User login

Community Nursing Home Program Oversight: Can the VA Meet Increased Demand for Community-Based Care?

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Community Nursing Home (CNH) program provides 24-hour skilled nursing care for eligible veterans in public or private community-based facilities that have established a contract to care for veterans. Veteran eligibility is based on service-connected status and level of disability, covering the cost of care for veterans who need long-term care because of their service-connected disability or for veterans with disabilities rated at ≥ 70%.1 Between 2014 and 2018, the average daily census of veterans in CNHs increased by 26% and the percentage of funds obligated to this program increased by 49%.2 The VA projects that the number of veterans receiving care in a CNH program will increase by 80% between 2017 and 2037, corresponding to a 149% increase in CNH expenditures.2

CNH program oversight teams are mandated at each VA medical center (VAMC) to monitor care coordination within the CNH program. These teams include nurses and social workers (SWs) who perform regular on-site assessments to monitor the clinical, functional, and psychosocial needs of veterans. These assessments include a review of the electronic health record (EHR) and face-to-face contact with veterans and CNH staff, regardless of the purchasing authority (hospice, long-term care, short-term rehabilitation, respite care).3 These teams represent key stakeholders impacted by CNH program expansion.

While the CNH program has focused primarily on the provision of long-term care, the VA is now expanding to include short-term rehabilitation through Veteran Care Agreements.4 These agreements are authorized under the MISSION Act, designed to improve care for veterans.5 Veteran Care Agreements are expected to be less burdensome to execute than traditional contracts and will permit the VA to partner with more CNHs, as noted in a Congressional Research Service report regarding long-term care services for veterans.6 However, increasing the number of CNHs increases demands on oversight teams, particularly if the coordinators are compelled to perform monthly on-site visits to facilities required under current guidelines.3

The objective of this study was to describe the experiences of VA and CNH staff involved in care coordination and the oversight of veterans receiving CNH care amid Veteran Care Agreement implementation and in anticipation of CNH program expansion. The results are intended to inform expansion efforts within the CNH program.

METHODS

This study was a component of a larger research project examining VA-purchased CNH care; recruitment methods are available in previous publications describing this work.7 Participants provided written or verbal consent before video and phone interviews, respectively. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (Protocol #18-1186).

Video and phone interviews were conducted by 3 team members from October 2018 to March 2020 with CNH staff and VA CNH program oversight team members. Participant recruitment was paused from May to October 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and ambiguity about VA NH care purchasing policies following the passage of the VA MISSION Act.5 We used semistructured interview guides (eAppendix 1 for VA staff and eAppendix 2 for NH staff, available online at doi:10.12788/fp.0421). Recorded and transcribed interviews ranged from 15 to 90 minutes.

Two members of the research team analyzed transcripts using both deductive and inductive content analysis.8 The interview guide informed an a priori codebook, and in vivo codes were included as they emerged. We jointly coded 6 transcripts to reach a consensus on coding approaches and analyzed the remaining transcripts independently with frequent meetings to develop themes with a qualitative methodologist. All qualitative data were analyzed using ATLAS.ti software.

This was a retrospective observational study of veterans who received VA-paid care in CNHs during the 2019 fiscal year (10/1/2018-9/30/2019) using data from the enrollment, inpatient and outpatient encounters, and other care paid for by the VA in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. We linked Centers for Medicare and Medicaid monthly Nursing Home Compare reports and the Brown University Long Term Care: Facts on Care in the US (LTC FoCUS) annual files to identify facility addresses.9

Descriptive analyses of quantitative data were conducted in parallel with the qualitative findings.8 Distance from the contracting VAMC to CNH was calculated using the greater-circle formula to find the linear distance between geographic coordinates. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently, analyzed independently, and integrated into the interpretation of results.10

RESULTS

We conducted 36 interviews with VA and NH staff who were affiliated with 6 VAMCs and 17 CNHs. Four themes emerged concerning CNH oversight: (1) benefits of VA CNH team engagement/visits; (2) burden of VA CNH oversight; (3) burden of oversight limited the ability to contract with additional NHs; and (4) factors that ease the burden and facilitate successful oversight.

Benefits of Engagement/Visits

VA SWs and nurses visit each veteran every 30 to 45 days to review their health records, meet with them, and check in with NH staff. In addition, VA SWs and nurses coordinate each veteran’s care by working as liaisons between the VA and the NH to help NH staff problem solve veteran-related issues through care conferences. VA SWs and nurses act as extra advocates for veterans to make sure their needs are met. “This program definitely helps ensure that veterans are receiving higher quality care because if we see that they aren’t, then we do something about it,” a VA NH coordinator reported in an interview.

NH staff noted benefits to monthly VA staff visits, including having an additional person coordinating care and built-in VA liaisons. “It’s nice to have that extra set of eyes, people that you can care plan with,” an NH administrator shared. “It’s definitely a true partnership, and we have open and honest conversations so we can really provide a good service for our veterans.”

Distance & High Veteran Census Burdens

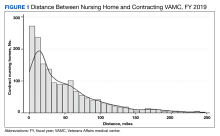

VA participants described oversight components as burdensome. Specifically, several VA participants mentioned that the charting they completed in the facility during each visit proved time consuming and onerous, particularly for distant NHs. To accommodate veterans’ preferences to receive care in a facility close to their homes and families, VAMCs contract with NHs that are geographically spread out. “We’re just all spread out… staff have issues driving 2 and a half hours just to review charts all day,” a VA CNH coordinator explained. In 2019, the mean distance between VAMC and NH was 48 miles, with half located > 32 miles from the VAMC. One-quarter of NHs were > 70 miles and 44% were located > 50 miles from the VAMC (Figure 1).

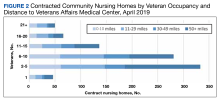

Participants highlighted how regular oversight visits were particularly time consuming at CNHs with a large contracted population. VA nurses and SWs spend multiple days and up to a week conducting oversight visits at facilities with large numbers of veterans. Another VA nurse highlighted how charting requirements resulted in several days of documentation outside of the NH visit for facilities with many contracted veteran residents. Multiple VA participants noted that having many veterans at an NH exacerbated the oversight burdens. In 2019, 252 (28%) of VA CNHs had > 10 contracted veterans and 1 facility had 34 veterans (Figure 2). VA participants perceived having too many veterans concentrated at 1 facility as potentially challenging for CNHs due to the complex care needs of veterans and the added need for care coordination with the VA. One VA NH coordinator noted that while some facilities were “adept at being able to handle higher numbers” of veterans, others were “overwhelmed.” Too many veterans at an NH, an SW explained, might lead the “facility to fail because we are such a cumbersome system.”

Oversight & Staffing Burden

While several participants described wanting to contract with more NHs to avoid overwhelming existing CNHs and to increase choice for veterans, they expressed concerns about their ability to provide oversight at more facilities due to limited staffing and oversight requirements. Across VAMCs, the median number of VA CNHs varied substantially (Figure 3). One VA participant with about 35 CNHs explained that while adding more NHs could create “more opportunities and options” for veterans, it needs to be balanced with the required oversight responsibilities. One VA nurse insisted that more staff were needed to meet current and future oversight needs. “We’re all getting stretched pretty thin, and just so we don’t drop the ball on things… I would like to see a little more staff if we’re gonna have a lot more nursing homes.”

Participants had concerns related to the VA MISSION Act and the possibility of more VA-paid NHs for rehabilitation or short-term care. Participants underscored the necessity for additional staff to account for the increased oversight burden or a reduction in oversight requirements. One SW felt that increasing the number of CNHs would increase the required oversight and the need for collaboration with NH staff, which would limit her ability to establish close and trusting working relationships with NH staff. Participants also described the challenges of meeting their current oversight requirements, which limited extra visits for acute issues and care conferences. This was attributed to a lack of adequate staffing in the VA CNH program, given the time-intensive nature of VA oversight requirements.

