User login

Major General David N.W. Grant: An Early Leader in Air Force Medicine

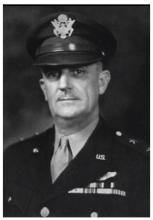

The U.S. Air Force Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base near Fairfield, California, is named in honor of Major General David Norvell Walker Grant, considered by many to be the father of the U.S. Air Force Medical Service. The first legacy organization of the U.S. Air Force was created within the U.S. Army in 1907 (Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps). Through a succession of evolutionary, organizational, and mission changes over 40 years, it became an independent service when the National Security Act of 1947 created the Department of the Air Force. Grant spent most of his career in the predecessor organizations, the U.S. Army Air Corps (1926-1941) and U.S. Army Air Forces (1941-1947).

A native Virginian, Grant graduated from the University of Virginia School of Medicine in 1915 and joined the Army Medical Corps in 1916. His service in World War I included assignments in Panama and within the continental U.S. From 1919 to 1922, he served in Germany in the Army of Occupation. Grant’s aviation medicine career began in 1931 when he attended the School of Aviation Medicine. After he completed the 6-month course, he was stationed at Randolph Field, Texas, for 5 years. In 1937, after more than a decade as a major, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He completed the Air Force Tactical School that same year.

In 1939, Grant became chief of the Medical Division, Office of the Chief of the Air Corps in Washington, DC. On creation of the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1941, he was appointed air surgeon and served in this capacity throughout World War II. He was promoted to colonel in 1941, brigadier general in 1942, and major general in 1943.

Early in preparations for war, Grant recognized that the medical needs of an air force differed significantly from those of large land armies. He and others were successful in their fight to establish a separate medical service for the air forces. During World War II, the U.S. Army Air Forces consisted of 2.4 million personnel and more than 80,000 aircraft. Today the U.S. Air Force has about 320,000 personnel who support and operate about 5,500 aircraft.

Grant was one of the first to understand the need for aeromedical evacuation and was responsible for its organization and operation in World War II. He also was instrumental in the establishment of the Convalescent Rehabilitation Program to help restore the wounded, ill, and injured to full capacity for further service or for their return to the civilian world.

The development and training of flight nurses were inherent in the aeromedical evacuation program. In 1943, the first class of flight nurses graduated from the U.S. Army Air Force School of Air Evacuations at Bowman Field, Kentucky. Second Lieutenant Geraldine Dishroon of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was the honor graduate in her class of 39 students. As she was to receive the first wings presented to a flight nurse, Grant removed his flight surgeon wings and pinned them on Lieutenant Dishroon as a sign of respect for her and the other new flight nurses. In 1944, Lieutenant Dishroon landed with the first air evacuation team on Omaha Beach after the D-Day invasion.

Under Grant’s leadership and guidance, aviation psychologists developed comprehensive mass testing procedures for selecting and classifying potential aircrew members, based on aptitude, personality, and interest. After 3 decades on active duty, Grant retired in 1946 and became medical director for the American Red Cross and national director of the Red Cross Blood Program.

In 1966, 2 years after Grant died, the 4167th Station Hospital at Travis Air Force Base was renamed the David Grant U.S. Air Force Medical Center in his honor.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The U.S. Air Force Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base near Fairfield, California, is named in honor of Major General David Norvell Walker Grant, considered by many to be the father of the U.S. Air Force Medical Service. The first legacy organization of the U.S. Air Force was created within the U.S. Army in 1907 (Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps). Through a succession of evolutionary, organizational, and mission changes over 40 years, it became an independent service when the National Security Act of 1947 created the Department of the Air Force. Grant spent most of his career in the predecessor organizations, the U.S. Army Air Corps (1926-1941) and U.S. Army Air Forces (1941-1947).

A native Virginian, Grant graduated from the University of Virginia School of Medicine in 1915 and joined the Army Medical Corps in 1916. His service in World War I included assignments in Panama and within the continental U.S. From 1919 to 1922, he served in Germany in the Army of Occupation. Grant’s aviation medicine career began in 1931 when he attended the School of Aviation Medicine. After he completed the 6-month course, he was stationed at Randolph Field, Texas, for 5 years. In 1937, after more than a decade as a major, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He completed the Air Force Tactical School that same year.

In 1939, Grant became chief of the Medical Division, Office of the Chief of the Air Corps in Washington, DC. On creation of the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1941, he was appointed air surgeon and served in this capacity throughout World War II. He was promoted to colonel in 1941, brigadier general in 1942, and major general in 1943.

Early in preparations for war, Grant recognized that the medical needs of an air force differed significantly from those of large land armies. He and others were successful in their fight to establish a separate medical service for the air forces. During World War II, the U.S. Army Air Forces consisted of 2.4 million personnel and more than 80,000 aircraft. Today the U.S. Air Force has about 320,000 personnel who support and operate about 5,500 aircraft.

Grant was one of the first to understand the need for aeromedical evacuation and was responsible for its organization and operation in World War II. He also was instrumental in the establishment of the Convalescent Rehabilitation Program to help restore the wounded, ill, and injured to full capacity for further service or for their return to the civilian world.

The development and training of flight nurses were inherent in the aeromedical evacuation program. In 1943, the first class of flight nurses graduated from the U.S. Army Air Force School of Air Evacuations at Bowman Field, Kentucky. Second Lieutenant Geraldine Dishroon of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was the honor graduate in her class of 39 students. As she was to receive the first wings presented to a flight nurse, Grant removed his flight surgeon wings and pinned them on Lieutenant Dishroon as a sign of respect for her and the other new flight nurses. In 1944, Lieutenant Dishroon landed with the first air evacuation team on Omaha Beach after the D-Day invasion.

Under Grant’s leadership and guidance, aviation psychologists developed comprehensive mass testing procedures for selecting and classifying potential aircrew members, based on aptitude, personality, and interest. After 3 decades on active duty, Grant retired in 1946 and became medical director for the American Red Cross and national director of the Red Cross Blood Program.

In 1966, 2 years after Grant died, the 4167th Station Hospital at Travis Air Force Base was renamed the David Grant U.S. Air Force Medical Center in his honor.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The U.S. Air Force Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base near Fairfield, California, is named in honor of Major General David Norvell Walker Grant, considered by many to be the father of the U.S. Air Force Medical Service. The first legacy organization of the U.S. Air Force was created within the U.S. Army in 1907 (Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps). Through a succession of evolutionary, organizational, and mission changes over 40 years, it became an independent service when the National Security Act of 1947 created the Department of the Air Force. Grant spent most of his career in the predecessor organizations, the U.S. Army Air Corps (1926-1941) and U.S. Army Air Forces (1941-1947).

A native Virginian, Grant graduated from the University of Virginia School of Medicine in 1915 and joined the Army Medical Corps in 1916. His service in World War I included assignments in Panama and within the continental U.S. From 1919 to 1922, he served in Germany in the Army of Occupation. Grant’s aviation medicine career began in 1931 when he attended the School of Aviation Medicine. After he completed the 6-month course, he was stationed at Randolph Field, Texas, for 5 years. In 1937, after more than a decade as a major, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He completed the Air Force Tactical School that same year.

In 1939, Grant became chief of the Medical Division, Office of the Chief of the Air Corps in Washington, DC. On creation of the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1941, he was appointed air surgeon and served in this capacity throughout World War II. He was promoted to colonel in 1941, brigadier general in 1942, and major general in 1943.

Early in preparations for war, Grant recognized that the medical needs of an air force differed significantly from those of large land armies. He and others were successful in their fight to establish a separate medical service for the air forces. During World War II, the U.S. Army Air Forces consisted of 2.4 million personnel and more than 80,000 aircraft. Today the U.S. Air Force has about 320,000 personnel who support and operate about 5,500 aircraft.

Grant was one of the first to understand the need for aeromedical evacuation and was responsible for its organization and operation in World War II. He also was instrumental in the establishment of the Convalescent Rehabilitation Program to help restore the wounded, ill, and injured to full capacity for further service or for their return to the civilian world.

The development and training of flight nurses were inherent in the aeromedical evacuation program. In 1943, the first class of flight nurses graduated from the U.S. Army Air Force School of Air Evacuations at Bowman Field, Kentucky. Second Lieutenant Geraldine Dishroon of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was the honor graduate in her class of 39 students. As she was to receive the first wings presented to a flight nurse, Grant removed his flight surgeon wings and pinned them on Lieutenant Dishroon as a sign of respect for her and the other new flight nurses. In 1944, Lieutenant Dishroon landed with the first air evacuation team on Omaha Beach after the D-Day invasion.

Under Grant’s leadership and guidance, aviation psychologists developed comprehensive mass testing procedures for selecting and classifying potential aircrew members, based on aptitude, personality, and interest. After 3 decades on active duty, Grant retired in 1946 and became medical director for the American Red Cross and national director of the Red Cross Blood Program.

In 1966, 2 years after Grant died, the 4167th Station Hospital at Travis Air Force Base was renamed the David Grant U.S. Air Force Medical Center in his honor.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

Bryant Homer Womack: Honoring Sacrifice

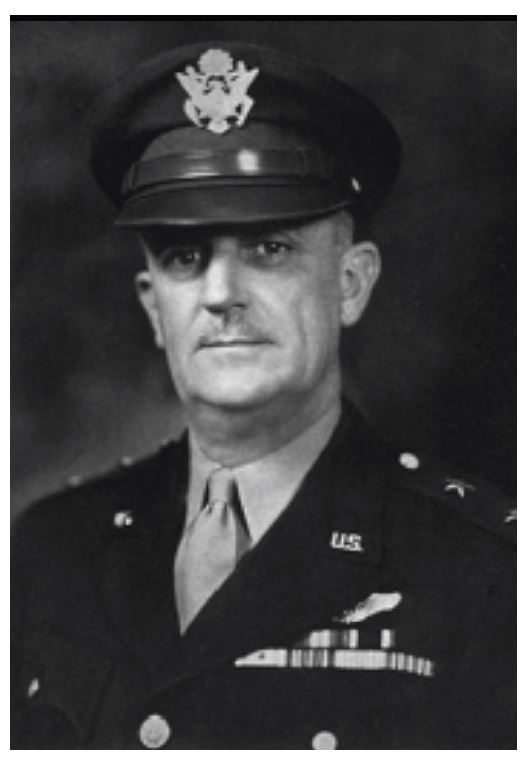

Bryant Homer Womack was born in 1931 and raised in Mill Spring in southwestern North Carolina. He and his 4 siblings grew up doing farmwork. Womack enjoyed the outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. After completing high school, he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950 and later deployed to Korea.

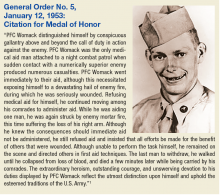

PFC Womack was assigned to the Medical Company, 14th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. During a firefight near Sokso-ri, Korea, on March 12, 1952, his night combat patrol began taking heavy casualties. Womack exposed himself to enemy fire in order to treat his wounded. Although wounded, PFC Womack refused medical treatment and continued to provide aid to others. He was the last soldier to withdraw from the engagement and died of his wounds soon after. Not yet 21 at the time of his death, Womack was buried at Lebanon Methodist Church in his hometown.

PFC Womack received a posthumous Medal of Honor in 1953 (Sidebar) and Womack Army Community Hospital, located on Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, North Carolina, was named for him in 1958. The first medical facility to serve Fort Bragg was constructed in September 1918 as a U.S. States Army Hospital. In June 1932, an 83-bed, 3-story hospital was built and designated Station Hospital One; it was closed in 1941. The building is now Headquarters for XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg. Station Hospital Two and Station Hospital Three were cantonment style hospitals that replaced Station Hospital One. In 1949, the medical facilities were combined and became the U.S. Army Station Hospital.

On August 3, 1958, a new 9-story facility was opened and named Womack Army Community Hospital in honor of combat medic and Medal of Honor recipient PFC Bryant H. Womack. It was renamed the Womack Army Medical Center in 1991. This facility was the principal medical facility for the Fort Bragg community for more than 40 years.

In March, 2000, a new Womack Army Medical Center with more than 1 million square feet of space was dedicated. This new health care complex was part of the U.S. Army Medical Department’s plan to increase patient access to more medical and specialized resources at Fort Bragg.

1. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Medal of Honor Recipients Korean War. https://history.army.mil/moh/koreanwar.html#WOMACK. Updated April 2, 2014. Accessed October 12, 2017.

Bryant Homer Womack was born in 1931 and raised in Mill Spring in southwestern North Carolina. He and his 4 siblings grew up doing farmwork. Womack enjoyed the outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. After completing high school, he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950 and later deployed to Korea.

PFC Womack was assigned to the Medical Company, 14th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. During a firefight near Sokso-ri, Korea, on March 12, 1952, his night combat patrol began taking heavy casualties. Womack exposed himself to enemy fire in order to treat his wounded. Although wounded, PFC Womack refused medical treatment and continued to provide aid to others. He was the last soldier to withdraw from the engagement and died of his wounds soon after. Not yet 21 at the time of his death, Womack was buried at Lebanon Methodist Church in his hometown.

PFC Womack received a posthumous Medal of Honor in 1953 (Sidebar) and Womack Army Community Hospital, located on Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, North Carolina, was named for him in 1958. The first medical facility to serve Fort Bragg was constructed in September 1918 as a U.S. States Army Hospital. In June 1932, an 83-bed, 3-story hospital was built and designated Station Hospital One; it was closed in 1941. The building is now Headquarters for XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg. Station Hospital Two and Station Hospital Three were cantonment style hospitals that replaced Station Hospital One. In 1949, the medical facilities were combined and became the U.S. Army Station Hospital.

On August 3, 1958, a new 9-story facility was opened and named Womack Army Community Hospital in honor of combat medic and Medal of Honor recipient PFC Bryant H. Womack. It was renamed the Womack Army Medical Center in 1991. This facility was the principal medical facility for the Fort Bragg community for more than 40 years.

In March, 2000, a new Womack Army Medical Center with more than 1 million square feet of space was dedicated. This new health care complex was part of the U.S. Army Medical Department’s plan to increase patient access to more medical and specialized resources at Fort Bragg.

Bryant Homer Womack was born in 1931 and raised in Mill Spring in southwestern North Carolina. He and his 4 siblings grew up doing farmwork. Womack enjoyed the outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. After completing high school, he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950 and later deployed to Korea.

PFC Womack was assigned to the Medical Company, 14th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. During a firefight near Sokso-ri, Korea, on March 12, 1952, his night combat patrol began taking heavy casualties. Womack exposed himself to enemy fire in order to treat his wounded. Although wounded, PFC Womack refused medical treatment and continued to provide aid to others. He was the last soldier to withdraw from the engagement and died of his wounds soon after. Not yet 21 at the time of his death, Womack was buried at Lebanon Methodist Church in his hometown.

PFC Womack received a posthumous Medal of Honor in 1953 (Sidebar) and Womack Army Community Hospital, located on Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, North Carolina, was named for him in 1958. The first medical facility to serve Fort Bragg was constructed in September 1918 as a U.S. States Army Hospital. In June 1932, an 83-bed, 3-story hospital was built and designated Station Hospital One; it was closed in 1941. The building is now Headquarters for XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg. Station Hospital Two and Station Hospital Three were cantonment style hospitals that replaced Station Hospital One. In 1949, the medical facilities were combined and became the U.S. Army Station Hospital.

On August 3, 1958, a new 9-story facility was opened and named Womack Army Community Hospital in honor of combat medic and Medal of Honor recipient PFC Bryant H. Womack. It was renamed the Womack Army Medical Center in 1991. This facility was the principal medical facility for the Fort Bragg community for more than 40 years.

In March, 2000, a new Womack Army Medical Center with more than 1 million square feet of space was dedicated. This new health care complex was part of the U.S. Army Medical Department’s plan to increase patient access to more medical and specialized resources at Fort Bragg.

1. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Medal of Honor Recipients Korean War. https://history.army.mil/moh/koreanwar.html#WOMACK. Updated April 2, 2014. Accessed October 12, 2017.

1. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Medal of Honor Recipients Korean War. https://history.army.mil/moh/koreanwar.html#WOMACK. Updated April 2, 2014. Accessed October 12, 2017.

William Beaumont: A Pioneer of Physiology

William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso, Texas, was the first of several military and civilian medical facilities named for U.S. Army doctor William Beaumont (1785-1853). Beaumont was born into a large farming family in Lebanon, Connecticut, and was educated with his siblings in a local schoolhouse. His medical education was by apprenticeship with an established physician in Vermont. At the time, there were fewer than a dozen medical schools in the U.S., and most physicians were educated and trained as apprentices. In July 1812, he passed the Vermont medical examination and became a licensed physician.

In an age when no information traveled faster than the 4 legs of a horse, it is not known how much William Beaumont was aware of the events that led to the American declaration of war against Great Britain in June 1812. It is equally unknown whether a sense of patriotism, youthful adventurism, or simply the need for a job drove Beaumont to join the U.S. Army in September 1812. Regardless of the reasons, he soon was under fire as a Brevet Surgeon’s Mate with the 6th Regiment at the Battle of York in Canada.

The retreating British booby-trapped their powder magazine, which exploded on the Americans and caused more casualties than the battle itself. Beaumont wrote in his journal, “The surgeons wading in blood, cutting off arms, legs, and trepanning heads to rescue their fellow creatures from untimely deaths.” He also wrote that, “it awoke my liveliest sympathy” for his fellow soldiers; he worked for 48 hours without food or sleep. Beaumont saw additional action at Fort George and the Battle of Plattsburgh.Beaumont left the U.S. Army after the war, but following a few years of civilian practice, he returned to active duty and was assigned to the northwestern frontier post on Mackinac Island, Michigan, the site of lively summer fur trading between Canadian trappers and American traders. In June 1822, a young Canadian voyageur, Alexis St. Martin, was accidentally shot in the upper left abdomen at close range with what we know today as a shotgun. Beaumont described the wound as the size of a man’s palm with burned lung and stomach spilling out as well as recently eaten food. He thought attempts to save St. Martin’s life were “entirely useless.”

But Beaumont gave it his best, and St. Martin miraculously survived. The wound healed but left a gastric fistula to the abdominal wall. Over time, Beaumont realized that he was able to witness the previously mysterious functions of the gastrointestinal tract. For more than 10 years, Beaumont studied the physiology of St. Martin’s fistulous stomach, leading to the publication of several articles and a book that earned Beaumont the reputation of at the very least the father of gastric physiology if not of American physiology.

Beaumont and St. Martin eventually parted ways. Beaumont pleaded with St. Martin to return for more studies, but with a wife and many children to support, St. Martin would not. Beaumont again left the U.S. Army to practice medicine in St. Louis, where in 1853, he slipped on ice and struck his head. Several weeks later at the age of 67, he died of his injuries. St. Martin died in 1880 at age 76, living almost 6 decades with a gastric fistula and fathering 17 children.

In 1921, the U.S. Army hospital at Ft. Bliss, Texas, was named for William Beaumont. The building was replaced in 1972 with a 12-story facility known as William Beaumont Army Medical Center. In November 1995, additional space was added for the VA health care center. In 1955, the William Beaumont Hospital opened in Royal Oak, Michigan. This civilian hospital has grown to a health care system with many facilities that include a school of medicine founded in 2011, all named for Beaumont.

For more detailed information on William Beaumont, read Frank TW. Builders of Trust, William Beaumont. The Borden Institute: Fort Detrick, Maryland; 2011.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso, Texas, was the first of several military and civilian medical facilities named for U.S. Army doctor William Beaumont (1785-1853). Beaumont was born into a large farming family in Lebanon, Connecticut, and was educated with his siblings in a local schoolhouse. His medical education was by apprenticeship with an established physician in Vermont. At the time, there were fewer than a dozen medical schools in the U.S., and most physicians were educated and trained as apprentices. In July 1812, he passed the Vermont medical examination and became a licensed physician.

In an age when no information traveled faster than the 4 legs of a horse, it is not known how much William Beaumont was aware of the events that led to the American declaration of war against Great Britain in June 1812. It is equally unknown whether a sense of patriotism, youthful adventurism, or simply the need for a job drove Beaumont to join the U.S. Army in September 1812. Regardless of the reasons, he soon was under fire as a Brevet Surgeon’s Mate with the 6th Regiment at the Battle of York in Canada.

The retreating British booby-trapped their powder magazine, which exploded on the Americans and caused more casualties than the battle itself. Beaumont wrote in his journal, “The surgeons wading in blood, cutting off arms, legs, and trepanning heads to rescue their fellow creatures from untimely deaths.” He also wrote that, “it awoke my liveliest sympathy” for his fellow soldiers; he worked for 48 hours without food or sleep. Beaumont saw additional action at Fort George and the Battle of Plattsburgh.Beaumont left the U.S. Army after the war, but following a few years of civilian practice, he returned to active duty and was assigned to the northwestern frontier post on Mackinac Island, Michigan, the site of lively summer fur trading between Canadian trappers and American traders. In June 1822, a young Canadian voyageur, Alexis St. Martin, was accidentally shot in the upper left abdomen at close range with what we know today as a shotgun. Beaumont described the wound as the size of a man’s palm with burned lung and stomach spilling out as well as recently eaten food. He thought attempts to save St. Martin’s life were “entirely useless.”

But Beaumont gave it his best, and St. Martin miraculously survived. The wound healed but left a gastric fistula to the abdominal wall. Over time, Beaumont realized that he was able to witness the previously mysterious functions of the gastrointestinal tract. For more than 10 years, Beaumont studied the physiology of St. Martin’s fistulous stomach, leading to the publication of several articles and a book that earned Beaumont the reputation of at the very least the father of gastric physiology if not of American physiology.

Beaumont and St. Martin eventually parted ways. Beaumont pleaded with St. Martin to return for more studies, but with a wife and many children to support, St. Martin would not. Beaumont again left the U.S. Army to practice medicine in St. Louis, where in 1853, he slipped on ice and struck his head. Several weeks later at the age of 67, he died of his injuries. St. Martin died in 1880 at age 76, living almost 6 decades with a gastric fistula and fathering 17 children.

In 1921, the U.S. Army hospital at Ft. Bliss, Texas, was named for William Beaumont. The building was replaced in 1972 with a 12-story facility known as William Beaumont Army Medical Center. In November 1995, additional space was added for the VA health care center. In 1955, the William Beaumont Hospital opened in Royal Oak, Michigan. This civilian hospital has grown to a health care system with many facilities that include a school of medicine founded in 2011, all named for Beaumont.

For more detailed information on William Beaumont, read Frank TW. Builders of Trust, William Beaumont. The Borden Institute: Fort Detrick, Maryland; 2011.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso, Texas, was the first of several military and civilian medical facilities named for U.S. Army doctor William Beaumont (1785-1853). Beaumont was born into a large farming family in Lebanon, Connecticut, and was educated with his siblings in a local schoolhouse. His medical education was by apprenticeship with an established physician in Vermont. At the time, there were fewer than a dozen medical schools in the U.S., and most physicians were educated and trained as apprentices. In July 1812, he passed the Vermont medical examination and became a licensed physician.

In an age when no information traveled faster than the 4 legs of a horse, it is not known how much William Beaumont was aware of the events that led to the American declaration of war against Great Britain in June 1812. It is equally unknown whether a sense of patriotism, youthful adventurism, or simply the need for a job drove Beaumont to join the U.S. Army in September 1812. Regardless of the reasons, he soon was under fire as a Brevet Surgeon’s Mate with the 6th Regiment at the Battle of York in Canada.

The retreating British booby-trapped their powder magazine, which exploded on the Americans and caused more casualties than the battle itself. Beaumont wrote in his journal, “The surgeons wading in blood, cutting off arms, legs, and trepanning heads to rescue their fellow creatures from untimely deaths.” He also wrote that, “it awoke my liveliest sympathy” for his fellow soldiers; he worked for 48 hours without food or sleep. Beaumont saw additional action at Fort George and the Battle of Plattsburgh.Beaumont left the U.S. Army after the war, but following a few years of civilian practice, he returned to active duty and was assigned to the northwestern frontier post on Mackinac Island, Michigan, the site of lively summer fur trading between Canadian trappers and American traders. In June 1822, a young Canadian voyageur, Alexis St. Martin, was accidentally shot in the upper left abdomen at close range with what we know today as a shotgun. Beaumont described the wound as the size of a man’s palm with burned lung and stomach spilling out as well as recently eaten food. He thought attempts to save St. Martin’s life were “entirely useless.”

But Beaumont gave it his best, and St. Martin miraculously survived. The wound healed but left a gastric fistula to the abdominal wall. Over time, Beaumont realized that he was able to witness the previously mysterious functions of the gastrointestinal tract. For more than 10 years, Beaumont studied the physiology of St. Martin’s fistulous stomach, leading to the publication of several articles and a book that earned Beaumont the reputation of at the very least the father of gastric physiology if not of American physiology.

Beaumont and St. Martin eventually parted ways. Beaumont pleaded with St. Martin to return for more studies, but with a wife and many children to support, St. Martin would not. Beaumont again left the U.S. Army to practice medicine in St. Louis, where in 1853, he slipped on ice and struck his head. Several weeks later at the age of 67, he died of his injuries. St. Martin died in 1880 at age 76, living almost 6 decades with a gastric fistula and fathering 17 children.

In 1921, the U.S. Army hospital at Ft. Bliss, Texas, was named for William Beaumont. The building was replaced in 1972 with a 12-story facility known as William Beaumont Army Medical Center. In November 1995, additional space was added for the VA health care center. In 1955, the William Beaumont Hospital opened in Royal Oak, Michigan. This civilian hospital has grown to a health care system with many facilities that include a school of medicine founded in 2011, all named for Beaumont.

For more detailed information on William Beaumont, read Frank TW. Builders of Trust, William Beaumont. The Borden Institute: Fort Detrick, Maryland; 2011.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

Walter Reed: A Legacy of Leadership and Service

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, is one of several military and civilian medical facilities named for a U.S. Army doctor.

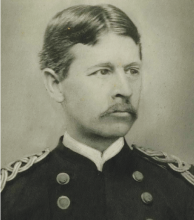

Walter Reed, MD, was born September 13, 1851 near Gloucester on Virginia’s middle peninsula. His father was the pastor of the Bellamy Methodist Church. The Reed family frequently moved as was required by the church and thus lived in many areas of southeastern Virginia and North Carolina. After the Civil War, Reverend Reed moved his family to Charlottesville, Virginia, where Walter, 15, and 2 of his older brothers were enrolled in the University of Virginia.

After a successful year of study, Reed summoned enough courage to confront the formidably bearded elders of the medical faculty with a bold proposal: If he passed all the courses, would they award him a medical degree regardless of the time it took or his age when he finished? A little more than 2 months shy of this 18th birthday, Reed graduated standing third in a class of 10 remaining from the original 50. He was, then and now, the youngest person ever to graduate from the University of Virginia School of Medicine. Reed went to Bellevue Hospital Medical School in New York for clinical hospital training. In another year, he earned his second medical degree, though it was not awarded until after he had reached the ripe old age of 21.

Reed joined the U.S. Army in 1875, possibly looking for a secure position that allowed him to marry his sweetheart Emily Lawrence in 1876. Over the first 18 years of marriage, they moved about 15 times throughout the west with some eastern assignments.

The selection of George Miller Steinberg as Army Surgeon General in 1893 turned out to be a watershed in Reed’s career. He joined the faculty of the new Army medical school. Reed lived closer to Washington (Minnesota) than did the other candidate (California), which probably helped his candidacy. Reed took full advantage of this opportunity and became a trusted troubleshooter for Sternberg.

After the Spanish-American War, Reed led a U.S. Army board that investigated typhoid fever in stateside camps, which killed more soldiers than died on the battlefield during the war. The findings of this board alone would have made Reed famous, but before these findings were formally published, Reed was sent to Cuba to lead another U.S. Army board to investigate infectious diseases, including yellow fever. Over the course of a few months, with the input and assistance of many others, he designed and carried out a series of human experiments that proved the mosquito as the vector of yellow fever. Application of his findings quickly led to the control of yellow fever in Cuba and later in Panama and throughout the tropics.

Reed died in Washington, DC, in 1902 at age 51, following surgery that discovered a ruptured appendix, which in that pre-antibiotic era was nearly always fatal. William Borden, his surgeon and friend, campaigned for several years for a new U.S. Army hospital in Washington to be named for Reed. Borden was successful with the opening of Walter Reed Army General Hospital in 1909. Renamed Walter Reed Army Medical Center in 1951 on the 100th anniversary of Reed’s birth, the hospital was closed in 2011 and its name transferred to the new Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Other facilities named for Reed include the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Maryland and the civilian Riverside Walter Reed Hospital in Gloucester Courthouse, Virginia.

A particularly interesting resource to learn more about Reed is the Philip Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection. Most of the collection is available online (http://yellowfever.lib.virginia.edu/reed).

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, is one of several military and civilian medical facilities named for a U.S. Army doctor.

Walter Reed, MD, was born September 13, 1851 near Gloucester on Virginia’s middle peninsula. His father was the pastor of the Bellamy Methodist Church. The Reed family frequently moved as was required by the church and thus lived in many areas of southeastern Virginia and North Carolina. After the Civil War, Reverend Reed moved his family to Charlottesville, Virginia, where Walter, 15, and 2 of his older brothers were enrolled in the University of Virginia.

After a successful year of study, Reed summoned enough courage to confront the formidably bearded elders of the medical faculty with a bold proposal: If he passed all the courses, would they award him a medical degree regardless of the time it took or his age when he finished? A little more than 2 months shy of this 18th birthday, Reed graduated standing third in a class of 10 remaining from the original 50. He was, then and now, the youngest person ever to graduate from the University of Virginia School of Medicine. Reed went to Bellevue Hospital Medical School in New York for clinical hospital training. In another year, he earned his second medical degree, though it was not awarded until after he had reached the ripe old age of 21.

Reed joined the U.S. Army in 1875, possibly looking for a secure position that allowed him to marry his sweetheart Emily Lawrence in 1876. Over the first 18 years of marriage, they moved about 15 times throughout the west with some eastern assignments.

The selection of George Miller Steinberg as Army Surgeon General in 1893 turned out to be a watershed in Reed’s career. He joined the faculty of the new Army medical school. Reed lived closer to Washington (Minnesota) than did the other candidate (California), which probably helped his candidacy. Reed took full advantage of this opportunity and became a trusted troubleshooter for Sternberg.

After the Spanish-American War, Reed led a U.S. Army board that investigated typhoid fever in stateside camps, which killed more soldiers than died on the battlefield during the war. The findings of this board alone would have made Reed famous, but before these findings were formally published, Reed was sent to Cuba to lead another U.S. Army board to investigate infectious diseases, including yellow fever. Over the course of a few months, with the input and assistance of many others, he designed and carried out a series of human experiments that proved the mosquito as the vector of yellow fever. Application of his findings quickly led to the control of yellow fever in Cuba and later in Panama and throughout the tropics.

Reed died in Washington, DC, in 1902 at age 51, following surgery that discovered a ruptured appendix, which in that pre-antibiotic era was nearly always fatal. William Borden, his surgeon and friend, campaigned for several years for a new U.S. Army hospital in Washington to be named for Reed. Borden was successful with the opening of Walter Reed Army General Hospital in 1909. Renamed Walter Reed Army Medical Center in 1951 on the 100th anniversary of Reed’s birth, the hospital was closed in 2011 and its name transferred to the new Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Other facilities named for Reed include the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Maryland and the civilian Riverside Walter Reed Hospital in Gloucester Courthouse, Virginia.

A particularly interesting resource to learn more about Reed is the Philip Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection. Most of the collection is available online (http://yellowfever.lib.virginia.edu/reed).

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, is one of several military and civilian medical facilities named for a U.S. Army doctor.

Walter Reed, MD, was born September 13, 1851 near Gloucester on Virginia’s middle peninsula. His father was the pastor of the Bellamy Methodist Church. The Reed family frequently moved as was required by the church and thus lived in many areas of southeastern Virginia and North Carolina. After the Civil War, Reverend Reed moved his family to Charlottesville, Virginia, where Walter, 15, and 2 of his older brothers were enrolled in the University of Virginia.

After a successful year of study, Reed summoned enough courage to confront the formidably bearded elders of the medical faculty with a bold proposal: If he passed all the courses, would they award him a medical degree regardless of the time it took or his age when he finished? A little more than 2 months shy of this 18th birthday, Reed graduated standing third in a class of 10 remaining from the original 50. He was, then and now, the youngest person ever to graduate from the University of Virginia School of Medicine. Reed went to Bellevue Hospital Medical School in New York for clinical hospital training. In another year, he earned his second medical degree, though it was not awarded until after he had reached the ripe old age of 21.

Reed joined the U.S. Army in 1875, possibly looking for a secure position that allowed him to marry his sweetheart Emily Lawrence in 1876. Over the first 18 years of marriage, they moved about 15 times throughout the west with some eastern assignments.

The selection of George Miller Steinberg as Army Surgeon General in 1893 turned out to be a watershed in Reed’s career. He joined the faculty of the new Army medical school. Reed lived closer to Washington (Minnesota) than did the other candidate (California), which probably helped his candidacy. Reed took full advantage of this opportunity and became a trusted troubleshooter for Sternberg.

After the Spanish-American War, Reed led a U.S. Army board that investigated typhoid fever in stateside camps, which killed more soldiers than died on the battlefield during the war. The findings of this board alone would have made Reed famous, but before these findings were formally published, Reed was sent to Cuba to lead another U.S. Army board to investigate infectious diseases, including yellow fever. Over the course of a few months, with the input and assistance of many others, he designed and carried out a series of human experiments that proved the mosquito as the vector of yellow fever. Application of his findings quickly led to the control of yellow fever in Cuba and later in Panama and throughout the tropics.

Reed died in Washington, DC, in 1902 at age 51, following surgery that discovered a ruptured appendix, which in that pre-antibiotic era was nearly always fatal. William Borden, his surgeon and friend, campaigned for several years for a new U.S. Army hospital in Washington to be named for Reed. Borden was successful with the opening of Walter Reed Army General Hospital in 1909. Renamed Walter Reed Army Medical Center in 1951 on the 100th anniversary of Reed’s birth, the hospital was closed in 2011 and its name transferred to the new Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Other facilities named for Reed include the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Maryland and the civilian Riverside Walter Reed Hospital in Gloucester Courthouse, Virginia.

A particularly interesting resource to learn more about Reed is the Philip Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection. Most of the collection is available online (http://yellowfever.lib.virginia.edu/reed).