User login

Small Fiber Neuropathy in Veterans With Gulf War Illness

Following deployment to operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm (Gulf War) in 1990 and 1991, many Gulf War veterans (GWVs) developed chronic, complex symptoms, including pain, dyscognition, and fatigue, with gastrointestinal, skin, and respiratory manifestations. This Gulf War Illness (GWI) is reported to affect about 30% of those deployed. More than 30 years later, there is no consensus as to the etiology of GWI, although some deployment-related exposures have been implicated.1

Accepted research definitions for GWI include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kansas definitions.2 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) uses the terminology chronic multisymptom illness (CMI), which is an overarching diagnosis under which GWI falls. Although there is no consensus case definition for CMI, there is overlap with conditions such as fibromyalgia, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome; the VA considers these as qualifying clinical diagnoses.3 The pathophysiology of GWI is also unknown, though a frequently reported unifying feature is that of autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction. Studies have demonstrated differences between veterans with GWI and those without GWI in both the reporting of symptoms attributable to ANS dysfunction and in physiologic evaluations of the ANS.4-10

Small fiber neuropathy (SFN), a condition with damage to the A-δ and C small nerve fibers, has been proposed as a potential mechanism for the pain and ANS dysfunction experienced in GWI.11-13 Symptoms of SFN are similar to those of GWI, with pain and ANS symptoms commonly reported.14,15 There are multiple diagnostic criteria for SFN, the most commonly used requiring the presence of appropriate symptoms in the absence of large fiber neuropathy and a skin biopsy demonstrating reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density.16-19 Several conditions reportedly cause SFN, most notably diabetes/prediabetes. Autoimmune disease, vitamin B12 deficiency, monoclonal gammopathies, celiac disease, paraneoplastic syndromes, and sodium channel gene mutations may also contribute to SFN.20 Hyperlipidemia has been identified as a contributor, although it has been variably reported.21,22

Idiopathic neuropathies, SFN included, may be secondary to neurotoxicant exposures. Agents whose exposure or consumption have been associated with SFN include alcohol most prominently, but also the organic solvent n-hexane, heavy metals, and excess vitamin B6.20,23-25 Agents associated with large fiber neuropathy may also have relevance for SFN, as small fibers have been likened to the “canary in the coal mine” in that they may be more susceptible to neurotoxicants and are affected earlier in the disease process.26 In this way, SFN may be the harbinger of large fiber neuropathy in some cases. Of specific relevance for GWVs, organophosphates and carbamates are known to produce a delayed onset large fiber neuropathy.27-30 Exposure to petrochemical solvents has also been associated with large fiber neuropathies.31,32

The War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC) is a clinical, research, and education center established by Congress in 2001. Its primary focus is on military exposures and postdeployment health of veterans. It is located at 3 sites: East Orange, New Jersey; Washington, DC; and Palo Alto, California. The New Jersey WRIISC began a program to evaluate GWVs with characteristic symptoms for possible SFN with use of a skin biopsy.

We hypothesize that SFN may underly much of GWI symptomatology and may not be accounted for by the putative etiologies detailed in review of the medical literature. This retrospective review of clinical evaluations for SFN in GWVs who sought care at the New Jersey WRIISC explored and addressed the following questions: (1) how common is biopsy-confirmed SFN in veterans with GWI; (2) do veterans with GWI and SFN report more symptoms attributable to ANS dysfunction when compared with veterans with GWI and no SFN; and (3) can SFN in veterans with GWI and SFN be explained by conditions and substances commonly associated with SFN? Institutional review board approval and waiver of consent was obtained from the Veterans Affairs New Jersey Health Care Center for the study.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was conducted on veterans evaluated at the WRIISC from March 1, 2015, to January 31, 2019. Inclusion criteria were: deployment to operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm between August 2, 1990, and February 28, 1991, and skin biopsy conducted at the WRIISC. Skin biopsies were obtained at the discretion of an examining clinician based on clinical indications, including neuropathic pain, ANS symptoms, and/or a fibromyalgia/chronic pain–type presentation.

Electronic health record review explicitly abstracted GWI status, results of the skin biopsy, and ANS symptom burden as determined by the Composite Autonomic Symptom Scale 31 (COMPASS 31) completed at the time of the WRIISC evaluation.

COMPASS 31 assesses symptoms across 6 domains (orthostatic, vasomotor, secretomotor, gastrointestinal, bladder, andpupillomotor). Patients are asked about symptom frequency (rarely to almost always), severity (mild to severe), and improvement (much worse to completely gone). Individual domain scores and a total weighted score (0-100) have demonstrated good validity, reliability, and consistency in SFN.33,34

In veterans with GWI and documented SFN, a health record review was performed to identify potential etiologies for SFN (Appendix).

Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS 12.0.1 for Windows were used for data collection and statistical analysis. Fisher exact test was used for comparing the prevalence of SFN in veterans with GWI vs without GWI. The independent samples t test was used for comparing COMPASS 31 scores for veterans with GWI by SFN status. α < .05 was used for determining statistical significance. For those GWVs documented with SFN and GWI, potential explanations were documented in total and by condition.

Results

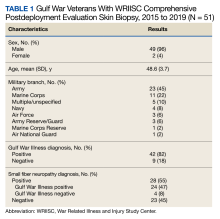

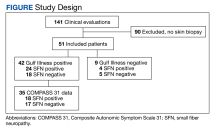

From March 1, 2015, to January 31, 2019, 141 GWVs received a comprehensive in person clinical evaluation at the WRIISC and 51 veterans (36%) received a skin biopsy and were included in this retrospective observational study (Figure). The mean age was 48.6 years, and the majority were male and served in the US Army. Skin biopsies met clinical criteria for GWI for 42 (82%) and 24 of 42 (57%) were determined to have SFN. Four of 9 (44%) veterans without GWI had positive SFN biopsies, though this difference was not statistically significant (Table 1). Veterans with SFN but no GWI were not included in the further analysis.

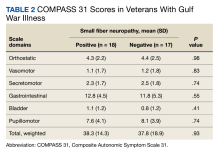

Thirty-five veterans with GWI—18 with SFN and 17 without SFN—completed the COMPASS 31 (Table 2). COMPASS 31 data were not analyzed for veterans without GWI. Individual domain scores and the difference in COMPASS 31 scores for veterans with GWI and SFN vs GWI and no SFN (38.3 vs 37.8, respectively) were not statistically significant.

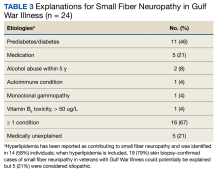

Sixteen of 24 veterans with GWI and SFN (67%) had ≥ 1 conditions that could potentially be responsible for SFN (Table 3), including 11 veterans (46%) with prediabetes/diabetes. Hyperlipidemia is only variably reported as a cause of SFN; when included, 19 of 24 (79%) SFN cases were accounted for. We could not identify a medical explanation for SFN in 5 of 24 veterans (21%) with GWI, which were deemed to be idiopathic.

Discussion

Biopsy-confirmed SFN was present in more than half of our sample of veterans with GWI, which is broadly consistent with what has been reported in the literature.13,35-38 In this clinical observation study, SFN was similarly prevalent in veterans with and without GWI; although it should be noted that biopsies only were obtained when there was a strong clinical suspicion for SFN. Almost half of patients with GWI did not have SFN, so our study does not support SFN as the underlying explanation for all GWI. Although our data cannot provide clinical guidance as to when skin biopsy may be indicated in GWI, work done in fibromyalgia found symptoms of dysautonomia and paresthesias are more specific for SFN and may be useful to help guide medical decision making.39

Veterans with GWI in our clinical sample reported a high burden of clinical symptoms conceivably attributable to ANS dysfunction. This symptom reporting is consistent with that seen in other GWI studies, as well as in other studies of SFN.4,5,7-9,14,15,34,38,40 Our clinical sample of veterans with GWI found no differences in the ANS symptom reporting between those with and without SFN. Therefore, our study cannot support SFN alone as accounting for ANS symptom burden in patients with GWI.

Two-thirds of biopsy-confirmed SFN in our clinical sample of veterans with GWI could potentially be explained by established medical conditions. As in other studies of SFN, prediabetes and diabetes represented a plurality (46%). Even after considering hyperlipidemia as a potential explanation, about 21% of SFN cases in veterans with GWI still were deemed idiopathic.

Evidence supports certain environmental agents as causal factors for GWI. Neurotoxicants reportedly related to GWI include pesticides (particularly organophosphates and carbamates), pyridostigmine bromide (used during the Gulf War as a prophylactic agent against the use of chemical weapons), and low levels of the nerve agent sarin from environmental contamination due to chemical weapons detonations.1 Some of these agents have been implicated in neuropathy as well.1,28-30 It is biologically plausible that deployment-related exposures could trigger SFN, though the traditional consensus has been that remote exposure to neurotoxic substances is unlikely to produce neuropathy that presents many years after the exposure.41 In the WRIISC clinical experience, however, veterans often report that their neuropathic symptoms predate the diagnosis of the associated medical conditions, sometimes by decades. It is conceivable that remote exposures may trigger the condition that is then potentiated by ongoing exposures, metabolic factors, and/or other medical conditions. These may perpetuate neuropathic symptoms and the illness experience of affected veterans. Our clinical observation study cannot clarify the extent to which this may be the case. Despite these findings and arguments, an environmental contribution to SFN cannot be discounted, and further research is needed to explore a potential relationship.

Limitations

This study’s conclusions are limited by its observational/retrospective design in a relatively small clinical sample of veterans evaluated at a tertiary referral center for postdeployment exposure-related health concerns. The WRIISC clinical sample is not representative of all GWVs or even of all veterans with GWI, as there is inherent selection bias as to who gets referred to and evaluated at the WRIISC. As with studies based on retrospective chart review, data are reliant on clinical documentation andaccuracy/consistency of the reviewer. Evaluation for SFN with skin biopsy is an invasive procedure and was performed when a high index of clinical suspicion for this condition existed, possibly representing confirmation bias. Therefore, the relatively high prevalence ofbiopsy-confirmed SFN seen in our clinical sample cannot be generalized to GWVs as a whole or even to veterans with GWI.

Assessment of autonomic dysfunction was based on COMPASS 31 symptom reporting by an small subset of the clinical cohort. Symptom reporting may not be reflective of true abnormality in ANS function. Physiologic tests of the ANS were not performed; such studies could more objectively establish whether ANS dysfunction is more prevalent in GWI veterans with SFN.

Evaluation for all potential etiologic/contributory conditions to SFN was not exhaustive. For example, sodium channel gene mutations have been documented to account for up to one-third of all cases of idiopathic SFN.42 For those cases in which no compelling etiology was identified, it is plausible that medical explanations for SFN may be found on further investigation.

Clinical assessments at the WRIISC were performed on GWVs ≥ 26 years after their deployment-related exposures. Other conditions/exposures may have occurred in the interim. What is not clear is whether the SFN predated the onset of any of these medical conditions or other putative contributors. This observational study is not able to tease out a temporal association to make a cause-and-effect assessment.

Conclusions

Retrospective analysis of clinical data of veterans evaluated at a specialized center for postdeployment health demonstrated that skin biopsy–confirmed SFN was prevalent, but not ubiquitous, in veterans with GWI. Symptom that may be attributed to ANS dysfunction in this clinical sample was consistent with literature on SFN and with GWI, but we could not definitively attribute ANS symptoms to SFN. Our study does not support the hypothesis that GWI symptoms are solely due to SFN, though it may still be relevant in a subset of veterans with GWI with strongly suggestive clinical features. We were able to identify a potential etiology for SFN in most veterans with GWI. Further investigations are recommended to explore any potential relationship between Gulf War exposures and SFN.

1. White RF, Steele L, O’Callaghan JP, et al. Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: effects of toxicant exposures during deployment. Cortex. 2016;74:449-475. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2015.08.022

2. Committee on the Development of a Consensus Case Definition for Chronic Multisymptom Illness in 1990-1991 Gulf War Veterans, Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined. National Academies Press; 2014.

3. Robbins R, Helmer D, Monahan P, et al. Management of chronic multisymptom illness: synopsis of the 2021 US Department of Veterans Affairs and US Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(5):991-1002. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.01.031

4. Fox A, Helmer D, Tseng CL, Patrick-DeLuca L, Osinubi O. Report of autonomic symptoms in a clinical sample of veterans with Gulf War Illness. Mil Med. 2018;183(3-4):e179-e185. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx052

5. Fox A, Helmer D, Tseng CL, McCarron K, Satcher S, Osinubi O. Autonomic symptoms in Gulf War veterans evaluated at the War Related Illness and Injury Study Center. Mil Med. 2019;184(3-4):e191-e196. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy227

6. Reyes L, Falvo M, Blatt M, Ghobreal B, Acosta A, Serrador J. Autonomic dysfunction in veterans with Gulf War illness [abstract]. FASEB J. 2014;28(S1):1068.19. doi:10.1096/fasebj.28.1_supplement.1068.19

7. Haley RW, Charuvastra E, Shell WE, et al. Cholinergic autonomic dysfunction in veterans with Gulf War illness: confirmation in a population-based sample. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(2):191-200. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.596

8. Haley RW, Vongpatanasin W, Wolfe GI, et al. Blunted circadian variation in autonomic regulation of sinus node function in veterans with Gulf War syndrome. Am J Med. 2004;117(7):469-478. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.041

9. Avery TJ, Mathersul DC, Schulz-Heik RJ, Mahoney L, Bayley PJ. Self-reported autonomic dysregulation in Gulf War Illness. Mil Med. Published online December 30, 2021. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab546

10. Verne ZT, Fields JZ, Zhang BB, Zhou Q. Autonomic dysfunction and gastroparesis in Gulf War veterans. J Investig Med. 2023;71(1):7-10. doi:10.1136/jim-2021-002291

11. Levine TD. Small fiber neuropathy: disease classification beyond pain and burning. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2018;10:1179573518771703. doi:10.1177/1179573518771703

12. Novak P. Autonomic disorders. Am J Med. 2019;132(4):420-436. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.09.027

13. Oaklander AL, Klein MM. Undiagnosed small-fiber polyneuropathy: is it a component of Gulf War Illness? Defense Technical Information Center. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA613891

14. Sène D. Small fiber neuropathy: diagnosis, causes, and treatment. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85(5):553-559. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.11.002

14. Sène D. Small fiber neuropathy: diagnosis, causes, and treatment. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85(5):553-559. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.11.002

15. Novak V, Freimer ML, Kissel JT, et al. Autonomic impairment in painful neuropathy. Neurology. 2001;56(7):861-868. doi:10.1212/wnl.56.7.861

16. Myers MI, Peltier AC. Uses of skin biopsy for sensory and autonomic nerve assessment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13(1):323. doi:10.1007/s11910-012-0323-2

17. Haroutounian S, Todorovic MS, Leinders M, et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic small fiber neuropathy: a systematic review. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(2):170-177. doi:10.1002/mus.27070

18. Levine TD, Saperstein DS. Routine use of punch biopsy to diagnose small fiber neuropathy in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(3):413-417. doi:10.1007/s10067-014-2850-5

19. England JD, Gronseth G S, Franklin G, et al. Practice parameter: the evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: the role of autonomic testing, nerve biopsy, and skin biopsy (an evidence-based review). Report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. PM R. 2009;1(1):14-22. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2008.11.011

20. de Greef BTA, Hoeijmakers JGJ, Gorissen-Brouwers CML, Geerts M, Faber CG, Merkies ISJ. Associated conditions in small fiber neuropathy - a large cohort study and review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(2):348-355. doi:10.1111/ene.13508

21. Morkavuk G, Leventoglu A. Small fiber neuropathy associated with hyperlipidemia: utility of cutaneous silent periods and autonomic tests. ISRN Neurol. 2014;2014:579242. doi:10.1155/2014/579242

22. Bednarik J, Vlckova-Moravcova E, Bursova S, Belobradkova J, Dusek L, Sommer C. Etiology of small-fiber neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2009;14(3):177-183. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8027.2009.00229.x

23. Kokotis P, Papantoniou M, Schmelz M, Buntziouka C, Tzavellas E, Paparrigopoulos T. Pure small fiber neuropathy in alcohol dependency detected by skin biopsy. Alcohol Fayettev N. 2023;111:67-73. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2023.05.006

24. Guimarães-Costa R, Schoindre Y, Metlaine A, et al. N-hexane exposure: a cause of small fiber neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2018;23(2):143-146. doi:10.1111/jns.12261

25. Koszewicz M, Markowska K, Waliszewska-Prosol M, et al. The impact of chronic co-exposure to different heavy metals on small fibers of peripheral nerves. A study of metal industry workers. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2021;16(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12995-021-00302-6

26. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Small nerve fibers defy neuropathy conventions. April 11, 2016. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/small_nerve_fibers_defy_neuropathy_conventions

27. Jett DA. Neurotoxic pesticides and neurologic effects. Neurol Clin. 2011;29(3):667-677. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2011.06.002

28. Berger AR, Schaumburg HH. Human toxic neuropathy caused by industrial agents. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy. 4th ed. Saunders; 2005:2505-2525. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7216-9491-7.50115-0

29. Herskovitz S, Schaumburg HH. Neuropathy caused by drugs. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy. 4th ed. Saunders; 2005:2553-2583.

