User login

Use of Intravenous Tranexamic Acid Improves Early Ambulation After Total Knee Arthroplasty and Anterior and Posterior Total Hip Arthroplasty

Take-Home Points

- IV-TXA significantly reduces intraoperative blood loss following TJA.

- Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of postoperative complications.

- IV-TXA minimizes postoperative anemia, facilitating improved early ambulation following TJA.

- IV-TXA significantly reduces the need for postoperative transfusions.

- IV-TXA is safe to use with no adverse events noted.

By the year 2020, use of primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the United States will increase an estimated 110%, to 1.375 million procedures annually, and use of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) will increase an estimated 75%, to more than 500,000 procedures.1 Minimizing perioperative blood loss and improving early postoperative ambulation both correlate with reduced postoperative morbidity, allowing patients to return to their daily lives expeditiously.

Tranexamic acid (TXA), a fibrinolytic inhibitor, competitively blocks lysine receptor binding sites of plasminogen, sustaining and stabilizing the fibrin architecture.2 TXA must be present to occupy binding sites before plasminogen binds to fibrin, validating the need for preoperative administration so the drug is available early in the fibrinolytic cascade.3 Intravenous (IV) TXA diffuses rapidly into joint fluid and the synovial membrane.4 Drug concentration and elimination half-life in joint fluid are equivalent to those in serum. Elimination of TXA occurs by glomerular filtration, with about 30% of a 10-mg/kg dose removed in 1 hour, 55% over the first 3 hours, and 90% within 24 hours of IV administration.5

The efficacy of IV-TXA in minimizing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) perioperative blood loss has been proved in small studies and meta-analyses.6-9 TXA-induced blood conservation decreases or eliminates the need for postoperative transfusion, which can impede valuable, early ambulation.10 In addition, the positive clinical safety profile of TXA supports routine use of TXA in TJA.6,11-15

The benefits of early ambulation after TJA are well established. Getting patients to walk on the day of surgery is a key part of effective and rapid postoperative rehabilitation. Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of venous thrombosis and postoperative complications.16 In contrast to bed rest, sitting and standing promotes oxygen saturation, which improves tissue healing and minimizes adverse pulmonary events. Oxygen saturation also preserves muscle strength and blood flow, reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism and ulcers. Muscle strength must be maintained so normal gait can be regained.17 Compared with rehabilitation initiated 48 to 72 hours after TKA, rehabilitation initiated within 24 hours reduced the number of sessions needed to achieve independence and normal gait; in addition, early mobilization improved patient reports of pain after surgery.18 An evaluation of Denmark registry data revealed that mobilization to walking and use of crutches or canes was achieved earlier when ambulation was initiated on day of surgery.19 Finally, mobilization on day of surgery and during the immediate postoperative period improved long-term quality of life after TJA.20

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if use of IV-TXA improves early ambulation and reduces blood loss after TKA and anterior and posterior THA. We hypothesized that IV-TXA use would reduce postoperative anemia and improve early ambulation and outcomes without producing adverse events during the immediate postoperative period. TXA reduces bleeding, and reduced incidence of hemarthrosis, wound swelling, and anemia could facilitate ambulation, reduce complications, and shorten recovery in patients who undergo TJA.

Patients and Methods

In February 2014, this retrospective cohort study received Institutional Review Board approval to compare the safety and efficacy of IV-TXA (vs no TXA) in patients who underwent TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA.

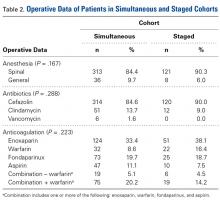

In March 2012, multidisciplinary protocols were standardized to ensure a uniform hospital course for patients at our institution. All patients underwent preoperative testing and evaluation by a nurse practitioner and an anesthesiologist. In March 2013, IV-TXA became our standard of care. TXA use was contraindicated in patients with thromboembolic disease or with hypersensitivity to TXA. Patients without a contraindication were given two 10-mg/kg IV-TXA doses, each administered over 15 to 30 minutes; the first dose was administered before incision, and the second was infused at case close and/or at least 60 minutes after the first dose. Most TKA patients received regional (femoral) anesthesia and analgesia, and most THA patients received spinal or epidural anesthesia and analgesia. In a small percentage of cases, IV analgesia was patient-controlled, as determined by the pain service. There were no significant differences in anesthesia/analgesia modality between the 2 study groups—patients who received TXA and those who did not. Patients were then transitioned to oral opioids for pain management, unless otherwise contraindicated, and were ambulated 4 hours after end of surgery, unless medically unstable. Hematology and chemistry laboratory values were monitored daily during admission.

Patients underwent physical therapy (PT) after surgery and until hospital discharge. Physical therapists blinded to patients’ intraoperative use or no use of TXA measured ambulation. After initial evaluation on postoperative day 0 (POD-0), patients were ambulated twice daily. The daily ambulation distance used for the study was the larger of the 2 daily PT distances (occasionally, patients were unable to participate fully in both sessions). Patients received either enoxaparin or rivaroxaban for postoperative thromboprophylaxis (the anticoagulant used was based on surgeon preference). Enoxaparin was subcutaneously administered at 30 mg every 12 hours for TKA, 40 mg once daily for THA, 30 mg once daily for calculated creatinine clearance under 30 mL/min, or 40 mg every 12 hours for body mass index (BMI) 40 or above. With enoxaparin, therapy duration was 14 days. Oral rivaroxaban was administered at 10 mg once daily for 12 days for TKA and 35 days for THA unless contraindicated.

The primary outcome variables were ambulation measured on POD-1 and POD-2 and intraoperative blood loss. In addition, hemoglobin and hematocrit were measured on POD-0, POD-1, and POD-2. Ambulation was defined as number of feet walked during postoperative hospitalization. To calculate intraoperative blood loss, the anesthesiologist subtracted any saline irrigation volume from the total volume in the suction canister. Also noted were postoperative transfusions and any diagnosis of postoperative venous thromboembolism—specifically, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the TXA and no-TXA groups were compared using either 2-sample t test (for continuous variables) or χ2 test (for categorical variables).

The ambulation outcome was log-transformed to meet standard assumptions of Gaussian residuals and equality of variance. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated on the log scale and were anti-logged so the results could be presented in their original units.

A linear mixed model was used to model intraoperative blood loss as a function of group (TXA, no TXA), procedure (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA), and potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time).

Linear mixed models for repeated measures were used to compare outcomes (hemoglobin, hematocrit) between groups (TXA, no TXA) and procedures (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA) and to compare changes in outcomes over time. Group, procedure, and operative time interactions were explored. Potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time) were included in the model as well.

A χ2 test was used to compare the groups (TXA, no TXA) on postoperative blood transfusion (yes, no). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used. Need for transfusion was clinically assessed case by case. Symptomatic anemia (dyspnea on exertion, headaches, tachycardia) was used as the primary indication for transfusion once hemoglobin fell below 8 g/dL or hematocrit below 24%. Number of patients with a postoperative thrombus formation was minimal. Therefore, this outcome was described with summary statistics and was not formally analyzed.

Results

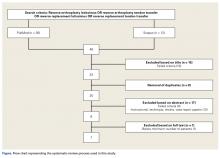

Of the 477 patients who underwent TJAs (275 TKAs, 98 anterior THAs, 104 posterior THAs; all unilateral), 111 did not receive TXA (June 2012-February 2013), and 366 received TXA (March 2013-January 2014). Other than for the addition of IV-TXA, the same standardized protocols instituted in March 2012 continued throughout the study period. The difference in sample size between the TXA and no-TXA groups was not statistically significant and did not influence the outcome measures.

Ambulation

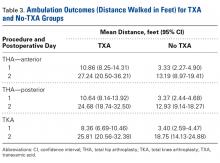

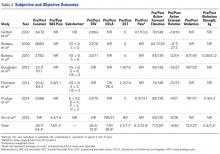

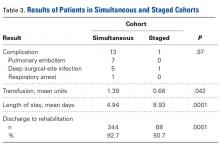

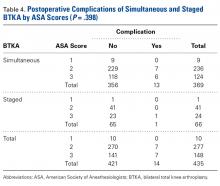

There was a significant (P = .0066) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P < .0001), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .8308). Regarding TKA, mean ambulation was higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-1 (8.36 vs 3.40 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (25.81 vs 18.75 feet; P = .0054). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (10.86 vs 3.33 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (27.24 vs 13.19 feet; P < .0001) and posterior THA at POD-1 (10.64 vs 3.37 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (24.68 vs 12.93 feet; P = .0002). See Table 3.

Intraoperative Blood Loss

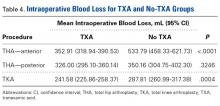

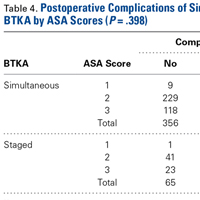

There was a significant 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure (P < .0053), and operative time (P < .0001) after adjusting for age (P < .6136), sex (P = .1147), and BMI (P = .6180). Regarding TKA, mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group (241.58 vs 287.81 mL; P = .0004). The same was true for anterior THA (352.91 vs 533.79 mL; P < .0001). Regarding posterior THA, there was no significant difference between the TXA and no-TXA groups (326.00 vs 350.16 mL; P = .3246). See Table 4.

Hemoglobin

There was a significant (P = .0008) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .0174), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P = .0007), and operative time (P = .0002). Regarding TKA, postoperative hemoglobin levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (12.10 vs 11.68 g/dL; P = .0135), POD-1 (11.62 vs 10.67 g/dL; P < .0001), and POD-2 (11.02 vs 10.11 g/dL; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (11.03 vs 10.19 g/dL; P = .0034) and POD-2 (10.57 vs 9.64 g/dL; P = .0009) and posterior THA at POD-2 (11.04 vs 10.16 g/dL; P = .0003). See Table 5.

Hematocrit

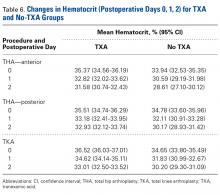

There was a significant (P < .0006) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .1597), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .0003). Regarding TKA, postoperative hematocrit levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (36.52% vs 34.65%; P < .0001), POD-1 (34.62% vs 31.83%; P < .0001), and POD-2 (33.01% vs 30.20%; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (32.82% vs 30.59%; P = .0037) and POD-2 (31.58% vs 28.61%; P = .0004) and posterior THA at POD-2 (32.93% vs 30.17%; P < .0001). See Table 6.

Postoperative Transfusions

Of the 477 patients, 25 (5.24%) required a postoperative transfusion. Postoperative transfusions were less likely (P < .0001) required in the TXA group (1.64%, 6/366) than in the no-TXA group (17.12%, 19/111). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used, and the different procedures were not evaluated separately.

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

Of the 477 patients, 2 developed a DVT, and 5 developed a PE. Both DVTs occurred in the TXA group (2/366, 0.55%; 95% CI, 0.07%-1.96%). Of the 5 PEs, 4 occurred in the TXA group (4/366, 1.09%; 95% CI, 0.30%-2.77%), and 1 occurred in the no-TXA group (1/111, 0.90%; 95% CI, 0.02%-4.92%). Given the exceedingly small number of events, no statistical significance was noted between groups.

Discussion

Orthopedic surgeons carefully balance patient expectations, societal needs, and regulatory mandates while providing excellent care and working under payers’ financial restrictions. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that, starting in 2016, TJAs will be reimbursed in total as a single bundled payment, adding to the need to provide optimal care in a fiscally responsible manner.21 Standardized protocols implementing multimodal therapies are pivotal in achieving favorable postoperative outcomes.

Our study results showed that IV-TXA use minimized hemoglobin and hematocrit reductions after TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. Postoperative anemia correlates with decreased ambulation ability and performance during the early postoperative period. In general, higher postoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit levels result in improved motor performance and shorter recovery.22 In addition, early ambulation is a validated predictor of favorable TJA outcomes. In our study, for TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA, ambulation on POD-1 and POD-2 was significantly better for patients who received TXA than for patients who did not.

Transfusion rates were markedly lower for our TXA group than for our no-TXA group (1.64% vs 17.12%), confirming the findings of numerous other studies on outcomes of TJA with TXA.2,3,6-12,14,15 Transfusions impede physical therapy and affect hospitalization costs.

Although potential thrombosis-related adverse events remain an endpoint in studies involving TXA, we found a comparably low incidence of postoperative venous thrombosis in our TXA and no-TXA groups (1.09% and 0.90%, respectively). In addition, no patient in either group developed a postoperative arterial thrombosis.

This is the largest single-center study of TXA use in TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. The effect of TXA use on postoperative ambulation was not previously found with TJA.

This study had its limitations. First, it was not prospective, randomized, or double-blinded. However, the physical therapists who mobilized patients and recorded ambulation data were blinded to the study and its hypothesis and followed a standardized protocol for all patients. In addition, intraoperative blood loss was recorded by an anesthesiologist using a standardized protocol, and patients received TXA per orthopedic protocol and surgeon preference, without selection bias. Another limitation was that ambulation data were captured only for POD-1 and POD-2 (most patients were discharged by POD-3). However, a goal of the study was to capture immediate postoperative data in order to determine the efficacy of intraoperative TXA. Subsequent studies can determine if this early benefit leads to long-term clinical outcome improvements.

In reducing blood loss and transfusion rates, intra-articular TXA is as efficacious as IV-TXA.23-25 We anticipate that the improved clinical outcomes found with IV-TXA in our study will be similar with intra-articular TXA, but more study is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusion

This retrospective cohort study found that use of IV-TXA in TJA improved early ambulation and clinical outcomes (reduced anemia, fewer transfusions) in the initial postoperative period, without producing adverse events.

1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

2. Jansen AJ, Andreica S, Claeys M, D’Haese J, Camu F, Jochmans K. Use of tranexamic acid for an effective blood conservation strategy after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(4):596-601.

3. Benoni G, Fredin H, Knebel R, Nilsson P. Blood conservation with tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(5):442-448.

4. Tanaka N, Sakahashi, H, Sato E, Hirose K, Ishima T, Ishii S. Timing of the administration of tranexamic acid for maximum reduction in blood loss in arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(5):702-705.

5. Nilsson IM. Clinical pharmacology of aminocaproic and tranexamic acids. J Clin Pathol Suppl (R Coll Pathol). 1980;14:41-47.

6. George DA, Sarraf KM, Nwaboku H. Single perioperative dose of tranexamic acid in primary hip and knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(1):129-133.

7. Vigna-Taglianti F, Basso L, Rolfo P, et al. Tranexamic acid for reducing blood transfusions in arthroplasty interventions: a cost-effective practice. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(4):545-551.

8. Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31(5):529-537.

9. Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349:g4829.

10. Sculco PK, Pagnano MW. Perioperative solutions for rapid recovery joint arthroplasty: get ahead and stay ahead. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(4):518-520.

11. Lozano M, Basora M, Peidro L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid administration during total knee arthroplasty. Vox Sang. 2008;95(1):39-44.

12. Rajesparan K, Biant LC, Ahmad M, Field RE. The effect of an intravenous bolus of tranexamic acid on blood loss in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(6):776-783.

13. Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(12):1577-1585.

14. Charoencholvanich K, Siriwattanasakul P. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2874-2880.

15. Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):39-46.

16. Stowers M, Lemanu DP, Coleman B, Hill AG, Munro JT. Review article: perioperative care in enhanced recovery for total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2014;22(3):383-392.

17. Larsen K, Hansen TB, Søballe K. Hip arthroplasty patients benefit from accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(5):624-630.

18. Labraca NS, Castro-Sánchez AM, Matarán-Peñarrocha GA, Arroyo-Morales M, Sánchez-Joya Mdel M, Moreno-Lorenzo C. Benefits of starting rehabilitation within 24 hours of primary total knee arthroplasty: randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(6):557-566.

19. Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, et al. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(2):263-268.

20. Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2012;83(346):1-39.

21. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. CMS.gov. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/cjr. Updated October 5, 2017.

22. Wang X, Rintala DH, Garber SL, Henson H. Association of hemoglobin levels, acute hemoglobin decrease, age, and co-morbidities with rehabilitation outcomes after total knee replacement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(6):451-456.

23. Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Pérez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo-Zalve R. Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):1937-1944.

24. Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, Westendorf DS, Garton AS, Lemke JH. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):889-894.

25. Alshryda S, Mason J, Sarda P, et al. Topical (intra-articular) tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates following total hip replacement: a randomized controlled trial (TRANX-H). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1969-1974.

Take-Home Points

- IV-TXA significantly reduces intraoperative blood loss following TJA.

- Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of postoperative complications.

- IV-TXA minimizes postoperative anemia, facilitating improved early ambulation following TJA.

- IV-TXA significantly reduces the need for postoperative transfusions.

- IV-TXA is safe to use with no adverse events noted.

By the year 2020, use of primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the United States will increase an estimated 110%, to 1.375 million procedures annually, and use of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) will increase an estimated 75%, to more than 500,000 procedures.1 Minimizing perioperative blood loss and improving early postoperative ambulation both correlate with reduced postoperative morbidity, allowing patients to return to their daily lives expeditiously.

Tranexamic acid (TXA), a fibrinolytic inhibitor, competitively blocks lysine receptor binding sites of plasminogen, sustaining and stabilizing the fibrin architecture.2 TXA must be present to occupy binding sites before plasminogen binds to fibrin, validating the need for preoperative administration so the drug is available early in the fibrinolytic cascade.3 Intravenous (IV) TXA diffuses rapidly into joint fluid and the synovial membrane.4 Drug concentration and elimination half-life in joint fluid are equivalent to those in serum. Elimination of TXA occurs by glomerular filtration, with about 30% of a 10-mg/kg dose removed in 1 hour, 55% over the first 3 hours, and 90% within 24 hours of IV administration.5

The efficacy of IV-TXA in minimizing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) perioperative blood loss has been proved in small studies and meta-analyses.6-9 TXA-induced blood conservation decreases or eliminates the need for postoperative transfusion, which can impede valuable, early ambulation.10 In addition, the positive clinical safety profile of TXA supports routine use of TXA in TJA.6,11-15

The benefits of early ambulation after TJA are well established. Getting patients to walk on the day of surgery is a key part of effective and rapid postoperative rehabilitation. Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of venous thrombosis and postoperative complications.16 In contrast to bed rest, sitting and standing promotes oxygen saturation, which improves tissue healing and minimizes adverse pulmonary events. Oxygen saturation also preserves muscle strength and blood flow, reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism and ulcers. Muscle strength must be maintained so normal gait can be regained.17 Compared with rehabilitation initiated 48 to 72 hours after TKA, rehabilitation initiated within 24 hours reduced the number of sessions needed to achieve independence and normal gait; in addition, early mobilization improved patient reports of pain after surgery.18 An evaluation of Denmark registry data revealed that mobilization to walking and use of crutches or canes was achieved earlier when ambulation was initiated on day of surgery.19 Finally, mobilization on day of surgery and during the immediate postoperative period improved long-term quality of life after TJA.20

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if use of IV-TXA improves early ambulation and reduces blood loss after TKA and anterior and posterior THA. We hypothesized that IV-TXA use would reduce postoperative anemia and improve early ambulation and outcomes without producing adverse events during the immediate postoperative period. TXA reduces bleeding, and reduced incidence of hemarthrosis, wound swelling, and anemia could facilitate ambulation, reduce complications, and shorten recovery in patients who undergo TJA.

Patients and Methods

In February 2014, this retrospective cohort study received Institutional Review Board approval to compare the safety and efficacy of IV-TXA (vs no TXA) in patients who underwent TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA.

In March 2012, multidisciplinary protocols were standardized to ensure a uniform hospital course for patients at our institution. All patients underwent preoperative testing and evaluation by a nurse practitioner and an anesthesiologist. In March 2013, IV-TXA became our standard of care. TXA use was contraindicated in patients with thromboembolic disease or with hypersensitivity to TXA. Patients without a contraindication were given two 10-mg/kg IV-TXA doses, each administered over 15 to 30 minutes; the first dose was administered before incision, and the second was infused at case close and/or at least 60 minutes after the first dose. Most TKA patients received regional (femoral) anesthesia and analgesia, and most THA patients received spinal or epidural anesthesia and analgesia. In a small percentage of cases, IV analgesia was patient-controlled, as determined by the pain service. There were no significant differences in anesthesia/analgesia modality between the 2 study groups—patients who received TXA and those who did not. Patients were then transitioned to oral opioids for pain management, unless otherwise contraindicated, and were ambulated 4 hours after end of surgery, unless medically unstable. Hematology and chemistry laboratory values were monitored daily during admission.

Patients underwent physical therapy (PT) after surgery and until hospital discharge. Physical therapists blinded to patients’ intraoperative use or no use of TXA measured ambulation. After initial evaluation on postoperative day 0 (POD-0), patients were ambulated twice daily. The daily ambulation distance used for the study was the larger of the 2 daily PT distances (occasionally, patients were unable to participate fully in both sessions). Patients received either enoxaparin or rivaroxaban for postoperative thromboprophylaxis (the anticoagulant used was based on surgeon preference). Enoxaparin was subcutaneously administered at 30 mg every 12 hours for TKA, 40 mg once daily for THA, 30 mg once daily for calculated creatinine clearance under 30 mL/min, or 40 mg every 12 hours for body mass index (BMI) 40 or above. With enoxaparin, therapy duration was 14 days. Oral rivaroxaban was administered at 10 mg once daily for 12 days for TKA and 35 days for THA unless contraindicated.

The primary outcome variables were ambulation measured on POD-1 and POD-2 and intraoperative blood loss. In addition, hemoglobin and hematocrit were measured on POD-0, POD-1, and POD-2. Ambulation was defined as number of feet walked during postoperative hospitalization. To calculate intraoperative blood loss, the anesthesiologist subtracted any saline irrigation volume from the total volume in the suction canister. Also noted were postoperative transfusions and any diagnosis of postoperative venous thromboembolism—specifically, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the TXA and no-TXA groups were compared using either 2-sample t test (for continuous variables) or χ2 test (for categorical variables).

The ambulation outcome was log-transformed to meet standard assumptions of Gaussian residuals and equality of variance. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated on the log scale and were anti-logged so the results could be presented in their original units.

A linear mixed model was used to model intraoperative blood loss as a function of group (TXA, no TXA), procedure (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA), and potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time).

Linear mixed models for repeated measures were used to compare outcomes (hemoglobin, hematocrit) between groups (TXA, no TXA) and procedures (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA) and to compare changes in outcomes over time. Group, procedure, and operative time interactions were explored. Potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time) were included in the model as well.

A χ2 test was used to compare the groups (TXA, no TXA) on postoperative blood transfusion (yes, no). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used. Need for transfusion was clinically assessed case by case. Symptomatic anemia (dyspnea on exertion, headaches, tachycardia) was used as the primary indication for transfusion once hemoglobin fell below 8 g/dL or hematocrit below 24%. Number of patients with a postoperative thrombus formation was minimal. Therefore, this outcome was described with summary statistics and was not formally analyzed.

Results

Of the 477 patients who underwent TJAs (275 TKAs, 98 anterior THAs, 104 posterior THAs; all unilateral), 111 did not receive TXA (June 2012-February 2013), and 366 received TXA (March 2013-January 2014). Other than for the addition of IV-TXA, the same standardized protocols instituted in March 2012 continued throughout the study period. The difference in sample size between the TXA and no-TXA groups was not statistically significant and did not influence the outcome measures.

Ambulation

There was a significant (P = .0066) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P < .0001), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .8308). Regarding TKA, mean ambulation was higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-1 (8.36 vs 3.40 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (25.81 vs 18.75 feet; P = .0054). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (10.86 vs 3.33 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (27.24 vs 13.19 feet; P < .0001) and posterior THA at POD-1 (10.64 vs 3.37 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (24.68 vs 12.93 feet; P = .0002). See Table 3.

Intraoperative Blood Loss

There was a significant 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure (P < .0053), and operative time (P < .0001) after adjusting for age (P < .6136), sex (P = .1147), and BMI (P = .6180). Regarding TKA, mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group (241.58 vs 287.81 mL; P = .0004). The same was true for anterior THA (352.91 vs 533.79 mL; P < .0001). Regarding posterior THA, there was no significant difference between the TXA and no-TXA groups (326.00 vs 350.16 mL; P = .3246). See Table 4.

Hemoglobin

There was a significant (P = .0008) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .0174), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P = .0007), and operative time (P = .0002). Regarding TKA, postoperative hemoglobin levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (12.10 vs 11.68 g/dL; P = .0135), POD-1 (11.62 vs 10.67 g/dL; P < .0001), and POD-2 (11.02 vs 10.11 g/dL; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (11.03 vs 10.19 g/dL; P = .0034) and POD-2 (10.57 vs 9.64 g/dL; P = .0009) and posterior THA at POD-2 (11.04 vs 10.16 g/dL; P = .0003). See Table 5.

Hematocrit

There was a significant (P < .0006) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .1597), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .0003). Regarding TKA, postoperative hematocrit levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (36.52% vs 34.65%; P < .0001), POD-1 (34.62% vs 31.83%; P < .0001), and POD-2 (33.01% vs 30.20%; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (32.82% vs 30.59%; P = .0037) and POD-2 (31.58% vs 28.61%; P = .0004) and posterior THA at POD-2 (32.93% vs 30.17%; P < .0001). See Table 6.

Postoperative Transfusions

Of the 477 patients, 25 (5.24%) required a postoperative transfusion. Postoperative transfusions were less likely (P < .0001) required in the TXA group (1.64%, 6/366) than in the no-TXA group (17.12%, 19/111). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used, and the different procedures were not evaluated separately.

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

Of the 477 patients, 2 developed a DVT, and 5 developed a PE. Both DVTs occurred in the TXA group (2/366, 0.55%; 95% CI, 0.07%-1.96%). Of the 5 PEs, 4 occurred in the TXA group (4/366, 1.09%; 95% CI, 0.30%-2.77%), and 1 occurred in the no-TXA group (1/111, 0.90%; 95% CI, 0.02%-4.92%). Given the exceedingly small number of events, no statistical significance was noted between groups.

Discussion

Orthopedic surgeons carefully balance patient expectations, societal needs, and regulatory mandates while providing excellent care and working under payers’ financial restrictions. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that, starting in 2016, TJAs will be reimbursed in total as a single bundled payment, adding to the need to provide optimal care in a fiscally responsible manner.21 Standardized protocols implementing multimodal therapies are pivotal in achieving favorable postoperative outcomes.

Our study results showed that IV-TXA use minimized hemoglobin and hematocrit reductions after TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. Postoperative anemia correlates with decreased ambulation ability and performance during the early postoperative period. In general, higher postoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit levels result in improved motor performance and shorter recovery.22 In addition, early ambulation is a validated predictor of favorable TJA outcomes. In our study, for TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA, ambulation on POD-1 and POD-2 was significantly better for patients who received TXA than for patients who did not.

Transfusion rates were markedly lower for our TXA group than for our no-TXA group (1.64% vs 17.12%), confirming the findings of numerous other studies on outcomes of TJA with TXA.2,3,6-12,14,15 Transfusions impede physical therapy and affect hospitalization costs.

Although potential thrombosis-related adverse events remain an endpoint in studies involving TXA, we found a comparably low incidence of postoperative venous thrombosis in our TXA and no-TXA groups (1.09% and 0.90%, respectively). In addition, no patient in either group developed a postoperative arterial thrombosis.

This is the largest single-center study of TXA use in TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. The effect of TXA use on postoperative ambulation was not previously found with TJA.

This study had its limitations. First, it was not prospective, randomized, or double-blinded. However, the physical therapists who mobilized patients and recorded ambulation data were blinded to the study and its hypothesis and followed a standardized protocol for all patients. In addition, intraoperative blood loss was recorded by an anesthesiologist using a standardized protocol, and patients received TXA per orthopedic protocol and surgeon preference, without selection bias. Another limitation was that ambulation data were captured only for POD-1 and POD-2 (most patients were discharged by POD-3). However, a goal of the study was to capture immediate postoperative data in order to determine the efficacy of intraoperative TXA. Subsequent studies can determine if this early benefit leads to long-term clinical outcome improvements.

In reducing blood loss and transfusion rates, intra-articular TXA is as efficacious as IV-TXA.23-25 We anticipate that the improved clinical outcomes found with IV-TXA in our study will be similar with intra-articular TXA, but more study is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusion

This retrospective cohort study found that use of IV-TXA in TJA improved early ambulation and clinical outcomes (reduced anemia, fewer transfusions) in the initial postoperative period, without producing adverse events.

Take-Home Points

- IV-TXA significantly reduces intraoperative blood loss following TJA.

- Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of postoperative complications.

- IV-TXA minimizes postoperative anemia, facilitating improved early ambulation following TJA.

- IV-TXA significantly reduces the need for postoperative transfusions.

- IV-TXA is safe to use with no adverse events noted.

By the year 2020, use of primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the United States will increase an estimated 110%, to 1.375 million procedures annually, and use of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) will increase an estimated 75%, to more than 500,000 procedures.1 Minimizing perioperative blood loss and improving early postoperative ambulation both correlate with reduced postoperative morbidity, allowing patients to return to their daily lives expeditiously.

Tranexamic acid (TXA), a fibrinolytic inhibitor, competitively blocks lysine receptor binding sites of plasminogen, sustaining and stabilizing the fibrin architecture.2 TXA must be present to occupy binding sites before plasminogen binds to fibrin, validating the need for preoperative administration so the drug is available early in the fibrinolytic cascade.3 Intravenous (IV) TXA diffuses rapidly into joint fluid and the synovial membrane.4 Drug concentration and elimination half-life in joint fluid are equivalent to those in serum. Elimination of TXA occurs by glomerular filtration, with about 30% of a 10-mg/kg dose removed in 1 hour, 55% over the first 3 hours, and 90% within 24 hours of IV administration.5

The efficacy of IV-TXA in minimizing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) perioperative blood loss has been proved in small studies and meta-analyses.6-9 TXA-induced blood conservation decreases or eliminates the need for postoperative transfusion, which can impede valuable, early ambulation.10 In addition, the positive clinical safety profile of TXA supports routine use of TXA in TJA.6,11-15

The benefits of early ambulation after TJA are well established. Getting patients to walk on the day of surgery is a key part of effective and rapid postoperative rehabilitation. Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of venous thrombosis and postoperative complications.16 In contrast to bed rest, sitting and standing promotes oxygen saturation, which improves tissue healing and minimizes adverse pulmonary events. Oxygen saturation also preserves muscle strength and blood flow, reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism and ulcers. Muscle strength must be maintained so normal gait can be regained.17 Compared with rehabilitation initiated 48 to 72 hours after TKA, rehabilitation initiated within 24 hours reduced the number of sessions needed to achieve independence and normal gait; in addition, early mobilization improved patient reports of pain after surgery.18 An evaluation of Denmark registry data revealed that mobilization to walking and use of crutches or canes was achieved earlier when ambulation was initiated on day of surgery.19 Finally, mobilization on day of surgery and during the immediate postoperative period improved long-term quality of life after TJA.20

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if use of IV-TXA improves early ambulation and reduces blood loss after TKA and anterior and posterior THA. We hypothesized that IV-TXA use would reduce postoperative anemia and improve early ambulation and outcomes without producing adverse events during the immediate postoperative period. TXA reduces bleeding, and reduced incidence of hemarthrosis, wound swelling, and anemia could facilitate ambulation, reduce complications, and shorten recovery in patients who undergo TJA.

Patients and Methods

In February 2014, this retrospective cohort study received Institutional Review Board approval to compare the safety and efficacy of IV-TXA (vs no TXA) in patients who underwent TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA.

In March 2012, multidisciplinary protocols were standardized to ensure a uniform hospital course for patients at our institution. All patients underwent preoperative testing and evaluation by a nurse practitioner and an anesthesiologist. In March 2013, IV-TXA became our standard of care. TXA use was contraindicated in patients with thromboembolic disease or with hypersensitivity to TXA. Patients without a contraindication were given two 10-mg/kg IV-TXA doses, each administered over 15 to 30 minutes; the first dose was administered before incision, and the second was infused at case close and/or at least 60 minutes after the first dose. Most TKA patients received regional (femoral) anesthesia and analgesia, and most THA patients received spinal or epidural anesthesia and analgesia. In a small percentage of cases, IV analgesia was patient-controlled, as determined by the pain service. There were no significant differences in anesthesia/analgesia modality between the 2 study groups—patients who received TXA and those who did not. Patients were then transitioned to oral opioids for pain management, unless otherwise contraindicated, and were ambulated 4 hours after end of surgery, unless medically unstable. Hematology and chemistry laboratory values were monitored daily during admission.

Patients underwent physical therapy (PT) after surgery and until hospital discharge. Physical therapists blinded to patients’ intraoperative use or no use of TXA measured ambulation. After initial evaluation on postoperative day 0 (POD-0), patients were ambulated twice daily. The daily ambulation distance used for the study was the larger of the 2 daily PT distances (occasionally, patients were unable to participate fully in both sessions). Patients received either enoxaparin or rivaroxaban for postoperative thromboprophylaxis (the anticoagulant used was based on surgeon preference). Enoxaparin was subcutaneously administered at 30 mg every 12 hours for TKA, 40 mg once daily for THA, 30 mg once daily for calculated creatinine clearance under 30 mL/min, or 40 mg every 12 hours for body mass index (BMI) 40 or above. With enoxaparin, therapy duration was 14 days. Oral rivaroxaban was administered at 10 mg once daily for 12 days for TKA and 35 days for THA unless contraindicated.

The primary outcome variables were ambulation measured on POD-1 and POD-2 and intraoperative blood loss. In addition, hemoglobin and hematocrit were measured on POD-0, POD-1, and POD-2. Ambulation was defined as number of feet walked during postoperative hospitalization. To calculate intraoperative blood loss, the anesthesiologist subtracted any saline irrigation volume from the total volume in the suction canister. Also noted were postoperative transfusions and any diagnosis of postoperative venous thromboembolism—specifically, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the TXA and no-TXA groups were compared using either 2-sample t test (for continuous variables) or χ2 test (for categorical variables).

The ambulation outcome was log-transformed to meet standard assumptions of Gaussian residuals and equality of variance. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated on the log scale and were anti-logged so the results could be presented in their original units.

A linear mixed model was used to model intraoperative blood loss as a function of group (TXA, no TXA), procedure (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA), and potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time).

Linear mixed models for repeated measures were used to compare outcomes (hemoglobin, hematocrit) between groups (TXA, no TXA) and procedures (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA) and to compare changes in outcomes over time. Group, procedure, and operative time interactions were explored. Potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time) were included in the model as well.

A χ2 test was used to compare the groups (TXA, no TXA) on postoperative blood transfusion (yes, no). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used. Need for transfusion was clinically assessed case by case. Symptomatic anemia (dyspnea on exertion, headaches, tachycardia) was used as the primary indication for transfusion once hemoglobin fell below 8 g/dL or hematocrit below 24%. Number of patients with a postoperative thrombus formation was minimal. Therefore, this outcome was described with summary statistics and was not formally analyzed.

Results

Of the 477 patients who underwent TJAs (275 TKAs, 98 anterior THAs, 104 posterior THAs; all unilateral), 111 did not receive TXA (June 2012-February 2013), and 366 received TXA (March 2013-January 2014). Other than for the addition of IV-TXA, the same standardized protocols instituted in March 2012 continued throughout the study period. The difference in sample size between the TXA and no-TXA groups was not statistically significant and did not influence the outcome measures.

Ambulation

There was a significant (P = .0066) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P < .0001), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .8308). Regarding TKA, mean ambulation was higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-1 (8.36 vs 3.40 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (25.81 vs 18.75 feet; P = .0054). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (10.86 vs 3.33 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (27.24 vs 13.19 feet; P < .0001) and posterior THA at POD-1 (10.64 vs 3.37 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (24.68 vs 12.93 feet; P = .0002). See Table 3.

Intraoperative Blood Loss

There was a significant 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure (P < .0053), and operative time (P < .0001) after adjusting for age (P < .6136), sex (P = .1147), and BMI (P = .6180). Regarding TKA, mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group (241.58 vs 287.81 mL; P = .0004). The same was true for anterior THA (352.91 vs 533.79 mL; P < .0001). Regarding posterior THA, there was no significant difference between the TXA and no-TXA groups (326.00 vs 350.16 mL; P = .3246). See Table 4.

Hemoglobin

There was a significant (P = .0008) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .0174), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P = .0007), and operative time (P = .0002). Regarding TKA, postoperative hemoglobin levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (12.10 vs 11.68 g/dL; P = .0135), POD-1 (11.62 vs 10.67 g/dL; P < .0001), and POD-2 (11.02 vs 10.11 g/dL; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (11.03 vs 10.19 g/dL; P = .0034) and POD-2 (10.57 vs 9.64 g/dL; P = .0009) and posterior THA at POD-2 (11.04 vs 10.16 g/dL; P = .0003). See Table 5.

Hematocrit

There was a significant (P < .0006) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .1597), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .0003). Regarding TKA, postoperative hematocrit levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (36.52% vs 34.65%; P < .0001), POD-1 (34.62% vs 31.83%; P < .0001), and POD-2 (33.01% vs 30.20%; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (32.82% vs 30.59%; P = .0037) and POD-2 (31.58% vs 28.61%; P = .0004) and posterior THA at POD-2 (32.93% vs 30.17%; P < .0001). See Table 6.

Postoperative Transfusions

Of the 477 patients, 25 (5.24%) required a postoperative transfusion. Postoperative transfusions were less likely (P < .0001) required in the TXA group (1.64%, 6/366) than in the no-TXA group (17.12%, 19/111). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used, and the different procedures were not evaluated separately.

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

Of the 477 patients, 2 developed a DVT, and 5 developed a PE. Both DVTs occurred in the TXA group (2/366, 0.55%; 95% CI, 0.07%-1.96%). Of the 5 PEs, 4 occurred in the TXA group (4/366, 1.09%; 95% CI, 0.30%-2.77%), and 1 occurred in the no-TXA group (1/111, 0.90%; 95% CI, 0.02%-4.92%). Given the exceedingly small number of events, no statistical significance was noted between groups.

Discussion

Orthopedic surgeons carefully balance patient expectations, societal needs, and regulatory mandates while providing excellent care and working under payers’ financial restrictions. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that, starting in 2016, TJAs will be reimbursed in total as a single bundled payment, adding to the need to provide optimal care in a fiscally responsible manner.21 Standardized protocols implementing multimodal therapies are pivotal in achieving favorable postoperative outcomes.

Our study results showed that IV-TXA use minimized hemoglobin and hematocrit reductions after TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. Postoperative anemia correlates with decreased ambulation ability and performance during the early postoperative period. In general, higher postoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit levels result in improved motor performance and shorter recovery.22 In addition, early ambulation is a validated predictor of favorable TJA outcomes. In our study, for TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA, ambulation on POD-1 and POD-2 was significantly better for patients who received TXA than for patients who did not.

Transfusion rates were markedly lower for our TXA group than for our no-TXA group (1.64% vs 17.12%), confirming the findings of numerous other studies on outcomes of TJA with TXA.2,3,6-12,14,15 Transfusions impede physical therapy and affect hospitalization costs.

Although potential thrombosis-related adverse events remain an endpoint in studies involving TXA, we found a comparably low incidence of postoperative venous thrombosis in our TXA and no-TXA groups (1.09% and 0.90%, respectively). In addition, no patient in either group developed a postoperative arterial thrombosis.

This is the largest single-center study of TXA use in TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. The effect of TXA use on postoperative ambulation was not previously found with TJA.

This study had its limitations. First, it was not prospective, randomized, or double-blinded. However, the physical therapists who mobilized patients and recorded ambulation data were blinded to the study and its hypothesis and followed a standardized protocol for all patients. In addition, intraoperative blood loss was recorded by an anesthesiologist using a standardized protocol, and patients received TXA per orthopedic protocol and surgeon preference, without selection bias. Another limitation was that ambulation data were captured only for POD-1 and POD-2 (most patients were discharged by POD-3). However, a goal of the study was to capture immediate postoperative data in order to determine the efficacy of intraoperative TXA. Subsequent studies can determine if this early benefit leads to long-term clinical outcome improvements.

In reducing blood loss and transfusion rates, intra-articular TXA is as efficacious as IV-TXA.23-25 We anticipate that the improved clinical outcomes found with IV-TXA in our study will be similar with intra-articular TXA, but more study is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusion

This retrospective cohort study found that use of IV-TXA in TJA improved early ambulation and clinical outcomes (reduced anemia, fewer transfusions) in the initial postoperative period, without producing adverse events.

1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

2. Jansen AJ, Andreica S, Claeys M, D’Haese J, Camu F, Jochmans K. Use of tranexamic acid for an effective blood conservation strategy after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(4):596-601.

3. Benoni G, Fredin H, Knebel R, Nilsson P. Blood conservation with tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(5):442-448.

4. Tanaka N, Sakahashi, H, Sato E, Hirose K, Ishima T, Ishii S. Timing of the administration of tranexamic acid for maximum reduction in blood loss in arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(5):702-705.

5. Nilsson IM. Clinical pharmacology of aminocaproic and tranexamic acids. J Clin Pathol Suppl (R Coll Pathol). 1980;14:41-47.

6. George DA, Sarraf KM, Nwaboku H. Single perioperative dose of tranexamic acid in primary hip and knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(1):129-133.

7. Vigna-Taglianti F, Basso L, Rolfo P, et al. Tranexamic acid for reducing blood transfusions in arthroplasty interventions: a cost-effective practice. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(4):545-551.

8. Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31(5):529-537.

9. Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349:g4829.

10. Sculco PK, Pagnano MW. Perioperative solutions for rapid recovery joint arthroplasty: get ahead and stay ahead. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(4):518-520.

11. Lozano M, Basora M, Peidro L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid administration during total knee arthroplasty. Vox Sang. 2008;95(1):39-44.

12. Rajesparan K, Biant LC, Ahmad M, Field RE. The effect of an intravenous bolus of tranexamic acid on blood loss in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(6):776-783.

13. Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(12):1577-1585.

14. Charoencholvanich K, Siriwattanasakul P. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2874-2880.

15. Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):39-46.

16. Stowers M, Lemanu DP, Coleman B, Hill AG, Munro JT. Review article: perioperative care in enhanced recovery for total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2014;22(3):383-392.

17. Larsen K, Hansen TB, Søballe K. Hip arthroplasty patients benefit from accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(5):624-630.

18. Labraca NS, Castro-Sánchez AM, Matarán-Peñarrocha GA, Arroyo-Morales M, Sánchez-Joya Mdel M, Moreno-Lorenzo C. Benefits of starting rehabilitation within 24 hours of primary total knee arthroplasty: randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(6):557-566.

19. Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, et al. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(2):263-268.

20. Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2012;83(346):1-39.

21. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. CMS.gov. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/cjr. Updated October 5, 2017.

22. Wang X, Rintala DH, Garber SL, Henson H. Association of hemoglobin levels, acute hemoglobin decrease, age, and co-morbidities with rehabilitation outcomes after total knee replacement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(6):451-456.

23. Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Pérez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo-Zalve R. Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):1937-1944.

24. Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, Westendorf DS, Garton AS, Lemke JH. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):889-894.

25. Alshryda S, Mason J, Sarda P, et al. Topical (intra-articular) tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates following total hip replacement: a randomized controlled trial (TRANX-H). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1969-1974.

1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

2. Jansen AJ, Andreica S, Claeys M, D’Haese J, Camu F, Jochmans K. Use of tranexamic acid for an effective blood conservation strategy after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(4):596-601.

3. Benoni G, Fredin H, Knebel R, Nilsson P. Blood conservation with tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(5):442-448.

4. Tanaka N, Sakahashi, H, Sato E, Hirose K, Ishima T, Ishii S. Timing of the administration of tranexamic acid for maximum reduction in blood loss in arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(5):702-705.

5. Nilsson IM. Clinical pharmacology of aminocaproic and tranexamic acids. J Clin Pathol Suppl (R Coll Pathol). 1980;14:41-47.

6. George DA, Sarraf KM, Nwaboku H. Single perioperative dose of tranexamic acid in primary hip and knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(1):129-133.

7. Vigna-Taglianti F, Basso L, Rolfo P, et al. Tranexamic acid for reducing blood transfusions in arthroplasty interventions: a cost-effective practice. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(4):545-551.

8. Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31(5):529-537.

9. Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349:g4829.

10. Sculco PK, Pagnano MW. Perioperative solutions for rapid recovery joint arthroplasty: get ahead and stay ahead. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(4):518-520.

11. Lozano M, Basora M, Peidro L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid administration during total knee arthroplasty. Vox Sang. 2008;95(1):39-44.

12. Rajesparan K, Biant LC, Ahmad M, Field RE. The effect of an intravenous bolus of tranexamic acid on blood loss in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(6):776-783.

13. Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(12):1577-1585.

14. Charoencholvanich K, Siriwattanasakul P. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2874-2880.

15. Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):39-46.

16. Stowers M, Lemanu DP, Coleman B, Hill AG, Munro JT. Review article: perioperative care in enhanced recovery for total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2014;22(3):383-392.

17. Larsen K, Hansen TB, Søballe K. Hip arthroplasty patients benefit from accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(5):624-630.

18. Labraca NS, Castro-Sánchez AM, Matarán-Peñarrocha GA, Arroyo-Morales M, Sánchez-Joya Mdel M, Moreno-Lorenzo C. Benefits of starting rehabilitation within 24 hours of primary total knee arthroplasty: randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(6):557-566.

19. Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, et al. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(2):263-268.

20. Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2012;83(346):1-39.

21. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. CMS.gov. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/cjr. Updated October 5, 2017.

22. Wang X, Rintala DH, Garber SL, Henson H. Association of hemoglobin levels, acute hemoglobin decrease, age, and co-morbidities with rehabilitation outcomes after total knee replacement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(6):451-456.

23. Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Pérez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo-Zalve R. Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):1937-1944.

24. Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, Westendorf DS, Garton AS, Lemke JH. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):889-894.

25. Alshryda S, Mason J, Sarda P, et al. Topical (intra-articular) tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates following total hip replacement: a randomized controlled trial (TRANX-H). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1969-1974.

The Role of Synovial Cytokines in the Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infections: Current Concepts

Take-Home Points

- In cases of failed TJA, it is important to differentiate between septic and aseptic etiologies.

- Chronic and low-grade infections are challenging for orthopedic surgeons, as the symptoms often overlap with aseptic etiologies.

- Verification of infection eradication before beginning the second-stage reimplantation surgery is extremely important, but pre- and intraoperative findings can be unreliable.

- Synovial fluid cytokines have been shown to accurately diagnose PJIs.

- Synovial fluid cytokines may help surgeons differentiate between septic and aseptic cases of failed TJA.

Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) is an effective procedure that has been extensively used to relieve pain and improve quality of life in patients with various forms of joint disease. Although advances in technology and surgical technique have improved the success of TJA, periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) remains a serious complication. In the United States, it is estimated that PJI is the most common reason for total knee arthroplasty failure and the third most common reason for total hip arthroplasty revision.1 Although the incidence of PJI is 1% to 2%, the dramatic increase in TJA volume is expected to be accompanied by a similar rise in the number of infected TJAs; that number is expected to exceed 60,000 in the United States by 2020.2 Moreover, management of PJI is expensive and imposes a heavy burden on the healthcare system, with costs expected to hit $20 billion by 2020 in the US.2 Therefore, treating asepsis cases as infections imposes a heavy burden on the healthcare system and may result in excessive morbidity.3 At the same time, inadequate management of a PJI may result in recurrences that require infection treatment with morbid procedures, such as arthrodesis or amputation. Accurate diagnosis of PJI is of paramount importance in preventing potential implications of a misdiagnosed case. Unfortunately, the PJI diagnosis is extremely challenging, and the available diagnostic tests are often unreliable.4 Thus, research has recently focused on use of several synovial fluid cytokines in the detection of PJI.5-7 In this article, we provide an overview of the synovial biomarkers being used to diagnose PJI.

Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infection

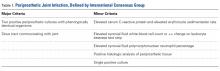

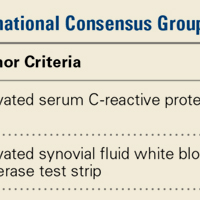

Differentiating between septic and aseptic failed TJA is important, as the treatment options differ considerably. PJI can be broadly classified as acute or early postoperative (<6 weeks), late chronic (indolent onset), and acute-on-chronic (acute onset in well-functioning prosthesis, secondary to hematogenous spread).8 The acute and acute-on-chronic presentations are often associated with obvious signs of infection.9 However, chronic and low-grade infections pose a challenge to modern orthopedic practice, as the symptoms often overlap with that of aseptic causes of TJA failure.10 As a result, the International Consensus Group on Periprosthetic Joint Infection developed complex criteria using the Musculoskeletal Infection Society definition of PJI and involving a battery of tests for PJI diagnosis.11 According to these criteria, PJI is diagnosed when 1 of the 2 major criteria or 3 of the 5 minor criteria are met (Table 1).

Although these criteria constitute the most agreed on and widely used standard for PJI diagnosis, the definition is complex and often incomplete until surgical intervention. An ideal diagnostic test would aid in managing a PJI and provide results before a treatment decision is made. Many revision surgeries are being performed with insufficient information about the true diagnosis, and the diagnosis might change during or after surgery. About 10% of the revisions presumed to be aseptic may unexpectedly grow cultures during surgery and thereby satisfy the criteria for PJI after surgery.12 Moreover, with the use of novel methods such as polymerase chain reaction, microorganisms were identified in more than three-fourths of the presumed aseptic revisions.13 The optimal management of such cases is controversial, and it is unclear whether positive cultures should be treated as possible contaminants or true infection.12,14

Verification of Infection Eradication

A 2-stage revision procedure, widely accepted as the standard treatment for PJI, has success rates approaching 94%.15 In this procedure, it is important to verify infection eradication before beginning the second-stage reimplantation. Verification is crucial in avoiding reimplantation of an infected joint.16 After the first stage, patients are usually administered intravenous antibiotics for at least 6 weeks; these antibiotics are then withheld, and systemic inflammatory markers are evaluated for infection eradication. Although reliable criteria have been established for PJI diagnosis, guidelines for detecting eradication of infection are rudimentary. Most surgeons monitor the decrease in serologic markers, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein (CRP) level, to assess the response to treatment. However, noninfectious etiologies may result in continued elevation of these markers.17 Even though aspirations are often performed to diagnose persistent infection before the second-stage procedure, their diagnostic utility may be limited.18 Use of cultures is also limited, as presence of antibiotic-loaded spacers can decrease the sensitivity of culture.19 Inadequate diagnosis often leads to unnecessary continuation of antimicrobial therapy or additional surgical débridement. Nuclear scans often remain positive because of aseptic inflammation related to surgery and are not useful in documenting sepsis arrest.20 Given the limitations of available tests, novel strategies for identifying the presence of infection at the second stage are being tested.

Synovial Fluid Cytokines

PJI pathogenesis begins with colonization of the implant surfaces with microorganisms and subsequent formation of biofilms.21 The human immune system is activated by the microbial products, cell wall components, and various biofilm proteins. Immune cells are recruited to the site, where they secrete a myriad of inflammatory biomarkers, such as cytokines, which promote further recruitment of inflammatory cells and aid in the eradication of pathogens.9 These inflammatory cytokines and cells are involved in aseptic inflammatory joint conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis22,23; however, some are specifically involved in immune pathways combating pathogens.24 This action is the basis for increasing interest in using various synovial fluid cytokines and other biomarkers in the diagnosis of PJI. Here we describe some of the commonly studied cytokines.

Interleukin 1β

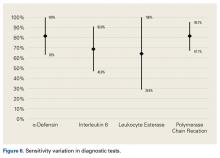

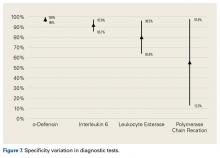

Interleukin 1β (IL-1β) is a major proinflammatory cytokine that is synthesized by multiple cells, including macrophages and monocytes.25 IL-1β is produced in response to microorganisms, other cytokines, antigen-presenting cells, and immune complexes; stimulates production of acute-phase proteins by the liver; and is an important pyrogen.25 Deirmengian and colleagues5 found that synovial IL-1β increased 258-fold in patients with a PJI. Studies have found that synovial IL-1β has sensitivity ranging from 66.7% to 100% and specificity ranging from 87% to 100%, with 1 study reporting an accuracy of 100%.5,6,26,27

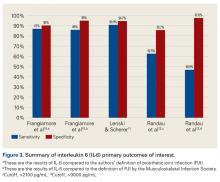

Interleukin 6

Also produced by macrophages and monocytes, interleukin 6 (IL-6) is a potent stimulator of acute-phase proteins.28,29 IL-6 has a role as a chemoattractant and helps with cell differentiation when changing from innate to acquired immunity.30 It is also used as an aid in diagnosing PJI; it has sensitivity ranging from 62% to 100% and specificity ranging from 85% to 100%.5,6,26,31,32 Synovial IL-6 measurements were more accurate than serum IL-6 measurements.26 Furthermore, synovial IL-6 can be increased up to 27-fold in PJI cases.5 In one study, synovial IL-6 levels >2100 pg/mL had sensitivity of 62.5% and specificity of 85.7% in PJI diagnosis26; in another study, an IL-6 threshold of 4270 pg/mL had sensitivity of 87.1%, specificity of 100%, and accuracy of 94.6%.31

C-Reactive Protein

CRP is an acute-phase reactant. Blood levels increase in response to aseptic inflammatory processes and systemic infection.33 CRP plays an important role in host defense by activating complement and helping mediate phagocytosis.33,34 Although serum CRP levels have been used in diagnosing PJIs,6 they can yield false-negative results.35,36 Therefore, attention turned to synovial CRP levels, which were found to be increased 13-fold in PJI cases.5 It has been shown that synovial CRP levels are significantly higher in infected vs noninfected prosthetic joints34 and had diagnostic accuracy better than that of serum CRP levels in diagnosing PJI.37 One study found that CRP at a threshold of 3.7 mg/L had sensitivity of 84%, specificity of 97.1%, and accuracy of 91.5%,37 whereas another study found that CRP at a threshold of 3.61 mg/L had sensitivity of 87.1%, specificity of 97.7%, and accuracy of 93.3%.31

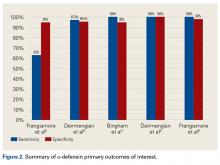

α-Defensin

α-Defensin, a natural peptide produced and secreted by neutrophils in response to pathogens, has antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties,38-40 signals for the secretion of various cytokines, and acts as a chemoattractant for various immune cells.41 Deirmengian and colleagues6 found that α-defensin was consistently elevated in patients with PJI. α-Defensin is extremely accurate in diagnosing PJI; it has sensitivity ranging from 97% to 100% and specificity ranging from 96% to 100%.6,27,42 Moreover, α-defensin was effective in diagnosing PJI caused by a wide spectrum of organisms, including various low-virulence bacteria and fungi.43

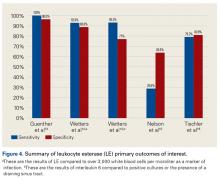

Leukocyte Esterase

Leukocyte esterase is an enzyme produced and secreted by neutrophils at sites of active infection.7,44 Testing for this enzyme is performed with a colorimetric strip and was originally performed for the diagnosis of urinary tract infections.44,45 In a study conducted by Parvizi and colleagues,7 this strip was used to test for leukocyte esterase in synovial fluid samples; a ++ reading was found to have sensitivity of 80.6% and specificity of 100% in diagnosing knee PJI. Similarly, De Vecchi and colleagues45 found sensitivity of 92.6% and specificity of 97%.

Other Synovial Markers

Research has identified numerous molecular biomarkers that may be associated with the pathogenesis of PJI. Although several (eg, cytokines) have demonstrated higher levels in synovial fluid in patients with PJI than in normal controls, only a few have had clinically relevant diagnostic utility.6 Deirmengian and colleagues6 screened 43 synovial fluid biomarkers that potentially could be used in the diagnosis of PJI. Besides the cytokine α-defensin, 4 other biomarkers—lactoferrin, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalcin, neutrophil elastase 2, and bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein—had accuracy of 100%. In addition, 8 cytokines and biomarkers (IL-8, CRP, resistin, thrombospondin, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-1α) had area under the curve values higher than 0.9. Studies have also evaluated the diagnostic utility of metabolic products such as lactate, lactate dehydrogenase, and glucose; their accuracy was comparable to that of serum CRP.32

Serum Markers

In addition to the synovial fluid cytokines, several serum inflammatory cytokines have been studied as potential targets in diagnosing infection. Serum IL-6 has had excellent diagnostic accuracy46 and, when combined with CRP, could increase sensitivity in diagnosing PJI; such a combination (vs either test alone) could be useful in screening patients.47,48 Biomarkers such as tumor necrosis factor α and procalcitonin are considered very specific for PJI and may be useful in confirmatory testing.48 Evidence also suggests that toll-like receptor 2 proteins are elevated in the serum of patients with PJI and therefore are a potential diagnostic tool.49

Limitations of Synovial Cytokines

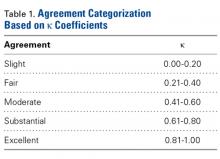

The literature suggests that some synovial fluid cytokines have promise.6 However, the best biomarker or combination of biomarkers is yet to be determined. Results have been consistent with α-defensin and other cytokines but mixed with IL-6 and still others32,42,50 (Table 2).

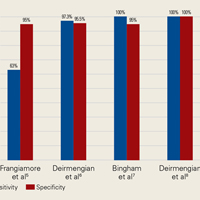

Information on the utility of synovial biomarkers in detecting persistent infection is limited. Frangiamore and colleagues50 found that IL-1 and IL-6 levels decreased between the stages of 2-stage revision. Unfortunately, none of the synovial fluid cytokines investigated (IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, Il-10, interferon γ, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor, tumor necrosis factor α, IL-12p70) satisfactorily detected resolution of infection in the setting of prior treatment for PJI. Although cytokines are expected to be elevated in the presence of infection, the internal milieu at the time of stage 2 of the revision makes diagnosis of infection difficult. In addition, presence of spacer particles and recent surgery may activate immune pathways and yield false-positive results. Furthermore, antibiotic cement spacers may suppress the microorganisms to very low levels and yield false-negative results even if these organisms remain virulent.19

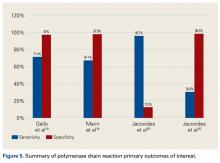

Even though the synovial molecular markers can detect the presence of infection, they are unable to identify pathogens. As identifying the pathogen is important in the treatment of PJI, there has been interest in using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques.51 These tests may also provide specific information about the pathogen, such as its antibiotic sensitivity. A recently developed technology, the Ibis T5000 Universal Biosensor (Ibis Biosciences), uses novel pan-domain primers in a series of PCRs. This biosensor is useful in diagnosing infections when cultures are negative and appears to be more accurate than conventional PCR.13 As reported by Jacovides and colleagues,13 this novel PCR technique identified an organism in about 88% of presumed cases of aseptic revision.

Conclusion

PJI poses an extreme challenge to the healthcare system. Given the morbidity associated with improper management of PJI, accurate diagnosis is of paramount importance. Given the limitations of current tests, synovial fluid cytokines hold promise in the diagnosis of PJIs. However, these cytokines are expensive, and their clinical utility in PJI management is not well established. More research is needed before guidelines for synovial fluid cytokines and biomarkers can replace or be incorporated into guidelines for the treatment of PJIs.

1 Parvizi J, Adeli B, Zmistowski B, Restrepo C, Greenwald AS. Management of periprosthetic joint infection: the current knowledge: AAOS exhibit selection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(14):e104.

2. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier JK, Parvizi J. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):61-65.e1.

3. Sierra RJ, Trousdale RT, Pagnano MW. Above-the-knee amputation after a total knee replacement: prevalence, etiology, and functional outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(6):1000-1004.

4. Bauer TW, Parvizi J, Kobayashi N, Krebs V. Diagnosis of periprosthetic infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(4):869-882.

5. Deirmengian C, Hallab N, Tarabishy A, et al. Synovial fluid biomarkers for periprosthetic infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(8):2017-2023.

6. Deirmengian C, Kardos K, Kilmartin P, Cameron A, Schiller K, Parvizi J. Diagnosing periprosthetic joint infection: has the era of the biomarker arrived? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(11):3254-3262.

7. Parvizi J, Jacovides C, Antoci V, Ghanem E. Diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection: the utility of a simple yet unappreciated enzyme. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2242-2248.

8. Kuiper JW, Willink RT, Moojen DJF, van den Bekerom MP, Colen S. Treatment of acute periprosthetic infections with prosthesis retention: review of current concepts. World J Orthop. 2014;5(5):667-676.

9. Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(16):1645-1654.

10. Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):e1-e25.

11. Parvizi J, Gehrke T; International Consensus Group on Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Definition of periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1331.

12. Saleh A, Guirguis A, Klika AK, Johnson L, Higuera CA, Barsoum WK. Unexpected positive intraoperative cultures in aseptic revision arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(11):2181-2186.

13. Jacovides CL, Kreft R, Adeli B, Hozack B, Ehrlich GD, Parvizi J. Successful identification of pathogens by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based electron spray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF-MS) in culture-negative periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(24):2247-2254.

14. Barrack RL, Aggarwal A, Burnett RS, et al. The fate of the unexpected positive intraoperative cultures after revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 suppl 2):94-99.