User login

50 years of ob.gyn.: Embracing the ‘voice of the woman’

I hadn’t originally planned to be an obstetrician-gynecologist; in fact, I trained as an internist for 2 years. But as I became more exposed to the real-life experience of medical care, I realized that ob.gyn. would allow me to take care of women in all facets of their lives, from family planning to childbirth to endocrine problems and even depression.

Having joined the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 1965, my tenure as an ob.gyn. has spanned almost the exact length of this 50th anniversary retrospective of Ob.Gyn.News. But in my experience, those early days of my practice were actually the turning point for our specialty.

I’m an observer, not a historian. But I can’t imagine that any other specialty was more impacted by societal change in the mid-1960s than ours.

For one thing, when I was training, we were an overwhelmingly male group of residents who were learning about how to take care of women. Our commitment was not in question, but our ability to truly connect with women was certainly underdeveloped.

I’m gratified now to see that the demographics of ob.gyn. have changed, because they should. Without disrespecting my male ob.gyn. brethren, I was pleased to see that more than 80% of ob.gyn. trainees are now women. Importantly, many of them are learning now from female ob.gyns. This foretells a future in which connections between patient and physician are as strong as they should be.

Moreover, ob.gyn. trainees today have the highest proportions of African American and Hispanic trainees compared with any other specialty. We are doing a better job of representing, within our ranks, the women whom we treat. This continues to bolster our relationships, and in no other field is a trusting, intimate relationship as important as in ours.

Of course, the mid-1960s also heralded dramatic changes within reproductive health. Women were beginning to dip their toes into being able to control their own fertility and, in so doing, to prevent pregnancy. This also gave us the opportunity to focus on a woman’s greater well-being, helping her to address her own health before becoming pregnant. It pivoted the role of the ob.gyn. and charted us on a course to being, for many women, their primary point of care. And it gave women educational, professional, and economic opportunities the likes of which had never existed before.

Outside of fertility planning, we also began to make inroads in obstetric care – and to make some mistakes. The 1960s heralded some developments that we still embrace, but we also began a path toward dependence on technology and overinvasive care that we are trying to step away from today.

And, we had difficult conversations then that we have now. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

One of the most exciting, and essential, changes that I have seen since I began my career is the voice of the woman in ob.gyn. care. We speak with our patients. We screen them for depression and for intimate partner violence. We discuss their lives and whether they are using the birth control that is best for them. We try to reflect their own preferences in our approach to their labor and delivery. We missed an opportunity to do this in the past, to discuss a woman’s social history. We know now that there is more to a woman’s well-being than whether she smokes and drinks.

It makes sense that our specialty has changed, because we are the only specialty dedicated to women, and the last 50 years have brought about intense societal change for women.

We still have further to go. We can be slow to evolve, and we constantly face challenges that other specialties don’t confront. But I believe that the same dedication to women that inspired me to go into ob.gyn. 50 years ago is the same inspiration that is leading today’s trainees to do the same.

Dr. Pion is a clinical professor at the UCLA School of Medicine. He has served on the faculty of the University of Washington and the University of Hawaii, and worked for more than 25 years in the development and production of TV and radio programming on health care. He is a fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

I hadn’t originally planned to be an obstetrician-gynecologist; in fact, I trained as an internist for 2 years. But as I became more exposed to the real-life experience of medical care, I realized that ob.gyn. would allow me to take care of women in all facets of their lives, from family planning to childbirth to endocrine problems and even depression.

Having joined the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 1965, my tenure as an ob.gyn. has spanned almost the exact length of this 50th anniversary retrospective of Ob.Gyn.News. But in my experience, those early days of my practice were actually the turning point for our specialty.

I’m an observer, not a historian. But I can’t imagine that any other specialty was more impacted by societal change in the mid-1960s than ours.

For one thing, when I was training, we were an overwhelmingly male group of residents who were learning about how to take care of women. Our commitment was not in question, but our ability to truly connect with women was certainly underdeveloped.

I’m gratified now to see that the demographics of ob.gyn. have changed, because they should. Without disrespecting my male ob.gyn. brethren, I was pleased to see that more than 80% of ob.gyn. trainees are now women. Importantly, many of them are learning now from female ob.gyns. This foretells a future in which connections between patient and physician are as strong as they should be.

