User login

Louis Johnson: First Cold War SecDef

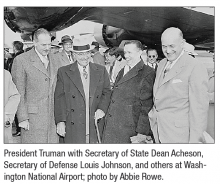

The VA Medical Center in Clarksburg, West Virginia, is named in honor of Louis Arthur Johnson, the Secretary of Defense under President Truman. Johnson cultivated a diversity of viewpoints and experiences before becoming Secretary of Defense. He was born in Roanoke, Virginia, in 1891, and he earned a law degree from the University of Virginia. Two years later, he began his foray into politics with election to the West Virginia House of Delegates, where he acted as Majority Floor Leader and Chair of the Judiciary Committee.1

Johnson served as an Infantry Captain in France during World War I, fighting in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and earning the Legion of Honor of France. During his service, he gained insight into the military logistics by presenting a lengthy report on Army management and materiel requisition to the War Department—a foreshadowing of his eventual commitment to military budget restructuring as Secretary of Defense. After returning from the war, he practiced law and focused his efforts on aiding veterans, eventually securing the role of National Commander of the American Legion.1

Johnson was Assistant Secretary of War from 1937 to 1940 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Johnson frequently disagreed with the policies of Harry Hines Woodring, the acting Secretary of War who was a committed isolationist. While Johnson was adamant about providing military assistance to Great Britain during World War II, Woodring’s isolationism prevailed. However, in 1940, the fall of France forced the US to re-examine its defenses. Woodring resigned, and an eager Johnson was ready to take his place to re-instill confidence in the nation’s defenses against foreign threats.2

His enthusiasm was short-lived. President Roosevelt instead chose to appoint Henry Stimson as Secretary of Defense. Johnson felt betrayed.2 Johnson served as the personal representative of President Roosevelt in India, where he forged a lasting friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India.

The 1948 presidential campaign was Johnson’s turn of fate. He aggressively raised funds for President Truman’s campaign and explicitly communicated his interest in serving as Secretary of Defense to the President, emphasizing that his goals for the nation’s defense were in line with those of Truman. Both favored aggressive elimination of unnecessary spending as well as unification of the military to minimize redundancies. In 1949, President Truman asked Johnson to replace James V. Forrestal, the acting Secretary of Defense.1

Johnson’s legacy as Defense Secretary was controversial from the beginning. His overarching goal was to cut any military spending that he deemed superfluous, proclaiming that taxpayers would receive “a dollar’s worth of defense for every dollar spent.”1 He and President Truman were confident that the atomic bomb would curtail most foreign aggression.

He faced enormous push back from military leaders in charge of ambitious expansion projects. The animosity amplified abruptly when Johnson canceled construction of the aircraft carrier USS United States, a multiyear construction effort by the US Navy already in progress. Johnson had not consulted with Congress or the Department of the Navy before announcing this cancellation. John L. Sullivan, the Secretary of the Navy, resigned in exasperation amidst the confusion and voiced his concerns about the future of the nation’s defense.1

Other branches of the military also experienced reductions, fueling an atmosphere of competition for limited funds. The “Revolt of the Admirals” that followed the scrapping of the United States was a salient example of this struggle, as leaders of the Navy and Air Force bitterly quarreled to earn Johnson’s approval for their respective expenses. Tensions rose to a peak in June 1949, when the House Committee on Armed Services commissioned a formal investigation of malfeasance against Secretary Johnson and the Air Force Secretary, likely at the behest of the Navy. These hearings challenged the entirety of Johnson’s platform, criticizing him for the United States cancellation, the feasibility of deterring foreign aggression with nuclear deterrence, and his overarching plan for military unification. After a lengthy series of charges, Johnson survived as the Committee found no convincing evidence of malfeasance. They also chose to support his plans for military unification, albeit with an admonition against aggressive, hasty overunification. Although Johnson had originally intended to eliminate waste and promote cohesiveness by establishing a more unified defense, his budget cuts had the unfortunate effect of creating deep rifts between the branches of the military.1

Johnson supported the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the unified efforts of Soviet containment. However, in August 1949 the Soviets shocked the world with a successful atomic bomb test, and the Communists emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War. In response, President Truman—with Johnson’s support—definitively called for development of the hydrogen bomb. In collaboration with the State Department, Johnson coauthored NSC 68, a top-secret report detailing nuclear expansion, Soviet containment, and aid to allies that laid the groundwork for militarization from the Cold War to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.1

Despite the mounting threats, Johnson remained steadfast in his commitment to defense budgeting. The consequences of his economizing were felt at the beginning of the Korean War, as US and South Korean forces lacked adequate supplies to hold back the advance from the North Koreans. The rearguard operations that ensued proved to be extremely costly, and Johnson was forced to acknowledge that, “we have reached the point where the military considerations clearly outweigh the fiscal considerations.”4,5 In response to widespread public outcry over the progress in Korea, Truman asked Johnson to resign as Secretary of Defense, paving the way for George Marshall, General of the Army.

With his resignation, Johnson saw the end of his career in politics. He died in 1966 of a stroke but not before the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center, was dedicated in his honor on December 7, 1950.6

Despite the controversies surrounding his tenure, Johnson prioritized the well-being of the US more than anything else. At the end of his term, he solemnly paraphrased Macbeth, “When the hurly burly’s done and the battle is won, I trust the historian will find my record of performance creditable, my services honest and faithful commensurate with the trust that was placed in me and in the best interests of peace and our national defense.”

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

1. US Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Historical Office. Louis A. Johnson – Harry S. Truman Administration. http://history.defense.gov/Multimedia/Biographies/Article-View/Article/571265/. Accessed June 20, 2018.

2. Master of the Pentagon, Time. 1949;53(23).

3. LaFeber W. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945-1992. 7th edition New York: McGraw-Hill; 1993.

4. Zabecki DT. Stand or die—1950 defense of Korea’s Pusan perimeter. http://www.historynet.com/magazines/military_history. Published May 1, 2009. Accessed June 20, 2018.

5. McFarland KD, Roll DL. Louis Johnson and the Arming of America: The Roosevelt And Truman Years. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 2005.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Louis A. Johnson Medical Center. https://www.clarksburg.va.gov/about/history.asp. Updated June 9, 2015. Accessed June 20, 2018.

The VA Medical Center in Clarksburg, West Virginia, is named in honor of Louis Arthur Johnson, the Secretary of Defense under President Truman. Johnson cultivated a diversity of viewpoints and experiences before becoming Secretary of Defense. He was born in Roanoke, Virginia, in 1891, and he earned a law degree from the University of Virginia. Two years later, he began his foray into politics with election to the West Virginia House of Delegates, where he acted as Majority Floor Leader and Chair of the Judiciary Committee.1

Johnson served as an Infantry Captain in France during World War I, fighting in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and earning the Legion of Honor of France. During his service, he gained insight into the military logistics by presenting a lengthy report on Army management and materiel requisition to the War Department—a foreshadowing of his eventual commitment to military budget restructuring as Secretary of Defense. After returning from the war, he practiced law and focused his efforts on aiding veterans, eventually securing the role of National Commander of the American Legion.1

Johnson was Assistant Secretary of War from 1937 to 1940 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Johnson frequently disagreed with the policies of Harry Hines Woodring, the acting Secretary of War who was a committed isolationist. While Johnson was adamant about providing military assistance to Great Britain during World War II, Woodring’s isolationism prevailed. However, in 1940, the fall of France forced the US to re-examine its defenses. Woodring resigned, and an eager Johnson was ready to take his place to re-instill confidence in the nation’s defenses against foreign threats.2

His enthusiasm was short-lived. President Roosevelt instead chose to appoint Henry Stimson as Secretary of Defense. Johnson felt betrayed.2 Johnson served as the personal representative of President Roosevelt in India, where he forged a lasting friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India.

