User login

Family-involved interventions reduce postoperative delirium

Background: Postoperative delirium is common in older patients undergoing surgery and often leads to complications including longer length of stay (LOS), increased mortality, functional decline, and dementia. The volunteer-based Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) is one of the most widely implemented prevention tools to reduce POD; however, different cultures may not use volunteers in their hospital systems.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: West China Hospital in Chengdu.

Synopsis: This Chinese-based clinical trial evaluated 281 patients aged 70 years or older who underwent elective surgery and were randomized to either t-HELP units or usual-care units. t-HELP patients received three universal protocols that included family-driven interventions of orientation, therapeutic activities, and early mobilization protocols, as well as targeted protocols based on delirium risk factors, while control participants received usual nursing care. The incidence of POD was significantly reduced in the t-HELP group, compared with the control group (2.6% vs. 19.4%), which was also associated with a shorter LOS. Patients were also noted to have less cognitive and functional decline that was sustained after discharge.

Bottom line: For hospitals that do not use volunteers in delirium prevention, involving family appears to be effective in reducing POD and maintaining physical and cognitive function post operatively.

Citation: Wang YY et al. Effect of the Tailored, Family-Involved Hospital Elder Life Program on postoperative delirium and function in older adults: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Oct 21. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4446.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: Postoperative delirium is common in older patients undergoing surgery and often leads to complications including longer length of stay (LOS), increased mortality, functional decline, and dementia. The volunteer-based Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) is one of the most widely implemented prevention tools to reduce POD; however, different cultures may not use volunteers in their hospital systems.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: West China Hospital in Chengdu.

Synopsis: This Chinese-based clinical trial evaluated 281 patients aged 70 years or older who underwent elective surgery and were randomized to either t-HELP units or usual-care units. t-HELP patients received three universal protocols that included family-driven interventions of orientation, therapeutic activities, and early mobilization protocols, as well as targeted protocols based on delirium risk factors, while control participants received usual nursing care. The incidence of POD was significantly reduced in the t-HELP group, compared with the control group (2.6% vs. 19.4%), which was also associated with a shorter LOS. Patients were also noted to have less cognitive and functional decline that was sustained after discharge.

Bottom line: For hospitals that do not use volunteers in delirium prevention, involving family appears to be effective in reducing POD and maintaining physical and cognitive function post operatively.

Citation: Wang YY et al. Effect of the Tailored, Family-Involved Hospital Elder Life Program on postoperative delirium and function in older adults: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Oct 21. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4446.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: Postoperative delirium is common in older patients undergoing surgery and often leads to complications including longer length of stay (LOS), increased mortality, functional decline, and dementia. The volunteer-based Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) is one of the most widely implemented prevention tools to reduce POD; however, different cultures may not use volunteers in their hospital systems.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: West China Hospital in Chengdu.

Synopsis: This Chinese-based clinical trial evaluated 281 patients aged 70 years or older who underwent elective surgery and were randomized to either t-HELP units or usual-care units. t-HELP patients received three universal protocols that included family-driven interventions of orientation, therapeutic activities, and early mobilization protocols, as well as targeted protocols based on delirium risk factors, while control participants received usual nursing care. The incidence of POD was significantly reduced in the t-HELP group, compared with the control group (2.6% vs. 19.4%), which was also associated with a shorter LOS. Patients were also noted to have less cognitive and functional decline that was sustained after discharge.

Bottom line: For hospitals that do not use volunteers in delirium prevention, involving family appears to be effective in reducing POD and maintaining physical and cognitive function post operatively.

Citation: Wang YY et al. Effect of the Tailored, Family-Involved Hospital Elder Life Program on postoperative delirium and function in older adults: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Oct 21. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4446.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Depression screening after ACS does not change outcomes

Background: Depression after ACS is common and is associated with increased mortality. Professional societies have recommended routine depression screening in these patients; however, this has not been consistently implemented because there is a lack of data to support routine screening.

Study design: Multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Four geographically diverse health systems in the United States.

Synopsis: In the CODIACS-QoL trial, 1,500 patients were randomized to three groups within 12 months of documented ACS: depression screening with notification to primary care and treatment, screening and notification to primary care, and no screening. Only 7.7% of the patients in the screen, notify, and treat group and 6.6% of screen and notify group screened positive for depression. There were no differences for the primary outcome of quality-adjusted life-years or the secondary outcome of depression-free days between groups. Additionally, there was no difference in mortality or patient-reported harms of screening between groups. The study excluded patients who already had a history of depression, psychiatric history, or other severe life-threatening medical conditions, which may have affected the outcomes.

Depression remains a substantial factor in coronary disease and quality of life; however, systematic depression screening appears to have limited population-level benefits.

Bottom line: Systematic depression screening with or without treatment offerings did not alter quality of life, depression-free days, or mortality in patients with ACS.

Citation: Kronish IM et al. Effect of depression screening after acute coronary syndrome on quality of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):45-53.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: Depression after ACS is common and is associated with increased mortality. Professional societies have recommended routine depression screening in these patients; however, this has not been consistently implemented because there is a lack of data to support routine screening.

Study design: Multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Four geographically diverse health systems in the United States.

Synopsis: In the CODIACS-QoL trial, 1,500 patients were randomized to three groups within 12 months of documented ACS: depression screening with notification to primary care and treatment, screening and notification to primary care, and no screening. Only 7.7% of the patients in the screen, notify, and treat group and 6.6% of screen and notify group screened positive for depression. There were no differences for the primary outcome of quality-adjusted life-years or the secondary outcome of depression-free days between groups. Additionally, there was no difference in mortality or patient-reported harms of screening between groups. The study excluded patients who already had a history of depression, psychiatric history, or other severe life-threatening medical conditions, which may have affected the outcomes.

Depression remains a substantial factor in coronary disease and quality of life; however, systematic depression screening appears to have limited population-level benefits.

Bottom line: Systematic depression screening with or without treatment offerings did not alter quality of life, depression-free days, or mortality in patients with ACS.

Citation: Kronish IM et al. Effect of depression screening after acute coronary syndrome on quality of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):45-53.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: Depression after ACS is common and is associated with increased mortality. Professional societies have recommended routine depression screening in these patients; however, this has not been consistently implemented because there is a lack of data to support routine screening.

Study design: Multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Four geographically diverse health systems in the United States.

Synopsis: In the CODIACS-QoL trial, 1,500 patients were randomized to three groups within 12 months of documented ACS: depression screening with notification to primary care and treatment, screening and notification to primary care, and no screening. Only 7.7% of the patients in the screen, notify, and treat group and 6.6% of screen and notify group screened positive for depression. There were no differences for the primary outcome of quality-adjusted life-years or the secondary outcome of depression-free days between groups. Additionally, there was no difference in mortality or patient-reported harms of screening between groups. The study excluded patients who already had a history of depression, psychiatric history, or other severe life-threatening medical conditions, which may have affected the outcomes.

Depression remains a substantial factor in coronary disease and quality of life; however, systematic depression screening appears to have limited population-level benefits.

