User login

Adding Immunoglobulin to HBV Vaccine No Help

Major Finding: The addition of hepatitis B immunoglobulin to hepatitis B prophylaxis with the recombinant HBV vaccine does not confer additional protection to newborns of chronically infected mothers.

Data Source: A randomized controlled trial of 222 infants born to mothers who tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Disclosures: Dr. Sarin and Dr. Pande reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – The recombinant hepatitis B vaccine confers as much protection when given alone as it does when given together with hepatitis B immunoglobulin to newborns of chronically infected mothers, but neither regimen is optimally effective, a study has shown.

The randomized controlled trial assessed the hepatitis B virus (HBV) status of 222 infants born to mothers who tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). The rate of protection observed in infants who received only the vaccine was statistically similar to that of infants who received the vaccine plus hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG).

A total of 39% of the vaccine-only group and 41% of the combination group remained infection free at a minimum of 18 weeks after birth, Dr. Shiv K. Sarin reported at the meeting noting that nearly half of the babies in both groups developed occult HBV infections.

The current standard of care for preventing HBV infection in babies born to mothers who are HBsAg positive is the recombinant hepatitis B virus vaccine plus HBIG; however, previous studies have suggested the possibility that the vaccine alone may be as effective as the combination therapy, said Dr. Sarin of the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences in New Delhi.

To test this hypothesis, Dr. Sarin, along with lead investigator Dr. Chandana Pande, a research associate at G.B. Pant Hospital in New Delhi, and colleagues randomized the newborns of 222 women who screened positive for HBsAg during their prenatal care to receive the 0.5-mL recombinant HBV vaccine at birth, 6 weeks, 10 weeks, and 14 weeks, either alone (116 infants) or with 0.5 mL intramuscular HBIG (106 infants). Mothers on antiviral therapy and those with coinfections were excluded from the investigation, he said.

All of the babies were assessed at a minimum of 18 weeks for HBsAg, HBV-DNA, and antibodies to HBsAg (anti-HBs). The study's primary end point was freedom from overt or occult HBV infection with adequate immune response, defined as anti-HBs titers of at least 10 IU/mL, Dr. Sarin said in a poster presentation.

Babies with overt HBV infection were those whose blood specimens tested positive for HBsAg by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, whereas babies with occult infection were negative for HBsAg but positive for HBV-DNA by polymerase chain reaction testing, he said. Babies with no infection but whose anti-HBs titers were less than 10 IU/mL were categorized as having a poor immune response.

At 18 weeks after birth, there were no significant differences between the combination therapy group and monotherapy group with respect to the number of babies meeting the study's primary end point, Dr. Sarin reported. Specifically, 43 babies in the combination group and 45 in the vaccine-only group remained free of overt or occult HBV infection with adequate immune response.

Of the babies not meeting the primary end point, 9 had overt HBV infection, including 2 in the combination group and 7 in the vaccine-only group, and 106 developed occult HBV infection, including 52 in the combination group and 54 in the vaccine-only group, Dr. Sarin said. Neither of these differences attained statistical significance, nor did the between-group difference in the number of infants demonstrating a poor immune response, he said.

Major Finding: The addition of hepatitis B immunoglobulin to hepatitis B prophylaxis with the recombinant HBV vaccine does not confer additional protection to newborns of chronically infected mothers.

Data Source: A randomized controlled trial of 222 infants born to mothers who tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Disclosures: Dr. Sarin and Dr. Pande reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – The recombinant hepatitis B vaccine confers as much protection when given alone as it does when given together with hepatitis B immunoglobulin to newborns of chronically infected mothers, but neither regimen is optimally effective, a study has shown.

The randomized controlled trial assessed the hepatitis B virus (HBV) status of 222 infants born to mothers who tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). The rate of protection observed in infants who received only the vaccine was statistically similar to that of infants who received the vaccine plus hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG).

A total of 39% of the vaccine-only group and 41% of the combination group remained infection free at a minimum of 18 weeks after birth, Dr. Shiv K. Sarin reported at the meeting noting that nearly half of the babies in both groups developed occult HBV infections.

The current standard of care for preventing HBV infection in babies born to mothers who are HBsAg positive is the recombinant hepatitis B virus vaccine plus HBIG; however, previous studies have suggested the possibility that the vaccine alone may be as effective as the combination therapy, said Dr. Sarin of the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences in New Delhi.

To test this hypothesis, Dr. Sarin, along with lead investigator Dr. Chandana Pande, a research associate at G.B. Pant Hospital in New Delhi, and colleagues randomized the newborns of 222 women who screened positive for HBsAg during their prenatal care to receive the 0.5-mL recombinant HBV vaccine at birth, 6 weeks, 10 weeks, and 14 weeks, either alone (116 infants) or with 0.5 mL intramuscular HBIG (106 infants). Mothers on antiviral therapy and those with coinfections were excluded from the investigation, he said.

All of the babies were assessed at a minimum of 18 weeks for HBsAg, HBV-DNA, and antibodies to HBsAg (anti-HBs). The study's primary end point was freedom from overt or occult HBV infection with adequate immune response, defined as anti-HBs titers of at least 10 IU/mL, Dr. Sarin said in a poster presentation.

Babies with overt HBV infection were those whose blood specimens tested positive for HBsAg by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, whereas babies with occult infection were negative for HBsAg but positive for HBV-DNA by polymerase chain reaction testing, he said. Babies with no infection but whose anti-HBs titers were less than 10 IU/mL were categorized as having a poor immune response.

At 18 weeks after birth, there were no significant differences between the combination therapy group and monotherapy group with respect to the number of babies meeting the study's primary end point, Dr. Sarin reported. Specifically, 43 babies in the combination group and 45 in the vaccine-only group remained free of overt or occult HBV infection with adequate immune response.

Of the babies not meeting the primary end point, 9 had overt HBV infection, including 2 in the combination group and 7 in the vaccine-only group, and 106 developed occult HBV infection, including 52 in the combination group and 54 in the vaccine-only group, Dr. Sarin said. Neither of these differences attained statistical significance, nor did the between-group difference in the number of infants demonstrating a poor immune response, he said.

Major Finding: The addition of hepatitis B immunoglobulin to hepatitis B prophylaxis with the recombinant HBV vaccine does not confer additional protection to newborns of chronically infected mothers.

Data Source: A randomized controlled trial of 222 infants born to mothers who tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Disclosures: Dr. Sarin and Dr. Pande reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – The recombinant hepatitis B vaccine confers as much protection when given alone as it does when given together with hepatitis B immunoglobulin to newborns of chronically infected mothers, but neither regimen is optimally effective, a study has shown.

The randomized controlled trial assessed the hepatitis B virus (HBV) status of 222 infants born to mothers who tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). The rate of protection observed in infants who received only the vaccine was statistically similar to that of infants who received the vaccine plus hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG).

A total of 39% of the vaccine-only group and 41% of the combination group remained infection free at a minimum of 18 weeks after birth, Dr. Shiv K. Sarin reported at the meeting noting that nearly half of the babies in both groups developed occult HBV infections.

The current standard of care for preventing HBV infection in babies born to mothers who are HBsAg positive is the recombinant hepatitis B virus vaccine plus HBIG; however, previous studies have suggested the possibility that the vaccine alone may be as effective as the combination therapy, said Dr. Sarin of the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences in New Delhi.

To test this hypothesis, Dr. Sarin, along with lead investigator Dr. Chandana Pande, a research associate at G.B. Pant Hospital in New Delhi, and colleagues randomized the newborns of 222 women who screened positive for HBsAg during their prenatal care to receive the 0.5-mL recombinant HBV vaccine at birth, 6 weeks, 10 weeks, and 14 weeks, either alone (116 infants) or with 0.5 mL intramuscular HBIG (106 infants). Mothers on antiviral therapy and those with coinfections were excluded from the investigation, he said.

All of the babies were assessed at a minimum of 18 weeks for HBsAg, HBV-DNA, and antibodies to HBsAg (anti-HBs). The study's primary end point was freedom from overt or occult HBV infection with adequate immune response, defined as anti-HBs titers of at least 10 IU/mL, Dr. Sarin said in a poster presentation.

Babies with overt HBV infection were those whose blood specimens tested positive for HBsAg by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, whereas babies with occult infection were negative for HBsAg but positive for HBV-DNA by polymerase chain reaction testing, he said. Babies with no infection but whose anti-HBs titers were less than 10 IU/mL were categorized as having a poor immune response.

At 18 weeks after birth, there were no significant differences between the combination therapy group and monotherapy group with respect to the number of babies meeting the study's primary end point, Dr. Sarin reported. Specifically, 43 babies in the combination group and 45 in the vaccine-only group remained free of overt or occult HBV infection with adequate immune response.

Of the babies not meeting the primary end point, 9 had overt HBV infection, including 2 in the combination group and 7 in the vaccine-only group, and 106 developed occult HBV infection, including 52 in the combination group and 54 in the vaccine-only group, Dr. Sarin said. Neither of these differences attained statistical significance, nor did the between-group difference in the number of infants demonstrating a poor immune response, he said.

From the Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

Birth Rate for U.S. Teens Falls to Lowest Level

The birth rate for U.S. teens aged 15-19 years fell to the lowest level since recording began in 1940, according to new data for 2009.

The 2009 teen birth rate was 39.1 births per 1,000 teens, down 6% from the 2008 rate of 41.5 births per 1,000, according to the report by the CDC National Center for Health Statistics. The 2009 rate was 37% lower than in 1991, the peak year for teen births. The CDC's annual report is based on virtually 100% of vital records collected in the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories. The report is available at www.cdc.gov/nchs

Overall fertility also fell in 2009 to 66.7 births per 1,000 women aged 15-44 years, compared with 68.6 per 1,000 women in 2008. The CDC's preliminary estimate of births in 2009 was 4,131,019, 3% less than 2008. Early data through June 2010 suggest that the decline in fertility has continued, according to the report.

Fertility rates increased in only one age group: women aged 40-44 years. In that group, the 2009 rate was 10.1 births per 1,000 women, up 3% from the 2008 figure and the highest rate since 1967.

The rate of preterm births declined for the third straight year, to 12.2% of all births in 2009. The rate of cesarean deliveries rose to a record high of 32.9% in 2009, up from 32.3% in 2008.

The low birth weight rate remained unchanged at about 8.2% between 2008 and 2009.

The CDC also reported the total fertility rate (TFR) – an estimate of the number of births that a hypothetical group of 1,000 women would have over their lifetimes, based on the age-specific rates of a particular year. The TFR for 2009 was 2,007.5, down 4% from the rate in 2008. This is the largest decline in TFR since 1973. The 2008 and 2009 rates were both below the replacement rate of 2,100 births per 1,000 women. The U.S. TFR was below replacement for every year between 1972 and 2005 and above replacement in 2006 and 2007.

The birth rate for U.S. teens aged 15-19 years fell to the lowest level since recording began in 1940, according to new data for 2009.

The 2009 teen birth rate was 39.1 births per 1,000 teens, down 6% from the 2008 rate of 41.5 births per 1,000, according to the report by the CDC National Center for Health Statistics. The 2009 rate was 37% lower than in 1991, the peak year for teen births. The CDC's annual report is based on virtually 100% of vital records collected in the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories. The report is available at www.cdc.gov/nchs

Overall fertility also fell in 2009 to 66.7 births per 1,000 women aged 15-44 years, compared with 68.6 per 1,000 women in 2008. The CDC's preliminary estimate of births in 2009 was 4,131,019, 3% less than 2008. Early data through June 2010 suggest that the decline in fertility has continued, according to the report.

Fertility rates increased in only one age group: women aged 40-44 years. In that group, the 2009 rate was 10.1 births per 1,000 women, up 3% from the 2008 figure and the highest rate since 1967.

The rate of preterm births declined for the third straight year, to 12.2% of all births in 2009. The rate of cesarean deliveries rose to a record high of 32.9% in 2009, up from 32.3% in 2008.

The low birth weight rate remained unchanged at about 8.2% between 2008 and 2009.

The CDC also reported the total fertility rate (TFR) – an estimate of the number of births that a hypothetical group of 1,000 women would have over their lifetimes, based on the age-specific rates of a particular year. The TFR for 2009 was 2,007.5, down 4% from the rate in 2008. This is the largest decline in TFR since 1973. The 2008 and 2009 rates were both below the replacement rate of 2,100 births per 1,000 women. The U.S. TFR was below replacement for every year between 1972 and 2005 and above replacement in 2006 and 2007.

The birth rate for U.S. teens aged 15-19 years fell to the lowest level since recording began in 1940, according to new data for 2009.

The 2009 teen birth rate was 39.1 births per 1,000 teens, down 6% from the 2008 rate of 41.5 births per 1,000, according to the report by the CDC National Center for Health Statistics. The 2009 rate was 37% lower than in 1991, the peak year for teen births. The CDC's annual report is based on virtually 100% of vital records collected in the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories. The report is available at www.cdc.gov/nchs

Overall fertility also fell in 2009 to 66.7 births per 1,000 women aged 15-44 years, compared with 68.6 per 1,000 women in 2008. The CDC's preliminary estimate of births in 2009 was 4,131,019, 3% less than 2008. Early data through June 2010 suggest that the decline in fertility has continued, according to the report.

Fertility rates increased in only one age group: women aged 40-44 years. In that group, the 2009 rate was 10.1 births per 1,000 women, up 3% from the 2008 figure and the highest rate since 1967.

The rate of preterm births declined for the third straight year, to 12.2% of all births in 2009. The rate of cesarean deliveries rose to a record high of 32.9% in 2009, up from 32.3% in 2008.

The low birth weight rate remained unchanged at about 8.2% between 2008 and 2009.

The CDC also reported the total fertility rate (TFR) – an estimate of the number of births that a hypothetical group of 1,000 women would have over their lifetimes, based on the age-specific rates of a particular year. The TFR for 2009 was 2,007.5, down 4% from the rate in 2008. This is the largest decline in TFR since 1973. The 2008 and 2009 rates were both below the replacement rate of 2,100 births per 1,000 women. The U.S. TFR was below replacement for every year between 1972 and 2005 and above replacement in 2006 and 2007.

From the Centers For Disease Control and Prevention

If Possible, Delay Delivery Until 39 Weeks

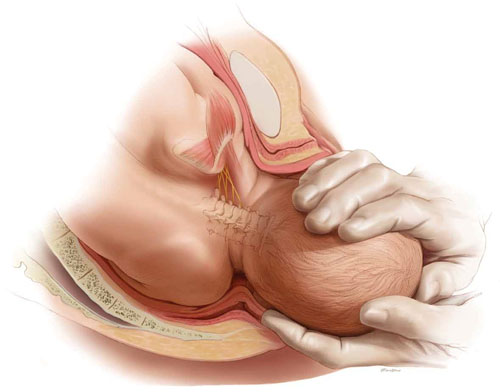

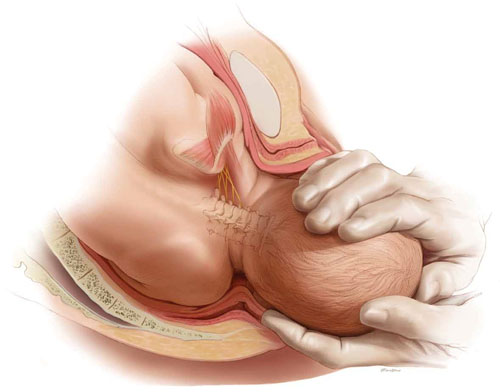

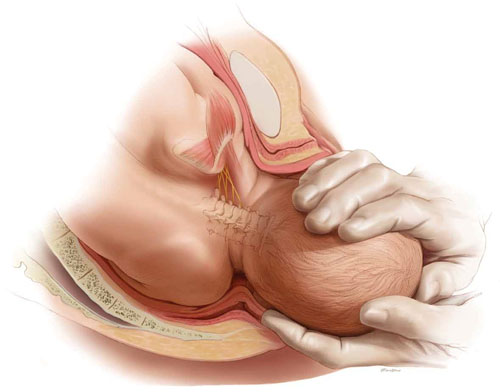

Neonates who are delivered at 36-38 weeks' gestation after fetal lung maturity is confirmed have nearly double the risk of adverse outcomes, compared with neonates delivered at 39 or 40 weeks, a large retrospective cohort study has shown.

The mean birth weight in 459 neonates with confirmed lung maturity who were delivered at 36-38 weeks' gestation was 3,017 g, compared with 3,362 g in 13,339 neonates delivered at 39-40 weeks. The risk of a composite outcome including death, adverse respiratory outcomes, hypoglycemia, treated hyperbilirubinemia, generalized seizures, necrotizing enterocolitis, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, periventricular leukomalacia, and suspected or proven sepsis was 6.1% in those in the 36- to 38-week group, compared with 2.5% in the 39- to 40-week group, Dr. Elizabeth Bates of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and her colleagues reported.

Early delivery remained a significant risk factor for the composite outcome after investigators adjusted for maternal age, ethnicity, parity, neonatal sex, intended mode of delivery, and any medical complication – including diabetes and hypertension. Early delivery was also a significant risk factor for several individual outcomes, including respiratory distress syndrome (adjusted odds ratio, 7.6); treated hyperbilirubinemia (AOR, 11.2); and hypoglycemia (AOR, 5.8), the investigators found (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010; 116:1288-95).

The incidence of the primary composite outcome generally decreased with increasing gestational age, they noted (9.2% incidence at 36 weeks, 3.2% at 37 weeks, 5.2% at 38 weeks, and 2.5% at 39-40 weeks).

Patients included in the study were women with a singleton pregnancy receiving prenatal care and giving birth at a single center from January 1999 to December 2008. Among those who were delivered at 36-38 weeks following documentation of fetal lung maturity, 42.5% had completed 36 weeks, 40.7% had completed 37 weeks, and only 16.8% had completed 38 weeks. Of those who were delivered at 38-40 weeks, 56.2% had completed 39 weeks, and 43.8% had completed 40 weeks. The mean gestational age was 37.1 weeks in those delivered at 36-38 weeks and was 39.8 weeks in those who delivered at 38-40 weeks.

The study findings are concerning, because fetal lung maturity is known to reduce the risk of respiratory morbidity, and confirmation of fetal lung maturity is “a recognized exception to longstanding recommendations against elective delivery before 39 weeks' gestation,” Dr. Bates and her associates noted.

Also, despite existing recommendations to the contrary, one-third of elective cesarean deliveries in one large study were performed before 39 weeks, they said.

Taken together, the findings in the current study “are consistent with relative immaturity at 36-38 weeks (regardless of lung maturity), compared with 39-40 weeks, and lower threshold for admission to the NICU and for invasive sepsis work-ups (suspected sepsis),” the investigators wrote.

They added that the findings should be considered in light of the study's limitations – including the retrospective study design and the related possibility of confounding, and the fact that the study does not fully address the risk of stillbirth associated with either delivery strategy studied. Nonetheless, they concluded that the findings suggest that “in the absence of ongoing concern about fetal death or maternal well-being if the pregnancy continued, delivery should be delayed until 39 weeks.”

The findings also suggest that purely elective fetal lung maturity testing and early delivery should be avoided, Dr. Bates and her associates noted.

One of the study authors, Dr. Alan T. N. Tita, was a Women's Reproductive Health Research Advanced Scholar at the University of Alabama at Birmingham at the time of the study and received funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. No relevant financial disclosures were reported by the other authors.

View on The News

Reconsider What Constitutes Term Birth

“This paper further advances our understanding of the optimal conditions for delivering a baby free of major health complications. Specifically, it confirms findings from a number of previous studies suggesting that babies born before 39 weeks' gestation have a significantly increased risk of complications, including respiratory distress syndrome, even if their lungs appear to be fully mature via biomarker testing,” Dr. E. Albert Reece said in an interview.

More importantly, he said, the study suggests that current definitions of what constitute a term birth may need to be reconsidered.

“Indeed, currently babies born between 37 and 42 completed weeks of pregnancy are considered full term, whereas babies born before 37 weeks of pregnancy are completed are considered preterm. However, if the results of this study are to be believed, they suggest that babies born before 39 weeks of gestation might be considered preterm as well.”

This may mean that the definition for term needs to be revised upward to 39-42 weeks, he added.

“It also means that physicians should try to do everything possible to keep from delivering women until they've reached 39 weeks of gestation, unless there are valid reasons for delivery to protect the health of the mother,” he said.

Vitals

DR. REECE is the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He is also professor in the departments of obstetrics and gynecology, medicine, and biochemistry and molecular biology. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Neonates who are delivered at 36-38 weeks' gestation after fetal lung maturity is confirmed have nearly double the risk of adverse outcomes, compared with neonates delivered at 39 or 40 weeks, a large retrospective cohort study has shown.

The mean birth weight in 459 neonates with confirmed lung maturity who were delivered at 36-38 weeks' gestation was 3,017 g, compared with 3,362 g in 13,339 neonates delivered at 39-40 weeks. The risk of a composite outcome including death, adverse respiratory outcomes, hypoglycemia, treated hyperbilirubinemia, generalized seizures, necrotizing enterocolitis, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, periventricular leukomalacia, and suspected or proven sepsis was 6.1% in those in the 36- to 38-week group, compared with 2.5% in the 39- to 40-week group, Dr. Elizabeth Bates of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and her colleagues reported.

Early delivery remained a significant risk factor for the composite outcome after investigators adjusted for maternal age, ethnicity, parity, neonatal sex, intended mode of delivery, and any medical complication – including diabetes and hypertension. Early delivery was also a significant risk factor for several individual outcomes, including respiratory distress syndrome (adjusted odds ratio, 7.6); treated hyperbilirubinemia (AOR, 11.2); and hypoglycemia (AOR, 5.8), the investigators found (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010; 116:1288-95).

The incidence of the primary composite outcome generally decreased with increasing gestational age, they noted (9.2% incidence at 36 weeks, 3.2% at 37 weeks, 5.2% at 38 weeks, and 2.5% at 39-40 weeks).

Patients included in the study were women with a singleton pregnancy receiving prenatal care and giving birth at a single center from January 1999 to December 2008. Among those who were delivered at 36-38 weeks following documentation of fetal lung maturity, 42.5% had completed 36 weeks, 40.7% had completed 37 weeks, and only 16.8% had completed 38 weeks. Of those who were delivered at 38-40 weeks, 56.2% had completed 39 weeks, and 43.8% had completed 40 weeks. The mean gestational age was 37.1 weeks in those delivered at 36-38 weeks and was 39.8 weeks in those who delivered at 38-40 weeks.

The study findings are concerning, because fetal lung maturity is known to reduce the risk of respiratory morbidity, and confirmation of fetal lung maturity is “a recognized exception to longstanding recommendations against elective delivery before 39 weeks' gestation,” Dr. Bates and her associates noted.

Also, despite existing recommendations to the contrary, one-third of elective cesarean deliveries in one large study were performed before 39 weeks, they said.

Taken together, the findings in the current study “are consistent with relative immaturity at 36-38 weeks (regardless of lung maturity), compared with 39-40 weeks, and lower threshold for admission to the NICU and for invasive sepsis work-ups (suspected sepsis),” the investigators wrote.

They added that the findings should be considered in light of the study's limitations – including the retrospective study design and the related possibility of confounding, and the fact that the study does not fully address the risk of stillbirth associated with either delivery strategy studied. Nonetheless, they concluded that the findings suggest that “in the absence of ongoing concern about fetal death or maternal well-being if the pregnancy continued, delivery should be delayed until 39 weeks.”

The findings also suggest that purely elective fetal lung maturity testing and early delivery should be avoided, Dr. Bates and her associates noted.

One of the study authors, Dr. Alan T. N. Tita, was a Women's Reproductive Health Research Advanced Scholar at the University of Alabama at Birmingham at the time of the study and received funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. No relevant financial disclosures were reported by the other authors.

View on The News

Reconsider What Constitutes Term Birth

“This paper further advances our understanding of the optimal conditions for delivering a baby free of major health complications. Specifically, it confirms findings from a number of previous studies suggesting that babies born before 39 weeks' gestation have a significantly increased risk of complications, including respiratory distress syndrome, even if their lungs appear to be fully mature via biomarker testing,” Dr. E. Albert Reece said in an interview.

More importantly, he said, the study suggests that current definitions of what constitute a term birth may need to be reconsidered.

“Indeed, currently babies born between 37 and 42 completed weeks of pregnancy are considered full term, whereas babies born before 37 weeks of pregnancy are completed are considered preterm. However, if the results of this study are to be believed, they suggest that babies born before 39 weeks of gestation might be considered preterm as well.”

This may mean that the definition for term needs to be revised upward to 39-42 weeks, he added.

“It also means that physicians should try to do everything possible to keep from delivering women until they've reached 39 weeks of gestation, unless there are valid reasons for delivery to protect the health of the mother,” he said.

Vitals

DR. REECE is the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He is also professor in the departments of obstetrics and gynecology, medicine, and biochemistry and molecular biology. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Neonates who are delivered at 36-38 weeks' gestation after fetal lung maturity is confirmed have nearly double the risk of adverse outcomes, compared with neonates delivered at 39 or 40 weeks, a large retrospective cohort study has shown.

The mean birth weight in 459 neonates with confirmed lung maturity who were delivered at 36-38 weeks' gestation was 3,017 g, compared with 3,362 g in 13,339 neonates delivered at 39-40 weeks. The risk of a composite outcome including death, adverse respiratory outcomes, hypoglycemia, treated hyperbilirubinemia, generalized seizures, necrotizing enterocolitis, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, periventricular leukomalacia, and suspected or proven sepsis was 6.1% in those in the 36- to 38-week group, compared with 2.5% in the 39- to 40-week group, Dr. Elizabeth Bates of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and her colleagues reported.

Early delivery remained a significant risk factor for the composite outcome after investigators adjusted for maternal age, ethnicity, parity, neonatal sex, intended mode of delivery, and any medical complication – including diabetes and hypertension. Early delivery was also a significant risk factor for several individual outcomes, including respiratory distress syndrome (adjusted odds ratio, 7.6); treated hyperbilirubinemia (AOR, 11.2); and hypoglycemia (AOR, 5.8), the investigators found (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010; 116:1288-95).

The incidence of the primary composite outcome generally decreased with increasing gestational age, they noted (9.2% incidence at 36 weeks, 3.2% at 37 weeks, 5.2% at 38 weeks, and 2.5% at 39-40 weeks).

Patients included in the study were women with a singleton pregnancy receiving prenatal care and giving birth at a single center from January 1999 to December 2008. Among those who were delivered at 36-38 weeks following documentation of fetal lung maturity, 42.5% had completed 36 weeks, 40.7% had completed 37 weeks, and only 16.8% had completed 38 weeks. Of those who were delivered at 38-40 weeks, 56.2% had completed 39 weeks, and 43.8% had completed 40 weeks. The mean gestational age was 37.1 weeks in those delivered at 36-38 weeks and was 39.8 weeks in those who delivered at 38-40 weeks.

The study findings are concerning, because fetal lung maturity is known to reduce the risk of respiratory morbidity, and confirmation of fetal lung maturity is “a recognized exception to longstanding recommendations against elective delivery before 39 weeks' gestation,” Dr. Bates and her associates noted.

Also, despite existing recommendations to the contrary, one-third of elective cesarean deliveries in one large study were performed before 39 weeks, they said.

Taken together, the findings in the current study “are consistent with relative immaturity at 36-38 weeks (regardless of lung maturity), compared with 39-40 weeks, and lower threshold for admission to the NICU and for invasive sepsis work-ups (suspected sepsis),” the investigators wrote.

They added that the findings should be considered in light of the study's limitations – including the retrospective study design and the related possibility of confounding, and the fact that the study does not fully address the risk of stillbirth associated with either delivery strategy studied. Nonetheless, they concluded that the findings suggest that “in the absence of ongoing concern about fetal death or maternal well-being if the pregnancy continued, delivery should be delayed until 39 weeks.”

The findings also suggest that purely elective fetal lung maturity testing and early delivery should be avoided, Dr. Bates and her associates noted.

One of the study authors, Dr. Alan T. N. Tita, was a Women's Reproductive Health Research Advanced Scholar at the University of Alabama at Birmingham at the time of the study and received funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. No relevant financial disclosures were reported by the other authors.

View on The News

Reconsider What Constitutes Term Birth

“This paper further advances our understanding of the optimal conditions for delivering a baby free of major health complications. Specifically, it confirms findings from a number of previous studies suggesting that babies born before 39 weeks' gestation have a significantly increased risk of complications, including respiratory distress syndrome, even if their lungs appear to be fully mature via biomarker testing,” Dr. E. Albert Reece said in an interview.

More importantly, he said, the study suggests that current definitions of what constitute a term birth may need to be reconsidered.

“Indeed, currently babies born between 37 and 42 completed weeks of pregnancy are considered full term, whereas babies born before 37 weeks of pregnancy are completed are considered preterm. However, if the results of this study are to be believed, they suggest that babies born before 39 weeks of gestation might be considered preterm as well.”

This may mean that the definition for term needs to be revised upward to 39-42 weeks, he added.

“It also means that physicians should try to do everything possible to keep from delivering women until they've reached 39 weeks of gestation, unless there are valid reasons for delivery to protect the health of the mother,” he said.

Vitals

DR. REECE is the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He is also professor in the departments of obstetrics and gynecology, medicine, and biochemistry and molecular biology. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

From Obstetrics & Gynecology

UPDATE ON OBSTETRICS

- How to manage a short cervix to lower the risk of preterm delivery

Joseph R. Wax, MD (May 2010) - When is VBAC appropriate?

Aviva Lee-Parritz, MD (July 2010) - What can be safer than having a baby in the USA? (Commentary)

Louis L. Weinstein, MD (May 2010)

From an evolutionary standpoint, not much has changed in pregnancy and childbirth. From a clinical perspective, however, flux is a constant. Three issues, in particular, have seen notable development over the past year:

- optimal timing of elective delivery

- screening for thrombophilias in women who experience recurrent pregnancy loss, fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, or placental abruption

- use of magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection.

Of course, in the specialties of obstetrics and perinatal medicine, research continues in a variety of other subject areas, as well. Simulation training, diagnosis and management of gestational diabetes, and rescue steroid treatment are three examples. Other issues being explored include the use of progesterone to prevent prematurity, the use of ultrasonography to measure cervical length, and the safety of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. The three areas highlighted here are not the only ones “ready for prime time,” but they are areas of considerable interest and debate.

We have a tradition in obstetrics of not embracing change too quickly. We learned this lesson through our experience with diethylstilbestrol (DES) and thalidomide, and we must continue to use caution whenever new technologies or management approaches are proposed.

30 weeks is the rule, provided delivery is truly elective

Tita ATN, Landon MB, Spong CY, et al. Timing of elective cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):111–120.

When it comes to elective delivery, no one would argue against the wisdom of continuing pregnancy until at least 39 weeks’ gestation in the absence of complications. But what data form the basis of this wisdom, and when might it be prudent to consider earlier delivery?

In a widely publicized study, Tita and colleagues concluded that elective repeat cesarean delivery before 39 weeks of gestation (i.e., 37 through 38-6/7 weeks) is associated with a higher rate of neonatal respiratory distress and other adverse neonatal outcomes than is delivery at 39 to 40 weeks. Note, however, that the primary outcome of this study was a composite. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with some caution.

In their report, Tita and coworkers acknowledged that the transient and predominantly minor complications associated with delivery before 39 weeks must be weighed against the risk of fetal death inherent in delaying delivery through 38 full weeks—and an accompanying editorial made the same point.1 Stillbirth occurs at a rate of 1 case for every 1,000 births in the 37- to 39-week gestational age range—a rate that may be higher than the risks associated with delivery. Even so, the risk of stillbirth at 37 to 39 weeks is very small, and that risk is unlikely to be lowered through routine antenatal fetal testing. We should also remember that the risks of neonatal respiratory distress, transient tachypnea, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and even cerebral palsy2 may be increased with delivery at 37 to 38 weeks, or at 42 weeks or later, compared with delivery at 40 weeks.

All truly elective deliveries should occur at or after 39 weeks of gestation. However, when indicated, earlier delivery is acceptable—even essential—if we are to minimize maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in high-risk circumstances, such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, placenta previa, fetal growth restriction, and other conditions.

Investigations are under way to determine whether there is a role for routine betamethasone administration (regardless of indication or gestational age) in the absence of labor before 39 weeks. Until those data come in, we should continue to follow current practice guidelines for antenatal maternal administration of betamethasone—namely, a single course given between 24 and 34 weeks in women who have an elevated risk of preterm delivery.

Population-based screening for thrombophilias is not recommended

Silver RM, Zhao Y, Spong CY, et al, for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (NICHD MFMU) Network. Prothrombin gene G20210A mutation and obstetric complications. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):14–20.

Said JM, Higgins JR, Moses EK, et al. Inherited thrombophilia polymorphisms and pregnancy outcomes in nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):5–13.

Since the mid-1990s, screening for thrombophilias has been recommended in the evaluation of a variety of adverse reproductive outcomes, including, but not limited to:

- recurrent pregnancy loss

- unexplained stillbirth

- placental abruption

- preeclampsia

- fetal growth restriction.

When a thrombophilia is detected in these settings, the practitioner faces a dilemma—namely, what to do when the mother is otherwise healthy and asymptomatic. All too often the finding of a thrombophilia leads to the initiation of some anticoagulation regimen, ranging from low-dose aspirin all the way to therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin.

Over the past year, several studies and expert opinions have been published that recast the role of thrombophilia screening in obstetric practice.

Writing for the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network, Silver and colleagues concluded that the prothrombin (PT) gene mutation G20210A was not associated with pregnancy loss, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, or placental abruption in a low-risk, prospective cohort.

Said and coworkers reached a similar conclusion. In a blinded, prospective cohort study, they screened for the following mutations in 2,034 healthy nulliparous women before 22 weeks’ gestation:

- factor V Leiden mutation

- PT gene G20210A mutation

- methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase enzyme (MTHFR) C677T

- MTHFR A1298C

- thrombomodulin polymorphism.

The majority of asymptomatic women who carried an inherited thrombophilia polymorphism had a successful pregnancy outcome. In fact, homozygosity of the MTHFR A1298C mutation was found to be protective.

Population-based screening for thrombophilias is not recommended. In fact, some authors have advised against screening for thrombophilias even in the setting of a thrombotic event, suggesting it has limited utility.3

The main reason to screen for a thrombophilia at this time is to explore idiopathic thrombosis or a strong family history of the same. There is no need to screen for thrombophilias when the patient has a history of pregnancy loss, placental abruption, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction.

If you give magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection, adhere to a protocol

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 455: Magnesium sulfate before anticipated preterm birth for neuroprotection. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(3):669–671.

Magnesium sulfate has a long and glorious history in obstetrics, having been used to prevent eclampsia, to treat preterm uterine contractions, and now, potentially, to reduce the incidence of central nervous system damage among prematurely delivered infants.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is most commonly associated with prematurity and intrauterine fetal infection. Only in the past two decades has there been a shift away from assigning the cause of most cases of CP to intrapartum events. Nevertheless, CP remains an important concern among patients and providers, and research continues to find ways to prevent CP or minimize its effects.

Numerous large trials have explored the use of magnesium sulfate to prevent CP in preterm infants. Although their findings have not been as definitive as researchers had hoped, some data do suggest that magnesium sulfate has a protective effect.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) urge caution in regard to the use of magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection. The SMFM points out that the reported benefits of magnesium sulfate in this setting have been derived largely from secondary analyses. The SMFM recommends that, if magnesium is used at all, it should be administered according to one of the published protocols (three are cited in the ACOG opinion).

The SMFM goes on to warn against choosing magnesium sulfate as a tocolytic solely because of its possible neuroprotective effects.

In a Committee Opinion published last year, ACOG was a bit more definite. “The Committee on Obstetric Practice and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recognize that none of the individual studies found a benefit with regard to their primary outcome,” the opinion states. “However, the available evidence suggests that magnesium sulfate given before anticipated early preterm birth reduces the risk of cerebral palsy in surviving infants. Physicians electing to use magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection should develop specific guidelines regarding inclusion criteria, treatment regimens, concurrent tocolysis, and monitoring in concordance with one of the larger trials.”

Recent editorials have cautioned against using magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection until more data become available,4 or have left it up to the individual practitioners (or institution) to decide whether it is advisable.5

The use of magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection when preterm delivery seems likely requires additional research. For now, this practice should be governed strictly by protocol. And it should not be viewed as “standard of care” by our legal colleagues.

When administering magnesium sulfate, avoid giving a cumulative total in excess of 50 g, as this amount may increase the risk of pediatric death.6

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Greene MF. Making small risks even smaller. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):183-184.

2. Moster D, Wilcox AJ, Vollset SE, Markestad T, Lie RT. Cerebral palsy among term and postterm births. JAMA. 2010;304(9):976-982.

3. Scifres CM, Macones GA. The utility of thrombophilia testing in pregnant women with thrombosis; fact or fiction? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(4):344.e1–7.-

4. Stanley FJ, Crowther C. Antenatal magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection before preterm birth? N Engl J Med. 2008;359(9):962-964.

5. Macones GA. MgSO4 for CP prevention: too good to be true? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):589.-

6. Mittendorf R, Covert R, Boman J, et al. Is tocolytic magnesium sulfate associated with increased total paediatric mortality? Lancet. 1997;350(9090):1517-1518.

- How to manage a short cervix to lower the risk of preterm delivery

Joseph R. Wax, MD (May 2010) - When is VBAC appropriate?

Aviva Lee-Parritz, MD (July 2010) - What can be safer than having a baby in the USA? (Commentary)

Louis L. Weinstein, MD (May 2010)

From an evolutionary standpoint, not much has changed in pregnancy and childbirth. From a clinical perspective, however, flux is a constant. Three issues, in particular, have seen notable development over the past year:

- optimal timing of elective delivery

- screening for thrombophilias in women who experience recurrent pregnancy loss, fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, or placental abruption

- use of magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection.

Of course, in the specialties of obstetrics and perinatal medicine, research continues in a variety of other subject areas, as well. Simulation training, diagnosis and management of gestational diabetes, and rescue steroid treatment are three examples. Other issues being explored include the use of progesterone to prevent prematurity, the use of ultrasonography to measure cervical length, and the safety of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. The three areas highlighted here are not the only ones “ready for prime time,” but they are areas of considerable interest and debate.

We have a tradition in obstetrics of not embracing change too quickly. We learned this lesson through our experience with diethylstilbestrol (DES) and thalidomide, and we must continue to use caution whenever new technologies or management approaches are proposed.

30 weeks is the rule, provided delivery is truly elective

Tita ATN, Landon MB, Spong CY, et al. Timing of elective cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):111–120.

When it comes to elective delivery, no one would argue against the wisdom of continuing pregnancy until at least 39 weeks’ gestation in the absence of complications. But what data form the basis of this wisdom, and when might it be prudent to consider earlier delivery?

In a widely publicized study, Tita and colleagues concluded that elective repeat cesarean delivery before 39 weeks of gestation (i.e., 37 through 38-6/7 weeks) is associated with a higher rate of neonatal respiratory distress and other adverse neonatal outcomes than is delivery at 39 to 40 weeks. Note, however, that the primary outcome of this study was a composite. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with some caution.

In their report, Tita and coworkers acknowledged that the transient and predominantly minor complications associated with delivery before 39 weeks must be weighed against the risk of fetal death inherent in delaying delivery through 38 full weeks—and an accompanying editorial made the same point.1 Stillbirth occurs at a rate of 1 case for every 1,000 births in the 37- to 39-week gestational age range—a rate that may be higher than the risks associated with delivery. Even so, the risk of stillbirth at 37 to 39 weeks is very small, and that risk is unlikely to be lowered through routine antenatal fetal testing. We should also remember that the risks of neonatal respiratory distress, transient tachypnea, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and even cerebral palsy2 may be increased with delivery at 37 to 38 weeks, or at 42 weeks or later, compared with delivery at 40 weeks.

All truly elective deliveries should occur at or after 39 weeks of gestation. However, when indicated, earlier delivery is acceptable—even essential—if we are to minimize maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in high-risk circumstances, such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, placenta previa, fetal growth restriction, and other conditions.

Investigations are under way to determine whether there is a role for routine betamethasone administration (regardless of indication or gestational age) in the absence of labor before 39 weeks. Until those data come in, we should continue to follow current practice guidelines for antenatal maternal administration of betamethasone—namely, a single course given between 24 and 34 weeks in women who have an elevated risk of preterm delivery.

Population-based screening for thrombophilias is not recommended

Silver RM, Zhao Y, Spong CY, et al, for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (NICHD MFMU) Network. Prothrombin gene G20210A mutation and obstetric complications. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):14–20.

Said JM, Higgins JR, Moses EK, et al. Inherited thrombophilia polymorphisms and pregnancy outcomes in nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):5–13.

Since the mid-1990s, screening for thrombophilias has been recommended in the evaluation of a variety of adverse reproductive outcomes, including, but not limited to:

- recurrent pregnancy loss

- unexplained stillbirth

- placental abruption

- preeclampsia

- fetal growth restriction.

When a thrombophilia is detected in these settings, the practitioner faces a dilemma—namely, what to do when the mother is otherwise healthy and asymptomatic. All too often the finding of a thrombophilia leads to the initiation of some anticoagulation regimen, ranging from low-dose aspirin all the way to therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin.

Over the past year, several studies and expert opinions have been published that recast the role of thrombophilia screening in obstetric practice.

Writing for the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network, Silver and colleagues concluded that the prothrombin (PT) gene mutation G20210A was not associated with pregnancy loss, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, or placental abruption in a low-risk, prospective cohort.

Said and coworkers reached a similar conclusion. In a blinded, prospective cohort study, they screened for the following mutations in 2,034 healthy nulliparous women before 22 weeks’ gestation:

- factor V Leiden mutation

- PT gene G20210A mutation

- methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase enzyme (MTHFR) C677T

- MTHFR A1298C

- thrombomodulin polymorphism.

The majority of asymptomatic women who carried an inherited thrombophilia polymorphism had a successful pregnancy outcome. In fact, homozygosity of the MTHFR A1298C mutation was found to be protective.

Population-based screening for thrombophilias is not recommended. In fact, some authors have advised against screening for thrombophilias even in the setting of a thrombotic event, suggesting it has limited utility.3

The main reason to screen for a thrombophilia at this time is to explore idiopathic thrombosis or a strong family history of the same. There is no need to screen for thrombophilias when the patient has a history of pregnancy loss, placental abruption, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction.

If you give magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection, adhere to a protocol

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 455: Magnesium sulfate before anticipated preterm birth for neuroprotection. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(3):669–671.

Magnesium sulfate has a long and glorious history in obstetrics, having been used to prevent eclampsia, to treat preterm uterine contractions, and now, potentially, to reduce the incidence of central nervous system damage among prematurely delivered infants.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is most commonly associated with prematurity and intrauterine fetal infection. Only in the past two decades has there been a shift away from assigning the cause of most cases of CP to intrapartum events. Nevertheless, CP remains an important concern among patients and providers, and research continues to find ways to prevent CP or minimize its effects.

Numerous large trials have explored the use of magnesium sulfate to prevent CP in preterm infants. Although their findings have not been as definitive as researchers had hoped, some data do suggest that magnesium sulfate has a protective effect.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) urge caution in regard to the use of magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection. The SMFM points out that the reported benefits of magnesium sulfate in this setting have been derived largely from secondary analyses. The SMFM recommends that, if magnesium is used at all, it should be administered according to one of the published protocols (three are cited in the ACOG opinion).

The SMFM goes on to warn against choosing magnesium sulfate as a tocolytic solely because of its possible neuroprotective effects.

In a Committee Opinion published last year, ACOG was a bit more definite. “The Committee on Obstetric Practice and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recognize that none of the individual studies found a benefit with regard to their primary outcome,” the opinion states. “However, the available evidence suggests that magnesium sulfate given before anticipated early preterm birth reduces the risk of cerebral palsy in surviving infants. Physicians electing to use magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection should develop specific guidelines regarding inclusion criteria, treatment regimens, concurrent tocolysis, and monitoring in concordance with one of the larger trials.”

Recent editorials have cautioned against using magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection until more data become available,4 or have left it up to the individual practitioners (or institution) to decide whether it is advisable.5

The use of magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection when preterm delivery seems likely requires additional research. For now, this practice should be governed strictly by protocol. And it should not be viewed as “standard of care” by our legal colleagues.

When administering magnesium sulfate, avoid giving a cumulative total in excess of 50 g, as this amount may increase the risk of pediatric death.6

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- How to manage a short cervix to lower the risk of preterm delivery

Joseph R. Wax, MD (May 2010) - When is VBAC appropriate?

Aviva Lee-Parritz, MD (July 2010) - What can be safer than having a baby in the USA? (Commentary)

Louis L. Weinstein, MD (May 2010)

From an evolutionary standpoint, not much has changed in pregnancy and childbirth. From a clinical perspective, however, flux is a constant. Three issues, in particular, have seen notable development over the past year:

- optimal timing of elective delivery

- screening for thrombophilias in women who experience recurrent pregnancy loss, fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, or placental abruption

- use of magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection.

Of course, in the specialties of obstetrics and perinatal medicine, research continues in a variety of other subject areas, as well. Simulation training, diagnosis and management of gestational diabetes, and rescue steroid treatment are three examples. Other issues being explored include the use of progesterone to prevent prematurity, the use of ultrasonography to measure cervical length, and the safety of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. The three areas highlighted here are not the only ones “ready for prime time,” but they are areas of considerable interest and debate.

We have a tradition in obstetrics of not embracing change too quickly. We learned this lesson through our experience with diethylstilbestrol (DES) and thalidomide, and we must continue to use caution whenever new technologies or management approaches are proposed.

30 weeks is the rule, provided delivery is truly elective

Tita ATN, Landon MB, Spong CY, et al. Timing of elective cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):111–120.

When it comes to elective delivery, no one would argue against the wisdom of continuing pregnancy until at least 39 weeks’ gestation in the absence of complications. But what data form the basis of this wisdom, and when might it be prudent to consider earlier delivery?

In a widely publicized study, Tita and colleagues concluded that elective repeat cesarean delivery before 39 weeks of gestation (i.e., 37 through 38-6/7 weeks) is associated with a higher rate of neonatal respiratory distress and other adverse neonatal outcomes than is delivery at 39 to 40 weeks. Note, however, that the primary outcome of this study was a composite. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with some caution.

In their report, Tita and coworkers acknowledged that the transient and predominantly minor complications associated with delivery before 39 weeks must be weighed against the risk of fetal death inherent in delaying delivery through 38 full weeks—and an accompanying editorial made the same point.1 Stillbirth occurs at a rate of 1 case for every 1,000 births in the 37- to 39-week gestational age range—a rate that may be higher than the risks associated with delivery. Even so, the risk of stillbirth at 37 to 39 weeks is very small, and that risk is unlikely to be lowered through routine antenatal fetal testing. We should also remember that the risks of neonatal respiratory distress, transient tachypnea, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and even cerebral palsy2 may be increased with delivery at 37 to 38 weeks, or at 42 weeks or later, compared with delivery at 40 weeks.

All truly elective deliveries should occur at or after 39 weeks of gestation. However, when indicated, earlier delivery is acceptable—even essential—if we are to minimize maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in high-risk circumstances, such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, placenta previa, fetal growth restriction, and other conditions.

Investigations are under way to determine whether there is a role for routine betamethasone administration (regardless of indication or gestational age) in the absence of labor before 39 weeks. Until those data come in, we should continue to follow current practice guidelines for antenatal maternal administration of betamethasone—namely, a single course given between 24 and 34 weeks in women who have an elevated risk of preterm delivery.

Population-based screening for thrombophilias is not recommended

Silver RM, Zhao Y, Spong CY, et al, for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (NICHD MFMU) Network. Prothrombin gene G20210A mutation and obstetric complications. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):14–20.

Said JM, Higgins JR, Moses EK, et al. Inherited thrombophilia polymorphisms and pregnancy outcomes in nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):5–13.

Since the mid-1990s, screening for thrombophilias has been recommended in the evaluation of a variety of adverse reproductive outcomes, including, but not limited to:

- recurrent pregnancy loss

- unexplained stillbirth

- placental abruption

- preeclampsia

- fetal growth restriction.

When a thrombophilia is detected in these settings, the practitioner faces a dilemma—namely, what to do when the mother is otherwise healthy and asymptomatic. All too often the finding of a thrombophilia leads to the initiation of some anticoagulation regimen, ranging from low-dose aspirin all the way to therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin.

Over the past year, several studies and expert opinions have been published that recast the role of thrombophilia screening in obstetric practice.

Writing for the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network, Silver and colleagues concluded that the prothrombin (PT) gene mutation G20210A was not associated with pregnancy loss, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, or placental abruption in a low-risk, prospective cohort.

Said and coworkers reached a similar conclusion. In a blinded, prospective cohort study, they screened for the following mutations in 2,034 healthy nulliparous women before 22 weeks’ gestation:

- factor V Leiden mutation

- PT gene G20210A mutation

- methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase enzyme (MTHFR) C677T

- MTHFR A1298C

- thrombomodulin polymorphism.

The majority of asymptomatic women who carried an inherited thrombophilia polymorphism had a successful pregnancy outcome. In fact, homozygosity of the MTHFR A1298C mutation was found to be protective.

Population-based screening for thrombophilias is not recommended. In fact, some authors have advised against screening for thrombophilias even in the setting of a thrombotic event, suggesting it has limited utility.3

The main reason to screen for a thrombophilia at this time is to explore idiopathic thrombosis or a strong family history of the same. There is no need to screen for thrombophilias when the patient has a history of pregnancy loss, placental abruption, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction.

If you give magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection, adhere to a protocol

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 455: Magnesium sulfate before anticipated preterm birth for neuroprotection. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(3):669–671.

Magnesium sulfate has a long and glorious history in obstetrics, having been used to prevent eclampsia, to treat preterm uterine contractions, and now, potentially, to reduce the incidence of central nervous system damage among prematurely delivered infants.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is most commonly associated with prematurity and intrauterine fetal infection. Only in the past two decades has there been a shift away from assigning the cause of most cases of CP to intrapartum events. Nevertheless, CP remains an important concern among patients and providers, and research continues to find ways to prevent CP or minimize its effects.

Numerous large trials have explored the use of magnesium sulfate to prevent CP in preterm infants. Although their findings have not been as definitive as researchers had hoped, some data do suggest that magnesium sulfate has a protective effect.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) urge caution in regard to the use of magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection. The SMFM points out that the reported benefits of magnesium sulfate in this setting have been derived largely from secondary analyses. The SMFM recommends that, if magnesium is used at all, it should be administered according to one of the published protocols (three are cited in the ACOG opinion).

The SMFM goes on to warn against choosing magnesium sulfate as a tocolytic solely because of its possible neuroprotective effects.

In a Committee Opinion published last year, ACOG was a bit more definite. “The Committee on Obstetric Practice and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recognize that none of the individual studies found a benefit with regard to their primary outcome,” the opinion states. “However, the available evidence suggests that magnesium sulfate given before anticipated early preterm birth reduces the risk of cerebral palsy in surviving infants. Physicians electing to use magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection should develop specific guidelines regarding inclusion criteria, treatment regimens, concurrent tocolysis, and monitoring in concordance with one of the larger trials.”

Recent editorials have cautioned against using magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection until more data become available,4 or have left it up to the individual practitioners (or institution) to decide whether it is advisable.5

The use of magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection when preterm delivery seems likely requires additional research. For now, this practice should be governed strictly by protocol. And it should not be viewed as “standard of care” by our legal colleagues.

When administering magnesium sulfate, avoid giving a cumulative total in excess of 50 g, as this amount may increase the risk of pediatric death.6

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Greene MF. Making small risks even smaller. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):183-184.

2. Moster D, Wilcox AJ, Vollset SE, Markestad T, Lie RT. Cerebral palsy among term and postterm births. JAMA. 2010;304(9):976-982.

3. Scifres CM, Macones GA. The utility of thrombophilia testing in pregnant women with thrombosis; fact or fiction? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(4):344.e1–7.-

4. Stanley FJ, Crowther C. Antenatal magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection before preterm birth? N Engl J Med. 2008;359(9):962-964.

5. Macones GA. MgSO4 for CP prevention: too good to be true? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):589.-

6. Mittendorf R, Covert R, Boman J, et al. Is tocolytic magnesium sulfate associated with increased total paediatric mortality? Lancet. 1997;350(9090):1517-1518.

1. Greene MF. Making small risks even smaller. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):183-184.

2. Moster D, Wilcox AJ, Vollset SE, Markestad T, Lie RT. Cerebral palsy among term and postterm births. JAMA. 2010;304(9):976-982.

3. Scifres CM, Macones GA. The utility of thrombophilia testing in pregnant women with thrombosis; fact or fiction? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(4):344.e1–7.-

4. Stanley FJ, Crowther C. Antenatal magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection before preterm birth? N Engl J Med. 2008;359(9):962-964.

5. Macones GA. MgSO4 for CP prevention: too good to be true? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):589.-

6. Mittendorf R, Covert R, Boman J, et al. Is tocolytic magnesium sulfate associated with increased total paediatric mortality? Lancet. 1997;350(9090):1517-1518.

More strategies to avoid malpractice hazards on labor and delivery

Sound strategies to avoid malpractice hazards on labor and delivery

Martin L. Gimovsky, MD, and Alexis C. Gimovsky, MD

CASE 1: Pregestational diabetes, large baby, birth injury

A 31-year-old gravida 1 is admitted to labor and delivery. She is at 39-5/7 weeks’ gestation, dated by last menstrual period and early sonogram. The woman is a pregestational diabetic and uses insulin to control her blood glucose level.

Three weeks before admission, ultrasonography (US) revealed an estimated fetal weight of 3,650 g—at the 71st percentile for gestational age.

After an unremarkable course of labor, delivery is complicated by severe shoulder dystocia. The newborn has a birth weight of 4,985 g and sustains an Erb’s palsy-type injury. The mother develops a rectovaginal fistula after a fourth-degree tear.

In the first part of this article, we discussed how an allegation of malpractice can arise because of an unexpected event or outcome for a mother in your care, or her baby, apart from any specific clinical action you undertook. We offered an example: Counseling that you provide about options for prenatal care that falls short of full understanding by the patient.

In this article, we enter the realm of the hands-on practice of medicine and discuss causation: namely, the actions of a physician, in the course of managing labor and delivering a baby, that put that physician at risk of a charge of malpractice because the medical care 1) is inconsistent with current medical practice and thus 2) harmed mother or newborn.

Let’s return to the opening case above and discuss key considerations for the physician. Three more cases follow that, with analysis and recommendations.

Considerations in CASE 1

- A woman who has pregestational diabetes should receive ongoing counseling about the risks of fetal anomalies, macrosomia, and problems in the neonatal period. Be certain that she understands that these risks can be ameliorated, but not eliminated, with careful blood glucose control.

- The fetus of a diabetic gravida develops a relative decrease in the ratio of head circumference-to-abdominal circumference that predisposes it to shoulder dystocia. Cesarean delivery can decrease, but not eliminate, the risk of traumatic birth injury in a diabetic mother. (Of course, cesarean delivery will, on its own, substantially increase the risk of maternal morbidity—including at any subsequent cesarean delivery.)

What do they mean? terms and concepts intended to bolster your work and protect you

It’s not easy to define what constitutes “best care” in a given clinical circumstance. Generalizations are useful, but they may possess an inherent weakness: “Best practices,” “evidence-based care,” “standardization of care,” and “uniformity of care” usually apply more usefully to populations than individuals.

Such concepts derive from broader applications in economics, politics, and science. They are useful to define a reasonable spectrum of anticipated practices, and they certainly have an expanding role in the care of patients and in medical education (TABLE). Clinical guidelines serve as strategies that may be very helpful to the clinician. All of us understand and implement appropriate care in the great majority of clinical scenarios, but none of us are, or can be, expert in all situations. Referencing and using guidelines can fill a need for a functional starting point when expertise is lacking or falls short.

Best practices result from evidence-directed decision-making. This concept logically yields a desirable uniformity of practice. Although we all believe that our experience is our best teacher, we may best serve patients if we sample knowledge and wisdom from controlled clinical trials and from the experiences of others. What is accepted local practice must also be considered important when you devise a plan of care.1,2

A selected glossary of clinical care guidelines

| Term | What does it mean? |

|---|---|

| “Best practice” | A process or activity that is believed to be more effective at delivering a particular outcome than any other when applied to a particular condition or circumstance. The idea? With proper processes, checks, and testing, a desired outcome can be delivered with fewer problems and unforeseen complications than otherwise possible.5 |

| “Evidence-based care” | The best available process or activity arising from both 1) individual expertise and 2) best external evidence derived from systematic research.6 |

| “Standard of care” | A clinical practice to maximize success and minimize risk, applied to professional decision-making.7 |

| “Uniformity of practice” | Use of systematic, literature-based research findings to develop an approach that is efficacious and safe; that maximizes benefit; and that minimizes risk.8 |

Consider the management of breech presentation that is recognized at the 36th week antepartum visit: Discussion with the patient should include 1) reference to concerns with congenital anomalies and genetic syndromes, 2) in-utero growth and development, and 3) the delivery process. The management algorithm may include external cephalic version, elective cesarean delivery before onset of labor, or cesarean delivery after onset of labor. Each approach has advocates—based on expert opinion clinical trials.

Management options may vary from institution to institution, however, because of limited availability of certain services—such as the expertise required for a trial of external cephalic version, the availability of on-site cesarean delivery capabilities, and patient and clinician preferences.

Uniformity of care, based on best practices, can therefore simplify the care process and decrease the risk that may be associated with individual experience-based management. Adhering to a uniform practice augments the clinician’s knowledge and allows for enhanced nursing and therapeutic efficiency.

The greatest benefit of using an evidence-based, widely accepted approach, however, is the potential to diminish poor practice and consequent malpractice exposure for both clinicians and the hospital.

Note: Although your adherence to clinical guidelines, best practices, and uniformity of care ought to be consistent with established standards of care, don’t automatically consider any deviation a lapse or failing because it’s understood and accepted that some local variability exists in practice.

Prelude to birth: triage and admission Triage. Most women in labor arrive at the hospital or birthing center to an area set aside for labor and delivery triage. There, 1) recording of the chief complaint and vital signs and 2) completion of a brief history and physical generate a call to the clinician.

The record produced in triage should be scrutinized carefully for accuracy. Clarify, in as timely a manner as possible, any errors in:

- timing (possibly because of different clocks set to different times)

- the precise capture of the chief complaint

- reporting difficulty or ease in reaching the responsible clinician.

Whether these records are electronic or paper, an addendum marked with the time is always acceptable. Never attempt to correct a record! Always utilize a late entry or addendum.

Admission. After the patient is admitted, she generally undergoes an admission protocol, specific to the hospital, regarding her situation. This includes:

- the history

- special requests

- any previously agreed-on plan of care

- any problems that have developed since her last prenatal visit.

This protocol is generally completed by a nurse, resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant.

Hospitals generally request input from the attending physician on the specifics of the admission, based on those hospital protocols. There may be some room to individualize the admission process to labor and delivery.

4 pillars of care during labor

In general, labor is defined as progressive dilation of the cervix. Several parameters serve as guidelines regarding adequate progress through the various stages of labor.

Fetal monitoring. Continuous evaluation of the fetus during labor is a routine part of intrapartum care. Recording and observing the FHR tracing is an accepted—and expected—practice. Documentation of the FHR in the medical record is specifically required, and should include both the physician’s and nursing notes.

Anesthesia care. The patient’s preference and the availability of options allows for several accepted practices regarding anesthesia and analgesia during L & D. Does she want epidural anesthesia during labor, for example? Intravenous narcotics? Her choice is an important facet of your provision of care.

However, such choice requires the patient to give consent and to understand the risk-benefit equation. Documentation by nursing of the patient’s consent and understanding should be complete, including discussion and administration. Anesthesia staff should be clear, complete, and legible in making a record.

Neonatal care. If logistics permit, a member of the pediatrics service should be routinely available to see the newborn at delivery. The patient should view the pediatrician and obstetrician as partners working as a team for the benefit of the mother and her family. This can enhance the patient’s understanding and confidence about the well being of her baby.

Documentation. Although deficient documentation does not, itself, lead to a finding of malpractice, appropriate documentation plays an important role in demonstrating that clinical practices have addressed issues about both allegation and causation of potential adverse outcomes.

We cannot overemphasize that nursing documentation should complement and be consistent with notes made by the physician. That said, nursing notes are not a substitute for the physician’s notes. Practices that integrate the written comments of nursing and physician into a single set of progress notes facilitate this complementary interaction.

3 more clinical scenarios

CASE 2: Admitted at term with contractions

The initial exam determines that this 21-year-old gravida 1 is 2/80/-1. Re-examination in 3 hours finds her at 3-4/80/0.

She requests pain relief and states that she wants epidural anesthesia.

Evaluation 2 hours later suggests secondary arrest of dilation. Oxytocin is begun.

Soon after, late decelerations are observed on the FHR monitor.

Use of exogenous oxytocin in L & D is a double-edged sword: The drug can enhance the safety and efficacy of labor and delivery for mother and fetus, but using it in an unregulated manner (in terms of its indication and administration) can subject both to increased risk.

In fact, it is fair to say that the most widespread and potentially dangerous intervention during labor is the administration of oxytocin. Many expert opinions, guidelines, and strategies have been put forward about intrapartum use of oxytocin. These include consideration of:

- indications

- dosage (including the maximum)

- interval

- fetal response

- ultimately, the availability of a physician during administration to manage any problem that arises.

Considerations in CASE 2

- Always clearly indicate the reason for using oxytocin: Is this an induction? Or an augmentation? Was there evidence of fetal well-being, or non-reassurance, before oxytocin was administered? Certainly, there are circumstances in which either fetal status or non-progression of labor (or both) are an indication for oxytocin. A clear, concise, and properly timed progress note is always appropriate under these circumstances.

- Discuss treatment with the patient. Does she understand why this therapy is being recommended? Does she agree to its use? And does she understand what the alternatives are?

- Verify that nursing has accurately charted this process. Ensure that the nursing staff’s notes are complete and are consistent with yours.