The 1948 presidential campaign was Johnson’s turn of fate. He aggressively raised funds for President Truman’s campaign and explicitly communicated his interest in serving as Secretary of Defense to the President, emphasizing that his goals for the nation’s defense were in line with those of Truman. Both favored aggressive elimination of unnecessary spending as well as unification of the military to minimize redundancies. In 1949, President Truman asked Johnson to replace James V. Forrestal, the acting Secretary of Defense.1

Johnson’s legacy as Defense Secretary was controversial from the beginning. His overarching goal was to cut any military spending that he deemed superfluous, proclaiming that taxpayers would receive “a dollar’s worth of defense for every dollar spent.”1 He and President Truman were confident that the atomic bomb would curtail most foreign aggression.

He faced enormous push back from military leaders in charge of ambitious expansion projects. The animosity amplified abruptly when Johnson canceled construction of the aircraft carrier USS United States, a multiyear construction effort by the US Navy already in progress. Johnson had not consulted with Congress or the Department of the Navy before announcing this cancellation. John L. Sullivan, the Secretary of the Navy, resigned in exasperation amidst the confusion and voiced his concerns about the future of the nation’s defense.1

Other branches of the military also experienced reductions, fueling an atmosphere of competition for limited funds. The “Revolt of the Admirals” that followed the scrapping of the United States was a salient example of this struggle, as leaders of the Navy and Air Force bitterly quarreled to earn Johnson’s approval for their respective expenses. Tensions rose to a peak in June 1949, when the House Committee on Armed Services commissioned a formal investigation of malfeasance against Secretary Johnson and the Air Force Secretary, likely at the behest of the Navy. These hearings challenged the entirety of Johnson’s platform, criticizing him for the United States cancellation, the feasibility of deterring foreign aggression with nuclear deterrence, and his overarching plan for military unification. After a lengthy series of charges, Johnson survived as the Committee found no convincing evidence of malfeasance. They also chose to support his plans for military unification, albeit with an admonition against aggressive, hasty overunification. Although Johnson had originally intended to eliminate waste and promote cohesiveness by establishing a more unified defense, his budget cuts had the unfortunate effect of creating deep rifts between the branches of the military.1

Johnson supported the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the unified efforts of Soviet containment. However, in August 1949 the Soviets shocked the world with a successful atomic bomb test, and the Communists emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War. In response, President Truman—with Johnson’s support—definitively called for development of the hydrogen bomb. In collaboration with the State Department, Johnson coauthored NSC 68, a top-secret report detailing nuclear expansion, Soviet containment, and aid to allies that laid the groundwork for militarization from the Cold War to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.1

Despite the mounting threats, Johnson remained steadfast in his commitment to defense budgeting. The consequences of his economizing were felt at the beginning of the Korean War, as US and South Korean forces lacked adequate supplies to hold back the advance from the North Koreans. The rearguard operations that ensued proved to be extremely costly, and Johnson was forced to acknowledge that, “we have reached the point where the military considerations clearly outweigh the fiscal considerations.”4,5 In response to widespread public outcry over the progress in Korea, Truman asked Johnson to resign as Secretary of Defense, paving the way for George Marshall, General of the Army.

With his resignation, Johnson saw the end of his career in politics. He died in 1966 of a stroke but not before the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center, was dedicated in his honor on December 7, 1950.6

Despite the controversies surrounding his tenure, Johnson prioritized the well-being of the US more than anything else. At the end of his term, he solemnly paraphrased Macbeth, “When the hurly burly’s done and the battle is won, I trust the historian will find my record of performance creditable, my services honest and faithful commensurate with the trust that was placed in me and in the best interests of peace and our national defense.”

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The VA Medical Center in Clarksburg, West Virginia, is named in honor of Louis Arthur Johnson, the Secretary of Defense under President Truman. Johnson cultivated a diversity of viewpoints and experiences before becoming Secretary of Defense. He was born in Roanoke, Virginia, in 1891, and he earned a law degree from the University of Virginia. Two years later, he began his foray into politics with election to the West Virginia House of Delegates, where he acted as Majority Floor Leader and Chair of the Judiciary Committee.1

Johnson served as an Infantry Captain in France during World War I, fighting in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and earning the Legion of Honor of France. During his service, he gained insight into the military logistics by presenting a lengthy report on Army management and materiel requisition to the War Department—a foreshadowing of his eventual commitment to military budget restructuring as Secretary of Defense. After returning from the war, he practiced law and focused his efforts on aiding veterans, eventually securing the role of National Commander of the American Legion.1

Johnson was Assistant Secretary of War from 1937 to 1940 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Johnson frequently disagreed with the policies of Harry Hines Woodring, the acting Secretary of War who was a committed isolationist. While Johnson was adamant about providing military assistance to Great Britain during World War II, Woodring’s isolationism prevailed. However, in 1940, the fall of France forced the US to re-examine its defenses. Woodring resigned, and an eager Johnson was ready to take his place to re-instill confidence in the nation’s defenses against foreign threats.2

His enthusiasm was short-lived. President Roosevelt instead chose to appoint Henry Stimson as Secretary of Defense. Johnson felt betrayed.2 Johnson served as the personal representative of President Roosevelt in India, where he forged a lasting friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India.

The 1948 presidential campaign was Johnson’s turn of fate. He aggressively raised funds for President Truman’s campaign and explicitly communicated his interest in serving as Secretary of Defense to the President, emphasizing that his goals for the nation’s defense were in line with those of Truman. Both favored aggressive elimination of unnecessary spending as well as unification of the military to minimize redundancies. In 1949, President Truman asked Johnson to replace James V. Forrestal, the acting Secretary of Defense.1

Johnson’s legacy as Defense Secretary was controversial from the beginning. His overarching goal was to cut any military spending that he deemed superfluous, proclaiming that taxpayers would receive “a dollar’s worth of defense for every dollar spent.”1 He and President Truman were confident that the atomic bomb would curtail most foreign aggression.

He faced enormous push back from military leaders in charge of ambitious expansion projects. The animosity amplified abruptly when Johnson canceled construction of the aircraft carrier USS United States, a multiyear construction effort by the US Navy already in progress. Johnson had not consulted with Congress or the Department of the Navy before announcing this cancellation. John L. Sullivan, the Secretary of the Navy, resigned in exasperation amidst the confusion and voiced his concerns about the future of the nation’s defense.1

Other branches of the military also experienced reductions, fueling an atmosphere of competition for limited funds. The “Revolt of the Admirals” that followed the scrapping of the United States was a salient example of this struggle, as leaders of the Navy and Air Force bitterly quarreled to earn Johnson’s approval for their respective expenses. Tensions rose to a peak in June 1949, when the House Committee on Armed Services commissioned a formal investigation of malfeasance against Secretary Johnson and the Air Force Secretary, likely at the behest of the Navy. These hearings challenged the entirety of Johnson’s platform, criticizing him for the United States cancellation, the feasibility of deterring foreign aggression with nuclear deterrence, and his overarching plan for military unification. After a lengthy series of charges, Johnson survived as the Committee found no convincing evidence of malfeasance. They also chose to support his plans for military unification, albeit with an admonition against aggressive, hasty overunification. Although Johnson had originally intended to eliminate waste and promote cohesiveness by establishing a more unified defense, his budget cuts had the unfortunate effect of creating deep rifts between the branches of the military.1

Johnson supported the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the unified efforts of Soviet containment. However, in August 1949 the Soviets shocked the world with a successful atomic bomb test, and the Communists emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War. In response, President Truman—with Johnson’s support—definitively called for development of the hydrogen bomb. In collaboration with the State Department, Johnson coauthored NSC 68, a top-secret report detailing nuclear expansion, Soviet containment, and aid to allies that laid the groundwork for militarization from the Cold War to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.1

Despite the mounting threats, Johnson remained steadfast in his commitment to defense budgeting. The consequences of his economizing were felt at the beginning of the Korean War, as US and South Korean forces lacked adequate supplies to hold back the advance from the North Koreans. The rearguard operations that ensued proved to be extremely costly, and Johnson was forced to acknowledge that, “we have reached the point where the military considerations clearly outweigh the fiscal considerations.”4,5 In response to widespread public outcry over the progress in Korea, Truman asked Johnson to resign as Secretary of Defense, paving the way for George Marshall, General of the Army.

