User login

Robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy

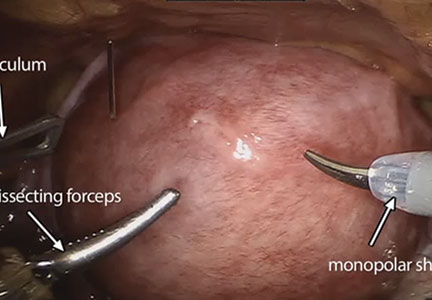

The management of symptomatic uterine fibroids in the patient desiring conservative surgical therapy can be challenging at times. The advent of robot-assisted laparoscopy has provided surgeons with an enabling tool and patients with the option for a minimally invasive approach to myomectomy.

This month’s video was produced in order to demonstrate a systematic approach to the robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy in patients who are candidates. The example case is removal of a 5-cm, intrauterine posterior myoma in a 39-year-old woman (G3P1021) with heavy menstrual bleeding who desires future fertility.

Key objectives of the video include:

- understanding the role of radiologic imaging as part of preoperative surgical planning

- recognizing the key robotic instruments and suture selected to perform the procedure

- discussing robot-specific techniques that facilitate fibroid enucleation and hysterotomy repair.

Also integrated into this video is the application of the ExCITE technique—a manual cold knife tissue extraction technique utilizing an extracorporeal semi-circle “C-incision” approach—for tissue extraction. This technique was featured in an earlier installment of the video channel.1

I hope that you find this month’s video helpful to your surgical practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Truong M, Advincula A. Minimally invasive tissue extraction made simple: the Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction (ExCITE) technique. OBG Manag. 2014;26(11):56.

The management of symptomatic uterine fibroids in the patient desiring conservative surgical therapy can be challenging at times. The advent of robot-assisted laparoscopy has provided surgeons with an enabling tool and patients with the option for a minimally invasive approach to myomectomy.

This month’s video was produced in order to demonstrate a systematic approach to the robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy in patients who are candidates. The example case is removal of a 5-cm, intrauterine posterior myoma in a 39-year-old woman (G3P1021) with heavy menstrual bleeding who desires future fertility.

Key objectives of the video include:

- understanding the role of radiologic imaging as part of preoperative surgical planning

- recognizing the key robotic instruments and suture selected to perform the procedure

- discussing robot-specific techniques that facilitate fibroid enucleation and hysterotomy repair.

Also integrated into this video is the application of the ExCITE technique—a manual cold knife tissue extraction technique utilizing an extracorporeal semi-circle “C-incision” approach—for tissue extraction. This technique was featured in an earlier installment of the video channel.1

I hope that you find this month’s video helpful to your surgical practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The management of symptomatic uterine fibroids in the patient desiring conservative surgical therapy can be challenging at times. The advent of robot-assisted laparoscopy has provided surgeons with an enabling tool and patients with the option for a minimally invasive approach to myomectomy.

This month’s video was produced in order to demonstrate a systematic approach to the robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy in patients who are candidates. The example case is removal of a 5-cm, intrauterine posterior myoma in a 39-year-old woman (G3P1021) with heavy menstrual bleeding who desires future fertility.

Key objectives of the video include:

- understanding the role of radiologic imaging as part of preoperative surgical planning

- recognizing the key robotic instruments and suture selected to perform the procedure

- discussing robot-specific techniques that facilitate fibroid enucleation and hysterotomy repair.

Also integrated into this video is the application of the ExCITE technique—a manual cold knife tissue extraction technique utilizing an extracorporeal semi-circle “C-incision” approach—for tissue extraction. This technique was featured in an earlier installment of the video channel.1

I hope that you find this month’s video helpful to your surgical practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Truong M, Advincula A. Minimally invasive tissue extraction made simple: the Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction (ExCITE) technique. OBG Manag. 2014;26(11):56.

- Truong M, Advincula A. Minimally invasive tissue extraction made simple: the Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction (ExCITE) technique. OBG Manag. 2014;26(11):56.

Is the use of a containment bag at minimally invasive hysterectomy or myomectomy effective at reducing tissue spillage?

Tissue extraction during laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic gynecologic surgery raises safety concerns for dissemination of tissue during the open, or uncontained, electromechanical morcellation process. Researchers from Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, investigated whether contained tissue extraction using power morcellators entirely within a bag is safe and practical for preventing tissue spillage. Goggins and colleagues presented their findings in a poster at the 2015 Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in San Francisco, California.

A total of 76 women at 4 institutions underwent laparoscopic or robotic multiport surgery (42 hysterectomy; 34 myomectomy). The average (SD) age and body mass index of the women were 43.16 (8.53) years and 26.47 kg/m2 (5.93), respectively. After surgical dissection, each specimen was placed into a containment bag that also included blue dye. The bag was insufflated intracorporeally and electromechanical morcellation and extraction of tissue were performed. The bag was evaluated visually for dye leakage or tears before and after the procedure.

Results

In one case, there was a tear in the bag before morcellation; no bag tears occurred during the morcellation process. Spillage of dye or tissue was noted in 7 cases, although containment bags were intact in each instance. One patient experienced intraoperative blood loss (3600 mL), and that procedure was converted to open radical hysterectomy. The most common pathologic finding was benign leiomyoma.

Conclusion

Goggins and colleagues concluded, “Contained tissue extraction using electromechanical morcellation and intracorporeally insufflated bags may provide a safe alternative to uncontained morcellation by decreasing the spread of tissue in the peritoneal cavity while allowing for the traditional benefits of laparoscopy.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- Goggins ER, Greenberg JA, Cohen SL, Morris SN, Brown DN, Einarsson JI. Efficacy of contained tissue extraction for minimizing tissue dissemination during laparoscopic hysterectomy and myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5)(suppl):29S.

Tissue extraction during laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic gynecologic surgery raises safety concerns for dissemination of tissue during the open, or uncontained, electromechanical morcellation process. Researchers from Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, investigated whether contained tissue extraction using power morcellators entirely within a bag is safe and practical for preventing tissue spillage. Goggins and colleagues presented their findings in a poster at the 2015 Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in San Francisco, California.

A total of 76 women at 4 institutions underwent laparoscopic or robotic multiport surgery (42 hysterectomy; 34 myomectomy). The average (SD) age and body mass index of the women were 43.16 (8.53) years and 26.47 kg/m2 (5.93), respectively. After surgical dissection, each specimen was placed into a containment bag that also included blue dye. The bag was insufflated intracorporeally and electromechanical morcellation and extraction of tissue were performed. The bag was evaluated visually for dye leakage or tears before and after the procedure.

Results

In one case, there was a tear in the bag before morcellation; no bag tears occurred during the morcellation process. Spillage of dye or tissue was noted in 7 cases, although containment bags were intact in each instance. One patient experienced intraoperative blood loss (3600 mL), and that procedure was converted to open radical hysterectomy. The most common pathologic finding was benign leiomyoma.

Conclusion

Goggins and colleagues concluded, “Contained tissue extraction using electromechanical morcellation and intracorporeally insufflated bags may provide a safe alternative to uncontained morcellation by decreasing the spread of tissue in the peritoneal cavity while allowing for the traditional benefits of laparoscopy.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Tissue extraction during laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic gynecologic surgery raises safety concerns for dissemination of tissue during the open, or uncontained, electromechanical morcellation process. Researchers from Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, investigated whether contained tissue extraction using power morcellators entirely within a bag is safe and practical for preventing tissue spillage. Goggins and colleagues presented their findings in a poster at the 2015 Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in San Francisco, California.

A total of 76 women at 4 institutions underwent laparoscopic or robotic multiport surgery (42 hysterectomy; 34 myomectomy). The average (SD) age and body mass index of the women were 43.16 (8.53) years and 26.47 kg/m2 (5.93), respectively. After surgical dissection, each specimen was placed into a containment bag that also included blue dye. The bag was insufflated intracorporeally and electromechanical morcellation and extraction of tissue were performed. The bag was evaluated visually for dye leakage or tears before and after the procedure.

Results

In one case, there was a tear in the bag before morcellation; no bag tears occurred during the morcellation process. Spillage of dye or tissue was noted in 7 cases, although containment bags were intact in each instance. One patient experienced intraoperative blood loss (3600 mL), and that procedure was converted to open radical hysterectomy. The most common pathologic finding was benign leiomyoma.

Conclusion

Goggins and colleagues concluded, “Contained tissue extraction using electromechanical morcellation and intracorporeally insufflated bags may provide a safe alternative to uncontained morcellation by decreasing the spread of tissue in the peritoneal cavity while allowing for the traditional benefits of laparoscopy.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- Goggins ER, Greenberg JA, Cohen SL, Morris SN, Brown DN, Einarsson JI. Efficacy of contained tissue extraction for minimizing tissue dissemination during laparoscopic hysterectomy and myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5)(suppl):29S.

Reference

- Goggins ER, Greenberg JA, Cohen SL, Morris SN, Brown DN, Einarsson JI. Efficacy of contained tissue extraction for minimizing tissue dissemination during laparoscopic hysterectomy and myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5)(suppl):29S.

What is the risk that a patient will have an occult uterine cancer at myomectomy?

Wright and colleagues analyzed the risk of diagnosing an occult uterine cancer at the time of myomectomy using an administrative database, which contained information on 41,777 myomectomy surgeries performed at 496 hospitals from 2006 to 2012. They reported that 76 uterine corpus cancers (ICD-9 codes 179.x and 182.x) were detected, for a rate of 1 occult cancer identified per 550 myomectomy cases. The risk of diagnosing an occult uterine cancer increased with age.

Study limitations

A major weakness of the study is that the administrative database did not provide information about the histologic type of uterine corpus cancer. Uterine leiomyosarcoma is a highly aggressive cancer, while endometrial stromal sarcoma is a more indolent cancer. Additionally, the authors were not able to perform a histologic reassessment of the slides of the 76 cases reported as having uterine corpus cancer in order to confirm the diagnosis. Although the investigators provide age-specific information about the risk of uterine cancer, they did not have information on the menopausal status of the women.

Strengths of the study

Prior to these study results there were few data about the risk of diagnosing an occult cancer at the time of myomectomy. This very large study of more than 41,000 myomectomy cases will help clinicians fully counsel women about the risk of detecting an occult uterine cancer at the time of myomectomy.

What this evidence means for practice

Women aged 50 years or older should be advised against having a myomectomy given the 1 in 154 and 1 in 31 risk of identifying an occult uterine corpus cancer at the time of surgery in women aged 50 to 59 years and 60 years or older, respectively. Given an average age of menopause of 51 years, these data support the guidance of the US Food and Drug Administration that open electric power morcellation should not be used in surgery on uterine tumors in women who are perimenopausal or postmenopausal.

–Robert L. Barbieri, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Wright and colleagues analyzed the risk of diagnosing an occult uterine cancer at the time of myomectomy using an administrative database, which contained information on 41,777 myomectomy surgeries performed at 496 hospitals from 2006 to 2012. They reported that 76 uterine corpus cancers (ICD-9 codes 179.x and 182.x) were detected, for a rate of 1 occult cancer identified per 550 myomectomy cases. The risk of diagnosing an occult uterine cancer increased with age.

Study limitations

A major weakness of the study is that the administrative database did not provide information about the histologic type of uterine corpus cancer. Uterine leiomyosarcoma is a highly aggressive cancer, while endometrial stromal sarcoma is a more indolent cancer. Additionally, the authors were not able to perform a histologic reassessment of the slides of the 76 cases reported as having uterine corpus cancer in order to confirm the diagnosis. Although the investigators provide age-specific information about the risk of uterine cancer, they did not have information on the menopausal status of the women.

Strengths of the study

Prior to these study results there were few data about the risk of diagnosing an occult cancer at the time of myomectomy. This very large study of more than 41,000 myomectomy cases will help clinicians fully counsel women about the risk of detecting an occult uterine cancer at the time of myomectomy.

What this evidence means for practice

Women aged 50 years or older should be advised against having a myomectomy given the 1 in 154 and 1 in 31 risk of identifying an occult uterine corpus cancer at the time of surgery in women aged 50 to 59 years and 60 years or older, respectively. Given an average age of menopause of 51 years, these data support the guidance of the US Food and Drug Administration that open electric power morcellation should not be used in surgery on uterine tumors in women who are perimenopausal or postmenopausal.

–Robert L. Barbieri, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Wright and colleagues analyzed the risk of diagnosing an occult uterine cancer at the time of myomectomy using an administrative database, which contained information on 41,777 myomectomy surgeries performed at 496 hospitals from 2006 to 2012. They reported that 76 uterine corpus cancers (ICD-9 codes 179.x and 182.x) were detected, for a rate of 1 occult cancer identified per 550 myomectomy cases. The risk of diagnosing an occult uterine cancer increased with age.

Study limitations

A major weakness of the study is that the administrative database did not provide information about the histologic type of uterine corpus cancer. Uterine leiomyosarcoma is a highly aggressive cancer, while endometrial stromal sarcoma is a more indolent cancer. Additionally, the authors were not able to perform a histologic reassessment of the slides of the 76 cases reported as having uterine corpus cancer in order to confirm the diagnosis. Although the investigators provide age-specific information about the risk of uterine cancer, they did not have information on the menopausal status of the women.

Strengths of the study

Prior to these study results there were few data about the risk of diagnosing an occult cancer at the time of myomectomy. This very large study of more than 41,000 myomectomy cases will help clinicians fully counsel women about the risk of detecting an occult uterine cancer at the time of myomectomy.

What this evidence means for practice

Women aged 50 years or older should be advised against having a myomectomy given the 1 in 154 and 1 in 31 risk of identifying an occult uterine corpus cancer at the time of surgery in women aged 50 to 59 years and 60 years or older, respectively. Given an average age of menopause of 51 years, these data support the guidance of the US Food and Drug Administration that open electric power morcellation should not be used in surgery on uterine tumors in women who are perimenopausal or postmenopausal.

–Robert L. Barbieri, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Hysteroscopic myomectomy using a mechanical approach

Uterine fibroids are a common complaint in gynecology, with an incidence of approximately 30% in women aged 25 to 45 years and a cumulative incidence of 70% to 80% by age 50.1,2 They are more prevalent in women of African descent and are a leading indication for hysterectomy.

Although they can be asymptomatic, submucosal fibroids are frequently associated with:

- abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB)

- dysmenorrhea

- expulsion of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- leukorrhea

- pelvic pain

- urinary frequency

- infertility

- premature labor

- reproductive wastage

- bleeding during hormone replacement therapy.

In postmenopausal women, the risk of malignancy in a leiomyoma ranges from 0.2% to 0.5%.1 The risk is lower in premenopausal women.

In this article, I describe the technique for hysteroscopic myomectomy using a mechanical approach (Truclear Tissue Removal System, Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA), which offers hysteroscopic morcellation as well as quick resection and efficient fluid management. (Note: Unlike open intraperitoneal morcellation, hysteroscopic morcellation carries a low risk of tissue spread.)

Classification of fibroids

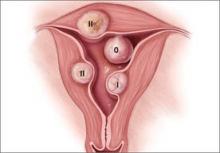

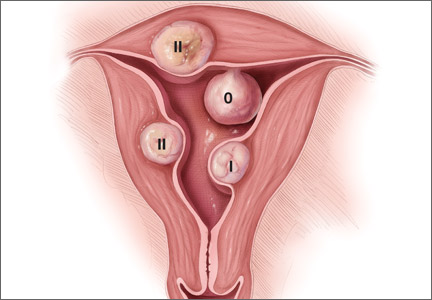

Preoperative classification of leiomyomas makes it possible to determine the best route for surgery. The most commonly used classification system was developed by the European Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) (FIGURE 1), which considers the extent of intramural extension. Each fibroid under that system is classified as:

- Type 0 – no intramural extension

- Type I – less than 50% extension

- Type II – more than 50% extension.

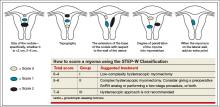

A second classification system recently was devised to take into account additional features of the fibroid. The STEP-W classification considers size, topography, extension, penetration, and the lateral wall (FIGURE 2). In general, the lower the score, the less complex the procedure will be, with a lower risk of fluid intravasation, shorter operative time, and a greater likelihood of complete removal of the fibroid.

A multicenter, prospective study of 449 women who underwent hysteroscopic resection of their fibroids correlated the ESGE and STEP-W systems. All 320 fibroids (100%) with a score of 4 or below on the STEP-W classification system were completely removed, compared with 112 of 145 fibroids (77.2%) with a score greater than 4. All 33 cases of incomplete hysteroscopic resection (100%) had a STEP-W score above 4.3

In the same study, 85 of 86 cases (98.9%) with Type 0 fibroids under the ESGE system had complete resection, along with 278 of 298 Type I fibroids (93.3%), and 69 of 81 Type II fibroids (85.2%).3 Complete removal is a goal because it relieves symptoms and averts the need for additional procedures.

Patient selection

Proper patient selection for hysteroscopic myomectomy is extremely important. The most common indications are AUB, pelvic pain or discomfort, recurrent pregnancy loss, and infertility. In addition, the patient should have a strong wish for uterine preservation and desire a minimally invasive transcervical approach.

AAGL guidelines on the diagnosis and management of submucous fibroids note that, in general, submucous leiomyomas as large as 4 or 5 cm in diameter can be removed hysteroscopically by experienced surgeons.4

A hysteroscopic approach is not advised for women in whom hysteroscopic surgery is contraindicated, such as women with intrauterine pregnancy, active pelvic infection, active herpes infection, or cervical or uterine cancer. Women who have medical comorbidities such as coronary heart disease, significant renal disease, or bleeding diathesis may need perioperative clearance from anesthesia or hematology prior to hysteroscopic surgery and close fluid monitoring during the procedure.

Consider the leiomyoma

Penetration into the myometrium. Women who have a fibroid that penetrates more than 50% into the myometrium may benefit from hysteroscopic myomectomy, provided the surgeon is highly experienced. A skilled hysteroscopist can ensure complete enucleation of a penetrating fibroid in these cases.

If you are still in the learning process for hysteroscopy, however, start with easier cases—ie, polyps and Type 0 and Type I fibroids. Type II fibroids require longer operative time, are associated with increased fluid absorption and intravasation, carry an increased risk of perioperative complications, and may not always be completely resected.

Size of the fibroid also is relevant. As size increases, so does the volume of tissue needing to be removed, adding to overall operative time.

Presence of other fibroids. When a woman has an intracavitary fibroid as well as myomas in other locations, the surgeon should consider whether hysteroscopic removal of the intracavitary lesion alone can provide significant relief of all fibroid-related symptoms. In such cases, laparoscopic, robotic, or abdominal myomectomy may be preferable, especially if the volume of the additional myomas is considerable.

To determine the optimal surgical route, the physician must consider the symptoms present—is AUB the only symptom, or are other fibroid-related conditions present as well, such as bulk, pelvic pain, and other quality-of-life issues? If multiple symptoms exist, then other approaches may be better.

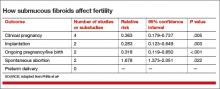

How fibroids affect fertility

Fibroids are present in 5% to 10% of women with infertility. In this population, fibroids are the only abnormal finding in 1.0% to 2.4% of cases.4

In a meta-analysis of 23 studies evaluating women with fibroids and infertility, Pritts and colleagues found nine studies involving submucosal fibroids.5 These studies included one randomized controlled trial, two prospective studies, and six retrospective analyses. They found that women who had fibroids with a submucosal component had lower pregnancy and implantation rates, compared with their infertile, myoma-free counterparts. Pritts and colleagues concluded that myomectomy is likely to improve fertility in these cases (TABLE).5

Instrumentation

Among the options are monopolar and bipolar resectoscopy and the mechanical approach using the Truclear System, which includes a morcellator. With conventional resectoscopy all chips must be removed, necessitating multiple insertions of the hysteroscope. Monopolar instrumentation, in particular, carries a risk of energy discharge to healthy tissue. The monopolar resectoscope also has a longer learning curve, compared with the mechanical approach.6

In contrast, the Truclear System requires fewer insertions, has a short learning curve, and omits the need for capture of individual chips, as the mechanical morcellator suctions and captures them throughout the procedure.7 In addition, because resection is performed mechanically, there is no risk of energy discharge to healthy tissue.

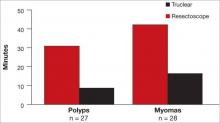

The Truclear system also is associated with a significantly shorter operative time, compared with resectoscopy, which may be advantageous for residents, fellows, and other physicians learning the procedure (FIGURE 3).7 Shorter operative time also may result in lower fluid deficits. In addition, saline distension may reduce the risk of fluid absorption and hyponatremia. The tissue-capture feature allows evaluation of the entire pathologic specimen.

Besides hysteroscopic myomectomy, the Truclear System is appropriate for visual dilatation and curettage (D&C), adhesiolysis, polypectomy, and evacuation of retained products of conception.

Preoperative evaluation

A complete history is vital to document which fibroid-related symptoms are present and how they affect quality of life.

Preoperative imaging also is imperative—using either 2D or 3D saline infusion sonography or a combination of diagnostic hysteroscopy and transvaginal ultrasound—to select patients for hysteroscopy, anticipate blood loss, and ensure that the proper instrumentation is available at the time of surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and hysterosalpingography are either prohibitively expensive or of limited value in the initial preoperative assessment of uterine fibroids.

Any woman who has AUB and a risk for endometrial hyperplasia or cancer should undergo endometrial assessment as well.

Use of preoperative medications

In most cases, prophylactic administration of antibiotics is not warranted to prevent infection or endocarditis.

Although some clinicians give gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists to reduce the size of large fibroids, the drug complicates dissection of the fibroid from the surrounding capsule. For this reason, and because we lack data demonstrating that GnRH agonists decrease blood loss and limit absorption of distension media, I do not administer them to patients.8–12 Moreover, this drug can cause vasomotor symptoms, cervical stenosis, and vaginal hemorrhage (related to estrogen flare).

GnRH agonists may be of value to stimulate transient amenorrhea for several months preoperatively in order to correct iron-deficiency anemia. Intravenous iron also can be administered during this interval.

The risk of bleeding in hysteroscopic myomectomy is 2% to 3%.1 When the mechanical approach is used, rather than resectoscopy, continuous flow coupled with suctioning of the chips during the procedure keeps the image clear. Post-procedure contraction of the uterus stops most bleeding. Intrauterine pressure of the pump can be increased to help tamponade any oozing.

Misoprostol. Cervical stenosis is not uncommon in menopausal women. It can also pose a challenge in nulliparous women. Attempting hysteroscopy in the setting of cervical stenosis increases the risk of cervical laceration, creation of a false passage, and uterine perforation. For this reason, I prescribe oral or vaginal misoprostol 200 to 400 µg nightly for 1 to 2 days before the procedure.

Vasopressin can reduce blood loss during hysteroscopic myomectomy when it is injected into the cervical stroma preoperatively. It also reduces absorption of distension fluid and facilitates cervical dilation.

However, vasopressin must be injected with extreme care, with aspiration to confirm the absence of blood prior to each injection, as intravascular injection can lead to bradycardia, profound hypertension, and even death.13 Always notify the anesthesiologist prior to injection when vasopressin will be administered.

I routinely use vasopressin before hysteroscopic myomectomy (0.5 mg in 20 cc of saline or 20 U in 100 cc), injecting 5 cc of the solution at 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock positions.

Anesthesia during hysteroscopic myomectomy typically is “monitored anesthesia care,” or MAC, which consists of local anesthesia with sedation and analgesia. The need for regional or general anesthesia is rare. Consider adding a pericervical block or intravenous ketorolac (Toradol) to provide postoperative analgesia.

Surgical technique

Strict attention to fluid management is required throughout the procedure, preferably in accordance with AAGL guidelines on the management of hysteroscopic distending media.14 With the mechanical approach, because the distension fluid is isotonic (normal saline), it does not increase the risk of hyponatremia but can cause pulmonary edema or congestive heart failure. Intravasation usually is the result of excessive operative time, treatment of deeper myometrial fibroids (Type I or II), or high intrauterine pressure. I operate using intrauterine pressure in the range of 75 to 125 mm Hg.

The steps involved in the mechanical hysteroscopy approach are:

- Insert the hysteroscope into the uterus under direct visualization. In general, the greater the number of insertions, the greater the risk of uterine perforation. Preoperative cervical ripening helps facilitate insertion (see “Misoprostol” above).

- Distend the uterus with saline and inspect the uterine cavity, noting again the size and location of the fibroids and whether they are sessile or pedunculated.

- Locate the fibroid or other pathology to be removed, and place the morcellator window against it to begin cutting. Use the tip of the morcellator to elevate the fibroid for easier cutting. Enucleation is accomplished largely by varying the intrauterine pressure, which permits uterine decompression and myometrial contraction and renders the fibroid capsule more visible. If necessary, the hysteroscope can be withdrawn to stimulate myometrial contraction, which also helps to delineate the fibroid capsule.

- Reinspect the uterus to rule out perforation and remove any additional intrauterine pathology with a targeted view.

- Once all designated fibroids have been removed, withdraw the morcellator and hysteroscope from the uterus.

- Inspect the endocervical landscape to rule out injury and other pathology.

- Careful preoperative evaluation is important, preferably using diagnostic hysteroscopy or saline infusion sonography, to choose the optimal route of myomectomy and plan the surgical approach.

- During the myomectomy, pay close attention to fluid management and adhere strictly to predetermined limits.

- Complete removal of the fibroid is essential to relieve symptoms and avert the need for additional procedures.

Postoperative care

A nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or limited use of narcotics usually is sufficient to relieve any postoperative cramping or vaginal discomfort.

Advise the patient to notify you in the event of increasing pain, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, or fever.

Also counsel her that she can return to most normal activities within 24 to 48 hours. Sexual activity is permissible 1 week after surgery. Early and frequent ambulation is important.

Schedule a follow-up visit 4 to 6 weeks after the procedure.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Perez-Medina T, Font EC, eds. Diagnostic and Operative Hysteroscopy. Tunbridge Wells, Kent, UK: Anshan Publishing; 2007:13.

2. Management of uterine fibroids: an update of the evidence. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://archive.ahrq.gov/clinic/tp/uteruptp.htm. Published July 2007. Accessed January 14, 2015.

3. Lasmar RB, Zinmei Z, Indman PD, Celeste RK, Di Spiezo Sardo A. Feasibility of a new system of classification of submucous myomas: a multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(6):2073–2077.

4. AAGL Practice Report: practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of submucous leiomyomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(2):152–171.

5. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1215–1223.

6. Van Dongen H, Emanuel MH, Wolterbeek R, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Hysteroscopic morcellator for removal of intrauterine polyps and myomas: a randomized controlled pilot study among residents in training. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(4):466–471.

7. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K. The intra uterine morcellator: a new hysteroscopic operating technique to remove intrauterine polyps and myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(1):62–66.

8. Emanuel MH, Hart A, Wamsteker K, Lammes F. An analysis of fluid loss during transcervical resection of submucous myomas. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(5):881–886.

9. Taskin O, Sadik S, Onoglu A, et al. Role of endometrial suppression on the frequency of intrauterine adhesions after resectoscopic surgery. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):351.

10. Propst AM, Liberman RF, Harlow BL, Ginsburg ES. Complications of hysteroscopic surgery: predicting patients at risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(4):517–520.

11. Perino A, Chianchiano N, Petronio M, Cittadini E. Role of leuprolide acetate depot in hysteroscopic surgery: a controlled study. Fertil Steril. 1993;59(3):507–510.

12. Mencaglia L, Tantini C. GnRH agonist analogs and hysteroscopic resection of myomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;43(3):285–288.

13. Hobo R, Netsu S, Koyasu Y, Tsutsumi O. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest caused by intramyometrial injection of vasopressin during a laparoscopically assisted myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 2):484–486.

14. Munro MD, Storz K, Abbott JA, et al; AAGL. AAGL Practice Report: practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):137–148.

Uterine fibroids are a common complaint in gynecology, with an incidence of approximately 30% in women aged 25 to 45 years and a cumulative incidence of 70% to 80% by age 50.1,2 They are more prevalent in women of African descent and are a leading indication for hysterectomy.

Although they can be asymptomatic, submucosal fibroids are frequently associated with:

- abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB)

- dysmenorrhea

- expulsion of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- leukorrhea

- pelvic pain

- urinary frequency

- infertility

- premature labor

- reproductive wastage

- bleeding during hormone replacement therapy.

In postmenopausal women, the risk of malignancy in a leiomyoma ranges from 0.2% to 0.5%.1 The risk is lower in premenopausal women.

In this article, I describe the technique for hysteroscopic myomectomy using a mechanical approach (Truclear Tissue Removal System, Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA), which offers hysteroscopic morcellation as well as quick resection and efficient fluid management. (Note: Unlike open intraperitoneal morcellation, hysteroscopic morcellation carries a low risk of tissue spread.)

Classification of fibroids

Preoperative classification of leiomyomas makes it possible to determine the best route for surgery. The most commonly used classification system was developed by the European Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) (FIGURE 1), which considers the extent of intramural extension. Each fibroid under that system is classified as:

- Type 0 – no intramural extension

- Type I – less than 50% extension

- Type II – more than 50% extension.

A second classification system recently was devised to take into account additional features of the fibroid. The STEP-W classification considers size, topography, extension, penetration, and the lateral wall (FIGURE 2). In general, the lower the score, the less complex the procedure will be, with a lower risk of fluid intravasation, shorter operative time, and a greater likelihood of complete removal of the fibroid.

A multicenter, prospective study of 449 women who underwent hysteroscopic resection of their fibroids correlated the ESGE and STEP-W systems. All 320 fibroids (100%) with a score of 4 or below on the STEP-W classification system were completely removed, compared with 112 of 145 fibroids (77.2%) with a score greater than 4. All 33 cases of incomplete hysteroscopic resection (100%) had a STEP-W score above 4.3

In the same study, 85 of 86 cases (98.9%) with Type 0 fibroids under the ESGE system had complete resection, along with 278 of 298 Type I fibroids (93.3%), and 69 of 81 Type II fibroids (85.2%).3 Complete removal is a goal because it relieves symptoms and averts the need for additional procedures.

Patient selection

Proper patient selection for hysteroscopic myomectomy is extremely important. The most common indications are AUB, pelvic pain or discomfort, recurrent pregnancy loss, and infertility. In addition, the patient should have a strong wish for uterine preservation and desire a minimally invasive transcervical approach.

AAGL guidelines on the diagnosis and management of submucous fibroids note that, in general, submucous leiomyomas as large as 4 or 5 cm in diameter can be removed hysteroscopically by experienced surgeons.4

A hysteroscopic approach is not advised for women in whom hysteroscopic surgery is contraindicated, such as women with intrauterine pregnancy, active pelvic infection, active herpes infection, or cervical or uterine cancer. Women who have medical comorbidities such as coronary heart disease, significant renal disease, or bleeding diathesis may need perioperative clearance from anesthesia or hematology prior to hysteroscopic surgery and close fluid monitoring during the procedure.

Consider the leiomyoma

Penetration into the myometrium. Women who have a fibroid that penetrates more than 50% into the myometrium may benefit from hysteroscopic myomectomy, provided the surgeon is highly experienced. A skilled hysteroscopist can ensure complete enucleation of a penetrating fibroid in these cases.

If you are still in the learning process for hysteroscopy, however, start with easier cases—ie, polyps and Type 0 and Type I fibroids. Type II fibroids require longer operative time, are associated with increased fluid absorption and intravasation, carry an increased risk of perioperative complications, and may not always be completely resected.

Size of the fibroid also is relevant. As size increases, so does the volume of tissue needing to be removed, adding to overall operative time.

Presence of other fibroids. When a woman has an intracavitary fibroid as well as myomas in other locations, the surgeon should consider whether hysteroscopic removal of the intracavitary lesion alone can provide significant relief of all fibroid-related symptoms. In such cases, laparoscopic, robotic, or abdominal myomectomy may be preferable, especially if the volume of the additional myomas is considerable.

To determine the optimal surgical route, the physician must consider the symptoms present—is AUB the only symptom, or are other fibroid-related conditions present as well, such as bulk, pelvic pain, and other quality-of-life issues? If multiple symptoms exist, then other approaches may be better.

How fibroids affect fertility

Fibroids are present in 5% to 10% of women with infertility. In this population, fibroids are the only abnormal finding in 1.0% to 2.4% of cases.4

In a meta-analysis of 23 studies evaluating women with fibroids and infertility, Pritts and colleagues found nine studies involving submucosal fibroids.5 These studies included one randomized controlled trial, two prospective studies, and six retrospective analyses. They found that women who had fibroids with a submucosal component had lower pregnancy and implantation rates, compared with their infertile, myoma-free counterparts. Pritts and colleagues concluded that myomectomy is likely to improve fertility in these cases (TABLE).5

Instrumentation

Among the options are monopolar and bipolar resectoscopy and the mechanical approach using the Truclear System, which includes a morcellator. With conventional resectoscopy all chips must be removed, necessitating multiple insertions of the hysteroscope. Monopolar instrumentation, in particular, carries a risk of energy discharge to healthy tissue. The monopolar resectoscope also has a longer learning curve, compared with the mechanical approach.6

In contrast, the Truclear System requires fewer insertions, has a short learning curve, and omits the need for capture of individual chips, as the mechanical morcellator suctions and captures them throughout the procedure.7 In addition, because resection is performed mechanically, there is no risk of energy discharge to healthy tissue.

The Truclear system also is associated with a significantly shorter operative time, compared with resectoscopy, which may be advantageous for residents, fellows, and other physicians learning the procedure (FIGURE 3).7 Shorter operative time also may result in lower fluid deficits. In addition, saline distension may reduce the risk of fluid absorption and hyponatremia. The tissue-capture feature allows evaluation of the entire pathologic specimen.

Besides hysteroscopic myomectomy, the Truclear System is appropriate for visual dilatation and curettage (D&C), adhesiolysis, polypectomy, and evacuation of retained products of conception.

Preoperative evaluation

A complete history is vital to document which fibroid-related symptoms are present and how they affect quality of life.

Preoperative imaging also is imperative—using either 2D or 3D saline infusion sonography or a combination of diagnostic hysteroscopy and transvaginal ultrasound—to select patients for hysteroscopy, anticipate blood loss, and ensure that the proper instrumentation is available at the time of surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and hysterosalpingography are either prohibitively expensive or of limited value in the initial preoperative assessment of uterine fibroids.

Any woman who has AUB and a risk for endometrial hyperplasia or cancer should undergo endometrial assessment as well.

Use of preoperative medications

In most cases, prophylactic administration of antibiotics is not warranted to prevent infection or endocarditis.

Although some clinicians give gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists to reduce the size of large fibroids, the drug complicates dissection of the fibroid from the surrounding capsule. For this reason, and because we lack data demonstrating that GnRH agonists decrease blood loss and limit absorption of distension media, I do not administer them to patients.8–12 Moreover, this drug can cause vasomotor symptoms, cervical stenosis, and vaginal hemorrhage (related to estrogen flare).

GnRH agonists may be of value to stimulate transient amenorrhea for several months preoperatively in order to correct iron-deficiency anemia. Intravenous iron also can be administered during this interval.

The risk of bleeding in hysteroscopic myomectomy is 2% to 3%.1 When the mechanical approach is used, rather than resectoscopy, continuous flow coupled with suctioning of the chips during the procedure keeps the image clear. Post-procedure contraction of the uterus stops most bleeding. Intrauterine pressure of the pump can be increased to help tamponade any oozing.

Misoprostol. Cervical stenosis is not uncommon in menopausal women. It can also pose a challenge in nulliparous women. Attempting hysteroscopy in the setting of cervical stenosis increases the risk of cervical laceration, creation of a false passage, and uterine perforation. For this reason, I prescribe oral or vaginal misoprostol 200 to 400 µg nightly for 1 to 2 days before the procedure.

Vasopressin can reduce blood loss during hysteroscopic myomectomy when it is injected into the cervical stroma preoperatively. It also reduces absorption of distension fluid and facilitates cervical dilation.

However, vasopressin must be injected with extreme care, with aspiration to confirm the absence of blood prior to each injection, as intravascular injection can lead to bradycardia, profound hypertension, and even death.13 Always notify the anesthesiologist prior to injection when vasopressin will be administered.

I routinely use vasopressin before hysteroscopic myomectomy (0.5 mg in 20 cc of saline or 20 U in 100 cc), injecting 5 cc of the solution at 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock positions.

Anesthesia during hysteroscopic myomectomy typically is “monitored anesthesia care,” or MAC, which consists of local anesthesia with sedation and analgesia. The need for regional or general anesthesia is rare. Consider adding a pericervical block or intravenous ketorolac (Toradol) to provide postoperative analgesia.

Surgical technique

Strict attention to fluid management is required throughout the procedure, preferably in accordance with AAGL guidelines on the management of hysteroscopic distending media.14 With the mechanical approach, because the distension fluid is isotonic (normal saline), it does not increase the risk of hyponatremia but can cause pulmonary edema or congestive heart failure. Intravasation usually is the result of excessive operative time, treatment of deeper myometrial fibroids (Type I or II), or high intrauterine pressure. I operate using intrauterine pressure in the range of 75 to 125 mm Hg.

The steps involved in the mechanical hysteroscopy approach are:

- Insert the hysteroscope into the uterus under direct visualization. In general, the greater the number of insertions, the greater the risk of uterine perforation. Preoperative cervical ripening helps facilitate insertion (see “Misoprostol” above).

- Distend the uterus with saline and inspect the uterine cavity, noting again the size and location of the fibroids and whether they are sessile or pedunculated.

- Locate the fibroid or other pathology to be removed, and place the morcellator window against it to begin cutting. Use the tip of the morcellator to elevate the fibroid for easier cutting. Enucleation is accomplished largely by varying the intrauterine pressure, which permits uterine decompression and myometrial contraction and renders the fibroid capsule more visible. If necessary, the hysteroscope can be withdrawn to stimulate myometrial contraction, which also helps to delineate the fibroid capsule.

- Reinspect the uterus to rule out perforation and remove any additional intrauterine pathology with a targeted view.

- Once all designated fibroids have been removed, withdraw the morcellator and hysteroscope from the uterus.

- Inspect the endocervical landscape to rule out injury and other pathology.

- Careful preoperative evaluation is important, preferably using diagnostic hysteroscopy or saline infusion sonography, to choose the optimal route of myomectomy and plan the surgical approach.

- During the myomectomy, pay close attention to fluid management and adhere strictly to predetermined limits.

- Complete removal of the fibroid is essential to relieve symptoms and avert the need for additional procedures.

Postoperative care

A nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or limited use of narcotics usually is sufficient to relieve any postoperative cramping or vaginal discomfort.

Advise the patient to notify you in the event of increasing pain, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, or fever.

Also counsel her that she can return to most normal activities within 24 to 48 hours. Sexual activity is permissible 1 week after surgery. Early and frequent ambulation is important.

Schedule a follow-up visit 4 to 6 weeks after the procedure.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Uterine fibroids are a common complaint in gynecology, with an incidence of approximately 30% in women aged 25 to 45 years and a cumulative incidence of 70% to 80% by age 50.1,2 They are more prevalent in women of African descent and are a leading indication for hysterectomy.

Although they can be asymptomatic, submucosal fibroids are frequently associated with:

- abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB)

- dysmenorrhea

- expulsion of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- leukorrhea

- pelvic pain

- urinary frequency

- infertility

- premature labor

- reproductive wastage

- bleeding during hormone replacement therapy.

In postmenopausal women, the risk of malignancy in a leiomyoma ranges from 0.2% to 0.5%.1 The risk is lower in premenopausal women.

In this article, I describe the technique for hysteroscopic myomectomy using a mechanical approach (Truclear Tissue Removal System, Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA), which offers hysteroscopic morcellation as well as quick resection and efficient fluid management. (Note: Unlike open intraperitoneal morcellation, hysteroscopic morcellation carries a low risk of tissue spread.)

Classification of fibroids

Preoperative classification of leiomyomas makes it possible to determine the best route for surgery. The most commonly used classification system was developed by the European Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) (FIGURE 1), which considers the extent of intramural extension. Each fibroid under that system is classified as:

- Type 0 – no intramural extension

- Type I – less than 50% extension

- Type II – more than 50% extension.

A second classification system recently was devised to take into account additional features of the fibroid. The STEP-W classification considers size, topography, extension, penetration, and the lateral wall (FIGURE 2). In general, the lower the score, the less complex the procedure will be, with a lower risk of fluid intravasation, shorter operative time, and a greater likelihood of complete removal of the fibroid.

A multicenter, prospective study of 449 women who underwent hysteroscopic resection of their fibroids correlated the ESGE and STEP-W systems. All 320 fibroids (100%) with a score of 4 or below on the STEP-W classification system were completely removed, compared with 112 of 145 fibroids (77.2%) with a score greater than 4. All 33 cases of incomplete hysteroscopic resection (100%) had a STEP-W score above 4.3

In the same study, 85 of 86 cases (98.9%) with Type 0 fibroids under the ESGE system had complete resection, along with 278 of 298 Type I fibroids (93.3%), and 69 of 81 Type II fibroids (85.2%).3 Complete removal is a goal because it relieves symptoms and averts the need for additional procedures.

Patient selection

Proper patient selection for hysteroscopic myomectomy is extremely important. The most common indications are AUB, pelvic pain or discomfort, recurrent pregnancy loss, and infertility. In addition, the patient should have a strong wish for uterine preservation and desire a minimally invasive transcervical approach.

AAGL guidelines on the diagnosis and management of submucous fibroids note that, in general, submucous leiomyomas as large as 4 or 5 cm in diameter can be removed hysteroscopically by experienced surgeons.4

A hysteroscopic approach is not advised for women in whom hysteroscopic surgery is contraindicated, such as women with intrauterine pregnancy, active pelvic infection, active herpes infection, or cervical or uterine cancer. Women who have medical comorbidities such as coronary heart disease, significant renal disease, or bleeding diathesis may need perioperative clearance from anesthesia or hematology prior to hysteroscopic surgery and close fluid monitoring during the procedure.

Consider the leiomyoma

Penetration into the myometrium. Women who have a fibroid that penetrates more than 50% into the myometrium may benefit from hysteroscopic myomectomy, provided the surgeon is highly experienced. A skilled hysteroscopist can ensure complete enucleation of a penetrating fibroid in these cases.

If you are still in the learning process for hysteroscopy, however, start with easier cases—ie, polyps and Type 0 and Type I fibroids. Type II fibroids require longer operative time, are associated with increased fluid absorption and intravasation, carry an increased risk of perioperative complications, and may not always be completely resected.

Size of the fibroid also is relevant. As size increases, so does the volume of tissue needing to be removed, adding to overall operative time.

Presence of other fibroids. When a woman has an intracavitary fibroid as well as myomas in other locations, the surgeon should consider whether hysteroscopic removal of the intracavitary lesion alone can provide significant relief of all fibroid-related symptoms. In such cases, laparoscopic, robotic, or abdominal myomectomy may be preferable, especially if the volume of the additional myomas is considerable.

To determine the optimal surgical route, the physician must consider the symptoms present—is AUB the only symptom, or are other fibroid-related conditions present as well, such as bulk, pelvic pain, and other quality-of-life issues? If multiple symptoms exist, then other approaches may be better.

How fibroids affect fertility

Fibroids are present in 5% to 10% of women with infertility. In this population, fibroids are the only abnormal finding in 1.0% to 2.4% of cases.4

In a meta-analysis of 23 studies evaluating women with fibroids and infertility, Pritts and colleagues found nine studies involving submucosal fibroids.5 These studies included one randomized controlled trial, two prospective studies, and six retrospective analyses. They found that women who had fibroids with a submucosal component had lower pregnancy and implantation rates, compared with their infertile, myoma-free counterparts. Pritts and colleagues concluded that myomectomy is likely to improve fertility in these cases (TABLE).5

Instrumentation

Among the options are monopolar and bipolar resectoscopy and the mechanical approach using the Truclear System, which includes a morcellator. With conventional resectoscopy all chips must be removed, necessitating multiple insertions of the hysteroscope. Monopolar instrumentation, in particular, carries a risk of energy discharge to healthy tissue. The monopolar resectoscope also has a longer learning curve, compared with the mechanical approach.6

In contrast, the Truclear System requires fewer insertions, has a short learning curve, and omits the need for capture of individual chips, as the mechanical morcellator suctions and captures them throughout the procedure.7 In addition, because resection is performed mechanically, there is no risk of energy discharge to healthy tissue.

The Truclear system also is associated with a significantly shorter operative time, compared with resectoscopy, which may be advantageous for residents, fellows, and other physicians learning the procedure (FIGURE 3).7 Shorter operative time also may result in lower fluid deficits. In addition, saline distension may reduce the risk of fluid absorption and hyponatremia. The tissue-capture feature allows evaluation of the entire pathologic specimen.

Besides hysteroscopic myomectomy, the Truclear System is appropriate for visual dilatation and curettage (D&C), adhesiolysis, polypectomy, and evacuation of retained products of conception.

Preoperative evaluation

A complete history is vital to document which fibroid-related symptoms are present and how they affect quality of life.

Preoperative imaging also is imperative—using either 2D or 3D saline infusion sonography or a combination of diagnostic hysteroscopy and transvaginal ultrasound—to select patients for hysteroscopy, anticipate blood loss, and ensure that the proper instrumentation is available at the time of surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and hysterosalpingography are either prohibitively expensive or of limited value in the initial preoperative assessment of uterine fibroids.

Any woman who has AUB and a risk for endometrial hyperplasia or cancer should undergo endometrial assessment as well.

Use of preoperative medications

In most cases, prophylactic administration of antibiotics is not warranted to prevent infection or endocarditis.

Although some clinicians give gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists to reduce the size of large fibroids, the drug complicates dissection of the fibroid from the surrounding capsule. For this reason, and because we lack data demonstrating that GnRH agonists decrease blood loss and limit absorption of distension media, I do not administer them to patients.8–12 Moreover, this drug can cause vasomotor symptoms, cervical stenosis, and vaginal hemorrhage (related to estrogen flare).

GnRH agonists may be of value to stimulate transient amenorrhea for several months preoperatively in order to correct iron-deficiency anemia. Intravenous iron also can be administered during this interval.

The risk of bleeding in hysteroscopic myomectomy is 2% to 3%.1 When the mechanical approach is used, rather than resectoscopy, continuous flow coupled with suctioning of the chips during the procedure keeps the image clear. Post-procedure contraction of the uterus stops most bleeding. Intrauterine pressure of the pump can be increased to help tamponade any oozing.

Misoprostol. Cervical stenosis is not uncommon in menopausal women. It can also pose a challenge in nulliparous women. Attempting hysteroscopy in the setting of cervical stenosis increases the risk of cervical laceration, creation of a false passage, and uterine perforation. For this reason, I prescribe oral or vaginal misoprostol 200 to 400 µg nightly for 1 to 2 days before the procedure.

Vasopressin can reduce blood loss during hysteroscopic myomectomy when it is injected into the cervical stroma preoperatively. It also reduces absorption of distension fluid and facilitates cervical dilation.

However, vasopressin must be injected with extreme care, with aspiration to confirm the absence of blood prior to each injection, as intravascular injection can lead to bradycardia, profound hypertension, and even death.13 Always notify the anesthesiologist prior to injection when vasopressin will be administered.

I routinely use vasopressin before hysteroscopic myomectomy (0.5 mg in 20 cc of saline or 20 U in 100 cc), injecting 5 cc of the solution at 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock positions.

Anesthesia during hysteroscopic myomectomy typically is “monitored anesthesia care,” or MAC, which consists of local anesthesia with sedation and analgesia. The need for regional or general anesthesia is rare. Consider adding a pericervical block or intravenous ketorolac (Toradol) to provide postoperative analgesia.

Surgical technique

Strict attention to fluid management is required throughout the procedure, preferably in accordance with AAGL guidelines on the management of hysteroscopic distending media.14 With the mechanical approach, because the distension fluid is isotonic (normal saline), it does not increase the risk of hyponatremia but can cause pulmonary edema or congestive heart failure. Intravasation usually is the result of excessive operative time, treatment of deeper myometrial fibroids (Type I or II), or high intrauterine pressure. I operate using intrauterine pressure in the range of 75 to 125 mm Hg.

The steps involved in the mechanical hysteroscopy approach are:

- Insert the hysteroscope into the uterus under direct visualization. In general, the greater the number of insertions, the greater the risk of uterine perforation. Preoperative cervical ripening helps facilitate insertion (see “Misoprostol” above).

- Distend the uterus with saline and inspect the uterine cavity, noting again the size and location of the fibroids and whether they are sessile or pedunculated.

- Locate the fibroid or other pathology to be removed, and place the morcellator window against it to begin cutting. Use the tip of the morcellator to elevate the fibroid for easier cutting. Enucleation is accomplished largely by varying the intrauterine pressure, which permits uterine decompression and myometrial contraction and renders the fibroid capsule more visible. If necessary, the hysteroscope can be withdrawn to stimulate myometrial contraction, which also helps to delineate the fibroid capsule.

- Reinspect the uterus to rule out perforation and remove any additional intrauterine pathology with a targeted view.

- Once all designated fibroids have been removed, withdraw the morcellator and hysteroscope from the uterus.

- Inspect the endocervical landscape to rule out injury and other pathology.

- Careful preoperative evaluation is important, preferably using diagnostic hysteroscopy or saline infusion sonography, to choose the optimal route of myomectomy and plan the surgical approach.

- During the myomectomy, pay close attention to fluid management and adhere strictly to predetermined limits.

- Complete removal of the fibroid is essential to relieve symptoms and avert the need for additional procedures.

Postoperative care

A nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or limited use of narcotics usually is sufficient to relieve any postoperative cramping or vaginal discomfort.

Advise the patient to notify you in the event of increasing pain, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, or fever.

Also counsel her that she can return to most normal activities within 24 to 48 hours. Sexual activity is permissible 1 week after surgery. Early and frequent ambulation is important.

Schedule a follow-up visit 4 to 6 weeks after the procedure.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Perez-Medina T, Font EC, eds. Diagnostic and Operative Hysteroscopy. Tunbridge Wells, Kent, UK: Anshan Publishing; 2007:13.

2. Management of uterine fibroids: an update of the evidence. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://archive.ahrq.gov/clinic/tp/uteruptp.htm. Published July 2007. Accessed January 14, 2015.

3. Lasmar RB, Zinmei Z, Indman PD, Celeste RK, Di Spiezo Sardo A. Feasibility of a new system of classification of submucous myomas: a multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(6):2073–2077.

4. AAGL Practice Report: practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of submucous leiomyomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(2):152–171.

5. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1215–1223.

6. Van Dongen H, Emanuel MH, Wolterbeek R, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Hysteroscopic morcellator for removal of intrauterine polyps and myomas: a randomized controlled pilot study among residents in training. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(4):466–471.

7. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K. The intra uterine morcellator: a new hysteroscopic operating technique to remove intrauterine polyps and myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(1):62–66.

8. Emanuel MH, Hart A, Wamsteker K, Lammes F. An analysis of fluid loss during transcervical resection of submucous myomas. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(5):881–886.

9. Taskin O, Sadik S, Onoglu A, et al. Role of endometrial suppression on the frequency of intrauterine adhesions after resectoscopic surgery. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):351.

10. Propst AM, Liberman RF, Harlow BL, Ginsburg ES. Complications of hysteroscopic surgery: predicting patients at risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(4):517–520.

11. Perino A, Chianchiano N, Petronio M, Cittadini E. Role of leuprolide acetate depot in hysteroscopic surgery: a controlled study. Fertil Steril. 1993;59(3):507–510.

12. Mencaglia L, Tantini C. GnRH agonist analogs and hysteroscopic resection of myomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;43(3):285–288.

13. Hobo R, Netsu S, Koyasu Y, Tsutsumi O. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest caused by intramyometrial injection of vasopressin during a laparoscopically assisted myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 2):484–486.

14. Munro MD, Storz K, Abbott JA, et al; AAGL. AAGL Practice Report: practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):137–148.

1. Perez-Medina T, Font EC, eds. Diagnostic and Operative Hysteroscopy. Tunbridge Wells, Kent, UK: Anshan Publishing; 2007:13.

2. Management of uterine fibroids: an update of the evidence. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://archive.ahrq.gov/clinic/tp/uteruptp.htm. Published July 2007. Accessed January 14, 2015.

3. Lasmar RB, Zinmei Z, Indman PD, Celeste RK, Di Spiezo Sardo A. Feasibility of a new system of classification of submucous myomas: a multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(6):2073–2077.

4. AAGL Practice Report: practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of submucous leiomyomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(2):152–171.

5. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1215–1223.

6. Van Dongen H, Emanuel MH, Wolterbeek R, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Hysteroscopic morcellator for removal of intrauterine polyps and myomas: a randomized controlled pilot study among residents in training. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(4):466–471.

7. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K. The intra uterine morcellator: a new hysteroscopic operating technique to remove intrauterine polyps and myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(1):62–66.

8. Emanuel MH, Hart A, Wamsteker K, Lammes F. An analysis of fluid loss during transcervical resection of submucous myomas. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(5):881–886.

9. Taskin O, Sadik S, Onoglu A, et al. Role of endometrial suppression on the frequency of intrauterine adhesions after resectoscopic surgery. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):351.

10. Propst AM, Liberman RF, Harlow BL, Ginsburg ES. Complications of hysteroscopic surgery: predicting patients at risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(4):517–520.

11. Perino A, Chianchiano N, Petronio M, Cittadini E. Role of leuprolide acetate depot in hysteroscopic surgery: a controlled study. Fertil Steril. 1993;59(3):507–510.

12. Mencaglia L, Tantini C. GnRH agonist analogs and hysteroscopic resection of myomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;43(3):285–288.

13. Hobo R, Netsu S, Koyasu Y, Tsutsumi O. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest caused by intramyometrial injection of vasopressin during a laparoscopically assisted myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 2):484–486.

14. Munro MD, Storz K, Abbott JA, et al; AAGL. AAGL Practice Report: practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):137–148.

Why is traditional open myomectomy acceptable if power morcellation isn’t?

Why is traditional open myomectomy acceptable if power morcellation isn’t?

The actions taken by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and medical device companies to limit use of power morcellation have effectively led to a halt in the use of minimally invasive surgery for removal of large uterine fibroids. This would seem to leave open laparotomy as the only viable choice for the conservative removal of these benign tumors in women who choose to retain their uterus for personal, cultural, or childbearing reasons. Or does it?

Any open myomectomy of an intramural or subserosal myoma involves an incision into the uterine serosa and muscularis, thus exposing the surface of the tumor to the peritoneal environment. The mass is then grasped with penetrating instruments and manipulated free of its myometrial attachments with other instruments such as forceps, scissors, and electrocautery devices. Suction instruments are freely employed over the operative field. The gloved digits of the surgeon are frequently used to bluntly dissect the tumor from the surrounding myometrial bed.

Because of the desire to maximize future fertility potential by minimizing adhesions, frequent irrigation is considered by most reproductive surgeons to be a necessary part of good surgical technique. Irrigation hydrates the tissues and carries away blood, but it can be counted on to disperse countless cells from the exposed surface of the tumor. After resection, the tumor is removed from the operative field and handed off, usually to the gloved hand of an assistant who will be handling all of the tools that are used from that point forward. If an abscess is a “dirty case” from the standpoint of the spread of infection, then any myomectomy is a potentially “dirty case” from the standpoint of the spread of neoplasia. Given the fundamental nature of this procedure, there seems to be no way to do a “clean” myomectomy.

Since any form of myomectomy involves at least as much manipulation of the tumor mass as morcellation, it should be at least as likely as morcellation to spread aberrant cells. An inadvertent exposure of the unprotected surface of a leiomyosarcoma at the time of a traditional open myomectomy is not different in any essential way from the exposure of the surface of the same tumor at the time of a myomectomy followed by any type of morcellation.

It is logical then that if morcellation can be proscribed by regulation and litigation, myomectomy itself will be proscribed on the exact same lines of reasoning.

Despite the widespread use of either abdominal or minimally invasive myomectomy over the last 75 years, disseminated uterine leiomyosarcoma is now and always has been a rare disease. This fact has always been accounted for in our risk assessments of leiomyoma surgeries. In addition, there is no scientific evidence that power morcellation, nonpowered morcellation, or abdominal myomectomy without morcellation has ever been causative in the spread of even one patient’s leiomyosarcoma. Leiomyosarcoma is by definition capable of disseminating by itself.

No medical authority would recommend total hysterectomy for every patient with any myoma, based on the possibility that any individual patient might be harboring a uterine cancer that can spread. This is, however, the exact evolutionary endpoint of the reasoning of the FDA and our legal system. The device companies are to be the deep pockets of the morcellation lawsuits and physicians will be the deep pockets of future myomectomy lawsuits. Gynecologists have always considered risk/reward factors in decisions regarding myomectomy and morcellation. We have an obligation to defend the reproductive rights of our patients. Lawyers, regulators, and even the corporations that dominate the medical device market are motivated by other concerns.

The practice of modern medicine aggressively challenges clinical decision-making based solely on anecdotal evidence. It has done so for well over a century now. It is one of the few standards that still unites good doctors under the battered and tattered umbrella of our professionalism. Our challenge as modern physicians is to stand fast against our new regulatory masters (as well as their former and future law partners) with their grave misunderstandings of the very character of gynecologic decision-making.

Michael C. Doody, MD, PhD

Knoxville, Tennessee

Awesome video!

I tried this technique as outlined in the video—totally awesome! It worked really well! Thanks to the surgeons who came up with it!

Ravindhra Mamilla, MD

Thief River Falls, Minnesota

Additional clarification would be appreciated

According to Dr. Kaunitz’s summary of the findings of Huh and colleagues,1 the population group included women with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) or high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) (ie, anything above atypical cells of undetermined significance [ASCUS]), along with women who tested positive for human papillomavirus (HPV) 16/18, regardless of cytology.

It would have been useful to have the LSIL and HSIL populations (independent or dependent of HPV status) broken down into subgroups.

The expert commentary does not indicate whether the 2.7% of biopsy-proven cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 and CIN 3 were predominantly confined to women with HSIL or equally prevalent in the LSIL population.

Without this information, I am not convinced that LSIL requires a random biopsy when colposcopy is adequate and normal, regardless of HPV status.

Jonathan Kew

Maitland, New South Wales, Australia

Reference

1. Huh WK, Sideri M, Stoler M, Zhang G, Feldman R, Behrens CM. Relevance of random biopsy at the transformation zone when colposcopy is negative. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):670–678.

Are we reverting to past practices?

For someone who has done colposcopy for about 35 years, I find the conclusions of Huh and colleagues nonsensical. If the squamocolumnar junction is visible and an endocervical curettage is done, this is adequate. Performing random biopsies takes us back to the days before we had the colposcope. I was there, and I’m not proud of how we handled abnormal Pap results.

Another issue: If you find severe dysplasia on random biopsy in a 40-year-old woman, how and what do you treat? Is this a case of treating the lab and not the patient? Or is this a case of inadequately trained gynecologists and/or pathologists?

Anton Strocel, MD

Grand Blanc, Michigan

Dr. Kaunitz responds

I thank Dr. Kew and Dr. Strocel for their interest in this commentary on the value of random biopsies during colposcopy when lesions are not visualized. Dr. Kew is correct that the authors did not separate findings in women with low-grade versus high-grade intraepithelial cytology. Dr. Strocel refers to the value of clinical experience when performing colposcopy. Both the current article by Huh and colleagues,1 as well an earlier high-quality report by Gage and colleagues,2 point out that, even in skilled hands, colposcopy is not as sensitive in detecting CIN as we have believed in the past. These reports present convincing evidence that, regardless of clinical experience, when no lesion is seen at the time of colposcopy, performing one or two random biopsies substantially increases diagnostic yield of clinically actionable (CIN 2 or worse) disease.

References

1. Huh WK, Sideri M, Stoler M, Zhang G, Feldman R, Behrens CM. Relevance of random biopsy at the transformation zone when colposcopy is negative. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):670–678.

2. Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):264–272.

Why not encourage soy intake?

Thanks for an interesting discussion on conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene (CE/BZA; Duavee). I note that:

- CE/BZA is manufactured by Pfizer

- Dr. JoAnn Pinkerton, who is interviewed by Anne Moore, DNP, APN, is affiliated with Pfizer, and

- CE/BZA costs $120 per month.

Since menopausal symptoms are caused by the decreased production of ovarian estradiol, why not prescribe estradiol 0.5–1 mg, which costs only $4 monthly?

Another point to consider: Over several decades of providing care to ethnically diverse women, my observation is that Japanese/Korean and Latina women report far fewer hot flushes than their white sisters.

I believe that it is because of their soy and yam intake. I personally eat about 0.25 lb of tofu per week. It can be diced for salad or soup or served with soy sauce, ginger, and bonito (fish) flakes. It can also be crushed and mixed with lean ground beef, pork, chicken, or turkey to make lean, healthy meatloaf.

Tofu is rich in phytoestrogens, lowers cholesterol, and promotes local soy farmers—a win-win situation.

Yasuo Ishida, MD

St. Louis, Missouri

‡‡Dr. Barbieri responds

Dr. Ishida raises an important issue of managing conflicts of interest in medical publications. Dr. Ishida notes that, in the past, Dr. Pinkerton was supported by Pfizer, the company that manufactures (CE/BZA, Duavee). Dr. Ishida also points out that, in a recent OBG Management article, Dr. Pinkerton provided her clinical perspective on the use of CE/BZA in practice.

Often, with a new medication, the physicians with the most expertise in using it have helped with key clinical trials. The results of these trials provide the basis for FDA approval of the medication. Prior to FDA approval of a drug, only experts involved in the clinical trial have first-hand experience with the new treatment.

Dr. Pinkerton is an internationally respected expert in the field and provided a balanced overview of CE/BZA and how it might be used in practice. Dr. Pinkerton disclosed that she personally receives no current support from Pfizer, but that she was supported by Pfizer years ago.

This potential conflict of interest was reported in the article.

Dr. Pinkerton responds