Moreover, ob.gyn. trainees today have the highest proportions of African American and Hispanic trainees compared with any other specialty. We are doing a better job of representing, within our ranks, the women whom we treat. This continues to bolster our relationships, and in no other field is a trusting, intimate relationship as important as in ours.

Of course, the mid-1960s also heralded dramatic changes within reproductive health. Women were beginning to dip their toes into being able to control their own fertility and, in so doing, to prevent pregnancy. This also gave us the opportunity to focus on a woman’s greater well-being, helping her to address her own health before becoming pregnant. It pivoted the role of the ob.gyn. and charted us on a course to being, for many women, their primary point of care. And it gave women educational, professional, and economic opportunities the likes of which had never existed before.

Outside of fertility planning, we also began to make inroads in obstetric care – and to make some mistakes. The 1960s heralded some developments that we still embrace, but we also began a path toward dependence on technology and overinvasive care that we are trying to step away from today.

And, we had difficult conversations then that we have now. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

One of the most exciting, and essential, changes that I have seen since I began my career is the voice of the woman in ob.gyn. care. We speak with our patients. We screen them for depression and for intimate partner violence. We discuss their lives and whether they are using the birth control that is best for them. We try to reflect their own preferences in our approach to their labor and delivery. We missed an opportunity to do this in the past, to discuss a woman’s social history. We know now that there is more to a woman’s well-being than whether she smokes and drinks.

It makes sense that our specialty has changed, because we are the only specialty dedicated to women, and the last 50 years have brought about intense societal change for women.

We still have further to go. We can be slow to evolve, and we constantly face challenges that other specialties don’t confront. But I believe that the same dedication to women that inspired me to go into ob.gyn. 50 years ago is the same inspiration that is leading today’s trainees to do the same.

Dr. Pion is a clinical professor at the UCLA School of Medicine. He has served on the faculty of the University of Washington and the University of Hawaii, and worked for more than 25 years in the development and production of TV and radio programming on health care. He is a fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

I hadn’t originally planned to be an obstetrician-gynecologist; in fact, I trained as an internist for 2 years. But as I became more exposed to the real-life experience of medical care, I realized that ob.gyn. would allow me to take care of women in all facets of their lives, from family planning to childbirth to endocrine problems and even depression.

Having joined the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 1965, my tenure as an ob.gyn. has spanned almost the exact length of this 50th anniversary retrospective of Ob.Gyn.News. But in my experience, those early days of my practice were actually the turning point for our specialty.

I’m an observer, not a historian. But I can’t imagine that any other specialty was more impacted by societal change in the mid-1960s than ours.

For one thing, when I was training, we were an overwhelmingly male group of residents who were learning about how to take care of women. Our commitment was not in question, but our ability to truly connect with women was certainly underdeveloped.

I’m gratified now to see that the demographics of ob.gyn. have changed, because they should. Without disrespecting my male ob.gyn. brethren, I was pleased to see that more than 80% of ob.gyn. trainees are now women. Importantly, many of them are learning now from female ob.gyns. This foretells a future in which connections between patient and physician are as strong as they should be.

Moreover, ob.gyn. trainees today have the highest proportions of African American and Hispanic trainees compared with any other specialty. We are doing a better job of representing, within our ranks, the women whom we treat. This continues to bolster our relationships, and in no other field is a trusting, intimate relationship as important as in ours.

Of course, the mid-1960s also heralded dramatic changes within reproductive health. Women were beginning to dip their toes into being able to control their own fertility and, in so doing, to prevent pregnancy. This also gave us the opportunity to focus on a woman’s greater well-being, helping her to address her own health before becoming pregnant. It pivoted the role of the ob.gyn. and charted us on a course to being, for many women, their primary point of care. And it gave women educational, professional, and economic opportunities the likes of which had never existed before.

Outside of fertility planning, we also began to make inroads in obstetric care – and to make some mistakes. The 1960s heralded some developments that we still embrace, but we also began a path toward dependence on technology and overinvasive care that we are trying to step away from today.

And, we had difficult conversations then that we have now. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

One of the most exciting, and essential, changes that I have seen since I began my career is the voice of the woman in ob.gyn. care. We speak with our patients. We screen them for depression and for intimate partner violence. We discuss their lives and whether they are using the birth control that is best for them. We try to reflect their own preferences in our approach to their labor and delivery. We missed an opportunity to do this in the past, to discuss a woman’s social history. We know now that there is more to a woman’s well-being than whether she smokes and drinks.

