User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Patient Navigators for Serious Illnesses Can Now Bill Under New Medicare Codes

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a move that acknowledges the gauntlet the US health system poses for people facing serious and fatal illnesses, Medicare will pay for a new class of workers to help patients manage treatments for conditions like cancer and heart failure.

The 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule includes new billing codes, including G0023, to pay for 60 minutes a month of care coordination by certified or trained auxiliary personnel working under the direction of a clinician.

A diagnosis of cancer or another serious illness takes a toll beyond the physical effects of the disease. Patients often scramble to make adjustments in family and work schedules to manage treatment, said Samyukta Mullangi, MD, MBA, medical director of oncology at Thyme Care, a Nashville, Tennessee–based firm that provides navigation and coordination services to oncology practices and insurers.

“It just really does create a bit of a pressure cooker for patients,” Dr. Mullangi told this news organization.

Medicare has for many years paid for medical professionals to help patients cope with the complexities of disease, such as chronic care management (CCM) provided by physicians, nurses, and physician assistants.

The new principal illness navigation (PIN) payments are intended to pay for work that to date typically has been done by people without medical degrees, including those involved in peer support networks and community health programs. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services(CMS) expects these navigators will undergo training and work under the supervision of clinicians.

The new navigators may coordinate care transitions between medical settings, follow up with patients after emergency department (ED) visits, or communicate with skilled nursing facilities regarding the psychosocial needs and functional deficits of a patient, among other functions.

CMS expects the new navigators may:

- Conduct assessments to understand a patient’s life story, strengths, needs, goals, preferences, and desired outcomes, including understanding cultural and linguistic factors.

- Provide support to accomplish the clinician’s treatment plan.

- Coordinate the receipt of needed services from healthcare facilities, home- and community-based service providers, and caregivers.

Peers as Navigators

The new navigators can be former patients who have undergone similar treatments for serious diseases, CMS said. This approach sets the new program apart from other care management services Medicare already covers, program officials wrote in the 2024 physician fee schedule.

“For some conditions, patients are best able to engage with the healthcare system and access care if they have assistance from a single, dedicated individual who has ‘lived experience,’ ” according to the rule.

The agency has taken a broad initial approach in defining what kinds of illnesses a patient may have to qualify for services. Patients must have a serious condition that is expected to last at least 3 months, such as cancer, heart failure, or substance use disorder.

But those without a definitive diagnosis may also qualify to receive navigator services.

In the rule, CMS cited a case in which a CT scan identified a suspicious mass in a patient’s colon. A clinician might decide this person would benefit from navigation services due to the potential risks for an undiagnosed illness.

“Regardless of the definitive diagnosis of the mass, presence of a colonic mass for that patient may be a serious high-risk condition that could, for example, cause obstruction and lead the patient to present to the emergency department, as well as be potentially indicative of an underlying life-threatening illness such as colon cancer,” CMS wrote in the rule.

Navigators often start their work when cancer patients are screened and guide them through initial diagnosis, potential surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, said Sharon Gentry, MSN, RN, a former nurse navigator who is now the editor in chief of the Journal of the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators.

The navigators are meant to be a trusted and continual presence for patients, who otherwise might be left to start anew in finding help at each phase of care.

The navigators “see the whole picture. They see the whole journey the patient takes, from pre-diagnosis all the way through diagnosis care out through survival,” Ms. Gentry said.

Gaining a special Medicare payment for these kinds of services will elevate this work, she said.

Many newer drugs can target specific mechanisms and proteins of cancer. Often, oncology treatment involves testing to find out if mutations are allowing the cancer cells to evade a patient’s immune system.

Checking these biomarkers takes time, however. Patients sometimes become frustrated because they are anxious to begin treatment. Patients may receive inaccurate information from friends or family who went through treatment previously. Navigators can provide knowledge on the current state of care for a patient’s disease, helping them better manage anxieties.

“You have to explain to them that things have changed since the guy you drink coffee with was diagnosed with cancer, and there may be a drug that could target that,” Ms. Gentry said.

Potential Challenges

Initial uptake of the new PIN codes may be slow going, however, as clinicians and health systems may already use well-established codes. These include CCM and principal care management services, which may pay higher rates, Mullangi said.

“There might be sensitivity around not wanting to cannibalize existing programs with a new program,” Dr. Mullangi said.

In addition, many patients will have a copay for the services of principal illness navigators, Dr. Mullangi said.

While many patients have additional insurance that would cover the service, not all do. People with traditional Medicare coverage can sometimes pay 20% of the cost of some medical services.

“I think that may give patients pause, particularly if they’re already feeling the financial burden of a cancer treatment journey,” Dr. Mullangi said.

Pay rates for PIN services involve calculations of regional price differences, which are posted publicly by CMS, and potential added fees for services provided by hospital-affiliated organizations.

Consider payments for code G0023, covering 60 minutes of principal navigation services provided in a single month.

A set reimbursement for patients cared for in independent medical practices exists, with variation for local costs. Medicare’s non-facility price for G0023 would be $102.41 in some parts of Silicon Valley in California, including San Jose. In Arkansas, where costs are lower, reimbursement would be $73.14 for this same service.

Patients who get services covered by code G0023 in independent medical practices would have monthly copays of about $15-$20, depending on where they live.

The tab for patients tends to be higher for these same services if delivered through a medical practice owned by a hospital, as this would trigger the addition of facility fees to the payments made to cover the services. Facility fees are difficult for the public to ascertain before getting a treatment or service.

Dr. Mullangi and Ms. Gentry reported no relevant financial disclosures outside of their employers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How to explain physician compounding to legislators

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

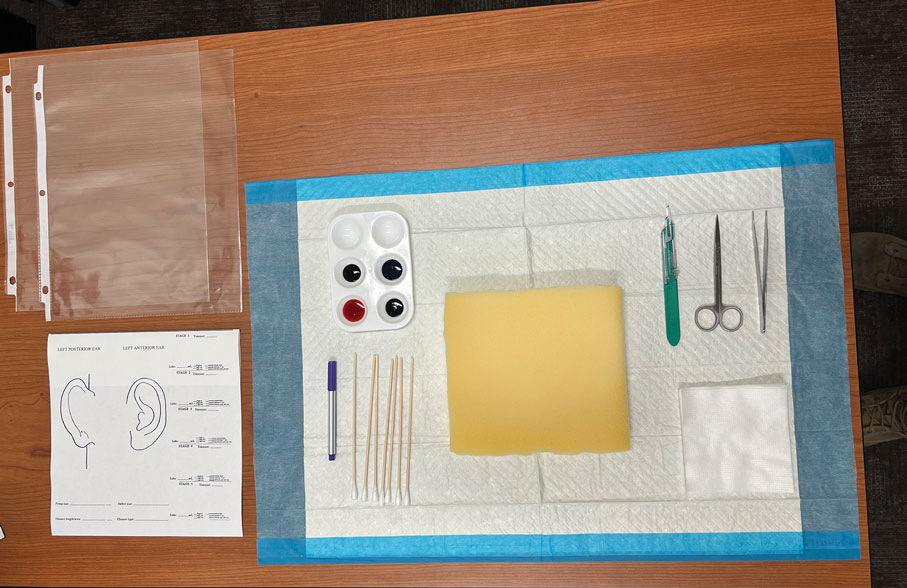

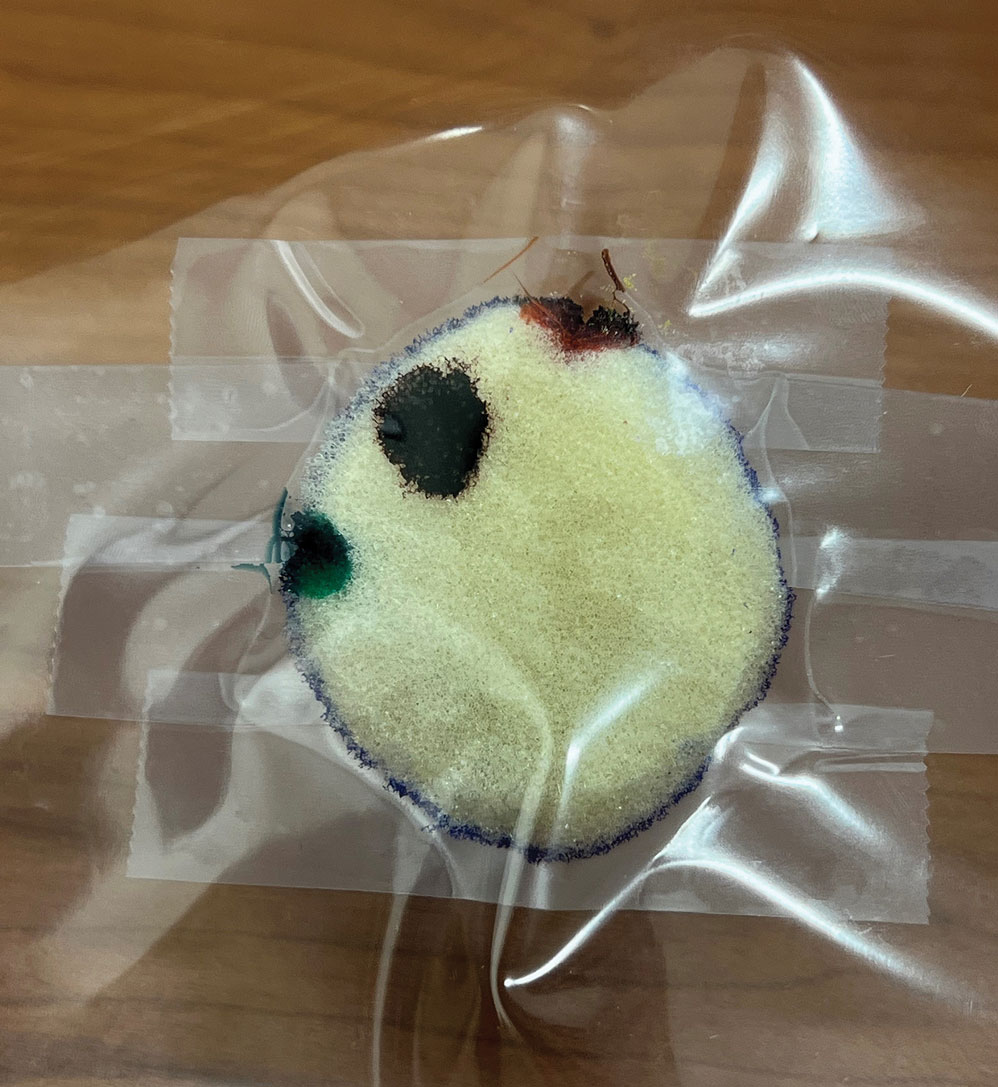

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

In Ohio, new limits on drug compounding in physicians’ offices went into effect in April and have become a real hindrance to care for dermatology patients. The State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined compounding as combining two or more prescription drugs and has required that physicians who perform this “compounding” must obtain a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license. Ohio is the “test state,” and these rules, unless vigorously opposed, will be coming to your state.

[polldaddy:9779752]

The rules state that “compounded” drugs used within 6 hours of preparation must be prepared in a designated clean medication area with proper hand hygiene and the use of powder-free gloves. “Compounded” drugs that are used more than 6 hours after preparation, require a designated clean room with access limited to authorized personnel, environmental control devices such as a laminar flow hood, and additional equipment and training of personnel to maintain an aseptic environment. A separate license is required for each office location.

The state pharmacy boards are eager to restrict physicians – as well as dentists and veterinarians – and to collect annual licensing fees. Additionally, according to an article from the Ohio State Medical Association, noncompliant physicians can be fined by the pharmacy board.

We are talking big money, power, and dreams of clinical relevancy (and billable activities) here.

What can dermatologists do to prevent this regulatory overreach? I encourage you to plan a visit to your state representative, where you can demonstrate how these restrictions affect you and your patients – an exercise that should be both fun and compelling. All you need to illustrate your case is a simple kit that includes a syringe (but no needles in the statehouse!), a bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine, a bottle of 8.4% bicarbonate, alcohol pads, and gloves.

First, explain to your audience that there is a skin cancer epidemic with more than 5.4 million new cases a year and that, over the past 20 years, the incidence of skin cancer has doubled and is projected to double again over the next 20 years. Further, explain that dermatologists treat more than 70% of these cases in the office setting, under local anesthesia, at a huge cost savings to the public and government (it costs an average of 12 times as much to remove these cancers in the outpatient department at the hospital). Remember, states foot most of the bill for Medicaid and Medicare gap indigent coverage.

Take the bottle of lidocaine with epinephrine and open the syringe pack (Staffers love this demonstration; everyone is fascinated with shots.). Put on your gloves, wipe the top of the lidocaine bottle with an alcohol swab, and explain that this medicine is the anesthetic preferred for skin cancer surgery. Explain how it not only numbs the skin, but also causes vasoconstriction, so that the cancer can be easily and safely removed in the office.

Then explain that, in order for the epinephrine to be stable, the solution has to be very acidic (a pH of 4.2, in fact). Explain that this makes it burn like hell unless you add 0.1 cc per cc of 8.4% bicarbonate, in which case the perceived pain on a 10-point scale will drop from 8 to 2. Then pick up the bottle of bicarbonate and explain that you will no longer be able to mix these two components anymore without a “Terminal Distributor of Dangerous Drugs” license because your state pharmacy board considers this compounding. Your representative is likely to give you looks of astonishment, disbelief, and then a dawning realization of the absurdity of the situation.

Follow-up questions may include “Why can’t you buy buffered lidocaine with epinephrine from the compounding pharmacy?” Easy answer: because each patient needs an individual prescription, and you may not know in advance which patient will need it, and how much the patient will need, and it becomes unstable once it has been buffered. It also will cost the patient $45 per 5-cc syringe, and it will be degraded by the time the patient returns from the compounding pharmacy. Explain further that it costs you only 84 cents to make a 5-cc syringe of buffered lidocaine; that some patients may need as many as 10 syringes; and that these costs are all included in the surgery (free!) if the physician draws it up in the office.

A simple summary is – less pain, less cost – and no history of infections or complications.

It is an eye-opener when you demonstrate how ridiculous the compounding rules being imposed are for physicians and patients. I’ve used this demonstration at the state and federal legislative level, and more recently, at the Food and Drug Administration.

If you get the chance, when a state legislator is in your office, become an advocate for your patients and fellow physicians. Make sure physician offices are excluded from these definitions of com

This column was updated June 22, 2017.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Best Practices: Protecting Dry Vulnerable Skin with CeraVe® Healing Ointment

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

A supplement to Dermatology News. This advertising supplement is sponsored by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

- Reinforcing the Skin Barrier

- NEA Seal of Acceptance

- A Preventative Approach to Dry, Cracked Skin

- CeraVe Ointment in the Clinical Setting

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure

Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Professor of Clinical Dermatology & Pediatrics

Director, Pediatric Dermatology Fellowship Training Program

University of California at San Diego School of Medicine

Rady Children’s Hospital,

San Diego, California

Dr. Friedlander was compensated for her participation in the development of this article.

CeraVe is a registered trademark of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. or its affiliates.

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

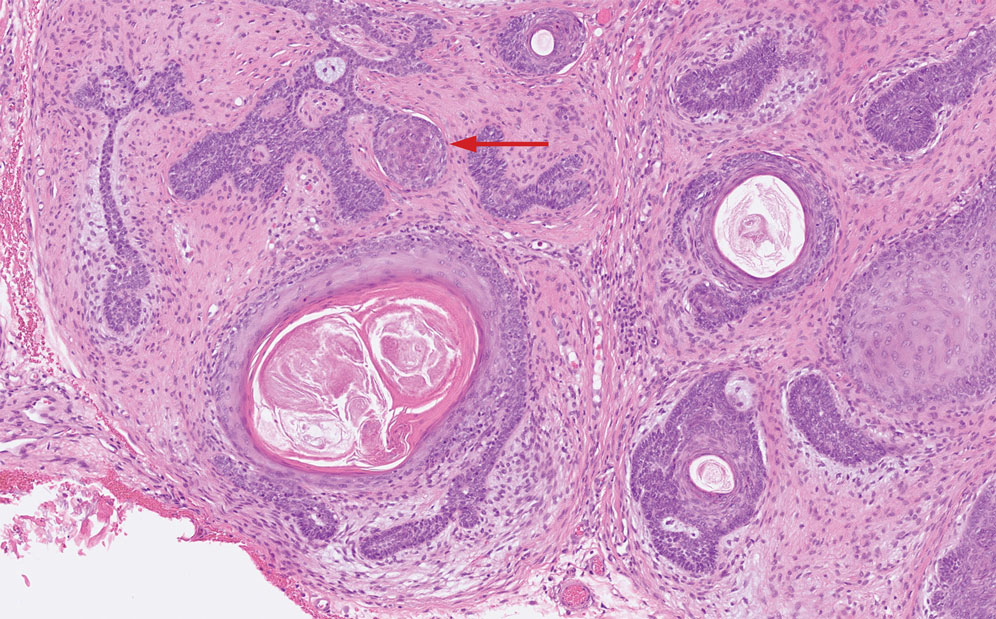

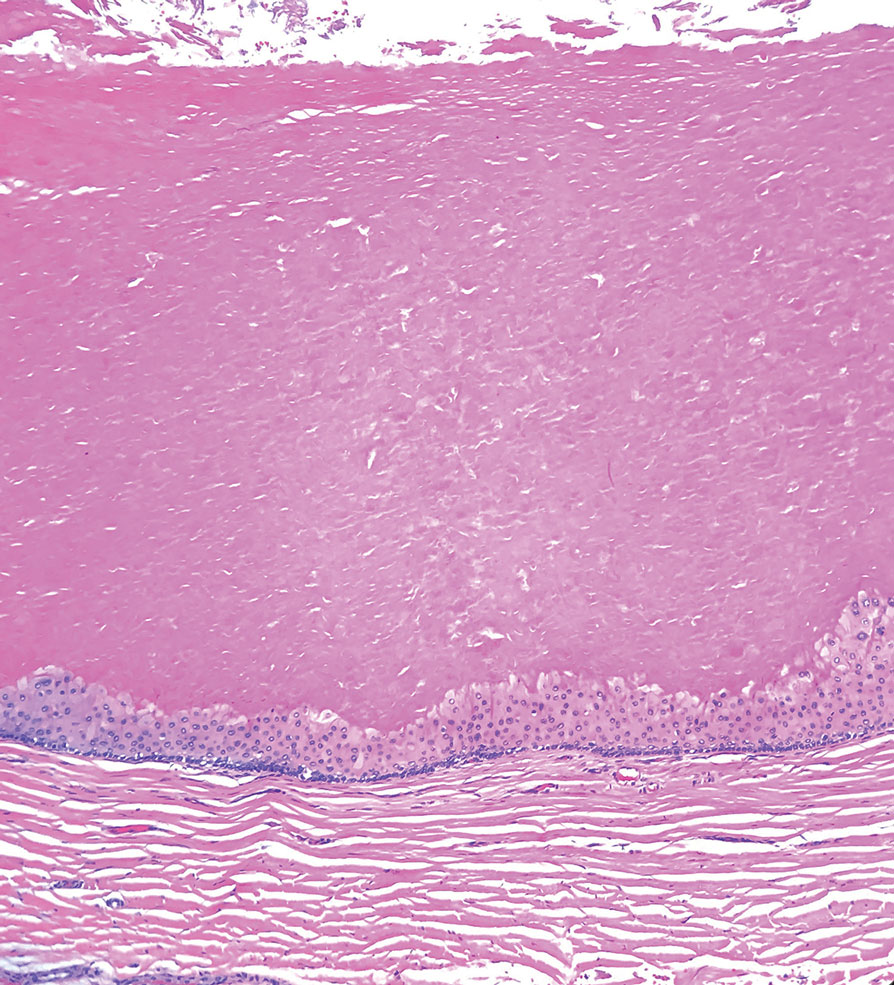

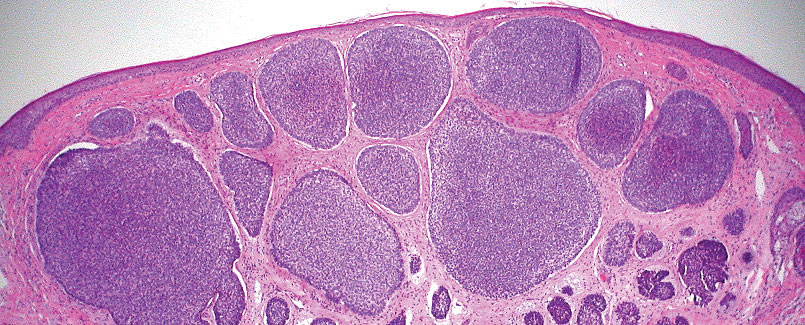

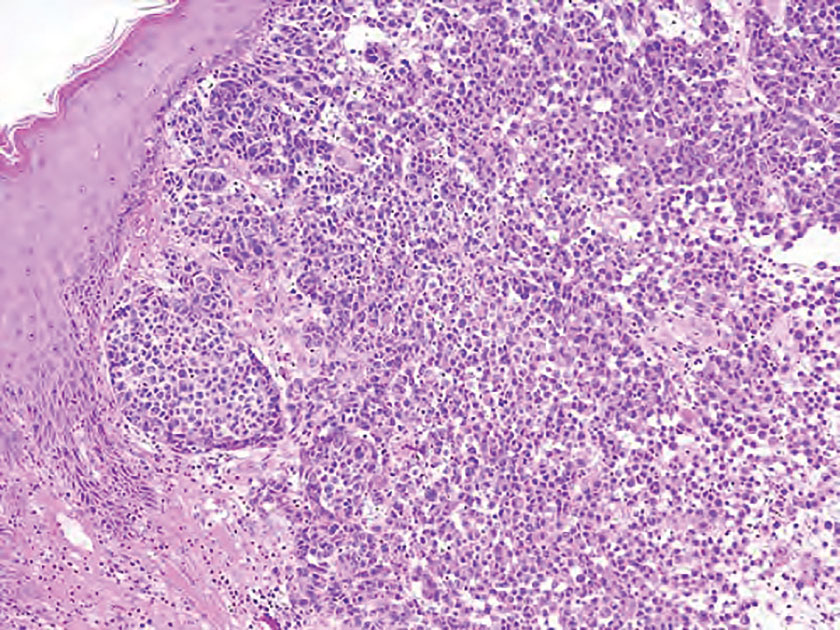

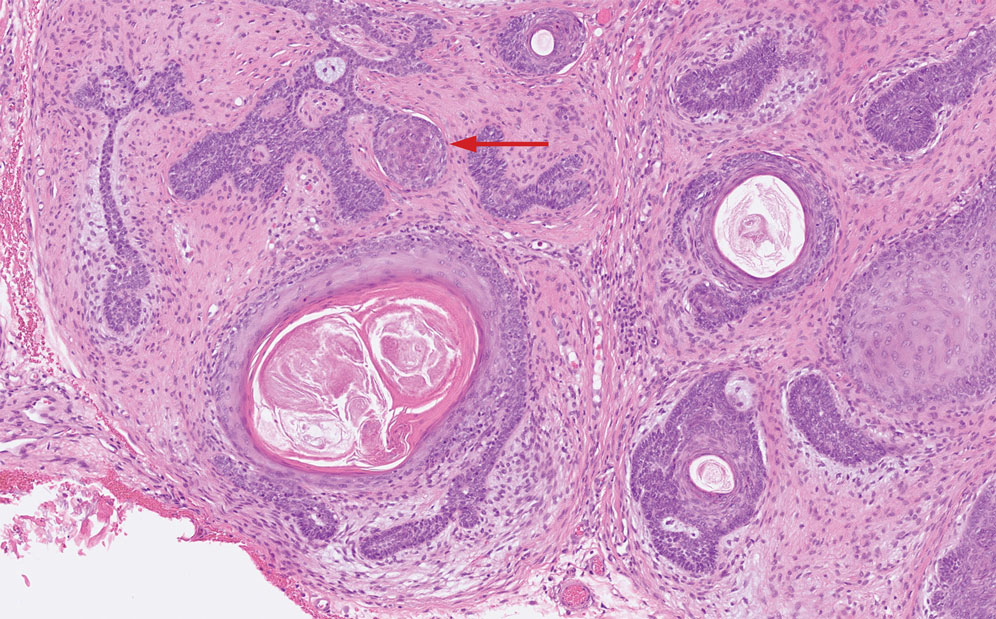

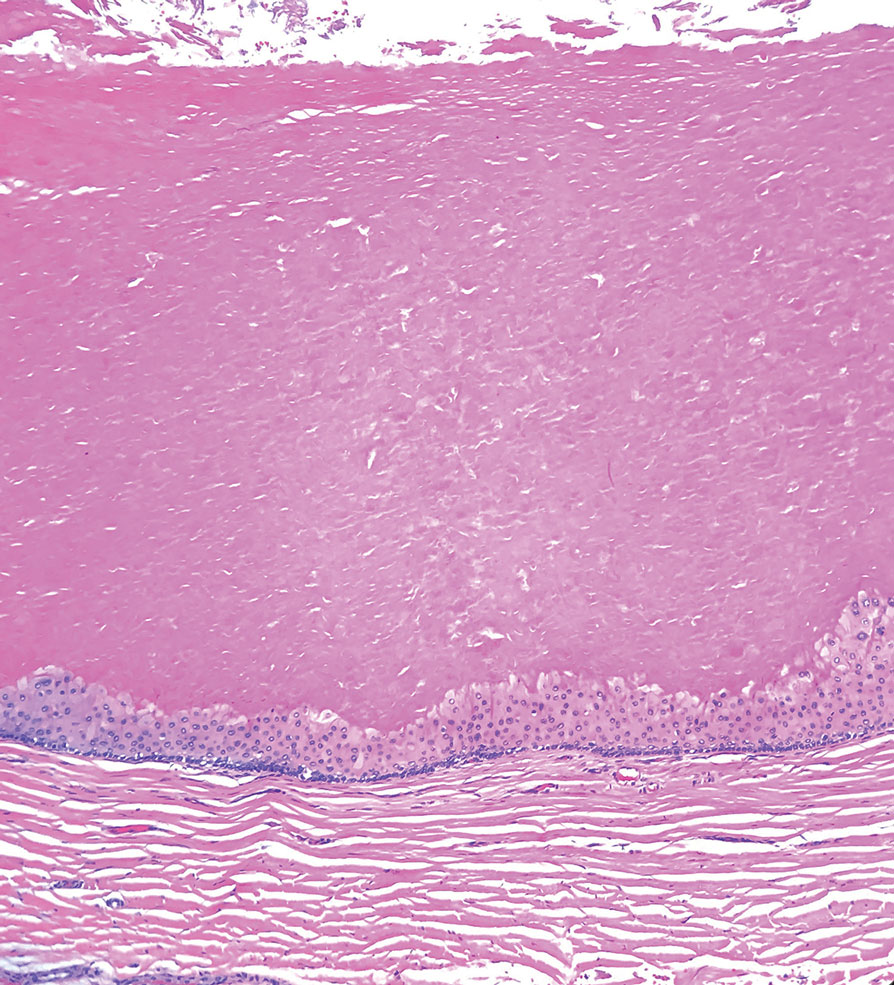

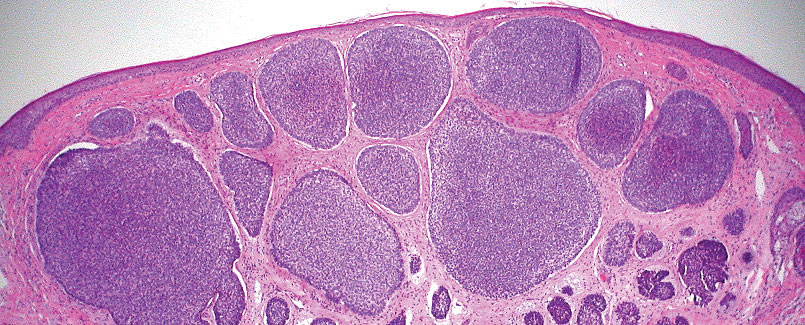

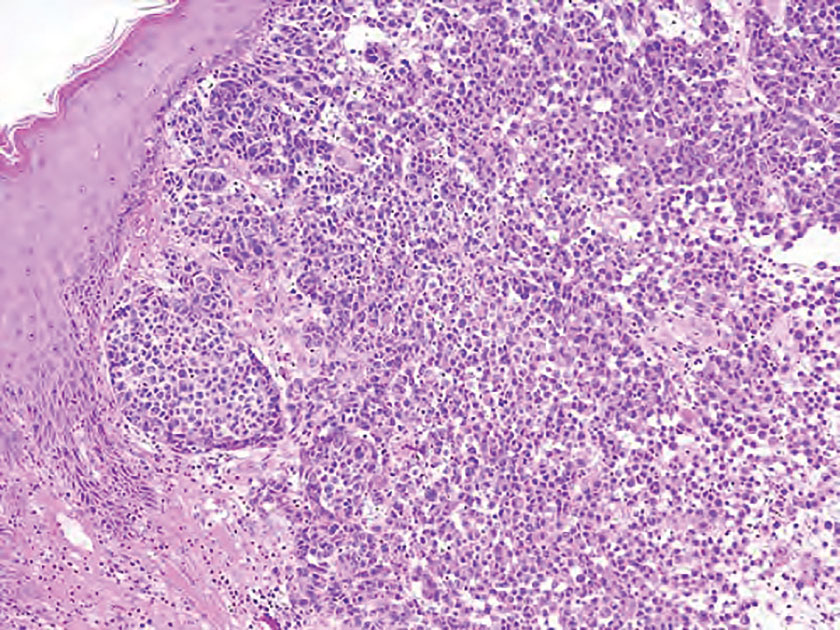

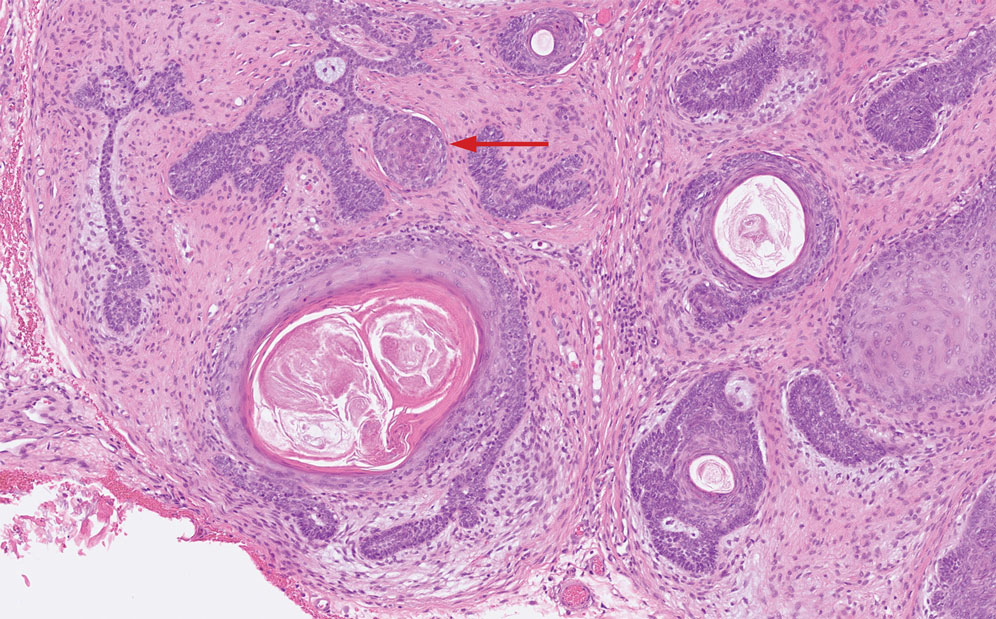

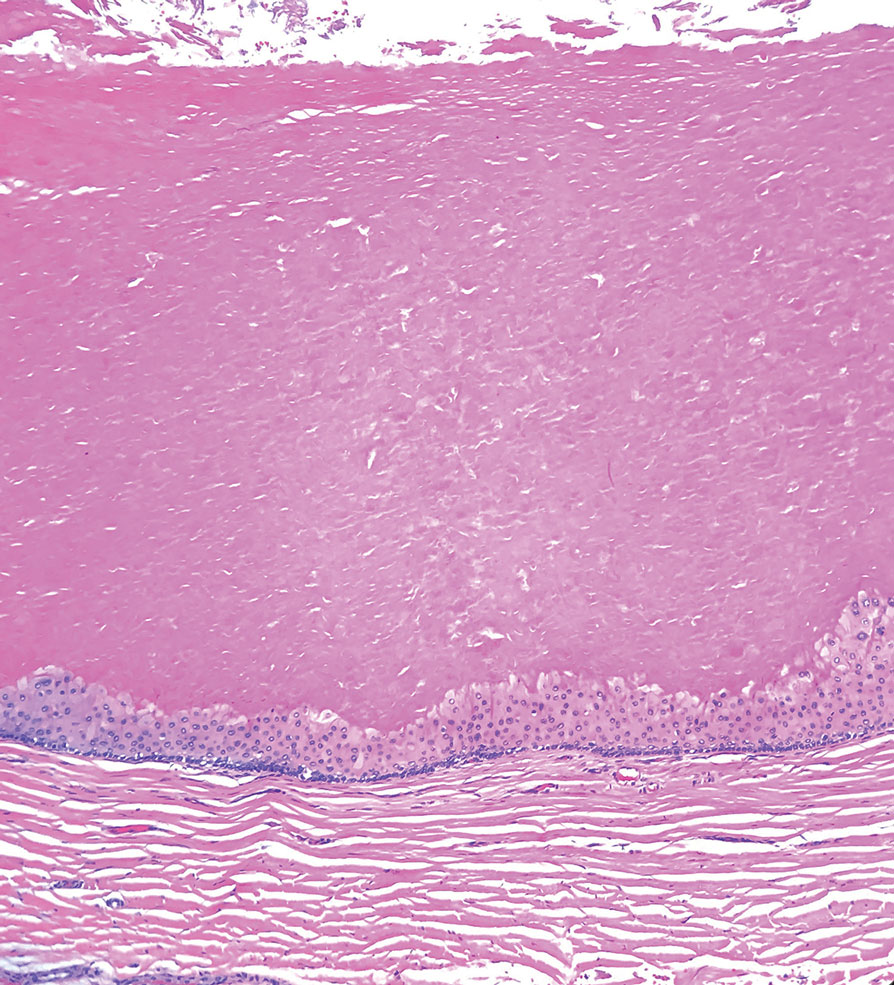

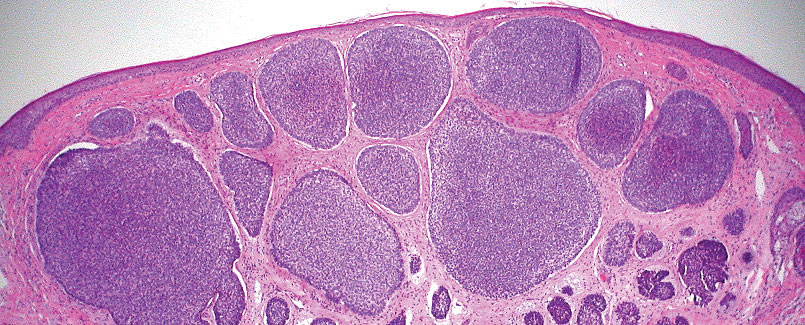

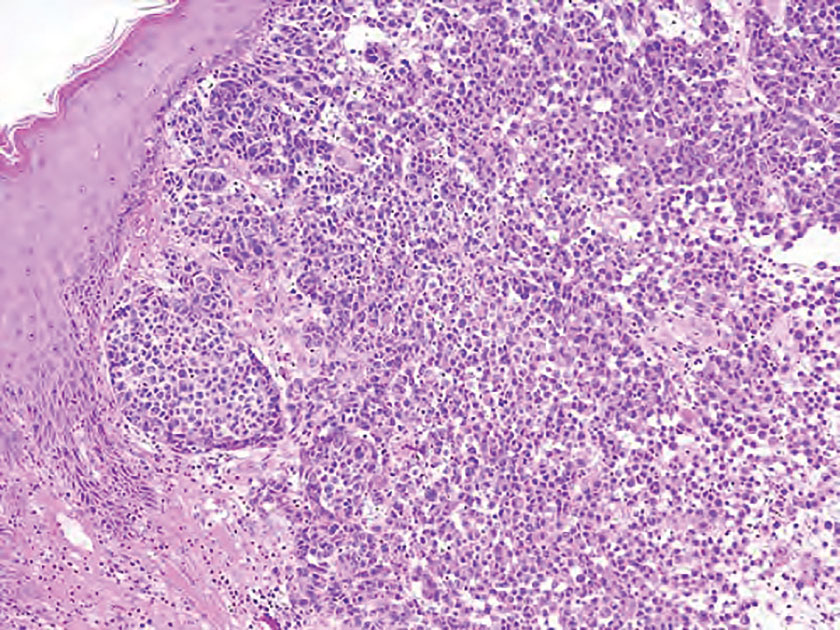

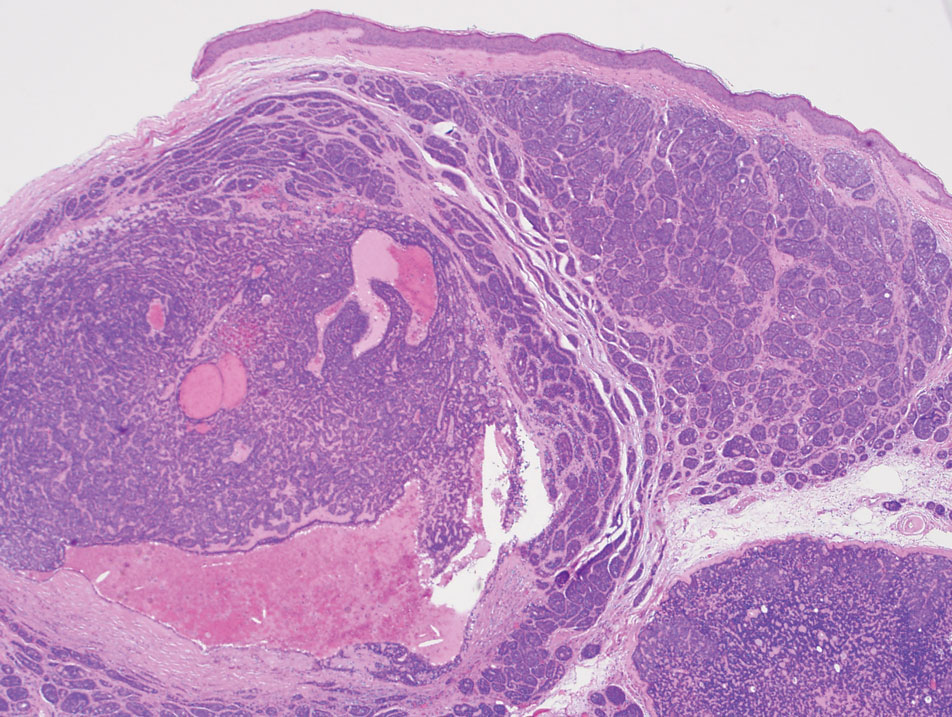

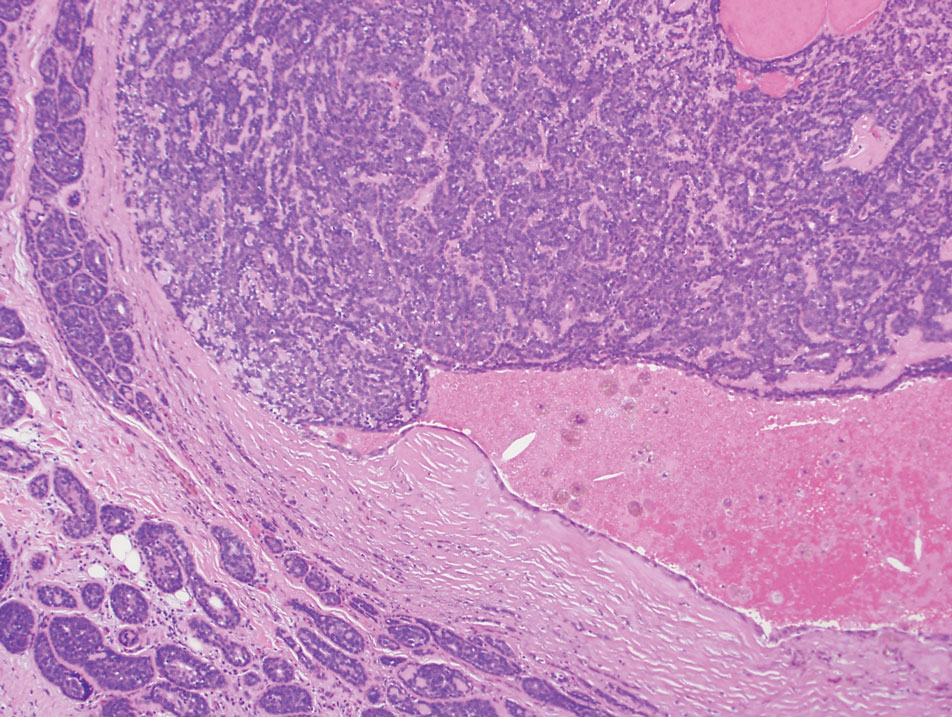

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

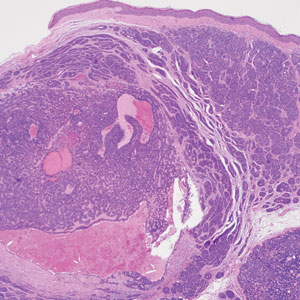

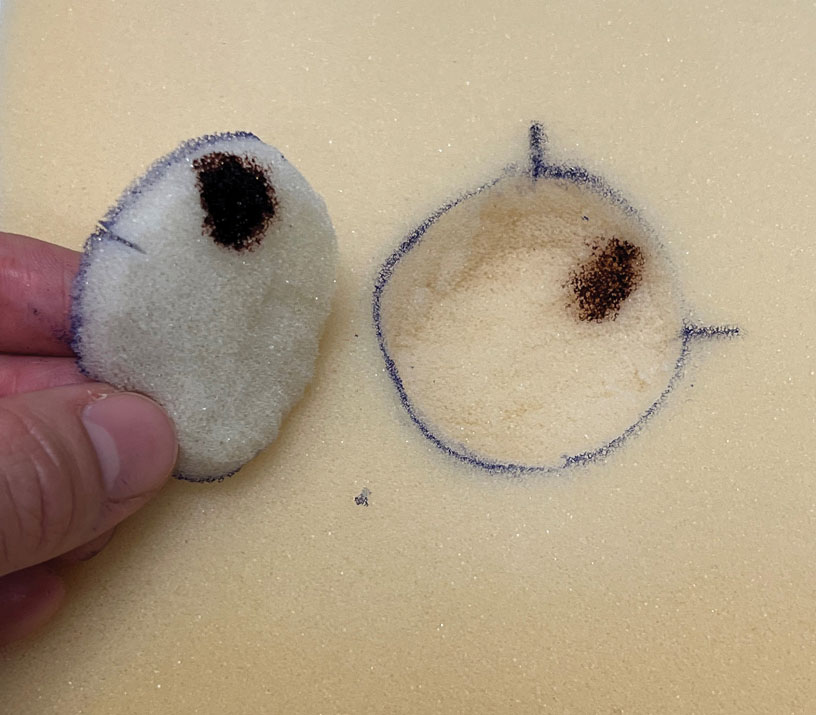

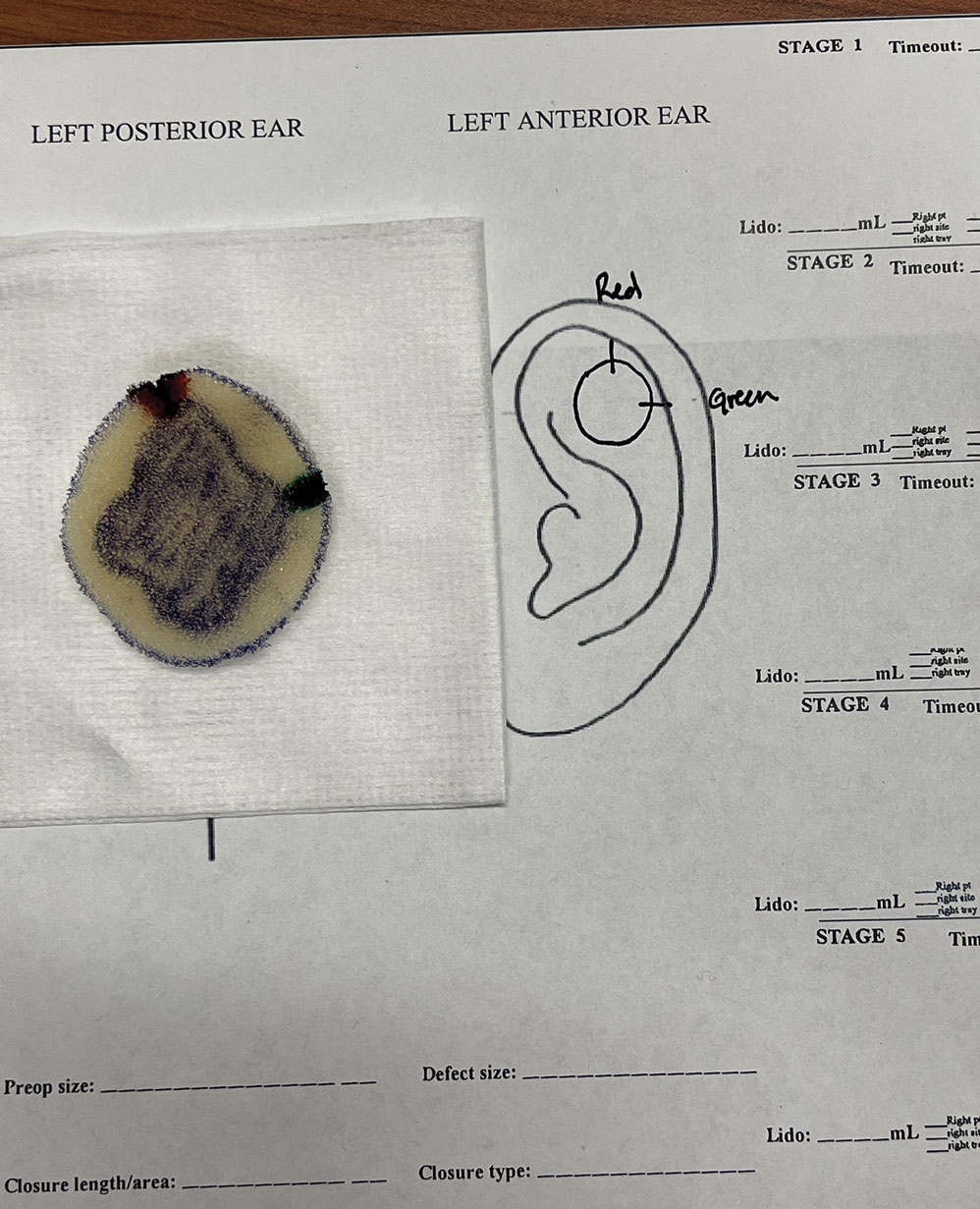

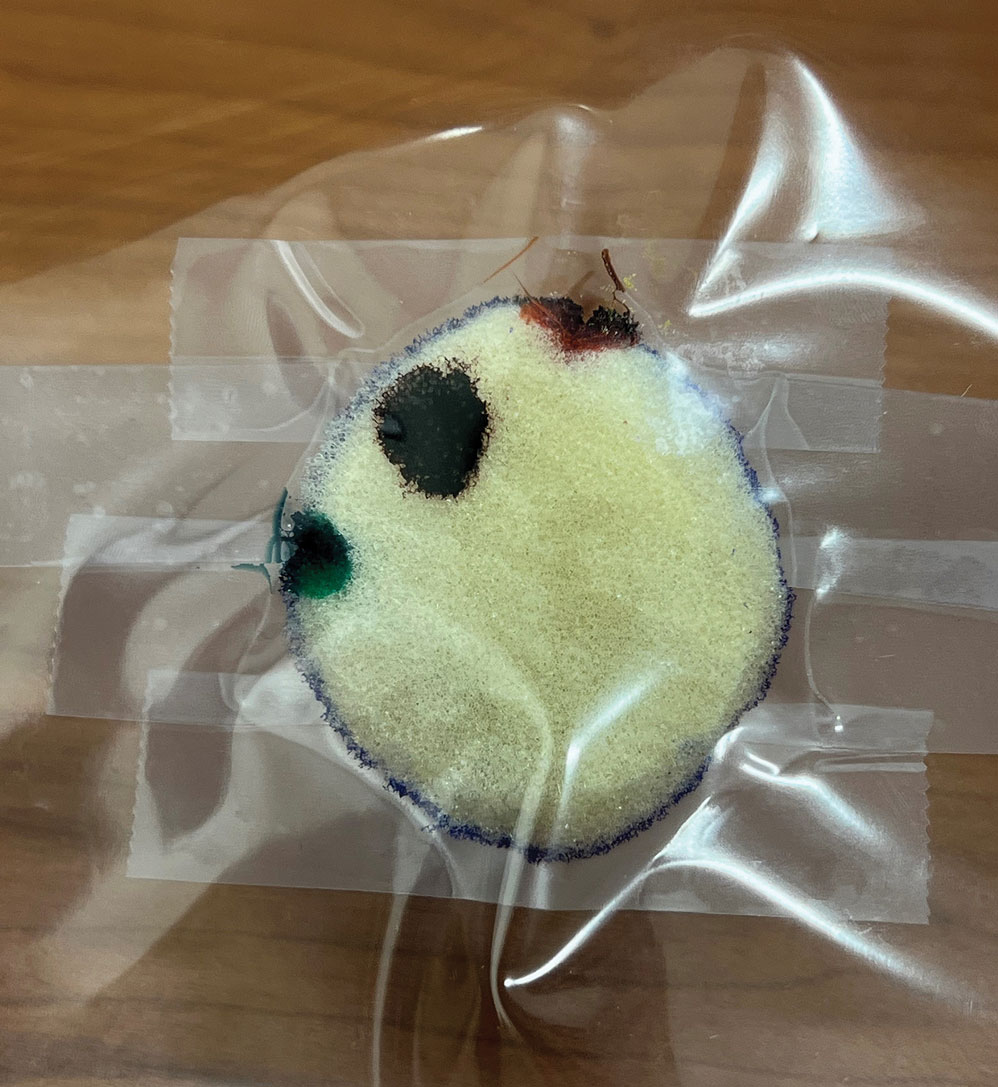

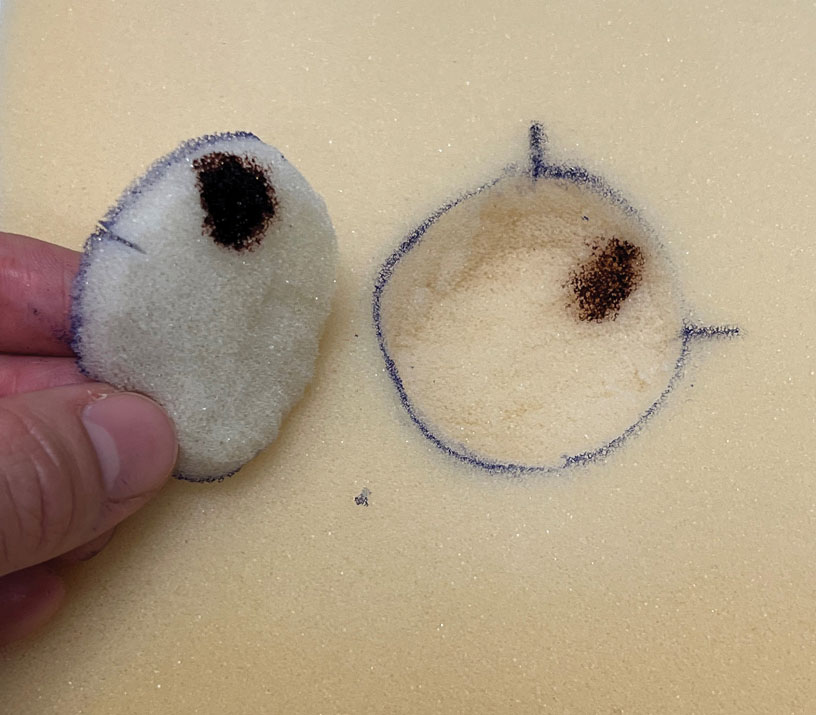

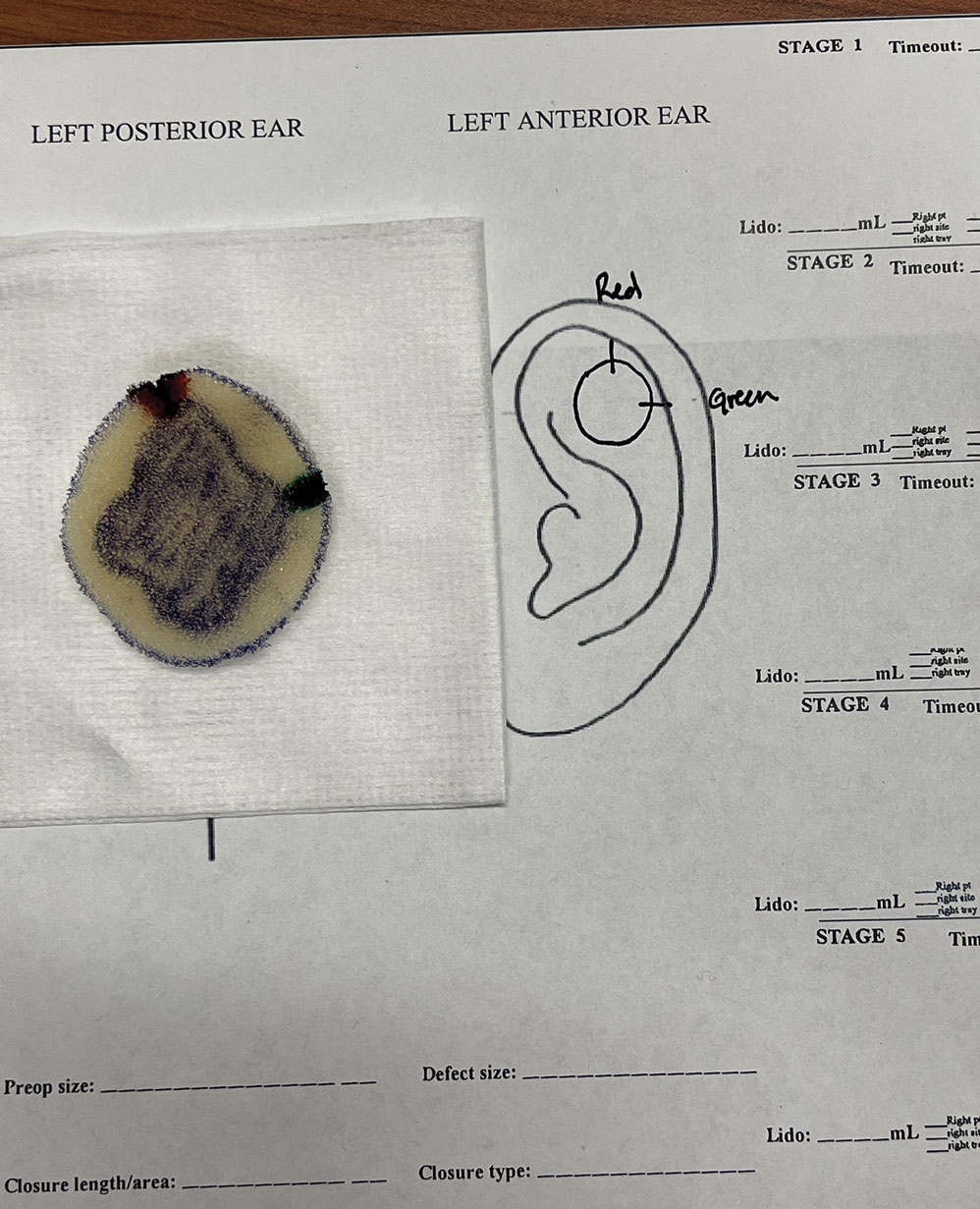

The biopsy results demonstrated a nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, including few multinucleated histiocytes, a surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate, mostly mature lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and fragmented neutrophils. A special stain panel was negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff for fungi. Bacterial cultures from biopsy tissue grew normal skin flora, and both fungal and AFB cultures were negative. A second punch biopsy was recommended by infectious disease due to clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Histopathology showed nonnecrotizing granulomas with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and negative Giemsa staining for Leishmania amastigotes; however, it was concluded by pathology that the reason for the negative Leishmania staining was the late stage of the disease, indicated by the presence of granulomas, which can make visualization of organisms difficult. Nonetheless, universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was positive for Leishmania tropica. Thus, although microscopic analysis was negative for visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, molecular analysis via PCR ultimately demonstrated a positive result and confirmed the diagnosis of CL (Figure 1). The variance in diagnostic accuracy exemplified in our case reinforces the need for multimodal diagnosis.

