User login

Is vaginal laser therapy more efficacious in improving vaginal menopausal symptoms compared with sham therapy?

Li FG, Maheux-Lacroix S, Deans R, et al. Effect of fractional carbon dioxide laser vs sham treatment on symptom severity in women with postmenopausal vaginal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:1381-1389. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14892.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Symptomatic vaginal atrophy, also referred to as genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), is common and tends to progress without treatment. When use of over-the-counter lubricants and/or moisturizers are not sufficient to address symptoms, vaginal estrogen has represented the mainstay of treatment for this condition and effectively addresses GSM symptoms.1 In recent years, some physicians have been offering vaginal carbon dioxide (CO2) laser therapy as an alternative to vaginal estrogen in the treatment of GSM; however, the efficacy of laser therapy in this setting has been uncertain.

Li and colleagues conducted a double-blind randomized trial in postmenopausal women with bothersome vaginal symptoms to compare the efficacy of the fractional CO2 vaginal laser with that of sham treatment.

Details of the study

Investigators (who received no funding from any relevant commercial entity) at a teaching hospital in Sydney, Australia, randomly assigned 85 women with menopausal symptoms suggestive of GSM to laser (n = 43) or sham (n = 42) treatment. Participants underwent 3 treatments at monthly intervals. Laser treatments were performed with standard settings (40-watt power), while sham treatments were conducted with low settings that have no tissue effect. Local anesthesia cream was employed for all procedures, and a plume evacuator was used to remove visual and olfactory effects from laser smoke.

To maintain blinding, different clinicians performed assessments and treatments. Symptom severity assessments were based on a visual analog scale (VAS) and the Vulvovaginal Symptom Questionnaire (VSQ), with a minimal clinically important difference specified as a 50% decrease in severity scores of both assessment tools. Change in severity of symptoms, including dyspareunia, dysuria, vaginal dryness, and burning and itching, was assessed at 12 months. Quality of life, the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) score, and vaginal histology were among the secondary outcomes. In addition, vaginal biopsies were performed at baseline and 6 months after study treatment.

Among the 78 women (91.7%) who completed the 12-month evaluations, the mean age was approximately 57, more than 95% were White, and approximately half were sexually active.

Results. For the laser and sham treatment groups, at 12 months no significant differences were noted for change in overall symptoms or in the most severe symptom. Many participants who received laser or sham treatment reported an improvement in vaginal symptoms 12 months following treatment.

The VAS score for a change in symptom severity in the laser-treated group compared with the sham-treated group was -17.2 versus -26.6, a difference of 9.4 (95% confidence interval [CI], -28.6 to 47.5), while the VAS score for the most severe symptom was -24.5 versus -20.4, a difference of -4.1 (95% CI, -32.5 to 24.3). The VSQ score was, respectively, -3.1 versus -1.6 (difference, -1.5 [95% CI, -5.9 to 3.0]). The mean quality of life score showed no significant differences between the laser and the sham group (6.3 vs 1.4, a difference of 4.8 [95% CI, -3.9 to 13.5]). The VHI score was 0.9 in the laser group versus 1.3 in the sham group, for a difference of -0.4 (95% CI, -4.3 to 3.6). Likewise, the proportion of participants who noted a reduction of more than 50% in bother from their most severe symptoms was similar in the 2 groups. Similarly, changes in vaginal histology were similar in the laser and sham groups.

The proportion of participants who reported adverse events, including transient vaginal discomfort, discharge, or urinary tract symptoms, was similar in the 2 groups.

Study strengths and limitations

Although other randomized studies of fractionated laser therapy for GSM have been reported, this Australian trial is the largest and longest to date and also is the first to have used sham-treated controls.

Breast cancer survivors represent a group of patients for whom treatment of GSM can be a major conundrum—induced menopause that often results when combination chemotherapy is employed in premenopausal survivors can result in severe GSM; use of aromatase inhibitors likewise can cause bothersome GSM symptoms. Since the US Food and Drug Administration lists a personal history of breast cancer as a contraindication to use of any estrogen formulation, breast cancer survivors represent a population targeted by physicians offering vaginal laser treatment. Accordingly, that approximately 50% of trial participants were breast cancer survivors means the investigators were assessing the impact of laser therapy in a population of particular clinical relevance. Of note, as with participants overall, laser therapy when employed in breast cancer survivors did not result in outcomes distinct from sham treatments.2 ●

We agree with editorialists that outside of clinical trials, we should not recommend laser for treatment of menopausal vaginal symptoms.3 Currently, a US multisite randomized trial of fractionated laser versus sham for dyspareunia in menopausal women is planned.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD, NCMP,

AND CHERYL B. IGLESIA, MD

- The 2020 genitourinary syndrome of menopause position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2020;27:976- 992. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001609.

- Li FG, Maheux-Lacroix S, Deans R, et al. Effect of fractional carbon dioxide laser vs sham treatment on symptom severity in women with postmenopausal vaginal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:1381-1389. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14892.

- Adelman M, Nygaard IE. Time for a “pause” on the use of vaginal laser. JAMA. 2021;326:1378-1380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14809.

Li FG, Maheux-Lacroix S, Deans R, et al. Effect of fractional carbon dioxide laser vs sham treatment on symptom severity in women with postmenopausal vaginal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:1381-1389. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14892.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Symptomatic vaginal atrophy, also referred to as genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), is common and tends to progress without treatment. When use of over-the-counter lubricants and/or moisturizers are not sufficient to address symptoms, vaginal estrogen has represented the mainstay of treatment for this condition and effectively addresses GSM symptoms.1 In recent years, some physicians have been offering vaginal carbon dioxide (CO2) laser therapy as an alternative to vaginal estrogen in the treatment of GSM; however, the efficacy of laser therapy in this setting has been uncertain.

Li and colleagues conducted a double-blind randomized trial in postmenopausal women with bothersome vaginal symptoms to compare the efficacy of the fractional CO2 vaginal laser with that of sham treatment.

Details of the study

Investigators (who received no funding from any relevant commercial entity) at a teaching hospital in Sydney, Australia, randomly assigned 85 women with menopausal symptoms suggestive of GSM to laser (n = 43) or sham (n = 42) treatment. Participants underwent 3 treatments at monthly intervals. Laser treatments were performed with standard settings (40-watt power), while sham treatments were conducted with low settings that have no tissue effect. Local anesthesia cream was employed for all procedures, and a plume evacuator was used to remove visual and olfactory effects from laser smoke.

To maintain blinding, different clinicians performed assessments and treatments. Symptom severity assessments were based on a visual analog scale (VAS) and the Vulvovaginal Symptom Questionnaire (VSQ), with a minimal clinically important difference specified as a 50% decrease in severity scores of both assessment tools. Change in severity of symptoms, including dyspareunia, dysuria, vaginal dryness, and burning and itching, was assessed at 12 months. Quality of life, the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) score, and vaginal histology were among the secondary outcomes. In addition, vaginal biopsies were performed at baseline and 6 months after study treatment.

Among the 78 women (91.7%) who completed the 12-month evaluations, the mean age was approximately 57, more than 95% were White, and approximately half were sexually active.

Results. For the laser and sham treatment groups, at 12 months no significant differences were noted for change in overall symptoms or in the most severe symptom. Many participants who received laser or sham treatment reported an improvement in vaginal symptoms 12 months following treatment.

The VAS score for a change in symptom severity in the laser-treated group compared with the sham-treated group was -17.2 versus -26.6, a difference of 9.4 (95% confidence interval [CI], -28.6 to 47.5), while the VAS score for the most severe symptom was -24.5 versus -20.4, a difference of -4.1 (95% CI, -32.5 to 24.3). The VSQ score was, respectively, -3.1 versus -1.6 (difference, -1.5 [95% CI, -5.9 to 3.0]). The mean quality of life score showed no significant differences between the laser and the sham group (6.3 vs 1.4, a difference of 4.8 [95% CI, -3.9 to 13.5]). The VHI score was 0.9 in the laser group versus 1.3 in the sham group, for a difference of -0.4 (95% CI, -4.3 to 3.6). Likewise, the proportion of participants who noted a reduction of more than 50% in bother from their most severe symptoms was similar in the 2 groups. Similarly, changes in vaginal histology were similar in the laser and sham groups.

The proportion of participants who reported adverse events, including transient vaginal discomfort, discharge, or urinary tract symptoms, was similar in the 2 groups.

Study strengths and limitations

Although other randomized studies of fractionated laser therapy for GSM have been reported, this Australian trial is the largest and longest to date and also is the first to have used sham-treated controls.

Breast cancer survivors represent a group of patients for whom treatment of GSM can be a major conundrum—induced menopause that often results when combination chemotherapy is employed in premenopausal survivors can result in severe GSM; use of aromatase inhibitors likewise can cause bothersome GSM symptoms. Since the US Food and Drug Administration lists a personal history of breast cancer as a contraindication to use of any estrogen formulation, breast cancer survivors represent a population targeted by physicians offering vaginal laser treatment. Accordingly, that approximately 50% of trial participants were breast cancer survivors means the investigators were assessing the impact of laser therapy in a population of particular clinical relevance. Of note, as with participants overall, laser therapy when employed in breast cancer survivors did not result in outcomes distinct from sham treatments.2 ●

We agree with editorialists that outside of clinical trials, we should not recommend laser for treatment of menopausal vaginal symptoms.3 Currently, a US multisite randomized trial of fractionated laser versus sham for dyspareunia in menopausal women is planned.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD, NCMP,

AND CHERYL B. IGLESIA, MD

Li FG, Maheux-Lacroix S, Deans R, et al. Effect of fractional carbon dioxide laser vs sham treatment on symptom severity in women with postmenopausal vaginal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:1381-1389. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14892.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Symptomatic vaginal atrophy, also referred to as genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), is common and tends to progress without treatment. When use of over-the-counter lubricants and/or moisturizers are not sufficient to address symptoms, vaginal estrogen has represented the mainstay of treatment for this condition and effectively addresses GSM symptoms.1 In recent years, some physicians have been offering vaginal carbon dioxide (CO2) laser therapy as an alternative to vaginal estrogen in the treatment of GSM; however, the efficacy of laser therapy in this setting has been uncertain.

Li and colleagues conducted a double-blind randomized trial in postmenopausal women with bothersome vaginal symptoms to compare the efficacy of the fractional CO2 vaginal laser with that of sham treatment.

Details of the study

Investigators (who received no funding from any relevant commercial entity) at a teaching hospital in Sydney, Australia, randomly assigned 85 women with menopausal symptoms suggestive of GSM to laser (n = 43) or sham (n = 42) treatment. Participants underwent 3 treatments at monthly intervals. Laser treatments were performed with standard settings (40-watt power), while sham treatments were conducted with low settings that have no tissue effect. Local anesthesia cream was employed for all procedures, and a plume evacuator was used to remove visual and olfactory effects from laser smoke.

To maintain blinding, different clinicians performed assessments and treatments. Symptom severity assessments were based on a visual analog scale (VAS) and the Vulvovaginal Symptom Questionnaire (VSQ), with a minimal clinically important difference specified as a 50% decrease in severity scores of both assessment tools. Change in severity of symptoms, including dyspareunia, dysuria, vaginal dryness, and burning and itching, was assessed at 12 months. Quality of life, the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) score, and vaginal histology were among the secondary outcomes. In addition, vaginal biopsies were performed at baseline and 6 months after study treatment.

Among the 78 women (91.7%) who completed the 12-month evaluations, the mean age was approximately 57, more than 95% were White, and approximately half were sexually active.

Results. For the laser and sham treatment groups, at 12 months no significant differences were noted for change in overall symptoms or in the most severe symptom. Many participants who received laser or sham treatment reported an improvement in vaginal symptoms 12 months following treatment.

The VAS score for a change in symptom severity in the laser-treated group compared with the sham-treated group was -17.2 versus -26.6, a difference of 9.4 (95% confidence interval [CI], -28.6 to 47.5), while the VAS score for the most severe symptom was -24.5 versus -20.4, a difference of -4.1 (95% CI, -32.5 to 24.3). The VSQ score was, respectively, -3.1 versus -1.6 (difference, -1.5 [95% CI, -5.9 to 3.0]). The mean quality of life score showed no significant differences between the laser and the sham group (6.3 vs 1.4, a difference of 4.8 [95% CI, -3.9 to 13.5]). The VHI score was 0.9 in the laser group versus 1.3 in the sham group, for a difference of -0.4 (95% CI, -4.3 to 3.6). Likewise, the proportion of participants who noted a reduction of more than 50% in bother from their most severe symptoms was similar in the 2 groups. Similarly, changes in vaginal histology were similar in the laser and sham groups.

The proportion of participants who reported adverse events, including transient vaginal discomfort, discharge, or urinary tract symptoms, was similar in the 2 groups.

Study strengths and limitations

Although other randomized studies of fractionated laser therapy for GSM have been reported, this Australian trial is the largest and longest to date and also is the first to have used sham-treated controls.

Breast cancer survivors represent a group of patients for whom treatment of GSM can be a major conundrum—induced menopause that often results when combination chemotherapy is employed in premenopausal survivors can result in severe GSM; use of aromatase inhibitors likewise can cause bothersome GSM symptoms. Since the US Food and Drug Administration lists a personal history of breast cancer as a contraindication to use of any estrogen formulation, breast cancer survivors represent a population targeted by physicians offering vaginal laser treatment. Accordingly, that approximately 50% of trial participants were breast cancer survivors means the investigators were assessing the impact of laser therapy in a population of particular clinical relevance. Of note, as with participants overall, laser therapy when employed in breast cancer survivors did not result in outcomes distinct from sham treatments.2 ●

We agree with editorialists that outside of clinical trials, we should not recommend laser for treatment of menopausal vaginal symptoms.3 Currently, a US multisite randomized trial of fractionated laser versus sham for dyspareunia in menopausal women is planned.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD, NCMP,

AND CHERYL B. IGLESIA, MD

- The 2020 genitourinary syndrome of menopause position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2020;27:976- 992. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001609.

- Li FG, Maheux-Lacroix S, Deans R, et al. Effect of fractional carbon dioxide laser vs sham treatment on symptom severity in women with postmenopausal vaginal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:1381-1389. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14892.

- Adelman M, Nygaard IE. Time for a “pause” on the use of vaginal laser. JAMA. 2021;326:1378-1380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14809.

- The 2020 genitourinary syndrome of menopause position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2020;27:976- 992. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001609.

- Li FG, Maheux-Lacroix S, Deans R, et al. Effect of fractional carbon dioxide laser vs sham treatment on symptom severity in women with postmenopausal vaginal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:1381-1389. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14892.

- Adelman M, Nygaard IE. Time for a “pause” on the use of vaginal laser. JAMA. 2021;326:1378-1380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14809.

Remote and in-home prenatal care: Safe, inclusive, and here to stay

For much of the general public, in-home care from a physician is akin to the rotary telephone: a feature of a bygone age, long since replaced by vastly different systems. While approximately 40% of physician-patient interactions in 1930 were house calls, by the early 1980s this had dwindled to less than 1%,1 with almost all physician-patient encounters taking place in a clinical setting, whether in a hospital or in a free-standing clinic. In the last 2 decades, a smattering of primary care and medical subspecialty clinicians started to incorporate some in-home care into their practices in the form of telemedicine, using video and telephone technology to facilitate care outside of the clinical setting, and by 2016, approximately 15% of physicians reported using some form of telemedicine in their interactions with patients.2

Despite these advances, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, obstetricians lagged significantly behind in their use of at-home or remote care. Although there were some efforts to promote a hybrid care model that incorporated prenatal telemedicine,3 pre-pandemic ObGyn was one of the least likely fields to offer telemedicine to their patients, with only 9% of practices offering such services.2 In this article, we discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a shift from traditional, in-person care to a hybrid remote model and how this may benefit obstetrics patients as well as clinicians.

Pre-pandemic patient management

The traditional model of prenatal care presents a particularly intense time period for patients in terms of its demands. Women who are pregnant and start care in their first trimester typically have 12 to 14 visits during the subsequent 6 to 7 months, with additional visits for those with high-risk pregnancies. Although some of these visits coincide with the need for in-person laboratory work or imaging, many are chiefly oriented around assessment of vital signs or counseling. These frequent prenatal visits represent a significant commitment from patients in terms of transportation, time off work, and childcare resources—all of which may be exacerbated for patients who need to receive their care from overbooked, high-risk specialists.

After delivery, attending an in-person postpartum visit with a newborn can be even more daunting. Despite the increased recognition from professional groups of the importance of postpartum care to support breastfeeding, physical recovery, and mental health, as many as 40% of recently delivered patients do not attend their scheduled postpartum visit(s).4 Still, before 2020, few obstetricians had revised their workflows to “meet patients where they are,” with many continuing to only offer in-person care and assessments.

COVID-19: An impetus for change

As with so many things, the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged our ideas of what is normal. In a sense, the pandemic has catalyzed a revolution in the prenatal care model. The very real risks of exposure and contagion during the pandemic—for clinicians and patients alike—has forced ObGyns to reexamine the actual risks and benefits of in-person and in-clinic prenatal care. As a result, many ObGyns have rapidly adopted telemedicine into practices that were strictly in-person. For example, a national survey of 172 clinicians who offered contraception counseling during the pandemic found that 91% of them were now offering telemedicine services, with 78% of those clinicians new to telemedicine.5 Similarly, although a minority of surveyed obstetricians in New York City reported using telemedicine pre-pandemic, 89% planned to continue using such technology in the future.6

Continue to: Incorporating mobile technology...

Incorporating mobile technology

Obstetricians, forced to consolidate and maximize their in-person care to protect their patients’ safety, have started to realize that many of the conversations and counseling offered to patients can be managed equally effectively with telemedicine. Furthermore, basic home monitoring devices, such as blood pressure machines, can be safely and accurately used by patients without requiring them to come to the office.

More recent research into mobile medical devices suggests that patients can safely and appropriately manage more complex tools. One such example is a mobile, self-operated, ultrasound transducer that is controlled through a smartphone (Instinct, Pulsenmore Ltd). This device was evaluated in an observational, noninterventional trial of 100 women carrying a singleton fetus at 14/0 weeks’ to 39/6 weeks’ gestation. Patients performed 1,360 self-scans, which were reviewed by a clinician in real time online or subsequently off-line. Results showed successful detection rates of 95.3% for fetal heart activity, 88.3% for body movements, 69.4% for tone, 23.8% for breathing movements, and 92.2% for normal amniotic fluid volume.7 The authors concluded that this represents a feasible solution for remote sonographic fetal assessment.

Coordinating care with health care extenders

Remote monitoring options allow patients to be safely monitored during their pregnancies while remaining at home more often, especially when used in conjunction with trained health care extenders such as registered nurses, primary care associates, or “maternity navigators” who can facilitate off-site care. In fact, many aspects of prenatal care are particularly amenable to remote medicine or non–physician-based home care. Different variations of this model of “hybrid” prenatal care may be appropriate depending upon the needs of the patient population served by a given obstetrics practice. Ideally, a prenatal care model personalizes care based on the known risk factors that are identified at the beginning of prenatal care, the anticipated barriers to care, and the patient’s own preferences. As a result, alternatives to the traditional model may be to alternate in-person and telemedicine visits,3,8 to incorporate in-person or remote group prenatal visits,9,10 or to incorporate staff with basic health care skills to serve as health care extenders in the community and provide home visits for basic monitoring, laboratory work, and patient education.11

Benefits of hybrid prenatal models

As we look ahead to the end of the pandemic, how should obstetricians view these hybrid prenatal care models? Are these models safe for patients? Were they only worthwhile to minimize infection risk, or do they have potential benefits for patients going forward?

In fact, data on the use of telemedicine in prenatal care indicate that these models may be equally as safe as the traditional model in terms of clinical outcomes and may have important additional benefits with regard to patient convenience and access to and satisfaction with care. Even audio-only prenatal televisits have been found to be equivalent to in-person visits in terms of serious perinatal outcomes.12 Common pregnancy diagnoses are also well-served by telemedicine. For example, several recent investigations of patients with gestational diabetes have found that telemedicine was as effective as standard care for glucose control.13,14 Management of hypertension during pregnancy, another antenatal condition that is commonly managed with frequent in-person check-ups, also was found to be adequately feasible with telemedicine using home monitors and symptom checklists, with high rates of patient satisfaction.15

With good evidence for safety, the added potential for patients to benefit in such hybrid models is multifactorial. For one, despite our collective hopes, the COVID-19 pandemic may have a long tail. Vaccine hesitancy and COVID-19 variants may mean that clinicians will have to consider the real threat of infection risk in the clinic setting for years to come. In-home prenatal care also provides a wide variety of social, economic, and psychological benefits for pregnant women across various patient populations. The pandemic has introduced many patients to the full potential of working and meeting remotely; pregnant patients are becoming more familiar with these technology platforms and appreciate its incorporation into their busy lives.5 Furthermore, hybrid models actually can provide otherwise “nonadherent” patients with better access to care. From the patient perspective, an in-person 15-minute health care provider visit actually represents a significant commitment of time and resources (ie, hours spent on public transportation, lost wages for those with inflexible work schedules, and childcare costs for patients discouraged from bringing their children to prenatal visits). Especially for patients with fewer socioeconomic resources, these barriers to in-person clinic visits may be daunting, if not insurmountable; the option of remote visits or house calls reduces these barriers and facilitates care.16

Such hybrid models benefit prenatal clinicians as well. In addition to a decreased risk of infection, clinicians may be able to attract a wider potential prenatal patient population with telemedicine by appealing to younger and potentially more technology-savvy patients.17 Importantly, telemedicine is increasingly recognized as on par with in-person visits in many billing algorithms. Changes during the pandemic led Medicare to cover telemedicine visits as well as in-person visits18,19; among other groundbreaking changes, new patients can have an initial billable visit via telemedicine. Although the billing landscape will likely continue to evolve, such changes allow clinicians to focus on patient safety and convenience without financial risk to their practices.

The future of prenatal appointment scheduling

The future of prenatal care certainly doesn’t look like a dozen 15-minute visits in a private physician’s office. While these emerging hybrid models of prenatal care certainly can benefit patients with low-risk uncomplicated pregnancies, they are already being adopted by clinicians who care for patients with antenatal complications that require specialist consultation; for those with conditions that require frequent, low-complexity check-ins (gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, history of pre-term birth, etc.); and for patients who struggle with financial or logistical barriers to in-person care. Although obstetrics may have lagged behind other subspecialties in revising its traditional health care models, the pandemic has opened up a new world of possibilities of remote and in-home care for this field. ●

- Kao H, Conant R, Soriano T, et al. The past, present, and future of house calls. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:19-34. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2008.10.005.

- Kane CK, Gillis K. The use of telemedicine by physicians: still the exception rather than the rule. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37:1923-1930. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05077.

- Weigel G, Frederiksen B, Ranji U. Telemedicine and pregnancy care. Kaiser Family Foundation website. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/telemedicine-and-pregnancy-care. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633.

- Stifani BM, Avila K, Levi EE. Telemedicine for contraceptive counseling: an exploratory survey of US family planning providers following rapid adoption of services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contraception. 2021;103:157-162. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.11.006.

- Madden N, Emeruwa UN, Friedman AM, et al. Telehealth uptake into prenatal care and provider attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:1005-1014. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1712939.

- Hadar E, Wolff L, Tenenbaum-Gavish K, et al. Mobile self-operated home ultrasound system for remote fetal assessment during pregnancy. Telemed J E Health. 2021. doi:10.1089/tmj.2020.0541.

- Thomas Jefferson University Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine. Jefferson Maternal Fetal Medicine COVID19 Preparedness. Version 2.1. March 19, 2020. https://communities.smfm.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=a109df77-74fe-462b-87fb-895d6ee7d0e6. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, et al. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 pt 1):330-339. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23.

- Wicklund M. Oakland launches telehealth program for Black prenatal, postpartum care. Telehealth News. https://mhealthintelligence.com/news/oakland-launches-telehealth-program-for-black-prenatal-postpartum-care. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Home-based pregnancy care. CayabaCare website. https://www.cayabacare.com. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Duryea EL, Adhikari EH, Ambia A, et al. Comparison between in-person and audio-only virtual prenatal visits and perinatal outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e215854. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5854.

- Ming WK, Mackillop LH, Farmer AJ, et al. Telemedicine technologies for diabetes in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e290. doi:10.2196/jmir.6556.

- Tian Y, Zhang S, Huang F, et al. Comparing the efficacies of telemedicine and standard prenatal care on blood glucose control in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9:e22881. doi:10.2196/22881.

- van den Heuvel JFM, Kariman SS, van Solinge WW, et al. SAFE@HOME – feasibility study of a telemonitoring platform combining blood pressure and preeclampsia symptoms in pregnancy care. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;240:226-231. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.07.012.

- Dixon-Shambley K, Gabbe PT. Using telehealth approaches to address social determinants of health and improve pregnancy and postpartum outcomes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2021;64:333-344. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000611.

- Eruchalu CN, Pichardo MS, Bharadwaj M, et al. The expanding digital divide: digital health access inequities during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. J Urban Health. 2021;98:183-186. doi:10.1007/s11524-020-00508-9.

- COVID-19 FAQs for obstetrician-gynecologists, telehealth. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid-19-faqs-for-ob-gyns-telehealth. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Managing patients remotely: billing for digital and telehealth services. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. Updated October 19, 2020. https://www.acog.org/practice-management/coding/coding-library/managing-patients-remotely-billing-for-digital-and-telehealth-services. Accessed August 23, 2021.

For much of the general public, in-home care from a physician is akin to the rotary telephone: a feature of a bygone age, long since replaced by vastly different systems. While approximately 40% of physician-patient interactions in 1930 were house calls, by the early 1980s this had dwindled to less than 1%,1 with almost all physician-patient encounters taking place in a clinical setting, whether in a hospital or in a free-standing clinic. In the last 2 decades, a smattering of primary care and medical subspecialty clinicians started to incorporate some in-home care into their practices in the form of telemedicine, using video and telephone technology to facilitate care outside of the clinical setting, and by 2016, approximately 15% of physicians reported using some form of telemedicine in their interactions with patients.2

Despite these advances, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, obstetricians lagged significantly behind in their use of at-home or remote care. Although there were some efforts to promote a hybrid care model that incorporated prenatal telemedicine,3 pre-pandemic ObGyn was one of the least likely fields to offer telemedicine to their patients, with only 9% of practices offering such services.2 In this article, we discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a shift from traditional, in-person care to a hybrid remote model and how this may benefit obstetrics patients as well as clinicians.

Pre-pandemic patient management

The traditional model of prenatal care presents a particularly intense time period for patients in terms of its demands. Women who are pregnant and start care in their first trimester typically have 12 to 14 visits during the subsequent 6 to 7 months, with additional visits for those with high-risk pregnancies. Although some of these visits coincide with the need for in-person laboratory work or imaging, many are chiefly oriented around assessment of vital signs or counseling. These frequent prenatal visits represent a significant commitment from patients in terms of transportation, time off work, and childcare resources—all of which may be exacerbated for patients who need to receive their care from overbooked, high-risk specialists.

After delivery, attending an in-person postpartum visit with a newborn can be even more daunting. Despite the increased recognition from professional groups of the importance of postpartum care to support breastfeeding, physical recovery, and mental health, as many as 40% of recently delivered patients do not attend their scheduled postpartum visit(s).4 Still, before 2020, few obstetricians had revised their workflows to “meet patients where they are,” with many continuing to only offer in-person care and assessments.

COVID-19: An impetus for change

As with so many things, the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged our ideas of what is normal. In a sense, the pandemic has catalyzed a revolution in the prenatal care model. The very real risks of exposure and contagion during the pandemic—for clinicians and patients alike—has forced ObGyns to reexamine the actual risks and benefits of in-person and in-clinic prenatal care. As a result, many ObGyns have rapidly adopted telemedicine into practices that were strictly in-person. For example, a national survey of 172 clinicians who offered contraception counseling during the pandemic found that 91% of them were now offering telemedicine services, with 78% of those clinicians new to telemedicine.5 Similarly, although a minority of surveyed obstetricians in New York City reported using telemedicine pre-pandemic, 89% planned to continue using such technology in the future.6

Continue to: Incorporating mobile technology...

Incorporating mobile technology

Obstetricians, forced to consolidate and maximize their in-person care to protect their patients’ safety, have started to realize that many of the conversations and counseling offered to patients can be managed equally effectively with telemedicine. Furthermore, basic home monitoring devices, such as blood pressure machines, can be safely and accurately used by patients without requiring them to come to the office.

More recent research into mobile medical devices suggests that patients can safely and appropriately manage more complex tools. One such example is a mobile, self-operated, ultrasound transducer that is controlled through a smartphone (Instinct, Pulsenmore Ltd). This device was evaluated in an observational, noninterventional trial of 100 women carrying a singleton fetus at 14/0 weeks’ to 39/6 weeks’ gestation. Patients performed 1,360 self-scans, which were reviewed by a clinician in real time online or subsequently off-line. Results showed successful detection rates of 95.3% for fetal heart activity, 88.3% for body movements, 69.4% for tone, 23.8% for breathing movements, and 92.2% for normal amniotic fluid volume.7 The authors concluded that this represents a feasible solution for remote sonographic fetal assessment.

Coordinating care with health care extenders

Remote monitoring options allow patients to be safely monitored during their pregnancies while remaining at home more often, especially when used in conjunction with trained health care extenders such as registered nurses, primary care associates, or “maternity navigators” who can facilitate off-site care. In fact, many aspects of prenatal care are particularly amenable to remote medicine or non–physician-based home care. Different variations of this model of “hybrid” prenatal care may be appropriate depending upon the needs of the patient population served by a given obstetrics practice. Ideally, a prenatal care model personalizes care based on the known risk factors that are identified at the beginning of prenatal care, the anticipated barriers to care, and the patient’s own preferences. As a result, alternatives to the traditional model may be to alternate in-person and telemedicine visits,3,8 to incorporate in-person or remote group prenatal visits,9,10 or to incorporate staff with basic health care skills to serve as health care extenders in the community and provide home visits for basic monitoring, laboratory work, and patient education.11

Benefits of hybrid prenatal models

As we look ahead to the end of the pandemic, how should obstetricians view these hybrid prenatal care models? Are these models safe for patients? Were they only worthwhile to minimize infection risk, or do they have potential benefits for patients going forward?

In fact, data on the use of telemedicine in prenatal care indicate that these models may be equally as safe as the traditional model in terms of clinical outcomes and may have important additional benefits with regard to patient convenience and access to and satisfaction with care. Even audio-only prenatal televisits have been found to be equivalent to in-person visits in terms of serious perinatal outcomes.12 Common pregnancy diagnoses are also well-served by telemedicine. For example, several recent investigations of patients with gestational diabetes have found that telemedicine was as effective as standard care for glucose control.13,14 Management of hypertension during pregnancy, another antenatal condition that is commonly managed with frequent in-person check-ups, also was found to be adequately feasible with telemedicine using home monitors and symptom checklists, with high rates of patient satisfaction.15

With good evidence for safety, the added potential for patients to benefit in such hybrid models is multifactorial. For one, despite our collective hopes, the COVID-19 pandemic may have a long tail. Vaccine hesitancy and COVID-19 variants may mean that clinicians will have to consider the real threat of infection risk in the clinic setting for years to come. In-home prenatal care also provides a wide variety of social, economic, and psychological benefits for pregnant women across various patient populations. The pandemic has introduced many patients to the full potential of working and meeting remotely; pregnant patients are becoming more familiar with these technology platforms and appreciate its incorporation into their busy lives.5 Furthermore, hybrid models actually can provide otherwise “nonadherent” patients with better access to care. From the patient perspective, an in-person 15-minute health care provider visit actually represents a significant commitment of time and resources (ie, hours spent on public transportation, lost wages for those with inflexible work schedules, and childcare costs for patients discouraged from bringing their children to prenatal visits). Especially for patients with fewer socioeconomic resources, these barriers to in-person clinic visits may be daunting, if not insurmountable; the option of remote visits or house calls reduces these barriers and facilitates care.16

Such hybrid models benefit prenatal clinicians as well. In addition to a decreased risk of infection, clinicians may be able to attract a wider potential prenatal patient population with telemedicine by appealing to younger and potentially more technology-savvy patients.17 Importantly, telemedicine is increasingly recognized as on par with in-person visits in many billing algorithms. Changes during the pandemic led Medicare to cover telemedicine visits as well as in-person visits18,19; among other groundbreaking changes, new patients can have an initial billable visit via telemedicine. Although the billing landscape will likely continue to evolve, such changes allow clinicians to focus on patient safety and convenience without financial risk to their practices.

The future of prenatal appointment scheduling

The future of prenatal care certainly doesn’t look like a dozen 15-minute visits in a private physician’s office. While these emerging hybrid models of prenatal care certainly can benefit patients with low-risk uncomplicated pregnancies, they are already being adopted by clinicians who care for patients with antenatal complications that require specialist consultation; for those with conditions that require frequent, low-complexity check-ins (gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, history of pre-term birth, etc.); and for patients who struggle with financial or logistical barriers to in-person care. Although obstetrics may have lagged behind other subspecialties in revising its traditional health care models, the pandemic has opened up a new world of possibilities of remote and in-home care for this field. ●

For much of the general public, in-home care from a physician is akin to the rotary telephone: a feature of a bygone age, long since replaced by vastly different systems. While approximately 40% of physician-patient interactions in 1930 were house calls, by the early 1980s this had dwindled to less than 1%,1 with almost all physician-patient encounters taking place in a clinical setting, whether in a hospital or in a free-standing clinic. In the last 2 decades, a smattering of primary care and medical subspecialty clinicians started to incorporate some in-home care into their practices in the form of telemedicine, using video and telephone technology to facilitate care outside of the clinical setting, and by 2016, approximately 15% of physicians reported using some form of telemedicine in their interactions with patients.2

Despite these advances, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, obstetricians lagged significantly behind in their use of at-home or remote care. Although there were some efforts to promote a hybrid care model that incorporated prenatal telemedicine,3 pre-pandemic ObGyn was one of the least likely fields to offer telemedicine to their patients, with only 9% of practices offering such services.2 In this article, we discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a shift from traditional, in-person care to a hybrid remote model and how this may benefit obstetrics patients as well as clinicians.

Pre-pandemic patient management

The traditional model of prenatal care presents a particularly intense time period for patients in terms of its demands. Women who are pregnant and start care in their first trimester typically have 12 to 14 visits during the subsequent 6 to 7 months, with additional visits for those with high-risk pregnancies. Although some of these visits coincide with the need for in-person laboratory work or imaging, many are chiefly oriented around assessment of vital signs or counseling. These frequent prenatal visits represent a significant commitment from patients in terms of transportation, time off work, and childcare resources—all of which may be exacerbated for patients who need to receive their care from overbooked, high-risk specialists.

After delivery, attending an in-person postpartum visit with a newborn can be even more daunting. Despite the increased recognition from professional groups of the importance of postpartum care to support breastfeeding, physical recovery, and mental health, as many as 40% of recently delivered patients do not attend their scheduled postpartum visit(s).4 Still, before 2020, few obstetricians had revised their workflows to “meet patients where they are,” with many continuing to only offer in-person care and assessments.

COVID-19: An impetus for change

As with so many things, the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged our ideas of what is normal. In a sense, the pandemic has catalyzed a revolution in the prenatal care model. The very real risks of exposure and contagion during the pandemic—for clinicians and patients alike—has forced ObGyns to reexamine the actual risks and benefits of in-person and in-clinic prenatal care. As a result, many ObGyns have rapidly adopted telemedicine into practices that were strictly in-person. For example, a national survey of 172 clinicians who offered contraception counseling during the pandemic found that 91% of them were now offering telemedicine services, with 78% of those clinicians new to telemedicine.5 Similarly, although a minority of surveyed obstetricians in New York City reported using telemedicine pre-pandemic, 89% planned to continue using such technology in the future.6

Continue to: Incorporating mobile technology...

Incorporating mobile technology

Obstetricians, forced to consolidate and maximize their in-person care to protect their patients’ safety, have started to realize that many of the conversations and counseling offered to patients can be managed equally effectively with telemedicine. Furthermore, basic home monitoring devices, such as blood pressure machines, can be safely and accurately used by patients without requiring them to come to the office.

More recent research into mobile medical devices suggests that patients can safely and appropriately manage more complex tools. One such example is a mobile, self-operated, ultrasound transducer that is controlled through a smartphone (Instinct, Pulsenmore Ltd). This device was evaluated in an observational, noninterventional trial of 100 women carrying a singleton fetus at 14/0 weeks’ to 39/6 weeks’ gestation. Patients performed 1,360 self-scans, which were reviewed by a clinician in real time online or subsequently off-line. Results showed successful detection rates of 95.3% for fetal heart activity, 88.3% for body movements, 69.4% for tone, 23.8% for breathing movements, and 92.2% for normal amniotic fluid volume.7 The authors concluded that this represents a feasible solution for remote sonographic fetal assessment.

Coordinating care with health care extenders

Remote monitoring options allow patients to be safely monitored during their pregnancies while remaining at home more often, especially when used in conjunction with trained health care extenders such as registered nurses, primary care associates, or “maternity navigators” who can facilitate off-site care. In fact, many aspects of prenatal care are particularly amenable to remote medicine or non–physician-based home care. Different variations of this model of “hybrid” prenatal care may be appropriate depending upon the needs of the patient population served by a given obstetrics practice. Ideally, a prenatal care model personalizes care based on the known risk factors that are identified at the beginning of prenatal care, the anticipated barriers to care, and the patient’s own preferences. As a result, alternatives to the traditional model may be to alternate in-person and telemedicine visits,3,8 to incorporate in-person or remote group prenatal visits,9,10 or to incorporate staff with basic health care skills to serve as health care extenders in the community and provide home visits for basic monitoring, laboratory work, and patient education.11

Benefits of hybrid prenatal models

As we look ahead to the end of the pandemic, how should obstetricians view these hybrid prenatal care models? Are these models safe for patients? Were they only worthwhile to minimize infection risk, or do they have potential benefits for patients going forward?

In fact, data on the use of telemedicine in prenatal care indicate that these models may be equally as safe as the traditional model in terms of clinical outcomes and may have important additional benefits with regard to patient convenience and access to and satisfaction with care. Even audio-only prenatal televisits have been found to be equivalent to in-person visits in terms of serious perinatal outcomes.12 Common pregnancy diagnoses are also well-served by telemedicine. For example, several recent investigations of patients with gestational diabetes have found that telemedicine was as effective as standard care for glucose control.13,14 Management of hypertension during pregnancy, another antenatal condition that is commonly managed with frequent in-person check-ups, also was found to be adequately feasible with telemedicine using home monitors and symptom checklists, with high rates of patient satisfaction.15

With good evidence for safety, the added potential for patients to benefit in such hybrid models is multifactorial. For one, despite our collective hopes, the COVID-19 pandemic may have a long tail. Vaccine hesitancy and COVID-19 variants may mean that clinicians will have to consider the real threat of infection risk in the clinic setting for years to come. In-home prenatal care also provides a wide variety of social, economic, and psychological benefits for pregnant women across various patient populations. The pandemic has introduced many patients to the full potential of working and meeting remotely; pregnant patients are becoming more familiar with these technology platforms and appreciate its incorporation into their busy lives.5 Furthermore, hybrid models actually can provide otherwise “nonadherent” patients with better access to care. From the patient perspective, an in-person 15-minute health care provider visit actually represents a significant commitment of time and resources (ie, hours spent on public transportation, lost wages for those with inflexible work schedules, and childcare costs for patients discouraged from bringing their children to prenatal visits). Especially for patients with fewer socioeconomic resources, these barriers to in-person clinic visits may be daunting, if not insurmountable; the option of remote visits or house calls reduces these barriers and facilitates care.16

Such hybrid models benefit prenatal clinicians as well. In addition to a decreased risk of infection, clinicians may be able to attract a wider potential prenatal patient population with telemedicine by appealing to younger and potentially more technology-savvy patients.17 Importantly, telemedicine is increasingly recognized as on par with in-person visits in many billing algorithms. Changes during the pandemic led Medicare to cover telemedicine visits as well as in-person visits18,19; among other groundbreaking changes, new patients can have an initial billable visit via telemedicine. Although the billing landscape will likely continue to evolve, such changes allow clinicians to focus on patient safety and convenience without financial risk to their practices.

The future of prenatal appointment scheduling

The future of prenatal care certainly doesn’t look like a dozen 15-minute visits in a private physician’s office. While these emerging hybrid models of prenatal care certainly can benefit patients with low-risk uncomplicated pregnancies, they are already being adopted by clinicians who care for patients with antenatal complications that require specialist consultation; for those with conditions that require frequent, low-complexity check-ins (gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, history of pre-term birth, etc.); and for patients who struggle with financial or logistical barriers to in-person care. Although obstetrics may have lagged behind other subspecialties in revising its traditional health care models, the pandemic has opened up a new world of possibilities of remote and in-home care for this field. ●

- Kao H, Conant R, Soriano T, et al. The past, present, and future of house calls. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:19-34. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2008.10.005.

- Kane CK, Gillis K. The use of telemedicine by physicians: still the exception rather than the rule. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37:1923-1930. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05077.

- Weigel G, Frederiksen B, Ranji U. Telemedicine and pregnancy care. Kaiser Family Foundation website. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/telemedicine-and-pregnancy-care. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633.

- Stifani BM, Avila K, Levi EE. Telemedicine for contraceptive counseling: an exploratory survey of US family planning providers following rapid adoption of services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contraception. 2021;103:157-162. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.11.006.

- Madden N, Emeruwa UN, Friedman AM, et al. Telehealth uptake into prenatal care and provider attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:1005-1014. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1712939.

- Hadar E, Wolff L, Tenenbaum-Gavish K, et al. Mobile self-operated home ultrasound system for remote fetal assessment during pregnancy. Telemed J E Health. 2021. doi:10.1089/tmj.2020.0541.

- Thomas Jefferson University Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine. Jefferson Maternal Fetal Medicine COVID19 Preparedness. Version 2.1. March 19, 2020. https://communities.smfm.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=a109df77-74fe-462b-87fb-895d6ee7d0e6. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, et al. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 pt 1):330-339. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23.

- Wicklund M. Oakland launches telehealth program for Black prenatal, postpartum care. Telehealth News. https://mhealthintelligence.com/news/oakland-launches-telehealth-program-for-black-prenatal-postpartum-care. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Home-based pregnancy care. CayabaCare website. https://www.cayabacare.com. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Duryea EL, Adhikari EH, Ambia A, et al. Comparison between in-person and audio-only virtual prenatal visits and perinatal outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e215854. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5854.

- Ming WK, Mackillop LH, Farmer AJ, et al. Telemedicine technologies for diabetes in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e290. doi:10.2196/jmir.6556.

- Tian Y, Zhang S, Huang F, et al. Comparing the efficacies of telemedicine and standard prenatal care on blood glucose control in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9:e22881. doi:10.2196/22881.

- van den Heuvel JFM, Kariman SS, van Solinge WW, et al. SAFE@HOME – feasibility study of a telemonitoring platform combining blood pressure and preeclampsia symptoms in pregnancy care. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;240:226-231. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.07.012.

- Dixon-Shambley K, Gabbe PT. Using telehealth approaches to address social determinants of health and improve pregnancy and postpartum outcomes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2021;64:333-344. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000611.

- Eruchalu CN, Pichardo MS, Bharadwaj M, et al. The expanding digital divide: digital health access inequities during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. J Urban Health. 2021;98:183-186. doi:10.1007/s11524-020-00508-9.

- COVID-19 FAQs for obstetrician-gynecologists, telehealth. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid-19-faqs-for-ob-gyns-telehealth. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Managing patients remotely: billing for digital and telehealth services. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. Updated October 19, 2020. https://www.acog.org/practice-management/coding/coding-library/managing-patients-remotely-billing-for-digital-and-telehealth-services. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Kao H, Conant R, Soriano T, et al. The past, present, and future of house calls. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:19-34. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2008.10.005.

- Kane CK, Gillis K. The use of telemedicine by physicians: still the exception rather than the rule. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37:1923-1930. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05077.

- Weigel G, Frederiksen B, Ranji U. Telemedicine and pregnancy care. Kaiser Family Foundation website. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/telemedicine-and-pregnancy-care. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633.

- Stifani BM, Avila K, Levi EE. Telemedicine for contraceptive counseling: an exploratory survey of US family planning providers following rapid adoption of services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contraception. 2021;103:157-162. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.11.006.

- Madden N, Emeruwa UN, Friedman AM, et al. Telehealth uptake into prenatal care and provider attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:1005-1014. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1712939.

- Hadar E, Wolff L, Tenenbaum-Gavish K, et al. Mobile self-operated home ultrasound system for remote fetal assessment during pregnancy. Telemed J E Health. 2021. doi:10.1089/tmj.2020.0541.

- Thomas Jefferson University Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine. Jefferson Maternal Fetal Medicine COVID19 Preparedness. Version 2.1. March 19, 2020. https://communities.smfm.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=a109df77-74fe-462b-87fb-895d6ee7d0e6. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, et al. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 pt 1):330-339. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23.

- Wicklund M. Oakland launches telehealth program for Black prenatal, postpartum care. Telehealth News. https://mhealthintelligence.com/news/oakland-launches-telehealth-program-for-black-prenatal-postpartum-care. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Home-based pregnancy care. CayabaCare website. https://www.cayabacare.com. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Duryea EL, Adhikari EH, Ambia A, et al. Comparison between in-person and audio-only virtual prenatal visits and perinatal outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e215854. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5854.

- Ming WK, Mackillop LH, Farmer AJ, et al. Telemedicine technologies for diabetes in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e290. doi:10.2196/jmir.6556.

- Tian Y, Zhang S, Huang F, et al. Comparing the efficacies of telemedicine and standard prenatal care on blood glucose control in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9:e22881. doi:10.2196/22881.

- van den Heuvel JFM, Kariman SS, van Solinge WW, et al. SAFE@HOME – feasibility study of a telemonitoring platform combining blood pressure and preeclampsia symptoms in pregnancy care. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;240:226-231. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.07.012.

- Dixon-Shambley K, Gabbe PT. Using telehealth approaches to address social determinants of health and improve pregnancy and postpartum outcomes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2021;64:333-344. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000611.

- Eruchalu CN, Pichardo MS, Bharadwaj M, et al. The expanding digital divide: digital health access inequities during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. J Urban Health. 2021;98:183-186. doi:10.1007/s11524-020-00508-9.

- COVID-19 FAQs for obstetrician-gynecologists, telehealth. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid-19-faqs-for-ob-gyns-telehealth. Accessed August 23, 2021.

- Managing patients remotely: billing for digital and telehealth services. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. Updated October 19, 2020. https://www.acog.org/practice-management/coding/coding-library/managing-patients-remotely-billing-for-digital-and-telehealth-services. Accessed August 23, 2021.

Time to retire race- and ethnicity-based carrier screening

The social reckoning of 2020 has led to many discussions and conversations around equity and disparities. With the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a particular spotlight on health care disparities and race-based medicine. Racism in medicine is pervasive; little has been done over the years to dismantle and unlearn practices that continue to contribute to existing gaps and disparities. Race and ethnicity are both social constructs that have long been used within medical practice and in dictating the type of care an individual receives. Without a universal definition, race, ethnicity, and ancestry have long been used interchangeably within medicine and society. Appreciating that race and ethnicity-based constructs can have other social implications in health care, with their impact on structural racism beyond health care settings, these constructs may still be part of assessments and key modifiers to understanding health differences. It is imperative that medical providers examine the use of race and ethnicity within the care that they provide.

While racial determinants of health cannot be removed from historical access, utilization, and barriers related to reproductive care, guidelines structured around historical ethnicity and race further restrict universal access to carrier screening and informed reproductive testing decisions.

Carrier screening

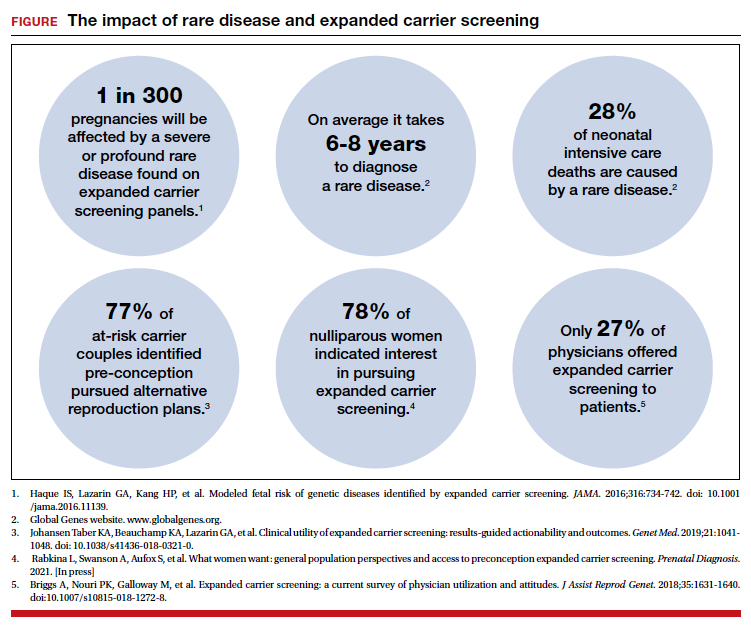

The goal of preconception and prenatal carrier screening is to provide individuals and reproductive partners with information to optimize pregnancy outcomes based on personal values and preferences.1 The practice of carrier screening began almost half a century ago with screening for individual conditions seen more frequently in certain populations, such as Tay-Sachs disease in those of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and sickle cell disease in those of African descent. Cystic fibrosis carrier screening was first recommended for individuals of Northern European descent in 2001 before being recommended for pan ethnic screening a decade later. Other individual conditions are also recommended for screening based on race/ethnicity (eg, Canavan disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, Tay-Sachs disease in individuals of Cajun or French-Canadian descent).2-4 Practice guidelines from professional societies recommend offering carrier screening for individual conditions based on condition severity, race or ethnicity, prevalence, carrier frequency, detection rates, and residual risk.1 However, this process can be problematic, as the data frequently used in updating guidelines and recommendations come primarily from studies and databases where much of the cohort is White.5,6 Failing to identify genetic associations in diverse populations limits the ability to illuminate new discoveries that inform risk management and treatment, especially for populations that are disproportionately underserved in medicine.7

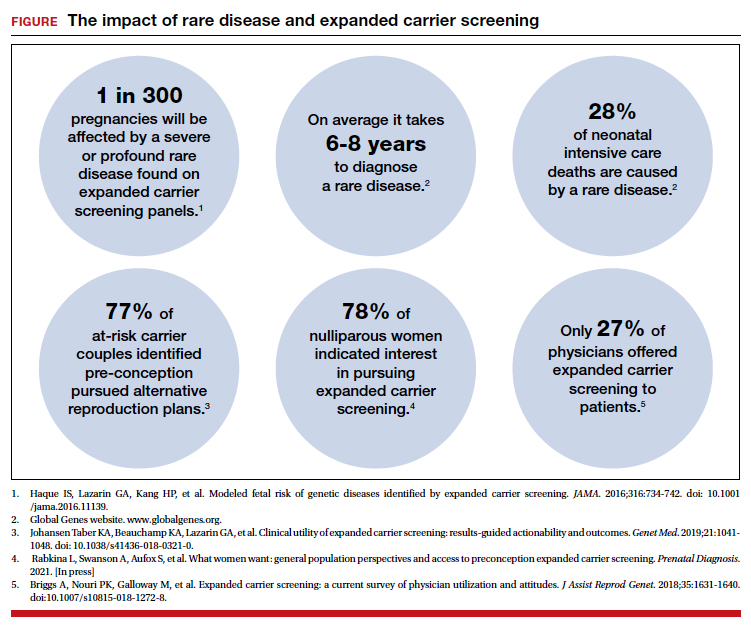

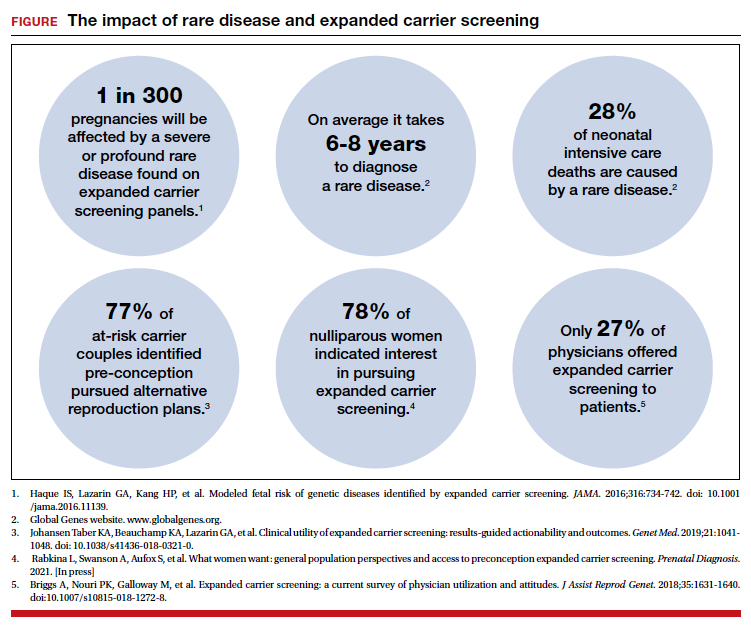

Need for expanded carrier screening

The evolution of genomics and technology within the realm of carrier screening has enabled the simultaneous screening for many serious Mendelian diseases, known as expanded carrier screening (ECS). A 2016 study illustrated that, in most racial/ethnic categories, the cumulative risk of severe and profound conditions found on ECS panels outside the guideline recommendations are greater than the risk identified by guideline-based panels.8 Additionally, a 2020 study showed that self-reported ethnicity was an imperfect indicator of genetic ancestry, with 9% of those in the cohort having a >50% genetic ancestry from a lineage inconsistent with their self-reported ethnicity.9 Data over the past decade have established the clinical utility,10 clinical validity,11 analytical validity,12 and cost-effectiveness13 of pan-ethnic ECS. In 2021, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommended a panel of pan-ethnic conditions that should be offered to all patients due to smaller ethnicity-based panels failing to provide equitable evaluation of all racial and ethnic groups.14 The guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) fall short of recommending that ECS be offered to all individuals in lieu of screening based on self-reported ethnicity.3,4

Phasing out ethnicity-based carrier screening

This begs the question: Do race, ethnicity, or ancestry have a role in carrier screening? While each may have had a role at the inception of offering carrier screening due to high costs of technology, recent studies have shown the limitations of using self-reported ethnicity in screening. Guideline-based carrier screenings miss a significant percentage of pregnancies (13% to 94%) affected by serious conditions on expanded carrier screening panels.8 Additionally, 40% of Americans cannot identify the ethnicity of all 4 grandparents.15

Founder mutations due to ancestry patterns are still present; however, stratification of care should only be pursued when the presence or absence of these markers would alter clinical management. While the reproductive risk an individual may receive varies based on their self-reported ethnicity, the clinically indicated follow-up testing is the same: offering carrier screening for the reproductive partner or gamete donor. With increased detection rates via sequencing for most autosomal recessive conditions, if the reproductive partner or gamete donor is not identified as a carrier, no further testing is generally indicated regardless of ancestry. Genotyping platforms should not be used for partner carrier screening as they primarily target common pathogenic variants based on dominant ancestry groups and do not provide the same risk reduction.

Continue to: Variant reporting...

Variant reporting

We have long known that databases and registries in the United States have an increased representation of individuals from European ancestries.5,6 However, there have been limited conversations about how the lack of representation within our databases and registries leads to inequities in guidelines and the care that we provide to patients. As a result, studies have shown higher rates of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) identified during genetic testing in non-White individuals than in Whites.16 When it comes to reporting of variants, carrier screening laboratories follow guidelines set forth by the ACMG, and most laboratories only report likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants.17 It is unknown how the higher rate of VUSs in the non-White population, and lack of data and representation in databases and software used to calculate predicted phenotype, impacts identification of at-risk carrier couples in these underrepresented populations. It is imperative that we increase knowledge and representation of variants across ethnicities to improve sensitivity and specificity across the population and not just for those of European descent.

Moving forward

Being aware of social- and race-based biases in carrier screening is important, but modifying structural systems to increase representation, access, and utility of carrier screening is a critical next step. Organizations like ACOG and ACMG have committed not only to understanding but also to addressing factors that have led to disparities and inequities in health care delivery and access.18,19 Actionable steps include offering a universal carrier screening program to all preconception and prenatal patients that addresses conditions with increased carrier frequency, in any population, defined as severe and moderate phenotype with established natural history.3,4 Educational materials should be provided to detail risks, benefits, and limitations of carrier screening, as well as shared decision making between patient and provider to align the patient’s wishes for the information provided by carrier screening.

A broader number of conditions offered through carrier screening will increase the likelihood of positive carrier results. The increase in carriers identified should be viewed as more accurate reproductive risk assessment in the context of equitable care, rather than justification for panels to be limited to specific ancestries. Simultaneous or tandem reproductive partner or donor testing can be considered to reduce clinical workload and time for results return.

In addition, increased representation of individuals who are from diverse ancestries in promotional and educational resources can reinforce that risk for Mendelian conditions is not specific to single ancestries or for targeted conditions. Future research should be conducted to examine the role of racial disparities related to carrier screening and greater inclusion and recruitment of diverse populations in data sets and research studies.

Learned biases toward race, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation, and economic status in the context of carrier screening should be examined and challenged to increase access for all patients who may benefit from this testing. For example, the use of gendered language within carrier screening guidelines and policies and how such screening is offered to patients should be examined. Guidelines do not specify what to do when someone is adopted, for instance, or does not know their ethnicity. It is important that, as genomic testing becomes more available, individuals and groups are not left behind and existing gaps are not further widened. Assessing for genetic variation that modifies for disease or treatment will be more powerful than stratifying based on race. Carrier screening panels should be comprehensive regardless of ancestry to ensure coverage for global genetic variation and to increase access for all patients to risk assessments that promote informed reproductive decision making.

Health equity requires unlearning certain behaviors

As clinicians we all have a commitment to educate and empower one another to offer care that helps promote health equity. Equitable care requires us to look at the current gaps and figure out what programs and initiatives need to be designed to address those gaps. Carrier screening is one such area in which we can work together to improve the overall care that our patients receive, but it is imperative that we examine our practices and unlearn behaviors that contribute to existing disparities. ●

- Edwards JG, Feldman G, Goldberg J, et al. Expanded carrier screening in reproductive medicine—points to consider: a joint statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, National Society of Genetic Counselors, Perinatal Quality Foundation, and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:653-662. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000000666.

- Grody WW, Thompson BH, Gregg AR, et al. ACMG position statement on prenatal/preconception expanded carrier screening. Genet Med. 2013;15:482-483. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.47.

- Committee Opinion No. 690. Summary: carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129: 595-596. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001947.

- Committee Opinion No. 691. Carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e41-e55. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000001952.

- Need AC, Goldstein DB. Next generation disparities in human genomics: concerns and remedies. Trends Genet. 2009;25:489-494. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.09.012.

- Popejoy A, Fullerton S. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature. 2016;538;161-164. doi: 10.1038/538161a.

- Ewing A. Reimagining health equity in genetic testing. Medpage Today. June 17, 2021. https://www.medpagetoday.com /opinion/second-opinions/93173. Accessed October 27, 2021.

- Haque IS, Lazarin GA, Kang HP, et al. Modeled fetal risk of genetic diseases identified by expanded carrier screening. JAMA. 2016;316:734-742. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11139.

- Kaseniit KE, Haque IS, Goldberg JD, et al. Genetic ancestry analysis on >93,000 individuals undergoing expanded carrier screening reveals limitations of ethnicity-based medical guidelines. Genet Med. 2020;22:1694-1702. doi: 10 .1038/s41436-020-0869-3.

- Johansen Taber KA, Beauchamp KA, Lazarin GA, et al. Clinical utility of expanded carrier screening: results-guided actionability and outcomes. Genet Med. 2019;21:1041-1048. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0321-0.

- Balzotti M, Meng L, Muzzey D, et al. Clinical validity of expanded carrier screening: Evaluating the gene-disease relationship in more than 200 conditions. Hum Mutat. 2020;41:1365-1371. doi: 10.1002/humu.24033.

- Hogan GJ, Vysotskaia VS, Beauchamp KA, et al. Validation of an expanded carrier screen that optimizes sensitivity via full-exon sequencing and panel-wide copy number variant identification. Clin Chem. 2018;64:1063-1073. doi: 10.1373 /clinchem.2018.286823.

- Beauchamp KA, Johansen Taber KA, Muzzey D. Clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of a 176-condition expanded carrier screen. Genet Med. 2019;21:1948-1957. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0455-8.

- Gregg AR, Aarabi M, Klugman S, et al. Screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions during pregnancy and preconception: a practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2021;23:1793-1806. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01203-z.

- Condit C, Templeton A, Bates BR, et al. Attitudinal barriers to delivery of race-targeted pharmacogenomics among informed lay persons. Genet Med. 2003;5:385-392. doi: 10 .1097/01.gim.0000087990.30961.72.

- Caswell-Jin J, Gupta T, Hall E, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in multiple-gene sequencing results for hereditary cancer risk. Genet Med. 2018;20:234-239.

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405-424. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.30.

- Gregg AR. Message from ACMG President: overcoming disparities. Genet Med. 2020;22:1758.

The social reckoning of 2020 has led to many discussions and conversations around equity and disparities. With the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a particular spotlight on health care disparities and race-based medicine. Racism in medicine is pervasive; little has been done over the years to dismantle and unlearn practices that continue to contribute to existing gaps and disparities. Race and ethnicity are both social constructs that have long been used within medical practice and in dictating the type of care an individual receives. Without a universal definition, race, ethnicity, and ancestry have long been used interchangeably within medicine and society. Appreciating that race and ethnicity-based constructs can have other social implications in health care, with their impact on structural racism beyond health care settings, these constructs may still be part of assessments and key modifiers to understanding health differences. It is imperative that medical providers examine the use of race and ethnicity within the care that they provide.

While racial determinants of health cannot be removed from historical access, utilization, and barriers related to reproductive care, guidelines structured around historical ethnicity and race further restrict universal access to carrier screening and informed reproductive testing decisions.

Carrier screening

The goal of preconception and prenatal carrier screening is to provide individuals and reproductive partners with information to optimize pregnancy outcomes based on personal values and preferences.1 The practice of carrier screening began almost half a century ago with screening for individual conditions seen more frequently in certain populations, such as Tay-Sachs disease in those of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and sickle cell disease in those of African descent. Cystic fibrosis carrier screening was first recommended for individuals of Northern European descent in 2001 before being recommended for pan ethnic screening a decade later. Other individual conditions are also recommended for screening based on race/ethnicity (eg, Canavan disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, Tay-Sachs disease in individuals of Cajun or French-Canadian descent).2-4 Practice guidelines from professional societies recommend offering carrier screening for individual conditions based on condition severity, race or ethnicity, prevalence, carrier frequency, detection rates, and residual risk.1 However, this process can be problematic, as the data frequently used in updating guidelines and recommendations come primarily from studies and databases where much of the cohort is White.5,6 Failing to identify genetic associations in diverse populations limits the ability to illuminate new discoveries that inform risk management and treatment, especially for populations that are disproportionately underserved in medicine.7

Need for expanded carrier screening