Bottom line: Systematic depression screening with or without treatment offerings did not alter quality of life, depression-free days, or mortality in patients with ACS.

Citation: Kronish IM et al. Effect of depression screening after acute coronary syndrome on quality of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):45-53.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Increasing inpatient attending supervision does not decrease medical errors

Clinical question: What is the effect of increasing attending physician supervision on a resident inpatient team for both patient safety and education?

Background: Residents need autonomy to help develop their clinical skills and to gain competence to practice independently; however, there is rising concern that increased supervision is needed for patient safety.

Study Design: Randomized, crossover clinical trial.

Setting: 1,100-bed academic medical center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Synopsis: Twenty-two attending physicians participated in the study over 44 2-week teaching blocks with a total of 1,259 patient hospitalizations on the general medicine teaching service. In the intervention arm, attendings were present during work rounds; in the control arm, attendings discussed established patients with the resident via card flip. New patients were discussed at the bedside in both arms. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of medical errors or patient safety events between the two groups. Residents in the intervention group, however, felt less efficient and autonomous and were less able to make independent decisions. Limitations include this being a single-center study at a program emphasizing resident autonomy and therefore may limit generalizability. Current literature on supervision and patient safety has variable results. This study suggests that increasing attending supervision may not increase patient safety, but may negatively affect resident education and autonomy.

Bottom line: Attending physician presence on work rounds does not improve patient safety and may have deleterious effects on resident education.

Citation: Finn KM et al. Effect of increased inpatient attending physician supervision on medical errors, patient safety, and resident education. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):925-59

Dr. Ciarkowski is clinical instructor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: What is the effect of increasing attending physician supervision on a resident inpatient team for both patient safety and education?

Background: Residents need autonomy to help develop their clinical skills and to gain competence to practice independently; however, there is rising concern that increased supervision is needed for patient safety.

Study Design: Randomized, crossover clinical trial.

Setting: 1,100-bed academic medical center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Synopsis: Twenty-two attending physicians participated in the study over 44 2-week teaching blocks with a total of 1,259 patient hospitalizations on the general medicine teaching service. In the intervention arm, attendings were present during work rounds; in the control arm, attendings discussed established patients with the resident via card flip. New patients were discussed at the bedside in both arms. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of medical errors or patient safety events between the two groups. Residents in the intervention group, however, felt less efficient and autonomous and were less able to make independent decisions. Limitations include this being a single-center study at a program emphasizing resident autonomy and therefore may limit generalizability. Current literature on supervision and patient safety has variable results. This study suggests that increasing attending supervision may not increase patient safety, but may negatively affect resident education and autonomy.

Bottom line: Attending physician presence on work rounds does not improve patient safety and may have deleterious effects on resident education.

Citation: Finn KM et al. Effect of increased inpatient attending physician supervision on medical errors, patient safety, and resident education. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):925-59

Dr. Ciarkowski is clinical instructor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: What is the effect of increasing attending physician supervision on a resident inpatient team for both patient safety and education?

Background: Residents need autonomy to help develop their clinical skills and to gain competence to practice independently; however, there is rising concern that increased supervision is needed for patient safety.

Study Design: Randomized, crossover clinical trial.

Setting: 1,100-bed academic medical center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Synopsis: Twenty-two attending physicians participated in the study over 44 2-week teaching blocks with a total of 1,259 patient hospitalizations on the general medicine teaching service. In the intervention arm, attendings were present during work rounds; in the control arm, attendings discussed established patients with the resident via card flip. New patients were discussed at the bedside in both arms. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of medical errors or patient safety events between the two groups. Residents in the intervention group, however, felt less efficient and autonomous and were less able to make independent decisions. Limitations include this being a single-center study at a program emphasizing resident autonomy and therefore may limit generalizability. Current literature on supervision and patient safety has variable results. This study suggests that increasing attending supervision may not increase patient safety, but may negatively affect resident education and autonomy.

Bottom line: Attending physician presence on work rounds does not improve patient safety and may have deleterious effects on resident education.

Citation: Finn KM et al. Effect of increased inpatient attending physician supervision on medical errors, patient safety, and resident education. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):925-59

Dr. Ciarkowski is clinical instructor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Decrease in Inpatient Telemetry Utilization Through a System-Wide Electronic Health Record Change and a Multifaceted Hospitalist Intervention

Wasteful care may account for between 21% and 34% of the United States’ $3.2 trillion in annual healthcare expenditures, making it a prime target for cost-saving initiatives.1,2 Telemetry is a target for value improvement strategies because telemetry is overutilized, rarely leads to a change in management, and has associated guidelines on appropriate use.3-10 Telemetry use has been a focus of the Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals since 2014, and it is also a focus of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Choosing Wisely® campaign.11-13

Previous initiatives have evaluated how changes to telemetry orders or education and feedback affect telemetry use. Few studies have compared a system-wide electronic health record (EHR) approach to a multifaceted intervention. In seeking to address this gap, we adapted published guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA) and incorporated them into our EHR ordering process.3 Simultaneously, we implemented a multifaceted quality improvement initiative and compared this combined program’s effectiveness to that of the EHR approach alone.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

We performed a 2-group observational pre- to postintervention study at University of Utah Health. Hospital encounters of patients 18 years and older who had at least 1 inpatient acute care, nonintensive care unit (ICU) room charge and an admission date between January 1, 2014, and July 31, 2016, were included. Patient encounters with missing encounter-level covariates, such as case mix index (CMI) or attending provider identification, were excluded. The Institutional Review Board classified this project as quality improvement and did not require review and oversight.

Intervention

On July 6, 2015, our Epic (Epic Systems Corporation, Madison, WI) EHR telemetry order was modified to discourage unnecessary telemetry monitoring. The new order required providers ordering telemetry to choose a clinical indication and select a duration for monitoring, after which the order would expire and require physician renewal or discontinuation. These were the only changes that occurred for nonhospitalist providers. The nonhospitalist group included all admitting providers who were not hospitalists. This group included neurology (6.98%); cardiology (8.13%); other medical specialties such as pulmonology, hematology, and oncology (21.30%); cardiothoracic surgery (3.72%); orthopedic surgery (14.84%); general surgery (11.11%); neurosurgery (11.07%); and other surgical specialties, including urology, transplant, vascular surgery, and plastics (16.68%).

Between January 2015 and June 2015, we implemented a multicomponent program among our hospitalist service. The hospitalist service is composed of 4 teams with internal medicine residents and 2 teams with advanced practice providers, all staffed by academic hospitalists. Our program was composed of 5 elements, all of which were made before the hospital-wide changes to electronic telemetry orders and maintained throughout the study period, as follows: (1) a single provider education session reviewing available evidence (eg, AHA guidelines, Choosing Wisely® campaign), (2) removal of the telemetry order from hospitalist admission order set on March 23, 2015, (3) inclusion of telemetry discussion in the hospitalist group’s daily “Rounding Checklist,”14 (4) monthly feedback provided as part of hospitalist group meetings, and (5) a financial incentive, awarded to the division (no individual provider payment) if performance targets were met. See supplementary Appendix (“Implementation Manual”) for further details.

Data Source

We obtained data on patient age, gender, Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Group, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), CMI, admitting unit, attending physician, admission and discharge dates, length of stay (LOS), 30-day readmission, bed charge (telemetry or nontelemetry), ICU stay, and inpatient mortality from the enterprise data warehouse. Telemetry days were determined through room billing charges, which are assigned based on the presence or absence of an active telemetry order at midnight. Code events came from a log kept by the hospital telephone operator, who is responsible for sending out all calls to the code team. Code event data were available starting July 19, 2014.

Measures

Our primary outcome was the percentage of hospital days that had telemetry charges for individual patients. All billed telemetry days on acute care floors were included regardless of admission status (inpatient vs observation), service, indication, or ordering provider. Secondary outcomes were inpatient mortality, escalation of care, code event rates, and appropriate telemetry utilization rates. Escalation of care was defined as transfer to an ICU after initially being admitted to an acute care floor. The code event rate was defined as the ratio of the number of code team activations to the number of patient days. Appropriate telemetry utilization rates were determined via chart review, as detailed below.

In order to evaluate changes in appropriateness of telemetry monitoring, 4 of the authors who are internal medicine physicians (KE, CC, JC, DG) performed chart reviews of 25 randomly selected patients in each group (hospitalist and nonhospitalist) before and after the intervention who received at least 1 day of telemetry monitoring. Each reviewer was provided a key based on AHA guidelines for monitoring indications and associated maximum allowable durations.3 Chart reviews were performed to determine the indication (if any) for monitoring, as well as the number of days that were indicated. The number of indicated days was compared to the number of telemetry days the patient received to determine the overall proportion of days that were indicated (“Telemetry appropriateness per visit”). Three reviewers (KE, AR, CC) also evaluated 100 patients on the hospitalist service after the intervention who did not receive any telemetry monitoring to evaluate whether patients with indications for telemetry monitoring were not receiving it after the intervention. For patients who had a possible indication, the indication was classified as Class I (“Cardiac monitoring is indicated in most, if not all, patients in this group”) or Class II (“Cardiac monitoring may be of benefit in some patients but is not considered essential for all patients”).3

Adjustment Variables

To account for differences in patient characteristics between hospitalist and nonhospitalist groups, we included age, gender, CMI, and CCI in statistical models. CCI was calculated according to the algorithm specified by Quan et al.15 using all patient diagnoses from previous visits and the index visit identified from the facility billing system.

Statistical Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics for study outcomes and visit characteristics for hospitalist and nonhospitalist visits for pre- and postintervention periods. Descriptive statistics were expressed as n (%) for categorical patient characteristics and outcome variables. For continuous patient characteristics, we expressed the variability of individual observations as the mean ± the standard deviation. For continuous outcomes, we expressed the precision of the mean estimates using standard error. Telemetry utilization per visit was weighted by the number of total acute care days per visit. Telemetry appropriateness per visit was weighted by the number of telemetry days per visit. Patients who did not receive any telemetry monitoring were included in the analysis and noted to have 0 telemetry days. All patients had at least 1 acute care day. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests, and continuous variables were compared using t tests. Code event rates were compared using the binomial probability mid-p exact test for person-time data.16

We fitted generalized linear regression models using generalized estimating equations to evaluate the relative change in outcomes of interest in the postintervention period compared with the preintervention period after adjusting for study covariates. The models included study group (hospitalist and nonhospitalist), time period (pre- and postintervention), an interaction term between study group and time period, and study covariates (age, gender, CMI, and CCI). The models were defined using a binomial distributional assumption and logit link function for mortality, escalation of care, and whether patients had at least 1 telemetry day. A gamma distributional assumption and log link function were used for LOS, telemetry acute care days per visit, and total acute care days per visit. A negative binomial distributional assumption and log link function were used for telemetry utilization and telemetry appropriateness. We used the log of the acute care days as an offset for telemetry utilization and the log of the telemetry days per visit as an offset for telemetry appropriateness. An exchangeable working correlation matrix was used to account for physician-level clustering for all outcomes. Intervention effects, representing the difference in odds for categorical variables and in amount for continuous variables, were calculated as exponentiation of the beta parameters for the covariate minus 1.

P values <.05 were considered significant. We used SAS version 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for data analysis.

RESULTS

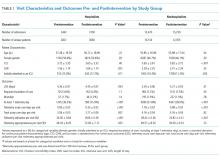

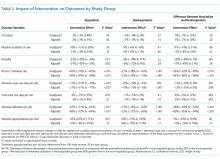

The percent of patients who had any telemetry charges decreased from 36.2% to 15.9% (P < .001) in the hospitalist group and from 31.8% to 28.0% in the nonhospitalist group (P < .001; Table 1). Rates of code events did not change over time (P = .9).

In the randomly selected sample of patients pre- and postintervention who received telemetry monitoring, there was an increase in telemetry appropriateness on the hospitalist service (46% to 72%, P = .025; Table 1). In the nonhospitalist group, appropriate telemetry utilization did not change significantly. Of the 100 randomly selected patients in the hospitalist group after the intervention who did not receive telemetry, no patient had an AHA Class I indication, and only 4 patients had a Class II indication.3,17

DISCUSSION

In this study, implementing a change in the EHR telemetry order produced reductions in telemetry days. However, when combined with a multicomponent program including education, audit and feedback, financial incentives, and changes to remove telemetry orders from admission orders sets, an even more marked improvement was seen. Neither intervention reduced LOS, increased code event rates, or increased rates of escalation of care.

Prior studies have evaluated interventions to reduce unnecessary telemetry monitoring with varying degrees of success. The most successful EHR intervention to date, from Dressler et al.,18 achieved a 70% reduction in overall telemetry use by integrating the AHA guidelines into their EHR and incorporating nursing discontinuation guidelines to ensure that telemetry discontinuation was both safe and timely. Other studies using stewardship approaches and standardized protocols have been less successful.19,20 One study utilizing a multidisciplinary approach but not including an EHR component showed modest improvements in telemetry.21

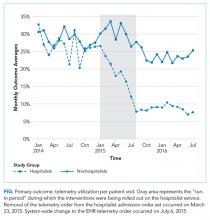

Although we are unable to differentiate the exact effect of each component of the intervention, we did note an immediate decrease in telemetry orders after removing the telemetry order from our admission order set, a trend that was magnified after the addition of broader EHR changes (Figure 1). Important additional contributors to our success seem to have been the standardization of rounds to include daily discussion of telemetry and the provision of routine feedback. We cannot discern whether other components of our program (such as the financial incentives) contributed more or less to our program, though the sum of these interventions produced an overall program that required substantial buy in and sustained focus from the hospitalist group. The importance of the hospitalist program is highlighted by the relatively large differences in improvement compared with the nonhospitalist group.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single center, which may limit its generalizability. Second, the intervention was multifaceted, diminishing our ability to discern which aspects beyond the system-wide change in the telemetry order were most responsible for the observed effect among hospitalists. Third, we are unable to fully account for baseline differences in telemetry utilization between hospitalist and nonhospitalist groups. It is likely that different services utilize telemetry monitoring in different ways, and the hospitalist group may have been more aware of the existing guidelines for monitoring prior to the intervention. Furthermore, we had a limited sample size for the chart audits, which reduced the available statistical power for determining changes in the appropriateness of telemetry utilization. Additionally, because internal medicine residents rotate through various services, it is possible that the education they received on their hospitalist rotation as part of our intervention had a spillover effect in the nonhospitalist group. However, any effect should have decreased the difference between the groups. Lastly, although our postintervention time period was 1 year, we do not have data beyond that to monitor for sustainability of the results.

CONCLUSION

In this single-site study, combining EHR orders prompting physicians to choose a clinical indication and duration for monitoring with a broader program—including upstream changes in ordering as well as education, audit, and feedback—produced reductions in telemetry usage. Whether this reduction improves the appropriateness of telemetry utilization or reduces other effects of telemetry (eg, alert fatigue, calls for benign arrhythmias) cannot be discerned from our study. However, our results support the idea that multipronged approaches to telemetry use are most likely to produce improvements.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Frank Thomas for his assistance with process engineering and Mr. Andrew Wood for his routine provision of data. The statistical analysis was supported by the University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 5UL1TR001067-05 (formerly 8UL1TR000105 and UL1RR025764).

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

1. National Health Expenditure Fact Sheet. 2015; https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet.html. Accessed June 27, 2017.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-1516. PubMed

3. Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. PubMed

4. Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, et al. Update to Practice Standards for Electrocardiographic Monitoring in Hospital Settings: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(19):e273-e344. PubMed

5. Mohammad R, Shah S, Donath E, et al. Non-critical care telemetry and in-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes. J Electrocardiol. 2015;48(3):426-429. PubMed

6. Dhillon SK, Rachko M, Hanon S, Schweitzer P, Bergmann SR. Telemetry monitoring guidelines for efficient and safe delivery of cardiac rhythm monitoring to noncritical hospital inpatients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2009;8(3):125-126. PubMed

7. Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Evaluation of guidelines for the use of telemetry in the non-intensive-care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(1):51-55. PubMed

8. Estrada CA, Prasad NK, Rosman HS, Young MJ. Outcomes of patients hospitalized to a telemetry unit. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74(4):357-362. PubMed

9. Atzema C, Schull MJ, Borgundvaag B, Slaughter GR, Lee CK. ALARMED: adverse events in low-risk patients with chest pain receiving continuous electrocardiographic monitoring in the emergency department. A pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(1):62-67. PubMed

10. Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and cardiac arrest outcomes in 8,932 telemetry ward patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(6):647-652. PubMed

11. The Joint Commission 2017 National Patient Safety Goals https://www.jointcommission.org/hap_2017_npsgs/. Accessed on February 15, 2017.

12. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. The Joint Commission announces 2014 National Patient Safety Goal. Jt Comm Perspect. 2013;33(7):1, 3-4. PubMed

13. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

14. Yarbrough PM, Kukhareva PV, Horton D, Edholm K, Kawamoto K. Multifaceted intervention including education, rounding checklist implementation, cost feedback, and financial incentives reduces inpatient laboratory costs. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):348-354. PubMed

15. Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676-682. PubMed

16. Greenland S, Rothman KJ. Introduction to categorical statistics In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, eds. Modern Epidemiology. Vol 3. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008: 238-257.

17. Henriques-Forsythe MN, Ivonye CC, Jamched U, Kamuguisha LK, Olejeme KA, Onwuanyi AE. Is telemetry overused? Is it as helpful as thought? Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(6):368-372. PubMed

18. Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. PubMed

19. Boggan JC, Navar-Boggan AM, Patel V, Schulteis RD, Simel DL. Reductions in telemetry order duration do not reduce telemetry utilization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):795-796. PubMed

20. Cantillon DJ, Loy M, Burkle A, et al. Association Between Off-site Central Monitoring Using Standardized Cardiac Telemetry and Clinical Outcomes Among Non-Critically Ill Patients. JAMA. 2016;316(5):519-524. PubMed

21. Svec D, Ahuja N, Evans KH, et al. Hospitalist intervention for appropriate use of telemetry reduces length of stay and cost. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):627-632. PubMed

Wasteful care may account for between 21% and 34% of the United States’ $3.2 trillion in annual healthcare expenditures, making it a prime target for cost-saving initiatives.1,2 Telemetry is a target for value improvement strategies because telemetry is overutilized, rarely leads to a change in management, and has associated guidelines on appropriate use.3-10 Telemetry use has been a focus of the Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals since 2014, and it is also a focus of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Choosing Wisely® campaign.11-13

Previous initiatives have evaluated how changes to telemetry orders or education and feedback affect telemetry use. Few studies have compared a system-wide electronic health record (EHR) approach to a multifaceted intervention. In seeking to address this gap, we adapted published guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA) and incorporated them into our EHR ordering process.3 Simultaneously, we implemented a multifaceted quality improvement initiative and compared this combined program’s effectiveness to that of the EHR approach alone.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

We performed a 2-group observational pre- to postintervention study at University of Utah Health. Hospital encounters of patients 18 years and older who had at least 1 inpatient acute care, nonintensive care unit (ICU) room charge and an admission date between January 1, 2014, and July 31, 2016, were included. Patient encounters with missing encounter-level covariates, such as case mix index (CMI) or attending provider identification, were excluded. The Institutional Review Board classified this project as quality improvement and did not require review and oversight.

Intervention

On July 6, 2015, our Epic (Epic Systems Corporation, Madison, WI) EHR telemetry order was modified to discourage unnecessary telemetry monitoring. The new order required providers ordering telemetry to choose a clinical indication and select a duration for monitoring, after which the order would expire and require physician renewal or discontinuation. These were the only changes that occurred for nonhospitalist providers. The nonhospitalist group included all admitting providers who were not hospitalists. This group included neurology (6.98%); cardiology (8.13%); other medical specialties such as pulmonology, hematology, and oncology (21.30%); cardiothoracic surgery (3.72%); orthopedic surgery (14.84%); general surgery (11.11%); neurosurgery (11.07%); and other surgical specialties, including urology, transplant, vascular surgery, and plastics (16.68%).

Between January 2015 and June 2015, we implemented a multicomponent program among our hospitalist service. The hospitalist service is composed of 4 teams with internal medicine residents and 2 teams with advanced practice providers, all staffed by academic hospitalists. Our program was composed of 5 elements, all of which were made before the hospital-wide changes to electronic telemetry orders and maintained throughout the study period, as follows: (1) a single provider education session reviewing available evidence (eg, AHA guidelines, Choosing Wisely® campaign), (2) removal of the telemetry order from hospitalist admission order set on March 23, 2015, (3) inclusion of telemetry discussion in the hospitalist group’s daily “Rounding Checklist,”14 (4) monthly feedback provided as part of hospitalist group meetings, and (5) a financial incentive, awarded to the division (no individual provider payment) if performance targets were met. See supplementary Appendix (“Implementation Manual”) for further details.

Data Source

We obtained data on patient age, gender, Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Group, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), CMI, admitting unit, attending physician, admission and discharge dates, length of stay (LOS), 30-day readmission, bed charge (telemetry or nontelemetry), ICU stay, and inpatient mortality from the enterprise data warehouse. Telemetry days were determined through room billing charges, which are assigned based on the presence or absence of an active telemetry order at midnight. Code events came from a log kept by the hospital telephone operator, who is responsible for sending out all calls to the code team. Code event data were available starting July 19, 2014.

Measures

Our primary outcome was the percentage of hospital days that had telemetry charges for individual patients. All billed telemetry days on acute care floors were included regardless of admission status (inpatient vs observation), service, indication, or ordering provider. Secondary outcomes were inpatient mortality, escalation of care, code event rates, and appropriate telemetry utilization rates. Escalation of care was defined as transfer to an ICU after initially being admitted to an acute care floor. The code event rate was defined as the ratio of the number of code team activations to the number of patient days. Appropriate telemetry utilization rates were determined via chart review, as detailed below.

In order to evaluate changes in appropriateness of telemetry monitoring, 4 of the authors who are internal medicine physicians (KE, CC, JC, DG) performed chart reviews of 25 randomly selected patients in each group (hospitalist and nonhospitalist) before and after the intervention who received at least 1 day of telemetry monitoring. Each reviewer was provided a key based on AHA guidelines for monitoring indications and associated maximum allowable durations.3 Chart reviews were performed to determine the indication (if any) for monitoring, as well as the number of days that were indicated. The number of indicated days was compared to the number of telemetry days the patient received to determine the overall proportion of days that were indicated (“Telemetry appropriateness per visit”). Three reviewers (KE, AR, CC) also evaluated 100 patients on the hospitalist service after the intervention who did not receive any telemetry monitoring to evaluate whether patients with indications for telemetry monitoring were not receiving it after the intervention. For patients who had a possible indication, the indication was classified as Class I (“Cardiac monitoring is indicated in most, if not all, patients in this group”) or Class II (“Cardiac monitoring may be of benefit in some patients but is not considered essential for all patients”).3

Adjustment Variables

To account for differences in patient characteristics between hospitalist and nonhospitalist groups, we included age, gender, CMI, and CCI in statistical models. CCI was calculated according to the algorithm specified by Quan et al.15 using all patient diagnoses from previous visits and the index visit identified from the facility billing system.

Statistical Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics for study outcomes and visit characteristics for hospitalist and nonhospitalist visits for pre- and postintervention periods. Descriptive statistics were expressed as n (%) for categorical patient characteristics and outcome variables. For continuous patient characteristics, we expressed the variability of individual observations as the mean ± the standard deviation. For continuous outcomes, we expressed the precision of the mean estimates using standard error. Telemetry utilization per visit was weighted by the number of total acute care days per visit. Telemetry appropriateness per visit was weighted by the number of telemetry days per visit. Patients who did not receive any telemetry monitoring were included in the analysis and noted to have 0 telemetry days. All patients had at least 1 acute care day. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests, and continuous variables were compared using t tests. Code event rates were compared using the binomial probability mid-p exact test for person-time data.16

We fitted generalized linear regression models using generalized estimating equations to evaluate the relative change in outcomes of interest in the postintervention period compared with the preintervention period after adjusting for study covariates. The models included study group (hospitalist and nonhospitalist), time period (pre- and postintervention), an interaction term between study group and time period, and study covariates (age, gender, CMI, and CCI). The models were defined using a binomial distributional assumption and logit link function for mortality, escalation of care, and whether patients had at least 1 telemetry day. A gamma distributional assumption and log link function were used for LOS, telemetry acute care days per visit, and total acute care days per visit. A negative binomial distributional assumption and log link function were used for telemetry utilization and telemetry appropriateness. We used the log of the acute care days as an offset for telemetry utilization and the log of the telemetry days per visit as an offset for telemetry appropriateness. An exchangeable working correlation matrix was used to account for physician-level clustering for all outcomes. Intervention effects, representing the difference in odds for categorical variables and in amount for continuous variables, were calculated as exponentiation of the beta parameters for the covariate minus 1.

P values <.05 were considered significant. We used SAS version 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for data analysis.

RESULTS

The percent of patients who had any telemetry charges decreased from 36.2% to 15.9% (P < .001) in the hospitalist group and from 31.8% to 28.0% in the nonhospitalist group (P < .001; Table 1). Rates of code events did not change over time (P = .9).

In the randomly selected sample of patients pre- and postintervention who received telemetry monitoring, there was an increase in telemetry appropriateness on the hospitalist service (46% to 72%, P = .025; Table 1). In the nonhospitalist group, appropriate telemetry utilization did not change significantly. Of the 100 randomly selected patients in the hospitalist group after the intervention who did not receive telemetry, no patient had an AHA Class I indication, and only 4 patients had a Class II indication.3,17

DISCUSSION

In this study, implementing a change in the EHR telemetry order produced reductions in telemetry days. However, when combined with a multicomponent program including education, audit and feedback, financial incentives, and changes to remove telemetry orders from admission orders sets, an even more marked improvement was seen. Neither intervention reduced LOS, increased code event rates, or increased rates of escalation of care.

Prior studies have evaluated interventions to reduce unnecessary telemetry monitoring with varying degrees of success. The most successful EHR intervention to date, from Dressler et al.,18 achieved a 70% reduction in overall telemetry use by integrating the AHA guidelines into their EHR and incorporating nursing discontinuation guidelines to ensure that telemetry discontinuation was both safe and timely. Other studies using stewardship approaches and standardized protocols have been less successful.19,20 One study utilizing a multidisciplinary approach but not including an EHR component showed modest improvements in telemetry.21

Although we are unable to differentiate the exact effect of each component of the intervention, we did note an immediate decrease in telemetry orders after removing the telemetry order from our admission order set, a trend that was magnified after the addition of broader EHR changes (Figure 1). Important additional contributors to our success seem to have been the standardization of rounds to include daily discussion of telemetry and the provision of routine feedback. We cannot discern whether other components of our program (such as the financial incentives) contributed more or less to our program, though the sum of these interventions produced an overall program that required substantial buy in and sustained focus from the hospitalist group. The importance of the hospitalist program is highlighted by the relatively large differences in improvement compared with the nonhospitalist group.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single center, which may limit its generalizability. Second, the intervention was multifaceted, diminishing our ability to discern which aspects beyond the system-wide change in the telemetry order were most responsible for the observed effect among hospitalists. Third, we are unable to fully account for baseline differences in telemetry utilization between hospitalist and nonhospitalist groups. It is likely that different services utilize telemetry monitoring in different ways, and the hospitalist group may have been more aware of the existing guidelines for monitoring prior to the intervention. Furthermore, we had a limited sample size for the chart audits, which reduced the available statistical power for determining changes in the appropriateness of telemetry utilization. Additionally, because internal medicine residents rotate through various services, it is possible that the education they received on their hospitalist rotation as part of our intervention had a spillover effect in the nonhospitalist group. However, any effect should have decreased the difference between the groups. Lastly, although our postintervention time period was 1 year, we do not have data beyond that to monitor for sustainability of the results.

CONCLUSION

In this single-site study, combining EHR orders prompting physicians to choose a clinical indication and duration for monitoring with a broader program—including upstream changes in ordering as well as education, audit, and feedback—produced reductions in telemetry usage. Whether this reduction improves the appropriateness of telemetry utilization or reduces other effects of telemetry (eg, alert fatigue, calls for benign arrhythmias) cannot be discerned from our study. However, our results support the idea that multipronged approaches to telemetry use are most likely to produce improvements.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Frank Thomas for his assistance with process engineering and Mr. Andrew Wood for his routine provision of data. The statistical analysis was supported by the University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 5UL1TR001067-05 (formerly 8UL1TR000105 and UL1RR025764).

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Wasteful care may account for between 21% and 34% of the United States’ $3.2 trillion in annual healthcare expenditures, making it a prime target for cost-saving initiatives.1,2 Telemetry is a target for value improvement strategies because telemetry is overutilized, rarely leads to a change in management, and has associated guidelines on appropriate use.3-10 Telemetry use has been a focus of the Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals since 2014, and it is also a focus of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Choosing Wisely® campaign.11-13

Previous initiatives have evaluated how changes to telemetry orders or education and feedback affect telemetry use. Few studies have compared a system-wide electronic health record (EHR) approach to a multifaceted intervention. In seeking to address this gap, we adapted published guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA) and incorporated them into our EHR ordering process.3 Simultaneously, we implemented a multifaceted quality improvement initiative and compared this combined program’s effectiveness to that of the EHR approach alone.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

We performed a 2-group observational pre- to postintervention study at University of Utah Health. Hospital encounters of patients 18 years and older who had at least 1 inpatient acute care, nonintensive care unit (ICU) room charge and an admission date between January 1, 2014, and July 31, 2016, were included. Patient encounters with missing encounter-level covariates, such as case mix index (CMI) or attending provider identification, were excluded. The Institutional Review Board classified this project as quality improvement and did not require review and oversight.

Intervention

On July 6, 2015, our Epic (Epic Systems Corporation, Madison, WI) EHR telemetry order was modified to discourage unnecessary telemetry monitoring. The new order required providers ordering telemetry to choose a clinical indication and select a duration for monitoring, after which the order would expire and require physician renewal or discontinuation. These were the only changes that occurred for nonhospitalist providers. The nonhospitalist group included all admitting providers who were not hospitalists. This group included neurology (6.98%); cardiology (8.13%); other medical specialties such as pulmonology, hematology, and oncology (21.30%); cardiothoracic surgery (3.72%); orthopedic surgery (14.84%); general surgery (11.11%); neurosurgery (11.07%); and other surgical specialties, including urology, transplant, vascular surgery, and plastics (16.68%).

Between January 2015 and June 2015, we implemented a multicomponent program among our hospitalist service. The hospitalist service is composed of 4 teams with internal medicine residents and 2 teams with advanced practice providers, all staffed by academic hospitalists. Our program was composed of 5 elements, all of which were made before the hospital-wide changes to electronic telemetry orders and maintained throughout the study period, as follows: (1) a single provider education session reviewing available evidence (eg, AHA guidelines, Choosing Wisely® campaign), (2) removal of the telemetry order from hospitalist admission order set on March 23, 2015, (3) inclusion of telemetry discussion in the hospitalist group’s daily “Rounding Checklist,”14 (4) monthly feedback provided as part of hospitalist group meetings, and (5) a financial incentive, awarded to the division (no individual provider payment) if performance targets were met. See supplementary Appendix (“Implementation Manual”) for further details.

Data Source

We obtained data on patient age, gender, Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Group, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), CMI, admitting unit, attending physician, admission and discharge dates, length of stay (LOS), 30-day readmission, bed charge (telemetry or nontelemetry), ICU stay, and inpatient mortality from the enterprise data warehouse. Telemetry days were determined through room billing charges, which are assigned based on the presence or absence of an active telemetry order at midnight. Code events came from a log kept by the hospital telephone operator, who is responsible for sending out all calls to the code team. Code event data were available starting July 19, 2014.

Measures

Our primary outcome was the percentage of hospital days that had telemetry charges for individual patients. All billed telemetry days on acute care floors were included regardless of admission status (inpatient vs observation), service, indication, or ordering provider. Secondary outcomes were inpatient mortality, escalation of care, code event rates, and appropriate telemetry utilization rates. Escalation of care was defined as transfer to an ICU after initially being admitted to an acute care floor. The code event rate was defined as the ratio of the number of code team activations to the number of patient days. Appropriate telemetry utilization rates were determined via chart review, as detailed below.

In order to evaluate changes in appropriateness of telemetry monitoring, 4 of the authors who are internal medicine physicians (KE, CC, JC, DG) performed chart reviews of 25 randomly selected patients in each group (hospitalist and nonhospitalist) before and after the intervention who received at least 1 day of telemetry monitoring. Each reviewer was provided a key based on AHA guidelines for monitoring indications and associated maximum allowable durations.3 Chart reviews were performed to determine the indication (if any) for monitoring, as well as the number of days that were indicated. The number of indicated days was compared to the number of telemetry days the patient received to determine the overall proportion of days that were indicated (“Telemetry appropriateness per visit”). Three reviewers (KE, AR, CC) also evaluated 100 patients on the hospitalist service after the intervention who did not receive any telemetry monitoring to evaluate whether patients with indications for telemetry monitoring were not receiving it after the intervention. For patients who had a possible indication, the indication was classified as Class I (“Cardiac monitoring is indicated in most, if not all, patients in this group”) or Class II (“Cardiac monitoring may be of benefit in some patients but is not considered essential for all patients”).3

Adjustment Variables

To account for differences in patient characteristics between hospitalist and nonhospitalist groups, we included age, gender, CMI, and CCI in statistical models. CCI was calculated according to the algorithm specified by Quan et al.15 using all patient diagnoses from previous visits and the index visit identified from the facility billing system.

Statistical Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics for study outcomes and visit characteristics for hospitalist and nonhospitalist visits for pre- and postintervention periods. Descriptive statistics were expressed as n (%) for categorical patient characteristics and outcome variables. For continuous patient characteristics, we expressed the variability of individual observations as the mean ± the standard deviation. For continuous outcomes, we expressed the precision of the mean estimates using standard error. Telemetry utilization per visit was weighted by the number of total acute care days per visit. Telemetry appropriateness per visit was weighted by the number of telemetry days per visit. Patients who did not receive any telemetry monitoring were included in the analysis and noted to have 0 telemetry days. All patients had at least 1 acute care day. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests, and continuous variables were compared using t tests. Code event rates were compared using the binomial probability mid-p exact test for person-time data.16

We fitted generalized linear regression models using generalized estimating equations to evaluate the relative change in outcomes of interest in the postintervention period compared with the preintervention period after adjusting for study covariates. The models included study group (hospitalist and nonhospitalist), time period (pre- and postintervention), an interaction term between study group and time period, and study covariates (age, gender, CMI, and CCI). The models were defined using a binomial distributional assumption and logit link function for mortality, escalation of care, and whether patients had at least 1 telemetry day. A gamma distributional assumption and log link function were used for LOS, telemetry acute care days per visit, and total acute care days per visit. A negative binomial distributional assumption and log link function were used for telemetry utilization and telemetry appropriateness. We used the log of the acute care days as an offset for telemetry utilization and the log of the telemetry days per visit as an offset for telemetry appropriateness. An exchangeable working correlation matrix was used to account for physician-level clustering for all outcomes. Intervention effects, representing the difference in odds for categorical variables and in amount for continuous variables, were calculated as exponentiation of the beta parameters for the covariate minus 1.

P values <.05 were considered significant. We used SAS version 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for data analysis.

RESULTS

The percent of patients who had any telemetry charges decreased from 36.2% to 15.9% (P < .001) in the hospitalist group and from 31.8% to 28.0% in the nonhospitalist group (P < .001; Table 1). Rates of code events did not change over time (P = .9).

In the randomly selected sample of patients pre- and postintervention who received telemetry monitoring, there was an increase in telemetry appropriateness on the hospitalist service (46% to 72%, P = .025; Table 1). In the nonhospitalist group, appropriate telemetry utilization did not change significantly. Of the 100 randomly selected patients in the hospitalist group after the intervention who did not receive telemetry, no patient had an AHA Class I indication, and only 4 patients had a Class II indication.3,17

DISCUSSION

In this study, implementing a change in the EHR telemetry order produced reductions in telemetry days. However, when combined with a multicomponent program including education, audit and feedback, financial incentives, and changes to remove telemetry orders from admission orders sets, an even more marked improvement was seen. Neither intervention reduced LOS, increased code event rates, or increased rates of escalation of care.

Prior studies have evaluated interventions to reduce unnecessary telemetry monitoring with varying degrees of success. The most successful EHR intervention to date, from Dressler et al.,18 achieved a 70% reduction in overall telemetry use by integrating the AHA guidelines into their EHR and incorporating nursing discontinuation guidelines to ensure that telemetry discontinuation was both safe and timely. Other studies using stewardship approaches and standardized protocols have been less successful.19,20 One study utilizing a multidisciplinary approach but not including an EHR component showed modest improvements in telemetry.21

Although we are unable to differentiate the exact effect of each component of the intervention, we did note an immediate decrease in telemetry orders after removing the telemetry order from our admission order set, a trend that was magnified after the addition of broader EHR changes (Figure 1). Important additional contributors to our success seem to have been the standardization of rounds to include daily discussion of telemetry and the provision of routine feedback. We cannot discern whether other components of our program (such as the financial incentives) contributed more or less to our program, though the sum of these interventions produced an overall program that required substantial buy in and sustained focus from the hospitalist group. The importance of the hospitalist program is highlighted by the relatively large differences in improvement compared with the nonhospitalist group.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single center, which may limit its generalizability. Second, the intervention was multifaceted, diminishing our ability to discern which aspects beyond the system-wide change in the telemetry order were most responsible for the observed effect among hospitalists. Third, we are unable to fully account for baseline differences in telemetry utilization between hospitalist and nonhospitalist groups. It is likely that different services utilize telemetry monitoring in different ways, and the hospitalist group may have been more aware of the existing guidelines for monitoring prior to the intervention. Furthermore, we had a limited sample size for the chart audits, which reduced the available statistical power for determining changes in the appropriateness of telemetry utilization. Additionally, because internal medicine residents rotate through various services, it is possible that the education they received on their hospitalist rotation as part of our intervention had a spillover effect in the nonhospitalist group. However, any effect should have decreased the difference between the groups. Lastly, although our postintervention time period was 1 year, we do not have data beyond that to monitor for sustainability of the results.

CONCLUSION

In this single-site study, combining EHR orders prompting physicians to choose a clinical indication and duration for monitoring with a broader program—including upstream changes in ordering as well as education, audit, and feedback—produced reductions in telemetry usage. Whether this reduction improves the appropriateness of telemetry utilization or reduces other effects of telemetry (eg, alert fatigue, calls for benign arrhythmias) cannot be discerned from our study. However, our results support the idea that multipronged approaches to telemetry use are most likely to produce improvements.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Frank Thomas for his assistance with process engineering and Mr. Andrew Wood for his routine provision of data. The statistical analysis was supported by the University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 5UL1TR001067-05 (formerly 8UL1TR000105 and UL1RR025764).

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

1. National Health Expenditure Fact Sheet. 2015; https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet.html. Accessed June 27, 2017.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-1516. PubMed

3. Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. PubMed

4. Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, et al. Update to Practice Standards for Electrocardiographic Monitoring in Hospital Settings: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(19):e273-e344. PubMed

5. Mohammad R, Shah S, Donath E, et al. Non-critical care telemetry and in-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes. J Electrocardiol. 2015;48(3):426-429. PubMed

6. Dhillon SK, Rachko M, Hanon S, Schweitzer P, Bergmann SR. Telemetry monitoring guidelines for efficient and safe delivery of cardiac rhythm monitoring to noncritical hospital inpatients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2009;8(3):125-126. PubMed

7. Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Evaluation of guidelines for the use of telemetry in the non-intensive-care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(1):51-55. PubMed

8. Estrada CA, Prasad NK, Rosman HS, Young MJ. Outcomes of patients hospitalized to a telemetry unit. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74(4):357-362. PubMed

9. Atzema C, Schull MJ, Borgundvaag B, Slaughter GR, Lee CK. ALARMED: adverse events in low-risk patients with chest pain receiving continuous electrocardiographic monitoring in the emergency department. A pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(1):62-67. PubMed

10. Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and cardiac arrest outcomes in 8,932 telemetry ward patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(6):647-652. PubMed

11. The Joint Commission 2017 National Patient Safety Goals https://www.jointcommission.org/hap_2017_npsgs/. Accessed on February 15, 2017.

12. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. The Joint Commission announces 2014 National Patient Safety Goal. Jt Comm Perspect. 2013;33(7):1, 3-4. PubMed

13. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

14. Yarbrough PM, Kukhareva PV, Horton D, Edholm K, Kawamoto K. Multifaceted intervention including education, rounding checklist implementation, cost feedback, and financial incentives reduces inpatient laboratory costs. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):348-354. PubMed

15. Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676-682. PubMed

16. Greenland S, Rothman KJ. Introduction to categorical statistics In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, eds. Modern Epidemiology. Vol 3. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008: 238-257.

17. Henriques-Forsythe MN, Ivonye CC, Jamched U, Kamuguisha LK, Olejeme KA, Onwuanyi AE. Is telemetry overused? Is it as helpful as thought? Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(6):368-372. PubMed

18. Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. PubMed

19. Boggan JC, Navar-Boggan AM, Patel V, Schulteis RD, Simel DL. Reductions in telemetry order duration do not reduce telemetry utilization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):795-796. PubMed

20. Cantillon DJ, Loy M, Burkle A, et al. Association Between Off-site Central Monitoring Using Standardized Cardiac Telemetry and Clinical Outcomes Among Non-Critically Ill Patients. JAMA. 2016;316(5):519-524. PubMed

21. Svec D, Ahuja N, Evans KH, et al. Hospitalist intervention for appropriate use of telemetry reduces length of stay and cost. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):627-632. PubMed

1. National Health Expenditure Fact Sheet. 2015; https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet.html. Accessed June 27, 2017.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-1516. PubMed

3. Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. PubMed

4. Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, et al. Update to Practice Standards for Electrocardiographic Monitoring in Hospital Settings: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(19):e273-e344. PubMed

5. Mohammad R, Shah S, Donath E, et al. Non-critical care telemetry and in-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes. J Electrocardiol. 2015;48(3):426-429. PubMed

6. Dhillon SK, Rachko M, Hanon S, Schweitzer P, Bergmann SR. Telemetry monitoring guidelines for efficient and safe delivery of cardiac rhythm monitoring to noncritical hospital inpatients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2009;8(3):125-126. PubMed

7. Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Evaluation of guidelines for the use of telemetry in the non-intensive-care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(1):51-55. PubMed

8. Estrada CA, Prasad NK, Rosman HS, Young MJ. Outcomes of patients hospitalized to a telemetry unit. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74(4):357-362. PubMed

9. Atzema C, Schull MJ, Borgundvaag B, Slaughter GR, Lee CK. ALARMED: adverse events in low-risk patients with chest pain receiving continuous electrocardiographic monitoring in the emergency department. A pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(1):62-67. PubMed

10. Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and cardiac arrest outcomes in 8,932 telemetry ward patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(6):647-652. PubMed

11. The Joint Commission 2017 National Patient Safety Goals https://www.jointcommission.org/hap_2017_npsgs/. Accessed on February 15, 2017.

12. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. The Joint Commission announces 2014 National Patient Safety Goal. Jt Comm Perspect. 2013;33(7):1, 3-4. PubMed

13. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

14. Yarbrough PM, Kukhareva PV, Horton D, Edholm K, Kawamoto K. Multifaceted intervention including education, rounding checklist implementation, cost feedback, and financial incentives reduces inpatient laboratory costs. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):348-354. PubMed

15. Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676-682. PubMed

16. Greenland S, Rothman KJ. Introduction to categorical statistics In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, eds. Modern Epidemiology. Vol 3. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008: 238-257.

17. Henriques-Forsythe MN, Ivonye CC, Jamched U, Kamuguisha LK, Olejeme KA, Onwuanyi AE. Is telemetry overused? Is it as helpful as thought? Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(6):368-372. PubMed

18. Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. PubMed

19. Boggan JC, Navar-Boggan AM, Patel V, Schulteis RD, Simel DL. Reductions in telemetry order duration do not reduce telemetry utilization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):795-796. PubMed

20. Cantillon DJ, Loy M, Burkle A, et al. Association Between Off-site Central Monitoring Using Standardized Cardiac Telemetry and Clinical Outcomes Among Non-Critically Ill Patients. JAMA. 2016;316(5):519-524. PubMed

21. Svec D, Ahuja N, Evans KH, et al. Hospitalist intervention for appropriate use of telemetry reduces length of stay and cost. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):627-632. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospital-acquired VTE with high risk of recurrence

Clinical question: Is the risk of recurrence for a venous thromboembolism (VTE) acquired as an inpatient higher than other reversible risk factors?

Background: In patients with acute VTE, transient provoking factors place patients at lower risks for recurrent VTE, while persistent factors (that is, cancer) increase risk for recurrence. Unprovoked VTE places patients at intermediate to high risk, but few data are present for VTE experienced while in the hospital.

Study design: Single-center, population-based, prospective cohort study.

Setting: Tromso, Norway.

Synopsis: Using repeat health surveys from 1994 to 2012, researchers followed 822 patients with a validated, first-lifetime VTE. Hospital-related VTE was defined as a VTE within 8 weeks of hospitalization related to medical illness, surgery, or in patients with active cancer.

This global definition of hospital-related VTE was not associated with an increased risk of recurrent VTE (hazard ratio, 0.99; 0.69-1.41). However, in separate groups, the cumulative risk of recurrence after 5 years in hospital-related VTE due to medical illness was similar to nonhospital-related VTE (20.1% vs. 18.4%), higher than VTE related to surgery (11%), and lower than VTE related to cancer (27.4%).

Risk-adjusted analyses maintained these differences in recurrence risk dependent on reason for hospitalization (cancer, medical illness, surgery). When compared with non-hospital VTE, however, hospital-related VTE was associated with a threefold higher risk of death.

Study limitations included being from a single center, possibly underpowered due to low number of events.

Bottom line: Hospital-related VTE has a high risk of recurrence, but risk level is variable and dependent on the reason for hospitalization.

Citation: Bjøri E, Arshad N, Johnsen HS, Hansen J-B, Brækkan SK. Hospital-related first venous thromboembolism and risk of recurrence [published online ahead of print, Sept. 2, 2016]. J Thromb Haemost. doi: 10.1111/jth.13492

Dr. Ciarkowski is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Clinical question: Is the risk of recurrence for a venous thromboembolism (VTE) acquired as an inpatient higher than other reversible risk factors?

Background: In patients with acute VTE, transient provoking factors place patients at lower risks for recurrent VTE, while persistent factors (that is, cancer) increase risk for recurrence. Unprovoked VTE places patients at intermediate to high risk, but few data are present for VTE experienced while in the hospital.

Study design: Single-center, population-based, prospective cohort study.

Setting: Tromso, Norway.

Synopsis: Using repeat health surveys from 1994 to 2012, researchers followed 822 patients with a validated, first-lifetime VTE. Hospital-related VTE was defined as a VTE within 8 weeks of hospitalization related to medical illness, surgery, or in patients with active cancer.

This global definition of hospital-related VTE was not associated with an increased risk of recurrent VTE (hazard ratio, 0.99; 0.69-1.41). However, in separate groups, the cumulative risk of recurrence after 5 years in hospital-related VTE due to medical illness was similar to nonhospital-related VTE (20.1% vs. 18.4%), higher than VTE related to surgery (11%), and lower than VTE related to cancer (27.4%).

Risk-adjusted analyses maintained these differences in recurrence risk dependent on reason for hospitalization (cancer, medical illness, surgery). When compared with non-hospital VTE, however, hospital-related VTE was associated with a threefold higher risk of death.

Study limitations included being from a single center, possibly underpowered due to low number of events.

Bottom line: Hospital-related VTE has a high risk of recurrence, but risk level is variable and dependent on the reason for hospitalization.

Citation: Bjøri E, Arshad N, Johnsen HS, Hansen J-B, Brækkan SK. Hospital-related first venous thromboembolism and risk of recurrence [published online ahead of print, Sept. 2, 2016]. J Thromb Haemost. doi: 10.1111/jth.13492

Dr. Ciarkowski is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Clinical question: Is the risk of recurrence for a venous thromboembolism (VTE) acquired as an inpatient higher than other reversible risk factors?