruses cause cervical carcinoma remains one of the most game-changing medical discoveries of the last century. Improvements in screening options for detecting cervical cancer precursors followed. We now have the ability to detect high-risk HPV subtypes in routine specimens. Finally, a highly effective vaccine was developed that targets HPV types 16 and 18, which are responsible for causing approximately 70% of all cases of cervical carcinoma.

In one of the original vaccines HPV types 6 and 11, responsible for 90% of all genital warts, were also targeted. In 2014, a 9-valent vaccine incorporating an additional 5 HPV strains (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) was approved and is set to replace all previous vaccine versions. Together, these 7 oncogenic HPV types are responsible for approximately 90% of HPV-related cancers, including cervical, anal, oropharyngeal, vaginal, and vulvar cancer.

By vaccinating boys and girls between ages 9 and 21 (for males) and 9 and 26 (for females), we could effectively eliminate 90% of genital warts and 90% of all HPV-related cancers. So why have we not capitalized on this extraordinary discovery? In 2016, why were only 40% of teenage girls and less than 25% of teenage boys vaccinated against HPV when we are immunizing 80% to 90% of these populations with tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertusis (Tdap) and meningococcal vaccines?

Related article:

2016 Update on cervical disease

Barriers to HPV vaccination