With his resignation, Johnson saw the end of his career in politics. He died in 1966 of a stroke but not before the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center, was dedicated in his honor on December 7, 1950.6

Despite the controversies surrounding his tenure, Johnson prioritized the well-being of the US more than anything else. At the end of his term, he solemnly paraphrased Macbeth, “When the hurly burly’s done and the battle is won, I trust the historian will find my record of performance creditable, my services honest and faithful commensurate with the trust that was placed in me and in the best interests of peace and our national defense.”

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

1. US Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Historical Office. Louis A. Johnson – Harry S. Truman Administration. http://history.defense.gov/Multimedia/Biographies/Article-View/Article/571265/. Accessed June 20, 2018.

2. Master of the Pentagon, Time. 1949;53(23).

3. LaFeber W. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945-1992. 7th edition New York: McGraw-Hill; 1993.

4. Zabecki DT. Stand or die—1950 defense of Korea’s Pusan perimeter. http://www.historynet.com/magazines/military_history. Published May 1, 2009. Accessed June 20, 2018.

5. McFarland KD, Roll DL. Louis Johnson and the Arming of America: The Roosevelt And Truman Years. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 2005.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Louis A. Johnson Medical Center. https://www.clarksburg.va.gov/about/history.asp. Updated June 9, 2015. Accessed June 20, 2018.

1. US Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Historical Office. Louis A. Johnson – Harry S. Truman Administration. http://history.defense.gov/Multimedia/Biographies/Article-View/Article/571265/. Accessed June 20, 2018.

2. Master of the Pentagon, Time. 1949;53(23).

3. LaFeber W. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945-1992. 7th edition New York: McGraw-Hill; 1993.

4. Zabecki DT. Stand or die—1950 defense of Korea’s Pusan perimeter. http://www.historynet.com/magazines/military_history. Published May 1, 2009. Accessed June 20, 2018.

5. McFarland KD, Roll DL. Louis Johnson and the Arming of America: The Roosevelt And Truman Years. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 2005.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Louis A. Johnson Medical Center. https://www.clarksburg.va.gov/about/history.asp. Updated June 9, 2015. Accessed June 20, 2018.

Brigadier General Carl Rogers Darnall: Saving Lives on a Massive Scale

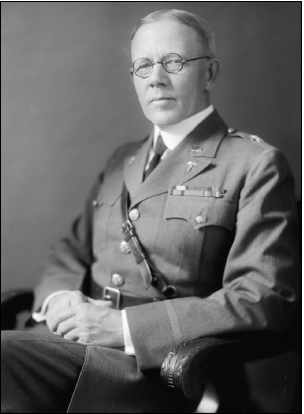

The Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center at Fort Hood, Texas, is named in honor of Brigadier General Carl Rogers Darnall, a Texas native and career Army physician whose active-duty service spanned 35 years. Darnall, the oldest of 7 siblings, could not have imagined the enormity of the contributions that he would make and the lives that would be saved as he pursued a career in medicine.

Born on the family farm north of Dallas on Christmas Day in 1867, Darnall attended college in nearby Bonham and graduated from Transylvania University in Kentucky. He attended Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, graduating in 1890. Darnall spent several years in private practice before he joined the Army Medical Corps in 1896. He completed the Army Medical School in 1897. Opened in 1893, the Army Medical School was a 4-to-6-month course for civilian physicians entering active duty. The courses introduced physicians to the duties of medical officers as well as military surgery, medicine, and hygiene. It is considered by many to be the first school of public health in the U.S.

Darnall’s first assignments in Texas were followed by deployment to Cuba during the Spanish American War and then the Philippines, where he served as an operating surgeon and pathologist aboard the hospital ship, USS Relief. Darnall later accompanied an international expeditionary force to China in response to the Boxer Rebellion. In 1902, Darnall received an assignment to the Army Medical School in Washington, DC, that would change his life and the lives of millions around the world. Detailed as instructor for sanitary chemistry and operative surgery, he also served as secretary of the faculty. Just as Major Walter Reed and others before him, Darnall used his position at the Army Medical School to pursue important clinical research.

The complete story of the purification of drinking water is beyond the scope of this short biography. In brief, as early as 1894 the addition of chlorine to water was shown to render it “germ free.” In the 1890s, there were at least 2 attempts at water purification on a large scale with chlorine in European cities. One of the first uses of chlorine in the U.S. occurred in 1908 in Jersey City, New Jersey. At the Army Medical School, Darnall discovered the value of using compressed liquefied chlorine gas to purify water. He invented a mechanical liquid chlorine purifier in 1910 that became known as a chlorinator. In November 1911, Major Darnall authored a 15-page article concerning water purification.1 Darnall also devised and patented a water filter, which the U.S. Army used for many years.

The principles of his chlorinator and use of anhydrous liquid chlorine were later applied to municipal water supplies throughout the world. The positive benefit of clean drinking water to improving public health is beyond measure. It has been said that more lives have been saved and more sickness prevented by Darnall’s contribution to sanitary water than by any other single achievement in medicine.

During World War I, Darnall was promoted to colonel and assigned to the Finance and Supply Division in the Office of the Surgeon General. After the war, he served as department surgeon in Hawaii. In 1925, he returned to the Office of the Surgeon General as executive officer. In November 1929, he was promoted to brigadier general and became the commanding general of the Army Medical Center and Walter Reed General Hospital, a position he held for 2 years until his retirement in 1931.Darnall died on January 18, 1941, at Walter Reed General Hospital just 6 days after his wife of 48 years had died at their home in Washington, DC. He is buried in Section 3 at Arlington National Cemetery. His 3 sons, Joseph Rogers, William Major, and Carl Robert, all served in some capacity in the Army.

Darnall Army Community Hospital opened in 1965, replacing the World War II-era hospital at Fort Hood. In 1984 a 5-year reconstruction project with additional floor space was completed. On May 1, 2006, the hospital was officially renamed the Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

1. Darnall CR. The purification of water by anhydrous chlorine. J Am Public Health Assoc. 1911;1(11):783-797.

The Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center at Fort Hood, Texas, is named in honor of Brigadier General Carl Rogers Darnall, a Texas native and career Army physician whose active-duty service spanned 35 years. Darnall, the oldest of 7 siblings, could not have imagined the enormity of the contributions that he would make and the lives that would be saved as he pursued a career in medicine.

Born on the family farm north of Dallas on Christmas Day in 1867, Darnall attended college in nearby Bonham and graduated from Transylvania University in Kentucky. He attended Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, graduating in 1890. Darnall spent several years in private practice before he joined the Army Medical Corps in 1896. He completed the Army Medical School in 1897. Opened in 1893, the Army Medical School was a 4-to-6-month course for civilian physicians entering active duty. The courses introduced physicians to the duties of medical officers as well as military surgery, medicine, and hygiene. It is considered by many to be the first school of public health in the U.S.

Darnall’s first assignments in Texas were followed by deployment to Cuba during the Spanish American War and then the Philippines, where he served as an operating surgeon and pathologist aboard the hospital ship, USS Relief. Darnall later accompanied an international expeditionary force to China in response to the Boxer Rebellion. In 1902, Darnall received an assignment to the Army Medical School in Washington, DC, that would change his life and the lives of millions around the world. Detailed as instructor for sanitary chemistry and operative surgery, he also served as secretary of the faculty. Just as Major Walter Reed and others before him, Darnall used his position at the Army Medical School to pursue important clinical research.