It makes sense that our specialty has changed, because we are the only specialty dedicated to women, and the last 50 years have brought about intense societal change for women.

We still have further to go. We can be slow to evolve, and we constantly face challenges that other specialties don’t confront. But I believe that the same dedication to women that inspired me to go into ob.gyn. 50 years ago is the same inspiration that is leading today’s trainees to do the same.

Dr. Pion is a clinical professor at the UCLA School of Medicine. He has served on the faculty of the University of Washington and the University of Hawaii, and worked for more than 25 years in the development and production of TV and radio programming on health care. He is a fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

A look back at 1966

As Ob.Gyn. News celebrates 50 years of publication, we’re taking a look back at our first year – 1966.

Not surprisingly, medicine looked a lot different in the mid-1960s, largely driven by the culture and technology of the time. A review of the 1966 issues of Obstetrics and Gynecology (the Green Journal), offers a snapshot of the state of the science.

With scientists still struggling to develop a rapid test to detect pregnancy, researchers from the Brookdale Hospital Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., detailed the possibility of using elevated breast temperature to get faster results. They compared 50 pregnant and 50 nonpregnant women and found a consistent rise in breast temperature in all pregnant women as early as 1 week after the first missed period. In the March issue, they concluded that the use of temperature difference between the breast and a baseline area on the anterior chest wall could be a rapid, simple, and accurate pregnancy test (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Mar;27[3]:378-80).

In August, researchers from Australia published promising data on the use of ultrasonic echoscopic examination of the uterus in late pregnancy. They found that the technology was useful in determining fetal position and possible abnormalities and could be repeated as often as necessary to observe changes and growth. The big advantage, they noted, would be the opportunity to avoid excessive fetal exposure to x-rays (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Aug;28[2]:164-9).

Advertising directed at physicians – in both the Green Journal and in Ob.Gyn. News – provided a glimpse into the practice of medicine at the time. Ob.gyns. saw ads for products such as Eskatrol – a capsule that contained dextroamphetamine sulfate and prochlorperazine – promoted to help women control appetite and “relieve the emotional stress that causes overeating.” And doctors also saw ads for oral contraceptives, first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1960.

Ob.gyn. practice was different culturally as well. In a regular column titled “After Office Hours,” published in the Green Journal in January 1966, Dr. Malcolm S. Allan explored a relatively new idea – husband-attended deliveries. Dr. Allan, of Wesson Maternity Hospital in Springfield, Mass., explained that his hospital had conducted a nationwide survey of chiefs of obstetrics after they received a petition seeking to allow husbands into the delivery room, as well as more flexibility for fathers to room in with the mother and baby. The survey, which included responses from 267 hospitals, showed that 81% of hospitals did not allow husbands in the delivery room (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Jan;27[1]:146-8).

After reviewing the survey results and talking to experts in the area, Dr. Allan and the leadership at Wesson decided not to allow husbands to witness deliveries. He concluded that “some patients in some of these ‘off-beat’ programs are being allowed to assume too much authority for determining the medical management of their pregnancies, while leaving the obstetrician with the responsibility for a healthy outcome.”

But in other ways, not much has changed since 1966. The March edition of “After Office Hours” bemoaned a looming manpower crisis in obstetrics (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Mar;27[3]:449-52). Dr. Jan Schneider of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote that even using conservative estimates of population growth, by 1970 there would be 20,000 obstetricians in the United States delivering on average of 225 babies each, a strain on the workforce. What were some of the factors? An uneven distribution of obstetricians throughout the country and increasing specialization.

In another familiar theme, Dr. Schneider urged physicians to consider team care as one part of the solution, allowing nurse midwives to provide prenatal care and perform normal deliveries under physician supervision.

Some of the clinical debates going on in 1966 are still unresolved. Consider the September 1966 issue of the Green Journal, which features an interim report on contraception with an intrauterine bow inserted immediately postpartum (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Sep;28[3]:329-31). Five decades later, only about 12 state Medicaid programs cover the cost of insertion of an IUD immediately postpartum. And in the August 1966 issue of the Green Journal, Dr. Carl J. Pauerstein asked, “Once a Section, Always a Trial of Labor?” (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Aug;28[2]:273-6). A look at the recent Master Class on vaginal birth after cesarean shows that those same questions are still being debated today.

So what will physicians and patients say about obstetrics and gynecology practice 50 years from now?

1966 at a glance

The Surgeon General

In a report to U.S. Surgeon General William H. Stewart titled “Protecting and Improving Health through the Radiological Sciences,” the National Advisory Committee on Radiation warned about emerging problems in the use of ionizing radiation in medicine.

Births

According to data provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 1966, there were 3.6 million births, for a birth rate of 18.4 and a fertility rate of 90.8; 8.4% of births were to unmarried women.

Women get organized

In June, Betty Friedan, Pauli Murray, and several other women launched the National Organization for Women at a conference in Washington, D.C., with Ms. Friedan famously writing N-O-W on a paper napkin.

Medical ethics

Dr. Henry K. Beecher published an article on ethics in the New England Journal of Medicine that is credited with spurring the federal government to set rules on human experimentation and informed consent, including establishment of Institutional Review Boards.

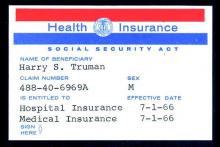

A safety net is born

On July 1, 1966, Medicare coverage began, with more than 19 million beneficiaries.

The AMA

The American Medical Association published the first edition of the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code book, creating a system of standardized terms for medical procedures used in documentation. Also in 1966, the AMA encouraged doctors to promote exercise to improve health.

Planned Parenthood

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America awarded its first Margaret Sanger Award. In 1966, four men received the award, including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Pregnancy testing

The first radioimmunoassay for hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) was described by A.R. Midgley, but the test could not distinguish between hCG and luteinizing hormone. A home pregnancy test was still a decade away.

Throughout 2016, Ob.Gyn. News will celebrate its 50th anniversary with exclusive articles looking at the evolution of the specialty, including the history of contraception, changes in gynecologic surgery, and the transformation of the well-woman visit. Look for these articles and more special features in the pages of Ob.Gyn. News and online at obgynnews.com.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

As Ob.Gyn. News celebrates 50 years of publication, we’re taking a look back at our first year – 1966.

Not surprisingly, medicine looked a lot different in the mid-1960s, largely driven by the culture and technology of the time. A review of the 1966 issues of Obstetrics and Gynecology (the Green Journal), offers a snapshot of the state of the science.

With scientists still struggling to develop a rapid test to detect pregnancy, researchers from the Brookdale Hospital Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., detailed the possibility of using elevated breast temperature to get faster results. They compared 50 pregnant and 50 nonpregnant women and found a consistent rise in breast temperature in all pregnant women as early as 1 week after the first missed period. In the March issue, they concluded that the use of temperature difference between the breast and a baseline area on the anterior chest wall could be a rapid, simple, and accurate pregnancy test (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Mar;27[3]:378-80).

In August, researchers from Australia published promising data on the use of ultrasonic echoscopic examination of the uterus in late pregnancy. They found that the technology was useful in determining fetal position and possible abnormalities and could be repeated as often as necessary to observe changes and growth. The big advantage, they noted, would be the opportunity to avoid excessive fetal exposure to x-rays (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Aug;28[2]:164-9).

Advertising directed at physicians – in both the Green Journal and in Ob.Gyn. News – provided a glimpse into the practice of medicine at the time. Ob.gyns. saw ads for products such as Eskatrol – a capsule that contained dextroamphetamine sulfate and prochlorperazine – promoted to help women control appetite and “relieve the emotional stress that causes overeating.” And doctors also saw ads for oral contraceptives, first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1960.

Ob.gyn. practice was different culturally as well. In a regular column titled “After Office Hours,” published in the Green Journal in January 1966, Dr. Malcolm S. Allan explored a relatively new idea – husband-attended deliveries. Dr. Allan, of Wesson Maternity Hospital in Springfield, Mass., explained that his hospital had conducted a nationwide survey of chiefs of obstetrics after they received a petition seeking to allow husbands into the delivery room, as well as more flexibility for fathers to room in with the mother and baby. The survey, which included responses from 267 hospitals, showed that 81% of hospitals did not allow husbands in the delivery room (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Jan;27[1]:146-8).

After reviewing the survey results and talking to experts in the area, Dr. Allan and the leadership at Wesson decided not to allow husbands to witness deliveries. He concluded that “some patients in some of these ‘off-beat’ programs are being allowed to assume too much authority for determining the medical management of their pregnancies, while leaving the obstetrician with the responsibility for a healthy outcome.”

But in other ways, not much has changed since 1966. The March edition of “After Office Hours” bemoaned a looming manpower crisis in obstetrics (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Mar;27[3]:449-52). Dr. Jan Schneider of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote that even using conservative estimates of population growth, by 1970 there would be 20,000 obstetricians in the United States delivering on average of 225 babies each, a strain on the workforce. What were some of the factors? An uneven distribution of obstetricians throughout the country and increasing specialization.

In another familiar theme, Dr. Schneider urged physicians to consider team care as one part of the solution, allowing nurse midwives to provide prenatal care and perform normal deliveries under physician supervision.

Some of the clinical debates going on in 1966 are still unresolved. Consider the September 1966 issue of the Green Journal, which features an interim report on contraception with an intrauterine bow inserted immediately postpartum (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Sep;28[3]:329-31). Five decades later, only about 12 state Medicaid programs cover the cost of insertion of an IUD immediately postpartum. And in the August 1966 issue of the Green Journal, Dr. Carl J. Pauerstein asked, “Once a Section, Always a Trial of Labor?” (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Aug;28[2]:273-6). A look at the recent Master Class on vaginal birth after cesarean shows that those same questions are still being debated today.

So what will physicians and patients say about obstetrics and gynecology practice 50 years from now?

1966 at a glance

The Surgeon General

In a report to U.S. Surgeon General William H. Stewart titled “Protecting and Improving Health through the Radiological Sciences,” the National Advisory Committee on Radiation warned about emerging problems in the use of ionizing radiation in medicine.

Births

According to data provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 1966, there were 3.6 million births, for a birth rate of 18.4 and a fertility rate of 90.8; 8.4% of births were to unmarried women.

Women get organized

In June, Betty Friedan, Pauli Murray, and several other women launched the National Organization for Women at a conference in Washington, D.C., with Ms. Friedan famously writing N-O-W on a paper napkin.

Medical ethics

Dr. Henry K. Beecher published an article on ethics in the New England Journal of Medicine that is credited with spurring the federal government to set rules on human experimentation and informed consent, including establishment of Institutional Review Boards.

A safety net is born

On July 1, 1966, Medicare coverage began, with more than 19 million beneficiaries.

The AMA

The American Medical Association published the first edition of the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code book, creating a system of standardized terms for medical procedures used in documentation. Also in 1966, the AMA encouraged doctors to promote exercise to improve health.

Planned Parenthood

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America awarded its first Margaret Sanger Award. In 1966, four men received the award, including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Pregnancy testing

The first radioimmunoassay for hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) was described by A.R. Midgley, but the test could not distinguish between hCG and luteinizing hormone. A home pregnancy test was still a decade away.

Throughout 2016, Ob.Gyn. News will celebrate its 50th anniversary with exclusive articles looking at the evolution of the specialty, including the history of contraception, changes in gynecologic surgery, and the transformation of the well-woman visit. Look for these articles and more special features in the pages of Ob.Gyn. News and online at obgynnews.com.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

As Ob.Gyn. News celebrates 50 years of publication, we’re taking a look back at our first year – 1966.

Not surprisingly, medicine looked a lot different in the mid-1960s, largely driven by the culture and technology of the time. A review of the 1966 issues of Obstetrics and Gynecology (the Green Journal), offers a snapshot of the state of the science.

With scientists still struggling to develop a rapid test to detect pregnancy, researchers from the Brookdale Hospital Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., detailed the possibility of using elevated breast temperature to get faster results. They compared 50 pregnant and 50 nonpregnant women and found a consistent rise in breast temperature in all pregnant women as early as 1 week after the first missed period. In the March issue, they concluded that the use of temperature difference between the breast and a baseline area on the anterior chest wall could be a rapid, simple, and accurate pregnancy test (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Mar;27[3]:378-80).

In August, researchers from Australia published promising data on the use of ultrasonic echoscopic examination of the uterus in late pregnancy. They found that the technology was useful in determining fetal position and possible abnormalities and could be repeated as often as necessary to observe changes and growth. The big advantage, they noted, would be the opportunity to avoid excessive fetal exposure to x-rays (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Aug;28[2]:164-9).

Advertising directed at physicians – in both the Green Journal and in Ob.Gyn. News – provided a glimpse into the practice of medicine at the time. Ob.gyns. saw ads for products such as Eskatrol – a capsule that contained dextroamphetamine sulfate and prochlorperazine – promoted to help women control appetite and “relieve the emotional stress that causes overeating.” And doctors also saw ads for oral contraceptives, first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1960.

Ob.gyn. practice was different culturally as well. In a regular column titled “After Office Hours,” published in the Green Journal in January 1966, Dr. Malcolm S. Allan explored a relatively new idea – husband-attended deliveries. Dr. Allan, of Wesson Maternity Hospital in Springfield, Mass., explained that his hospital had conducted a nationwide survey of chiefs of obstetrics after they received a petition seeking to allow husbands into the delivery room, as well as more flexibility for fathers to room in with the mother and baby. The survey, which included responses from 267 hospitals, showed that 81% of hospitals did not allow husbands in the delivery room (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Jan;27[1]:146-8).

After reviewing the survey results and talking to experts in the area, Dr. Allan and the leadership at Wesson decided not to allow husbands to witness deliveries. He concluded that “some patients in some of these ‘off-beat’ programs are being allowed to assume too much authority for determining the medical management of their pregnancies, while leaving the obstetrician with the responsibility for a healthy outcome.”

But in other ways, not much has changed since 1966. The March edition of “After Office Hours” bemoaned a looming manpower crisis in obstetrics (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Mar;27[3]:449-52). Dr. Jan Schneider of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote that even using conservative estimates of population growth, by 1970 there would be 20,000 obstetricians in the United States delivering on average of 225 babies each, a strain on the workforce. What were some of the factors? An uneven distribution of obstetricians throughout the country and increasing specialization.

In another familiar theme, Dr. Schneider urged physicians to consider team care as one part of the solution, allowing nurse midwives to provide prenatal care and perform normal deliveries under physician supervision.

Some of the clinical debates going on in 1966 are still unresolved. Consider the September 1966 issue of the Green Journal, which features an interim report on contraception with an intrauterine bow inserted immediately postpartum (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Sep;28[3]:329-31). Five decades later, only about 12 state Medicaid programs cover the cost of insertion of an IUD immediately postpartum. And in the August 1966 issue of the Green Journal, Dr. Carl J. Pauerstein asked, “Once a Section, Always a Trial of Labor?” (Obstet Gynecol. 1966 Aug;28[2]:273-6). A look at the recent Master Class on vaginal birth after cesarean shows that those same questions are still being debated today.

So what will physicians and patients say about obstetrics and gynecology practice 50 years from now?

1966 at a glance

The Surgeon General

In a report to U.S. Surgeon General William H. Stewart titled “Protecting and Improving Health through the Radiological Sciences,” the National Advisory Committee on Radiation warned about emerging problems in the use of ionizing radiation in medicine.

Births

According to data provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 1966, there were 3.6 million births, for a birth rate of 18.4 and a fertility rate of 90.8; 8.4% of births were to unmarried women.

Women get organized

In June, Betty Friedan, Pauli Murray, and several other women launched the National Organization for Women at a conference in Washington, D.C., with Ms. Friedan famously writing N-O-W on a paper napkin.

Medical ethics

Dr. Henry K. Beecher published an article on ethics in the New England Journal of Medicine that is credited with spurring the federal government to set rules on human experimentation and informed consent, including establishment of Institutional Review Boards.

A safety net is born

On July 1, 1966, Medicare coverage began, with more than 19 million beneficiaries.

The AMA

The American Medical Association published the first edition of the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code book, creating a system of standardized terms for medical procedures used in documentation. Also in 1966, the AMA encouraged doctors to promote exercise to improve health.

Planned Parenthood

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America awarded its first Margaret Sanger Award. In 1966, four men received the award, including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Pregnancy testing

The first radioimmunoassay for hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) was described by A.R. Midgley, but the test could not distinguish between hCG and luteinizing hormone. A home pregnancy test was still a decade away.

Throughout 2016, Ob.Gyn. News will celebrate its 50th anniversary with exclusive articles looking at the evolution of the specialty, including the history of contraception, changes in gynecologic surgery, and the transformation of the well-woman visit. Look for these articles and more special features in the pages of Ob.Gyn. News and online at obgynnews.com.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny