User login

Low-Level Laser (Light) Therapy (LLLT) in Skin: Stimulating, Healing, Restoring

Pinar Avci, MD, Asheesh Gupta, PhD, Magesh Sadasivam, MTech, Daniela Vecchio, PhD, Zeev Pam, MD, Nadav Pam, MD, and Michael R. Hamblin, PhD

Low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) is a fast-growing technology used to treat a multitude of conditions that require stimulation of healing, relief of pain and inflammation, and restoration of function. Although skin is naturally exposed to light more than any other organ, it still responds well to red and near-infrared wavelengths. The photons are absorbed by mitochondrial chromophores in skin cells. Consequently, electron transport, adenosine triphosphate nitric oxide release, blood flow, reactive oxygen species increase, and diverse signaling pathways are activated. Stem cells can be activated, allowing increased tissue repair and healing. In dermatology, LLLT has beneficial effects on wrinkles, acne scars, hypertrophic scars, and healing of burns. LLLT can reduce UV damage both as a treatment and as a prophylactic measure. In pigmentary disorders such as vitiligo, LLLT can increase pigmentation by stimulating melanocyte proliferation and reduce depigmentation by inhibiting autoimmunity. Inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis and acne can also be managed. The noninvasive nature and almost complete absence of side effects encourage further testing in dermatology.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Pinar Avci, MD, Asheesh Gupta, PhD, Magesh Sadasivam, MTech, Daniela Vecchio, PhD, Zeev Pam, MD, Nadav Pam, MD, and Michael R. Hamblin, PhD

Low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) is a fast-growing technology used to treat a multitude of conditions that require stimulation of healing, relief of pain and inflammation, and restoration of function. Although skin is naturally exposed to light more than any other organ, it still responds well to red and near-infrared wavelengths. The photons are absorbed by mitochondrial chromophores in skin cells. Consequently, electron transport, adenosine triphosphate nitric oxide release, blood flow, reactive oxygen species increase, and diverse signaling pathways are activated. Stem cells can be activated, allowing increased tissue repair and healing. In dermatology, LLLT has beneficial effects on wrinkles, acne scars, hypertrophic scars, and healing of burns. LLLT can reduce UV damage both as a treatment and as a prophylactic measure. In pigmentary disorders such as vitiligo, LLLT can increase pigmentation by stimulating melanocyte proliferation and reduce depigmentation by inhibiting autoimmunity. Inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis and acne can also be managed. The noninvasive nature and almost complete absence of side effects encourage further testing in dermatology.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Pinar Avci, MD, Asheesh Gupta, PhD, Magesh Sadasivam, MTech, Daniela Vecchio, PhD, Zeev Pam, MD, Nadav Pam, MD, and Michael R. Hamblin, PhD

Low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) is a fast-growing technology used to treat a multitude of conditions that require stimulation of healing, relief of pain and inflammation, and restoration of function. Although skin is naturally exposed to light more than any other organ, it still responds well to red and near-infrared wavelengths. The photons are absorbed by mitochondrial chromophores in skin cells. Consequently, electron transport, adenosine triphosphate nitric oxide release, blood flow, reactive oxygen species increase, and diverse signaling pathways are activated. Stem cells can be activated, allowing increased tissue repair and healing. In dermatology, LLLT has beneficial effects on wrinkles, acne scars, hypertrophic scars, and healing of burns. LLLT can reduce UV damage both as a treatment and as a prophylactic measure. In pigmentary disorders such as vitiligo, LLLT can increase pigmentation by stimulating melanocyte proliferation and reduce depigmentation by inhibiting autoimmunity. Inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis and acne can also be managed. The noninvasive nature and almost complete absence of side effects encourage further testing in dermatology.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

The New Age of Noninvasive Facial Rejuvenation

Rebecca Kleinerman, MD, Daniel B. Eisen, MD, Suzanne L. Kilmer, MD, and

Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD

The techniques of noninvasive facial rejuvenation are forever being redefined and improved. This article will review historical as well as present approaches to resurfacing, discussing the nonablative tools that can complement resurfacing procedures. Current thoughts on the pre- and postoperative care of resurfacing patients are also considered.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Rebecca Kleinerman, MD, Daniel B. Eisen, MD, Suzanne L. Kilmer, MD, and

Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD

The techniques of noninvasive facial rejuvenation are forever being redefined and improved. This article will review historical as well as present approaches to resurfacing, discussing the nonablative tools that can complement resurfacing procedures. Current thoughts on the pre- and postoperative care of resurfacing patients are also considered.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Rebecca Kleinerman, MD, Daniel B. Eisen, MD, Suzanne L. Kilmer, MD, and

Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD

The techniques of noninvasive facial rejuvenation are forever being redefined and improved. This article will review historical as well as present approaches to resurfacing, discussing the nonablative tools that can complement resurfacing procedures. Current thoughts on the pre- and postoperative care of resurfacing patients are also considered.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

This review will discuss historical aspects and current ideas in laser resurfacing, including the pre- and postoperative management of resurfacing patients, combination treatments, and advances in the nonablative modalities used adjunctively to combat the components of aging.

The Future of Noninvasive Procedural Dermatology

Murad Alam, MD, MSCI

Noninvasive procedural dermatology has evolved rapidly during the past decade. An array of skin tightening, resurfacing, and fat-reducing energy devices can now be combined with filler and neurotoxin injectables to reduce the visible signs of aging with minimal downtime and risk. In the future, such advances will likely continue, although the pace of technological breakthroughs is difficult to predict. Complex feedback devices, nanotechnology, and cell-based therapies will eventually begin to fulfill the promise of scar removal, pigmentation correction, and replacement of aged skin with skin that is new and completely functional. Dermatologists are well equipped to retain their leadership in noninvasive esthetic medicine, and they will, to the extent that they continue to pioneer outstanding therapies that are effective, affordable, and safe.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Murad Alam, MD, MSCI

Noninvasive procedural dermatology has evolved rapidly during the past decade. An array of skin tightening, resurfacing, and fat-reducing energy devices can now be combined with filler and neurotoxin injectables to reduce the visible signs of aging with minimal downtime and risk. In the future, such advances will likely continue, although the pace of technological breakthroughs is difficult to predict. Complex feedback devices, nanotechnology, and cell-based therapies will eventually begin to fulfill the promise of scar removal, pigmentation correction, and replacement of aged skin with skin that is new and completely functional. Dermatologists are well equipped to retain their leadership in noninvasive esthetic medicine, and they will, to the extent that they continue to pioneer outstanding therapies that are effective, affordable, and safe.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Murad Alam, MD, MSCI

Noninvasive procedural dermatology has evolved rapidly during the past decade. An array of skin tightening, resurfacing, and fat-reducing energy devices can now be combined with filler and neurotoxin injectables to reduce the visible signs of aging with minimal downtime and risk. In the future, such advances will likely continue, although the pace of technological breakthroughs is difficult to predict. Complex feedback devices, nanotechnology, and cell-based therapies will eventually begin to fulfill the promise of scar removal, pigmentation correction, and replacement of aged skin with skin that is new and completely functional. Dermatologists are well equipped to retain their leadership in noninvasive esthetic medicine, and they will, to the extent that they continue to pioneer outstanding therapies that are effective, affordable, and safe.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on OTC Acne Preparations

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top OTC acne preparations. Consideration must be given to:

- Acne Free Oil-Free Acne Cleanser

Valeant Consumer Products, a division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America

Recommended by Adam Friedman, MD, New York, New York

Clear Pore Cleanser/Mask

Neutrogena Corporation

Recommended by Adam Friedman, MD, New York, New York, and Marian Northington, MD, Birmingham, Alabama

"I combine Acne Free Oil-Free Acne Cleanser with benzoyl peroxide 3.7% or Neutrogena Clear Pore Cleanser/Mask with benzoyl peroxide 3.5% with subsequent application of clindamycin lotion, which limits the associated irritation often experienced with leave-on benzoyl peroxide products or combination products containing benzoyl peroxide while limiting bacterial resistance to the topical clindamycin and providing an antiacne impact. Of note, a wash-off product with benzoyl peroxide also limits the risk for clothing and towel bleaching often seen with leave-on products."—Adam Friedman, MD

- EndZit Products

Abbe Laboratories, Inc

Recommended by Deborah S. Sarnoff, MD, New York, New York

- Glytone Acne Treatment Line

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique

Recommended by Marta I. Rendon, MD, Boca Raton, Florida

- PanOxyl 10% Acne Foaming Wash

Stiefel, a GSK company

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- St. Ives Apricot Face Wash Blemish & Blackhead Control

Unilever

"This is an exfoliating 2% salicylic acid facial scrub, which is great to add into one's acne treatment. It can be used once or twice a week as a gentle keratolytic, helping to prevent comedone formation."—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Body moisturizers, face washes, and antiwrinkle treatments will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to msteiger@frontlinemedcom.com.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top OTC acne preparations. Consideration must be given to:

- Acne Free Oil-Free Acne Cleanser

Valeant Consumer Products, a division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America

Recommended by Adam Friedman, MD, New York, New York

Clear Pore Cleanser/Mask

Neutrogena Corporation

Recommended by Adam Friedman, MD, New York, New York, and Marian Northington, MD, Birmingham, Alabama

"I combine Acne Free Oil-Free Acne Cleanser with benzoyl peroxide 3.7% or Neutrogena Clear Pore Cleanser/Mask with benzoyl peroxide 3.5% with subsequent application of clindamycin lotion, which limits the associated irritation often experienced with leave-on benzoyl peroxide products or combination products containing benzoyl peroxide while limiting bacterial resistance to the topical clindamycin and providing an antiacne impact. Of note, a wash-off product with benzoyl peroxide also limits the risk for clothing and towel bleaching often seen with leave-on products."—Adam Friedman, MD

- EndZit Products

Abbe Laboratories, Inc

Recommended by Deborah S. Sarnoff, MD, New York, New York

- Glytone Acne Treatment Line

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique

Recommended by Marta I. Rendon, MD, Boca Raton, Florida

- PanOxyl 10% Acne Foaming Wash

Stiefel, a GSK company

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- St. Ives Apricot Face Wash Blemish & Blackhead Control

Unilever

"This is an exfoliating 2% salicylic acid facial scrub, which is great to add into one's acne treatment. It can be used once or twice a week as a gentle keratolytic, helping to prevent comedone formation."—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Body moisturizers, face washes, and antiwrinkle treatments will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to msteiger@frontlinemedcom.com.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top OTC acne preparations. Consideration must be given to:

- Acne Free Oil-Free Acne Cleanser

Valeant Consumer Products, a division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America

Recommended by Adam Friedman, MD, New York, New York

Clear Pore Cleanser/Mask

Neutrogena Corporation

Recommended by Adam Friedman, MD, New York, New York, and Marian Northington, MD, Birmingham, Alabama

"I combine Acne Free Oil-Free Acne Cleanser with benzoyl peroxide 3.7% or Neutrogena Clear Pore Cleanser/Mask with benzoyl peroxide 3.5% with subsequent application of clindamycin lotion, which limits the associated irritation often experienced with leave-on benzoyl peroxide products or combination products containing benzoyl peroxide while limiting bacterial resistance to the topical clindamycin and providing an antiacne impact. Of note, a wash-off product with benzoyl peroxide also limits the risk for clothing and towel bleaching often seen with leave-on products."—Adam Friedman, MD

- EndZit Products

Abbe Laboratories, Inc

Recommended by Deborah S. Sarnoff, MD, New York, New York

- Glytone Acne Treatment Line

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique

Recommended by Marta I. Rendon, MD, Boca Raton, Florida

- PanOxyl 10% Acne Foaming Wash

Stiefel, a GSK company

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- St. Ives Apricot Face Wash Blemish & Blackhead Control

Unilever

"This is an exfoliating 2% salicylic acid facial scrub, which is great to add into one's acne treatment. It can be used once or twice a week as a gentle keratolytic, helping to prevent comedone formation."—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Body moisturizers, face washes, and antiwrinkle treatments will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to msteiger@frontlinemedcom.com.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Ceramides

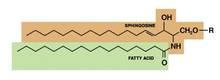

Structured in lamellar sheets, the primary lipids of the epidermis – ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids – play a crucial role in the barrier function of the skin. Ceramides have come to be known as a complex family of lipids (sphingolipids – a sphingoid base and a fatty acid) involved in cell signaling in addition to their role in barrier homeostasis and water retention. In fact, ceramides are known to play a critical role in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;47:681-6). Significantly, they cannot be replenished or obtained through natural sources, but synthetic ceramides, studied since the 1950s, are increasingly sophisticated and useful.

This column will review some key aspects of natural human ceramides as well as topically applied synthetic versions (also known as pseudoceramides), which are thought to ameliorate the structure and function of ceramide-depleted skin.

Ceramide structure and function

Lipids in the stratum corneum (SC) play an important role in the barrier function of the skin. The intercellular lipids of the SC are thought to be composed of approximately equal proportions of ceramides (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1987;88:2s-6s), cholesterol, and fatty acids (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2003;4:107-29). Ceramides are not found in significant supply in lower levels of the epidermis, such as the stratum granulosum or basal layer. This implies that terminal differentiation is an important component of the natural production of ceramides, of which there are at least nine classes in the SC. Ceramide 1 was first identified in 1982. In addition to ceramides 1 to 9, there are two protein-bound ceramides classified as ceramides A and B, which are covalently bound to cornified envelope proteins, such as involucrin (Bouwstra JA, Pilgrim K, Ponec M. Structure of the skin barrier, in "Skin Barrier," Elias PM, Feingold KR, Eds. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2006, p. 65) .

Ceramides are named based on the polarity and composition of the molecule. As suggested above, the foundational ceramide structure is a fatty acid covalently bound to a sphingoid base. The various classes of ceramides are grouped according to the arrangements of sphingosine (S), phytosphingosine (P), or 6-hydroxysphingosine (H) bases, to which an alpha-hydroxy (A) or nonhydroxy (N) fatty acid is attached, in addition to the presence or absence of a discrete omega-esterified linoleic acid residue (J. Lipid. Res. 2004;45:923-32).

Ceramide 1 is unique in that it is nonpolar, and it contains linoleic acid. The special function of ceramide 1 in the SC is typically ascribed to its unique structure, which is thought to allow it to act as a molecular rivet, binding the multiple bilayers of the SC (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1987;88:2s-6s). This would explain the stacking of lipid bilayers in lamellar sheets observed in the barrier. Ceramides 1, 4, and 7 exhibit critical functions in terms of epidermal integrity by serving as the primary storage areas for linoleic acid, an essential fatty acid with significant roles in the epidermal lipid barrier (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1980;74:230-3). Although all epidermal ceramides are produced from a lamellar body–derived glucosylceramide precursor, sphingomyelin-derived ceramides (ceramides 2 and 5) are essential for maintaining the integrity of the SC (J. Lipid. Res. 2000;41:2071-82). It is worth noting that because an alkaline pH suppresses beta-glucocerebrosidase and acid sphingomyelinase activity (J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005;125:510-20), alkaline soaps can exacerbate poor barrier formation.

Exposure to UVB radiation and cytokines has been associated with an increase in the regulatory enzyme for ceramide synthesis, serine palmitoyltransferase, and it has been determined that in response to UVB exposure, the epidermis upregulates sphingolipid synthesis at the mRNA and protein levels (J. Lipid. Res. 1998;39:2031-8).

Synthetic ceramides

Skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and some genetic disorders have been associated with depleted ceramide levels (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2005;6:215-23), but these diseases can be ameliorated through the use of exogenous ceramides or their analogues (topical ceramide replacement therapy) (Curr. Med. Chem. 2010;17:2301-24; J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008;51:37-43; Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2005;6:215-23). Notably, the activities of enzymes in the SC, particularly ceramidase, sphingomyelin deacylase, and glucosylceramide deacylase, have been shown to be elevated in epidermal AD (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2005;6:215-23).

Synthetic ceramides, or pseudoceramides, contain hydroxyl groups, two alkyl groups, and an amide bond – the same key structural components as natural ceramides. Consequently, various synthetic ceramides have been reported to form the multilamellar structure observed in the intercellular spaces of the SC (J. Lipid. Res. 1996;37:361-7).

Coderch et al., in a review of ceramides and skin function, endorsed the potential of topical therapy for several skin conditions using complete lipid mixtures and some ceramide supplementation, as well as the topical delivery of lipid precursors (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2003;4:107-29). And, in fact, the topical application of synthetic ceramides has been shown to speed up the repair of impaired SC (J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94:89-96; Dermatology 2005;211:128-34). Recent reports by Tokudome et al. also indicate that the application of sphingomyelin-based liposomes effectively augments the levels of various ceramides in cultured human skin models (Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2011;24:218-23; J. Liposome Res. 2010;20:49-54).

In 2005, de Jager et al. used small-angle and wide-angle x-ray diffraction to show that lipid mixtures prepared with well-defined synthetic ceramides exhibit organization and lipid-phase behavior that are very similar to those of lamellar and lateral SC lipids, and can be used to further elucidate the molecular structure and roles of individual ceramides (J. Lipid. Res. 2005;46:2649-56).

In light of the uncertainty regarding the metabolic impact of pseudoceramides, in 2008, Uchida et al. compared the effects of two chemically unrelated, commercially available products to exogenous cell-permeant or natural ceramide on cell growth and apoptosis thresholds. Using cultured human keratinocytes, the investigators found that the commercial ceramides did not suppress keratinocyte growth or increase cell toxicity, as did the cell-permeant. The investigators suggested that these findings buttress the preclinical studies indicating that these pseudoceramides are safe for topical application (J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008;51:37-43).

Kang et al. recently conducted studies of synthetic ceramide derivatives of PC-9S (N-ethanol-2-mirystyl-3-oxostearamide), which, itself, has been shown to be effective in atopic and psoriatic patients. Both studies, conducted in NC/Nga mice, demonstrated that the topical application of the derivative K6PC-9 or the derivative K6PC-9p reduced skin inflammation and AD symptoms. According to the authors, K6PC-9 warrants consideration as a topical agent for AD, and K6PC-9p warrants consideration as a treatment for inflammatory skin diseases in general (Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:1589-97; Exp. Dermatol. 2008;17:958-64).

Subsequently, Kang et al. studied the effects of another ceramide derivative of PC-9S, K112PC-5 (2-acetyl-N-(1,3-dihydroxyisopropyl)tetradecanamide), on macrophage and T-lymphocyte function in primary macrophages and splenocytes, respectively. The researchers also studied the impact of topically applied K112PC-5 on skin inflammation and AD in NC/Nga mice. Among several findings, the investigators noted that K112PC-5 suppressed AD induced by extracts of dust mites, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae, with the pseudoceramide exhibiting in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity. They concluded that K112PC-5 is another synthetic ceramide derivative with potential as a topical agent for the treatment of AD (Arch. Pharm. Res. 2008;31:1004-9).

In 2009, Morita et al. studied the potential adverse effects of the synthetic pseudoceramide SLE66, which has demonstrated the capacity to improve xerosis, pruritus, and scaling of human skin. They found that the tested product failed to provoke cutaneous irritation or sensitization in animal and human studies. In addition, they did not observe any phototoxicity or photosensitization, and they established 1,000 mg/kg/day (the highest level tested) as the no-observed-adverse-effect (NOAEL) for systemic toxicity after oral administration or topical application (Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;47:669-73).

Conclusion

Ceramides are among the primary lipid constituents, along with cholesterol and fatty acids, of the lamellar sheets found in the intercellular spaces of the SC. Together, these lipids maintain the water permeability barrier role of the skin. Ceramides also play an important role in cell signaling. Research over the last several decades, particularly the last 20 years, indicates that topically applied synthetic ceramide agents can effectively compensate for diminished ceramide levels associated with various skin conditions.

Dr. Baumann is in private practice in Miami Beach. She did not disclose any conflicts of interest. To respond to this column, or to suggest topics for future columns, write to her at sknews@elsevier.com.

Structured in lamellar sheets, the primary lipids of the epidermis – ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids – play a crucial role in the barrier function of the skin. Ceramides have come to be known as a complex family of lipids (sphingolipids – a sphingoid base and a fatty acid) involved in cell signaling in addition to their role in barrier homeostasis and water retention. In fact, ceramides are known to play a critical role in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;47:681-6). Significantly, they cannot be replenished or obtained through natural sources, but synthetic ceramides, studied since the 1950s, are increasingly sophisticated and useful.

This column will review some key aspects of natural human ceramides as well as topically applied synthetic versions (also known as pseudoceramides), which are thought to ameliorate the structure and function of ceramide-depleted skin.

Ceramide structure and function

Lipids in the stratum corneum (SC) play an important role in the barrier function of the skin. The intercellular lipids of the SC are thought to be composed of approximately equal proportions of ceramides (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1987;88:2s-6s), cholesterol, and fatty acids (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2003;4:107-29). Ceramides are not found in significant supply in lower levels of the epidermis, such as the stratum granulosum or basal layer. This implies that terminal differentiation is an important component of the natural production of ceramides, of which there are at least nine classes in the SC. Ceramide 1 was first identified in 1982. In addition to ceramides 1 to 9, there are two protein-bound ceramides classified as ceramides A and B, which are covalently bound to cornified envelope proteins, such as involucrin (Bouwstra JA, Pilgrim K, Ponec M. Structure of the skin barrier, in "Skin Barrier," Elias PM, Feingold KR, Eds. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2006, p. 65) .

Ceramides are named based on the polarity and composition of the molecule. As suggested above, the foundational ceramide structure is a fatty acid covalently bound to a sphingoid base. The various classes of ceramides are grouped according to the arrangements of sphingosine (S), phytosphingosine (P), or 6-hydroxysphingosine (H) bases, to which an alpha-hydroxy (A) or nonhydroxy (N) fatty acid is attached, in addition to the presence or absence of a discrete omega-esterified linoleic acid residue (J. Lipid. Res. 2004;45:923-32).

Ceramide 1 is unique in that it is nonpolar, and it contains linoleic acid. The special function of ceramide 1 in the SC is typically ascribed to its unique structure, which is thought to allow it to act as a molecular rivet, binding the multiple bilayers of the SC (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1987;88:2s-6s). This would explain the stacking of lipid bilayers in lamellar sheets observed in the barrier. Ceramides 1, 4, and 7 exhibit critical functions in terms of epidermal integrity by serving as the primary storage areas for linoleic acid, an essential fatty acid with significant roles in the epidermal lipid barrier (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1980;74:230-3). Although all epidermal ceramides are produced from a lamellar body–derived glucosylceramide precursor, sphingomyelin-derived ceramides (ceramides 2 and 5) are essential for maintaining the integrity of the SC (J. Lipid. Res. 2000;41:2071-82). It is worth noting that because an alkaline pH suppresses beta-glucocerebrosidase and acid sphingomyelinase activity (J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005;125:510-20), alkaline soaps can exacerbate poor barrier formation.

Exposure to UVB radiation and cytokines has been associated with an increase in the regulatory enzyme for ceramide synthesis, serine palmitoyltransferase, and it has been determined that in response to UVB exposure, the epidermis upregulates sphingolipid synthesis at the mRNA and protein levels (J. Lipid. Res. 1998;39:2031-8).

Synthetic ceramides

Skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and some genetic disorders have been associated with depleted ceramide levels (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2005;6:215-23), but these diseases can be ameliorated through the use of exogenous ceramides or their analogues (topical ceramide replacement therapy) (Curr. Med. Chem. 2010;17:2301-24; J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008;51:37-43; Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2005;6:215-23). Notably, the activities of enzymes in the SC, particularly ceramidase, sphingomyelin deacylase, and glucosylceramide deacylase, have been shown to be elevated in epidermal AD (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2005;6:215-23).

Synthetic ceramides, or pseudoceramides, contain hydroxyl groups, two alkyl groups, and an amide bond – the same key structural components as natural ceramides. Consequently, various synthetic ceramides have been reported to form the multilamellar structure observed in the intercellular spaces of the SC (J. Lipid. Res. 1996;37:361-7).

Coderch et al., in a review of ceramides and skin function, endorsed the potential of topical therapy for several skin conditions using complete lipid mixtures and some ceramide supplementation, as well as the topical delivery of lipid precursors (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2003;4:107-29). And, in fact, the topical application of synthetic ceramides has been shown to speed up the repair of impaired SC (J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94:89-96; Dermatology 2005;211:128-34). Recent reports by Tokudome et al. also indicate that the application of sphingomyelin-based liposomes effectively augments the levels of various ceramides in cultured human skin models (Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2011;24:218-23; J. Liposome Res. 2010;20:49-54).

In 2005, de Jager et al. used small-angle and wide-angle x-ray diffraction to show that lipid mixtures prepared with well-defined synthetic ceramides exhibit organization and lipid-phase behavior that are very similar to those of lamellar and lateral SC lipids, and can be used to further elucidate the molecular structure and roles of individual ceramides (J. Lipid. Res. 2005;46:2649-56).

In light of the uncertainty regarding the metabolic impact of pseudoceramides, in 2008, Uchida et al. compared the effects of two chemically unrelated, commercially available products to exogenous cell-permeant or natural ceramide on cell growth and apoptosis thresholds. Using cultured human keratinocytes, the investigators found that the commercial ceramides did not suppress keratinocyte growth or increase cell toxicity, as did the cell-permeant. The investigators suggested that these findings buttress the preclinical studies indicating that these pseudoceramides are safe for topical application (J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008;51:37-43).

Kang et al. recently conducted studies of synthetic ceramide derivatives of PC-9S (N-ethanol-2-mirystyl-3-oxostearamide), which, itself, has been shown to be effective in atopic and psoriatic patients. Both studies, conducted in NC/Nga mice, demonstrated that the topical application of the derivative K6PC-9 or the derivative K6PC-9p reduced skin inflammation and AD symptoms. According to the authors, K6PC-9 warrants consideration as a topical agent for AD, and K6PC-9p warrants consideration as a treatment for inflammatory skin diseases in general (Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:1589-97; Exp. Dermatol. 2008;17:958-64).

Subsequently, Kang et al. studied the effects of another ceramide derivative of PC-9S, K112PC-5 (2-acetyl-N-(1,3-dihydroxyisopropyl)tetradecanamide), on macrophage and T-lymphocyte function in primary macrophages and splenocytes, respectively. The researchers also studied the impact of topically applied K112PC-5 on skin inflammation and AD in NC/Nga mice. Among several findings, the investigators noted that K112PC-5 suppressed AD induced by extracts of dust mites, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae, with the pseudoceramide exhibiting in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity. They concluded that K112PC-5 is another synthetic ceramide derivative with potential as a topical agent for the treatment of AD (Arch. Pharm. Res. 2008;31:1004-9).

In 2009, Morita et al. studied the potential adverse effects of the synthetic pseudoceramide SLE66, which has demonstrated the capacity to improve xerosis, pruritus, and scaling of human skin. They found that the tested product failed to provoke cutaneous irritation or sensitization in animal and human studies. In addition, they did not observe any phototoxicity or photosensitization, and they established 1,000 mg/kg/day (the highest level tested) as the no-observed-adverse-effect (NOAEL) for systemic toxicity after oral administration or topical application (Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;47:669-73).

Conclusion

Ceramides are among the primary lipid constituents, along with cholesterol and fatty acids, of the lamellar sheets found in the intercellular spaces of the SC. Together, these lipids maintain the water permeability barrier role of the skin. Ceramides also play an important role in cell signaling. Research over the last several decades, particularly the last 20 years, indicates that topically applied synthetic ceramide agents can effectively compensate for diminished ceramide levels associated with various skin conditions.

Dr. Baumann is in private practice in Miami Beach. She did not disclose any conflicts of interest. To respond to this column, or to suggest topics for future columns, write to her at sknews@elsevier.com.

Structured in lamellar sheets, the primary lipids of the epidermis – ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids – play a crucial role in the barrier function of the skin. Ceramides have come to be known as a complex family of lipids (sphingolipids – a sphingoid base and a fatty acid) involved in cell signaling in addition to their role in barrier homeostasis and water retention. In fact, ceramides are known to play a critical role in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;47:681-6). Significantly, they cannot be replenished or obtained through natural sources, but synthetic ceramides, studied since the 1950s, are increasingly sophisticated and useful.

This column will review some key aspects of natural human ceramides as well as topically applied synthetic versions (also known as pseudoceramides), which are thought to ameliorate the structure and function of ceramide-depleted skin.

Ceramide structure and function

Lipids in the stratum corneum (SC) play an important role in the barrier function of the skin. The intercellular lipids of the SC are thought to be composed of approximately equal proportions of ceramides (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1987;88:2s-6s), cholesterol, and fatty acids (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2003;4:107-29). Ceramides are not found in significant supply in lower levels of the epidermis, such as the stratum granulosum or basal layer. This implies that terminal differentiation is an important component of the natural production of ceramides, of which there are at least nine classes in the SC. Ceramide 1 was first identified in 1982. In addition to ceramides 1 to 9, there are two protein-bound ceramides classified as ceramides A and B, which are covalently bound to cornified envelope proteins, such as involucrin (Bouwstra JA, Pilgrim K, Ponec M. Structure of the skin barrier, in "Skin Barrier," Elias PM, Feingold KR, Eds. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2006, p. 65) .

Ceramides are named based on the polarity and composition of the molecule. As suggested above, the foundational ceramide structure is a fatty acid covalently bound to a sphingoid base. The various classes of ceramides are grouped according to the arrangements of sphingosine (S), phytosphingosine (P), or 6-hydroxysphingosine (H) bases, to which an alpha-hydroxy (A) or nonhydroxy (N) fatty acid is attached, in addition to the presence or absence of a discrete omega-esterified linoleic acid residue (J. Lipid. Res. 2004;45:923-32).

Ceramide 1 is unique in that it is nonpolar, and it contains linoleic acid. The special function of ceramide 1 in the SC is typically ascribed to its unique structure, which is thought to allow it to act as a molecular rivet, binding the multiple bilayers of the SC (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1987;88:2s-6s). This would explain the stacking of lipid bilayers in lamellar sheets observed in the barrier. Ceramides 1, 4, and 7 exhibit critical functions in terms of epidermal integrity by serving as the primary storage areas for linoleic acid, an essential fatty acid with significant roles in the epidermal lipid barrier (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1980;74:230-3). Although all epidermal ceramides are produced from a lamellar body–derived glucosylceramide precursor, sphingomyelin-derived ceramides (ceramides 2 and 5) are essential for maintaining the integrity of the SC (J. Lipid. Res. 2000;41:2071-82). It is worth noting that because an alkaline pH suppresses beta-glucocerebrosidase and acid sphingomyelinase activity (J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005;125:510-20), alkaline soaps can exacerbate poor barrier formation.

Exposure to UVB radiation and cytokines has been associated with an increase in the regulatory enzyme for ceramide synthesis, serine palmitoyltransferase, and it has been determined that in response to UVB exposure, the epidermis upregulates sphingolipid synthesis at the mRNA and protein levels (J. Lipid. Res. 1998;39:2031-8).

Synthetic ceramides

Skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and some genetic disorders have been associated with depleted ceramide levels (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2005;6:215-23), but these diseases can be ameliorated through the use of exogenous ceramides or their analogues (topical ceramide replacement therapy) (Curr. Med. Chem. 2010;17:2301-24; J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008;51:37-43; Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2005;6:215-23). Notably, the activities of enzymes in the SC, particularly ceramidase, sphingomyelin deacylase, and glucosylceramide deacylase, have been shown to be elevated in epidermal AD (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2005;6:215-23).

Synthetic ceramides, or pseudoceramides, contain hydroxyl groups, two alkyl groups, and an amide bond – the same key structural components as natural ceramides. Consequently, various synthetic ceramides have been reported to form the multilamellar structure observed in the intercellular spaces of the SC (J. Lipid. Res. 1996;37:361-7).

Coderch et al., in a review of ceramides and skin function, endorsed the potential of topical therapy for several skin conditions using complete lipid mixtures and some ceramide supplementation, as well as the topical delivery of lipid precursors (Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2003;4:107-29). And, in fact, the topical application of synthetic ceramides has been shown to speed up the repair of impaired SC (J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94:89-96; Dermatology 2005;211:128-34). Recent reports by Tokudome et al. also indicate that the application of sphingomyelin-based liposomes effectively augments the levels of various ceramides in cultured human skin models (Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2011;24:218-23; J. Liposome Res. 2010;20:49-54).

In 2005, de Jager et al. used small-angle and wide-angle x-ray diffraction to show that lipid mixtures prepared with well-defined synthetic ceramides exhibit organization and lipid-phase behavior that are very similar to those of lamellar and lateral SC lipids, and can be used to further elucidate the molecular structure and roles of individual ceramides (J. Lipid. Res. 2005;46:2649-56).

In light of the uncertainty regarding the metabolic impact of pseudoceramides, in 2008, Uchida et al. compared the effects of two chemically unrelated, commercially available products to exogenous cell-permeant or natural ceramide on cell growth and apoptosis thresholds. Using cultured human keratinocytes, the investigators found that the commercial ceramides did not suppress keratinocyte growth or increase cell toxicity, as did the cell-permeant. The investigators suggested that these findings buttress the preclinical studies indicating that these pseudoceramides are safe for topical application (J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008;51:37-43).

Kang et al. recently conducted studies of synthetic ceramide derivatives of PC-9S (N-ethanol-2-mirystyl-3-oxostearamide), which, itself, has been shown to be effective in atopic and psoriatic patients. Both studies, conducted in NC/Nga mice, demonstrated that the topical application of the derivative K6PC-9 or the derivative K6PC-9p reduced skin inflammation and AD symptoms. According to the authors, K6PC-9 warrants consideration as a topical agent for AD, and K6PC-9p warrants consideration as a treatment for inflammatory skin diseases in general (Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:1589-97; Exp. Dermatol. 2008;17:958-64).

Subsequently, Kang et al. studied the effects of another ceramide derivative of PC-9S, K112PC-5 (2-acetyl-N-(1,3-dihydroxyisopropyl)tetradecanamide), on macrophage and T-lymphocyte function in primary macrophages and splenocytes, respectively. The researchers also studied the impact of topically applied K112PC-5 on skin inflammation and AD in NC/Nga mice. Among several findings, the investigators noted that K112PC-5 suppressed AD induced by extracts of dust mites, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae, with the pseudoceramide exhibiting in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity. They concluded that K112PC-5 is another synthetic ceramide derivative with potential as a topical agent for the treatment of AD (Arch. Pharm. Res. 2008;31:1004-9).

In 2009, Morita et al. studied the potential adverse effects of the synthetic pseudoceramide SLE66, which has demonstrated the capacity to improve xerosis, pruritus, and scaling of human skin. They found that the tested product failed to provoke cutaneous irritation or sensitization in animal and human studies. In addition, they did not observe any phototoxicity or photosensitization, and they established 1,000 mg/kg/day (the highest level tested) as the no-observed-adverse-effect (NOAEL) for systemic toxicity after oral administration or topical application (Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;47:669-73).

Conclusion

Ceramides are among the primary lipid constituents, along with cholesterol and fatty acids, of the lamellar sheets found in the intercellular spaces of the SC. Together, these lipids maintain the water permeability barrier role of the skin. Ceramides also play an important role in cell signaling. Research over the last several decades, particularly the last 20 years, indicates that topically applied synthetic ceramide agents can effectively compensate for diminished ceramide levels associated with various skin conditions.

Dr. Baumann is in private practice in Miami Beach. She did not disclose any conflicts of interest. To respond to this column, or to suggest topics for future columns, write to her at sknews@elsevier.com.

Skin laser surgery lawsuits increasing

Patients and their families sued dermatologists in 21% of 174 lawsuits filed for injuries caused by cutaneous laser surgery from 1985 through 2011. Only plastic surgeons were more likely to be defendants, accounting for 26% of cases.

The incidence of lawsuits for cutaneous laser surgery injury generally is on the upswing, increasing from five or fewer cases per year in 1985-1999 to a peak of 22 cases in 2010, Dr. H. Ray Jalian and his associates reported.

The majority of the cases involved laser hair removal (36%) and rejuvenation procedures (25%). The rejuvenation procedures included conventional ablative resurfacing, nonablative resurfacing, intense pulsed light, and the use of both ablative and nonablative fractional lasers. Plaintiffs won an average of $380,700 each in 51% of the 120 cases that reached a decision or settlement. That’s more than the average $275,000 indemnity payment across all medical specialties in a 2011 report, but the two studies used different methodologies. Dr. Jalian and his associates analyzed cutaneous laser surgery cases in the national Westlaw Next database of public records that included some form of legal pleading (JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:188-93). The previous data included all resolved claims (not only those with legal pleadings) in all specialties (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:629-36).

The physicians being sued included at least 12 other kinds of specialists, suggesting that a significant number of physicians offer or supervise laser skin treatments outside the scope of their specialty, wrote Dr. Jalian, a clinical fellow at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

General surgeons, family physicians, ob.gyns., and otolaryngologists each accounted for 5% of cases. Others included ophthalmologists (3%), orthopedic surgeons (2%), and specialists in radiology, anesthesia, physical medicine and rehabilitation, preventative medicine, and vascular surgery (1% each). Physician extenders (including physician assistants, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, aestheticians, and technicians) were laser operators or supervisors in 20% of cases.

Notably, physicians were sued even when they weren’t operating the laser, but were responsible for supervising the operator. Nonphysician operators (including physician extenders, chiropractors, podiatrists, and others) comprised 38% of operators and 26% of defendants. Physicians comprised 58% of operators and 74% of defendants. The training status of 5% of operators was unknown. (Percentages were rounded.)

After hair removal and skin rejuvenation, the most often litigated cases involved treatment of vascular lesions and telangiectasia (8% of cases) or treatment of leg veins (another 8%). Seven percent of cases involved tattoo removal, 4% involved neoplasms, 3% stemmed from treatment of scars, 2% involved laser treatment of pigmentary disorders, 1% were the use of a laser to treat pigmented lesions, and 6% were other procedures.

The most common injuries were burns (47%), scars (39%), and hypo- or hyperpigmentation (24%). Two percent of cases involved eye injuries, and at least two patients died due to complications of anesthesia.

The researchers offered several tips for physicians to reduce the risk of a lawsuit from skin laser surgery, including ensuring proper staff training and supervising delegated tasks. Be careful to evaluate skin type and select the correct laser parameters, they said. For some patients, it may be wise to do a test spot before starting laser treatment, even though solid data are lacking to support this. Follow guidelines from professional medical associations, such as the guidelines from the American Society for Laser Medicine, on delegating laser-related tasks to nonphysicians, the researchers added.

In general, federal regulations do not specify who can operate a laser, which procedures must be supervised by physicians, or where to perform procedures. Several states, including New York and Texas, do not require a license to perform laser hair removal, the most common type of laser skin surgery, the investigators noted. The lawsuits were filed in 30 states, the District of Columbia, and federal court, with the most cases in California (27), New York (23) and Texas (23).

Dr. Jalian reported having no financial disclosures. One of his coinvestigators has been a consultant and advisor for Zeltiq Aesthetics and a consultant for Unilever.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Patients and their families sued dermatologists in 21% of 174 lawsuits filed for injuries caused by cutaneous laser surgery from 1985 through 2011. Only plastic surgeons were more likely to be defendants, accounting for 26% of cases.

The incidence of lawsuits for cutaneous laser surgery injury generally is on the upswing, increasing from five or fewer cases per year in 1985-1999 to a peak of 22 cases in 2010, Dr. H. Ray Jalian and his associates reported.

The majority of the cases involved laser hair removal (36%) and rejuvenation procedures (25%). The rejuvenation procedures included conventional ablative resurfacing, nonablative resurfacing, intense pulsed light, and the use of both ablative and nonablative fractional lasers. Plaintiffs won an average of $380,700 each in 51% of the 120 cases that reached a decision or settlement. That’s more than the average $275,000 indemnity payment across all medical specialties in a 2011 report, but the two studies used different methodologies. Dr. Jalian and his associates analyzed cutaneous laser surgery cases in the national Westlaw Next database of public records that included some form of legal pleading (JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:188-93). The previous data included all resolved claims (not only those with legal pleadings) in all specialties (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:629-36).

The physicians being sued included at least 12 other kinds of specialists, suggesting that a significant number of physicians offer or supervise laser skin treatments outside the scope of their specialty, wrote Dr. Jalian, a clinical fellow at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

General surgeons, family physicians, ob.gyns., and otolaryngologists each accounted for 5% of cases. Others included ophthalmologists (3%), orthopedic surgeons (2%), and specialists in radiology, anesthesia, physical medicine and rehabilitation, preventative medicine, and vascular surgery (1% each). Physician extenders (including physician assistants, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, aestheticians, and technicians) were laser operators or supervisors in 20% of cases.

Notably, physicians were sued even when they weren’t operating the laser, but were responsible for supervising the operator. Nonphysician operators (including physician extenders, chiropractors, podiatrists, and others) comprised 38% of operators and 26% of defendants. Physicians comprised 58% of operators and 74% of defendants. The training status of 5% of operators was unknown. (Percentages were rounded.)

After hair removal and skin rejuvenation, the most often litigated cases involved treatment of vascular lesions and telangiectasia (8% of cases) or treatment of leg veins (another 8%). Seven percent of cases involved tattoo removal, 4% involved neoplasms, 3% stemmed from treatment of scars, 2% involved laser treatment of pigmentary disorders, 1% were the use of a laser to treat pigmented lesions, and 6% were other procedures.

The most common injuries were burns (47%), scars (39%), and hypo- or hyperpigmentation (24%). Two percent of cases involved eye injuries, and at least two patients died due to complications of anesthesia.

The researchers offered several tips for physicians to reduce the risk of a lawsuit from skin laser surgery, including ensuring proper staff training and supervising delegated tasks. Be careful to evaluate skin type and select the correct laser parameters, they said. For some patients, it may be wise to do a test spot before starting laser treatment, even though solid data are lacking to support this. Follow guidelines from professional medical associations, such as the guidelines from the American Society for Laser Medicine, on delegating laser-related tasks to nonphysicians, the researchers added.

In general, federal regulations do not specify who can operate a laser, which procedures must be supervised by physicians, or where to perform procedures. Several states, including New York and Texas, do not require a license to perform laser hair removal, the most common type of laser skin surgery, the investigators noted. The lawsuits were filed in 30 states, the District of Columbia, and federal court, with the most cases in California (27), New York (23) and Texas (23).

Dr. Jalian reported having no financial disclosures. One of his coinvestigators has been a consultant and advisor for Zeltiq Aesthetics and a consultant for Unilever.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Patients and their families sued dermatologists in 21% of 174 lawsuits filed for injuries caused by cutaneous laser surgery from 1985 through 2011. Only plastic surgeons were more likely to be defendants, accounting for 26% of cases.

The incidence of lawsuits for cutaneous laser surgery injury generally is on the upswing, increasing from five or fewer cases per year in 1985-1999 to a peak of 22 cases in 2010, Dr. H. Ray Jalian and his associates reported.

The majority of the cases involved laser hair removal (36%) and rejuvenation procedures (25%). The rejuvenation procedures included conventional ablative resurfacing, nonablative resurfacing, intense pulsed light, and the use of both ablative and nonablative fractional lasers. Plaintiffs won an average of $380,700 each in 51% of the 120 cases that reached a decision or settlement. That’s more than the average $275,000 indemnity payment across all medical specialties in a 2011 report, but the two studies used different methodologies. Dr. Jalian and his associates analyzed cutaneous laser surgery cases in the national Westlaw Next database of public records that included some form of legal pleading (JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:188-93). The previous data included all resolved claims (not only those with legal pleadings) in all specialties (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:629-36).

The physicians being sued included at least 12 other kinds of specialists, suggesting that a significant number of physicians offer or supervise laser skin treatments outside the scope of their specialty, wrote Dr. Jalian, a clinical fellow at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

General surgeons, family physicians, ob.gyns., and otolaryngologists each accounted for 5% of cases. Others included ophthalmologists (3%), orthopedic surgeons (2%), and specialists in radiology, anesthesia, physical medicine and rehabilitation, preventative medicine, and vascular surgery (1% each). Physician extenders (including physician assistants, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, aestheticians, and technicians) were laser operators or supervisors in 20% of cases.

Notably, physicians were sued even when they weren’t operating the laser, but were responsible for supervising the operator. Nonphysician operators (including physician extenders, chiropractors, podiatrists, and others) comprised 38% of operators and 26% of defendants. Physicians comprised 58% of operators and 74% of defendants. The training status of 5% of operators was unknown. (Percentages were rounded.)

After hair removal and skin rejuvenation, the most often litigated cases involved treatment of vascular lesions and telangiectasia (8% of cases) or treatment of leg veins (another 8%). Seven percent of cases involved tattoo removal, 4% involved neoplasms, 3% stemmed from treatment of scars, 2% involved laser treatment of pigmentary disorders, 1% were the use of a laser to treat pigmented lesions, and 6% were other procedures.

The most common injuries were burns (47%), scars (39%), and hypo- or hyperpigmentation (24%). Two percent of cases involved eye injuries, and at least two patients died due to complications of anesthesia.

The researchers offered several tips for physicians to reduce the risk of a lawsuit from skin laser surgery, including ensuring proper staff training and supervising delegated tasks. Be careful to evaluate skin type and select the correct laser parameters, they said. For some patients, it may be wise to do a test spot before starting laser treatment, even though solid data are lacking to support this. Follow guidelines from professional medical associations, such as the guidelines from the American Society for Laser Medicine, on delegating laser-related tasks to nonphysicians, the researchers added.

In general, federal regulations do not specify who can operate a laser, which procedures must be supervised by physicians, or where to perform procedures. Several states, including New York and Texas, do not require a license to perform laser hair removal, the most common type of laser skin surgery, the investigators noted. The lawsuits were filed in 30 states, the District of Columbia, and federal court, with the most cases in California (27), New York (23) and Texas (23).

Dr. Jalian reported having no financial disclosures. One of his coinvestigators has been a consultant and advisor for Zeltiq Aesthetics and a consultant for Unilever.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

FROM THE JOURNAL JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Major Finding: Plaintiffs and their families sued dermatologists in 21% of 174 lawsuits filed from 1985 through 2011 for injuries caused by cutaneous laser surgery.

Data Source: Retrospective review of records on 174 cases with legal pleadings in a national database.

Disclosures: Dr. Jalian reported having no financial disclosures. One of his coinvestigators has been a consultant and adviser for Zeltiq Aesthetics and a consultant for Unilever.

Photoprotection for Preventing Skin Cancer and Premature Skin Aging

VIDEO: What's new in hyperhidrosis therapy?

At the SDEF Hawaii Dermatology Seminar, Dr. Nazanin Saedi of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia discusses the latest treatments for hyperhidrosis.

At the SDEF Hawaii Dermatology Seminar, Dr. Nazanin Saedi of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia discusses the latest treatments for hyperhidrosis.

At the SDEF Hawaii Dermatology Seminar, Dr. Nazanin Saedi of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia discusses the latest treatments for hyperhidrosis.

Neurotic excoriation case treated successfully with onabotulinumtoxinA

ORLANDO – In what might be the first success of its kind, dermatologists at the University of Texas report treating a case of neurotic excoriations with onabotulinumtoxinA.

A 36-year-old man presented with multiple excoriated, crusted erosions on his face and scalp and also complained of tension headaches and an inability to relax.

In an attempt to relieve his headaches, Dr. Jennifer Gordon and her colleagues injected his glabella and forehead with 56 units of onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox and Botox Cosmetic).

To their surprise, in 3 weeks he was not only relieved of his headaches, but also of his excoriations.

The patient has been free of symptoms for the past year and receives maintenance injections every 4-6 months, said Dr. Gordon, a second-year dermatology resident at the University of Texas, Austin.

Neurotic excoriations (NE), also known as psychogenic excoriation, dermatillomania, or skin picking syndrome, are the result of compulsive skin picking and scratching. The condition occurs in the absence of a physical pathology and is usually associated with psychological and medical conditions that cause psychological distress.

Some studies suggest that roughly 2% of the patients at dermatology clinics have NE, and there’s a 9% prevalence of NE in patients with pruritus (itching). Researchers believe, however, that the incidence and prevalence of the condition are underreported.

Current treatments for NE include antidepressants and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dr. Gordon, who presented a poster at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference, reported that her patient described "hairs" coming out of his skin, and that twisting his body caused the hairs to coil and pull. As a result, he would pick at these areas on his face and scalp. He also complained of frequent tension headaches.

His lab values were within normal limits, Dr. Gordon reported. He was first treated for folliculitis and was given wound care instructions. He was later started on citalopram, which eliminated complaints about the hairs, but the excoriations persisted. The patient already had been treated for delusions, "and we don’t hesitate to send [the patients] for psych treatment if they need it," said Dr. Gordon, who published the poster with Dr. Jason S. Reichenberg, a faculty member at the university.

The investigators said that they believed the onabotulinumtoxinA might have induced remission in the patient by eliminating tension headaches, which could have been a trigger for his picking. The treatment also might have helped his underlying depression.

Although some statistics show that as many as one-third of NE patients also have tension or migraine headaches and gynecologic symptoms related to menstruation, it is unclear whether this treatment would work on other patients with symptoms similar to this particular patient. It’s also not yet known whether the treatment would work on other sites of the body, or on patients who do not have tension headaches, Dr. Gordon said.

The key to treatment of NE, she said, "is finding the underlying trigger."

Dr. Gordon said that she had no disclosures.

On Twitter @naseemsmiller

ORLANDO – In what might be the first success of its kind, dermatologists at the University of Texas report treating a case of neurotic excoriations with onabotulinumtoxinA.

A 36-year-old man presented with multiple excoriated, crusted erosions on his face and scalp and also complained of tension headaches and an inability to relax.

In an attempt to relieve his headaches, Dr. Jennifer Gordon and her colleagues injected his glabella and forehead with 56 units of onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox and Botox Cosmetic).

To their surprise, in 3 weeks he was not only relieved of his headaches, but also of his excoriations.

The patient has been free of symptoms for the past year and receives maintenance injections every 4-6 months, said Dr. Gordon, a second-year dermatology resident at the University of Texas, Austin.

Neurotic excoriations (NE), also known as psychogenic excoriation, dermatillomania, or skin picking syndrome, are the result of compulsive skin picking and scratching. The condition occurs in the absence of a physical pathology and is usually associated with psychological and medical conditions that cause psychological distress.

Some studies suggest that roughly 2% of the patients at dermatology clinics have NE, and there’s a 9% prevalence of NE in patients with pruritus (itching). Researchers believe, however, that the incidence and prevalence of the condition are underreported.

Current treatments for NE include antidepressants and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dr. Gordon, who presented a poster at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference, reported that her patient described "hairs" coming out of his skin, and that twisting his body caused the hairs to coil and pull. As a result, he would pick at these areas on his face and scalp. He also complained of frequent tension headaches.

His lab values were within normal limits, Dr. Gordon reported. He was first treated for folliculitis and was given wound care instructions. He was later started on citalopram, which eliminated complaints about the hairs, but the excoriations persisted. The patient already had been treated for delusions, "and we don’t hesitate to send [the patients] for psych treatment if they need it," said Dr. Gordon, who published the poster with Dr. Jason S. Reichenberg, a faculty member at the university.

The investigators said that they believed the onabotulinumtoxinA might have induced remission in the patient by eliminating tension headaches, which could have been a trigger for his picking. The treatment also might have helped his underlying depression.

Although some statistics show that as many as one-third of NE patients also have tension or migraine headaches and gynecologic symptoms related to menstruation, it is unclear whether this treatment would work on other patients with symptoms similar to this particular patient. It’s also not yet known whether the treatment would work on other sites of the body, or on patients who do not have tension headaches, Dr. Gordon said.

The key to treatment of NE, she said, "is finding the underlying trigger."

Dr. Gordon said that she had no disclosures.

On Twitter @naseemsmiller

ORLANDO – In what might be the first success of its kind, dermatologists at the University of Texas report treating a case of neurotic excoriations with onabotulinumtoxinA.

A 36-year-old man presented with multiple excoriated, crusted erosions on his face and scalp and also complained of tension headaches and an inability to relax.

In an attempt to relieve his headaches, Dr. Jennifer Gordon and her colleagues injected his glabella and forehead with 56 units of onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox and Botox Cosmetic).

To their surprise, in 3 weeks he was not only relieved of his headaches, but also of his excoriations.

The patient has been free of symptoms for the past year and receives maintenance injections every 4-6 months, said Dr. Gordon, a second-year dermatology resident at the University of Texas, Austin.

Neurotic excoriations (NE), also known as psychogenic excoriation, dermatillomania, or skin picking syndrome, are the result of compulsive skin picking and scratching. The condition occurs in the absence of a physical pathology and is usually associated with psychological and medical conditions that cause psychological distress.

Some studies suggest that roughly 2% of the patients at dermatology clinics have NE, and there’s a 9% prevalence of NE in patients with pruritus (itching). Researchers believe, however, that the incidence and prevalence of the condition are underreported.

Current treatments for NE include antidepressants and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dr. Gordon, who presented a poster at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference, reported that her patient described "hairs" coming out of his skin, and that twisting his body caused the hairs to coil and pull. As a result, he would pick at these areas on his face and scalp. He also complained of frequent tension headaches.

His lab values were within normal limits, Dr. Gordon reported. He was first treated for folliculitis and was given wound care instructions. He was later started on citalopram, which eliminated complaints about the hairs, but the excoriations persisted. The patient already had been treated for delusions, "and we don’t hesitate to send [the patients] for psych treatment if they need it," said Dr. Gordon, who published the poster with Dr. Jason S. Reichenberg, a faculty member at the university.

The investigators said that they believed the onabotulinumtoxinA might have induced remission in the patient by eliminating tension headaches, which could have been a trigger for his picking. The treatment also might have helped his underlying depression.

Although some statistics show that as many as one-third of NE patients also have tension or migraine headaches and gynecologic symptoms related to menstruation, it is unclear whether this treatment would work on other patients with symptoms similar to this particular patient. It’s also not yet known whether the treatment would work on other sites of the body, or on patients who do not have tension headaches, Dr. Gordon said.

The key to treatment of NE, she said, "is finding the underlying trigger."

Dr. Gordon said that she had no disclosures.

On Twitter @naseemsmiller

AT THE ORLANDO DERMATOLOGY AESTHETIC AND CLINICAL CONFERENCE

The puzzling relationship between diet and acne

The relationship between acne and diet has been an ongoing debate. There are no meta-analyses, randomized controlled clinical studies, or well-designed scientific trials that follow evidence-based guidelines to elucidate a cause-effect relationship. However, for decades anecdotal evidence has shown that acne and insulin resistance, such as that seen in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), are highly linked. Now the literature points to the growing relationship between nutrition and the prevalence of acne, especially to glycemic index and the consumption of dairy.

Glycemic index is a ranking system based on the quality and quantity of consumed carbohydrates and its ability to raise blood sugar levels. Foods with high glycemic indices such as potatoes, bread, chips, and pasta, require more insulin to maintain blood glucose levels within the normal range. High-glycemic diets that are prevalent in the United States not only lead to insulin resistance, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease but also to acne.

Several studies have looked at the glycemic load, insulin sensitivity, and hormonal mediators correlating to acne (Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007; 86:107-15; J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008;50:41-52). Foods with a high-glycemic index may contribute to acne by elevating serum insulin concentrations (which can stimulate sebocyte proliferation and sebum production), suppress sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) concentrations, and raise androgen concentrations. On the contrary, low-glycemic-index foods increase SHBG and reduce androgen levels; this is of great importance because higher SHBG levels are associated with lower acne severity. Consumption of fat and carbohydrates increases sebum production and affects sebum composition, ultimately encouraging acne production (Br. J. Dermatol. 1967;79:119-21).

A new study by Anna Di Landro et al. published in the December 2012 found a link between acne and the consumption of milk, particularly in those drinking skim milk and more than three servings of milk per week (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012;67:1129-35).

Dr. Di Landro et al. also found that the consumption of fish had a protective effect on acne. This interesting finding points to the larger issue of acne developing in ethnic populations that immigrate to the United States. Population studies have shown that non-Western diets have a reduced incidence of acne. Western diets are deficient in long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. The ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids in our Western diet is 10:1 to 20:1, vs. 3:1 to 2:1 in a non-Western diet. Omega-6 fatty acids in increased concentrations induce proinflammatory mediators and have been associated with the development of inflammatory acne. Western diets with high consumption of seafood have high levels of omega-3 fatty acids and have shown to decrease inflammatory mediators in the skin (Arch. Dermatol. 2003;139:941-2).

In my clinic, the ethnic populations that immigrate to the United States often develop acne to a greater extent than they had in their native countries. Although factors including stress, hormonal differences in foods, and pollution can be confounding factors, we must not ignore the Western diet that these populations adapt to is higher in refined sugars and carbohydrates and lower in vegetables and lean protein. Every acne patient in my clinic is asked to complete a nutritional questionnaire discussing the intake of fast food, carbohydrates, juice, sodas, and processed sugar. We have noticed that acne improves clinically and is more responsive to traditional acne medications when patients reduce their consumption of processed sugars and dairy and increase their intake of lean protein. Similarly, our PCOS patients who are treated with medications such as metformin, which improves the body’s ability to regulate blood glucose levels, have improvements in their acne. So, is acne a marker for early insulin resistance?

The underlying etiology of acne is multifactorial, although now we can appreciate diet as one of the causative factors. Although there is no direct correlation between obesity or insulin resistance and the prevalence of acne, a low glycemic index diet in combination with topical and systemic acne medications can be a powerful method of treating acne. Nutritional counseling is an adjunct educational service we should provide to our patients in addition to skin care advice and medical treatments for acne.

No single food directly causes acne, but a balanced diet can alter its severity. Encouraging our patients to eat a variety of fruits and vegetables, lean protein, and healthy fats can prevent the inflammation seen with acne and also can protect against cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, and even obesity.

It is unfortunate that the medical education system in the United States has no formal nutrition education. Nearly every field of medicine including internal medicine, cardiology, endocrinology, allergy, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, surgery, and not the least, dermatology, is influenced in some realm by nutrition. As the population diversifies, so will the importance of dietary guidance. We need to educate ourselves and our residents-in-training to better appreciate the symbiotic relationship between diet and skin health and to provide this guidance to our patients.

Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va.

Do you have questions about treating patients with dark skin? If so, send them to sknews@elsevier.com.

The relationship between acne and diet has been an ongoing debate. There are no meta-analyses, randomized controlled clinical studies, or well-designed scientific trials that follow evidence-based guidelines to elucidate a cause-effect relationship. However, for decades anecdotal evidence has shown that acne and insulin resistance, such as that seen in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), are highly linked. Now the literature points to the growing relationship between nutrition and the prevalence of acne, especially to glycemic index and the consumption of dairy.

Glycemic index is a ranking system based on the quality and quantity of consumed carbohydrates and its ability to raise blood sugar levels. Foods with high glycemic indices such as potatoes, bread, chips, and pasta, require more insulin to maintain blood glucose levels within the normal range. High-glycemic diets that are prevalent in the United States not only lead to insulin resistance, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease but also to acne.

Several studies have looked at the glycemic load, insulin sensitivity, and hormonal mediators correlating to acne (Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007; 86:107-15; J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008;50:41-52). Foods with a high-glycemic index may contribute to acne by elevating serum insulin concentrations (which can stimulate sebocyte proliferation and sebum production), suppress sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) concentrations, and raise androgen concentrations. On the contrary, low-glycemic-index foods increase SHBG and reduce androgen levels; this is of great importance because higher SHBG levels are associated with lower acne severity. Consumption of fat and carbohydrates increases sebum production and affects sebum composition, ultimately encouraging acne production (Br. J. Dermatol. 1967;79:119-21).

A new study by Anna Di Landro et al. published in the December 2012 found a link between acne and the consumption of milk, particularly in those drinking skim milk and more than three servings of milk per week (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012;67:1129-35).

Dr. Di Landro et al. also found that the consumption of fish had a protective effect on acne. This interesting finding points to the larger issue of acne developing in ethnic populations that immigrate to the United States. Population studies have shown that non-Western diets have a reduced incidence of acne. Western diets are deficient in long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. The ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids in our Western diet is 10:1 to 20:1, vs. 3:1 to 2:1 in a non-Western diet. Omega-6 fatty acids in increased concentrations induce proinflammatory mediators and have been associated with the development of inflammatory acne. Western diets with high consumption of seafood have high levels of omega-3 fatty acids and have shown to decrease inflammatory mediators in the skin (Arch. Dermatol. 2003;139:941-2).

In my clinic, the ethnic populations that immigrate to the United States often develop acne to a greater extent than they had in their native countries. Although factors including stress, hormonal differences in foods, and pollution can be confounding factors, we must not ignore the Western diet that these populations adapt to is higher in refined sugars and carbohydrates and lower in vegetables and lean protein. Every acne patient in my clinic is asked to complete a nutritional questionnaire discussing the intake of fast food, carbohydrates, juice, sodas, and processed sugar. We have noticed that acne improves clinically and is more responsive to traditional acne medications when patients reduce their consumption of processed sugars and dairy and increase their intake of lean protein. Similarly, our PCOS patients who are treated with medications such as metformin, which improves the body’s ability to regulate blood glucose levels, have improvements in their acne. So, is acne a marker for early insulin resistance?