User login

RFVTA system offers alternative to myomectomy

Uterine myomas cause heavy menstrual bleeding and other clinically significant symptoms in 35%-50% of affected women and have been shown to be the leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States among women aged 35-54 years.

Research has shown that a significant number of women who undergo hysterectomy for treatment of fibroids later regret the loss of their uterus and have other concerns and complications. Other options for therapy include various pharmacologic treatments, a progestin-releasing intrauterine device, uterine artery embolization, endometrial ablation, MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery, and myomectomy performed laparoscopically, robotically, or hysteroscopically.

Myomectomy seems largely to preserve fertility, but rates of recurrence and additional procedures for bleeding and myoma symptoms are still high – upward of 30% in some studies. Overall, we need other more efficacious and minimally invasive options.

Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation (RFVTA) achieved through the Acessa System (Halt Medical) has been the newest addition to our armamentarium for treatment of symptomatic fibroids. It is suitable for every type of fibroid except for type 0 pedunculated intracavitary fibroids and type 7 pedunculated subserosal fibroids, which is significant because deep intramural fibroids have been difficult to target and treat by other methods.

Three-year outcome data show sustained improvements in fibroid symptoms and quality of life, with an incidence of recurrences and additional procedures – approximately 11% – that appears to be substantially lower than for other uterine-sparing fibroid treatments. In addition, while the technology is not indicated for women seeking future childbearing, successful pregnancies are being reported, suggesting that full-term pregnancies – and vaginal delivery in some cases – may be possible after RFVTA.

The principles

Radiofrequency ablation has been used for years in the treatment of liver and kidney tumors. The basic concept is that volumetric thermal ablation results in coagulative necrosis.

The Acessa System, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in late 2012, was designed to treat fibroids, which have much firmer tissue than the tissues being targeted in other radiofrequency ablation procedures. It uses a specially designed intrauterine ultrasound probe and radiofrequency probe, and it combines three fundamental gynecologic skills: Laparoscopy using two trocars and requiring no special suturing skills; ultrasound using a laparoscopic ultrasound probe to scan and manipulate; and probe placement under laparoscopic ultrasound guidance.

Specifically, the system allows for percutaneous, laparoscopic ultrasound–guided radiofrequency ablation of fibroids with a disposable 3.4-mm handpiece coupled to a dual-function radiofrequency generator. The handpiece contains a retractable array of electrodes, so that the fibroid may be ablated with one electrode or with the deployed electrode array.

The generator controls and monitors the ablation with real-time feedback from thermocouples. It monitors and displays the temperature at each needle tip, the average temperature of the array, and the return temperatures on two dispersive electrode pads that are placed on the anterior thighs. The electrode pads are designed to reduce the incidence of pad burns, which are a complication with other radiofrequency ablation devices. The system will automatically stop treatment if either of the pad thermocouples registers a skin temperature greater than 40° C (JSLS. 2014 Apr-Jun;18[2]:182-90).

The outcomes

Laparoscopic ultrasound–guided RFVTA has been studied in five prospective trials, including one multicenter international trial of 135 premenopausal women – the pivotal trial for FDA clearance – in which 104 women were followed for 3 years and found to have prolonged symptom relief and improved quality of life.

At baseline, the women had symptomatic uterine myomas and moderate to severe heavy menstrual bleeding measured by alkaline hematin analysis of returned sanitary products. Their mean symptom severity scores on the Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (UFS-QOL) decreased significantly from baseline to 3 months and changed little after that, for a total change of –32.6 over the study period.

The cumulative repeat intervention rate at 3 years was 11%, with 14 of the 135 participants having repeat interventions to treat bleeding and myoma symptoms. Seven of these women were found to have adenomyosis (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 Sep-Oct;21[5]:767-74).

The surprisingly low reintervention rates may stem from the benefits of direct contact imaging of the uterus. A comparison of images from the pivotal trial has shown that intraoperative ultrasound detected more than twice as many fibroids as did preoperative transvaginal ultrasound, and about one-third more than preoperative MRIs (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Nov-Dec;20[6]:770-4).

Interestingly, four women became pregnant over the study’s 3-year follow-up, despite the inclusion requirement that women desire uterine conservation but not future childbearing.

We have followed reproductive outcomes in women after RFVTA of symptomatic fibroids in other studies as well. In our most recent analysis, presented in November at the 2015 American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists Global Congress, we identified 10 pregnancies among participants of the five prospective trials.

Of 232 women enrolled in premarket RFVTA studies – trials in which completing childbearing and continuing contraception were requirements – six conceived at 3.5-15 months post ablation. The number of myomas treated ranged from one to seven and included multiple types and dimensions. Five of these six women delivered full-term healthy babies – one by vaginal delivery and four by cesarean section. The sixth patient had a spontaneous abortion in the first trimester.

Of 43 women who participated in two randomized clinical trials undertaken after FDA clearance, four conceived at 4-23.5 months post ablation. Three of these women had uneventful, full-term pregnancies with vaginal births. The fourth had a cesarean section at 38 weeks.

Considering the theoretical advantages of the Acessa procedure – that it is less damaging to healthy myometrium – and the outcomes reported thus far, it appears likely that Acessa will be preferable to myomectomy. Early results from an ongoing 5-year German study that randomized 50 women to RFVTA or laparoscopic myomectomy show that RFVTA resulted in the treatment of more fibroids and involved a significantly shorter hospital stay and post-operative recovery (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014 Jun;125[3]:261-5).

The technique

The patient is pretreated with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent and prophylactic antibiotic. She is placed in a supine position with arms tucked, and a single-toothed tenaculum is placed on the cervix from 12 to 6 o’clock, without any instrument for manipulation of the uterus. The system’s dispersive electrode pads are placed symmetrically just above the patella on the anterior thighs; asymmetrical placement could potentially increase the risk of a pad burn.

Two standard laparoscopic ports are placed. A 5-mm trocar for the camera and video laparoscope is placed through the umbilicus or at a supraumbilical or left upper–quadrant level, depending on the patient’s anatomy, her surgical history, and the size of the uterus. A thorough visual inspection of the abdomen should be performed to look for unsuspected findings.

A 10-mm trocar is then placed at the level of the top of the fundus for the intra-abdominal ultrasound probe. Laparoscopic ultrasound is used to survey the entire uterus, map the fibroids, and plan an approach. Once the fibroid to be treated first is identified, the ability to stabilize the uterus accordingly is assessed, and the dimensions of the fibroid are taken. The dimensions will be used by the surgeon with a volume algorithm to calculate the length of ablation time based on the size of the fibroid and electrode deployment.

Under ultrasound guidance, the Acessa radiofrequency ablation handpiece is inserted percutaneously at 12, 3, 6, or 9 o’clock relative to the ultrasound trocar, based on the location of the target fibroid. The uterus must be stabilized, with the handpiece and ultrasound probe parallel and in plane. The handpiece is then inserted 1 cm into the target fibroid through the uterine serosal surface, utilizing a combination of laparoscopic and ultrasound views. Care must be taken to use gentle rotation and minimal downward pressure as the tip of the handpiece is quite sharp.

The location of the tip is confirmed by laparoscopic ultrasound, and the 7-needle electrode array can then be deployed to the ablation site. All three dimensions of the fibroid should be viewed for placement and deployment of the electrodes. Care is taken to avoid large blood vessels and ensure that the electrodes are confined within the fibroid and within the uterus.

Radiofrequency ablation is carried out with a low-voltage, high-frequency alternating current. The radiofrequency waves heat the tissue to an average temperature of 95° C for a length of time determined by a treatment algorithm. The wattage automatically adjusts to maintain the treatment temperature for the calculated duration of ablation.

Small fibroids can be treated in a manual mode without deployment of the electrode array at a current output of 15 W.

At the conclusion of the ablation, the electrodes are withdrawn into the handpiece, the generator is changed to coagulation mode, and the handpiece is slowly withdrawn under ultrasound visualization. The tract is simultaneously coagulated. A bit of additional coagulation is facilitated by pausing at the serosal surface.

Additional fibroids can be ablated through another insertion of the handpiece, either through the same tract or through a new tract.

Larger fibroids may require multiple ablations. The maximum size of ablation is about 5 cm, so it is important to plan the treatment of larger fibroids. This can be accomplished by carefully scanning large fibroids and visualizing the number of overlapping ablations needed to treat the entire volume. I ask my assistant to record the size and location of each ablation; I find this helpful both for organizing the treatment of large fibroids and for dictating the operative report.

It is important to appreciate that treatment of one area can make it difficult to visualize nearby fibroids with ultrasound. The effect dissipates in about 30-45 minutes. It is one reason why having a fibroid map prior to treatment is so important.

Once all fibroids are treated, a final inspection is performed. We usually use a suction irrigator to clean out whatever small amounts of blood are present, and the laparoscopic and port sites are closed in standard fashion.

Patients are seen 1 week postoperatively and are instructed to call in cases of pain, fever, bleeding, or chills. Most patients require only NSAIDs for pain relief and return to work in 2-7 days.

Many patients experience a slightly heavier than normal first menses after treatment. Pelvic rest is recommended for 3 weeks as a precaution, and avoidance of intrauterine procedures is advised because the uterus will be soft and thus may be easily perforated. Patients who have had type 1, type 2, or type 2-5 fibroids ablated may experience drainage for several weeks as the fibroid tissue is reabsorbed.

Dr. Berman is interim chairman of Wayne State University’s department of obstetrics and gynecology and interim specialist-in-chief for obstetrics and gynecology at the Detroit Medical Center. He was a principal investigator of the 3-year outcome study of Acessa sponsored by Halt Medical. He is a consultant for Halt Medical and directs physician training in the use of Acessa.

Uterine myomas cause heavy menstrual bleeding and other clinically significant symptoms in 35%-50% of affected women and have been shown to be the leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States among women aged 35-54 years.

Research has shown that a significant number of women who undergo hysterectomy for treatment of fibroids later regret the loss of their uterus and have other concerns and complications. Other options for therapy include various pharmacologic treatments, a progestin-releasing intrauterine device, uterine artery embolization, endometrial ablation, MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery, and myomectomy performed laparoscopically, robotically, or hysteroscopically.

Myomectomy seems largely to preserve fertility, but rates of recurrence and additional procedures for bleeding and myoma symptoms are still high – upward of 30% in some studies. Overall, we need other more efficacious and minimally invasive options.

Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation (RFVTA) achieved through the Acessa System (Halt Medical) has been the newest addition to our armamentarium for treatment of symptomatic fibroids. It is suitable for every type of fibroid except for type 0 pedunculated intracavitary fibroids and type 7 pedunculated subserosal fibroids, which is significant because deep intramural fibroids have been difficult to target and treat by other methods.

Three-year outcome data show sustained improvements in fibroid symptoms and quality of life, with an incidence of recurrences and additional procedures – approximately 11% – that appears to be substantially lower than for other uterine-sparing fibroid treatments. In addition, while the technology is not indicated for women seeking future childbearing, successful pregnancies are being reported, suggesting that full-term pregnancies – and vaginal delivery in some cases – may be possible after RFVTA.

The principles

Radiofrequency ablation has been used for years in the treatment of liver and kidney tumors. The basic concept is that volumetric thermal ablation results in coagulative necrosis.

The Acessa System, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in late 2012, was designed to treat fibroids, which have much firmer tissue than the tissues being targeted in other radiofrequency ablation procedures. It uses a specially designed intrauterine ultrasound probe and radiofrequency probe, and it combines three fundamental gynecologic skills: Laparoscopy using two trocars and requiring no special suturing skills; ultrasound using a laparoscopic ultrasound probe to scan and manipulate; and probe placement under laparoscopic ultrasound guidance.

Specifically, the system allows for percutaneous, laparoscopic ultrasound–guided radiofrequency ablation of fibroids with a disposable 3.4-mm handpiece coupled to a dual-function radiofrequency generator. The handpiece contains a retractable array of electrodes, so that the fibroid may be ablated with one electrode or with the deployed electrode array.

The generator controls and monitors the ablation with real-time feedback from thermocouples. It monitors and displays the temperature at each needle tip, the average temperature of the array, and the return temperatures on two dispersive electrode pads that are placed on the anterior thighs. The electrode pads are designed to reduce the incidence of pad burns, which are a complication with other radiofrequency ablation devices. The system will automatically stop treatment if either of the pad thermocouples registers a skin temperature greater than 40° C (JSLS. 2014 Apr-Jun;18[2]:182-90).

The outcomes

Laparoscopic ultrasound–guided RFVTA has been studied in five prospective trials, including one multicenter international trial of 135 premenopausal women – the pivotal trial for FDA clearance – in which 104 women were followed for 3 years and found to have prolonged symptom relief and improved quality of life.

At baseline, the women had symptomatic uterine myomas and moderate to severe heavy menstrual bleeding measured by alkaline hematin analysis of returned sanitary products. Their mean symptom severity scores on the Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (UFS-QOL) decreased significantly from baseline to 3 months and changed little after that, for a total change of –32.6 over the study period.

The cumulative repeat intervention rate at 3 years was 11%, with 14 of the 135 participants having repeat interventions to treat bleeding and myoma symptoms. Seven of these women were found to have adenomyosis (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 Sep-Oct;21[5]:767-74).

The surprisingly low reintervention rates may stem from the benefits of direct contact imaging of the uterus. A comparison of images from the pivotal trial has shown that intraoperative ultrasound detected more than twice as many fibroids as did preoperative transvaginal ultrasound, and about one-third more than preoperative MRIs (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Nov-Dec;20[6]:770-4).

Interestingly, four women became pregnant over the study’s 3-year follow-up, despite the inclusion requirement that women desire uterine conservation but not future childbearing.

We have followed reproductive outcomes in women after RFVTA of symptomatic fibroids in other studies as well. In our most recent analysis, presented in November at the 2015 American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists Global Congress, we identified 10 pregnancies among participants of the five prospective trials.

Of 232 women enrolled in premarket RFVTA studies – trials in which completing childbearing and continuing contraception were requirements – six conceived at 3.5-15 months post ablation. The number of myomas treated ranged from one to seven and included multiple types and dimensions. Five of these six women delivered full-term healthy babies – one by vaginal delivery and four by cesarean section. The sixth patient had a spontaneous abortion in the first trimester.

Of 43 women who participated in two randomized clinical trials undertaken after FDA clearance, four conceived at 4-23.5 months post ablation. Three of these women had uneventful, full-term pregnancies with vaginal births. The fourth had a cesarean section at 38 weeks.

Considering the theoretical advantages of the Acessa procedure – that it is less damaging to healthy myometrium – and the outcomes reported thus far, it appears likely that Acessa will be preferable to myomectomy. Early results from an ongoing 5-year German study that randomized 50 women to RFVTA or laparoscopic myomectomy show that RFVTA resulted in the treatment of more fibroids and involved a significantly shorter hospital stay and post-operative recovery (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014 Jun;125[3]:261-5).

The technique

The patient is pretreated with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent and prophylactic antibiotic. She is placed in a supine position with arms tucked, and a single-toothed tenaculum is placed on the cervix from 12 to 6 o’clock, without any instrument for manipulation of the uterus. The system’s dispersive electrode pads are placed symmetrically just above the patella on the anterior thighs; asymmetrical placement could potentially increase the risk of a pad burn.

Two standard laparoscopic ports are placed. A 5-mm trocar for the camera and video laparoscope is placed through the umbilicus or at a supraumbilical or left upper–quadrant level, depending on the patient’s anatomy, her surgical history, and the size of the uterus. A thorough visual inspection of the abdomen should be performed to look for unsuspected findings.

A 10-mm trocar is then placed at the level of the top of the fundus for the intra-abdominal ultrasound probe. Laparoscopic ultrasound is used to survey the entire uterus, map the fibroids, and plan an approach. Once the fibroid to be treated first is identified, the ability to stabilize the uterus accordingly is assessed, and the dimensions of the fibroid are taken. The dimensions will be used by the surgeon with a volume algorithm to calculate the length of ablation time based on the size of the fibroid and electrode deployment.

Under ultrasound guidance, the Acessa radiofrequency ablation handpiece is inserted percutaneously at 12, 3, 6, or 9 o’clock relative to the ultrasound trocar, based on the location of the target fibroid. The uterus must be stabilized, with the handpiece and ultrasound probe parallel and in plane. The handpiece is then inserted 1 cm into the target fibroid through the uterine serosal surface, utilizing a combination of laparoscopic and ultrasound views. Care must be taken to use gentle rotation and minimal downward pressure as the tip of the handpiece is quite sharp.

The location of the tip is confirmed by laparoscopic ultrasound, and the 7-needle electrode array can then be deployed to the ablation site. All three dimensions of the fibroid should be viewed for placement and deployment of the electrodes. Care is taken to avoid large blood vessels and ensure that the electrodes are confined within the fibroid and within the uterus.

Radiofrequency ablation is carried out with a low-voltage, high-frequency alternating current. The radiofrequency waves heat the tissue to an average temperature of 95° C for a length of time determined by a treatment algorithm. The wattage automatically adjusts to maintain the treatment temperature for the calculated duration of ablation.

Small fibroids can be treated in a manual mode without deployment of the electrode array at a current output of 15 W.

At the conclusion of the ablation, the electrodes are withdrawn into the handpiece, the generator is changed to coagulation mode, and the handpiece is slowly withdrawn under ultrasound visualization. The tract is simultaneously coagulated. A bit of additional coagulation is facilitated by pausing at the serosal surface.

Additional fibroids can be ablated through another insertion of the handpiece, either through the same tract or through a new tract.

Larger fibroids may require multiple ablations. The maximum size of ablation is about 5 cm, so it is important to plan the treatment of larger fibroids. This can be accomplished by carefully scanning large fibroids and visualizing the number of overlapping ablations needed to treat the entire volume. I ask my assistant to record the size and location of each ablation; I find this helpful both for organizing the treatment of large fibroids and for dictating the operative report.

It is important to appreciate that treatment of one area can make it difficult to visualize nearby fibroids with ultrasound. The effect dissipates in about 30-45 minutes. It is one reason why having a fibroid map prior to treatment is so important.

Once all fibroids are treated, a final inspection is performed. We usually use a suction irrigator to clean out whatever small amounts of blood are present, and the laparoscopic and port sites are closed in standard fashion.

Patients are seen 1 week postoperatively and are instructed to call in cases of pain, fever, bleeding, or chills. Most patients require only NSAIDs for pain relief and return to work in 2-7 days.

Many patients experience a slightly heavier than normal first menses after treatment. Pelvic rest is recommended for 3 weeks as a precaution, and avoidance of intrauterine procedures is advised because the uterus will be soft and thus may be easily perforated. Patients who have had type 1, type 2, or type 2-5 fibroids ablated may experience drainage for several weeks as the fibroid tissue is reabsorbed.

Dr. Berman is interim chairman of Wayne State University’s department of obstetrics and gynecology and interim specialist-in-chief for obstetrics and gynecology at the Detroit Medical Center. He was a principal investigator of the 3-year outcome study of Acessa sponsored by Halt Medical. He is a consultant for Halt Medical and directs physician training in the use of Acessa.

Uterine myomas cause heavy menstrual bleeding and other clinically significant symptoms in 35%-50% of affected women and have been shown to be the leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States among women aged 35-54 years.

Research has shown that a significant number of women who undergo hysterectomy for treatment of fibroids later regret the loss of their uterus and have other concerns and complications. Other options for therapy include various pharmacologic treatments, a progestin-releasing intrauterine device, uterine artery embolization, endometrial ablation, MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery, and myomectomy performed laparoscopically, robotically, or hysteroscopically.

Myomectomy seems largely to preserve fertility, but rates of recurrence and additional procedures for bleeding and myoma symptoms are still high – upward of 30% in some studies. Overall, we need other more efficacious and minimally invasive options.

Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation (RFVTA) achieved through the Acessa System (Halt Medical) has been the newest addition to our armamentarium for treatment of symptomatic fibroids. It is suitable for every type of fibroid except for type 0 pedunculated intracavitary fibroids and type 7 pedunculated subserosal fibroids, which is significant because deep intramural fibroids have been difficult to target and treat by other methods.

Three-year outcome data show sustained improvements in fibroid symptoms and quality of life, with an incidence of recurrences and additional procedures – approximately 11% – that appears to be substantially lower than for other uterine-sparing fibroid treatments. In addition, while the technology is not indicated for women seeking future childbearing, successful pregnancies are being reported, suggesting that full-term pregnancies – and vaginal delivery in some cases – may be possible after RFVTA.

The principles

Radiofrequency ablation has been used for years in the treatment of liver and kidney tumors. The basic concept is that volumetric thermal ablation results in coagulative necrosis.

The Acessa System, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in late 2012, was designed to treat fibroids, which have much firmer tissue than the tissues being targeted in other radiofrequency ablation procedures. It uses a specially designed intrauterine ultrasound probe and radiofrequency probe, and it combines three fundamental gynecologic skills: Laparoscopy using two trocars and requiring no special suturing skills; ultrasound using a laparoscopic ultrasound probe to scan and manipulate; and probe placement under laparoscopic ultrasound guidance.

Specifically, the system allows for percutaneous, laparoscopic ultrasound–guided radiofrequency ablation of fibroids with a disposable 3.4-mm handpiece coupled to a dual-function radiofrequency generator. The handpiece contains a retractable array of electrodes, so that the fibroid may be ablated with one electrode or with the deployed electrode array.

The generator controls and monitors the ablation with real-time feedback from thermocouples. It monitors and displays the temperature at each needle tip, the average temperature of the array, and the return temperatures on two dispersive electrode pads that are placed on the anterior thighs. The electrode pads are designed to reduce the incidence of pad burns, which are a complication with other radiofrequency ablation devices. The system will automatically stop treatment if either of the pad thermocouples registers a skin temperature greater than 40° C (JSLS. 2014 Apr-Jun;18[2]:182-90).

The outcomes

Laparoscopic ultrasound–guided RFVTA has been studied in five prospective trials, including one multicenter international trial of 135 premenopausal women – the pivotal trial for FDA clearance – in which 104 women were followed for 3 years and found to have prolonged symptom relief and improved quality of life.

At baseline, the women had symptomatic uterine myomas and moderate to severe heavy menstrual bleeding measured by alkaline hematin analysis of returned sanitary products. Their mean symptom severity scores on the Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (UFS-QOL) decreased significantly from baseline to 3 months and changed little after that, for a total change of –32.6 over the study period.

The cumulative repeat intervention rate at 3 years was 11%, with 14 of the 135 participants having repeat interventions to treat bleeding and myoma symptoms. Seven of these women were found to have adenomyosis (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 Sep-Oct;21[5]:767-74).

The surprisingly low reintervention rates may stem from the benefits of direct contact imaging of the uterus. A comparison of images from the pivotal trial has shown that intraoperative ultrasound detected more than twice as many fibroids as did preoperative transvaginal ultrasound, and about one-third more than preoperative MRIs (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Nov-Dec;20[6]:770-4).

Interestingly, four women became pregnant over the study’s 3-year follow-up, despite the inclusion requirement that women desire uterine conservation but not future childbearing.

We have followed reproductive outcomes in women after RFVTA of symptomatic fibroids in other studies as well. In our most recent analysis, presented in November at the 2015 American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists Global Congress, we identified 10 pregnancies among participants of the five prospective trials.

Of 232 women enrolled in premarket RFVTA studies – trials in which completing childbearing and continuing contraception were requirements – six conceived at 3.5-15 months post ablation. The number of myomas treated ranged from one to seven and included multiple types and dimensions. Five of these six women delivered full-term healthy babies – one by vaginal delivery and four by cesarean section. The sixth patient had a spontaneous abortion in the first trimester.

Of 43 women who participated in two randomized clinical trials undertaken after FDA clearance, four conceived at 4-23.5 months post ablation. Three of these women had uneventful, full-term pregnancies with vaginal births. The fourth had a cesarean section at 38 weeks.

Considering the theoretical advantages of the Acessa procedure – that it is less damaging to healthy myometrium – and the outcomes reported thus far, it appears likely that Acessa will be preferable to myomectomy. Early results from an ongoing 5-year German study that randomized 50 women to RFVTA or laparoscopic myomectomy show that RFVTA resulted in the treatment of more fibroids and involved a significantly shorter hospital stay and post-operative recovery (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014 Jun;125[3]:261-5).

The technique

The patient is pretreated with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent and prophylactic antibiotic. She is placed in a supine position with arms tucked, and a single-toothed tenaculum is placed on the cervix from 12 to 6 o’clock, without any instrument for manipulation of the uterus. The system’s dispersive electrode pads are placed symmetrically just above the patella on the anterior thighs; asymmetrical placement could potentially increase the risk of a pad burn.

Two standard laparoscopic ports are placed. A 5-mm trocar for the camera and video laparoscope is placed through the umbilicus or at a supraumbilical or left upper–quadrant level, depending on the patient’s anatomy, her surgical history, and the size of the uterus. A thorough visual inspection of the abdomen should be performed to look for unsuspected findings.

A 10-mm trocar is then placed at the level of the top of the fundus for the intra-abdominal ultrasound probe. Laparoscopic ultrasound is used to survey the entire uterus, map the fibroids, and plan an approach. Once the fibroid to be treated first is identified, the ability to stabilize the uterus accordingly is assessed, and the dimensions of the fibroid are taken. The dimensions will be used by the surgeon with a volume algorithm to calculate the length of ablation time based on the size of the fibroid and electrode deployment.

Under ultrasound guidance, the Acessa radiofrequency ablation handpiece is inserted percutaneously at 12, 3, 6, or 9 o’clock relative to the ultrasound trocar, based on the location of the target fibroid. The uterus must be stabilized, with the handpiece and ultrasound probe parallel and in plane. The handpiece is then inserted 1 cm into the target fibroid through the uterine serosal surface, utilizing a combination of laparoscopic and ultrasound views. Care must be taken to use gentle rotation and minimal downward pressure as the tip of the handpiece is quite sharp.

The location of the tip is confirmed by laparoscopic ultrasound, and the 7-needle electrode array can then be deployed to the ablation site. All three dimensions of the fibroid should be viewed for placement and deployment of the electrodes. Care is taken to avoid large blood vessels and ensure that the electrodes are confined within the fibroid and within the uterus.

Radiofrequency ablation is carried out with a low-voltage, high-frequency alternating current. The radiofrequency waves heat the tissue to an average temperature of 95° C for a length of time determined by a treatment algorithm. The wattage automatically adjusts to maintain the treatment temperature for the calculated duration of ablation.

Small fibroids can be treated in a manual mode without deployment of the electrode array at a current output of 15 W.

At the conclusion of the ablation, the electrodes are withdrawn into the handpiece, the generator is changed to coagulation mode, and the handpiece is slowly withdrawn under ultrasound visualization. The tract is simultaneously coagulated. A bit of additional coagulation is facilitated by pausing at the serosal surface.

Additional fibroids can be ablated through another insertion of the handpiece, either through the same tract or through a new tract.

Larger fibroids may require multiple ablations. The maximum size of ablation is about 5 cm, so it is important to plan the treatment of larger fibroids. This can be accomplished by carefully scanning large fibroids and visualizing the number of overlapping ablations needed to treat the entire volume. I ask my assistant to record the size and location of each ablation; I find this helpful both for organizing the treatment of large fibroids and for dictating the operative report.

It is important to appreciate that treatment of one area can make it difficult to visualize nearby fibroids with ultrasound. The effect dissipates in about 30-45 minutes. It is one reason why having a fibroid map prior to treatment is so important.

Once all fibroids are treated, a final inspection is performed. We usually use a suction irrigator to clean out whatever small amounts of blood are present, and the laparoscopic and port sites are closed in standard fashion.

Patients are seen 1 week postoperatively and are instructed to call in cases of pain, fever, bleeding, or chills. Most patients require only NSAIDs for pain relief and return to work in 2-7 days.

Many patients experience a slightly heavier than normal first menses after treatment. Pelvic rest is recommended for 3 weeks as a precaution, and avoidance of intrauterine procedures is advised because the uterus will be soft and thus may be easily perforated. Patients who have had type 1, type 2, or type 2-5 fibroids ablated may experience drainage for several weeks as the fibroid tissue is reabsorbed.

Dr. Berman is interim chairman of Wayne State University’s department of obstetrics and gynecology and interim specialist-in-chief for obstetrics and gynecology at the Detroit Medical Center. He was a principal investigator of the 3-year outcome study of Acessa sponsored by Halt Medical. He is a consultant for Halt Medical and directs physician training in the use of Acessa.

Lessons learned from the history of VBAC

In December 2014, The Wall Street Journal ran an article about a young mother who wanted a vaginal birth after C-section (VBAC) for her second child. After her hospital stopped offering VBACs, the woman had to find another place to deliver. She did have a successful VBAC, but her story is not unique – many women may not receive adequate consultations about or provider support for VBAC as a delivery option.

According to the article, a lack of clinical support was the reason the hospital discontinued VBACs. Although the hospital’s decision may have frustrated the mother, this ensured that she would not be promised a birthing option that the hospital could not deliver – in all senses of this word. Successful VBAC requires proper patient selection, appropriate consent and adequate provisions in case of emergencies.

Not every hospital has made such a choice. Based on studies of a trial of labor after cesarean, conducted after the 1960s, the rate of VBACs increased. As VBACs became more common, the approach to the procedure became more relaxed. VBACs went from only being performed in tertiary care hospitals with appropriate support for emergencies, to community hospitals with no backup. Patient selection became less rigorous, and the rate of complications went up, which, in turn, caused the number of associated legal claims to rise. Hospitals started discouraging VBACs, and ob.gyns. no longer counseled their patients about this option. The VBAC rate decreased, and the C-section rate increased.

Today, many women want to pursue a trial of labor after cesarean. Data from large clinical studies have demonstrated the safety and success of VBAC with proper care. Because of the storied history and a revival of interest in VBACs, we have invited Dr. Mark Landon, the Richard L. Meiling Professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, and the lead on one of the recent seminal VBAC studies, to address this topic.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece reported having no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In December 2014, The Wall Street Journal ran an article about a young mother who wanted a vaginal birth after C-section (VBAC) for her second child. After her hospital stopped offering VBACs, the woman had to find another place to deliver. She did have a successful VBAC, but her story is not unique – many women may not receive adequate consultations about or provider support for VBAC as a delivery option.

According to the article, a lack of clinical support was the reason the hospital discontinued VBACs. Although the hospital’s decision may have frustrated the mother, this ensured that she would not be promised a birthing option that the hospital could not deliver – in all senses of this word. Successful VBAC requires proper patient selection, appropriate consent and adequate provisions in case of emergencies.

Not every hospital has made such a choice. Based on studies of a trial of labor after cesarean, conducted after the 1960s, the rate of VBACs increased. As VBACs became more common, the approach to the procedure became more relaxed. VBACs went from only being performed in tertiary care hospitals with appropriate support for emergencies, to community hospitals with no backup. Patient selection became less rigorous, and the rate of complications went up, which, in turn, caused the number of associated legal claims to rise. Hospitals started discouraging VBACs, and ob.gyns. no longer counseled their patients about this option. The VBAC rate decreased, and the C-section rate increased.

Today, many women want to pursue a trial of labor after cesarean. Data from large clinical studies have demonstrated the safety and success of VBAC with proper care. Because of the storied history and a revival of interest in VBACs, we have invited Dr. Mark Landon, the Richard L. Meiling Professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, and the lead on one of the recent seminal VBAC studies, to address this topic.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece reported having no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In December 2014, The Wall Street Journal ran an article about a young mother who wanted a vaginal birth after C-section (VBAC) for her second child. After her hospital stopped offering VBACs, the woman had to find another place to deliver. She did have a successful VBAC, but her story is not unique – many women may not receive adequate consultations about or provider support for VBAC as a delivery option.

According to the article, a lack of clinical support was the reason the hospital discontinued VBACs. Although the hospital’s decision may have frustrated the mother, this ensured that she would not be promised a birthing option that the hospital could not deliver – in all senses of this word. Successful VBAC requires proper patient selection, appropriate consent and adequate provisions in case of emergencies.

Not every hospital has made such a choice. Based on studies of a trial of labor after cesarean, conducted after the 1960s, the rate of VBACs increased. As VBACs became more common, the approach to the procedure became more relaxed. VBACs went from only being performed in tertiary care hospitals with appropriate support for emergencies, to community hospitals with no backup. Patient selection became less rigorous, and the rate of complications went up, which, in turn, caused the number of associated legal claims to rise. Hospitals started discouraging VBACs, and ob.gyns. no longer counseled their patients about this option. The VBAC rate decreased, and the C-section rate increased.

Today, many women want to pursue a trial of labor after cesarean. Data from large clinical studies have demonstrated the safety and success of VBAC with proper care. Because of the storied history and a revival of interest in VBACs, we have invited Dr. Mark Landon, the Richard L. Meiling Professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, and the lead on one of the recent seminal VBAC studies, to address this topic.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece reported having no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Barriers to VBAC remain in spite of evidence

The relative safety of vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) has been documented in several large-scale studies in the past 15 years, and was affirmed in 2010 through a National Institutes of Health consensus development conference and a practice bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Yet, despite all this research and review, rates of a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) have increased only modestly in the last several years.

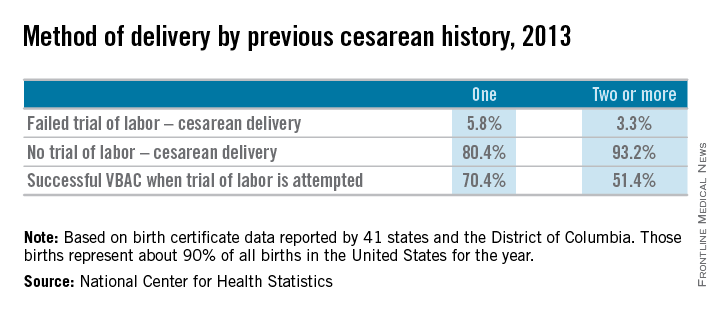

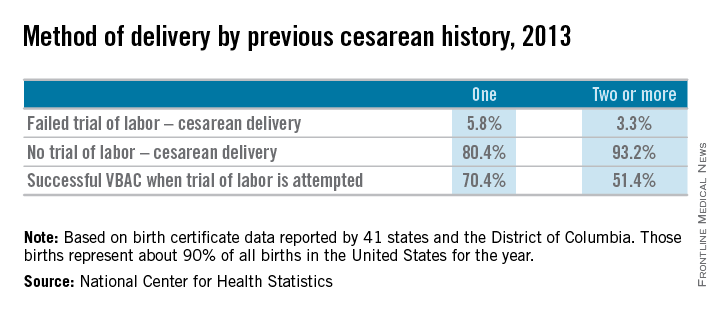

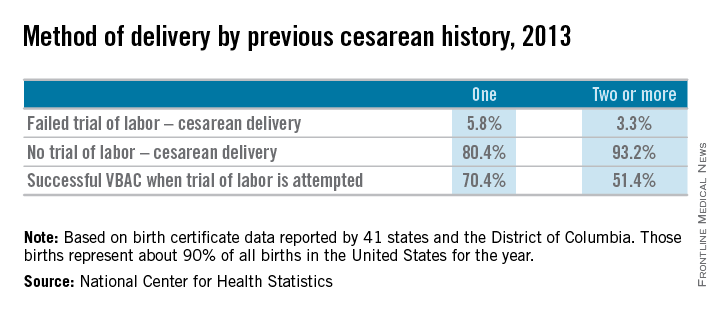

Approximately 20% of all births in 2013 in women with a history of one cesarean section involved a trial of labor, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This represents only a small increase from 2006, when the TOLAC rate had plummeted to approximately 15%.

The limited change is concerning because up to two-thirds of women with a prior cesarean delivery are candidates for a trial of labor, and many of them are excellent candidates. In total, 70% of the women who attempted labor in 2013 after a previous cesarean had successful VBACs, the CDC data shows.

Several European countries have TOLAC rates between 50% and 70%, but in the United States, as evidenced by the recent CDC data, there continues to be an underutilization of attempted VBAC. We must ask ourselves, are women truly able to choose TOLAC, or are they being dissuaded by the health care system?

I believe that the barriers are still pervasive. Too often, women who are TOLAC candidates are not receiving appropriate counseling – and too often, women are not even being presented the option of a trial of labor, even when staff are immediately available to provide emergency care if needed.

Rupture concerns in perspective

When the NIH consensus development panel reviewed VBAC in 2010, it concluded that TOLAC is a reasonable option for many women with a prior cesarean. The panel found that restricted access to VBAC/TOLAC stemmed from existing practice guidelines and the medical liability climate, and it called upon providers and others to “mitigate or even eliminate” the barriers that women face in finding clinicians and facilities able and willing to offer TOLAC.

ACOG’s 2010 practice bulletin also acknowledged the problem of limited access. ACOG recommended, as it had in an earlier bulletin, that TOLAC-VBAC be undertaken in facilities where staff are immediately available for emergency care. It added, however, that when such resources are not available, the best alternative may be to refer patients to a facility with available resources. Health care providers and insurance carriers “should do all they can to facilitate transfer of care or comanagement in support of a desired TOLAC,” ACOG’s document states.

Why, given such recommendations, are we still falling so short of where we should be?

A number of nonclinical factors are involved, but clearly, as both the NIH and ACOG have stated, the fear of litigation in cases of uterine rupture is a contributing factor. A ruptured uterus is indeed the principal risk associated with TOLAC, and it can have serious sequelae including perinatal death, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and hysterectomy.

We must appreciate, however, that the absolute rates of uterine rupture and of serious adverse outcomes are quite low. The rupture rate in 2013 among women who underwent TOLAC but ultimately had a repeat cesarean section – the highest-risk group – was 495 per 100,000 live births, according to the CDC. This rate of approximately 0.5% is consistent with the level of risk reported in the literature for several decades.

In one of the two large observational studies done in the United States that have shed light on TOLAC outcomes, the rate of uterine rupture among women who underwent TOLAC was 0.7% for women with a prior low transverse incision, 2.0% for those with a prior low vertical incision, and 0.5% for those with an unknown type of prior incision. Overall, the rate of uterine rupture in this study’s cohort of 17,898 women who underwent TOLAC was 0.7% (N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 16;351[25]:2581-9). The study was conducted at 19 medical centers belonging to the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Maternal-Fetal Medical Units (MFMU) Network.

The second large study conducted in the United States – a multicenter observational study in which records of approximately 25,000 women with a prior low-transverse cesarean section were reviewed – also showed rates of uterine rupture less than 1% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;193[5]:1656-62).

The attributable risk for perinatal death or HIE at term appears to be 1 per 2,000 TOLAC, according to the MFMU Network study.

Failed trials of labor resulting in repeat cesarean deliveries have consistently been associated with higher morbidity than scheduled repeat cesarean deliveries, with the greatest difference in rates for ruptured uterus. In the first MFMU Network study, there were no cases of uterine rupture among a cohort of 15,801 women who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery, and in the second multicenter study of 25,000 women, this patient group had a rupture rate of 0.004%.

Yet, as ACOG points out, neither elective repeat cesarean deliveries nor TOLAC are without maternal or neonatal risk. Women who have successful VBAC delivery, on the other hand, have significantly lower morbidity and better outcomes than women who do not attempt labor. Women who undergo VBAC also avoid exposure to the significant risks of repeat cesarean deliveries in the long term.

Research unequivocally shows that the risk of placenta accreta, hysterectomy, hemorrhage, and other serious maternal morbidity increases progressively with each repeat cesarean delivery. Rates of placenta accreta have, in fact, been rising in the United States – a trend that should prompt us to think more about TOLAC.

Moreover, TOLAC is being shown to be a cost-effective strategy. In one analysis, TOLAC in a second pregnancy was cost-effective as long as the chance of VBAC exceeded approximately 74% (Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jun;97[6]:932-41). More recently, TOLAC was found to be cost-effective across a wide variety of circumstances, including when a woman had a probability of VBAC as low as 43%. The model in this analysis, which used probability estimates from the MFMU Cesarean Registry, took a longer-term view by including probabilities of outcomes throughout a woman’s reproductive life that were contingent upon her initial choice regarding TOLAC (Am J Perinatol. 2013 Jan;30[1]:11-20).

Likelihood of success

Evaluating and discussing the likelihood of success with TOLAC is therefore key to the counseling process. The higher the likelihood of achieving VBAC, the more favorable the risk-benefit ratio will be and the more appealing it will be to consider.

According to one analysis, if a woman undergoing a TOLAC has at least a 60%-70% chance of VBAC, her chance of having major or minor morbidity is no greater than a woman undergoing a planned repeat cesarean delivery (Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:56.e1-e6).

There are several prediction tools available that can be used at the first prenatal visit and in early labor to give a reasonably good estimate of success. One of these tools is available at the MFMU Network website (http://mfmu.bsc.gwu.edu). The tools take into account factors such as prior indication for cesarean delivery; history of vaginal delivery; demographic characteristics such as maternal age and body mass index; the occurrence of spontaneous labor; and cervical status at admission.

Prior vaginal delivery is one of the strongest predictors of a successful TOLAC. Research has consistently shown that women with a prior vaginal delivery – including a vaginal delivery predating an unsuccessful TOLAC – have significantly higher TOLAC success rates than women who did not have any prior vaginal delivery.

The indication for a prior cesarean delivery also clearly affects the likelihood of a successful TOLAC. Women whose first cesarean delivery was performed for a nonrecurring indication, such as breech presentation or low intolerance of labor, have TOLAC success rates that are similar to vaginal delivery rates for nulliparous women. Success rates for these women may exceed 85%. On the other hand, women who had a prior cesarean delivery for cephalopelvic disproportion or failure to progress have been shown to have lower TOLAC success rates ranging from 50%-67%.

Labor induction should be approached cautiously, as women who undergo induction of labor in TOLAC have an increased risk of repeat cesarean delivery. Still, success rates with induction are high. Data from the MFMU Cesarean Registry showed that about 66% of women undergoing induction after one prior cesarean delivery achieved VBAC versus 76% of women entering TOLAC spontaneously (Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Feb;109[2 Pt 1]:262-9). Another study of women undergoing induction after one prior cesarean reported an overall success rate of 78% (Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Mar;103[3]:534-8).

Whether induction specifically increases the risk for uterine rupture in TOLAC, compared with expectant management, is unclear. There also are conflicting data as to whether particular induction methods increase this risk.

Based on available data, ACOG considers induction of labor for either maternal or fetal indications to be an option for women undergoing TOLAC. Oxytocin may be used for induction as well as augmentation, but caution should be exercised at higher doses. While there is no clear dosing threshold for increased risk of rupture, research has suggested that higher doses of oxytocin are best avoided.

The use of prostaglandins is more controversial: Based on evidence from several small studies, ACOG concluded in its 2010 bulletin that misoprostol (prostaglandin E1) for cervical ripening is contraindicated in women undergoing TOLAC. It appears likely that rupture risk increases in patients who received both prostaglandins and oxytocin, so ACOG has advised avoiding their sequential use when prostaglandin E2 is used. This of course limits the options for the practitioner. Therefore, utilizing a Foley catheter followed by pitocin has been an approach advocated in some cases.

Uterine rupture is not predictable, and it is far more difficult to assess an individual’s risk of this complication than it is to assess the likelihood of VBAC. Still, there is value to discussing with the patient whether there are any other modifiers that could potentially influence the risk of rupture.

Since rates of uterine rupture are highest in women with previous classical or T-shaped incision, for example, it is important to try to ascertain what type of incision was previously used. It is widely appreciated that low-transverse uterine incisions are most favorable, but findings are mixed in regard to low-vertical incisions. Some research shows that women with a previous low-vertical incision do not have significantly lower VBAC success rates or higher risks of uterine rupture. TOLAC should therefore not be ruled out in these cases.

Additionally, TOLAC should not be ruled out for women who have had more than one cesarean delivery. Several studies have shown an increased risk of uterine rupture after two prior cesarean deliveries, compared with one, and one meta-analysis suggested a more than twofold increased risk (BJOG. 2010 Jan;117(1):5-19.).

In contrast, an analysis of the MFMU Cesarean Registry found no significant difference in rupture rates in women with one prior cesarean versus multiple prior cesareans (Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jul;108[1]:12-20.).

It appears, therefore, that even if having more than one prior cesarean section is associated with an increased risk of rupture, the magnitude of this increase is small.

Just as women with a prior vaginal delivery have the highest chance of VBAC success, they also have the lowest rates of rupture among all women undergoing TOLAC.

Patient counseling

We must inform our patients who have had a cesarean section in the past of their options for childbirth in an unbiased manner.

The complications of both TOLAC and elective repeat cesarean section should be discussed, and every attempt should be made to individually assess both the likelihood of a successful VBAC and the comparative risk of maternal and perinatal morbidity. A shared decision-making process should be adopted, and whenever possible, the patient’s preference should be respected. In the end, a woman undergoing TOLAC should be truly motivated to pursue a trial of labor, because there are inherent risks.

One thing I’ve learned from my clinical practice and research on this issue is that the desire to undergo a vaginal delivery is powerful for some women. Many of my patients have self-referred for consultation about TOLAC after their ob.gyn. informed them that their hospital is not equipped, and they should therefore have a scheduled repeat operation. In many cases they discover that TOLAC is an option if they are willing to travel a half-hour or so.

We need to honor this desire and inform our patients of the option, and help facilitate delivery at another nearby hospital when our own facility is not equipped for TOLAC.

Dr. Landon is the Richard L. Meiling Professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, Columbus. He served for more than 25 years as Ohio State’s coinvestigator for the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The relative safety of vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) has been documented in several large-scale studies in the past 15 years, and was affirmed in 2010 through a National Institutes of Health consensus development conference and a practice bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Yet, despite all this research and review, rates of a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) have increased only modestly in the last several years.

Approximately 20% of all births in 2013 in women with a history of one cesarean section involved a trial of labor, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This represents only a small increase from 2006, when the TOLAC rate had plummeted to approximately 15%.

The limited change is concerning because up to two-thirds of women with a prior cesarean delivery are candidates for a trial of labor, and many of them are excellent candidates. In total, 70% of the women who attempted labor in 2013 after a previous cesarean had successful VBACs, the CDC data shows.

Several European countries have TOLAC rates between 50% and 70%, but in the United States, as evidenced by the recent CDC data, there continues to be an underutilization of attempted VBAC. We must ask ourselves, are women truly able to choose TOLAC, or are they being dissuaded by the health care system?

I believe that the barriers are still pervasive. Too often, women who are TOLAC candidates are not receiving appropriate counseling – and too often, women are not even being presented the option of a trial of labor, even when staff are immediately available to provide emergency care if needed.

Rupture concerns in perspective

When the NIH consensus development panel reviewed VBAC in 2010, it concluded that TOLAC is a reasonable option for many women with a prior cesarean. The panel found that restricted access to VBAC/TOLAC stemmed from existing practice guidelines and the medical liability climate, and it called upon providers and others to “mitigate or even eliminate” the barriers that women face in finding clinicians and facilities able and willing to offer TOLAC.

ACOG’s 2010 practice bulletin also acknowledged the problem of limited access. ACOG recommended, as it had in an earlier bulletin, that TOLAC-VBAC be undertaken in facilities where staff are immediately available for emergency care. It added, however, that when such resources are not available, the best alternative may be to refer patients to a facility with available resources. Health care providers and insurance carriers “should do all they can to facilitate transfer of care or comanagement in support of a desired TOLAC,” ACOG’s document states.

Why, given such recommendations, are we still falling so short of where we should be?

A number of nonclinical factors are involved, but clearly, as both the NIH and ACOG have stated, the fear of litigation in cases of uterine rupture is a contributing factor. A ruptured uterus is indeed the principal risk associated with TOLAC, and it can have serious sequelae including perinatal death, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and hysterectomy.

We must appreciate, however, that the absolute rates of uterine rupture and of serious adverse outcomes are quite low. The rupture rate in 2013 among women who underwent TOLAC but ultimately had a repeat cesarean section – the highest-risk group – was 495 per 100,000 live births, according to the CDC. This rate of approximately 0.5% is consistent with the level of risk reported in the literature for several decades.

In one of the two large observational studies done in the United States that have shed light on TOLAC outcomes, the rate of uterine rupture among women who underwent TOLAC was 0.7% for women with a prior low transverse incision, 2.0% for those with a prior low vertical incision, and 0.5% for those with an unknown type of prior incision. Overall, the rate of uterine rupture in this study’s cohort of 17,898 women who underwent TOLAC was 0.7% (N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 16;351[25]:2581-9). The study was conducted at 19 medical centers belonging to the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Maternal-Fetal Medical Units (MFMU) Network.

The second large study conducted in the United States – a multicenter observational study in which records of approximately 25,000 women with a prior low-transverse cesarean section were reviewed – also showed rates of uterine rupture less than 1% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;193[5]:1656-62).

The attributable risk for perinatal death or HIE at term appears to be 1 per 2,000 TOLAC, according to the MFMU Network study.

Failed trials of labor resulting in repeat cesarean deliveries have consistently been associated with higher morbidity than scheduled repeat cesarean deliveries, with the greatest difference in rates for ruptured uterus. In the first MFMU Network study, there were no cases of uterine rupture among a cohort of 15,801 women who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery, and in the second multicenter study of 25,000 women, this patient group had a rupture rate of 0.004%.

Yet, as ACOG points out, neither elective repeat cesarean deliveries nor TOLAC are without maternal or neonatal risk. Women who have successful VBAC delivery, on the other hand, have significantly lower morbidity and better outcomes than women who do not attempt labor. Women who undergo VBAC also avoid exposure to the significant risks of repeat cesarean deliveries in the long term.

Research unequivocally shows that the risk of placenta accreta, hysterectomy, hemorrhage, and other serious maternal morbidity increases progressively with each repeat cesarean delivery. Rates of placenta accreta have, in fact, been rising in the United States – a trend that should prompt us to think more about TOLAC.

Moreover, TOLAC is being shown to be a cost-effective strategy. In one analysis, TOLAC in a second pregnancy was cost-effective as long as the chance of VBAC exceeded approximately 74% (Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jun;97[6]:932-41). More recently, TOLAC was found to be cost-effective across a wide variety of circumstances, including when a woman had a probability of VBAC as low as 43%. The model in this analysis, which used probability estimates from the MFMU Cesarean Registry, took a longer-term view by including probabilities of outcomes throughout a woman’s reproductive life that were contingent upon her initial choice regarding TOLAC (Am J Perinatol. 2013 Jan;30[1]:11-20).

Likelihood of success

Evaluating and discussing the likelihood of success with TOLAC is therefore key to the counseling process. The higher the likelihood of achieving VBAC, the more favorable the risk-benefit ratio will be and the more appealing it will be to consider.

According to one analysis, if a woman undergoing a TOLAC has at least a 60%-70% chance of VBAC, her chance of having major or minor morbidity is no greater than a woman undergoing a planned repeat cesarean delivery (Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:56.e1-e6).

There are several prediction tools available that can be used at the first prenatal visit and in early labor to give a reasonably good estimate of success. One of these tools is available at the MFMU Network website (http://mfmu.bsc.gwu.edu). The tools take into account factors such as prior indication for cesarean delivery; history of vaginal delivery; demographic characteristics such as maternal age and body mass index; the occurrence of spontaneous labor; and cervical status at admission.

Prior vaginal delivery is one of the strongest predictors of a successful TOLAC. Research has consistently shown that women with a prior vaginal delivery – including a vaginal delivery predating an unsuccessful TOLAC – have significantly higher TOLAC success rates than women who did not have any prior vaginal delivery.

The indication for a prior cesarean delivery also clearly affects the likelihood of a successful TOLAC. Women whose first cesarean delivery was performed for a nonrecurring indication, such as breech presentation or low intolerance of labor, have TOLAC success rates that are similar to vaginal delivery rates for nulliparous women. Success rates for these women may exceed 85%. On the other hand, women who had a prior cesarean delivery for cephalopelvic disproportion or failure to progress have been shown to have lower TOLAC success rates ranging from 50%-67%.

Labor induction should be approached cautiously, as women who undergo induction of labor in TOLAC have an increased risk of repeat cesarean delivery. Still, success rates with induction are high. Data from the MFMU Cesarean Registry showed that about 66% of women undergoing induction after one prior cesarean delivery achieved VBAC versus 76% of women entering TOLAC spontaneously (Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Feb;109[2 Pt 1]:262-9). Another study of women undergoing induction after one prior cesarean reported an overall success rate of 78% (Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Mar;103[3]:534-8).

Whether induction specifically increases the risk for uterine rupture in TOLAC, compared with expectant management, is unclear. There also are conflicting data as to whether particular induction methods increase this risk.

Based on available data, ACOG considers induction of labor for either maternal or fetal indications to be an option for women undergoing TOLAC. Oxytocin may be used for induction as well as augmentation, but caution should be exercised at higher doses. While there is no clear dosing threshold for increased risk of rupture, research has suggested that higher doses of oxytocin are best avoided.

The use of prostaglandins is more controversial: Based on evidence from several small studies, ACOG concluded in its 2010 bulletin that misoprostol (prostaglandin E1) for cervical ripening is contraindicated in women undergoing TOLAC. It appears likely that rupture risk increases in patients who received both prostaglandins and oxytocin, so ACOG has advised avoiding their sequential use when prostaglandin E2 is used. This of course limits the options for the practitioner. Therefore, utilizing a Foley catheter followed by pitocin has been an approach advocated in some cases.

Uterine rupture is not predictable, and it is far more difficult to assess an individual’s risk of this complication than it is to assess the likelihood of VBAC. Still, there is value to discussing with the patient whether there are any other modifiers that could potentially influence the risk of rupture.

Since rates of uterine rupture are highest in women with previous classical or T-shaped incision, for example, it is important to try to ascertain what type of incision was previously used. It is widely appreciated that low-transverse uterine incisions are most favorable, but findings are mixed in regard to low-vertical incisions. Some research shows that women with a previous low-vertical incision do not have significantly lower VBAC success rates or higher risks of uterine rupture. TOLAC should therefore not be ruled out in these cases.

Additionally, TOLAC should not be ruled out for women who have had more than one cesarean delivery. Several studies have shown an increased risk of uterine rupture after two prior cesarean deliveries, compared with one, and one meta-analysis suggested a more than twofold increased risk (BJOG. 2010 Jan;117(1):5-19.).

In contrast, an analysis of the MFMU Cesarean Registry found no significant difference in rupture rates in women with one prior cesarean versus multiple prior cesareans (Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jul;108[1]:12-20.).

It appears, therefore, that even if having more than one prior cesarean section is associated with an increased risk of rupture, the magnitude of this increase is small.

Just as women with a prior vaginal delivery have the highest chance of VBAC success, they also have the lowest rates of rupture among all women undergoing TOLAC.

Patient counseling

We must inform our patients who have had a cesarean section in the past of their options for childbirth in an unbiased manner.

The complications of both TOLAC and elective repeat cesarean section should be discussed, and every attempt should be made to individually assess both the likelihood of a successful VBAC and the comparative risk of maternal and perinatal morbidity. A shared decision-making process should be adopted, and whenever possible, the patient’s preference should be respected. In the end, a woman undergoing TOLAC should be truly motivated to pursue a trial of labor, because there are inherent risks.

One thing I’ve learned from my clinical practice and research on this issue is that the desire to undergo a vaginal delivery is powerful for some women. Many of my patients have self-referred for consultation about TOLAC after their ob.gyn. informed them that their hospital is not equipped, and they should therefore have a scheduled repeat operation. In many cases they discover that TOLAC is an option if they are willing to travel a half-hour or so.

We need to honor this desire and inform our patients of the option, and help facilitate delivery at another nearby hospital when our own facility is not equipped for TOLAC.

Dr. Landon is the Richard L. Meiling Professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, Columbus. He served for more than 25 years as Ohio State’s coinvestigator for the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The relative safety of vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) has been documented in several large-scale studies in the past 15 years, and was affirmed in 2010 through a National Institutes of Health consensus development conference and a practice bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Yet, despite all this research and review, rates of a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) have increased only modestly in the last several years.

Approximately 20% of all births in 2013 in women with a history of one cesarean section involved a trial of labor, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This represents only a small increase from 2006, when the TOLAC rate had plummeted to approximately 15%.

The limited change is concerning because up to two-thirds of women with a prior cesarean delivery are candidates for a trial of labor, and many of them are excellent candidates. In total, 70% of the women who attempted labor in 2013 after a previous cesarean had successful VBACs, the CDC data shows.

Several European countries have TOLAC rates between 50% and 70%, but in the United States, as evidenced by the recent CDC data, there continues to be an underutilization of attempted VBAC. We must ask ourselves, are women truly able to choose TOLAC, or are they being dissuaded by the health care system?

I believe that the barriers are still pervasive. Too often, women who are TOLAC candidates are not receiving appropriate counseling – and too often, women are not even being presented the option of a trial of labor, even when staff are immediately available to provide emergency care if needed.

Rupture concerns in perspective

When the NIH consensus development panel reviewed VBAC in 2010, it concluded that TOLAC is a reasonable option for many women with a prior cesarean. The panel found that restricted access to VBAC/TOLAC stemmed from existing practice guidelines and the medical liability climate, and it called upon providers and others to “mitigate or even eliminate” the barriers that women face in finding clinicians and facilities able and willing to offer TOLAC.

ACOG’s 2010 practice bulletin also acknowledged the problem of limited access. ACOG recommended, as it had in an earlier bulletin, that TOLAC-VBAC be undertaken in facilities where staff are immediately available for emergency care. It added, however, that when such resources are not available, the best alternative may be to refer patients to a facility with available resources. Health care providers and insurance carriers “should do all they can to facilitate transfer of care or comanagement in support of a desired TOLAC,” ACOG’s document states.

Why, given such recommendations, are we still falling so short of where we should be?

A number of nonclinical factors are involved, but clearly, as both the NIH and ACOG have stated, the fear of litigation in cases of uterine rupture is a contributing factor. A ruptured uterus is indeed the principal risk associated with TOLAC, and it can have serious sequelae including perinatal death, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and hysterectomy.

We must appreciate, however, that the absolute rates of uterine rupture and of serious adverse outcomes are quite low. The rupture rate in 2013 among women who underwent TOLAC but ultimately had a repeat cesarean section – the highest-risk group – was 495 per 100,000 live births, according to the CDC. This rate of approximately 0.5% is consistent with the level of risk reported in the literature for several decades.

In one of the two large observational studies done in the United States that have shed light on TOLAC outcomes, the rate of uterine rupture among women who underwent TOLAC was 0.7% for women with a prior low transverse incision, 2.0% for those with a prior low vertical incision, and 0.5% for those with an unknown type of prior incision. Overall, the rate of uterine rupture in this study’s cohort of 17,898 women who underwent TOLAC was 0.7% (N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 16;351[25]:2581-9). The study was conducted at 19 medical centers belonging to the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Maternal-Fetal Medical Units (MFMU) Network.

The second large study conducted in the United States – a multicenter observational study in which records of approximately 25,000 women with a prior low-transverse cesarean section were reviewed – also showed rates of uterine rupture less than 1% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;193[5]:1656-62).

The attributable risk for perinatal death or HIE at term appears to be 1 per 2,000 TOLAC, according to the MFMU Network study.

Failed trials of labor resulting in repeat cesarean deliveries have consistently been associated with higher morbidity than scheduled repeat cesarean deliveries, with the greatest difference in rates for ruptured uterus. In the first MFMU Network study, there were no cases of uterine rupture among a cohort of 15,801 women who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery, and in the second multicenter study of 25,000 women, this patient group had a rupture rate of 0.004%.

Yet, as ACOG points out, neither elective repeat cesarean deliveries nor TOLAC are without maternal or neonatal risk. Women who have successful VBAC delivery, on the other hand, have significantly lower morbidity and better outcomes than women who do not attempt labor. Women who undergo VBAC also avoid exposure to the significant risks of repeat cesarean deliveries in the long term.

Research unequivocally shows that the risk of placenta accreta, hysterectomy, hemorrhage, and other serious maternal morbidity increases progressively with each repeat cesarean delivery. Rates of placenta accreta have, in fact, been rising in the United States – a trend that should prompt us to think more about TOLAC.

Moreover, TOLAC is being shown to be a cost-effective strategy. In one analysis, TOLAC in a second pregnancy was cost-effective as long as the chance of VBAC exceeded approximately 74% (Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jun;97[6]:932-41). More recently, TOLAC was found to be cost-effective across a wide variety of circumstances, including when a woman had a probability of VBAC as low as 43%. The model in this analysis, which used probability estimates from the MFMU Cesarean Registry, took a longer-term view by including probabilities of outcomes throughout a woman’s reproductive life that were contingent upon her initial choice regarding TOLAC (Am J Perinatol. 2013 Jan;30[1]:11-20).

Likelihood of success

Evaluating and discussing the likelihood of success with TOLAC is therefore key to the counseling process. The higher the likelihood of achieving VBAC, the more favorable the risk-benefit ratio will be and the more appealing it will be to consider.

According to one analysis, if a woman undergoing a TOLAC has at least a 60%-70% chance of VBAC, her chance of having major or minor morbidity is no greater than a woman undergoing a planned repeat cesarean delivery (Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:56.e1-e6).

There are several prediction tools available that can be used at the first prenatal visit and in early labor to give a reasonably good estimate of success. One of these tools is available at the MFMU Network website (http://mfmu.bsc.gwu.edu). The tools take into account factors such as prior indication for cesarean delivery; history of vaginal delivery; demographic characteristics such as maternal age and body mass index; the occurrence of spontaneous labor; and cervical status at admission.

Prior vaginal delivery is one of the strongest predictors of a successful TOLAC. Research has consistently shown that women with a prior vaginal delivery – including a vaginal delivery predating an unsuccessful TOLAC – have significantly higher TOLAC success rates than women who did not have any prior vaginal delivery.

The indication for a prior cesarean delivery also clearly affects the likelihood of a successful TOLAC. Women whose first cesarean delivery was performed for a nonrecurring indication, such as breech presentation or low intolerance of labor, have TOLAC success rates that are similar to vaginal delivery rates for nulliparous women. Success rates for these women may exceed 85%. On the other hand, women who had a prior cesarean delivery for cephalopelvic disproportion or failure to progress have been shown to have lower TOLAC success rates ranging from 50%-67%.