User login

Cyberspace: New Domain of Warfare

Grants Awarded to Assist Patients

Veterans' Benefits Act of 2010 Signed Into Law

Recovery Act Distributions Top $1B Mark

Medical Tourism

David Dupray, a 60-year-old uninsured coffee shop owner from Bar Harbor, Maine, had been having left leg pain on ambulation for four years. His cardiologist recommended stent placement for left iliac artery stenosis. The estimated bill: approximately $35,000.

Unable to afford the procedure, Dupray began searching the Web for affordable medical care overseas. His physician suggested Thailand. Within days, Dupray had an appointment with a cardiologist halfway around the world—at Bumrungrad Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. Dupray spent two days in the hotel-like hospital, had three stents placed in his leg arteries, and completed a cardiac stress test. The total bill: $18,000.

“I will never go to a hospital in the U.S.,” says Dupray, who represents a growing number of Americans searching for affordable healthcare in the global marketplace.

With rising U.S. healthcare costs and millions of Americans uninsured or underinsured, more American patients are seeking affordable, high-quality medical care abroad—known as “medical tourism.” In 2007, an estimated 750,000 Americans traveled abroad for medical care; the number is expected to increase to 6 million by the end of this year.1 On the flip side, only a little more than 400,000 nonresidents visited the U.S. in 2008 for the latest medical care.1 Globally, the medical tourism industry is estimated to grow into a $21 billion-a-year industry by 2012, with much of the growth expected from Western patients traveling overseas for affordable care.2

“As hospitalists, we have been seeing increasing numbers of patients going overseas for urgent and elective procedures, as it is a general perception the medical treatment overseas is less expensive,” says Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, director of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and SHM president-elect.

Physicians in U.S. hospitals encounter potential medical tourists all the time. Some are uninsured or underinsured. Some have insurance carriers that limit or exclude coverage for certain procedures and treatments. Even those with insurance sometimes struggle to pay deductibles, copays, and their costs after insurance has paid its part. Others are uncomfortable with the language barriers and cultural differences of U.S. hospitals and physicians.

Medical tourism also lures patients who are citizens of countries (e.g. Canada, the United Kingdom) that offer universal healthcare, Dr. Li says.3 For example, more expatriates from India and Malaysia are traveling to their native countries for medical care, as they receive affordable and quicker medical care while visiting family.

Hospitalists routinely care for patients requiring essential cardiac or orthopedic surgeries—conditions that are common in the medical tourism trade. With medical tourism growing in scope and popularity, it is essential that hospitalists are prepared to discuss with their patients the pros and cons of traveling for medical care. Hospitalists should be able to:

- Identify patients who might benefit from medical tourism;

- Know where and how to look for an accredited overseas facility; and

- Explain to patients the potential travel risks and complications, including insurance coverage and legal restrictions in destination countries.

A basic understanding of the industry and the issues can help guide your patients through medical decisions and help you care for those who have returned from a medical trip.

Big Menu, Discount Prices

Medical tourism offers a wide range of medical services performed in hospitals on nearly every continent, with a wide range of costs for certain procedures (Table 1, p. 26). Most surgeries cost 50% to 90% less than the average cost of the same surgery at a U.S. hospital. Many in the medical tourism industry say these types of savings have brought once-unaffordable surgery within the reach of most Americans, regardless of insurance status. For example, cardiac bypass surgery on average costs $144,000 in the U.S.; it costs about $8,500 in India.

The reasons the costs are so much less at overseas hospitals, as compared with U.S. costs, are many:

- Lower wages for providers;

- Less expensive medical devices and pharmaceutical products;

- Less involvement by third-party payors; and

- Lower malpractice premiums.4

For example, the annual liability insurance premium for a surgeon in India is $4,000; the average cost of a New York City surgeon’s liability insurance premium is $100,000.5

Brazil, Costa Rica, and Mexico are attractive destinations for cosmetic and dental surgeries; Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and India have emerged as hubs for cardiac and orthopedic surgeries (Table 1, above).6

The growth in medical tourism led the Joint Commission in 1999 to launch Joint Commission International (JCI), which ensures that offshore hospitals provide the highest-quality care to international patients (see “Ultra-Affordable Prices and No Decline in Quality of Care,” p. 28). JCI has accredited 120 overseas hospitals that meet these standards.

“Overseas hospitals are always keen in partnering with U.S. hospitals,” Dr. Li says. Collaborations, such as Johns Hopkins International Medical Center’s partnership with International Medical Clinic Singapore, and Partners Harvard Medical International’s affiliation with Wockhardt Hospitals in Mumbai, India, have helped facilitate the accreditation process and alleviate U.S. patient concerns.

Overseas hospitals not only offer greatly discounted rates than insurer-negotiated U.S. prices, but many of the international hospitals also report quality scores equal to or better than the average U.S. hospital’s.7

Before You Book a Trip …

How do patients find overseas facilities? It’s as easy as a click of the mouse.

“Our survey shows 75 percent of patients located offshore hospitals through the Internet,” says Renee-Marie Stephano, president of the Medical Tourism Association, a nonprofit group based in West Palm Beach, Fla., that was established in 2007 to promote education, transparency, and communication in the medical tourism community. Patients use overseas hospital websites, international medical coordinators, and medical tourism companies, such as PlanetHospital.com and MedRetreat.com, to find facilities and providers, and to coordinate medical travel.

“Medical tourism is currently unregulated,” Stephano says. “One of our goals is to certify medical tourism facilitators to create the best standard of practice.”

In 2007, the American Medical Association (AMA) published medical tourism guidelines to help healthcare entities engaged in overseas medical care.8 (Download a PDF of the guidelines at www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/31/medicaltourism.pdf.) The AMA suggests that:

- Medical care outside the U.S. should be voluntary, and patients should be informed of their legal rights and recourses before agreeing to travel outside the U.S.;

- Before traveling, local follow-up care should be arranged to ensure continuity of care;

- Patients should have access to physician licensing, facility accreditation, and outcomes data for both;

- Medical record transfers should follow HIPAA guidelines; and

- Patients should be informed of the potential risks of combining surgical procedures with long flights and vacation activities.

—Kenneth Mays, senior director, marketing and business development, Bumrungrad Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

Patient Concerns

Hospitalists are highly focused on a patient’s quality of care; the same can be said of some overseas hospitals that attract large numbers of medical tourists. “I think the service and quality of care provided at our hospital compares favorably with the very best American hospitals,” says Kenneth Mays, senior director of hospital marketing and business development at Bumrungrad Hospital in Bangkok.

That might be so, but the growth of medical tourism also raises concerns stateside. With sleek websites making it easy for U.S. patients to schedule procedure vacations from their kitchen tables, many U.S. physician and watchdog groups worry about patient safety, privacy, liability, and continuity of care. Although most international hospitals and physicians provide outcomes data, rarely do the benchmarks compare directly with U.S. hospital quality and safety data.

“Quality comparisons are difficult, even within U.S. hospitals, as hospitals use different methodologies to collect data,” says Stephano. “Patients have to rely on JCI accreditation, surgeon experience, volume, and outcomes to decide.”

Recent studies echo the Medical Tourism Association’s claim: Increased cardiac surgery volume at Apollo Hospitals—an 8,500-bed healthcare system with 50 locations throughout India—and Narayana Hospital in Bommasandra, India, has lowered costs, with similar, or even lower, mortality rates compared with the average U.S. hospital.7,9 Other challenges like getting medical records exist even within U.S. hospitals, so emerging platforms like Google Health and Microsoft Vault, where medical records can be uploaded at the touch of a button, “will benefit patients and providers,” Dr. Li says.

The Medical Tourism Association envisions U.S.-based physicians offering follow-up care to medical tourism patients. “Currently, we encourage patients to follow up with their primary-care physician,” Stephano says.

Dr. Li says malpractice is always a concern when traveling overseas; however, he also notes the legal system in the U.S. is strong enough “to handle any medical malpractice.” That said, a patient who experiences a poor medical outcome as the result of overseas treatment might seek legal remedies, but the reality is that malpractice laws are either nonexistent or not well implemented in some destination countries. That makes malpractice claims on overseas procedures a dicey proposition.

“Patients receiving overseas treatment need to realize that they are agreeing to the jurisdiction of the destination country,” Stephano says. Other risks associated with extended travel include exposure to regional infectious diseases and poor infrastructure in the destination country, which could undermine the benefits of medical travel.

Cost-saving benefits have led some U.S. insurance companies to begin integrating overseas medical coverage. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of South Carolina offers incentives for patients willing to obtain medical care overseas at JCI-approved hospitals. BCBS then waives deductibles and copays, and several other insurers have launched similar pilot programs.10 “We will see more of these changes,” Stephano says, “to cut costs and remain competitive.”

Immediate Impact

In 2008, U.S. healthcare spending was $2.3 trillion.11 A 2005 Institute of Medicine report suggests that 30% to 40% of current U.S. healthcare expenditure is wasted.12 U.S. lawmakers, employers, hospitals, and consumers are scrambling to find ways to reduce healthcare costs and improve efficiency. Medical tourism seems to benefit a select few Americans, only lowering U.S. healthcare spending by 1% to 2%.12

Medical tourism revenue generated in destination countries currently is limited to the private sector, but that might change soon. Government funding for healthcare initiatives in such countries as India, Brazil, and Thailand is declining. Some entrepreneurial physicians and hospitals are looking to medical tourism to fill the funding gap.

Medical tourism likely will continue to grow; so too will the legal, quality, and insurance protections for patients. Efficient resource utilization might help reduce U.S. healthcare costs, and improved distribution of destination-country resources might help improve infrastructure and access to better healthcare for their own citizens.

With their leadership skills and expertise, hospitalists can play a major role in reducing healthcare costs.

However, what actual reforms healthcare legislation brings to medical tourism remain to be seen. TH

Dr. Thakkar is a hospitalist and assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

References

- Medical tourism: Consumers in search of value. Deloitte Consulting LLP website. Available at: www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/doc/content/us%5Fchs%5FMedicalTourismStudy(1).pdf. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Pafford B. The third wave—medical tourism in the 21st century. South Med J. 2009;102(8):810-813.

- Kher U. Outsourcing your heart. Available at: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=1041533291&Fmt=7&clientId=5241&RQT=309&VName=PQD. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Forgione DA, Smith PC. Medical tourism and its impact on the US health care system. J Health Care Finance. 2007;34(1):27-35.

- Lancaster J. Surgeries, side trips for “medical tourists.” The Washington Post website. Available at: www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A497432004Oct20.html. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Horowitz MD, Rosensweig JA, Jones CA. Medical tourism: Globaliz-ation of the healthcare marketplace. MedGenMed. 2007;9(4):33.

- Milstein A, Smith M. Will the surgical world become flat? Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(1):137-141.

- New AMA guidelines on medical tourism. AMA website. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/31/medicaltourism.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2010.

- Anand G. The Henry Ford of heart surgery. Wall Street Journal website. Available at: online.wsj.com/article/SB12587589288795811.html.

- Einhorn B. Outsourcing the patients. Business Week website. Available at: www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/08_12/b40760367 77780.htm. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- . Hartman M, Martin A, Nuccio O, Catlin A, et al. Health spending growth at a historic low in 2008. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1): 147-155.

- Milstein A, Smith M. America’s new refugees—seeking affordable surgery offshore. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1637-1640.

David Dupray, a 60-year-old uninsured coffee shop owner from Bar Harbor, Maine, had been having left leg pain on ambulation for four years. His cardiologist recommended stent placement for left iliac artery stenosis. The estimated bill: approximately $35,000.

Unable to afford the procedure, Dupray began searching the Web for affordable medical care overseas. His physician suggested Thailand. Within days, Dupray had an appointment with a cardiologist halfway around the world—at Bumrungrad Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. Dupray spent two days in the hotel-like hospital, had three stents placed in his leg arteries, and completed a cardiac stress test. The total bill: $18,000.

“I will never go to a hospital in the U.S.,” says Dupray, who represents a growing number of Americans searching for affordable healthcare in the global marketplace.

With rising U.S. healthcare costs and millions of Americans uninsured or underinsured, more American patients are seeking affordable, high-quality medical care abroad—known as “medical tourism.” In 2007, an estimated 750,000 Americans traveled abroad for medical care; the number is expected to increase to 6 million by the end of this year.1 On the flip side, only a little more than 400,000 nonresidents visited the U.S. in 2008 for the latest medical care.1 Globally, the medical tourism industry is estimated to grow into a $21 billion-a-year industry by 2012, with much of the growth expected from Western patients traveling overseas for affordable care.2

“As hospitalists, we have been seeing increasing numbers of patients going overseas for urgent and elective procedures, as it is a general perception the medical treatment overseas is less expensive,” says Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, director of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and SHM president-elect.

Physicians in U.S. hospitals encounter potential medical tourists all the time. Some are uninsured or underinsured. Some have insurance carriers that limit or exclude coverage for certain procedures and treatments. Even those with insurance sometimes struggle to pay deductibles, copays, and their costs after insurance has paid its part. Others are uncomfortable with the language barriers and cultural differences of U.S. hospitals and physicians.

Medical tourism also lures patients who are citizens of countries (e.g. Canada, the United Kingdom) that offer universal healthcare, Dr. Li says.3 For example, more expatriates from India and Malaysia are traveling to their native countries for medical care, as they receive affordable and quicker medical care while visiting family.

Hospitalists routinely care for patients requiring essential cardiac or orthopedic surgeries—conditions that are common in the medical tourism trade. With medical tourism growing in scope and popularity, it is essential that hospitalists are prepared to discuss with their patients the pros and cons of traveling for medical care. Hospitalists should be able to:

- Identify patients who might benefit from medical tourism;

- Know where and how to look for an accredited overseas facility; and

- Explain to patients the potential travel risks and complications, including insurance coverage and legal restrictions in destination countries.

A basic understanding of the industry and the issues can help guide your patients through medical decisions and help you care for those who have returned from a medical trip.

Big Menu, Discount Prices

Medical tourism offers a wide range of medical services performed in hospitals on nearly every continent, with a wide range of costs for certain procedures (Table 1, p. 26). Most surgeries cost 50% to 90% less than the average cost of the same surgery at a U.S. hospital. Many in the medical tourism industry say these types of savings have brought once-unaffordable surgery within the reach of most Americans, regardless of insurance status. For example, cardiac bypass surgery on average costs $144,000 in the U.S.; it costs about $8,500 in India.

The reasons the costs are so much less at overseas hospitals, as compared with U.S. costs, are many:

- Lower wages for providers;

- Less expensive medical devices and pharmaceutical products;

- Less involvement by third-party payors; and

- Lower malpractice premiums.4

For example, the annual liability insurance premium for a surgeon in India is $4,000; the average cost of a New York City surgeon’s liability insurance premium is $100,000.5

Brazil, Costa Rica, and Mexico are attractive destinations for cosmetic and dental surgeries; Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and India have emerged as hubs for cardiac and orthopedic surgeries (Table 1, above).6

The growth in medical tourism led the Joint Commission in 1999 to launch Joint Commission International (JCI), which ensures that offshore hospitals provide the highest-quality care to international patients (see “Ultra-Affordable Prices and No Decline in Quality of Care,” p. 28). JCI has accredited 120 overseas hospitals that meet these standards.

“Overseas hospitals are always keen in partnering with U.S. hospitals,” Dr. Li says. Collaborations, such as Johns Hopkins International Medical Center’s partnership with International Medical Clinic Singapore, and Partners Harvard Medical International’s affiliation with Wockhardt Hospitals in Mumbai, India, have helped facilitate the accreditation process and alleviate U.S. patient concerns.

Overseas hospitals not only offer greatly discounted rates than insurer-negotiated U.S. prices, but many of the international hospitals also report quality scores equal to or better than the average U.S. hospital’s.7

Before You Book a Trip …

How do patients find overseas facilities? It’s as easy as a click of the mouse.

“Our survey shows 75 percent of patients located offshore hospitals through the Internet,” says Renee-Marie Stephano, president of the Medical Tourism Association, a nonprofit group based in West Palm Beach, Fla., that was established in 2007 to promote education, transparency, and communication in the medical tourism community. Patients use overseas hospital websites, international medical coordinators, and medical tourism companies, such as PlanetHospital.com and MedRetreat.com, to find facilities and providers, and to coordinate medical travel.

“Medical tourism is currently unregulated,” Stephano says. “One of our goals is to certify medical tourism facilitators to create the best standard of practice.”

In 2007, the American Medical Association (AMA) published medical tourism guidelines to help healthcare entities engaged in overseas medical care.8 (Download a PDF of the guidelines at www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/31/medicaltourism.pdf.) The AMA suggests that:

- Medical care outside the U.S. should be voluntary, and patients should be informed of their legal rights and recourses before agreeing to travel outside the U.S.;

- Before traveling, local follow-up care should be arranged to ensure continuity of care;

- Patients should have access to physician licensing, facility accreditation, and outcomes data for both;

- Medical record transfers should follow HIPAA guidelines; and

- Patients should be informed of the potential risks of combining surgical procedures with long flights and vacation activities.

—Kenneth Mays, senior director, marketing and business development, Bumrungrad Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

Patient Concerns

Hospitalists are highly focused on a patient’s quality of care; the same can be said of some overseas hospitals that attract large numbers of medical tourists. “I think the service and quality of care provided at our hospital compares favorably with the very best American hospitals,” says Kenneth Mays, senior director of hospital marketing and business development at Bumrungrad Hospital in Bangkok.

That might be so, but the growth of medical tourism also raises concerns stateside. With sleek websites making it easy for U.S. patients to schedule procedure vacations from their kitchen tables, many U.S. physician and watchdog groups worry about patient safety, privacy, liability, and continuity of care. Although most international hospitals and physicians provide outcomes data, rarely do the benchmarks compare directly with U.S. hospital quality and safety data.

“Quality comparisons are difficult, even within U.S. hospitals, as hospitals use different methodologies to collect data,” says Stephano. “Patients have to rely on JCI accreditation, surgeon experience, volume, and outcomes to decide.”

Recent studies echo the Medical Tourism Association’s claim: Increased cardiac surgery volume at Apollo Hospitals—an 8,500-bed healthcare system with 50 locations throughout India—and Narayana Hospital in Bommasandra, India, has lowered costs, with similar, or even lower, mortality rates compared with the average U.S. hospital.7,9 Other challenges like getting medical records exist even within U.S. hospitals, so emerging platforms like Google Health and Microsoft Vault, where medical records can be uploaded at the touch of a button, “will benefit patients and providers,” Dr. Li says.

The Medical Tourism Association envisions U.S.-based physicians offering follow-up care to medical tourism patients. “Currently, we encourage patients to follow up with their primary-care physician,” Stephano says.

Dr. Li says malpractice is always a concern when traveling overseas; however, he also notes the legal system in the U.S. is strong enough “to handle any medical malpractice.” That said, a patient who experiences a poor medical outcome as the result of overseas treatment might seek legal remedies, but the reality is that malpractice laws are either nonexistent or not well implemented in some destination countries. That makes malpractice claims on overseas procedures a dicey proposition.

“Patients receiving overseas treatment need to realize that they are agreeing to the jurisdiction of the destination country,” Stephano says. Other risks associated with extended travel include exposure to regional infectious diseases and poor infrastructure in the destination country, which could undermine the benefits of medical travel.

Cost-saving benefits have led some U.S. insurance companies to begin integrating overseas medical coverage. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of South Carolina offers incentives for patients willing to obtain medical care overseas at JCI-approved hospitals. BCBS then waives deductibles and copays, and several other insurers have launched similar pilot programs.10 “We will see more of these changes,” Stephano says, “to cut costs and remain competitive.”

Immediate Impact

In 2008, U.S. healthcare spending was $2.3 trillion.11 A 2005 Institute of Medicine report suggests that 30% to 40% of current U.S. healthcare expenditure is wasted.12 U.S. lawmakers, employers, hospitals, and consumers are scrambling to find ways to reduce healthcare costs and improve efficiency. Medical tourism seems to benefit a select few Americans, only lowering U.S. healthcare spending by 1% to 2%.12

Medical tourism revenue generated in destination countries currently is limited to the private sector, but that might change soon. Government funding for healthcare initiatives in such countries as India, Brazil, and Thailand is declining. Some entrepreneurial physicians and hospitals are looking to medical tourism to fill the funding gap.

Medical tourism likely will continue to grow; so too will the legal, quality, and insurance protections for patients. Efficient resource utilization might help reduce U.S. healthcare costs, and improved distribution of destination-country resources might help improve infrastructure and access to better healthcare for their own citizens.

With their leadership skills and expertise, hospitalists can play a major role in reducing healthcare costs.

However, what actual reforms healthcare legislation brings to medical tourism remain to be seen. TH

Dr. Thakkar is a hospitalist and assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

References

- Medical tourism: Consumers in search of value. Deloitte Consulting LLP website. Available at: www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/doc/content/us%5Fchs%5FMedicalTourismStudy(1).pdf. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Pafford B. The third wave—medical tourism in the 21st century. South Med J. 2009;102(8):810-813.

- Kher U. Outsourcing your heart. Available at: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=1041533291&Fmt=7&clientId=5241&RQT=309&VName=PQD. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Forgione DA, Smith PC. Medical tourism and its impact on the US health care system. J Health Care Finance. 2007;34(1):27-35.

- Lancaster J. Surgeries, side trips for “medical tourists.” The Washington Post website. Available at: www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A497432004Oct20.html. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Horowitz MD, Rosensweig JA, Jones CA. Medical tourism: Globaliz-ation of the healthcare marketplace. MedGenMed. 2007;9(4):33.

- Milstein A, Smith M. Will the surgical world become flat? Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(1):137-141.

- New AMA guidelines on medical tourism. AMA website. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/31/medicaltourism.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2010.

- Anand G. The Henry Ford of heart surgery. Wall Street Journal website. Available at: online.wsj.com/article/SB12587589288795811.html.

- Einhorn B. Outsourcing the patients. Business Week website. Available at: www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/08_12/b40760367 77780.htm. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- . Hartman M, Martin A, Nuccio O, Catlin A, et al. Health spending growth at a historic low in 2008. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1): 147-155.

- Milstein A, Smith M. America’s new refugees—seeking affordable surgery offshore. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1637-1640.

David Dupray, a 60-year-old uninsured coffee shop owner from Bar Harbor, Maine, had been having left leg pain on ambulation for four years. His cardiologist recommended stent placement for left iliac artery stenosis. The estimated bill: approximately $35,000.

Unable to afford the procedure, Dupray began searching the Web for affordable medical care overseas. His physician suggested Thailand. Within days, Dupray had an appointment with a cardiologist halfway around the world—at Bumrungrad Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. Dupray spent two days in the hotel-like hospital, had three stents placed in his leg arteries, and completed a cardiac stress test. The total bill: $18,000.

“I will never go to a hospital in the U.S.,” says Dupray, who represents a growing number of Americans searching for affordable healthcare in the global marketplace.

With rising U.S. healthcare costs and millions of Americans uninsured or underinsured, more American patients are seeking affordable, high-quality medical care abroad—known as “medical tourism.” In 2007, an estimated 750,000 Americans traveled abroad for medical care; the number is expected to increase to 6 million by the end of this year.1 On the flip side, only a little more than 400,000 nonresidents visited the U.S. in 2008 for the latest medical care.1 Globally, the medical tourism industry is estimated to grow into a $21 billion-a-year industry by 2012, with much of the growth expected from Western patients traveling overseas for affordable care.2

“As hospitalists, we have been seeing increasing numbers of patients going overseas for urgent and elective procedures, as it is a general perception the medical treatment overseas is less expensive,” says Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, director of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and SHM president-elect.

Physicians in U.S. hospitals encounter potential medical tourists all the time. Some are uninsured or underinsured. Some have insurance carriers that limit or exclude coverage for certain procedures and treatments. Even those with insurance sometimes struggle to pay deductibles, copays, and their costs after insurance has paid its part. Others are uncomfortable with the language barriers and cultural differences of U.S. hospitals and physicians.

Medical tourism also lures patients who are citizens of countries (e.g. Canada, the United Kingdom) that offer universal healthcare, Dr. Li says.3 For example, more expatriates from India and Malaysia are traveling to their native countries for medical care, as they receive affordable and quicker medical care while visiting family.

Hospitalists routinely care for patients requiring essential cardiac or orthopedic surgeries—conditions that are common in the medical tourism trade. With medical tourism growing in scope and popularity, it is essential that hospitalists are prepared to discuss with their patients the pros and cons of traveling for medical care. Hospitalists should be able to:

- Identify patients who might benefit from medical tourism;

- Know where and how to look for an accredited overseas facility; and

- Explain to patients the potential travel risks and complications, including insurance coverage and legal restrictions in destination countries.

A basic understanding of the industry and the issues can help guide your patients through medical decisions and help you care for those who have returned from a medical trip.

Big Menu, Discount Prices

Medical tourism offers a wide range of medical services performed in hospitals on nearly every continent, with a wide range of costs for certain procedures (Table 1, p. 26). Most surgeries cost 50% to 90% less than the average cost of the same surgery at a U.S. hospital. Many in the medical tourism industry say these types of savings have brought once-unaffordable surgery within the reach of most Americans, regardless of insurance status. For example, cardiac bypass surgery on average costs $144,000 in the U.S.; it costs about $8,500 in India.

The reasons the costs are so much less at overseas hospitals, as compared with U.S. costs, are many:

- Lower wages for providers;

- Less expensive medical devices and pharmaceutical products;

- Less involvement by third-party payors; and

- Lower malpractice premiums.4

For example, the annual liability insurance premium for a surgeon in India is $4,000; the average cost of a New York City surgeon’s liability insurance premium is $100,000.5

Brazil, Costa Rica, and Mexico are attractive destinations for cosmetic and dental surgeries; Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and India have emerged as hubs for cardiac and orthopedic surgeries (Table 1, above).6

The growth in medical tourism led the Joint Commission in 1999 to launch Joint Commission International (JCI), which ensures that offshore hospitals provide the highest-quality care to international patients (see “Ultra-Affordable Prices and No Decline in Quality of Care,” p. 28). JCI has accredited 120 overseas hospitals that meet these standards.

“Overseas hospitals are always keen in partnering with U.S. hospitals,” Dr. Li says. Collaborations, such as Johns Hopkins International Medical Center’s partnership with International Medical Clinic Singapore, and Partners Harvard Medical International’s affiliation with Wockhardt Hospitals in Mumbai, India, have helped facilitate the accreditation process and alleviate U.S. patient concerns.

Overseas hospitals not only offer greatly discounted rates than insurer-negotiated U.S. prices, but many of the international hospitals also report quality scores equal to or better than the average U.S. hospital’s.7

Before You Book a Trip …

How do patients find overseas facilities? It’s as easy as a click of the mouse.

“Our survey shows 75 percent of patients located offshore hospitals through the Internet,” says Renee-Marie Stephano, president of the Medical Tourism Association, a nonprofit group based in West Palm Beach, Fla., that was established in 2007 to promote education, transparency, and communication in the medical tourism community. Patients use overseas hospital websites, international medical coordinators, and medical tourism companies, such as PlanetHospital.com and MedRetreat.com, to find facilities and providers, and to coordinate medical travel.

“Medical tourism is currently unregulated,” Stephano says. “One of our goals is to certify medical tourism facilitators to create the best standard of practice.”

In 2007, the American Medical Association (AMA) published medical tourism guidelines to help healthcare entities engaged in overseas medical care.8 (Download a PDF of the guidelines at www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/31/medicaltourism.pdf.) The AMA suggests that:

- Medical care outside the U.S. should be voluntary, and patients should be informed of their legal rights and recourses before agreeing to travel outside the U.S.;

- Before traveling, local follow-up care should be arranged to ensure continuity of care;

- Patients should have access to physician licensing, facility accreditation, and outcomes data for both;

- Medical record transfers should follow HIPAA guidelines; and

- Patients should be informed of the potential risks of combining surgical procedures with long flights and vacation activities.

—Kenneth Mays, senior director, marketing and business development, Bumrungrad Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

Patient Concerns

Hospitalists are highly focused on a patient’s quality of care; the same can be said of some overseas hospitals that attract large numbers of medical tourists. “I think the service and quality of care provided at our hospital compares favorably with the very best American hospitals,” says Kenneth Mays, senior director of hospital marketing and business development at Bumrungrad Hospital in Bangkok.

That might be so, but the growth of medical tourism also raises concerns stateside. With sleek websites making it easy for U.S. patients to schedule procedure vacations from their kitchen tables, many U.S. physician and watchdog groups worry about patient safety, privacy, liability, and continuity of care. Although most international hospitals and physicians provide outcomes data, rarely do the benchmarks compare directly with U.S. hospital quality and safety data.

“Quality comparisons are difficult, even within U.S. hospitals, as hospitals use different methodologies to collect data,” says Stephano. “Patients have to rely on JCI accreditation, surgeon experience, volume, and outcomes to decide.”

Recent studies echo the Medical Tourism Association’s claim: Increased cardiac surgery volume at Apollo Hospitals—an 8,500-bed healthcare system with 50 locations throughout India—and Narayana Hospital in Bommasandra, India, has lowered costs, with similar, or even lower, mortality rates compared with the average U.S. hospital.7,9 Other challenges like getting medical records exist even within U.S. hospitals, so emerging platforms like Google Health and Microsoft Vault, where medical records can be uploaded at the touch of a button, “will benefit patients and providers,” Dr. Li says.

The Medical Tourism Association envisions U.S.-based physicians offering follow-up care to medical tourism patients. “Currently, we encourage patients to follow up with their primary-care physician,” Stephano says.

Dr. Li says malpractice is always a concern when traveling overseas; however, he also notes the legal system in the U.S. is strong enough “to handle any medical malpractice.” That said, a patient who experiences a poor medical outcome as the result of overseas treatment might seek legal remedies, but the reality is that malpractice laws are either nonexistent or not well implemented in some destination countries. That makes malpractice claims on overseas procedures a dicey proposition.

“Patients receiving overseas treatment need to realize that they are agreeing to the jurisdiction of the destination country,” Stephano says. Other risks associated with extended travel include exposure to regional infectious diseases and poor infrastructure in the destination country, which could undermine the benefits of medical travel.

Cost-saving benefits have led some U.S. insurance companies to begin integrating overseas medical coverage. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of South Carolina offers incentives for patients willing to obtain medical care overseas at JCI-approved hospitals. BCBS then waives deductibles and copays, and several other insurers have launched similar pilot programs.10 “We will see more of these changes,” Stephano says, “to cut costs and remain competitive.”

Immediate Impact

In 2008, U.S. healthcare spending was $2.3 trillion.11 A 2005 Institute of Medicine report suggests that 30% to 40% of current U.S. healthcare expenditure is wasted.12 U.S. lawmakers, employers, hospitals, and consumers are scrambling to find ways to reduce healthcare costs and improve efficiency. Medical tourism seems to benefit a select few Americans, only lowering U.S. healthcare spending by 1% to 2%.12

Medical tourism revenue generated in destination countries currently is limited to the private sector, but that might change soon. Government funding for healthcare initiatives in such countries as India, Brazil, and Thailand is declining. Some entrepreneurial physicians and hospitals are looking to medical tourism to fill the funding gap.

Medical tourism likely will continue to grow; so too will the legal, quality, and insurance protections for patients. Efficient resource utilization might help reduce U.S. healthcare costs, and improved distribution of destination-country resources might help improve infrastructure and access to better healthcare for their own citizens.

With their leadership skills and expertise, hospitalists can play a major role in reducing healthcare costs.

However, what actual reforms healthcare legislation brings to medical tourism remain to be seen. TH

Dr. Thakkar is a hospitalist and assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

References

- Medical tourism: Consumers in search of value. Deloitte Consulting LLP website. Available at: www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/doc/content/us%5Fchs%5FMedicalTourismStudy(1).pdf. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Pafford B. The third wave—medical tourism in the 21st century. South Med J. 2009;102(8):810-813.

- Kher U. Outsourcing your heart. Available at: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=1041533291&Fmt=7&clientId=5241&RQT=309&VName=PQD. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Forgione DA, Smith PC. Medical tourism and its impact on the US health care system. J Health Care Finance. 2007;34(1):27-35.

- Lancaster J. Surgeries, side trips for “medical tourists.” The Washington Post website. Available at: www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A497432004Oct20.html. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Horowitz MD, Rosensweig JA, Jones CA. Medical tourism: Globaliz-ation of the healthcare marketplace. MedGenMed. 2007;9(4):33.

- Milstein A, Smith M. Will the surgical world become flat? Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(1):137-141.

- New AMA guidelines on medical tourism. AMA website. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/31/medicaltourism.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2010.

- Anand G. The Henry Ford of heart surgery. Wall Street Journal website. Available at: online.wsj.com/article/SB12587589288795811.html.

- Einhorn B. Outsourcing the patients. Business Week website. Available at: www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/08_12/b40760367 77780.htm. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- . Hartman M, Martin A, Nuccio O, Catlin A, et al. Health spending growth at a historic low in 2008. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1): 147-155.

- Milstein A, Smith M. America’s new refugees—seeking affordable surgery offshore. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1637-1640.

Endangered Species?

The 1961 classic “The Ecology of Medical Care,” published in the New England Journal of Medicine, mapped out the broad features of the American healthcare landscape.1 For every 1,000 adult, the study suggested, 750 reported an illness, 250 consulted a doctor, and nine were admitted to a hospital in any given month. The subsequent arrival of Medicare and Medicaid fundamentally changed the U.S. healthcare system. And yet an updated version of the study, released in 2001, yielded surprisingly similar numbers, with 800 residents experiencing symptoms, 217 visiting a physician’s office, and eight being hospitalized in an average month.2

“It helps kind of put in perspective where the bulk of care really occurs,” says Ann O’Malley, MD, a senior researcher at the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Studying Health System Change. “It’s in outpatient provider offices, mostly primary-care provider offices.”

Dr. O’Malley and a host of other observers, however, are warning that the keystone members of this healthcare ecosystem are in serious trouble. As organizations such as SHM have likewise made clear, the accelerating shortage of general internists, family practitioners, and other PCPs has created sizable cracks in the supports of the entire healthcare infrastructure.

How big are the cracks? The number of medical school students pursuing a primary-care career has dropped by more than half since 1997, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians. And with the number of medical students entering the field unable to keep up with attrition, the remaining doctors are facing increasingly difficult working conditions. “Overloaded primary-care practices, whose doctors are aptly compared to hamsters on a treadmill, struggle to provide prompt access and high-quality care,” asserted a 2009 op-ed in the New England Journal of Medicine.3 The result: a vicious circle of decline leading to an anticipated shortfall of roughly 21,000 PCPs by 2015, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Many primary-care providers had already stopped taking new patients when June’s Medicare reimbursement rate fiasco allowed the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula’s mandated 21.2 percent rate cut to temporarily go into effect. Legislators eventually plugged the hole, but not before a new round of jitters seized the nation’s physicians, and reports proliferated throughout the summer about Medicare beneficiaries being unable to find a doctor willing to see them. The recession hasn’t helped, with more privately insured patients waiting longer to see their doctors to avoid copays, and with hospital emergency departments becoming de facto primary-care centers for those patients who have waited too long or have no other alternatives.

Uneven Challenges

Not only is there an acute shortage of primary-care physicians, Dr. O’Malley says, but there is also a distinctly uneven distribution throughout the country. For hospitalists, she says, the implications could be profound. “Hospitalists are increasingly going to be evaluated around issues such as avoiding hospital readmissions and [reducing] length of stay,” she says, “and if they want to improve both of those things, one of the keys is improving chronic care management in the outpatient setting, and improving follow-up post discharge.”

Both metrics will require the involvement of outpatient care providers, underscoring the importance of good communication and mutual respect. Despite the longstanding support of hospitalists for their primary-care counterparts, however, leaders are still being forced to address the perception that HM is somehow bad for what ails PCPs.

In a recent online article posted on the Becker’s Hospital Review website, SHM President Jeff Wiese, MD, SFHM, responded to one such criticism: that hospitalists make primary care less attractive for physicians. Hospitalists are not to blame for the decrease in interest, he asserted, but are actually complementary to the PCP role. And with millions more Americans about to be newly insured, that complementary relationship will be even more important. “It’s a tremendous waste of resources to use a primary-care provider for [a hospital visit]. We need to move into proactive mode, not reactive mode,” Dr. Wiese said. “More PCPs are going to need even more time in the clinic to handle the increased number of patients, and you lose the luxury to run back and forth between the clinic and the hospital. For those that can develop a trusting relationship with a hospitalist, you can work together to see more patients and provide more care.”

So what’s the real root of the problem? Money. According to recent surveys, PCPs earn about half the salary of dermatologists and an even smaller fraction of an average cardiologist’s pay. With medical school debt routinely reaching $200,000, Dr. O’Malley and other analysts say, many doctors simply can’t afford to go into primary care.

“It all comes down to payment, basically,” she says. “At present, our payment system for physician services and for medical procedures is quite skewed. It overcompensates for certain types of diagnostics and procedures, and it undercompensates for the more cognitive type of care that primary-care providers provide.”

The Road Ahead

Fortunately, some relief is trickling in. One measure strongly supported by SHM and included in the Affordable Care Act is a 10% Medicare reimbursement bonus for primary care delivered by qualified doctors, slated to begin next year. In June, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius announced a separate, $250 million initiative to boost the primary-care workforce. The money would help train PCPs by creating more residency slots, and offer new support for physician assistants, nurses, and nurse practitioners. Among the measures included in last year’s stimulus package, an expansion of the National Health Service Corps will provide more debt-relief opportunities for PCPs. And in mid-September, HHS tapped stimulus funds to award another $50.3 million for primary care training programs and loan repayment.

The Obama administration has claimed its combined actions “will support the training and development of more than 16,000 new primary-care providers over the next five years,” according to a June 16 HHS press release.

Observers say those measures alone are unlikely to be enough to stem the tide, however. “It’s definitely a step in the right direction,” Dr. O’Malley says of the Medicare bonus. “I don’t think it’s going to solve the primary-care workforce issue, because a 10% bonus, given how low primary-care physician salaries are compared to their specialist counterparts, is not going to be that much of an increase. Among the physicians that I’ve talked to and other healthcare providers, few feel that that’s sufficient enough to really encourage a lot of people to pursue primary care.”

Several other efforts now underway might help:

- Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center unveiled a new Family Medicine Accelerated Track program, which will allow primary-care medical students to complete a degree in three years. Certain students will receive a one-year scholarship, meaning that overall debt for some could be half that of the standard four-year program.

- Reid Hospital and Health Care Services in Richmond, Ind., successfully reversed a downward trend in primary-care referrals by forming its own nonprofit subsidiary corporation, Reid Physician Associates. The nonprofit will include about 50 employed outpatient providers by year’s end to complement the 233-bed hospital’s inpatient staff.

- Danville, Pa.-based Geisinger Health System has begun paying the salaries of extra nurses for both in-network and independent primary-care practices. The nurses manage patients’ chronic conditions, ensure that they are following prescribed treatments, and communicate with hospitalists and other providers about transitions of care. Although still in its early stages, the experiment suggests the nurses are helping to spot problems, prevent unnecessary hospitalizations, and save money.

The Geisinger experiment is among the first steps toward a patient-centered medical home model of care. An eventual Medicare-led expansion of such medical homes and accountable-care organizations, now in the early experimental stages, could provide even more direct support to PCPs. To be successful, though, Dr. O’Malley says the models will need to focus on paying providers fairly for the value they bring to the system. “Obviously, payment reform is what we need if we’re ever going to develop a sustainable primary-care workforce in this country,” she says. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

References

- White KL, Williams TF, Greenberg BG. The ecology of medical care. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:885-992.

- Green LA, Fryer GE Jr., Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):2021-2025.

- Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2693-2696.

The 1961 classic “The Ecology of Medical Care,” published in the New England Journal of Medicine, mapped out the broad features of the American healthcare landscape.1 For every 1,000 adult, the study suggested, 750 reported an illness, 250 consulted a doctor, and nine were admitted to a hospital in any given month. The subsequent arrival of Medicare and Medicaid fundamentally changed the U.S. healthcare system. And yet an updated version of the study, released in 2001, yielded surprisingly similar numbers, with 800 residents experiencing symptoms, 217 visiting a physician’s office, and eight being hospitalized in an average month.2

“It helps kind of put in perspective where the bulk of care really occurs,” says Ann O’Malley, MD, a senior researcher at the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Studying Health System Change. “It’s in outpatient provider offices, mostly primary-care provider offices.”

Dr. O’Malley and a host of other observers, however, are warning that the keystone members of this healthcare ecosystem are in serious trouble. As organizations such as SHM have likewise made clear, the accelerating shortage of general internists, family practitioners, and other PCPs has created sizable cracks in the supports of the entire healthcare infrastructure.

How big are the cracks? The number of medical school students pursuing a primary-care career has dropped by more than half since 1997, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians. And with the number of medical students entering the field unable to keep up with attrition, the remaining doctors are facing increasingly difficult working conditions. “Overloaded primary-care practices, whose doctors are aptly compared to hamsters on a treadmill, struggle to provide prompt access and high-quality care,” asserted a 2009 op-ed in the New England Journal of Medicine.3 The result: a vicious circle of decline leading to an anticipated shortfall of roughly 21,000 PCPs by 2015, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Many primary-care providers had already stopped taking new patients when June’s Medicare reimbursement rate fiasco allowed the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula’s mandated 21.2 percent rate cut to temporarily go into effect. Legislators eventually plugged the hole, but not before a new round of jitters seized the nation’s physicians, and reports proliferated throughout the summer about Medicare beneficiaries being unable to find a doctor willing to see them. The recession hasn’t helped, with more privately insured patients waiting longer to see their doctors to avoid copays, and with hospital emergency departments becoming de facto primary-care centers for those patients who have waited too long or have no other alternatives.

Uneven Challenges

Not only is there an acute shortage of primary-care physicians, Dr. O’Malley says, but there is also a distinctly uneven distribution throughout the country. For hospitalists, she says, the implications could be profound. “Hospitalists are increasingly going to be evaluated around issues such as avoiding hospital readmissions and [reducing] length of stay,” she says, “and if they want to improve both of those things, one of the keys is improving chronic care management in the outpatient setting, and improving follow-up post discharge.”

Both metrics will require the involvement of outpatient care providers, underscoring the importance of good communication and mutual respect. Despite the longstanding support of hospitalists for their primary-care counterparts, however, leaders are still being forced to address the perception that HM is somehow bad for what ails PCPs.

In a recent online article posted on the Becker’s Hospital Review website, SHM President Jeff Wiese, MD, SFHM, responded to one such criticism: that hospitalists make primary care less attractive for physicians. Hospitalists are not to blame for the decrease in interest, he asserted, but are actually complementary to the PCP role. And with millions more Americans about to be newly insured, that complementary relationship will be even more important. “It’s a tremendous waste of resources to use a primary-care provider for [a hospital visit]. We need to move into proactive mode, not reactive mode,” Dr. Wiese said. “More PCPs are going to need even more time in the clinic to handle the increased number of patients, and you lose the luxury to run back and forth between the clinic and the hospital. For those that can develop a trusting relationship with a hospitalist, you can work together to see more patients and provide more care.”

So what’s the real root of the problem? Money. According to recent surveys, PCPs earn about half the salary of dermatologists and an even smaller fraction of an average cardiologist’s pay. With medical school debt routinely reaching $200,000, Dr. O’Malley and other analysts say, many doctors simply can’t afford to go into primary care.

“It all comes down to payment, basically,” she says. “At present, our payment system for physician services and for medical procedures is quite skewed. It overcompensates for certain types of diagnostics and procedures, and it undercompensates for the more cognitive type of care that primary-care providers provide.”

The Road Ahead

Fortunately, some relief is trickling in. One measure strongly supported by SHM and included in the Affordable Care Act is a 10% Medicare reimbursement bonus for primary care delivered by qualified doctors, slated to begin next year. In June, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius announced a separate, $250 million initiative to boost the primary-care workforce. The money would help train PCPs by creating more residency slots, and offer new support for physician assistants, nurses, and nurse practitioners. Among the measures included in last year’s stimulus package, an expansion of the National Health Service Corps will provide more debt-relief opportunities for PCPs. And in mid-September, HHS tapped stimulus funds to award another $50.3 million for primary care training programs and loan repayment.

The Obama administration has claimed its combined actions “will support the training and development of more than 16,000 new primary-care providers over the next five years,” according to a June 16 HHS press release.

Observers say those measures alone are unlikely to be enough to stem the tide, however. “It’s definitely a step in the right direction,” Dr. O’Malley says of the Medicare bonus. “I don’t think it’s going to solve the primary-care workforce issue, because a 10% bonus, given how low primary-care physician salaries are compared to their specialist counterparts, is not going to be that much of an increase. Among the physicians that I’ve talked to and other healthcare providers, few feel that that’s sufficient enough to really encourage a lot of people to pursue primary care.”

Several other efforts now underway might help:

- Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center unveiled a new Family Medicine Accelerated Track program, which will allow primary-care medical students to complete a degree in three years. Certain students will receive a one-year scholarship, meaning that overall debt for some could be half that of the standard four-year program.

- Reid Hospital and Health Care Services in Richmond, Ind., successfully reversed a downward trend in primary-care referrals by forming its own nonprofit subsidiary corporation, Reid Physician Associates. The nonprofit will include about 50 employed outpatient providers by year’s end to complement the 233-bed hospital’s inpatient staff.

- Danville, Pa.-based Geisinger Health System has begun paying the salaries of extra nurses for both in-network and independent primary-care practices. The nurses manage patients’ chronic conditions, ensure that they are following prescribed treatments, and communicate with hospitalists and other providers about transitions of care. Although still in its early stages, the experiment suggests the nurses are helping to spot problems, prevent unnecessary hospitalizations, and save money.

The Geisinger experiment is among the first steps toward a patient-centered medical home model of care. An eventual Medicare-led expansion of such medical homes and accountable-care organizations, now in the early experimental stages, could provide even more direct support to PCPs. To be successful, though, Dr. O’Malley says the models will need to focus on paying providers fairly for the value they bring to the system. “Obviously, payment reform is what we need if we’re ever going to develop a sustainable primary-care workforce in this country,” she says. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

References

- White KL, Williams TF, Greenberg BG. The ecology of medical care. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:885-992.

- Green LA, Fryer GE Jr., Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):2021-2025.

- Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2693-2696.

The 1961 classic “The Ecology of Medical Care,” published in the New England Journal of Medicine, mapped out the broad features of the American healthcare landscape.1 For every 1,000 adult, the study suggested, 750 reported an illness, 250 consulted a doctor, and nine were admitted to a hospital in any given month. The subsequent arrival of Medicare and Medicaid fundamentally changed the U.S. healthcare system. And yet an updated version of the study, released in 2001, yielded surprisingly similar numbers, with 800 residents experiencing symptoms, 217 visiting a physician’s office, and eight being hospitalized in an average month.2

“It helps kind of put in perspective where the bulk of care really occurs,” says Ann O’Malley, MD, a senior researcher at the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Studying Health System Change. “It’s in outpatient provider offices, mostly primary-care provider offices.”

Dr. O’Malley and a host of other observers, however, are warning that the keystone members of this healthcare ecosystem are in serious trouble. As organizations such as SHM have likewise made clear, the accelerating shortage of general internists, family practitioners, and other PCPs has created sizable cracks in the supports of the entire healthcare infrastructure.

How big are the cracks? The number of medical school students pursuing a primary-care career has dropped by more than half since 1997, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians. And with the number of medical students entering the field unable to keep up with attrition, the remaining doctors are facing increasingly difficult working conditions. “Overloaded primary-care practices, whose doctors are aptly compared to hamsters on a treadmill, struggle to provide prompt access and high-quality care,” asserted a 2009 op-ed in the New England Journal of Medicine.3 The result: a vicious circle of decline leading to an anticipated shortfall of roughly 21,000 PCPs by 2015, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Many primary-care providers had already stopped taking new patients when June’s Medicare reimbursement rate fiasco allowed the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula’s mandated 21.2 percent rate cut to temporarily go into effect. Legislators eventually plugged the hole, but not before a new round of jitters seized the nation’s physicians, and reports proliferated throughout the summer about Medicare beneficiaries being unable to find a doctor willing to see them. The recession hasn’t helped, with more privately insured patients waiting longer to see their doctors to avoid copays, and with hospital emergency departments becoming de facto primary-care centers for those patients who have waited too long or have no other alternatives.

Uneven Challenges

Not only is there an acute shortage of primary-care physicians, Dr. O’Malley says, but there is also a distinctly uneven distribution throughout the country. For hospitalists, she says, the implications could be profound. “Hospitalists are increasingly going to be evaluated around issues such as avoiding hospital readmissions and [reducing] length of stay,” she says, “and if they want to improve both of those things, one of the keys is improving chronic care management in the outpatient setting, and improving follow-up post discharge.”

Both metrics will require the involvement of outpatient care providers, underscoring the importance of good communication and mutual respect. Despite the longstanding support of hospitalists for their primary-care counterparts, however, leaders are still being forced to address the perception that HM is somehow bad for what ails PCPs.

In a recent online article posted on the Becker’s Hospital Review website, SHM President Jeff Wiese, MD, SFHM, responded to one such criticism: that hospitalists make primary care less attractive for physicians. Hospitalists are not to blame for the decrease in interest, he asserted, but are actually complementary to the PCP role. And with millions more Americans about to be newly insured, that complementary relationship will be even more important. “It’s a tremendous waste of resources to use a primary-care provider for [a hospital visit]. We need to move into proactive mode, not reactive mode,” Dr. Wiese said. “More PCPs are going to need even more time in the clinic to handle the increased number of patients, and you lose the luxury to run back and forth between the clinic and the hospital. For those that can develop a trusting relationship with a hospitalist, you can work together to see more patients and provide more care.”

So what’s the real root of the problem? Money. According to recent surveys, PCPs earn about half the salary of dermatologists and an even smaller fraction of an average cardiologist’s pay. With medical school debt routinely reaching $200,000, Dr. O’Malley and other analysts say, many doctors simply can’t afford to go into primary care.

“It all comes down to payment, basically,” she says. “At present, our payment system for physician services and for medical procedures is quite skewed. It overcompensates for certain types of diagnostics and procedures, and it undercompensates for the more cognitive type of care that primary-care providers provide.”

The Road Ahead

Fortunately, some relief is trickling in. One measure strongly supported by SHM and included in the Affordable Care Act is a 10% Medicare reimbursement bonus for primary care delivered by qualified doctors, slated to begin next year. In June, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius announced a separate, $250 million initiative to boost the primary-care workforce. The money would help train PCPs by creating more residency slots, and offer new support for physician assistants, nurses, and nurse practitioners. Among the measures included in last year’s stimulus package, an expansion of the National Health Service Corps will provide more debt-relief opportunities for PCPs. And in mid-September, HHS tapped stimulus funds to award another $50.3 million for primary care training programs and loan repayment.

The Obama administration has claimed its combined actions “will support the training and development of more than 16,000 new primary-care providers over the next five years,” according to a June 16 HHS press release.

Observers say those measures alone are unlikely to be enough to stem the tide, however. “It’s definitely a step in the right direction,” Dr. O’Malley says of the Medicare bonus. “I don’t think it’s going to solve the primary-care workforce issue, because a 10% bonus, given how low primary-care physician salaries are compared to their specialist counterparts, is not going to be that much of an increase. Among the physicians that I’ve talked to and other healthcare providers, few feel that that’s sufficient enough to really encourage a lot of people to pursue primary care.”

Several other efforts now underway might help:

- Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center unveiled a new Family Medicine Accelerated Track program, which will allow primary-care medical students to complete a degree in three years. Certain students will receive a one-year scholarship, meaning that overall debt for some could be half that of the standard four-year program.

- Reid Hospital and Health Care Services in Richmond, Ind., successfully reversed a downward trend in primary-care referrals by forming its own nonprofit subsidiary corporation, Reid Physician Associates. The nonprofit will include about 50 employed outpatient providers by year’s end to complement the 233-bed hospital’s inpatient staff.

- Danville, Pa.-based Geisinger Health System has begun paying the salaries of extra nurses for both in-network and independent primary-care practices. The nurses manage patients’ chronic conditions, ensure that they are following prescribed treatments, and communicate with hospitalists and other providers about transitions of care. Although still in its early stages, the experiment suggests the nurses are helping to spot problems, prevent unnecessary hospitalizations, and save money.

The Geisinger experiment is among the first steps toward a patient-centered medical home model of care. An eventual Medicare-led expansion of such medical homes and accountable-care organizations, now in the early experimental stages, could provide even more direct support to PCPs. To be successful, though, Dr. O’Malley says the models will need to focus on paying providers fairly for the value they bring to the system. “Obviously, payment reform is what we need if we’re ever going to develop a sustainable primary-care workforce in this country,” she says. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

References

- White KL, Williams TF, Greenberg BG. The ecology of medical care. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:885-992.

- Green LA, Fryer GE Jr., Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):2021-2025.

- Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2693-2696.

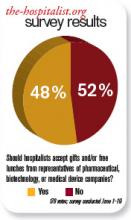

Should hospitalists accept gifts from pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotech companies?

Recent discussions on conflicts of interest in medical publications underscore the significance of the important yet fragile relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare professionals. Among these is an examination of how academic departments can maintain a relationship with the industry.1 This study suggests that if appropriate boundaries are established between industry and academia, it is possible to collaborate. However, part of the policy in this investigation included “elimination of industry-supplied meals, gifts, and favors.”2

The Institute of Medicine’s “Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice” included groundbreaking recommendations.3 Among them was a call for professionals to adopt a policy that prohibits “the acceptance of items of material value from pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology companies, except in specified situations.”3

Our nation has been embroiled in a healthcare debate. Questions of right versus privilege, access versus affordability, and, of course, the perpetual political overlay have monopolized most of the discourse. Some contend that healthcare reform will redefine the current relationship between pharma and physicians . . . and not a moment too soon.

Lest there be ambiguity, though, the medical profession remains a noble vocation. This notwithstanding, until 2002, physicians freely participated in golf outings, received athletic tickets, and dined at five-star restaurants. But after the pharmaceutical industry smartly adopted voluntary guidelines that restrict gifting to doctors, we are left with drug samples and, of course, the “free lunch.” Certainly, pharma can claim it has made significant contributions to furthering medical education and research. Many could argue the tangible negative effects that would follow if the funding suddenly were absent.

But let’s not kid ourselves: There is a good reason the pharmaceutical industry spends more than $12 billion per year on marketing to doctors.4 In 2006, Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) said, “It is obvious that drug companies provide these free lunches so their sales reps can get the doctor’s ear and influence the prescribing practices.”2 Most doctors would never admit any such influence. It would be, however, disingenuous for any practicing physician to say there is none.

A randomized trial conducted by Adair et al concluded the “access to drug samples in clinic influences resident prescribing decisions. This could affect resident education and increase drug costs for patients.”5 An earlier study by Chew et al concluded “the availability of drug samples led physicians to dispense and subsequently prescribe drugs that differ from their preferred drug choice. Physicians most often report using drug samples to avoid cost to the patient.”6

Sure, local culture drives some prescribing practice, but one must be mindful of the reality that the pharmaceutical industry has significant influence. Plus, free drug samples help patients in the short term. Once the samples are gone, an expensive prescription for that new drug will follow. It’s another win for the industry and another loss for the patient and the healthcare system.

Many studies have shown that gifting exerts influence, even if doctors are unwilling to admit it. But patients and doctors alike would like to state with clarity of conscience that the medication prescribed is only based on clinical evidence, not influence. TH

Dr. Pyke is a hospitalist at Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Systems in Mountain Top, Pa.

References

- Dubovsky SL, Kaye DL, Pristach CA, DelRegno P, Pessar L, Stiles K. Can academic departments maintain industry relationships while promoting physician professionalism? Acad Med. 2010;85(1):68-73.

- Salganik MW, Hopkins JS, Rockoff JD. Medical salesmen prescribe lunches. Catering trade feeds on rep-doctor meals. The Baltimore Sun. July 29, 2006.

- Institute of Medicine Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education and Practice Full Recommendations. 4-28-09.

- Wolfe SM. Why do American drug companies spend more than $12 billion a year pushing drugs? Is it education or promotion? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;11(10):637-639.

- Adair RF, Holmgren LR. Do drug samples influence resident prescribing behavior? A randomized trial. Am J Med. 2005;118(8):881-884.

- Chew LD, O’Young TS, Hazlet TK, Bradley KA, Maynard C, Lessler DS. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians’ behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(7):478-483.

Recent discussions on conflicts of interest in medical publications underscore the significance of the important yet fragile relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare professionals. Among these is an examination of how academic departments can maintain a relationship with the industry.1 This study suggests that if appropriate boundaries are established between industry and academia, it is possible to collaborate. However, part of the policy in this investigation included “elimination of industry-supplied meals, gifts, and favors.”2

The Institute of Medicine’s “Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice” included groundbreaking recommendations.3 Among them was a call for professionals to adopt a policy that prohibits “the acceptance of items of material value from pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology companies, except in specified situations.”3

Our nation has been embroiled in a healthcare debate. Questions of right versus privilege, access versus affordability, and, of course, the perpetual political overlay have monopolized most of the discourse. Some contend that healthcare reform will redefine the current relationship between pharma and physicians . . . and not a moment too soon.

Lest there be ambiguity, though, the medical profession remains a noble vocation. This notwithstanding, until 2002, physicians freely participated in golf outings, received athletic tickets, and dined at five-star restaurants. But after the pharmaceutical industry smartly adopted voluntary guidelines that restrict gifting to doctors, we are left with drug samples and, of course, the “free lunch.” Certainly, pharma can claim it has made significant contributions to furthering medical education and research. Many could argue the tangible negative effects that would follow if the funding suddenly were absent.

But let’s not kid ourselves: There is a good reason the pharmaceutical industry spends more than $12 billion per year on marketing to doctors.4 In 2006, Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) said, “It is obvious that drug companies provide these free lunches so their sales reps can get the doctor’s ear and influence the prescribing practices.”2 Most doctors would never admit any such influence. It would be, however, disingenuous for any practicing physician to say there is none.

A randomized trial conducted by Adair et al concluded the “access to drug samples in clinic influences resident prescribing decisions. This could affect resident education and increase drug costs for patients.”5 An earlier study by Chew et al concluded “the availability of drug samples led physicians to dispense and subsequently prescribe drugs that differ from their preferred drug choice. Physicians most often report using drug samples to avoid cost to the patient.”6

Sure, local culture drives some prescribing practice, but one must be mindful of the reality that the pharmaceutical industry has significant influence. Plus, free drug samples help patients in the short term. Once the samples are gone, an expensive prescription for that new drug will follow. It’s another win for the industry and another loss for the patient and the healthcare system.

Many studies have shown that gifting exerts influence, even if doctors are unwilling to admit it. But patients and doctors alike would like to state with clarity of conscience that the medication prescribed is only based on clinical evidence, not influence. TH

Dr. Pyke is a hospitalist at Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Systems in Mountain Top, Pa.

References

- Dubovsky SL, Kaye DL, Pristach CA, DelRegno P, Pessar L, Stiles K. Can academic departments maintain industry relationships while promoting physician professionalism? Acad Med. 2010;85(1):68-73.

- Salganik MW, Hopkins JS, Rockoff JD. Medical salesmen prescribe lunches. Catering trade feeds on rep-doctor meals. The Baltimore Sun. July 29, 2006.

- Institute of Medicine Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education and Practice Full Recommendations. 4-28-09.

- Wolfe SM. Why do American drug companies spend more than $12 billion a year pushing drugs? Is it education or promotion? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;11(10):637-639.

- Adair RF, Holmgren LR. Do drug samples influence resident prescribing behavior? A randomized trial. Am J Med. 2005;118(8):881-884.

- Chew LD, O’Young TS, Hazlet TK, Bradley KA, Maynard C, Lessler DS. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians’ behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(7):478-483.