The complete story of the purification of drinking water is beyond the scope of this short biography. In brief, as early as 1894 the addition of chlorine to water was shown to render it “germ free.” In the 1890s, there were at least 2 attempts at water purification on a large scale with chlorine in European cities. One of the first uses of chlorine in the U.S. occurred in 1908 in Jersey City, New Jersey. At the Army Medical School, Darnall discovered the value of using compressed liquefied chlorine gas to purify water. He invented a mechanical liquid chlorine purifier in 1910 that became known as a chlorinator. In November 1911, Major Darnall authored a 15-page article concerning water purification.1 Darnall also devised and patented a water filter, which the U.S. Army used for many years.

The principles of his chlorinator and use of anhydrous liquid chlorine were later applied to municipal water supplies throughout the world. The positive benefit of clean drinking water to improving public health is beyond measure. It has been said that more lives have been saved and more sickness prevented by Darnall’s contribution to sanitary water than by any other single achievement in medicine.

During World War I, Darnall was promoted to colonel and assigned to the Finance and Supply Division in the Office of the Surgeon General. After the war, he served as department surgeon in Hawaii. In 1925, he returned to the Office of the Surgeon General as executive officer. In November 1929, he was promoted to brigadier general and became the commanding general of the Army Medical Center and Walter Reed General Hospital, a position he held for 2 years until his retirement in 1931.Darnall died on January 18, 1941, at Walter Reed General Hospital just 6 days after his wife of 48 years had died at their home in Washington, DC. He is buried in Section 3 at Arlington National Cemetery. His 3 sons, Joseph Rogers, William Major, and Carl Robert, all served in some capacity in the Army.

Darnall Army Community Hospital opened in 1965, replacing the World War II-era hospital at Fort Hood. In 1984 a 5-year reconstruction project with additional floor space was completed. On May 1, 2006, the hospital was officially renamed the Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center at Fort Hood, Texas, is named in honor of Brigadier General Carl Rogers Darnall, a Texas native and career Army physician whose active-duty service spanned 35 years. Darnall, the oldest of 7 siblings, could not have imagined the enormity of the contributions that he would make and the lives that would be saved as he pursued a career in medicine.

Born on the family farm north of Dallas on Christmas Day in 1867, Darnall attended college in nearby Bonham and graduated from Transylvania University in Kentucky. He attended Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, graduating in 1890. Darnall spent several years in private practice before he joined the Army Medical Corps in 1896. He completed the Army Medical School in 1897. Opened in 1893, the Army Medical School was a 4-to-6-month course for civilian physicians entering active duty. The courses introduced physicians to the duties of medical officers as well as military surgery, medicine, and hygiene. It is considered by many to be the first school of public health in the U.S.

Darnall’s first assignments in Texas were followed by deployment to Cuba during the Spanish American War and then the Philippines, where he served as an operating surgeon and pathologist aboard the hospital ship, USS Relief. Darnall later accompanied an international expeditionary force to China in response to the Boxer Rebellion. In 1902, Darnall received an assignment to the Army Medical School in Washington, DC, that would change his life and the lives of millions around the world. Detailed as instructor for sanitary chemistry and operative surgery, he also served as secretary of the faculty. Just as Major Walter Reed and others before him, Darnall used his position at the Army Medical School to pursue important clinical research.

The complete story of the purification of drinking water is beyond the scope of this short biography. In brief, as early as 1894 the addition of chlorine to water was shown to render it “germ free.” In the 1890s, there were at least 2 attempts at water purification on a large scale with chlorine in European cities. One of the first uses of chlorine in the U.S. occurred in 1908 in Jersey City, New Jersey. At the Army Medical School, Darnall discovered the value of using compressed liquefied chlorine gas to purify water. He invented a mechanical liquid chlorine purifier in 1910 that became known as a chlorinator. In November 1911, Major Darnall authored a 15-page article concerning water purification.1 Darnall also devised and patented a water filter, which the U.S. Army used for many years.

The principles of his chlorinator and use of anhydrous liquid chlorine were later applied to municipal water supplies throughout the world. The positive benefit of clean drinking water to improving public health is beyond measure. It has been said that more lives have been saved and more sickness prevented by Darnall’s contribution to sanitary water than by any other single achievement in medicine.

During World War I, Darnall was promoted to colonel and assigned to the Finance and Supply Division in the Office of the Surgeon General. After the war, he served as department surgeon in Hawaii. In 1925, he returned to the Office of the Surgeon General as executive officer. In November 1929, he was promoted to brigadier general and became the commanding general of the Army Medical Center and Walter Reed General Hospital, a position he held for 2 years until his retirement in 1931.Darnall died on January 18, 1941, at Walter Reed General Hospital just 6 days after his wife of 48 years had died at their home in Washington, DC. He is buried in Section 3 at Arlington National Cemetery. His 3 sons, Joseph Rogers, William Major, and Carl Robert, all served in some capacity in the Army.

Darnall Army Community Hospital opened in 1965, replacing the World War II-era hospital at Fort Hood. In 1984 a 5-year reconstruction project with additional floor space was completed. On May 1, 2006, the hospital was officially renamed the Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

1. Darnall CR. The purification of water by anhydrous chlorine. J Am Public Health Assoc. 1911;1(11):783-797.

1. Darnall CR. The purification of water by anhydrous chlorine. J Am Public Health Assoc. 1911;1(11):783-797.

Major General David N.W. Grant: An Early Leader in Air Force Medicine

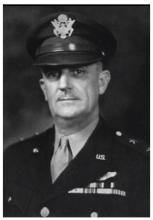

The U.S. Air Force Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base near Fairfield, California, is named in honor of Major General David Norvell Walker Grant, considered by many to be the father of the U.S. Air Force Medical Service. The first legacy organization of the U.S. Air Force was created within the U.S. Army in 1907 (Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps). Through a succession of evolutionary, organizational, and mission changes over 40 years, it became an independent service when the National Security Act of 1947 created the Department of the Air Force. Grant spent most of his career in the predecessor organizations, the U.S. Army Air Corps (1926-1941) and U.S. Army Air Forces (1941-1947).

A native Virginian, Grant graduated from the University of Virginia School of Medicine in 1915 and joined the Army Medical Corps in 1916. His service in World War I included assignments in Panama and within the continental U.S. From 1919 to 1922, he served in Germany in the Army of Occupation. Grant’s aviation medicine career began in 1931 when he attended the School of Aviation Medicine. After he completed the 6-month course, he was stationed at Randolph Field, Texas, for 5 years. In 1937, after more than a decade as a major, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He completed the Air Force Tactical School that same year.

In 1939, Grant became chief of the Medical Division, Office of the Chief of the Air Corps in Washington, DC. On creation of the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1941, he was appointed air surgeon and served in this capacity throughout World War II. He was promoted to colonel in 1941, brigadier general in 1942, and major general in 1943.

Early in preparations for war, Grant recognized that the medical needs of an air force differed significantly from those of large land armies. He and others were successful in their fight to establish a separate medical service for the air forces. During World War II, the U.S. Army Air Forces consisted of 2.4 million personnel and more than 80,000 aircraft. Today the U.S. Air Force has about 320,000 personnel who support and operate about 5,500 aircraft.

Grant was one of the first to understand the need for aeromedical evacuation and was responsible for its organization and operation in World War II. He also was instrumental in the establishment of the Convalescent Rehabilitation Program to help restore the wounded, ill, and injured to full capacity for further service or for their return to the civilian world.

The development and training of flight nurses were inherent in the aeromedical evacuation program. In 1943, the first class of flight nurses graduated from the U.S. Army Air Force School of Air Evacuations at Bowman Field, Kentucky. Second Lieutenant Geraldine Dishroon of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was the honor graduate in her class of 39 students. As she was to receive the first wings presented to a flight nurse, Grant removed his flight surgeon wings and pinned them on Lieutenant Dishroon as a sign of respect for her and the other new flight nurses. In 1944, Lieutenant Dishroon landed with the first air evacuation team on Omaha Beach after the D-Day invasion.

Under Grant’s leadership and guidance, aviation psychologists developed comprehensive mass testing procedures for selecting and classifying potential aircrew members, based on aptitude, personality, and interest. After 3 decades on active duty, Grant retired in 1946 and became medical director for the American Red Cross and national director of the Red Cross Blood Program.

In 1966, 2 years after Grant died, the 4167th Station Hospital at Travis Air Force Base was renamed the David Grant U.S. Air Force Medical Center in his honor.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The U.S. Air Force Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base near Fairfield, California, is named in honor of Major General David Norvell Walker Grant, considered by many to be the father of the U.S. Air Force Medical Service. The first legacy organization of the U.S. Air Force was created within the U.S. Army in 1907 (Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps). Through a succession of evolutionary, organizational, and mission changes over 40 years, it became an independent service when the National Security Act of 1947 created the Department of the Air Force. Grant spent most of his career in the predecessor organizations, the U.S. Army Air Corps (1926-1941) and U.S. Army Air Forces (1941-1947).

A native Virginian, Grant graduated from the University of Virginia School of Medicine in 1915 and joined the Army Medical Corps in 1916. His service in World War I included assignments in Panama and within the continental U.S. From 1919 to 1922, he served in Germany in the Army of Occupation. Grant’s aviation medicine career began in 1931 when he attended the School of Aviation Medicine. After he completed the 6-month course, he was stationed at Randolph Field, Texas, for 5 years. In 1937, after more than a decade as a major, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He completed the Air Force Tactical School that same year.

In 1939, Grant became chief of the Medical Division, Office of the Chief of the Air Corps in Washington, DC. On creation of the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1941, he was appointed air surgeon and served in this capacity throughout World War II. He was promoted to colonel in 1941, brigadier general in 1942, and major general in 1943.

Early in preparations for war, Grant recognized that the medical needs of an air force differed significantly from those of large land armies. He and others were successful in their fight to establish a separate medical service for the air forces. During World War II, the U.S. Army Air Forces consisted of 2.4 million personnel and more than 80,000 aircraft. Today the U.S. Air Force has about 320,000 personnel who support and operate about 5,500 aircraft.

Grant was one of the first to understand the need for aeromedical evacuation and was responsible for its organization and operation in World War II. He also was instrumental in the establishment of the Convalescent Rehabilitation Program to help restore the wounded, ill, and injured to full capacity for further service or for their return to the civilian world.

The development and training of flight nurses were inherent in the aeromedical evacuation program. In 1943, the first class of flight nurses graduated from the U.S. Army Air Force School of Air Evacuations at Bowman Field, Kentucky. Second Lieutenant Geraldine Dishroon of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was the honor graduate in her class of 39 students. As she was to receive the first wings presented to a flight nurse, Grant removed his flight surgeon wings and pinned them on Lieutenant Dishroon as a sign of respect for her and the other new flight nurses. In 1944, Lieutenant Dishroon landed with the first air evacuation team on Omaha Beach after the D-Day invasion.

Under Grant’s leadership and guidance, aviation psychologists developed comprehensive mass testing procedures for selecting and classifying potential aircrew members, based on aptitude, personality, and interest. After 3 decades on active duty, Grant retired in 1946 and became medical director for the American Red Cross and national director of the Red Cross Blood Program.

In 1966, 2 years after Grant died, the 4167th Station Hospital at Travis Air Force Base was renamed the David Grant U.S. Air Force Medical Center in his honor.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The U.S. Air Force Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base near Fairfield, California, is named in honor of Major General David Norvell Walker Grant, considered by many to be the father of the U.S. Air Force Medical Service. The first legacy organization of the U.S. Air Force was created within the U.S. Army in 1907 (Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps). Through a succession of evolutionary, organizational, and mission changes over 40 years, it became an independent service when the National Security Act of 1947 created the Department of the Air Force. Grant spent most of his career in the predecessor organizations, the U.S. Army Air Corps (1926-1941) and U.S. Army Air Forces (1941-1947).

A native Virginian, Grant graduated from the University of Virginia School of Medicine in 1915 and joined the Army Medical Corps in 1916. His service in World War I included assignments in Panama and within the continental U.S. From 1919 to 1922, he served in Germany in the Army of Occupation. Grant’s aviation medicine career began in 1931 when he attended the School of Aviation Medicine. After he completed the 6-month course, he was stationed at Randolph Field, Texas, for 5 years. In 1937, after more than a decade as a major, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He completed the Air Force Tactical School that same year.

In 1939, Grant became chief of the Medical Division, Office of the Chief of the Air Corps in Washington, DC. On creation of the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1941, he was appointed air surgeon and served in this capacity throughout World War II. He was promoted to colonel in 1941, brigadier general in 1942, and major general in 1943.

Early in preparations for war, Grant recognized that the medical needs of an air force differed significantly from those of large land armies. He and others were successful in their fight to establish a separate medical service for the air forces. During World War II, the U.S. Army Air Forces consisted of 2.4 million personnel and more than 80,000 aircraft. Today the U.S. Air Force has about 320,000 personnel who support and operate about 5,500 aircraft.

Grant was one of the first to understand the need for aeromedical evacuation and was responsible for its organization and operation in World War II. He also was instrumental in the establishment of the Convalescent Rehabilitation Program to help restore the wounded, ill, and injured to full capacity for further service or for their return to the civilian world.

The development and training of flight nurses were inherent in the aeromedical evacuation program. In 1943, the first class of flight nurses graduated from the U.S. Army Air Force School of Air Evacuations at Bowman Field, Kentucky. Second Lieutenant Geraldine Dishroon of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was the honor graduate in her class of 39 students. As she was to receive the first wings presented to a flight nurse, Grant removed his flight surgeon wings and pinned them on Lieutenant Dishroon as a sign of respect for her and the other new flight nurses. In 1944, Lieutenant Dishroon landed with the first air evacuation team on Omaha Beach after the D-Day invasion.

Under Grant’s leadership and guidance, aviation psychologists developed comprehensive mass testing procedures for selecting and classifying potential aircrew members, based on aptitude, personality, and interest. After 3 decades on active duty, Grant retired in 1946 and became medical director for the American Red Cross and national director of the Red Cross Blood Program.

In 1966, 2 years after Grant died, the 4167th Station Hospital at Travis Air Force Base was renamed the David Grant U.S. Air Force Medical Center in his honor.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

Bryant Homer Womack: Honoring Sacrifice

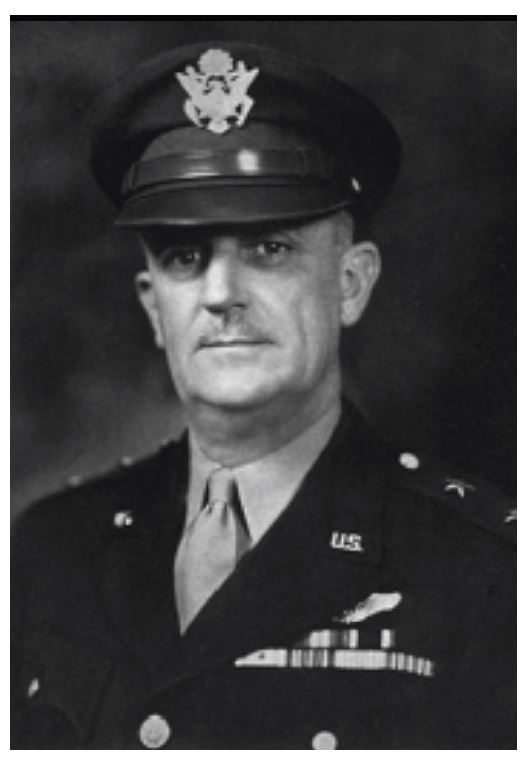

Bryant Homer Womack was born in 1931 and raised in Mill Spring in southwestern North Carolina. He and his 4 siblings grew up doing farmwork. Womack enjoyed the outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. After completing high school, he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950 and later deployed to Korea.

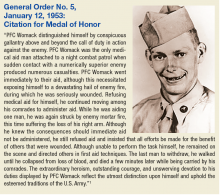

PFC Womack was assigned to the Medical Company, 14th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. During a firefight near Sokso-ri, Korea, on March 12, 1952, his night combat patrol began taking heavy casualties. Womack exposed himself to enemy fire in order to treat his wounded. Although wounded, PFC Womack refused medical treatment and continued to provide aid to others. He was the last soldier to withdraw from the engagement and died of his wounds soon after. Not yet 21 at the time of his death, Womack was buried at Lebanon Methodist Church in his hometown.

PFC Womack received a posthumous Medal of Honor in 1953 (Sidebar) and Womack Army Community Hospital, located on Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, North Carolina, was named for him in 1958. The first medical facility to serve Fort Bragg was constructed in September 1918 as a U.S. States Army Hospital. In June 1932, an 83-bed, 3-story hospital was built and designated Station Hospital One; it was closed in 1941. The building is now Headquarters for XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg. Station Hospital Two and Station Hospital Three were cantonment style hospitals that replaced Station Hospital One. In 1949, the medical facilities were combined and became the U.S. Army Station Hospital.

On August 3, 1958, a new 9-story facility was opened and named Womack Army Community Hospital in honor of combat medic and Medal of Honor recipient PFC Bryant H. Womack. It was renamed the Womack Army Medical Center in 1991. This facility was the principal medical facility for the Fort Bragg community for more than 40 years.

In March, 2000, a new Womack Army Medical Center with more than 1 million square feet of space was dedicated. This new health care complex was part of the U.S. Army Medical Department’s plan to increase patient access to more medical and specialized resources at Fort Bragg.

1. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Medal of Honor Recipients Korean War. https://history.army.mil/moh/koreanwar.html#WOMACK. Updated April 2, 2014. Accessed October 12, 2017.

Bryant Homer Womack was born in 1931 and raised in Mill Spring in southwestern North Carolina. He and his 4 siblings grew up doing farmwork. Womack enjoyed the outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. After completing high school, he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950 and later deployed to Korea.

PFC Womack was assigned to the Medical Company, 14th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. During a firefight near Sokso-ri, Korea, on March 12, 1952, his night combat patrol began taking heavy casualties. Womack exposed himself to enemy fire in order to treat his wounded. Although wounded, PFC Womack refused medical treatment and continued to provide aid to others. He was the last soldier to withdraw from the engagement and died of his wounds soon after. Not yet 21 at the time of his death, Womack was buried at Lebanon Methodist Church in his hometown.

PFC Womack received a posthumous Medal of Honor in 1953 (Sidebar) and Womack Army Community Hospital, located on Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, North Carolina, was named for him in 1958. The first medical facility to serve Fort Bragg was constructed in September 1918 as a U.S. States Army Hospital. In June 1932, an 83-bed, 3-story hospital was built and designated Station Hospital One; it was closed in 1941. The building is now Headquarters for XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg. Station Hospital Two and Station Hospital Three were cantonment style hospitals that replaced Station Hospital One. In 1949, the medical facilities were combined and became the U.S. Army Station Hospital.

On August 3, 1958, a new 9-story facility was opened and named Womack Army Community Hospital in honor of combat medic and Medal of Honor recipient PFC Bryant H. Womack. It was renamed the Womack Army Medical Center in 1991. This facility was the principal medical facility for the Fort Bragg community for more than 40 years.

In March, 2000, a new Womack Army Medical Center with more than 1 million square feet of space was dedicated. This new health care complex was part of the U.S. Army Medical Department’s plan to increase patient access to more medical and specialized resources at Fort Bragg.

Bryant Homer Womack was born in 1931 and raised in Mill Spring in southwestern North Carolina. He and his 4 siblings grew up doing farmwork. Womack enjoyed the outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. After completing high school, he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950 and later deployed to Korea.

PFC Womack was assigned to the Medical Company, 14th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. During a firefight near Sokso-ri, Korea, on March 12, 1952, his night combat patrol began taking heavy casualties. Womack exposed himself to enemy fire in order to treat his wounded. Although wounded, PFC Womack refused medical treatment and continued to provide aid to others. He was the last soldier to withdraw from the engagement and died of his wounds soon after. Not yet 21 at the time of his death, Womack was buried at Lebanon Methodist Church in his hometown.

PFC Womack received a posthumous Medal of Honor in 1953 (Sidebar) and Womack Army Community Hospital, located on Fort Bragg near Fayetteville, North Carolina, was named for him in 1958. The first medical facility to serve Fort Bragg was constructed in September 1918 as a U.S. States Army Hospital. In June 1932, an 83-bed, 3-story hospital was built and designated Station Hospital One; it was closed in 1941. The building is now Headquarters for XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg. Station Hospital Two and Station Hospital Three were cantonment style hospitals that replaced Station Hospital One. In 1949, the medical facilities were combined and became the U.S. Army Station Hospital.

On August 3, 1958, a new 9-story facility was opened and named Womack Army Community Hospital in honor of combat medic and Medal of Honor recipient PFC Bryant H. Womack. It was renamed the Womack Army Medical Center in 1991. This facility was the principal medical facility for the Fort Bragg community for more than 40 years.

In March, 2000, a new Womack Army Medical Center with more than 1 million square feet of space was dedicated. This new health care complex was part of the U.S. Army Medical Department’s plan to increase patient access to more medical and specialized resources at Fort Bragg.

1. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Medal of Honor Recipients Korean War. https://history.army.mil/moh/koreanwar.html#WOMACK. Updated April 2, 2014. Accessed October 12, 2017.

1. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Medal of Honor Recipients Korean War. https://history.army.mil/moh/koreanwar.html#WOMACK. Updated April 2, 2014. Accessed October 12, 2017.

Florence A. Blanchfield: A Lifetime of Nursing Leadership

The U.S. Army hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, was named for army nurse, Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield—making it the only current army hospital named for a nurse.

Florence Aby Blanchfield was born into a large family in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, in 1882. Her mother was a nurse, and her father was a mason and stonecutter. She grew up in Oranda, Virginia, and attended both public and private schools. Following in her mother’s footsteps to become a nurse, she attended Southside Hospital Training School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated in 1906. She moved to Baltimore after graduation and worked with Howard Atwood Kelly, one of the “Big Four” along with William Osler, William Henry Welch, and William Stewart Halsted who were known as the founding physicians of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

After what must have been a remarkable experience with the innovative Kelly (inventor of many groundbreaking medical instruments and procedures, including the Kelly clamp), Blanchfield returned to Pittsburgh. She held positions of increasing responsibility over several years, including operating room supervisor at Southside Hospital and Montefiore Hospital and superintendent of the training school at Suburban General Hospital. Looking for adventure as well as service, she gave up her positions of leadership and headed to Panama in 1913 to become an operating room nurse and an anesthetist at Ancon Hospital in the U.S. Canal Zone.

