User login

Wearable Health Device Dermatitis: A Case of Acrylate-Related Contact Allergy

Mobile health devices enable patients and clinicians to monitor the type, quantity, and quality of everyday activities and hold the promise of improving patient health and health care practices.1 In 2013, 75% of surveyed consumers in the United States owned a fitness technology product, either a dedicated fitness device, application, or portable blood pressure monitor.2 Ownership of dedicated wearable fitness devices among consumers in the United States increased from 3% in 2012 to 9% in 2013. The immense popularity of wearable fitness devices is evident in the trajectory of their reported sales, which increased from $43 million in 2009 to $854 million in 2013.2 Recognizing that “widespread adoption and use of mobile technologies is opening new and innovative ways to improve health,”3 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ruled that “[technologies] that can pose a greater risk to patients will require FDA review.” One popular class of mobile technologies—activity and sleep sensors—falls outside the FDA’s regulatory guidance. To enable continuous monitoring, these sensors often are embedded into wearable devices.

Reports in the media have documented skin rashes arising in conjunction with use of one type of device,4 which may be related to nickel contact allergy, and the manufacturer has reported that the metal housing consists of surgical stainless steel that is known to contain nickel. We report a complication related to continuous use of an unregulated, commercially available, watchlike wearable sensor that was linked not to nickel but to an acrylate-containing component.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 52-year-old woman with no history of contact allergy presented with an intensely itchy eruption involving the left wrist arising 4 days after continuous use of a new watchlike wearable fitness sensor. By day 11, the eruption evolved into a well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaque at the location where the device’s rechargeable battery metal housing came into contact with skin (Figure 1).

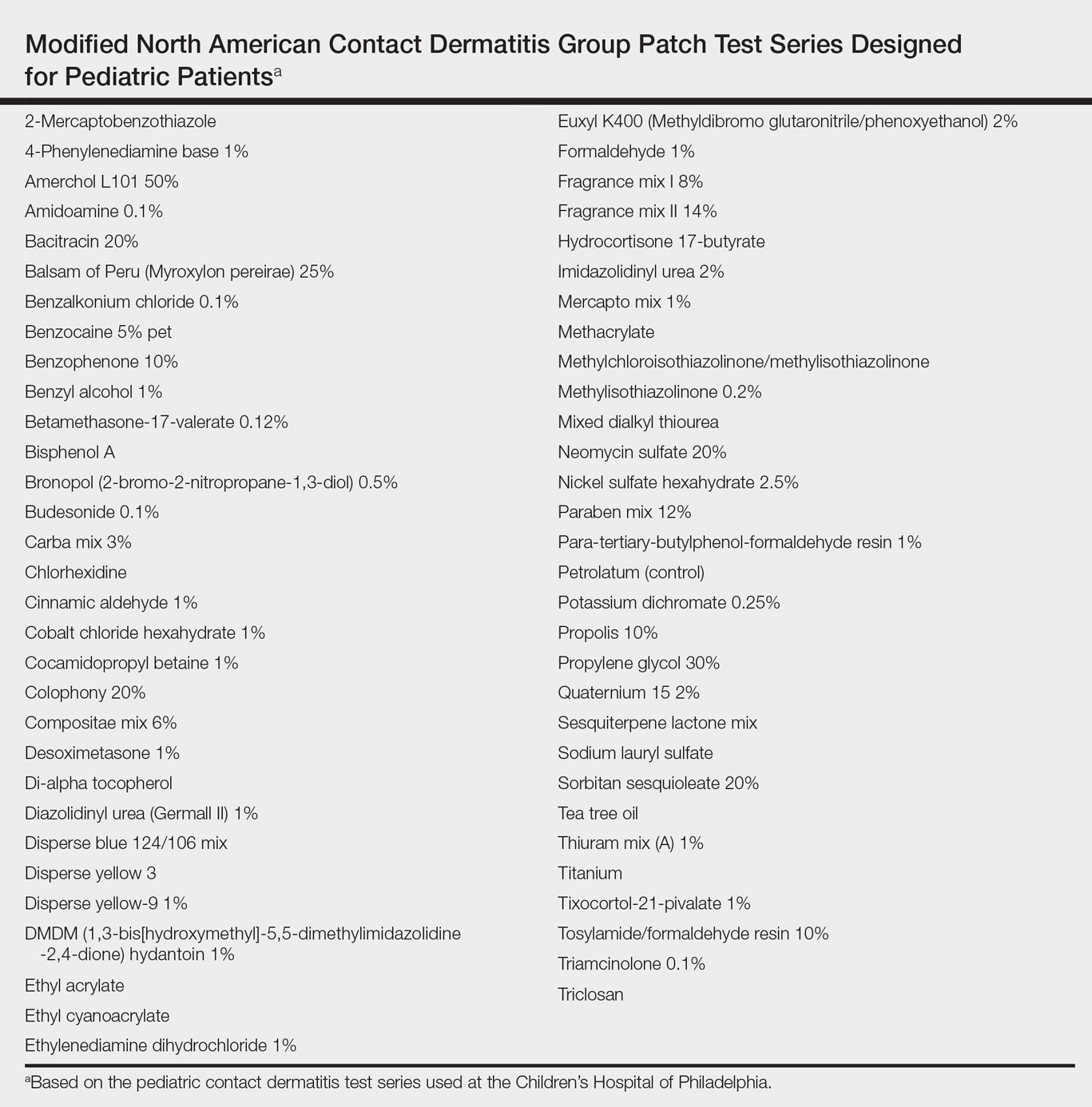

Dimethylglyoxime testing of the metal housing and clips was negative, but testing of contacts within the housing was positive for nickel (Figure 2). Epicutaneous patch testing of the patient using a modified North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test series (Table) demonstrated no reaction to nickel, instead showing a strong positive (2+) reaction at 48 and 72 hours to methyl methacrylate 2% and a positive (1+) reaction at 96 hours to ethyl acrylate 0.1% (Figure 3).

Comment

Acrylates are used as adhesives to bond metal to plastic and as part of lithium ion polymer batteries, presumably similar to the one used in this device.5 Our patient had a history of using acrylic nail polish, which may have been a source of prior sensitization. Exposure to sweat or other moisture could theoretically dissolve such a water-soluble polymer,6 allowing for skin contact. Other acrylate polymers have been reported to break down slowly in contact with water, leading to contact sensitization to the monomer.7 The manufacturer of the device was contacted for additional information but declined to provide specific details regarding the device’s composition (personal communication, January 2014).

Although not considered toxic,8 acrylate was named Allergen of the Year in 2012 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.9-11 Nickel might be a source of allergy for some other patients who wear mobile health devices, but we concluded that this particular patient developed allergic contact dermatitis from prolonged exposure to low levels of methyl methacrylate or another acrylate due to gradual breakdown of the acrylate polymer used in the rechargeable battery housing for this wearable health device.

Given the FDA’s tailored risk approach to regulation, many wearable sensors that may contain potential contact allergens such as nickel and acrylates do not fall under the FDA regulatory framework. This case should alert physicians to the lack of regulatory oversight for many mobile technologies. They should consider a screening history for contact allergens before recommending wearable sensors and broader testing for contact allergens should exposed patients develop reactions. Future wearable sensor materials and designs should minimize exposure to allergens given prolonged contact with continuous use. In the absence of regulation, manufacturers of these devices should consider due care testing prior to commercialization.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Alexander S. Rattner, PhD (State College, Pennsylvania), who provided his engineering expertise and insight during conversations with the authors.

- Dobkin BH, Dorsch A. The promise of mHealth: daily activity monitoring and outcome assessments by wearable sensors. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:788-798.

- Consumer interest in purchasing wearable fitness devices in 2014 quadruples, according to CEA Study [press release]. Arlington, VA: Consumer Electronics Association; December 11, 2013.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mobile medical applications. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/digitalhealth/mobilemedicalapplications/default.htm. Updated September 22, 2015. Accessed July 26, 2017.

- Northrup L. Fitbit Force is an amazing device, except for my contact dermatitis. Consumerist website. http://consumerist.com/2014/01/13/fitbit-force-is-an-amazing-device-except-for-my-contact-dermatitis/. Published January 13, 2014. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Stern B. Inside Fitbit Force. Adafruit website. http://learn.adafruit.com/fitbit-force-teardown/inside-fitbit-force. Published December 11, 2013. Updated May 4, 2015. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Pemberton MA, Lohmann BS. Risk assessment of residual monomer migrating from acrylic polymers and causing allergic contact dermatitis during normal handling and use. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69:467-475.

- Guin JD, Baas K, Nelson-Adesokan P. Contact sensitization to cyanoacrylate adhesive as a cause of severe onychodystrophy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:31-36.

- Zondlo Fiume M. Final report on the safety assessment of Acrylates Copolymer and 33 related cosmetic ingredients. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(suppl 3):1-50.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates. Dermatitis. 2012;23:3-5.

- Bowen C, Bidinger J, Hivnor C, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Cutis. 2014;94:183-186.

- Spencer A, Gazzani P, Thompson DA. Acrylate and methacrylate contact allergy and allergic contact disease: a 13-year review [published online July 11, 2016]. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:157-164.

Mobile health devices enable patients and clinicians to monitor the type, quantity, and quality of everyday activities and hold the promise of improving patient health and health care practices.1 In 2013, 75% of surveyed consumers in the United States owned a fitness technology product, either a dedicated fitness device, application, or portable blood pressure monitor.2 Ownership of dedicated wearable fitness devices among consumers in the United States increased from 3% in 2012 to 9% in 2013. The immense popularity of wearable fitness devices is evident in the trajectory of their reported sales, which increased from $43 million in 2009 to $854 million in 2013.2 Recognizing that “widespread adoption and use of mobile technologies is opening new and innovative ways to improve health,”3 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ruled that “[technologies] that can pose a greater risk to patients will require FDA review.” One popular class of mobile technologies—activity and sleep sensors—falls outside the FDA’s regulatory guidance. To enable continuous monitoring, these sensors often are embedded into wearable devices.

Reports in the media have documented skin rashes arising in conjunction with use of one type of device,4 which may be related to nickel contact allergy, and the manufacturer has reported that the metal housing consists of surgical stainless steel that is known to contain nickel. We report a complication related to continuous use of an unregulated, commercially available, watchlike wearable sensor that was linked not to nickel but to an acrylate-containing component.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 52-year-old woman with no history of contact allergy presented with an intensely itchy eruption involving the left wrist arising 4 days after continuous use of a new watchlike wearable fitness sensor. By day 11, the eruption evolved into a well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaque at the location where the device’s rechargeable battery metal housing came into contact with skin (Figure 1).

Dimethylglyoxime testing of the metal housing and clips was negative, but testing of contacts within the housing was positive for nickel (Figure 2). Epicutaneous patch testing of the patient using a modified North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test series (Table) demonstrated no reaction to nickel, instead showing a strong positive (2+) reaction at 48 and 72 hours to methyl methacrylate 2% and a positive (1+) reaction at 96 hours to ethyl acrylate 0.1% (Figure 3).

Comment

Acrylates are used as adhesives to bond metal to plastic and as part of lithium ion polymer batteries, presumably similar to the one used in this device.5 Our patient had a history of using acrylic nail polish, which may have been a source of prior sensitization. Exposure to sweat or other moisture could theoretically dissolve such a water-soluble polymer,6 allowing for skin contact. Other acrylate polymers have been reported to break down slowly in contact with water, leading to contact sensitization to the monomer.7 The manufacturer of the device was contacted for additional information but declined to provide specific details regarding the device’s composition (personal communication, January 2014).

Although not considered toxic,8 acrylate was named Allergen of the Year in 2012 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.9-11 Nickel might be a source of allergy for some other patients who wear mobile health devices, but we concluded that this particular patient developed allergic contact dermatitis from prolonged exposure to low levels of methyl methacrylate or another acrylate due to gradual breakdown of the acrylate polymer used in the rechargeable battery housing for this wearable health device.

Given the FDA’s tailored risk approach to regulation, many wearable sensors that may contain potential contact allergens such as nickel and acrylates do not fall under the FDA regulatory framework. This case should alert physicians to the lack of regulatory oversight for many mobile technologies. They should consider a screening history for contact allergens before recommending wearable sensors and broader testing for contact allergens should exposed patients develop reactions. Future wearable sensor materials and designs should minimize exposure to allergens given prolonged contact with continuous use. In the absence of regulation, manufacturers of these devices should consider due care testing prior to commercialization.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Alexander S. Rattner, PhD (State College, Pennsylvania), who provided his engineering expertise and insight during conversations with the authors.

Mobile health devices enable patients and clinicians to monitor the type, quantity, and quality of everyday activities and hold the promise of improving patient health and health care practices.1 In 2013, 75% of surveyed consumers in the United States owned a fitness technology product, either a dedicated fitness device, application, or portable blood pressure monitor.2 Ownership of dedicated wearable fitness devices among consumers in the United States increased from 3% in 2012 to 9% in 2013. The immense popularity of wearable fitness devices is evident in the trajectory of their reported sales, which increased from $43 million in 2009 to $854 million in 2013.2 Recognizing that “widespread adoption and use of mobile technologies is opening new and innovative ways to improve health,”3 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ruled that “[technologies] that can pose a greater risk to patients will require FDA review.” One popular class of mobile technologies—activity and sleep sensors—falls outside the FDA’s regulatory guidance. To enable continuous monitoring, these sensors often are embedded into wearable devices.

Reports in the media have documented skin rashes arising in conjunction with use of one type of device,4 which may be related to nickel contact allergy, and the manufacturer has reported that the metal housing consists of surgical stainless steel that is known to contain nickel. We report a complication related to continuous use of an unregulated, commercially available, watchlike wearable sensor that was linked not to nickel but to an acrylate-containing component.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 52-year-old woman with no history of contact allergy presented with an intensely itchy eruption involving the left wrist arising 4 days after continuous use of a new watchlike wearable fitness sensor. By day 11, the eruption evolved into a well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaque at the location where the device’s rechargeable battery metal housing came into contact with skin (Figure 1).

Dimethylglyoxime testing of the metal housing and clips was negative, but testing of contacts within the housing was positive for nickel (Figure 2). Epicutaneous patch testing of the patient using a modified North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test series (Table) demonstrated no reaction to nickel, instead showing a strong positive (2+) reaction at 48 and 72 hours to methyl methacrylate 2% and a positive (1+) reaction at 96 hours to ethyl acrylate 0.1% (Figure 3).

Comment

Acrylates are used as adhesives to bond metal to plastic and as part of lithium ion polymer batteries, presumably similar to the one used in this device.5 Our patient had a history of using acrylic nail polish, which may have been a source of prior sensitization. Exposure to sweat or other moisture could theoretically dissolve such a water-soluble polymer,6 allowing for skin contact. Other acrylate polymers have been reported to break down slowly in contact with water, leading to contact sensitization to the monomer.7 The manufacturer of the device was contacted for additional information but declined to provide specific details regarding the device’s composition (personal communication, January 2014).

Although not considered toxic,8 acrylate was named Allergen of the Year in 2012 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.9-11 Nickel might be a source of allergy for some other patients who wear mobile health devices, but we concluded that this particular patient developed allergic contact dermatitis from prolonged exposure to low levels of methyl methacrylate or another acrylate due to gradual breakdown of the acrylate polymer used in the rechargeable battery housing for this wearable health device.

Given the FDA’s tailored risk approach to regulation, many wearable sensors that may contain potential contact allergens such as nickel and acrylates do not fall under the FDA regulatory framework. This case should alert physicians to the lack of regulatory oversight for many mobile technologies. They should consider a screening history for contact allergens before recommending wearable sensors and broader testing for contact allergens should exposed patients develop reactions. Future wearable sensor materials and designs should minimize exposure to allergens given prolonged contact with continuous use. In the absence of regulation, manufacturers of these devices should consider due care testing prior to commercialization.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Alexander S. Rattner, PhD (State College, Pennsylvania), who provided his engineering expertise and insight during conversations with the authors.

- Dobkin BH, Dorsch A. The promise of mHealth: daily activity monitoring and outcome assessments by wearable sensors. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:788-798.

- Consumer interest in purchasing wearable fitness devices in 2014 quadruples, according to CEA Study [press release]. Arlington, VA: Consumer Electronics Association; December 11, 2013.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mobile medical applications. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/digitalhealth/mobilemedicalapplications/default.htm. Updated September 22, 2015. Accessed July 26, 2017.

- Northrup L. Fitbit Force is an amazing device, except for my contact dermatitis. Consumerist website. http://consumerist.com/2014/01/13/fitbit-force-is-an-amazing-device-except-for-my-contact-dermatitis/. Published January 13, 2014. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Stern B. Inside Fitbit Force. Adafruit website. http://learn.adafruit.com/fitbit-force-teardown/inside-fitbit-force. Published December 11, 2013. Updated May 4, 2015. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Pemberton MA, Lohmann BS. Risk assessment of residual monomer migrating from acrylic polymers and causing allergic contact dermatitis during normal handling and use. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69:467-475.

- Guin JD, Baas K, Nelson-Adesokan P. Contact sensitization to cyanoacrylate adhesive as a cause of severe onychodystrophy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:31-36.

- Zondlo Fiume M. Final report on the safety assessment of Acrylates Copolymer and 33 related cosmetic ingredients. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(suppl 3):1-50.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates. Dermatitis. 2012;23:3-5.

- Bowen C, Bidinger J, Hivnor C, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Cutis. 2014;94:183-186.

- Spencer A, Gazzani P, Thompson DA. Acrylate and methacrylate contact allergy and allergic contact disease: a 13-year review [published online July 11, 2016]. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:157-164.

- Dobkin BH, Dorsch A. The promise of mHealth: daily activity monitoring and outcome assessments by wearable sensors. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:788-798.

- Consumer interest in purchasing wearable fitness devices in 2014 quadruples, according to CEA Study [press release]. Arlington, VA: Consumer Electronics Association; December 11, 2013.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mobile medical applications. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/digitalhealth/mobilemedicalapplications/default.htm. Updated September 22, 2015. Accessed July 26, 2017.

- Northrup L. Fitbit Force is an amazing device, except for my contact dermatitis. Consumerist website. http://consumerist.com/2014/01/13/fitbit-force-is-an-amazing-device-except-for-my-contact-dermatitis/. Published January 13, 2014. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Stern B. Inside Fitbit Force. Adafruit website. http://learn.adafruit.com/fitbit-force-teardown/inside-fitbit-force. Published December 11, 2013. Updated May 4, 2015. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Pemberton MA, Lohmann BS. Risk assessment of residual monomer migrating from acrylic polymers and causing allergic contact dermatitis during normal handling and use. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69:467-475.

- Guin JD, Baas K, Nelson-Adesokan P. Contact sensitization to cyanoacrylate adhesive as a cause of severe onychodystrophy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:31-36.

- Zondlo Fiume M. Final report on the safety assessment of Acrylates Copolymer and 33 related cosmetic ingredients. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(suppl 3):1-50.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates. Dermatitis. 2012;23:3-5.

- Bowen C, Bidinger J, Hivnor C, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Cutis. 2014;94:183-186.

- Spencer A, Gazzani P, Thompson DA. Acrylate and methacrylate contact allergy and allergic contact disease: a 13-year review [published online July 11, 2016]. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:157-164.

Practice Points

- Mobile wearable health devices are likely to become an important potential source of contact sensitization as their use increases given their often prolonged contact time with the skin.

- Mobile wearable health devices may pose a risk for allergic contact dermatitis as a result of a variety of components that come into contact with the skin, including but not limited to metals, rubber components, adhesives, and dyes.