30. Katona I, Weis J. Chapter 31 - Diseases of the peripheral nerves. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;145:453-474. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-802395-2.00031-6

31. Matikainen E, Juntunen J. Autonomic nervous system dysfunction in workers exposed to organic solvents. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48(10):1021-1024. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.10.1021

32. Murata K, Araki S, Yokoyama K, Maeda K. Autonomic and peripheral nervous system dysfunction in workers exposed to mixed organic solvents. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1991;63(5):335-340. doi:10.1007/BF00381584

33. Sletten DM, Suarez GA, Low PA, Mandrekar J, Singer W. COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated Composite Autonomic Symptom Score. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1196-1201. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.013

34. Treister R, O’Neil K, Downs HM, Oaklander AL. Validation of the Composite Autonomic Symptom Scale-31 (COMPASS-31) in patients with and without small-fiber polyneuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(7):1124-1130. doi:10.1111/ene.12717

35. Joseph P, Arevalo C, Oliveira RKF, et al. Insights from invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Chest. 2021;160(2):642-651. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.082

36. Giannoccaro MP, Donadio V, Incensi A, Avoni P, Liguori R. Small nerve fiber involvement in patients referred for fibromyalgia. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49(5):757-759. doi:10.1002/mus.24156

37. Oaklander AL, Herzog ZD, Downs HM, Klein MM. Objective evidence that small-fiber polyneuropathy underlies some illnesses currently labeled as fibromyalgia. Pain. 2013;154(11):2310-2316. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.001

38. Serrador JM. Diagnosis of late-stage, early-onset, small-fiber polyneuropathy. Defense Technical Information Center. December 1, 2019. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1094831

39. Lodahl M, Treister R, Oaklander AL. Specific symptoms may discriminate between fibromyalgia patients with vs without objective test evidence of small-fiber polyneuropathy. Pain Rep. 2018;3(1):e633. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000633

40. Sastre A, Cook MR. Autonomic dysfunction in Gulf War veterans. Defense Technical Information Center. April 1, 2004. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA429525

41. Little AA, Albers JW. Clinical description of toxic neuropathies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2015;131:253-296. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62627-1.00015-9

42. Faber CG, Hoeijmakers JGJ, Ahn HS, et al. Gain of function NaV1.7 mutations in idiopathic small fiber neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(1):26-39.

Following deployment to operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm (Gulf War) in 1990 and 1991, many Gulf War veterans (GWVs) developed chronic, complex symptoms, including pain, dyscognition, and fatigue, with gastrointestinal, skin, and respiratory manifestations. This Gulf War Illness (GWI) is reported to affect about 30% of those deployed. More than 30 years later, there is no consensus as to the etiology of GWI, although some deployment-related exposures have been implicated.1

Accepted research definitions for GWI include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kansas definitions.2 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) uses the terminology chronic multisymptom illness (CMI), which is an overarching diagnosis under which GWI falls. Although there is no consensus case definition for CMI, there is overlap with conditions such as fibromyalgia, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome; the VA considers these as qualifying clinical diagnoses.3 The pathophysiology of GWI is also unknown, though a frequently reported unifying feature is that of autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction. Studies have demonstrated differences between veterans with GWI and those without GWI in both the reporting of symptoms attributable to ANS dysfunction and in physiologic evaluations of the ANS.4-10

Small fiber neuropathy (SFN), a condition with damage to the A-δ and C small nerve fibers, has been proposed as a potential mechanism for the pain and ANS dysfunction experienced in GWI.11-13 Symptoms of SFN are similar to those of GWI, with pain and ANS symptoms commonly reported.14,15 There are multiple diagnostic criteria for SFN, the most commonly used requiring the presence of appropriate symptoms in the absence of large fiber neuropathy and a skin biopsy demonstrating reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density.16-19 Several conditions reportedly cause SFN, most notably diabetes/prediabetes. Autoimmune disease, vitamin B12 deficiency, monoclonal gammopathies, celiac disease, paraneoplastic syndromes, and sodium channel gene mutations may also contribute to SFN.20 Hyperlipidemia has been identified as a contributor, although it has been variably reported.21,22

Idiopathic neuropathies, SFN included, may be secondary to neurotoxicant exposures. Agents whose exposure or consumption have been associated with SFN include alcohol most prominently, but also the organic solvent n-hexane, heavy metals, and excess vitamin B6.20,23-25 Agents associated with large fiber neuropathy may also have relevance for SFN, as small fibers have been likened to the “canary in the coal mine” in that they may be more susceptible to neurotoxicants and are affected earlier in the disease process.26 In this way, SFN may be the harbinger of large fiber neuropathy in some cases. Of specific relevance for GWVs, organophosphates and carbamates are known to produce a delayed onset large fiber neuropathy.27-30 Exposure to petrochemical solvents has also been associated with large fiber neuropathies.31,32

The War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC) is a clinical, research, and education center established by Congress in 2001. Its primary focus is on military exposures and postdeployment health of veterans. It is located at 3 sites: East Orange, New Jersey; Washington, DC; and Palo Alto, California. The New Jersey WRIISC began a program to evaluate GWVs with characteristic symptoms for possible SFN with use of a skin biopsy.

We hypothesize that SFN may underly much of GWI symptomatology and may not be accounted for by the putative etiologies detailed in review of the medical literature. This retrospective review of clinical evaluations for SFN in GWVs who sought care at the New Jersey WRIISC explored and addressed the following questions: (1) how common is biopsy-confirmed SFN in veterans with GWI; (2) do veterans with GWI and SFN report more symptoms attributable to ANS dysfunction when compared with veterans with GWI and no SFN; and (3) can SFN in veterans with GWI and SFN be explained by conditions and substances commonly associated with SFN? Institutional review board approval and waiver of consent was obtained from the Veterans Affairs New Jersey Health Care Center for the study.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was conducted on veterans evaluated at the WRIISC from March 1, 2015, to January 31, 2019. Inclusion criteria were: deployment to operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm between August 2, 1990, and February 28, 1991, and skin biopsy conducted at the WRIISC. Skin biopsies were obtained at the discretion of an examining clinician based on clinical indications, including neuropathic pain, ANS symptoms, and/or a fibromyalgia/chronic pain–type presentation.

Electronic health record review explicitly abstracted GWI status, results of the skin biopsy, and ANS symptom burden as determined by the Composite Autonomic Symptom Scale 31 (COMPASS 31) completed at the time of the WRIISC evaluation.

COMPASS 31 assesses symptoms across 6 domains (orthostatic, vasomotor, secretomotor, gastrointestinal, bladder, andpupillomotor). Patients are asked about symptom frequency (rarely to almost always), severity (mild to severe), and improvement (much worse to completely gone). Individual domain scores and a total weighted score (0-100) have demonstrated good validity, reliability, and consistency in SFN.33,34

In veterans with GWI and documented SFN, a health record review was performed to identify potential etiologies for SFN (Appendix).

Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS 12.0.1 for Windows were used for data collection and statistical analysis. Fisher exact test was used for comparing the prevalence of SFN in veterans with GWI vs without GWI. The independent samples t test was used for comparing COMPASS 31 scores for veterans with GWI by SFN status. α < .05 was used for determining statistical significance. For those GWVs documented with SFN and GWI, potential explanations were documented in total and by condition.

Results

From March 1, 2015, to January 31, 2019, 141 GWVs received a comprehensive in person clinical evaluation at the WRIISC and 51 veterans (36%) received a skin biopsy and were included in this retrospective observational study (Figure). The mean age was 48.6 years, and the majority were male and served in the US Army. Skin biopsies met clinical criteria for GWI for 42 (82%) and 24 of 42 (57%) were determined to have SFN. Four of 9 (44%) veterans without GWI had positive SFN biopsies, though this difference was not statistically significant (Table 1). Veterans with SFN but no GWI were not included in the further analysis.

Thirty-five veterans with GWI—18 with SFN and 17 without SFN—completed the COMPASS 31 (Table 2). COMPASS 31 data were not analyzed for veterans without GWI. Individual domain scores and the difference in COMPASS 31 scores for veterans with GWI and SFN vs GWI and no SFN (38.3 vs 37.8, respectively) were not statistically significant.

Sixteen of 24 veterans with GWI and SFN (67%) had ≥ 1 conditions that could potentially be responsible for SFN (Table 3), including 11 veterans (46%) with prediabetes/diabetes. Hyperlipidemia is only variably reported as a cause of SFN; when included, 19 of 24 (79%) SFN cases were accounted for. We could not identify a medical explanation for SFN in 5 of 24 veterans (21%) with GWI, which were deemed to be idiopathic.

Discussion

Biopsy-confirmed SFN was present in more than half of our sample of veterans with GWI, which is broadly consistent with what has been reported in the literature.13,35-38 In this clinical observation study, SFN was similarly prevalent in veterans with and without GWI; although it should be noted that biopsies only were obtained when there was a strong clinical suspicion for SFN. Almost half of patients with GWI did not have SFN, so our study does not support SFN as the underlying explanation for all GWI. Although our data cannot provide clinical guidance as to when skin biopsy may be indicated in GWI, work done in fibromyalgia found symptoms of dysautonomia and paresthesias are more specific for SFN and may be useful to help guide medical decision making.39

Veterans with GWI in our clinical sample reported a high burden of clinical symptoms conceivably attributable to ANS dysfunction. This symptom reporting is consistent with that seen in other GWI studies, as well as in other studies of SFN.4,5,7-9,14,15,34,38,40 Our clinical sample of veterans with GWI found no differences in the ANS symptom reporting between those with and without SFN. Therefore, our study cannot support SFN alone as accounting for ANS symptom burden in patients with GWI.

Two-thirds of biopsy-confirmed SFN in our clinical sample of veterans with GWI could potentially be explained by established medical conditions. As in other studies of SFN, prediabetes and diabetes represented a plurality (46%). Even after considering hyperlipidemia as a potential explanation, about 21% of SFN cases in veterans with GWI still were deemed idiopathic.

Evidence supports certain environmental agents as causal factors for GWI. Neurotoxicants reportedly related to GWI include pesticides (particularly organophosphates and carbamates), pyridostigmine bromide (used during the Gulf War as a prophylactic agent against the use of chemical weapons), and low levels of the nerve agent sarin from environmental contamination due to chemical weapons detonations.1 Some of these agents have been implicated in neuropathy as well.1,28-30 It is biologically plausible that deployment-related exposures could trigger SFN, though the traditional consensus has been that remote exposure to neurotoxic substances is unlikely to produce neuropathy that presents many years after the exposure.41 In the WRIISC clinical experience, however, veterans often report that their neuropathic symptoms predate the diagnosis of the associated medical conditions, sometimes by decades. It is conceivable that remote exposures may trigger the condition that is then potentiated by ongoing exposures, metabolic factors, and/or other medical conditions. These may perpetuate neuropathic symptoms and the illness experience of affected veterans. Our clinical observation study cannot clarify the extent to which this may be the case. Despite these findings and arguments, an environmental contribution to SFN cannot be discounted, and further research is needed to explore a potential relationship.

Limitations

This study’s conclusions are limited by its observational/retrospective design in a relatively small clinical sample of veterans evaluated at a tertiary referral center for postdeployment exposure-related health concerns. The WRIISC clinical sample is not representative of all GWVs or even of all veterans with GWI, as there is inherent selection bias as to who gets referred to and evaluated at the WRIISC. As with studies based on retrospective chart review, data are reliant on clinical documentation andaccuracy/consistency of the reviewer. Evaluation for SFN with skin biopsy is an invasive procedure and was performed when a high index of clinical suspicion for this condition existed, possibly representing confirmation bias. Therefore, the relatively high prevalence ofbiopsy-confirmed SFN seen in our clinical sample cannot be generalized to GWVs as a whole or even to veterans with GWI.

Assessment of autonomic dysfunction was based on COMPASS 31 symptom reporting by an small subset of the clinical cohort. Symptom reporting may not be reflective of true abnormality in ANS function. Physiologic tests of the ANS were not performed; such studies could more objectively establish whether ANS dysfunction is more prevalent in GWI veterans with SFN.

Evaluation for all potential etiologic/contributory conditions to SFN was not exhaustive. For example, sodium channel gene mutations have been documented to account for up to one-third of all cases of idiopathic SFN.42 For those cases in which no compelling etiology was identified, it is plausible that medical explanations for SFN may be found on further investigation.

Clinical assessments at the WRIISC were performed on GWVs ≥ 26 years after their deployment-related exposures. Other conditions/exposures may have occurred in the interim. What is not clear is whether the SFN predated the onset of any of these medical conditions or other putative contributors. This observational study is not able to tease out a temporal association to make a cause-and-effect assessment.

Conclusions

Retrospective analysis of clinical data of veterans evaluated at a specialized center for postdeployment health demonstrated that skin biopsy–confirmed SFN was prevalent, but not ubiquitous, in veterans with GWI. Symptom that may be attributed to ANS dysfunction in this clinical sample was consistent with literature on SFN and with GWI, but we could not definitively attribute ANS symptoms to SFN. Our study does not support the hypothesis that GWI symptoms are solely due to SFN, though it may still be relevant in a subset of veterans with GWI with strongly suggestive clinical features. We were able to identify a potential etiology for SFN in most veterans with GWI. Further investigations are recommended to explore any potential relationship between Gulf War exposures and SFN.

Following deployment to operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm (Gulf War) in 1990 and 1991, many Gulf War veterans (GWVs) developed chronic, complex symptoms, including pain, dyscognition, and fatigue, with gastrointestinal, skin, and respiratory manifestations. This Gulf War Illness (GWI) is reported to affect about 30% of those deployed. More than 30 years later, there is no consensus as to the etiology of GWI, although some deployment-related exposures have been implicated.1

Accepted research definitions for GWI include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kansas definitions.2 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) uses the terminology chronic multisymptom illness (CMI), which is an overarching diagnosis under which GWI falls. Although there is no consensus case definition for CMI, there is overlap with conditions such as fibromyalgia, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome; the VA considers these as qualifying clinical diagnoses.3 The pathophysiology of GWI is also unknown, though a frequently reported unifying feature is that of autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction. Studies have demonstrated differences between veterans with GWI and those without GWI in both the reporting of symptoms attributable to ANS dysfunction and in physiologic evaluations of the ANS.4-10

Small fiber neuropathy (SFN), a condition with damage to the A-δ and C small nerve fibers, has been proposed as a potential mechanism for the pain and ANS dysfunction experienced in GWI.11-13 Symptoms of SFN are similar to those of GWI, with pain and ANS symptoms commonly reported.14,15 There are multiple diagnostic criteria for SFN, the most commonly used requiring the presence of appropriate symptoms in the absence of large fiber neuropathy and a skin biopsy demonstrating reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density.16-19 Several conditions reportedly cause SFN, most notably diabetes/prediabetes. Autoimmune disease, vitamin B12 deficiency, monoclonal gammopathies, celiac disease, paraneoplastic syndromes, and sodium channel gene mutations may also contribute to SFN.20 Hyperlipidemia has been identified as a contributor, although it has been variably reported.21,22

Idiopathic neuropathies, SFN included, may be secondary to neurotoxicant exposures. Agents whose exposure or consumption have been associated with SFN include alcohol most prominently, but also the organic solvent n-hexane, heavy metals, and excess vitamin B6.20,23-25 Agents associated with large fiber neuropathy may also have relevance for SFN, as small fibers have been likened to the “canary in the coal mine” in that they may be more susceptible to neurotoxicants and are affected earlier in the disease process.26 In this way, SFN may be the harbinger of large fiber neuropathy in some cases. Of specific relevance for GWVs, organophosphates and carbamates are known to produce a delayed onset large fiber neuropathy.27-30 Exposure to petrochemical solvents has also been associated with large fiber neuropathies.31,32

The War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC) is a clinical, research, and education center established by Congress in 2001. Its primary focus is on military exposures and postdeployment health of veterans. It is located at 3 sites: East Orange, New Jersey; Washington, DC; and Palo Alto, California. The New Jersey WRIISC began a program to evaluate GWVs with characteristic symptoms for possible SFN with use of a skin biopsy.

We hypothesize that SFN may underly much of GWI symptomatology and may not be accounted for by the putative etiologies detailed in review of the medical literature. This retrospective review of clinical evaluations for SFN in GWVs who sought care at the New Jersey WRIISC explored and addressed the following questions: (1) how common is biopsy-confirmed SFN in veterans with GWI; (2) do veterans with GWI and SFN report more symptoms attributable to ANS dysfunction when compared with veterans with GWI and no SFN; and (3) can SFN in veterans with GWI and SFN be explained by conditions and substances commonly associated with SFN? Institutional review board approval and waiver of consent was obtained from the Veterans Affairs New Jersey Health Care Center for the study.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was conducted on veterans evaluated at the WRIISC from March 1, 2015, to January 31, 2019. Inclusion criteria were: deployment to operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm between August 2, 1990, and February 28, 1991, and skin biopsy conducted at the WRIISC. Skin biopsies were obtained at the discretion of an examining clinician based on clinical indications, including neuropathic pain, ANS symptoms, and/or a fibromyalgia/chronic pain–type presentation.

Electronic health record review explicitly abstracted GWI status, results of the skin biopsy, and ANS symptom burden as determined by the Composite Autonomic Symptom Scale 31 (COMPASS 31) completed at the time of the WRIISC evaluation.

COMPASS 31 assesses symptoms across 6 domains (orthostatic, vasomotor, secretomotor, gastrointestinal, bladder, andpupillomotor). Patients are asked about symptom frequency (rarely to almost always), severity (mild to severe), and improvement (much worse to completely gone). Individual domain scores and a total weighted score (0-100) have demonstrated good validity, reliability, and consistency in SFN.33,34

In veterans with GWI and documented SFN, a health record review was performed to identify potential etiologies for SFN (Appendix).

Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS 12.0.1 for Windows were used for data collection and statistical analysis. Fisher exact test was used for comparing the prevalence of SFN in veterans with GWI vs without GWI. The independent samples t test was used for comparing COMPASS 31 scores for veterans with GWI by SFN status. α < .05 was used for determining statistical significance. For those GWVs documented with SFN and GWI, potential explanations were documented in total and by condition.

Results

From March 1, 2015, to January 31, 2019, 141 GWVs received a comprehensive in person clinical evaluation at the WRIISC and 51 veterans (36%) received a skin biopsy and were included in this retrospective observational study (Figure). The mean age was 48.6 years, and the majority were male and served in the US Army. Skin biopsies met clinical criteria for GWI for 42 (82%) and 24 of 42 (57%) were determined to have SFN. Four of 9 (44%) veterans without GWI had positive SFN biopsies, though this difference was not statistically significant (Table 1). Veterans with SFN but no GWI were not included in the further analysis.

Thirty-five veterans with GWI—18 with SFN and 17 without SFN—completed the COMPASS 31 (Table 2). COMPASS 31 data were not analyzed for veterans without GWI. Individual domain scores and the difference in COMPASS 31 scores for veterans with GWI and SFN vs GWI and no SFN (38.3 vs 37.8, respectively) were not statistically significant.

Sixteen of 24 veterans with GWI and SFN (67%) had ≥ 1 conditions that could potentially be responsible for SFN (Table 3), including 11 veterans (46%) with prediabetes/diabetes. Hyperlipidemia is only variably reported as a cause of SFN; when included, 19 of 24 (79%) SFN cases were accounted for. We could not identify a medical explanation for SFN in 5 of 24 veterans (21%) with GWI, which were deemed to be idiopathic.

Discussion

Biopsy-confirmed SFN was present in more than half of our sample of veterans with GWI, which is broadly consistent with what has been reported in the literature.13,35-38 In this clinical observation study, SFN was similarly prevalent in veterans with and without GWI; although it should be noted that biopsies only were obtained when there was a strong clinical suspicion for SFN. Almost half of patients with GWI did not have SFN, so our study does not support SFN as the underlying explanation for all GWI. Although our data cannot provide clinical guidance as to when skin biopsy may be indicated in GWI, work done in fibromyalgia found symptoms of dysautonomia and paresthesias are more specific for SFN and may be useful to help guide medical decision making.39

Veterans with GWI in our clinical sample reported a high burden of clinical symptoms conceivably attributable to ANS dysfunction. This symptom reporting is consistent with that seen in other GWI studies, as well as in other studies of SFN.4,5,7-9,14,15,34,38,40 Our clinical sample of veterans with GWI found no differences in the ANS symptom reporting between those with and without SFN. Therefore, our study cannot support SFN alone as accounting for ANS symptom burden in patients with GWI.

Two-thirds of biopsy-confirmed SFN in our clinical sample of veterans with GWI could potentially be explained by established medical conditions. As in other studies of SFN, prediabetes and diabetes represented a plurality (46%). Even after considering hyperlipidemia as a potential explanation, about 21% of SFN cases in veterans with GWI still were deemed idiopathic.

Evidence supports certain environmental agents as causal factors for GWI. Neurotoxicants reportedly related to GWI include pesticides (particularly organophosphates and carbamates), pyridostigmine bromide (used during the Gulf War as a prophylactic agent against the use of chemical weapons), and low levels of the nerve agent sarin from environmental contamination due to chemical weapons detonations.1 Some of these agents have been implicated in neuropathy as well.1,28-30 It is biologically plausible that deployment-related exposures could trigger SFN, though the traditional consensus has been that remote exposure to neurotoxic substances is unlikely to produce neuropathy that presents many years after the exposure.41 In the WRIISC clinical experience, however, veterans often report that their neuropathic symptoms predate the diagnosis of the associated medical conditions, sometimes by decades. It is conceivable that remote exposures may trigger the condition that is then potentiated by ongoing exposures, metabolic factors, and/or other medical conditions. These may perpetuate neuropathic symptoms and the illness experience of affected veterans. Our clinical observation study cannot clarify the extent to which this may be the case. Despite these findings and arguments, an environmental contribution to SFN cannot be discounted, and further research is needed to explore a potential relationship.

Limitations

This study’s conclusions are limited by its observational/retrospective design in a relatively small clinical sample of veterans evaluated at a tertiary referral center for postdeployment exposure-related health concerns. The WRIISC clinical sample is not representative of all GWVs or even of all veterans with GWI, as there is inherent selection bias as to who gets referred to and evaluated at the WRIISC. As with studies based on retrospective chart review, data are reliant on clinical documentation andaccuracy/consistency of the reviewer. Evaluation for SFN with skin biopsy is an invasive procedure and was performed when a high index of clinical suspicion for this condition existed, possibly representing confirmation bias. Therefore, the relatively high prevalence ofbiopsy-confirmed SFN seen in our clinical sample cannot be generalized to GWVs as a whole or even to veterans with GWI.

Assessment of autonomic dysfunction was based on COMPASS 31 symptom reporting by an small subset of the clinical cohort. Symptom reporting may not be reflective of true abnormality in ANS function. Physiologic tests of the ANS were not performed; such studies could more objectively establish whether ANS dysfunction is more prevalent in GWI veterans with SFN.

Evaluation for all potential etiologic/contributory conditions to SFN was not exhaustive. For example, sodium channel gene mutations have been documented to account for up to one-third of all cases of idiopathic SFN.42 For those cases in which no compelling etiology was identified, it is plausible that medical explanations for SFN may be found on further investigation.

Clinical assessments at the WRIISC were performed on GWVs ≥ 26 years after their deployment-related exposures. Other conditions/exposures may have occurred in the interim. What is not clear is whether the SFN predated the onset of any of these medical conditions or other putative contributors. This observational study is not able to tease out a temporal association to make a cause-and-effect assessment.

Conclusions

Retrospective analysis of clinical data of veterans evaluated at a specialized center for postdeployment health demonstrated that skin biopsy–confirmed SFN was prevalent, but not ubiquitous, in veterans with GWI. Symptom that may be attributed to ANS dysfunction in this clinical sample was consistent with literature on SFN and with GWI, but we could not definitively attribute ANS symptoms to SFN. Our study does not support the hypothesis that GWI symptoms are solely due to SFN, though it may still be relevant in a subset of veterans with GWI with strongly suggestive clinical features. We were able to identify a potential etiology for SFN in most veterans with GWI. Further investigations are recommended to explore any potential relationship between Gulf War exposures and SFN.

1. White RF, Steele L, O’Callaghan JP, et al. Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: effects of toxicant exposures during deployment. Cortex. 2016;74:449-475. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2015.08.022

2. Committee on the Development of a Consensus Case Definition for Chronic Multisymptom Illness in 1990-1991 Gulf War Veterans, Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined. National Academies Press; 2014.

3. Robbins R, Helmer D, Monahan P, et al. Management of chronic multisymptom illness: synopsis of the 2021 US Department of Veterans Affairs and US Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(5):991-1002. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.01.031

4. Fox A, Helmer D, Tseng CL, Patrick-DeLuca L, Osinubi O. Report of autonomic symptoms in a clinical sample of veterans with Gulf War Illness. Mil Med. 2018;183(3-4):e179-e185. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx052

5. Fox A, Helmer D, Tseng CL, McCarron K, Satcher S, Osinubi O. Autonomic symptoms in Gulf War veterans evaluated at the War Related Illness and Injury Study Center. Mil Med. 2019;184(3-4):e191-e196. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy227

6. Reyes L, Falvo M, Blatt M, Ghobreal B, Acosta A, Serrador J. Autonomic dysfunction in veterans with Gulf War illness [abstract]. FASEB J. 2014;28(S1):1068.19. doi:10.1096/fasebj.28.1_supplement.1068.19

7. Haley RW, Charuvastra E, Shell WE, et al. Cholinergic autonomic dysfunction in veterans with Gulf War illness: confirmation in a population-based sample. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(2):191-200. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.596

8. Haley RW, Vongpatanasin W, Wolfe GI, et al. Blunted circadian variation in autonomic regulation of sinus node function in veterans with Gulf War syndrome. Am J Med. 2004;117(7):469-478. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.041

9. Avery TJ, Mathersul DC, Schulz-Heik RJ, Mahoney L, Bayley PJ. Self-reported autonomic dysregulation in Gulf War Illness. Mil Med. Published online December 30, 2021. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab546

10. Verne ZT, Fields JZ, Zhang BB, Zhou Q. Autonomic dysfunction and gastroparesis in Gulf War veterans. J Investig Med. 2023;71(1):7-10. doi:10.1136/jim-2021-002291

11. Levine TD. Small fiber neuropathy: disease classification beyond pain and burning. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2018;10:1179573518771703. doi:10.1177/1179573518771703

12. Novak P. Autonomic disorders. Am J Med. 2019;132(4):420-436. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.09.027

13. Oaklander AL, Klein MM. Undiagnosed small-fiber polyneuropathy: is it a component of Gulf War Illness? Defense Technical Information Center. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA613891

14. Sène D. Small fiber neuropathy: diagnosis, causes, and treatment. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85(5):553-559. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.11.002

14. Sène D. Small fiber neuropathy: diagnosis, causes, and treatment. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85(5):553-559. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.11.002

15. Novak V, Freimer ML, Kissel JT, et al. Autonomic impairment in painful neuropathy. Neurology. 2001;56(7):861-868. doi:10.1212/wnl.56.7.861

16. Myers MI, Peltier AC. Uses of skin biopsy for sensory and autonomic nerve assessment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13(1):323. doi:10.1007/s11910-012-0323-2

17. Haroutounian S, Todorovic MS, Leinders M, et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic small fiber neuropathy: a systematic review. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(2):170-177. doi:10.1002/mus.27070

18. Levine TD, Saperstein DS. Routine use of punch biopsy to diagnose small fiber neuropathy in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(3):413-417. doi:10.1007/s10067-014-2850-5

19. England JD, Gronseth G S, Franklin G, et al. Practice parameter: the evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: the role of autonomic testing, nerve biopsy, and skin biopsy (an evidence-based review). Report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. PM R. 2009;1(1):14-22. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2008.11.011

20. de Greef BTA, Hoeijmakers JGJ, Gorissen-Brouwers CML, Geerts M, Faber CG, Merkies ISJ. Associated conditions in small fiber neuropathy - a large cohort study and review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(2):348-355. doi:10.1111/ene.13508

21. Morkavuk G, Leventoglu A. Small fiber neuropathy associated with hyperlipidemia: utility of cutaneous silent periods and autonomic tests. ISRN Neurol. 2014;2014:579242. doi:10.1155/2014/579242

22. Bednarik J, Vlckova-Moravcova E, Bursova S, Belobradkova J, Dusek L, Sommer C. Etiology of small-fiber neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2009;14(3):177-183. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8027.2009.00229.x

23. Kokotis P, Papantoniou M, Schmelz M, Buntziouka C, Tzavellas E, Paparrigopoulos T. Pure small fiber neuropathy in alcohol dependency detected by skin biopsy. Alcohol Fayettev N. 2023;111:67-73. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2023.05.006

24. Guimarães-Costa R, Schoindre Y, Metlaine A, et al. N-hexane exposure: a cause of small fiber neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2018;23(2):143-146. doi:10.1111/jns.12261

25. Koszewicz M, Markowska K, Waliszewska-Prosol M, et al. The impact of chronic co-exposure to different heavy metals on small fibers of peripheral nerves. A study of metal industry workers. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2021;16(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12995-021-00302-6

26. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Small nerve fibers defy neuropathy conventions. April 11, 2016. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/small_nerve_fibers_defy_neuropathy_conventions

27. Jett DA. Neurotoxic pesticides and neurologic effects. Neurol Clin. 2011;29(3):667-677. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2011.06.002

28. Berger AR, Schaumburg HH. Human toxic neuropathy caused by industrial agents. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy. 4th ed. Saunders; 2005:2505-2525. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7216-9491-7.50115-0

29. Herskovitz S, Schaumburg HH. Neuropathy caused by drugs. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy. 4th ed. Saunders; 2005:2553-2583.

30. Katona I, Weis J. Chapter 31 - Diseases of the peripheral nerves. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;145:453-474. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-802395-2.00031-6

31. Matikainen E, Juntunen J. Autonomic nervous system dysfunction in workers exposed to organic solvents. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48(10):1021-1024. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.10.1021

32. Murata K, Araki S, Yokoyama K, Maeda K. Autonomic and peripheral nervous system dysfunction in workers exposed to mixed organic solvents. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1991;63(5):335-340. doi:10.1007/BF00381584

33. Sletten DM, Suarez GA, Low PA, Mandrekar J, Singer W. COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated Composite Autonomic Symptom Score. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1196-1201. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.013

34. Treister R, O’Neil K, Downs HM, Oaklander AL. Validation of the Composite Autonomic Symptom Scale-31 (COMPASS-31) in patients with and without small-fiber polyneuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(7):1124-1130. doi:10.1111/ene.12717

35. Joseph P, Arevalo C, Oliveira RKF, et al. Insights from invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Chest. 2021;160(2):642-651. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.082

36. Giannoccaro MP, Donadio V, Incensi A, Avoni P, Liguori R. Small nerve fiber involvement in patients referred for fibromyalgia. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49(5):757-759. doi:10.1002/mus.24156

37. Oaklander AL, Herzog ZD, Downs HM, Klein MM. Objective evidence that small-fiber polyneuropathy underlies some illnesses currently labeled as fibromyalgia. Pain. 2013;154(11):2310-2316. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.001

38. Serrador JM. Diagnosis of late-stage, early-onset, small-fiber polyneuropathy. Defense Technical Information Center. December 1, 2019. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1094831

39. Lodahl M, Treister R, Oaklander AL. Specific symptoms may discriminate between fibromyalgia patients with vs without objective test evidence of small-fiber polyneuropathy. Pain Rep. 2018;3(1):e633. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000633

40. Sastre A, Cook MR. Autonomic dysfunction in Gulf War veterans. Defense Technical Information Center. April 1, 2004. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA429525

41. Little AA, Albers JW. Clinical description of toxic neuropathies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2015;131:253-296. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62627-1.00015-9

42. Faber CG, Hoeijmakers JGJ, Ahn HS, et al. Gain of function NaV1.7 mutations in idiopathic small fiber neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(1):26-39.

1. White RF, Steele L, O’Callaghan JP, et al. Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: effects of toxicant exposures during deployment. Cortex. 2016;74:449-475. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2015.08.022

2. Committee on the Development of a Consensus Case Definition for Chronic Multisymptom Illness in 1990-1991 Gulf War Veterans, Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined. National Academies Press; 2014.

3. Robbins R, Helmer D, Monahan P, et al. Management of chronic multisymptom illness: synopsis of the 2021 US Department of Veterans Affairs and US Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(5):991-1002. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.01.031

4. Fox A, Helmer D, Tseng CL, Patrick-DeLuca L, Osinubi O. Report of autonomic symptoms in a clinical sample of veterans with Gulf War Illness. Mil Med. 2018;183(3-4):e179-e185. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx052

5. Fox A, Helmer D, Tseng CL, McCarron K, Satcher S, Osinubi O. Autonomic symptoms in Gulf War veterans evaluated at the War Related Illness and Injury Study Center. Mil Med. 2019;184(3-4):e191-e196. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy227

6. Reyes L, Falvo M, Blatt M, Ghobreal B, Acosta A, Serrador J. Autonomic dysfunction in veterans with Gulf War illness [abstract]. FASEB J. 2014;28(S1):1068.19. doi:10.1096/fasebj.28.1_supplement.1068.19

7. Haley RW, Charuvastra E, Shell WE, et al. Cholinergic autonomic dysfunction in veterans with Gulf War illness: confirmation in a population-based sample. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(2):191-200. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.596

8. Haley RW, Vongpatanasin W, Wolfe GI, et al. Blunted circadian variation in autonomic regulation of sinus node function in veterans with Gulf War syndrome. Am J Med. 2004;117(7):469-478. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.041

9. Avery TJ, Mathersul DC, Schulz-Heik RJ, Mahoney L, Bayley PJ. Self-reported autonomic dysregulation in Gulf War Illness. Mil Med. Published online December 30, 2021. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab546

10. Verne ZT, Fields JZ, Zhang BB, Zhou Q. Autonomic dysfunction and gastroparesis in Gulf War veterans. J Investig Med. 2023;71(1):7-10. doi:10.1136/jim-2021-002291

11. Levine TD. Small fiber neuropathy: disease classification beyond pain and burning. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2018;10:1179573518771703. doi:10.1177/1179573518771703

12. Novak P. Autonomic disorders. Am J Med. 2019;132(4):420-436. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.09.027

13. Oaklander AL, Klein MM. Undiagnosed small-fiber polyneuropathy: is it a component of Gulf War Illness? Defense Technical Information Center. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA613891

14. Sène D. Small fiber neuropathy: diagnosis, causes, and treatment. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85(5):553-559. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.11.002

14. Sène D. Small fiber neuropathy: diagnosis, causes, and treatment. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85(5):553-559. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.11.002

15. Novak V, Freimer ML, Kissel JT, et al. Autonomic impairment in painful neuropathy. Neurology. 2001;56(7):861-868. doi:10.1212/wnl.56.7.861

16. Myers MI, Peltier AC. Uses of skin biopsy for sensory and autonomic nerve assessment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13(1):323. doi:10.1007/s11910-012-0323-2

17. Haroutounian S, Todorovic MS, Leinders M, et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic small fiber neuropathy: a systematic review. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(2):170-177. doi:10.1002/mus.27070

18. Levine TD, Saperstein DS. Routine use of punch biopsy to diagnose small fiber neuropathy in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(3):413-417. doi:10.1007/s10067-014-2850-5

19. England JD, Gronseth G S, Franklin G, et al. Practice parameter: the evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: the role of autonomic testing, nerve biopsy, and skin biopsy (an evidence-based review). Report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. PM R. 2009;1(1):14-22. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2008.11.011

20. de Greef BTA, Hoeijmakers JGJ, Gorissen-Brouwers CML, Geerts M, Faber CG, Merkies ISJ. Associated conditions in small fiber neuropathy - a large cohort study and review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(2):348-355. doi:10.1111/ene.13508

21. Morkavuk G, Leventoglu A. Small fiber neuropathy associated with hyperlipidemia: utility of cutaneous silent periods and autonomic tests. ISRN Neurol. 2014;2014:579242. doi:10.1155/2014/579242

22. Bednarik J, Vlckova-Moravcova E, Bursova S, Belobradkova J, Dusek L, Sommer C. Etiology of small-fiber neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2009;14(3):177-183. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8027.2009.00229.x

23. Kokotis P, Papantoniou M, Schmelz M, Buntziouka C, Tzavellas E, Paparrigopoulos T. Pure small fiber neuropathy in alcohol dependency detected by skin biopsy. Alcohol Fayettev N. 2023;111:67-73. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2023.05.006

24. Guimarães-Costa R, Schoindre Y, Metlaine A, et al. N-hexane exposure: a cause of small fiber neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2018;23(2):143-146. doi:10.1111/jns.12261

25. Koszewicz M, Markowska K, Waliszewska-Prosol M, et al. The impact of chronic co-exposure to different heavy metals on small fibers of peripheral nerves. A study of metal industry workers. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2021;16(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12995-021-00302-6

26. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Small nerve fibers defy neuropathy conventions. April 11, 2016. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/small_nerve_fibers_defy_neuropathy_conventions

27. Jett DA. Neurotoxic pesticides and neurologic effects. Neurol Clin. 2011;29(3):667-677. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2011.06.002

28. Berger AR, Schaumburg HH. Human toxic neuropathy caused by industrial agents. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy. 4th ed. Saunders; 2005:2505-2525. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7216-9491-7.50115-0

29. Herskovitz S, Schaumburg HH. Neuropathy caused by drugs. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy. 4th ed. Saunders; 2005:2553-2583.

30. Katona I, Weis J. Chapter 31 - Diseases of the peripheral nerves. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;145:453-474. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-802395-2.00031-6

31. Matikainen E, Juntunen J. Autonomic nervous system dysfunction in workers exposed to organic solvents. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48(10):1021-1024. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.10.1021

32. Murata K, Araki S, Yokoyama K, Maeda K. Autonomic and peripheral nervous system dysfunction in workers exposed to mixed organic solvents. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1991;63(5):335-340. doi:10.1007/BF00381584

33. Sletten DM, Suarez GA, Low PA, Mandrekar J, Singer W. COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated Composite Autonomic Symptom Score. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1196-1201. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.013

34. Treister R, O’Neil K, Downs HM, Oaklander AL. Validation of the Composite Autonomic Symptom Scale-31 (COMPASS-31) in patients with and without small-fiber polyneuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(7):1124-1130. doi:10.1111/ene.12717

35. Joseph P, Arevalo C, Oliveira RKF, et al. Insights from invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Chest. 2021;160(2):642-651. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.082

36. Giannoccaro MP, Donadio V, Incensi A, Avoni P, Liguori R. Small nerve fiber involvement in patients referred for fibromyalgia. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49(5):757-759. doi:10.1002/mus.24156

37. Oaklander AL, Herzog ZD, Downs HM, Klein MM. Objective evidence that small-fiber polyneuropathy underlies some illnesses currently labeled as fibromyalgia. Pain. 2013;154(11):2310-2316. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.001

38. Serrador JM. Diagnosis of late-stage, early-onset, small-fiber polyneuropathy. Defense Technical Information Center. December 1, 2019. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1094831

39. Lodahl M, Treister R, Oaklander AL. Specific symptoms may discriminate between fibromyalgia patients with vs without objective test evidence of small-fiber polyneuropathy. Pain Rep. 2018;3(1):e633. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000633

40. Sastre A, Cook MR. Autonomic dysfunction in Gulf War veterans. Defense Technical Information Center. April 1, 2004. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA429525

41. Little AA, Albers JW. Clinical description of toxic neuropathies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2015;131:253-296. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62627-1.00015-9

42. Faber CG, Hoeijmakers JGJ, Ahn HS, et al. Gain of function NaV1.7 mutations in idiopathic small fiber neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(1):26-39.

Pigmenting Purpuric Dermatoses: Striking But Not a Manifestation of COVID-19 Infection

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are characterized by petechiae, dusky macules representative of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and dermal hemosiderin, and purpura generally localized to the lower extremities. They typically represent a spectrum of lymphocytic capillaritis, variable erythrocyte extravasation from papillary dermal blood vessels, and deposition of hemosiderin, yielding the classic red to orange to golden-brown findings on gross examination. Clinical overlap exists, but variants include Schamberg disease (SD), Majocchi purpura, Gougerot-Blum purpura, eczematoid purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis (DK), and lichen aureus.1 Other forms are rarer, including linear, granulomatous, quadrantic, transitory, and familial variants. It remains controversial whether PPD may precede or have an association with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.2 Dermoscopy usually shows copper-red pigmentation in the background, oval red dots, linear vessels, brown globules, and follicular openings. Although these findings may be useful in PPD diagnosis, they are not applicable in differentiating among the variants.

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses can easily be mistaken for stasis dermatitis or cellulitis, as these may occur concomitantly or in populations at risk for all 3 conditions, such as women older than 50 years with recent trauma or infection in the affected area. Tissue biopsy and clinical laboratory evaluation may be required to differentiate between PPD from leukocytoclastic vasculitis or the myriad causes of retiform purpura. Importantly, clinicians also should differentiate PPD from the purpuric eruptions of the lower extremities associated with COVID-19 infection.

Pigmented Purpuric Dermatoses

Schamberg Disease—In 1901, Jay Frank Schamberg, a distinguished professor of dermatology in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, described “a peculiar progressive pigmentary disease of the skin” in a 15-year-old adolescent boy.3 Schamberg disease is the most common PPD, characterized by pruritic spots resembling cayenne pepper (Figure 1) with orange-brown pigmented macules on the legs and feet.4 Although platelet dysfunction, coagulation deficiencies, or dermal atrophy may contribute to hemorrhaging that manifests as petechiae or ecchymoses, SD typically is not associated with any laboratory abnormalities, and petechial eruption is not widespread.5 Capillary fragility can be assessed by the tourniquet test, in which pressure is applied to the forearm with a blood pressure cuff inflated between systolic and diastolic blood pressure for 5 to 10 minutes. Upon removing the cuff, a positive test is indicated by 15 or more petechiae in an area 5 cm in diameter due to poor platelet function. A positive result may be seen in SD.6

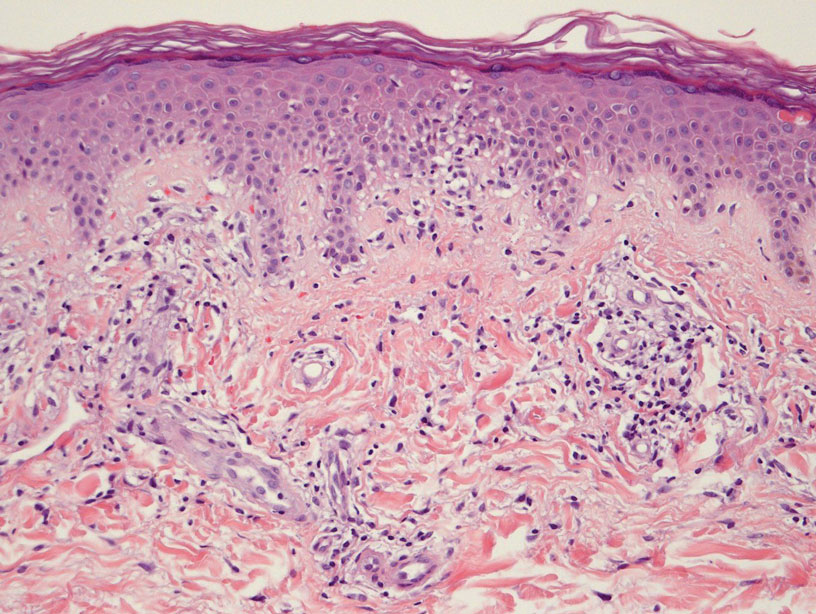

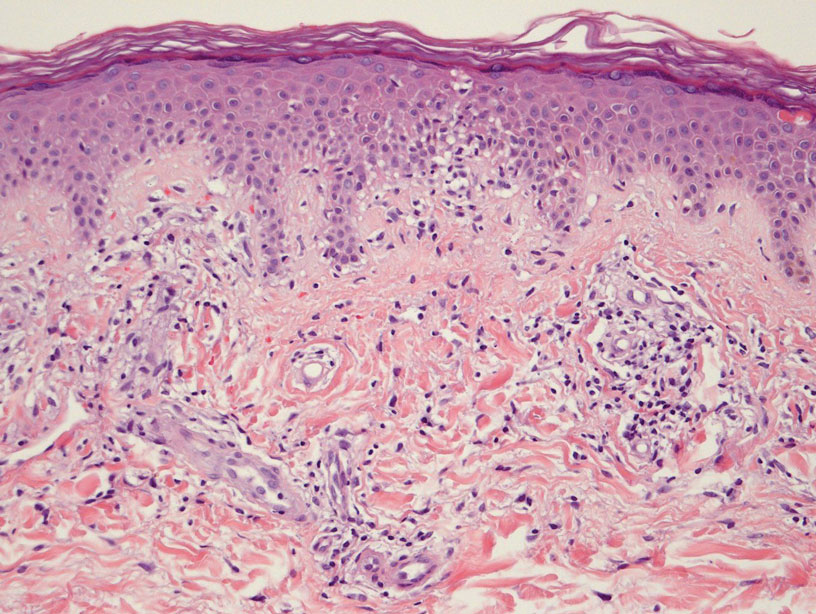

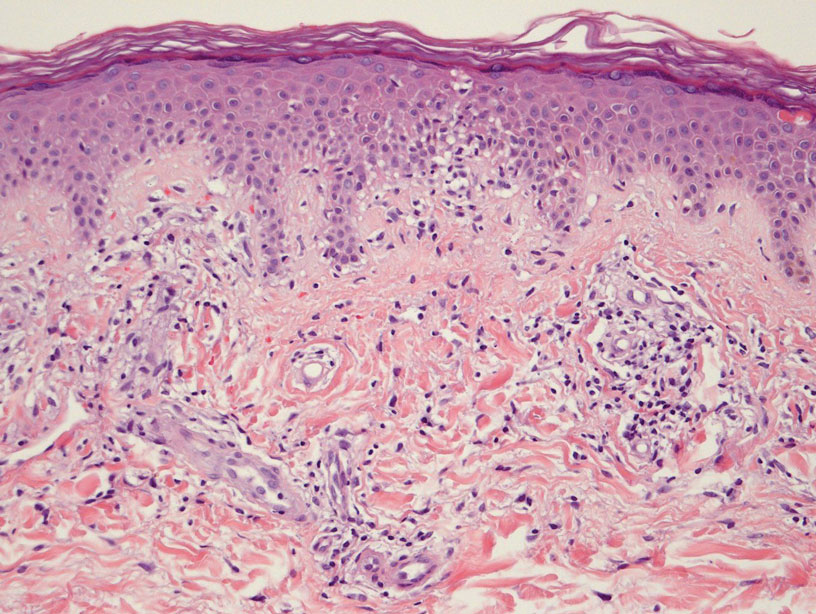

Histologically, SD is characterized by patchy parakeratosis, mild spongiosis of the stratum Malpighi, and lymphoid capillaritis (Figure 2).7 In addition to CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, CD1a+, and CD36+ lymphocytes, histology also may contain dendritic cells and cellular adhesion molecules (intercellular adhesion molecule 1, epithelial cell adhesion molecule 1) within the superficial perivascular infiltrate.8 There is no definitive therapy, but first-line interventions include emollients, topical steroids, and oral antihistamines. Nonpharmacologic management includes compression or support stockings, elevation of the lower extremities, and avoidance of offending medications (if identifiable).1

Majocchi Purpura—Domenico Majocchi was a renowned Italian dermatologist who described an entity in 1898 that he called purpura annularis telangiectodes, now also known as Majocchi purpura.9 It is more common in females, young adults, and children. Majocchi purpura has rarely been reported in families with a possible autosomal-dominant inheritance.10 Typically, bluish-red annular macules with central atrophy surrounded by hyperpigmentation may be seen on the lower extremities, potentially extending to the upper extremities.1 Treatment of Majocchi purpura remains a challenge but may respond to narrowband UVB phototherapy. Emollients and topical steroids also are used as first-line treatments. Biopsy demonstrates telangiectasia, pericapillary infiltration of mononuclear lymphocytes, and papillary dermal hemosiderin.11

Gougerot-Blum Purpura—In 1925, French dermatologists Henri Gougerot and Paul Blum described a pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis known as Gougerot-Blum purpura,12 a rare PPD characterized by lichenoid papules that eventually coalesce into plaques of various colors, along with red-brown hyperpigmentation.4 As with other PPD variants, the legs are most involved, with rare extension to the trunk or thighs. The plaques may resemble and be mistaken for Kaposi sarcoma, cutaneous vasculitis, traumatic purpura, or mycosis fungoides. Dermoscopic examination reveals small, polygonal or round, red dots underlying brown scaly patches.13 Gougerot-Blum purpura is found more commonly in adult men and rarely affects children.4 Histologically, a lichenoid and superficial perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and macrophages is seen. Various therapies have been described, including topical steroids, antihistamines, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, and cyclosporin A.14

Eczematoid Purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis—In 1949, Greek dermatologists Christopher Doucas and John Kapetanakis observed several cases of purpuric dermatosis similar in form to the “pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis” of Gougerot-Blum purpura12 and to the “progressive pigmentary dermatitis” of Schamberg disease.3 After observing a gradual disappearance of the classic yellow color from hemosiderin deposition, Doucas and Kapetanakis described a new bright red eruption with lichenification.15 Eczematoid purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis is rare and predominantly seen in middle-aged males. Hyperpigmented or dark brown macules may develop bilaterally on the legs, progressing to the thighs and upper extremities. Unlike the other types of PPD, DK is extensive and severely pruritic.4

Although most PPD can be drug induced, DK has shown the greatest tendency for pruritic erythematous plaques following drug usage including but not limited to amlodipine, aspirin, acetaminophen, thiamine, interferon alfa, chlordiazepoxide, and isotretinoin. Additionally, DK has been associated with a contact allergy to clothing dyes and rubber.4 On histology, epidermal spongiosis may be seen, correlating with the eczematoid clinical findings. Spontaneous remission also is more common compared to the other PPDs. Treatment consists of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.16

Lichen Aureus—Lichen aureus was first observed by the dermatologist R.H. Martin in 1958.17 It is clinically characterized by closely aggregated purpuric papules with a distinctive golden-brown color more often localized to the lower extremities and sometimes in a dermatomal distribution. Lichen aureus affects males and females equally, and similar to Majocchi purpura can be seen in children.4 Histopathologic examination reveals a prominent lichenoid plus superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, extravasated erythrocytes, papillary dermal edema, hemosiderophages, and an unaffected epidermis. In rare cases, perineural infiltrates may be seen. Topical steroids usually are ineffective in lichen aureus treatment, but responses to psoralen plus UVA therapy also have been noted.17

Differential Diagnosis

COVID-19–Related Cutaneous Changes—Because COVID-19–related pathology is now a common differential diagnosis for many cutaneous eruptions, one must be mindful of the possibility for patients to have PPD, cutaneous changes from underlying COVID-19, or both.18 The microvascular changes from COVID-19 infection can be variable.19 Besides the presence of erythema along a distal digit, manifestations can include reticulated dusky erythema mimicking livedoid vasculopathy or inflammatory purpura.19

Retiform Purpura—Retiform purpura may occur in the setting of microvascular occlusion and can represent the pattern of underlying dermal vasculature. It is nonblanching and typically stellate or branching.20 The microvascular occlusion may be a result of hypercoagulability or may be secondary to cutaneous vasculitis, resulting in thrombosis and subsequent vascular occlusion.21 There are many reasons for hypercoagulability in retiform purpura, including disseminated intravascular coagulation in the setting of COVID-19 infection.22 The treatment of retiform purpura is aimed at alleviating the underlying cause and providing symptomatic relief. Conversely, the PPDs generally are benign and require minimal workup.

Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis—The hallmark of leukocytoclastic vasculitis is palpable purpura, often appearing as nonblanchable papules, typically in a dependent distribution such as the lower extremities (Figure 3). Although it primarily affects children, Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a type of leukocytoclastic vasculitis with lesions potentially similar in appearance to those of PPD.23 Palpable purpura may be painful and may ulcerate but rarely is pruritic. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis represents perivascular infiltrates composed of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and occasionally eosinophils, along with karyorrhexis, luminal fibrin, and fibrinoid degeneration of blood vessel walls, often resulting from immune complex deposition. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may affect blood vessels of any size and requires further clinical and laboratory evaluation for infection (including COVID-19), hypercoagulability, autoimmune disease, or medication-related reactions.24

Stasis Dermatitis—Stasis dermatitis, a chronic inflammatory condition stemming from retrograde venous flow due to incompetent venous valves, mimics PPD. Stasis dermatitis initially appears as demarcated erythematous plaques, fissures, and scaling of the lower legs bilaterally, usually involving the medial malleolus.25 With time, the affected region develops overlying brawny hyperpigmentation and fibrosis (Figure 4). Pruritus or pain are common features, while fissures and superficial erosions may heal and recur, leading to lichenification.

Although both commonly appear on the lower extremities, duplex ultrasonography may be helpful to distinguish PPDs from stasis dermatitis since the latter occurs in the context of chronic venous insufficiency, varicose veins, soft tissue edema, and lymphedema.25 Additionally, pruritus, lichenification, and edema often are not seen in most PPD variants, although stasis dermatitis and PPD may occur in tandem. Conservative treatment involves elevation of the extremities, compression, and topical steroids for symptomatic relief.

Cellulitis—The key characteristics of cellulitis are redness, swelling, warmth, tenderness, fever, and leukocytosis. A history of trauma, such as a prior break in the skin, and pain in the affected area suggest cellulitis. Several skin conditions present similarly to cellulitis, including PPD, and thus approximately 30% of cases are misdiagnosed.26 Cellulitis rarely presents in a bilateral or diffusely scattered pattern as seen in PPDs. Rather, it is unilateral with smooth indistinct borders. Variables suggestive of cellulitis include immunosuppression, rapid progression, and previous occurrences. Hyperpigmented plaques or thickening of the skin are more indicative of a chronic process such as stasis dermatitis or lipodermatosclerosis rather than acute cellulitis. Purpura is not a typical finding in most cases of soft tissue cellulitis. Treatment may be case specific depending on severity, presence or absence of sepsis, findings on blood cultures, or other pathologic evaluation. Antibiotics are directed to the causative organism, typically Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species, although coverage against various gram-negative organisms may be indicated.27

Caution With Teledermatology