User login

Noninvasive prenatal testing: Where we are and where we’re going

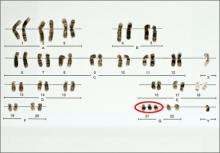

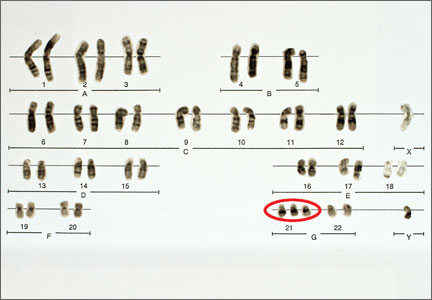

The introduction of amniocentesis in the 1960s brought to prenatal diagnosticians the ability to detect fetal chromosome abnormalities and certain structural defects (including neural tube defects). Since that time, a goal for these practitioners has been the development of effective screening algorithms to better identify women at high risk for detectable fetal abnormalities in concert with the advent of safer and more accessible diagnostic tests, with the eventual aim being the development of a noninvasive prenatal diagnostic test.

Postamniocentesis advancements have included the identification of maternal serum analytes as well as the incorporation of first-trimester ultrasonographic measurements of the fetal nuchal translucency (NT) and nasal bone, all associated with an improved ability to identify women at increased risk for fetal trisomies 21 and 18 as well as some other fetal abnormalities. In addition, targeted ultrasound has greatly improved the ability to detect fetal structural and growth abnormalities in women of all risk levels, although it remains a highly subjective process with considerable inter/intraoperator and equipment variability.

Related article: NIPT is expanding rapidly--but don't throw out that CVS kit just yet! (Update on Obstetrics; Jaimey M. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD; January 2014)

Noninvasive prenatal screening has the advantages of being noninvasive and carrying no increased risk for fetal loss compared with chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis, which are associated with a small increased risk for pregnancy loss (1/500 to 1/1,500 over baseline risk for loss). However, noninvasive screening is limited compared with diagnostic procedures because it provides only a risk adjustment rather than a definitive diagnostic outcome and is mostly limited to assessment for fetal trisomies 18 and 21.

Targeted ultrasound can identify structural abnormalities associated with other chromosomal, genetic, and genomic abnormalities, but again depends on operator experience, equipment used, maternal habitus, and fetal position. Accordingly, considerable interest has remained in developing a more effective approach for detecting fetal aneuploidy and other fetal abnormalities, including assays that eventually could serve to provide noninvasive prenatal diagnosis.

RECENT ADVANCES BRING US CLOSER TO OUR ULTIMATE GOAL

The recent introduction of circulating cell-free nucleic acids (ccfna) technologies for prenatal screening for common fetal aneuploidies, better known as noninvasive prenatal testing, or NIPT, has presented a far more effective prenatal screening protocol for certain groups of women compared with the aforementioned screening algorithms that rely on measurements of the fetal NT in the late first trimester and maternal serum measurements of analytes in the first and second trimesters.

Currently, four NIPT screening products are available commercially in the United States: MaterniT21 Plus (Sequenom, San Diego, California); Verifi (Illumina, San Diego, California); Harmony Prenatal Test (Ariosa Diagnostics, San Jose, California); and Panorama Prenatal Test (Natera, San Carlos, California). While the technologies and algorithms used by each of the companies differ, they all rely on the premise that 5% to 10% of ccfna in maternal blood are fetal in nature.1 Calculating the ratios of the expected amount of each chromosome-specific nucleic acid to that actually measured in the sample, a prediction of a normal or abnormal complement for that specific chromosome is then made. None of the commercially available tests specifically identify fetal DNA or differentiate fetal from maternal DNA.

Current validation studies have thus far limited the offering of NIPT to women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy, including those:2–6

- of advanced maternal age

- with a positive conventional screening test

- with abnormal ultrasound results suggestive of aneuploidy, or

- who have had a prior pregnancy with a chromosome aneuploidy found in the NIPT panel.

Studies of all available technologies tested on women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy have thus far shown considerably higher sensitivities and specificities and detection rates for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 than conventional screening algorithms, although detection rates for trisomy 13 are slightly lower than those observed for trisomies 21 and 18.

WE STILL HAVE MANY HURDLES TO LEAP

However, the groups of women at high risk for fetal aneuploidy just outlined represent only a small segment of the community of pregnant women. A multicenter study involving 1,914 women published February 2014 in the New England Journal of Medicine7 showed considerably and significantly lower false-positive rates and higher positive predictive values for the detection of trisomies 21 and 18 by NIPT compared with conventional fetal aneuploidy screening. This study incorporated women at low risk for fetal aneuploidies in the study cohort, although women at high risk (based on the stated range of maternal age) also were included in the cohort. Unfortunately, no information was provided in the report about the percentage of low-risk women among the study participants.

Related articles:

Noninvasive prenatal DNA testing: Who is using it, and how? Audiocast, June 2013

Noninvasive prenatal DNA tests are unproven and costly David A. Carpenter, MD (Comment & Controversy; September 2013)

Another concern about the published accuracy of NIPT clinical assays was recently sounded by Menutti and colleagues.8 The authors cited recent cases of positive NIPT outcomes for fetal trisomies 18 and 13 that were not confirmed by diagnostic testing of the pregnancies in question. The authors pondered whether such cases may reflect a limitation of the positive predictive values attributed to NIPT assays and that such limitations may carry profound inaccuracies in determining the accuracy of such protocols for rare aneuploidies.

While the improved detection rates for NIPT compared with conventional screening are not surprising, guidelines published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists still do not recommend the use of NIPT for the screening of low-risk women because of insufficient evaluation of ccfna technologies in the screening of such pregnancies.3 This also applies to twin pregnancies, despite preliminary studies showing comparable detection of trisomies 18 and 21 in such pregnancies compared with singleton pregnancies.3,9

There are no direct comparative studies of the four commercially available screening products, thus precluding a robust comparison and determination of the best existing method to use.

SO, WHERE ARE WE WITH NIPT EXACTLY?

The recent introduction of NIPT into routine obstetric care has left many clinicians with a wide range of questions, many of which cannot be answered because of little or no information, robust or otherwise, to formulate an accurate and cogent response. So let’s state what we know based on the available evidence, recognizing that this will likely change, perhaps considerably, in the weeks and months ahead.

NIPT is a far superior approach, compared with conventional screening approaches, to screening for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 in women carrying singleton pregnancies who are at an increased risk for fetal chromosome abnormalities.

In our current understanding of prenatal screening and diagnosis, NIPT does not provide either the comprehensive approach or the diagnostic accuracy associated with CVS and amniocentesis. As such, NIPT is not a suitable replacement for prenatal diagnostic procedures.

However, its application to screening a low-risk population for the common fetal aneuploidies, as well as in twin pregnancies, has been supported by initial studies, and the inclusion of other clinical outcomes—including other chromosome abnormalities, such as X and Y aneuploidies, trisomy 16, and triploidy10,11 and certain genomic abnormalities (eg, 22q deletions)—in the screening algorithm will expand the future clinical applications of NIPT screening.

DOES NIPT CHANGE OUR CONCEPTS OF SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS?

This question is simple but profound and is perhaps the most important to be asked and addressed. Is a screening algorithm that has a similar sensitivity and specificity to that of CVS and amniocentesis for the most common fetal trisomies in the first and second trimesters sufficient to replace invasive testing for most women? Does the ability to detect fetal genomic abnormalities with microarray analyses of fetal cells obtained by CVS or amniocentesis provide a far greater benefit than that possible with any screening algorithm?

With renewed interest in the cost of health-care screening and diagnosis, we need to consider how comprehensive and accurate our prenatal screening and diagnostic tests should be and whether such improvements are desired or even possible from a clinical or economic viewpoint. In addition, the development of new technologies, such as the capture and analysis of fetal cells in maternal blood, presents the potential for a direct diagnostic fetal assay without the risks of an invasive procedure.

BIAS-FREE COUNSELING CANNOT BE OVERLOOKED

That being said, the current role of NIPT and other screening protocols in obstetric care needs to be clearly communicated to women who are considering their fetal assessment options, with emphasis placed on the capabilities and limitations of prenatal screening (even the newer ccfna-based options), the actual risks associated with invasive testing, and the ability of invasive testing to provide expanded fetal information with the use of microarray analyses.

As it has been from the beginning of prenatal testing in the 1960s, counseling continues to be the most important part of the prenatal screening and diagnostic process and it is needed to facilitate clinical decisions made by women and couples. Counseling must include an accurate communication of the risks, benefits, and limitations of the aforementioned options and issues, and should be provided in a manner that strives to be free of bias, direction, and the personal opinions of the counselor.

In order to provide such counseling, we must remain informed of the ongoing work in the field of prenatal testing, a task that has become more challenging with the rapid release of a considerable amount of new information on prenatal screening technologies over the past 2 years. This will likely continue, and perhaps become even more frenetic, with the expected release of additional information on the clinical applications of ccfna technologies in the near future as well as the development of new technologies applicable for the screening and diagnosis of fetal abnormalities.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.

- Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):485–487.

- Ashoor G, Syngelaki A, Wagner M, Birdir C, Nicolaides KH. Chromosome-selective sequencing of maternal plasma cell–free DNA for first-trimester detection of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(4):322.e1–e5.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. Committee Opinion No. 545: Noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1532–1534.

- Bianchi DW, Platt LD, Goldberg JD, et al; MatErnal Blood IS Source to Accurately diagnose fetal aneuploidy (MELISSA) Study Group. Genome-wide fetal aneuploidy detection by maternal plasma DNA-sequencing. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):890–901.

- Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: An international clinical validation study. Genet Med. 2011;13(11):913–920.

- Palomaki GE, Deciu C, Kloza EM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as Down syndrome: An international collaborative study. Genet Med. 2012;14(3):296–305.

- Bianchi DW, Parker RL, Wentworth J, et al; CARE Study Group. DNA sequencing versus standard prenatal aneuploidy screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):799–808.

- Menutti MT, Cherry AM, Morrissette JJ, Dugoff L. Is it time to sound an alarm about false-positive cell-free DNA testing for fetal aneuploidy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):415−419.

- Canick JA, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to identify Down syndrome and other trisomies in multiple gestations. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(8):730–734.

- Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Gil MM, Quezada MS, Zinevich Y. Prenatal detection of fetal triploidy from cell-free DNA testing in maternal blood [published online ahead of print October 10, 2013]. Fetal Diagn Ther.

- Semango-Sprouse C, Banjevic M, Ryan A, et al. SNP-based non-invasive prenatal testing detects sex chromosome aneuploidies with high accuracy. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(7):643–649.

The introduction of amniocentesis in the 1960s brought to prenatal diagnosticians the ability to detect fetal chromosome abnormalities and certain structural defects (including neural tube defects). Since that time, a goal for these practitioners has been the development of effective screening algorithms to better identify women at high risk for detectable fetal abnormalities in concert with the advent of safer and more accessible diagnostic tests, with the eventual aim being the development of a noninvasive prenatal diagnostic test.

Postamniocentesis advancements have included the identification of maternal serum analytes as well as the incorporation of first-trimester ultrasonographic measurements of the fetal nuchal translucency (NT) and nasal bone, all associated with an improved ability to identify women at increased risk for fetal trisomies 21 and 18 as well as some other fetal abnormalities. In addition, targeted ultrasound has greatly improved the ability to detect fetal structural and growth abnormalities in women of all risk levels, although it remains a highly subjective process with considerable inter/intraoperator and equipment variability.

Related article: NIPT is expanding rapidly--but don't throw out that CVS kit just yet! (Update on Obstetrics; Jaimey M. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD; January 2014)

Noninvasive prenatal screening has the advantages of being noninvasive and carrying no increased risk for fetal loss compared with chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis, which are associated with a small increased risk for pregnancy loss (1/500 to 1/1,500 over baseline risk for loss). However, noninvasive screening is limited compared with diagnostic procedures because it provides only a risk adjustment rather than a definitive diagnostic outcome and is mostly limited to assessment for fetal trisomies 18 and 21.

Targeted ultrasound can identify structural abnormalities associated with other chromosomal, genetic, and genomic abnormalities, but again depends on operator experience, equipment used, maternal habitus, and fetal position. Accordingly, considerable interest has remained in developing a more effective approach for detecting fetal aneuploidy and other fetal abnormalities, including assays that eventually could serve to provide noninvasive prenatal diagnosis.

RECENT ADVANCES BRING US CLOSER TO OUR ULTIMATE GOAL

The recent introduction of circulating cell-free nucleic acids (ccfna) technologies for prenatal screening for common fetal aneuploidies, better known as noninvasive prenatal testing, or NIPT, has presented a far more effective prenatal screening protocol for certain groups of women compared with the aforementioned screening algorithms that rely on measurements of the fetal NT in the late first trimester and maternal serum measurements of analytes in the first and second trimesters.

Currently, four NIPT screening products are available commercially in the United States: MaterniT21 Plus (Sequenom, San Diego, California); Verifi (Illumina, San Diego, California); Harmony Prenatal Test (Ariosa Diagnostics, San Jose, California); and Panorama Prenatal Test (Natera, San Carlos, California). While the technologies and algorithms used by each of the companies differ, they all rely on the premise that 5% to 10% of ccfna in maternal blood are fetal in nature.1 Calculating the ratios of the expected amount of each chromosome-specific nucleic acid to that actually measured in the sample, a prediction of a normal or abnormal complement for that specific chromosome is then made. None of the commercially available tests specifically identify fetal DNA or differentiate fetal from maternal DNA.

Current validation studies have thus far limited the offering of NIPT to women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy, including those:2–6

- of advanced maternal age

- with a positive conventional screening test

- with abnormal ultrasound results suggestive of aneuploidy, or

- who have had a prior pregnancy with a chromosome aneuploidy found in the NIPT panel.

Studies of all available technologies tested on women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy have thus far shown considerably higher sensitivities and specificities and detection rates for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 than conventional screening algorithms, although detection rates for trisomy 13 are slightly lower than those observed for trisomies 21 and 18.

WE STILL HAVE MANY HURDLES TO LEAP

However, the groups of women at high risk for fetal aneuploidy just outlined represent only a small segment of the community of pregnant women. A multicenter study involving 1,914 women published February 2014 in the New England Journal of Medicine7 showed considerably and significantly lower false-positive rates and higher positive predictive values for the detection of trisomies 21 and 18 by NIPT compared with conventional fetal aneuploidy screening. This study incorporated women at low risk for fetal aneuploidies in the study cohort, although women at high risk (based on the stated range of maternal age) also were included in the cohort. Unfortunately, no information was provided in the report about the percentage of low-risk women among the study participants.

Related articles:

Noninvasive prenatal DNA testing: Who is using it, and how? Audiocast, June 2013

Noninvasive prenatal DNA tests are unproven and costly David A. Carpenter, MD (Comment & Controversy; September 2013)

Another concern about the published accuracy of NIPT clinical assays was recently sounded by Menutti and colleagues.8 The authors cited recent cases of positive NIPT outcomes for fetal trisomies 18 and 13 that were not confirmed by diagnostic testing of the pregnancies in question. The authors pondered whether such cases may reflect a limitation of the positive predictive values attributed to NIPT assays and that such limitations may carry profound inaccuracies in determining the accuracy of such protocols for rare aneuploidies.

While the improved detection rates for NIPT compared with conventional screening are not surprising, guidelines published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists still do not recommend the use of NIPT for the screening of low-risk women because of insufficient evaluation of ccfna technologies in the screening of such pregnancies.3 This also applies to twin pregnancies, despite preliminary studies showing comparable detection of trisomies 18 and 21 in such pregnancies compared with singleton pregnancies.3,9

There are no direct comparative studies of the four commercially available screening products, thus precluding a robust comparison and determination of the best existing method to use.

SO, WHERE ARE WE WITH NIPT EXACTLY?

The recent introduction of NIPT into routine obstetric care has left many clinicians with a wide range of questions, many of which cannot be answered because of little or no information, robust or otherwise, to formulate an accurate and cogent response. So let’s state what we know based on the available evidence, recognizing that this will likely change, perhaps considerably, in the weeks and months ahead.

NIPT is a far superior approach, compared with conventional screening approaches, to screening for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 in women carrying singleton pregnancies who are at an increased risk for fetal chromosome abnormalities.

In our current understanding of prenatal screening and diagnosis, NIPT does not provide either the comprehensive approach or the diagnostic accuracy associated with CVS and amniocentesis. As such, NIPT is not a suitable replacement for prenatal diagnostic procedures.

However, its application to screening a low-risk population for the common fetal aneuploidies, as well as in twin pregnancies, has been supported by initial studies, and the inclusion of other clinical outcomes—including other chromosome abnormalities, such as X and Y aneuploidies, trisomy 16, and triploidy10,11 and certain genomic abnormalities (eg, 22q deletions)—in the screening algorithm will expand the future clinical applications of NIPT screening.

DOES NIPT CHANGE OUR CONCEPTS OF SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS?

This question is simple but profound and is perhaps the most important to be asked and addressed. Is a screening algorithm that has a similar sensitivity and specificity to that of CVS and amniocentesis for the most common fetal trisomies in the first and second trimesters sufficient to replace invasive testing for most women? Does the ability to detect fetal genomic abnormalities with microarray analyses of fetal cells obtained by CVS or amniocentesis provide a far greater benefit than that possible with any screening algorithm?

With renewed interest in the cost of health-care screening and diagnosis, we need to consider how comprehensive and accurate our prenatal screening and diagnostic tests should be and whether such improvements are desired or even possible from a clinical or economic viewpoint. In addition, the development of new technologies, such as the capture and analysis of fetal cells in maternal blood, presents the potential for a direct diagnostic fetal assay without the risks of an invasive procedure.

BIAS-FREE COUNSELING CANNOT BE OVERLOOKED

That being said, the current role of NIPT and other screening protocols in obstetric care needs to be clearly communicated to women who are considering their fetal assessment options, with emphasis placed on the capabilities and limitations of prenatal screening (even the newer ccfna-based options), the actual risks associated with invasive testing, and the ability of invasive testing to provide expanded fetal information with the use of microarray analyses.

As it has been from the beginning of prenatal testing in the 1960s, counseling continues to be the most important part of the prenatal screening and diagnostic process and it is needed to facilitate clinical decisions made by women and couples. Counseling must include an accurate communication of the risks, benefits, and limitations of the aforementioned options and issues, and should be provided in a manner that strives to be free of bias, direction, and the personal opinions of the counselor.

In order to provide such counseling, we must remain informed of the ongoing work in the field of prenatal testing, a task that has become more challenging with the rapid release of a considerable amount of new information on prenatal screening technologies over the past 2 years. This will likely continue, and perhaps become even more frenetic, with the expected release of additional information on the clinical applications of ccfna technologies in the near future as well as the development of new technologies applicable for the screening and diagnosis of fetal abnormalities.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.

The introduction of amniocentesis in the 1960s brought to prenatal diagnosticians the ability to detect fetal chromosome abnormalities and certain structural defects (including neural tube defects). Since that time, a goal for these practitioners has been the development of effective screening algorithms to better identify women at high risk for detectable fetal abnormalities in concert with the advent of safer and more accessible diagnostic tests, with the eventual aim being the development of a noninvasive prenatal diagnostic test.

Postamniocentesis advancements have included the identification of maternal serum analytes as well as the incorporation of first-trimester ultrasonographic measurements of the fetal nuchal translucency (NT) and nasal bone, all associated with an improved ability to identify women at increased risk for fetal trisomies 21 and 18 as well as some other fetal abnormalities. In addition, targeted ultrasound has greatly improved the ability to detect fetal structural and growth abnormalities in women of all risk levels, although it remains a highly subjective process with considerable inter/intraoperator and equipment variability.

Related article: NIPT is expanding rapidly--but don't throw out that CVS kit just yet! (Update on Obstetrics; Jaimey M. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD; January 2014)

Noninvasive prenatal screening has the advantages of being noninvasive and carrying no increased risk for fetal loss compared with chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis, which are associated with a small increased risk for pregnancy loss (1/500 to 1/1,500 over baseline risk for loss). However, noninvasive screening is limited compared with diagnostic procedures because it provides only a risk adjustment rather than a definitive diagnostic outcome and is mostly limited to assessment for fetal trisomies 18 and 21.

Targeted ultrasound can identify structural abnormalities associated with other chromosomal, genetic, and genomic abnormalities, but again depends on operator experience, equipment used, maternal habitus, and fetal position. Accordingly, considerable interest has remained in developing a more effective approach for detecting fetal aneuploidy and other fetal abnormalities, including assays that eventually could serve to provide noninvasive prenatal diagnosis.

RECENT ADVANCES BRING US CLOSER TO OUR ULTIMATE GOAL

The recent introduction of circulating cell-free nucleic acids (ccfna) technologies for prenatal screening for common fetal aneuploidies, better known as noninvasive prenatal testing, or NIPT, has presented a far more effective prenatal screening protocol for certain groups of women compared with the aforementioned screening algorithms that rely on measurements of the fetal NT in the late first trimester and maternal serum measurements of analytes in the first and second trimesters.

Currently, four NIPT screening products are available commercially in the United States: MaterniT21 Plus (Sequenom, San Diego, California); Verifi (Illumina, San Diego, California); Harmony Prenatal Test (Ariosa Diagnostics, San Jose, California); and Panorama Prenatal Test (Natera, San Carlos, California). While the technologies and algorithms used by each of the companies differ, they all rely on the premise that 5% to 10% of ccfna in maternal blood are fetal in nature.1 Calculating the ratios of the expected amount of each chromosome-specific nucleic acid to that actually measured in the sample, a prediction of a normal or abnormal complement for that specific chromosome is then made. None of the commercially available tests specifically identify fetal DNA or differentiate fetal from maternal DNA.

Current validation studies have thus far limited the offering of NIPT to women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy, including those:2–6

- of advanced maternal age

- with a positive conventional screening test

- with abnormal ultrasound results suggestive of aneuploidy, or

- who have had a prior pregnancy with a chromosome aneuploidy found in the NIPT panel.

Studies of all available technologies tested on women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy have thus far shown considerably higher sensitivities and specificities and detection rates for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 than conventional screening algorithms, although detection rates for trisomy 13 are slightly lower than those observed for trisomies 21 and 18.

WE STILL HAVE MANY HURDLES TO LEAP

However, the groups of women at high risk for fetal aneuploidy just outlined represent only a small segment of the community of pregnant women. A multicenter study involving 1,914 women published February 2014 in the New England Journal of Medicine7 showed considerably and significantly lower false-positive rates and higher positive predictive values for the detection of trisomies 21 and 18 by NIPT compared with conventional fetal aneuploidy screening. This study incorporated women at low risk for fetal aneuploidies in the study cohort, although women at high risk (based on the stated range of maternal age) also were included in the cohort. Unfortunately, no information was provided in the report about the percentage of low-risk women among the study participants.

Related articles:

Noninvasive prenatal DNA testing: Who is using it, and how? Audiocast, June 2013

Noninvasive prenatal DNA tests are unproven and costly David A. Carpenter, MD (Comment & Controversy; September 2013)

Another concern about the published accuracy of NIPT clinical assays was recently sounded by Menutti and colleagues.8 The authors cited recent cases of positive NIPT outcomes for fetal trisomies 18 and 13 that were not confirmed by diagnostic testing of the pregnancies in question. The authors pondered whether such cases may reflect a limitation of the positive predictive values attributed to NIPT assays and that such limitations may carry profound inaccuracies in determining the accuracy of such protocols for rare aneuploidies.

While the improved detection rates for NIPT compared with conventional screening are not surprising, guidelines published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists still do not recommend the use of NIPT for the screening of low-risk women because of insufficient evaluation of ccfna technologies in the screening of such pregnancies.3 This also applies to twin pregnancies, despite preliminary studies showing comparable detection of trisomies 18 and 21 in such pregnancies compared with singleton pregnancies.3,9

There are no direct comparative studies of the four commercially available screening products, thus precluding a robust comparison and determination of the best existing method to use.

SO, WHERE ARE WE WITH NIPT EXACTLY?

The recent introduction of NIPT into routine obstetric care has left many clinicians with a wide range of questions, many of which cannot be answered because of little or no information, robust or otherwise, to formulate an accurate and cogent response. So let’s state what we know based on the available evidence, recognizing that this will likely change, perhaps considerably, in the weeks and months ahead.

NIPT is a far superior approach, compared with conventional screening approaches, to screening for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 in women carrying singleton pregnancies who are at an increased risk for fetal chromosome abnormalities.

In our current understanding of prenatal screening and diagnosis, NIPT does not provide either the comprehensive approach or the diagnostic accuracy associated with CVS and amniocentesis. As such, NIPT is not a suitable replacement for prenatal diagnostic procedures.

However, its application to screening a low-risk population for the common fetal aneuploidies, as well as in twin pregnancies, has been supported by initial studies, and the inclusion of other clinical outcomes—including other chromosome abnormalities, such as X and Y aneuploidies, trisomy 16, and triploidy10,11 and certain genomic abnormalities (eg, 22q deletions)—in the screening algorithm will expand the future clinical applications of NIPT screening.

DOES NIPT CHANGE OUR CONCEPTS OF SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS?

This question is simple but profound and is perhaps the most important to be asked and addressed. Is a screening algorithm that has a similar sensitivity and specificity to that of CVS and amniocentesis for the most common fetal trisomies in the first and second trimesters sufficient to replace invasive testing for most women? Does the ability to detect fetal genomic abnormalities with microarray analyses of fetal cells obtained by CVS or amniocentesis provide a far greater benefit than that possible with any screening algorithm?

With renewed interest in the cost of health-care screening and diagnosis, we need to consider how comprehensive and accurate our prenatal screening and diagnostic tests should be and whether such improvements are desired or even possible from a clinical or economic viewpoint. In addition, the development of new technologies, such as the capture and analysis of fetal cells in maternal blood, presents the potential for a direct diagnostic fetal assay without the risks of an invasive procedure.

BIAS-FREE COUNSELING CANNOT BE OVERLOOKED

That being said, the current role of NIPT and other screening protocols in obstetric care needs to be clearly communicated to women who are considering their fetal assessment options, with emphasis placed on the capabilities and limitations of prenatal screening (even the newer ccfna-based options), the actual risks associated with invasive testing, and the ability of invasive testing to provide expanded fetal information with the use of microarray analyses.

As it has been from the beginning of prenatal testing in the 1960s, counseling continues to be the most important part of the prenatal screening and diagnostic process and it is needed to facilitate clinical decisions made by women and couples. Counseling must include an accurate communication of the risks, benefits, and limitations of the aforementioned options and issues, and should be provided in a manner that strives to be free of bias, direction, and the personal opinions of the counselor.

In order to provide such counseling, we must remain informed of the ongoing work in the field of prenatal testing, a task that has become more challenging with the rapid release of a considerable amount of new information on prenatal screening technologies over the past 2 years. This will likely continue, and perhaps become even more frenetic, with the expected release of additional information on the clinical applications of ccfna technologies in the near future as well as the development of new technologies applicable for the screening and diagnosis of fetal abnormalities.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.

- Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):485–487.

- Ashoor G, Syngelaki A, Wagner M, Birdir C, Nicolaides KH. Chromosome-selective sequencing of maternal plasma cell–free DNA for first-trimester detection of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(4):322.e1–e5.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. Committee Opinion No. 545: Noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1532–1534.

- Bianchi DW, Platt LD, Goldberg JD, et al; MatErnal Blood IS Source to Accurately diagnose fetal aneuploidy (MELISSA) Study Group. Genome-wide fetal aneuploidy detection by maternal plasma DNA-sequencing. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):890–901.

- Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: An international clinical validation study. Genet Med. 2011;13(11):913–920.

- Palomaki GE, Deciu C, Kloza EM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as Down syndrome: An international collaborative study. Genet Med. 2012;14(3):296–305.

- Bianchi DW, Parker RL, Wentworth J, et al; CARE Study Group. DNA sequencing versus standard prenatal aneuploidy screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):799–808.

- Menutti MT, Cherry AM, Morrissette JJ, Dugoff L. Is it time to sound an alarm about false-positive cell-free DNA testing for fetal aneuploidy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):415−419.

- Canick JA, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to identify Down syndrome and other trisomies in multiple gestations. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(8):730–734.

- Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Gil MM, Quezada MS, Zinevich Y. Prenatal detection of fetal triploidy from cell-free DNA testing in maternal blood [published online ahead of print October 10, 2013]. Fetal Diagn Ther.

- Semango-Sprouse C, Banjevic M, Ryan A, et al. SNP-based non-invasive prenatal testing detects sex chromosome aneuploidies with high accuracy. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(7):643–649.

- Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):485–487.

- Ashoor G, Syngelaki A, Wagner M, Birdir C, Nicolaides KH. Chromosome-selective sequencing of maternal plasma cell–free DNA for first-trimester detection of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(4):322.e1–e5.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. Committee Opinion No. 545: Noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1532–1534.

- Bianchi DW, Platt LD, Goldberg JD, et al; MatErnal Blood IS Source to Accurately diagnose fetal aneuploidy (MELISSA) Study Group. Genome-wide fetal aneuploidy detection by maternal plasma DNA-sequencing. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):890–901.

- Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: An international clinical validation study. Genet Med. 2011;13(11):913–920.

- Palomaki GE, Deciu C, Kloza EM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as Down syndrome: An international collaborative study. Genet Med. 2012;14(3):296–305.

- Bianchi DW, Parker RL, Wentworth J, et al; CARE Study Group. DNA sequencing versus standard prenatal aneuploidy screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):799–808.

- Menutti MT, Cherry AM, Morrissette JJ, Dugoff L. Is it time to sound an alarm about false-positive cell-free DNA testing for fetal aneuploidy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):415−419.

- Canick JA, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to identify Down syndrome and other trisomies in multiple gestations. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(8):730–734.

- Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Gil MM, Quezada MS, Zinevich Y. Prenatal detection of fetal triploidy from cell-free DNA testing in maternal blood [published online ahead of print October 10, 2013]. Fetal Diagn Ther.

- Semango-Sprouse C, Banjevic M, Ryan A, et al. SNP-based non-invasive prenatal testing detects sex chromosome aneuploidies with high accuracy. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(7):643–649.

Adding infertility assessment and treatment to your practice

At the 62nd Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Dr. Jensen offered efficient strategies to generalist ObGyns to incorporate infertility assessment and treatment into their already busy practices. Here, a 7-minute audiocast with Dr. Jensen on the key takeaways from her seminar, "Managing infertility without IVF: The old-fashioned way."

At the 62nd Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Dr. Jensen offered efficient strategies to generalist ObGyns to incorporate infertility assessment and treatment into their already busy practices. Here, a 7-minute audiocast with Dr. Jensen on the key takeaways from her seminar, "Managing infertility without IVF: The old-fashioned way."

At the 62nd Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Dr. Jensen offered efficient strategies to generalist ObGyns to incorporate infertility assessment and treatment into their already busy practices. Here, a 7-minute audiocast with Dr. Jensen on the key takeaways from her seminar, "Managing infertility without IVF: The old-fashioned way."

Why it's important to open the sexual health dialogue

In this 5-minute audiocast, Dr. Krychman offers key takeaways from his seminar, "Sexuality in the Elder Woman," at the 62nd Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

In this 5-minute audiocast, Dr. Krychman offers key takeaways from his seminar, "Sexuality in the Elder Woman," at the 62nd Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

In this 5-minute audiocast, Dr. Krychman offers key takeaways from his seminar, "Sexuality in the Elder Woman," at the 62nd Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

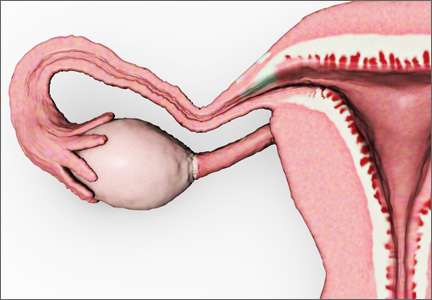

Should the adnexae be removed during hysterectomy for benign disease to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer?

The decision-making surrounding gynecologic surgery for benign disease is increasingly complex. Patients and their physicians must balance the potential benefits of salpingo-oophorectomy against possible adverse consequence as they consider various health goals, including longevity, cancer risk, and quality of life.

Chan and colleagues add important data to our understanding of this equation. Analyzing a large cohort of patients from Kaiser Permanente Northern California who underwent hysterectomy for benign disease, they found that removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries significantly reduced the risk of developing ovarian cancer. The incidence of ovarian cancer per 100,000 person-years was 26.2 for women undergoing hysterectomy alone (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.5–37.0), 17.5 for hysterectomy with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0–39.1), and 1.7 for hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.4–3.0).

The hazard ratio (HR) for ovarian cancer was 0.58 for women undergoing unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.18–1.90) and 0.12 for women undergoing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.05–0.28), compared with women undergoing hysterectomy alone.

Notable strengths of the analysis include the large size of the study population and the duration of patient follow-up (18 years). The authors acknowledge several limitations of the study, including the lack of data on BRCA mutation status and family history of cancer, as well as several other demographic data points possibly relevant to a risk of developing adnexal or peritoneal malignancy.

Related article: What is the gynecologist’s role in the care of BRCA previvors? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2013)

Keep these findings in context

As the authors discuss, this report should be considered in the context of other work suggesting that the lower mortality rate associated with ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease arises mostly from a protective effect against cardiovascular disease (CVD)—perhaps from subclinical hormone production following menopause. Given that CVD remains the leading cause of death among American women, an individualized assessment of risk is necessary when planning the extent of surgery in this circumstance.

Related article: Oophorectomy or salpingectomy—which makes more sense? William H. Parker, MD (March 2014)

It also is interesting to consider the authors’ finding of a notable but statistically insignificant decrease in the risk of ovarian cancer associated with removal of only one tube and ovary. However, recognizing the possible limitations of their demographic information on this point, they suggest that this may be an area for further investigation, which would necessarily include characterization of the trends in the laterality of adnexal cancers. The preservation of hormonal function makes this an interesting option to consider.

We also need to further investigate the role of bilateral salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy, with ovarian conservation, as an alternate therapeutic option, based upon evidence that extrauterine serous carcinoma may to a significant degree arise from the tubal epithelium rather than the ovarian cortex.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Removal of the adnexae significantly reduces the risk of ovarian cancer among the cohort of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease. However, the decision of whether or not to remove the adnexae when planning surgery should take into account other factors that may affect the risk of adnexal malignancy, including family history and BRCA mutation status, as well as other patient comorbidities.

Andrew W. Menzin, MD

Tell us what you think!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about this or other current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include your name, city and state.

Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

The decision-making surrounding gynecologic surgery for benign disease is increasingly complex. Patients and their physicians must balance the potential benefits of salpingo-oophorectomy against possible adverse consequence as they consider various health goals, including longevity, cancer risk, and quality of life.

Chan and colleagues add important data to our understanding of this equation. Analyzing a large cohort of patients from Kaiser Permanente Northern California who underwent hysterectomy for benign disease, they found that removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries significantly reduced the risk of developing ovarian cancer. The incidence of ovarian cancer per 100,000 person-years was 26.2 for women undergoing hysterectomy alone (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.5–37.0), 17.5 for hysterectomy with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0–39.1), and 1.7 for hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.4–3.0).

The hazard ratio (HR) for ovarian cancer was 0.58 for women undergoing unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.18–1.90) and 0.12 for women undergoing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.05–0.28), compared with women undergoing hysterectomy alone.

Notable strengths of the analysis include the large size of the study population and the duration of patient follow-up (18 years). The authors acknowledge several limitations of the study, including the lack of data on BRCA mutation status and family history of cancer, as well as several other demographic data points possibly relevant to a risk of developing adnexal or peritoneal malignancy.

Related article: What is the gynecologist’s role in the care of BRCA previvors? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2013)

Keep these findings in context

As the authors discuss, this report should be considered in the context of other work suggesting that the lower mortality rate associated with ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease arises mostly from a protective effect against cardiovascular disease (CVD)—perhaps from subclinical hormone production following menopause. Given that CVD remains the leading cause of death among American women, an individualized assessment of risk is necessary when planning the extent of surgery in this circumstance.

Related article: Oophorectomy or salpingectomy—which makes more sense? William H. Parker, MD (March 2014)

It also is interesting to consider the authors’ finding of a notable but statistically insignificant decrease in the risk of ovarian cancer associated with removal of only one tube and ovary. However, recognizing the possible limitations of their demographic information on this point, they suggest that this may be an area for further investigation, which would necessarily include characterization of the trends in the laterality of adnexal cancers. The preservation of hormonal function makes this an interesting option to consider.

We also need to further investigate the role of bilateral salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy, with ovarian conservation, as an alternate therapeutic option, based upon evidence that extrauterine serous carcinoma may to a significant degree arise from the tubal epithelium rather than the ovarian cortex.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Removal of the adnexae significantly reduces the risk of ovarian cancer among the cohort of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease. However, the decision of whether or not to remove the adnexae when planning surgery should take into account other factors that may affect the risk of adnexal malignancy, including family history and BRCA mutation status, as well as other patient comorbidities.

Andrew W. Menzin, MD

Tell us what you think!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about this or other current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include your name, city and state.

Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

The decision-making surrounding gynecologic surgery for benign disease is increasingly complex. Patients and their physicians must balance the potential benefits of salpingo-oophorectomy against possible adverse consequence as they consider various health goals, including longevity, cancer risk, and quality of life.

Chan and colleagues add important data to our understanding of this equation. Analyzing a large cohort of patients from Kaiser Permanente Northern California who underwent hysterectomy for benign disease, they found that removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries significantly reduced the risk of developing ovarian cancer. The incidence of ovarian cancer per 100,000 person-years was 26.2 for women undergoing hysterectomy alone (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.5–37.0), 17.5 for hysterectomy with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0–39.1), and 1.7 for hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.4–3.0).

The hazard ratio (HR) for ovarian cancer was 0.58 for women undergoing unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.18–1.90) and 0.12 for women undergoing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.05–0.28), compared with women undergoing hysterectomy alone.

Notable strengths of the analysis include the large size of the study population and the duration of patient follow-up (18 years). The authors acknowledge several limitations of the study, including the lack of data on BRCA mutation status and family history of cancer, as well as several other demographic data points possibly relevant to a risk of developing adnexal or peritoneal malignancy.

Related article: What is the gynecologist’s role in the care of BRCA previvors? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2013)

Keep these findings in context

As the authors discuss, this report should be considered in the context of other work suggesting that the lower mortality rate associated with ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease arises mostly from a protective effect against cardiovascular disease (CVD)—perhaps from subclinical hormone production following menopause. Given that CVD remains the leading cause of death among American women, an individualized assessment of risk is necessary when planning the extent of surgery in this circumstance.

Related article: Oophorectomy or salpingectomy—which makes more sense? William H. Parker, MD (March 2014)

It also is interesting to consider the authors’ finding of a notable but statistically insignificant decrease in the risk of ovarian cancer associated with removal of only one tube and ovary. However, recognizing the possible limitations of their demographic information on this point, they suggest that this may be an area for further investigation, which would necessarily include characterization of the trends in the laterality of adnexal cancers. The preservation of hormonal function makes this an interesting option to consider.

We also need to further investigate the role of bilateral salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy, with ovarian conservation, as an alternate therapeutic option, based upon evidence that extrauterine serous carcinoma may to a significant degree arise from the tubal epithelium rather than the ovarian cortex.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Removal of the adnexae significantly reduces the risk of ovarian cancer among the cohort of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease. However, the decision of whether or not to remove the adnexae when planning surgery should take into account other factors that may affect the risk of adnexal malignancy, including family history and BRCA mutation status, as well as other patient comorbidities.

Andrew W. Menzin, MD

Tell us what you think!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about this or other current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include your name, city and state.

Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

Problem Solving In Multi-Site Hospital Medicine Groups

Serving as the lead physician for a hospital medicine group (HMG) makes for challenging work. And the challenges and complexity only increase for anyone who serves as the physician leader for multiple practice sites in the same hospital system. In my November 2013 column on multi-site HMG leaders, I listed a few of the tricky issues they face and will mention a few more here.

Large-Small Friction

Unfortunately, tension between hospitalists at the big hospital and doctors at the small, “feeder” hospitals seems pretty common, and I think it’s due largely to high stress and a wide variation in workload, neither of which are in our direct control. At facilities where there is significant tension, I’m impressed by how vigorously the hospitalists at both the small and large hospitals argue that their own site faces the most stress and challenges. (This is a little like the endless debate about who works harder, those who work with residents and those who don’t.)

The hospitalists at the small site point out that they work with little or no subspecialty help and might even have to take night call from home while working during the day. Those at the big hospital say they are the ones with the very large scope of clinical practice and that, rather than making their life easier, the presence of lots of subspecialists makes for additional work coordinating care and communicating with all parties.

Where it exists, this tension is most evident during a transfer from one of the small hospitals to the large one. After all, one of the reasons to form a system of hospitals is so that nearly all patient needs can be met at one of the facilities in the system. Yet, for many reasons, the hospitalists at the large hospital are—sometimes—not as receptive to transfers as might be ideal. They might be short staffed or facing a high census or an unusually high number of admissions from their own ED. Or, perhaps, they’re concerned that the subspecialty services for which the patient is being transferred (e.g. to be scoped by a GI doctor) won’t be as helpful or prompt as needed. Or maybe they’ve felt “burned” by their colleagues at the small hospital for past transfers that didn’t seem necessary.

The result can be that the doctors at the smaller hospital complain that the “mother ship” hospitalists often are unfriendly and unreceptive to transfer requests. Although there may not be a definitive “cure” for this issue, there are several ways to help address the problem.

- In my last column, I mentioned the value of one or more in-person meetings between those who tend to be on the sending and receiving end of transfers, to establish some criteria regarding transfers that are appropriate and review the process of requesting a transfer and making the associated arrangements. In most cases there will be value in the parties meeting routinely—perhaps two to four times annually—to review how the system is working and address any difficulties.

- Periodic social meetings among the hospitalists at each site will help to form relationships that can make it less likely that any conversation about transfers will go in an unhelpful direction. Things can be very different when the people on each end of the phone call know each other personally.

- Record the phone calls between those seeking and accepting/declining each transfer. Scott Rissmiller, MD, the lead hospitalist for the 17 practice sites in Carolinas Healthcare, has said that having underperforming doctors listen to recordings of their phone calls about transfers has, in most cases he’s been involved with, proven to be a very effective way to encourage improvement.

Shared Staffing

The small hospitals in many systems sometimes struggle to find a way to provide economical night coverage. Hospitals below a certain size find it very difficult to justify a separate, in-house night provider. Some hospital systems have had success sharing night staffing, with the large hospital’s night hospitalist, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant providing telephone coverage for “cross cover” issues that arise after hours.

For example, when a nurse at the small hospital needs to contact a night hospitalist, staff will page the provider at the big hospital, and, in many cases, the issue can be managed effectively by phone. This works best when both hospitals are on the same electronic medical record, so that the responding provider can look through the record as needed.

The hospitalist at the small hospital typically stays on back-up call and is contacted if bedside attention is required.

Or, if the large and small hospitals are a short drive apart, the night hospitalist at the large facility might make the short drive to the small hospital when needed. In the case of emergencies (i.e., a code blue), the in-house night ED physician is relied on as the first responder.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Serving as the lead physician for a hospital medicine group (HMG) makes for challenging work. And the challenges and complexity only increase for anyone who serves as the physician leader for multiple practice sites in the same hospital system. In my November 2013 column on multi-site HMG leaders, I listed a few of the tricky issues they face and will mention a few more here.

Large-Small Friction

Unfortunately, tension between hospitalists at the big hospital and doctors at the small, “feeder” hospitals seems pretty common, and I think it’s due largely to high stress and a wide variation in workload, neither of which are in our direct control. At facilities where there is significant tension, I’m impressed by how vigorously the hospitalists at both the small and large hospitals argue that their own site faces the most stress and challenges. (This is a little like the endless debate about who works harder, those who work with residents and those who don’t.)

The hospitalists at the small site point out that they work with little or no subspecialty help and might even have to take night call from home while working during the day. Those at the big hospital say they are the ones with the very large scope of clinical practice and that, rather than making their life easier, the presence of lots of subspecialists makes for additional work coordinating care and communicating with all parties.

Where it exists, this tension is most evident during a transfer from one of the small hospitals to the large one. After all, one of the reasons to form a system of hospitals is so that nearly all patient needs can be met at one of the facilities in the system. Yet, for many reasons, the hospitalists at the large hospital are—sometimes—not as receptive to transfers as might be ideal. They might be short staffed or facing a high census or an unusually high number of admissions from their own ED. Or, perhaps, they’re concerned that the subspecialty services for which the patient is being transferred (e.g. to be scoped by a GI doctor) won’t be as helpful or prompt as needed. Or maybe they’ve felt “burned” by their colleagues at the small hospital for past transfers that didn’t seem necessary.

The result can be that the doctors at the smaller hospital complain that the “mother ship” hospitalists often are unfriendly and unreceptive to transfer requests. Although there may not be a definitive “cure” for this issue, there are several ways to help address the problem.

- In my last column, I mentioned the value of one or more in-person meetings between those who tend to be on the sending and receiving end of transfers, to establish some criteria regarding transfers that are appropriate and review the process of requesting a transfer and making the associated arrangements. In most cases there will be value in the parties meeting routinely—perhaps two to four times annually—to review how the system is working and address any difficulties.

- Periodic social meetings among the hospitalists at each site will help to form relationships that can make it less likely that any conversation about transfers will go in an unhelpful direction. Things can be very different when the people on each end of the phone call know each other personally.

- Record the phone calls between those seeking and accepting/declining each transfer. Scott Rissmiller, MD, the lead hospitalist for the 17 practice sites in Carolinas Healthcare, has said that having underperforming doctors listen to recordings of their phone calls about transfers has, in most cases he’s been involved with, proven to be a very effective way to encourage improvement.

Shared Staffing

The small hospitals in many systems sometimes struggle to find a way to provide economical night coverage. Hospitals below a certain size find it very difficult to justify a separate, in-house night provider. Some hospital systems have had success sharing night staffing, with the large hospital’s night hospitalist, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant providing telephone coverage for “cross cover” issues that arise after hours.

For example, when a nurse at the small hospital needs to contact a night hospitalist, staff will page the provider at the big hospital, and, in many cases, the issue can be managed effectively by phone. This works best when both hospitals are on the same electronic medical record, so that the responding provider can look through the record as needed.

The hospitalist at the small hospital typically stays on back-up call and is contacted if bedside attention is required.

Or, if the large and small hospitals are a short drive apart, the night hospitalist at the large facility might make the short drive to the small hospital when needed. In the case of emergencies (i.e., a code blue), the in-house night ED physician is relied on as the first responder.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Serving as the lead physician for a hospital medicine group (HMG) makes for challenging work. And the challenges and complexity only increase for anyone who serves as the physician leader for multiple practice sites in the same hospital system. In my November 2013 column on multi-site HMG leaders, I listed a few of the tricky issues they face and will mention a few more here.

Large-Small Friction

Unfortunately, tension between hospitalists at the big hospital and doctors at the small, “feeder” hospitals seems pretty common, and I think it’s due largely to high stress and a wide variation in workload, neither of which are in our direct control. At facilities where there is significant tension, I’m impressed by how vigorously the hospitalists at both the small and large hospitals argue that their own site faces the most stress and challenges. (This is a little like the endless debate about who works harder, those who work with residents and those who don’t.)

The hospitalists at the small site point out that they work with little or no subspecialty help and might even have to take night call from home while working during the day. Those at the big hospital say they are the ones with the very large scope of clinical practice and that, rather than making their life easier, the presence of lots of subspecialists makes for additional work coordinating care and communicating with all parties.

Where it exists, this tension is most evident during a transfer from one of the small hospitals to the large one. After all, one of the reasons to form a system of hospitals is so that nearly all patient needs can be met at one of the facilities in the system. Yet, for many reasons, the hospitalists at the large hospital are—sometimes—not as receptive to transfers as might be ideal. They might be short staffed or facing a high census or an unusually high number of admissions from their own ED. Or, perhaps, they’re concerned that the subspecialty services for which the patient is being transferred (e.g. to be scoped by a GI doctor) won’t be as helpful or prompt as needed. Or maybe they’ve felt “burned” by their colleagues at the small hospital for past transfers that didn’t seem necessary.

The result can be that the doctors at the smaller hospital complain that the “mother ship” hospitalists often are unfriendly and unreceptive to transfer requests. Although there may not be a definitive “cure” for this issue, there are several ways to help address the problem.

- In my last column, I mentioned the value of one or more in-person meetings between those who tend to be on the sending and receiving end of transfers, to establish some criteria regarding transfers that are appropriate and review the process of requesting a transfer and making the associated arrangements. In most cases there will be value in the parties meeting routinely—perhaps two to four times annually—to review how the system is working and address any difficulties.

- Periodic social meetings among the hospitalists at each site will help to form relationships that can make it less likely that any conversation about transfers will go in an unhelpful direction. Things can be very different when the people on each end of the phone call know each other personally.

- Record the phone calls between those seeking and accepting/declining each transfer. Scott Rissmiller, MD, the lead hospitalist for the 17 practice sites in Carolinas Healthcare, has said that having underperforming doctors listen to recordings of their phone calls about transfers has, in most cases he’s been involved with, proven to be a very effective way to encourage improvement.

Shared Staffing

The small hospitals in many systems sometimes struggle to find a way to provide economical night coverage. Hospitals below a certain size find it very difficult to justify a separate, in-house night provider. Some hospital systems have had success sharing night staffing, with the large hospital’s night hospitalist, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant providing telephone coverage for “cross cover” issues that arise after hours.

For example, when a nurse at the small hospital needs to contact a night hospitalist, staff will page the provider at the big hospital, and, in many cases, the issue can be managed effectively by phone. This works best when both hospitals are on the same electronic medical record, so that the responding provider can look through the record as needed.

The hospitalist at the small hospital typically stays on back-up call and is contacted if bedside attention is required.

Or, if the large and small hospitals are a short drive apart, the night hospitalist at the large facility might make the short drive to the small hospital when needed. In the case of emergencies (i.e., a code blue), the in-house night ED physician is relied on as the first responder.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Does maternal obesity increase the risk of preterm delivery?

The developed world is in the midst of an unprecedented increase in human body mass. This increase can be attributed to widespread access to large amounts of inexpensive calories—particularly carbohydrates—and diminishing physical exertion. We have “evolved” from creatures struggling to get enough food to survive to vertebrates drowning in an ocean of calories and ease.

Although obesity clearly lies on the causal pathway for diseases such as diabetes and endometrial cancer, it also is associated with many other unhealthy behaviors and exposures. For example, obese women tend to earn less money, achieve less in school, smoke, and live farther away from markets and playgrounds—and the list of confounders goes on and on. We can measure height and weight with ease and precision, but we can’t assess and quantify most of these other confounders.

Related Article: Should you start prescribing lorcaserin or orlistat to your overweight or obese patients? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, October 2013)

Cnattingius and colleagues give us another “obesity is bad” paper, this time with the outcome of preterm delivery. They found not only an association between obesity and preterm delivery but also a “mass response effect”—that is, the association increased along with maternal BMI.

The magnitude of the associations was small (odds ratios <3.0 for preterm delivery among overweight and obese women, compared with women of normal weight), and despite valiant efforts by the investigators to control for confounding, the imprecision I mentioned above limits their findings.

I declared a personal moratorium on reading “obesity is bad” papers a few years back. Even if obesity is a real risk factor for poor perinatal outcomes and not a proxy for residual confounding, we still have no idea, short of invasive surgery, how to modify that risk. Real progress will require effective lifestyle intervention—and we know so little about how to get people to lead healthy lives. It is difficult enough to modify our own behavior (recall your New Year’s resolutions), even harder to motivate our patients to lose weight and exercise.

What this evidence means for practice

Obesity is at best a weak risk factor for preterm delivery. Unless you are more successful than I have been at getting women to modify their diet and exercise, I would not make heavy mothers feel any worse.

John M. Thorp Jr., MD

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK!

Share your thoughts on this article or on any topic relevant to ObGyns and women’s health practitioners. Tell us which topics you’d like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. We will consider publishing your letter and in a future issue.

Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.

Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

The developed world is in the midst of an unprecedented increase in human body mass. This increase can be attributed to widespread access to large amounts of inexpensive calories—particularly carbohydrates—and diminishing physical exertion. We have “evolved” from creatures struggling to get enough food to survive to vertebrates drowning in an ocean of calories and ease.

Although obesity clearly lies on the causal pathway for diseases such as diabetes and endometrial cancer, it also is associated with many other unhealthy behaviors and exposures. For example, obese women tend to earn less money, achieve less in school, smoke, and live farther away from markets and playgrounds—and the list of confounders goes on and on. We can measure height and weight with ease and precision, but we can’t assess and quantify most of these other confounders.

Related Article: Should you start prescribing lorcaserin or orlistat to your overweight or obese patients? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, October 2013)

Cnattingius and colleagues give us another “obesity is bad” paper, this time with the outcome of preterm delivery. They found not only an association between obesity and preterm delivery but also a “mass response effect”—that is, the association increased along with maternal BMI.

The magnitude of the associations was small (odds ratios <3.0 for preterm delivery among overweight and obese women, compared with women of normal weight), and despite valiant efforts by the investigators to control for confounding, the imprecision I mentioned above limits their findings.

I declared a personal moratorium on reading “obesity is bad” papers a few years back. Even if obesity is a real risk factor for poor perinatal outcomes and not a proxy for residual confounding, we still have no idea, short of invasive surgery, how to modify that risk. Real progress will require effective lifestyle intervention—and we know so little about how to get people to lead healthy lives. It is difficult enough to modify our own behavior (recall your New Year’s resolutions), even harder to motivate our patients to lose weight and exercise.

What this evidence means for practice

Obesity is at best a weak risk factor for preterm delivery. Unless you are more successful than I have been at getting women to modify their diet and exercise, I would not make heavy mothers feel any worse.

John M. Thorp Jr., MD

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK!

Share your thoughts on this article or on any topic relevant to ObGyns and women’s health practitioners. Tell us which topics you’d like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. We will consider publishing your letter and in a future issue.

Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.

Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

The developed world is in the midst of an unprecedented increase in human body mass. This increase can be attributed to widespread access to large amounts of inexpensive calories—particularly carbohydrates—and diminishing physical exertion. We have “evolved” from creatures struggling to get enough food to survive to vertebrates drowning in an ocean of calories and ease.

Although obesity clearly lies on the causal pathway for diseases such as diabetes and endometrial cancer, it also is associated with many other unhealthy behaviors and exposures. For example, obese women tend to earn less money, achieve less in school, smoke, and live farther away from markets and playgrounds—and the list of confounders goes on and on. We can measure height and weight with ease and precision, but we can’t assess and quantify most of these other confounders.

Related Article: Should you start prescribing lorcaserin or orlistat to your overweight or obese patients? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, October 2013)

Cnattingius and colleagues give us another “obesity is bad” paper, this time with the outcome of preterm delivery. They found not only an association between obesity and preterm delivery but also a “mass response effect”—that is, the association increased along with maternal BMI.

The magnitude of the associations was small (odds ratios <3.0 for preterm delivery among overweight and obese women, compared with women of normal weight), and despite valiant efforts by the investigators to control for confounding, the imprecision I mentioned above limits their findings.

I declared a personal moratorium on reading “obesity is bad” papers a few years back. Even if obesity is a real risk factor for poor perinatal outcomes and not a proxy for residual confounding, we still have no idea, short of invasive surgery, how to modify that risk. Real progress will require effective lifestyle intervention—and we know so little about how to get people to lead healthy lives. It is difficult enough to modify our own behavior (recall your New Year’s resolutions), even harder to motivate our patients to lose weight and exercise.

What this evidence means for practice

Obesity is at best a weak risk factor for preterm delivery. Unless you are more successful than I have been at getting women to modify their diet and exercise, I would not make heavy mothers feel any worse.

John M. Thorp Jr., MD

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK!

Share your thoughts on this article or on any topic relevant to ObGyns and women’s health practitioners. Tell us which topics you’d like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. We will consider publishing your letter and in a future issue.

Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.

Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions

In October 2013, the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) investigators published a comprehensive overview of findings from their two hormone therapy (HT) trials, including extended follow-up representing 13 years of cumulative data.1 When I analyzed this latest WHI report, I initially focused almost exclusively on the data presented in figures and tables within the article itself, as well as on supplemental data presented on the Internet.2 Only then did I read the discussion comments by its authors. I would recommend this approach to anyone who has not yet reviewed this publication.