User login

Glycobiology and the Skin: A New Frontier

Pigmentation Concerns: Assessment and Treatment [editorial]

Supplement boosts hair growth in women

A marine protein–based oral food supplement was safe and associated with significant hair growth in women with self-perceived thinning hair, according to findings from a small randomized controlled, double-blind study.

The mean number of terminal hairs in a 4 cm2 area at the junction of the frontal and lateral hairlines was measured. In 10 women randomized to receive the supplement, terminal hairs increased from 271 at baseline to 571 after 90 days of treatment and 610 after 180 days of treatment. The mean number of terminal hairs in five women randomized to receive placebo was 256 at baseline, 245 after 90 days, and 242 after 180 days, Dr. Glynis Ablon reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The mean number of vellus hairs in the treatment group was 46.5 at baseline and did not appreciably change over 180 days; the mean number of vellus hairs in the placebo group was 57 at baseline, 68 at 90 days, and 66 at 180 days, said Dr. Ablon, a Manhattan Beach, Calif.–based dermatologist.

Treated subjects were significantly more likely to report improvements in overall hair volume, scalp coverage, and hair body thickness after 90 days. Improved hair shine, skin moisture retention, and skin smoothness were reported after 180 days, she noted.

Study participants were women aged 21-75 years (mean age, 50 in the treatment group and 48 in the control group) with Fitzpatrick I-IV skin types. All were in generally good health but had perceived hair thinning. All study participants agreed to maintain their baseline diet, medications, and exercise level during the study period, and to maintain consistent hair care throughout the study period.

Treatment group subjects were instructed to take one tablet of the proprietary supplement (Viviscal) each morning and evening with water after a meal.

The study was supported by Lifes2good Inc., the maker of Viviscal. Dr. Ablon received a research grant from Lifes2good.

A marine protein–based oral food supplement was safe and associated with significant hair growth in women with self-perceived thinning hair, according to findings from a small randomized controlled, double-blind study.

The mean number of terminal hairs in a 4 cm2 area at the junction of the frontal and lateral hairlines was measured. In 10 women randomized to receive the supplement, terminal hairs increased from 271 at baseline to 571 after 90 days of treatment and 610 after 180 days of treatment. The mean number of terminal hairs in five women randomized to receive placebo was 256 at baseline, 245 after 90 days, and 242 after 180 days, Dr. Glynis Ablon reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The mean number of vellus hairs in the treatment group was 46.5 at baseline and did not appreciably change over 180 days; the mean number of vellus hairs in the placebo group was 57 at baseline, 68 at 90 days, and 66 at 180 days, said Dr. Ablon, a Manhattan Beach, Calif.–based dermatologist.

Treated subjects were significantly more likely to report improvements in overall hair volume, scalp coverage, and hair body thickness after 90 days. Improved hair shine, skin moisture retention, and skin smoothness were reported after 180 days, she noted.

Study participants were women aged 21-75 years (mean age, 50 in the treatment group and 48 in the control group) with Fitzpatrick I-IV skin types. All were in generally good health but had perceived hair thinning. All study participants agreed to maintain their baseline diet, medications, and exercise level during the study period, and to maintain consistent hair care throughout the study period.

Treatment group subjects were instructed to take one tablet of the proprietary supplement (Viviscal) each morning and evening with water after a meal.

The study was supported by Lifes2good Inc., the maker of Viviscal. Dr. Ablon received a research grant from Lifes2good.

A marine protein–based oral food supplement was safe and associated with significant hair growth in women with self-perceived thinning hair, according to findings from a small randomized controlled, double-blind study.

The mean number of terminal hairs in a 4 cm2 area at the junction of the frontal and lateral hairlines was measured. In 10 women randomized to receive the supplement, terminal hairs increased from 271 at baseline to 571 after 90 days of treatment and 610 after 180 days of treatment. The mean number of terminal hairs in five women randomized to receive placebo was 256 at baseline, 245 after 90 days, and 242 after 180 days, Dr. Glynis Ablon reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The mean number of vellus hairs in the treatment group was 46.5 at baseline and did not appreciably change over 180 days; the mean number of vellus hairs in the placebo group was 57 at baseline, 68 at 90 days, and 66 at 180 days, said Dr. Ablon, a Manhattan Beach, Calif.–based dermatologist.

Treated subjects were significantly more likely to report improvements in overall hair volume, scalp coverage, and hair body thickness after 90 days. Improved hair shine, skin moisture retention, and skin smoothness were reported after 180 days, she noted.

Study participants were women aged 21-75 years (mean age, 50 in the treatment group and 48 in the control group) with Fitzpatrick I-IV skin types. All were in generally good health but had perceived hair thinning. All study participants agreed to maintain their baseline diet, medications, and exercise level during the study period, and to maintain consistent hair care throughout the study period.

Treatment group subjects were instructed to take one tablet of the proprietary supplement (Viviscal) each morning and evening with water after a meal.

The study was supported by Lifes2good Inc., the maker of Viviscal. Dr. Ablon received a research grant from Lifes2good.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Major Finding: The mean number of anagen hairs in a prespecified 4 cm2 area of the scalps of 10 women randomized to receive the supplement increased from 271 at baseline to 610 at 180 days after treatment initiation. The mean number of anagen hairs in five women randomized to receive placebo remained essentially the same at 256 at baseline, 245 at 90 days, and 242 at 180 days.

Data Source: A randomized controlled, double-blind study.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Lifes2good Inc., the maker of Viviscal. Dr. Ablon received a research grant from Lifes2good.

No forehead paralysis seen after microdroplet technique

LAS VEGAS – A technique that involves injecting tiny, closely placed amounts of botulinum toxin A to balance the actions of the muscles around the eyebrows yielded natural-looking outcomes without forehead paralysis, based on data from a 5-year study.

"Doctors have mistakenly adopted maximal forehead paralysis as a desirable treatment endpoint," Dr. Kenneth D. Steinsapir said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery. "Forehead paralysis as a result of cosmetic botulinum toxin is feared by the public and lampooned by the media."

Over the years, onabotulinumtoxinA treatments have evolved to create maximal frontalis brow lifts while minimizing the risk of eyelid ptosis. As a result, "the forehead is smooth, but the central forehead is also ptotic," said Dr. Steinsapir of the department of ophthalmology at the University of California, Los Angeles. "There can be recruitment lines on the side of the forehead, which can make for an undesirable treatment effect."

In 2006, Dr. Steinsapir first described the microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift, a technique he developed for treating eyebrow depressors that leaves the brow elevator untreated. "I hypothesized that very small quantities of botulinum toxic can be injected and effectively trapped between the skin and the underlying orbicularis oculi muscle in the brow, and in the crow’s feet area as well," said Dr. Steinsapir, who also maintains a private cosmetic surgery practice in Beverly Hills, Calif. "This weakens the eyebrow depressors, allowing the frontalis muscle to lift unopposed, lifting the brows. Forehead movement is preserved and unwanted diffusion responsible for eyelid ptosis is prevented."

Between August 2006 and July 2011, Dr. Steinsapir performed 574 consecutive microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift treatments on 175 women and 53 men with a mean age of 45 years. A typical treatment involves 10 mcL of injectable saline containing 0.33 U of botulinum toxin A using the product formulation of Botox or Xeomin. About 100 microinjections are needed to complete the pattern, and all patients in the study received 33 units of Botox exclusively.

Dr. Steinsapir reported that there were no cases of treatment-induced upper eyelid or eyebrow ptosis or cases of diplopia, "which established that this treatment can be safely performed." Of the 574 patients, 49 returned for follow-up appointments between 10 and 45 days after treatment. Before and after images were used to assess the effect of treatment on the upper eyelid margin reflex distance, the tarsal platform show, and the brow position central to the cornea. Dr. Steinsapir used National Institutes of Health imaging software to perform quantitative image analysis and validated facial scales to assess the brow and forehead before and after treatment.

There was no significant change in the margin reflex distance after treatment in the 49 patients who returned for follow-up, Dr. Steinsapir said. "There was a slight trend to minimal brow elevation, and the tarsal platform show was essentially unchanged after treatment," he said. "It’s my clinical impression that the principal effect of the treatment is the softening of the brow pinch that commonly purses the brow and brings an unintentional negative affect to the face."

Dr. Steinsapir acknowledged that the procedure requires a learning curve "and a need to educate patients regarding the effect of treatment. This is more labor intensive than standard treatment methods." Dr. Steinsapir has developed a detailed training video that is available online on his website, and he said that he is working on a treatment atlas.

The microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift "presents the first alternative to standard periocular treatments that cause unwarranted forehead paralysis, brow flare, or muscle activation," Dr. Steinsapir said. "By controlling the depth, volume, and dose of agent, very controlled brow shaping and lifting can be performed to create aesthetic improvement with natural results, including preservation of forehead movement," he noted.

Dr. Steinsapir received a United States patent on the microdroplet method. He said that he hopes to license the technique to a drug company for the development of a Food and Drug Administration–approved indication, so the treatment can be directly marketed to consumers. He had no other relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Kenneth D. Steinsapir, American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery, cosmetic botulinum toxin, onabotulinumtoxinA, maximal frontalis brow lifts, eyelid ptosis, ptotic, microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift, eyebrow depressors,

LAS VEGAS – A technique that involves injecting tiny, closely placed amounts of botulinum toxin A to balance the actions of the muscles around the eyebrows yielded natural-looking outcomes without forehead paralysis, based on data from a 5-year study.

"Doctors have mistakenly adopted maximal forehead paralysis as a desirable treatment endpoint," Dr. Kenneth D. Steinsapir said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery. "Forehead paralysis as a result of cosmetic botulinum toxin is feared by the public and lampooned by the media."

Over the years, onabotulinumtoxinA treatments have evolved to create maximal frontalis brow lifts while minimizing the risk of eyelid ptosis. As a result, "the forehead is smooth, but the central forehead is also ptotic," said Dr. Steinsapir of the department of ophthalmology at the University of California, Los Angeles. "There can be recruitment lines on the side of the forehead, which can make for an undesirable treatment effect."

In 2006, Dr. Steinsapir first described the microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift, a technique he developed for treating eyebrow depressors that leaves the brow elevator untreated. "I hypothesized that very small quantities of botulinum toxic can be injected and effectively trapped between the skin and the underlying orbicularis oculi muscle in the brow, and in the crow’s feet area as well," said Dr. Steinsapir, who also maintains a private cosmetic surgery practice in Beverly Hills, Calif. "This weakens the eyebrow depressors, allowing the frontalis muscle to lift unopposed, lifting the brows. Forehead movement is preserved and unwanted diffusion responsible for eyelid ptosis is prevented."

Between August 2006 and July 2011, Dr. Steinsapir performed 574 consecutive microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift treatments on 175 women and 53 men with a mean age of 45 years. A typical treatment involves 10 mcL of injectable saline containing 0.33 U of botulinum toxin A using the product formulation of Botox or Xeomin. About 100 microinjections are needed to complete the pattern, and all patients in the study received 33 units of Botox exclusively.

Dr. Steinsapir reported that there were no cases of treatment-induced upper eyelid or eyebrow ptosis or cases of diplopia, "which established that this treatment can be safely performed." Of the 574 patients, 49 returned for follow-up appointments between 10 and 45 days after treatment. Before and after images were used to assess the effect of treatment on the upper eyelid margin reflex distance, the tarsal platform show, and the brow position central to the cornea. Dr. Steinsapir used National Institutes of Health imaging software to perform quantitative image analysis and validated facial scales to assess the brow and forehead before and after treatment.

There was no significant change in the margin reflex distance after treatment in the 49 patients who returned for follow-up, Dr. Steinsapir said. "There was a slight trend to minimal brow elevation, and the tarsal platform show was essentially unchanged after treatment," he said. "It’s my clinical impression that the principal effect of the treatment is the softening of the brow pinch that commonly purses the brow and brings an unintentional negative affect to the face."

Dr. Steinsapir acknowledged that the procedure requires a learning curve "and a need to educate patients regarding the effect of treatment. This is more labor intensive than standard treatment methods." Dr. Steinsapir has developed a detailed training video that is available online on his website, and he said that he is working on a treatment atlas.

The microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift "presents the first alternative to standard periocular treatments that cause unwarranted forehead paralysis, brow flare, or muscle activation," Dr. Steinsapir said. "By controlling the depth, volume, and dose of agent, very controlled brow shaping and lifting can be performed to create aesthetic improvement with natural results, including preservation of forehead movement," he noted.

Dr. Steinsapir received a United States patent on the microdroplet method. He said that he hopes to license the technique to a drug company for the development of a Food and Drug Administration–approved indication, so the treatment can be directly marketed to consumers. He had no other relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

LAS VEGAS – A technique that involves injecting tiny, closely placed amounts of botulinum toxin A to balance the actions of the muscles around the eyebrows yielded natural-looking outcomes without forehead paralysis, based on data from a 5-year study.

"Doctors have mistakenly adopted maximal forehead paralysis as a desirable treatment endpoint," Dr. Kenneth D. Steinsapir said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery. "Forehead paralysis as a result of cosmetic botulinum toxin is feared by the public and lampooned by the media."

Over the years, onabotulinumtoxinA treatments have evolved to create maximal frontalis brow lifts while minimizing the risk of eyelid ptosis. As a result, "the forehead is smooth, but the central forehead is also ptotic," said Dr. Steinsapir of the department of ophthalmology at the University of California, Los Angeles. "There can be recruitment lines on the side of the forehead, which can make for an undesirable treatment effect."

In 2006, Dr. Steinsapir first described the microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift, a technique he developed for treating eyebrow depressors that leaves the brow elevator untreated. "I hypothesized that very small quantities of botulinum toxic can be injected and effectively trapped between the skin and the underlying orbicularis oculi muscle in the brow, and in the crow’s feet area as well," said Dr. Steinsapir, who also maintains a private cosmetic surgery practice in Beverly Hills, Calif. "This weakens the eyebrow depressors, allowing the frontalis muscle to lift unopposed, lifting the brows. Forehead movement is preserved and unwanted diffusion responsible for eyelid ptosis is prevented."

Between August 2006 and July 2011, Dr. Steinsapir performed 574 consecutive microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift treatments on 175 women and 53 men with a mean age of 45 years. A typical treatment involves 10 mcL of injectable saline containing 0.33 U of botulinum toxin A using the product formulation of Botox or Xeomin. About 100 microinjections are needed to complete the pattern, and all patients in the study received 33 units of Botox exclusively.

Dr. Steinsapir reported that there were no cases of treatment-induced upper eyelid or eyebrow ptosis or cases of diplopia, "which established that this treatment can be safely performed." Of the 574 patients, 49 returned for follow-up appointments between 10 and 45 days after treatment. Before and after images were used to assess the effect of treatment on the upper eyelid margin reflex distance, the tarsal platform show, and the brow position central to the cornea. Dr. Steinsapir used National Institutes of Health imaging software to perform quantitative image analysis and validated facial scales to assess the brow and forehead before and after treatment.

There was no significant change in the margin reflex distance after treatment in the 49 patients who returned for follow-up, Dr. Steinsapir said. "There was a slight trend to minimal brow elevation, and the tarsal platform show was essentially unchanged after treatment," he said. "It’s my clinical impression that the principal effect of the treatment is the softening of the brow pinch that commonly purses the brow and brings an unintentional negative affect to the face."

Dr. Steinsapir acknowledged that the procedure requires a learning curve "and a need to educate patients regarding the effect of treatment. This is more labor intensive than standard treatment methods." Dr. Steinsapir has developed a detailed training video that is available online on his website, and he said that he is working on a treatment atlas.

The microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift "presents the first alternative to standard periocular treatments that cause unwarranted forehead paralysis, brow flare, or muscle activation," Dr. Steinsapir said. "By controlling the depth, volume, and dose of agent, very controlled brow shaping and lifting can be performed to create aesthetic improvement with natural results, including preservation of forehead movement," he noted.

Dr. Steinsapir received a United States patent on the microdroplet method. He said that he hopes to license the technique to a drug company for the development of a Food and Drug Administration–approved indication, so the treatment can be directly marketed to consumers. He had no other relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Kenneth D. Steinsapir, American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery, cosmetic botulinum toxin, onabotulinumtoxinA, maximal frontalis brow lifts, eyelid ptosis, ptotic, microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift, eyebrow depressors,

Dr. Kenneth D. Steinsapir, American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery, cosmetic botulinum toxin, onabotulinumtoxinA, maximal frontalis brow lifts, eyelid ptosis, ptotic, microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift, eyebrow depressors,

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF COSMETIC SURGERY

Major Finding: Patients who underwent the microdroplet botulinum toxin forehead lift experienced no cases of treatment-induced upper eyelid or eyebrow ptosis or cases of diplopia.

Data Source: A 5-year study of the technique performed on 574 consecutive patients with a mean age of 45 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Steinsapir received a United States patent on the microdroplet method. He said that he hopes to license the technique to a drug company for the development of an FDA-approved indication so the treatment can be directly marketed to consumers. He had no other relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Six steps to creating perfect lips

Lips, like hairstyles, have trends. Bee-stung lips were the thing of 1920s; big hair was the thing of 1980s. And now, while bangs may be the next big thing after the First Lady's new 'do, lips with well-defined philtrum columns are in.

Lips, like hairstyles, have trends. Bee-stung lips were the thing of 1920s; big hair was the thing of 1980s. And now, while bangs may be the next big thing after the First Lady's new 'do, lips with well-defined philtrum columns are in.

Lips, like hairstyles, have trends. Bee-stung lips were the thing of 1920s; big hair was the thing of 1980s. And now, while bangs may be the next big thing after the First Lady's new 'do, lips with well-defined philtrum columns are in.

Surgeon, respect the levator muscle

LAS VEGAS – Knowing and respecting the anatomy of the levator muscle can help clinicians steer clear of complications from blepharoplasty and manage ptosis, according to Dr. Marc S. Cohen.

"It’s very helpful if you have a good understanding of how to find the levator muscle during eyelid surgery," said Dr. Cohen, an ophthalmic plastic surgeon at the Wills Eye Institute, Philadelphia. "In order to do this, you need to understand the relationship between the levator and the other eyelid structures."

The levator muscle elevates the eyelid and helps form the eyelid crease. It also creates the margin contour. As the levator muscle approaches the eyelid, it changes direction from vertically oriented to horizontally oriented. The muscle then advances inferiorly toward the eyelid margin, "and for the final centimeter or so, it becomes a fibrous aponeurosis, which attaches to the tarsus posteriorly," said Dr. Cohen, who also has a private cosmetic surgery practice. Behind the levator muscle are Müller’s muscle and the conjunctiva.

Whether a surgeon performs blepharoplasty with a CO2 laser, a blade, cautery, or radiofrequency, the first structure encountered posteriorly is the orbicularis oculi muscle, which closes the eyelid. "It’s highly vascular, and is the site where most of the bleeding occurs during blepharoplasty," Dr. Cohen said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery.

The next layer contains the orbital septum. "It’s important to understand that the septum does not travel all the way to the eyelid margin," he added. "The septum starts at the orbital rim and attaches to the levator muscle. This layer really has two structures: the septum and the levator. Behind the septum are the eyelid fat pads."

In a dissection above and behind in the eyelid, the septum and the fat precede the levator muscle. However, in the inferior eyelid, the levator is just deep to the orbicularis muscle. Beneath the fat, the levator muscle moves posteriorly into the orbit; this causes it to narrow.

"Lateral to the muscle at this point is the lacrimal gland, but medially is just orbital fat," Dr. Cohen said. Upon reaching the orbicularis muscle, the goal is to protect the levator muscle. "The levator muscle is protected by septum fat superiorly, whereas more inferiorly the levator fuses with the orbicularis, so this is a danger zone," Dr. Cohen said. "Laterally is the lacrimal gland and supramedially is the safest point, because there you have the fat, and nothing else to really worry about superficially. So what you do is press on the globe through the eyelid, have the fat prolapse forward, and dissect there."

Reattaching the levator muscle can be tricky in the context of levator resection ptosis surgery, said Dr. Cohen. "Where you make the attachment is going to affect the contour postoperatively," he said. "Grasp the tarsus and pull it upward to see if you have obtained a natural curve. If you grasp it at the wrong point, you’ll have a curve that’s not aesthetically pleasing," he cautioned.

"When you get the right point, that is where you are going to put the sutures to reattach the levator. A double-armed 6-0 suture is passed in a horizontal mattress fashion, partial thickness, through the tarsus. The suture is then passed in a posterior to anterior direction, which shortens the levator muscle."

Placement of the suture determines how much the muscle shortens. "The suture is then temporarily tied, and the patient is asked to open their eyes to assess the height and the contour," Dr. Cohen said. "If you need to adjust height vertically, you can move the suture vertically on the levator muscle. If there’s a problem with the contour, you change the fixation point to the tarsus. Then the suture is permanently tied and the skin is closed."

Dr. Cohen warned about the risk of complications from blepharoplasty in patients with active Graves’ disease, a common autoimmune condition that can cause hyperthyroidism and fibrosis of the extraocular tissues. The severe form of Graves’ disease can cause eyelid retraction, difficulty closing the eyes, double vision, and anterior displacement of the globes. "Many patients present with much more subtle findings," he noted. "For example, fibrosis of the levator with lid retraction is a common presentation in women aged 40-60 – the same demographic that tends to have blepharoplasty. It’s often subtle and underdiagnosed."

Patients with undiagnosed Graves’ disease prior to a blepharoplasty "can develop signs and symptoms which are indistinguishable from the complications of blepharoplasty," Dr. Cohen said. "You need to make the diagnosis before surgery and make sure the disease has stabilized before you do any surgery. That happens on average in about 18 months but is variable."

Dr. Cohen disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Allergan and that he is a speaker for Allergan and Medicis.

LAS VEGAS – Knowing and respecting the anatomy of the levator muscle can help clinicians steer clear of complications from blepharoplasty and manage ptosis, according to Dr. Marc S. Cohen.

"It’s very helpful if you have a good understanding of how to find the levator muscle during eyelid surgery," said Dr. Cohen, an ophthalmic plastic surgeon at the Wills Eye Institute, Philadelphia. "In order to do this, you need to understand the relationship between the levator and the other eyelid structures."

The levator muscle elevates the eyelid and helps form the eyelid crease. It also creates the margin contour. As the levator muscle approaches the eyelid, it changes direction from vertically oriented to horizontally oriented. The muscle then advances inferiorly toward the eyelid margin, "and for the final centimeter or so, it becomes a fibrous aponeurosis, which attaches to the tarsus posteriorly," said Dr. Cohen, who also has a private cosmetic surgery practice. Behind the levator muscle are Müller’s muscle and the conjunctiva.

Whether a surgeon performs blepharoplasty with a CO2 laser, a blade, cautery, or radiofrequency, the first structure encountered posteriorly is the orbicularis oculi muscle, which closes the eyelid. "It’s highly vascular, and is the site where most of the bleeding occurs during blepharoplasty," Dr. Cohen said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery.

The next layer contains the orbital septum. "It’s important to understand that the septum does not travel all the way to the eyelid margin," he added. "The septum starts at the orbital rim and attaches to the levator muscle. This layer really has two structures: the septum and the levator. Behind the septum are the eyelid fat pads."

In a dissection above and behind in the eyelid, the septum and the fat precede the levator muscle. However, in the inferior eyelid, the levator is just deep to the orbicularis muscle. Beneath the fat, the levator muscle moves posteriorly into the orbit; this causes it to narrow.

"Lateral to the muscle at this point is the lacrimal gland, but medially is just orbital fat," Dr. Cohen said. Upon reaching the orbicularis muscle, the goal is to protect the levator muscle. "The levator muscle is protected by septum fat superiorly, whereas more inferiorly the levator fuses with the orbicularis, so this is a danger zone," Dr. Cohen said. "Laterally is the lacrimal gland and supramedially is the safest point, because there you have the fat, and nothing else to really worry about superficially. So what you do is press on the globe through the eyelid, have the fat prolapse forward, and dissect there."

Reattaching the levator muscle can be tricky in the context of levator resection ptosis surgery, said Dr. Cohen. "Where you make the attachment is going to affect the contour postoperatively," he said. "Grasp the tarsus and pull it upward to see if you have obtained a natural curve. If you grasp it at the wrong point, you’ll have a curve that’s not aesthetically pleasing," he cautioned.

"When you get the right point, that is where you are going to put the sutures to reattach the levator. A double-armed 6-0 suture is passed in a horizontal mattress fashion, partial thickness, through the tarsus. The suture is then passed in a posterior to anterior direction, which shortens the levator muscle."

Placement of the suture determines how much the muscle shortens. "The suture is then temporarily tied, and the patient is asked to open their eyes to assess the height and the contour," Dr. Cohen said. "If you need to adjust height vertically, you can move the suture vertically on the levator muscle. If there’s a problem with the contour, you change the fixation point to the tarsus. Then the suture is permanently tied and the skin is closed."

Dr. Cohen warned about the risk of complications from blepharoplasty in patients with active Graves’ disease, a common autoimmune condition that can cause hyperthyroidism and fibrosis of the extraocular tissues. The severe form of Graves’ disease can cause eyelid retraction, difficulty closing the eyes, double vision, and anterior displacement of the globes. "Many patients present with much more subtle findings," he noted. "For example, fibrosis of the levator with lid retraction is a common presentation in women aged 40-60 – the same demographic that tends to have blepharoplasty. It’s often subtle and underdiagnosed."

Patients with undiagnosed Graves’ disease prior to a blepharoplasty "can develop signs and symptoms which are indistinguishable from the complications of blepharoplasty," Dr. Cohen said. "You need to make the diagnosis before surgery and make sure the disease has stabilized before you do any surgery. That happens on average in about 18 months but is variable."

Dr. Cohen disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Allergan and that he is a speaker for Allergan and Medicis.

LAS VEGAS – Knowing and respecting the anatomy of the levator muscle can help clinicians steer clear of complications from blepharoplasty and manage ptosis, according to Dr. Marc S. Cohen.

"It’s very helpful if you have a good understanding of how to find the levator muscle during eyelid surgery," said Dr. Cohen, an ophthalmic plastic surgeon at the Wills Eye Institute, Philadelphia. "In order to do this, you need to understand the relationship between the levator and the other eyelid structures."

The levator muscle elevates the eyelid and helps form the eyelid crease. It also creates the margin contour. As the levator muscle approaches the eyelid, it changes direction from vertically oriented to horizontally oriented. The muscle then advances inferiorly toward the eyelid margin, "and for the final centimeter or so, it becomes a fibrous aponeurosis, which attaches to the tarsus posteriorly," said Dr. Cohen, who also has a private cosmetic surgery practice. Behind the levator muscle are Müller’s muscle and the conjunctiva.

Whether a surgeon performs blepharoplasty with a CO2 laser, a blade, cautery, or radiofrequency, the first structure encountered posteriorly is the orbicularis oculi muscle, which closes the eyelid. "It’s highly vascular, and is the site where most of the bleeding occurs during blepharoplasty," Dr. Cohen said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery.

The next layer contains the orbital septum. "It’s important to understand that the septum does not travel all the way to the eyelid margin," he added. "The septum starts at the orbital rim and attaches to the levator muscle. This layer really has two structures: the septum and the levator. Behind the septum are the eyelid fat pads."

In a dissection above and behind in the eyelid, the septum and the fat precede the levator muscle. However, in the inferior eyelid, the levator is just deep to the orbicularis muscle. Beneath the fat, the levator muscle moves posteriorly into the orbit; this causes it to narrow.

"Lateral to the muscle at this point is the lacrimal gland, but medially is just orbital fat," Dr. Cohen said. Upon reaching the orbicularis muscle, the goal is to protect the levator muscle. "The levator muscle is protected by septum fat superiorly, whereas more inferiorly the levator fuses with the orbicularis, so this is a danger zone," Dr. Cohen said. "Laterally is the lacrimal gland and supramedially is the safest point, because there you have the fat, and nothing else to really worry about superficially. So what you do is press on the globe through the eyelid, have the fat prolapse forward, and dissect there."

Reattaching the levator muscle can be tricky in the context of levator resection ptosis surgery, said Dr. Cohen. "Where you make the attachment is going to affect the contour postoperatively," he said. "Grasp the tarsus and pull it upward to see if you have obtained a natural curve. If you grasp it at the wrong point, you’ll have a curve that’s not aesthetically pleasing," he cautioned.

"When you get the right point, that is where you are going to put the sutures to reattach the levator. A double-armed 6-0 suture is passed in a horizontal mattress fashion, partial thickness, through the tarsus. The suture is then passed in a posterior to anterior direction, which shortens the levator muscle."

Placement of the suture determines how much the muscle shortens. "The suture is then temporarily tied, and the patient is asked to open their eyes to assess the height and the contour," Dr. Cohen said. "If you need to adjust height vertically, you can move the suture vertically on the levator muscle. If there’s a problem with the contour, you change the fixation point to the tarsus. Then the suture is permanently tied and the skin is closed."

Dr. Cohen warned about the risk of complications from blepharoplasty in patients with active Graves’ disease, a common autoimmune condition that can cause hyperthyroidism and fibrosis of the extraocular tissues. The severe form of Graves’ disease can cause eyelid retraction, difficulty closing the eyes, double vision, and anterior displacement of the globes. "Many patients present with much more subtle findings," he noted. "For example, fibrosis of the levator with lid retraction is a common presentation in women aged 40-60 – the same demographic that tends to have blepharoplasty. It’s often subtle and underdiagnosed."

Patients with undiagnosed Graves’ disease prior to a blepharoplasty "can develop signs and symptoms which are indistinguishable from the complications of blepharoplasty," Dr. Cohen said. "You need to make the diagnosis before surgery and make sure the disease has stabilized before you do any surgery. That happens on average in about 18 months but is variable."

Dr. Cohen disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Allergan and that he is a speaker for Allergan and Medicis.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF COSMETIC SURGERY

Use caution with lasers on darker skin

When using laser resurfacing for patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick types 4 to 6), use caution, said Dr. Andrew Alexis at the 10th annual meeting of the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Traditional approaches to laser resurfacing for acne scarring can lead to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring in patients with darker skin types, said Dr. Alexis. But two main steps can considerably reduce the risk of adverse effects: choosing the appropriate laser and taking pre- and post-treatment precautions.

In a video interview with Skin & Allergy News, Dr. Alexis shares his laser recommendations, tips on technique, and treatment suggestions for before and after the procedure.

Dr. Alexis is the director of the Skin of Color Center at St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center, and associate professor of clinical dermatology at Columbia University in New York.

When using laser resurfacing for patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick types 4 to 6), use caution, said Dr. Andrew Alexis at the 10th annual meeting of the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Traditional approaches to laser resurfacing for acne scarring can lead to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring in patients with darker skin types, said Dr. Alexis. But two main steps can considerably reduce the risk of adverse effects: choosing the appropriate laser and taking pre- and post-treatment precautions.

In a video interview with Skin & Allergy News, Dr. Alexis shares his laser recommendations, tips on technique, and treatment suggestions for before and after the procedure.

Dr. Alexis is the director of the Skin of Color Center at St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center, and associate professor of clinical dermatology at Columbia University in New York.

When using laser resurfacing for patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick types 4 to 6), use caution, said Dr. Andrew Alexis at the 10th annual meeting of the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Traditional approaches to laser resurfacing for acne scarring can lead to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring in patients with darker skin types, said Dr. Alexis. But two main steps can considerably reduce the risk of adverse effects: choosing the appropriate laser and taking pre- and post-treatment precautions.

In a video interview with Skin & Allergy News, Dr. Alexis shares his laser recommendations, tips on technique, and treatment suggestions for before and after the procedure.

Dr. Alexis is the director of the Skin of Color Center at St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center, and associate professor of clinical dermatology at Columbia University in New York.

Low-level laser effective for reducing upper arm circumference

ATLANTA – Low-level laser therapy produced a significant and durable reduction in upper arm circumference in a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study of 62 patients.

An overall reduction in upper arm circumference of at least 1.25 cm was achieved in 58% of 31 patients randomized to receive three, 20-minute treatments each week for 2 weeks, compared with 3% of 31 patients randomized to receive sham treatments, Dr. Mark S. Nestor reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The mean combined reductions in arm circumference were 2.0 cm after three treatments and 3.7 cm after six active treatments in the intervention group patients, compared with a gain of 0.1 cm and a reduction of 0.3 cm after 3 and 6 treatments, respectively, in the sham-treated control group, said Dr. Nestor, a dermatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla.

The differences between the intervention and control group were statistically significant, he said.

The results were unchanged at the 2-week follow up. In 14 intervention group patients available for follow-up at 5-10 months post treatment, the decrease in upper arm circumference persisted at 3.25 cm, which was "essentially unchanged from the 4-week result," he noted.

The low-level laser therapy device used for this study (Zerona) consists of five independent diodes emitting 17 mW of red 635-nm laser light in overlapping patterns. A total of 3.94 J/cm2 of energy was delivered during each treatment.

The device has been cleared as a noninvasive body contouring therapy for reducing hip, waist, and thigh circumference, but potential effects of confounding variables when it comes to measuring results have created confusion about the extent of the effects, Dr. Nestor said.

For example, abdominal measures from one day to the next can easily be affected by diet and other factors, he explained.

Upper arm circumference provides a more objective measure.

"I think that this model for body contouring is really wonderful, because [with the upper arm] you don’t see a lot of change from exercise or diet in the short term," he said.

Subjects in this study, who agreed to abstain from changes in diet or exercise during the study period, were treated at one of three participating centers. Arm circumference was measured at three equidistant points between the elbow and shoulder.

There were no reports of pain or discomfort, and no adverse events occurred.

Patient satisfaction was high, Dr. Nestor said. More subjects in the treatment group than in the control group reported satisfaction with the results (65% vs. 22%), improved appearance (81% vs. 26%), and results that exceeded expectations (45% vs. 17%).

Dr. Nestor reported that he has served as a consultant for and received research funding from Erchonia, maker of the Zerona laser therapy device used in this study.

ATLANTA – Low-level laser therapy produced a significant and durable reduction in upper arm circumference in a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study of 62 patients.

An overall reduction in upper arm circumference of at least 1.25 cm was achieved in 58% of 31 patients randomized to receive three, 20-minute treatments each week for 2 weeks, compared with 3% of 31 patients randomized to receive sham treatments, Dr. Mark S. Nestor reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The mean combined reductions in arm circumference were 2.0 cm after three treatments and 3.7 cm after six active treatments in the intervention group patients, compared with a gain of 0.1 cm and a reduction of 0.3 cm after 3 and 6 treatments, respectively, in the sham-treated control group, said Dr. Nestor, a dermatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla.

The differences between the intervention and control group were statistically significant, he said.

The results were unchanged at the 2-week follow up. In 14 intervention group patients available for follow-up at 5-10 months post treatment, the decrease in upper arm circumference persisted at 3.25 cm, which was "essentially unchanged from the 4-week result," he noted.

The low-level laser therapy device used for this study (Zerona) consists of five independent diodes emitting 17 mW of red 635-nm laser light in overlapping patterns. A total of 3.94 J/cm2 of energy was delivered during each treatment.

The device has been cleared as a noninvasive body contouring therapy for reducing hip, waist, and thigh circumference, but potential effects of confounding variables when it comes to measuring results have created confusion about the extent of the effects, Dr. Nestor said.

For example, abdominal measures from one day to the next can easily be affected by diet and other factors, he explained.

Upper arm circumference provides a more objective measure.

"I think that this model for body contouring is really wonderful, because [with the upper arm] you don’t see a lot of change from exercise or diet in the short term," he said.

Subjects in this study, who agreed to abstain from changes in diet or exercise during the study period, were treated at one of three participating centers. Arm circumference was measured at three equidistant points between the elbow and shoulder.

There were no reports of pain or discomfort, and no adverse events occurred.

Patient satisfaction was high, Dr. Nestor said. More subjects in the treatment group than in the control group reported satisfaction with the results (65% vs. 22%), improved appearance (81% vs. 26%), and results that exceeded expectations (45% vs. 17%).

Dr. Nestor reported that he has served as a consultant for and received research funding from Erchonia, maker of the Zerona laser therapy device used in this study.

ATLANTA – Low-level laser therapy produced a significant and durable reduction in upper arm circumference in a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study of 62 patients.

An overall reduction in upper arm circumference of at least 1.25 cm was achieved in 58% of 31 patients randomized to receive three, 20-minute treatments each week for 2 weeks, compared with 3% of 31 patients randomized to receive sham treatments, Dr. Mark S. Nestor reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The mean combined reductions in arm circumference were 2.0 cm after three treatments and 3.7 cm after six active treatments in the intervention group patients, compared with a gain of 0.1 cm and a reduction of 0.3 cm after 3 and 6 treatments, respectively, in the sham-treated control group, said Dr. Nestor, a dermatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla.

The differences between the intervention and control group were statistically significant, he said.

The results were unchanged at the 2-week follow up. In 14 intervention group patients available for follow-up at 5-10 months post treatment, the decrease in upper arm circumference persisted at 3.25 cm, which was "essentially unchanged from the 4-week result," he noted.

The low-level laser therapy device used for this study (Zerona) consists of five independent diodes emitting 17 mW of red 635-nm laser light in overlapping patterns. A total of 3.94 J/cm2 of energy was delivered during each treatment.

The device has been cleared as a noninvasive body contouring therapy for reducing hip, waist, and thigh circumference, but potential effects of confounding variables when it comes to measuring results have created confusion about the extent of the effects, Dr. Nestor said.

For example, abdominal measures from one day to the next can easily be affected by diet and other factors, he explained.

Upper arm circumference provides a more objective measure.

"I think that this model for body contouring is really wonderful, because [with the upper arm] you don’t see a lot of change from exercise or diet in the short term," he said.

Subjects in this study, who agreed to abstain from changes in diet or exercise during the study period, were treated at one of three participating centers. Arm circumference was measured at three equidistant points between the elbow and shoulder.

There were no reports of pain or discomfort, and no adverse events occurred.

Patient satisfaction was high, Dr. Nestor said. More subjects in the treatment group than in the control group reported satisfaction with the results (65% vs. 22%), improved appearance (81% vs. 26%), and results that exceeded expectations (45% vs. 17%).

Dr. Nestor reported that he has served as a consultant for and received research funding from Erchonia, maker of the Zerona laser therapy device used in this study.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Major Finding: The mean combined change in arm circumference was reduced by 2.0 cm after three active treatments and by 3.7 cm after six active treatments. After sham treatments at the same intervals, arm circumference increased 0.1 cm and decreased 0.3 cm, respectively.

Data Source: A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study.

Disclosures: Dr. Nestor reported that he has served as a consultant for and received research funding from Erchonia, maker of the low-level laser therapy device (Zerona) used in this study.

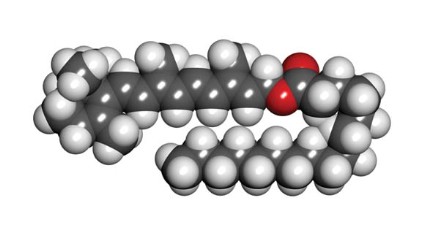

Retinyl palmitate

Retinyl palmitate, a storage and ester form of retinol (vitamin A) and the prevailing type of vitamin A found naturally in the skin (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75), has become increasingly popular during the past 2 decades. It is widely used in more than 600 skin care products, including cosmetics and sunscreens, and, with FDA approval, over-the-counter and prescription drugs (Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). It was also the subject of a controversial summer 2010 report by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) in which the organization warned of possible photocarcinogenicity associated with retinyl palmitate (RP)-containing sunscreens.

Although vitamin A storage in the epidermis takes the form of retinyl esters and retinols, they act differently when exposed to UV light. The retinols display UVB-resistant and UVB-sensitive characteristics not exhibited by retinyl esters such as RP (Dermatology 1999;199:302-7). The EWG used "vitamin A" and "retinyl palmitate" interchangeably in their criticisms and follow-ups, which is misleading. The vitamin A family of drugs includes retinyl esters, retinol, tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene, and oral isotretinoin (Accutane), in addition to four carotenoids, including beta-carotene, many of which have been shown to prevent or protect against cancer (Br. J. Cancer 1988;57:428-33; Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:949-56; J. Invest. Dermatol. 1981;76:178-80; Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1981;270:453-62). That does not mean that RP prevents cancer just because oral retinol, beta-carotene, or tretinoin have been shown to do so, for example. In fact, the study that the EWG refers to shows evidence that RP may lead to skin tumors in mice.

In response to the EWG report, Wang et al. acknowledged that of the eight in vitro studies published by the Food and Drug Administration from 2002 to 2009, four revealed that reactive oxygen species were produced by RP after UVA exposure (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67; Toxicol. Ind. Health 2007;23:625-31; Toxicol. Lett. 2006;163:30-43; Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90; Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18:129-38). However, they questioned the relevance of these results in the context of the convoluted mechanisms of the antioxidant setting in human skin. They also contended that the National Toxicology Program (NTP) study on which the EWG based its report failed to prove that the combination of RP and UV results in photocarcinogenesis and, in fact, was rife with reasons for skepticism (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). The EWG offered its own counterarguments and stood by its report. Rather than wade further into the debate that occurred in 2010 and found its way into the pages of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2010;63:903-6), let’s review what is known about RP.

What else do we know about RP?

In 1997, Duell et al. showed that unoccluded retinol is more effective at penetrating human skin in vivo than RP or retinoic acid (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1997;109:301-5).

In 2003, Antille et al. used an in vitro model to evaluate the photoprotective activity of RP, and then applied topical RP on the back of hairless mice before exposing them to UVB. They also applied topical RP or a sunscreen on the buttocks of human volunteers before exposing them to four minimal erythema doses of UVB. The investigators found that RP was as efficient in vitro as the commercial filter octylmethoxycinnamate in preventing UVB-induced fluorescence or photobleaching of fluorescent markers. Topical RP also significantly suppressed the formation of thymine dimers in mouse epidermis and human skin. In the volunteers, topical RP was as efficient as an SPF (sun protection factor) 20 sunscreen in preventing sunburn erythema (J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;121:1163-7).

In 2005, Yan et al. studied the phototoxicity of RP, anhydroretinol (AR), and 5,6-epoxyretinyl palmitate (5,6-epoxy-RP) in human skin Jurkat T cells with and without light irradiation. Irradiation of cells in the absence of a retinoid rendered little damage, but the presence of RP, 5,6-epoxy-RP, or AR (50, 100, 150, and 200 micromol/L) yielded DNA fragmentation, with cell death occurring at retinoid concentrations of 100 micromol/L or greater. The investigators concluded that DNA damage and cytotoxicity are engendered by RP and its photodecomposition products in association with UVA and visible light exposure. They also determined that UVA irradiation of these retinoids produces free radicals that spur DNA strand cleavage (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75).

RP accounts for most of the retinyl esters endogenously formed in skin. In 2006, Yan et al., noting that exogenous RP accumulates via topically applied cosmetic and skin care formulations, investigated the time course for buildup and disappearance of RP and retinol in the stratified layers of skin from female SKH-1 mice singly or repeatedly dosed with topical creams containing 0.5% or 2% RP. The researchers observed that within 24 hours of application, RP quickly diffused into the stratum corneum and epidermal skin layers. RP and retinol levels were lowest in the dermis, intermediate in the stratum corneum, and highest in the epidermis. In separated skin layers and intact skin, RP and retinol levels declined over time, but for 18 days, RP levels remained higher than control values. The investigators concluded that topically applied RP changed the normal physiological levels of RP and retinol in the skin of mice (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2006;22:181-91).

Having previously shown that irradiation of RP with UVA leads to the formation of photodecomposition products, synthesis of reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation induction, Xia et al. demonstrated comparable results, identifying RP as a photosensitizer following irradiation with UVB light (Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90).

Recommendations

In light of the controversy swirling around RP and the appropriate concern it has engendered, in addition to the weight of evidence as well as experience from personal observation, I advise patients to avoid daytime use of products with RP high on the ingredient list. I add that it poses real risks while offering minimal benefits. Such patients should be using retinol or tretinoin. I recommend the use of retinoids at night, to avoid the photosensitizing action induced by UVA or UVB on retinoids left on the skin.

Conclusion

Retinyl palmitate does not penetrate very well into the skin. Consequently, for over-the-counter topical formulations, I recommend retinol instead. Because of the slow penetration of RP into the skin, the RP that remains on the skin will undergo photoreaction more than a substance that is rapidly absorbed. When exposed to light, RP on the skin may undergo metabolism and/or photoreaction to generate reactive oxygen species. These reactive oxygen species or free radicals can theoretically lead to increased skin cancer. That said, sufficient evidence to establish a causal link between RP and skin cancer has not been produced. Nor, I’m afraid, are there any good reasons to recommend the use of RP. More research on this subject is needed and will likely emerge in a timely fashion.

Dr. Baumann is in private practice in Miami Beach. She did not disclose any conflicts of interest. To respond to this column, or to suggest topics for future columns, write to her at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com. This column, "Cosmeceutical Critique," appears regularly in Skin & Allergy News.

Retinyl palmitate, a storage and ester form of retinol (vitamin A) and the prevailing type of vitamin A found naturally in the skin (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75), has become increasingly popular during the past 2 decades. It is widely used in more than 600 skin care products, including cosmetics and sunscreens, and, with FDA approval, over-the-counter and prescription drugs (Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). It was also the subject of a controversial summer 2010 report by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) in which the organization warned of possible photocarcinogenicity associated with retinyl palmitate (RP)-containing sunscreens.

Although vitamin A storage in the epidermis takes the form of retinyl esters and retinols, they act differently when exposed to UV light. The retinols display UVB-resistant and UVB-sensitive characteristics not exhibited by retinyl esters such as RP (Dermatology 1999;199:302-7). The EWG used "vitamin A" and "retinyl palmitate" interchangeably in their criticisms and follow-ups, which is misleading. The vitamin A family of drugs includes retinyl esters, retinol, tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene, and oral isotretinoin (Accutane), in addition to four carotenoids, including beta-carotene, many of which have been shown to prevent or protect against cancer (Br. J. Cancer 1988;57:428-33; Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:949-56; J. Invest. Dermatol. 1981;76:178-80; Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1981;270:453-62). That does not mean that RP prevents cancer just because oral retinol, beta-carotene, or tretinoin have been shown to do so, for example. In fact, the study that the EWG refers to shows evidence that RP may lead to skin tumors in mice.

In response to the EWG report, Wang et al. acknowledged that of the eight in vitro studies published by the Food and Drug Administration from 2002 to 2009, four revealed that reactive oxygen species were produced by RP after UVA exposure (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67; Toxicol. Ind. Health 2007;23:625-31; Toxicol. Lett. 2006;163:30-43; Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90; Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18:129-38). However, they questioned the relevance of these results in the context of the convoluted mechanisms of the antioxidant setting in human skin. They also contended that the National Toxicology Program (NTP) study on which the EWG based its report failed to prove that the combination of RP and UV results in photocarcinogenesis and, in fact, was rife with reasons for skepticism (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). The EWG offered its own counterarguments and stood by its report. Rather than wade further into the debate that occurred in 2010 and found its way into the pages of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2010;63:903-6), let’s review what is known about RP.

What else do we know about RP?

In 1997, Duell et al. showed that unoccluded retinol is more effective at penetrating human skin in vivo than RP or retinoic acid (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1997;109:301-5).

In 2003, Antille et al. used an in vitro model to evaluate the photoprotective activity of RP, and then applied topical RP on the back of hairless mice before exposing them to UVB. They also applied topical RP or a sunscreen on the buttocks of human volunteers before exposing them to four minimal erythema doses of UVB. The investigators found that RP was as efficient in vitro as the commercial filter octylmethoxycinnamate in preventing UVB-induced fluorescence or photobleaching of fluorescent markers. Topical RP also significantly suppressed the formation of thymine dimers in mouse epidermis and human skin. In the volunteers, topical RP was as efficient as an SPF (sun protection factor) 20 sunscreen in preventing sunburn erythema (J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;121:1163-7).

In 2005, Yan et al. studied the phototoxicity of RP, anhydroretinol (AR), and 5,6-epoxyretinyl palmitate (5,6-epoxy-RP) in human skin Jurkat T cells with and without light irradiation. Irradiation of cells in the absence of a retinoid rendered little damage, but the presence of RP, 5,6-epoxy-RP, or AR (50, 100, 150, and 200 micromol/L) yielded DNA fragmentation, with cell death occurring at retinoid concentrations of 100 micromol/L or greater. The investigators concluded that DNA damage and cytotoxicity are engendered by RP and its photodecomposition products in association with UVA and visible light exposure. They also determined that UVA irradiation of these retinoids produces free radicals that spur DNA strand cleavage (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75).

RP accounts for most of the retinyl esters endogenously formed in skin. In 2006, Yan et al., noting that exogenous RP accumulates via topically applied cosmetic and skin care formulations, investigated the time course for buildup and disappearance of RP and retinol in the stratified layers of skin from female SKH-1 mice singly or repeatedly dosed with topical creams containing 0.5% or 2% RP. The researchers observed that within 24 hours of application, RP quickly diffused into the stratum corneum and epidermal skin layers. RP and retinol levels were lowest in the dermis, intermediate in the stratum corneum, and highest in the epidermis. In separated skin layers and intact skin, RP and retinol levels declined over time, but for 18 days, RP levels remained higher than control values. The investigators concluded that topically applied RP changed the normal physiological levels of RP and retinol in the skin of mice (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2006;22:181-91).

Having previously shown that irradiation of RP with UVA leads to the formation of photodecomposition products, synthesis of reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation induction, Xia et al. demonstrated comparable results, identifying RP as a photosensitizer following irradiation with UVB light (Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90).

Recommendations

In light of the controversy swirling around RP and the appropriate concern it has engendered, in addition to the weight of evidence as well as experience from personal observation, I advise patients to avoid daytime use of products with RP high on the ingredient list. I add that it poses real risks while offering minimal benefits. Such patients should be using retinol or tretinoin. I recommend the use of retinoids at night, to avoid the photosensitizing action induced by UVA or UVB on retinoids left on the skin.

Conclusion

Retinyl palmitate does not penetrate very well into the skin. Consequently, for over-the-counter topical formulations, I recommend retinol instead. Because of the slow penetration of RP into the skin, the RP that remains on the skin will undergo photoreaction more than a substance that is rapidly absorbed. When exposed to light, RP on the skin may undergo metabolism and/or photoreaction to generate reactive oxygen species. These reactive oxygen species or free radicals can theoretically lead to increased skin cancer. That said, sufficient evidence to establish a causal link between RP and skin cancer has not been produced. Nor, I’m afraid, are there any good reasons to recommend the use of RP. More research on this subject is needed and will likely emerge in a timely fashion.

Dr. Baumann is in private practice in Miami Beach. She did not disclose any conflicts of interest. To respond to this column, or to suggest topics for future columns, write to her at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com. This column, "Cosmeceutical Critique," appears regularly in Skin & Allergy News.

Retinyl palmitate, a storage and ester form of retinol (vitamin A) and the prevailing type of vitamin A found naturally in the skin (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75), has become increasingly popular during the past 2 decades. It is widely used in more than 600 skin care products, including cosmetics and sunscreens, and, with FDA approval, over-the-counter and prescription drugs (Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). It was also the subject of a controversial summer 2010 report by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) in which the organization warned of possible photocarcinogenicity associated with retinyl palmitate (RP)-containing sunscreens.

Although vitamin A storage in the epidermis takes the form of retinyl esters and retinols, they act differently when exposed to UV light. The retinols display UVB-resistant and UVB-sensitive characteristics not exhibited by retinyl esters such as RP (Dermatology 1999;199:302-7). The EWG used "vitamin A" and "retinyl palmitate" interchangeably in their criticisms and follow-ups, which is misleading. The vitamin A family of drugs includes retinyl esters, retinol, tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene, and oral isotretinoin (Accutane), in addition to four carotenoids, including beta-carotene, many of which have been shown to prevent or protect against cancer (Br. J. Cancer 1988;57:428-33; Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:949-56; J. Invest. Dermatol. 1981;76:178-80; Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1981;270:453-62). That does not mean that RP prevents cancer just because oral retinol, beta-carotene, or tretinoin have been shown to do so, for example. In fact, the study that the EWG refers to shows evidence that RP may lead to skin tumors in mice.

In response to the EWG report, Wang et al. acknowledged that of the eight in vitro studies published by the Food and Drug Administration from 2002 to 2009, four revealed that reactive oxygen species were produced by RP after UVA exposure (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67; Toxicol. Ind. Health 2007;23:625-31; Toxicol. Lett. 2006;163:30-43; Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90; Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18:129-38). However, they questioned the relevance of these results in the context of the convoluted mechanisms of the antioxidant setting in human skin. They also contended that the National Toxicology Program (NTP) study on which the EWG based its report failed to prove that the combination of RP and UV results in photocarcinogenesis and, in fact, was rife with reasons for skepticism (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). The EWG offered its own counterarguments and stood by its report. Rather than wade further into the debate that occurred in 2010 and found its way into the pages of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2010;63:903-6), let’s review what is known about RP.

What else do we know about RP?

In 1997, Duell et al. showed that unoccluded retinol is more effective at penetrating human skin in vivo than RP or retinoic acid (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1997;109:301-5).

In 2003, Antille et al. used an in vitro model to evaluate the photoprotective activity of RP, and then applied topical RP on the back of hairless mice before exposing them to UVB. They also applied topical RP or a sunscreen on the buttocks of human volunteers before exposing them to four minimal erythema doses of UVB. The investigators found that RP was as efficient in vitro as the commercial filter octylmethoxycinnamate in preventing UVB-induced fluorescence or photobleaching of fluorescent markers. Topical RP also significantly suppressed the formation of thymine dimers in mouse epidermis and human skin. In the volunteers, topical RP was as efficient as an SPF (sun protection factor) 20 sunscreen in preventing sunburn erythema (J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;121:1163-7).

In 2005, Yan et al. studied the phototoxicity of RP, anhydroretinol (AR), and 5,6-epoxyretinyl palmitate (5,6-epoxy-RP) in human skin Jurkat T cells with and without light irradiation. Irradiation of cells in the absence of a retinoid rendered little damage, but the presence of RP, 5,6-epoxy-RP, or AR (50, 100, 150, and 200 micromol/L) yielded DNA fragmentation, with cell death occurring at retinoid concentrations of 100 micromol/L or greater. The investigators concluded that DNA damage and cytotoxicity are engendered by RP and its photodecomposition products in association with UVA and visible light exposure. They also determined that UVA irradiation of these retinoids produces free radicals that spur DNA strand cleavage (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75).

RP accounts for most of the retinyl esters endogenously formed in skin. In 2006, Yan et al., noting that exogenous RP accumulates via topically applied cosmetic and skin care formulations, investigated the time course for buildup and disappearance of RP and retinol in the stratified layers of skin from female SKH-1 mice singly or repeatedly dosed with topical creams containing 0.5% or 2% RP. The researchers observed that within 24 hours of application, RP quickly diffused into the stratum corneum and epidermal skin layers. RP and retinol levels were lowest in the dermis, intermediate in the stratum corneum, and highest in the epidermis. In separated skin layers and intact skin, RP and retinol levels declined over time, but for 18 days, RP levels remained higher than control values. The investigators concluded that topically applied RP changed the normal physiological levels of RP and retinol in the skin of mice (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2006;22:181-91).

Having previously shown that irradiation of RP with UVA leads to the formation of photodecomposition products, synthesis of reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation induction, Xia et al. demonstrated comparable results, identifying RP as a photosensitizer following irradiation with UVB light (Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90).

Recommendations

In light of the controversy swirling around RP and the appropriate concern it has engendered, in addition to the weight of evidence as well as experience from personal observation, I advise patients to avoid daytime use of products with RP high on the ingredient list. I add that it poses real risks while offering minimal benefits. Such patients should be using retinol or tretinoin. I recommend the use of retinoids at night, to avoid the photosensitizing action induced by UVA or UVB on retinoids left on the skin.

Conclusion

Retinyl palmitate does not penetrate very well into the skin. Consequently, for over-the-counter topical formulations, I recommend retinol instead. Because of the slow penetration of RP into the skin, the RP that remains on the skin will undergo photoreaction more than a substance that is rapidly absorbed. When exposed to light, RP on the skin may undergo metabolism and/or photoreaction to generate reactive oxygen species. These reactive oxygen species or free radicals can theoretically lead to increased skin cancer. That said, sufficient evidence to establish a causal link between RP and skin cancer has not been produced. Nor, I’m afraid, are there any good reasons to recommend the use of RP. More research on this subject is needed and will likely emerge in a timely fashion.

Dr. Baumann is in private practice in Miami Beach. She did not disclose any conflicts of interest. To respond to this column, or to suggest topics for future columns, write to her at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com. This column, "Cosmeceutical Critique," appears regularly in Skin & Allergy News.

Cosmetic tattooing and ethnic skin

Cosmetic tattooing, also known as micropigmentation or permanent makeup, is a technique in which tattooing is performed to address cosmetic skin imperfections. It is often used to create eyeliner or lip liner, but it can also be used to camouflage stable patches of vitiligo, to create eyebrows on those who have lost them due to alopecia areata or chemotherapy, to create areolas for women who have had mastectomies, or to correct the shape of a reconstructed cleft lip. Cosmetic tattooing is also useful in women who want to wear makeup, but who have trouble applying it due to visual deficits, tremor, stroke, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease.

In Asian cultures, cosmetic tattooing is not uncommon. Many women have cosmetic tattooing procedures to create permanent eyeliner and eyebrows, since many Asian women have sparse brows at baseline that often become thinner with aging. Cosmetic tattooing of eyeliner also enhances the natural almond shape of the eyes.

In darker ethnic skin types, where vitiligo is more visible, stable patches can be effectively camouflaged by cosmetic tattooing. However, cosmetic tattooing is not recommended unless these patches have been stable for several years and the patient has failed other therapies. The best candidate would be the darker-skinned patient with long-standing segmental vitiligo, for whom pigment grafting would also be highly considered.

Individuals who wish to perform cosmetic tattooing can receive training and certification in micropigmentology. Many also undergo apprenticeships to receive more hands-on training. I have firsthand knowledge of this process because my mother received this training and performed cosmetic tattooing on her clients when I was growing up. Good training is key, as not every tattoo ink will have the same result in every skin tone. For example, brown eyeliner might eventually turn pink on skin that has a red undertone. On someone with yellow undertones or olive skin, black pigment liner might turn greenish. So the experienced practitioner will often use different color hues depending on the person’s underlying skin color and tone to prevent this discoloration. The best results of cosmetic tattooing are achieved when others can’t tell that the work has been done.

Pitfalls with cosmetic tattooing, as with tattooing in general, include infection, allergic reaction to the tattoo ink, scarring, photocytotoxicity, and cosmetic disfigurement if the tattoo is placed improperly. Delayed granulomatous response has also been reported in cases of permanent eyebrow tattooing. In addition to typical skin infections caused by staphylococcus or streptococcus, cases of mycobacterium infection with tattooing have been reported (although such infections have been reported more often with traditional tattooing than with permanent makeup).

Red ink is the more commonly reported allergen. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is widely used in tattoo inks to achieve certain colors. When TiO2 is exposed to certain wavelengths of light, including UV light and certain lasers, hydroxyl radicals can form, leading to photocytotoxicity (also called paradoxical darkening), which often results in a change or darkening of the pigment color. This condition is more common with pink, peach, or white tattoo colors where TiO2 is used in the color. Q-switched lasers are the most effective at removing tattoos.

If performed correctly by a properly trained person, cosmetic tattooing can be a useful aesthetic solution to various cosmetic and medical skin concerns.

This column, "Skin of Color," regularly appears in Dermatology News, a publication of Frontline Medical Communications. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif.

Do you have questions about treating patients with dark skin? If so, send them to sknews@elsevier.com.

Cosmetic tattooing, also known as micropigmentation or permanent makeup, is a technique in which tattooing is performed to address cosmetic skin imperfections. It is often used to create eyeliner or lip liner, but it can also be used to camouflage stable patches of vitiligo, to create eyebrows on those who have lost them due to alopecia areata or chemotherapy, to create areolas for women who have had mastectomies, or to correct the shape of a reconstructed cleft lip. Cosmetic tattooing is also useful in women who want to wear makeup, but who have trouble applying it due to visual deficits, tremor, stroke, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease.

In Asian cultures, cosmetic tattooing is not uncommon. Many women have cosmetic tattooing procedures to create permanent eyeliner and eyebrows, since many Asian women have sparse brows at baseline that often become thinner with aging. Cosmetic tattooing of eyeliner also enhances the natural almond shape of the eyes.

In darker ethnic skin types, where vitiligo is more visible, stable patches can be effectively camouflaged by cosmetic tattooing. However, cosmetic tattooing is not recommended unless these patches have been stable for several years and the patient has failed other therapies. The best candidate would be the darker-skinned patient with long-standing segmental vitiligo, for whom pigment grafting would also be highly considered.

Individuals who wish to perform cosmetic tattooing can receive training and certification in micropigmentology. Many also undergo apprenticeships to receive more hands-on training. I have firsthand knowledge of this process because my mother received this training and performed cosmetic tattooing on her clients when I was growing up. Good training is key, as not every tattoo ink will have the same result in every skin tone. For example, brown eyeliner might eventually turn pink on skin that has a red undertone. On someone with yellow undertones or olive skin, black pigment liner might turn greenish. So the experienced practitioner will often use different color hues depending on the person’s underlying skin color and tone to prevent this discoloration. The best results of cosmetic tattooing are achieved when others can’t tell that the work has been done.

Pitfalls with cosmetic tattooing, as with tattooing in general, include infection, allergic reaction to the tattoo ink, scarring, photocytotoxicity, and cosmetic disfigurement if the tattoo is placed improperly. Delayed granulomatous response has also been reported in cases of permanent eyebrow tattooing. In addition to typical skin infections caused by staphylococcus or streptococcus, cases of mycobacterium infection with tattooing have been reported (although such infections have been reported more often with traditional tattooing than with permanent makeup).