Easing Burden & Facilitating Oversight

Participants noted how obtaining remote access to veterans’ EHRs allowed them to conduct chart reviews before oversight visits. This permitted more time for interaction with veterans and CNH staff as well as coordinating care. While providing access to the VA EHR would not change the chart review component of VA oversight, some participants felt it might improve care coordination between VA and NH staff during monthly visits.

Participants felt they were able to build strong working relationships with facilities with more veterans due to frequent communication and collaboration. VA participants also noted that CNHs with larger veteran censuses were more likely to respond to VA concerns about care to maintain the business relationship and contract. To optimize strong working relationships and decrease the challenges of having too many veterans at a facility, some VA participants suggested that CNH programs create a local policy to recommend the number of veterans placed in a CNH.

Discussion

Participants interviewed for this study echoed findings from previous work that identified the importance of developing trusted working relationships with CNHs to care for veterans.11,12 However, interorganizational care coordination, a shortage of health care professionals, and resource demands associated with caring for veterans reported in other community care settings were also noted in our findings.12,13

Building upon prior recommendations related to community care of veterans, our analysis identified key areas that could improve CNH program oversight efficiency, including: (1) improving the interoperability of EHRs to facilitate coordination of care and oversight; (2) addressing inefficiencies associated with traveling to geographically dispersed CNHs; and (3) “right-sizing” the number of veterans residing in each CNH.

The interoperability of EHRs has been cited by multiple studies of VA community care programs as critical to reducing inefficiencies and allowing more in-person time with veterans and staff in care coordination, especially at rural locations.11-15 The Veterans Health Information Exchange Program is designed to optimize data sharing as veterans are increasingly referred to non-VA care through the MISSION Act. This program is organized around patient engagement, clinician adoption, partner engagement, and technological capabilities.16

Unfortunately, significant barriers exist for the VA CNH program within each of these information exchange domains. For example, patient engagement requires veteran consent for consumer-initiated exchange of medical information, which is not practical due to the high prevalence of cognitive impairment in NHs. Similarly, VA consent requirements prohibit EHR download and sharing with non-VA facilities like CNHs, limiting use. eHealth Exchange partnerships allow organizations caring for veterans to connect with the VA via networks that provide a common trust agreement and technical compliance testing. Unfortunately, in 2017, only 257 NHs in which veterans received care nationally were eHealth Exchange partners, which indicates that while NHs could partner in this information exchange, very few did.16

Finally, while the exchange is possible, it is not practical; most CNHs lack the staff that would be required to support data transfer on their technology platform into the appropriate translational gateways. Although remote access to EHRs in CNHs improved during the pandemic, the Veterans Health Information Exchange Program is not designed to facilitate interoperability of VA and CNH records and remains a significant barrier for this and many other VA community care programs.

The dispersal of veterans across CNHs that are > 50 miles from the nearest VAMC represents an additional area to improve program efficiency and meet growing demands for rural care. While recent field guidance to CNH oversight teams reduces the frequency of visits by VA CNH teams, the burden of driving to each facility is not likely to decrease as CNHs increasingly offer rehabilitation as a part of Veteran Care Agreements.17 Visits performed by telehealth or by trained local VA staff may represent alternatives.15

Finally, interview participants described the ideal range of the number of veterans in each CNH necessary to optimize efficiencies. Veterans who rely more heavily upon VA care tend to have more medical and mental health comorbidities than average Medicare beneficiaries.18,19 This was reflected in participants’ recommendation to have enough veterans to benefit from economies of scale but to also identify a limit when efficiencies are lost. Given that most CNHs cared for 8 to 15 veterans, facilities seem to have identified how best to match the resources available with veterans’ care needs. Based on these observations, new care networks that will be established because of the MISSION Act may benefit from establishing evidence-based policies that support flexibility in oversight frequency and either allow for remote oversight or consolidate the number of CNHs to improve efficiencies in care provision and oversight.20

Limitations

Limitations include the unique relationship between VA and CNH staff overseeing the quality of care provided to veterans in CNHs, which is not replicated in other models of care. Data collection was interrupted following the passage of the MISSION Act in 2018 until guidance on changes to practice resulting from the law were clarified in 2020. Interviews were also interrupted at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

The current quality of the CNH care oversight structure will require adaptation as demand for CNH care increases. While the VA CNH program is one of the longest-standing programs collaborating with non-VA community care partners, it is now only one of many following the MISSION Act. The success of this and other programs will depend on matching available CNH resources to the complex medical and psychological needs of veterans. At a time when strategies to ease the burden on NHs and VA CNH coordinators are desperately needed, Veterans Health Information Exchange capabilities need to improve. Evidence is needed to guide the scaling of the program to meet the needs of the rapidly expanding veteran population who are eligible for CNH care.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Amy Mochel of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center for project management support of this project.

1. Miller EA, Gadbois E, Gidmark S, Intrator O. Purchasing nursing home care within the Veterans Health Administration: lessons for nursing home recruitment, contracting, and oversight. J Health Admin Educ. 2015;32(2):165-197.

2. GAO. VA health care. Veterans’ use of long-term care is increasing, and VA faces challenges in meeting the demand. February 19, 2020. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-284.pdf

3. VHA Handbook 1143.2, VHA community nursing home oversight procedures. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. June 2004. https://www.vendorportal.ecms.va.gov/FBODocumentServer/DocumentServer.aspx?DocumentId=3740930&FileName=VA259-17-Q-0501-007.pdf

4. Community care: veteran care agreements. US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2022. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed September 7, 2023. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/providers/Veterans_Care_Agreements.asp

5. Massarweh NN, Itani KMF, Morris MS. The VA MISSION Act and the future of veterans’ access to quality health care. JAMA. 2020;324(4):343-344. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4505

6. Colello KJ, Panangala SV; Congressional Research Service. Long-term care services for veterans. February 14, 2017. Accessed September 7, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44697

7. Magid KH, Galenbeck E, Haverhals LM, et al. Purchasing high-quality community nursing home care: a will to work with VHA diminished by contracting burdens. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(11):1757-1764. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2022.03.007

8. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398-405. doi:10.1111/nhs.12048

9. Brown University. LTC Focus. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://ltcfocus.org/about

10. Zhang W, Creswell J. The use of “mixing” procedure of mixed methods in health services research. Med Care. 2013;51(8):e51-e57. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824642fd

11. Haverhals LM, Magid KH, Blanchard KN, Levy CR. Veterans Health Administration staff perceptions of overseeing care in community nursing homes during COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2022;8:23337214221080307. Published 2022 Feb 15. doi:10.1177/23337214221080307

12. Garvin LA, Pugatch M, Gurewich D, Pendergast JN, Miller CJ. Interorganizational care coordination of rural veterans by Veterans Affairs and community care programs: a systematic review. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 3):S259-S269. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001542

13. Schlosser J, Kollisch D, Johnson D, Perkins T, Olson A. VA-community dual care: veteran and clinician perspectives. J Community Health. 2020;45(4):795-802. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00795-y

14. Nevedal AL, Wong EP, Urech TH, Peppiatt JL, Sorie MR, Vashi AA. Veterans’ experiences with accessing community emergency care. Mil Med. 2023;188(1-2):e58-e64. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab196

15. Levenson SA. Smart case review: a model for successful remote medical direction and enhanced nursing home quality improvement. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(10):2212-2215.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2021.05.043

16. Donahue M, Bouhaddou O, Hsing N, et al. Veterans Health Information Exchange: successes and challenges of nationwide interoperability. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:385-394. Published 2018 Dec 5.

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Notice 2023-07. Community Nursing Home Program. September 5, 2023:1-4.

18. Helmer DA, Dwibedi N, Rowneki M, et al. Mental health conditions and hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions among veterans with diabetes. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2020;13(2):61-71.

19. Rosen AK, Wagner TH, Pettey WBP, et al. Differences in risk scores of veterans receiving community care purchased by the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(suppl 3):5438-5454. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13051

20. Mattocks KM, Kroll-Desrosiers A, Kinney R, Elwy AR, Cunningham KJ, Mengeling MA. Understanding VA’s use of and relationships with community care providers under the MISSION Act. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 3):S252-S258. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001545

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Community Nursing Home (CNH) program provides 24-hour skilled nursing care for eligible veterans in public or private community-based facilities that have established a contract to care for veterans. Veteran eligibility is based on service-connected status and level of disability, covering the cost of care for veterans who need long-term care because of their service-connected disability or for veterans with disabilities rated at ≥ 70%.1 Between 2014 and 2018, the average daily census of veterans in CNHs increased by 26% and the percentage of funds obligated to this program increased by 49%.2 The VA projects that the number of veterans receiving care in a CNH program will increase by 80% between 2017 and 2037, corresponding to a 149% increase in CNH expenditures.2

CNH program oversight teams are mandated at each VA medical center (VAMC) to monitor care coordination within the CNH program. These teams include nurses and social workers (SWs) who perform regular on-site assessments to monitor the clinical, functional, and psychosocial needs of veterans. These assessments include a review of the electronic health record (EHR) and face-to-face contact with veterans and CNH staff, regardless of the purchasing authority (hospice, long-term care, short-term rehabilitation, respite care).3 These teams represent key stakeholders impacted by CNH program expansion.

While the CNH program has focused primarily on the provision of long-term care, the VA is now expanding to include short-term rehabilitation through Veteran Care Agreements.4 These agreements are authorized under the MISSION Act, designed to improve care for veterans.5 Veteran Care Agreements are expected to be less burdensome to execute than traditional contracts and will permit the VA to partner with more CNHs, as noted in a Congressional Research Service report regarding long-term care services for veterans.6 However, increasing the number of CNHs increases demands on oversight teams, particularly if the coordinators are compelled to perform monthly on-site visits to facilities required under current guidelines.3

The objective of this study was to describe the experiences of VA and CNH staff involved in care coordination and the oversight of veterans receiving CNH care amid Veteran Care Agreement implementation and in anticipation of CNH program expansion. The results are intended to inform expansion efforts within the CNH program.

METHODS

This study was a component of a larger research project examining VA-purchased CNH care; recruitment methods are available in previous publications describing this work.7 Participants provided written or verbal consent before video and phone interviews, respectively. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (Protocol #18-1186).

Video and phone interviews were conducted by 3 team members from October 2018 to March 2020 with CNH staff and VA CNH program oversight team members. Participant recruitment was paused from May to October 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and ambiguity about VA NH care purchasing policies following the passage of the VA MISSION Act.5 We used semistructured interview guides (eAppendix 1 for VA staff and eAppendix 2 for NH staff, available online at doi:10.12788/fp.0421). Recorded and transcribed interviews ranged from 15 to 90 minutes.

Two members of the research team analyzed transcripts using both deductive and inductive content analysis.8 The interview guide informed an a priori codebook, and in vivo codes were included as they emerged. We jointly coded 6 transcripts to reach a consensus on coding approaches and analyzed the remaining transcripts independently with frequent meetings to develop themes with a qualitative methodologist. All qualitative data were analyzed using ATLAS.ti software.

This was a retrospective observational study of veterans who received VA-paid care in CNHs during the 2019 fiscal year (10/1/2018-9/30/2019) using data from the enrollment, inpatient and outpatient encounters, and other care paid for by the VA in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. We linked Centers for Medicare and Medicaid monthly Nursing Home Compare reports and the Brown University Long Term Care: Facts on Care in the US (LTC FoCUS) annual files to identify facility addresses.9

Descriptive analyses of quantitative data were conducted in parallel with the qualitative findings.8 Distance from the contracting VAMC to CNH was calculated using the greater-circle formula to find the linear distance between geographic coordinates. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently, analyzed independently, and integrated into the interpretation of results.10

RESULTS

We conducted 36 interviews with VA and NH staff who were affiliated with 6 VAMCs and 17 CNHs. Four themes emerged concerning CNH oversight: (1) benefits of VA CNH team engagement/visits; (2) burden of VA CNH oversight; (3) burden of oversight limited the ability to contract with additional NHs; and (4) factors that ease the burden and facilitate successful oversight.

Benefits of Engagement/Visits

VA SWs and nurses visit each veteran every 30 to 45 days to review their health records, meet with them, and check in with NH staff. In addition, VA SWs and nurses coordinate each veteran’s care by working as liaisons between the VA and the NH to help NH staff problem solve veteran-related issues through care conferences. VA SWs and nurses act as extra advocates for veterans to make sure their needs are met. “This program definitely helps ensure that veterans are receiving higher quality care because if we see that they aren’t, then we do something about it,” a VA NH coordinator reported in an interview.

NH staff noted benefits to monthly VA staff visits, including having an additional person coordinating care and built-in VA liaisons. “It’s nice to have that extra set of eyes, people that you can care plan with,” an NH administrator shared. “It’s definitely a true partnership, and we have open and honest conversations so we can really provide a good service for our veterans.”

Distance & High Veteran Census Burdens

VA participants described oversight components as burdensome. Specifically, several VA participants mentioned that the charting they completed in the facility during each visit proved time consuming and onerous, particularly for distant NHs. To accommodate veterans’ preferences to receive care in a facility close to their homes and families, VAMCs contract with NHs that are geographically spread out. “We’re just all spread out… staff have issues driving 2 and a half hours just to review charts all day,” a VA CNH coordinator explained. In 2019, the mean distance between VAMC and NH was 48 miles, with half located > 32 miles from the VAMC. One-quarter of NHs were > 70 miles and 44% were located > 50 miles from the VAMC (Figure 1).

Participants highlighted how regular oversight visits were particularly time consuming at CNHs with a large contracted population. VA nurses and SWs spend multiple days and up to a week conducting oversight visits at facilities with large numbers of veterans. Another VA nurse highlighted how charting requirements resulted in several days of documentation outside of the NH visit for facilities with many contracted veteran residents. Multiple VA participants noted that having many veterans at an NH exacerbated the oversight burdens. In 2019, 252 (28%) of VA CNHs had > 10 contracted veterans and 1 facility had 34 veterans (Figure 2). VA participants perceived having too many veterans concentrated at 1 facility as potentially challenging for CNHs due to the complex care needs of veterans and the added need for care coordination with the VA. One VA NH coordinator noted that while some facilities were “adept at being able to handle higher numbers” of veterans, others were “overwhelmed.” Too many veterans at an NH, an SW explained, might lead the “facility to fail because we are such a cumbersome system.”

Oversight & Staffing Burden

While several participants described wanting to contract with more NHs to avoid overwhelming existing CNHs and to increase choice for veterans, they expressed concerns about their ability to provide oversight at more facilities due to limited staffing and oversight requirements. Across VAMCs, the median number of VA CNHs varied substantially (Figure 3). One VA participant with about 35 CNHs explained that while adding more NHs could create “more opportunities and options” for veterans, it needs to be balanced with the required oversight responsibilities. One VA nurse insisted that more staff were needed to meet current and future oversight needs. “We’re all getting stretched pretty thin, and just so we don’t drop the ball on things… I would like to see a little more staff if we’re gonna have a lot more nursing homes.”

Participants had concerns related to the VA MISSION Act and the possibility of more VA-paid NHs for rehabilitation or short-term care. Participants underscored the necessity for additional staff to account for the increased oversight burden or a reduction in oversight requirements. One SW felt that increasing the number of CNHs would increase the required oversight and the need for collaboration with NH staff, which would limit her ability to establish close and trusting working relationships with NH staff. Participants also described the challenges of meeting their current oversight requirements, which limited extra visits for acute issues and care conferences. This was attributed to a lack of adequate staffing in the VA CNH program, given the time-intensive nature of VA oversight requirements.

Easing Burden & Facilitating Oversight

Participants noted how obtaining remote access to veterans’ EHRs allowed them to conduct chart reviews before oversight visits. This permitted more time for interaction with veterans and CNH staff as well as coordinating care. While providing access to the VA EHR would not change the chart review component of VA oversight, some participants felt it might improve care coordination between VA and NH staff during monthly visits.

Participants felt they were able to build strong working relationships with facilities with more veterans due to frequent communication and collaboration. VA participants also noted that CNHs with larger veteran censuses were more likely to respond to VA concerns about care to maintain the business relationship and contract. To optimize strong working relationships and decrease the challenges of having too many veterans at a facility, some VA participants suggested that CNH programs create a local policy to recommend the number of veterans placed in a CNH.

Discussion

Participants interviewed for this study echoed findings from previous work that identified the importance of developing trusted working relationships with CNHs to care for veterans.11,12 However, interorganizational care coordination, a shortage of health care professionals, and resource demands associated with caring for veterans reported in other community care settings were also noted in our findings.12,13

Building upon prior recommendations related to community care of veterans, our analysis identified key areas that could improve CNH program oversight efficiency, including: (1) improving the interoperability of EHRs to facilitate coordination of care and oversight; (2) addressing inefficiencies associated with traveling to geographically dispersed CNHs; and (3) “right-sizing” the number of veterans residing in each CNH.

The interoperability of EHRs has been cited by multiple studies of VA community care programs as critical to reducing inefficiencies and allowing more in-person time with veterans and staff in care coordination, especially at rural locations.11-15 The Veterans Health Information Exchange Program is designed to optimize data sharing as veterans are increasingly referred to non-VA care through the MISSION Act. This program is organized around patient engagement, clinician adoption, partner engagement, and technological capabilities.16

Unfortunately, significant barriers exist for the VA CNH program within each of these information exchange domains. For example, patient engagement requires veteran consent for consumer-initiated exchange of medical information, which is not practical due to the high prevalence of cognitive impairment in NHs. Similarly, VA consent requirements prohibit EHR download and sharing with non-VA facilities like CNHs, limiting use. eHealth Exchange partnerships allow organizations caring for veterans to connect with the VA via networks that provide a common trust agreement and technical compliance testing. Unfortunately, in 2017, only 257 NHs in which veterans received care nationally were eHealth Exchange partners, which indicates that while NHs could partner in this information exchange, very few did.16

Finally, while the exchange is possible, it is not practical; most CNHs lack the staff that would be required to support data transfer on their technology platform into the appropriate translational gateways. Although remote access to EHRs in CNHs improved during the pandemic, the Veterans Health Information Exchange Program is not designed to facilitate interoperability of VA and CNH records and remains a significant barrier for this and many other VA community care programs.

The dispersal of veterans across CNHs that are > 50 miles from the nearest VAMC represents an additional area to improve program efficiency and meet growing demands for rural care. While recent field guidance to CNH oversight teams reduces the frequency of visits by VA CNH teams, the burden of driving to each facility is not likely to decrease as CNHs increasingly offer rehabilitation as a part of Veteran Care Agreements.17 Visits performed by telehealth or by trained local VA staff may represent alternatives.15

Finally, interview participants described the ideal range of the number of veterans in each CNH necessary to optimize efficiencies. Veterans who rely more heavily upon VA care tend to have more medical and mental health comorbidities than average Medicare beneficiaries.18,19 This was reflected in participants’ recommendation to have enough veterans to benefit from economies of scale but to also identify a limit when efficiencies are lost. Given that most CNHs cared for 8 to 15 veterans, facilities seem to have identified how best to match the resources available with veterans’ care needs. Based on these observations, new care networks that will be established because of the MISSION Act may benefit from establishing evidence-based policies that support flexibility in oversight frequency and either allow for remote oversight or consolidate the number of CNHs to improve efficiencies in care provision and oversight.20

Limitations

Limitations include the unique relationship between VA and CNH staff overseeing the quality of care provided to veterans in CNHs, which is not replicated in other models of care. Data collection was interrupted following the passage of the MISSION Act in 2018 until guidance on changes to practice resulting from the law were clarified in 2020. Interviews were also interrupted at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

The current quality of the CNH care oversight structure will require adaptation as demand for CNH care increases. While the VA CNH program is one of the longest-standing programs collaborating with non-VA community care partners, it is now only one of many following the MISSION Act. The success of this and other programs will depend on matching available CNH resources to the complex medical and psychological needs of veterans. At a time when strategies to ease the burden on NHs and VA CNH coordinators are desperately needed, Veterans Health Information Exchange capabilities need to improve. Evidence is needed to guide the scaling of the program to meet the needs of the rapidly expanding veteran population who are eligible for CNH care.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Amy Mochel of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center for project management support of this project.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Community Nursing Home (CNH) program provides 24-hour skilled nursing care for eligible veterans in public or private community-based facilities that have established a contract to care for veterans. Veteran eligibility is based on service-connected status and level of disability, covering the cost of care for veterans who need long-term care because of their service-connected disability or for veterans with disabilities rated at ≥ 70%.1 Between 2014 and 2018, the average daily census of veterans in CNHs increased by 26% and the percentage of funds obligated to this program increased by 49%.2 The VA projects that the number of veterans receiving care in a CNH program will increase by 80% between 2017 and 2037, corresponding to a 149% increase in CNH expenditures.2

CNH program oversight teams are mandated at each VA medical center (VAMC) to monitor care coordination within the CNH program. These teams include nurses and social workers (SWs) who perform regular on-site assessments to monitor the clinical, functional, and psychosocial needs of veterans. These assessments include a review of the electronic health record (EHR) and face-to-face contact with veterans and CNH staff, regardless of the purchasing authority (hospice, long-term care, short-term rehabilitation, respite care).3 These teams represent key stakeholders impacted by CNH program expansion.

While the CNH program has focused primarily on the provision of long-term care, the VA is now expanding to include short-term rehabilitation through Veteran Care Agreements.4 These agreements are authorized under the MISSION Act, designed to improve care for veterans.5 Veteran Care Agreements are expected to be less burdensome to execute than traditional contracts and will permit the VA to partner with more CNHs, as noted in a Congressional Research Service report regarding long-term care services for veterans.6 However, increasing the number of CNHs increases demands on oversight teams, particularly if the coordinators are compelled to perform monthly on-site visits to facilities required under current guidelines.3

The objective of this study was to describe the experiences of VA and CNH staff involved in care coordination and the oversight of veterans receiving CNH care amid Veteran Care Agreement implementation and in anticipation of CNH program expansion. The results are intended to inform expansion efforts within the CNH program.

METHODS

This study was a component of a larger research project examining VA-purchased CNH care; recruitment methods are available in previous publications describing this work.7 Participants provided written or verbal consent before video and phone interviews, respectively. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (Protocol #18-1186).

Video and phone interviews were conducted by 3 team members from October 2018 to March 2020 with CNH staff and VA CNH program oversight team members. Participant recruitment was paused from May to October 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and ambiguity about VA NH care purchasing policies following the passage of the VA MISSION Act.5 We used semistructured interview guides (eAppendix 1 for VA staff and eAppendix 2 for NH staff, available online at doi:10.12788/fp.0421). Recorded and transcribed interviews ranged from 15 to 90 minutes.

Two members of the research team analyzed transcripts using both deductive and inductive content analysis.8 The interview guide informed an a priori codebook, and in vivo codes were included as they emerged. We jointly coded 6 transcripts to reach a consensus on coding approaches and analyzed the remaining transcripts independently with frequent meetings to develop themes with a qualitative methodologist. All qualitative data were analyzed using ATLAS.ti software.

This was a retrospective observational study of veterans who received VA-paid care in CNHs during the 2019 fiscal year (10/1/2018-9/30/2019) using data from the enrollment, inpatient and outpatient encounters, and other care paid for by the VA in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. We linked Centers for Medicare and Medicaid monthly Nursing Home Compare reports and the Brown University Long Term Care: Facts on Care in the US (LTC FoCUS) annual files to identify facility addresses.9

Descriptive analyses of quantitative data were conducted in parallel with the qualitative findings.8 Distance from the contracting VAMC to CNH was calculated using the greater-circle formula to find the linear distance between geographic coordinates. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently, analyzed independently, and integrated into the interpretation of results.10

RESULTS

We conducted 36 interviews with VA and NH staff who were affiliated with 6 VAMCs and 17 CNHs. Four themes emerged concerning CNH oversight: (1) benefits of VA CNH team engagement/visits; (2) burden of VA CNH oversight; (3) burden of oversight limited the ability to contract with additional NHs; and (4) factors that ease the burden and facilitate successful oversight.

Benefits of Engagement/Visits

VA SWs and nurses visit each veteran every 30 to 45 days to review their health records, meet with them, and check in with NH staff. In addition, VA SWs and nurses coordinate each veteran’s care by working as liaisons between the VA and the NH to help NH staff problem solve veteran-related issues through care conferences. VA SWs and nurses act as extra advocates for veterans to make sure their needs are met. “This program definitely helps ensure that veterans are receiving higher quality care because if we see that they aren’t, then we do something about it,” a VA NH coordinator reported in an interview.

NH staff noted benefits to monthly VA staff visits, including having an additional person coordinating care and built-in VA liaisons. “It’s nice to have that extra set of eyes, people that you can care plan with,” an NH administrator shared. “It’s definitely a true partnership, and we have open and honest conversations so we can really provide a good service for our veterans.”

Distance & High Veteran Census Burdens

VA participants described oversight components as burdensome. Specifically, several VA participants mentioned that the charting they completed in the facility during each visit proved time consuming and onerous, particularly for distant NHs. To accommodate veterans’ preferences to receive care in a facility close to their homes and families, VAMCs contract with NHs that are geographically spread out. “We’re just all spread out… staff have issues driving 2 and a half hours just to review charts all day,” a VA CNH coordinator explained. In 2019, the mean distance between VAMC and NH was 48 miles, with half located > 32 miles from the VAMC. One-quarter of NHs were > 70 miles and 44% were located > 50 miles from the VAMC (Figure 1).

Participants highlighted how regular oversight visits were particularly time consuming at CNHs with a large contracted population. VA nurses and SWs spend multiple days and up to a week conducting oversight visits at facilities with large numbers of veterans. Another VA nurse highlighted how charting requirements resulted in several days of documentation outside of the NH visit for facilities with many contracted veteran residents. Multiple VA participants noted that having many veterans at an NH exacerbated the oversight burdens. In 2019, 252 (28%) of VA CNHs had > 10 contracted veterans and 1 facility had 34 veterans (Figure 2). VA participants perceived having too many veterans concentrated at 1 facility as potentially challenging for CNHs due to the complex care needs of veterans and the added need for care coordination with the VA. One VA NH coordinator noted that while some facilities were “adept at being able to handle higher numbers” of veterans, others were “overwhelmed.” Too many veterans at an NH, an SW explained, might lead the “facility to fail because we are such a cumbersome system.”

Oversight & Staffing Burden

While several participants described wanting to contract with more NHs to avoid overwhelming existing CNHs and to increase choice for veterans, they expressed concerns about their ability to provide oversight at more facilities due to limited staffing and oversight requirements. Across VAMCs, the median number of VA CNHs varied substantially (Figure 3). One VA participant with about 35 CNHs explained that while adding more NHs could create “more opportunities and options” for veterans, it needs to be balanced with the required oversight responsibilities. One VA nurse insisted that more staff were needed to meet current and future oversight needs. “We’re all getting stretched pretty thin, and just so we don’t drop the ball on things… I would like to see a little more staff if we’re gonna have a lot more nursing homes.”

Participants had concerns related to the VA MISSION Act and the possibility of more VA-paid NHs for rehabilitation or short-term care. Participants underscored the necessity for additional staff to account for the increased oversight burden or a reduction in oversight requirements. One SW felt that increasing the number of CNHs would increase the required oversight and the need for collaboration with NH staff, which would limit her ability to establish close and trusting working relationships with NH staff. Participants also described the challenges of meeting their current oversight requirements, which limited extra visits for acute issues and care conferences. This was attributed to a lack of adequate staffing in the VA CNH program, given the time-intensive nature of VA oversight requirements.

Easing Burden & Facilitating Oversight

Participants noted how obtaining remote access to veterans’ EHRs allowed them to conduct chart reviews before oversight visits. This permitted more time for interaction with veterans and CNH staff as well as coordinating care. While providing access to the VA EHR would not change the chart review component of VA oversight, some participants felt it might improve care coordination between VA and NH staff during monthly visits.

Participants felt they were able to build strong working relationships with facilities with more veterans due to frequent communication and collaboration. VA participants also noted that CNHs with larger veteran censuses were more likely to respond to VA concerns about care to maintain the business relationship and contract. To optimize strong working relationships and decrease the challenges of having too many veterans at a facility, some VA participants suggested that CNH programs create a local policy to recommend the number of veterans placed in a CNH.

Discussion

Participants interviewed for this study echoed findings from previous work that identified the importance of developing trusted working relationships with CNHs to care for veterans.11,12 However, interorganizational care coordination, a shortage of health care professionals, and resource demands associated with caring for veterans reported in other community care settings were also noted in our findings.12,13

Building upon prior recommendations related to community care of veterans, our analysis identified key areas that could improve CNH program oversight efficiency, including: (1) improving the interoperability of EHRs to facilitate coordination of care and oversight; (2) addressing inefficiencies associated with traveling to geographically dispersed CNHs; and (3) “right-sizing” the number of veterans residing in each CNH.

The interoperability of EHRs has been cited by multiple studies of VA community care programs as critical to reducing inefficiencies and allowing more in-person time with veterans and staff in care coordination, especially at rural locations.11-15 The Veterans Health Information Exchange Program is designed to optimize data sharing as veterans are increasingly referred to non-VA care through the MISSION Act. This program is organized around patient engagement, clinician adoption, partner engagement, and technological capabilities.16

Unfortunately, significant barriers exist for the VA CNH program within each of these information exchange domains. For example, patient engagement requires veteran consent for consumer-initiated exchange of medical information, which is not practical due to the high prevalence of cognitive impairment in NHs. Similarly, VA consent requirements prohibit EHR download and sharing with non-VA facilities like CNHs, limiting use. eHealth Exchange partnerships allow organizations caring for veterans to connect with the VA via networks that provide a common trust agreement and technical compliance testing. Unfortunately, in 2017, only 257 NHs in which veterans received care nationally were eHealth Exchange partners, which indicates that while NHs could partner in this information exchange, very few did.16

Finally, while the exchange is possible, it is not practical; most CNHs lack the staff that would be required to support data transfer on their technology platform into the appropriate translational gateways. Although remote access to EHRs in CNHs improved during the pandemic, the Veterans Health Information Exchange Program is not designed to facilitate interoperability of VA and CNH records and remains a significant barrier for this and many other VA community care programs.

The dispersal of veterans across CNHs that are > 50 miles from the nearest VAMC represents an additional area to improve program efficiency and meet growing demands for rural care. While recent field guidance to CNH oversight teams reduces the frequency of visits by VA CNH teams, the burden of driving to each facility is not likely to decrease as CNHs increasingly offer rehabilitation as a part of Veteran Care Agreements.17 Visits performed by telehealth or by trained local VA staff may represent alternatives.15

Finally, interview participants described the ideal range of the number of veterans in each CNH necessary to optimize efficiencies. Veterans who rely more heavily upon VA care tend to have more medical and mental health comorbidities than average Medicare beneficiaries.18,19 This was reflected in participants’ recommendation to have enough veterans to benefit from economies of scale but to also identify a limit when efficiencies are lost. Given that most CNHs cared for 8 to 15 veterans, facilities seem to have identified how best to match the resources available with veterans’ care needs. Based on these observations, new care networks that will be established because of the MISSION Act may benefit from establishing evidence-based policies that support flexibility in oversight frequency and either allow for remote oversight or consolidate the number of CNHs to improve efficiencies in care provision and oversight.20

Limitations

Limitations include the unique relationship between VA and CNH staff overseeing the quality of care provided to veterans in CNHs, which is not replicated in other models of care. Data collection was interrupted following the passage of the MISSION Act in 2018 until guidance on changes to practice resulting from the law were clarified in 2020. Interviews were also interrupted at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

The current quality of the CNH care oversight structure will require adaptation as demand for CNH care increases. While the VA CNH program is one of the longest-standing programs collaborating with non-VA community care partners, it is now only one of many following the MISSION Act. The success of this and other programs will depend on matching available CNH resources to the complex medical and psychological needs of veterans. At a time when strategies to ease the burden on NHs and VA CNH coordinators are desperately needed, Veterans Health Information Exchange capabilities need to improve. Evidence is needed to guide the scaling of the program to meet the needs of the rapidly expanding veteran population who are eligible for CNH care.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Amy Mochel of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center for project management support of this project.

1. Miller EA, Gadbois E, Gidmark S, Intrator O. Purchasing nursing home care within the Veterans Health Administration: lessons for nursing home recruitment, contracting, and oversight. J Health Admin Educ. 2015;32(2):165-197.

2. GAO. VA health care. Veterans’ use of long-term care is increasing, and VA faces challenges in meeting the demand. February 19, 2020. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-284.pdf

3. VHA Handbook 1143.2, VHA community nursing home oversight procedures. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. June 2004. https://www.vendorportal.ecms.va.gov/FBODocumentServer/DocumentServer.aspx?DocumentId=3740930&FileName=VA259-17-Q-0501-007.pdf

4. Community care: veteran care agreements. US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2022. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed September 7, 2023. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/providers/Veterans_Care_Agreements.asp

5. Massarweh NN, Itani KMF, Morris MS. The VA MISSION Act and the future of veterans’ access to quality health care. JAMA. 2020;324(4):343-344. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4505

6. Colello KJ, Panangala SV; Congressional Research Service. Long-term care services for veterans. February 14, 2017. Accessed September 7, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44697

7. Magid KH, Galenbeck E, Haverhals LM, et al. Purchasing high-quality community nursing home care: a will to work with VHA diminished by contracting burdens. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(11):1757-1764. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2022.03.007

8. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398-405. doi:10.1111/nhs.12048

9. Brown University. LTC Focus. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://ltcfocus.org/about

10. Zhang W, Creswell J. The use of “mixing” procedure of mixed methods in health services research. Med Care. 2013;51(8):e51-e57. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824642fd

11. Haverhals LM, Magid KH, Blanchard KN, Levy CR. Veterans Health Administration staff perceptions of overseeing care in community nursing homes during COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2022;8:23337214221080307. Published 2022 Feb 15. doi:10.1177/23337214221080307

12. Garvin LA, Pugatch M, Gurewich D, Pendergast JN, Miller CJ. Interorganizational care coordination of rural veterans by Veterans Affairs and community care programs: a systematic review. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 3):S259-S269. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001542

13. Schlosser J, Kollisch D, Johnson D, Perkins T, Olson A. VA-community dual care: veteran and clinician perspectives. J Community Health. 2020;45(4):795-802. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00795-y

14. Nevedal AL, Wong EP, Urech TH, Peppiatt JL, Sorie MR, Vashi AA. Veterans’ experiences with accessing community emergency care. Mil Med. 2023;188(1-2):e58-e64. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab196

15. Levenson SA. Smart case review: a model for successful remote medical direction and enhanced nursing home quality improvement. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(10):2212-2215.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2021.05.043

16. Donahue M, Bouhaddou O, Hsing N, et al. Veterans Health Information Exchange: successes and challenges of nationwide interoperability. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:385-394. Published 2018 Dec 5.

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Notice 2023-07. Community Nursing Home Program. September 5, 2023:1-4.

18. Helmer DA, Dwibedi N, Rowneki M, et al. Mental health conditions and hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions among veterans with diabetes. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2020;13(2):61-71.

19. Rosen AK, Wagner TH, Pettey WBP, et al. Differences in risk scores of veterans receiving community care purchased by the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(suppl 3):5438-5454. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13051

20. Mattocks KM, Kroll-Desrosiers A, Kinney R, Elwy AR, Cunningham KJ, Mengeling MA. Understanding VA’s use of and relationships with community care providers under the MISSION Act. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 3):S252-S258. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001545

1. Miller EA, Gadbois E, Gidmark S, Intrator O. Purchasing nursing home care within the Veterans Health Administration: lessons for nursing home recruitment, contracting, and oversight. J Health Admin Educ. 2015;32(2):165-197.

2. GAO. VA health care. Veterans’ use of long-term care is increasing, and VA faces challenges in meeting the demand. February 19, 2020. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-284.pdf

3. VHA Handbook 1143.2, VHA community nursing home oversight procedures. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. June 2004. https://www.vendorportal.ecms.va.gov/FBODocumentServer/DocumentServer.aspx?DocumentId=3740930&FileName=VA259-17-Q-0501-007.pdf

4. Community care: veteran care agreements. US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2022. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed September 7, 2023. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/providers/Veterans_Care_Agreements.asp

5. Massarweh NN, Itani KMF, Morris MS. The VA MISSION Act and the future of veterans’ access to quality health care. JAMA. 2020;324(4):343-344. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4505

6. Colello KJ, Panangala SV; Congressional Research Service. Long-term care services for veterans. February 14, 2017. Accessed September 7, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44697

7. Magid KH, Galenbeck E, Haverhals LM, et al. Purchasing high-quality community nursing home care: a will to work with VHA diminished by contracting burdens. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(11):1757-1764. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2022.03.007

8. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398-405. doi:10.1111/nhs.12048

9. Brown University. LTC Focus. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://ltcfocus.org/about

10. Zhang W, Creswell J. The use of “mixing” procedure of mixed methods in health services research. Med Care. 2013;51(8):e51-e57. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824642fd

11. Haverhals LM, Magid KH, Blanchard KN, Levy CR. Veterans Health Administration staff perceptions of overseeing care in community nursing homes during COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2022;8:23337214221080307. Published 2022 Feb 15. doi:10.1177/23337214221080307

12. Garvin LA, Pugatch M, Gurewich D, Pendergast JN, Miller CJ. Interorganizational care coordination of rural veterans by Veterans Affairs and community care programs: a systematic review. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 3):S259-S269. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001542

13. Schlosser J, Kollisch D, Johnson D, Perkins T, Olson A. VA-community dual care: veteran and clinician perspectives. J Community Health. 2020;45(4):795-802. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00795-y

14. Nevedal AL, Wong EP, Urech TH, Peppiatt JL, Sorie MR, Vashi AA. Veterans’ experiences with accessing community emergency care. Mil Med. 2023;188(1-2):e58-e64. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab196

15. Levenson SA. Smart case review: a model for successful remote medical direction and enhanced nursing home quality improvement. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(10):2212-2215.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2021.05.043

16. Donahue M, Bouhaddou O, Hsing N, et al. Veterans Health Information Exchange: successes and challenges of nationwide interoperability. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:385-394. Published 2018 Dec 5.

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Notice 2023-07. Community Nursing Home Program. September 5, 2023:1-4.

18. Helmer DA, Dwibedi N, Rowneki M, et al. Mental health conditions and hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions among veterans with diabetes. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2020;13(2):61-71.

19. Rosen AK, Wagner TH, Pettey WBP, et al. Differences in risk scores of veterans receiving community care purchased by the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(suppl 3):5438-5454. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13051

20. Mattocks KM, Kroll-Desrosiers A, Kinney R, Elwy AR, Cunningham KJ, Mengeling MA. Understanding VA’s use of and relationships with community care providers under the MISSION Act. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 3):S252-S258. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001545

Who Receives Care in VA Medical Foster Homes?

New models are needed for delivering long-term care (LTC) that are home-based, cost-effective, and appropriate for older adults with a range of care needs.1,2 In fiscal year (FY) 2015, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) spent $7.4 billion on LTC, accounting for 13% of total VA health care spending. Overall, 71% of LTC spending in FY 2015 was allocated to institutional care.3 Beyond cost, 95% of older adults prefer to remain in community rather than institutional LTC settings, such as nursing homes.4 The COVID-19 pandemic created additional concerns related to the spread of infectious disease, with > 37% of COVID-19 deaths in the United States occurring in nursing homes irrespective of facility quality.5,6

One community-based LTC alternative developed within the VA is the Medical Foster Home (MFH) program. The MFH program is an adult foster care program in which veterans who are unable to live independently receive round-the-clock care in the home of a community-based caregiver.7 MFH caregivers usually have previous experience caring for family, working in a nursing home, or working as a caregiver in another capacity. These caregivers are responsible for providing 24-hour supervision and support to residents in their MFH and can care for up to 3 adults. In the MFH program, VA home-based primary care (HBPC) teams composed of physicians, registered nurses, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, pharmacists, dieticians, and psychologists, provide primary care for MFH veterans and oversee care in the caregiver’s home.

The goal of the VA HBPC program is to improve veterans’ access to medical care and shift LTC services from institutional to noninstitutional settings by providing in-home care for those who are too sick or disabled to go to a clinic for care. On average, veterans pay the MFH caregiver $2,500 out-of-pocket per month for their care.8 In 2016, there were 992 veterans residing in MFHs across the country.9 Since MFH program implementation expanded nationwide in 2008, more than 4,000 veterans have resided in MFHs in 45 states and territories.10

The VA is required to pay for nursing home care for veterans who have a qualifying VA service-connected disability or who meet a specific threshold of disability.11 Currently, the VA is not authorized to pay for MFH care for veterans who meet the eligibility criteria for VA-paid nursing home care. Over the past decade, the VA has introduced and expanded several initiatives and programs to help veterans who require LTC remain in their homes and communities. These include but are not limited to the Veteran Directed Care program, the Choose Home Initiative, and the Caregiver Support Program.12-14 Additionally, attempts have been made to pass legislation to authorize the VA to pay for MFH for veterans’ care whose military benefits include coverage for nursing home care.15 This legislation and VA initiatives are clear signs that the VA is committed to supporting programs such as the MFH program. Given this commitment, demand for the MFH program will likely increase.

Therefore, VA practitioners need to better identify which veterans are currently in the MFH program. While veterans are expected to need nursing home level care to qualify for MFH enrollment, little has been published about the physical and mental health care needs of veterans currently receiving MFH care. One previous study compared the demographics, diagnostic characteristics, and care utilization of MFH veterans with that of veterans receiving LTC in VA community living centers (CLCs), and found that veterans in MFHs had similar levels of frailty and comorbidity and had a higher mean age when compared with veterans in CLCs.16

Our study assessed a sample of veterans living in MFHs and describes these veterans’ clinical and functional characteristics. We used the Minimum Data Set 3.0 (MDS) to complete the assessments to allow comparisons with other populations residing in long-term care.17,18 While MDS assessments are required for Medicare/Medicaid-certified nursing home residents and for residents in VA CLCs, this study was the first attempt to perform in-home MDS data assessments in MFHs. This collection of descriptive clinical data is an important first step in providing VA practitioners with information about the characteristics of veterans currently cared for in MFHs and policymakers with data to think critically about which veterans are willing to pay for the MFH program.

Methods

This study was part of a larger research project assessing the impact of the MFH program on veterans’ outcomes and health care spending as well as factors influencing program growth.7,9,10,16,19-23 We report on the characteristics of veterans staying in MFHs, using data from the MDS, including a clinical assessment of patients’ cognitive, function, and health care–related needs, collected from participants recruited for this study.

Five research nurses were trained to administer the MDS assessment to veterans in MFHs. Data were collected between April 2014 and December 2015 from veterans at MFH sites associated with 4 urban VA medical centers in 4 different Veterans Integrated Service Networks (58 total homes). While the VA medical centers (VAMCs)were urban, many of the MFHs were in rural areas, given that MFHs can be up to 50 miles from the associated VAMC. We selected MFH sites for this study based on MFH program veteran census. Specifically, we identified MFH sites with high veteran enrollment to ensure we would have a sufficiently large sample for participant recruitment.

Veterans who had resided in an MFH for at least 90 days were eligible to participate. Of the 155 veterans mailed a letter of invitation to participate, 92 (59%) completed the in-home MDS assessment. Reasons for not participating included: 13 veterans died prior to data collection, 18 veterans declined to participate, 18 family members or legal guardians of cognitively impaired veterans did not want the veteran to participate, and 14 veterans left the MFH program or were hospitalized at the time of data collection.

Family members and legal guardians who declined participation on behalf of a veteran reported that they felt the veteran was too frail to participate or that participating would be an added burden on the veteran. Based on the census of veterans residing in all MFHs nationally in November 2015 (N = 972), 9.5% of MFH veterans were included in this study.7This study was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB #12–31), in addition to the local VA research and development review boards where MFH MDS assessments were collected.

Assessment Instrument and Variables

The MDS 3.0 assesses numerous aspects of clinical and functional status. Several resident-level characteristics from the MDS 3.0 were included in this study. The Cognitive Function Scale (CFS) was used to categorize cognitive function. The CFS is a categorical variable that is created from MDS 3.0 data. The CFS integrates self- and staff-reported data to classify individuals as cognitively intact, mildly impaired, moderately impaired, or severely impaired based on respondents’ Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS) assessment or staff-reported cognitive function collected as part of the MDS 3.0.24 We explored depression by calculating a mean summary severity score for all respondents from the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 item interview (PHQ-9).25 PHQ-9 summary scores range from 0 to 27, with mean scores of ≤ 4 indicating no or minimal depression, and higher scores corresponding to more severe depression as scores increase. For respondents who were unable to complete the PHQ-9, we calculated mean PHQ Observational Version (PHQ-9-OV) scores.

We included 2 variables to characterize behaviors: wandering frequency and presence and frequency of aggressive behaviors. We summarized aggressive behaviors using the Aggressive and Reactive Behavior Scale, which characterizes whether a resident has none, mild, moderate, or severe behavioral symptoms based on the presence and frequency of physical and verbal behaviors and resistance to care.26,27 We included items that described pain, number of falls since admission or prior assessment, degree of urinary and bowel continence (always continent vs not always continent) and mobility device use to describe respondents’ health conditions and functional status. To characterize pain, we used veteran’s self-reported frequency and intensity of pain experienced in the prior 5 days and classified the experienced pain as none, mild, moderate, or severe. Finally, demographic characteristics included age and gender.

To determine functional status, we included measures of needing help to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). The MDS allows us to understand functional status ranging from ADLs lost early in the trajectory of functional decline (ie, bathing, hygiene) to those lost in the middle (ie, walking, dressing, toileting, transferring) to those lost late in the trajectory of functional decline (ie, bed mobility and eating).28,29 To assess MFH veterans’ independence in mobility, we considered the veteran’s ability to walk without supervision or assistance in the hallway outside of their room, ability to move between their room and hallway, and ability to move throughout the house. Mobility includes use of an assistive device such as a cane, walker, or wheelchair if the veteran can use it without assistance. We summarized dependency in ADLs, using a combined score of dependence in bed mobility, transfer, locomotion on unit, dressing, eating, toilet use, and personal hygiene that ranges from 0 (independent) to 28 (completely dependent).30 Additionally, we created 3-category variables to indicate the degree of dependence in performing ADLs (independent, supervision or assistance, and completely dependent).

Finally, we included diagnoses identified as active to explore differences in neurologic, mood, psychiatric, and chronic disease morbidity. In the MDS 3.0 assessment, an active diagnosis is defined as a diagnosis documented by a licensed independent practitioner in the prior 60 days that has affected the resident or their care in the prior 7 days.

Analysis

We conducted statistical analyses using Stata MP version 15.1 (StataCorp). We summarized demographic characteristics, cognitive function scores, depression scores, pain status, behavioral symptoms, incidence of falls, degree of continence, functional status, and comorbidities, using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables.

Results

Of the 92 MFH veterans in our sample, 85% were male and 83% were aged ≥ 65 years (Table 1). Veterans had an average length of stay of 927 days at the time of MDS assessment. More than half (55%) of MFH veterans had cognitive impairment (ranging from mild to severe). The mean (SD) depression score was 3.3 (3.9), indicating minimal depression. For veterans who could not complete the depression questionnaire, the mean (SD) staff-assessed depression score was 5.9 (5.5), suggesting mild depression. Overall, 22% of the sample had aggressive behaviors but only 7 were noted to be severe. Few residents had caregiver-reported wandering. Self-reported pain intensity indicated that 45% of the sample had mild, moderate, or severe pain. While more than half the cohort had complete bowel continence (53%), only 36% had complete urinary continence. Use of mobility devices was common, with 56% of residents using a wheelchair, 42% using a walker, and 14% using a cane. One-fourth of veterans had fallen at least once since admission to the MFH.

Of the 11 ADLs assessed, the percentage of MFH veterans requiring assistance with early and mid-loss ADLs ranged from 63% for transferring to 84% for bathing (Table 2). Even for the late-loss ADL of eating, 57% of the MFH cohort required assistance. Overall, MFH veterans had an average ADL dependency score of 11.

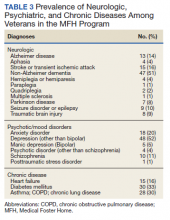

Physicians documented a diagnosis of either Alzheimer disease or non-Alzheimer dementia comorbidity for 65% of the cohort and traumatic brain injury for 9% (Table 3). Based on psychiatric comorbidities recorded in veterans’ health records, over half of MFH residents had depression (52%). Additionally, 1 in 5 MFH veterans had an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Chronic diseases were prevalent among veterans in MFHs, with 33% diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, 30% with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or chronic lung disease, and 16% with heart failure.

Discussion

In this study, we describe the characteristics of veterans receiving LTC in a sample of MFHs. This is the first study to assess veteran health and function across a group of MFHs. To help provide context for the description of MFH residents, we compared demographic characteristics, cognitive impairment, depression, pain, behaviors, functional status, and morbidity of veterans in the MFH program to long-stay residents in community nursing homes (eAppendix 1-3 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0102). A comparison with this reference population suggests that these MFH and nursing home cohorts are similar in terms of age, wandering behavior, incidence of falls, and prevalence of neurologic, psychiatric, and chronic diseases. Compared with nursing home residents, veterans in the MFH cohort had slightly higher mood symptom scores, were more likely to display aggressive behavior, and were more likely to report experiencing moderate and severe pain.

Additionally, MFH veterans displayed a lower level of cognitive impairment, fewer functional impairments, measured by the ADL dependency score, and were less likely to be bowel or bladder incontinent. Despite an overall lower ADL dependency score, a similar proportion of MFH veterans and nursing home residents were totally dependent in performing 7 of 11 ADLs and a higher proportion of MFH veterans were completely dependent for toileting (22% long-stay nursing home vs 31% MFH). The only ADLs for which there was a higher proportion of long-stay nursing home residents who were totally dependent compared with MFH residents were walking in room (54% long-stay nursing home vs 38% MFH), walking in the corridor (57% long-stay nursing home vs 33% MFH), and locomotion off the unit (36% long-stay nursing home vs 22% MFH).

While the rates of total ADL dependence among veterans in MFHs suggest that MFHs are providing care to a subset of veterans with high levels of functional impairment and care needs, MFHs are also providing care to veterans who are more independent in performing ADLs and who resemble low-care nursing home residents. A low-care nursing home resident is broadly defined as an one who does not need assistance performing late-loss ADLs (bed mobility, transferring, toileting, and eating) and who does not have the Resource Utilization Group classification of special rehab or clinically complex.31,32 Due to their overall higher functional capacity, low-care residents, even those with chronic medical care needs, may be more appropriately cared for in less intensive care settings than in nursing homes. About 5% to 30% of long-stay nursing home residents can be classified as low care.31,33-37 Additionally, a majority of newly admitted nursing home patients report a preference for or support community discharge rather than long-stay nursing home care, suggesting that many nursing home residents have the potential and desire to transition to a community-based setting.33

Based on the prevalence of veterans in our sample who are similar to low-care nursing home residents and the national focus on shifting LTC to community-based settings, MFHs may be an ideal setting for both low-care nursing home residents and those seeking community-based alternatives to traditional, institutionalized LTC. Additionally, given that we observed greater behavioral and pain needs and similar rates of comorbidities in MFH veterans relative to long-stay nursing home residents, our results indicate that MFHs also have the capacity to care for veterans with higher care needs who desire community-based LTC.

Previous research identified barriers to program MFH growth that may contribute to referral of veterans with fewer ADL dependencies compared with long-stay nursing home residents. A key barrier to MFH referral is that nursing home referral requires selection of a home, whereas MFH referral involves matching veterans with appropriate caregivers, which requires time to align the veteran’s needs with the right caregiver in the right home.7 Given the rigors of finding a match, VA staff who refer veterans may preferentially refer veterans with greater ADL impairments to nursing homes, assuming that higher levels of care needs will complicate the matching process and reserve MFH referral for only the highest functioning candidates.19 However, the ADL data presented here indicate that many MFH residents with significant levels of ADL dependence are living in MFHs. Meeting the care needs of those who have higher ADL dependencies is possible because MFH coordinators and HBPC providers deliver individual, ongoing education to MFH caregivers about caring for MFH veterans and provide available resources needed to safely care for MFH veterans across the spectrum of ADL dependency.7