As America prepared for its probable entry into World War I, Blanchfield joined the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) at age 35 to serve with the Medical School Unit of the University of Pittsburgh’s Base Hospital 27. She arrived in France in October 1917 and became acting chief nurse of Base Hospital 27 in Angers, Maine et Loire department. She also served as acting chief nurse of Camp Hospital 15 at Coëtquidan, Ille et Vil department.

Blanchfield returned to civilian life following World War I for a short period but returned to active duty in 1920. Over the next 15 years, she had several assignments within the continental U.S. and overseas in the Philippines and in Tianjin, China (formally known in English as Tientsin). In 1935, Blanchfield joined the Office of the Army Surgeon General in Washington, DC, where she was assigned to work on personnel matters in the office of the superintendent of the ANC. She became assistant superintendent in 1939, acting superintendent in 1942, and served as superintendent from June 1943 until September 1947. During World War II, she presided over the growth of the ANC from about 7,000 nurses on the day Pearl Harbor was attacked to more than 50,000 by the end of the war. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her contributions and accomplishments during World War II.

Blanchfield, a long-time senior leader in the ANC, was instrumental in many of the significant changes that took place during and after World War II, including nurses gaining full rank and benefits. This was an incremental process that culminated with passage of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps Act of April 1947, with nurses being granted full commissioned status. As a result of this act, she became a lieutenant colonel and the first woman to receive a commission in the regular army.

Blanchfield remained active in national nursing affairs after her retirement from the U.S. Army. At a time when many believed that nurses did not need specialty training, she promoted the establishment of specialized courses of study. In 1951, she received the Florence Nightingale Medal of the International Red Cross.

Blanchfield died on May 12, 1971, and was buried in the nurse’s section of Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In 1978, ANC leadership began a drive to memorialize Blanchfield by naming the new hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in her honor. A successful letter writing campaign by army nurses inundated the senior commander at Fort Campbell. The Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield Army Community Hospital, which was dedicated in her memory on September 17, 1982.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The U.S. Army hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, was named for army nurse, Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield—making it the only current army hospital named for a nurse.

Florence Aby Blanchfield was born into a large family in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, in 1882. Her mother was a nurse, and her father was a mason and stonecutter. She grew up in Oranda, Virginia, and attended both public and private schools. Following in her mother’s footsteps to become a nurse, she attended Southside Hospital Training School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated in 1906. She moved to Baltimore after graduation and worked with Howard Atwood Kelly, one of the “Big Four” along with William Osler, William Henry Welch, and William Stewart Halsted who were known as the founding physicians of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

After what must have been a remarkable experience with the innovative Kelly (inventor of many groundbreaking medical instruments and procedures, including the Kelly clamp), Blanchfield returned to Pittsburgh. She held positions of increasing responsibility over several years, including operating room supervisor at Southside Hospital and Montefiore Hospital and superintendent of the training school at Suburban General Hospital. Looking for adventure as well as service, she gave up her positions of leadership and headed to Panama in 1913 to become an operating room nurse and an anesthetist at Ancon Hospital in the U.S. Canal Zone.

As America prepared for its probable entry into World War I, Blanchfield joined the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) at age 35 to serve with the Medical School Unit of the University of Pittsburgh’s Base Hospital 27. She arrived in France in October 1917 and became acting chief nurse of Base Hospital 27 in Angers, Maine et Loire department. She also served as acting chief nurse of Camp Hospital 15 at Coëtquidan, Ille et Vil department.

Blanchfield returned to civilian life following World War I for a short period but returned to active duty in 1920. Over the next 15 years, she had several assignments within the continental U.S. and overseas in the Philippines and in Tianjin, China (formally known in English as Tientsin). In 1935, Blanchfield joined the Office of the Army Surgeon General in Washington, DC, where she was assigned to work on personnel matters in the office of the superintendent of the ANC. She became assistant superintendent in 1939, acting superintendent in 1942, and served as superintendent from June 1943 until September 1947. During World War II, she presided over the growth of the ANC from about 7,000 nurses on the day Pearl Harbor was attacked to more than 50,000 by the end of the war. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her contributions and accomplishments during World War II.

Blanchfield, a long-time senior leader in the ANC, was instrumental in many of the significant changes that took place during and after World War II, including nurses gaining full rank and benefits. This was an incremental process that culminated with passage of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps Act of April 1947, with nurses being granted full commissioned status. As a result of this act, she became a lieutenant colonel and the first woman to receive a commission in the regular army.

Blanchfield remained active in national nursing affairs after her retirement from the U.S. Army. At a time when many believed that nurses did not need specialty training, she promoted the establishment of specialized courses of study. In 1951, she received the Florence Nightingale Medal of the International Red Cross.

Blanchfield died on May 12, 1971, and was buried in the nurse’s section of Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In 1978, ANC leadership began a drive to memorialize Blanchfield by naming the new hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in her honor. A successful letter writing campaign by army nurses inundated the senior commander at Fort Campbell. The Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield Army Community Hospital, which was dedicated in her memory on September 17, 1982.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The U.S. Army hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, was named for army nurse, Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield—making it the only current army hospital named for a nurse.

Florence Aby Blanchfield was born into a large family in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, in 1882. Her mother was a nurse, and her father was a mason and stonecutter. She grew up in Oranda, Virginia, and attended both public and private schools. Following in her mother’s footsteps to become a nurse, she attended Southside Hospital Training School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated in 1906. She moved to Baltimore after graduation and worked with Howard Atwood Kelly, one of the “Big Four” along with William Osler, William Henry Welch, and William Stewart Halsted who were known as the founding physicians of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

After what must have been a remarkable experience with the innovative Kelly (inventor of many groundbreaking medical instruments and procedures, including the Kelly clamp), Blanchfield returned to Pittsburgh. She held positions of increasing responsibility over several years, including operating room supervisor at Southside Hospital and Montefiore Hospital and superintendent of the training school at Suburban General Hospital. Looking for adventure as well as service, she gave up her positions of leadership and headed to Panama in 1913 to become an operating room nurse and an anesthetist at Ancon Hospital in the U.S. Canal Zone.

As America prepared for its probable entry into World War I, Blanchfield joined the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) at age 35 to serve with the Medical School Unit of the University of Pittsburgh’s Base Hospital 27. She arrived in France in October 1917 and became acting chief nurse of Base Hospital 27 in Angers, Maine et Loire department. She also served as acting chief nurse of Camp Hospital 15 at Coëtquidan, Ille et Vil department.

Blanchfield returned to civilian life following World War I for a short period but returned to active duty in 1920. Over the next 15 years, she had several assignments within the continental U.S. and overseas in the Philippines and in Tianjin, China (formally known in English as Tientsin). In 1935, Blanchfield joined the Office of the Army Surgeon General in Washington, DC, where she was assigned to work on personnel matters in the office of the superintendent of the ANC. She became assistant superintendent in 1939, acting superintendent in 1942, and served as superintendent from June 1943 until September 1947. During World War II, she presided over the growth of the ANC from about 7,000 nurses on the day Pearl Harbor was attacked to more than 50,000 by the end of the war. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her contributions and accomplishments during World War II.

Blanchfield, a long-time senior leader in the ANC, was instrumental in many of the significant changes that took place during and after World War II, including nurses gaining full rank and benefits. This was an incremental process that culminated with passage of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps Act of April 1947, with nurses being granted full commissioned status. As a result of this act, she became a lieutenant colonel and the first woman to receive a commission in the regular army.

Blanchfield remained active in national nursing affairs after her retirement from the U.S. Army. At a time when many believed that nurses did not need specialty training, she promoted the establishment of specialized courses of study. In 1951, she received the Florence Nightingale Medal of the International Red Cross.

Blanchfield died on May 12, 1971, and was buried in the nurse’s section of Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In 1978, ANC leadership began a drive to memorialize Blanchfield by naming the new hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in her honor. A successful letter writing campaign by army nurses inundated the senior commander at Fort Campbell. The Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield Army Community Hospital, which was dedicated in her memory on September 17, 1982.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

Leonard Wood: Advocate of Military Preparedness

Unless you have been assigned to the post or the hospital, you have probably never heard of Leonard Wood. Leonard Wood arguably had the most distinguished military-government career of someone who did not become president. Wood was a Harvard-educated physician, pursued the Apache Chief Geronimo, received the Medal of Honor, was physician to 2 U.S. presidents, served as U.S. army chief of staff, was a successful military governor, ran for president, was a colleague of Walter Reed, and was commander-inarms for President Theodore Roosevelt.

Wood was born in 1860 to an established New England family; his father was a Union Army physician during the Civil War and was practicing on Cape Cod when he died unexpectedly in 1880. The family was left destitute, but Wood was able to continue his education when a wealthy family friend agreed to pay for him to attend Harvard Medical School, which at the time did not require any prior college. He graduated in 1883 and was selected for a prized internship at Boston City Hospital; however, he was dismissed for a rule violation that the program director later admitted was a mistake.

Unable to support himself in practice in Boston, Wood turned to the U.S. Army, a decision that would change his life. Assigned to Fort Huachuca in Arizona, Wood participated in the yearlong pursuit and final surrender of Geronimo; for his role he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1898. His experiences in the wild and rugged terrain of the west triggered a legendary and lifelong pursuit of hard and stressful physical activity. Transferred to California, Wood met Louise Condit-Smith, ward of an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. When they married in November 1890 in Washington, DC, the ceremony was attended by all of the Supreme Court justices.

In 1893 while assigned to Fort McPherson outside Atlanta, Wood, whose duties were not demanding, needed a physical outlet for his unbounded energies. He enrolled at Georgia Tech at age 33 to play football. He was eligible to play because he had not previously attended college. He scored 5 touchdowns, winning the game against rival University of Georgia.

Later, Wood was assigned to Washington, where he quickly became known and sought after as a physician. He served many of the political and military elite, including presidents Grover Cleveland and William McKinley. In 1897, he met Theodore Roosevelt, the 38-year-old assistant secretary of the U.S. Navy who shared his love of outdoor adventure and the military. They became fast friends/companions/competitors; Roosevelt wrote to a friend that he had found a “playmate.”

When the U.S.S. Maine was sunk in Havana Harbor in 1898 and war was declared on Spain, Wood and Roosevelt schemed on how to go to war together. Wood the career soldier and Roosevelt the career politician had excellent connections and became commander and deputy commander of the First Volunteer Calvary, later famously known as the Rough Riders. When a more senior general became ill, Wood was promoted to brigadier general, and Roosevelt became the regiment colonel.

After the war, Wood became military governor of Cuba and major general of volunteers. During the U.S. occupation, Walter Reed was sent to investigate infectious diseases, including yellow fever. Wood provided $10,000 to fund the second phase of Reed’s research and approved the use of human volunteers. When the U.S. occupation ended in 1902, Wood was to revert to captain, medical corps.

Wood’s success in Cuba was obvious and wel l known; President McKinley promoted him to U.S. Army brigadier general. At that time, as a brigadier general, Wood was essentially guaranteed a second star and a rotation through the chief of staff position. He served as chief of staff from 1910 to 1914, the only physician ever to do so. As chief of staff he eliminated the antiquated bureau system, developed the maneuver unit concept, and laid the groundwork for the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps.

Wood stayed on active duty and rotated through other senior-level positions. Because of Wood’s political activity promoting universal service and improving readiness, President Woodrow Wilson passed over him, instead selecting John J. Pershing to command the American Expeditionary Force in World War I. Wood stayed politically active and ran for the Republican presidential nomination in 1920, losing to Warren G. Harding at the convention. Wood was appointed governor general of the Philippines, a position he held until his death in 1927.

While in Cuba, Wood was severely injured by striking his head on a chandelier, most likely resulting in an undiagnosed skull fracture. Over time he developed neurologic symptoms and was seen by neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing, MD, at Johns Hopkins, who removed a meningioma in February 1910. Wood made a dramatic recovery. Over a decade later while in the Philippines, his symptoms returned, and after significant delay he went home to see Cushing who was then at Harvard Medical School. When Wood died after surgery, Cushing admitted that he should not have tackled such a difficult case so quickly after returning from a trip to Europe.

Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri and the on-base General Leonard Wood U.S. Army Community Hospital are named in Wood’s honor.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual

your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

Unless you have been assigned to the post or the hospital, you have probably never heard of Leonard Wood. Leonard Wood arguably had the most distinguished military-government career of someone who did not become president. Wood was a Harvard-educated physician, pursued the Apache Chief Geronimo, received the Medal of Honor, was physician to 2 U.S. presidents, served as U.S. army chief of staff, was a successful military governor, ran for president, was a colleague of Walter Reed, and was commander-inarms for President Theodore Roosevelt.

Wood was born in 1860 to an established New England family; his father was a Union Army physician during the Civil War and was practicing on Cape Cod when he died unexpectedly in 1880. The family was left destitute, but Wood was able to continue his education when a wealthy family friend agreed to pay for him to attend Harvard Medical School, which at the time did not require any prior college. He graduated in 1883 and was selected for a prized internship at Boston City Hospital; however, he was dismissed for a rule violation that the program director later admitted was a mistake.

Unable to support himself in practice in Boston, Wood turned to the U.S. Army, a decision that would change his life. Assigned to Fort Huachuca in Arizona, Wood participated in the yearlong pursuit and final surrender of Geronimo; for his role he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1898. His experiences in the wild and rugged terrain of the west triggered a legendary and lifelong pursuit of hard and stressful physical activity. Transferred to California, Wood met Louise Condit-Smith, ward of an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. When they married in November 1890 in Washington, DC, the ceremony was attended by all of the Supreme Court justices.

In 1893 while assigned to Fort McPherson outside Atlanta, Wood, whose duties were not demanding, needed a physical outlet for his unbounded energies. He enrolled at Georgia Tech at age 33 to play football. He was eligible to play because he had not previously attended college. He scored 5 touchdowns, winning the game against rival University of Georgia.

Later, Wood was assigned to Washington, where he quickly became known and sought after as a physician. He served many of the political and military elite, including presidents Grover Cleveland and William McKinley. In 1897, he met Theodore Roosevelt, the 38-year-old assistant secretary of the U.S. Navy who shared his love of outdoor adventure and the military. They became fast friends/companions/competitors; Roosevelt wrote to a friend that he had found a “playmate.”

When the U.S.S. Maine was sunk in Havana Harbor in 1898 and war was declared on Spain, Wood and Roosevelt schemed on how to go to war together. Wood the career soldier and Roosevelt the career politician had excellent connections and became commander and deputy commander of the First Volunteer Calvary, later famously known as the Rough Riders. When a more senior general became ill, Wood was promoted to brigadier general, and Roosevelt became the regiment colonel.

After the war, Wood became military governor of Cuba and major general of volunteers. During the U.S. occupation, Walter Reed was sent to investigate infectious diseases, including yellow fever. Wood provided $10,000 to fund the second phase of Reed’s research and approved the use of human volunteers. When the U.S. occupation ended in 1902, Wood was to revert to captain, medical corps.

Wood’s success in Cuba was obvious and wel l known; President McKinley promoted him to U.S. Army brigadier general. At that time, as a brigadier general, Wood was essentially guaranteed a second star and a rotation through the chief of staff position. He served as chief of staff from 1910 to 1914, the only physician ever to do so. As chief of staff he eliminated the antiquated bureau system, developed the maneuver unit concept, and laid the groundwork for the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps.