User login

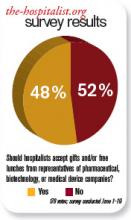

Should hospitalists accept gifts from pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotech companies?

Recent discussions on conflicts of interest in medical publications underscore the significance of the important yet fragile relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare professionals. Among these is an examination of how academic departments can maintain a relationship with the industry.1 This study suggests that if appropriate boundaries are established between industry and academia, it is possible to collaborate. However, part of the policy in this investigation included “elimination of industry-supplied meals, gifts, and favors.”2

The Institute of Medicine’s “Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice” included groundbreaking recommendations.3 Among them was a call for professionals to adopt a policy that prohibits “the acceptance of items of material value from pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology companies, except in specified situations.”3

Our nation has been embroiled in a healthcare debate. Questions of right versus privilege, access versus affordability, and, of course, the perpetual political overlay have monopolized most of the discourse. Some contend that healthcare reform will redefine the current relationship between pharma and physicians . . . and not a moment too soon.

Lest there be ambiguity, though, the medical profession remains a noble vocation. This notwithstanding, until 2002, physicians freely participated in golf outings, received athletic tickets, and dined at five-star restaurants. But after the pharmaceutical industry smartly adopted voluntary guidelines that restrict gifting to doctors, we are left with drug samples and, of course, the “free lunch.” Certainly, pharma can claim it has made significant contributions to furthering medical education and research. Many could argue the tangible negative effects that would follow if the funding suddenly were absent.

But let’s not kid ourselves: There is a good reason the pharmaceutical industry spends more than $12 billion per year on marketing to doctors.4 In 2006, Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) said, “It is obvious that drug companies provide these free lunches so their sales reps can get the doctor’s ear and influence the prescribing practices.”2 Most doctors would never admit any such influence. It would be, however, disingenuous for any practicing physician to say there is none.

A randomized trial conducted by Adair et al concluded the “access to drug samples in clinic influences resident prescribing decisions. This could affect resident education and increase drug costs for patients.”5 An earlier study by Chew et al concluded “the availability of drug samples led physicians to dispense and subsequently prescribe drugs that differ from their preferred drug choice. Physicians most often report using drug samples to avoid cost to the patient.”6

Sure, local culture drives some prescribing practice, but one must be mindful of the reality that the pharmaceutical industry has significant influence. Plus, free drug samples help patients in the short term. Once the samples are gone, an expensive prescription for that new drug will follow. It’s another win for the industry and another loss for the patient and the healthcare system.

Many studies have shown that gifting exerts influence, even if doctors are unwilling to admit it. But patients and doctors alike would like to state with clarity of conscience that the medication prescribed is only based on clinical evidence, not influence. TH

Dr. Pyke is a hospitalist at Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Systems in Mountain Top, Pa.

References

- Dubovsky SL, Kaye DL, Pristach CA, DelRegno P, Pessar L, Stiles K. Can academic departments maintain industry relationships while promoting physician professionalism? Acad Med. 2010;85(1):68-73.

- Salganik MW, Hopkins JS, Rockoff JD. Medical salesmen prescribe lunches. Catering trade feeds on rep-doctor meals. The Baltimore Sun. July 29, 2006.

- Institute of Medicine Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education and Practice Full Recommendations. 4-28-09.

- Wolfe SM. Why do American drug companies spend more than $12 billion a year pushing drugs? Is it education or promotion? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;11(10):637-639.

- Adair RF, Holmgren LR. Do drug samples influence resident prescribing behavior? A randomized trial. Am J Med. 2005;118(8):881-884.

- Chew LD, O’Young TS, Hazlet TK, Bradley KA, Maynard C, Lessler DS. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians’ behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(7):478-483.

Recent discussions on conflicts of interest in medical publications underscore the significance of the important yet fragile relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare professionals. Among these is an examination of how academic departments can maintain a relationship with the industry.1 This study suggests that if appropriate boundaries are established between industry and academia, it is possible to collaborate. However, part of the policy in this investigation included “elimination of industry-supplied meals, gifts, and favors.”2

The Institute of Medicine’s “Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice” included groundbreaking recommendations.3 Among them was a call for professionals to adopt a policy that prohibits “the acceptance of items of material value from pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology companies, except in specified situations.”3

Our nation has been embroiled in a healthcare debate. Questions of right versus privilege, access versus affordability, and, of course, the perpetual political overlay have monopolized most of the discourse. Some contend that healthcare reform will redefine the current relationship between pharma and physicians . . . and not a moment too soon.

Lest there be ambiguity, though, the medical profession remains a noble vocation. This notwithstanding, until 2002, physicians freely participated in golf outings, received athletic tickets, and dined at five-star restaurants. But after the pharmaceutical industry smartly adopted voluntary guidelines that restrict gifting to doctors, we are left with drug samples and, of course, the “free lunch.” Certainly, pharma can claim it has made significant contributions to furthering medical education and research. Many could argue the tangible negative effects that would follow if the funding suddenly were absent.

But let’s not kid ourselves: There is a good reason the pharmaceutical industry spends more than $12 billion per year on marketing to doctors.4 In 2006, Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) said, “It is obvious that drug companies provide these free lunches so their sales reps can get the doctor’s ear and influence the prescribing practices.”2 Most doctors would never admit any such influence. It would be, however, disingenuous for any practicing physician to say there is none.

A randomized trial conducted by Adair et al concluded the “access to drug samples in clinic influences resident prescribing decisions. This could affect resident education and increase drug costs for patients.”5 An earlier study by Chew et al concluded “the availability of drug samples led physicians to dispense and subsequently prescribe drugs that differ from their preferred drug choice. Physicians most often report using drug samples to avoid cost to the patient.”6

Sure, local culture drives some prescribing practice, but one must be mindful of the reality that the pharmaceutical industry has significant influence. Plus, free drug samples help patients in the short term. Once the samples are gone, an expensive prescription for that new drug will follow. It’s another win for the industry and another loss for the patient and the healthcare system.

Many studies have shown that gifting exerts influence, even if doctors are unwilling to admit it. But patients and doctors alike would like to state with clarity of conscience that the medication prescribed is only based on clinical evidence, not influence. TH

Dr. Pyke is a hospitalist at Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Systems in Mountain Top, Pa.

References

- Dubovsky SL, Kaye DL, Pristach CA, DelRegno P, Pessar L, Stiles K. Can academic departments maintain industry relationships while promoting physician professionalism? Acad Med. 2010;85(1):68-73.

- Salganik MW, Hopkins JS, Rockoff JD. Medical salesmen prescribe lunches. Catering trade feeds on rep-doctor meals. The Baltimore Sun. July 29, 2006.

- Institute of Medicine Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education and Practice Full Recommendations. 4-28-09.

- Wolfe SM. Why do American drug companies spend more than $12 billion a year pushing drugs? Is it education or promotion? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;11(10):637-639.

- Adair RF, Holmgren LR. Do drug samples influence resident prescribing behavior? A randomized trial. Am J Med. 2005;118(8):881-884.

- Chew LD, O’Young TS, Hazlet TK, Bradley KA, Maynard C, Lessler DS. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians’ behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(7):478-483.

Recent discussions on conflicts of interest in medical publications underscore the significance of the important yet fragile relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare professionals. Among these is an examination of how academic departments can maintain a relationship with the industry.1 This study suggests that if appropriate boundaries are established between industry and academia, it is possible to collaborate. However, part of the policy in this investigation included “elimination of industry-supplied meals, gifts, and favors.”2

The Institute of Medicine’s “Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice” included groundbreaking recommendations.3 Among them was a call for professionals to adopt a policy that prohibits “the acceptance of items of material value from pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology companies, except in specified situations.”3

Our nation has been embroiled in a healthcare debate. Questions of right versus privilege, access versus affordability, and, of course, the perpetual political overlay have monopolized most of the discourse. Some contend that healthcare reform will redefine the current relationship between pharma and physicians . . . and not a moment too soon.

Lest there be ambiguity, though, the medical profession remains a noble vocation. This notwithstanding, until 2002, physicians freely participated in golf outings, received athletic tickets, and dined at five-star restaurants. But after the pharmaceutical industry smartly adopted voluntary guidelines that restrict gifting to doctors, we are left with drug samples and, of course, the “free lunch.” Certainly, pharma can claim it has made significant contributions to furthering medical education and research. Many could argue the tangible negative effects that would follow if the funding suddenly were absent.

But let’s not kid ourselves: There is a good reason the pharmaceutical industry spends more than $12 billion per year on marketing to doctors.4 In 2006, Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) said, “It is obvious that drug companies provide these free lunches so their sales reps can get the doctor’s ear and influence the prescribing practices.”2 Most doctors would never admit any such influence. It would be, however, disingenuous for any practicing physician to say there is none.

A randomized trial conducted by Adair et al concluded the “access to drug samples in clinic influences resident prescribing decisions. This could affect resident education and increase drug costs for patients.”5 An earlier study by Chew et al concluded “the availability of drug samples led physicians to dispense and subsequently prescribe drugs that differ from their preferred drug choice. Physicians most often report using drug samples to avoid cost to the patient.”6

Sure, local culture drives some prescribing practice, but one must be mindful of the reality that the pharmaceutical industry has significant influence. Plus, free drug samples help patients in the short term. Once the samples are gone, an expensive prescription for that new drug will follow. It’s another win for the industry and another loss for the patient and the healthcare system.

Many studies have shown that gifting exerts influence, even if doctors are unwilling to admit it. But patients and doctors alike would like to state with clarity of conscience that the medication prescribed is only based on clinical evidence, not influence. TH

Dr. Pyke is a hospitalist at Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Systems in Mountain Top, Pa.

References

- Dubovsky SL, Kaye DL, Pristach CA, DelRegno P, Pessar L, Stiles K. Can academic departments maintain industry relationships while promoting physician professionalism? Acad Med. 2010;85(1):68-73.

- Salganik MW, Hopkins JS, Rockoff JD. Medical salesmen prescribe lunches. Catering trade feeds on rep-doctor meals. The Baltimore Sun. July 29, 2006.

- Institute of Medicine Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education and Practice Full Recommendations. 4-28-09.

- Wolfe SM. Why do American drug companies spend more than $12 billion a year pushing drugs? Is it education or promotion? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;11(10):637-639.

- Adair RF, Holmgren LR. Do drug samples influence resident prescribing behavior? A randomized trial. Am J Med. 2005;118(8):881-884.

- Chew LD, O’Young TS, Hazlet TK, Bradley KA, Maynard C, Lessler DS. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians’ behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(7):478-483.

Should hospitalists accept gifts from pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotech companies?

The pharmaceutical industry is big business, and its goal is to make money. If the industry can convince physicians to prescribe its medicines, then it makes more money.

Although pharmaceutical representatives brief physicians on new medications in an effort to encourage the use of their brand-name products, they also provide substantive information on the drugs that serves an educational purpose.

In the past, pharmaceutical companies—along with the medical device and biotechnology industries—showered physicians with expensive gifts, raising ethical questions about physicians’ obligation to the drug companies. Fair enough. These excessive practices were identified and curtailed—to my knowledge—some years ago.

Watchdog groups, however, have continued to call into question every suggestion of “being in the pay” of big pharma. Everything from a plastic pen to a piece of pizza is suspect. There is considerable concern that practicing clinicians are influenced by the smallest gesture, while many large medical institutions continue to accept pharmaceutical-company-funded research grants. If big-pharma investment in research does not corrupt institutions, why is it assumed that carrying a pharmaceutical pen has such a pernicious effect on clinicians?

As a corollary to this question, does anyone really want to discontinue these important research studies just because they are funded by industry dollars?

Listening to drug representatives—even being seen in the vicinity—raises the eyebrows of purists. Do we really want physicians completely divorced from all pharmaceutical company education and communication? Do we feel there is zero benefit to hearing about new medications from the company’s viewpoint?

If physicians completely shut out the representatives, it would be expected that pharmaceutical companies would direct their efforts elsewhere—most likely, to consumers. Is that a better and healthier scenario?

Clearly, there is potential for abuse in pharmaceutical gifts to physicians. The practice should be controlled and monitored. The suspicions raised by purist groups that physicians’ prescribing habits are unalterably biased after a five-minute pharmaceutical representative detail and a chicken sandwich is hyperbole. The voice of reason is silenced in the midst of the inquisition.

In the academic setting, fear of being accused of “bought bias” has physicians clearing their pockets of tainted pens and checking their desks for corrupting paraphernalia. The positive aspects of pharma-sponsored programs and medical lectures are lost for fear of appearing to be complicit with drug companies.

The Aristotelian Golden Mean is superior to extreme positions, and I submit that the best road is the center. Listen to what the drug company representatives have to say, just like you listen to a car salesman: You can learn from both—as long as you research the data and form your own opinion. TH

Dr. Brezina is a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital in North Carolina.

The pharmaceutical industry is big business, and its goal is to make money. If the industry can convince physicians to prescribe its medicines, then it makes more money.

Although pharmaceutical representatives brief physicians on new medications in an effort to encourage the use of their brand-name products, they also provide substantive information on the drugs that serves an educational purpose.

In the past, pharmaceutical companies—along with the medical device and biotechnology industries—showered physicians with expensive gifts, raising ethical questions about physicians’ obligation to the drug companies. Fair enough. These excessive practices were identified and curtailed—to my knowledge—some years ago.

Watchdog groups, however, have continued to call into question every suggestion of “being in the pay” of big pharma. Everything from a plastic pen to a piece of pizza is suspect. There is considerable concern that practicing clinicians are influenced by the smallest gesture, while many large medical institutions continue to accept pharmaceutical-company-funded research grants. If big-pharma investment in research does not corrupt institutions, why is it assumed that carrying a pharmaceutical pen has such a pernicious effect on clinicians?

As a corollary to this question, does anyone really want to discontinue these important research studies just because they are funded by industry dollars?

Listening to drug representatives—even being seen in the vicinity—raises the eyebrows of purists. Do we really want physicians completely divorced from all pharmaceutical company education and communication? Do we feel there is zero benefit to hearing about new medications from the company’s viewpoint?

If physicians completely shut out the representatives, it would be expected that pharmaceutical companies would direct their efforts elsewhere—most likely, to consumers. Is that a better and healthier scenario?

Clearly, there is potential for abuse in pharmaceutical gifts to physicians. The practice should be controlled and monitored. The suspicions raised by purist groups that physicians’ prescribing habits are unalterably biased after a five-minute pharmaceutical representative detail and a chicken sandwich is hyperbole. The voice of reason is silenced in the midst of the inquisition.

In the academic setting, fear of being accused of “bought bias” has physicians clearing their pockets of tainted pens and checking their desks for corrupting paraphernalia. The positive aspects of pharma-sponsored programs and medical lectures are lost for fear of appearing to be complicit with drug companies.

The Aristotelian Golden Mean is superior to extreme positions, and I submit that the best road is the center. Listen to what the drug company representatives have to say, just like you listen to a car salesman: You can learn from both—as long as you research the data and form your own opinion. TH

Dr. Brezina is a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital in North Carolina.

The pharmaceutical industry is big business, and its goal is to make money. If the industry can convince physicians to prescribe its medicines, then it makes more money.

Although pharmaceutical representatives brief physicians on new medications in an effort to encourage the use of their brand-name products, they also provide substantive information on the drugs that serves an educational purpose.

In the past, pharmaceutical companies—along with the medical device and biotechnology industries—showered physicians with expensive gifts, raising ethical questions about physicians’ obligation to the drug companies. Fair enough. These excessive practices were identified and curtailed—to my knowledge—some years ago.

Watchdog groups, however, have continued to call into question every suggestion of “being in the pay” of big pharma. Everything from a plastic pen to a piece of pizza is suspect. There is considerable concern that practicing clinicians are influenced by the smallest gesture, while many large medical institutions continue to accept pharmaceutical-company-funded research grants. If big-pharma investment in research does not corrupt institutions, why is it assumed that carrying a pharmaceutical pen has such a pernicious effect on clinicians?

As a corollary to this question, does anyone really want to discontinue these important research studies just because they are funded by industry dollars?

Listening to drug representatives—even being seen in the vicinity—raises the eyebrows of purists. Do we really want physicians completely divorced from all pharmaceutical company education and communication? Do we feel there is zero benefit to hearing about new medications from the company’s viewpoint?

If physicians completely shut out the representatives, it would be expected that pharmaceutical companies would direct their efforts elsewhere—most likely, to consumers. Is that a better and healthier scenario?

Clearly, there is potential for abuse in pharmaceutical gifts to physicians. The practice should be controlled and monitored. The suspicions raised by purist groups that physicians’ prescribing habits are unalterably biased after a five-minute pharmaceutical representative detail and a chicken sandwich is hyperbole. The voice of reason is silenced in the midst of the inquisition.

In the academic setting, fear of being accused of “bought bias” has physicians clearing their pockets of tainted pens and checking their desks for corrupting paraphernalia. The positive aspects of pharma-sponsored programs and medical lectures are lost for fear of appearing to be complicit with drug companies.

The Aristotelian Golden Mean is superior to extreme positions, and I submit that the best road is the center. Listen to what the drug company representatives have to say, just like you listen to a car salesman: You can learn from both—as long as you research the data and form your own opinion. TH

Dr. Brezina is a hospitalist at Durham Regional Hospital in North Carolina.

Playground Politics

Baseball, kick the can, Russian roulette—pick your game. Chances are good that it has worked its way into a metaphor to illustrate the infuriating, perplexing, and altogether frustrating inability of Congress to step up to the plate and pass a long-term fix to the broken sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula used to determine Medicare reimbursement rates.

On June 24, legislators avoided catastrophe by temporarily rescinding a 21.3% rate cut that went into effect June 1. The after-the-fact patch meant that some Medicare claims had to be reprocessed to recoup the full value, creating an administrative mess. The accompanying 2.2% rate increase expires Nov. 30. The reimbursement cut could reach nearly 30% next year unless Congress intervenes again.

“Obviously, there’s a lot of frustration around the issue, especially on the membership side,” says Ron Greeno, MD, FACP, SFHM, a member of SHM’s Public Policy and Leadership committees, and chief medical officer for Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent Healthcare. For hospitalists in many small private practices, he says, a major percentage of income comes from Medicare. “It’s a tremendous headache,” he says of the uncertainty. “It’s very hard to plan for. You’re trying to budget and you don’t know what the policy is going to be literally from week to week.”

The Blame Game

Despite the widespread sentiment among doctors that a permanent reimbursement rate fix should have been included in the healthcare reform legislation, skittishness over the price tag led legislators to drop it from the package. Based on last fall’s estimates, the total cost of a reform bill that scrapped the SGR would have ballooned by roughly $250 billion over 10 years, which would have threatened the bill’s passage.

But Congress has since been unable to pass a permanent fix as standalone legislation amid mounting concern over the national debt, and the price of inaction continues to rise. On April 30, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the cost of jettisoning the SGR formula and freezing rates at current levels had grown to $276 billion over 10 years.

Any serious consideration of lasting alternatives has now been pushed back to the lame-duck session, after the midterm elections. The can has been kicked down the road so many times, Dr. Greeno and others say, that most Congressional members have boot marks all over them. “So now you have a bigger problem at a more crucial time, when money is tighter than ever in a poor economy,” Dr. Greeno says. “And I just think it’s been a failure of our politicians.”

Other healthcare industry leaders have been just as critical. “Delaying the problem is not a solution,” said AMA President Cecil B. Wilson, MD, in a prepared statement after Congress passed the latest six-month reprieve in June. “It doesn’t solve the Medicare mess Congress has created with a long series of short-term Medicare patches over the last decade—including four to avert the 2010 cut alone.”

AMA-sponsored print ads have reminded legislators that delaying a fix until 2013 will again increase its cost, to $396 billion over 10 years. And the association’s June press release asserted that “Congress is playing a dangerous game of Russian roulette with seniors’ healthcare.”

Perhaps a game of “chicken” would be more apt.

Republicans have dared Democrats to spend the billions for a more lasting solution—in the absence of any cuts elsewhere in the healthcare delivery system—and be labeled as fiscally irresponsible. In turn, Democrats have dared Republicans to let the rate cut take effect and be labeled heartless as Medicare beneficiaries lose access to their healthcare providers.

Both parties blinked, resorting to almost unanimous short-term fixes that have allowed legislators to save face while putting off politically risky votes until after the November elections.

Lynne M. Allen, MN, ARNP, who works as a part-time hospitalist in hematology-oncology at 188-bed Kadlec Regional Medical Center in Richland, Wash., says she and other colleagues were initially hopeful that the Obama administration would make Congress work together to find a lasting solution. “There’s a sense of frustration because instead of that happening from our legislators, they’re playing a lot of games with the funding,” says Allen, a member of Team Hospitalist. “They’re not willing to step up to the plate, as they say, and make a decision that will allow us to go forward smoothly.”

The result, Allen says, has been a “roller-coaster ride” of uncertainty over reimbursements. Because Washington’s Tri-Cities region has a relatively high percentage of patients with private insurance, her hospital is somewhat cushioned from a precipitous drop in Medicare fees. But if CMS is ever forced to cut back on its rates, she fully expects private insurers to follow the same downward track.

Practical Concerns

Barbara Hartley, MD, a part-time hospitalist at 22-bed Benson Hospital in Benson, Ariz., says the town’s healthcare facility is somewhat protected from potential Medicare rate cuts through its official status as a Critical Access Hospital. Instead of being reimbursed through diagnosis-related group (DRG) codes, the rural hospital is repaid by Medicare for its total cost per day per patient.

The arrangement is a stable one at the moment, but not enough to dispel Dr. Hartley’s uneasy question: If the economy worsens, will Medicare be able to retain its commitment to rural hospitals? If not, the pain might be felt acutely in communities like Benson, where Dr. Hartley estimates that as much as 75% of the hospital’s in-patient business is through either Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan.

Kirk Mathews, CEO of St. Louis-based Inpatient Management Inc. and a member of SHM’s Public Policy and Practice Management committees, says Medicare rate cuts also could significantly reduce the leverage of hospitalists during contract negotiations.

“Even if we’re employed by the hospital, but our professional fees that the hospital can recoup for our services are dramatically affected, it will affect how those future contracts go,” Mathews says. “We might be insulated temporarily by the strength of our current contract. But if the formula—however that works out—dramatically impacts the hospitalist reimbursement on the professional fee side, the hospital will feel that, and then hospitalists will eventually feel that as well.” In other words, it could strengthen the bargaining hand of the hospital at the expense of the hospitalist. “Therein lies the long-term threat,” he points out.

Independent Solution?

Some of the authority over physician payments might eventually be depoliticized via language in the reform legislation that empowers a new entity, the Independent Payment Advisory Board, to create policy on such critical monetary issues as reimbursement rates. Congress could still override the board’s policy decisions, but only if the Congressional alternative saves just as much money.

In the meantime, the money for a fix still has to come from somewhere, and no consensus has emerged. Advocates likewise refuse to coalesce around any single alternative. Some experts favor a new formula based on the Medicare economic index, which measures inflation in healthcare delivery costs. But the CBO estimates that per-beneficiary spending under such a formula would be 30% more by 2016 than under the current formula. Other proposals call for temporarily increasing rates, then reverting to annual GDP growth, plus a bit more to cover physician costs.

No matter how the crisis is resolved, experts say, doctors almost certainly will have to make do with less. “When healthcare reform is finally fully implemented, there are going to be less dollars to pay for more services. It’s inevitable,” Mathews says. “And whether it takes the form of SGR or some other form, I’m afraid physicians are going to have to get used to having less money in the pool of money that’s allocated to pay providers.”

It could be a whole new ballgame. TH

Bryn Nelson, PhD, is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Baseball, kick the can, Russian roulette—pick your game. Chances are good that it has worked its way into a metaphor to illustrate the infuriating, perplexing, and altogether frustrating inability of Congress to step up to the plate and pass a long-term fix to the broken sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula used to determine Medicare reimbursement rates.

On June 24, legislators avoided catastrophe by temporarily rescinding a 21.3% rate cut that went into effect June 1. The after-the-fact patch meant that some Medicare claims had to be reprocessed to recoup the full value, creating an administrative mess. The accompanying 2.2% rate increase expires Nov. 30. The reimbursement cut could reach nearly 30% next year unless Congress intervenes again.

“Obviously, there’s a lot of frustration around the issue, especially on the membership side,” says Ron Greeno, MD, FACP, SFHM, a member of SHM’s Public Policy and Leadership committees, and chief medical officer for Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent Healthcare. For hospitalists in many small private practices, he says, a major percentage of income comes from Medicare. “It’s a tremendous headache,” he says of the uncertainty. “It’s very hard to plan for. You’re trying to budget and you don’t know what the policy is going to be literally from week to week.”

The Blame Game

Despite the widespread sentiment among doctors that a permanent reimbursement rate fix should have been included in the healthcare reform legislation, skittishness over the price tag led legislators to drop it from the package. Based on last fall’s estimates, the total cost of a reform bill that scrapped the SGR would have ballooned by roughly $250 billion over 10 years, which would have threatened the bill’s passage.

But Congress has since been unable to pass a permanent fix as standalone legislation amid mounting concern over the national debt, and the price of inaction continues to rise. On April 30, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the cost of jettisoning the SGR formula and freezing rates at current levels had grown to $276 billion over 10 years.

Any serious consideration of lasting alternatives has now been pushed back to the lame-duck session, after the midterm elections. The can has been kicked down the road so many times, Dr. Greeno and others say, that most Congressional members have boot marks all over them. “So now you have a bigger problem at a more crucial time, when money is tighter than ever in a poor economy,” Dr. Greeno says. “And I just think it’s been a failure of our politicians.”

Other healthcare industry leaders have been just as critical. “Delaying the problem is not a solution,” said AMA President Cecil B. Wilson, MD, in a prepared statement after Congress passed the latest six-month reprieve in June. “It doesn’t solve the Medicare mess Congress has created with a long series of short-term Medicare patches over the last decade—including four to avert the 2010 cut alone.”

AMA-sponsored print ads have reminded legislators that delaying a fix until 2013 will again increase its cost, to $396 billion over 10 years. And the association’s June press release asserted that “Congress is playing a dangerous game of Russian roulette with seniors’ healthcare.”

Perhaps a game of “chicken” would be more apt.

Republicans have dared Democrats to spend the billions for a more lasting solution—in the absence of any cuts elsewhere in the healthcare delivery system—and be labeled as fiscally irresponsible. In turn, Democrats have dared Republicans to let the rate cut take effect and be labeled heartless as Medicare beneficiaries lose access to their healthcare providers.

Both parties blinked, resorting to almost unanimous short-term fixes that have allowed legislators to save face while putting off politically risky votes until after the November elections.

Lynne M. Allen, MN, ARNP, who works as a part-time hospitalist in hematology-oncology at 188-bed Kadlec Regional Medical Center in Richland, Wash., says she and other colleagues were initially hopeful that the Obama administration would make Congress work together to find a lasting solution. “There’s a sense of frustration because instead of that happening from our legislators, they’re playing a lot of games with the funding,” says Allen, a member of Team Hospitalist. “They’re not willing to step up to the plate, as they say, and make a decision that will allow us to go forward smoothly.”

The result, Allen says, has been a “roller-coaster ride” of uncertainty over reimbursements. Because Washington’s Tri-Cities region has a relatively high percentage of patients with private insurance, her hospital is somewhat cushioned from a precipitous drop in Medicare fees. But if CMS is ever forced to cut back on its rates, she fully expects private insurers to follow the same downward track.

Practical Concerns

Barbara Hartley, MD, a part-time hospitalist at 22-bed Benson Hospital in Benson, Ariz., says the town’s healthcare facility is somewhat protected from potential Medicare rate cuts through its official status as a Critical Access Hospital. Instead of being reimbursed through diagnosis-related group (DRG) codes, the rural hospital is repaid by Medicare for its total cost per day per patient.

The arrangement is a stable one at the moment, but not enough to dispel Dr. Hartley’s uneasy question: If the economy worsens, will Medicare be able to retain its commitment to rural hospitals? If not, the pain might be felt acutely in communities like Benson, where Dr. Hartley estimates that as much as 75% of the hospital’s in-patient business is through either Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan.

Kirk Mathews, CEO of St. Louis-based Inpatient Management Inc. and a member of SHM’s Public Policy and Practice Management committees, says Medicare rate cuts also could significantly reduce the leverage of hospitalists during contract negotiations.

“Even if we’re employed by the hospital, but our professional fees that the hospital can recoup for our services are dramatically affected, it will affect how those future contracts go,” Mathews says. “We might be insulated temporarily by the strength of our current contract. But if the formula—however that works out—dramatically impacts the hospitalist reimbursement on the professional fee side, the hospital will feel that, and then hospitalists will eventually feel that as well.” In other words, it could strengthen the bargaining hand of the hospital at the expense of the hospitalist. “Therein lies the long-term threat,” he points out.

Independent Solution?

Some of the authority over physician payments might eventually be depoliticized via language in the reform legislation that empowers a new entity, the Independent Payment Advisory Board, to create policy on such critical monetary issues as reimbursement rates. Congress could still override the board’s policy decisions, but only if the Congressional alternative saves just as much money.

In the meantime, the money for a fix still has to come from somewhere, and no consensus has emerged. Advocates likewise refuse to coalesce around any single alternative. Some experts favor a new formula based on the Medicare economic index, which measures inflation in healthcare delivery costs. But the CBO estimates that per-beneficiary spending under such a formula would be 30% more by 2016 than under the current formula. Other proposals call for temporarily increasing rates, then reverting to annual GDP growth, plus a bit more to cover physician costs.

No matter how the crisis is resolved, experts say, doctors almost certainly will have to make do with less. “When healthcare reform is finally fully implemented, there are going to be less dollars to pay for more services. It’s inevitable,” Mathews says. “And whether it takes the form of SGR or some other form, I’m afraid physicians are going to have to get used to having less money in the pool of money that’s allocated to pay providers.”

It could be a whole new ballgame. TH

Bryn Nelson, PhD, is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Baseball, kick the can, Russian roulette—pick your game. Chances are good that it has worked its way into a metaphor to illustrate the infuriating, perplexing, and altogether frustrating inability of Congress to step up to the plate and pass a long-term fix to the broken sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula used to determine Medicare reimbursement rates.

On June 24, legislators avoided catastrophe by temporarily rescinding a 21.3% rate cut that went into effect June 1. The after-the-fact patch meant that some Medicare claims had to be reprocessed to recoup the full value, creating an administrative mess. The accompanying 2.2% rate increase expires Nov. 30. The reimbursement cut could reach nearly 30% next year unless Congress intervenes again.

“Obviously, there’s a lot of frustration around the issue, especially on the membership side,” says Ron Greeno, MD, FACP, SFHM, a member of SHM’s Public Policy and Leadership committees, and chief medical officer for Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent Healthcare. For hospitalists in many small private practices, he says, a major percentage of income comes from Medicare. “It’s a tremendous headache,” he says of the uncertainty. “It’s very hard to plan for. You’re trying to budget and you don’t know what the policy is going to be literally from week to week.”

The Blame Game

Despite the widespread sentiment among doctors that a permanent reimbursement rate fix should have been included in the healthcare reform legislation, skittishness over the price tag led legislators to drop it from the package. Based on last fall’s estimates, the total cost of a reform bill that scrapped the SGR would have ballooned by roughly $250 billion over 10 years, which would have threatened the bill’s passage.

But Congress has since been unable to pass a permanent fix as standalone legislation amid mounting concern over the national debt, and the price of inaction continues to rise. On April 30, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the cost of jettisoning the SGR formula and freezing rates at current levels had grown to $276 billion over 10 years.

Any serious consideration of lasting alternatives has now been pushed back to the lame-duck session, after the midterm elections. The can has been kicked down the road so many times, Dr. Greeno and others say, that most Congressional members have boot marks all over them. “So now you have a bigger problem at a more crucial time, when money is tighter than ever in a poor economy,” Dr. Greeno says. “And I just think it’s been a failure of our politicians.”

Other healthcare industry leaders have been just as critical. “Delaying the problem is not a solution,” said AMA President Cecil B. Wilson, MD, in a prepared statement after Congress passed the latest six-month reprieve in June. “It doesn’t solve the Medicare mess Congress has created with a long series of short-term Medicare patches over the last decade—including four to avert the 2010 cut alone.”

AMA-sponsored print ads have reminded legislators that delaying a fix until 2013 will again increase its cost, to $396 billion over 10 years. And the association’s June press release asserted that “Congress is playing a dangerous game of Russian roulette with seniors’ healthcare.”

Perhaps a game of “chicken” would be more apt.

Republicans have dared Democrats to spend the billions for a more lasting solution—in the absence of any cuts elsewhere in the healthcare delivery system—and be labeled as fiscally irresponsible. In turn, Democrats have dared Republicans to let the rate cut take effect and be labeled heartless as Medicare beneficiaries lose access to their healthcare providers.

Both parties blinked, resorting to almost unanimous short-term fixes that have allowed legislators to save face while putting off politically risky votes until after the November elections.

Lynne M. Allen, MN, ARNP, who works as a part-time hospitalist in hematology-oncology at 188-bed Kadlec Regional Medical Center in Richland, Wash., says she and other colleagues were initially hopeful that the Obama administration would make Congress work together to find a lasting solution. “There’s a sense of frustration because instead of that happening from our legislators, they’re playing a lot of games with the funding,” says Allen, a member of Team Hospitalist. “They’re not willing to step up to the plate, as they say, and make a decision that will allow us to go forward smoothly.”

The result, Allen says, has been a “roller-coaster ride” of uncertainty over reimbursements. Because Washington’s Tri-Cities region has a relatively high percentage of patients with private insurance, her hospital is somewhat cushioned from a precipitous drop in Medicare fees. But if CMS is ever forced to cut back on its rates, she fully expects private insurers to follow the same downward track.

Practical Concerns

Barbara Hartley, MD, a part-time hospitalist at 22-bed Benson Hospital in Benson, Ariz., says the town’s healthcare facility is somewhat protected from potential Medicare rate cuts through its official status as a Critical Access Hospital. Instead of being reimbursed through diagnosis-related group (DRG) codes, the rural hospital is repaid by Medicare for its total cost per day per patient.

The arrangement is a stable one at the moment, but not enough to dispel Dr. Hartley’s uneasy question: If the economy worsens, will Medicare be able to retain its commitment to rural hospitals? If not, the pain might be felt acutely in communities like Benson, where Dr. Hartley estimates that as much as 75% of the hospital’s in-patient business is through either Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan.

Kirk Mathews, CEO of St. Louis-based Inpatient Management Inc. and a member of SHM’s Public Policy and Practice Management committees, says Medicare rate cuts also could significantly reduce the leverage of hospitalists during contract negotiations.

“Even if we’re employed by the hospital, but our professional fees that the hospital can recoup for our services are dramatically affected, it will affect how those future contracts go,” Mathews says. “We might be insulated temporarily by the strength of our current contract. But if the formula—however that works out—dramatically impacts the hospitalist reimbursement on the professional fee side, the hospital will feel that, and then hospitalists will eventually feel that as well.” In other words, it could strengthen the bargaining hand of the hospital at the expense of the hospitalist. “Therein lies the long-term threat,” he points out.

Independent Solution?

Some of the authority over physician payments might eventually be depoliticized via language in the reform legislation that empowers a new entity, the Independent Payment Advisory Board, to create policy on such critical monetary issues as reimbursement rates. Congress could still override the board’s policy decisions, but only if the Congressional alternative saves just as much money.

In the meantime, the money for a fix still has to come from somewhere, and no consensus has emerged. Advocates likewise refuse to coalesce around any single alternative. Some experts favor a new formula based on the Medicare economic index, which measures inflation in healthcare delivery costs. But the CBO estimates that per-beneficiary spending under such a formula would be 30% more by 2016 than under the current formula. Other proposals call for temporarily increasing rates, then reverting to annual GDP growth, plus a bit more to cover physician costs.

No matter how the crisis is resolved, experts say, doctors almost certainly will have to make do with less. “When healthcare reform is finally fully implemented, there are going to be less dollars to pay for more services. It’s inevitable,” Mathews says. “And whether it takes the form of SGR or some other form, I’m afraid physicians are going to have to get used to having less money in the pool of money that’s allocated to pay providers.”

It could be a whole new ballgame. TH

Bryn Nelson, PhD, is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Rule Proposes Electronic Prescription of Controlled Substances, Doesn’t Scrap Pen-and-Paper Method

Is it true that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is going to allow doctors to prescribe controlled drugs electronically?

Will I still be able to prescribe on my prescription pads, or is this big government forcing me to use a computer for prescriptions?

J. Hockenstein, DO

Des Moines, Iowa

Dr. Hospitalist responds: On March 31, the DEA published in the Federal Register an interim final rule regarding the “electronic prescription for controlled substances.” (View the entire rule at www.gpoaccess.gov/fr.) The DEA is seeking comment on the proposed rule for the next 60 days. Some of us might remember that the DEA proposed a similar rule for electronic prescribing in June 2008, but that rule did not meet the security requirements already in place at federal healthcare facilities.

Under the current system, providers can create prescriptions electronically, but the prescription has to be printed on paper. The new rule proposes a system of true electronic prescribing; data can be transmitted electronically from the hospital or doctor’s office to the pharmacy without the use of a printer or fax.

This proposed rule does not eliminate the traditional method of paper and pen for prescriptions but allows providers the voluntary option of prescribing controlled substances electronically. This proposed rule also allows pharmacies to receive, dispense, and archive these electronic prescriptions.

For those providers who choose to prescribe electronically, there will be specific requirements to prevent diversion and maintain privacy. Providers must utilize software that meets the rule’s specific requirements. For example, the software system will require a two-step process to authenticate the prescribing provider. These measures might include a password, a token, or the use of biometric identifier (e.g., fingerprint or handprint). For some of us, this might sound space-aged, but such biometric systems are commonplace in other industries. For example, I provided my fingerprint as part of the test center security system when I checked in for my American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) recertification examination.

There are several other issues with the proposed rule that one should consider. The new proposal does not affect the existing rule regarding emergency prescriptions. The current law allows physicians to prescribe a Schedule II controlled substance by telephone and the pharmacist to dispense this substance, provided that the amount being dispensed is limited to what is reasonably required during the emergency time period and that the provider provides a hard copy of the prescription to the pharmacist within seven days of the telephone prescription. Under the proposed rule, providers will still be able to prescribe Schedule II substances by telephone under emergency situations but will have the option of providing an electronic copy of the prescription, rather than a paper one, within seven days.

There are other components of the proposed rule that could change your practice. The rule clearly states that an electronic prescription cannot be changed after transmission and that any change to the content of the prescription will render it invalid. This might be important in a handful of situations. For example, if the provider electronically prescribes a brand-name drug, the pharmacist would not be able to make a generic substitution.

Another component of the proposed rule is that it precludes the printing of an electronic prescription, which already has been transmitted and precludes the electronic transmission of a prescription that already has been printed. This situation might arise if the electronic prescription did not transmit due to a computer problem. The provider would not be able to print or fax a copy of the electronic prescription.

The proposed rule has the potential to reduce medical errors, reduce prescription forgeries, and help providers and hospitals integrate their medical records. True electronic prescribing is long overdue. In the future, I envision hospitalists prescribing from their handheld devices.

The key to success, like any computerized system, will be the ability to keep the system running and continuously maintaining and upgrading security measures. For more information regarding electronic prescriptions for controlled substances, visit www.DEAdiversion.usdoj.gov. TH

Is it true that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is going to allow doctors to prescribe controlled drugs electronically?

Will I still be able to prescribe on my prescription pads, or is this big government forcing me to use a computer for prescriptions?

J. Hockenstein, DO

Des Moines, Iowa

Dr. Hospitalist responds: On March 31, the DEA published in the Federal Register an interim final rule regarding the “electronic prescription for controlled substances.” (View the entire rule at www.gpoaccess.gov/fr.) The DEA is seeking comment on the proposed rule for the next 60 days. Some of us might remember that the DEA proposed a similar rule for electronic prescribing in June 2008, but that rule did not meet the security requirements already in place at federal healthcare facilities.

Under the current system, providers can create prescriptions electronically, but the prescription has to be printed on paper. The new rule proposes a system of true electronic prescribing; data can be transmitted electronically from the hospital or doctor’s office to the pharmacy without the use of a printer or fax.

This proposed rule does not eliminate the traditional method of paper and pen for prescriptions but allows providers the voluntary option of prescribing controlled substances electronically. This proposed rule also allows pharmacies to receive, dispense, and archive these electronic prescriptions.

For those providers who choose to prescribe electronically, there will be specific requirements to prevent diversion and maintain privacy. Providers must utilize software that meets the rule’s specific requirements. For example, the software system will require a two-step process to authenticate the prescribing provider. These measures might include a password, a token, or the use of biometric identifier (e.g., fingerprint or handprint). For some of us, this might sound space-aged, but such biometric systems are commonplace in other industries. For example, I provided my fingerprint as part of the test center security system when I checked in for my American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) recertification examination.

There are several other issues with the proposed rule that one should consider. The new proposal does not affect the existing rule regarding emergency prescriptions. The current law allows physicians to prescribe a Schedule II controlled substance by telephone and the pharmacist to dispense this substance, provided that the amount being dispensed is limited to what is reasonably required during the emergency time period and that the provider provides a hard copy of the prescription to the pharmacist within seven days of the telephone prescription. Under the proposed rule, providers will still be able to prescribe Schedule II substances by telephone under emergency situations but will have the option of providing an electronic copy of the prescription, rather than a paper one, within seven days.

There are other components of the proposed rule that could change your practice. The rule clearly states that an electronic prescription cannot be changed after transmission and that any change to the content of the prescription will render it invalid. This might be important in a handful of situations. For example, if the provider electronically prescribes a brand-name drug, the pharmacist would not be able to make a generic substitution.

Another component of the proposed rule is that it precludes the printing of an electronic prescription, which already has been transmitted and precludes the electronic transmission of a prescription that already has been printed. This situation might arise if the electronic prescription did not transmit due to a computer problem. The provider would not be able to print or fax a copy of the electronic prescription.

The proposed rule has the potential to reduce medical errors, reduce prescription forgeries, and help providers and hospitals integrate their medical records. True electronic prescribing is long overdue. In the future, I envision hospitalists prescribing from their handheld devices.

The key to success, like any computerized system, will be the ability to keep the system running and continuously maintaining and upgrading security measures. For more information regarding electronic prescriptions for controlled substances, visit www.DEAdiversion.usdoj.gov. TH

Is it true that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is going to allow doctors to prescribe controlled drugs electronically?

Will I still be able to prescribe on my prescription pads, or is this big government forcing me to use a computer for prescriptions?

J. Hockenstein, DO

Des Moines, Iowa

Dr. Hospitalist responds: On March 31, the DEA published in the Federal Register an interim final rule regarding the “electronic prescription for controlled substances.” (View the entire rule at www.gpoaccess.gov/fr.) The DEA is seeking comment on the proposed rule for the next 60 days. Some of us might remember that the DEA proposed a similar rule for electronic prescribing in June 2008, but that rule did not meet the security requirements already in place at federal healthcare facilities.

Under the current system, providers can create prescriptions electronically, but the prescription has to be printed on paper. The new rule proposes a system of true electronic prescribing; data can be transmitted electronically from the hospital or doctor’s office to the pharmacy without the use of a printer or fax.

This proposed rule does not eliminate the traditional method of paper and pen for prescriptions but allows providers the voluntary option of prescribing controlled substances electronically. This proposed rule also allows pharmacies to receive, dispense, and archive these electronic prescriptions.

For those providers who choose to prescribe electronically, there will be specific requirements to prevent diversion and maintain privacy. Providers must utilize software that meets the rule’s specific requirements. For example, the software system will require a two-step process to authenticate the prescribing provider. These measures might include a password, a token, or the use of biometric identifier (e.g., fingerprint or handprint). For some of us, this might sound space-aged, but such biometric systems are commonplace in other industries. For example, I provided my fingerprint as part of the test center security system when I checked in for my American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) recertification examination.

There are several other issues with the proposed rule that one should consider. The new proposal does not affect the existing rule regarding emergency prescriptions. The current law allows physicians to prescribe a Schedule II controlled substance by telephone and the pharmacist to dispense this substance, provided that the amount being dispensed is limited to what is reasonably required during the emergency time period and that the provider provides a hard copy of the prescription to the pharmacist within seven days of the telephone prescription. Under the proposed rule, providers will still be able to prescribe Schedule II substances by telephone under emergency situations but will have the option of providing an electronic copy of the prescription, rather than a paper one, within seven days.

There are other components of the proposed rule that could change your practice. The rule clearly states that an electronic prescription cannot be changed after transmission and that any change to the content of the prescription will render it invalid. This might be important in a handful of situations. For example, if the provider electronically prescribes a brand-name drug, the pharmacist would not be able to make a generic substitution.

Another component of the proposed rule is that it precludes the printing of an electronic prescription, which already has been transmitted and precludes the electronic transmission of a prescription that already has been printed. This situation might arise if the electronic prescription did not transmit due to a computer problem. The provider would not be able to print or fax a copy of the electronic prescription.

The proposed rule has the potential to reduce medical errors, reduce prescription forgeries, and help providers and hospitals integrate their medical records. True electronic prescribing is long overdue. In the future, I envision hospitalists prescribing from their handheld devices.

The key to success, like any computerized system, will be the ability to keep the system running and continuously maintaining and upgrading security measures. For more information regarding electronic prescriptions for controlled substances, visit www.DEAdiversion.usdoj.gov. TH

Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Worth the Additional Cost

Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Worth the Additional Cost

Why are we being required to fork over an extra $380 for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine MOC? This feels like the icing on the cake of already a major ripoff.

Dr. Ragan

Grass Valley, Calif.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Thank you for your frank reaction to the much-anticipated American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. As you noted, an additional fee is required to participate in this recertification program.

To my knowledge, any and all fees associated with recertification are paid to ABIM. No other organization benefits from the added cost, so your question might be more appropriately addressed to ABIM (see “Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine,” May 2010, p. 1). But because you asked the question, I am happy to respond with my thoughts.

Participation in the FPHM MOC program is not mandatory. I am not aware of any organization that is requiring hospitalists to participate. I don’t expect that your lack of participation will affect your ability to obtain hospital privileges. Like any new MOC program, I would expect some up-front administrative costs associated with developing and administering the practice-improvement modules and the secure examination.

It’s up to you and others to decide whether this added recognition is worth the cost. I can tell you that I have made the decision to participate. I fully expect to be part of the inaugural class of ABIM diplomates with this added recognition by the end of the year.

What went into my own decision to participate? I can tell you that I am a practicing hospitalist who makes a salary typical of most hospitalists. I am frugal with my money and certainly do not view the added cost as an insignificant amount of money. Like most hospitalists, I am not only busy with my professional life, but I have plenty of family commitments as well.

I expect the exam will be rigorous, and the requirements of the practice-improvement modules will be demanding. I would not want it any other way. In the fast-changing healthcare environment, I believe that hospitalists will be challenged to think about what it means to care for a hospitalized patient. To succeed in the future, hospitalists will be expected to not only participate, but also lead QI efforts at their institutions. The FPHM MOC will distinguish me as a hospitalist with added qualifications in the field of QI.

So how about it, Dr. Ragan? Will you join me?

What Certification Requirements Should a Hospitalist Program Have for Its Physicians?

I hope you can help me with some questions I have concerning starting a hospitalist program at my medical center. Are there certain requirements (e.g., board certification in internal medicine, ACLS, etc.) that need to be met, or is that up to the facility? The physician interested in the position is board-certified in infectious disease. Any direction you can give me on this would be greatly appreciated.

Marisa Sellers,

Medical Staff Coordinator,

Hartselle Medical Center,

Hartselle, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Congratulations on your medical center’s decision to establish a hospitalist program. Over the past decade, HM has been the fastest-growing field in all of American medicine. The majority of the country’s acute-care hospitals have hospitalists on staff.

Approximately 85% of the country’s hospitalists received training in internal medicine. Most of the other hospitalists received training in pediatrics or family medicine. While most hospitalists are general internists, some also have additional subspecialty training, which seems to be the case of the physician at your medical center. As you know, different medical facilities have different requirements of their medical staff. At the acute-care hospital where I work clinically, maintenance of board certification is required of all medical staff. I know that is not the case for all hospitals, yet I’m not aware of any hospitals with hospitalist-specific medical staff requirements.

Most of the hospitalists who are internists will be either board-eligible or board-certified with the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). You should be aware that ABIM has developed a new program, the Recognition of Focused Practice (RFP) in Hospital Medicine. As part of this maintenance of certification (MOC) program, ABIM diplomates will have the opportunity to take the first ABIM Hospital Medicine examination in October. For more information about this exam, ABIM’s rationale for recognizing a focused practice in HM, and any other questions about this program, please visit the ABIM Web site at www.abim.org/news/news/focused-

practice-hospital-medicine-qa.aspx.

I have heard from hospitalists trained as family physicians who are interested in RFP as hospitalists. It is my understanding that the American Board of Family Medicine is studying the ABIM program and working to develop a similar program for hospitalists with family medicine board certifications.

Regarding your question about hospitalists and the American Heart Association’s advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) training and certification: While I think it is a great idea for hospitalists to receive this training and maintain this certification, I am not aware of any mandate for hospitalists to be uniformly ACLS-certified. I think this is an issue the medical staff at your medical center will have to decide; basically, what is in the best interests of your patients?

Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Worth the Additional Cost

Why are we being required to fork over an extra $380 for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine MOC? This feels like the icing on the cake of already a major ripoff.

Dr. Ragan

Grass Valley, Calif.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Thank you for your frank reaction to the much-anticipated American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. As you noted, an additional fee is required to participate in this recertification program.

To my knowledge, any and all fees associated with recertification are paid to ABIM. No other organization benefits from the added cost, so your question might be more appropriately addressed to ABIM (see “Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine,” May 2010, p. 1). But because you asked the question, I am happy to respond with my thoughts.

Participation in the FPHM MOC program is not mandatory. I am not aware of any organization that is requiring hospitalists to participate. I don’t expect that your lack of participation will affect your ability to obtain hospital privileges. Like any new MOC program, I would expect some up-front administrative costs associated with developing and administering the practice-improvement modules and the secure examination.

It’s up to you and others to decide whether this added recognition is worth the cost. I can tell you that I have made the decision to participate. I fully expect to be part of the inaugural class of ABIM diplomates with this added recognition by the end of the year.

What went into my own decision to participate? I can tell you that I am a practicing hospitalist who makes a salary typical of most hospitalists. I am frugal with my money and certainly do not view the added cost as an insignificant amount of money. Like most hospitalists, I am not only busy with my professional life, but I have plenty of family commitments as well.

I expect the exam will be rigorous, and the requirements of the practice-improvement modules will be demanding. I would not want it any other way. In the fast-changing healthcare environment, I believe that hospitalists will be challenged to think about what it means to care for a hospitalized patient. To succeed in the future, hospitalists will be expected to not only participate, but also lead QI efforts at their institutions. The FPHM MOC will distinguish me as a hospitalist with added qualifications in the field of QI.

So how about it, Dr. Ragan? Will you join me?

What Certification Requirements Should a Hospitalist Program Have for Its Physicians?

I hope you can help me with some questions I have concerning starting a hospitalist program at my medical center. Are there certain requirements (e.g., board certification in internal medicine, ACLS, etc.) that need to be met, or is that up to the facility? The physician interested in the position is board-certified in infectious disease. Any direction you can give me on this would be greatly appreciated.

Marisa Sellers,

Medical Staff Coordinator,

Hartselle Medical Center,

Hartselle, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Congratulations on your medical center’s decision to establish a hospitalist program. Over the past decade, HM has been the fastest-growing field in all of American medicine. The majority of the country’s acute-care hospitals have hospitalists on staff.

Approximately 85% of the country’s hospitalists received training in internal medicine. Most of the other hospitalists received training in pediatrics or family medicine. While most hospitalists are general internists, some also have additional subspecialty training, which seems to be the case of the physician at your medical center. As you know, different medical facilities have different requirements of their medical staff. At the acute-care hospital where I work clinically, maintenance of board certification is required of all medical staff. I know that is not the case for all hospitals, yet I’m not aware of any hospitals with hospitalist-specific medical staff requirements.

Most of the hospitalists who are internists will be either board-eligible or board-certified with the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). You should be aware that ABIM has developed a new program, the Recognition of Focused Practice (RFP) in Hospital Medicine. As part of this maintenance of certification (MOC) program, ABIM diplomates will have the opportunity to take the first ABIM Hospital Medicine examination in October. For more information about this exam, ABIM’s rationale for recognizing a focused practice in HM, and any other questions about this program, please visit the ABIM Web site at www.abim.org/news/news/focused-

practice-hospital-medicine-qa.aspx.

I have heard from hospitalists trained as family physicians who are interested in RFP as hospitalists. It is my understanding that the American Board of Family Medicine is studying the ABIM program and working to develop a similar program for hospitalists with family medicine board certifications.

Regarding your question about hospitalists and the American Heart Association’s advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) training and certification: While I think it is a great idea for hospitalists to receive this training and maintain this certification, I am not aware of any mandate for hospitalists to be uniformly ACLS-certified. I think this is an issue the medical staff at your medical center will have to decide; basically, what is in the best interests of your patients?

Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Worth the Additional Cost

Why are we being required to fork over an extra $380 for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine MOC? This feels like the icing on the cake of already a major ripoff.

Dr. Ragan

Grass Valley, Calif.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Thank you for your frank reaction to the much-anticipated American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. As you noted, an additional fee is required to participate in this recertification program.

To my knowledge, any and all fees associated with recertification are paid to ABIM. No other organization benefits from the added cost, so your question might be more appropriately addressed to ABIM (see “Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine,” May 2010, p. 1). But because you asked the question, I am happy to respond with my thoughts.

Participation in the FPHM MOC program is not mandatory. I am not aware of any organization that is requiring hospitalists to participate. I don’t expect that your lack of participation will affect your ability to obtain hospital privileges. Like any new MOC program, I would expect some up-front administrative costs associated with developing and administering the practice-improvement modules and the secure examination.

It’s up to you and others to decide whether this added recognition is worth the cost. I can tell you that I have made the decision to participate. I fully expect to be part of the inaugural class of ABIM diplomates with this added recognition by the end of the year.

What went into my own decision to participate? I can tell you that I am a practicing hospitalist who makes a salary typical of most hospitalists. I am frugal with my money and certainly do not view the added cost as an insignificant amount of money. Like most hospitalists, I am not only busy with my professional life, but I have plenty of family commitments as well.

I expect the exam will be rigorous, and the requirements of the practice-improvement modules will be demanding. I would not want it any other way. In the fast-changing healthcare environment, I believe that hospitalists will be challenged to think about what it means to care for a hospitalized patient. To succeed in the future, hospitalists will be expected to not only participate, but also lead QI efforts at their institutions. The FPHM MOC will distinguish me as a hospitalist with added qualifications in the field of QI.

So how about it, Dr. Ragan? Will you join me?

What Certification Requirements Should a Hospitalist Program Have for Its Physicians?

I hope you can help me with some questions I have concerning starting a hospitalist program at my medical center. Are there certain requirements (e.g., board certification in internal medicine, ACLS, etc.) that need to be met, or is that up to the facility? The physician interested in the position is board-certified in infectious disease. Any direction you can give me on this would be greatly appreciated.

Marisa Sellers,

Medical Staff Coordinator,

Hartselle Medical Center,

Hartselle, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Congratulations on your medical center’s decision to establish a hospitalist program. Over the past decade, HM has been the fastest-growing field in all of American medicine. The majority of the country’s acute-care hospitals have hospitalists on staff.

Approximately 85% of the country’s hospitalists received training in internal medicine. Most of the other hospitalists received training in pediatrics or family medicine. While most hospitalists are general internists, some also have additional subspecialty training, which seems to be the case of the physician at your medical center. As you know, different medical facilities have different requirements of their medical staff. At the acute-care hospital where I work clinically, maintenance of board certification is required of all medical staff. I know that is not the case for all hospitals, yet I’m not aware of any hospitals with hospitalist-specific medical staff requirements.

Most of the hospitalists who are internists will be either board-eligible or board-certified with the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). You should be aware that ABIM has developed a new program, the Recognition of Focused Practice (RFP) in Hospital Medicine. As part of this maintenance of certification (MOC) program, ABIM diplomates will have the opportunity to take the first ABIM Hospital Medicine examination in October. For more information about this exam, ABIM’s rationale for recognizing a focused practice in HM, and any other questions about this program, please visit the ABIM Web site at www.abim.org/news/news/focused-

practice-hospital-medicine-qa.aspx.

I have heard from hospitalists trained as family physicians who are interested in RFP as hospitalists. It is my understanding that the American Board of Family Medicine is studying the ABIM program and working to develop a similar program for hospitalists with family medicine board certifications.

Regarding your question about hospitalists and the American Heart Association’s advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) training and certification: While I think it is a great idea for hospitalists to receive this training and maintain this certification, I am not aware of any mandate for hospitalists to be uniformly ACLS-certified. I think this is an issue the medical staff at your medical center will have to decide; basically, what is in the best interests of your patients?

What I Learned

As I write, I’m fighting the jet stream from Washington, D.C., to Denver, midflight on my return from HM10. I’m 30,000 feet above the ground—literally and figuratively—my mind spinning with the thoughts, ideas, and memories from the largest gathering of hospitalists ever. In the end, 2,500 hospitalists descended on our nation’s capital. Shrouded by the din of healthcare reform, we discussed, deliberated, and discovered what’s new in the clinical, political, and programmatic world of HM. Out of this churn, I learned a lot. Here’s but a small sample.

Smart People = Smart Solutions

I learned that if you put really smart people in a room and give them a problem to grapple with, they come up with really smart solutions. At the inaugural Academic Hospital Medicine Leadership Summit, 100 of the brightest, most influential academic hospitalists convened to tackle the problems facing our field.

The output was an amazing crop of inventive ideas aimed at taming the vexing issues surrounding clinical sustainability, academic viability, and career satisfaction. SHM leadership has heard the cry and promises to work closely with the academic community to transform these smart solutions into future initiatives.

Hospitalists Support Healthcare Reform, Should Collude with Hospitals