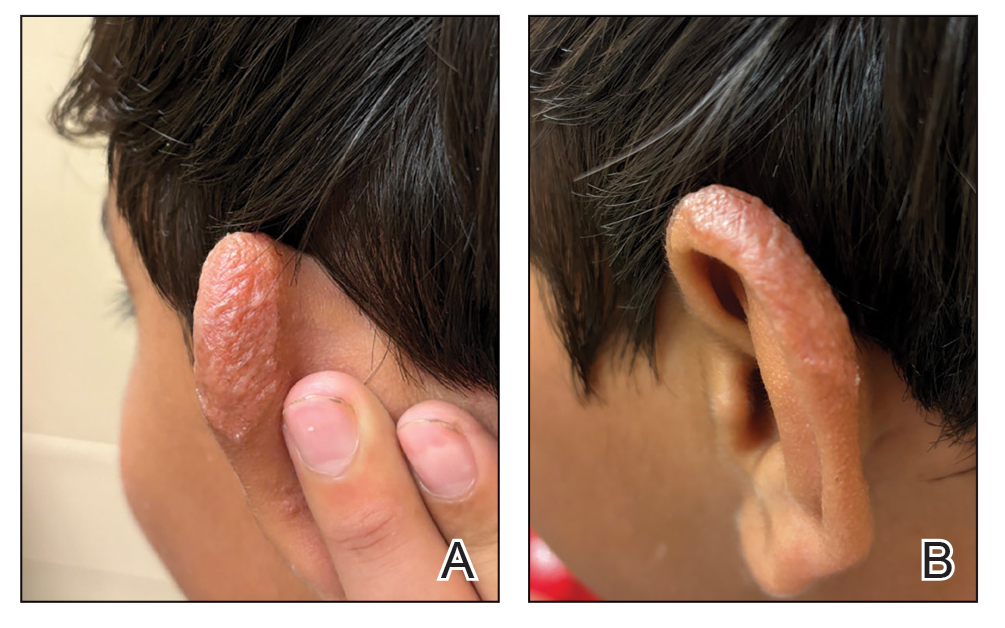

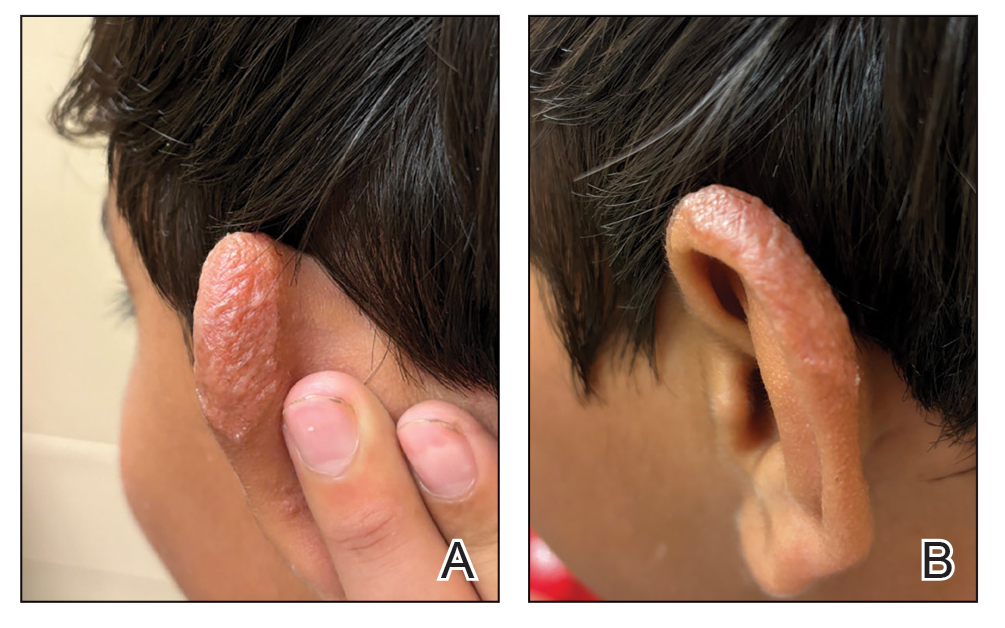

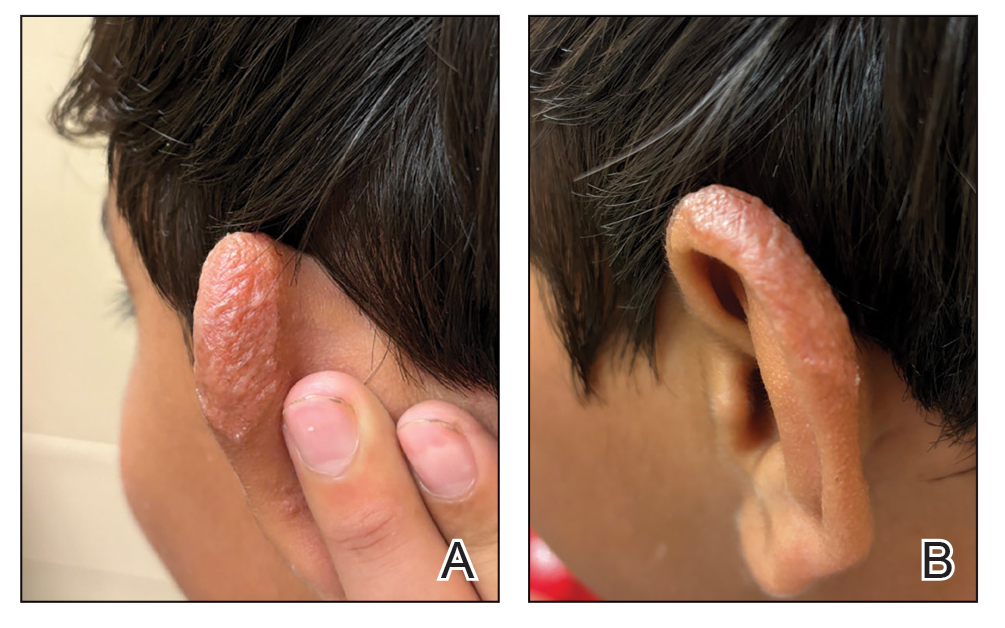

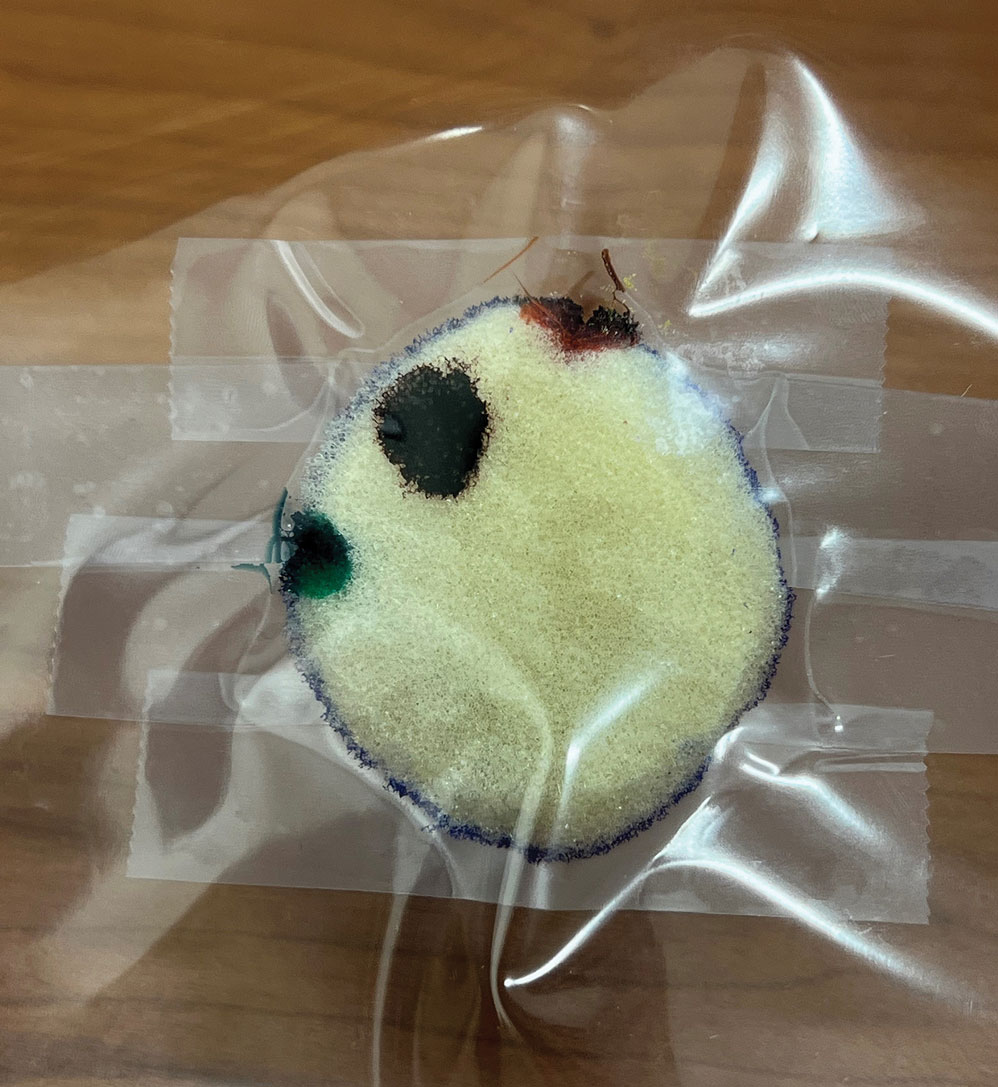

Multiple factors needed to be considered with regard to treatment in our patient, including but not limited to the location of the lesion on a slow-healing cartilaginous surface and the patient’s age. Considering the recalcitrant nature of the lesion and the L tropica strain exhibiting resistance to topical treatments, systemic therapies were the only option. Furthermore, parenteral routes of administration were confounded by the patient’s age, decreasing the likelihood of compliance with therapy. With these variables in mind and recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the best treatment for our patient was deemed to be a 28-day course of oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily. Compared to the initial presentation, a 1-month follow-up visit after completing the 28-day course of treatment demonstrated flattening of the lesion (Figure 2).

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by a protozoan parasite of the Leishmania genus, spread via inoculation from the bite of sandfly vectors.1 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common clinical manifestation of leishmaniasis. Other clinical manifestations include mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis.1,2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis typically manifests as open wounds on areas of skin that may have been exposed to sandfly bites.3 The lesion may not appear until weeks to months or even years after the initial inoculation.2 Initially, CL manifests as papules that may progress to nodular plaques, with eventual evolution to volcanic ulcerations with raised borders and central crateriform indentations covered by scabs or crusting.2,3 The infection may be localized or diffuse—in either case, development of satellite lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and/or nodular lymphangitis is not uncommon. Generally, CL is not lethal, but the severity of the lesions may vary and can lead to permanent scarring and atrophy.2 Many cases of CL remain undiagnosed because of its appearance as a nonspecific ulcer that can mimic many other cutaneous lesions and because it generally heals spontaneously, leaving only scarring as an indicator of prior infection.4 Thus, CL requires a high diagnostic suspicion, as it can have a nonspecific presentation and is rare in nonendemic regions.

Diagnosis of CL is accomplished via microscopy, isoenzyme analysis, or serology or is made molecularly.3 Microscopic diagnosis includes visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, the stage of replication that occurs after the promastigote stage is phagocytosed by macrophages.3 Amastigote is the only stage that can be visualized in human tissue and is stained via Giemsa and/or hematoxylin and eosin.3 However, Leishmania amastigotes are morphologically indistinguishable from Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes on microscopy, thus limiting diagnostic accuracy.3 Moreover, there is potential for missed diagnosis of persistent CL caused by L tropica due to fewer parasites being present, further complicating the diagnosis.5 In these cases, molecular diagnostics are helpful as they have higher sensitivity and quicker results. Additionally, DNA technologies can differentiate strains, which is beneficial for guiding treatment. Isoenzyme analysis also can help identify Leishmania species, although results can take weeks to return.3 Serologic testing is useful for suspected visceral leishmaniasis despite negative definitive diagnoses or conflicts with conducting definitive studies; however, there is not a strong antibody response in CL, thus serology is ineffective.3,5 Furthermore, serology can have cross-reactivity with T cruzi and cannot be used to assess for treatment response.3,5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis of leishmaniasis recommend using multiple methods to ensure a positive result, with molecular assays being the most sensitive.5

Differential diagnoses include any cause of cutaneous ulcerated lesions, including but not limited to mycobacterial or fungal infections. Leprosy often initially manifests with a hypopigmented macule with a raised border, although there often are associated neuropathic symptoms.6 Cutaneous tuberculosis is an extremely rare manifestation that occurs via direct inoculation of the mycobacterium, occurring primarily in children. Initially, it may manifest as a firm red papule that progresses to a painless shallow ulcer with a granular base.7 Cutaneous chromoblastomycosis is a fungal infection resulting from an initial cutaneous injury, similar to our patient, followed by a slow-developing warty lesion that may heal into ivory scars or spread as plaques on normal skin.8 The verrucous lesions seen in cutaneous chromoblastomycosis tend to manifest on the lower extremities and are unlikely to manifest on the head. Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous skin eruption that can be clinically nonspecific.9 Histologically, lesions may demonstrate noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, as seen with cutaneous leishmaniasis, with a broad presentation; for example, lupus pernio, a sarcoid variant, manifests as large blue-red dusky nodules/plaques on the face, ears, or digits.9 Other sarcoid lesions include red/brown, thickened, circular plaques; variably discolored papulonodular lesions; or mucosal involvement.9 Ultimately, it is important to differentiate these nonspecific and similarly appearing lesions through diagnostic techniques such as AFB culture and smear, fungal staining, tuberculosis testing, and PCR in more challenging cases.

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis should be individualized to each case.5 A more than 50% reduction in lesion size within 4 to 6 weeks indicates successful treatment. Ulcerated lesions should be fully re-epithelialized and healed by 3 months posttreatment. Treatment failure is categorized by failure of reepithelization, incomplete healing by 3 months, or worsening of the lesion at any time, each necessitating additional treatment, such as a second course of miltefosine or a different medication regimen.5 Careful monitoring is required throughout treatment, assessing for treatment failure, adding to the challenges of leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, CL requires a high index of suspicion in nonendemic areas to ensure successful diagnosis and treatment. Our case highlights the importance of using multimodal diagnostic techniques for CL, as a single modality may not exhibit a positive result due to variations in diagnostic accuracy. Our case also exhibits the complex treatment of CL, and the considerations that should be made when choosing a treatment modality.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Clinical overview of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/leishmaniasis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- CDC DPDx Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

- Stark CG. Leishmaniasis differential diagnoses. Medscape. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/220298-differential

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:E202-E264. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw670

- Lewis FS. Dermatologic manifestations of leprosy. Medscape. June 19, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104977-overview

- Ngan V. Cutaneous tuberculosis. DermNet. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis

- Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis. Medscape. May 13, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-overview#a4

- Elyoussfi S, Coulson I. Sarcoidosis. DermNet. May 31, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sarcoidosis

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results demonstrated a nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, including few multinucleated histiocytes, a surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate, mostly mature lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and fragmented neutrophils. A special stain panel was negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff for fungi. Bacterial cultures from biopsy tissue grew normal skin flora, and both fungal and AFB cultures were negative. A second punch biopsy was recommended by infectious disease due to clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Histopathology showed nonnecrotizing granulomas with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and negative Giemsa staining for Leishmania amastigotes; however, it was concluded by pathology that the reason for the negative Leishmania staining was the late stage of the disease, indicated by the presence of granulomas, which can make visualization of organisms difficult. Nonetheless, universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was positive for Leishmania tropica. Thus, although microscopic analysis was negative for visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, molecular analysis via PCR ultimately demonstrated a positive result and confirmed the diagnosis of CL (Figure 1). The variance in diagnostic accuracy exemplified in our case reinforces the need for multimodal diagnosis.

Multiple factors needed to be considered with regard to treatment in our patient, including but not limited to the location of the lesion on a slow-healing cartilaginous surface and the patient’s age. Considering the recalcitrant nature of the lesion and the L tropica strain exhibiting resistance to topical treatments, systemic therapies were the only option. Furthermore, parenteral routes of administration were confounded by the patient’s age, decreasing the likelihood of compliance with therapy. With these variables in mind and recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the best treatment for our patient was deemed to be a 28-day course of oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily. Compared to the initial presentation, a 1-month follow-up visit after completing the 28-day course of treatment demonstrated flattening of the lesion (Figure 2).

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by a protozoan parasite of the Leishmania genus, spread via inoculation from the bite of sandfly vectors.1 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common clinical manifestation of leishmaniasis. Other clinical manifestations include mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis.1,2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis typically manifests as open wounds on areas of skin that may have been exposed to sandfly bites.3 The lesion may not appear until weeks to months or even years after the initial inoculation.2 Initially, CL manifests as papules that may progress to nodular plaques, with eventual evolution to volcanic ulcerations with raised borders and central crateriform indentations covered by scabs or crusting.2,3 The infection may be localized or diffuse—in either case, development of satellite lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and/or nodular lymphangitis is not uncommon. Generally, CL is not lethal, but the severity of the lesions may vary and can lead to permanent scarring and atrophy.2 Many cases of CL remain undiagnosed because of its appearance as a nonspecific ulcer that can mimic many other cutaneous lesions and because it generally heals spontaneously, leaving only scarring as an indicator of prior infection.4 Thus, CL requires a high diagnostic suspicion, as it can have a nonspecific presentation and is rare in nonendemic regions.

Diagnosis of CL is accomplished via microscopy, isoenzyme analysis, or serology or is made molecularly.3 Microscopic diagnosis includes visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, the stage of replication that occurs after the promastigote stage is phagocytosed by macrophages.3 Amastigote is the only stage that can be visualized in human tissue and is stained via Giemsa and/or hematoxylin and eosin.3 However, Leishmania amastigotes are morphologically indistinguishable from Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes on microscopy, thus limiting diagnostic accuracy.3 Moreover, there is potential for missed diagnosis of persistent CL caused by L tropica due to fewer parasites being present, further complicating the diagnosis.5 In these cases, molecular diagnostics are helpful as they have higher sensitivity and quicker results. Additionally, DNA technologies can differentiate strains, which is beneficial for guiding treatment. Isoenzyme analysis also can help identify Leishmania species, although results can take weeks to return.3 Serologic testing is useful for suspected visceral leishmaniasis despite negative definitive diagnoses or conflicts with conducting definitive studies; however, there is not a strong antibody response in CL, thus serology is ineffective.3,5 Furthermore, serology can have cross-reactivity with T cruzi and cannot be used to assess for treatment response.3,5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis of leishmaniasis recommend using multiple methods to ensure a positive result, with molecular assays being the most sensitive.5

Differential diagnoses include any cause of cutaneous ulcerated lesions, including but not limited to mycobacterial or fungal infections. Leprosy often initially manifests with a hypopigmented macule with a raised border, although there often are associated neuropathic symptoms.6 Cutaneous tuberculosis is an extremely rare manifestation that occurs via direct inoculation of the mycobacterium, occurring primarily in children. Initially, it may manifest as a firm red papule that progresses to a painless shallow ulcer with a granular base.7 Cutaneous chromoblastomycosis is a fungal infection resulting from an initial cutaneous injury, similar to our patient, followed by a slow-developing warty lesion that may heal into ivory scars or spread as plaques on normal skin.8 The verrucous lesions seen in cutaneous chromoblastomycosis tend to manifest on the lower extremities and are unlikely to manifest on the head. Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous skin eruption that can be clinically nonspecific.9 Histologically, lesions may demonstrate noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, as seen with cutaneous leishmaniasis, with a broad presentation; for example, lupus pernio, a sarcoid variant, manifests as large blue-red dusky nodules/plaques on the face, ears, or digits.9 Other sarcoid lesions include red/brown, thickened, circular plaques; variably discolored papulonodular lesions; or mucosal involvement.9 Ultimately, it is important to differentiate these nonspecific and similarly appearing lesions through diagnostic techniques such as AFB culture and smear, fungal staining, tuberculosis testing, and PCR in more challenging cases.

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis should be individualized to each case.5 A more than 50% reduction in lesion size within 4 to 6 weeks indicates successful treatment. Ulcerated lesions should be fully re-epithelialized and healed by 3 months posttreatment. Treatment failure is categorized by failure of reepithelization, incomplete healing by 3 months, or worsening of the lesion at any time, each necessitating additional treatment, such as a second course of miltefosine or a different medication regimen.5 Careful monitoring is required throughout treatment, assessing for treatment failure, adding to the challenges of leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, CL requires a high index of suspicion in nonendemic areas to ensure successful diagnosis and treatment. Our case highlights the importance of using multimodal diagnostic techniques for CL, as a single modality may not exhibit a positive result due to variations in diagnostic accuracy. Our case also exhibits the complex treatment of CL, and the considerations that should be made when choosing a treatment modality.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results demonstrated a nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, including few multinucleated histiocytes, a surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate, mostly mature lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and fragmented neutrophils. A special stain panel was negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff for fungi. Bacterial cultures from biopsy tissue grew normal skin flora, and both fungal and AFB cultures were negative. A second punch biopsy was recommended by infectious disease due to clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Histopathology showed nonnecrotizing granulomas with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and negative Giemsa staining for Leishmania amastigotes; however, it was concluded by pathology that the reason for the negative Leishmania staining was the late stage of the disease, indicated by the presence of granulomas, which can make visualization of organisms difficult. Nonetheless, universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was positive for Leishmania tropica. Thus, although microscopic analysis was negative for visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, molecular analysis via PCR ultimately demonstrated a positive result and confirmed the diagnosis of CL (Figure 1). The variance in diagnostic accuracy exemplified in our case reinforces the need for multimodal diagnosis.

Multiple factors needed to be considered with regard to treatment in our patient, including but not limited to the location of the lesion on a slow-healing cartilaginous surface and the patient’s age. Considering the recalcitrant nature of the lesion and the L tropica strain exhibiting resistance to topical treatments, systemic therapies were the only option. Furthermore, parenteral routes of administration were confounded by the patient’s age, decreasing the likelihood of compliance with therapy. With these variables in mind and recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the best treatment for our patient was deemed to be a 28-day course of oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily. Compared to the initial presentation, a 1-month follow-up visit after completing the 28-day course of treatment demonstrated flattening of the lesion (Figure 2).

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by a protozoan parasite of the Leishmania genus, spread via inoculation from the bite of sandfly vectors.1 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common clinical manifestation of leishmaniasis. Other clinical manifestations include mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis.1,2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis typically manifests as open wounds on areas of skin that may have been exposed to sandfly bites.3 The lesion may not appear until weeks to months or even years after the initial inoculation.2 Initially, CL manifests as papules that may progress to nodular plaques, with eventual evolution to volcanic ulcerations with raised borders and central crateriform indentations covered by scabs or crusting.2,3 The infection may be localized or diffuse—in either case, development of satellite lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and/or nodular lymphangitis is not uncommon. Generally, CL is not lethal, but the severity of the lesions may vary and can lead to permanent scarring and atrophy.2 Many cases of CL remain undiagnosed because of its appearance as a nonspecific ulcer that can mimic many other cutaneous lesions and because it generally heals spontaneously, leaving only scarring as an indicator of prior infection.4 Thus, CL requires a high diagnostic suspicion, as it can have a nonspecific presentation and is rare in nonendemic regions.

Diagnosis of CL is accomplished via microscopy, isoenzyme analysis, or serology or is made molecularly.3 Microscopic diagnosis includes visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, the stage of replication that occurs after the promastigote stage is phagocytosed by macrophages.3 Amastigote is the only stage that can be visualized in human tissue and is stained via Giemsa and/or hematoxylin and eosin.3 However, Leishmania amastigotes are morphologically indistinguishable from Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes on microscopy, thus limiting diagnostic accuracy.3 Moreover, there is potential for missed diagnosis of persistent CL caused by L tropica due to fewer parasites being present, further complicating the diagnosis.5 In these cases, molecular diagnostics are helpful as they have higher sensitivity and quicker results. Additionally, DNA technologies can differentiate strains, which is beneficial for guiding treatment. Isoenzyme analysis also can help identify Leishmania species, although results can take weeks to return.3 Serologic testing is useful for suspected visceral leishmaniasis despite negative definitive diagnoses or conflicts with conducting definitive studies; however, there is not a strong antibody response in CL, thus serology is ineffective.3,5 Furthermore, serology can have cross-reactivity with T cruzi and cannot be used to assess for treatment response.3,5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis of leishmaniasis recommend using multiple methods to ensure a positive result, with molecular assays being the most sensitive.5

Differential diagnoses include any cause of cutaneous ulcerated lesions, including but not limited to mycobacterial or fungal infections. Leprosy often initially manifests with a hypopigmented macule with a raised border, although there often are associated neuropathic symptoms.6 Cutaneous tuberculosis is an extremely rare manifestation that occurs via direct inoculation of the mycobacterium, occurring primarily in children. Initially, it may manifest as a firm red papule that progresses to a painless shallow ulcer with a granular base.7 Cutaneous chromoblastomycosis is a fungal infection resulting from an initial cutaneous injury, similar to our patient, followed by a slow-developing warty lesion that may heal into ivory scars or spread as plaques on normal skin.8 The verrucous lesions seen in cutaneous chromoblastomycosis tend to manifest on the lower extremities and are unlikely to manifest on the head. Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous skin eruption that can be clinically nonspecific.9 Histologically, lesions may demonstrate noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, as seen with cutaneous leishmaniasis, with a broad presentation; for example, lupus pernio, a sarcoid variant, manifests as large blue-red dusky nodules/plaques on the face, ears, or digits.9 Other sarcoid lesions include red/brown, thickened, circular plaques; variably discolored papulonodular lesions; or mucosal involvement.9 Ultimately, it is important to differentiate these nonspecific and similarly appearing lesions through diagnostic techniques such as AFB culture and smear, fungal staining, tuberculosis testing, and PCR in more challenging cases.

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis should be individualized to each case.5 A more than 50% reduction in lesion size within 4 to 6 weeks indicates successful treatment. Ulcerated lesions should be fully re-epithelialized and healed by 3 months posttreatment. Treatment failure is categorized by failure of reepithelization, incomplete healing by 3 months, or worsening of the lesion at any time, each necessitating additional treatment, such as a second course of miltefosine or a different medication regimen.5 Careful monitoring is required throughout treatment, assessing for treatment failure, adding to the challenges of leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, CL requires a high index of suspicion in nonendemic areas to ensure successful diagnosis and treatment. Our case highlights the importance of using multimodal diagnostic techniques for CL, as a single modality may not exhibit a positive result due to variations in diagnostic accuracy. Our case also exhibits the complex treatment of CL, and the considerations that should be made when choosing a treatment modality.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Clinical overview of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/leishmaniasis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- CDC DPDx Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

- Stark CG. Leishmaniasis differential diagnoses. Medscape. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/220298-differential

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:E202-E264. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw670

- Lewis FS. Dermatologic manifestations of leprosy. Medscape. June 19, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104977-overview

- Ngan V. Cutaneous tuberculosis. DermNet. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis

- Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis. Medscape. May 13, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-overview#a4

- Elyoussfi S, Coulson I. Sarcoidosis. DermNet. May 31, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sarcoidosis

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Clinical overview of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/leishmaniasis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- CDC DPDx Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

- Stark CG. Leishmaniasis differential diagnoses. Medscape. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/220298-differential

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:E202-E264. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw670

- Lewis FS. Dermatologic manifestations of leprosy. Medscape. June 19, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104977-overview

- Ngan V. Cutaneous tuberculosis. DermNet. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis

- Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis. Medscape. May 13, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-overview#a4

- Elyoussfi S, Coulson I. Sarcoidosis. DermNet. May 31, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sarcoidosis

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

A 10-year-old boy who recently emigrated from Afghanistan presented to his pediatrician for evaluation of a painless nonhealing plaque on the posterior left pinna of more than 1 year's duration. The lesion reportedly started as a small scratch following an ear injury, initially improved with an unknown topical treatment administered in Afghanistan, and then recurred with no other associated lesions and no known insect bite. The lesion persisted for more than 1 year postemigration before the patient presented to his pediatrician, who noted signs of excoriation, which was confirmed by the patient's father. The patient was started on a 7-day course of cephalexin oral suspension and topical mupirocin 2%. After 2 months without improvement, a 2-week course of oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was initiated; however, the lesion continued to grow with no signs of healing, and he was referred to dermatology.

The patient presented to pediatric dermatology 3 months after the initial presentation to his pediatrician and 2 weeks after he completed the course of oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Physical examination demonstrated a papulosquamous eruption with swelling and blistering on the helix of the left ear. Based on these findings, the patient was started on a 1-month trial of topical triamcinolone 1% followed by the addition of topical pimecrolimus 1%. Due to no improvement of the lesion and subsequent progression to ulceration, a punch biopsy was performed.

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

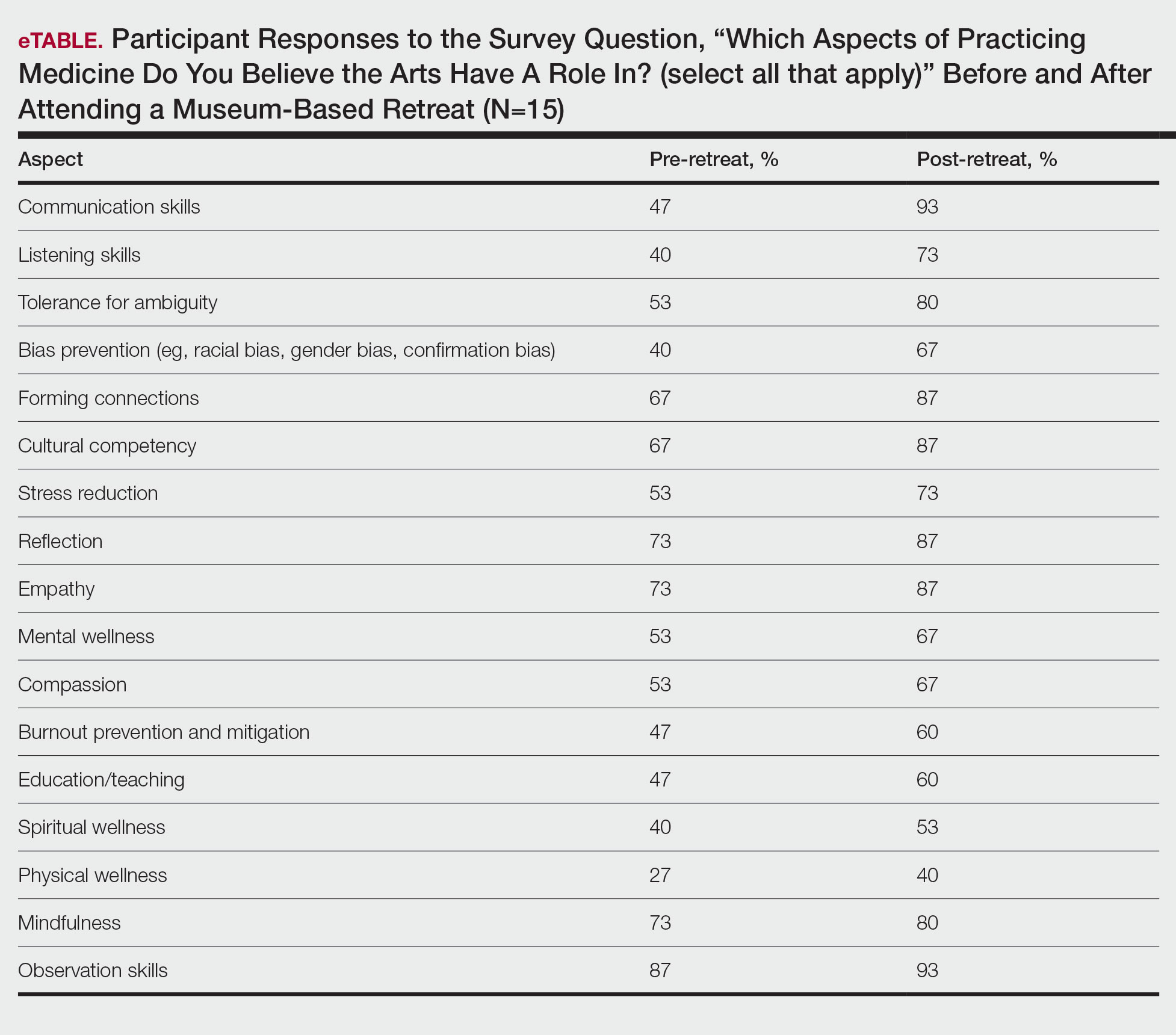

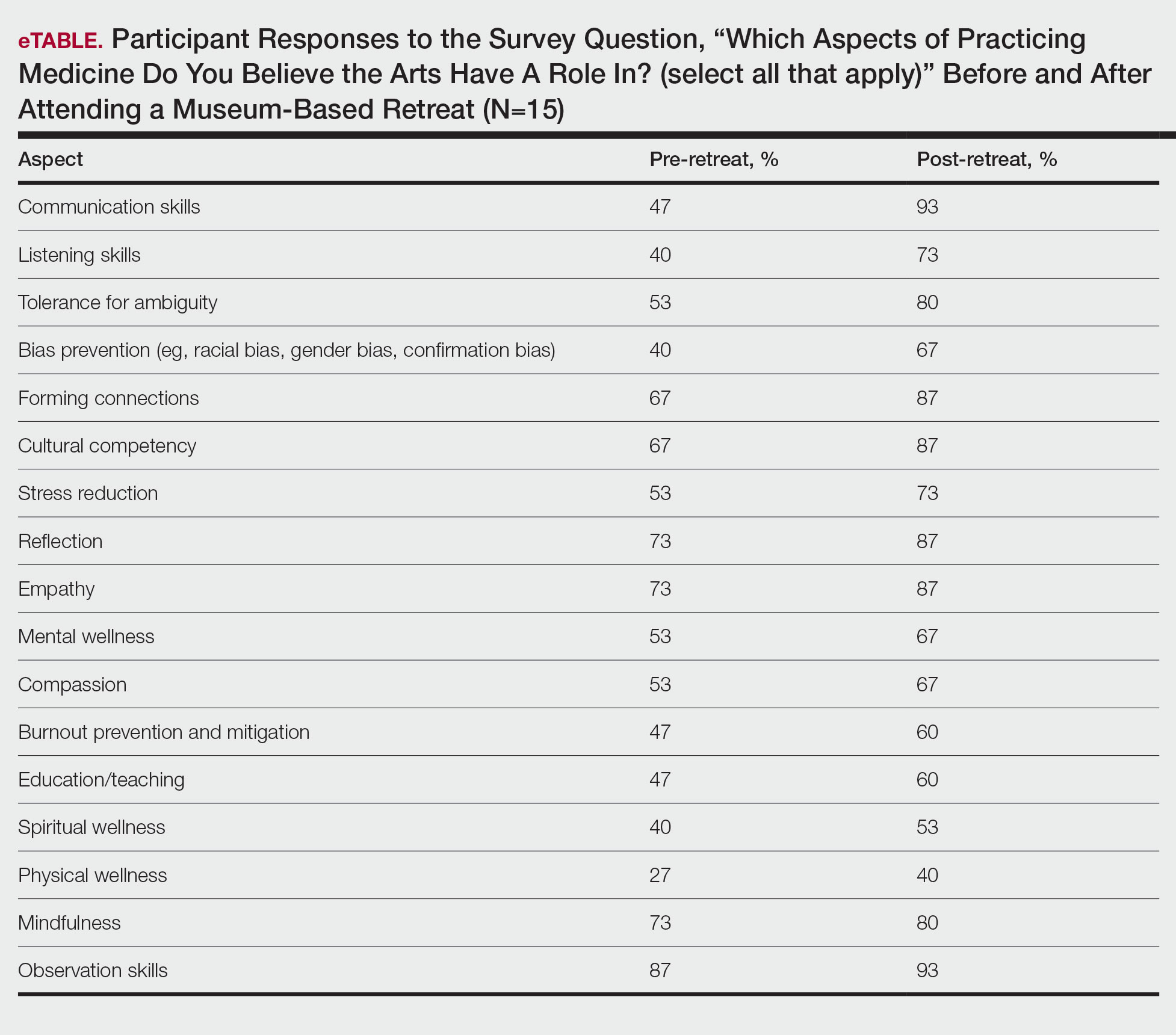

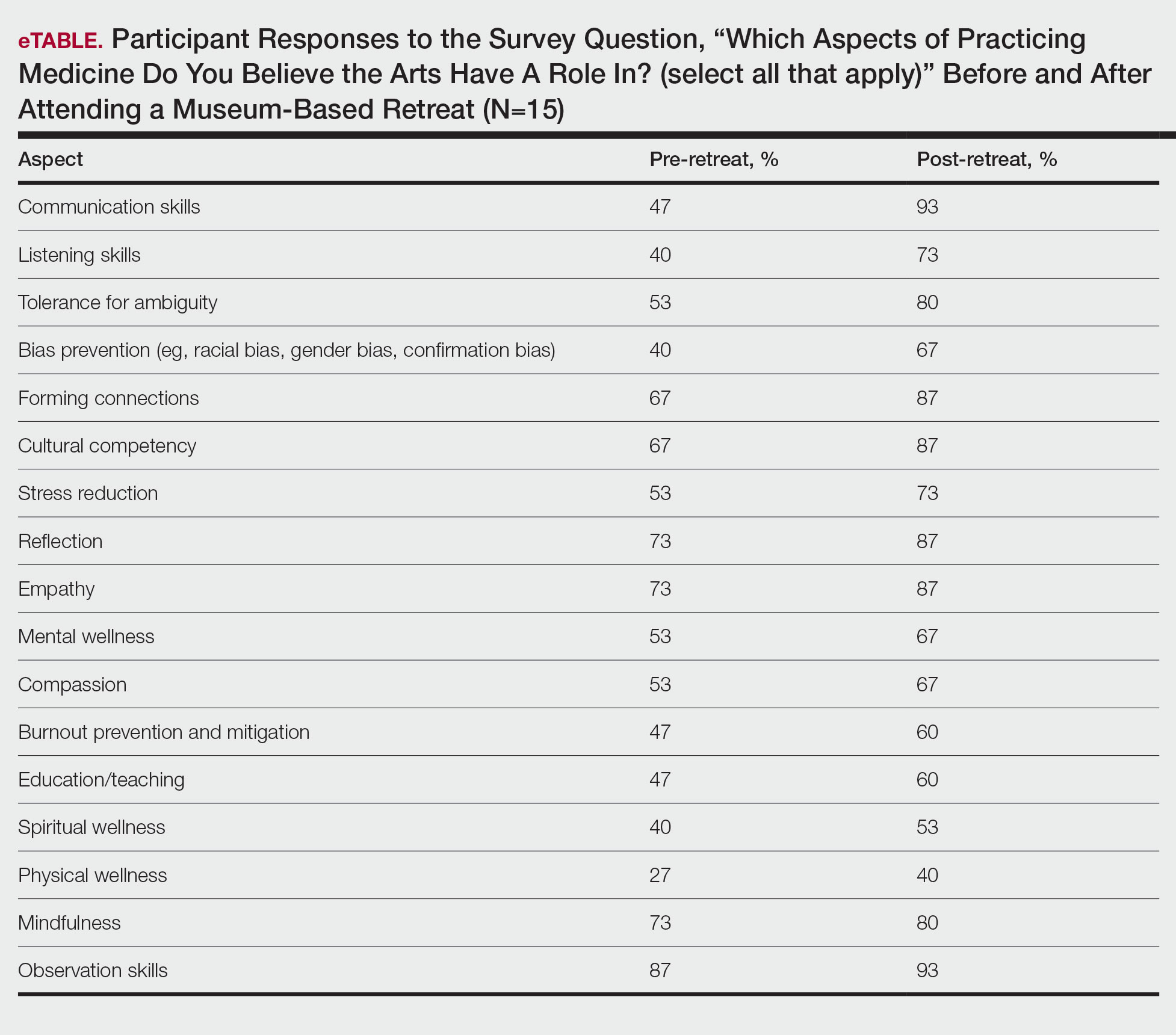

Results

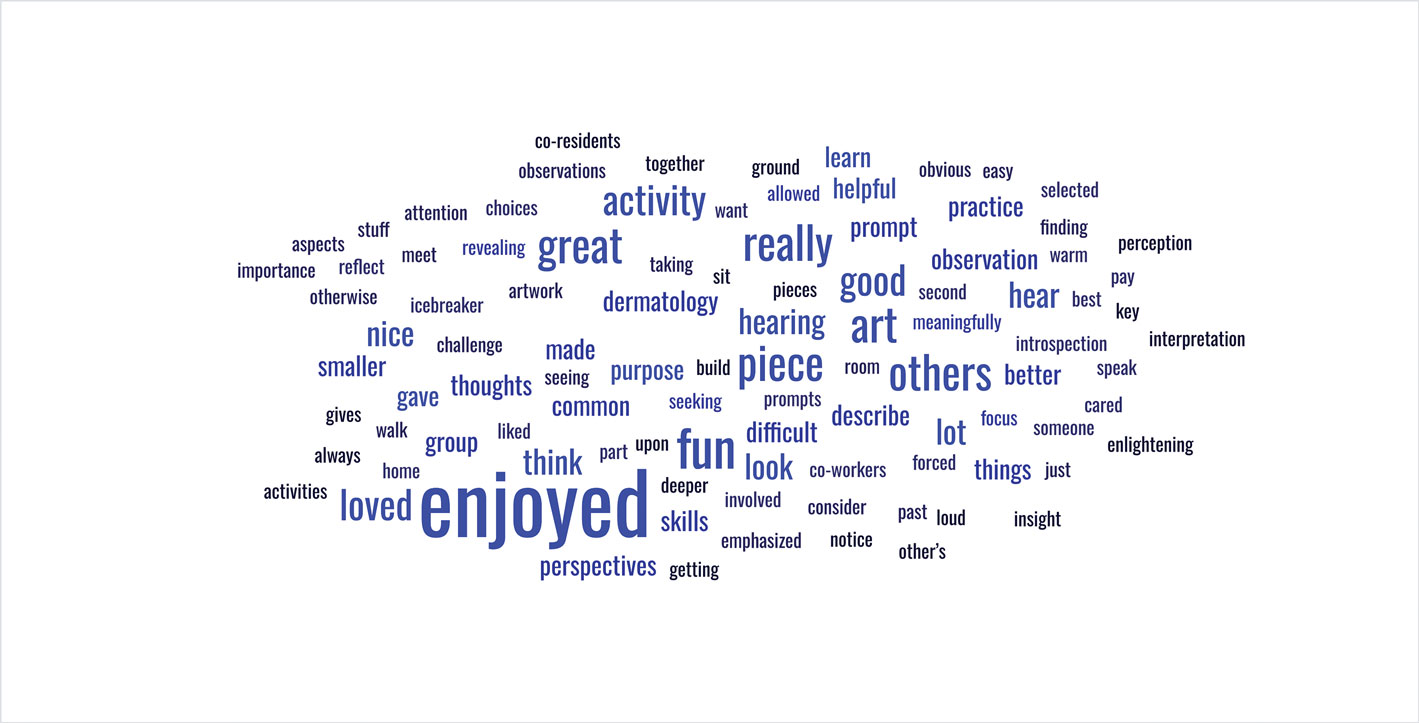

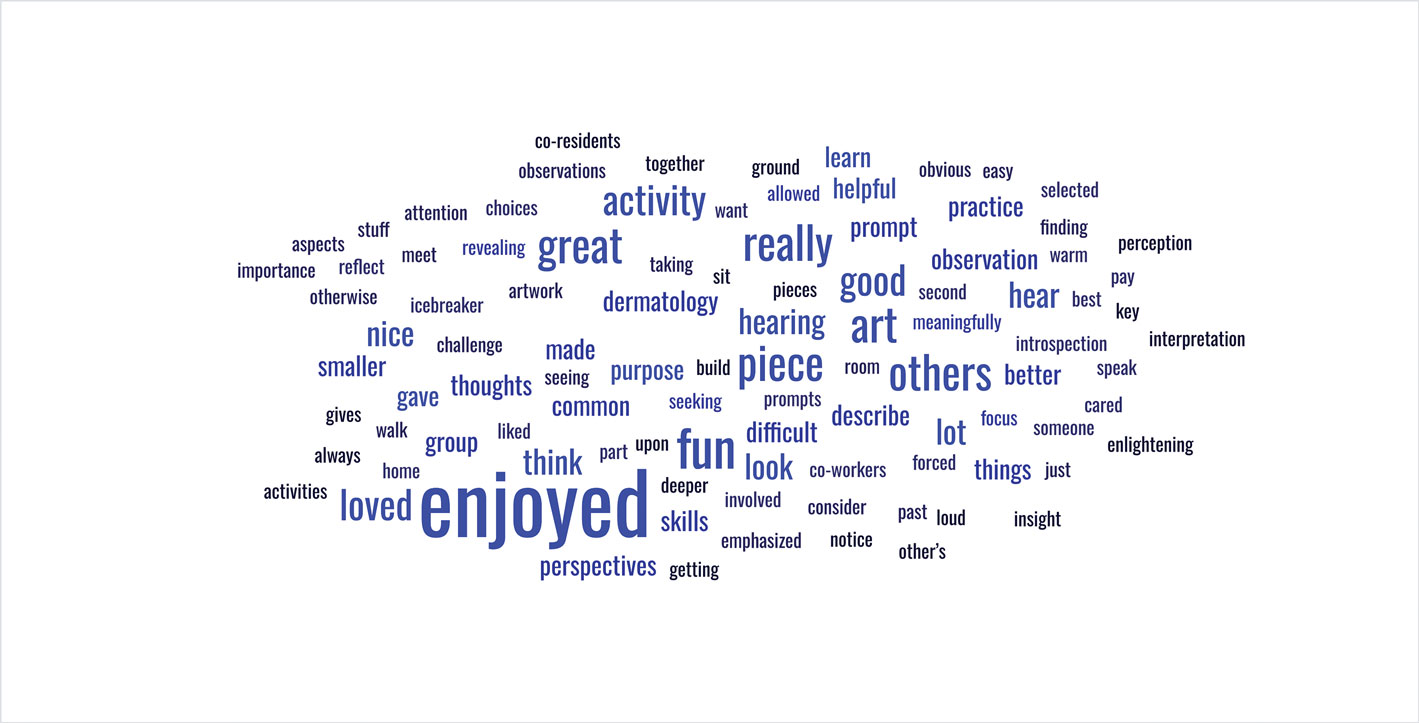

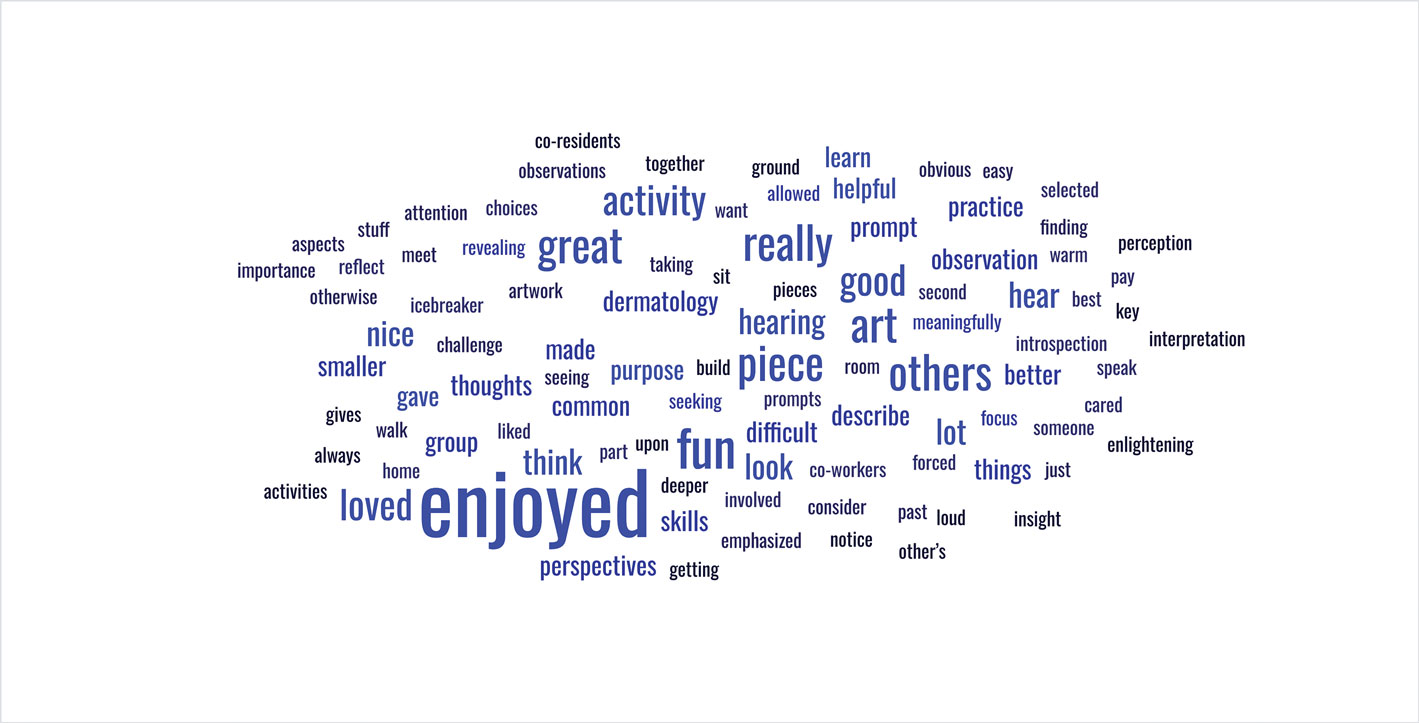

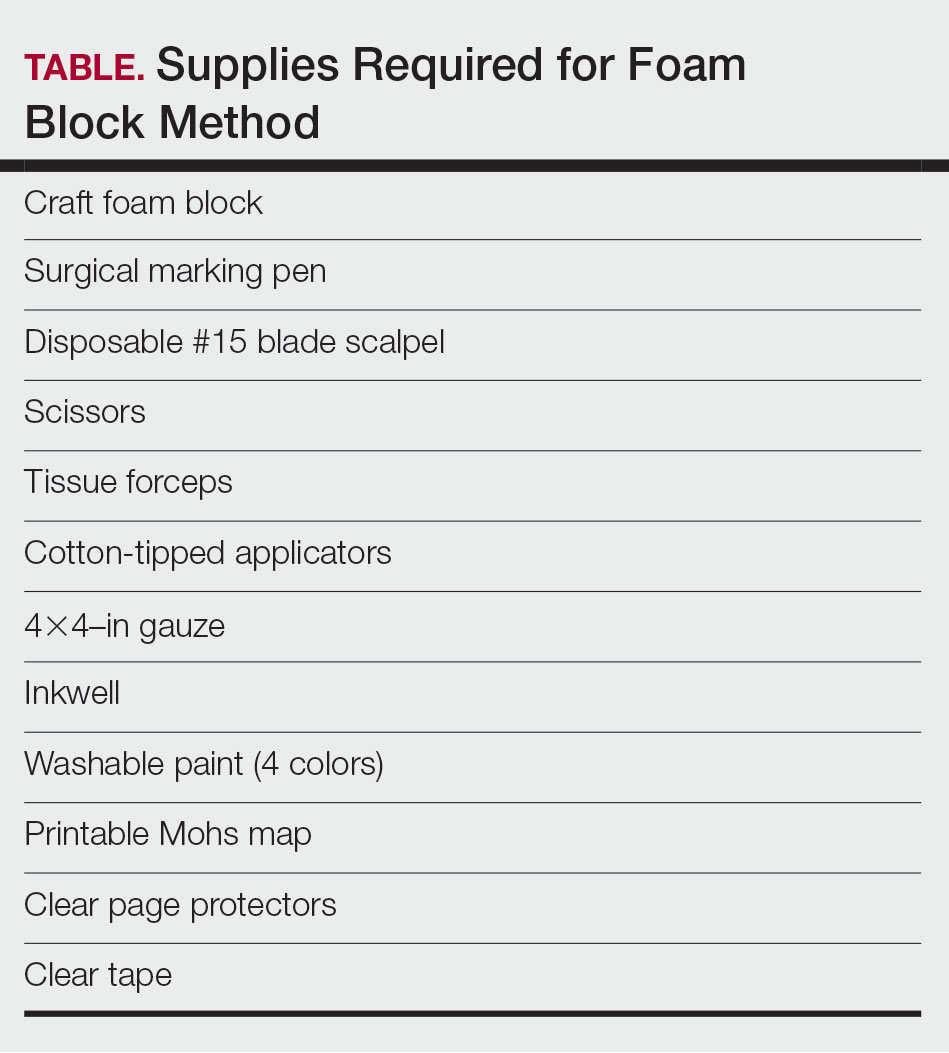

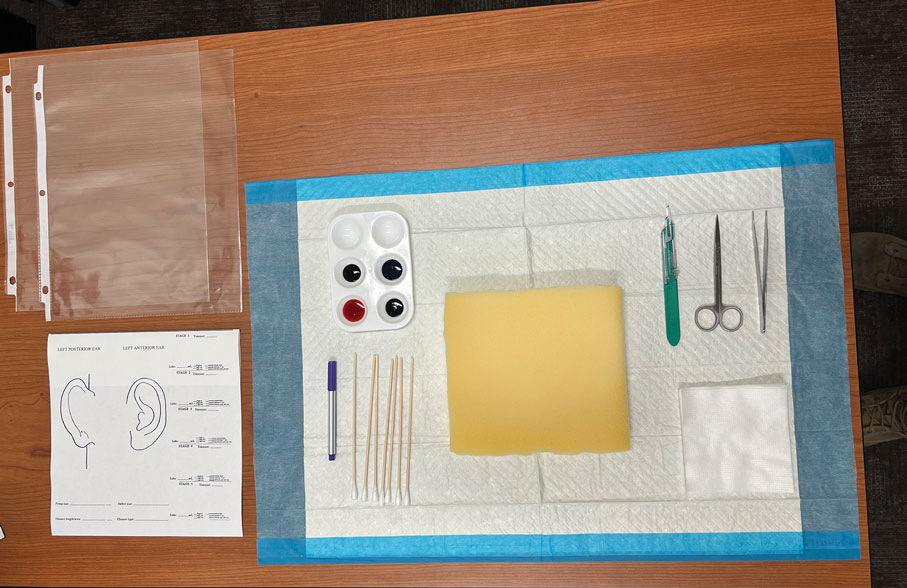

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods